ABSTRACT

This study explores adolescents’ awareness of the sources that inform online profiling and their perspectives on online targeted advertisements. It employs thematic analysis to analyse eight focus group discussions (N = 38) with adolescents (13–16 years) in Finland’s capital region. The study advances research on adolescents’ knowledge of the data gathered for online profiling by highlighting that adolescents infer that apart from previous online activities, data on their verbal conversations also inform targeted advertisements. The study also advances research on adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements by identifying that adolescents’ privacy expectations in the context of targeted advertisements are that data should not be collected without their awareness and commercial entities should not use data on previous conversations for profiling. This study also pinpoints that online profiling gives some adolescents a privacy-invasive feeling of being observed, and others have a boundary until which they consider online data collection for profiling permissible. Moreover, some adolescents express ambivalent views on online targeted advertisements. The findings reflect some adolescents’ acceptance of online profiling and knowledge gaps that can inform media literacy educators. The findings raise concerns about the opacity of online commercial data-gathering practices. Therefore, we urge corporations to demystify their data collection processes.

Impact summary

Prior state of knowledge

Previous research shows that some adolescents find online profiling, which forms the basis of online targeted advertisements, privacy-invasive. However, why adolescents find certain targeted advertisements more privacy-invasive and others less intrusive is underexplored.

Novel contribution

Adolescents find online targeted advertisements that draw on their previous verbal conversations more privacy-invasive than those based on their prior online activities,which reflects their privacy expectations in the context of online targeted advertisements.

Practical implications

Our findings reflect that some adolescents regard the tracking of their online activities by commercial entities as normal or permissible. Media literacy educators can use these results and devise educational programs to counter adolescents’ permissive attitudes.

Introduction

Adolescents are active users of various digital platforms (Livingstone et al., Citation2019; Stoilova et al., Citation2019a), and large amounts of user data are collected on these platforms (Livingstone et al., Citation2019). Observers contend that Instagram and Facebook even track users’ activities on other apps, websites and offline stores (Fowler, Citation2021). According to Simone Van der Hof’s (Citation2016) data typology, some of the data collected in digital environments is provided knowingly or voluntarily by users, for instance, through the content they share and their profile details. Van der Hof notes that a large chunk of data is also “given off” by users unknowingly or involuntarily. For example, information on location, browsing history, likes, clicks, time spent viewing a post, etcetera. Both kinds of data and possibly data from other sources are aggregated and analysed to generate users’ profiles, and profiling forms the basis of the targeted advertisements users receive on digital platforms (Van der Hof, Citation2016). Online targeted advertisements are “any form of online advertising that is based on information the advertiser has about the advertising recipient, such as demographics, current or past browsing or purchase behaviour, information from preference surveys, and geographic information” (Schumann et al., Citation2014, p. 59).

When it comes to adolescents, online profiling and targeted advertisements have broadly raised three main concerns. First, related to adolescents’ ability to critically evaluate the persuasive intent of targeted advertisements (Zarouali et al., Citation2020). Secondly, the online data collection practices underpinning profiling can threaten adolescents’ privacy (Stoilova et al., Citation2019a), and reports of possible data security breaches by popular apps like TikTok further exacerbate privacy threats (Milmo, Citation2023). Lastly, profiling can lead to advertisements and content being targeted based on users’ previous online actions, thus reducing their exposure to new ideas and choices, which interferes with adolescents’ right to receive information and freedom of thought as guaranteed in articles 13 and 14, respectively, of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (Milkaite & Lievens, Citation2019).

However, adolescents’ perspectives on commercial profiling and subsequent targeting in digital environments are underexplored (Stoilova et al., Citation2019b). Exploring adolescents’ perspectives can help understand what benefits and harms they identify in such practices, thus providing valuable insights into adolescents’ understanding of these issues. Given that online data collection practices are largely opaque (Livingstone et al., Citation2019), any critical evaluation of online profiling and targeting by adolescents requires, first and foremost, an awareness of the online data collection that precedes profiling (Zarouali et al., Citation2020).

Previous studies on adolescents’ knowledge of the data gathered for commercial profiling (Holvoet et al., Citation2021; Keen, Citation2020) had disparate results. Previous research exploring adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements has found that some adolescents considered online profiling privacy-invasive (Stoilova et al., Citation2019a). However, why they found profiling privacy-invasive is not explained. Moreover, why adolescents find certain targeted advertisements more privacy-invasive and others less intrusive and what privacy expectations in the context of targeted advertisements does that reflect is underexplored. Understanding the latter can provide some insights about (i) the collection of which or what user data adolescents find acceptable for profiling purposes and (ii) what their experiences of privacy-invasiveness depend on in the context of targeted advertisements. The present study tries to address the above-mentioned gaps by delving deeper into adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements. The study has two aims. First, it investigates which data do adolescents think inform their online profiles. Next, it explores adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements.

The data consists of eight focus group discussions (FGDs) (N = 38) conducted with adolescents aged 13–16 years in schools across Finland’s capital region. “Media (digital, data and critical) literacy” can play a significant role in improving adolescents’ understanding of the commercial repurposing of their data in digital environments (Stoilova et al., Citation2019a, p. 43). Finland has a strong tradition of media literacy education and is often regarded as an ideal example in this respect (Forsman, Citation2020), thus making it an interesting context for this study.

Framing gaps in previous literature

Previous research exploring adolescents’ knowledge of online data collection shows that adolescents observe that their previous online actions are connected to the targeted advertisements they receive (Holvoet et al., Citation2021; Keen, Citation2020). Keen (Citation2020) has employed qualitative interviews with adolescents (12–16 years) to explore their knowledge of the data collected for commercial profiling and the harms they perceive from it. Keen (Citation2020) notes that adolescents knew that their location data and profile details are used for their online profiling. In contrast, Holvoet et al.’s (Citation2021) study, which uses FGDs with adolescents (12–14 years) to explore their privacy management practices based on their knowledge of online data gathering, has somewhat different findings. While some of their participants understood that advertisers collected location information to personalise advertisements, they rarely mentioned that details provided while registering into apps were also used for profiling (Holvoet et al., Citation2021). Some participants in their study thought “eavesdropping through built-in microphones” on devices contributed to targeted advertisements, but most did not believe the latter to be true (Holvoet et al., Citation2021, p. 320).

Given the opacity of online data collection methods (Livingstone et al., Citation2019), for adolescents to critically evaluate online profiling and targeting, they should first be aware of the preceding online user data collection (Zarouali et al., Citation2020). In other words, before investigating if adolescents consider online profiling and targeting problematic or privacy-invasive, it is important to find out if they are even aware that they are surveilled in digital environments because online data collection processes are not transparent. Therefore, our first research question is:

RQ1: Which user data do adolescents think gets collected for their online profiling and subsequent targeting?

Previous research has also investigated adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements. Research informed by developmental psychology has focused on the age at which adolescents start developing advertising literacy. Advertising literacy is defined as the ability to understand and critically evaluate the persuasive intent of advertising messages (Hudders et al., Citation2017). A survey conducted among adolescents (12–17 years) shows that older adolescents (aged 16 years) possess more advanced critical processing abilities against targeted advertisements (Zarouali et al., Citation2020).

Besides advertising literacy, adolescents also need to understand how the covert online data gathering practices behind targeted advertisements can threaten their privacy (Zarouali et al., Citation2020). As noted above, Keen’s (Citation2020) study also explored adolescents’ conceptualisation of harm from online commercial surveillance. Keen found that adolescents considered online targeted advertisements helpful because they helped them find suitable products. In Keen’s (Citation2020) study, most adolescents did not find profiling and targeted advertisements privacy-invasive. While some adolescents were uncomfortable about companies collecting location data, their concerns centred around personal safety, reflecting that they were bothered about their “physio-spatial” privacy (Keen, Citation2020, p. 15).

Stoilova et al. (Citation2019a) have used FGDs to gather adolescents’ (11–16 years) perspectives on online profiling and targeting. Some of their participants trusted familiar companies to keep their data safe. Moreover, only a few participants in their study discussed the long-term ramifications of online profiling and targeting in reducing their exposure to new choices. Stoilova et al. (Citation2019a) also found that sometimes younger participants were more or equally aware of privacy issues compared to older ones, thus leading the researchers to observe that there is no specific age at which a new level of understanding is reached, and age cannot be the sole determinant of privacy-knowledge. In their study, some adolescents expressed a sense of creepiness about being profiled online. E-safety harms like hacking were adolescents’ primary concerns, even in relation to online commercial surveillance. Data leaks and misuse were remote concerns in the commercial context, although adolescents were aware of these possibilities (Stoilova et al., Citation2019a). While Stoilova et al. (Citation2019a) highlight the risks adolescents considered, they do not explain why adolescents found online data collection and profiling creepy or privacy-invasive.

Various theories have been used to explain users’ experiences of privacy invasiveness. Phelan et al. (Citation2016) have used the social presence theory to explain users’ (undergraduate students at a university) negative responses to online data collection and targeted advertisements. The theory proposes that users consider computers human agents and describe online data collection as creepy because users feel that they are “being watched” (Phelan et al., Citation2016, p. 5246). Sutanto et al. (Citation2013) explain (adult) consumers’ responses to targeted advertisements by using Petronio’s (Citation1991) information boundary theory, which proposes that people have mental boundaries beyond which they regard information sharing privacy-invasive. They show that consumers find the collection and use of their data for profiling and targeting intrusive beyond a certain point. If the collection of certain information is considered uncomfortable, consumers experience privacy transgressions (Sutanto et al., Citation2013). However, to our knowledge, the theories mentioned above have not been used to explain adolescents’ (13–16 years) experiences of privacy invasiveness, which could differ from that of adults (both young and old) due to varied awareness levels and developmental differences.

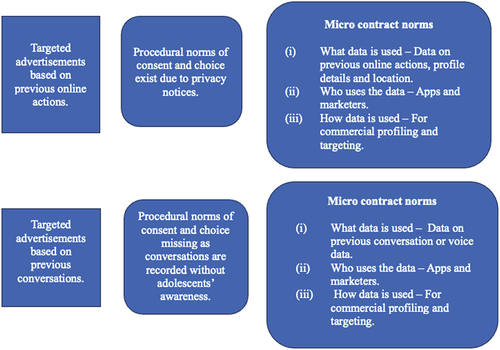

Previous research concerning adolescents’ perspectives on online profiling and targeting has also not explored why adolescents find certain online targeted advertisements more privacy-invasive than others and what that reflects about their privacy expectations in the context of online targeted advertisements. The social contract approach to privacy emphasises the importance of implicit agreements in any context (Martin, Citation2016). Martin (Citation2016) uses the social contract narrative to develop a framework for identifying users’ online privacy expectations and the cause of privacy violations. According to this framework, “procedural contract norms” of notice and choice (for example, through privacy notifications) are essential but not the only way to meet users’ privacy expectations. Martin proposes that in any context, “micro privacy norms” about what user data (information type) will be used, how it will be used and who will have access to users’ information also guide users’ privacy expectations. Users experience privacy transgressions if online data collectors violate “procedural contract norms” or make changes in the “microcontract” norms (Martin, Citation2016, pp. 557–559). To our knowledge, previous research has not explored adolescents’ privacy expectations in the context of online targeted advertisements, and the social contract framework has not been employed to unpack these expectations.

To address gaps in the existing literature discussed above, the present study delves deeper into adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertising. The second research question and sub-questions are:

RQ 2: What are adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements?

RQ 2.1: What are the benefits and disadvantages of targeted advertisements, according to adolescents?

RQ 2.2: Why do adolescents find online data collection and profiling for targeted advertising privacy-invasive?

RQ 2.3: What are adolescents’ privacy expectations in the context of online targeted advertisements?

Materials and methods

This article uses data from eight FGDs conducted in schools in Finland’s capital area to explore adolescents’ knowledge of being profiled online, their negotiation of online commercial privacy and their perspectives on targeted advertisements. Exploring children’s and young people’s perspectives involves focusing on their ways of understanding their lives and surroundings (Halldén, 2003 cited in Sparrman, Citation2009). We are guided by this idea and have used it to explore adolescents’ ways of interpreting their online environment. FGDs are ideal for gathering adolescents’ perspectives as they enable them to engage in conversations on a given topic (Horner, Citation2000). Therefore, we chose FGDs as the method of data collection.

Sample

The digital age of consent is the minimum age a user must attain before organisations can collect, process and store their data without parental approval (Pasquale et al., Citation2020). Although the GDPR recommends the digital age of consent to lie between 13 and 16, the age of digital consent in Finland is 13 years (Livingstone, Citation2018). Therefore, the sample consisted of adolescents aged 13–16 years. There were 38 participants (14 boys and 24 girls), and all the participants were recruited by their schools. The three schools that participated in our study are somewhat diverse. One school caters to pupils from all across Helsinki. The other two schools invite students from the pupil catchment area. One of these two schools is located in a district where the average annual income is higher than in the Helsinki capital region in general. The other school is in a district with an average yearly income lower than in the capital region.

Since small group sizes of 4–6 adolescents are recommended because they simulate everyday peer group interactions (Eder & Fingerson, Citation2002), each group consisted of 4–6 participants. Out of eight FGDs, five FGDs were conducted in Finnish and three in English. English was used in three FGDs because the school was bilingual (Finnish and English). Pupils attending bilingual schools are usually from various nationalities. For details on group composition and the language used in each FGD, please refer to . During the conversations, the participants in one group informed us that they had recently attended a school lesson on online privacy management. The data collection took place from December 2020 to May 2021.

Table 1. Summary of group composition.

The focus group discussions

As outlined in the guidelines for the responsible conduct of research in Finland formulated by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (Citation2019), informed consent was gathered from adolescents aged 15 years and above and from their parents if participants were under 15 years. Two researchers were present in every FGD. One acted as the moderator, while the other mainly observed. To ensure a clear understanding of informed consent, the consent terms were repeated before initiating the FGDs. Since the school environment can make participants feel they are being assessed, researchers must emphasise that there are no correct or incorrect answers (Punch, Citation2002). Gibson (Citation2012) recommends laying out ground rules like allowing everyone to speak and respecting everyone’s opinions. We highlighted these points before starting the FGDs. The average length of an FGD was 50 minutes.

Screenshots of targeted advertisements on Instagram were used to initiate the discussion. We showed the participants screenshots of two targeted advertisements from separate Instagram accounts. One from the researcher’s account and one from an adolescent’s account (after anonymising it). The aim of showing advertisements from two separate accounts was two-fold. One, to initiate discussions on targeted advertisements and ascertain if the participants recognised them. Second, to investigate what the participants thought about different users receiving different advertisements. In other words, we wanted to explore if the participants understood why different users receive different targeted advertisements and if they considered it problematic in any way. Each FGD was unique, and we asked some questions based on the discussions. Some probes we used during the discussions were: (i) How do you feel about apps knowing something about you so that they can suggest advertisements to you, (ii) why do you think different people get different targeted advertisements, and (iii) do you think targeted advertisements could have some bad sides? To avoid influencing participants’ accounts, we refrained from using words like privacy, harm and threat. We asked them to elaborate on their concerns only when the participants used these words.

During the FGDs, we also asked the participants to do a worksheet.Footnote1 On the worksheet, we asked the participants to list all the sources from where they thought apps get information about users. We wanted to find out if the participants list sources that include data shared knowingly (for instance, profile details), unknowingly or data that gets tracked as opposed to users explicitly giving that data (for example, data on what users watch, like, their search history) and data from any other sources. This helped us ascertain if the participants knew that their online actions were tracked and formed the basis of targeted advertisements and which activities they thought got recorded. The participants chose to do the worksheets in pairs or as a group. We also discussed their lists after they finished the worksheets so that the participants could further elaborate upon their observations.

Analysis strategy

The audio recorded FGDs were transcribed and anonymised. Pseudonyms have been used while quoting the participants. Transcriptions and items listed on the worksheet in Finnish were translated into English. The data was analysed using the six-step thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). These six steps include (i) familiarisation with the data, (ii) generating initial codes, (iii) searching for themes, (iv) reviewing themes, (v) defining and naming themes and (vi) producing the report (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). After undertaking multiple readings of the transcripts, the data was coded. A theoretical approach to coding wherein one codes the data with specific research questions in mind (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was adopted. The codes and accompanying data extracts were collated together to search for themes. The themes were reviewed multiple times after reading the codes and accompanying data extracts.

Understanding that users’ details and previous actions form the basis of targeted advertising

While discussing which data gets collected for profiling, as discussed below, our participants mentioned data on their (i) profile details, (ii) previous online activities (such as search history, posts liked and shared, and so on), (ii) location and (iv) previous verbal conversations.

Most participants in our study understood that users receive different targeted advertisements based on their profiles. All the participants were shown screenshots of targeted advertisements from the researcher’s and an adolescent’s Instagram accounts. In almost all the groups, participants started trying to identify which advertisement belonged to the adult’s account and which to the adolescent’s account. One advertisement was for a brand of muesli, and the other was for a shop called Flying Tiger of Copenhagen, which sells various items like stationery, accessories, etcetera.

“Those ads have probably come depending on the user. And probably the ad targeted to the child promotes a store that sells more products that are targeted to children, and the ad (targeted) to adults has those kinds of products that adults might buy, for example, food.” (Jutta,15)

The participants were asked to list the various sources from where apps like Instagram get information about users. We will discuss the sources they listed and their discussions.

The participants seemed to generally understand that the data they generate in digital environments forms the basis of targeted advertisements in apps like Instagram.

“No, it might be from like other apps that collect information as well, like from those things that you do.” (Matias,14)

One of the sources that the participants in all the groups listed was search history on apps and Google. They also discussed this.

“Well, those things you’re interested in suddenly come to your app, for example, on Instagram. If you search for cars on the internet, for example, or shoes, or clothes, those will come to your Instagram, too.” (Olli,15)

Other sources that the groups listed were the posts shared, liked and commented on, hashtags used and followed, people and topics they followed, time spent viewing a post and terms they accepted while registering into apps.

Many participants were cognisant that apps tracked their location and advertised to them.

“I have also noticed that your location affects the ads. Like when I was in Tiger (a shop) for TET (work-life familiarisation programme for middle school students in Finland), I started to get some ads for Tiger. I have only given Instagram, maybe Snapchat, permission, and that started to show me ads for Tiger specifically because I was working and spending a lot of time in Tiger. […]” (Kia, 16)

Participants also listed sources like demographic details entered in their profiles such as gender. While writing the list in groups, they clarified this to other participants.

Venla (15): I don’t understand why they ask about gender.

Kim (15): Because it’s for the ads.

Many participants deduced that their verbal conversations were recorded in addition to their online activities, and apps use this information to targeted advertisements.

“Yes, so like sometimes the apps like trace what you have been looking at and also some apps like listen to you and then they give you ads for like things you have been looking at and things you might be interested in because of the things you have looked at before.” (Tiina, 13)

When asked what they thought listened to their verbal conversations, the participants had varied responses. Some mentioned “apps”, and others said “smartphones”. Nevertheless, many participants discussed their experiences of receiving targeted advertisements based on previous conversations. They mentioned these experiences on their own without us bringing up this topic.

“I have noticed that if I have talked about something, for example wanting to buy some shirt, with my friend, you will get ads about exactly what you have talked about when you open the social media. For example, if you talk about some online store, you will get ads about the online store right away.” (Rhea, 15)

Their discussions and the sources the participants listed on the worksheets reflect that most participants understand that their actions in digital environments are tracked and form the basis of profiling and subsequent commercial targeting. Moreover, several participants’ accounts reflected that, due to their experiences, they thought that data on their previous verbal conversations were also used for online profiling and targeted advertisements.

Adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements

Our participants’ views on online targeted advertisements can be categorised into the themes listed and discussed below.

Helpful.

Helpful but also concerning.

Targeted advertisements encourage overconsumption.

Targeted advertisements hinder new choices and perspectives.

Targeted advertisements based on voice data are the creepiest.

Our participants also discussed online profiling that informs targeted advertisements. Their views can be categorised under the following themes that are listed and subsequently discussed below.

Profiling underlying targeted advertisements not disturbing.

Profiling underlying targeted advertisements creepy.

Helpful

Some participants noted that targeted advertisements sometimes helped them in finding relevant products.

“Sometimes it (profiling and targeting) can be good, if you really find something that you’ve looked for.” (Nick, 15)

Participants liked targeted advertisements because they corresponded with their interests.

“I don’t know. It’s kinda like ok because I wouldn’t like to see ads for things that I’m not even interested in.” (Leena, 14)

Helpful but also concerning

Some participants seemed ambivalent about targeted advertisements. They found them fun but also acknowledged that the data collection underlying profiling and targeting was disturbing.

“In one way it is fun and in another way it is very disturbing.” (Venla, 15)

This participant expressed unease over companies knowing users’ information.

“[…]. Maybe because it is personal information, in my view, companies shouldn’t know it”. (Venla, 15)

Another participant in this group mentioned that using profiling to serve users better was good but expressed concerns about the chances of data misuse.

“It’s kind of good because then you don’t get stuff that does not interest you at all, as long as there isn’t someone who starts to use it in a wrong way, it is a little scary.” (Paul, 15)

Targeted advertisements encourage overconsumption

A few participants talked about online targeted advertising as inimical because it showed products that users wanted to buy, which could persuade them to purchase those products, thus leading to overconsumption.

“Maybe they can target advertising, and you may also end up buying that product more easily when they know that you want to buy it, and when you can see it all the time it makes you feel like buying it away. And the threshold to buy decreases and you might buy more useless things.” (Rhea, 15)

Targeted advertisements hinder new perspectives and choices

Two groups discussed the long-term impact of online profiling and subsequent targeting on users’ perspectives and choices.

In one group, participants described how targeted advertising reduced variety by showing advertisements of the same brand.

Kia (16): Maybe I think that one of the bad sides is that […] it basically puts you in a narrow space and […] keeps giving you the same content if you search for it, and […] it basically kind of stops you from getting new stuff.

Suvi (15): It forms like a bubble.

Kia: Yes, […] like it can be hard to find new content because it keeps suggesting the same stuff to you all the time. […]

Pia (16): And then you don’t get the latest information. If they keep suggesting the same bike, you wouldn’t know if there was some new and better model […]

In another group, content suggestion based on the kind of news people had consumed previously was viewed as antithetical to developing multiple perspectives.

“I don’t think it’s such a problem in terms of advertisements that people get advertisements related to the items that they are interested in, but in terms of news. It would be better for people to get a lot of variety of news so that people would know more about the world […]. But if they don’t get the news because Google thinks they are not interested in it, they will not know that their way of thinking might be very wrong. “(Diana, 15)

Targeted advertisements based on voice data are the creepiest

As discussed previously, many participants inferred that data on their verbal conversations were collected for profiling and targeted advertisements. Product suggestions based on previous verbal conversations were viewed as a considerable privacy breach, even by participants who found online targeted advertising non-intrusive.

Interviewer: You mentioned that in general these targeted ads don’t bother you. But you mentioned that it is kind of creepy that they are listening to what you are saying. If it is so, then is it more of a problem than if they are tracking your behaviour online and tracking your data?

Matias (14): It’s like a violation of your privacy, and they can like listen to your conversations on a daily basis and know a lot about you that you wouldn’t want them to know.

It was somewhat challenging for the participants to pinpoint why they felt marketers collecting data on their verbal conversations was creepier or scarier than data collection on their previous online activities. Mostly, they just expressed how catastrophic it can be. However, in one group, the participants tried to articulate the reasons. One participant felt that the missing consent in audio recorded data made recording of verbal conversations more invasive.

“Cause you might, especially now that they don’t like tell you that they are listening to you, cause you like press the consent, you like accept. You kind of understand.[…]” (Tiia, 15)

Somewhat similarly, some participants mentioned that a lack of awareness about conversations being recorded meant that they had fewer chances of controlling the information they gave, which made such data collection more invasive to their privacy.

Tapio (15): I also think that recording audio or video is more like spying rather than recording your data from the actual phone (when you are scrolling) because then you know that you are on the phone, but when your phone is turned down and it’s recording your audio, then you are not actually on the phone, so it shouldn’t be then recording your audio.

Eva (15): At least you can control what you are doing on the phone (while browsing), at least up to some point.

We probed further to understand if accepting privacy terms and choosing cookies made this group feel more in control of their personal information. One participant’s explanation indicated that the cookie notification offered him a sense of choice that he could at least opt out of data collection if he wanted.

“Well, you don’t have to press the accept but when you are like pressing the accept you give consent.” (Jesse, 15)

Profiling underlying targeted advertisements not disturbing

Some participants did not find targeted advertisements disturbing.

“I would say that they aren’t useful, but they aren’t harmful either” (Tom,15).

One of the justifications the participants provided for not finding profiling and targeting disturbing was that they trusted popular apps like Instagram.

“Feel ok, like it won’t go anywhere, the information.” (Mikko,14)

In one group, a few participants discussed that older and familiar apps garnered more trust.

“There have been discussions about this, for example, about how especially the newer apps may feel unsafe because you don’t really know about them […].” (Anu, 15)

A few participants’ accounts reflected that they had a certain boundary up until which they were permissive to online data collection. However, in one group, some participants warned their friends about the extent of information apps can collect.

Miri (15): I mean, if they know some basic things about me, like I like dresses, then it’s ok, […] but if they know more, then it can be scary.

Tom (15): Yes, but with your information, like location, […] they can […] figure out even a lot more like where you live and your address.

Paul (15): Yes, because they look at your IP address and get a lot of information from that.

Profiling underlying targeted advertisements creepy

Some participants (both younger and older adolescents) found online profiling and subsequent targeting creepy.

“I also think that it’s a bit creepy, and sometimes I just think that how many things about me do they know more than what I personally know about myself.” (Katri, 13)

One reason the participants gave for feeling creepy about online data collection and profiling was that they felt they were being observed.

“Well, you know, because somebody, or maybe not somebody but something, for example, artificial intelligence, can find out what you like and so on, something like observes you or, I mean, can see what products you like and can advertise them directly to you. It makes you feel like someone is watching what you do.” (Rani, 15)

While discussing the possible harm that data collection by apps like Instagram could pose, a few participants mentioned e-safety breaches like hacking.

“It feels like what if they want to use it for something else than advertising, and that someone who I don’t want to can have information about me, like my address or something else personal […]. And hacking has increased lately, so it feels like what if someone knows things about me, they can use the information against me and make my life difficult or even ruin it.” (Diana, 15)

A few participants also discussed possible risks like their data getting sold. However, they voiced these concerns after being probed further. Therefore, these did not seem to be their primary concerns.

“They can sell it (information) to other companies.” (Leena, 14)

Some participants’ accounts reflected that they were apprehensive about apps knowing their location because they feared for their safety.

“It would be horrible if someone would look at your location all the time. I have listened to enough criminal podcasts in which someone hacks your phone and looks at your location and comes to murder you.” (Diana, 15)

While discussing why digital commercial profiling seemed creepy, some participants expressed the need to learn more about the commercial repurposing of their data. They wanted schools to discuss these topics in more detail.

Jutta (15): Yeah, it would be nice to get correct information about these things.

Rani (15): For example, in school, because they don’t talk about these things very much.

Discussion

Our findings concur with previous research which shows that adolescents discern that their previous online actions (Holvoet et al., Citation2021; Keen, Citation2020), location information (Holvoet et al., Citation2021; Keen, Citation2020) and demographic details (Keen, Citation2020) form the basis of online targeted advertisements. In Holvoet et al.’s (Citation2021) study, some participants thought that data from verbal conversations gets used for personalising advertisements, but most did not believe so. In contrast, in our research, due to their experiences, many participants believed that data on previous verbal conversations informed profiling and targeted advertisements.

As observed in Keen’s (Citation2020) research, some participants in our study also found online targeted advertisements helpful. A few participants in our study expressed concerns over how targeted advertisements may encourage overconsumption because they correspond with their interests and could entice them to buy those products. Zarouali et al. (Citation2020) found that older adolescents (aged about 16 years) are better at critically evaluating the persuasive intent of targeted advertising messages. Although the adolescents who discussed this in our study were older (15–16 years), we also had some participants from this age group who appreciated the accuracy of targeted advertisements without much critical reflection. It is possible that these participants knew about online targeted advertisement’s persuasive intent but did not discuss it during the FGDs. Nevertheless, based on our findings, we cannot conclusively suggest that age influences adolescents’ critical abilities towards targeted advertising. In our research, a few participants discussed the long-term implications of online commercial profiling and targeting in hindering novel perspectives. Stoilova et al. (Citation2019a) had similar findings.

Like in Keen’s (Citation2020) research, some of our participants as well did not consider online profiling disturbing. There seemed to be two reasons for it. Firstly, akin to Stoilova et al.’s (Citation2019a) findings, a few of our participants also trusted familiar apps. Additionally, we found that a few adolescents considered online profiling nonintrusive because they seemed comfortable with a certain amount of their online data being gathered. This could be a reflection of the information boundary theory, which proposes that consumers have mental thresholds beyond which they consider online data collection privacy-invasive (Sutanto et al., Citation2013).

Congruent with Stoilova et al.’s (Citation2019a) results, some participants in our study as well found the profiling underlying targeted advertisements creepy and identified data hacking and misuse as possible risks. Like in Keen’s (Citation2020) study, a few of our participants also expressed unease over the collection of location data, reflecting they valued their physio-spatial privacy. Additionally, we found that some adolescents found online profiling creepy because it gave them a feeling of being observed. This could be explained by the social presence theory, which proposes that individuals treat computers as human agents and online surveillance often gives users feelings akin to being observed (Phelan et al., Citation2016). Both younger and older participants in our study expressed discomfort with online profiling, which conforms with Stoilova et al.‘s (Citation2019a) observation that there is no specific age at which adolescents’ privacy awareness develops. However, given that the age variance among our limited number of 38 participants was only three years and there were fewer participants aged 13–14 years (), we cannot conclusively suggest that age does not impact privacy awareness. Moreover, to avoid influencing participants’ responses, we did not use words like “privacy” and “threats” but discussed further when participants expressed privacy concerns. Due to the absence of any direct questioning, we cannot make claims on all participants’ privacy awareness.

Furthermore, we found that some adolescents considered online targeted advertisements helpful but also concerning. Adolescents’ non-dichotomous views indicate that they acknowledge the privacy invasiveness of profiling but also appreciate relevant advertisements and content.

Participants’ privacy expectations and online targeting based on voice data

Additionally, we identified that adolescents regarded targeted advertising based on previous verbal conversations (recorded by devices or apps) as more privacy-invasive than advertisements based on previous online activities. They gave two reasons for feeling so. One, because their consent was not sought in case of the recording of conversations. Another related reason they identified for feeling perturbed was that when data on their online activities gets collected, they feel they are aware and, therefore, have a higher sense of control. Whereas, in the case of voice data being recorded, they are unaware and cannot control the information they give away.

When we apply the social contract framework (Martin, Citation2016) to adolescents’ perspectives, we can pinpoint that online targeted advertisements based on voice data are seen as more privacy-invasive because the procedural norms of notice and choice are disrespected as voice data is recorded without adolescents’ awareness or consent and changes are also made to the micro privacy norms regarding what data is used when data on previous conversations (voice data) is utilised for profiling, as illustrated in . This shows that in the context of online targeted advertisements, adolescents’ privacy expectations are that data should not be collected without their awareness and voice data should not be used for profiling. The former indicates that adolescents’ experiences of privacy invasiveness from targeted advertisements depend on how data for profiling gets collected, and the latter suggests that the monitoring of previous online actions is expected or “normal” and hence permissible.

Figure 1. Applying Martin’s (Citation2016) social contract framework to unpack privacy violations in voice based targeted advertisement.

Implications

Regarding the surveillance of their previous online activities as “normal” indicates an acceptance of this practice by some adolescents, even though it is highly privacy-invasive. Moreover, when adolescents’ concern centres on how data gets collected for profiling rather than on the intrusive practice of online profiling, they are more likely to accept the latter uncritically. A few adolescents found targeted advertisements helpful but also concerning, which could be interpreted in two ways. It can be regarded as an acknowledgement of the privacy-invasiveness of commercial surveillance. However, the appreciation of relevant advertisements or content could also indicate an acceptance of profiling. Permissive attitudes could lead to commercial surveillance remaining unquestioned by adolescents, thus highlighting the need to counter permissiveness by raising adolescents’ awareness of the ramifications of such practices.

The finding also raises concerns about the opacity of online commercial surveillance. Whether companies listen to private conversations and target users with advertisements remains an open question, and studies have both supported and denied such claims (Kröger & Raschke, Citation2019). Moreover, there are contentions that marketers are developing, and possibly already using, mechanisms to utilise voice data to improve personalisation (see for example, Turow, Citation2021). We cannot conclusively suggest that companies use data from verbal conversations for targeted advertising, but we also think it is important to take adolescents’ concerns and experiences seriously. Therefore, we urge corporations to be more transparent about the data they use for online profiling.

We also consider how our findings are situated in the Finnish context, with its high emphasis on media literacy in schools. Our participants were generally aware of which data gets tracked for commercial purposes. However, whether information is taken from private conversations or other sources does not make much difference to the possibility of data exploitation and the repercussions on the subject (Kröger & Raschke, Citation2019). Therefore, some adolescents’ relative comfort with their online actions getting monitored reflects grey areas in their knowledge. Moreover, participants’ awareness levels seemed to differ. While some critically reflected on commercial digital surveillance, a few others considered it relatively unproblematic. Some participants even wished schools would teach more about the commercial repurposing of online data. These insights regarding adolescents’ knowledge gaps can be used by media literacy educators in Finland.

Limitations and contributions

We acknowledge some limitations in our study that open avenues for future research. Firstly, adolescents’ knowledge can differ due to factors like technical skills and socio-economic backgrounds, among others (Livingstone et al., Citation2019). Therefore, more research in different countries and among varied socio-demographic consumer groups can reveal social and cultural differences or new perspectives that were not covered in our study as it was limited to the Finnish capital region. Second, the study has identified that adolescents found targeted advertising based on prior verbal conversations more privacy-invasive than those based on data on their previous online activities. However, only one group could articulate the reasons for feeling so and qualitative methods limit drawing generalisations to populations. Therefore, quantitative studies could be conducted to reveal how targeted advertising based on previous verbal conversations and online activities are associated with adolescents’ experiences of privacy-invasiveness.

Despite the limitations identified above, the present study makes some significant contributions. It contributes to existing research exploring adolescents’ knowledge of the data collected for profiling by highlighting that adolescents deduce that data on their verbal conversations also informs commercial profiling and targeting. The study also advances research investigating adolescents’ perspectives on online targeted advertisements by pinpointing why some adolescents find online profiling privacy-invasive. Secondly, the study identifies adolescents’ privacy expectations in the context of online targeted advertisements. Thirdly, it highlights that some adolescents have an imaginary boundary up until which they find online data gathering permissible. Lastly, the study identifies ambivalent views on online targeted advertisements among some adolescents.

Conclusions

To conclude, our thematic analysis of eight FGDs (N = 38) with adolescents aged 13–16 years in Finland’s capital region shows that our participants thought that data on their location, demographics (age and gender), previous online actions and past conversations gets collected for online profiling. Our participants had multiple perspectives on online targeted advertisements. Some participants found targeted advertisements helpful, whereas a few others found them helpful but also concerning. Some thought targeted advertisements encourage overconsumption. A few others noted that targeted advertisements hinder new perspectives and choices. While some participants found the profiling underlying targeted advertisements non-disturbing, there were some others who found it creepy because it gave them a feeling of “being watched”. Several participants regarded targeted advertisements based on voice data as the creepiest, which reflects that adolescents’ privacy expectations in the context of targeted advertisements are that data should not be collected without their awareness and commercial entities should not use data on previous conversations for profiling. We recommend raising adolescents’ awareness about the ramifications of commercial surveillance and urge corporations to make their data collection process for profiling transparent.

Details of ethics approval

A specialist from the Human Sciences and Ethics Committee, University of Jyväskylä was consulted before undertaking the data collection. Based on the description of the research design, the need for a separate ethical approval was ruled out by the specialist from the Human Sciences and Ethics Committee, University of Jyväskylä. The university follows the guidelines for the responsible conduct of research in Finland (2019). As per these guidelines, we were asked to gather informed consent from children if they were 15 years and above and from parents in case of children aged below 15 years. We followed these guidelines and gathered informed consent. A description of this is also provided in the Materials and methods section of the manuscript. Since the research design did not meet the criteria of research that would require a separate ethical approval (a description of such criteria was provided to the researchers by the Human Sciences and Ethics Committee, University of Jyväskylä), a separate ethical approval was not carried out.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable and helpful comments. We are grateful to the schools that participated in this study and thank the participants who contributed their time to this study. We would also like to thank Matilda Holkkola for her help as a research assistant in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sonali Srivastava

Sonali Srivastava is a doctoral researcher at the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research focuses on children as consumers in digital environments. Sonali’s research interests include children’s consumer culture, visual culture, and children’s online privacy.

Terhi-Anna Wilska

Terhi-Anna Wilska is Professor of Sociology at the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research covers consumer behaviour, sociology of consumption and consumer culture. Recent topics of interest include digitalisation of consumption, social media and young people, and sustainability in consumption and everyday life.

Jussi Nyrhinen

Jussi Nyrhinen is a postdoctoral researcher in sociology at the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy in University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Nyrhinen has been involved in studies investigating digitalisation in the retail business, and the consequent disruptions in consumer behaviour, retail spaces and local retail firms’ strategies and policies.

Notes

1. Additional information – We were guided by Van der Hof’s (Citation2016) data typology in designing this worksheet. According to this typology, online targeted advertisements are based on inferred data or profiling. Inferred data is derived by analysing data shared knowingly (but not necessarily intentionally) and unknowingly by users and possibly data from other sources, usually using algorithms (Van der Hof, Citation2016).

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(77), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Eder, D., & Fingerson, L. (2002). Interviewing children and adolescents. In J. F. Gubrium & J. A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method (pp. 181–201). Sage.

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity guidelines. (2019) . The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland. TENK.

- Forsman, M. (2020). Media literacy and the emerging media citizen in the Nordic media welfare state. Nordic Journal of Media Studies, 2(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.2478/njms-2020-0006

- Fowler, G. A. (2021, September 29) How to block Facebook from snooping on you. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/08/29/stop-facebook-tracking/

- Gibson, J. F. (2012). Interviews and focus groups with children: Methods that match children’s developing competencies. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 12(5), 473–483.

- Holvoet, S., De Jans, S., De Wolf, R., Hudders, L., & Herrewijn, L. (2021). Exploring teenagers’ folk theories and coping strategies regarding commercial data collection and personalized advertising. Media and Communication, 10(1), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4704

- Horner, S. D. (2000). Using focus group methods with middle school children. Research in Nursing and Health, 23(6), 510–517. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200012)23:6<510:AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-L

- Hudders, L., De Pauw, P., Cauberghe, V., Panic, K., Zarouali, B., & Rozendaal, E. (2017). Shedding new light on how advertising literacy can affect children’s processing of embedded advertising formats: A future research agenda. Journal of Advertising, 46(2), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269303

- Keen, C. (2020). Apathy, convenience or irrelevance? Identifying conceptual barriers to safeguarding children’s data privacy. New Media Society, 24(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820960068

- Kröger, L. J., & Raschke, P. (2019). Is my phone listening in? On the feasibility and detectability of mobile eavesdropping. In S. Foley (Ed.), Data and applications security and privacy XXXIII (pp. 102–120). Springer International Publishing.

- Livingstone, S. (2018). Children: A special case for privacy? Intermedia, 46(2), 18–23.

- Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Children’s data and privacy online: Growing up in a digital age: An evidence review. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Martin, K. (2016). Understanding privacy online: Development of a social contract approach to privacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(3), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2565-9

- Milkaite, I., & Lievens, E. (2019). Children’s rights to privacy and data protection around the world: Challenges in the digital realm. European Journal of Law and Technology, 10(1). https://ejlt.org/index.php/ejlt/article/view/674/913

- Milmo, D. (2023, March 8). TikTok unveils European data security plan amid calls for US ban. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/mar/08/tiktok-european-data-security-regime-us-ban-social-video-app

- Pasquale, L., Zippo, P., Curley, C., O’Neill, B., & Mongiello, M. (2020). Digital age of consent and age verification: Can they protect children? IEEE Software, 39(3), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2020.3044872

- Petronio, S. (1991). Communication boundary management: A theoretical model of managing disclosure of private information between marital couples. Communication Theory, 1, 311–335.

- Phelan, C., Lampe, C., & Resnick, P. (2016). It’s creepy, but it doesn’t bother me. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 5240–5251. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858381

- Punch, S. (2002). Research with children: The same or different from research with adults? Childhood, 9(3), 321–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568202009003005

- Schumann, J. H., von Wangenheim, F., & Groene, N. (2014). Targeted online advertising: Using reciprocity appeals to increase acceptance among users of free web services. Journal of Marketing, 78(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0316

- Sparrman, A. (2009). Ambiguities and paradoxes in children’s talk about marketing breakfast cereals with toys. Young Consumers, 10(4), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610911007139

- Stoilova, M., Livingstone, S., & Nandagiri, R. (2019a). Children’s data and privacy online: Growing up in a digital age. Research findings. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Stoilova, M., Nandagiri, R., & Livingstone, S. (2019b). Children’s understanding of personal data and privacy online – a systematic evidence mapping. INFORMATION COMMUNICATION & SOCIETY, 24(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1657164

- Sutanto, J., Palme, E., Tan, C. H., & Phang, C. W. (2013). Addressing the personalization-privacy paradox: An empirical assessment from a field experiment on smartphone users. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1141–1164. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.4.07

- Turow, J. (2021). The voice catchers: How marketers listen in to exploit your feelings, your privacy, and your wallet. Yale University Press.

- Van der Hof, S. (2016). I agree … or do I? A rights-based analysis of the law on children’s consent in the digital world. Wisconsin International Law Journal, 34(2), 409–445.

- Zarouali, B., Verdoodt, V., Walrave, M., Poels, K., Ponnet, K., & Lievens, E. (2020). Adolescents’ advertising literacy and privacy protection strategies in the context of targeted advertising on social networking sites: Implications for regulation. Young Consumers, 21(3), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-04-2020-1122