Abstract

Purpose

To offer guidance for future welfare technology research, this review provides an overview of current knowledge gaps and research needs as reported in primary scientific studies addressing the implementation of welfare technology for older people, people with disabilities and informal caregivers.

Materials and methods

This paper conducted a state-of-the-art review based on systematic searches in 11 databases followed by a descriptive qualitative analysis of 21 selected articles.

Results

Knowledge gaps and research needs were identified concerning two categories: research designs and populations and focus of research. The articles reported needs for comparative studies, longitudinal studies, and demonstration trials as well as the development of co-design processes involving technology users. They also called for studies applying a social system theory approach, involving healthy and frail older adults, representative samples of users within and across countries, informal and formal caregivers, inter-and multidisciplinary teams, and care organizations. Moreover, there are reported needs for studies of acquirement, adoption and acceptance of welfare technology, attitudes, beliefs, and context related to welfare technology, caregiver perspectives on welfare technology, services to provide welfare technology and welfare technology itself.

Conclusions

There are considerable knowledge gaps and research needs concerning the implementation of welfare technology. They relate not only to the research focus but also to research designs, a social system theory approach and study populations.

When planning for the implementation of welfare technology for older people and persons with disabilities, it is important to be aware that necessary evidence and guidance may not always be available in peer-reviewed scientific literature but considerable knowledge gaps and research needs remain.

Actors implementing welfare technology are encouraged to include researchers in their projects to study, document and report experiences made, and thereby contribute to building the evidence base and supporting evidence-based implementation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

There is an increasing interest in utilizing new digital technologies, welfare technology, to address the double demographic challenge of a growing proportion of older people and decreasing proportion of people of working age. Despite its potential to improve the quality of life of people with functional limitations of all ages and to reduce societal costs, the large-scale implementation of welfare technology has been slow and narrow in scope [Citation1–5]. Reported implementation barriers include high costs, lack of competence, lack of knowledge about available solutions, differences between sectors, technical problems, legal complications, resistance to change among personnel, limited research, and weak analyses of needs. Further, identified challenges for implementation relate to financing, organizational issues, communication and cooperation across stakeholders, evaluation, IT infrastructure, service, support, logistics and reacquisition [Citation6–9].

There is no official definition for welfare technology, but its purpose, according to the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, is to maintain or increase safety, activity, participation, or independence for individuals with disabilities or those who are at risk for disability [Citation10]. The concept welfare technology is newer than the phenomenon of technology use in healthcare and social care, and there are overlapping concepts that are used differently, for example, eHealth, teleHealth, telecare, and telemedicine. However, there are limitations of the above definition of welfare technology. As pointed out by Frennert [Citation11], one limitation is that the definition does not include social and organizational aspects, structures and how healthcare and social care practices are affected by welfare technology. Frennert and Baudin [Citation12] have also explored the welfare technology concept in Swedish municipal elderly care. They found that it was recognized as an enabler, a simplifier and as a support for both patients and professional care givers, which corresponds to the definition of welfare technology.

Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) embraced the normalization of technology as a part of everyday life by launching a new initiative: Digital and Assistive Technologies for Ageing (DATA). The DATA initiative “seeks to encourage the development, synthesis, and use of solutions that promote access to affordable, quality, digital and assistive technologies for people with impairment or decline in physical or mental capacity, with a particular focus on older people” [Citation13]. The digital technology component in the WHO DATA initiative resembles what is defined as welfare technology by the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, i.e., digital technology that aims at maintaining and increasing safety, activity, participation, or independence for a person who has or is at an increased risk of impairment [Citation10]. The Swedish definition of welfare technology is narrower than the broad Nordic description of welfare technology as technology that improves the lives of those who need it [Citation1].

Using the Swedish definition of welfare technology, the purpose of this review is to offer guidance for future welfare technology research and thereby contribute to mitigating barriers and challenges related to lack of knowledge regarding the implementation of welfare technology. Its objective is therefore to provide an overview of current knowledge gaps and research needs as reported in primary scientific studies that addresses the implementation of welfare technology for older people, people with disabilities and informal caregivers.

Method

This study conducted a state-of-the-art review with a focus on highlighting areas in need of further research [Citation14]. Applicable methodological principles of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Citation15] were followed, particularly regarding the search strategy, which involved several databases and the use of both free-text and controlled vocabulary. An a priori protocol that includes this review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020170051).

Data sources and searches

Eleven electronic databases (see ) were searched on 16 March 2020, by an academic librarian (author SLS) using a comprehensive search strategy that was developed by all authors. Divided into three categories, the search terms included both free-text and controlled vocabulary. The first category related to population: older persons, people with disabilities and informal caregivers (#1–3 in ). The second category focussed on intervention (#5 in ): welfare technology and related terms, such as smart home and environmental control. The third category concerned outcomes in terms of implementation (#6 in ), i.e., activities designed to put something into practice. The Boolean operator AND was used to combine the three primary categories of search terms. To exclude studies regarding children, terms relating to children and youths were omitted using the Boolean operator NOT (#4, 7–9 in ).

Table 1. Number of identified records by database.

Table 2. Search strategy used in Scopus (limitations are specific to this database).

As the term welfare technology was introduced in 2007, the searches were limited to peer-reviewed material published from 1 January 2007 until the date of the search. In the databases, the Web of Science and Scopus, further limits regarding subject areas were applied, and document types were limited to articles, reviews and conference or proceeding papers. The reason for this was to reduce records of technically focussed research where implementation has a different meaning. In the Web of Science, early access documents were included. No language or study design restrictions were applied to the search.

Study selection

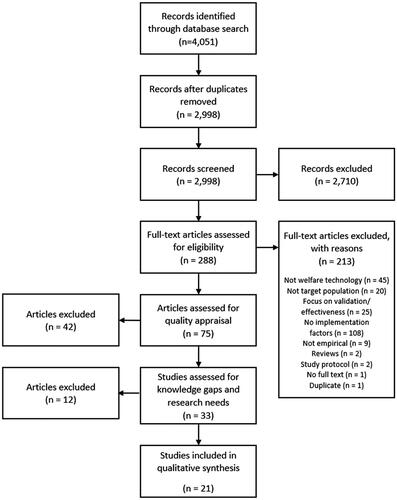

A summary of the study selection process is shown in an expanded PRISMA flowchart in . The database searches identified a total of 4,051 records for potential inclusion. These records were downloaded to the reference management programme EndNote, and duplicates were removed by an academic librarian (author SLS) by applying Bramer’s [Citation16] de-duplication method, which resulted in the exclusion of 1,053 duplicates. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 2,988 titles were screened against the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1. Expanded PRISMA flow diagram.

This review included quantitative and qualitative empirical studies that assessed the implementation of welfare technology from the perspectives of older people, people with disabilities or informal caregivers and had been reported in peer-reviewed articles and published in scientific journals or conference proceedings. Technical reports limited to describing or evaluating features of welfare technology were excluded.

Authors JB and VZ screened the titles and abstracts, and full-text assessment was undertaken by authors JB, CG and VZ. Following full-text assessment, the quality of the articles was appraised by authors JB, CG and VZ using the MMAT mixed methods appraisal tool [Citation17]. MMAT was designed to appraise the methodological quality of five categories of studies: randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, qualitative studies, and mixed methods studies. The appraisal of the studies resulted in a rating of methodological quality from 0 to 5, where studies rated 3 to 5 were included (N = 33).

Any disagreements between the three researchers during this process were discussed until consensus was reached. Reasons for exclusion were recorded.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed that included the aim and design of the study, sample characteristics, type of welfare technology, barriers to and facilitators of implementation and reported knowledge gaps and research needs. Details about the articles were also extracted, including publication year and country of study. Among the 33 included articles, 21 reported knowledge gaps and research needs. Thus, the analysis in this review is based on knowledge gaps and research needs reported in these 21 articles.

Synthesis

A qualitative descriptive analysis [Citation18] approach was conducted. The first stage was line-by-line coding, as each sentence was read to identify underpinning themes about knowledge gaps and research needs as reported in primary scientific studies addressing the implementation of welfare technology for older people, people with disabilities and informal caregivers. These were labelled with a code. The identified codes were then organized into preliminary categories. This stage was conducted by VZ and discussed among JB, CG and VZ. They interpretated, abstracted and conceptualized the preliminary categories into two main categories, of which one consisted of five sub-categories. An example of the coding and categorization is given in .

Table 3. Example of coding and categorization.

Results

The aims or research questions of the included studies, and the knowledge gaps and research needs they report are compiled in . The applied method resulted in two emerging descriptive categories of knowledge gaps and research needs relating to the implementation of welfare technology for older people, people with disabilities, and informal caregivers. The main categories are: (i) research designs and populations, and (ii) focus of research.

Table 4. Aim or research questions of included studies and reported knowledge gaps and research needs.

Research designs and populations

The first main category explores a broad research gap regarding research designs, covering requests for longitudinal, larger, comparative, and international studies, as well as smaller studies comparing different groups, demonstration trials and a focus on patients and families. Further settings and samples are called for to increase diversity and include equality integrated perspectives. In terms of research designs and populations, the included articles expressed the need for systematic literature reviews of socio-technological challenges from the perspectives of community, organization, and individuals [Citation34]. They also called for demonstration trials with strategies responsive to multi-implementation barriers [Citation36] and the development of co-design processes involving users [Citation31]. Comparisons of opinions and attitudes among older adults who are healthy, and frail were also requested [Citation33]. The articles reported the need for studies with samples within and across countries, cultures, and health-care systems [Citation25,Citation27]. Studies of informal caregivers [Citation24], spouses and relatives [Citation25], and patients and families as end users of welfare technology [Citation3] across age groups [Citation30] were called for. Furthermore, there were reported needs for research on care organization [Citation25], diverse groups of healthcare workers [Citation36] and inter- and multidisciplinary teams representing computer science and engineering, psychology, neuroscience, social work, nurses, physical therapy, speech therapy, physicians, and health information technology experts [Citation21]. In addition to the research designs and methods mentioned above, the reviewed literature expressed a need for systematic literature reviews [Citation34], demonstration trials [Citation36], comparative studies [Citation24,Citation33], and longitudinal studies [Citation22,Citation23].

Focus of research

The included articles called for studies of specific phenomena. The identified knowledge gaps and research needs were categorized into five interlinked and partly overlapping sub-categories. These sub-categories include: (i) acquirement, adoption and acceptance; (ii) attitudes, beliefs and context; (iii) caregiver perspectives; (iv) services; and (v) technology.

The main category covers a broad variety of research perspectives. The research gap includes individual perspectives, including experiences of patients, relatives, and staff, organizational (care providers’) perspectives, for example acquirement, services, and organizational infrastructure issues, as well as a societal perspective on challenges in healthcare systems and technology related barriers. This is interpreted as a call for a social system theory approach with micro-, meso- and macro-level perspectives on research about implementation of welfare technology.

Acquirement, adoption and acceptance

The articles report a need for research about mechanisms that impede acquiring welfare technology. This includes why acquirement processes are aborted or not started, and how cultural aspects and the organization of the local and national healthcare system influence technology acquirement [Citation33]. There is also a need for a deeper understanding of factors that influence perceptions of need [Citation19] and differences in users’ needs between countries [Citation27].

Other knowledge gaps and research needs include drivers and barriers towards acceptance [Citation24] and differences in acceptance between countries, healthcare systems and cultures [Citation27]. Moreover, there is a need for studies on potential facilitators to promote adoption [Citation28], including best practices for practitioners [Citation35], and emotional involvement in the adoption process [Citation21,Citation25]. There is also a need to study how older adults facing challenges in independent living evaluate and decide between various options [Citation23]. Similarly, there is a need for studies on barriers to adoption among people with visual impairments and how visual impairment could determine awareness and decisions to adopt assistive technology [Citation30]. Knowledge about longitudinal mechanisms that influence the use of technology is also called for, as it will help in understanding the dynamics, interplay and relative importance of relevant factors [Citation23]. In particular, studies of the experiences of persons with dementia in later stages of the disease have been requested [Citation26].

Attitudes, beliefs and context

The literature has issued a general call for studies to address barriers related to person and context [Citation21,Citation28]. More specific research needs include comparisons of opinions and attitudes among healthy and frail older adults [Citation33]. There are also needs for studies to understand personal, ideological, social and cultural concerns and possible mechanisms of addressing them [Citation32]. Furthermore, studies to explore how changes in personal and social contexts affect older adults’ attitudes and beliefs with respect to using technology while ageing in place have been called for [Citation23]. This includes a need for knowledge about the size and nature of older adults’ social networks [Citation33].

The literature has reported a need to address gaps in knowledge about ethical implications for individuals and societies [Citation20]. In particular, studies on ethical principles of autonomy and rights to self-determination [Citation21], and the relationship between safety and perceived intrusion of privacy [Citation27] have been requested. Moreover, studies of the role of culture, reflecting beliefs and being an integral part of the context, have been requested, including the role of culture in design, marketing, acquirement and adoption [Citation21,Citation25].

Caregiver perspectives

The reviewed articles expressed a need for studies on caregiver perspectives [Citation21], including those of patients and families as end users of welfare technology [Citation3] and different healthcare workers [Citation36]. Specific calls have been made for comparisons of care tasks and task pressure among different groups of informal caregivers, and research on how contextual factors, such as culture, age and personal innovativeness, affect the perception of welfare technology among informal caregivers [Citation24]. There is also a reported need for integrating perspectives of spouses and relatives of older adults, as well as care organizations they interact with, on the influences and motivation for providing resources for acquiring technology [Citation25]. Furthermore, among informal caregivers, there is a gap in knowledge about the male perspective [Citation24].

Services

Knowledge gaps have been identified concerning the meaning of drivers and barriers when technologies are integrated in everyday care practices [Citation24]. There is also a reported knowledge gap about strategies that are responsive to multiple implementation barriers faced by lower resource agencies [Citation36]. Another area where more knowledge has been called for is how the overall service process could be developed to provide stakeholders with up-to-date information on the latest technologies and their applications [Citation29]. Welfare technology costs are also an area that requires exploration [Citation21], particularly the multiple challenges in technology-related implementation faced by small-and low-budget agencies [Citation36].

Technology

Besides the general need for research about technology-related barriers [Citation28], there is a need for studies on features, functionality, human factors engineering and costs [Citation21]. Moreover, research is needed about the development of technical solutions that are sophisticated, safe, personalizable, non-stigmatizing [Citation37] and based on potential users’ perceptions and experiences of the design prior to implementation [Citation38]. However, before embarking on developing new solutions, it is necessary to identify and priorities problems that can be addressed [Citation31]. Finally, reviews of socio-technical challenges in relation to the individual, organization and community levels have been called for [Citation34].

Discussion

The results of the analysis of the data extracted from the 21 empirical research articles included in the review form a comprehensive understanding that knowledge gaps and research needs exist in areas important for improved implementation of welfare technology for older people, people with disabilities and informal caregivers. Two categories of knowledge gaps and research needs emerge, namely, research designs and populations, and focus of research. Needs were reported for comparative studies, demonstration trials, studies employing longitudinal designs, systematic reviews, and developing co-design processes. Furthermore, the literature called for studies within and across countries that involve older people and people with disabilities, informal and formal caregivers, other professions, and care organizations. Sometimes, populations were specified together with particular research designs or methods. The reported knowledge gaps cover a broad spectrum of issues related to the implementation of welfare technology. They translate into the need for studies on barriers and facilitators of acquirement, adoption, and acceptance of welfare technology as well as studies of the roles of attitudes, beliefs, and context for the implementation of welfare technology, including ethics and culture. Moreover, the need was expressed for studies of informal and formal caregiver perspectives on welfare technology, services for the provision of welfare technology and welfare technology itself. This variety of calls for research in implementation of welfare technology depicture a very broad list of different perspectives illustrating an emerging interdisciplinary field of research. Aaen [Citation39] reported similar findings in a review exploring competing concerns in managing the critical transition from small-scale welfare technology inventions to large-scale implementation. The findings were presented in eight themes using a system theory structure divided into user level, organizational level, market level and policy level. Similarly, Cunningham and O’Reilly [Citation40] call for a social system theory approach in a research agenda about technology transition, which implementation of welfare technology is part of. They propose to evaluate countries and make cross-country comparisons at macro-level, followed by focussing on technology transition at meso level. And, at micro level, they suggest research having individual perspectives focussing behaviours and actions.

This review identified significant knowledge gaps and needs for research in areas important for improved and large-scale implementation of welfare technology, which has been slow and faced numerous barriers [Citation1–9]. Addressing these gaps and needs will generate knowledge that facilitates the successful implementation of welfare technology. Particularly, interdisciplinary research that generates high-quality generalizable evidence is much needed in this field, including longitudinal studies of the effects of using welfare technology for individuals, informal and formal caregivers, organizations, and society.

The findings of this review resonate with a global priority research agenda for improving access to assistive technology, which includes welfare technology. The agenda has identified five thematic areas in need of urgent attention. Among others, the thematic areas cover different technical solutions and their impacts, implementation in terms of policies, systems, models and practices and human resource development, all of which are relevant to welfare technology and its implementation [Citation41].

This study was a state- of-the art review, a method having both strengths and limitations. The aim with the method was to address a current matter. The method offers new perspectives and points out areas for further research and research opportunities for contemporary knowledge gaps and needed research [Citation14]. The method made it possible to present an overview of current knowledge gaps and research needs as reported in primary scientific studies addressing the implementation of welfare technology for older people, people with disabilities and informal caregivers. Considering that welfare technology and its implementation is an emerging interdisciplinary field, it was expected that the database searches would yield a limited number of relevant research studies. Although the search strategy resulted in many hits, many studies were excluded due to the use of concepts not fitting the present study’s inclusion criteria and the conceptualization of welfare technology. A critical phase in a review study, is always the search process as the vital part of the study. In the present study, by using the concept welfare technology (applied as the phrase “welfare technology), made the search process problematic. As the concept welfare technology is mainly used within the Nordic countries, comparable or complementary concepts were included in the search process. Most results were retrieved from the more technology-specific terms, such as “alarm” or “smart home*,” while articles containing the phrase “welfare technology” were found only in studies originating from the Nordic countries. To prevent too many hits for this review, generic terms, such as “assistive technology”, were not used in the search strategy. However, we did use more specific terms, including “digital assistive” and “intelligent assistive”. By using more collective concepts, there is a risk that relevant studies using specific terms have been missed.

Conclusion

This review offers an overview of current knowledge gaps and research needs regarding the implementation of welfare technology for older people, people with disabilities and informal caregivers. There are considerable knowledge gaps and research needs related not only to the focus of research but also to research designs and study populations. Addressing these gaps and needs is important for improving the implementation of welfare technology. A research agenda with interdisciplinary research perspectives, and the application of micro, meso and macro levels with social system theory approaches, appear promising when responding to identified knowledge gaps and research needs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Welfare technology [Internet]. Nordic Welfare Centre. 2019; [cited 2021 Dec 12]. Available from: https://nordicwelfare.org/en/welfare-policy/welfare-technology/2019.

- Frennert S, Östlund B. Narrative review: welfare technologies in eldercare. NJSTS. 2018;6(1):21–34.

- Nilsen ER, Dugstad J, Eide H, et al. Exploring resistance to implementation of welfare technology in municipal healthcare services – a longitudinal case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):657.

- Nordic Centre for Welfare and Social Issues. Welfare technology and chronic illnesses, unleashing the hidden potential! Nordic Think Tank for welfare technology. Stockholm: Nordic Centre for Welfare and Social Issues; 2016.

- Nordic Welfare Centre. Welfare technology. Toolbox. Stockholm: Nordic Welfare Centre; 2017.

- Nordic Welfare Centre. How can welfare technology work better across sectors in the nordic welfare model? Nordic Think Tank for welfare technology. Stockholm: Nordic Welfare Centre; 2018.

- Nordic Centre for Welfare and Social Issues. Making implementation easier. Nordic Think Tank for welfare technology. Stockholm: Nordic Centre for Welfare and Social Issues; 2015.

- Dahlberg Å. Samhällsekonomiska nordiska studier inom välfärdsområdet. En kartläggning [Socio-economic Nordic studies in the welfare area. A mapping study]. Stockholm: Hjälpmedelsinstitutet; 2014.

- Zander V, Gustafsson C, Landerdahl Stridsberg S, et al. Implementation of welfare technology: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2021;2021:1–16.

- Termbanken. Välfärdsteknik [welfare technology] [Internet]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen. 2015; [cited 2021 Dec 12]. Available from: http://termbank.socialstyrelsen.se/showterm.php?fTid=798.

- Frennert S. Approaches to welfare technology in municipal eldercare. J Technol Hum Serv. 2020;38(3):226–246.

- Frennert S, Baudin K. The concept of welfare technology in Swedish municipal eldercare. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(9):1220–1227.

- Khasnabis C, Holloway C, MacLachlan M. The digital and assistive technologies for ageing initiative: learning from the GATE initiative. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2020;1(3):e94–e5.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. updated September 2020. Cochrane, 2020. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, et al. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–243.

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552). Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada; 2018.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340.

- Courtney KL. Privacy and senior willingness to adopt smart home information technology in residential care facilities. Methods Inf Med. 2008;47(1):76–81.

- Nakrem S, Solbjor M, Nilstad Pettersen I, et al. Care relationships at stake? Home healthcare professionals’ experiences with digital medicine dispensers – a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):26.

- Fritz RL, Corbett CL, Vandermause R, et al. The influence of culture on older adults’ adoption of smart home monitoring. Gerontechnology. 2016;14(3):146.

- Bäccman C, Bergkvist L, Kristensson P. Elderly and care personnel’s user experiences of a robotic shower. JET. 2020;14(1):1–13.

- Peek STM, Luijkx KG, Rijnaard MD, et al. Older adults’ reasons for using technology while aging in place. Gerontol. 2016;62(2):226–237.

- Jaschinski C, Allouch SB. Listening to the ones who care: exploring the perceptions of informal caregivers towards ambient assisted living applications. J Ambient Intell Human Comput. 2019;10(2):761–778.

- Peek STM, Luijkx KG, Vrijhoef HJM, et al. Origins and consequences of technology acquirement by independent-living seniors: towards an integrative model. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):189.

- Olsson A, Engström M, Lampic C, et al. A passive positioning alarm used by persons with dementia and their spouses–a qualitative intervention study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:11.

- Van Heek J, Himmel S, Ziefle M. editors. Helpful but spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems contrasting user groups with focus on disabilities and care needs. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2017); 2017 Apr. Setúbal, Portugal: Scitepress; 2017. p. 78–90.

- Cajita MI, Hodgson NA, Wai Lam K, et al. Facilitators of and barriers to mHealth adoption in older adults with heart failure. Comput Inform Nurs. 2018;36(8):376–382.

- Riikonen M, Paavilainen E, Salo H. Factors supporting the use of technology in daily life of home-living people with dementia. Technol Disabil. 2013;25(4):233–243.

- Okonji PE, Ogwezzy DC. Awareness and barriers to adoption of assistive technologies among visually impaired people in Nigeria. Assist Technol. 2019;31(4):209–219.

- Wang S, Bolling K, Mao W, et al. Technology to support aging in place: older adults’ perspectives. Healthcare. 2019;7(2):60.

- Wangmo T, Lipps M, Kressig RW, et al. Ethical concerns with the use of intelligent assistive technology: findings from a qualitative study with professional stakeholders. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):98.

- Wu YH, Damnée S, Kerhervé H, et al. Bridging the digital divide in older adults: a study from an initiative to inform older adults about new technologies. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:193–200.

- Kolkowska E, Avatare Nöu A, Sjolinder M, et al. Socio-technical challenges in implementation of monitoring technologies in elderly care. In: Zhou J, Salvendy G, editors. Human aspects of it for the aged population: healthy and active aging, ITAP 2016, Pt II. Lecture notes in computer science 9755. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 45–56.

- Arthanat S, Wilcox J, Macuch M. Profiles and predictors of smart home technology adoption by older adults. OTJR. 2019;39(4):247–256.

- Ramsey A, Lord S, Torrey J, et al. Paving the way to successful implementation: identifying key barriers to use of technology-based therapeutic tools for behavioral health care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43(1):54–70.

- Bentley CL, Powell LA, Orrell A, et al. Addressing design and suitability barriers to telecare use: Has anything changed? Technol Disabil. 2014;26(4):221–235.

- Olsson A, Skovdahl K, Engström M. Using diffusion of innovation theory to describe perceptions of a passive positioning alarm among persons with mild dementia: a repeated interview study biology and technology. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:3.

- Jon A. Competing concerns in welfare technology innovation: a systematic literature review. 2019. 10th Scandinavian Conference on Information Systems. 3.https://aisel.aisnet.org/scis2019/3.

- Cunningham JA, O’Reilly P. Macro, meso and micro perspectives of technology transfer. J Technol Transf. 2018;43(3):545–557.

- WHO. Global priority research agenda for improving access to high-quality affordable assistive technology. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.