Abstract

Purpose

Orientation and Mobility (O&M) professionals teach people with low vision or blindness to use specialist assistive technologies to support confident travel, but many O&M clients now prefer a smartphone. This study aimed to investigate what technology O&M professionals in Australia and Malaysia have, use, like, and want to support their client work, to inform the development of O&M technologies and build capacity in the international O&M profession.

Materials and Methods

A technology survey was completed by professionals (n = 36) attending O&M workshops in Malaysia. A revised survey was completed online by O&M specialists (n = 31) primarily in Australia. Qualitative data about technology use came from conferences, workshops and interviews with O&M professionals. Descriptive statistics were analysed together with free-text data.

Results

Limited awareness of apps used by clients, unaffordability of devices, and inadequate technology training discouraged many O&M professionals from employing existing technologies in client programmes or for broader professional purposes. Professionals needed to learn smartphone accessibility features and travel-related apps, and ways to use technology during O&M client programmes, initial professional training, ongoing professional development and research.

Conclusions

Smartphones are now integral to travel with low vision or blindness and early-adopter O&M clients are the travel tech-experts. O&M professionals need better initial training and then regular upskilling in mainstream O&M technologies to expand clients’ travel choices. COVID-19 has created an imperative for technology laggards to upskill for O&M tele-practice. O&M technology could support comprehensive O&M specialist training and practice in Malaysia, to better serve O&M clients with complex needs.

Most orientation and mobility (O&M) clients are travelling with a smartphone, so O&M specialists need to be abreast of mainstream technologies, accessibility features and apps used by clients for orientation, mobility, visual efficiency and social engagement.

O&M specialists who are technology laggards need human-guided support to develop confidence in using travel technologies, and O&M clients are the experts. COVID-19 has created an imperative to learn skills for O&M tele-practice.

Affordability is a significant barrier to O&M professionals and clients accessing specialist travel technologies in Malaysia, and to O&M professionals upgrading technology in Australia.

Comprehensive training for O&M specialists is needed in Malaysia to meet the travel needs of clients with low vision or blindness who also have physical, cognitive, sensory or mental health complications.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

People with low vision or blindness can be immobilised by their lack of timely access to information when travelling in the community. To address this problem, long cane techniques were developed in the USA in the 1940s, and the Orientation and Mobility (O&M) profession was thus established [Citation1]. Iterations of the laser cane evolved from the 1960s and subsequently, many other specialist electronic travel aids have been developed [Citation2,Citation3], taught to clients by an O&M specialist to extend their range of preview and provide essential information about the travel environment.

O&M specialists vary in their technology skills. A show of hands at the Australasian O&M conference in Melbourne (n = 90; April 2018) indicated that a third were “early adopters” who loved using technology in client programmes, a third were confident technology users, and a third were “laggards” who resisted new technology until forced to embrace it [Citation4]. This professional reluctance can limit opportunities for O&M clients and thereby contribute to socially-imposed disability that the O&M profession is trying to address [Citation5].

Blindness is a low incidence condition and so specialist electronic travel aids for O&M can seem somewhat exotic. There are sensor devices that extend the traveller’s range of preview such as the Miniguide or Ultracane [Citation3] or provide navigational support such as the Victor Reader Trek [Citation6] and accessible maps with audio/haptic options, braille and tactile graphics [Citation7,Citation8]. Low vision aids range from simple handheld electronic magnifiers useful for reading signage and price tags, to bionic eye technologies that are surgically implanted and stimulate spots of light in response to environmental features [Citation9,Citation10]. Virtual reality systems simulate O&M experiences in a play-space before tackling real-world travel challenges [Citation11–14].

An O&M client with complex needs – additional physical, cognitive, social or mental health problems – might use a combination of specialist aids. However, most O&M clients can now access mainstream devices with accessibility features to support their travel. They use computers, tablets, smartphones, apps and personal activity monitors without needing an O&M specialist to mediate the process.

There are approximately 250 O&M specialists and guide dog mobility instructors in Australia and New Zealand, mostly itinerant, serving urban, rural and remote clients [Citation15]. Dynamic video-link technologies like WhatsApp, FaceTime and the ROAM system are already used by some professionals to bridge huge distances and trouble-shoot travel challenges with clients in between visits [Citation16,Citation17].

At the same time, O&M specialists are working with multidisciplinary research teams on travel technologies for public installation. These include “nearables” like Neatebox systems at road crossings and Bluetooth beacons installed in universities, sports venues, airports, and railway stations. These beacons activate a smartphone app when the traveller is in proximity, providing pre-recorded landmarks and local information for orientation [Citation18–22].

While this O&M technology development is exciting, the uptake of specialist O&M technologies can be poor [Citation23]. Thus, the Swinburne O&M research team surveyed O&M clients and O&M professionals. The purpose of this end-user study was to investigate what technology O&M professionals in Australia and Malaysia have, use, like, and want to support their client work, to inform development of useful O&M technologies, optimise uptake, and build capacity in the international O&M profession.

Materials and methods

This mixed-methods research with a qualitative priority used a two-phase survey design and a series of qualitative inquiries. A technology survey of O&M professionals was administered face-to-face in Malaysia and then revised before being administered online in Australia. Additionally, O&M technologies were discussed at several professional forums in Malaysia and Australia. Informed consent was given verbally during face-to-face interviews, workshops and forums, and implied when participants completed paper or online surveys. The research was approved by the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee (2016/316).

Survey development

Survey questions drafted by our research team in collaboration with Australian O&M specialists were translated into Bahasa Malaysia and back to English using Google Translate, and then checked by a Malaysian-speaking team member (SS). After the Malaysian pilot, the questions were expanded then administered online (see Supplement).

Recruitment and data collection

In early 2018, an Australian O&M specialist (LD) spent a month in Kuala Lumpur and Kuching, Malaysia to investigate the cultural relevance of two new O&M functional assessment tools [Citation24]. During this field trip, the O&M specialist delivered two O&M professional development workshops where technology surveys were completed.

A three day workshop at the Malaysian Association for the Blind (MAB) in Kuala Lumpur was organised by the National Council for the Blind Malaysia (NCBM), attended by staff and volunteers (n = 19) from six not-for-profit blindness/low vision agencies, and three university academics teaching O&M within their education and occupational therapy qualifications. A one-day O&M workshop (organised by BTL) at Swinburne’s Sarawak Campus, was attended by vision professionals (n = 57) from Sarawak, Sabah and Peninsular Malaysia. The O&M specialist also met with staff at a school for the blind and a society for the blind to better understand O&M services in Malaysia; visited two universities to understand O&M professional training pathways; and conducted nine O&M client assessments together with local O&M professionals.

Survey questions were refined at the sixth Australasian O&M Conference in Melbourne, April 2018 (LD). In August 2018, an invitation to participate in the Qualtrics survey was emailed to Australian O&M agencies and members of the O&M Association of Australasia. The survey was open for one month. Finally, the use of technology in guide dog travel [Citation25] was a topic of interest at the International Guide Dog Federation seminar in September 2018 (attended by LD).

Data analysis

Malaysian survey data were entered manually into Excel, and Australian survey data were exported to Excel from Qualtrics. Descriptive statistics were generated using IBM SPSS Version 25 (JB) then analysed in conjunction with free-text survey responses, field notes from Malaysian workshops, client assessments and observation sessions, and conference notes (LD). Interpretations of data were checked through conversations with O&M colleagues in Australia and members of Swinburne’s O&M client reference group.

Results

This study identified personal technology that O&M professionals have, use and like. There were few new ideas for O&M technologies, but the need for comprehensive O&M specialist training in Malaysia, and technology training in Australia and Malaysia was evident, to build O&M workforce capacity to meet clients’ needs.

Demographic profile of survey respondents

Demographic details of the Malaysian and Australian cohorts are shown in .

Table 1. Gender, age, vision and qualifications of Malaysian and Australian cohorts.

Australian O&M specialists are comprehensively trained and formally qualified, whereas the four fully qualified O&M specialists working in Malaysia a decade ago have since retired without replacement. O&M services in Malaysia are provided by people who have undertaken non-formal or partial O&M training (workshops, short courses or part of another qualification) and built their skills through workplace experience. Malaysian participants engaged with O&M services from the following fields:

social services – CBR fieldworkers (6), skill development instructors (2), welfare officer (1), agency manager (1), and agency volunteer (1)

education – teachers/lecturers (4), deafblind programme coordinator (1), early childhood assistant (1), others unspecified

health professions – optometrists (8), occupational therapists (3), ophthalmologist (1), doctor (1)

The Australian online cohort (n = 31) also included two O&M professionals from New Zealand, two from Singapore, three guide dog mobility instructors and one O&M assistant.

Similar numbers of O&M professionals in Australia and Malaysia worked with children and with adults (), but greater caseload diversity was evident in the Australian cohort.

Table 2. O&M professionals' experience with different clients.

What technologies do O&M professionals have, use and like?

National differences in caseload diversity and resourcing were evident in the range of devices and travel aids that participants used.

Malaysian participants were strong on long cane skills, and hungry for professional development about complex clients with multiple disabilities and consequently, aids that could support this work. In Malaysia, only 28% of participants used a laptop; 22% a desktop computer, 22% a tablet; 61% used a mobile phone, of which only 6% had an iPhone; 36% used accessibility features on a smartphone, 50% used zoom/large print, 42% used voiceover, and 11% used reverse contrast with any of their devices. Glasses, magnifiers and canes were common in Malaysia, but specialist assistive technologies were rare – in the past year only 17% of participants had used a portable braille note-taker, 14% a CCTV, 6% standalone GPS (e.g. Trekker Breeze), and 3% a braille embosser and 3D printer.

The caseload diversity Australian O&M professionals was evident in their work with long canes (97%), support canes (71%), identification/symbol canes (71%), guide dogs (68%), walking frames (65%), manual wheelchairs (29%), powerchairs (48%), motorised mobility scooters (39%), handheld sonar (42%), standalone GPS (23%), CCTV (16%), barcode readers (7%), and personal activity monitors (29%).

In Australia, only 45% of O&M professionals used a landline phone, whereas universal smartphone use was assumed, with 74% specifying Apple, and 19% specifying Android. Some had an iPhone provided at work, some because their clients used an iPhone, and some just liked the simplicity, accessibility features and synchronisation of iOS devices, finding them stable, easy to operate, and easy to teach to clients.

Confidence with a smartphone’s accessibility features varied: 77% could use a screen reader, 64% could use screen magnification, 67% could make changes to text formatting, and 29% could adjust for hearing; 87% could use accessibility features with their vision, 32% had practised without vision and 29% with low vision; but 23% did not work with smartphone accessibility features at all.

Most of the Australian cohort used a laptop or desktop computer (84%); many used a tablet (58%) provided at work; yet only 52% felt they had current devices that met their needs.

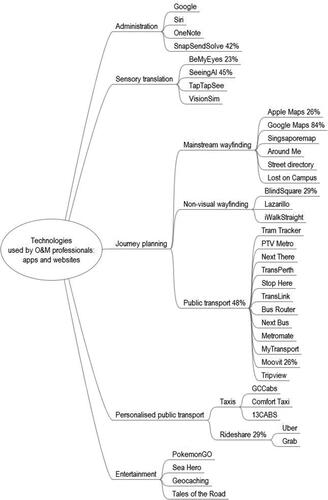

Australian O&M specialists identified 38 different travel-related apps or sites they used personally or with clients (), and 26% recognised that BlindSquare and other blind-friendly apps would transform O&M practice in the future.

What O&M technologies do O&M professionals want?

Instead of dreaming up new technologies, many Malaysian professionals simply wanted affordable devices – even long canes were imported and expensive. Although 39% of Malaysian professionals didn’t have a smartphone, its value as an orientation aid was recognised, particularly GPS, voice recognition, apps for public transport, and a “Where am I?” feature. Individual Malaysian participants wanted traffic lights with sound and voice, tactile maps with voiceover at intersections, and a waterproof talking white cane with full GPS facilities giving directions via headphones.

Nearly half of Australian participants wanted better technology training. One wanted improved accessibility for location-based games (e.g. PokemonGo); another wanted apps with more detailed pedestrian instructions; and one sought deeper research into what makes the basic long cane so effective.

Technology training

Malaysian O&M professionals knew they could access technology advice through their blindness/low vision agencies. The Australian survey asked more detailed questions about technology skill development.

When asked to rate their own technology skills, 26% of Australian participants said they help to train others, 29% said “I work it out fairly quickly”, and 36% said “I have enough technology skills to keep me going;” 48% acknowledged that they needed more skills, but only 19% said they would like more training; 7% said, “I use technology, but I don’t enjoy it much.” Only 32% felt they had good technology support and could get help the same day they needed it; 26% had some access to technology training, while 13% felt their access to training was limited. People learnt about travel technologies through trial and error (90%), friends or family members (48%), colleagues (87%), the IT team/helpdesk at work (32%), online help (32%), short courses (19%), and during their initial O&M qualification (10%).

Australian O&M professionals recognised that colleagues and clients with low vision or blindness are the subject matter experts in this field. They wanted better technology training within their initial O&M qualification, and then at work, with ongoing opportunities for theory-based practice. Suggestions for self-directed learning included online competency training, webinars and YouTube instructions, but participants also requested better live IT support at work from qualified assistive/adaptive technology experts and designated O&M colleagues.

Participants sought training in BlindSquare and other apps used by clients; and accessibility features and apps for both Apple and Android operating systems; using O&M technologies in conjunction with a long cane or dog guide; current specialist technologies that are available to clients through their workplace; and any new technologies that might support O&M clients to travel more effectively, or O&M specialists to work more effectively with their diverse and dispersed caseloads.

Discussion

The original purpose of this study was to build an evidence base to inform the development of new specialist O&M technologies that support clients’ travel. Instead, we found that low awareness of apps used by clients, unaffordability of devices, and inadequate technology training discouraged many O&M professionals from employing existing specialist or mainstream technologies, either in their client programmes or for broader professional purposes.

O&M professionals from Australia and Malaysia regarded O&M clients as the subject matter experts in O&M technologies, with good reason. Our parallel client study [Citation26] suggested that most O&M clients both in Australia and Malaysia, are using a smartphone. Clients named 108 apps and websites they used to support their travel in intricate ways, compared to the meagre 38 apps mentioned by Australian O&M professionals in this study, used mostly for journey planning.

Clearly, O&M client training programmes in Australia and Malaysia need to extend beyond the well-established canon of long cane and independent travel skills to embrace the benefits and complexity of travelling with mainstream technology.

Current technology use in Australia and Malaysia

Fewer Malaysian than Australian O&M professionals (61% v 100%) carried a smart phone, and access to specialist O&M technologies in Malaysia was limited by low awareness and affordability. These findings are consistent with Australia’s and Malaysia’s relative rankings on the Network Readiness Index [Citation27,Citation28].

Australian O&M specialists seemed quite well equipped with O&M technologies including smartphones, computers, apps, and specialist assistive devices supplied by many workplaces. Yet only half of these O&M specialists said their current devices met their needs. Their awareness of new O&M technologies was not matched with workplace budgets to buy, trial, and evaluate new technologies, to upgrade current devices, or to resolve persistent frustration from limited memory, battery life, data plans or internet connectivity.

Technology for client programmes

Our study indicated that before the Coronavirus (COVID-19) lock-down in early 2020, the inclusion of technology in a client’s O&M training programme depended on the O&M professionals’ interest, technology budget, skills and confidence. Given the near-universal use of smartphones by clients [Citation26,Citation29], O&M professionals needed to upskill and then build the use of O&M technologies into their teaching practice. The COVID-19 lock-down created an imperative for all O&M professionals to develop tele-practice skills. The long-term effect on O&M service models and the technology confidence of O&M professionals remains to be seen [Citation30].

Mainstream apps prompt O&M professionals to rethink how they build a client’s capacity for independent travel. The role of a human guide is changing, with GPS and live description services such as BeMyEyes and Aira able to provide human backup and visual interpretation of the immediate travel environment upon request. GPS has enabled O&M technologies to extend a client’s range of preview from immediate hazard detection and rote-learned routes to global orientation, expanding the client’s roaming range into unfamiliar areas. This expansion of life-space seems to help combat depression, benefit wellbeing and enhance quality of life [Citation26,Citation29].

New studies are exploring ways that technology might take care of the more routine elements of guide dog training [Citation31]. A smartphone with a special-effects app can motivate a child learning long cane or ball skills, while electronic tiles, beacons and related apps are used to motivate active searching and develop orientation to new places [Citation32]. An iPad is used as a teaching tool to magnify the travel landscape, zoom into signage, snap and sequence landmarks to map and rehearse a travel route, build O&M narratives with photo, video, audio and written elements to support concept development and sensory integration, and then report travel experiences and skill development to teachers and parents (discussion between LD and Alicia San Martin, O&M Specialist from Guide Dogs Victoria, 29 July 2019; unreferenced).

There are fresh travel challenges for O&M professionals and clients engaged in tele-practice: managing functional assessments safely, previewing training environments, working with available assistants, back-up plans to manage safety when the internet connection fails, managing divided attention and safety when juggling cameras and other devices, bags, hats and glasses, conversations, orientation, the dynamic travel environment, and traffic decisions.

For the traveller with low vision or blindness, there are always social challenges like working the room, recognising groups and individuals, entering and exiting conversations, and recognising when a conversation partner has left [Citation29]. Potential solutions include apps like SeeingAI to support facial recognition, live description apps and wearable technologies to foster social situational awareness during travel [Citation33].

Technology for professional training and development

There is an increasing range of O&M professional training opportunities and resources online that will ultimately benefit O&M clients.

Malaysia needs comprehensive professional training for O&M specialists, to meet the needs of more complex clients. In Australia, comprehensive O&M qualifications have been available since 1971 [Citation15], but university O&M programmes are fragile, lacking critical mass. There is a tension between shifting O&M content online to make an O&M professional qualification more widely accessible, and the requirement for face-to-face engagement to develop tacit, embodied O&M knowledge and accurate, timely verbal skills during blind community travel.

Internationally, O&M educators can use communication technologies to explore necessary cultural and geographical variations to O&M practice, identify feasible pathways for professional training in different countries, recruit trainee O&M specialists, share online training curricula, identify feasible locations for practical skills training, facilitate work placements/internships, and advertise vacant O&M positions.

Similarly, online professional development can be delivered through podcasts, webinars, videoconferencing, live-streamed conference presentations, online symposia, listservs, discussion forums, team meetings and training courses [Citation34,Citation35]. These media extend limited budgets, while increasing participation and access to rare professional expertise.

Communication technologies also facilitate formal research, linking O&M with other professions and end-users interested in technology development. Together, they can identify O&M problems that technology might solve, share innovative ideas, gain prompt answers to design questions, test prototypes and establish best practice in developing cost-effective O&M technologies for mainstream and specific user groups.

Meanwhile, an international online register of available and needed specialist technologies for resale, sharing or donation might be established to redeploy this costly equipment to useful places.

The need for technology training

In both Australia and Malaysia, there seemed to be fewer early adopters among O&M professionals than among O&M clients [Citation26] and an urgent need to build capacity in the O&M workforce to embrace accessible technology for travel. Systematic planning and budgeting are needed to upskill the technology majority and laggards. But how?

Self-directed online resources (e.g. YouTube) might suit early adopters [Citation13,Citation14], but technology laggards indicated they need a human touch with formal teaching from experts, a guided tour of online supports, timely face-to-face tech-support in the workplace, encouragement from colleagues, and bountiful practise opportunities to embody their new skills and build confidence using O&M technologies. Given the speed of technology developments, regular app training and updates are needed to supplement initial skill development and ensure that professional knowledge remains current. Our parallel study showed the potential for O&M clients to lead this technology training and upskilling of O&M professionals [Citation26]. Such meaningful work would help to address high unemployment rates in the Australian O&M client population [Citation36].

Ideas for new O&M technology developments

Notably, Australian O&M specialists did not call for embellishments to the long cane, or specialist personal travel aids. Rather, they looked for improved accessibility of mainstream devices and apps that could serve multiple purposes and connect with public nearables like Bluetooth beacons to improve access for all.

The O&M technology ideas (including smart canes) suggested by Malaysian O&M professionals already exist in various forms but were not affordable in Malaysia. Of greater importance were affordable long canes; streamlined, accessible footpaths; comprehensive training for O&M specialists; and consideration of the weather because torrential rain can happen any day, changing comfort, soundscape, viable travel routes and transport options for O&M clients.

Limitations and opportunities

Representatives from the main O&M service providers for adults were included in our Malaysian study, but O&M technologies and services for Malaysian children warrant further investigation. The Australian online cohort was small, with 16% of O&M specialists and 5% of guide dog mobility instructors involved [Citation15]. Updating the survey between Malaysian and Australian administration meant that we gained more detailed data from the Australian cohort, but statistical comparisons were limited. More work is needed to understand the barriers to learning for O&M technology laggards everywhere.

In summary

In a rapidly changing field, this study has benchmarked the pre-COVID-19 technology use and needs of O&M professionals, who recognised that clients’ knowledge of O&M technologies well exceeded their own. Technology is no longer optional but integral to travel for people with low vision or blindness in Australia and Malaysia. O&M professionals need upskilling to understand how O&M technologies can foster clients’ travel to more places, to complex or novel places, whether solo or supported.

The COVID-19 lock-down in early 2020 made O&M tele-services imperative rather than optional. O&M professionals are rapidly harnessing communication technologies to facilitate different kinds of client engagement in tailored assessment and training programmes, bridging huge geographical distances between service providers and clients, between colleagues, and between lecturers and trainee O&M specialists. The O&M profession, its service delivery models, and its professional development practices seem likely to be revolutionised by these adventures into tele-practice.

Supplement_-_surveys.docx

Download MS Word (93.8 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Miyagawa SH. Journey to excellence: development of the miliatry and VA blind rehabilitation programs of the 20th century. Lakeville, MN: Galde Press; 1999.

- Smith DL, Penrod WM. Adaptive technology for orientation and mobility. In: Wiener WR, Welsh RL, Blasch BB, editors. Foundations of orientation and mobility: History and theory. Vol. 1. New York, NY: AFB Press; 2010. p. 241–276.

- Giudice NA, Legge GE. Blind navigation and the role of technology. In: Helal A, Mokhtari M, Abdulrazak B, editors. Engineering handbook of smart technology for aging, disability, and independence. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2008. p. 479–500.DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470379424

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5 ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003.

- World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability, and health: (ICF) The International Classification for Functioning, Disability, and Health Geneva: World Health Organzation; 2002.

- Humanware. Blindness 2018. [4 August 2019]. Available from: https://store.humanware.com/hau/blindness

- Papadopoulos K, Koustriava E, Koukourikos P, et al. Comparison of three orientation and mobility aids for individuals with blindness: Verbal description, audio-tactile map and audio-haptic map. Assistive technology: the official journal of RESNA. Assist Technol. 2017;29(1):1–7.

- Pawluk DT, Adams RJ, Kitada R. Designing haptic assistive technology for individuals who are blind or visually impaired. IEEE Trans Haptics. 2015;8(3):258–278.

- Ayton LN, Blamey PJ, Guymer RH, et al.; Bionic Vision Australia Research Consortium. First-in-human trial of a novel suprachoroidal retinal prosthesis. PloS One. 2014;9(12):e115239

- Geruschat DR, Richards TP, Arditi A, et al. An analysis of observer-rated functional vision in patients implanted with the Argus II Retinal Prosthesis System at three years. Clin Exp Optom. 2016;99(3):227–232.

- Lahav O, Schloerb DW, Srinivasan MA. Newly blind persons using virtual environment system in a traditional orientation and mobility rehabilitation program: a case study. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(5):420–435. Sep

- Chai C, Lau B, Pan Z. Hungry Cat—a serious game for conveying spatial information to the visually impaired. MTI. 2019;3(1):12.

- Perkins. Orientation and mobility posts. Watertown, Massachusetts: Perkins School for the Blind eLearning; nd [27 July 2019]. Available from: https://www.perkinselearning.org/technology/orientation-mobility?page=4

- Mamer L. Orientation and mobility apps: Paths to Literacy for students who are blind or visually impaired; 2018. [updated 8 August 2018;27 July 2019]. Available from: http://www.pathstoliteracy.org/blog/orientation-mobility-apps.

- Deverell L, Scott B. Orientation and mobility in Australia and New Zealand: situational analysis and census. J Visual Impairment Blindness. 2014;108(1):77–82.

- Holmes N, Prentice K. iPhone video link FaceTime as an orientation tool: Remote O&M for people with vision impairment. Inter J Orientation Mobility. 2015;7(1):60–67.

- Barrett-Lennard A. The ROAM Project part 1: exploring new frontiers in video conferencing to expand the delivery of remote O&M services in regional Western Australia. Inter J Orientation Mobility. 2016;8(1):101–118.

- Bittner AK, Jacobson AJ, Khan R. Feasibility of using bluetooth low energy beacon sensors to detect magnifier usage by low vision patients. Optom Vis Sci. 2018;95(9):844–851. Sep

- Ferreira JC, Resende R, Martinho S. Beacons and BIM Models for indoor guidance and location. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2018;18(12):4374. Dec

- Dunn M. Melbourne introduce pilot trial for technology allowing blind people to navigate public spaces: www.news.com.au. ; 2017. [27 July 2019]. Available from: https://www.news.com.au/technology/innovation/inventions/melbourne-introduce-pilot-trial-for-technology-allowing-blind-people-to-navigate-public-spaces/news-story/6fb9810401eb34225f801e6e3f72a98c

- Merrick L. 5 Powerful Australian examples of beacon technology in app development 2016 [updated 21 June 2016. 27 July 2019]. Available from: https://www.buzinga.com.au/buzz/5-powerful-examples-beacon-technology-app-development/

- Neatebox. Striving to make equality a standard. Edinburgh (UK): Neatebox; [27 July 2019]. Available from: https://www.neatebox.com/

- Cuturi LF, Aggius-Vella E, Campus C, et al. From science to technology: orientation and mobility in blind children and adults. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;71:240–251.

- Deverell L, Meyer D, Lau BT, et al. Optimising technology to measure functional vision, mobility and service outcomes for people with low vision or blindness: protocol for a prospective cohort study in Australia and Malaysia. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018140

- Cawley B, Panek T. Plenary: technologies emerging role in enhancing guide dog mobility. Sydney, Australia: International Guide Dog Federation Seminar; 2018.

- Deverell L, Bhowmik J, Al Mahmud A, et al. Use of technology by orientation and mobility clients in Australia and Malaysia before COVID-19. 2020. Unpublished manuscript.

- World Economic Forum. Future preparedness: a conceptual framework for measuring country performance 2017. [cited 34 p.]. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_Preparedness_Conceptual_Framework_Measuring_Country_Performance_White_Paper_2017.pdf

- The World Bank. TCdata360: Country rank and value in the WEF Networked Readiness Index: The World Bank; 2016. [23 September 2019]. Available from: https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/h2f85e6e7?country=BRA&indicator=24721&viz=bar_chart&years=2016

- Deverell L, Bradley J, Foote P, et al. Measuring the benefits of guide dog mobility with the Orientation and Mobility Outcomes (OMO) tool. Anthrozoos. 2019;32(6):741–755.

- Shew A. Let COVID-19 expand awareness of disability tech. Nature. 2020;581(7806):9.

- Farrell J, McCarthy C, Chua C. Adapting HCI techniques for the design and evaluation of canine training technologies. Proceedings of the 30th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction; Melbourne, Australia. 2018. p. 189–193.

- Evans M. Innovative technology to support, motivate and engage clients, in particular children, with their O&M. Sixth Australasian Orientiation and Mobility Conference; 6-7 April 2018. Melbourne, Australia 2018.

- Joseph SL, Xiao J, Zhang X, et al. Being aware of the world: toward using social media to support the blind with navigation. IEEE Trans Human-Mach Syst. 2015;45(3):399–405.

- Perkins. Perkins eLearning: Perkins School for the Blind; 2019 [29 July 2019]. https://www.perkinselearning.org/

- Renwick Centre. Continuing Professional Education: RIDBC Renwick Centre for Research and Professional Training; 2019 [29 July 2019]. Available from: https://shortcourses.ridbc.org.au/

- Vision Australia. Employment research survey report. 2018 [26 June 2020]. Available from: https://www.visionaustralia.org/about-us/public-policy