ABSTRACT

Drawing upon Vygotskian and Piagetian learning theories, recent research reveals children’s learning can be maximized through a specific Active Playful Learning (APL) approach called guided play. The deepest and most engaging learning happens during guided play. In guided play, adults might prepare an environment and set a learning goal, but children get to direct their own play and exploration towards that goal. Research suggests that guided play fosters math skills, shape knowledge, task switching, spatial vocabulary, literacy, language, social interaction, and physical activity. The intersection of play and the intentionality of having a learning goal holds great potential as a pedagogical approach that can be applied to technology, community spaces, and to classrooms. We describe current directions in: (1) the conceptualization of guided play, (2) areas for implementing this approach in formal and informal education (including television and digital applications, as in the case of Sesame Street), and (3) future opportunities and challenges.

The recent resurgence of play research has built a strong evidence base for playful approaches to early childhood pedagogy both in and out of school. Research reveals that children can learn and develop social, cognitive, executive functioning, and language skills from play, especially when learning goals are intentionally integrated into a playful pedagogical approach from the start (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2009; Skene et al., Citation2022). Grounded in developmental theory and recent evidence, we present a whole-child pedagogical approach known as Active Playful Learning. Defined broadly, Active Playful Learning (APL) is a context in which children learn content or skills through intentional play.

Play exists along a spectrum, across which many types of play benefit children’s learning, from autonomy development during free play (Colliver et al., Citation2022) to guided play, to direct instruction offered in a playful way. However, the conditions that promote the highest-quality play are child-initiated, adult-directed, and contain a learning goal: guided play (Weisberg et al., Citation2016; Zosh et al., Citation2018).

Guided play and active playful learning

Recent research suggests that children’s learning can be maximized through guided play, a specific Active Playful Learning approach. Guided play occupies the space between free play and direct instruction because adults formulate a clear learning or curricular goal, but children are the explorers and discoverers who actively engage in their own learning towards that goal. Rather than serve as directors, adults prepare the environments or gently guide student learning (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2009; Skene et al., Citation2022; Weisberg et al., Citation2016). Guided play fosters math skills, shape knowledge, task switching, spatial vocabulary, literacy, language, social interaction, and physical activity (Skene et al., Citation2022). The intersection of play and the intentionality of a clear learning goal holds great potential as a pedagogical approach that can be applied to technology (Hassinger-Das & Palti, Citation2020), community spaces (Pesch et al., Citation2022), and to classrooms (Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, et al., Citation2022).

The active playful learning model

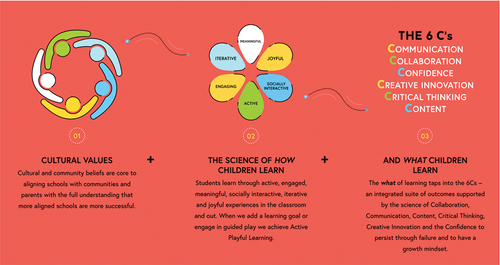

Active Playful Learning is founded on the science of learning through a three-part equation that engages cultural and community values + the “how” of playful learning (the characteristics that comprise playful learning) + the “what” of playful learning (the skills children need to thrive, known as the 6Cs: Collaboration, Communication, Content, Critical thinking, Creative innovation, and Confidence), shown in . The 6Cs represent an evidence-based approach to the kinds of skills children need to thrive in the 21st century. The APL model is a response against the “schoolification” trend, in which toddlers’ play time is replaced with direct instruction, which sapped the joy out of learning (Blinkoff et al., Citation2023; Ring & O’Sullivan, Citation2018; Simoncini & Lasen, Citation2021). This schoolification marked an instructional shift towards didactic lessons (Bassok et al., Citation2016; Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2022). Play was, as Head Start founder Ed Zigler put it, under siege (Zigler & Bishop-Josef, Citation2004). In a climate of disappearing play, the Active Playful Learning model harnesses the three-part equation for pedagogical change that centers the science of playful learning.

Figure 1. The three-part formula for active playful learning (adapted from activeplayfullearning.com).

Community and cultural values

The first part of the APL Model reflects the importance of incorporating the dynamic expertise and diverse experiences of community members to ensure that cultural values and goals important to the target community are embedded in playful learning environments and activities. While “community” can be defined in different ways, the main point is that pedagogical practices, learning activities, and spaces designed to spark playful learning will be most effective when local representatives (e.g., residents, grassroots organizations, community leaders) have a voice at the table. Communities can be engaged by leveraging participatory-design practices like community co-design and prototype play-testing (Bermudez et al., Citation2023). Community values and ideas are then aligned with the scientific foundation that supports Active Playful Learning (for a discussion of incorporating community values into playful learning in the context of Sesame Street, see Foulds et al., this issue). When community values and practices are integrated with the science supporting playful learning and the 6Cs, there is increased ownership, more meaningful learning opportunities, and greater sustainability of the initiative in which the learning experiences take place (Hadani & Vey, Citation2021; Hassinger-Das & Fletcher, Citation2023).

Several projects representing the Playful Learning Landscapes (PLL) initiative – a joint endeavor between Temple University, the Brookings Institution, and the Playful Learning Landscapes Action Network (PLLAN) – provide examples of how to create culturally representative and meaningful playful learning activities and tools. Thus far, PLL has curated active playful learning experiences in the everyday spaces where children and families spend time, such as parks, libraries, laundromats, bus stops, and grocery stores. To design these spaces, community engagement is essential. One of the first PLL spaces was created in Philadelphia, PA. Members of the research team met with community members living in the target neighborhood, who voiced their desire to place activities in a community space that held cultural and historical value – a bus stop adjacent to a lot where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave a speech in 1965 (Hassinger-Das, Palti, et al., Citation2020).

Community values have also been elicited by inviting community members to participate in in-person and online co-design workshops that utilize participatory-design practices. As an example, a PLL project being implemented in a Southwestern city in the United States with a predominantly Spanish-speaking community partnered with nearly 50 caregivers to co-design playful learning activities for several community spaces. Workshops involved activities such as storytelling, arts and crafts, play testing, and value-mapping activities that provided caregivers the agency to design local spaces according to their vision. From these community-centered workshops emerged a series of bespoke playful learning activities, including an abacus bus stop and a lotería park game that reflect both the community’s cultural heritage and their lived experiences, while encouraging intergenerational learning (Bermudez et al., Citation2023; Pesch et al., Citation2022). By intentionally engaging with communities that a target intervention or project is meant to serve, everyday spaces can be transformed into culturally relevant learning hubs that combine community values with the other two pieces of the APL equation: the “how” and the “what” of learning.

The how of learning: Characteristics of active playful learning

Play is an active process involving physical, cognitive, and emotional engagement. Culling from a large scientific literature, Zosh et al. (Citation2018) suggested that guided play is best defined through a suite of characteristics. In play, children are active in that they are doing an activity in which they have agency and are “minds on.” Play is also all-encompassing and engaging in ways that support dedicated focus rather than distraction. Play is meaningful to the child and makes connections between what the child already knows and new knowledge. Social interaction is also a core characteristic of play. While play can occur in isolation, social exchanges enhance the learning that comes from playful activities. Play is iterative and prompts curiosity and exploration and the child continues to discover and learn in new ways that build on the foundation. Finally, play is joyful. These characteristics, taken together, not only form a definition of play, but also map onto the ways in which children learn best. Thus, adding the final characteristic of a learning goal enables teachers and parents to harness the way the brain naturally learns towards the accomplishment of the learning goal (Weisberg et al., Citation2016). If teachers support learning through play, children not only learn better, but teachers are happier teaching (Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, et al., Citation2022).

The what of learning: The 6Cs

In Becoming Brilliant, Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek (Citation2016) offer views of what counts as success for students learning in our schools. Should our children merely learn what is on the test, or should they adopt a broader set of skills that prepare them for the 21st century? Working in tandem with the Brookings Institution’s Skills for a Changing World initiative and the Millions Learning global education project, we recognized that to be prepared for the future workplace, students would need to be able to excel and solve tomorrow’s problems using a set of core competencies: the 6Cs (Care et al., Citation2017; Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2020; Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, et al., Citation2022). The 6Cs are a set of interconnected skills that are scientifically sound and importantly, are malleable, in that active playful learning environments can accentuate progress in these skills. Interestingly, they are also the suite of interconnected skills most prized in the workplace, offering a cradle to career approach to education.

Collaboration is, at its base, forming relationships. Whether among children or between children and adults, collaboration is the key to learning. Indeed, Kuhl (Citation2007) suggests that we have a “socially gated brain” by showing that the most effective learning takes place when infants engage in interaction with other humans. Due to interactivity and contingency – uniquely inherent features of social communication – infants learn the most through these back-and-forth exchanges with their social surroundings (Kuhl, Citation2007). Recent research shows that when young children are engaged in conversations and interactions, they are building brain connectivity and structure (Romeo et al., Citation2018).

Strong collaboration begets strong Communication skills. Through communication, children learn to express themselves and exchange ideas using their developing language skills.

Content is born from good communication skills. Be it in literacy or math, language ability is key to mastering content.

Critical thinking, or the ability to use evidence to solve a problem, is evident early in children’s lives and is itself built upon content because … .

Creative innovation emerges from environments where children can explore, ask questions and that support curiosity.

Finally, Confidence emerges when children have the courage to try even in the face of failure (Duckworth, 2007) and to develop a growth mindset (Dweck, Citation2009).

Taken together, these six skills that emerge in playful learning or guided play prepare children to be the social, caring, thinkers and creators of the next generation.

Applications of APL in media and educational technology

In a comprehensive review of the literature on children’s media experiences (Hassinger-Das, Palti, et al., Citation2020; cf.; Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2015), we asked how the characteristics of active playful learning might be embedded into television and digital media to exploit the learning value of “educational programs.” While there are some notable exceptions like Sesame Street (Truglio & Seibert-Nast, this volume), Blue’s Clues (Anderson et al., Citation2000), and varied Noggin programming (Miklasz et al., Citation2023), television programs labeled “educational” are frequently divorced from the science of learning. This is also true for digital apps (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2015) where zero of the most downloaded apps (N = 129) contained all the science of learning pillars. According to a rating system developed by Meyer et al. (Citation2021), in order to receive a perfect score across all science of learning pillars (active, engaging, meaningful, socially interactive), apps were required to contain every characteristic. However, only 9% of all apps had a total score of at least 9 out of 12 (Meyer et al., Citation2021).

Our three-part equation combining community values with the characteristics of playful learning and the 6Cs points to ways in which we can narrow this gap in television and digital media to enable media to have a large, positive impact on children’s learning outcomes (Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, et al., Citation2022). Next, we summarize research studies of educational television and applications that include one or more of the characteristics of the APL model described above.

Television

Since the late 1960’s with television programs by Fred Rogers and Sesame Street, creators of children’s media built upon substantive educational theory, practice, and research to create television that helps children learn (Fisch & Truglio, Citation2001). Research highlights that the quality of television programming matters; high quality TV experiences that have playful learning characteristics embedded predict better learning outcomes (Anderson et al., Citation2001; Coates et al., Citation1976; Wright & Huston, Citation1983; Wright et al., Citation2001). A three-year longitudinal study found that watching high-quality educational television, like Sesame Street, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and Reading Rainbow, positively predicted children’s performance on literacy and math measures three years later, while watching entertainment TV, like cartoons, was negatively associated with those same measures (Wright et al., Citation2001). Another study found that the active and engaging nature of Dora the Explorer predicted children’s comprehension of the program content (Calvert et al., Citation2017).

Social interaction is key to learning. How can television and video, a commonly solitary activity, be designed in a way that still elicits what the research finds matters in terms of social interactive learning? One way is through parasocial relationships, when children feel a bond with on-screen characters and perceive themselves as meaningfully interacting with characters (Calvert, Citation2017). Parasocial relationships can be built when programs are designed with pauses to encourage mock social interactions as in Dora the Explorer or Blue’s Clues (Richert et al., Citation2011). Characters establish eye contact and “talk” to the audience, promoting children’s active engagement and “minds on” learning. Parasocial relationships can promote children’s math skills (Calvert et al., Citation2019; Howard Gola et al., Citation2013). A study by Calvert et al. (Citation2019) found that children’s parasocial relationships and math talk with a character predicted quicker, more accurate math responses during a virtual game.

Critical to making television and movies more meaningful for children are characters and storylines that reflect their identity and lived experiences. This relates to the second part of the equation for active playful learning. The portrayal of ethnicity and race in the media plays a significant role in shaping children’s perceptions of their own cultural backgrounds and those of different ethnic and racial groups. According to Common Sense Media, exposure to Black TV characters is associated with more positive self-esteem among Black elementary school girls (Rogers et al., Citation2021). Diverse representation has increased in children’s television and movies in the past decade. Programs like Molly of Denali, Rosie’s Rules, and Alma’s Way serve as examples of how genuine cultural representation can be integrated into children’s media. Key to the authenticity of the stories in the show is the inclusion of members from the portrayed communities as a part of the production teams (Díaz-Wionczek, Citation2023). Still, only 42% of preschool television characters are human and, of those human characters, only one-third are characters of color (Díaz-Wionczek, Citation2023).

For television to be truly meaningful for children, viewers need to be able to see connections between their lives and what they are watching. For example, in Sesame Street‘s real world segments, children are encouraged to make connections to their own lives. Sesame Street has prioritized representing the diverse cultural, linguistic, and ability contexts of their audience since its inception. Its influence has expanded to more than 150 countries across the globe, including refugee response regions. A recent review of animated films from 1937–2021 reveals the diversity of characters in Disney, Pixar, and DreamWorks movies have increased substantially over time, providing children with more opportunities to identify with characters on screen (Raju et al., Citation2023).

To ensure meaningfulness, they partner with local researchers and producers, and integrate families and children in the creation process. This gives the audience a voice in shaping production, and ensures content is both relevant and useful (Cole, Citation2008; Gettas, Citation1990; Kohn et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). Finally, children’s experience of joy and humor during watching promoted their engagement; five- to seven-year-old children who watched humorous educational segments showed higher attention while watching and retained more information (Zillmann et al., Citation1980). Thoughtfully designed television rises to the level of educational when it draws upon the science of learning by incorporating “how” children learn best – through socially interactive, meaningful, and joyful experiences.

Digital apps

Learning apps on digital devices are often (though not always) tied to television content, as is the case with Sesame Workshop’s digital offerings. Active playful learning characteristics have also been applied to mobile applications (Etta & Kirkorian, Citation2019; Hassinger-Das & Dore, Citation2022; Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2015; Meyer et al., Citation2021). A growing body of research demonstrates the positive potential of well-designed apps. For example, Dore et al. (Citation2019) found that when a vocabulary app game was designed with the active playful learning characteristics from the second part of the equation in mind, it effectively supported early vocabulary development in preschoolers. Similarly, Bower et al. (Citation2022) found that three-year-olds from under-resourced backgrounds could learn as much from an educational spatial app designed with the playful learning characteristics in mind as from a hands-on spatial puzzle. Kirkorian et al. (Citation2016) found that toddlers more effectively learned object labels from a tablet when the activity was designed to be contingent and active.

Not all apps are created with the playful learning characteristics in mind, however, and a recent study analyzed the top-downloaded “educational” apps according to four of the playful learning pillars (Active, Engaging, Meaningful, and Socially Interactive). The authors found that most of the apps scored in the lower range of all four pillars, with free apps being more distracting and less meaningful (Meyer et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, another study examined the characteristics and quality of creativity apps for children ages 4–12 available on the Google Play store (Booton et al., Citation2023). Although the researchers found these apps had activities that were appropriate for young children, the quality of creativity in the apps was low, in that they did not prompt children to use skills such as experimentation, divergent and convergent thinking, or meta-cognition. These findings represent a missed opportunity. In 2021, Pew Research Center found that about two-third of parents reported that their children (aged 11 or younger) used a smartphone. In another study by Courage et al. (Citation2021), almost 90% of the parents in the sample reported that their two- and three-year-olds had previously used a tablet device.

How can the industry take advantage of the opportunity to provide children with quality learning experiences through digital apps? Dore et al. (Citation2018) present guideposts for research-industry partnerships. The guideposts serve as a roadmap, guiding both developers and academics through the steps of identifying, hiring, and seamlessly working with the right collaborators on the other end. The paper also provides guidance for the field more generally, suggesting the establishment of a central platform where developers seeking researchers and vice versa can easily connect. It also proposes the introduction of recognition mechanisms, such as a “scientific seal of approval,” for apps that effectively integrate the science of learning into their products (see Dore et al., Citation2018, for more information).

Aligned with the first piece of the Active Playful Learning model – Community Voice and Cultural Values – including children and families in the design process from the very beginning can promote positive outcomes. The Cooney Center Sandbox, a design and innovation lab within Sesame Workshop, supports developers in designing with children. The Cooney Center collaborated with ScratchJr (a coding app for young children) and The GIANT Room (a STEAM learning organization), to include four- to six-year-olds in the design process. The interactive sessions were held over the course of three days in a public school classroom. Children engaged in playtesting and provided feedback to the facilitators. The insights gained from these sessions were compiled into a comprehensive report, and the developers translated these findings into actionable features to be prioritized in their product roadmap (Joan Ganz Cooney Center, Citation2023). The co-design initiatives at the Cooney Center exemplify how even very young children can play an active role in shaping the design of digital products.

While developers can collaborate with learning scientists and children to ensure the efficacy of their products, parents can also be supported to understand how to bring the characteristics of guided play or Active Playful Learning into digital app use with their children. Toh and Lim (Citation2021) found that parents can facilitate learning through play by engaging in enriching communication with their child while they play, through teaching their child game strategy, allowing the child to take the lead, and modeling game behavior. Stuckelman et al. (Citation2023) found that the duration that “parent nudges” were displayed (e.g., “Talk with your child about times they have felt angry,”) during parent-child digital app co-play predicted interaction quality. Identifying common behaviors and patterns of digital co-play can help developers understand how children can develop social and digital skills through parent-child joint media engagement. Parents can act as important partners in fostering children’s technology use in a way that aligns with skill development (the third part of the equation of “what” children need to learn). With that being said, parents often also rely on digital apps as a source of respite, treating apps as default caregivers during moments of need (Chen et al., Citation2020; Hartshorne et al., Citation2021). Therefore, developers bear the responsibility of crafting high-quality products that parents can trust and have confidence in for their child’s independent engagement as well.

What will it take to fully bring the science of learning to media?

Given the rapidly expanding landscapes for application, we briefly highlight opportunities and challenges in play research. Play is inherently cultural and occurs within the context of communities. Methods need to reflect the core values of the community by striving for cultural relevance and responsiveness. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is currently exploring how learning environments can facilitate instruction to promote students’ competencies (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2019). Student “co-agency,” where students make choices with adult guidance in pursuit of a learning goal, is at the center of their education reform efforts. To achieve both agency and cultural relevance, new methodologies are needed to keep community voice central to every stage of the research process, from design, to measurement, to analysis (Bermudez et al., Citation2023).

Despite evidence on the importance of community voice, marginalized communities are often excluded from the design and development stages in research and technology development, with alarming effects. Researchers and developers must do better to include and reflect people of color, individuals from low-resource backgrounds, and other marginalized groups. To create more equitable products and experiences, developers and researchers must rethink and make more democratic their standard scientific process. Assessments designed without input from relevant marginalized communities are common (Care et al., Citation2017). In play research, teachers, parents, and children should be active and agentic co-constructors. Meaningful teacher engagement can take the form of focus groups, curriculum co-design, and guides as well as projects using what has been called “authentic assessment” (Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, et al., Citation2022).

Digital media also fosters the need for new tools to test children’s learning in virtual settings. The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a series of innovations in online data collection (see Fisch, Hirsh-Pasek, et al, this issue for a discussion of methodological issues in remote data collection). Beyond standard assessments of comprehension and transfer, more research is needed to connect learning to distal outcomes like creativity, confidence, and the 6Cs. An investigation of outcomes such as creativity, and task persistence, using measurement tools designed for both in-person and virtual settings, offers a promising avenue for evaluating children’s learning from active playful learning pedagogy. Once these outcomes are achieved at scale, it will be time to expand focus beyond communities to city, country, and global levels.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic pressed children’s media researchers and practitioners to see how far technology could advance children’s learning. Perhaps because of the rush to market during lockdowns and remote and hybrid preschool formats, many of the products for young children did not bear the fruit of advancing learning in educationally sound ways (Dore et al., Citation2018; Hassinger-Das, Palti, et al., Citation2020; Meyer et al., Citation2021). Today, new frontiers are opening that will force us to ask anew how to create optimal and fun learning opportunities for young children. The next generation of children’s educational media is likely to include the metaverse and various AI initiatives. Researchers in the Science of Learning are leveraging the promise of the Active Playful Learning model as a mechanism for informing the educational media innovation (Jirout et al., Citation2023; Skene et al., Citation2022; Strasser et al., Citation2023).

Children’s media creation can benefit enormously from these new theories and discoveries. The three-part equation of cultural values + the how of playful learning + the what of playful learning, as well as the 6Cs, offers a way forward that is true to the science of learning and can be easily adapted in current and future iterations of digital educational programming. This special section of JOCAM demonstrates how this can be done by documenting the incorporation of the Active Playful Learning model into the production of Sesame Street.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katelyn Fletcher

Katelyn Fletcher is a former postdoctoral research fellow at Temple University’s Infant and Child Lab and consultant for the Brookings Institution Center for Universal Education. Her research interests focus on playful learning and the design, implementation, and evaluation of educational programs. Katelyn currently works in the field of education philanthropy.

Charlotte Anne Wright

Charlotte Anne Wright is a Learning Designer and Research Specialist at Begin Learning. She led the LEGO Foundation’s Playful Learning and Joyful Parenting project as a research fellow at Temple Infant and Child Lab.

Annelise Pesch

Annelise Pesch is a postdoctoral research fellow working at Temple University. Her research investigates social cognitive development in the preschool years including social learning, trust, play, and the impact of technology on learning and development. She leverages her research to inform the design of high-quality informal learning spaces through the Playful Learning Landscapes initiative.

Gavkhar Abdurokhmonova

Gavkhar Abdurokhmonova is a doctoral student in the Human Development and Quantitative Methodology program (concentration in Developmental Science, concentration in Neuroscience and Cognitive Science) at the University of Maryland, working with Dr. Rachel Romeo. Her research moves beyond documenting deleterious outcomes of socioeconomic disparities, and instead explores the neural mechanisms by which environments shape development, with the goal of highlighting the importance of individual differences in children’s language experiences.

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, a Professor of Psychology at Temple University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, was declared a “scientific entrepreneur” from the American Association of Psychology. Writing 17 books and 250+ publications, she is a leading professor in the science of learning who is known for translating research into actionable impact in schools (Activeplayfullearning.com), digital and screen media, and community spaces (Playfullearninglandscapes.com).

References

- Anderson, D. R., Bryant, J., Wilder, A., Santomero, A., Williams, M., & Crawley, A. M. (2000). Researching blue’s clues: Viewing behavior and impact. Media Psychology, 2(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0202_4

- Anderson, D. R., Huston, A. C., Schmitt, K. L., Linebarger, D. L., Wright, J. C., & Larson, R. (2001). Early childhood television viewing and adolescent behavior: The recontact study. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 66(1), i–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5834.00120

- Bassok, D., Latham, S., & Rorem, A. (2016). Is kindergarten the new first grade? American Educational Research Association Open, 2(1), 2332858415616358. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858415616358

- Bermudez, V. N., Salazar, J., Garcia, L., Ochoa, K. D., Pesch, A., Roldan, W., & Bustamante, A. S. (2023). Designing culturally situated playful environments for early STEM learning with a latine community. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2023.06.003

- Blinkoff, E., Fletcher, K., Wright, C., Espinoza, S., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2023). Tracking the winds of change on the American education policy landscape: The emergence of play-based learning legislation and its implications for the classroom. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/tracking-the-winds-of-change-on-the-american-education-policy-landscape-the-emergence-of-play-based-learning-legislation-and-its-implications-for-the-classroom/

- Booton, S. A., Kolancali, P., & Murphy, V. A. (2023). Touchscreen apps for child creativity: An evaluation of creativity apps designed for young children. Computers & Education, 201, 104811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104811

- Bower, C. A., Zimmermann, L., Verdine, B. N., Pritulsky, C., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2022). Enhancing spatial skills of preschoolers from under-resourced backgrounds: A comparison of digital app vs. concrete materials. Developmental Science, 25(1), e13148. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13148

- Calvert, S. L. (2017). Parasocial relationships with media characters: Imaginary companions for young children’s social and cognitive development. Cognitive Development in Digital Contexts, 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809481-5.00005-5

- Calvert, S. L., Putnam, M. M., Aguiar, N. R., Ryan, R. M., Wright, C. A., Liu, Y. H. A., & Barba, E. (2019). Young children’s mathematical learning from intelligent characters. Child Development, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13341

- Care, K., Kim, H., Anderson, K., & Gustafsson-Wright, E. (2017, March 28). Skills for a changing world: National perspectives and global movement. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/skills-for-a-changing-world-2/

- Chen, C., Chen, S., Wen, P., & Snow, C. E. (2020). Are screen devices soothing children or soothing parents?Investigating the relationships among children’s exposure to different types of screen media, parental efficacy and home literacy practices. Computers in Human Behavior, 112, 106462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106462

- Coates, B., Pusser, H. E., & Goodman, I. (1976). The influence of “Sesame Street” and “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” on children’s social behavior in the preschool. Child Development, 47(1), 138–144. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128292

- Cole, C. (2008, June). The world’s longest street: How Sesame Street is working to meet a diversity of children’s needs across the globe. Proceedings of the 7th international conference on Interaction design and children, Chicago, IL (pp. 1).

- Colliver, Y., Harrison, L. J., Brown, J. E., & Humburg, P. (2022). Free play predicts self-regulation years later: Longitudinal evidence from a large Australian sample of toddlers and preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 59, 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.11.011

- Courage, M. L., Frizzell, L. M., Walsh, C. S., & Smith, M. (2021). Toddlers using tablets: They engage, play, and learn. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 564479. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.564479

- Darling-Hammond, L., Schachner, A. C., Wojcikiewicz, S. K., & Flook, L. (2022). Educating teachers to enact the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 28(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2022.2130506

- Díaz-Wionczek, M. (2023). Representation of race in children’s media. In M. Giraud & A. Grant-Thomas (Eds.), Reflections on children’s digital learning (pp. 21–23). Embrace Race.

- Dore, R. A., Shirilla, M., Hopkins, E., Collins, M., Scott, M., Schatz, J., Lawson-Adams, J., Valladares, T., Foster, L., Puttre, H., Toub, T. S., Hadley, E., Golinkoff, R. M., Dickinson, D., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Education in the app store: Using a mobile game to support U.S. preschoolers’ vocabulary learning. Journal of Children and Media, 13(4), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2019.1650788

- Dore, R. A., Shirilla, M., Verdine, B. N., Zimmermann, L., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2018). Developer meets developmentalist: Improving industry–research partnerships in children’s educational technology. Journal of Children and Media, 12(2), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2018.1450086

- Dweck, C. S. (2009). Mindsets: Developing talent through a growth mindset. Olympic Coach, 21(1), 4–7.

- Etta, R. A., & Kirkorian, H. L. (2019). Children’s learning from interactive eBooks: Simple irrelevant features are not necessarily worse than relevant ones. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2733. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02733

- Fisch, S. M., & Truglio, R. T. (Eds.). (2001). “G” is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame street. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gettas, G. J. (1990). The globalization of Sesame Street: A producer’s perspective. Educational Technology Research and Development, 38(4), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02314645

- Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2016). Becoming brilliant: What science tells us about raising successful children. American Psychological Association.

- Hadani, H. S., & Vey, J. S. (2021, April 1). Infusing playful learning in cities: How to partner with communities for impact. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/infusing-playful-learning-in-cities-how-to-partner-with-communities-for-impact/

- Hartshorne, J. K., Huang, Y. T., Lucio Paredes, P. M., Oppenheimer, K., Robbins, P. T., & Velasco, M. D. (2021). Screen time as an index of family distress. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 2, 100023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100023

- Hassinger-Das, B., & Dore, R. A. (2022). “Sometimes people on YouTube are real, but sometimes not”: Children’s understanding of the reality status of YouTube. E-Learning and Digital Media, 20(6), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/20427530221140679

- Hassinger-Das, B., & Fletcher, K. (2023). The benefits of playful learning. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-benefits-of-playful-learning/

- Hassinger-Das, B., Palti, I., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2020). Urban thinkscape: Infusing public spaces with STEM conversation and interaction opportunities. Journal of Cognition and Development, 21(1), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2019.1673753

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R., Berk, L., & Singer, D. (2009). A mandate for playful learning in preschool: Presenting the evidence. Oxford University Press.

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Nesbitt, K., Lautenbach, C., Blinkoff, E., & Fifer, G. (2022). Making schools work: Bringing the science of learning to joyful classroom practice. Teachers College Press.

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., Hadani, H., Blinkoff, E., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2020, October, 28). A new path to education reform: Playful learning promotes 21st-century skills in schools and beyond. The Brookings Institution: Big Ideas Policy Report.

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., Zosh, J. M., Golinkoff, R. M., Gray, J. H., Robb, M. B., & Kaufman, J. (2015). Putting education in “educational” apps: Lessons from the science of learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100615569721

- Howard Gola, A. A., Richards, M. N., Lauricella, A. R., & Calvert, S. L. (2013). Building meaningful parasocial relationships between toddlers and media characters to teach early mathematical skills. Media Psychology, 16(4), 390–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.783774

- Jirout, J. J., Ruzek, E., Vitiello, V. E., Whittaker, J., & Pianta, R. C. (2023). The association between and development of school enjoyment and general knowledge. Child Development, 94(2), e119–e127. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13878

- Joan Ganz Cooney Center. (2023, June 8). Kindergarteners are co-designers: Improving ScratchJr. https://joanganzcooneycenter.org/2023/06/08/kindergarteners-are-co-designers-improvingscratchjr/-ng

- Kirkorian, H. L., Choi, K., & Pempek, T. A. (2016). Toddlers’ word learning from contingent and noncontingent video on touch screens. Child Development, 87(2), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12508

- Kohn, S., Foulds, K., Cole, C., Matthews, M., & Hussein, L. (2021). Using a participatory approach to create SEL programming: The case of Ahlan Simsim. Journal on Education in Emergencies, 7(2), 288–310. https://doi.org/10.33682/hxrv-2g8g

- Kohn, S., Foulds, K., Murphy, K. M., & Cole, C. F. (2020). Creating a Sesame street for the Syrian response region: How media can help address the social and emotional needs of children affected by conflict. YC Young Children, 75(1), 32–41.

- Kuhl, P. K. (2007). Is speech learning ‘gated’ by the social brain? Developmental Science, 10(1), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00572.x

- Meyer, M., Zosh, J. M., McLaren, C., Robb, M., McCaffery, H., Golinkoff, R. M., & Radesky, J. (2021). How educational are “educational” apps for young children? App store content analysis using the four pillars of learning framework. Journal of Children and Media, 15(4), 526–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2021.1882516

- Miklasz, K., Levine, M. H., Mays-Green, M., Wong Chin, C. B. V., & Zimmerman, K. (2023). Growing your Noggin: Implementing a learning impact evidence framework in a multimedia children’s platform. www.noggin.com/research/

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). OECD future of education skills 2030 concept note. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/student-agency/Student_Agency_for_2030_concept_note.pdf

- Pesch, A., Ochoa, K. D., Fletcher, K. K., Bermudez, V. N., Todaro, R. D., Salazar, J., Gibbs, H. M., Ahn, J., Bustamante, A. S., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2022). Reinventing the public square and early educational settings through culturally informed, community co-design: Playful learning landscapes. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 7322. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.933320

- Raju, S. A., Sanders, S. R., Bolton-Raju, K. S., Bowker-Howell, F. J., Hall, L. R., Newton, M., Neill, G. S., Holland, W. J., Howford, K. L., Bolton, E. V., Arora, P., Raju, A. S., Shah, P. J., Azmy, I. A. F., & Sanders, D. S. (2023). A cohort study of the diversity in animated films from 1937 to 2021: In a world less enchanted can we be more Encanto? Cureus, 15(8), e43548. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43548

- Richert, R. A., Robb, M. B., & Smith, E. I. (2011). Media as social partners: The social nature of young children’s learning from screen media. Child Development, 82(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01542.x

- Ring, E., & O’Sullivan, L. (2018). Dewey: A panacea for the ‘schoolification’ epidemic. Education, 46(4), 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2018.1445474

- Rogers, O., Mastro, D., Robb, M. B., & Peebles, A. (2021). The inclusion imperative: Why media representation matters for kids’ ethnic-racial development. Common Sense.

- Romeo, R. R., Segaran, J., Leonard, J. A., Robinson, S. T., West, M. R., Mackey, A. P., Yendiki, A., Rowe, M. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2018). Language exposure relates to structural neural connectivity in childhood. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38(36), 7870–7877. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0484-18.2018

- Simoncini, K., & Lasen, M. (2021). Pop-up loose parts playgrounds: Learning opportunities for early childhood preservice teachers. International Journal of Play, 10(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2021.1878775

- Skene, K., O’Farrelly, C. M., Byrne, E. M., Kirby, N., Stevens, E. C., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2022). Can guidance during play enhance children’s learning and development in educational contexts? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Child Development, 93(4), 1162–1180. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13730

- Strasser, K., Balladares, J., Grau, V., Marín, A., & Preiss, D. (2023). Efficacy and perception of feasibility of structured games for achieving curriculum learning goals in pre-kindergarten and kindergarten low-income classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65, 396–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2023.08.006

- Stuckelman, Z., Yaremych, H. E., & Troseth, G. L. (2023). A new way to co-play with digital media: Evaluating the role of instructional prompts on parent–child interaction quality. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 9(3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000363

- Toh, W., & Lim, F. V. (2021). Let’s play together: Ways of parent–child digital co-play for learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(7), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1951768

- Weisberg, D. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Kittredge, A. K., & Klahr, D. (2016). Guided play: Principles and practices. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416645512

- Wright, J. C., & Huston, A. C. (1983). A matter of form: Potentials of television for young viewers. American Psychologist, 38(7), 835. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.38.7.835

- Wright, J. C., Huston, A. C., Murphy, K. C., St Peters, M., Piñon, M., Scantlin, R., & Kotler, J. (2001). The relations of early television viewing to school readiness and vocabulary of children from low-income families: The early window project. Child Development, 72(5), 1347–1366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00352

- Zigler, E. F., & Bishop-Josef, S. J. (2004). Play under siege: A historical overview. Zero to Three, 30(1), 4–11.

- Zillmann, D., Williams, B. R., Bryant, J., Boynton, K. R., & Wolf, M. A. (1980). Acquisition of information from educational television programs as a function of differently paced humorous inserts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.72.2.170

- Zosh, J. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Hopkins, E. J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Solis, S. L., & Whitebread, D. (2018). Accessing the inaccessible: Redefining play as a spectrum. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01124