Abstract

Purpose

This paper considers the possibilities of analysing children’s own designs to contribute to the design of inclusive paediatric mobility interventions. The aim of this paper is threefold: (1) to develop a framework for child-centred design analysis, (2) to analyse children’s designs to explore both quantitative and qualitative insights and (3) to explore how children’s voice could be elevated through design research.

Methods

A Child-centred Design Analysis Framework is developed in an interdisciplinary manner, comprising four dimensions including Child, Content, Context and Format. It is used as a vehicle to analyse and code 130 “Dream Wheelchair” designs by children.

Results

The children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs reference a range of features and priorities, which are gathered into themes through the framework, providing insights into children’s individual and collective mobility narratives, values and requirements. Themes are explored through a qualitative interdisciplinary lens to understand the nature of children’s lived experiences.

Conclusions

The framework promotes child-centred framing through extracting meaning from children’s own designs. It is suggested that child-centred framing and a rights-respecting approach to assistive technology design research can lead to more appropriate design outcomes and improved user experiences for children with disabilities.

The design analysis framework developed and presented in this paper facilitates child-centred framing to elevate children’s voice in a design process.

Analysis of 130 children’s visual and textual designs elicited narratives, values, and requirements around their “Dream Wheelchairs”; these findings contribute insights which can be used for designing inclusive paediatric mobility interventions.

This paper invites industry practitioners and design researchers to use a child-centred and rights-respecting approach when designing with or for children.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILIATION

Introduction

Child-centred design research

Child-centred Design is a design approach which places children and their rights at the core of a design process to elevate their voice [Citation1,Citation2], psychologically and physically empower them [Citation3] and uncover their unmet requirements and desires [Citation4]. During childhood, the “things” [Citation5] around us shape the way we experience and perceive the world [Citation6], influencing our development and fundamentally shaping our whole lives [Citation7]. Designers thus have a great responsibility to carefully consider the way in which they approach “framing” when designing with or for children. Framing [Citation8], also known as “frame creation” [Citation9] or “problem-framing” [Citation10], is the process of understanding which point of view to approach a design from, to ensure the right problem or opportunity is being addressed before focussing on a solution. To achieve child-centred framing, design research or designerly investigations [Citation11] must be undertaken as a sensemaking activity in the early stages of a design process to elicit children’s voice and gain child-centred insights. Children are social actors who have a right to be recognized as experts in their lived experience, and thus design researchers have a duty to pay attention to and represent children and their perceptions in and through design research [Citation12]. Druin [Citation13] and Abbott [Citation14] advocate for involving children in design research as a necessary way to achieve more appropriate and satisfactory child-centred design outcomes with better usability and improved user experiences.

This paper presents a case study in the domain of inclusive paediatric mobility (IPM) design, to explore how involving the voice of young wheelchair users in design research can help designers better understand, frame and meet children’s requirements wishes and dreams. The consequence of designing IPM designs without adopting a child-centred approach has historically resulted in issues with the functionality, usability and desirability of designs, as discussed in detail in section “The imperative transition towards child-centred IPM”. The designerly collaboration described in this case study brings together a range of stakeholders to interpret child-centred insights and elevate children’s voice from a breadth of disciplinary and professional perspectives to collectively inform the framing of IPM design with the ultimate aim of improving children’s overall satisfaction with design outcomes. The following sections introduce interrelated principles, mindsets, practices and techniques [Citation15] for child-centred design research, which facilitate children’s rights and ensure design decisions are informed and steered based on children’s voice and points of view [Citation2].

Principles and mindsets for child-centred design research

Children’s views, knowledge and desires are meaningful, contextual and representative of the individual and collective experiences of a community with cultural and sociological value and human worth [Citation12]. Research with children encourages participation that is inclusive, meaningful and respectful of children’s views in spite of developmental assumptions that pervade children’s day-to-day [Citation16,Citation17]. Yet, such assumptions can continue to impose methodological restrictions tied to age, communication milestones and researchers’ preferences and beliefs, obstructing the active participation and fair representation of children, their viewpoints and cultures [Citation12,Citation18,Citation19]. Approaches such as Co-design, Participatory Design, User-centred Design, Human-centred design and Inclusive Design have well established principles around promoting designerly collaborations and engaging with lived experience experts in research in order to support sensemaking and framing [Citation8]. However, simply engaging with children is not the same as child-centred design, of which there is limited literature beyond the contexts of designing for play [Citation2,Citation4].

Practices and techniques for child-centred design research

Children’s imagination and natural curiosity can be elicited through involvement in practices such as design fiction, co-design, speculative design and critical design [Citation20] to gain insights into their thinking, wishes and imagined futurescapes, which designers can amplify in their design decisions [Citation21]. Methodologies designed specifically for research with children can reduce the hierarchical divide that is inevitably present in adult-child interactions [Citation22]. The scope of such methodologies is to reach a type of dialogic symmetry that is rooted in balancing researchers’ ability to observe and extrapolate meaning and children’s capacity to express ideas, opinions and stories that they value, privilege and convey to appraise their status quo. Engaging in such an ethical and practical endeavour calls for the recognition of children’s preferred forms of communication, an appreciation of their innate and diverse capabilities, as well as their choice of priorities which may be different to the adult designer’s own [Citation23]. Hence, approaches to children’s participation in design research include conventional design research methods such as interviews, observations and creative workshops, in addition to more specialized methods such as role play or creative activities [Citation2,Citation24–26]. However, conventional design research methods that involve questioning and directing children are often less productive than promoting children’s creative autonomy through arts-based methodologies such as drawing [Citation27,Citation28].

Arts-based methodologies extend the hegemonic language and tools of conventional design research to validate self-expression and meaningfully engage with unscripted ideas, leading to explorations of children’s voice that could otherwise remain hidden [Citation29]. Visual, tactile and aesthetic communication plays a central role in engaging with authenticity and minimizing the directional impulse that can prevail in research with children with disabilities [Citation28]. Furthermore, if well planned and executed, such methodologies could allow wider and more inclusive participation with larger scale input from children nationally or internationally by facilitating their input without requiring face-to-face interaction with a researcher [Citation30,Citation31] (as demonstrated by the following case study). When navigating the landscape of child-centred practices and techniques, it is important that designers acknowledge the long-established social imaginaries around the power structures and hierarchies which exist between adults and children [Citation3]. Such hierarchies often lead to children being considered solely as end-users; by overlooking the insightful expertise and views that children possess related to their own experiences, designers could miss out on opportunities to capture or create newly embodied forms of child-centred knowledge [Citation4].

Eliciting meaning and elevating children’s voice

Dimensions of voice

Throughout the design process it is designers who decide whose voice they engage with and include (to what extent, on what topics) to orchestrate whose experiences and perceptions are given weight and echoed in the design outcome. The word “voice” is used metaphorically in this paper to signify opinions and expressions encapsulated by all modes of communication with explicit inclusion of non-verbal mediums [Citation32]. Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) [Citation33] states that children have the right for their voice to be given apt power in all matters affecting them. Furthermore, Article 13 of the CRC [Citation33] states that children have the right to “impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child’s choice.” As explored in section “Eliciting meaning and elevating children’s voice”, there exists a substantial body of literature focussed on engaging with children to capture their voice through such modes of communication [Citation25,Citation27,Citation29,Citation32]. This paper focuses on the stages which follow engagement with children, specifically how meaning can be elicited from such qualitative data in a child-centred manner, and then considers how children’s voice [Citation34] can be amplified, strengthened and elevated through the way in which design research is conducted. Tools and processes for eliciting children’s multifaceted voice through an arts-based methodology are lacking and there is currently no theoretically informed framework or best practice guidelines on how to analyse children’s art or designs in a holistic and rigorous way in order to inform the design process. Capturing and curating different elements of children’s voice through their own designs and for design purposes is one major pathway for child-centred design that requires further theoretical, methodological and empirical investigation.

Child-centred designerly collaborations

The merging of different disciplines is an integral and valuable aspect of child-centred work, in order to draw on the various elements of child-centred expertise offered by different disciplines. Childhood is multifaceted, heterogeneous and complex; differing preferences exist across disciplines around how best to elicit and elevate children’s voice, accompanied by a range of professional and theoretical starting points and methodologies [Citation35,Citation36]. With regards to the nature of disciplinary collaboration, typologies tend to define the terms monodisciplinary as “isolated”, multidisciplinary as “additive”, interdisciplinary as “interactive” and transdisciplinary as “holistic” [Citation37]. Both interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches facilitate the questioning and merging of different disciplinary perspectives, new levels of discourse and blending of knowledge, all of which can provide a more rigorous and exhaustive approach to child-centred design research. In turn, this ensures children’s voices are deeply considered without the distinctions of disciplinary bias, and with reduced chance of misinterpretation. The specialist knowledge and experience of experts from disciplines with a strong child-centred focus can provide a focal point for researchers from other disciplines to ensure the elevation of children’s voice remains a central motivation driving their work.

Research aims

Having reviewed existing practices around the inclusion of children’s voice in research and design, this study focuses on child-centred framing within the specific context of Inclusive Paediatric Mobility (IPM) design. The following three Research Questions (RQ) and corresponding research aims were used to guide this study:

RQ1. How could children’s own designs be analysed to elicit meaning and explore different elements of their voice?

Aim – Develop a child-centred framework for analysing children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs through an interdisciplinary lens.

RQ2. What specifically can be learnt through children’s designs about their individual and collective voice to inform child-centred IPM design?

Aim – Analyse the content and context of children’s designs to elicit both quantitative and qualitative meanings and child-centred insights.

RQ3. How could children’s voice be elevated through design research?

Aim – Reflect on insights from this study and discuss considerations for how child-centred design research could better elevate children’s voice.

Designing for inclusive paediatric mobility

What is inclusive paediatric mobility?

This paper specifically focuses on eliciting children’s voice to help frame the design of Inclusive Paediatric Mobility (IPM) interventions, including assistive technology and rehabilitation devices such as walking aids, exoskeletons and wheelchairs. IPM design refers to the application of an Inclusive Design approach to create mobility interventions for children with disabilities, with the fundamental goal of optimizing the experience of childhood. Inclusive Design is a well-established approach which considers the diversity of people’s physical and psychosocial abilities, paying attention to the voice and lived experiences of people with disabilities to reduce generalization on user stereotypes and design outcomes that cater for them [Citation38].

The multidisciplinary nature of IPM requires various stakeholders’ voices to be captured and considered in an IPM design process. Despite children being capable of formulating their own opinions and views, their voice has historically been overlooked or superficially engaged with by IPM designers [Citation11]. Such apprehension to invest in meaningful engagement with children may have arisen from seemingly challenging assumptions relating to children’s limited communication skills [Citation39], abilities to verbalize complex thoughts [Citation13], or designers’ lack of methods for eliciting meaning from “messy, multi-layered and non-normative character” [Citation40]. As a consequence, children’s voice has typically been diluted in the IPM design agenda, resulting in issues around the functionality, usability and desirability of interventions, which can lead to poor outcomes for the children using them [Citation41]. To further explore and evidence such insights, an illustrative mapping review was conducted to interrogate the past fifty years of designerly contributions to the field of IPM [Citation11]. This uncovered key gaps and opportunities around five interrelated designerly ways including Designerly Investigations; Processes; Contributions; Collaborations; and Contexts. The review evidenced the need for each of these designerly ways to transition in order to achieve more appropriate IPM design outcomes. One key priority identified was the optimization of a child-centred design approach with specific attention to designerly investigations and collaborations. This study aims to advance this research thread by directly exploring a child-centred approach to IPM design.

The imperative transition towards child-centred IPM

To address the aforementioned issues and ensure the future of IPM is built upon a holistically considered and inclusive foundation, clarity around how designers interpret and elevate children’s voice needs to be improved. Involving children throughout the design and development of such health-related interventions has significant benefits [Citation42]. Meaningfully and effectively incorporating children’s voice into the framing of IPM design could improve functionality, usability and desirability of interventions; uncover currently unacknowledged, unstated and unmet narratives, requirements and challenges around children’s mobility; and help imagine critical and speculative IPM futurescapes [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4,Citation43]. To channel such benefits into the field of IPM design, children need to have their perspectives and experiences valued and attributed the same worth as other stakeholders who have the authority to influence design decisions. By collating children’s thoughts, wishes and imagined futurescapes around childhood mobility, child-centred design opportunities can be identified. These can inform the direction and dimensions of future IPM design interventions whilst uncovering the value of including children’s voice in the IPM design process.

The urgency to involve children in the design of IPM interventions stems from the understanding that unless IPM interventions respond to the views and requirements of children, their experience of childhood will be less than optimal and their right to achieve the “fullest possible social integration and individual development” may not be fulfilled [Citation33]. Simply downsizing adult mobility designs to fit children has historically resulted in various issues around the functionality, desirability and feasibility of IPM interventions such as wheelchairs [Citation41]. Whilst some of the technical and objective requirements in IPM design can be addressed through engineering and clinical analyses, subjective requirements necessitate input from children. With this in mind, it becomes imperative to include the voice of children at all relevant stages of the IPM design process, beyond later problem-solving stages and with particular attention to initial framing stages; rather than rushing to solve a problem which has been framed by the designer’s or other stakeholder’s own experiences and perception of the world, the principles of Design Justice [Citation44] call for designers to ensure their design objectives have been framed with or by those the design outcome is intended to be used by.

By establishing a more rigorous child-centred framing process, with specific attention to capturing children’s voice, the existing issues with IPM design can be reframed or even redefined to ultimately improve interventions and reinvent the material-discursive landscape of IPM design. To achieve this, children’s thoughts, wishes and imagined futurescapes around childhood mobility need to be captured in order to identify child-centred design opportunities in the field. A mapping review of IPM design from 1970 to 2020 by O’Sullivan and Nickpour [Citation11] highlights a major gap in both theory and practice around child-centred IPM framing. This multi-layered gap and subsequent opportunity could be best explained on three levels. Firstly, child-centred IPM design approaches are limited and scattered [Citation41]. Secondly, when attempted, these approaches are mainly focussed on problem-solving (engaging children with how to solve the problem) rather than engaging children in framing the problem in the first place [Citation8]. Thirdly, within child-centred framing in design, the focus has been on capturing specific mobility requirements in terms of functionality, usability and desirability, rather than capturing high level child-centred narratives of mobility, its meaning and its value. Furthermore, there is currently no theoretically informed framework or best practice guidelines on how to analyse children's own designs or art-based expressions in a holistic and rigorous way. Capturing and curating different elements of children’s voice through their designs, for design purposes, is one major pathway to child-centred design that requires further theoretical, methodological and empirical investigation. Such theoretical and empirical knowledge could help inform the direction and dimensions of future IPM design interventions and uncover further value of including children’s voice in the IPM design process.

Methodology

The first part of this section details how a dataset of children’s designs was assembled, and the relevance of the embodied information to the aims of this research. The second part of this section addresses research question 1 by detailing the development of a Child-centred Design Analysis Framework, and outlining the methods used to identify and synthesize child-centred insights from various disciplinary and stakeholder perspectives.

Secondary data collection, context and significance

The focus of this study is on eliciting meaning from children’s voice (as qualitative data) rather than physically engaging children in design research. Thus, a qualitative secondary dataset was selected for interrogation and analysis, consisting of IPM designs by 130 children, responding to a design brief set out as “Design your Dream Wheelchair” [Citation45]. The selected secondary dataset was collected by an unaffiliated organization through a national design competition for young wheelchair users from across the United Kingdom. The competition aimed to be inclusive and broad-reaching by promoting flexible entry format options for entrants to either visualize, describe, or have assistance expressing their designs. To enter the competition, participants (or their teacher/guardian) either posted or emailed their design to the organizer. The competition saw “Dream Wheelchair” designs submitted by 130 children aged between four to seventeen years, thus forming the largest and most recent qualitative dataset of IPM designs by children, to align with the research aims set out in this paper. The authors of this paper are responsible for conducting analysis on the dataset but have no connection or involvement with the organizers of the competition, and have no relation to any of the competition entrants. After preliminarily looking through the designs it was decided that the full dataset would be included and represented in the analysis since, despite being a relatively large sample size, the diversity and depth of content meant that information redundancy and data saturation would be unlikely [Citation46].

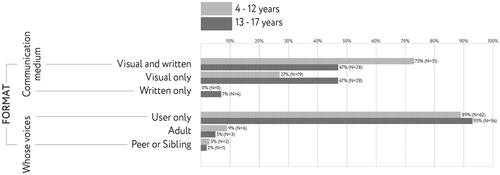

The dataset consisted of a range of formats; of the 130 designs, the most prevalent medium of expression was visual communication, which included drawings, mixed media and photo-collage, presented in both “visual-only” and “visual and written” formats. Prior to analysis, these were verbally described and then transcribed, stating the purpose or appearance of all elements which could be objectively identified (e.g., colours and patterns, design features, setting of design). 61% of children chose to accompany their visual expression with a written description or annotations (either typed or handwritten), whilst 36% produced a “visual-only” entry. 3% of designs were expressed in a “written only” format. All written data, including annotations, were transcribed prior to analysis. Nine of the designs were created with explicit assistance from an adult, and three were created with acknowledged assistance from another child. quantifies the data formats of children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs.

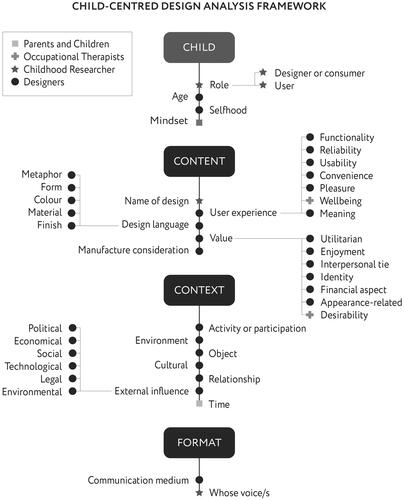

Developing the child-centred design analysis framework

Recognizing the complex nature of inviting and including children’s design input, an interdisciplinary collaboration was established to bring together three researchers with distinct backgrounds covering the IPM design in industry, Children’s rights and disability, and Inclusive Design in academia. The researchers shared core values and interests around inclusive child-centred research, which was instrumental in enhancing the experience, quality and rigour offered by interweaving different lenses throughout the research process. There are two distinct ways to approach the analysis of children’s drawings: one focussing on interpretation and another focussing on content [Citation47]. Whilst various methods exist to facilitate these approaches [Citation30,Citation47], there are no tools or frameworks which facilitate analysis of designs by children with equal attention given to qualitative and quantitative findings in an interdisciplinary manner. To ensure all aspects of the children’s designs could be systematically analysed on multiple levels, an interdisciplinary theoretical framework was devised to provide structure in the analysis process [Citation48], particularly as different values and priorities emerged from the diverse disciplinary perspectives of the team of researchers. After becoming familiar with the dataset, a selection of existing frameworks and theories (outlined in ) were identified as key points of reference across disciplines, and synthesized keeping “theories separate but integrated” [Citation48] to create the underpinnings of a holistic intersecting framework suitable for this purpose.

Table 1. References used to construct the Child-centred Design Analysis Framework.

Refining the child-centred design analysis framework

To improve coding reliability and ensure the framework and resulting analysis insights were not biased by the researcher’s disciplinary perspectives, the perceptions of a range of IPM stakeholders were captured through hosting a two-part workshop with each of them, using a thematic analysis approach [Citation46] to elaborate on and refine the design analysis framework. The participants included two Occupational Therapists, two Designers, one Childhood Researcher, two parents of young wheelchair users. The researchers used their personal networks to recruit participants from each stakeholder group, based on who they believed were the best representatives in terms of experience and interests.

Workshop design

Each workshop lasted approximately 60 min, hosted via video call, with the use of a digital interactive whiteboard to brainstorm, document and record the session. During the first half of the workshop, each stakeholder was asked to review a sample of 14 designs (over 10% of the dataset), making notes or “codes” to describe topics in the designs, before identifying themes, patterns and categories. Seven of the 14 designs were randomly selected from those by children aged 4–12 years, and the other seven were randomly selected from those by children aged 13–17 years. A sample size of more than 14 designs would not have allowed enough time for workshop participants to review the designs in the desired detail, whilst less than 14 would have limited exploration of the diversity of topics and themes contained across the designs [Citation46].

The second half of the workshop consisted of a theme-mapping activity to review and refine the stakeholder’s identified themes and establish connections between them to adapt and refine the framework by expanding or adding nodes and subnodes to it. Words, phrases and examples of visuals were assigned to central nodes or subnodes so that references to these in the data could be coded by the lead researcher correspondingly. At times, the stakeholders’ disciplinary differences in languages and terminology resulted in multiple interpretations of words, requiring blending and integrating to inform a common understanding. For example, the word “comfort” used in one of the design descriptions was interpreted by a designer to mean “cosy” in a pleasurable sense, by a parent to mean “alleviation” in a pain or anxiety management sense, and by an Occupational Therapist to mean “postural support” in a more functional sense. In this case, the multiple interpretations of the word “comfort” were blended into a “Wellbeing” node on the framework, with subnodes referring to “physical comfort” and “psychological comfort”, to capture expressions from all interpretations and to enhance thoroughness and rigour in the analysis.

Conducting the child-centred “dream wheelchair” design analysis

The workshop stimulated in-depth discussion around the children’s designs which helped elicit meaning and qualitative insights from the wider dataset. Refinements to the framework resulting from the workshop included the addition of new nodes, alterations to the order of nodes and subnodes, language or terminology adjustments, and rearrangement of the visual structure of the framework. The refined child-centred design analysis framework () was then translated into a coding structure using NVivo software, to code and analyse topics expressed through the dataset. After 14 of the designs had been coded by the lead researcher, two other researchers reviewed the coded designs to verify the accuracy of the coding. The lead researcher then continued with a content analysis approach to code all 130 of the children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs to quantify insights.

Figure 2. Child-centred design analysis framework.

Results from analysing “dream wheelchair” designs

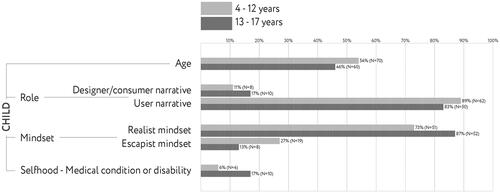

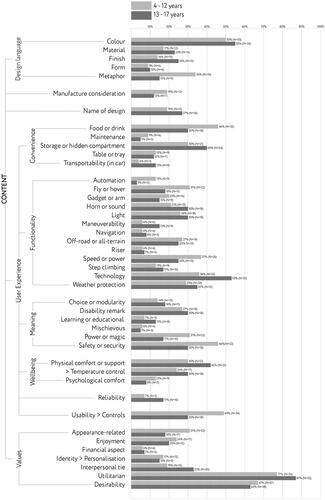

This section responds to research question 2 by uncovering quantitative findings around children’s individual and collective voice. Having analysed and coded the “Dream Wheelchair” designs, present the results by quantifying references to topics from within three spinal segments of the analysis framework, addressing the Child, Content and Context, respectively. An in-depth review of trending topics from this analysis has been conducted in parallel to summarize key insights and further details about the analysis results, as a supplement to this section of the paper [Citation55].

Figure 3. “Dream wheelchair” design analysis results – child.

Figure 4. “Dream wheelchair” design analysis results – content.

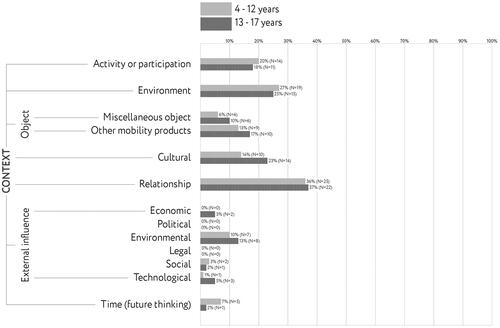

Figure 5. “Dream wheelchair” design analysis results – context.

“Child” analysis results

Based on the available data, age was the only variable provided with all of the designs, and also appeared to be the most notable cause for variations across the expressed topics. Age has thus been used to divide the results for comparative analysis through each segment of the framework, by splitting the results into designs by 4–12 year olds (n = 70), and designs by 13–17 year olds (n = 60), to expose topics which vary between the two age groups. quantifies information about the children and their approach to the design task, elicited through analysing their “Dream Wheelchair” designs.

“Content” Analysis results

The most referenced topic uncovered by the analysis was “Utilitarian” aspects of their designs, mentioned by 82% of all children. This encompassed a broad range of more specific sublevel topics, which were also captured largely within the user experience section of the framework. The next most referenced topic was Colour, with overall 52% of children annotating or describing certain colours as a noteworthy feature of their design. Other highly trending topics included Technology (Functionality), Controls (Usability), Safety or Security (Meaning), Food or Drink (Convenience), Physical Comfort (Wellbeing), Storage or Hidden Compartment (Convenience), Weather protection (Functionality) and Speed or Power (Functionality). quantifies findings from the content of children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs.

“Context” Analysis results

The Context segment of the framework revealed that children’s interactions with the people, objects and places around them are of great importance and influence in their “Dream Wheelchair” designs. The most referenced topic in this segment, mentioned by 36% of children, was “Relationship”, encompassing human and non-human companions with whom the designer/user interacts. Designs commonly relate to participating in activities with others, functions which make their wheelchair serve others as well as the principal user/designer, with explicit references to the ways they interact with or relate to others. quantifies findings relating to the context of children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs.

Child-centred insights and considerations

Grounded by the analysis results and wider relevant literature, the following discussion addresses research questions 2 and 3 by highlighting important insights and considerations relating to child-centred design research, whilst also acknowledging the distinct disciplinary and intersecting viewpoints within the research team. The section titled “Insights and meaning elicited from children’s voice” specifically focuses on qualitative insights and meaning elicited from children’s voice (RQ2) which could inform child-centred IPM design, whilst the section titled “Considerations for elevating children’s voice through design research” focuses on considerations for elevating children’s voice through design research (RQ3).

Insights and meaning elicited from children’s voice

Incremental versus radical innovation

The level of innovation present in children’s designs varies significantly. Incremental innovations seem to result from a focus on improving experience and desirability, are seemingly informed by lived experience, and appear to have been approached with a realist mindset. In contrast, the more radical innovations focus on re-imagining what the entire wheelchair concept entails and enables, drawing on fantasy and fictional worlds to redefine what is possible. Such designs appear to have been approached with an abundance of imagination and an “escapist mindset”, featuring marvellous superpowers and magical features, with less consideration given to reality. The majority of children from both age groups seem to have approached this design task with the former realist mindset, by accepting and adhering to social imaginaries of what a wheelchair is, and focussing solely on incremental improvements to existing wheelchair designs.

Technologically-enabled or “techno-ableist”?

Many of the children’s designs were saturated with tech-heavy features to facilitate inclusion and access to the world around them, granting autonomy and abilities equal or superior to able-bodied peers. A dominant underlying narrative reflected in these design choices, placed technologies as the solution to addressing disability, implying that disabilities can be improved with these features. This could be interpreted as a form of internalized ableism, or “Technoableism” as Shew [Citation56] explains, “dreams of passing, of ‘normalcy’, and ideas about inspiration and overcoming, frame many of the disability community’s internal conversations about disability technologies''. Conversely, a significant portion of the adult disability community advocate for accessible infrastructure and policies over individual design solutions, with the mindset that attention given to specific product fixes or “Disability Dongles” [Citation57] is attention diverted from standardizing the incorporation of accessibility into environments. The high proportion of children across both age groups who dream of wheelchairs which can climb steps, fly or hover, and have various magical powers, reflects a chasm between children and adults’ thinking, which could signify their level of awareness around disability models or constraints of reality (such as affordability and accessibility), or it could simply reflect their sources of inspiration.

Spectrum of requirements and desires

Many of the children’s designs represent a desire for their “Dream Wheelchair” to provide or facilitate the most basic of needs, indicating that their existing wheelchairs may not. This is highlighted by arranging the topics they expressed to fit within the five tiers depicted in Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” theory [Citation58]. Reoccurring examples of unmet “Basic Needs” () included access to warmth, food and drink, and physical comfort to prevent or manage pain. “Safety or security” features were included in 38% of the designs, ranging from personal alarms and emergency panic buttons to anti-tip and crash-prevention features. This signifies a level of apprehension and awareness of potential dangers; which children evidently wish to mitigate. Beyond these most basic needs, children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs also include an awareness of their “Psychological Needs”, covering topics such as family, interaction, friendships, participation in social activities, independence, freedom and self-confidence. Within this tier, children placed emphasis on the desirability of their wheelchair, both seeking respect from others as well as appealing to their own personal styles and often bold visual preferences. “Self-fulfilment Needs” was the least populated tier amongst children’s designs, involving features to facilitate learning, development, achieving goals and pursuing grand adventures. It could be argued that beyond the tier of self-fulfilment sits a zone of transcendence, in which the child shifts their focus to beyond their own needs.

Figure 6. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [Citation58].

![Figure 6. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [Citation58].](/cms/asset/5b130706-cf77-4a81-9602-6e7b150ab596/iidt_a_2071487_f0006_b.jpg)

A spotlight on altruism

Many children make explicit reference to the value of companionship through designing considerate accessories or features to be used by, or engage with, others in ways that existing wheelchairs do not. Whether referring to a parent, carer or friend, this type of altruism-by-design produces important considerations around children’s desire to explore their social role beyond the functional aspects of mobility, signalling their concern for the wellness of others and the participation of adults and children “at their side”, in ways that dismantle a rhetoric of need and dependency. This highlights altruism as both a value and design function capable of increasing the potential of a wheelchair from improving mobility experiences to facilitating child-initiated socialization, through empowering other (potentially able-bodied) people. Examples include a dedicated tea-making facility “for mum”, a passenger seat “to travel together”, a platform “so they can keep up”, and a toy machine “so I can give toys to all the children that I see”. By seeking to include others through these design features, it is possible to see that the children are considering different ways to induce equality and shared participation in their wheelchair experience.

Uncovering mobility narratives versus capturing design specifications

The richness, diversity, and level of granularity of the drawings and texts enable different levels of data analysis with two distinct potential outcomes. On one level, children’s “Dream Wheelchair” designs can help capture specific user requirements and product features, informing the design of paediatric wheelchairs through collecting URS (User Requirements Specifications) and PDS (Product Design Specifications). In this capacity, the study is aimed at “problem solving”, and recognized as a “Research For Design” activity. On the other level, the designs help uncover children”s high-level narratives, social imaginaries, and meanings around childhood, mobility, and disability. Instead of interpreting children’s input literally, based heavily on the feasibility of solutions, their designs can be unpicked, analysed and utilized to identify what is missing from the current state of IPM design according to their distilled perspectives and narratives [Citation21]. In this capacity, the study is aimed at “problem framing”, recognized distinctively as a “Research Through Design” activity to illuminate a range of child-centred IPM frames beyond the default frame of “a way to move around”.

Considerations for elevating children’s voice through design research

Problem framing over problem solving

One key and recurrent issue in design exercises of this nature is a lack of clarity from the outset regarding the intended outcome of the activity, distinguishing between “problem framing” and “problem solving” [Citation10]. Unconstrained imagination and creativity result in some aspects of the children’s design ideas not conforming to certain existing manufacturability constraints. We argue that the viability and feasibility of children’s designs (or dreams) should not be judged according to industry capabilities. For example, the concept of a flying wheelchair does not seem viable as a solution, but when unpicking children’s expressions, it becomes apparent that these designs mostly refer to using a fly or hover function to specifically overcome steps or rough terrain, clearly highlighting and framing a critical socio-environmental problem. Rather than viewing this as a downfall to using such speculative design approaches with children, these instances should be considered as opportunities to view children’s design input as narratives for “problem framing” rather than for “problem solving”. By proactively acknowledging and capturing the ordinarily marginalized narratives of children in this way, designers can ensure a child-centred approach is taken when negotiating which stakeholder narratives to embed and scale through their design [Citation59]. This process will inevitably involve balancing tensions between form, function and fashion required to incorporate child-centred insights without compromising essential functional requirements.

Whose voice is it?

Children are lived experience experts in their own mobility; their perceptions, opinions and ideas around their mobility thus infer significant value to the IPM design process. The inclusion of children who cannot express themselves without support requires facilitating and capturing their voice in a way that respects subjectivity, avoiding others’ voices becoming entangled in the process. Designs which were heavily assisted by adults were typically accompanied by third person narrative, using the adult’s choice of language rather than using the child’s own ways of expressing and representing their views. There are certainly areas of the IPM design process where different stakeholder voices are indispensable, however, to optimize the child-centred approach it is important for assisting adults or able-bodied peers to remain aware of their possible influences and to ensure their role is that of a facilitator and not of co-designer.

Communication mediums

Visual dialogue and an aesthetic language can support the bridging between self-expression and meaningful participation that is not solely reliant on verbal capability and verbal construction [Citation14,Citation60]. It is legitimate to propose that many of the children’s ideas may not have come to life through verbal responses to (verbal) questioning. It could be argued that the use of visualization and drawing, aided in some cases by annotation and labelling, engaged and validated children’s experimental audacity in ways that language alone would have inherently hindered. Drawings are affected by knowledge, age and the ability to draw but offer children a powerful way of visually manifesting thoughts to explore desires, values, meanings and priorities that may be difficult to narrate through other mediums. The thoughtfulness and considered characteristics of each design would suggest that the children involved were resourceful in utilizing their creative capital, making bold experiments and “requests” in the shaping and representing of their “Dream Wheelchair” and its function, whether realistic, realizable, or fantastic.

Children as masked collaborators in design research

This research reveals that when designers engage with children’s voice through secondary data, they are able to avoid influencing or steering children’s ideas and priorities. In a similar way to narrative interviewing, this gives children full control over the activity meaning they are influenced as little as possible by others. A clear advantage to engaging with children’s voice in this secondary manner is the ability to obtain and work remotely with a large-scale dataset, for minimal cost and time, by essentially leapfrogging the data collection phase. A limitation to this method was that the dataset was provided to the research team in a fully anonymised format, which made the study simpler in terms of ethical approval but meant there was no way to gain any additional information about the children who had created the designs, nor ask them to confirm if the researchers’ interpretations and analysis of their designs were accurate. Despite offering an efficient way to gather large scale design input from children, deeper insights could be uncovered by the researchers being able to collect further specific information about each child-designer to get to know them better in connection to their context. Such additional insights, gained through meeting the children may have enabled a deeper analysis or identification of noteworthy contextual variables in their designs (beyond age); for example: geographic location (rural or urban environment), gender identity and cultural or lifestyle choices. It could be worthwhile using research triangulation to test the analysis results to test any assumptions or interpretations made by the researchers.

The powers and perils of a design brief

Deciding on the scope of a design project or competition is a critical ethical decision which channels attention towards one particular area [Citation44]. Language choice, wording and clarity of communication in a design brief is thus very important. Using the word “wheelchair” entwines the topics of disability, childhood, and mobility into the same thread as children’s underlying assumptions and social imaginaries around what a wheelchair is, at the same time as reinforcing the idea that the wheelchair is the object which requires design attention rather than the focus being on the child and their surrounding environment. Using the word “wheelchair” in the competition title intentionally influenced and constrained the scope of entries to focus solely on wheelchairs as opposed to considering alternative or imagined forms of mobility and access, whilst excluding children with mobility impairments who at that time used equipment other than wheelchairs, such as walking aids, prosthetics and exoskeletons.

Conclusions and future research

This paper promotes a child-centred approach to framing using children’s designs. It provides industry practitioners and design researchers with the methodology and tools necessary to conduct a child-centred design analysis, and presents a range of quantitative and qualitative insights pertinent to the design of inclusive paediatric mobility interventions. Aimed at eliciting and elevating children’s voice, this paper makes three core design contributions:

Firstly, on a theoretical level, a child-centred framework for analysing children’s designs through an interdisciplinary lens is developed. The framework could be applied in various contexts and domains, both closely related and more distant from IPM, in order to thoroughly analyse children’s designs and help elicit meaning. For example, a similar dream wheelchair design activity could be conducted with children in a contrasting context to the UK, and the trending topics and insights revealed through analysis could be compared with those in this paper to highlight possible contextual influences on child-centred design.

Secondly, on an empirical level, quantitative and qualitative insights are uncovered through analysing 130 “Dream Wheelchair” designs. The analysis explored individual (Sections “‘Child’ analysis results”, “‘Content’ analysis results” and “‘Context’ analysis results”) and collective (“Insights and meaning elicited from children’s voice”) meanings from children’s voice including insights around the topics of incremental versus radical innovation, technologically-enabled or “techno-ableist”, spectrum of requirements and desires, a spotlight on altruism, and uncovering mobility narratives versus capturing design specifications. These insights illuminate alternative child-centred frames and imagined futurescapes which move beyond the default IPM frame of “a way to move around”. These could be implemented by IPM practitioners and researchers to steer future strategy, and design and develop IPM interventions to achieve more appropriate child-centred outcomes.

Thirdly, on a reflective level, the study is reflected on to explore how children’s voice could be elevated through design research (“Considerations for elevating children’s voice through design research”), putting forward key considerations around the topics of: problem framing over problem solving, whose voice is it, communication mediums, children as masked collaborators in design research, and the powers and perils of a design brief.

Future research should explore how the new framework and insights from this study can be used to inform child-centred product design and improve outcomes for children with disabilities. Moving forward, the question of how children’s voice – particularly their higher-level narratives – should be translated into technical design specifications, needs to be further explored. This could play a central role in streamlining the incorporation of child-centred insights into design interventions. It is hoped that furthering this research thread will produce more viable design practices, informed by a holistic approach to socially just participation that elevates the voice of children with disabilities and responds to their ideas and dreams

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Wheels of Change project and the PPL Dream Fund initiative for sharing the secondary data used in this study, and acknowledge the Hugh Greenwood Fund for Children’s Health Research for supporting the study conduct.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Can E, İnalhan G. Having a voice, having a choice: children’s participation in educational space design. Design J. 2017;20(sup1):S3238–S3251.

- Feder K. Exploring a child-centred design approach [PhD Thesis]. Denmark: Designskolen Kolding. Kolding; 2019.

- Vasalou A, Ibrahim S, Clarke M, et al. On power and participation: reflections from design with developmentally diverse children. Int J Child-Comput Interact. 2021;27:100241.

- Yamada-rice D. Including children in the design of the internet of toys. In: Mascheroni G, Holloway D, editors. The internet of toys. Studies in childhood and youth. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2019.

- Brown B. Thing theory. Critical Inquiry. 2001;28(1):1–22.

- Giaccardi E. Things as Co-ethnographers: implications of a thing perspective for design and anthropology. In: Speed C, Cila N, Caldwell ML, editors. Design anthropological futures. Milton Park: Routledge; 2016. p. 14.

- Kolb B. 2021. Brain development during early childhood. In: Hupp S. and Jewell J., editors. The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- McDonnell J. Design roulette: a close examination of collaborative decision-making in design from the perspective of framing. Design Studies. 2018;57:75–92.

- Dorst K. Frame creation and design in the expanded field. She Ji: J Design Eco Innovat. 2015;1(1):22–23.

- Silk EM, Rechkemmer AE, Daly SR, et al. Problem framing and cognitive style: impacts on design ideation perceptions. Design Studies. 2021;74:101015.

- Shaw C, Nickpour F. A framework for transitioning designerly ways; interrogating 50 years of inclusive design for paediatric mobility. Design J. 2021;24(6):977–999.

- Bernardi F. Reclaiming childhood. disrupting discourses of identity, autonomy and dis/ability, adopting arts-based methods, Gramsci and Bourdieu: a cross-cultural study in Central Italy and North West England [PhD Thesis]. Edge Hill University; 2019.

- Druin A. The role of children in the design of new technology. Behav Inf Technol. 2010;3(1):17–22.

- Abbott D. Who says what, where, why and how? Doing real-world research with disabled children, young people and family members. In: Curran T, Runswick-Cole K, editors. Disabled children’s childhood studies. Critical approaches in a global context. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013. p. 39–56.

- Carlgren L, Rauth I, Elmquist M. Framing design thinking: the concept in idea and enactment. Creat Innov Manag. 2016;25(1):38–57.

- Hart R. Children’s participation: from tokenism to citizenship. Florence: International Child Development Centre/UNICEF; 1992.

- Thomas N. Turning the tables: children as researchers. In: Christensen P, James A, editors. Research with children. Perspectives and practices. 3rd ed. Abingdon: Routledge; 2017. p. 160–179.

- Wickenden M, Kembhavi-tam G. Ask us too! doing participatory research with disabled children in the global South. Childhood. 2014;21(3):400–417.

- Corsaro W. The sociology of childhood. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc; 2018.

- Yavuz S, Bonetti R, Cohen N. Designing the “next” smart objects together with children. Design J. 2017;20(sup1):S3789–S3800.

- Jones N. Narrative inquiry in human-centered design: examining silence and voice to promote social justice in design scenarios. J Tech Writ Commun. 2016;46(4):471–492.

- Yip JC, Sobel K, Pitt C. Examining adult-child interactions in intergenerational participatory design. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, 2017. p. 5742–5754.

- Clark A. Listening to young children, expanded third edition: a guide to understanding and using the mosaic approach. 3rd ed. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2017.

- Kelly SR, Mazzone E, Horton M, et al. Bluebells: a design method for child-centred product development In Proceedings of the 4th Nordic conference on human-computer interaction: changing roles Association for Computing Machinery, New York, 2006. p. 361–368.

- Hagen E, Sm R, Hiseth M, et al. Co-designing with children: collecting and structuring methods. 9th NordDesign conference; 2012.

- Süner S. Elicitation, prioritisation, observation: a research model to inform the early design phases with child-centred perspectives Ph.D Thesis, Doctoral Program, Middle East Technical University, 2018.

- Blumenfeld-Jones D. Wild imagination, radical imagination, politics, and the practice of arts-based educational research (ABER) and scholartistry. In: Cahnmann-taylor M, Siegesmund G, editors. Arts-Based research in education (inquiry and pedagogy across diverse contexts). New York: Routledge; 2018. p. 48–66.

- Bernardi F. Autonomy, spontaneity and creativity in research with children: a study of experience and participation, in Central Italy and North West England. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2020;23(1):55–74.

- Eldén S. Inviting the messy: drawing methods and ‘children’s voices. Childhood. 2013;20(1):66–81.

- Merriman B, Guerin S. Using children’s drawings as data in child-centred research. Irish J Psychol. 2006;27(1–2):48–57.

- Nygren MO, Nouwen M, Van Even P, et al. Developing ideas and methods for supporting whole body interaction in remote Co-design with children. In interaction design and children. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 675–678.

- Ibrahim S, Vasalou A, Benton A, et al. A methodological reflection on investigating children’s voice in qualitative research involving children with severe speech and physical impairments. Disabil Soci. 2022;37(1):63–88.

- United Nations. Convention on The Rights of The Child, E/CN.4/RES/1990/74, UN Commission on Human Rights; 1990.

- Stern J. Children’s voice or children’s voices? How educational research can be at the heart of schooling. forum. 2015;57(1):75–90.

- Lambert V, Glacken M, McCarron M. Using a range of methods to access children’s voices. J Res Nurs. 2013;18(7):601–616.

- Bloom A, Critten S, Johnson H, et al. A critical review of methods for eliciting voice from children with speech, language and communication needs. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2020;20(4):308–320.

- Chen JM, Luetz JM, et al. Mono-/inter-/multi-/trans-/anti-disciplinarity in Research. In: Leal Filho W. editor. Quality education, encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals. Cham: Springer; 2020.

- Luck R. Inclusive design and making in practice: bringing bodily experience into closer contact with making. Design Stud. 2018;54:96–119.

- Gray C, Winter E. Hearing voices: participatory research with preschool children with and without disabilities. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. 2011;19(3):309–320.

- Spyrou S. The limits of children’s voices: from authenticity to critical, reflexive representation. Childhood. 2011;18(2):151–165.

- Feldner HA, Logan SW, Galloway JC. Why the time is right for a radical paradigm shift in early powered mobility: the role of powered mobility technology devices, policy and stakeholders. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;11(2):89–102.

- Allsop M, Holt R, Levesley M, et al. The engagement of children with disabilities in health-related technology design processes: identifying methodology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2010;5(1):1–13.

- Allsop M, Gallagher J, Holt R, et al. Involving children in the development of assistive technology devices. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2011;6(2):148–156.

- Costanza-Chock S. [Internet]. Design justice. Design narratives: from TXTMob to Twitter; [cited 2020 Dec 14]. Available from: https://design-justice.pubpub.org/pub/0v6035ye/release/1.

- Whizzkids [Internet]. #DreamWheelchair Competition; What would the wheelchair of your dreams be like? [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.whizz-kidz.org.uk/discover/post/hannah-bishop-from-horsham-wins-first-prize-in-dreamwheelchair-competition.

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201–216.

- Farokhi M, Hashemi M. The analysis of children’s drawings: social, emotional, physical, and psychological aspects. Procedia – Soc Behavi Sci. 2011;30:2219–2224.

- Cohenmiller A, Pate E. A model for developing interdisciplinary research theoretical frameworks. Qual Rep. 2019;24(6):1211–1226.

- Barroqueiro DR. Art in early childhood: an examination of form, content and social context. International art in early. Childhood Res J. 2010;2(1):1–16.

- Richins ML. Valuing things: the public and private meanings of possessions. J Consum Res. 1994;21(3):504–521.

- Walter A. Hierarchy of user needs: designing for emotion, A Book Apart, First Ed; 2011.

- Becerra L. CMF design: the fundamental principles of colour, material and finish design. Netherlands: Frame Publishers; 2016.

- Robinson RE. [Internet]. Building a useful research tool: an origin story of AEIOU; [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.epicpeople.org/building-a-useful-research-tool/.

- What is a PESTEL analysis? [Internet]. Oxford college of marketing; [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://blog.oxfordcollegeofmarketing.com/2016/06/30/pestel-analysis/.

- O’Sullivan C, Nickpour F, Bernardi F. What can be learnt from 130 children’s dream wheelchair designs? Eliciting child-centred insights using an interdisciplinary design analysis framework in Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design; 2021.

- Shew A. Ableism, technoableism, and future AI. IEEE Technol Soc Mag. 2020;39(1):40–85.

- Jackson L. [Internet]. A community response to a #DisabilityDongle; [cited 2020 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/spark/disabled-people-want-disability-design-not-disability-dongles-1.5353131.

- Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50(4):370–396.

- Shaw C, Nickpour F. Design as an agent of narratives: a conceptual framework and a first exploration in the context of inclusive paediatric mobility design, DRS International Conference 2022.

- Bradbury-Jones C, Isham L, Taylor J. The complexities and contradictions in participatory research with vulnerable children and young people: a qualitative systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2018;215:80–91.