Abstract

Background

Implementation of an eRehabilitation intervention named Fit After Stroke @Home (Fast@home) – including cognitive/physical exercise applications, activity-tracking, psycho-education – after stroke resulted in health-related improvements. This study investigated what worked and why in the implementation.

Methods

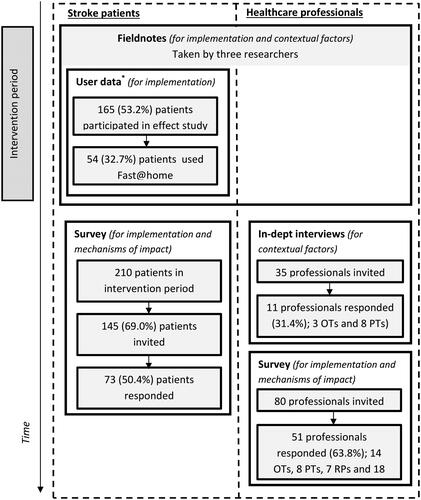

Implementation activities (information provision, integration of Fast@home, instruction and motivation) were performed for 14 months and evaluated, using the Medical Research Council framework for process evaluations which consists of three evaluation domains (implementation, mechanisms of impact and contextual factors). Implementation activities were evaluated by field notes/surveys/user data, it’s mechanisms of impact by surveys and contextual factors by field notes/interviews among 11 professionals. Surveys were conducted among 51 professionals and 73 patients. User data (n = 165 patients) were extracted from the eRehabilitation applications.

Results

Implementation activities were executed as planned. Of the professionals trained to deliver the intervention (33 of 51), 25 (75.8%) delivered it. Of the 165 patients, 82 (49.7%) were registered for Fast@home, with 54 patient (65.8%) using it. Mechanisms of impact showed that professionals and patients were equally satisfied with implementation activities (median score 7.0 [IQR 6.0–7.75] versus 7.0 [6.0–7.5]), but patients were more satisfied with the intervention (8.0 [IQR 7.0–8.0] versus 5.5 [4.0–7.0]). Guidance by professionals was seen as most impactful for implementation by patients and support of clinical champions and time given for training by professionals. Professionals rated the integration of Fast@home as insufficient. Contextual factors (financial cutbacks and technical setbacks) hampered the implementation.

Conclusion

Main improvements of the implementation of eRehabilitation are related to professionals’ perceptions of the intervention, integration of eRehabilitation and contextual factors.

To increase the use of eRehabilitation by patients, patients should be supported by their healthcare professional in their first time use and during the rehabilitation process.

To increase the use of eRehabilitation by healthcare professionals, healthcare professionals should be (1) supported by a clinical champion and (2) provided with sufficient time for learning to work and getting familiar with the eRehabilitation program.

Integration of eRehabilitation in conventional stroke rehabilitation (optimal blended care) is an important challenge and a prerequisite for the implementation of eRehabilitation in the clinical setting.

Implication for rehabilitation

Introduction

Over the last decades, the availability and quality of digital health technology in rehabilitation (eRehabilitation) has increased [Citation1,Citation2]. eRehabilitation may include various modalities such as online physical or cognitive exercise programs, serious gaming, education or e-consultations [Citation3–6] and has the potential to improve the quality and frequency of rehabilitation therapy [Citation7,Citation8]. A major target population of eRehabilitation are stroke patients in medical specialist rehabilitation. As the incidence of stroke and survival rates increase in our ageing society [Citation9], eRehabilitation may provide a solution for the growing demand for stroke rehabilitation and healthcare-related costs. Recent systematic reviews concluded that eRehabilitation after stroke might lead to better health-related outcomes [Citation10–12], improved access to care [Citation4], reduced healthcare costs [Citation8] and improved self-management of patients [Citation13]. However, it is hard to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of stroke eRehabilitation in general, since the characteristics of interventions and outcome measures varied greatly across studies and most studies were not adequately powered [Citation8].

Despite great implementation efforts, usage of eRehabilitation by patients and healthcare professionals in clinical practice is generally limited [Citation14]. This finding highlights the need for comprehensive evaluations that provide insight into why the implementation of eRehabilitation interventions work or fail and in particular how implementation strategies can be improved [Citation15]. To structure the comprehensive evaluations of implementation of interventions, the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework is frequently used [Citation16]. The MRC framework includes three domains of evaluation, namely implementation, mechanisms of impact, and contextual factors. The combination of the results of the evaluation of these three domains and the interactions between them make it possible to better interpret the effectiveness of studies in the clinical practise and may contribute to the evidence for the design and execution of implementation projects in everyday routines [Citation17].

To our knowledge, only one process evaluation is published in the field of eRehabilitation after stroke. That study was performed in Uganda, and concerned a mobile phone-supported rehabilitation intervention [Citation18]. Terio et al. investigated the user experiences and contextual factors influencing the implementation. It was concluded that the implementation strategy was partially delivered as planned and that barriers including technical setbacks and facilitators including motivated participants influenced the implementation. However, that study did not follow the MRC guidelines [Citation19], and did not describe details of the implementation strategy nor evaluated the mechanisms through which the intervention and implementation strategy might have worked.

Recently, an observational effect study evaluated the effect of an eRehabilitation intervention, which was integrated into medical specialist stroke rehabilitation (Fit After Stroke @Home, Fast@Home, Box 1) [Citation20]. This effect study showed greater improvement on the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) domains communication, memory, meaningful activities and physical strength three to six months after admission for those who received conventional rehabilitation including Fast@home (intervention period), compared to those who received only conventional rehabilitation (control period).

Box 1. The Fast@home intervention and effect study.

Intervention:

Fast@home is a web-based eRehabilitation intervention developed to support stroke patients and healthcare professionals during inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation and after discharge. Patients are instructed to use Fast@home five times a week for 30 min, for 16 weeks.

Fast@home consisted of the following already existing (commercially available) eRehabilitation applications:

physical exercise program, offered by Telerevalidatie (Roessingh Research & Development, Enschede, the Netherlands, www.telerevalidatie.nl, used in Basalt Leiden) or Physitrack (Physitrack Ltd, London, UK, www.physitrack.com, used in Basalt Den Haag). Exercises for all parts of the body were available and aimed to improve strength, balance, coordination, mobility, stability, speech or aerobic capacity. The exercises were explained by videos within the physical exercise programme. A tailored day-to-day schedule for each participating patient could be compiled by the treating physical and/or occupational therapist including a selection of one or more exercises.

cognitive exercise program named Braingymmer (Dezzel Media, Almere, Netherlands). Every day, each patient could perform three exercises of 300 s, on the domains concentration, logic, perception, memory and velocity.

physical activity-tracker (Activ8 consumer, 2M Engineering, Valkenswaard, the Netherlands, www.activ8all.com). This tracker was worn inside a pocket of jeans and measured the time spent on laying, sitting, standing, walking, cycling or running, in min. Data could be uploaded with a personal login and viewed in the dashboard of Fast@home.

psycho-education. This psycho-education was based on the information given by the Dutch patient association (www.hersenstichting.nl) and included information about stroke, consequences of stroke and stories of other patients and informal caregiver. Pictograms were used to increase ease of use and understanding.

Each patient was offered access to the psycho-education. For the patients who would benefit from it, other applications were offered. In this, healthcare professionals compiled an exercise program tailored to each patient personal goals and monitored the results and adherence of the patients. Fast@home is a web-based intervention and can be used on each smartphone, laptop, pc or tablet. Professionals where provided with objective data including time of use in each application, number of attempted and successful repetitions, in order to better support the patient and/or adapt the programme if required.

Effect study:

Aim: Compare the effects of Fast@home offered alongside conventional stroke rehabilitation, with conventional stroke rehabilitation.

Design: Number of attempted: Pre-test post-test comparison in two rehabilitation centres in the Netherlands (Basalt The Hague and Leiden), with 12 months control period and 12 months intervention period, with both inpatient and outpatient.

Methods: Questionnaires at admission (T0), three months (T3) and six months (T6) after admission, and administration of the use of the intervention by the application developers. Primary outcome was the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS), secondary outcomes were health-related quality of life, measured with the EuroQoL-5D (EQ5D) and the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12); fatigue, measured with the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS); Self-management measured with The Patient Activation Measure Shorted form 13 (PAM-13) and participation measured with the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation (USER-P) and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF)

Outcome: effect Fast@home: 54 of the 165 patients in the intervention period used the intervention. A positive significant effect was found between three and six months in the SIS domains Communication, Memory, Hand function, Physical Strength and Meaningful activities. Users of eRehabilitation showed a trend towards greater improvements compared to the whole intervention group including those who did not use eRehabilitation. However, Fast@home did not result in any clinically relevant difference or effect over the entire six-month period.

The aim of the current process evaluation was to understand what worked and why in the implementation of the Fast@home intervention and to identify areas for improvement in future implementations. This was done with the guidance of the MRC framework by (1) describing and evaluating the implementation activities (dose, fidelity, adaptations, reach); (2) exploring mechanisms of impact (patients and healthcare professionals responses and interaction with the intervention and implementation strategy) and (3) identifying contextual factors that influenced the implementation of the eRehabilitation intervention.

Method

Context

The Fast@home intervention was implemented at two locations of a specialized rehabilitation facility in the Netherlands (Basalt The Hague and Basalt Leiden). In the Netherlands, approximately 10% of the stroke patients receive inpatient and/or outpatient rehabilitation treatment. Rehabilitation treatment is provided in accordance to a national guideline [Citation21], delivered by a multidisciplinary team including a rehabilitation physician (RP), physical therapist (PT), occupational therapist (OT), speech therapist, psychologist and social worker. Stroke rehabilitation generally focuses on improving motor, cognitive or psychological function, speech and/or daily activities and participation. The average duration of treatment varies, from 44 days for inpatient rehabilitation, to 119 days for outpatient rehabilitation [Citation22].

Research design

In this mixed methods study, the MRC guidelines for process evaluation of complex interventions were followed [Citation19] consisting of following three domains ():

Figure 1. MRC framework for evaluations of the implementation processes. Reproduced from Ref. [Citation16] and not adapted (CC BY 4.0).

![Figure 1. MRC framework for evaluations of the implementation processes. Reproduced from Ref. [Citation16] and not adapted (CC BY 4.0).](/cms/asset/0ccc4597-3a79-4a43-8909-3c44dd7afdc2/iidt_a_2088867_f0001_c.jpg)

The implementation domain explores which elements of the implementation strategy are actually delivered (dose), how the delivery is achieved (fidelity and adaptations) and whether the intended target group comes into contact with the intervention (reach). It covers objective 1 of this study, i.e., describing the implementation strategy.

The mechanisms of impact domain identifies the process through which the intervention and implementation activities produce changes (i.e., objective 2; to explore participants responses and interaction with the intervention).

The contextual factor domain explores the contextual elements that positively or negatively affect the implementation and outcomes (i.e., objective 3; to identify contextual factors influencing the implementation).

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee (protocol P18.038) of the Leiden University Medical Centre. All participants gave written informed consent.

The intervention and implementation strategy

Details about the Fast@home intervention and the preceding effect study are summarized in Box 1. For more details, see the previously published effect study [Citation20].

The implementation strategy included activities in the following four domains: Information provision, Integration, Instruction & support and Motivation. In preceding focus group and survey studies [Citation23,Citation24], barriers and facilitators in the implementation of eRehabilitation were identified. The implementation strategy was developed to target those barriers and facilitators. The implementation activities targeted almost all healthcare professionals working in the stroke teams, with a specific focus on the RPs, PTs and OTs who are primarily involved in delivering Fast@home to the patients. Several activities also targeted patients and their informal caregivers. An overview of the activities of the implementation strategy is given in .

Table 1. Implementation strategy of the Fast@home eRehabilitation intervention.

The activities of the implementation strategy started three months before the use of Fast@home and continued during the year that Fast@home intervention was delivered as part of the conventional stroke rehabilitation (i.e., the intervention period).

Information provision

All potential end-users (patients, informal caregivers, healthcare professionals) were informed about the availability and potential advantages of Fast@home, prior to the start of the intervention period and by means of internal and external communication, presentations and promotion materials (banners, flyers, etc.).

Integration

For the integration of the intervention within conventional rehabilitation, the conventional rehabilitation process was described step by step. Next, a meeting was organized with representatives of the different professionals involved in each step of this rehabilitation process (e.g., OT/PT, RP, nurse, administrative assistant). During that meeting, the required adaptation for the integration of Fast@home into conventional stroke rehabilitation was discussed. The results were included in practical guidelines, describing which actions should be taken by whom within each phase of the rehabilitation process.

Instruction & support

Before the start of the intervention period, RPs, PTs and OTs who were directly involved in the rehabilitation of stroke patients were instructed in the use and delivery of Fast@home. This was done during joined instruction sessions (3 h per session) prior to the start of the intervention period. Other stroke professionals (i.e., psychologist, social worker, etc.) were informed during presentations and via internal communication.

During the intervention period, support was given to the RPs, PTs, OTs and patients by a helpdesk (both telephone and email), manuals and specifically trained movement technology students. For the healthcare professionals, additional support was provided by a clinical champion. This clinical champion was a PT who was skilled in and motivated for the delivery of eRehabilitation. Each clinical champion (one per rehabilitation facility) was available for 2 h per week to support colleagues in using the eRehabilitation intervention and to pass on questions and feedback to the research team.

Motivation

During the intervention period, actions to support user engagement and to motivate users were executed, including presentations about Fast@home, arranging support for the use of Fast@home from their managers and showing them the added value of Fast@home for patients by a video of a patient using Fast@home.

Participants and data collection

Data collection of this mixed methods study are summarized in .

Table 2. Sources and data collection methods in the three domains of the MRC framework.

For the evaluation of the implementation (objective 1), data were collected using field notes, surveys among patients and healthcare professionals and user data of the Fast@home intervention.

To explore the mechanism of impact (objective 2), data from the aforementioned surveys were used.

For identification of the contextual factors (objective 3), data were collected using individual in-depth interviews with healthcare professionals and field notes.

Patients admitted during the intervention period could participate in the effect study [Citation20] and/or the process evaluation separately. All healthcare professionals that provided stroke rehabilitation during the intervention period were invited to participate in this process evaluation.

In-depth interviews

In-depth interviews concerned the barriers and facilitators for the delivery of Fast@home. The interview guide was based on the results of the preceding focus group study and survey study [Citation23,Citation24]. Questions included were: “What is your experience (feasibility, added value, integration) with Fast@home?”, “Why did you (not) deliver Fast@home?” and “How can we improve your experience?”

All OTs and PTs instructed in the delivery of Fast@home and still working for the rehabilitation facility (n = 35) were invited to participate in the in-depth interviews. We continued interviews with OTs and PTs until data saturation was reached (i.e., no novel concepts emerged during three consecutive interviews [Citation25]). The duration of the in-depth interviews varied from 20 to 40 min and were conducted by two researchers (SH, BB).

Field notes

During the implementation, field notes were made by the primary researcher and the clinical champions. These field notes concerned contextual factors influencing the implementation, perceptions of users and number of healthcare professionals attending instructional activities. Field notes were tagged with date and location where the field note was taken.

Surveys

Separate surveys were developed for the patients and for the healthcare professionals. The surveys included questions concerning the previously identified barriers and facilitators [Citation23,Citation24] and the activities of the implementation strategy. Both surveys were pilot tested on readability, content and length by two patients and five professionals.

The survey for the patients included gender, age and questions regarding the possession of digital technology including smartphone, laptop, tablet, PC (yes/no). The survey also included questions whether patients received an account (yes/no) and used Fast@home (yes/no). If patients did not used Fast@home, the survey was ended. If patients used Fast@home, they were asked to complete the following items: use of the five applications that were part of Fast@home (five items, yes/no), satisfaction about these applications if used (five items, range 0–10), awareness of the implementation activities (seven items, yes/no), the contribution of those activities to the use of Fast@home (range 0–10), the perceived barriers/facilitators in the context (seven items, range 0–10), satisfaction with the implementation in general and the Fast@home intervention in general (range 0–10), willingness to use Fast@home and eRehabilitation in the future (both yes/no) and whether patients performed exercises prescribed in the intervention without login in (yes/no).

The survey for the healthcare professionals included the following items: professional discipline, delivery of the five applications that were part of the Fast@home intervention (5 items, yes/no), satisfaction about these five applications if delivered (5 items, range 0–10), awareness of implementation activities (9 items, yes/no), the contribution of these activities to the delivery of Fast@home (range 0–10), perceived barriers/facilitators in the context (11 items, range 0–10), satisfaction with the implementation in general and Fast@home in general (range 0–10) and willingness to deliver the Fast@home intervention and eRehabilitation in the future (both yes/no).

The patient survey was sent out in May 2019 to 210 patients admitted during the intervention period (both patients who participated and patients who did not participate in the effect study), by email (n = 160) and on paper (n = 50) if no email address was available. Reminders were sent after two and four weeks. Thereafter, non-responders were phoned. If a patient responded to the call, the survey was administered by telephone if possible. The survey for healthcare professionals (all member of the multidisciplinary team, n = 80) was conducted in January 2019, individually during the weekly team conferences, to include as many as possible responders. For those not present at the team meetings, a personal email was sent to ask them to participate in the survey.

User data

For patients included in the intervention group of the effect study (n = 165), it was recorded whether they received and used Fast@home. For each patient who used Fast@home, the number of exercises performed in the individual applications of the intervention were recorded, and how long the intervention was used (days between the first and last exercise). Details about this data collection are published elsewhere [Citation20].

Data analyses

In-depth interviews and field notes

In-depth interviews were audio-taped and transcribed in full. Both in-depth interviews and field notes were analysed with initial line-by-line open coding. The codes were discussed between the two researchers and categorized according to the levels of the implementation model of Grol; i.e., the innovation, the organizational context, the individual patient, the individual professional, the financial context and the social context [Citation26].

Survey and user data

Survey and user data were described using means and standard deviations (SD), median and inter quartile ranges (IQR), or numbers and percentages. Participants who completed <90% of the survey were excluded. Analyses were performed using Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS 25.0 for Windows). STARI guidelines were used for adequate data collection, analyses and reporting [Citation27].

Results

Participant characteristics

shows the data gathering methods among patients and professionals, and displays the response rate for each method.

Figure 2. Data collection methods among patients and professionals including response rate and domains of the MRC framework for which the data are gathered.

In-depth interviews

Of the 35 healthcare professionals invited, 11 participated (response rate 31.4%), including 3 OTs and 8 PTs. Three of them were males (27.2%).

Surveys

Of the 210 patients included in the intervention period, 65 were not eligible to participate in the survey; four were deceased, of four there was no valid email or post address available and 57 patients refused participation. So finally, 145 patients were invited for the process evaluation, of whom 73 participated (response rate 50.4%), mean age of 62.9 (SD 13.2) years, 43 males (58.9%) and the majority (n = 68, 93.2%) possessing one or more digital devices. Of the 73 patients that participated, 41 (56.1%) were offered the eRehabilitation intervention and 22 of those 41 patients (53.7%) actually used it.

Of the 80 healthcare professionals invited, 51 participated in the survey (response rate 63.8%); 14 OTs (27.5%), 12 PTs (23.5%), 7 RPs (13.7%), 5 speech therapists (9.8%), 4 psychologists (7.8%), 3 social workers (5.8%) and 6 others (11.7%). If only the disciplines who were instructed in the delivery of Fast@home (i.e., PT, OT, RP) were included, 46 healthcare professionals were invited, 33 participated (response rate 73.9%), of whom 25 (73.5%) delivered Fast@home.

User data

165 patients were included in the effect study, mean age 62.6 (SD 10.5) years, and 103 (62.8%) were male. Detailed description of the patients included in the effect study can be find elsewhere (20).

Evaluation of the implementation (objective 1)

The implementation of Fast@home was evaluated regarding the following aspects of the MRC framework: fidelity, adaptations, dose and reach.

Fidelity

The implementation activities in the domains Information provision, Motivation and Instruction & support () were delivered as planned. However, from the field notes it appeared that regarding the domain Integration, only one out of the three teams in Basalt The Hague discussed the delivery of Fast@home during all weekly multidisciplinary team conferences. Furthermore, it appeared that during the second half of the intervention period, promotional activities (banners, flyers, etc.) were less frequently prepared and disseminated than the intended frequency of once per month.

Adaptations

shows activities that were executed in addition to the planned implementation activities, as recorded in the field notes. These activities were performed when the delivery of Fast@home fell behind. It included, amongst others;

Table 3. Adaptations made to implementation strategy, as reported in field notes.

extra instructional sessions for PTs and OTs, and the provision of more time for PTs and OTs to get familiar with the intervention. The aim of this training was to increase confidence of PTs and OTs in delivering Fast@home.

instruction for all members of the multidisciplinary teams other than RPs, PTs or OTs; i.e., speech therapist, psychologist, social workers, movement agogist (i.e., a therapist specialized in sport and physical activity for people with a disability) and nurses. All healthcare professionals were offered an eLearning about Fast@home, aiming to fulfil their needs for increased knowledge about Fast@home. In addition, the nurses and movement agogist received a face-to-face introduction in Fast@home by the clinical champion. This was done in response to the observation that PTs’ and OTs’ had insufficient time during regular consultations to support patients to start using the intervention. After the introduction in Fast@home, the nurses and movement agogist supported the first time use after the additional training.

Dose

shows the awareness of the implementation activities (dose). The field notes showed that 47 (95.9%) out of 49 invited RPs, OTs and PTs attended the instructional session for the Fast@home intervention. The survey data showed that each activity of the implementation strategy was noticed by 60.7% (range 45.5%–90.9%) of the 22 patients that actually used Fast@home, and 71.1% (range 48%-88%) of the 25 healthcare professionals that actually delivered Fast@home. Of all implementation activities, patients most frequently noticed the integration activity “discussing the use of Fast@home with the PT/OT” (n = 90.9%); healthcare professionals reported that they most frequently noticed the “promotional activities like banners, flyers, internal and external communication” (n = 88%).

Table 4. Dose of the implementation, based on survey with patient and healthcare professionals using Fast@home, n patients/healthcare professionals noticed activities of the implementation strategy, in n (%).

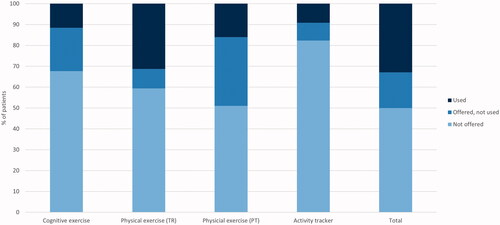

Reach

shows that 50% (n = 82) of the 165 patients with an account in Fast@home had access to at least one application. Subsequently, 65.6% of those patients actually used one or more of those applications (n = 54, 29 in The Hague and 25 in Leiden). The cognitive exercise application was used by 20 of the 54 (24.4%) patients, the physical exercise application Telerehabilitation (Leiden only) by 20 of the 25 patients (80.0%), Physitrack (the Hague only) by 16 of the 29 patients (55.1%) and the activity-tracker by 15 of the 54 (18.2%) patients.

Figure 3. Reach of patients, by the number of patients receiving and using Fast@home.

TR: Telerehabilitation; PT: Physitrack.

In , the median frequency of use of the applications is shown, also based on the user data. The cognitive exercise application was most frequently used (median 14 exercise sessions, IQR 2–37) and for the longest period (median number of days 26, IQR 9.5–150.5). The number of exercises performed with the two physical exercise applications were comparable (Telerehabilitation; median 9.5 exercise sessions, IQR 4–23; Physitrack; median 9.5 exercises sessions, IQR 3–51). However, Telerehabilitation was used on average for 25 days (IQR 16.5–62.5) and Physitrack for 9 days (IQR 1–21). The data of the activity-tracker was on average uploaded four times (IQR 1–15). The majority of the patients participating in the survey (n = 19, 86.5%) reported that they performed exercises prescribed in the Fast@home intervention without logging on since they know the exercises by heart.

Table 5. Reach of patients; use of applications within Fast@home by patients, based on the user data.

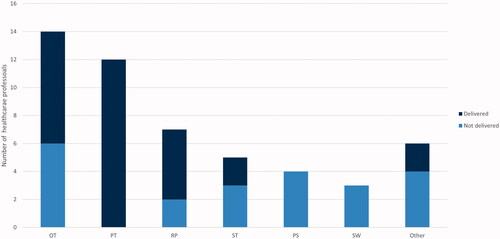

shows that 8 of the 14 OTs (57.1%), 12 of the 12 PTs (100%) and 5 of the 7 RPs (71.4%) delivered at least one application of the Fast@home intervention. Since additional instruction was offered to the remaining disciplines, also two of the five (40%) speech therapists delivered the Fast@home intervention, as well as two of the six (33%) other disciplines (a dietician and movement agogist).

Figure 4. Reach of professionals, by the number of professionals that delivered Fast@home to stroke patients.

OT: occupational therapist; PT: physical therapist; RP: rehabilitation physician; ST: speech therapist; PS: psychologist; SW: social worker.

Exploring mechanisms of impact (objective 2)

The mechanisms of impact are defined as the extent to which the implementation activities contributed to the delivery and use of the Fast@home intervention. The results that describe the mechanisms of impact are shown in , as measured with the surveys among patients who used (n = 25) and healthcare professionals who delivered (n = 22) the Fast@home intervention.

Table 6. Mechanisms of impact.

Interaction with implementation strategy

The satisfaction regarding the implementation activities of healthcare professionals and patients was comparable (median 7.0 [IQR 6.0–7.5] and 7.0 [IQR 6.0–7.75]). Healthcare professionals reported that the support of the clinical champion (domain instruction & support, median 7.0, IQR 6.0–8.0) and the time they were given to learn how to deliver intervention (domain integration, median 7.0, IQR 6.0–8.0) had the greatest impact of all implementation activities. On the contrary, activities in the domain integration hampered the delivery of the Fast@home, according to healthcare professionals. This included insufficient integration of Fast@home into conventional stroke rehabilitation (median 4.0, IQR 2.0– 6.0) and insufficient time to apply Fast@home in daily rehabilitation (median 5.0, IQR 3.0–7.0).

Multiple activities of the implementation strategy facilitated the use of Fast@home according to patients. The implementation activity with the highest impact was individual guidance by PTs and OTs (domain integration, median 7.0, IQR 7.0–8.0).

Interaction with the intervention

Healthcare professionals reported to be less satisfied about the use of Fast@home in general than patients (median 5.5 [IQR 4.0–7.0] and 8.0 [IQR 7.0–8.0] respectively). However, healthcare professionals reported to be satisfied about the physical exercise applications (Telerehabilitation median 7.0, IQR 7.0–8.0 and Physitrack median 7.0, IQR 5.57–8.0),the psycho-education (median 7.0, IQR 7.0–8.0), and the activity-tracker (median 6.0, IQR 3.0–8.0). Patients were also satisfied about the two physical exercise application (Telerehabilitation and Physitrack [median 7.0, IQR 6.0–8.0]), the cognitive exercise application (median 7.0, IQR 6.0–8.0) and the activity-tracker (median 8.0, IQR 6.0–8.0).

Furthermore, patients reported that the feasibility of Fast@home was high, despite stroke-related impairments (median 7.0, IQR 2.5–10.0). Healthcare professionals were more negative about the feasibility (median 5.0, IQR 4.0–7.0). The same difference between patients and healthcare professionals was found concerning the user-friendliness of the eRehabilitation intervention (professional median 5.0 [IQR 3.0–7.0], patient median 7.9 [IQR 6.0–7.25]).

Of the 25 healthcare professionals, 14 (56.0%) would recommend Fast@home to others and 22 (88.0%) wanted to deliver eRehabilitation in the future. When accounted for all responses of healthcare professionals (also those who did not deliver eRehabilitation), a similar proportion of 88.0% (n = 45) was found regarding the wish to deliver eRehabilitation in the future. In total, 20 of the 22 (90.9%) patients taking part in survey would recommend Fast@home to others and 19 (86.4%) were planning to keep using eRehabilitation in the future.

Identifying influencing contextual factors (objective 3)

shows the contextual factors influencing the implementation of Fast@home, based on the in-depth interviews with 11 healthcare professionals and field notes, reported according to the five levels of the implementation model of Grol.

Table 7. Contextual factors influencing the implementation, reported in interviews with professionals and field notes, reported to the five levels of the implementation model of Grol.

Six influencing factors concerned the Fast@home intervention (innovation), of which four reported both as barrier and facilitator and two reported only as barrier. These factors included Fast@home being evidence-based (barrier and facilitator), the content of exercise applications being useful to attain the specific rehabilitation goals of the individual patients (barrier and facilitator) and the number of patients per healthcare professional being too small to deliver Fast@home regularly and efficiently (barrier only).

Twelve factors, mostly barriers, were identified concerning the organizational context. These factors included insufficient integration of the Fast@home intervention into conventional stroke rehabilitation, resulting in healthcare professionals forgetting it. Insufficient time was also reported, both to learn how to deliver Fast@home and to deliver it in conventional stroke rehabilitation. Especially “playing time”, in which healthcare professionals can get acquainted with the new intervention was reported as important. Financial cutbacks during the intervention period resulted in less time for the healthcare professionals to properly incorporate Fast@home into their daily routine. Moreover, stroke patients were no longer merely admitted to stroke units, therefore some patients were treated by healthcare professionals who were not instructed how to deliver Fast@home. Another important barrier were technical setbacks including problems delivering the intervention on an Apple device and uploading data from the activity-tracker. A facilitator at the level of the organizational context was the presence of the clinical champion.

Four factors were identified at the level of the individual patient and three factors at the level of the individual healthcare professional. For both the patients and healthcare professionals, skills and knowledge about how to use and deliver Fast@home were reported as sufficient (facilitator) and insufficient (barrier). According to the professionals, insight in daily activities and exercises activities is an important reason for patients to start using Fast@home. For healthcare professionals a motivation to deliver eRehabilitation is that it facilitates the cooperation between PTs and OTs. According to the healthcare professionals, a reason for patients not to use Fast@home was that there is no added value of logging in, if the patient knew the exercises by heart. The motivation to deliver Fast@home for the healthcare professionals was hampered by the feeling of doing double work by prescribing exercises in one of the exercise applications and the local administration.

Concerning the social context, two factors were identified hampering the implementation of the Fast@home intervention: the belief of healthcare professionals in the effectiveness of eRehabilitation, and the relatively low priority for the implementation of eRehabilitation among managers and RPs.

Discussion

This process evaluation aimed to understand what worked and why in the implementation of an eRehabilitation intervention integrated into conventional rehabilitation for stroke patients and to identify areas of improvement for future implementations. The implementation strategy was mostly executed as planned and supplemented with additional instructional activities, resulting in the delivery of Fast@home by three-quarter of the healthcare professionals and in actual usage by two-thirds of the patients who received it. Regarding the mechanisms of impact, it was found that professionals and patients were equally satisfied with the implementation activities, but patients were more satisfied with the Fast@home intervention. The implementation activities with the highest perceived impact were personal guidance by PTs, OTs and RPs (for the patients) and the support of clinical champion, instruction and time given for learning to deliver Fast@home (for the healthcare professionals). However, professionals reported that Fast@home was insufficiently integrated into conventional rehabilitation. Contextual factors that hampered the implementation, including unexpected financial cutbacks and technical setbacks.

The current process evaluation enabled us to identify what worked and why and thus to reflect on how the implementation may have influenced outcomes and to highlight lessons for future implementation. Previous implementation studies only investigated potential barriers and facilitators for the implementation of eRehabilitation [Citation28–30] or the feasibility or acceptability when implemented [Citation31–33]. Below, areas of improvement for future implementations will be discussed for each of the three domains of the MRC framework.

Regarding the implementation strategy, on first sight the use of the Fast@home intervention by patients may seem quite low. A usage rate of 66% among those who received the intervention is, however, in line with previously published studies (66%–100%) [Citation34–38]. The number of days that the intervention was used (median 19 days) was higher than found in a previous study that reported a median of five days [Citation39]. Moreover, in the design of the Fast@home study, all patients admitted to conventional stroke rehabilitation were assumed to be eligible for eRehabilitation. This has probably resulted in a number of patients included in this study who were actually not able to use it, increasing the percentage of non-users of the total group of patients. Therefore, it is important to gain insights in and better define which patients would be eligible and who would benefit most from eRehabilitation [Citation8].

Regarding the mechanisms of impact, the delivery and use of the Fast@home intervention could probably have been improved as we succeeded (1) to integrate it better in the conventional rehabilitation and (2) to increase the healthcare professionals’ satisfaction with the intervention. To enhance the integration, additional instructions and time to get familiar with the Fast@home were offered to the whole multidisciplinary team. As a consequence of the involvement of the whole multidisciplinary team, the workload of PTs and OTs delivering the Fast@home intervention to patients was reduced and better manageable. Previous literature showed that starting to use an eRehabilitation intervention by patients required the support of a healthcare professions for on average 41 min [Citation39]. This support is found to be the most important for patients, in this study and before [Citation33]. Previously, it is already indicated that proper integration of eRehabilitation might be the largest challenge in the maturation of eRehabilitation [Citation5,Citation40] and that successful integration of eRehabilitation in conventional rehabilitation can probably only be achieved when all parts of the conventional rehabilitation are redesigned [Citation5]. Second, to increase healthcare professionals’ satisfaction, it is important to address healthcare professionals’ belief in the effectiveness of some of the applications within the Fast@home intervention. According to the healthcare professionals, the effectiveness of some of the applications in Fast@home was questionable, which influenced their motivation to deliver it. This confirms findings from previous literature, in which was stated that belief in the effectiveness of an eRehabilitation intervention is crucial for successful delivery [Citation23].

With respect to contextual factors, a prompt and better response to some observations in the present study could have led to better results. In our study, it appeared that healthcare professionals experienced additional barriers during the intervention period as to the ones they expected on forehand. These included financial cutbacks that forced healthcare professionals to focus on production instead of novelties like eRehabilitation, low priority given to the delivery of the intervention by managers and technical setbacks. This latter barrier was also found in previous studies [Citation5,Citation18], and thus it is an important point of attention for future implementation initiatives.

Based on all of the abovementioned findings, it is recommended for future eRehabilitation initiatives to increase delivery of eRehabilitation by healthcare professionals. This can be achieved by sufficient integration in conventional rehabilitation, increased satisfaction with the intervention and resolve barriers in the context. Therefore, it is important to redesign conventional rehabilitation in such a way that the eRehabilitation becomes an indispensable part of the rehabilitation process. For example, by setting treatment goals for patients that can only be met and measured using eRehabilitation. Such a redesign of the rehabilitation process should be done in co-creation with patients, healthcare professionals and the research team [Citation36]. Moreover, our results indicate that a flexible approach towards the implementation process is needed to give a better response to unexpected barriers, such as unexpected financial cutbacks.

Although this study provides some new insights in the implementation process of eRehabilitation in stoke care, some limitations should be discussed. First, this study focussed on the users of the Fast@home intervention more than on non-users. Thus, insight into non-users perceptions of why Fast@home was not used and what would have motivated them is limited. Second, the majority (86.5%) of patients reported to use Fast@home without logging in since they knew the exercises by heart. This underlines the challenges of accurately measuring the use of eRehabilitation applications. In our case, the actual use of Fast@home may probably have been higher than reported. Third, the delivery of Fast@home intervention by healthcare professionals as part of the conventional rehabilitation was voluntary, resulting in some OTs/PTs barely providing the eRehabilitation intervention to patients. Although there may have been good reasons for this, making eRehabilitation a fixed part of the conventional rehabilitation would maybe have resolved possible ignorance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the main areas for improvement of the implementation of eRehabilitation appear to be related to the perceptions of healthcare professionals that the intervention was not effective, the insufficient integration of eRehabilitation in conventional rehabilitation, as well as to contextual, mostly technical and organizational, barriers that hampered the implementation. Unexpected financial cutbacks and other organizational issues can have a large impact on implementation and should not be underestimated and actions to counter the negative consequences should be taken swiftly.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients and healthcare professionals participating in this project, and we are grateful to the consortium partners of this project for their effort in sharing expertise. Especially Silke Boon, Elmer Tiebackx, Charlotte Schutter, Liesbeth van der Wal and Edisa Hoorweg have contributed to this study. We are also indebted to many students of The Hague Universities of Applied Sciences and Leiden University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brochard S, Robertson J, Médée B, et al. What’s new in new technologies for upper extremity rehabilitation? Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(6):683–687.

- Galea MD. Telemedicine in rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2019;30(2):473–483.

- Chen Y, Abel KT, Janecek JT, et al. Home-based technologies for stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2019;123:11–22.

- Laver KE, Schoene D, Crotty M, et al. Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;16(12):Cd010255.

- Schwamm LH, Chumbler N, Brown E, et al. Recommendations for the implementation of telehealth in cardiovascular and stroke care: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(7):e24–e44.

- Webster D, Celik O. Systematic review of kinect applications in elderly care and stroke rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2014;11:108.

- Krpič A, Savanović A, Cikajlo I. Telerehabilitation: remote multimedia-supported assistance and mobile monitoring of balance training outcomes can facilitate the clinical staff’s effort. Int J Rehabil Res. 2013;36(2):162–171.

- Laver KE, Adey-Wakeling Z, Crotty M, et al. Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1(1):CD010255.

- Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223.

- Corbetta D, Sirtori V, Moja L, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46(4):537–544.

- Johansson T, Wild C. Telerehabilitation in stroke care-a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(1):1–6.

- Sarfo FS, Ulasavets U, Opare-Sem OK, et al. Tele-Rehabilitation after stroke: an updated systematic review of the literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(9):2306–2318.

- Nam HS, Park E, Heo JH. Facilitating stroke management using modern information technology. J Stroke. 2013;15(3):135–143.

- Standing C, Standing S, McDermott M, et al. The paradoxes of telehealth: a review of the literature 2000–2015. Syst Res. 2018;35(1):90–101.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):587–592.

- Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

- Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: the need for guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(2):101–102.

- Teriö M, Eriksson G, Kamwesiga JT, et al. What’s in it for me? A process evaluation of the implementation of a mobile phone-supported intervention after stroke in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):562.

- Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions. UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance; MRC Population Health Science Research Network, London; 2015.

- Brouns B, Bodegom-Vos L, Kloet A, et al. Effect of a comprehensive eRehabilitation intervention alongside conventional stroke rehabilitation on disability and health-related quality of life: a pre-post comparison. J Rehabil Med. 2020;53(3):0.

- Limburg M, Tuut MK. [CBO guideline ‘stroke’ (revision) Dutch Institute for Healthcare Improvement]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2000;144(22):1058–1062.

- Groeneveld IF, Goossens PH, van Meijeren-Pont W, et al. Value-Based stroke rehabilitation: feasibility and results of Patient-Reported outcome measures in the first year after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(2):499–512.

- Brouns B, Meesters JJL, Wentink MM, et al. Factors associated with willingness to use eRehabilitation after stroke: a cross-sectional study among patients, informal caregivers and healthcare professionals. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(9):665–674.

- Brouns B, Meesters JJL, Wentink MM, et al. Why the uptake of eRehabilitation programs in stroke care is so difficult-a focus group study in the Netherlands. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):133.

- Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–1245.

- Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004;180(S6):S57–S60.

- Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795.

- Davoody N, Hägglund M. Care professionals’ perceived usefulness of eHealth for post-discharge stroke patients. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;228:589–593.

- Hochstenbach-Waelen A, Seelen HA. Embracing change: practical and theoretical considerations for successful implementation of technology assisting upper limb training in stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012;9:52.

- Lutz BJ, Chumbler NR, Roland K. Care coordination/home-telehealth for veterans with stroke and their caregivers: addressing an unmet need. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):32–42.

- Caughlin S, Mehta S, Corriveau H, et al. Implementing telerehabilitation after stroke: lessons learned from Canadian trials. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(6):710–719.

- Szturm T, Imran Z, Pooyania S, et al. Evaluation of a game based tele rehabilitation platform for in-home therapy of hand-arm function post stroke: feasibility study. Pm R. 2021;13(1):45–54.

- White J, Janssen H, Jordan L, et al. Tablet technology during stroke recovery: a survivor’s perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(13):1186–1192.

- Chen J, Jin W, Dong WS, et al. Effects of home-based telesupervising rehabilitation on physical function for stroke survivors with hemiplegia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(3):152–160.

- Choi YH, Ku J, Lim H, et al. Mobile game-based virtual reality rehabilitation program for upper limb dysfunction after ischemic stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2016;34(3):455–463.

- Karasu AU, Batur EB, Karataş GK. Effectiveness of Wii-based rehabilitation in stroke: a randomized controlled study. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(5):406–412.

- Smith GC, Egbert N, Dellman-Jenkins M, et al. Reducing depression in stroke survivors and their informal caregivers: a randomized clinical trial of a web-based intervention. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57(3):196–206.

- van den Berg M, Crotty MP, Liu E, et al. Early supported discharge by caregiver-mediated exercises and e-Health support after stroke: a proof-of-concept trial. Stroke. 2016;47(7):1885–1892.

- Pugliese M, Ramsay T, Shamloul R, et al. RecoverNow: a mobile tablet-based therapy platform for early stroke rehabilitation. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210725.

- Blacquiere D, Lindsay MP, Foley N, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: telestroke best practice guidelines update 2017. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(8):886–895.