Abstract

Purpose

To assess the experience and perceived added value of an e-Health application during the physical therapy treatment of patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD).

Materials and methods

A mixed-methods study including semi-structured interviews was performed with orofacial physical therapists (OPTs) and with TMD patients regarding their experience using an e-Health application, Physitrack. The modified telemedicine satisfaction and usefulness questionnaire and pain intensity score before and after treatment were collected from the patients.

Results

Ten OPTs, of which nine actively used Physitrack, described that the e-Health application can help to provide personalised care to patients with TMD, due to the satisfying content, user-friendliness, accessibility, efficiency, and ability to motivate patients. Ten patients, of which nine ended up using Physitrack, felt that shared decision-making was very important. These patients were positive towards the application as it was clear, convenient, and efficient, it helped with reassurance and adherence to the exercises and overall increased self-efficacy. This was mostly built on their experience with exercise videos, as this feature was most used. None of the OPTs or patients used all features of Physitrack. The overall satisfaction of Physitrack based on the telemedicine satisfaction and usefulness questionnaire (TSUQ) was 20.5 ± 4.0 and all patients (100%) showed a clinically relevant reduction of TMD pain (more than 2 points and minimally 30% difference).

Conclusion

OPTs and patients with TMD shared the idea that exercise videos are of added value on top of usual physical therapy care for TMD complaints, which could be delivered through e-Health.

Physical therapists and patients with temporomandibular disorders do not use all features of the e-Health application Physitrack in a clinical setting.

Exercise videos were the most often used feature and seen as most valuable by physical therapists and patients.

Based on a small number of participants, e-Health applications such as Physitrack may be perceived as a valuable addition to the usual care, though this would need verification by a study designed to evaluate the therapeutic effect (e.g., a randomised clinical trial).

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

As the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic settled in the world, many countries experienced one, or multiple, enforced lockdowns. Some patients could still see a physical therapist (PT) if they had an emergency, but most practices were closed for business [Citation1]. Some practices, however, decided to switch to online therapy and implement e-Health [Citation1,Citation2].

E-Health can be defined as 'the delivery of personalised health care at a distance through the use of technology (i.e., computers, mobile phones or satellite communications) [Citation3,Citation4]. Also before COVID-19, e-Health was increasingly more relevant and applied in physical therapeutic health care [Citation5–8]. Even though there is some evidence that videoconferencing for patients with musculoskeletal disorders shows positive effects [Citation9], high-quality evidence for the effectiveness of e-Health is limited and inconsistent at best [Citation3]. Furthermore, it can be assumed that patients and PTs are sceptical about implementing e-Health [Citation10,Citation11].

Facilitators to use e-Health are familiar with and have adequate digital skills of the end users, perceived usefulness and utility, clarity of information, convenience, and the intrinsic motivation of the end user [Citation11,Citation12]. In a recent study, the facilitators and barriers to the use of e-Health were explored in patients with a temporomandibular disorder (TMD) and specialised, orofacial physical therapists (OPTs) [Citation13]. TMDs are health conditions involving the temporomandibular joint, the masticatory muscles and surrounding structures [Citation14], and they are often treated with a combination of hands-on (i.e., massage, stretching, and mobilization) and hands-off (i.e., exercises, counselling) interventions [Citation14–16]. The main barrier identified for using e-Health in the physical therapeutic care for TMD was the lack of personal (physical) contact [Citation13]. Both patients with TMD and OPTs stated that they were positive about the use of e-Health in a blended manner, especially in regards to home exercises [Citation13,Citation17].

One of the available e-Health platforms that can be used for physical therapy and TMD complaints, is Physitrack (Physitrack Limited, London, UK) [Citation18]. Physitrack is an online platform that can be accessed through a web page, or through an application on a mobile phone or tablet (PhysiApp). Physitrack has multiple features that can be used: video calls as an online consult, exercise programs including videos, instructions, a reminder function, questionnaires including pain intensity score, and a chat function between patient and OPT [Citation18]. Therapists can decide with their patients which features they would like to use for their patients and fit the Physitrack into their therapy programs.

Previous studies have shown high adherence rates to Physitrack in different patient populations, like patients with a musculoskeletal condition, or patients after an esophagectomy [Citation19,Citation20]. However, no research has been done on patients with TMD. Additionally, it is unknown how patients with TMD and their OPTs experience the use of e-Health, and if the additional value is perceived compared to the usual physical therapeutic TMD care. If patients and health care providers do not expect or perceive an additional value of an e-Health application, they are less likely to implement it successfully and in that case determining effectiveness will not be useful [Citation21,Citation22]. Hence, describing experiences and perceived additional value of both patients and OPTs could help implementation and future research. Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess the experience and perceived additional value of e-Health, using the Physitrack application, during the physical therapy treatment for patients with TMD.

Methods

This manuscript is structured according to the ‘Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study’ (GRAMMS) [Citation23]. For the qualitative part, the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) are followed [Citation24]. The funders of this study and Physitrack played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Study design

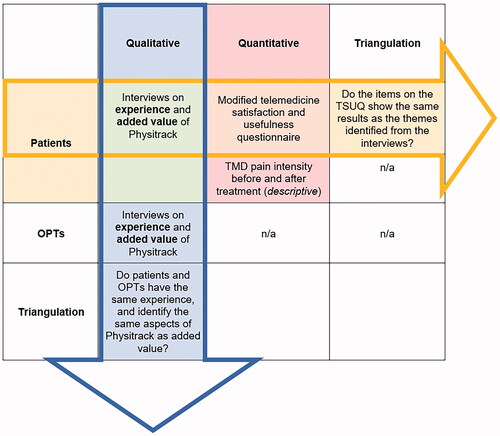

A concurrent triangulation mixed methods design was used [Citation25,Citation26]. Here, qualitative and quantitative data were collected from the same population to identify similarities and differences between outcomes sampled in the two methods, and to then present the overall findings. Because the implementation of new interventions, such as e-Health, is not only reliant on effectiveness but also on the perceived additional value, a mixed methods design is most appropriate to explore these aspects [Citation27,Citation28]. In the current study the focus was on the perceived added value of both OPTs and patients. During the qualitative data analysis, the experience of using Physitrack and the following perceived additional value were discussed during interviews. Furthermore, a questionnaire regarding user satisfaction was given to the patients for the quantitative data before the interview took place. This quantitative data together with data collected on used features of the e-Health program were used as background information to put the qualitative findings into context. The data sources and research questions are depicted in .

Figure 1. Overview of mixed-methods: data sources and research questions.

Study population

For OPTs convenience sampling was applied as OPTs were recruited through previous study participation [Citation13], a mailing list of the Dutch Society for Orofacial Physical Therapy and LinkedIn. There are approximately 180 OPTs in the Netherlands (gender distribution 50:50 female:male), of which half of them are estimated to have a master’s degree in the specialisation of Orofacial Physical Therapy. To be included, OPTs needed to have a master’s degree in the specialisation of Orofacial Physical Therapy, and they needed to have a membership to Physitrack. In the Netherlands, Physitrack is one of the most used e-Health applications within physical therapy practices [Citation18]. OPTs were excluded if they worked less than one day a week with orofacial pain patients.

For the patients with TMD, snowball sampling was applied, as they were invited by their OPT to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria were: 1) TMD complaint; 2) aged 18 years or older; 3) having had minimally two treatment sessions (face-to-face or online) with their OPT; 4) no serious underlying conditions for the TMD complaints; and 5) being able to communicate in Dutch or English. If the patient was referred to the OPT by a dentist or medical doctor, the information regarding TMD diagnosis and absence of serious underlying pathology was extracted from the referral. In some cases, the patient came directly to the OPT without a referral through direct access [Citation29], and the OPT classified the presence of a TMD based on the history and physical examination of the patient. Pain in the masticatory system that was aggravated by function or palpation was classified as myalgia or arthralgia, dependent on the location of the pain [Citation30,Citation31]. Clicking and locking of the joint were an indication of a disc displacement [Citation31]. All OPTs were trained in the diagnostic process of patients with TMD during their master’s program, using the diagnostic criteria for TMD (DC/TMD) and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation31,Citation32], comparable to a proposed diagnostic process for physical therapists to use in patients with TMD [Citation33].

Participants were recruited until saturation of the data was achieved. Saturation was achieved when no new information could be identified from the last two interviews and was expected to occur between six and twelve interviews per group [Citation34]. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (201972). All participants signed an informed consent form.

Qualitative data collection: interviews

Semi-structured interviews were performed with individuals using pre-defined topic guides, asking about experiences with physical therapy in general (for patients), the experience with Physitrack, the perceived added value of Physitrack, the reason for using Physitrack and future opportunities (for OPTs; see also Appendix 1). The topic guides were developed by the research team in an open discussion, using information from previous research [Citation13]. They were open to changes when interviews identified new information.

Three members of the research team (HvdM, AD, CMS) were actively involved in collecting and processing the data. One member (MN) had an advisory role regarding the topic guides. The OPTs were interviewed by HvdM, who is an OPT and knew all participating OPTs personally before the interviews. The patients were interviewed by a master’s student of orthopaedic manual therapy and a graduated physical therapist (AD), who was trained by HvdM. AD did not have any personal relationship with the patients who were interviewed, but they did have knowledge of TMD and the physiotherapeutic methods regarding TMD treatment. Before the interview started, a casual conversation was started to establish a comfortable environment for the participants to tell their stories, and to ensure no imbalance in the power relationship was felt [Citation35]. Before the COVID-19 lockdown, the interviews were held at a location preferred by the participant, during the COVID-19 pandemic all interviews were done online in a secured environment. The interviews were recorded (audio and video for the online interviews with the OPTs and only audio for the interviews with patients). Then, the interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into nVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2020) for further analysis.

Quantitative data collection: characteristics and outcome measures

Information from the OPTs concerned: age, gender, years of work experience in general, years of work experience with TMD patients, type of work setting, and working hours per week. From the patients’ files characteristics of the patients were collected: age, gender, TMD diagnosis, and TMD pain intensity (measured with the numeric pain rating scale [NPRS] ranging from 0 to 10[Citation36]) before and after treatment, combined with additional information on the treatment trajectory: number of (physical) treatment sessions, number of online treatment sessions, and applied functionalities from the Physitrack application.

Furthermore, patients were asked to fill out a modified telemedicine satisfaction and usefulness questionnaire (TSUQ) as additional background information which could be used for the triangulation of results. The TSUQ is a 30-item Likert-type questionnaire including three subscales (satisfaction e-Health, satisfaction communication, and usefulness) [Citation20,Citation37]. For the first two subscales, the Likert scale ranged from 1 (‘I agree with the statement’) to 5 (‘I do not agree with the statement’). The Likert scale for usefulness ranged from 1 (‘very useful’) to 5 (‘not useful at all’). The total score ranged from 30 to 150, where lower scores indicate higher agreement, and therefore higher satisfaction and usefulness [Citation20,Citation37]. The modified version of the TSUQ asks patients about their physical therapist instead of doctor or nurse, and refers to e-Health/Physitrack instead of ‘telemedicine’ [Citation20]. Because the TSUQ was developed for patients, OPTs were not asked to fill out this questionnaire. Due to this, only triangulation between qualitative and quantitative findings could be done for the patients’ perspective on the additional value of Physitrack. The TSUQ was filled out before the interview took place.

Qualitative analysis

The analysis process of the interviews was done in a similar fashion for the OPTs (HvdM & CMS) and the patients (AD & HvdM). The interviews were read, and open coding was applied to identify important aspects of the interviews using nVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2020). These codes were compared after the third and last interview, checking if consensus between researchers was present. If there was no consensus, the researchers discussed the codes until consensus was met. Then, axial coding was applied to identify themes. Because this process was done separately for patients and OPTs as their topic guide was slightly different, different themes could emerge from the interviews. The themes were compared between patients and OPTs, to see if there was an overlap in certain aspects. Quotes from the interviews were used to support the themes and were translated into English by HvdM. Quotes by patients are marked as Ptnumber and quotes by OPTs are marked with OPTnumber. The themes were presented to the OPTs via e-mail, and participants were asked if they identified themselves with these themes, to increase credibility [Citation38].

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the participants. All outcome measures related to the treatment (pain intensity before and after treatment, number of sessions, use of Physitrack) as well as the TSUQ scores were depicted using descriptive statistics. Clinically relevant changes in TMD pain intensity were determined to be more than 2 points and a minimally 30% difference on the NPRS [Citation39–41]. No further analyses were performed due to the small sample size available.

Triangulation between qualitative and quantitative data

Two types of data triangulation were applied (see ). The first was to compare the qualitative findings of the OPTs with the qualitative findings of the patients regarding the experience and perceived additional value of Physitrack. Furthermore, the findings of the quantitative data (TSUQ, pain intensity scores and features used) were used to put the qualitative outcomes regarding the additional value of Physitrack into context. When possible, the qualitative data of the patients were compared to the quantitative outcomes (TSUQ) of the patients to evaluate if the themes identified from the interviews support the findings from the quantitative outcome measures and to establish if there is a convergency or discrepancy in findings.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Ten OPTs participated in the study (see ) with a mean age of 34.3 years (male: 80%). All but one OPT worked in a private practice, of which three combined their work with working at a dental department or headache clinic. The mean work experience was 11.5 years, and the meaningful work experience specifically in the field of TMD was 4.6 years. Characteristics of the OPTs are depicted in . All OPTs had a subscription for Physitrack, but only nine used one or more features of Physitrack actively. Six OPTs recently started using Physitrack due to COVID-19. The nine OPTs who actively used Physitrack all used the exercise videos, and they all used the video conference call functionality. Other functionalities like tracking progress and adherence, communicating via text message and sending or receiving patient information were not or infrequently used (see also ). OPTs did not offer the complete e-Health program to the patients, only features that the OPTs themselves used.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of orofacial physical therapists.

Table 2. Used functions of the Physitrack application prior to the interview.

Ten patients were recruited by four OPTs. The mean age was 52.3 years, all were female, and the mean number of treatment sessions was 4.9. Characteristics of the patients are depicted in . All but one used Physitrack at least in a part of their treatment course. One patient was unable to install Physitrack and therefore didn’t use the application. Five patients were interviewed before the COVID-19 pandemic and the other five were interviewed during the pandemic. Two patients had at least one online session prior to the interview (), and three other patients had an online consult after the interview but during their treatment process (). Of the nine patients using Physitrack, all used the exercise video feature, two had one or more video conference calls with their OPT and two used the reminder and adherence function (see also ). Every patient received a tailored treatment plan, which included counselling on complaints, aspects of daily activities, and pain education. This was often done during a face-to-face consult when possible. Furthermore, exercises were aimed at the jaw, cervical spine and/or entire body (for example progressive relaxation exercise), which were often given using the e-Health application. When indicated, patients received manual therapy during the face-to-face sessions. All patients showed clinically relevant changes in their TMD pain intensity scores after treatment (more than 2 points and minimally 30% difference [Citation39–41]).

Table 3. Basic characteristics patients with TMD.

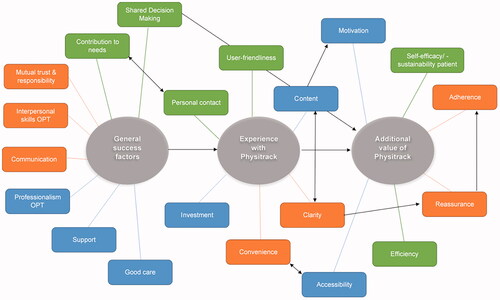

Based on the research questions and topic guides, there were three major themes present for both OPTs and patient participants: (1) general determinants for success; (2) experience with Physitrack; and (3) additional value of Physitrack. The sub-themes showed some variability between the OPTs and patients (see also and ).

Figure 2. Model of interaction between sub-themes identified by orofacial physical therapists and patients. Green: sub-themes identified by both orofacial physical therapists (OPTs) and patients; orange: sub-themes identified by patients; blue: sub-themes identified by OPTs; grey: major themes.

Table 4. Overview of themes for both patients and orofacial physical therapists.

Perceived factors of importance for adequate care

The success of orofacial physical therapy in general and the success of using Physitrack was dependent on a few different factors. Most OPTs described that good care was important, which for them meant listening to your patient and to provide personalised care. All OPTs stated that patients are responsible for their own recovery: “I teach you to help yourself” (OPT05). Most patients agreed with this statement, stating they understood their own responsibility and that mutual trust is essential. Patients felt that the interpersonal skills of, and communication with their OPT were important for success: “Well, very enthusiastic [the OPT] and that stimulates me as well” (Pt03). Both OPTs and patients described how the professionalism of the OPT was an important factor as well, which was also related to the trust that patients had in the therapy. Importantly, the OPTs and patients all felt it was important that the therapy was based on shared decision making. Especially in the case of applying an e-Health application like Physitrack, this needs to be discussed: “If I think that it is a patient that would want to use it, I always ask, like, ‘I have the possibility to also send this exercise on video’, and if I see people feel the need for this, then I always apply it” (OPT10). In some cases, OPTs and patients did not see the need for e-Health, and would then decide not to use it. This contribution of needs was an important factor of influence on choosing to use an e-Health application, in this case, Physitrack. For example, one OPT did not feel the need to use Physitrack during the COVID-19 lockdown, despite having a subscription for the platform: “I did weekly telephone calls, with the patients, asking how they were doing. And some said they were not managing, then we discussed if they had done auto-massage” (OPT09). One of the patients (Pt07) was given access to the program but they had trouble logging on, so they did not use the program, nor felt the need to do so. The patient stated that “for the jaw I don’t see a necessity to learn” how to use the computer program, as the combination of verbal instructions of the OPT and the printed exercises were sufficient.

Experience with physitrack

The six OPTs who started using Physitrack during the COVID-19 pandemic chose this platform due to the available content and its quality, and the positive experiences of other colleagues in the field. The exercise videos were seen as the most important content aspect of Physitrack, which all but one OPT used as a feature with their patients. Some of the patients said they felt these videos were very clear, and they knew what was expected of them (clarity). One OPT stated, “It [video] does slightly stimulate a bit more [to exercise] than yet another piece of paper” (OPT05), whereas one of the patients did not agree with this: “I find it easier to have it on paper, because then I can just grab it when I want to and otherwise you have to go to your computer, turn on that thing, that program… well you name it” (Pt07).

The patients that used Physitrack, were positive about the user-friendliness of the application. Most OPTs agreed but felt that not all features were as smooth as they should be, for instance, the video calls were not very easy and did not always work. The video calls were seen as a nice feature that could be used during the lockdown, but not necessarily as a replacement for the physical consult in the future. One OPT stated: “I am really into body language and that is hard to do through video, I noticed. It is distant, you sit and watch a screen, it is less personal. […] If it is about evaluation, really how are your exercises going, do you think it helps, do you want to adjust your exercise program, are there things you don’t understand, check up in between and also final evaluation, those are doable with video, I think” (OPT01). One patient even said that they would prefer phone calls over a video call: “Well I do not really specifically need a face, well at least if I already know the person it is not necessary. Sometimes if you do not know someone then you think ‘What do they look like, or what is their expression’, but if you already know someone you do not really need it, it can also be a distraction” (Pt05). Overall, OPTs and patients were concerned about the personal contact. “Of course, it is nice that you can [practice] yourself, but sometimes you just cannot fix it yourself. And then you can practice as much as you can, but then I just need her [the OPT]” (Pt08). Patients felt that Physitrack was very convenient, due to the user-friendliness and clarity, and it opened another door for communication with the OPT. The OPTs experienced this differently, and mostly saw an extra investment in time, money, and administration. However, a few OPTs stated that once you have implemented the application and you are used to it, some features are worth this investment: “Back in the day, I did not see the value to pay for it, because I physically saw patients in the clinic. […] For the video consults I do not know, but for the exercise programs I do think it is worth [the costs], because there are more videos, you can easily send the exercises and monitor adherence a bit better” (OPT01).

Additional value of physitrack

When asked what the additional value of Physitrack was on top of the regular therapy possibilities, the overall message of most OPTs and patients was the same: Physitrack can support increasing self-efficacy and self-sustainability of the patient. Some OPTs and patients said that Physitrack was suitable for this, as “It is always nice that people just have a program to fall back on to go through their exercises properly again” (OPT01). One patient said that Physitrack helped to feel reassured about doing the exercises at home: “At home one can see exactly how to do the exercises, uh, because it is explained, but yeah when you are at home you think how should I position my head […] so yes it is convenient to have the app at hand and it is clear in that video how the exercises should be performed exactly […], I think that’s nice, because one forgets it.” (Pt01). Additionally, some patients felt that the tracking feature on Physitrack helped to increase adherence to the exercises: “You are reminded by e-mail, that is nice, because sometimes you have a day, you think ‘oh forgotten’ and then it pops up. And papers you put aside or in a drawer and then you do not think ‘I need to do that now’.” (Pt04). Not every patient shared this idea, as they felt it was their own personal responsibility to do the exercises and an external reminder would not be helpful: “I don’t need it [check boxes] because I think it would take too much time. I look to myself as a measurement instrument. I notice how it helps, so then I continue practicing and I think ‘I’m doing it for my own sake, I want to have it cured, get rid of the pain in my jaws’.” (Pt10). One OPT mentioned that not all patients can motivate themselves to do their exercises, so Physitrack can help: “You do not have an excuse not to do it [exercises], you get reminders!” (OPT02).

Another added value of Physitrack was that it enhanced accessibility of the specialised OPT for patients, regardless of location in the country. Especially when physical consults were not available, Physitrack was a good alternative. Even though most OPTs and patients still preferred physical consults, some saw opportunities to apply more features of Physitrack in the future: “I always thought like, you know a video consult does not replace the physical consult. For an intake I am still convinced this is the case but for follow-ups I definitely see a possibility that e-Health will take a larger place than it has so far” (OPT10). From those who had positive experiences with Physitrack and saw additional value, it was mostly in a blended form where the exercise videos were considered most valuable, especially after proper instruction of the OPT: “Exactly, it’s really clear. I had done the exercise one time at the [OPT’s], so in that way you know it a bit like press harder or softer, one tends to press harder than needed, and so [OPT] corrected me like that’s not necessary, you don’t need to press that much, so do it like the video, but don’t make it too hard, than you strain it too much, so the introduction by [OPT] followed by the video, well, fine!” (Pt10).

Quantitative findings patients

Seven patients came in with pain complaints with a mean of 5.5 ± 1.6 points on the NPRS. At the end of their treatment plan, which varied between 3 to 8 sessions, the TMD pain intensity decreased to 1.1 ± 0.6. Of the six patients with headaches, the headache pain intensity score also decreased over time from 6.3 ± 2.1 to 2.5 ± 2.7.

The nine patients who used Physitrack have filled out the TSUQ and answered the items which were related to the facilities of Physitrack that they used (See ). User-friendliness was one of the identified sub-themes from the interviews, which was also recognised in the scores on the TSUQ. Overall, patients were satisfied with the ease of the use of Physitrack (1.9 ± 0.4). Patients felt that Physitrack was easy to use, as shown by the scores of the ease of using (1.22 ± 0.4) and starting to use Physitrack (1.33 ± 0.7). This is comparable to the findings of the qualitative data analysis. Patients disagreed most with the statement that their OPT used the information from Physitrack to evaluate the patient (3.13 ± 1.2), whereas this was an important aspect for patients identified under the themes communication and mutual trust & responsibility – i.e., the patients would have preferred that the evaluation functionality would have been used more frequently but the OPT did not use this feature.

Table 5. Results of the telemedicine satisfaction and usefulness questionnaire.

Three patients did not fill out items of satisfaction about online consults, as they did not receive online or phone consults. The remaining six patients were not agreeable, nor disagreeable, with the overall satisfaction of the online consults (2.6 ± 0.4). They specifically disagreed with the statement that an online consult is just as efficient and satisfactory as a physical consult (4.6 ± 0.8) and that online consults are a good way to receive physical therapy (4.2 ± 0.8). They agreed with the statement that they missed the physical contact during an online consult (1.7 ± 1.0). All of this is comparable to the findings of the interviews, where personal contact was seen as very important, and this could not always be achieved through online care.

All nine patients agreed on the items regarding the usefulness of Physitrack (1.5 ± 0.5); the videos of the exercises were useful (1.0 ± 0.0), the overall exercise program (1.3 ± 0.5) and the related instructions were useful (1.3 ± 0.7). During the interviews, patients also identified the exercise videos and their instructions as most useful. The items with the highest score (i.e., least useful) were regarding the usefulness of the questionnaires (2.7 ± 1.3) and the feedback option (2.5 ± 1.5). This feature was often unknown to the patient, or not seen as necessary.

Discussion

The key findings of this study show that both patients with TMD and their OPTs feel that the exercise videos were considered to be the strongest additional value of using Physitrack, which was the most (and sometimes only) feature used by the participants in this study. Online consults (i.e., video calls) were only seen as valuable when physical care is not an option, for instance during the COVID-19 lockdown or in case of long travel distances, but were not preferred as they were not seen as having the same value as a face-to-face consult.

In the current study, there is a discrepancy between what the OPTs stated they offered and what patients used (). Furthermore, patients stated they most valued the exercises, but for some, this was the only feature they had used. This means that the results of the current study from the patient population are only based on limited experience with the e-Health application. Patients may not be aware of the possibilities and value of the other features, because they did not use them or knew they existed. The lack of use of different features by the patient may be due to a few reasons. One may be that the OPT decided which feature to offer to that specific patient, rather than implement the shared decision-making approach where the OPT and patient discuss all options together within the treatment process and then decide together which features are available and preferred to use. Another possibility is that the OPTs are not yet properly trained in using an e-Health application during their regular physical therapeutic process, leading to incomplete use of all e-Health features. In a study of a population with rheumatoid arthritis, the used e-Health application was also not fully embedded in routine health care [Citation42]. Receiving specific training may lead to full implementation of all the Physitrack features, which could change the perceived added value of the different features [Citation43].

The current study shows that OPTs and patients feel that an e-health application like Physitrack could support self-efficacy, by giving patients the tools to do things from home in their own time and pace. In patients with impairments in sports, lower limb injuries, or paediatric neurology, the satisfaction with the use of online consults was high, specifically due to the limited travel time and convenience of receiving therapy in a familiar environment [Citation44]. The question that still remains, however, is if e-Health is just as effective, or perhaps even more effective, than only physical consults. In general, e-Health is recommended for musculoskeletal physical therapy [Citation7], but the (cost-) effectiveness remains unclear for most patient populations [Citation3,Citation45]. Other studies show that remote interventions by dentists through online programs or telephone support are effective in patients with TMD [Citation46,Citation47]. Both interventions aimed to increase awareness in patients regarding their complaints and influencing factors such as psychosocial factors, lifestyle, and bruxism. This is also one of the main goals of orofacial physical therapy [Citation13], which shows that remote interventions could be beneficial in multidisciplinary approaches as well. However, the results from other studies also show that the remote intervention does not necessarily have to be applied through an e-Health application like Physitrack. In the current study, one of the OPTs and some patients stated that telephone support can be just as useful in some cases. The applied intervention and the chosen application should always fit the patient’s preference and technological ability.

Even though the number of participants was low in the current study, the results suggest that the blended form applied by the OPTs (i.e., using Physitrack during the treatment process) was effective to decrease complaints, and increase perceived self-efficacy, though larger trials should confirm this finding for short- and long-term follow-up. Other patient populations show the same results [Citation48,Citation49], illustrating that e-Health can be a valuable addition to usual physical therapeutic care. E-Health may contribute to the self-efficacy and therefore be an important aspect of self-management programs which are recommended for TMD [Citation15]. It would be important to distinguish between the different TMD diagnoses, as self-management programs and exercises, which was the most valuable aspect of this e-Health program, are mostly recommended for pain-related TMDs such as myalgia [Citation15,Citation50,Citation51]. In the current study, all active users of Physitrack had a pain-related TMD, so such distinguishment could not be made.

Additionally, based on the shared decision-making principle, using e-Health should be discussed with the patient as not every patient may be suitable or open to using the application. For instance, patients with severe pain or chronic pain may not be as open-minded to e-Health as they may experience a higher therapist-dependency [Citation52,Citation53]. Recently a consensus opinion was published about the appropriateness of e-Health in the management of chronic pain [Citation54], which could be applicable to patients with chronic TMD. Furthermore, to help physical therapists during this conversation, a special checklist developed for this purpose can be used [Citation55]. This checklist is, however, not yet validated for patients with TMD complaints.

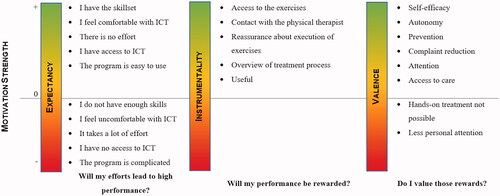

One of the important aspects of the checklist for blended interventions, as well as the findings of the current study, show that the motivation of patients to use the e-Health application is important. The motivation of patients is related to the effort required of the patients, the result of this effort and how it influences the needs of the patient. This is similar to what Vroom’s expectation theory describes [Citation56]. According to this theory, people are motivated when they expect to complete the task at hand if this leads to the desired outcome and when it fulfils a need. shows the themes and examples from the current study related to the expectation theory. One aspect that is not taken into consideration in this figure, is how therapeutic alliance may play a role in the motivation of the patient to do their exercises or to use e-Health. In the current study, patients identified that the interpersonal skills and the personal connection they had with their OPT were important factors for adequate care. This may have also influenced their perceived value of e-Health or other aspects of the therapy. This relationship between the patient and OPT is part of a therapeutic alliance, which may influence therapeutic adherence [Citation57]. Patients now stated that e-Health helped with adhering to the exercises at home, but this may also be due to this strong therapeutic alliance. In patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain, similar results were found where mutual trust, a good relationship between physical therapist and patient, and proper communication were important factors to success [Citation58]. However, there is little known about the therapeutic alliance in patients with TMD, so future studies should look into this aspect [Citation59].

Figure 3. Strength of motivation to use Physitrack for patients with a temporomandibular disorder related to the expectation theory.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of the current study was the use of a mixed-methods approach allows for a stronger conclusion of the findings [Citation27]. The mixed-methods approach shows the importance of nuance and shared decision making, as outcomes of the TSUQ would sometimes indicate patients were not satisfied with certain aspects of the e-Health system, whereas the interviews showed that it was very context dependent. This approach has been suggested for telehealth studies because it does shed light on the nuances and differences between quantitative and qualitative findings [Citation27]. In the current study, the TSUQ was filled out before the interview, but the answers were not used during the interview. Having seen the TSUQ before the interview gave patients the time to reflect on their experiences so they could formulate answers better during the interview. Future studies should consider, however, a larger study population to make statistical analysis possible to study if there is an association between satisfaction based on TSUQ scores and the effectiveness of the intervention.

Another strength is having the perspective of both patients and OPTs creates a broader understanding of what the additional value of e-Health, in this study through Physitrack, is during the physical therapeutic care. To determine the effectiveness of a blended e-Health intervention, randomised controlled trials are needed. Additionally, future studies should consider looking into successful implementation factors, as the current study showed that not all features of an e-Health application are used in practice and this may bias the end results.

There are a few other aspects that need to be considered. Saturation was reached after 10 interviews in both the patient and OPT population, but in both populations, there was only one deviant case (i.e., someone who did not end up using the Physitrack application). This may have caused a positive bias in the results and not an adequate reflection of the general TMD-patient and OPT population in the Netherlands. Even though saturation on the overall themes was reached, this small number of patients could have created a skewed outcome in the current study. A larger number of participants in both groups would have possibly created more contrast in answers and given more insight into what aspects truly were of additional value, and what features were not. Additionally, all patient participants were female. Even though TMD is more prevalent in females [Citation60], it is also common in men. There may be a difference in the perceived value of e-Health, as well as usage, in the different genders [Citation61]. There may also be a gender bias in the sample of OPTs, as they were predominantly male (80%) compared to the working population (approximately 50%). As previous studies have shown there is a difference in use and technology adaption between genders [Citation62], this may indicate that male OPTs were more likely to use e-Health or more willing to participate in the study. This may have led to an imbalance in included OPTs and therefore may not reflect the views of the entire OPT population. Another limitation is that the OPTs had to have a subscription to Physitrack to be included, which is a form of selection bias as OPTs who have a subscription are more likely to use it and be positive towards the use of it. However, one of the included OPTs had a subscription but still did not use it, which counterbalanced the findings in some way. Additionally, included OPTs recruited patients for the study, which may have led to selection bias of the patients. To decrease the chance of selection bias, OPTs were instructed that all patients with TMD who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were eligible, and they were discouraged to only invite patients who had a successful treatment. Furthermore, not all OPTs recruited patients for the study, meaning some OPTs recruited multiple patients and others none at all. This could decrease the credibility of the triangulation of the qualitative findings of the OPTs and patients.

Lastly, Physitrack is an e-Health platform that consists of multiple features, but none of the OPTs used all the features with their patients. Most patients only used between one and three features, leading to an incomplete view of the program. It could be that OPTs only used some of the features, for instance, the video-calling, due to the COVID-19 lockdown which otherwise would not have been used. Most OPTs did state, however, that they are likely to keep using this feature even when the COVID-19 pandemic is not a factor anymore. As the e-Health component of the intervention was comparable to a digital exercise flyer, OPTs would not necessarily need a full e-Health platform but could also send exercise videos via mail or on a different multimedia website. Patients were positive towards the exercise videos and therefore seem positive of e-Health, but currently the exercise videos were the only (or small) part of e-Health they came in contact with. The patient’s experience with e-Health was biased by the attitude of the OPT towards e-Health. Based on this study of the perception and experience of OPTs and patients, we can conclude that there are specific elements of the e-Health application that the participants found of additional value on top of usual care. Future studies should work with a protocol where all features are used in an integrated manner, to see what the value of the entire application is on top of physical therapy care for TMD.

Conclusion

OPTs that used e-Health as part of their treatment of patients with TMD, used exercise videos for homework assignments and video consults when face-to-face consults were not available due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Other features of the e-Health application (Physitrack) were rarely used by OPTs and therefore also rarely used by patients. Patients were positive about the implementation of exercise videos through the mobile PhysiApp but did not feel e-Health can replace face-to-face consults. For some participants using an e-Health application was not seen as necessary, as telephone consults or exercises printed on paper were just as beneficial.

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest within this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Confederation for Physical Therapy. WCPT response to COVID-19; Rehabilitation and the vital role of physiotherapy acknowledgement. 2020.

- Minghelli B, Soares A, Guerreiro A, et al. Physiotherapy services in the face of a pandemic. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2020;66(4):491–497.

- Elbert NJ, van Os-Medendorp H, van Renselaar W, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ehealth interventions in somatic diseases: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(4):e110.

- Moss RJ, Süle A, Kohl S. EHealth and mHealth. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;26(1):57–58.

- Schiavo R. The rise of e-health: current trends and topics on online health communications. J Med Market. 2008;8(1):9–18.

- Ramage ER, Fini NA, Lynch EA, et al. Supervised exercise delivered via telehealth in real time to manage chronic conditions in adults: a protocol for a scoping review to inform future research in stroke survivors. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e027416.

- Cottrell MA, Russell TG. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;48:102193.

- van Egmond MA, van der Schaaf M, Vredeveld T, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy with telerehabilitation in surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother. 2018;104(3):277–298.

- Grona SL, Bath B, Busch A, et al. Use of videoconferencing for physical therapy in people with musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(5):341–355.

- Hennemann S, Beutel ME, Zwerenz R. Ready for eHealth? Health professionals’ acceptance and adoption of eHealth interventions in inpatient routine care. J Health Commun. 2017;22(3):274–284.

- Li J, Talaei-Khoei A, Seale H, et al. Health care provider adoption of ehealth: systematic literature review. Interact J Med Res. 2013;2(1):e7.

- Simblett S, Greer B, Matcham F, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of engagement with remote measurement technology for managing health: systematic review and content analysis of findings. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(7):e10480.

- van der Meer HA, de Pijper L, van Bruxvoort T, et al. Using e-Health in the physical therapeutic care process for patients with temporomandibular disorders: a qualitative study on the perspective of physical therapists and patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2020:44(4):617–624.

- de Leeuw R, Klasser GD. American academy of orofacial pain guidelines for assessment, diagnosis, and management. 5th ed. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2013.

- Gil-Martínez A, Paris-Alemany A, López-de-Uralde-Villanueva I, et al. Management of pain in patients with temporomandibular disorder (TMD): challenges and solutions. J Pain Res. 2018;11:571–587.

- De Laat A, Stappaerts K, Papy S. Counseling and physical therapy as treatment for myofascial pain of the masticatory system. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17:42–49.

- Lindfors E, Arima T, Baad-Hansen L, et al. Jaw exercises in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders-an international modified delphi study. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2019;33(4):389–398–398.

- Physitrack. Available from: https://www.physitrack.com/?lang=nl.

- Bennell KL, Marshall CJ, Dobson F, et al. Does a web-based exercise programming system improve home exercise adherence for people with musculoskeletal conditions? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(10):850–858.

- van Egmond MA, Engelbert RHH, Klinkenbijl JHG, et al. Physiotherapy with telerehabilitation in patients with complicated postoperative recovery after esophageal cancer surgery: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e16056.

- Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, et al. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e152.

- Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SL, et al. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e52.

- O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(2):92–98.

- O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2007.

- O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:1147–1150.

- Caffery LJ, Martin-Khan M, Wade V. Mixed methods for telehealth research. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(9):764–769.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

- American Physical Therapy Association. Direct Access to Physical Therapy Sevices: Overview. http://www.apta.org/StateIssues/DirectAccess/Overview/.

- Gonzalez YM, Schiffman E, Gordon SM, et al. Development of a brief and effective temporomandibular disorder pain screening questionnaire: reliability and validity. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(10):1183–1191.

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28(1):6–27.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. [Internet]. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/.

- Harrison AL, Thorp JN, Ritzline PD. A proposed diagnostic classification of patients with temporomandibular disorders: implications for physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(3):182–197.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

- McGrath C, Palmgren PJ, Liljedahl M. Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Med Teach. 2019;41(9):1002–1006.

- Kahl C, Cleland JA. Visual analogue scale, numeric pain rating scale and the McGill pain questionnaire: an overview of psychometric properties. Phys Ther Rev. 2005;10(2):123–128.

- Bakken S, Grullon-Figueroa L, Izquierdo R, et al. Development, validation, and use of English and Spanish versions of the telemedicine satisfaction and usefulness questionnaire. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(6):660–667.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–124.

- Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(7):798–804.

- Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–158.

- Suzuki H, Aono S, Inoue S, et al. Clinically significant changes in pain along the pain intensity numerical rating scale in patients with chronic low back pain. PLOS One. 2020;15(3):e0229228.

- Zuidema R, Van Dulmen S, Sanden MVD, et al. Efficacy of a web-based self-management enhancing program for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: explorative randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(4):e12463.

- Varsi C, Nes LS, Kristjansdottir OB, et al. Implementation strategies to enhance the implementation of eHealth programs for patients with chronic illnesses: realist systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(9):e14255.

- Tenforde AS, Borgstrom H, Polich G, et al. Outpatient physical, occupational, and speech therapy synchronous telemedicine: a survey study of patient satisfaction with virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(11):977–981.

- de la Torre-Díez I, López-Coronado M, Vaca C, et al. Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness studies of telemedicine, electronic, and mobile health systems in the literature: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(2):81–85.

- Sangalli L, Fernandez-Vial D, Moreno-Hay I, et al. Telehealth increases access to brief behavioral interventions in orofacial pain clinic during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective study. Pain Med. 2022 Apr 8;23(4):799–806.

- Lam J, Svensson P, Alstergren P. Internet-based multimodal pain program with telephone support for adults with chronic temporomandibular disorder pain: randomized controlled pilot trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Oct 13;22(10):e22326.

- Kloek C, Bossen D, de Bakker DH, et al. Blended interventions to change behavior in patients with chronic somatic disorders: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(12):e418.

- Kloek CJJ, Bossen D, Spreeuwenberg PM, et al. Effectiveness of a blended physical therapist intervention in people with hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis, or both: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2018 Jul 1;98(7):560–570.

- Aggarwal VR, Fu Y, Main CJ, et al. The effectiveness of self‐management interventions in adults with chronic orofacial pain: a systematic review, meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Eur J Pain. 2019;23(5):849–865.

- Aggarwal VR, Wu J, Fox F, et al. Implementation of biopsychosocial supported self-management for chronic primary oro-facial pain including temporomandibular disorders: a theory, person and evidence-based approach. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48(10):1118–1128.

- Huprich SK, Hoban P, Boys A, et al. Healthy and maladaptive dependency and its relationship to pain management and perceptions in physical therapy patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20(4):508–514.

- Kinney M, Seider J, Beaty AF, et al. The impact of therapeutic alliance in physical therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;36(8):886–898.

- Emerick T, Alter B, Jarquin S, et al. Telemedicine for chronic pain in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Pain Med. 2020;21(9):1743–1748.

- Kloek CJJ, Janssen J, Veenhof C. Development of a checklist to assist physiotherapists in determination of patients’ suitability for a blended treatment. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(8):1051–1065.

- Vroom VH. Work and motivation. Wiley: New York; 1964.

- Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(8):1099–1110.

- Calner T, Isaksson G, Michaelson P. Physiotherapy treatment experiences of persons with persistent musculoskeletal pain: A qualitative study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019. 1–10.

- Linares-Fernández MT, La Touche R, Pardo-Montero J. Development and validation of the therapeutic alliance in physiotherapy questionnaire for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 March:104(3):524–531.

- Slade GD, Bair E, Greenspan JD, et al. Signs and symptoms of first-onset TMD and sociodemographic predictors of its development: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain. 2013 Dec;14(12 Suppl):T20-32.e1-3.

- Wang J, Barth J, Göttgens I, et al. An opportunity for patient-centered care: results from a secondary analysis of sex- and gender-based data in mobile health trials for chronic medical conditions. Maturitas. 2020;138:1–7.

- Goswami A, Dutta S, Goswami A, et al. Gender differences in technology usage—a literature review. OJBM. 2016;04(01):51–59.

Appendix 1.

Topic guides for patients and orofacial physical therapists

Topic guide for patients with temporomandibular disorder:

Topic guide for orofacial physical therapists: