ABSTRACT

Through extensive research with early childhood educators, Sesame Workshop identified a critical educational need, as today’s preschoolers commonly lack curiosity, creativity, and perseverance in the face of challenges – an issue that impacts their ability to navigate obstacles at school and in life. To address this educational need, Sesame Street designed a playful problem-solving curriculum to help foster preschoolers’ curiosity, critical thinking skills, creativity, and perseverance which are foundational skills to instill a positive approach to learning. Following the Sesame Workshop Model, formative research played a critical role in Sesame Street story development, especially with a new curriculum focus that involved a unique story format designed to support preschoolers’ comprehension. We conducted formative research, in schools (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) and virtually (during the COVID-19 pandemic), wherein children aged 3–5 years old watched a rough draft version of an in-progress script (a “storymatic”) and researchers analyzed children’s comprehension. Findings guided script development to enhance the educational impact of each story.

Sesame Workshop is the global impact nonprofit behind Sesame Street, the landmark television program designed to provide the foundational skills to help prepare young children for school and for life. Sesame Workshop’s mission is to help children grow smarter, stronger, and kinder by delivering research-based, curriculum-directed content that addresses critical educational needs of young children. Smarter involves not only teaching academic skills (literacy, mathematics, and science), but includes the cognitive skills necessary for children to learn how to process and apply information effectively. Stronger addresses children’s physical health as well as their ability to manage their emotions and build resiliency. Kinder refers to all the social skills so imperative to the development of an emotionally healthy child: sharing, taking turns, empathy, compassion, friendships, celebrating physical and cultural differences and similarities, and having a positive self-identity.

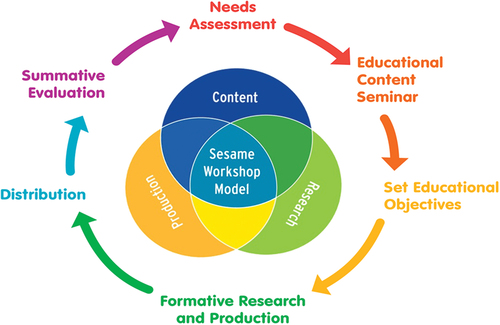

To ensure educational integrity, content is developed through the Sesame Workshop Model established by the Workshop’s co-founders, Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett (Fisch & Truglio, Citation2001). The model is comprised of three distinct disciplines (see Venn diagram in ), which are represented by experts in each area: Research (those who study how children learn); Education (those who develop and implement curriculum); and Creative (those who create the content including writers, producers, animators, and songwriters). This interdisciplinary team works collaboratively, and the content is driven by curriculum goals aligned with learning outcomes. The Sesame Street integrated whole-child curriculum is revised annually to ensure that the show continues to address the current educational and societal needs of today’s preschoolers and adheres to the best practices in early childhood education and learning science research. Once we identify a critical educational, societal, or health need affecting preschool children and their families, we devote approximately half of the overall Sesame Street season of shows (13–15 shows) for two seasons of production. The second season allows us to assess the previous season with advisors to further refine our content focus and address additional curriculum goals not covered.

Each Sesame Street production season begins with the annual curriculum seminar. Once the educational need is identified, leading academic researchers and educators are invited to advise on the best practices for the specific educational curriculum focus. While these advisors are integral to the production process, the real experts are the children who participate in formative research. Sesame Street was the first series to employ formative research and continues to use it on an ongoing basis to inform production decisions.

The educational need

“Playful Problem Solving: Positive Approaches to Learning” was Sesame Street’s curriculum focus for Seasons 51 & 52. Approaches to Learning, as defined by The Head Start Child Development and Early Learning Framework (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2010), refers to observable behaviors that indicate ways children become engaged in social interactions and learning experiences. The learning outcomes focus on children’s: a) initiative and curiosity (an interest in varied topics and activities, desire to learn, creativity, and independence in learning); b) persistence and attentiveness (the ability to begin and finish activities with persistence and focused attention); and c) cooperation (planning, initiating, and completing learning activities with peers).

Our exploration of these curriculum goals began in November of 2017 as we were planning for the Sesame Street 50th season. We began by holding an Advisory Roundtable Discussion inviting leading child experts across the disciplines of child and developmental psychology, early childhood education, pediatrics, clinical and applied psychology, educational public policy, school administration, and children’s media communication. The advisors were asked to focus on the issues facing preschoolers as it pertained to their school readiness and life success. They advised that we focus our attention on:

cultivating happiness, curiosity, wonder, and a love of learning, as these all seemed to be on the decline among preschoolers;

reducing the amount of pressure and stress preschoolers are facing, especially as kindergarten becomes the new First Grade with developmentally inappropriate assessments;

providing opportunities for imaginative play and for learning through play;

building resiliency skills and placing more emphasis on emotional well-being;

increasing children’s confidence as learners (i.e., positive attitudes towards self and learning; being empowered to learn through mistakes and take safe risks when faced with age-appropriate challenges);

enhancing listening skills, perspective-taking, empathy, and compassion.

In addition to listening to the academic experts, we also wanted to assess how their recommendations aligned with the daily observations of early childhood educators and parents. In follow-up virtual roundtable discussions with early childhood teachers who serve as Lead Teachers with at least 7 years of teaching experience, early childhood educators had similar concerns with their top recommendations focused on developing young children’s:

communication skills and their language ability to express their needs and emotions;

executive function skills (ability to follow directions, have focused attention and the ability to shift their attention, and perspective taking); and

ability to take initiative and to encourage independence and self-help skills.

For parents, a snowball sampling survey revealed that they were most concerned about how to help their child cope with difficult situations and bolster their self-confidence. Parents indicated that they place more equal attention on academic and thinking skills with social and emotional learning. They also wanted their children to have respect for themselves, followed by respecting people of different races, ethnicities, or religions and those with different physical or learning abilities.

Active playful learning

As we synthesized these findings, we were in the process of producing Sesame Street Season 49 with its curriculum focus on learning through play, specifically guided play. While there are educational benefits of all play, not all play patterns are created equal in terms of learning outcomes (Bodrova et al., Citation2013; Hirsh‐Pasek et al., Citation2009; see Fletcher et al., Citationthis issue). Guided play refers to learning experience that combines the child-directed nature of free play with a focus on learning outcomes and adult mentorship (Weisberg et al., Citation2016). Learning through play empowers children to become creative and engaged lifelong learners. That is because when children play, being motivated by their own interests makes play meaningful. They are also cognitively, physically, and socially engaged, and curious as they try out possibilities and revise their thinking as they explore challenges and take safe risks in their experimenting (The Lego Foundation, Citation2018).

With Season 50 we began our curriculum journey focused on positive approaches to learning through Active Playful Learning (guided play) with an emphasis on the following educational messages: mistakes are okay, persevere in the face of challenges, and take initiative and safe risks as a problem solver. Still being guided by the Active Playful Learning theoretical framework, we then developed the Playful Problem Solving: Positive Approaches to Learning curriculum for Sesame Street’s seasons (51 and 52). This curriculum narrowed our focus on the what ifs (Golinkoff & Hirsh‐Pasek, Citation2016) to inspire children’s curiosity (Wonder), critical thinking skills (Creativity), and perseverance (Let’s try).

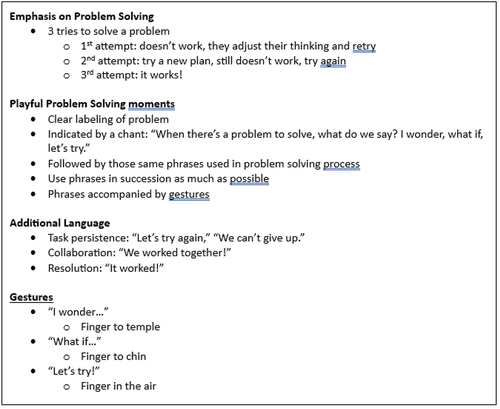

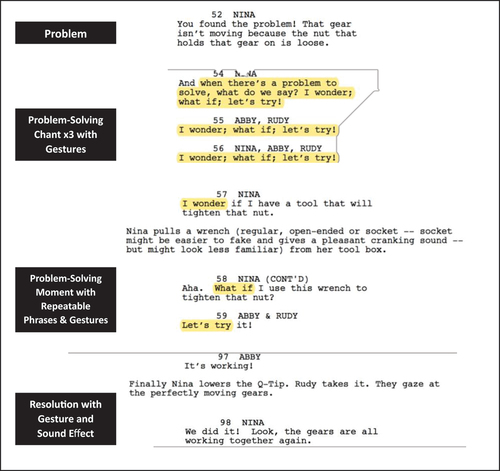

Based on our cumulative knowledge from previous formative research studies for how to best support children’s comprehension and learning, the Education Team recommended a consistent narrative structure in support of these curriculum goals () with the key words and phrases (“I wonder … What if … Let’s try!”) being repeated with a supporting gesture (Barnes et al., Citation2023; McNeil et al., Citation2000). This is the first time in the history of Sesame Street that writers followed a narrative structure in support of the overall curriculum approach. illustrates how this narrative structure was implemented in telling the story of Cinderella bringing her broken clock to Sesame Street for repair. Abby, a Fairy in Training 4-year-old Muppet character, uses her magic to shrink them down and go inside the clock to see what the problem is. They notice that one of the gears has a loose nut. Nina, a human cast member who owns the bike shop, has a wrench in her tool belt, but they can’t reach the nut. They repeat the phrases and for the second attempt they try moving the nut with a cotton swab that they found in the clock. Instead of giving up, for their third attempt, they try taping the wrench (the tool to tighten the nut) to the cotton swab (the stick that gives them the length to reach the nut) which is successful!

Sesame Workshop’s approach to formative research

The formative testing for Sesame Street seasons 51 and 52 focused on the 9-minute, live-action narrative segment set on Sesame Street (i.e., the Street Story) designed to teach the Positive Approaches to Learning curriculum goals. The testable version of the Street Story script is adapted into a “storymatic” that depicts the story in an illustrated digital storybook with voiceovers (). The storymatics allow us to test content before it goes into full live-action studio production. Immediately after viewing, the children are interviewed about what they recalled. Interview questions probe both appeal and comprehension, as preschoolers learn best from content that they feel connected to, and understanding children’s interests provides insights that support our learning goals (Gola et al., Citation2013). From formative research, we gather insights from children that we translate into actionable recommendations for writers and producers to make changes to the story to maximize appeal, engagement, and comprehension of learning goals.

Research aims

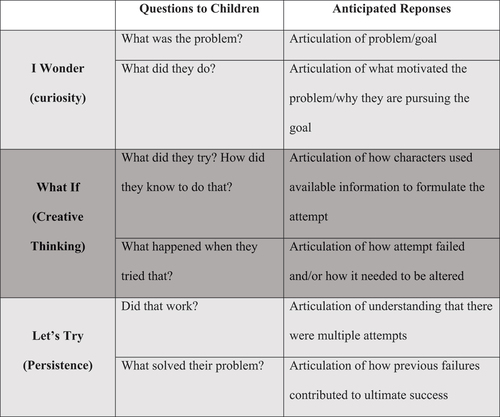

To assess what preschoolers understood about each of the three major components of the Positive Approaches to Learning curriculum, interviews were structured to identify the ways children recalled and described (1) how characters discover a problem; (2) how characters ideate potential solutions; and (3) how characters persevere when faced with challenges or failure. Our research questions focused on how best to teach these specific playful problem-solving skills through a televised story. At what point do problem-solving stories become too complex or confusing for children to follow? What types of problems are relevant or meaningful for children? How do children articulate the thinking process of characters in a story (i.e., idea formation, and what inspired new ideas) and the characters’ multiple attempts as problem solvers? How do visuals and demonstrations support children’s ability to talk about the thinking process? What keeps children engaged with a predictable story format? The ongoing, iterative formative process provided further insights about how to utilize the possibilities inherent to television to support children’s learning.

Method

Over a span of 8 months, scripts were tested throughout the writing process, with approximately 20 children participating in group or individual interviews for each round of testing. To balance production timelines and research needs, one to two storymatics were tested at a time with results provided to the production and education teams after each round. Interviews were structured to elicit responses that are representative of what children absorbed from the content (see ); we tested the content – not the children – and so we built in many scaffolded opportunities for children to provide their answers. Our interviews took a strengths-based approach in which we asked children questions in ways that would be most helpful to that child rather than expecting every child to answer questions that are worded in exactly the same way.

In-school formative process

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, ten Street Stories from Season 51 were tested in schools with a total of 132 children aged 3 to 5 years old. We visited Head Start and daycare centers in the New York metropolitan area and held small group interviews with approximately 24 children each day. In groups of six split by age, children watched one storymatic and immediately after viewing were interviewed about what happened in the story. The following day, the same children watched a different storymatic and were interviewed. During the viewing, researchers observed the children for engagement behaviors (e.g., laughing, pointing, making comments). The subsequent interview followed a semi-structured format in which the lead researcher would use a list of prepared questions and probes, rephrased as necessary depending on children’s needs, coupled with printed screenshots from the storymatic to facilitate a conversation about the content. Additional researchers observed these interviews and transcribed the children’s responses. Data from each group were analyzed as a whole.

Virtual formative process

Six scripts from Season 52 were tested across three rounds with a total of 47 children aged 3 to 4 years old. This testing began during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 and therefore required a shift to a fully virtual format. Twelve to twenty participants, recruited via qualitative research firms, completed one-on-one video interviews with a researcher. The researcher shared their screen with the child and played a storymatic, interviewed the child about the story, shared the second storymatic, and then interviewed the child again. Researchers developed protocols with the same interview structure as Season 51 but were able to more fluidly follow the individual child’s line of thinking and use screen sharing to show a variety of images to support the interview questions. Importantly, the child’s caregiver was now present for these individual interviews, prompting a new level of interactivity and co-viewing that created a more naturalistic viewing experience.

Analytic approach

Interview responses from children were transcribed verbatim, including descriptions of how they pointed to images or used gestures to support their responses, during the interview and from recordings. Responses were then analyzed via thematic analysis to reveal patterns that indicated where content supported or hindered children’s comprehension of the story and the Positive Approaches to Learning curriculum goals. The research questions and anticipated responses described in served as a guide and starting point from which data were analyzed and provided a framework through which success is assessed. We coded interview data for key words central to the curriculum like “problem” or “try” as well as the language children used to describe the problem, the three attempts to solve, and the thinking process (e.g., “they were solving” or “it was a bad idea”) to determine what children understood and where patterns of misunderstanding arose. Thematic analysis also allows for unanticipated themes to emerge and provides the opportunity for new insights into how children learn from media.

Results

Some consistent findings began to emerge across episodes. First, when the problem in the story was unclear, children struggled to articulate all of the other aspects of the problem-solving process. In one story, Elmo was getting frustrated about waiting in line, so his friends invented a game to help pass the time, adding a new rule to the game each time Elmo started to feel frustrated again. Children struggled to articulate that Elmo’s frustration was the source of the problem, and they therefore were unable to describe any “attempts” to solve it.

Second, strong visuals and formal features, or the audiovisual elements that act as cinematic cues in television such as camera movements, supported children’s ability to recall the three-attempt structure (Moeller, Citation1996). For example, in a story about using a pulley and rope to lift a brown paper bag to a second story window, two girl Muppet characters (aged 5 and 3 respectively) tried tying the bag directly to the rope, then putting the bag in a box tied to the rope, both of which slipped off. They finally scanned their environment and saw a basket, which was visually highlighted, and tied the rope to the basket’s handle to successfully lift the bag. The visual highlight and camera movements seemed to support children’s recall of the problem-solving process.

Third, children’s understanding of persistence was most apparent in their articulations that some attempts did not work and only one was successful. In the aforementioned story, when children were able to describe that the characters tried two things that did not work and finally found an idea that solved their problem, it can be inferred that children knew the characters did not give up.

Finding one: Clarify the problem

The tested stories followed three general patterns, which children displayed varying levels of ability to follow. One of these patterns included stories in which an uber-problem created sub-problems. For example, Elmo and some friends were tasked with building a play castle out of cardboard, and through the process of building (uber-problem) came across a series of sub-problems, like needing to add a dragon-sized door and make one tower taller than the other. The second pattern was stories in which characters took three attempts to solve a single problem, such as attempting to fix a broken clock and failing twice before ultimately succeeding. The third pattern was stories in which a single tool was used in several different ways to solve three separate problems (e.g., a baton used to retrieve a toy stuck high up in a tree, a toy stuck far under stairs, and a toy that rolled under a piece of furniture). Children were most able to follow and talk about those problems that were narrow in focus, rooted in familiar scenarios, and featured solutions that were predictable within the context of the story. Problems with simple, clear, visual solutions were the easiest for children to recall.

We found that children tended to be most confused with the uber and sub-problem structure and would often recall only the uber problem rather than smaller problems that arose at each attempt. To better support children’s understanding of the problem, we recommended writing about very explicit and visual problems, repeating the word “problem” frequently, and restating the entire problem before each repetition of the chant to further clarify how it was evolving. For example, in a story about racing ping pong balls down cardboard ramps, the visual of the race was very clear and the problem after each race, that one ping pong ball lost and one ping pong ball won, was very simple and explicit, and therefore easy for children to recall.

Finding two: Visuals support children’s understanding

Because preschool aged children are still developing their metacognitive abilities (Chatzipanteli et al., Citation2013), we expected children to have the most difficulty recalling and articulating the thinking process in each story; as anticipated, “what if” was the most challenging aspect of the chant and the problem-solving process for children. They would sometimes even recall the “I wonder, what if, let’s try!” chant as, “I wonder if we can try,” leaving out the “what if” entirely. Describing metacognition, particularly articulating how attempts to solve a problem fit into the process, was challenging for children to articulate across scripts, and this is consistent with literature on metacognition that indicates that these skills begin to emerge during the preschool years and continue to develop throughout childhood, adolescence, and even into young adulthood (Schneider, Citation2008). When asked how characters knew what to try next or how they came up with new ideas, children often did not know how to reply. We found that formal features, such as camera panning or visual highlights, helped children to recall what motivated new ideas (e.g., taping a wrench, which was too short, to a long stick, which wasn’t the right shaped tool, to tighten a nut that was out of reach). We found that reflection moments were particularly useful, especially when they could be supported by visuals, as these helped children to articulate what went wrong during an attempt and how the attempt needed to be changed to try again. After assessing Season 51, we found that adding visual effects like video replays or thought bubbles to represent characters’ thinking supported children’s recall of problem-solving attempts and/or finding new ideas.

Finding three: Differentiating attempts strengthens comprehension of perseverence

When the three problem-solving attempts were visually similar, children struggled to articulate that there were discrete differences in each attempt. In one story, characters were attempting to make a very loud musical instrument by putting rocks inside a tin can. To make the instrument even louder, they added even more rocks. Children struggled to see this as two separate attempts to make the instrument louder because they were so visually similar; this made it challenging to assess whether children understood that characters persisted and tried again. However, as in the pulley example described above, when each attempt was visually distinct but structurally similar, it was easier for children to describe how each attempt was different (e.g., bag tied to rope failed, box tied to rope failed, and basket tied to rope succeeded). This finding suggested that scaffolded attempts support children’s ability to recall the differences, as each attempt built on the previous attempt. By articulating that some ideas failed and the last one succeeded, children demonstrated an understanding that characters persisted and did not give up.

Conclusion

Results of each formative research study were presented to the production and education teams with actionable recommendations illustrating how the findings might be incorporated into script changes to enhance the Active Playful Learning outcomes. To ensure that these recommendations were implemented into scripts in ways that would elevate the educational impact, the education team worked closely with the creative team during script rewrites with the Head Writer. As these scripts were adjusted and other scripts were written, members of the education, Education, Research, and Production teams all provided notes to guide the educational messaging while keeping the story engaging and humorous to keep preschoolers’ attention. When filming began, a member of the Education team was on set to oversee the implementation of educational messaging, the supporting formal features (e.g., camera angles, close-ups, pans), and the characters’ use of gestures accompanying the “I wonder, what if, let’s try!” chant. In post-production reviews, producers ensured the use of formal features to support the educational goals and oversaw the editing process. Once fully produced, episodes from both Seasons 51 and 52 were utilized in a summative evaluation to assess impact (Fisch, Fletcher, et al., Citationthis issue). This active playful problem solving research continues to be iterated upon to inspire and inform future Sesame Workshop content focused on the Creativity and Playful Problem Solving Educational Impact Area in the United States and around the world (Foulds et al., this issue).

After more than 50 years of curricula, research, and production, the totality of this process, from the inception of an educational need to curriculum development through formative testing and into production, is the gold standard for each new season of Sesame Street. Continuing formative research allows the content to actively adapt to evolving practices in pedagogy and children’s changing needs and media preferences. This research is vital to ensuring that content remains relevant, adeptly navigates children’s developmental abilities, and helps children develop the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors they need to grow smarter, stronger, and kinder.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Sesame Street Education Team: Autumn Zitani, Jessica DiSalvo, Hei Min You; the Production Team: Ken Scarborough, Brown Johnson, Ben Lehman, Sal Perez, Kay Wilson-Stallings; and the Research Team: Jennifer Kotler Clark, Kim Foulds, Courtney Wong Chin, and Remi Torres for all their contributions at various stages of the production process, guided by the Sesame Workshop Model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rosemarie T. Truglio

Rosemarie T. Truglio, SVP of Curriculum and Content at Sesame Workshop, is responsible for curriculum and content development for Sesame Street and all new show productions, including Esme & Roy, Mecha Builders, Helpsters, Ghostwriter, and Bea’s Block. She is the author of Ready for School! A Parent’s Guide to Playful Learning for Children Ages 2 to 5 (2019). Dr. Truglio received a Ph.D. in Developmental and Child Psychology from the University of Kansas.

Becca Seibert Nast

Becca Seibert Nast (they/them) is the Senior Manager of Content Research at Sesame Workshop, focusing on formative research related to video content, digital games, and parent & educator resources. They have a master’s degree in Educational Theater from NYU, and they bring that perspective to their research with preschoolers for Sesame Street and Sesame Workshop content. Becca cherishes any opportunity to widely share children’s amazing points of view.

References

- Barnes, E. M., Hadley, E. B., Lawson-Adams, J., & Dickinson, D. K. (2023). Nonverbal supports for word learning: Prekindergarten teachers’ gesturing practices during shared book reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 64, 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2023.04.005

- Bodrova, E., Germeroth, C., & Leong, D. J. (2013). Play and self-regulation: Lessons from Vygotsky. American Journal of Play, 6(1), 111–123. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1016167.pdf

- Chatzipanteli, A., Grammatikopoulos, V., & Gregoriadis, A. (2013). Development and evaluation of metacognition in early childhood education. Early Child Development and Care, 184(8), 1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.861456

- Fisch, S. M., & Truglio, R. T. (2001). G is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and sesame street. Routledge.

- Fletcher, K., Pesch, A., Wright, C. A., Abdurokhmonova, G., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (this issue). Active playful learning as a robust, adaptable, culturally relevant pedagogy to foster children’s 21st Century skills. Journal of Children and Media, 18(3), 309–321.

- Gola, A. A. H., Richards, M. N., Lauricella, A. R., & Calvert, S. L. (2013). Building meaningful parasocial relationships between toddlers and media characters to teach early mathematical skills. Media Psychology, 16(4), 390–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.783774

- Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh‐Pasek, K. (2016). Becoming brilliant: What science tells us about raising successful children. American Psychological Association eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1037/14917-000

- Hirsh‐Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Singer, D. G. (2009). A mandate for playful learning in preschool: Applying the scientific evidence. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195382716.001.0001

- The Lego Foundation. (2018). What we mean by: Learning through play [Leaflet]. https://cms.learningthroughplay.com/media/vd5fiurk/what-we-mean-by-learning-through-play.pdf.

- McNeil, N. M., Alibali, M. W., & Evans, J. L. (2000). The role of gesture in children’s comprehension of spoken language: Now they need it, now they don’t. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 24(2), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006657929803

- Moeller, B. (1996). Learning from television: A research review. CCT Reports (No. 11). Center for Children & Technology.

- Schneider, W. (2008). The development of metacognitive knowledge in children and adolescents: Major trends and implications for education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 2(3), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228x.2008.00041.x

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). The head start child development and early learning framework. Office of Head Start.

- Weisberg, D. S., Hirsh‐Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Kittredge, A. K., & Klahr, D. (2016). Guided play. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416645512