Abstract

Purpose

Wheelchair skills trainings are a vital aspect wheelchair provision yet are arguably overlooked and extent to which training is provided in the Irish context is highly variable. The primary aim of this study was to quantify whether a need exists to further develop wheelchair skills training in Ireland.

Methods

A cross sectional survey was conducted using SurveyMonkeyTM. Irish health professionals involved in wheelchair service delivery were asked how they offer wheelchair skills trainings and what components of wheelchair skills they train. To collect qualitative information, questions also explored how health professionals would like training to develop.

Results

Consensus among respondents was that training is often provided to new users (n = 91, 89%), however, it is limited to mostly transfers and simple mobility techniques. Further, it was reported that advanced mobility skills are sometimes (n = 81, 51%) or never taught (n = 81, 21%). The respondent’s confidence instructing various skills corresponded with the frequency of instruction. The responses captured a shared interest in developing standardised training programs and the development of continued education training in the area.

Conclusion

The findings from this study reinforce that a present need exists to further develop wheelchair skills training in Ireland, with the aim of improving Irish wheelchair service providers’ knowledge and confidence in advanced wheelchair skills needed to mobilise and perform activities of daily living.

Current clinical practice in Irish wheelchair service delivery includes basic wheelchair skills training, whereas training in advanced skills needed for improved independent mobility is highly variable.

This study raises awareness that health professionals seek formal education and training in wheelchair skills to improve their knowledge and confidence in providing wheelchair skills training.

There is a need to develop wheelchair skills training opportunities, both as a requirement for stakeholders involved in wheelchair provision and to address an unmet need for wheelchair users.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Obtaining an appropriate wheelchair is imperative for approximately seventy-five million people with a physically disability globally and one in one hundred people in the Republic of Ireland, to support an individual’s personal mobility and independence [Citation1]. Wheelchair procurement alone cannot ensure safe and effective use. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) [Citation2,p.14], established that it is the duty of the member states to “take effective measures to ensure personal mobility with the greatest possible independence for persons with disabilities”. Yet despite this named duty, there is no national guideline or specific policy that supports wheelchair service delivery in Ireland, the focus of this study.

Important guiding documents published by the WHO [Citation3] and World Vision [Citation4] name user training as a key component to service delivery, because if used ineffectively, a wheelchair can aggravate a physical condition, cause injury [Citation5–9], and consequently compromise participation and inclusion [Citation10–12]. While many educational institutions teach wheelchair service provision at a basic level, majority fall below the recommended teaching hours suggested by the WHO eight-step model [Citation3,Citation13,Citation14]. Subsequently, newly trained professionals may not be acquiring the necessary skills needed to provide adequate wheelchair service provision. Ensuring availability of a competent workforce to support the navigation of poor service systems was named a key position to address the global challenges of wheelchair service delivery [Citation15,Citation16].

When offered by formally trained staff, wheelchair skills training has been shown to be safe, practical, and have a clinically significant effect on the independent wheeled mobility of individual wheelchair users [Citation17–23]. Yet, limitations have been identified and some evidence suggests that current delivery of wheelchair skill trainings is sub-optimal [Citation24,Citation25].

A cross-sectional survey was used to ask Irish health professionals working in wheelchair services how wheelchair skills trainings are delivered, what components of wheelchair skills they provide, either formally or informally, and how they as health professionals would like to see training in this area develop. The primary aim of this study was to quantify whether a need exists to further develop wheelchair skills training in Ireland, to better align with the rights-based approach to wheelchair provision outlined by the WHO.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted to collect descriptive data from health professionals known to provide wheelchair services in Ireland. An online survey was selected for data collection as internet surveys are known to provide the means to contact target groups easily and effectively [Citation26]. To reach health professionals throughout the Republic, this method aimed to improve response rates as online surveys provide accessibility to professionals with limited time and that are geographically spread out [Citation27].

To identify whether any formal wheelchair skills training programs are in current use in Ireland, wheelchair skills training program material was searched on the HSE website, Irish Wheelchair Society, Invacare, MMS Medical, Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy, and Assist Ireland. No validated wheelchair skills programs were apparent. Likewise, the researcher sent emails to the HSE, the Irish Wheelchair Association, and the company Whizz-Kidz. Each response confirmed no programs were currently offered in Ireland to wheelchair users.

Measurement

Best et al. conducted a survey investigating similar findings in entry-to-practice occupational therapy and physical therapy programs in Canada [Citation25]. Permission was requested to access and adapt their original survey to the Irish context. After receiving permission from the Canadian research team, the survey was formatted using SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). A pilot study using the adapted survey tool was first sent to University of Limerick Education and Health Sciences staff. The finalised version was based on feedback from pilot testing, which improved the content and clarity of the questions. The finalised survey included 25 questions in total (see Supplementary Appendix 1). Participants were informed of the purpose of the survey in an informational letter sent to them by the association they belonged to, these included: Association of Occupational Therapists Ireland (AOTI), the Irish Posture and Mobility Network (IPMN), and Irish Society of Chartered Physiotherapists (ISCP). Consent was obtained at the start of the survey. Respondents were not financially reimbursed for their participation.

Sample

A purposive sampling method was used. To capture wheelchair service providers that deliver user training, associations and special interest groups were contacted as they employ known professionals linked to wheelchair service delivery. This method allowed the research team to achieve contact with professionals throughout the entire Republic of Ireland. Emails were sent to the organisations requesting their participation in contacting professional members of the bodies. After approval was received by the University of Limerick Education and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee in October 2018, necessary documents were sent to the associations contacted requesting that they forward the informational email and link to the online survey to their members.

To improve response rates as suggested by Kitchenham and Pfleeger [Citation27], the survey was designed to take less than 15 min to complete. Requests were sent to the associations to contact participants again after distribution requesting their participation once more in December 2018. AOTI was the only association that confirmed recirculation. Without being able to confirm how many professionals received the invitation email, 146 professionals opened the web link to the survey and 91 participants completed the survey. Participants included occupational therapists and one technical personnel working throughout the Republic of Ireland.

Demographic and descriptive information

Respondents were asked a series of demographic questions aimed to describe the sample, which included profession, current position, employment in what type of facility, age of clientele, location of professional training, total years of professional practice, and years working in wheelchair service delivery. Age of clientele was further broken down to capture whether age related skill potential influenced skill level taught. Descriptive information was collected about wheelchair service delivery generally, including number of wheelchairs prescribed in 3 months, number of manual or powered wheelchairs prescribed in 3 months, type of instruction provided, topics covered including wheelchair safety and maintenance, and number of health professionals on staff that provide such material.

Components of wheelchair skills training and confidence instructing

Respondents were asked to describe wheelchair skills training practices offered at their facility by estimating how often training was provided in wheelchair maintenance and repair, transfers, basic mobility, advanced mobility, and wheelchair skills used to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Respondents were also asked to describe their confidence instructing the various components of wheelchair skills listed above. Questions that captured “how often” and “how confident” as responses used Likert scale type response options: always, almost always, sometimes, rarely, never, very confident, somewhat confident, and not at all confident.

Amount of wheelchair skills training

Respondents were asked to estimate the average number of wheelchair skills training sessions completed with wheelchair users and to estimate the average number of hours spent completing wheelchair skills training with users.

Formal wheelchair skills training programs in practice

To identify formal and validated training programs currently used to inform clinical practice, respondents were asked how often formal training programs were used at their facility. Based on the extensive online and literature search two wheelchair skills training programs were identified: Wheelchair Skills Program (WSP) (Halifax, Canada) and Whizzkidz (London, UK). Respondents were asked if they used either of the two identified, “none,” or “other” and provided a text box for respondents to list other sources. We also asked respondents to indicate the length of time a formal training program was used in their facility.

Additional wheelchair skills training received by health professionals

Respondents were asked to describe the methods of training they received in wheelchair skills outside of their qualification training.

Perceived improvements to implement in the development of wheelchair skills training in Ireland

To understand how professionals in Ireland would like to see wheelchair skills training advance in the future, respondents were asked to comment on what additional training they would avail if it were made available and how they would like to see wheelchair skills training offered to users, by health professionals, develop. Text boxes were provided for respondents to enter their comments in response to these questions.

Analyses

Raw data were collected on Survey Monkey SurveyMonkey and were transferred into Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS. Open responses were coded in Microsoft Word. Quantitative data were combined, and summary statistics were carried out, when appropriate, using SPSS Statistics (i.e., frequencies, proportions, and cross-tabulations). Qualitative responses were inputted into an Excel spreadsheet and a content analysis was carried out. The common responses were grouped in Microsoft Word tables. Then, themes were chosen based on common responses. These themes were cross-checked between the student researcher and the research supervisor to reduce researcher bias and improve reliability regarding the interpretation of the open-ended responses.

Results

Demographic and descriptive information

Most respondents were occupational therapists, and one was technical personnel. Majority of respondents were employed in primary care, community care, and rehabilitation. The ages of the clientele served by respondents ranged from children under 12 years old to adults 65 years of age and older. Most respondents received their professional training in Ireland, 20 (n = 91, 22%) received their training in the United Kingdom, and 6 (n = 91, 7%) respondents received their training elsewhere. Years in professional practice and years practicing in wheelchair service delivery ranged from less than 5 years to 20 years or more. A summary of other demographic information is shown in and .

Table 1. Summary of demographic information by setting and role (N = 91).

Table 2. Summary of demographic information by years in service delivery and role (N = 91).

Components of wheelchair skills training

69 (n = 91, 76%) respondents reported that they provide both verbal and written material when instructing users and caregivers in wheelchair maintenance and repair. 44 (n = 91, 48%) respondents reported that 1 to 4 health professionals at their facility provide this instructional material to users and their caregivers.

The most common component of wheelchair skills “always” included in training sessions by health professionals was transfers. Many respondents reported that basic mobility skills were “always” taught. Wheelchair skills needed to perform advanced wheelchair mobility skills and instrumental activities of daily living were the least common components of wheelchair skills included in training by health professionals. A summary of the frequency of occurrence and percentage of responses that health professionals reported instructing each component skill is shown in .

Table 3. Summary of each component of wheelchair skills taught reported by health professionals showing frequency of occurrence and percentages of responses.

When comparing components of wheelchair skills taught to the different ages of clientele, reports that transfer skills were “always” taught to clients of all ages were relatively consistent. Instruction in basic mobility skills were split between “always” and “sometimes” across all ages. Advanced mobility skills were consistently reported to be instructed “sometimes” across all ages.

Confidence instructing

When comparing reported confidence instructing users in each component of wheelchair skills by health professional’s position, the sample size of clinical specialists and qualified technical personnel was quite small. Nonetheless, higher confidence was consistently reported from more experienced staff in comparison to staff grade therapists in all component skills. The lowest reported confidence was observed in advanced mobility skills amongst both senior grade and staff grade therapists. and show a detailed breakdown of health professional’s reported confidence instructing basic and advanced mobility skills by their position, where very confident* represents the collapsed variables for “very confident” and “moderately confident” and somewhat confident* represents the collapsed variables for “somewhat confident” and “only slightly confident”.

Table 4. Detailed breakdown of the percentages of reported confidence instructing basic mobility skills by health professional’s position.

Table 5. Detailed breakdown of the percentages of reported confidence instructing advanced mobility skills by health professional’s position.

The most common component of wheelchair skills that health professionals reported to be “very confident” instructing users in, were transfers, skills needed to perform ADL, and basic wheelchair mobility skills. The most common component of wheelchair skills that professionals reported feeling only “somewhat confident” in was advanced wheelchair mobility skills. A summary of clinician’s reported confidence instructing each component skill is shown in .

Table 6. Summary of health professionals’ reported confidence instructing each component of wheelchair skills taught showing percentages of responses.

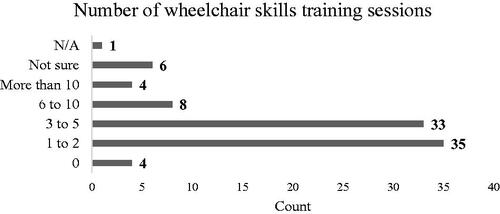

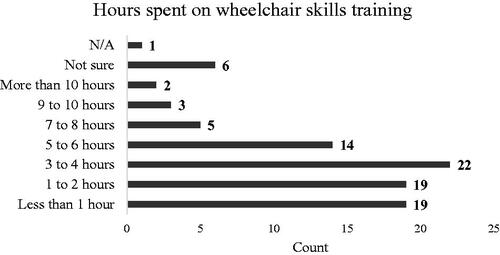

Amount of wheelchair skills training

Majority of the respondents reported that wheelchair skills training is completed with new wheelchair users 81 (n = 91, 89%). 60 (n = 91, 66%) reported that roughly 1–4 h were spent completing skills training with wheelchair users, in roughly 1–5 training sessions 68 (n = 91, 75%). Further breakdown of the number of sessions and hours spent completing training with users by Irish health professionals is shown in and .

Formal wheelchair skills training program in practice

When asked about the use of formalised training programs for manual wheelchairs in clinical practice, most respondents reported that they currently do not use either the WSP 67 (n = 82, 82%) or Whizz Kids 62 (n = 82, 76%) training programs. However, 15 (n = 46, 33%) of respondents reported always using “other” formal training programs. The most reported “other” formal program was the HSE Policy on Provision of Powered Mobility Equipment for Adults, which does not cover manual wheelchair skills. The other training programs reported were: Back Up, a UK produced wheelchair skills manual for individuals with spinal cord injury, and Go Kids Go, another UK produced wheelchair skills training program. When asked how many years a formal training program was used in clinical practice, the largest response observed was “not applicable” 54 (n = 91, 59%), further indicating that formal training programs are not used commonly.

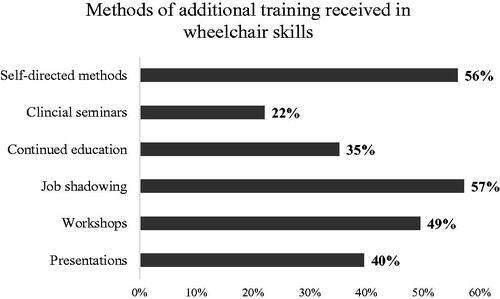

Methods of additional wheelchair skills training received by health professionals

Health professionals reported self-directed learning methods and job shadowing as the two most common methods for obtaining wheelchair skills training outside of professional qualification training. shows a further breakdown of additional training methods used by health professionals.

Perceived improvements to implement in future development of wheelchair skills training in Ireland

Themes emerged within the free responses to “what additional training in wheelchair skills instruction health professionals would avail of if it were provided?”. The themes developed regarding wheelchair maintenance and advanced mobility skills.

Wheelchair maintenance

Within wheelchair maintenance the responses showed that health professionals are interested in receiving training in wheelchair maintenance and repair. Further, they desire to develop their knowledge regarding how to instruct users and caregivers in this area.

Advanced mobility skills

Under advanced mobility skills, responses expose that health professionals would like to learn how to assess and teach advanced skills for outdoor mobility, with consideration to specialised groups.

All aspects of driving a chair in the community environment - kerbs, ramps, public transport. Overcoming obstacles. Being able to consider the different skills required depending on the type of chair- manual V's power, front, rear, mid-wheel drive.

Community access and outdoor skills including mounting and dismounting kerbs Prescription of attendant propelled wheelchair and how best to approach the training of carers Cognitive assessment for individuals for wheelchair training Techniques to be considered for amputees and wheelchair mobility Understanding to a certain extent of the mechanics of the powered chairs ie actuators, software systems etc where relevant.

Future developments

Comments on how health professionals would like to see wheelchair skills training develop in the future exposed a collective theme summarising the desire for standardised training programs, but additionally revealed some logistical concerns about developing this.

Formal standardized programming

In relation to standardised training programs, professionals stated that standardised training programs should be formal.

I think a formal one-day training session would be really useful so that everyone is teaching the same thing and is up to date with any new safety concerns…

Concerns about development of formal training

Other comments included uncertainty about how to structure training programs as health professionals have observed a great variety of skill levels amongst users with different needs. The consensus among the comments highlighted the importance of standardised programming but acknowledged the difficulty apparent in trying to accommodate the complex issue that users’ skill levels range significantly. Some suggested this may be best served as a specialty service.

I think standardized wheelchair skills training is difficult as every client is different…

Be very goal specific for the client in terms of what is realistic and achievable given their abilities/needs…

A specifically set up training facility in our local department to which we can bring our clients for demo/training. A specific programme to follow depending on type of chair issued.

Discussion

Major findings

This study surveyed members of AOTI and the Irish Posture and Mobility Network and attained the study’s goal of achieving a better understanding of how wheelchair skills training is provided to individuals that access wheelchair services in Ireland. From the responses received in this survey, Irish occupational therapists report that they do provide training in transfers and basic mobility wheelchair skills to wheelchair users of all ages. Training in advanced mobility skills and reported confidence instructing these skills are fiercely lacking in Ireland, which aligns with findings of Best et al. [Citation25] related to the Canadian context, which contributes the Irish perspective of the same deficit.

Most health professionals reported that training is provided to new users through both verbal and written material, however, most trainings are not formal or taught through a standardised program. One formal training program was reported somewhat commonly used in practice to powered mobility users. However, from the responses gained, manual wheelchairs are prescribed more often than powered wheelchairs. This discrepancy further emphasises the need to develop a national guideline for service delivery that aligns with the WHO’s recommendations, as argued by Fung et al. [Citation28] and McSweeney and Gowran [Citation13].

Further, health professionals themselves reported that they would avail of additional training in wheelchair skills if it were provided. Specifically, they seek additional training in advanced mobility skills, which has been identified in previous work as a clinical need internationally [Citation13–16,Citation25].

This survey also asked health professionals to report their confidence when training individuals in wheelchair skills and it was made clear that experience coincided with improved confidence levels. Confidence was reported highest among senior grade professionals in comparison to staff grade. Additionally, health professionals that reported they had obtained additional training in wheelchair skills also reported high confidence instructing the various components of wheelchair skills. These findings establish that additional training in wheelchair skills is sought after. Compounded by the results that training programs have been effective at improving confidence when undertaken, these findings provide rational to continue developing such programs.

Meaning of the findings

This survey provides insight into the clinical practices of wheelchair skills training provided in Ireland. It is promising that Irish health professionals are providing training in basic mobility skills, as they are crucial to learn to improve functional independence as a wheelchair user. Without knowledge of how to perform basic mobility skills, a wheelchair can become a barrier to independent mobility [Citation1] and, in some cases, a potential restraint. Likewise, there are consequential effects on others involved in caregiving. For example, it has been speculated that a lack of self-knowledge can lead to ‘care giver burden’, when a greater reliance is placed on care givers to assist users [Citation29,Citation30]. If relied on, this physical reliance can put caregivers at risk of ill health or injury and often the result of bearing the responsibility of another individual’s care, is that caregivers may neglect themselves. This exposes a snowball effect and additional pressure on health care providers to consider wheelchair skills training as a preventative healthcare approach for users and their families. Caregiver training has been shown to be effective in improving user’s skill capacity and reducing caregiver joint pain by providing physical support more safely [Citation31–33]. The results from this survey suggested that Irish health professionals do provide and are confident in training individuals in transfer skills. Knowledge of strong transfer techniques involving both a user and their care giver, is necessary for the safety of both individuals. The impressive response from most respondents regarding providing instruction in transfer skills may be a result of active adherence to manual handling protocols. Whether the two are linked or otherwise, it is encouraging that rightful importance is placed on these skills as they can impact both users and caregivers.

The lack of training provided in advanced mobility skills and skills needed to perform ADL and IADL represents an unmet need in wheelchair services in Ireland. Knowledge that these skills greatly enhance quality of life and participation in meaningful occupations linked to improved health and wellbeing alongside this study’s finding that health professionals rarely teach these skills and lack confidence instructing these skills, exposes unfavourable consequences for wheelchair users. Therefore, lack of formalised trainings in these necessary skills as part of wheelchair service delivery in Ireland may be contributing to reduced engagement in occupation for wheelchairs users, increased risk of injuries (e.g. pressure injuries) due to limited functional independent mobility, and possible increased risk of fatal accidents associated with unsafe wheelchair use [Citation5–9].

Health professionals were asked how many years they had been using a formal wheelchair skills training program in clinical practice and most respondents reported that this was ‘not applicable’ to their service. While this question may have been misunderstood, these responses suggest that health professionals are unaware of the best practice guidelines outlined by the WHO regarding wheelchair service provision, which recommends that formal training programs be provided to all wheelchair users, despite efforts by multiple organisations to disseminate evidence based open-source material, for example the International Society of Wheelchair Professionals and Wheelchair Skills Program [Citation17–23,Citation34]. Additionally, it may suggest health professionals are unaware of international goals for the development of the wheelchair sector. The two methods reported most used to obtain wheelchair skills training for health professionals were self-directed methods and job shadowing sessions, which are both independently sought after. This may further stress a present demand to provide accessible training opportunities for health professionals working in wheelchair service delivery. These training programs would provide Irish health professionals with the knowledge needed to deliver proven efficacious and effective training in wheelchair skills. Further contributing to the development of a protocol that would help to ensure access to personal mobility for wheelchair users, as it is a human right.

Limitations

These findings supply useful information about clinical practices in wheelchair skills training in Ireland however, we acknowledge that this study has its limitations.

We aimed to capture responses from all professionals involved in wheelchair service delivery in the Irish context, however, responses were limited to occupational therapists and one technical personnel. We chose to use a purposive sampling method, which allowed us to contact health professionals throughout Ireland that carried membership to organisations known to employ professionals in wheelchair service delivery. However, no response rate can be calculated as contact was facilitated through the associations and the number of individuals that received the participation invitation is not known. In a publication by AOTI, they report having more than 1000 members [Citation35]. Census 2016 [Citation36] recorded 643,131 or 13.5% of the Irish population, as having a disability, which cannot be assumed are all physical disabilities. If this percentage is arbitrarily rounded down to 10% and this survey was able to reach roughly 9.6% of occupational therapists that are members of the governing body in Ireland, these researchers defend that the sample obtained is likely representative of professionals known to provide these services to wheelchair users in Ireland.

The first question of the survey was aimed to obtain consent and while 146 respondents selected yes to providing consent, only 91 respondents completed the survey in total. This may have been a result of individuals reconsidering their availability to complete the survey after beginning the survey, difficulty answering questions in the survey or a lack of clarity in the questions. Additionally, this survey collected health professional’s self-reports which increases the risk of either under or over reporting. The responses may have been received by individuals with a pre-existing interest in wheelchair service delivery and therefore cannot be generalised to all settings that offer wheelchair services here in Ireland.

As clinical practice evolves rapidly over time, it is imperative that research results be published in a timely manner. This survey was conducted in 2018, which presents a potential risk that the data presented may be somewhat stale. However, a recent survey investigated Irish service users’ perspectives of wheelchair service delivery and found that over a third of respondents received no training at all related to transfer skills or moving their wheelchair about [Citation37]. While our data was collected in 2018, prior to these findings, similar lasting service delivery issues in Ireland are highlighted.

Suggestions for future research

Future research should address the limitations of this study by incorporating responses from other professionals known to provide wheelchair services, such as physiotherapists or product suppliers. Additionally, this research can be used to inform the development of WST in Ireland. This research provides information about what content should be included and taught to wheelchair users. Likewise, further research should include both professional’s and users’ perspectives. User’s preferences must be considered in establishing these necessary training programs as they are created for the benefit, safety, and improvement of these individuals’ lives.

Clinical relevance

This survey can help wheelchair services in Ireland improve vastly by encouraging university programs to provide wheelchair skills training as part of professional qualification curriculum, and health professionals to continue to seek out training opportunities in wheelchair skills training. This continued drive to obtain additional skills in this area will support the growth of training programs being offered in more regions in the country. There is an unmet need to develop formal training programs in Ireland and train wheelchair service providers to deliver these programs. Delivery of such, on a larger scale, would help improve the implementation of the UNCRPD [Citation2]; legislature that Ireland has already ratified, yet have demonstrated no carry through on, as well as improved overall wheelchair provision in Ireland.

Conclusion

Training beyond safe, basic use of personal wheelchairs is neglected in clinical practice, posing the question of a human rights issue regarding access to independent personal mobility known to improve function. The results from this study highlight that currently health professionals in Ireland lack the skills and confidence needed to provide formal training in advanced mobility skills and desire opportunities to develop these skills. The survey results establish that there is a need to ensure appropriate wheelchair skills training is provided, with the aim of improving Irish health professionals’ knowledge, and to ultimately meet this basic human right for Irish wheelchair users.

appendix.docx

Download MS Word (27.6 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Dr. Krista Best and Dr. Lee Kirby for sharing their work which helped shape this survey. The authors are grateful to Pauline Boland (University of Limerick) for her help with the final adaptations to the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Rousseau-Harrison K, Rochette A, Routhier F, et al. Impact of wheelchair acquisition on social participation. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2009;4(5):344–352.

- Hendricks A. UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Eur J Health L. 2007;14:273.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on the provision of manual wheelchairs in less resourced settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

- World Vision International [Internet]. El Salvador, India, Kenya, Nicaragua, and Romania: USAID, 2012. [cited Sept 2021]. Available from: www.wvi.org.

- Kirby RL, Ackroyd-Stolarz SA, Brown MG, et al. Wheelchair-related accidents caused by tips and falls among noninstitutionalized users of manually propelled wheelchairs in Nova Scotia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73(5):319–330.

- Berg K, Hines M, Allen S. Wheelchair users at home: few home modifications and many injurious falls. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):48.

- Chen WY, Jang Y, Wang JD, et al. Wheelchair-related accidents: relationship with wheelchair-using behavior in active community wheelchair users. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(6):892–898.

- Xiang H, Chany AM, Smith GA. Wheelchair related injuries treated in US emergency departments. Inj Prev. 2006;12(1):8–11.

- Calder CJ, Kirby RL. Fatal wheelchair-related accidents in the United States. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;69(4):184–190.

- Shields M. Use of wheelchairs and other mobility support devices. Health Rep. 2004;15(3):37–41.

- Kilkens OJ, Post MW, Dallmeijer AJ, et al. Relationship between manual wheelchair skill performance and participation of persons with spinal cord injuries 1 year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(3 Suppl 1):65–73.

- Mortenson WB, Miller WC, Backman CL, et al. Predictors of mobility among wheelchair using residents in long-term care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(10):1587–1593.

- McSweeney E, Gowran RJ. Wheelchair service provision education and training in low and lower Middle income countries: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2019;14(1):33–45.

- Fung K, Miller T, Rushton PW, et al. Integration of wheelchair service provision education: current situation, facilitators and barriers for academic rehabilitation programs worldwide. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(5):553–562.

- Smith E, Gowran RJ, Mannan H, et al. Enabling appropriate personnel skill-mix for progressive realization of equitable access to assistive technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(5):445–453.

- Gowran RJ, Bray N, Goldberg M, et al. Understanding the global challenges to accessing appropriate wheelchairs: position paper. IJERPH. 2021;18(7):3338.

- MacPhee AH, Kirby RL, Coolen AL, et al. Wheelchair skills training program: a randomized clinical trial of wheelchair users undergoing initial rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(1):41–50.

- Kirby RL, Miller WC, Routhier F, et al. Effectiveness of a wheelchair skills training program for powered wheelchair users: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(11):2017–2026.

- Oztürk A, Ucsular FD. Effectiveness of a wheelchair skills training programme for community-living users of manual wheelchairs in Turkey: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(5):416–424.

- Hosseini SM, Oyster ML, Kirby RL, et al. Manual wheelchair skills capacity predicts quality of life and community integration in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(12):2237–2243.

- Lemay V, Routhier F, Noreau L, et al. Relationships between wheelchair skills, wheelchair mobility and level of injury in individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(1):37–41.

- Giesbrecht EM, Miller WC. Effect of an mHealth wheelchair skills training program for older adults: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(11):2159–2166.

- Tu CJ, Liu L, Wang W, et al. Effectiveness and safety of wheelchair skills training program in improving the wheelchair skills capacity: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(12):1573–1582.

- Sakakibara BM, Miller WC, Souza M, et al. Wheelchair skills training to improve confidence with using a manual wheelchair among older adults: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(6):1031–1037.

- Best KL, Miller WC, Routhier F. A description of manual wheelchair skills training curriculum in entry-to-practice occupational and physical therapy programs in Canada. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2015;10(5):401–406.

- Pfleeger SL, Kitchenham BA. Principles of survey research: part 1: turning lemons into lemonade. SIGSOFT Softw Eng Notes. 2001;26(6):16–18.

- Kitchenham B, Pfleeger SL. Principles of survey research: part 5: populations and samples. SIGSOFT Softw Eng Notes. 2002;27(5):17–20.

- Toro M, Gartz R, Goldberg M, et al. Wheelchair service provision education in academia. Afr J Disabil. 2017;6(1):1–8.

- Roberts J, Young H, Andrew K, et al. The needs of carers who push wheelchairs. J Integrated Care. 2012;20(1):23–34.

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontology. 1980;20(6):649–655.

- Kirby RL, Smith C, Parker K, et al. Practices and views of occupational therapists in Nova Scotia regarding wheelchair-skills training for clients and their caregivers: an online survey. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(7):773–780.

- Kirby RL, Mifflen NJ, Thibault DL, et al. The manual wheelchair-handling skills of caregivers and the effect of training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(12):2011–2019.

- Piccenna L, Lannin NA, Scott K, et al. Guidance for community-based caregivers in assisting people with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury with transfers and manual handling: evidence and key stakeholder perspectives. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(2):458–465.

- Keeler L, Kirby RL, Parker K, et al. Effectiveness of the Wheelchair Skills Training Program: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2019;14(4):391–409.

- Association of Occupational Therapists Ireland. AOTI Strategy 2017-2022. [Internet]. Ireland; AOTI; 2016. [cited Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.aoti.ie/about-us/Strategy-2017-2022#:∼:text=AOTI%20Strategy%202017%2D2022%20describes,for%20realising%20the%20new%20vision.&text=Strategic%20Intention%201%3A,and%20rewarding%20to%20our%20members.

- Online Archive of Central Statistics Office [Internet]. Ireland: Central Statistics Office. 2016 [cited Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.cso.ie/en/csolatestnews/presspages/2017/census2016profile9-healthdisabilityandcarers/.

- Gowran RJ, Clifford A, Gallagher A, et al. Wheelchair and seating assistive technology provision: a gateway to freedom. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;1–12.DOI:10.1080/09638288.2020.1768303