Abstract

Background and objective

Everyday information and communication technologies (EICTs) are increasingly being used in our society, for both general and health-related purposes. This study aims to compare how older adults with cognitive impairment perceive relevance and level of EICT challenge between eHealth use and general use.

Methods

This cross-sectional study includes 32 participants (65–85 years of age) with cognitive impairment of different origins (due to e.g., stroke or dementia). The Short Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire+ (S-ETUQ+) was used, providing information about the relevance of EICTs and measuring the EICT level of challenge. Data were analysed with descriptive statistics, standardized z-tests and Fisher’s exact tests. The significance level was set to p < .05.

Results

The result shows that the perceived amount of relevant EICTs for eHealth use was lower in all 16 EICTs compared to those of general use. About the perceived level of challenge, a significant difference was detected in one of the seven included EICTs between eHealth use and general use.

Conclusions

In this sample, all EICTs were perceived as having lower relevance for eHealth use compared to general use, suggesting that the purpose of using an EICT affects the perceived relevance of it. Also, once an EICT is perceived as relevant and used for eHealth purposes, there seem to be little to no differences in perceived challenge compared to the same EICT used for general purposes.

All stakeholders, including health care providers, need to be aware of the hindrances that come with digitalization, making it challenging to many citizens to make use of digital solutions.

It is of great importance that social services including eHealth services be tailored to suit the individual/target group.

Older adults may need support and an introduction to EICTs to discover the potential relevance of the specific device and/or service.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

The need and use of everyday technologies (ETs) such as household appliances, smart phones, ATMs and self-check-in at airports is constantly increasing [Citation1] and influencing the way we live our lives [Citation2,Citation3]. Consequently, access to ETs and the ability to use ETs have become highly important to be able to perform essential everyday activities, including contact with health care [Citation4,Citation5]. ET includes both newly developed and more common well-known electronic, mechanical and technological artefacts and services used both at home and in society [Citation6]. A subgroup within ETs are everyday information and communication technologies (EICTs) including landline telephones, automated telephone services, mobile phones, smart phones, tablets and computers/laptops, which each enable the storage and exchange of information [Citation7,Citation8]. Besides the artefacts and devices per se, EICTs also include several functions such as making calls, searching for information, sending emails and sending text messages.

In all age groups, a variety of ETs are used but older adults may experience more challenges in using ETs than younger people do [Citation9–12]. Further, with increasing age, there is a risk of cognitive decline due to, for example, dementia or stroke and older adults already with mild and/or subjectively experienced cognitive impairments have shown that they have more challenges using ET than older adults without any cognitive impairment [Citation13,Citation14]. Also, there is often a more extensive need for health care with increasing age [Citation15]. However, increased age has been found to correlate with a decreased use of the Internet for health care, which is why Lepkowsky and Arndt [Citation16] highlight that the use of the Internet for communicating with health care providers has the potential to create a barrier to health care for older adults. With the overall growing use of technology, including the important relationship between use of EICTs and contact with health care, we must be attentive to EICTs as an important gateway to health care in the population of older adults with cognitive impairment.

In parallel with an increasing and aging global population [Citation17], there is a lack of health care professionals [Citation18] generating substantial challenges in health care [Citation19]. Digital solutions are transforming health care worldwide [Citation20] and eHealth services and functions are emphasized to play a crucial role in solving these challenges [Citation21–23]. The concept of eHealth has several definitions [Citation24]. Our definition of eHealth is the citizens’ use of EICTs in contact with health care, e.g., searching for health information on the Internet, calling the health care provider [Citation25], visiting patient portals and using online support systems [Citation26]. Consequently, the use of eHealth may, or may not, require interaction between the patient and the formal caregiver.

To benefit from EICTs, certain personal skills are required by each user, which can be conceptualized as ICT literacy (often used interchangeably with digital literacy). A widely used definition is that “ICT literacy is using digital technology, communications tools and/or networks to access, manage, integrate, evaluate and create information in order to function in a knowledge society” [Citation27]. Noteworthy is that, for eHealth literacy, i.e., for a person to access and be able to make use of eHealth, a wider combination of skills is essential and consists of several literacy types (traditional literacy, health literacy, computer literacy, science literacy, media literacy, information literacy [Citation28,Citation29] and Internet literacy [Citation29]). One suggested definition is that “eHealth literacy includes a dynamic and context-specific set of individual and social factors, as well as consideration of technological constraints in the use of digital technologies to search, acquire, comprehend, appraise, communicate, apply and create health information in all contexts of healthcare, with the goal of maintaining or improving the quality of life throughout the lifespan” [Citation30].

There is research showing that older adults with cognitive impairment may have a low level of eHealth literacy, which might lead to a limited opportunity to access eHealth and take advantage of its benefits [Citation11,Citation31]. A low level of eHealth literacy among older adults may be a contributing reason for the digital divide between age groups [Citation31]. In Sweden, it is reported that only 32% of people older than 76 years of age use health related e-services such as e-prescriptions, e-referrals and online booking of doctor appointments, whereas between 50 and 60% of those between 26 and 65 years of age take advantage of these services [Citation32].

Moreover, a Swedish study comparing older adults’ (55 years and older) health-related ICT use with their general ICT use showed that Internet use for health information was less common (38%), then general Internet use (57%), which may be due to factors such as low awareness of the existence of eHealth services, computer anxiety, experiences regarding ease of use and perceived usefulness [Citation33]. Also, the non-use of eHealth among older adults in Sweden can be due to their low confidence in trusting digital eHealth systems [Citation34]. In a recent interview study, none of the nine participating older adults with cognitive impairment used eHealth services requiring an e-ID (such as making health care appointments online) even though a couple of them used an e-ID for other purposes, e.g., for private banking tasks [Citation25]. That indicates that the specific purpose with the EICT may influence if it is perceived as relevant or not, and also the level of perceived challenge to use it. But this needs to be further investigated empirically to support or refute such assertions. Therefore, this study aims to compare the amount of relevant EICTs and the level of EICT challenges between eHealth use and general use as perceived by older adults with cognitive impairment.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethics

For the current study, a cross-sectional quantitative design was used. Approval for the study was granted from the regional ethical committee in Stockholm (2012/2031-31/5). The participants were given verbal and written information about the study at several occasions, both before giving consent and before the interviews. Informed consent was obtained in writing and orally from all participants.

Participants

This study included 32 participants between 65 and 85 years of age with cognitive impairments of different origins. Since this study has an exploratory design using a new version of the Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire (ETUQ), no power calculation was used. Characteristics of the participants are presented in .

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics, n = 32.

The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were (i) age >55 years, (ii) living in ordinary housing, (iii) cognitive impairment due to, e.g., mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis or stroke (at the earliest 6 months after a stroke), verified in the medical record, or self-experienced, (iv) having contact with health care and (v) being able to take part in the interview in Swedish. Exclusion criteria were (i) cognitive impairment related to an episode of depression, temporary confusion or a brain tumour, (ii) extensive aphasia, (iii) severe hearing loss requiring a sign language interpreter, (iv) a need for a language interpreter in the interview situation and/or (v) a Mini Mental State Examination Swedish Revision (MMSE-SR) [Citation35,Citation36] score <18 which could indicate disease severity suggesting that ET use was not likely in their daily lives.

The participants were recruited through purposive sampling from two primary care centres, two memory investigation units, a traffic medicine centre, and from a Memory Café for people with dementia in Stockholm, Sweden. Occupational therapists at the different sites assisted in the recruitment process by asking clients matching the inclusion criteria if they were interested in participation in the study. This information was communicated to the researchers responsible for gathering data. Regarding the recruitment from the Memory Café, the researchers visited the café to inform attendees about the study. Persons with cognitive impairment who matched the inclusion criteria could sign up for interest in participation. All potential participants received oral and written information about the study. After a few days, the researchers contacted potential participants by telephone. When a person was interested in participating in the study, a time and place for the interview was determined. Based on the participants’ own choice, all interviews were conducted in their homes.

Instruments and data collection

Socio-demographics, cognition and activities of daily living (ADL)

Information about the participants’ gender, age, living situation and years of education was gathered at the interview session. To further describe the sample, the MMSE-SR [Citation35,Citation36] and Frenchay Activity Index (FAI) [Citation37] were conducted (). The MMSE-SR was used to screen cognitive function and give an estimate for e.g., orientation, memory, language and logic-spatial ability [Citation35,Citation36]. The FAI is conducted as a structured interview based on questions about the frequency with which 15 ADL have been performed by the person in the recent past, the scale ranging from 0 (inactive) to 45 (very active) [Citation37].

ET use

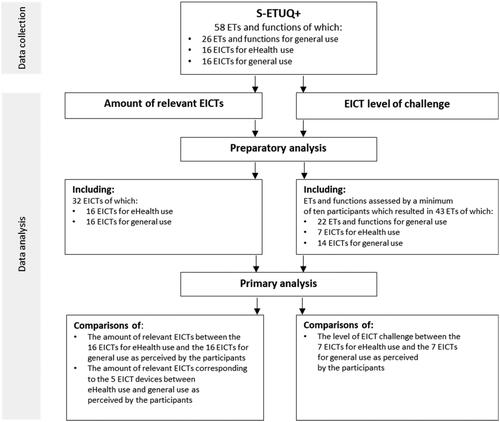

In the current study, the Short Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire+ (S-ETUQ+) was used to investigate the participants’ perceptions of ET relevance and ET level of challenge in a variety of ETs and associated functions used in different everyday activities and for different purposes in everyday life (such as the stove, the ATM, the lawn mower, the use of a computer to search for information on the Internet, or sending a SMS from a smart phone). The S-ETUQ+ comprises 58 ETs and functions and is an extended version of the Short Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire (S-ETUQ) [Citation38], which is based on the ETUQ [Citation39]. All 58 ETs and functions in the S-ETUQ+ were included in the data collection but during the data analysis the focus was on the 32 EICTs (see ). That is, in S-ETUQ+ the topic area labelled “Information/Communication” consists of 32 EICTs corresponding to five EICT devices (landline telephone, mobile phone, smart phone, tablet and computer). Out of the 32 EICTs, 16 are EICTs for eHealth use (such as using the mobile phone to call a health care provider) and 16 are EICTs for general use (such as using the mobile phone to call family/friends) (). In this study, if not otherwise stated, EICTs include both the devices and their functions.

Figure 1. Description of the included ETs and functions in the S-ETUQ+ used during data collection and the successive selection of EICTs in the analysis process.

Table 2. The table shows the 32 EICTs included in the S-ETUQ + of which 16 EICTs are for eHealth use (nos. 1–16) and 16 EICTs for general use (nos. 17–32).

The S-ETUQ + is used as a structured face-to-face interview. First, the respondent answers whether the ET is perceived as relevant or not. A relevant ET is defined as (a) the technology is available to the person and (b) the technology has earlier been used, is currently used, or is intended to be used by the person [Citation40]. Second, for relevant ETs the interviewer documents the participants’ reply concerning the level of challenge for each ET based on a scale with five defined response categories ranging from (5): the ET is used with no uncertainty/challenges at all to (1): the ET is not used even though it is relevant [Citation38]. The interviewer fills in the response alternatives that best correspond to the respondent’s reply to each question [Citation40]. In addition, the interviewer has the possibility to add comments from the participant that further explains her/his ET use.

During the S-ETUQ+ interview, each participant was asked about her/his use of ETs and their functions, first about the relevance of the ET for general use, including all the EICTs for general use, e.g., Do you use a mobile phone? If yes, e.g., How does it work for you, using the mobile phone to call? Then questions were asked regarding EICTs for eHealth use, e.g., Do you use a mobile phone in contact with health care? If yes, e.g., How does it work for you, using the mobile phone when calling for health care? This two-fold way of posing the EICT questions is specific for S-ETUQ+.

This is the first study using S-ETUQ+. However, most items have previously been used in ETUQ and/or in S-ETUQ. Both ETUQ and S-ETUQ have shown good psychometric properties and have been used in several studies investigating ET use among, e.g., older adults with or without cognitive impairments [e.g., Citation13,Citation41].

The data collection was performed by two interviewers (the first author (EJ) or fourth author (CBO)) between February 2016 and February 2018. The interview sessions followed a standardized procedure starting with collecting the socio-demographic information followed by FAI and S-ETUQ+ and ending with MMSE-SR even though the order was not strict and could, if necessary, be adjusted to the participant’s situation. Only the S-ETUQ + interview took on average about 50 min to complete, although with a large variation in interview length (SD 21.7).

Data analysis

The analysis was performed in two steps: preparatory analysis and primary analysis, for both amount of relevant EICTs and EICT level of challenge, regarding EICTs for eHealth use and EICTs for general use, respectively. The WINSTEPS software program version 3.92.1 was used [Citation42] to generate measures representing each ET’s level of challenge. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) [Citation43] and Excel (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA) were also used. In addition, www.socscistatistics.com was used to perform Fisher’s exact tests. The significance level was set to p < .05 throughout all analyses.

Preparatory analysis

Amount of relevant EICTs

First, regarding the amount of relevant EICTs, only the 16 EICTs for eHealth use and the 16 EICTs for general use were included (). The number of participants that considered each of these EICTs as relevant was counted for eHealth use and for general use, respectively. Second, each of the five EICT devices (landline telephone, mobile phone, smartphone, tablet and computer), containing 3–5 functions each, was counted separately regarding the amount of responses of relevance for eHealth use and for general use.

EICTs level of challenge

Since more items provide more stable measures, all 58 ETs and functions in the S-ETUQ+ were included in the initial analysis using WINSTEPS [Citation42]. First, all 58 ETs and functions that had not been assessed by at least 10 participants were removed from further analysis, because fewer than ten estimates give unstable measures [e.g., Citation44]. This process resulted in a total of 43 ETs and functions remaining. These 43 ETs and functions were distributed as follows: 22 ETs and functions for general use, seven EICTs for eHealth use and 14 EICTs for general use. Second, the ordinal raw scores for these 43 ETs and functions were converted into linear interval-like measures (logits) by using a Rasch rating scale model [Citation45]. By applying a Rasch model, it is possible to compare the EICTs even though the number of participants perceiving each EICT’s relevance may differ. The higher the measure in logits, the more challenging the EICT was perceived by the sample, and the lower the measure, the less challenging the EICT was perceived. This data analysis procedure has previously been described [Citation9,Citation38]. Third, since the purpose was to compare the same EICTs between eHealth use and general use, only those EICTs with a minimum of 10 estimates for both eHealth use and general use could be included (n = 7) (). The seven included EICTs were: (i) landline telephone, (ii) automated telephone services, (iii) mobile phone: call, (iv) smartphone: call, (v) smartphone: answer, (vi) smartphone: SMS/email and (vii) computer: search for information.

Primary analysis

Amount of relevant EICTs

The amount of EICTs perceived as relevant by the participants, i.e., the 16 EICT functions for eHealth and the 16 EICT functions for general use, were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Moreover, the five EICT devices, each containing 3–5 functions (i.e., the functions included in S-ETUQ+), were compared concerning the amount of responses of relevance for eHealth use and for general use as perceived for each of the EICTs by the participants.

EICTs level of challenge

The level of challenge for the seven EICTs for eHealth use and for general use was compared by standardized difference z-comparisons, including standard error (SE). The interpretation of the z-scores obtained in the analyses was based on the criterion that the differences in measures between the EICTs for eHealth use and for general use should be greater than ±1.96, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval [Citation46] to be determined as a statistical significant difference between the two EICT measures.

Results

Amount of relevant EICTs

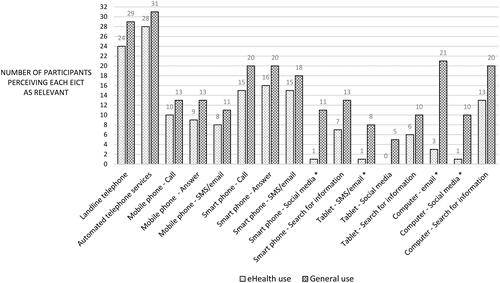

When comparing the perceived relevance of the 16 EICTs for eHealth use and the 16 EICTs for general use, it was demonstrated that the perceived relevance for eHealth use was lower throughout all EICTs () among the sample. Further, a significant difference in relevance, with a lower perceived relevance for EICTs for eHealth use, was found in four of the EICTs (25%); smart phone: social media (p < .01), tablet: SMS/email (p < .01), computer: email (p < .001) and computer: social media (p < .01). Also, just above 25% of the EICTs for eHealth were perceived as relevant whilst the number of relevant EICTs for general use was just above 45%.

Figure 2. A comparison between EICTs’ perceived relevance for eHealth use and for general use by showing the number of participants (total n = 32) who consider each of the EICTs as relevant. Four EICTs are marked with an * indicating that a significant difference between relevance for eHealth use and general use appeared in these.

Further, the amount of responses of relevance for the five EICT devices (landline telephone, mobile phone, smart phone, tablet and computer), each containing 3–5 functions between eHealth use and general use, showed significant differences in three of the devices: smart phone (p < .01), tablet (p < .01) and computer (p < .001) (). In these three EICT devices, the relevance was lower for eHealth use compared to general use. For the EICT devices landline telephone and mobile phone, no significant differences were shown in relevance between eHealth use and general use, even though the relevance was lower for EICTs for eHealth use. Further, the lowest number of responses of relevance arose for the tablet where about 7% of the functions were perceived as relevant for eHealth use, whilst 24% of the tablet functions where perceived as relevant for general use. The highest number of responses of relevance was regarding the landline telephone, where about 75% perceived it as relevant for eHealth use compared to 91% that perceived the landline telephone as relevant for general use.

Table 3. A comparison of relevance between eHealth use and general use for the five EICT devices, which in the S-ETUQ+ contains three to five functions each.

EICTs level of challenge

When comparing the level of challenge for the seven EICTs for eHealth use with the seven EICTs for general use, no significant differences were shown between the purpose of use for six of them (mobile phone: call, computer: search for information, smartphone: call, landline telephone, automated telephone service and smartphone: answer). In more detail, four of the EICTs (mobile phone: call, computer: search for information, smartphone: call and landline telephone) were perceived as more challenging for eHealth use, and three EICTs (automated telephone service and smartphone: answer and smartphone: SMS/email) were perceived as more challenging for general use. One EICT, the smartphone: SMS/email, showed a statistically significant difference between eHealth use and general use with the z-value 2.08. The smartphone: SMS/email had a lower level of challenge for eHealth use than for general use, which implies that the use of SMS/email for smartphone was perceived as easier in eHealth use (). By going back to raw data to read the written comments that the interviewers had noted based on the participants’ reflections during the interview, it became clear that the smartphone: SMS/email for eHealth use was exclusively for receiving SMS reminders from the health care provider, whereas it for general use almost only focussed on sending SMS.

Table 4. A comparison between eHealth use and general use regarding the level of challenge (measure) for each of the seven EICTs, including SE and z-score.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the amount of relevant EICTs and the level of EICT challenge between eHealth use and general use as perceived by older adults with cognitive impairment. The result shows that the amount of EICTs perceived as relevant for eHealth was lower in all 16 EICTs compared to general use, with a statistically significant difference within four of the EICTs (). Moreover, it was demonstrated that the EICTs’ relevance distributed across the five devices was lower for eHealth use with a significant difference compared to general use within three of the devices, namely the smart phone, the tablet and, the computer (). The fact that all EICTs were perceived as less relevant for eHealth use indicates that the intended purpose of using an EICT affects the perceived relevance of it. That is, among the participants it was more relevant to use EICTs for general purposes than for eHealth.

Lepkowsky and Arndt [Citation16] discovered differences in frequencies of use across five investigated technology domains (home, social, e-commerce, health care and technical) suggesting that EICTs should not be viewed as one homogeneous category. Some EICTs, such as emailing for eHealth purposes, often require a more complex composition when the user needs to log in with an e-ID to a personal health account before accessing the opportunity to email the health care provider, which is not the case when emailing for general purposes. The complexity with emailing for eHealth purposes might have been a contributing reason why no participant in this study used email to contact their health care providers. We agree with Lepkowsky and Arndt [Citation16], since the current study showed that EICTs had different relevance, which might be due to their purpose, and this is why we think it is necessary to divide and compare EICTs based on what they are used for, e.g., eHealth versus general use.

The fact that the participants perceived fewer EICTs for eHealth use as relevant was in turn reflected in the limited number of EICTs (n = 7) that were applicable for analysis when comparing the EICT’s level of challenge (). In six out of these seven EICTs, a non-significant difference between eHealth use and general use appeared. One way to interpret these non-significant differences may be that once an EICT is perceived as relevant and used for eHealth purposes, there are no or only small differences in perceived challenge compared to the same EICT used for general purposes. However, one EICT, the smartphone: SMS/email, showed a significant difference in level of challenge between eHealth use and general use. Interestingly, even though the smartphone: SMS/email was perceived as less relevant for eHealth, it was still perceived as having a significantly lower level of challenge for eHealth use compared to general use. The participants used the SMS function for both eHealth and general purposes, but none of them used the email function in the smartphone for eHealth and only a few used the email function for general purposes. The SMS function for eHealth was solely about receiving an SMS reminder about an appointment to the health care provider, which was a simple and easy service not requiring the participants to send text message as a reply. Rosenberg and Nygård [Citation47] describe three levels of communication with ET, where the first level is to receive signals from the ET, seen as communication with a low level of complexity. Despite this, when it comes to the participants’ general use of smartphone: SMS/email, it was associated with difficulties in writing SMS which they perceived as a complicated function of low usability, and something that several of them did not know how to use. According to Rosenberg and Nygård [Citation47], writing an SMS is an interaction found at the third level of communication with ET, indicating a high level of complexity where the user needs to act and respond with a sequence of actions in a certain way to make it work.

The use of an EICT and its perceived level of difficulty could be affected by a person’s ICT literacy and/or eHealth literacy. A previous interview study including older adults with cognitive impairment [Citation25] discovered that few EICTs were experienced as relevant for eHealth use possibly due to a low level of eHealth literacy, which might also be the case in the current study. Perhaps a relatively low level of ICT literacy becomes even more pronounced in terms of specific and more complex eHealth literacy? At any rate, a consequence of low ICT literacy and/or eHealth literacy is the non-use of EICTs. Most of the participants in the present study did not use an e-ID, which is a prerequisite for many personal health related errands (e.g., online services in the Swedish health care system), and thereby can be a distinguishing factor for use versus non-use of several online services. Also, closely connected to ICT and/or eHealth literacy is the awareness of EICTs, where lack of awareness has been pointed out as a reason for the lack of interest, and thereby also the non-use of EICTs [Citation31]. One way to increase awareness, for ICT literacy as well as eHealth literacy, eventually to make them more relevant among older adults with cognitive impairment, maybe by providing tailored information about EICTs and the possibilities of using them.

An important factor regarding decreased use of EICTs is increasing age. The decreased use of EICTs has been shown to be correlated with higher age and to be most pronounced regarding health related EICT use [Citation16]. Also, eHealth literacy may be negatively affected with higher age [Citation48] and the anticipated psychosocial impact for web-based eHealth applications has been shown to negatively correlate with increasing age [Citation49]. Regardless of the underlying reason(s) for not using EICTs, there is a risk of inequality between users and non-users [Citation50] which often means that younger people benefit from using the EICTs whilst older adults do not. In Sweden, 18% of citizens 76 years of age or older experience public digital services available to all citizens (e.g., e-services in healthcare, public transport and the Swedish tax Agency) as making life more difficult whilst younger age groups consider digital services as simplifying life [Citation32]. Younger people and older adults use EICTs to varying degrees and with different skills which in turn creates a digital divide [Citation48] pointing to the consequences for older adults who, to a greater extent than younger ones, fail to benefit from digitalization and thus risk being left outside of the digital society. Since it is more common that older adults with cognitive impairment are low or non-users of the Internet than other age-groups, and compared to those without cognitive impairment, older adults with cognitive impairment are at a particularly great risk of not benefitting from the amount of information nor from the content of the information that is offered through the Internet. Also, Seifert et al. [Citation51] discovered that older adults who were non-users of the Internet experienced a sense of social exclusion from the digital world, since they had a certain appreciation of the benefits with the Internet. Non-users among older adults often acknowledge that technological solutions are useful but for someone else, not themselves [Citation52].

Older adults with cognitive impairment might exhibit limitations, e.g., finding health related information online [Citation11]. Also, the interest in and the use of EICTs for eHealth have been shown to vary among older adults with cognitive impairment, depending on their diagnosis, where those with subjective memory complaints and MCI had more interest in EICTs compared to those with dementia [Citation53]. Besides having interest in EICTs, it is important to acknowledge that access to the Internet and to different EICTs is not the same as competently using the technology [Citation54]. Further, it is also fundamental to consider the use of EICTs for eHealth versus general purposes as filling a need/gap. When it comes to EICT use for eHealth purposes, it has been shown that personal interaction and face-to-face meetings with health care providers are highly valued, and that it is common to use well known EICTs (e.g., the landline telephone) to contact health care [Citation4,Citation25]. Also, if there are well-established and satisfying ways of contacting health care, it might be irrelevant to consider using other EICTs than those already well known. Additionally, learning new approaches, devices and services can be both difficult and time and energy-consuming [Citation55] and therefore not prioritized. It is also likely that a well-known EICT matches a person’s skills of using that particular EICT. Further, actual use of a technology has been found to be a decisive factor for people with cognitive impairment in maintaining use and/or when learning a new EICT [Citation47]. In the complex process of learning how to use a new EICT for eHealth purposes, it might be easier to learn it if the same EICT already is used for general purposes.

The participants in the current study might, due to their cognitive impairments, have extended difficulties when making use of EICTs in different important situations, such as in contact with health care. Since digital solutions are a necessity from a societal perspective, stakeholders such as political entities, health care organizations and single health care providers need to offer support to those who involuntarily stand outside the digital society. Also, society has an important role in narrowing the digital divide and minimizing negative consequences. The Swedish National Digitalisation Council [Citation56] has addressed several challenges needed to be solved to establish a digital society, such as the importance of all citizens having basic digital knowledge and a digital identity (i.e., e-ID). Klimova et al. [Citation57] suggest that health professionals need to provide essential equipment and educational programmes to help older adults improve their access to and adaption of eHealth services (e.g., home-visiting services with an IT assistant). Also, eHealth services need to be personalized, formed and tailored to suit the target group [Citation58]. Health care providers are recommended to play an important role in providing support to those patients who have low eHealth literacy and thus need support in navigating among often-conflicting health information available on the Internet [Citation59]. From an ethical perspective, it is crucial that all stakeholders, especially those delivering eHealth solutions, design interventions in an ethical and fair way, fostering health equity for all population groups and taking into account the needs of disadvantaged groups [Citation20]. To end, for all of them left outside the digital society today and/or in the future, it is of great importance to create solutions making it possible for them to take advantage of the benefits of EICT solutions in society, including eHealth.

Methodological considerations

This study was conducted with 32 participants and the number of included EICTs was limited to those included in S-ETUQ+. The small sample calls for caution in how to interpret the results. Due to the explorative nature of the study, no power calculation was done. We have not controlled for gender, though the number of female participants was close to half of the male participants. However, gender has not been shown to impact differences in technology use [Citation31,Citation60]. Anyhow, the result can increase our awareness that the use of EICTs for eHealth and general purposes among older adults with cognitive impairment is associated with challenges and that there seems to be lower relevance for EICTs in eHealth use than for general use. No control group was included since the purpose with this study was not to compare groups nor test an intervention.

Further research

In the light of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, this study underscores the need of EICTs, both for eHealth and general purposes, particularly important for older adults who are at great risk of being affected by COVID-19 and therefore certainly need access to societal and health related information, usually offered online. This highlights the importance of further research regarding the use and non-use of EICTs among older adults with cognitive impairment. It is also important to investigate the use of EICTs in less digitized contexts and in different countries. Also, further research could investigate factors, such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and different disabilities within the population of older adults with cognitive impairment that might affect whether EICTs for different purposes are used or not.

Conclusions

This study shows that the participating older adults with cognitive impairment perceived all 16 EICTs as having lower relevance for eHealth use compared to general use. This might reflect that the purpose of using an EICT (eHealth versus general) affects the perceived relevance of it. Further, no significant differences were shown regarding the perceived level of difficulties in six of the included seven EICTs. We interpret this as, once an EICT is perceived as relevant and used for eHealth purposes, there is little to no difference in perceived challenge compared to the same EICT used for general purposes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the 32 participants who have shared their perceptions on technology use so generously. The authors are also grateful to all professionals who enabled the recruitment of participants.

Disclosure statement

The authors confirm that there is no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Emiliani PL. Assistive technology (AT) versus mainstream technology (MST): the research perspective. Technol Disabil. 2006;18(1):19–29.

- Ryd C, Malinowsky C, Öhman A, et al. Older adults' experiences of daily life occupations as everyday technology changes. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81(10):601–608.

- Walsh RJ, Lee J, Drasga RM, et al. Everyday technology use and overall needed assistance to function in the home and community among urban older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38:1–9. DOI:10.1177/0733464819878620

- Nymberg VM, Bolmsjö BB, Wolff M, et al. 'Having to learn this so late in our lives…' Swedish elderly patients' beliefs, experiences, attitudes and expectations of e-health in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(1):41–52.

- Ware P, Bartlett SJ, Pare G, et al. Using eHealth technologies: interests, preferences, and concerns of older adults. Interact J Med Res. 2017;6(1):e3.

- Nygård L, Starkhammar S. The use of everyday technology by people with dementia living alone: mapping out the difficulties. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(2):144–155.

- Gagnon MP, Légareé F, Labrecque M, et al. Interventions for promoting information and communication technologies adoption in healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD006093.pub2

- Wallcook S, Nygård L, Kottorp A, et al. The use of everyday information communication technologies in the lives of older adults living with and without dementia in Sweden. Assist Technol. 2019;1–8. DOI:10.1080/10400435.2019.1644685

- Nygård L, Pantzar M, Uppgard BM, et al. Detection of activity limitations in older adults with MCI or Alzheimer's disease through evaluation of perceived difficulty in use of everyday technology: a replication study. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(3):361–371.

- Hedman A, Lindqvist E, Nygård L. How older adults with mild cognitive impairment relate to technology as part of present and future everyday life: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):1–12.

- Czaja SJ, Sharit J, Hernandez MA, et al. Variability among older adults in Internet health information-seeking performance. Gerontechnology. 2010;9(1):46–55.

- Rosenberg L, Nygård L, Kottorp A, et al. Perceived difficulty in everyday technology use among older adults with or without cognitive deficits. Scand J Occup Ther. 2009;16(4):216–226.

- Malinowsky C, Kottorp A, Wallin A, et al. Differences in the use of everyday technology among persons with MCI, SCI and older adults without known cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(7):1193–1200.

- Ryd C, Nygård L, Malinowsky C, et al. Associations between performance of activities of daily living and everyday technology use among older adults with mild stage Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment. Scand J Occup Ther. 2015;22(1):33–42.

- Hayes SL, Salzberg CA, McCarthy D, et al. High-need, high-cost patients: who are they and how do they use health care? A population-based comparison of demographics, health care use, expenditures [Internet]; 2016 (Commonw Fund); [cited 2020 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.colleaga.org/sites/default/files/attachments/1897_hayes_who_are_high_need_high_cost_patients_v2.pdf

- Lepkowsky CM, Arndt S. The Internet: barrier to health care for older adults? Pract Innov. 2019;4(2):124–132.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population prospects 2019. Volume I: comprehensive tables (ST/ESA/SER.A/426); 2020; [cited 2020 Jan 15]. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf

- Marć M, Bartosiewicz A, Burzyńska J, et al. A nursing shortage – a prospect of global and local policies. Int Nurs Rev. 2019;66(1):9–16.

- European Commission, European Economy. The 2018 ageing report: economic and budgetary projections for the EU Member States (2016–2070). Institutional paper 079; 2018; [cited 2020 Feb 25]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/ip079_en.pdf

- Brall C, Schröder-Bäck P, Maeckelberghe E. Ethical aspects of digital health from a justice point of view. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(Suppl. 3):18–22.

- Editorial. A digital (r) evolution: introducing The Lancet Digital Health. The Lancet Digital Health; 2019.

- Hall AK, Stellefson M, Bernhardt JM. Healthy Aging 2.0: the potential of new media and technology. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E67.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: eHealth Action Plan 2012–2020 – innovative healthcare for the 21st century; 2019; [cited 2019 Dec 12]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/ehealth-action-plan-2012-2020-innovative-healthcare-21st-century

- Boogerd EA, Arts T, Engelen LJ, et al. “What Is eHealth”: time for an update? JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(1):e29.

- Jakobsson E, Nygård C, Kottorp A, et al. Experiences from using eHealth in contact with health care among older adults with cognitive impairment. Scand J Caring Sci. 2019;33(2):380–389.

- Watkins I, Xie B. eHealth literacy interventions for older adults: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(11):e225.

- ICTL Panel. Digital transformation: a framework for ICT literacy. Educational Testing Service; 2002; [cited 2020 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/ICTREPORT.pdf

- Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8(2):E9.

- Chan CV, Kaufman DR. A framework for characterizing eHealth literacy demands and barriers. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e94.

- Griebel L, Enwald H, Gilstad H, et al. eHealth literacy research—Quo vadis? Inform Health Soc Care. 2018;43(4):427–442.

- Hunsaker A, Hargittai E. A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media Soc. 2018;20(10):3937–3954.

- Internetstiftelsen. Svenskarna och Internet; 2019; [The Swedes and the Internet 2019]; [cited 2019 Dec 18]. Available from: https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/app/uploads/2019/10/svenskarna-och-internet-2019-a4.pdf

- Wiklund-Axelsson SA, Melander-Wikman A, Näslund A, et al. Older people's health-related ICT-use in Sweden. Gerontechnology. 2013;12(1):36–43.

- Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner [Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions]. Hälso- och sjukvårds-barometern 2019. Befolkningens attityder till, förtroende för och uppfattning om hälso- och sjukvården [The Health Care Barometer 2019. The population's attitudes to, trust in and perception of health care]; 2020; [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://webbutik.skr.se/bilder/artiklar/pdf/7585-875-3.pdf?issuusl=ignore

- Palmqvist S, Terzis B, Strobel C, et al. MMSE-SR: the standardized Swedish MMSE. 2nd version. Stockholm: Svensk Förening för Kognitiva sjukdomar; 2013.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.

- Holbrook M, Skilbeck CE. An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age Ageing. 1983;12(2):166–170.

- Kottorp A, Nygård L. Development of a short-form assessment for detection of subtle activity limitations: can use of everyday technology distinguish between MCI and Alzheimer's disease? Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(5):647–655.

- Rosenberg L, Nygård L, Kottorp A. Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire: psychometric evaluation of a new assessment of competence in technology use. OTJR-Occup Part Heal. 2009;29(2):52–62.

- Nygård L. Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire (ETUQ). Unpublished manual, research version 2. Stockholm, Sweden: Karolinska Institutet; 2008.

- Hedman A, Nygård L, Kottorp A. Everyday technology use related to activity involvement among people in cognitive decline. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71(5):7105190040p1.

- Linacre JM. Winsteps – Rasch measurement computer program [computer software]. Version 3.92.1. Chicago: MESA Press; 2017.

- IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp.; 2017.

- Hedman A, Kottorp A, Almkvist O, et al. Challenge levels of everyday technologies as perceived over five years by older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(10):1447–1454.

- Bond T, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Routledge; 2015.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Revised edition. New York (NY): Academic Press; 2013.

- Rosenberg L, Nygård L. Learning and using technology in intertwined processes: a study of people with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer's disease. Dementia (London). 2014;13(5):662–677.

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM. The digital divide among low-income homebound older adults: Internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/Internet use. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(5):E93.

- Wiklund Axelsson S, Nyberg L, Näslund A, et al. The anticipated positive psychosocial impact of present web-based e-health services and future mobile health applications: an investigation among older Swedes. Int J Telemed Appl. 2013;2013:509198.

- Kottorp A, Nygård L, Hedman A, et al. Access to and use of everyday technology among older people: an occupational justice issue – but for whom? J Occup Sci. 2016;23(3):382–388.

- Seifert A, Hofer M, Rössel J. Older adults’ perceived sense of social exclusion from the digital world. Educ Gerontol. 2018;44(12):775–785.

- Huber L, Watson C, Roberto KA, et al. Aging in intra-and intergenerational contexts: the family technologist. In: Kwon S, editor. Gerontechnology: research, practice, principles in the field of technology. New York (NY): Springer Publishing Company; 2017. p. 57–90.

- LaMonica HM, English A, Hickie IB, et al. Examining internet and eHealth practices and preferences: survey study of Australian older adults with subjective memory complaints, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e358.

- Malinowsky C, Nygård L, Kottorp A. Using a screening tool to evaluate potential use of e-health services for older people with and without cognitive impairment. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(3):340–345.

- Christiansen L, Lindberg C, Sanmartin Berglund J, et al. Using mobile health and the impact on health-related quality of life: perceptions of older adults with cognitive impairment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2650.

- Digitaliseringsrådet [Digitization Council]. En lägesbild av digital trygghet [A report of digital security]; 2018; [cited 2019 Oct 16]. Available from: https://digitaliseringsradet.se/media/1131/laegesrapport-digital-trygghet-klar-20.pdf

- Klimova B, Maresova P, Lee S. Elderly’s attitude towards the selected types of e-Health. Healthcare. 2020;8(1):38.

- Reiners F, Sturm J, Bouw L, et al. Sociodemographic factors influencing the use of eHealth in people with chronic diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:645.

- Lee K, Hoti K, Hughes JD, et al. Dr Google is here to stay but health care professionals are still valued: an analysis of health care consumers’ internet navigation support preferences. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(6):E210.

- Kottorp A, Malinowsky C, Larsson-Lund M, et al. Gender and diagnostic impact on everyday technology use: a differential item functioning (DIF) analysis of the Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire (ETUQ). Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(22):2688–2694.