ABSTRACT

Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020 and became a global health crisis with devastating impacts. This scoping review maps the key findings of research about the pandemic that has operationalized intersectional research methods around the world. It also tracks how these studies have engaged with methodological tenets of oppression, comparison, relationality, complexity, and deconstruction.

Methods

Our search resulted in 14,487 articles, 5164 of which were duplicates, and 9297 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. In total, 14 articles were included in this review. We used thematic analysis to analyse themes within this work and Misra et al. (2021) intersectional research framework to analyse the uptake of intersectional methods within such studies.

Results

The research related to the COVID-19 pandemic globally is paying attention to issues around the financial impacts of the pandemic, discrimination, gendered impacts, impacts of and on social ties, and implications for mental health. We also found strong uptake of centring research in the context of oppression, but less attention is being paid to comparison, relationality, complexity, and deconstruction.

Conclusions

Our findings show the importance of intersectional research within public health policy formation, as well as room for greater rigour in the use of intersectional methods.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020 and became a global health crisis with devastating impacts. Since then, researchers have studied the effects of the pandemic on those from socially vulnerable groups including African, Caribbean, and Black people (Etowa & Hyman, Citation2021), older persons (Yang et al., Citation2020), and sexual and gender minorities (Lokot & Avakyan, Citation2020). Public health measures implemented to curb the spread of COVID-19 and its impact on various populations have been largely generalized, with some exceptions, including the prioritization of older Indigenous people for vaccinations (Tasker, Citation2021). Accordingly, most measures have failed to address direct and indirect impacts on vulnerable groups (Lokot & Avakyan, Citation2020). Many of these measures failed to consider the unique needs of those at the intersections of multiple axes of oppression (Bhalla & Agarwal, Citation2021; Bowleg, Citation2020; Yang et al., Citation2020).

A plethora of non-intersectional work has investigated the impacts of the pandemic—for example, impacts on mental health. Much attention has been paid to grief concerning both job loss (Koul & Nayar, Citation2022; Motahedi et al., Citation2021) and loss of human life (Lee & Neimeyer, Citation2022), suggesting a need for communal and collective healing (Castrellón et al., Citation2021). Such studies have noted that men experienced higher infection and mortality rates but women experienced hardship from the effects of the pandemic (including financial loss, increases in care labour, and increases in vulnerability to abuse) at greater rates (Kabeer et al., Citation2021). Significant knowledge is also available concerning the immediate impacts of the pandemic on mental health care (Sheridan Rains et al., Citation2021; Thome et al., Citation2021). However, the lack of intersectional understanding of the impacts on mental health care and services may prove a future limitation of policy and practice.

Recently, a compilation of podcast transcripts from the Under the Blacklight livestream event series and Intersectionality podcast (hosted by Kimberlé Crenshaw and the African American Policy Forum) highlights how pre-existing inequalities and intersectional processes of capitalism, nationalism, racism, and patriarchal oppression have converged and shaped the pandemic and pandemic impacts (Crenshaw & HoSang, Citation2023). Additionally, research has investigated the pandemic’s impacts on those who were already marginalized without explicit employment of intersectionality theory. Such studies have accounted for socio-economic status, race, sex and gender, occupation, and health status (see, e.g., Hawkins et al., Citation2020). This work shows that lower levels of education and being Black are strongly associated with higher levels of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality (Hawkins et al., Citation2020; Ribeiro et al., Citation2021). It also shows that Hispanic and Black frontline workers are overrepresented in lower-income occupations, such as healthcare personnel, associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 infection (Asfaw, Citation2022; Goldman et al., Citation2021). Infection rates in women and men also differ by age; infections in women are higher among people of working age, while infections in men are higher among older demographic groups (Sobotka et al., Citation2020). Studies in the USA show Black women are more likely to be infected and die from COVID-19 compared to White men and that Black men have the highest mortality rates (Rushovich et al., Citation2021). Overall, these findings indicate societal and structural inequities that have wider policy implications.

These findings make a case for intersectional approaches to public healthcare research. As a theory, intersectionality emanated from the work of Black feminists and activists, with Kimberlé Crenshaw first coining the term in 1989. Using the analogy of traffic at an intersection, Crenshaw shows how multiple forms or channels of oppression, including racial and gender discrimination, can simultaneously create multiple and aggravated forms of disadvantages (Crenshaw, Citation1989). The combination and compounding of oppressions aggravate the totality of harm suffered by the individual.

Hence, an intersectionality framework provides a critical analytic lens for researchers and highlights the diverse aspects of social locations, differences, and identities hidden due to structural processes that intersect independently or simultaneously at different structural levels in complex and independent ways (Crenshaw, Citation1989). Thus, individual experiences are complex and multilayered, prompting researchers to execute a more critically informed analysis of disparities while considering multiple-axis thinking in consideration of power (Bowleg, Citation2020; Cho et al., Citation2013; Collins & Bilge, Citation2016).

The concept of intersectionality provides scholars with a framework to understand how identities such as age, ability, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, race, Indigeneity, and class intersect to reflect significant social structural inequalities (Cho et al., Citation2013; Collins & Bilge, Citation2016; Crenshaw, Citation1989). Social sciences and health researchers have used intersectionality to interrogate how systems of power function in the content and interpretation of laws, legal theory (Crenshaw, Citation1989), social activism (Cho et al., Citation2013), and the potential to shape policy, practice, and research (Collins & Bilge, Citation2016; Hankivsky, Citation2012; Mason, Citation2010). Crenshaw (Citation1989, Citation1991) depicts how socially constructed categories embedded in structural power relations interact in mutually integral ways to produce intersecting forms of disadvantage to diverse groups such as women of colour. Similarly, intersectionality has been used as a framework for grief research (Thacker & Duran, Citation2022); as a frame for higher education research (Harris & Patton, Citation2019; Nichols & Stahl, Citation2019); to explore inequities surrounding 2SLGBTQ+ discrimination (Bowleg, Citation2020); and as a framework for conducting qualitative health research (Abrams & Szefler, Citation2020).

Hankivsky (Citation2012) provides principles that guide intersectionality research: intersecting categories, multi-level analysis, power, reflexivity, time and space, diversity of knowledge, social justice, equity, and resistance and resilience. Similarly, Collins and Bilge (Citation2016) describe six core ideas on intersectionality: inequality, relationality, power, social context, complexity, and social justice. These theorists explain intersectionality as a tool for understanding invisible relations by employing an anti-categorical approach that could perpetuate inequality by incorporating the concepts of power and oppression to research (Browne & Misra, Citation2003). Empirical intersectional research can be done in various ways (Misra et al., Citation2021). However, weaknesses including ambiguity in its methodology, lack of understanding, and more attention to intersectional theorizing than intersectional methodology have been noted (Misra et al., Citation2021). The aim of our study is to map different analytical methods of empirical intersectional research conducted on the COVID-19 pandemic, situating the core ideas of intersectionality as explained by Collins and Bilge (Citation2016).

Intersectionality has grown considerably in scope and depth over the last three decades, yet analysis of this lens has primarily remained a discussion among theorists (Cho et al., Citation2013; Collins & Bilge, Citation2016; Crenshaw, Citation1989, Citation1991). Minimal attention has yet been paid to the use of intersectionality methods. More recently, research has turned to consider methods within intersectional analysis and research (Misra et al., Citation2021), but no review has yet considered the theory’s operationalization in studies related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings add to the knowledge of both intersectionality as a theory and approach and to the insight of the pandemic and its impacts around the world.

Methods

Our review follows Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) five-stage methodological framework, which is suitable for exploring and mapping literature and identifying research gaps on subject matters. Stage 1: Identifying the research question; Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies; Stage 3: Selecting studies; Stage 4: Charting the data; and Stage 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The first stage was to identify a research question and define a roadmap for guiding the review. Accordingly, our review was guided by two research questions:

What are the key findings of research studies that have used an intersectional theoretical lens or intersectional research methodology in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic?

How has intersectionality been operationalized in research studies on the COVID-19 pandemic across the globe?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Bibliographic database searches were conducted in early 2022 (February 27-6 April 2022). The search was designed by a librarian (TC) with consultation from the research team. The following databases were searched: Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid Embase, Ovid APA PsycInfo, Ovid Global Health, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Anthropology Plus (EBSCOhost), EconLit (EBSCOhost), Gender Studies (EBSCOhost), Legal Source (EBSCOhost), LGBTQ+ Source (EBSCOhost), Political Science Complete (EBSCOhost), SocINDEX (EBSCOhost), PAIS Index (Proquest), Sociological Abstracts (Proquest), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, Web of Science Core Collection (Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Sciences & Humanities, Book Citation Index, Emerging Sources Citation Index), Scopus, HeinOnline, and WHO COVID-19 Global Literature on Coronavirus Disease. Search queries were developed using subject headings for appropriate databases and keywords. Subject headings and search operators were modified for each specific database. The search contained several concepts related to intersectionality: religion, race, socioeconomic status, disability, migration, age, and sexuality. These areas were determined by the research team to be of greatest interest as they are the most commonly discussed axes within the literature. Each of these concepts was combined with terms related to COVID-19 and gender with the exception of searches for the term intersectional, which was only combined with the terms COVID-19 and pandemic.

Stage 3: selecting studies

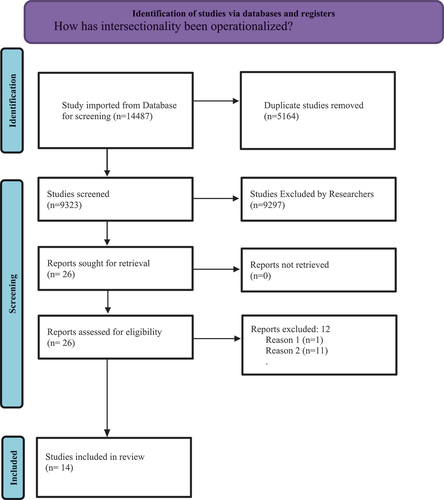

The search strategies for COVID-19 were based on the COVID search filters developed by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). In total 14,487 articles were retrieved. Of these, 5164 were duplicates. There were 9323 citations downloaded from the bibliographic databases into an Endnote library (Endnote 20) and from there were exported into Covidence where title and abstracts were reviewed independently by two researchers. Nine thousand two hundred and ninety-seven studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The full text of 26 articles were retrieved and independently reviewed by two researchers to determine the eligibility of the articles. Twelve articles were further excluded, leaving 14 articles that met inclusion criteria and were included in the scoping review. A third researcher resolved disagreements between the two researchers at all review stages. Reference lists of included articles and grey literature were searched for additional articles, but none of the articles met the inclusion criteria of the study. No language restrictions were used in this search. Searches were limited to publications written since 2019 when COVID-19 first appeared ().

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram: operationalization of intersectionality research methods in studies related to COVID-19.

Reason for Exclusion:

Duplicate

Does not meet the inclusion criteria (use of intersectionality theory; focus on COVID-19)

Adapted from: Page et al. (Citation2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement.

Stage 4: charting the data

Two researchers then extracted data from all 14 articles. This data extraction involved charting and sorting the findings of the included articles into key issues and analytical categories related to the use of an intersectionality theoretical framework on studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The following information was extracted from all articles: author(s) name, year of publication, the purpose of the study, study population, methods, results/findings, intersection variables, implications, and ways studies engaged with intersectional methods such as employing the concept of oppression, engaging with the comparison of axes, considering relationality, engaging with complexity within categories of social location, and deconstruction.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Qualitative studies were analysed in two ways. First, thematic analysis was used to synthesize and categorize included studies’ findings into themes (drawing from Braun & Clarke, Citation2014). To do so, we read the included articles several times and familiarized ourselves with the data. Initial codes were generated based on the identified intersectional identities while prioritizing relevance to the research questions of our study. Subsequently, we compiled codes into potential themes, grouped all data relevant to the potential theme, and compared data across the coded excerpts and the entire dataset. The results from this analysis are presented first in our results section.

Second, we drew both on Collins and Bilge’s (Citation2016) and Misra et al. (Citation2021) articulation of intersectional methodological tenets to map the ways the included literature has deployed these methods across research related to the COVID-19 pandemic. While Collins and Bilge’s (Citation2016) concern for inequality, relationality, power, social context, complexity, and social justice informed our theoretical engagement with this question, we instead chose to organize our findings through Misra et al. (Citation2021) framework of oppression, comparison, relationality, complexity, and deconstruction as these categories made more sense to us as ways to track the methods of intersectionality in a practical, less theoretical sense.

In their framework, Misra et al. (Citation2021) explain oppression as the ways analysis considered violence as dependent on a historical context, the “matrix of domination” (Collins, Citation2000), of white supremacist patriarchy and colonization, and the extent to which the study tried to disrupt power by centring marginalized voices. Second, they write that comparison accounts for ways attention to different axes and intersections may lend different insights. Third, they task research with thinking about relationality in two ways: in connecting the marginalization of some to the over-advantage of others and in making researcher positionality, bias, and relationships to power explicit. Finally, they explain that intersectional research should engage in complexities in identity and social categories and refrain from falling into Western reliance on binary and separation. Connected to this, they call for the deconstruction of these binaries and social categories of difference. Our analysis of the ways these methods were used is presented in the second half of our results section.

Results

Fourteen papers met our inclusion criteria: utilizing intersectionality theory and focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic. They spanned the globe, including settings such as the United States, Mexico, India, Australia, the United Arab Emirates, and Canada. Significantly, this review shows intersectional research methods are being deployed in research related to the pandemic across a range of Global North and Global South countries.

Twelve articles used qualitative methods: five articles used in-depth interviews; three used focus groups; three used phenomenology; and one used narrative inquiry. Two articles used quantitative methods, specifically survey and secondary data. The majority of the authors (Bhalla & Agarwal, Citation2021; Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022; Couch, Citation2021; Couch et al., Citation2021; Gopichandran & Subramaniam, Citation2021; Josyula et al., Citation2022; Singh & Kaur, Citation2022) analysed the qualitative data collected using thematic analysis and an intersectional approach. The quantitative researchers utilized logistic regression for the analysis of the data and also considered interaction effects.

All included studies considered how processes of power interact with one another and all conducted analyses at the intersections of class. Several were concerned with the ways class intersected with race (Bibi, Citation2021; Couch, Citation2021; Couch et al., Citation2021; Gilbert, Citation2021). Etowa et al. (Citation2021) were attentive to the intersections of citizenship with these other two axes and Han (Citation2021) considered the intersections of education and family status alongside class and race. Others focused on interactions of class and gender (Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022; Josyula et al., Citation2022; Singh & Kaur, Citation2022), class, gender, and sexuality (Abreu et al., Citation2021; Bhalla & Agarwal, Citation2021), or class, gender, and ability (Gandolfi et al., Citation2021; Gopichandran & Subramaniam, Citation2021). Finally, one study analysed the intersections of class, gender, and religion (Hopkyns, Citation2022). In our analysis of the included studies, we first identified the main findings of intersectional work related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, we tracked how intersectional methods of oppression, comparison, relationality, complexity, and deconstruction were used by the studies.

Main findings

Our thematic analysis of findings shows intersectional research related to the COVID-19 pandemic is paying attention to issues around the financial impacts of the pandemic, discrimination, gendered impacts, impacts of and on social ties, and implications for mental health. This literature shows that financial impacts of the pandemic have been felt unevenly, largely based on people’s intersecting social locations across multiple country settings (Abreu et al., Citation2021; Bhalla & Agarwal, Citation2021; Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022; Couch et al., Citation2021; Gandolfi et al., Citation2021). Financial strain was often experienced in meaningful ways, sometimes to the point of food insecurity by those facing simultaneous stressors of low income and other intersecting axes of oppression, such as gender, sexuality, or migration status.

Included literature also found discrimination, especially discrimination at the intersections of race, gender, family status, income, and migration status, created uneven barriers to service access during pandemic restrictions and lockdowns. Evidence showed this was especially impactful for those experiencing domestic violence in North Dakota, United States (Bibi, Citation2021), employer exploitation in Melbourne, Australia (Couch, Citation2021), and stigmatization from having COVID-19 in Chennai, India (Gopichandran & Subramaniam, Citation2021).

Studies included in this review also showed how gendered impacts of the pandemic were felt in intersectional ways across several country settings (Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022; Han, Citation2021; Hopkyns, Citation2022; Josyula et al., Citation2022; Singh & Kaur, Citation2022). These shifts occurred in a variety of sites. For example, the move to online work and schooling made private domains public. This initiated shifts in Muslim women’s economic and educational access when online participation threatened modesty and privacy in the United Arab Emirates (Hopkyns, Citation2022). Gendered shifts in public labour markets were felt in India (Josyula et al., Citation2022; Singh & Kaur, Citation2022), Mexico (Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022), and the United States (Han, Citation2021), leaving women with children and low levels of education especially vulnerable to economic hardship and unsafe working conditions across these settings. These studies together suggest that gendered impacts of the pandemic have not yet been met with effective policy responses.

The included studies also offered insight into a complex understanding of social ties within the context of the pandemic. Taken together, this intersectional analysis of social ties showed nuanced accounts of the ways social connection was both interrupted by pandemic restrictions, and how such ties helped with weathering such restrictions (Abreu et al., Citation2021; Bhalla & Agarwal, Citation2021; Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022; Couch et al., Citation2021; Gandolfi et al., Citation2021). For example, the loss of community connection in Mexico left many low-income women who make and sell corn tortillas particularly vulnerable to financial strain and food insecurity because their work relied on a network of mutual support for one another (Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022). Conversely, in the United States, Abreu et al. (Citation2021) found historical marginalization of 2SLGBTQ+ people meant many who were forced into homes with unsupportive family members still had community ties from which to draw resilience and strength. This was also the case for young refugees in Melbourne, Australia, who drew on their community to cope (Couch, Citation2021; Couch et al., Citation2021).

Finally, four studies focused on the pandemic’s impacts on mental health. Findings show that discrimination combined with financial stress resulted in those at the intersection of low income and queerness being particularly vulnerable to poor mental health and barriers to care access (Bhalla & Agarwal, Citation2021). Discrimination and social stigma for those infected with COVID-19 were shaped by intersections of gender, income, age, and ability, leading to mental health implications in India (Gopichandran & Subramaniam, Citation2021). Additionally, financial strain both among students (Gilbert, Citation2021) and those feeling domestic violence (Bibi, Citation2021) in the United States showed each group was left very vulnerable to decreased mental wellness throughout the pandemic.

Intersectional methods used

Along with gathering these significant insights, our review tracked the way studies of the COVID-19 pandemic used intersectional methods. We drew from Misra et al. (Citation2021) framework to consider the ways the concept of oppression was centred in this work, as well as how researchers have engaged with the comparison of axes of power, their own relationality, and the relationality of marginalization and advantage within the intersections under analysis. Finally, we considered how this work considered complexity within a social location, as well as how the authors may have reified or deconstructed socially constructed identity categories.

Oppression

All included studies deployed the concept of oppression when considering intersecting processes of marginalization. However, they varied in the degree to which they centred marginalized voices. In some cases, this was done very effectively. For example, Couch et al. (Citation2021) and Couch (Citation2021) centred the voices of refugee youth, explaining the roles youth took on during the pandemic often mirrored those they had taken during migration journeys. This left them with a skill set for coping based on resilience and family/community strength. The voices of the refugee youth explicitly called for their inclusion in settlement and public health policy moving forward, as their expertise in their own experiences makes them valuable leaders.

Most studies that were effective at bringing their participants’ voices from margin to centre used interviews as at least one of their methods. Bhalla and Agarwal (Citation2021) centred on the experiences and knowledge of working-class sexual minorities in India. Gopichandran and Subramaniam (Citation2021), Singh and Kaur (Citation2022), Abreu et al. (Citation2021), and Hopkyns (Citation2022) also used direct quotes to forefront the voices of their participants. In her PhD dissertation, Gilbert (Citation2021) also included the voices of her participants. However, in some cases, interviews did not result in the centring of marginalized voices. For example, Josyula et al. (Citation2022) used case studies to highlight the experiences of women waste pickers in India. This offered room to engage with these experiences, but the lack of participant quotes kept researchers’ voices and interpretations at the forefront. The same approach was used by Cárdenas-Marcelo et al. (Citation2022), with similar outcomes. In the only master’s thesis included in this review, Bibi (Citation2021) featured direct quotes from providers who offer services to those experiencing domestic violence but did not bring in voices of those themselves experiencing violence based on their vulnerabilities along intersecting axes of class and race. In their statistical analysis of crowdsourced data, Etowa et al. (Citation2021) were unable to forefront the voices of visible minority newcomers.

Comparison

Very few studies considered comparison or account for the ways attention to different axes of oppression and advantage may lend different insights when analysing their data. As one exception to this, Couch et al. (Citation2021) offered some comparison of social location in investigating the ways young refugees are able to access online resources compared to their parents. They found youth to be far more digitally literate than older family members. This was one reason young people were often given a lot of responsibility in their families during the pandemic and took on adult roles often similar to those they held during migration and settlement.

Relationality

We also tracked the ways the included articles used relationality in their studies. Once again, we drew on Misra et al. (Citation2021) who explain relationality as an intersectional research method that seeks to connect the marginalization of some to the over-privileging of others and demands researchers make their own power, positionality, assumptions, and biases explicit in their work. Like a comparison, a strong consideration of over-advantage in the analysis of the marginalization of others was lacking in the included studies. Moreover, a strong consideration of privilege appears to be missing within intersectional research about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, many studies did not make researcher positionality explicit, but some were exceptions. Couch et al. (Citation2021) considered the researchers’ positionality and the ethics of conducting research concerned with a group to which they do not belong. They explained the danger of inadvertently stereotyping or othering their participants and how they spent time pre-study unpacking their own biases and assumptions. Abreu et al. (Citation2021) also devoted an entire section of their paper to researcher positionality. Overall, the included studies offered little in terms of reflexivity.

Complexity and deconstruction

Misra et al. (Citation2021) offer a description of the intersectional method of complexity as the consideration of complexities within social categories beyond a Western reliance on binaries and separation. They also call on researchers to use deconstruction to break down these binaries and complicate categories of difference. We found these two methods extremely interrelated and thus considered them in partnership with one another.

In only three cases did the included studies thoroughly engage with complexity and deconstruction. Couch et al. (Citation2021) and Couch (Citation2021) both sought to complicate popular assumptions of refugees as in need of aid. They instead emphasized ways that refugee youth not only support their families and communities but also have capacities to lead public policy. Though they did not completely deconstruct the migrant/non-migrant binary (and perhaps should not in this study), they did disrupt popular assumptions and narratives of newcomer relations in the Global North. Additionally, Etowa et al. (Citation2021) called on policymakers to move beyond binary understandings of immigrant/native-born and recognize the ways visible minority newcomers may face unique barriers to healthcare access.

Analysis

Our findings show that class is a key social location under analysis in intersectional studies of the COVID-19 pandemic. All studies included in this review considered intersections of class and either race or gender. Citizenship, family status, migration, education, sexuality, religion, and ability were each considered alongside a combination of class, race, and gender in at least one study. This is interesting because our review of the findings of included studies identified themes beyond the pandemic’s financial impacts, including discrimination, gendered impacts, and social ties. This may suggest that current intersectional work is effective at grounding analysis in the matrix of domination (Collins, Citation2000).

Understanding the financial impacts of the pandemic through a lens of income inequity affords fuller analysis. The financial impacts of the pandemic have received major international attention since the beginning of the pandemic. Global and country-specific attention has highlighted increases in food insecurity (Béné et al., Citation2021), stagnation of financial markets and impacts to financial interconnectedness (Zhang et al., Citation2020), gender inequity (Dang & Nguyen, Citation2021), and increases in poverty (Vitenu-Sackey & Barfi, Citation2021). However, very little of the research on this topic has taken an intersectional approach and considered ways that intersecting and interlocking processes of oppression and privilege shape experiences with these impacts. Our findings show that there has been an analysis of the ways wealth has mitigated pandemic impacts.

Likewise, the theme of discrimination took a range of forms, from racism to homophobia, in the studies included in this review, similar to existing non-intersectional literature. Included studies focused on interpersonal discrimination such as anti-refugee and immigrant hostility, racism, homophobia, and stigmatization of the elderly and the poor. They also focused on systemic marginalization including intersectional discrimination of labour markets, which was particularly felt by racialized women with lower levels of education and who were mothers of young children (Han, Citation2021). Our findings show that little intersectional attention has been paid to anti-Asian racism and discrimination. Despite evidence showing high rates of discrimination in many countries (Hahm et al., Citation2021) and research surrounding vulnerabilities to and experiences with anti-Asian racism during the pandemic (Li & Chen, Citation2021; Litam & Oh, Citation2021), no intersectional targeted analysis of specific types of racism has been conducted related to the COVID-19 pandemic, including anti-Asian, anti-Black, and anti-Indigenous hate.

An intersectional analysis of studies within this review also highlighted the gendered impacts of the pandemic. This aspect has also gained much attention within the broader literature as researchers have investigated changes to reproductive labour responsibilities. However, this attention has again largely failed to consider intersecting oppressions. One review of gender equality across multiple country settings found increases in domestic work and increased vulnerabilities of essential workers impacted women in disproportionately negative ways, as they were already providing the majority of both domestic and essential work responsibilities across varied country settings (Carli, Citation2020). The review also found the rise of telecommuting and remote work benefited men more than women, though long-term impacts may hold possibilities for shifts in gender roles (Carli, Citation2020). A limited focus was placed on interactions of gender with social forces, such as income, education, and family status. The studies included in our review take aim at the absence of gendered policy responses to the pandemic. These studies depart from non-intersectional work not simply by adding on additional categories of difference in their analysis; rather, they contextualize gendered impacts within other processes of oppression, including precarious work, race, education, family status, religion, etc.

Impacts on social ties add nuance to non-intersectional analysis of isolation during pandemic restrictions. Non-intersectional analysis has heavily focused on the relationships between isolation during the pandemic lockdown and impacts on mental health (Birditt et al., Citation2021; Tei & Fujino, Citation2022). Our review found that the intersectional analysis of these impacts highlights ways that disruptions to social ties had deeply gendered and economic impacts, for example, with low-income women in various country settings relying on community support to meet financial and caregiving responsibilities (Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022). Alongside these impacts, intersectional analysis of social ties during the pandemic showed connections also remained in many cases and were a source of resilience, especially for those who were part of communities already marginalized pre-pandemic.

Finally, four studies (Bhalla & Agarwal, Citation2021; Bibi, Citation2021; Gilbert, Citation2021; Gopichandran & Subramaniam, Citation2021) that addressed the pandemic’s impacts on mental health showed how social positioning shaped people’s vulnerabilities to and experiences with poor mental health. These studies discussed how financial strain, stigma, and discrimination within their communities and social circles, and loss of access to previously available supports coalesced with difficulties related to pandemic lockdowns and restrictions. These studies suggested those facing multiple axes of marginalization were deeply vulnerable to abuse, loneliness, and poverty as a result of pandemic-related restrictions. Further, they were more likely to suffer poor mental health and well-being as a result.

These findings build on non-intersectional work investigating the mental health impacts of the pandemic (Castrellón et al., Citation2021; Koul & Nayar, Citation2022). Additionally, research investigating social determinants of health has analysed health and mental health through intersectional lenses far prior to the pandemic (Hogan et al., Citation2018; McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010). Therefore, the lack of literature considering health impacts related to COVID-19 is perhaps surprising. However, it should be noted that this review only includes studies published prior to 6 April 2022. More recent work may have added to this literature. As restrictions have only recently been lifted, and in uneven ways, the studies included in this review all spoke to the short-term impacts. Literature extending forward may consider long-term repercussions, especially to mental health in intersectional ways, and can adopt approaches from the broader literature on social determinants of health.

In terms of the use of intersectional research methods, the studies included in this review utilized oppression, comparison, relationality, complexity, and deconstruction to varying degrees. Abreu et al. (Citation2021), Couch (Citation2021), Couch et al. (Citation2021), Gilbert (Citation2021), Gopichandran and Subramaniam (Citation2021), Hopkyns (Citation2022), and Singh and Kaur (Citation2022) all very effectively centred voices of their participants whose marginalization along multiple axes held deep implications for them during the pandemic. They disrupted historical oppression by centring the voices of those far from power through the use of interviews and direct participant quotes. Others (Bibi, Citation2021; Cárdenas-Marcelo et al., Citation2022; Josyula et al., Citation2022) drew on participant voices by centring them to a lesser degree. Such efforts reflect feminist theory calling for the decentring of privileged voices (Hooks, Citation1984). However, this review shows that such centring has been primarily achieved through participant quotes, with engagement with methods such as participatory action research that would further empower participants lagging behind. Participatory action research has proven effective at decentring researcher bias, breaking down insider/outsider divides, and centring voices of those whose experiences are under study (Husni, Citation2020; Shadowen, Citation2015).

All included studies grounded their analysis in the concept of oppression and systemic power to some degree. This tenet of intersectionality appears to have been adopted effectively by studies deploying intersectional research methods. However, other methods have been taken up to a much lesser degree. Couch et al. (Citation2021) is the only included study to engage with all five of Misra et al. (Citation2021) methods and to meaningfully engage with comparison. Their investigation of refugee youth coping and leadership capacities during the first 2 years of the pandemic in Australia offered a rich explanation of many of these youths’ responsibilities within their families and communities. They were able to do this because they compared their intersecting social locations with those of their parents and older members of their communities.

Couch et al. (Citation2021) and Abreu et al. (Citation2021) were each explicit with respect to the researchers’ positionality and the ways their relationships to power impacted their relationships with participants and their interpretation of the data. These studies reflect other literature that suggests the importance of engaging with researchers’ own positionality in an effort to understand the power within research interactions and interpretation (Caretta & Jokinen, Citation2017; Lu & Hodge, Citation2019). Additionally, both Couch et al. (Citation2021) and Couch (Citation2021) sought to complicate popular assumptions of refugees as in need of aid by emphasizing the ways that refugee youth support their families and communities and have capacities to lead public policy. Etowa et al. (Citation2021) called for policymakers to move beyond binary understandings of immigrant/native-born to respond to the unique needs of racialized newcomers in accessing healthcare.

Conclusion

The results of this scoping review on intersectionality in research on the COVID-19 pandemic indicate that the financial impacts of the pandemic were disproportionately experienced among people with low-income status around the world. Drawing on Misra et al. (Citation2021) methods, our review was guided by oppression, comparison, relationality, complexity, and deconstruction to highlight how studies of the COVID-19 pandemic have operationalized an intersectionality framework. Only one study (Couch et al., Citation2021) utilized all five steps of Misra et al. (Citation2021) method. Findings from the review suggest intersectional research should focus on intersectional epistemology and theory through grounded methodological choices.

The scoping review suggests that intersectionality as a theory has been employed in research methods primarily through attention to power and articulations of oppression as systematic marginalization. Though other methodological tenets of intersectional research, such as comparison, relationality, complexity, and deconstruction, exist within intersectional research related to the COVID-19 pandemic, they have not yet been taken up with consistency or rigour. Perhaps most significantly, this research has yet to connect power and oppression to the relational over-advantage of some groups. Additionally, little work has been done with complexity as very few researchers have complicated binary and naturalized understandings of socially constructed and fluid social identities, such as gender. Connected to this, these studies have not deconstructed these social locations and identities in meaningful ways.

Ethical statement

Our study did not require ethical board approval, it is a scoping review, and we did not conduct human or animal trials.

Author Bio.docx

Download MS Word (16.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2024.2302305

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adedoyin Olanlesi-Aliu

Dr. Adedoyin Olanlesi-Aliu is a research coordinator at the Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta. Adedoyin holds a Ph.D. in Nursing from the University of Western Cape, South Africa. She completed her Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Alberta. Her area of research includes Access to health care for Black women, the Mental Health of Black Youth, and the intersection of gender and race.

Mia Tulli

Mia Tulli is a research coordinator for the Health in Immigration Policies and Practices Research Program at the University of Alberta. She has an MA in Political Science. Her research interests focus on intersections of gender, race, and migration with an emphasis on newcomers’ health and access to services in Canada.

Janet Kemei

Dr. Janet Kemei is an assistant professor at MacEwan university, Alberta, Canada. She holds a PhD in Nursing at the University of Ottawa. Her research interests include immigrant maternal and child health, access to healthcare and mental health services by Black women, and health inequities. Janet completed Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Alberta. This role enhanced her expertise in intersectional gender research and research with marginalized populations. She also holds a Master of Science in healthcare administration and has over 20 years of international experience in academia, clinical, management, and nursing research. She is a qualitative researcher and has published several articles in peer reviewed journals. She is also a reviewer in several peer reviewed journals. Janet incorporates her knowledge and expertise in nursing practice, research, policy, leadership, and education to teach nursing students by integrating career and educational goal explorations into course assignments. She exposes students to global and local health priorities, including diversity in health and health inequalities and inequities.

Glenda Bonifacio

Glenda Bonifacio is a professor in Women and Gender Studies at the University of Lethbridge. She is the author of Pinay on the Prairies: Filipino Women and Transnational Identities; editor of four books on feminism and migration, youth and migration, gender and rural migration, and gender and feminisms; co-editor of four books on women and religion, disasters in the Philippines, immigration in small cities, and racism in Alberta. She is a research fellow of the Network for Education and Research and Peace and Sustainability (NERPS) at Hiroshima University, and a member of the Advisory Board of the Small Islands Culture Research Initiative (SICRI).

Linda C. Reif

Professor Linda C. Reif is a Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Alberta, where she teaches international human rights law and international business law. She has published extensively on national human rights institutions, ombuds institutions, business and human rights, and international trade law. Her recent publications include Ombuds Institutions, Good Governance and the International Human Rights System (Brill/Nijhoff, 2d revised edition, 2020), co-authorship of Kindred’s International Law: Chiefly as Interpreted and Applied in Canada (Emond, 9th edition, 2019) and law review articles in the Harvard Human Rights Journal and Human Rights Law Review. Professor Reif has provided editing, consulting and academic services to organizations such as the Commonwealth Secretariat, International Ombudsman Institute (IOI), Academic Council on the UN System (ACUNS), Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) and the Uniform Law Conference of Canada. She has served as her Faculty’s Associate Dean (Graduate Studies), most recently in 2019–2022.

Valentina Cardo

Valentina Cardo is an associate Professor of Politics and Identity at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion Co-lead Winchester School of Art Director of Internationalisation. Valentina’s teaching and research expertise are located within the broader field of political communication, journalism, and gender politics. She has published her research on topics such as celebrity politics, e-government, gender and politics and popular culture and citizenship. Her research and teaching branch across three interconnected strands: questions of power, identity, and difference; the changing relationship between the media and modes of political and civic agency; and the impact of digital technologies on traditional communication strategies. She has taught on undergraduate and postgraduate courses on online media and democracy; gender, politics and media; and journalism. She also supervised a number of PhD students in these research areas.

Hannah Roche

Hannah Roche is Senior Lecturer in Twentieth-Century Literature and Culture at the University of York, where she teaches on queer modernism and intersectional feminism. She is the author of The Outside Thing: Modernist Lesbian Romance (Columbia University Press, 2019) along with essays in Modernism/modernity, Essays in Criticism, Textual Practice, and Modernist Cultures. Hannah is co-editor of the first Oxford World’s Classics edition of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (forthcoming 2024).

Natasha Hurley

Dr. Natasha Hurley is Professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland. She has also served as Senior Director of the Office of Interdisciplinary Studies, Director of Media and Technology Studies Unit and as both Director and Associate Director of Intersections of Gender Signature Area at the University of Alberta. She is the author of Circulating Queerness (Minnesota, 2018) and co-editor of Curiouser: on the Queerness of Children (Minnesota 2004). She has published on topics in 19th-century American literature, children’s literature, queer theory, trans studies, psychoanalysis, and intersectionality in venues including American Literature, Cultural Critique, ESC: English Studies in Canada, SAF: Studies in American Fiction, and Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures. She is co-winner of Foerster Prize for best essay in American Literature (2003), the Priestley Prize for best essay in ESC: English Studies in Canada (2011), and the Henig Cohen Prize for best essay or book chapter on Herman Melville (2018). Her research has been funded by a wide range of agencies including the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, and (with Dr. Bukola Salami as PI) the World Universities Network and Women’s and Gender Equality Canada.

Bukola Salami

Dr. Bukola Salami is a Professor at the Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, and a Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Nursing. Her main area of research is immigrant and Black peoples health. She has been involved in over 85 funded research projects totalling over $220 million. She has published over 110 papers in peer reviewed journals. In 2020, she founded the Black Youth Mentorship and Leadership Program at the University of Alberta with the support of 15 Black faculty members. In 2018, she created the African Child and Youth Migration Network, a network of 42 researchers across the globe focused on African child and youth migration. Dr. Salami has provided consultations to policymakers and practitioners at local, provincial, and national levels, including the Prime Minister of Canada and the Canadian Federal House of Commons (or parliament). Her work on mental health of Black youths contributed to the creation of a mental health clinic for Black populations in Alberta. She has received several awards for research excellence and community engagement.

References

- Abrams, E. M., & Szefler, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(7), 659–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4

- Abreu, R. L., Gonzalez, K. A., Arora, S., Sostre, J. P., Lockett, G. M., & Mosley, D. V. (2021). “Coming together after tragedy reaffirms the strong sense of community and pride we have:” LGBTQ people find strength in community and cultural values during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity10(1),140. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000516

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Asfaw, A. (2022). Racial disparity in potential occupational exposure to COVID-19. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(5), 1726–1739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01110-8

- Béné, C., Bakker, D., Chavarro, M. J., Even, B., Melo, J., & Sonneveld, A. (2021). Global assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 on food security. Global Food Security, 31, 100575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100575

- Bhalla, R., & Agarwal, S. (2021). Life in a pandemic: Intersectional approach exploring experiences of LGBTQ during COVID-19. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 4(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2021.1880204

- Bibi, D. E. M. E. (2021). Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on the domestic violence victim-serving agencies and professionals [ Doctoral dissertation]. North Dakota State University.

- Birditt, K. S., Turkelson, A., Fingerman, K. L., Polenick, C. A., Oya, A., & Meeks, S. (2021). Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological well-being. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa204

- Bowleg, L. (2020). We’re not all in this together: On COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), 917. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Browne, I., & Misra, J. (2003). The intersection of gender and race in the labor market. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 487–513. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100016

- Cárdenas-Marcelo, A. L., Espinoza-Ortega, A., & Vizcarra-Bordi, I. (2022). Gender inequalities in the sale of handmade corn tortillas in central Mexican markets: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 9(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-022-00119-6

- Caretta, M. A., & Jokinen, J. C. (2017). Conflating privilege and vulnerability: A reflexive analysis of emotions and positionality in postgraduate fieldwork. The Professional Geographer, 69(2), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2016.1252268

- Carli, L. L. (2020). Women, gender equality and COVID-19. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 35(7/8), 647–655. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2020-0236

- Castrellón, L. E., Fernández, É., Reyna Rivarola, A. R., & López, G. R. (2021, April). Centering loss and grief: Positioning schools as sites of collective healing in the era of COVID-19. In M. D. Young (Ed.), Frontiers in education (Vol. 6, p. 636993). Frontiers Media SA.

- Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. https://doi.org/10.1086/669608

- Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought. Routledge.

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity.

- Couch, J. (2021). ‘We were already strong’: Young refugees, challenges and resilience during COVID-19. Journal of Social Inclusion, 12(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.36251/josi217

- Couch, J., Liddy, N., & McDougall, J. (2021). ‘Our voices aren’t in lockdown’—Refugee young people, challenges, and innovation during COVID-19. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 4(3), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-021-00043-7

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139–167. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Crenshaw, K., & HoSang, D. (2023). Under the blacklight: The intersectional vulnerabilities that the twin pandemics lay bare. Haymarket Books.

- Dang, H. A. H., & Nguyen, C. V. (2021). Gender inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic: Income, expenditure, savings, and job loss. World Development, 140, 105296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105296

- Etowa, J., & Hyman, I. (2021). Unpacking the health and social consequences of COVID-19 through a race, migration and gender lens. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112(1), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00456-6

- Etowa, J., Sano, Y., Hyman, I., Dabone, C., Mbagwu, I., Ghose, B., Osman, M., & Mohamoud, H. (2021). Difficulties accessing health care services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Examining the intersectionality between immigrant status and visible minority status. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01593-1

- Gandolfi, E., Ferdig, R. E., & Kratcoski, A. (2021). A new educational normal an intersectionality-led exploration of education, learning technologies, and diversity during COVID-19. Technology in Society, 66, 101637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101637

- Gilbert, K. (2021). College student perspectives of food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic: A photo-elicitation narrative inquiry [ Doctoral dissertation]. Sam Houston State University.

- Goldman, N., Pebley, A. R., Lee, K., Andrasfay, T., Pratt, B., & Camacho-Rivera, M. (2021). Racial and ethnic differentials in COVID-19-related job exposures by occupational standing in the US. PloS One, 16(9), e0256085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256085

- Gopichandran, V., & Subramaniam, S. (2021). A qualitative inquiry into stigma among patients with covid-19 in Chennai, India. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 6(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2021.013

- Hahm, H. C., Ha, Y., Scott, J. C., Wongchai, V., Chen, J. A., & Liu, C. H. (2021). Perceived COVID-19-related anti-Asian discrimination predicts post traumatic stress disorder symptoms among Asian and Asian American young adults. Psychiatry Research, 303, 114084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114084

- Han, S. (2021, July). The impact of COVID-19 on gender inequality: A study on cross-sector inequality in the US. In ICEME 2021: The 2021 12th International Conference on E-business, Management and Economics, July 17–19, 2021, Beijing, China (pp. 379–387).

- Hankivsky, O. (Ed.). (2012). An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework. Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University.

- Harris, J., & Patton, L. (2019). Un/Doing intersectionality through higher education research. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1536936

- Hawkins, R. B., Charles, E. J., & Mehaffey, J. H. (2020). Socio-economic status and COVID-19–related cases and fatalities. Public Health, 189, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.016

- Hogan, V. K., de Araujo, E. M., Caldwell, K. L., Gonzalez-Nahm, S. N., & Black, K. Z. (2018). “We black women have to kill a lion everyday”: An intersectional analysis of racism and social determinants of health in Brazil. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.008

- Hooks, B. (1984). Feminist theory: From margin to center. South End Press.

- Hopkyns, S. (2022). Cultural and linguistic struggles and solidarities of Emirati learners in online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Futures in Education, 20(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103211024815

- Husni, H. (2020). The effectiveness of the social responsibility program for Islamic religious education through the participatory action research method. The Social Studies: An International Journal, 6(1), 103–116.

- Josyula, L. K., Murthy, S., Karampudi, H., & Garimella, S. (2022). Isolation in COVID, and COVID in isolation—exacerbated shortfalls in provision for women’s health and well-being among marginalized urban communities in India. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2021.769292

- Kabeer, N., Razavi, S., & van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. (2021). Feminist economic perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic. Feminist Economics, 27(1–2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2021.1876906

- Koul, S., & Nayar, B. (2022). Combating the COVID-19 disruption: Gauging job loss grief and psychological well-being of hospitality employees. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 82–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2022.2015240

- Lee, S. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2022). Pandemic grief scale: A screening tool for dysfunctional grief due to a COVID-19 loss. Death Studies, 46(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1853885

- Li, H., & Chen, X. (2021). From “oh, you’re Chinese…” to “no bats, thx!”: Racialized experiences of Australian-based Chinese queer women in the mobile dating context. Social Media + Society, 7(3), 20563051211035352. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211035352

- Litam, S. D. A., & Oh, S. (2021). Effects of COVID‐19‐related racial discrimination on depression and life satisfaction among young, middle, and older Chinese Americans. Adultspan Journal, 20(2), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsp.12111

- Lokot, M., & Avakyan, Y. (2020). Intersectionality as a lens to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for sexual and reproductive health in development and humanitarian contexts. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 28(1), 1764748. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1764748

- Lu, H., & Hodge, W. A. (2019). Toward multi-dimensional and developmental notion of researcher positionality. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00029

- Mason, N. C. (2010). Leading at the intersections: An introduction to the intersectional approach model for policy & social change. Women of Colour Policy Network.

- McPherson, C. M., & McGibbon, E. A. (2010). Addressing the determinants of child mental health: Intersectionality as a guide to primary health care renewal. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive, 42(3), 50–65.

- Misra, J., Curington, C. V., & Green, V. M. (2021). Methods of intersectional research. Sociological Spectrum, 41(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2020.1791772

- Mojtahedi, D., Dagnall, N., Denovan, A., Clough, P., Hull, S., Canning, D., Lilley, C., & Papageorgiou, K. A. (2021). The relationship between mental toughness, job loss, and mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 607246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.607246

- Motahedi, S. Aghdam, N. F. Khajeh, M. Baha, R. Aliyari, R. Bagheri, H. & Mardani, A.(2021). Anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon, 7.

- Nichols, S., & Stahl, G. (2019). Intersectionality in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(6), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1638348

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M. & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2021(21), S0895–4356 00040–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

- Ribeiro, K. B., Ribeiro, A. F., Veras, M. A. D. S. M., & de Castro, M. C. (2021). Social inequalities and COVID-19 mortality in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. International Journal of Epidemiology, 50(3), 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab022

- Rushovich, T., Boulicault, M., Chen, J. T., Danielsen, A. C., Tarrant, A., Richardson, S. S., & Shattuck-Heidorn, H. (2021). Sex disparities in COVID-19 mortality vary across US racial groups. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(6), 1696–1701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06699-4

- Shadowen, N. L. (2015). Youth as Researchers and Participants. In S. Bastien & H. B. Holmarsdottir (Eds.), Youth ‘At the Margins’. New Research – New Voices. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-052-9_17

- Sheridan Rains, L., Johnson, S., Barnett, P., Steare, T., Needle, J. J., Carr, S., Simpson, A., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Scott, H. R., Rees, J., Shah, P., Lomani, J., Chipp, B., Barber, N., Dedat, Z., Oram, S., Morant, N., Simpson, A., Papamichail, A., & Tzouvara, V.… Lever Taylor, B. (2021). Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: Framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01924-7

- Singh, N., & Kaur, A. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic: Narratives of informal women workers in Indian Punjab. In S. Hewamanne & S. Yadav (eds.), The political economy of post-COVID life and work in the global south: Pandemic and Precarity (pp. 17–50). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sobotka, T., Brzozowska, Z., Muttarak, R., Zeman, K., & DiLego, V. (2020). Age, gender and COVID-19 infections. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.24.20111765

- Tasker, J. P. (2021, January 27). Indigenous people should be priority for COVID-19 shots even amid shortage: Minister. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/indigenous-vaccinations-priority-marc-miller-1.5889826

- Tei, S., & Fujino, J. (2022). Social ties, fears and bias during the COVID-19 pandemic: Fragile and flexible mindsets. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01210-8

- Thacker, N. E., & Duran, A. (2022). Operationalizing intersectionality as a framework in qualitative grief research. Death Studies, 46(5), 1128–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1795749

- Thome, J., Deloyer, J., Coogan, A. N., Bailey-Rodriguez, D., da Cruz, E., Silva, O. A., Faltraco, F., Gudjonsson, S. O., Hanon, C., Hollý, M., Joosten, J., Karlsson, I., Kelemen, G., Korman, M., Krysta, K., Lichterman, B., Loganovsky, K., Marazziti, D., Maraitou, M., & Lebas, M.-C.… Fond-Harmant, L. (2021). The impact of the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental-health services in Europe. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 22(7), 516–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2020.1844290

- Vitenu-Sackey, P. A., & Barfi, R. (2021). The impact of covid-19 pandemic on the global economy: Emphasis on poverty alleviation and economic growth. The Economics and Finance Letters, 8(1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.29.2021.81.32.43

- Yang, L., Mao, B., Liang, S., Yang, J. W., Lu, H. W., Chai, Y. H., Wang, L., Zhang, L., Li, Q. H., Zhao, L., He, Y., Gu, X. L., Ji, X. B., Li, L., Jie, Z. J., Li, Q., Li, X. Y., Lu, H. Z. … ;Shanghai Clinical Treatment Experts Group for COVID-19. (2020). Association between age and clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19. The European Respiratory Journal, 55(5), 2001112. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01112-2020

- Zhang, D., Hu, M., & Ji, Q. (2020). Financial markets under the global pandemic of COVID-19. Finance Research Letters, 36, 101528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101528