Technologies of all types have become a fundamental part of our day-to-day lives. They may be invisible, remote, or directly controlled by us, and they are everywhere. Our basic body functions can be diagnosed, treated, and even replaced by new and advanced technologies. Our personal day-to-day activities and social relationships and connectivity are now also greatly impacted by technologies. Thus, the case can be made that it is time to expand the biopsychosocial approach or model to the biopsychosocialtech model.

The biopsychosocial approach is based on general systems theory and was first articulated by George L. Engel, M.D., at the University of Rochester Medical Centre in Rochester, NY [Citation1]. He stated that treating only body functions and structures is inadequate for understanding a person’s illness and that the most successful interventions are those that are based on the dynamic interaction of the biological, psychological (emotional/behavioural) and social (and environmental) factors impacting the individual, expanded upon in to include technological. The biopsychosocial approach continues to be fundamental today in guiding patient treatment and medical education at the University of Rochester Medical Centre [Citation2], as well as many other programmes around the world, and is the foundation for the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation3].

Table 1. Examples of Elements in each of the four biopsychosocialtech domains.

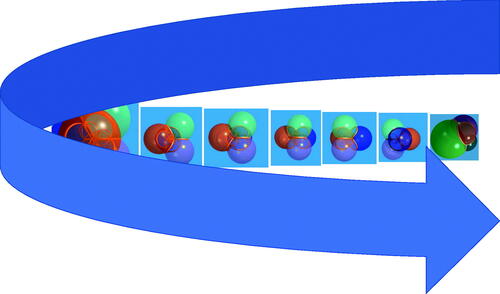

The four components of the biopsychosocialtech model are not only dynamically interrelated, but they influence and reconstitute one another over time and can affect many different levels of functioning, from cellular to organ system to person to family to society in an individually unique way. Technology alone can also reconstitute biological functions and systems, personal factors and social interactions and involvement. Thus, the choice to use, avoid, or reject a technology has implications for all the elements of the biopsychosocial model. is an admittedly imperfect depiction of four interrelated spheres (biological, psychological, social and technological) and how they change over time and reconstitute one another. The photos of the spheres were taken from screen shots from Dimensions Ep.4 – The fourth dimension II, a French project that makes educational movies about mathematics, focussing on spatial geometry [Citation4]. Each sphere or component is independent and comprised of elements that also evolve, reconfigure and change over time and are affected by the others in varying ways and degrees.

Figure 1. Components of the biopsychosocialtech model dynamically interacting and reconstituting one another over time. Source: Author.

In 2020, as the world contends with the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), we are witnessing the exploding role of technology in diagnosis and treatment. For example, advances in endoscopes and laboratory and diagnostic tools such as CRISPR for gene editing, as well as continued developments in medical and assistive technologies, have greatly impacted treatment options, decisions and outcomes. Thanks to advances in sensing and monitoring technologies, more people can stay in their homes and live independently. Nowadays a person can control door locks, room temperature, window blinds, and a variety of appliances with a smartphone or hands-free speaker controlled by voice, such as Amazon’s Echo. Robotic devices can do chores and provided some routine services to individuals thereby freeing caregivers for more sophisticated tasks. The easy availability of home delivery services in well populated areas adds another layer of support for the person in the home. Mobile health and telerehabilitation services can remotely monitor a person’s vital signs and allow for home-based health management for those in less densely populated areas. An example of this in AT was a process developed in Ireland where trained individuals went to people’s homes and conducted personalized assessments of needs, priorities, barriers and facilitators to create an individualized intervention plan. Professional consultation was achieved by transmission of assessment data and the plan to the appropriate professionals in Dublin. [Citation5]. Lessons learned in the field of assistive technology over time include some important fundamental concerns and considerations such as:

To best meet the needs of individuals, their health care providers must take the time to get to know them.

In the context of not feeling well, the person may feel overburdened by technology. There may not be the willingness, as well as readiness, to deal with the complexities of technologies and technology systems.

There needs to be a line of demarcation where technology is filling in where it can without interfering with the human touch and personal intervention. It is important to learn how much detached and remote care a person wants and how much remote monitoring is tolerable.

Individualized, customized, solutions will be more important, not less so. With so many options now, solutions can be tailor-made to fit individual needs and preferences and they need to be equitabley available.

The desired outcomes are having the person optimize use as well as maximize benefit.

Using AT to its full potential will require more training and support people and services to be available.

Patient engagement and involvement cannot just be buzz words. The goal is to achieve an individualized, customized solution that takes into account the individual’s unique medical and physical needs, personal characteristics and priorities, and the available social and environmental support and resources they have, as well as the characteristics of the technologies available.

The four interrelated constructs (biological, psychological, social and technological) and how they change over time and reconstitute one another need to be considered as a unit. This journal provides a chronological view of assistive technology (AT) developments over its 15 years of publication. While focussed on AT, we are learning how relevant these products can be for everyone. The biopsychosocialtech approach to matching person and technology can assure individual needs, rights, and personal aspirations are met as we go forward.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marcia J. Scherer

Marcia J. Scherer, Ph.D., MPH is Editor-in-Chief of Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology and Co-Editor of the book series for CRC Press, Rehabilitation Science in Practice Series. She has authored a trilogy of books describing the impact of various categories of assistive technology devices and services on people's health and life quality. She is a rehabilitation psychologist and founding President of the Institute for Matching Person & Technology. Dr. Scherer is also Professor of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Rochester Medical Center where she was privileged to benefit from the teaching of Dr. George Engel, founder of the biopsychosocial model, while she was a graduate student.

References

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136.

- Frankel RM, Quill TE, McDaniel SH, editors. The biopsychosocial approach: past, present future. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2003.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Dimensions Ep.4 – the fourth dimension II. [retrieved 2020 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ImA7EU3aY0&feature=share

- Craddock G, McCormack L. Delivering an AT service: a client-focused, social and participatory service delivery model in assistive technology in Ireland. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(1–3):160–170.