Abstract

Purpose

Telehealth provides psychotherapeutic interventions and psychoeducation for remote populations with limited access to in-person behavioural health and/or rehabilitation treatment. The United States Department of Défense and the Veterans Health Administration use telehealth to deliver primary care, medication management, and services including physical, occupational, and speech-language therapies for service members, veterans, and eligible dependents. While creative arts therapies are included in telehealth programming, the existing evidence base focuses on art therapy and dance/movement therapy, with a paucity of information on music therapy.

Methods

Discussion of didactic and applied music experiences, clinical, ethical, and technological considerations, and research pertaining to music therapy telehealth addresses this gap through presentation of three case examples. These programmes highlight music therapy telehealth with military-connected populations on a continuum of clinical and community engagement: 1) collaboration between Berklee College of Music in Boston, MA and the Acoke Rural Development Initiative in Lira, Uganda; 2) the Semper Sound Cyber Health programme in San Diego, CA; and 3) the integration of music therapy telehealth into Creative Forces®, an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Results

These examples illustrate that participants were found to positively respond to music therapy and community music engagement through telehealth, and reported decrease in pain, anxiety, and depression; they endorsed that telehealth was not a deterrent to continued music engagement, requested continued music therapy telehealth sessions, and recommended it to their peers.

Conclusions

Knowledge gaps and evolving models of creative arts therapies telehealth for military-connected populations are elucidated, with emphasis on clinical and ethical considerations.

Music therapy intervention can be successfully adapted to accommodate remote facilitation.

Music therapy telehealth has yielded positive participant responses including decrease in pain, anxiety, and depression.

Telehealth facilitation is not a deterrent to continued music engagement.

Distance delivery of music through digital platforms can support participants on a clinic to community continuum.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Background

History of telehealth

Telehealth is broadly defined as the delivery of healthcare services, where distance is a critical barrier prohibiting access to care. According to the World Health Organisation [Citation1] telehealth uses information and communication technologies to advance the wellbeing of individuals and communities through the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries. Research evaluation and continuing education of patients and healthcare providers can also be delivered through telehealth. Telemedicine and telerehabilitation are forms of telehealth that enable remote consultation, clinical, and communication services. These practices have been used by the United States (U.S.) Government since the 1960s. Over the past decade, the use of telehealth has been a research focus of the Public Health Department, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Department of Défense (DoD), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) [Citation1] According to the Health Resources and Services Administration, the aims of telemedicine include: (1) exchanging medical information between sites via electronic communications, and (2) using electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support and promote long-distance clinical health care. The range of internet-based technologies currently used includes videoconferencing, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications [Citation2].

The use of telehealth in the military

The United Nations proposed that internet accessibility should be considered a human right and issued guidelines for how to preserve human rights on the Internet [Citation3]. Telehealth is being promoted by the U.S. DoD and VA. In the DoD, legislation such as the Servicemembers’ Telemedicine & eHealth Portability Act of 2011 supports integration of telehealth for treatment of active duty service members [Citation4]. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the component of the VA that provides patient care, is investing heavily in telehealth to bring a wide array of services to veterans such as scheduling appointments, medication management, and a variety of treatment options. This is aligned with the Creating Opportunities Now for Necessary and Effective Care Technologies for Health Act of 2019, which advocates for these considerations throughout multiple sections: Sec 4: “Expanding the use of telehealth for mental health services” [Citation5, p. 7–8]; Sec 6: “Improving the processes for adding telehealth services” [Citation5, p. 8–9]; Sec 9: “Waiver of telehealth restrictions during national emergencies” [Citation5, p. 14]; Sec 12: “Studying and reporting on increasing access to telehealth services in the home” [Citation5, p. 16–17]; and Sec 14: “Modelling to allow additional health professionals to furnish telehealth services” [Citation5, p. 17–18].

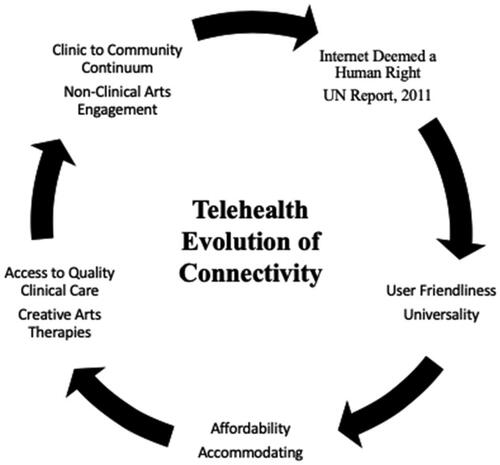

Telehealth facilitates a direct connection from medical centres to veterans at outlying clinics, in their homes and in their communities. In the VHA, telehealth is used to provide care through digital platforms such as My HealtheVet and GetWell Network [Citation6]. Furthermore, the VA established programmes specifically designed to deliver telehealth within in the VHA. For example, the Rural Veterans Tele-Rehabilitation Initiative (RVTRI), is an enterprise-wide initiative, funded by the Veterans Administration Office of Rural Health [Citation7]. The RVTRI was founded in 2009 and added a telehealth creative art therapies component in 2014 to serve veterans in remote areas or those who have diminished access to local services. As military and veteran populations continue to require comprehensive support, it is necessary to consider the specific needs within this demographic and provide access to quality care on a user-friendly, virtual spectrum supported through the evolution of telehealth technology, as shown in .

Trends in healthcare are moving towards the increased use of telehealth to deliver services to patients who live in remote locations, have mobility limitations due to disease or injury, and/or lack reliable transportation [Citation8]. Delivering creative arts therapies (art therapy, dance/movement therapy, music therapy) through telehealth can increase access, however, particular challenges such as video/audio latency and other connectivity issues regarding transmission and translation of quality images and sound need to be considered [Citation9,Citation10]. Furthermore, limited literature exists regarding practice recommendations for creative arts therapies delivery via telehealth [Citation11]. This paper provides clinical, ethical, and technological considerations and competencies for telehealth delivery of creative arts therapies and non-clinical/community arts engagement. These provide insight regarding technique adaptation, intervention strategy, and use of innovative technologies to best meet the needs of remote patients.

Introduction

Growing need for innovative care

Due to recent military conflicts, the prevalence of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), known as the ‘signature wounds of war’ have exponentially increased and resulted in devastating impacts on military personnel and their families [Citation12]. This often requires extensive rehabilitation at VHA and military treatment facilities and clinics, and within the community [Citation13]. Rates of TBI from Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation New Dawn vary in frequency from 11–20%. From 2001–2016, there were 361,793 reported cases of TBI in active duty service members [Citation14]. In addition, service members are five times more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD after sustaining a TBI. The lifetime incidence of PTSD among contemporary veterans is estimated to be 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women [Citation15]. Symptoms of PTSD and TBI often present as cognitive, emotional, social, occupational, and behavioural health issues [Citation16,Citation17]. Mental health issues have long been stigmatised in military culture. Because of this, active duty service members and veterans may not report or under report acute distress and long-term symptoms sustained during service [Citation18]. Historically, the image of the warrior across cultures has represented strength, power, and indestructibility. The effort to maintain this façade in occupational, familial, and social environments may further inhibit disclosure and thus erect barriers to seeking treatment [Citation19]. In addition to the impact of experiences and injuries sustained while serving in the military, as service members transition from active duty to veteran status, a variety of stressors (occupational, familial, social) may trigger frustration, depression, and isolation [Citation20]. Innovative treatments such as creative arts therapies are integrated in the clinical realm to aid in the rehabilitation of military personnel. These are delivered across a clinic to community continuum to assist transitions and changes such as occupation, service status, and other life situations [Citation19]. Telehealth is a platform that can be used to implement clinical creative arts therapies and promote community reintegration.

Forging partnerships: answering a nation-wide call

An initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network is a partnership with the U.S. Departments of Défense and Veterans Affairs and the state and local arts agencies with administrative support provided by Americans for the Arts [Citation21]. Creative Forces programming places creative arts therapists at the core of treatment teams at military and VA facilities across the U.S. and includes a telehealth component [Citation22]. A pillar of this initiative is a continuum of care between the clinic and the community that provides ongoing support for military-connected populations. While there is precedent for telehealth delivery of creative arts therapies across a continuum of care, programmatic implementation with service members and veterans is a relatively recent phenomenon. The RVTRI is aligned with the Veterans Administration’s ‘FY 2013–2015 Enterprise Roadmap,’ which details how veterans who live in remote areas are eligible to receive the same clinical services electronically as those who receive in-person treatment [Citation23]. In fact, the RVTRI anticipated the roadmap, inventing a centre-to-home clinical video telerehabilitation intervention starting with physical, occupational, and recreational therapy in 2009, subsequently adding speech-language therapy, employment services, and creative arts therapies by 2014. This served as a model for integrative and interdisciplinary telerehabilitation treatment programmes, which continue to grow across the DoD and VHA healthcare systems. For example, in 2020, expansion of creative arts therapies telehealth programming at one new DoD site in Anchorage, Alaska and three new VHA sites including Cleveland, Ohio, Indianapolis, Indiana, and Jackson, Mississippi is planned [Citation24]. Programmatic expansion demonstrates that creative arts therapists can effectively adapt and replicate practices to be facilitated via telehealth across disciplines [Citation9]. In addition to clinical and community programming, the RVTRI and Creative Forces partnership supports creative arts therapies telehealth research.

Evolving integration of music therapy, telehealth, and military populations

Defining music therapy in telehealth

Music therapy is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualised goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy programme [Citation25] completed a clinical internship and earned board-certification as a music therapist (MT-BC). Similar to other healthcare disciplines, music therapy is commonly incorporated into clinical milieus and exists in various treatment settings serving medical, neurological, mental health, educational, developmentally delayed, and palliative populations. Music techniques are used to address motor function, social skills, emotional regulation, coordination, self-expression and personal growth across the lifespan, from neonates to seniors. Music therapy has been offered in the VHA for decades and recently has been integrated into interdisciplinary care models within the DoD [Citation26]. Traditionally, evidence-based music therapy has been positioned in military healthcare as a clinical treatment that is conducted on-site (i.e., military installation or treatment facility) by a MT-BC [Citation27]. However, telehealth can extend the therapist’s reach to include patients who may be unable to attend in-person sessions, and to provide treatment beyond traditional ‘brick and mortar’ medical centres [Citation28]. When implemented with the intention of integration, telehealth can prevent isolation by promoting resiliency in recovery processes and transformative adaptation through community engagement.

Proof of concept: music therapy telehealth

Facilitation of music therapy telehealth to the home and/or community carries the potential to simplify and improve access compared to travelling to a medical facility for treatment. This convenience aims to enhance adherence, increase community integration, and improve quality of life. In 2010, Lightstone et al. conducted a 10-month intervention, which provided an in-person intake session followed by 24 music therapy telehealth sessions to a veteran diagnosed with PTSD [Citation29]. Due to prior positive experiences in music therapy and the lack of a local music therapist, the veteran appealed to the Canadian VA to provide music therapy services via telehealth at the VA facility nearest to him. He reported having a transformative experience in music therapy telehealth, which helped him engage with other mental health services, provided coping mechanisms, and increased his emotional regulation skills. According to the report, the clinical impact of music therapy treatment remained intact despite being delivered by internet-enabled live video streaming. The desire for greater access to music therapy clinical services using telehealth technology has been expressed with other populations [Citation30]. The treatment model used by Kong and Karahalios provided music therapy telehealth services to children with autism and their families living in rural areas. They found that parents were most frustrated by missing appointments, reduced access to music therapy services (i.e., lack of local MT-BCs), and distance to the clinic where their children were receiving care. Music therapy telehealth reduced frustrations by increasing access to care and treatment compliance; this concept may be generalised to other populations such as service members, veterans, and their families.

This paper provides case examples that illustrate the use and impact of music therapy telehealth and discusses future considerations for this practice on a clinical continuum. We identify music therapy interventions, musical exchanges, and adaptations or modifications necessary for telehealth facilitation. This informs future considerations for telehealth across creative arts therapies and non-clinical/community arts engagement.

Case examples

Music therapy telehealth models for military populations

This section includes three distinct models of music therapy telehealth and provides recommendations for sustainable practices, which support both clinical and community-based participation for military-connected populations. These examples address population-specific considerations, goal areas across functional domains, and circumstantial transitions, such as: (1) residing in remote locations with limited access to rehabilitative services or arts engagement opportunities; (2) transferring from programmes that offer music therapy to those that do not; (3) transitioning from active duty to veteran status, and music therapy is not offered at a local VA; (4) termination of services and remote relocation without access to a music therapist; (5) music therapist relocation.

Example 1: Berklee College of Music, Boston, MA, USA and Acoke rural development initiative, Lira, Uganda

Professors and students from the Music Therapy Department at Berklee College of Music piloted this initiative in 2013 as part of a year-long research practicum to facilitate community music through telehealth. Music was shared across cultures aimed to catalyse change in both communities – from a classroom in Boston to a school in Lira attended by liberated child soldiers of the Lord’s Resistance Army. “In Uganda, where music making is a natural part of life, music therapy can be adapted to address the critical needs of both the individual and the collective, bringing about wholeness in time. With ex-child soldiers, music provides voice where previously there’s only been silence” [Citation31, p. 3]. This pilot programme, MUSIC Heals, is an inspired collaboration between Berklee professors and representatives from Musicians for World Harmony [Citation32] following an impactful trip to the Acoke Rural Development Initiatives (ARDI), in Lira. Following the visit, both parties acknowledged the importance of maintaining connections to provide opportunities for sustained social engagement through music. It is notable that there are 1.3 million people per psychiatrist in Uganda, a staggering ratio that warrants assistance from outside entities (video 1, supplemental materials). To address this need, Berklee professors and music therapy students introduced a global initiative embedded in a clinical practicum course using community music and music therapy-informed concepts in student-lead telehealth sessions supervised by MT-BCs.

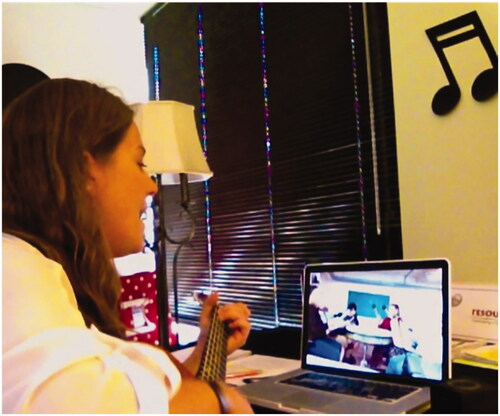

Music therapy telehealth in this example describes interactive music experiences through remote communication. These electronic exchanges provided need-based and culturally informed interventions between Berklee students and the former child soldiers. All music was played live and in real time, included rehearsed and improvised songs, and included interactive call-and-response exchanges with participants in both locations taking turns leading a variety of experiences, as shown in . Interactive music experiences included singing and dancing, drumming, lyric adaptations/songwriting, and music-based relaxation. Sessions occurred once weekly for 60-min and participants from each continent contributed to session planning. Ongoing consultation has been sustained through telecommunications between Berklee and ARDI for consistency of collaboration and continued psychoeducation. The appropriate technology was provided to ARDI by Berklee such as a laptop equipped to connect to live video streaming applications (e.g., Skype or Google Hangout), a hi-definition camera, and a microphone. Berklee used the same technology along with the addition of a projector and screen.

Example 2: semper sound cyber health programme: examples of individual and group therapy

Individual music therapy telehealth

In 2013, a VA Medical Centre in Southern California contracted telehealth services with a local music therapy agency for a male veteran diagnosed with severe TBI. He was discharged from a residential neurologic rehabilitation programme that included music therapy to a facility without it; shortly thereafter, the music therapist relocated out-of-state and was unable to continue in-person treatment. To provide consistency of care during treatment transitions, a contract was created for music therapy telehealth services. Contract deliverables included clinical sessions, documentation, and session materials, such as songs written and recorded in the remote sessions. Music therapy telehealth sessions occurred 1 to 2 times a week for 45–60 min and included a variety of interventions such as music-based relaxation, intentional inventorying of preferred music, lyric analysis/song discussion, songwriting, active music making, singing, and remote recording and production. Self-reported measures of pain perception, anxiety, and depression levels were administered using a Likert scale. Pre-and post- session responses revealed a decrease (per monthly average) across symptoms (refer to ) [Citation33]. In addition to individual sessions, the music therapist facilitated family engagement with the patient’s mother and daughter. The patient also remotely participated in special projects, presentations, and performances that supported a clinic to community treatment trajectory. For example, he participated in a music therapy telehealth presentation at a conference in New England from his home in Southern California.

Table 1. Percent decrease in pre- and post-session self-reported measures of pain, anxiety and depression during 2016 for a veteran receiving telehealth music therapy.

Group music therapy telehealth

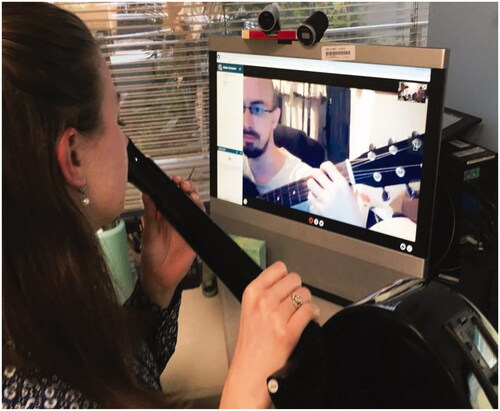

The Semper Sound Cyber Health programme also conducted group music therapy telehealth sessions for morale-building with female veterans at a residential facility in the Greater Boston area. This initiative was a collaboration between the Semper Sound Military Music Therapy programme in San Diego, CA [Citation34] and the William Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Social Consequences at the University of Massachusetts, Boston [Citation35]. Group music therapy telehealth sessions were provided as follow-up from an in-person 8-week music therapy group series. At the end of 8 weeks, the lead music therapist moved out of the area; however, the participants requested continuation of care. The lead music therapist coordinated with a local music therapy professor and a female veteran studying music to provide five additional sessions in which the lead music therapist facilitated remotely, and the professor and veteran provided in-person facilitation support, as shown in . Session topics included active music making, singing, active/intentional listening, lyric analysis, creative writing/songwriting, and creative arts to music. Participant evaluation of the 5-week group music therapy telehealth series indicated that music facilitation through a digital platform was not a deterrent from engagement, and the transmission of music through a digital platform was effective. Furthermore, participants expressed interest in additional telehealth music therapy groups.

Example 3: creative forces creative arts therapies telehealth initiative

Initial exploration of music engagement through telehealth

In 2015, a Creative Forces music therapist used digital interfacing to provide transition support for a service member who received in-person music therapy and faced a lapse of clinical services during the transition from active duty to veteran status, which compounded existing stressors. Factors such as living far from the closest VA and inability to independently transport himself due to a TBI-related seizure disorder posed ongoing difficulties for the veteran to receive in-person treatment. He was receiving telemedicine services (e.g., speech-language, primary care, medication management) through his local VA, however, they did not offer music therapy. Creative Forces supported weekly music engagement telehealth sessions ranging in length from 45–90 min. Adaptive music was facilitated to support creative expression, cognitive function, familial engagement, and participation in community arts. In addition, these sessions provided a supportive platform for the patient to discuss life events related to his ongoing military transition. Through consistent exposure to creative processes, he integrated music with his family, participated in community arts, and established a successful leatherworking business. He later reported on the contribution of telehealth music engagement to his ongoing well-being:

It not only affected me in a positive light, it impacted my entire family. Since my retirement from the Marine Corps, I remain in touch with my music therapist through telehealth and I continue to integrate music into my daily life. Playing [music] helps to reduce my seizures. When I feel one coming on, I pick up my ukulele and play, and it helps [Citation36].

Creative forces music therapy telehealth initiative: pilot programme

Learning from the initial phase of music engagement through telehealth and recognising the need for further development, Creative Forces connected with similar initiatives operating in the U.S. Through a partnership between Creative Forces, the University of Florida, and the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SG VHS), these entities worked together to build reliable, clinically-sound, replicable, and patient-centred creative arts therapies telehealth programming. At the Gainesville campus of the NF/SG VHS, creative arts therapies have been delivered to veterans via in-home telehealth through the RVTRI since 2014. Initially, the RVTRI supported solely art therapy and dance/movement therapies to veterans living in remote areas of North Florida and South Georgia. Understanding the value that music therapy could bring, in 2017, Creative Forces funded a music therapist to join the existing RVTRI telerehabilitation creative arts therapies staff (refer to ).

Common referral sources for music therapy telehealth include the TBI and PTSD treatment teams, neurology, psychiatry and primary care providers, women’s health services, and the wheelchair clinic. The music therapist educates providers about the clinical benefits of music therapy and considerations of telehealth treatment by providing in-services and attending team meetings, which assists in generating informed referrals. Veterans referred to the RVTRI for music therapy are seen initially for an in-person intake at the VA before starting telehealth. During this initial assessment session, the music therapist briefs the patient on the expectations and potential benefits of music therapy and considerations of telehealth treatment. Some of the benefits include decrease of stress and anxiety related to their diagnoses and being relieved of external stressors, which include driving long distances to receive services at a VA clinic, parking, and navigating facility grounds. The music therapist tracks patient progress and music therapy telehealth goals through documentation in the patient’s medical record. Furthermore, the music therapist attends team meetings to discuss patient progress in telehealth treatment. The addition of music therapy has aided in the growth of creative arts therapies services provided by the RVTRI, increasing the number of veterans receiving services within the creative arts therapies programme. For example, a search of the Veteran’s Health Information System and Technology Architecture electronic medical records indicated that in fiscal year 2019, the Creative Forces music therapist served 155 unique Veterans and provided 580 encounters of combined in-person and telehealth sessions. This has led to a more well-rounded treatment approach for veterans receiving clinical services through the VA.

Clinical and ethical considerations for creative arts therapies telehealth

The collaboration between Creative Forces and the RVTRI yielded programme models intended to inform telehealth-enabled services facilitated broadly across the creative arts therapies. This aims to achieve: 1) delivery of creative arts therapies via telehealth, 2) troubleshooting applied technology and clinical facilitation, 3) developing best practices for training and implementation, and 4) resourcing that champions the replication of telehealth creative arts therapies within the Creative Forces network. Telehealth manualisation targeted at maximum patient benefit across the DoD and VHA will ultimately be available to the public. The use of innovative technology platforms to deliver clinical services, such as the VA Video Connect and Adobe Connect, requires the transfer of knowledge and therapeutic skills for tele-therapists and patients. This may raise inquiry regarding technological competence required for creative arts therapies telehealth. According to Bates, “using technology to facilitate sessions adds a layer of complexity and requires addition competence. Therapists who use technology in practice must be competent in all aspects of the medium, including computer and Internet technology, data security, and client record confidentiality” [Citation37, p. 138]. To address this concern and support creative arts therapists in broadening their scope of telehealth practice, considerations for clinicians and exclusion criteria for participants have been established (See ) [Citation38].

Table 2. Factors for Implementing Creative Arts Therapies Telehealth.

In addition to the contents of (privacy, operational, audio, video, lighting), patient-centered guidelines for providers using telehealth should include ethical and safety standards, emergency protocols, and clinical documentation. The Art Therapy Credentials Board [Citation39] Code of Ethics addresses ethical considerations for telehealth use:

2.9.2 When art therapists are providing technology-assisted distance art therapy services, the art therapist shall make a reasonable effort to determine that clients are intellectually, emotionally, and physically capable of using the application and that the application is appropriate for the needs of clients. 2.9.3 Art therapists must ensure that the use of technology in the therapeutic relationship does not violate the laws of any federal, provincial, state, local, or international entity and observe all relevant statutes [Citation40].

The Code of Ethics and Standards of the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA) and the Dance/Movement Therapy Certification Board (DMTCB) explicitly states that the clauses “pertain to both face-to-face and distance forms of dance/movement therapy practice” [Citation41, p. 2]. Remote facilitation of dance/movement therapy is also exclusively referenced: 2.2. “Dance/movement therapists are aware of the unique confidentiality risks of online distance supervisory or consultation arrangements. They abide by practices to protect health information and client confidentiality in accordance with legal requirements” [Citation41, p. 10].

Technology is minimally addressed in the American Music Therapy Association Code of Ethics and telehealth regulations are not explicitly stated [Citation42]. However, music therapists providing teleservices should consider the entire code with attention to the following principles, which lends support to telehealth facilitation with adherence to patient safety:

1.7 Protect the rights of clients, students and research participants under applicable policies, laws and regulations. Music therapists will abide by privacy laws and exceptions as currently defined in Pub.L. 104–191 - Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and Pub. L. 93–380 - Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, and Title IX- Education Amendments Act. 2.1 Act with the best interest of clients in mind at all times. 3.1 Fulfill legal and professional obligations to the profession with respect to any applicable local, state, and federal laws and regulations, and employer policies. 3.12 Exercise caution and professional judgment in all electronic, written, verbal, and inferred communications being especially aware of electronic messages and potential public access. 4.2 Use resources available to them to enhance and better their practice. 5.3 Use caution, critical thinking, and strong consideration of the best available evidence when incorporating new and evolving interventions and technologies into their practice, education, or supervision.

In addition to the principles indicated above, music therapists engaging in telehealth can use the ethical decision making models in Appendix II of the American Music Therapy Association Code of Ethics to help inform decisions regarding telehealth practice.

Due to the physical distance between patient and provider, it is essential that assessment occurs throughout the telehealth session. It is critical that patients feel at least as safe in telehealth encounters as they do in conventional in-person treatment. Patient safety can be maintained by confirming patients’ physical addresses and emergency contact information at the beginning of each session as well as identifying potential safety hazards visible in the camera frame. Patient involvement in this process supports the identification and resolution of safety and privacy concerns by providing the opportunity for patients to take accountability in their care, which encourages ownership and responsibility for treatment successes.

Discussion

This review supports the delivery of music therapy through telehealth, in line with wider health and education practices [Citation1] and enables continuous delivery in cases of discharge from inpatient settings, relocation, etc. Music therapy telehealth also enables greater user engagement regardless of geographical location [Citation33]. The implementation of rehabilitation treatment via telehealth, to include music therapy, answers a need to deliver services to patients who live in remote locations, have mobility limitations, and/or lack reliable transportation [Citation8]. Creative Forces’ exploration of telehealth on a continuum of creative arts therapies and community engagement is building competencies and identifying challenges that inform the delivery of creative arts therapies telehealth across their network and that of partnering institutions. Publication of these initial findings will assist tele-creative arts therapists in solving audiovisual latency and other connectivity challenges [Citation43]. This paper contributes to the evolving evidence base on this subject by describing three telehealth programmes that have positively impacted patient care and community need. This demonstrates that these practices can be replicated across populations including civilian and military [Citation29,Citation30].

Veterans and active-duty service members with TBI, PTSD, and other chronic mental health conditions can experience exacerbated symptoms due to continuous life stressors, such as frequently changing duty station (relocation), adapting to new work and life environments, or transitioning from active duty military to veteran status. Complex diagnoses, physical limitations, avoidance, and stigma associated with mental health treatment often cause significant barriers to care, and may contribute to increased frustration, depression, and isolation [Citation20]. When implemented in clinical settings, creative arts therapies address symptoms associated with TBI and PTSD, and promote creative processes that break down the warrior culture myth and assist with disclosure [Citation19]. Through the work being done, it is becoming increasingly evident that creative arts therapies telehealth can yield similarly beneficial effects to in-person services by meeting patients in familiar environments such as their homes and communities. This ameliorates the need for travel to a medical centre and provides a degree of autonomy and control of the delivery, environment, and participation level in treatment [Citation37]. This autonomy can promote adherence to treatment plans, enabling patients to integrate telehealth sessions into their daily routines and having the independence to seek treatment in their chosen environments. Shared experiences that enhance creative expression, support emotion, and promote communication through enjoyable experiences can serve as a protective factor from isolation, which is commonly experienced during treatment transitions and can have grave consequences if not addressed.

The use of telehealth is potentially beneficial for the patients directly served as well as the providers and the institutions in which they work. For example, lack of physical space can be a factor that may discourage hiring creative arts therapists, as many clinics have limited rooms and/or lack the financial capacity to accommodate spatial modifications. Telehealth allows providers to be mobile, using multiple spaces within the facilities to conduct treatment and/or work from home, depending on the patients’ needs [Citation28].

Telehealth technology extends the reach of the therapist to accompany the patient into the home and community. Although telehealth may lack the immediacy that occurs during in-person treatment, it is likely to have advantages such a reinforcing adherence and practice in the patients’ actual living environments. A certain form of trust is engendered when patients invite the therapist into their homes, which can be beneficial to the treatment process. Music therapists and other creative arts therapists are encouraged to embrace emerging telehealth technologies and incorporate them to meet their practices to the benefit of their patients [Citation9].

Suggestions for future practice

Research supporting the use of creative arts therapies across military and veteran populations continues to develop, which may increase the demand for creative arts therapies telehealth programming, potentially enhancing the need for creative arts therapists who can operate telehealth platforms. Measures of pain perception, anxiety, engagement level, and community reintegration should continue to be evaluated to inform the direction of future telehealth applications, which could include physiologic monitoring, incorporation of virtual reality, and wider implementation of telehealth facilitation. It is also important to conduct formalised hypothesis-driven studies that measure the effects on the individual, the family, communities, and society-at-large.

For many military families, routine relocation affects their access to care, including creative arts therapies. Due to the limited number of creative arts therapists working in the DoD and VA, there is an increased demand for telehealth to conveniently and safely connect therapists with patients. The Creative Forces mission, to provide creative arts therapies to military personnel, does not end at the physical location of the clinic. It integrates into communities, where service members, veterans and their families continue to heal, return to active duty, or prepare to transition out of the military. This is aligned with the DoD and VHA’s commitment to provide innovative services, such as creative arts therapies, that address emotional, physical and mental needs of service members, veterans and their families, through the Whole Health Initiative [Citation44].

Limitations

Several limitations within creative arts therapies telehealth deserve mention. First, telehealth is dependent on therapist and user access to appropriate digital devices and bandwidth, as well as sufficient privacy, free from interruption and intrusion. Telehealth is vulnerable to failure if there is insufficient signal to transmit or receive the video connection. Audio overload may cause latency which may challenge sound exchange and disrupt facilitation of creative arts interventions; however, studies have found that the benefits of telehealth outweigh technical issues [Citation45]. While acknowledging reported benefits, it is important to understand the limitations of delivering telehealth across disciplines including issues of patient safety, privacy, confidentiality, intervention limitations, and technological failure. For example, if the power source is inadequate due to a poorly charged battery or electrical outage, the session cannot proceed. However, some of these inconveniences can spur creative solutions, which present opportunities for problem solving, planning, and developing patience and flexibility.

Coding and billing for telehealth is evolving, with different coverage across states and variance in reimbursement depending on facility policies/parameters. Despite progress in this area, creative arts therapists are not recognised as licenced independent practitioners in the DoD or VA, therefore they may encounter difficulty billing for telehealth services. To advance reimbursement, the efficacy and impact of creative arts therapies telehealth needs to be further researched. Currently there is limited research about telehealth overall, and more articles, such as this one, are needed to grow the evidence-base and advance the practice of telehealth.

Conclusion

This article presented programme examples, outcomes, and feedback from individual and groups of service members and veterans who engaged in telehealth music therapy. In the case examples illustrating music therapy telehealth, the patients conveyed positive responses to clinical services, endorsed that telehealth was not a deterrent to continued engagement in music therapy, reported their desire for continued music therapy via telehealth, and would recommend it to others. Facilitation of music therapy telehealth is warranted to support continued exploration of clinical practice, implementation, areas for growth, programme evaluation, and research.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

Additional disclaimer: The identification of specific products, scientific instrumentation, or organisations is considered an integral part of the scientific endeavour and does not constitute endorsement or implied endorsement on the part of the author, DoD, or any component agency.

Supplemental Material

Download QuickTime Video (217.7 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognise the service members and veterans engaged in rehabilitation, to include telehealth creative arts therapies, at various military installations and VA clinics across the United States, as well as the leadership, providers, and staff who assist in their recovery. Gratitude is extended to all the men and women who serve their country in the United States Armed Forces. Many thanks to MSgt Michael Schneider, USMC (Ret.) and Sgt Benjamin Tourtelot, USMC (Ret.), for sharing their experiences with music therapy telehealth. Special acknowledgement is extended to Demi Bullock, Barb Else, Donna Faraone, Lori Frazer, Lori Gooding, Steve Kosta, Keith Meyers, Rachelle Morgan, Heather Spooner, and Karen Wacks for their efforts integrating creative arts therapies and telehealth. The authors of this paper would like to acknowledge the contributions of Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network and the VA Office of Rural Health.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no declaration of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Défense, the Veterans Health Administration, or U.S. Government. The identification of specific products, scientific instrumentation, organisations, individuals or compositions is considered an integral part of the research endeavour and does not constitute endorsement or implied endorsement on the part of the author, DoD, or any component agency.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. Report on the second global survey of ehealth; 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf.

- Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. Health Resources and Services Administration. Telehealth Programs; 2015. Available from: https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/telehealth/index.html.

- Human Rights Council. The promotion, protection, and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet; 2016. Available from: https://www.article19.org/data/files/Internet_Statement_Adopted.pdf.

- STEP Act Servicemembers' Telemedicine and E-Health Portability Act of 201. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/1832/text.

- Creating Opportunities Now for Necessary and Effective Care Technologies (CONNECT) for Health Act of 2019. S. 2741, 116d Cong., 1st Sess; 2019. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/s2741/BILLS-116s2741is.pdf.

- The GetWell Network and My Health eVet; 2018. Available from: https://www.getwellnetwork.com/solutions/government/.

- The U.S Department of Veteran’s Affairs. The rural veterans tele-rehabilitation initiative team wins the VHA systems redesign champion award; 2011 2012 Apr 25. Available from: https://www.northflorida.va.gov/NORTHFLORIDA/features/RVTRITeam.asp.

- Levy CE, Silverman E, Jia H, et al. Effects of home video telerehabilitation to deliver physical therapy on functional and health-related quality of life outcomes. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(3):361–370.

- Spooner H, Lee J, Langston D, et al. Using distance technology to deliver the creative arts therapies to veterans: case studies in art, dance/movement and music therapy. Arts Psychother. 2019;62:12–18.

- Turgoose D, Ashwick R, Murphy D. Systematic review of lessons learned from delivering tele-therapy to veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(9):575–585.

- Van Ast P, Larson A. Supporting rural careers through tele-health. Rural Remote Health. 2007;7:623.

- Center for Military Health Policy Research (RAND). Invisible wounds of war. Summary and recommendations for addressing psychological and cognitive injuries; 2008. Available from: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a480992.pdf.

- Tanielian, T., Jaycox, L. H. (Eds.). Invisible wounds of war: psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2008.

- Defense Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC). “DoD Worldwide Numbers for TBI.” Available from: https://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi.

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(2):220–226.

- Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Barnes DE, et al. Association of traumatic brain injury with chronic pain in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans: effect of comorbid mental health conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(8):1636–1645.

- Stecker T, Fortney J, Owen R, et al. Co-occurring medical, psychiatric, and alcohol-related disorders among veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(6):503–507.

- Sartorius N. Stigma and mental health. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):810–811.

- Vaudreuil R, Bronson H, Bradt J. Bridging the clinic to community: music performance as social transformation for military service members. Front Psychol. 2019;10:119.

- Kim PY, Thomas JL, Wilk JE, et al. Stigma, barriers to care, and use of mental health services among active duty and National Guard soldiers after combat. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(6):582–588.

- National Endowments for the Arts. Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network; 2019. Available from: https://www.arts.gov/partnerships/creative-forces.

- Bronson H, Vaudreuil R, Bradt J. Music therapy treatment of active duty military: an overview of intensive outpatient and longitudinal care programs. Music Ther Perspect. 2018;36(2):195–206.

- VA Office of Information and Technology. History of IT at the VA [Data file]; 2017. Available from: https://www.oit.va.gov/about/history.cfm.

- National Endowment for the Arts. National Endowment for the Arts announces expansion of Creative Forces Healing Arts Network: three veteran-serving telehealth sites to join the network; 2019. Available from: https://www.arts.gov/news/2019/national-endowment-arts-announces-expansion-creative-forces-healing-arts-network.

- American Music Therapy Association. “What is music therapy?”; 2019. Available from: https://www.musictherapy.org.

- Vaudreuil R, Avila L, Bradt J, et al. Music therapy applied to complex blast injury in interdisciplinary care: a case report. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(19):2333–2342.

- American Music Therapy Association. Music therapy and military populations: a status report and recommendations on music therapy treatment, programs, research, and practice policy; 2014. Available from: www.musictherapy.org/assets/1/7/MusicTherapyMilitaryPops_2014.pdf.

- Kvedar J, Coye J, Everett W. Connected health: a review of technologies and strategies to improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth. Health Aff (Millwood)). 2014;33(2):194–199.

- Lightstone AJ, Bailey SK, Voros P. Collaborative music therapy via remote technology to reduce a veteran’s symptoms of severe, chronic PTSD. Arts Health. 2015;7(2):123–136.

- Kong H-K, Karahalios K. Parental perceptions, experiences, and desires of music therapy. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2016;2016:1870–1879.

- Codding P, Wacks K. Music therapy with Uganda’s ex-child soldier survivors. International Association for Music & Medicine Newsletter, 2015, 1–3.

- Musicians for World Harmony, MUSIC Heals program; 2015. Available from http://www.musiciansforworldharmony.org/musicians-for-world-harmony-abroad-music-therapy-charity.

- Langston DG, Vaudreuil R. 2018. Telemedicine and music therapy (Poster presentation). Proceedings from the 5th International Conference of the Association for Music and Medicine. Barcelona, Spain: International Association for Music and Medicine.

- Resounding Joy, Inc. Semper Sound Military Music Therapy Program; 2018. Available from: http://resoundingjoyinc.org/semper-sound/.

- William Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Social Consequences; 2018. Available from: https://www.umb.edu/joinerinstitute.

- Schneider M. Creative Forces®: NEA MILITARY HEALING ARTS NETWORK. [web log comment]; 2017. Available from: https://www.arts.gov/national-initiatives/creative-forces-nea-military-healing-arts-network/resources/verterans-voices-michael-schneider.

- Bates D. Music therapy ethics “2.0”: preventing user error in technology. Music Ther Perspect. 2009;32(2):136–141.

- National Endowment for the Arts. Telehealth manual for the creative arts therapies: Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network telehealth design, plan, and services support. Washington (DC): Author, 2018.

- American Art Therapy Association. Ethical principles for art therapists; 2013. Available from: https://arttherapy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Ethical-Principles-for-Art-Therapists.pdf.

- Art Therapy Credentials Board. Code of ethics, conduct, and disciplinary procedures; 2013. Available from: https://www.atcb.org/Ethics/ATCBCode.

- American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA). Code of ethics and standards; 2015. Available from: https://adta.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Code-of-the-ADTA-DMTCB-Final.pdf.

- American Music Therapy Association. Code of ethics; 2019. Available from: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/ethics/.

- Levy C, Spooner H, Lee J, et al. Telehealth-based creative arts therapy: transforming mental health and rehabilitation care for rural veterans. Arts Psychother. 2018;57:20–26.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole health initiative; 2019. Available from: https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/.

- Baker F, Krout R. Songwriting via Skype: an online music therapy intervention to enhance social skills in an adolescent diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome. Br J Music Ther. 2009;23(2):3–14.