Abstract

Purpose

We examine the use of a custom iPad application, the Rehab Portal, to provide clients in an inpatient brain injury rehabilitation service with access to short videos where clinicians—or the clients themselves—discuss their current rehabilitation goals.

Materials and Methods

We developed an initial version of the Rehab Portal app based on our previous co-design with service users, their families, and clinicians. This was examined in a field trial with a series of six clients over the course of their stays in inpatient rehabilitation, collecting quantitative data on clinician and client engagement with the Rehab Portal, alongside a thematic analysis of qualitative interviews with clients and clinicians at the point of discharge.

Results

Engagement with the platform was high for two clients while it was limited with four more. In our thematic analysis we discuss how introduction of the Rehab Portal disrupted practice, changing how things are done, causing deviation from usual routines, adding burden, and threatening professional integrity. At the same time, where it worked well it led to a repositioning of goal planning away from being clinician directed and towards an ongoing, dynamic collaboration between clinicians, clients and their families. Finally, in some cases we identified a reverting to the status quo, with client demotivation having an unexpected impact on clinician behaviour leading to the process being abandoned.

Conclusions

The current findings do not provide wholesale support for this approach, yet we continue to feel that approaches that support clinician-client communication using asynchronous video may offer considerable future value and are worthy of further investigation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

The use of a novel technique to communicate rehabilitation goals via video disrupted practice, changed how things are done, caused deviation from usual routines, added burden, and threatened professional integrity for clinicians.

Where it worked well it led to a repositioning of goal planning away from being clinician-directed and towards an ongoing, dynamic collaboration between clinicians, clients and their families.

Approaches that support clinician-client communication using asynchronous video may offer considerable future value and are worthy of further investigation.

Field trial of a video portal for inpatient brain injury rehabilitation goals

Introduction

Planning and setting goals is an important component of brain injury rehabilitation[Citation1–5]. This process involves a client and their family or supporters though is usually directed by clinicians, even when a client-centred approach may be the intention [Citation1,Citation2,Citation6–8]. It focuses on the meaning behind making adjustments to new circumstances and the reasons for them [Citation9]. A person’s former way of life and their previously held life goals may no longer be possible after brain injury. Life goals, which contribute to a person’s purpose and wellbeing, may need to be re-assessed, in conjunction with setting practical and technical goals, to facilitate adjustment to their new situation [Citation3,Citation10].

Levack et al. [Citation5] identified four major purposes for goal planning in rehabilitation. The first of these is especially relevant in this study: improving rehabilitation outcomes through the mechanism of using goals to influence conscious motivation, and thus improved engagement in rehabilitation [Citation5,Citation11,Citation12]. However, goal setting in rehabilitation presents particular challenges for clients with brain injuries. Clients are likely to be experiencing disorientation, confusion, and memory issues [Citation13] Memory impairment is a significant obstruction in return to previous levels of functioning for a person with brain injury [Citation14]. Everyday tasks such as self-care, managing medications, and cooking become difficult with reduced facility to plan ahead and organise previously routine activities [Citation15]. Communication can be affected by slow processing of information and poor attention, with a reduced ability to self-regulate behaviour [Citation16]. Due to reduced cognitive functioning in all of these and many other areas, there may be a reduction in a person’s motivation to participate in their own rehabilitation overall [Citation13]. In particular, all of these areas of impairment have the potential to make it more difficult to set goals for life beyond the immediate setting of the rehabilitation centre [Citation17]. Along with reduced self-awareness, these effects are likely to lead to sub-optimal rehabilitation outcomes [Citation13,Citation18].

Smartphones and other digital technologies have been recognised since their development as being potentially valuable for people with memory impairment, due to their ability to store data, send notifications and provide prompts and guides using multiple modalities [Citation19]. In a study by Wong et al. for instance, people with traumatic brain injury found smartphones acceptable and accessible and could use various apps, but they were found to be especially useful as a means of memory aid [Citation20]. In their study of memory aids and strategies among people with acquired brain injury, Jamieson et al. found that all participants included memory function as a rehabilitation goal or stated that they had memory difficulties. The authors confirmed that an important advantage of technological ways of assisting memory was the active prompting ability [Citation14]. Evald [Citation21] also reported that visual and audible prompts or notifications from smartphones to patients with traumatic brain injury were particularly helpful as reminders.

While such technology has been used as a direct treatment component, as a cognitive prosthetic tool, there may also be (so far untapped) potential to apply technologies such as these to the challenges outlined above in facilitating goal awareness and goal setting processes in formal brain injury rehabilitation services. Providing clients with a tool that gives them on-demand access to information about why they are in rehabilitation, what their goals are [Citation22,Citation23] and what they are currently working on, would be novel and has potential to influence and stimulate motivation, increase engagement [Citation24], reduce premature discharge, and improve outcomes [Citation23].

The overall aim of our programme of research was to examine the utility and acceptability of providing access to such videos via a custom app on a touchscreen tablet, the “Rehab Portal”, that would be available to clients to view whenever they wished to access it, independent of clinician availability. We previously reported on the first phase of that programme, the process of co-design and usability testing of this custom Rehab Portal app with service users, their families, and clinicians (Authors, Under Review). The portal would present them with videos outlining the focus of their current rehabilitation where clinicians—or the client themselves—was presented discussing their current rehabilitation goals and linking these to valued life roles (Why), to rehabilitation activities (What), and to what they are working on with the clinicians in the current week (How). On the basis of that work, our team moved to the current study: an initial, small scale, clinical pilot of the app in the same inpatient rehabilitation setting that the original co-design and usability testing had occurred—a ‘field trial’ of the app in use embedded within the actual process of delivering rehabilitation to clients while they were resident in the rehabilitation centre.

This work is exploring whether awareness of rehabilitation goals, motivation, and client satisfaction in inpatient brain injury rehabilitation could be enhanced by access to videos on their rehabilitation goals. It was our intention that the Rehab Portal app would draw on goals already being set with clients and their families in the course of routine goal setting processes at the rehabilitation service. The app was conceived of as a new platform for communicating information that was already being created in ‘business as usual’ activities. Likewise, we assumed clinicians would continue to revise and update client goals regularly during rehabilitation, and would record these revisions in the app. We were also aware, however, that it was possible that clinician goal-setting behaviour might be influenced by the introduction of the app. We were particularly interested to understand client responses to having access to video information about their rehabilitation goals. We envisaged clients accessing this information independently of their clinicians enabling frequent engagement with rehabilitation goals. We were also interested to discover if the authentication mechanism was accessible for clients with brain injury. Rather than targeting increased declarative awareness of current rehabilitation goals, we were most interested in the possibility of increasing subjective engagement in the rehabilitation process itself. Overall, we hypothesised that if clients were provided with direct unsupervised access to videos in which their clinicians explained the focus of their rehabilitation and their current goals, this could enhance the rehabilitation process.

Materials and methods

Setting

This app pilot trial took place in the ABI Rehabilitation post-acute inpatient rehabilitation service in Auckland, New Zealand, where we also carried out the co-design stage of the research. This app pilot took place in a specialist post-acute brain injury rehabilitation setting where an intensive in-patient rehabilitation program is offered to individuals who have suffered moderate to severe traumatic brain injury and other acquired brain injuries such as stroke. Clients range from those who are minimally conscious to those undergoing community re-integration prior to discharge. Generally, clients are engaged in three hours of face-to-face therapy time per day with Allied Health professionals and outside of these hours have protocols by which daily tasks are completed in a consistent way to incorporate rehabilitation progress into nursing and health care assistant activities. Self-directed and family directed rehabilitation is also encouraged outside of formal therapy hours. Clients are provided with their own private rooms arranged within houses that consist of 6-8 rooms plus shared living spaces.

Equipment

Rehab Portal app

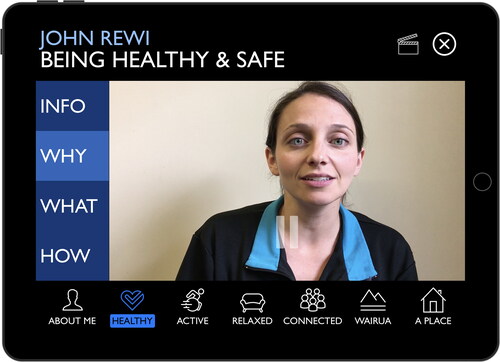

The Rehab Portal app is an iPad app developed in this research programme (see ). All design and coding were completed by DB. In brief, after a user is authenticated, the app presents simple written orientation information to a client about their brain injury. Following this, clients are presented with videos in up to six goal areas based on goal areas that ABI Rehabilitation were already using at project outset including: being healthy and safe, being active, being relaxed, being connected, wairua (spirituality), and having a place to call home. These were simplified for the app. See for an example.

Figure 1. Goal screen in the Rehab Portal app. Screenshot of the Rehab Portal iPad app, headed “John Rewi: Being Healthy & Safe”. A video frame of a female clinician fills the main central portion of the screen. Tabs on the left side are labelled ‘Info’, ‘Why’, ‘What’ and ‘How’, while controls across the bottom are labelled ‘About Me’, ‘Healthy’, ‘Active’, ‘Relaxed’, ‘Connected’, ‘Wairua’ (which is Māori for Spirituality), and ‘A Place’.

Within each goal area, clinicians working with clients would record a set of three videos—Why, What, and How:

“Why are we working on this?” (designed to be participation- and role-focussed),

“What are we working on to achieve this in the course of your stay here?”, and

“How are we working on this area currently?”.

This structure was based on the existing goal setting structure already in use in the inpatient rehabilitation service, which itself was based on the rehabilitation goal setting literature. To follow good practice, this structure required a focus on the client’s valued life roles beyond the immediate rehabilitation setting [Citation3,Citation17,Citation25]—a ‘horizon-focussed’ approach to goal setting (Babbage, personal communication, cited in [Citation26]).

The authors do not have a financial interest in the app and report there are no competing interests to declare.

Hardware

Apple iPads were configured with the current hardware and software version at the time of data collection, specifically iPad Air 2 devices running current iOS versions at each point in data collection (i.e., iOS 10.2 when data collection started in 2017). We debated issuing individual iPads to specific clients versus having one shared iPad installed in client ‘houses’ on site (which housed six to eight clients) with multiple clients accessing their own Rehab Portal data on the house iPad. The clinical team expressed concerns regarding privacy if audio files were playing in shared living spaces. Headphones were ruled out due to concerns about motor functioning, plus issues of headphones and iPads being left in insecure places [a concern previously expressed in previous studies, (e.g., [Citation27]). Therefore, for this trial each client had the iPad installed in their own bedroom. iPads were mounted on the wall by a Joy Factory MagConnect Wall/Counter Mount, with a Lockdown Secure Holder with Cable Lock for security.

A Xiaomi MiFit 2 Bluetooth wristband was supplied to each participant (beginning part-way through the trial with the first client) to wear for the duration of the project. At the conclusion of the trial, the client could keep the wristband as an activity tracker if they wished to.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained through the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (16/189) and the project was supported by the research committee of ABI Rehabilitation.

Recruitment

Participants with brain injury

Client participants had sustained a severe brain injury and were in inpatient care at ABI Rehabilitation at the time of recruitment. The severity of their brain injury was classified by Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) measurement at the time of injury or presentation to the Emergency Department (if recorded), length of time in Post Traumatic Amnesia (PTA) if traumatic injury, and clinical assessment (See . All names used in this table and throughout the manuscript are pseudonyms.) Recruitment was carried out by two senior clinicians at ABI Rehabilitation, who were also members of the research team (MVS and JA), in consultation with other senior members of the clinical team. Clients were invited to participate if they were over 18 years of age and the clinical team considered they were at a stage in their rehabilitation where they could manage using an iPad and could potentially master the concept and skills involved. The project was explained to the client; if the client was interested in participating, their consent was obtained at a subsequent meeting before installing an iPad in the client’s room.

Table 1. Client demographics.

Clinician participants

Clinicians were invited to participate if one of the clients in their care was also recruited into the study. Commonly there were three therapists attending a client who had been recruited. Ten clinicians involved with each recruited client were given participant information and consented to participate. They comprised three Occupational Therapists, three Physiotherapists and four Speech Language Therapists, on average 6.5 years post training. Seven clinicians held a post-graduate qualification. Nine were female and ages ranged from 25 to 60 years.

Clinician training and supports

Training supports were provided to clinicians who were engaging with the portal. This included direct, one-to-one support from members of the research team—both the on-site clinical leaders (MvS, JA) and two team members who visited the site on a weekly or fortnightly basis to collect data, provide software support and updates, and support clinicians and the project as required (DB, JD). During the app trial clinicians were also provided with two in-service training sessions of one hour each, one by DB and NK, and one by MVS and JA. These two sessions were scheduled as part of an ongoing programme of regular in-service training run for all clinicians in the service.

The Rehab Portal was presented to clinical staff as being a platform for regularly updating the client on their current rehabilitation goals. During training we discussed that videos might, for instance, be updated weekly. We suggested it was likely that the Why videos would not be updated often and might remain the same throughout an inpatient stay. Likewise, it was possible that the What videos in each goal area would also not change every week. However, we suggested the content for the How videos in each goal area would be likely to change frequently, and thus it would be helpful to make frequent, perhaps weekly, updates in this area. This would ensure that video content was current to maintain client interest even if the general focus of the work had not changed much. Clinicians were given discretion about how they would record these videos—either recording the videos themselves, with their clients, or of their clients, based on what was practical and they felt would be most useful for the specific client.

Data collection and planned analyses

We tracked when videos were recorded and updated across the six goal areas by clinicians as a proxy indication of clinician engagement with the Rehab Portal. Client interactions with the Rehab Portal were also automatically logged by the software to provide a baseline of the frequency and extent of use that each client made of the system. The logging distinguished clinician or researcher interactions from client interactions, authenticating individual users by PIN login, or by Bluetooth wristband access for clients if they were using this option.

At the conclusion of their trial period with the app, where possible a semi-structured interview was conducted with each client to explore their understanding and perspective on the Rehab Portal’s utility and value. Where possible, this occurred just prior to discharge. In one case (Joe), the interview was conducted shortly after discharge, and in another (Kate) an interview was not conducted as the client was discharged over a weekend and unable to be interviewed by the research team.

One or two clinicians from each clinical team were also interviewed about their experiences of using the app after each client’s discharge, resulting in a total of seven clinician interviews.

For both client and clinician interviews, we analysed transcripts using reflexive thematic analysis, following the guidelines by Terry et al. [Citation28], which is based on the approach of Braun and Clarke [Citation29]. Two team members (DB, JD) spent time becoming familiar with the interview transcripts and undertook initial data coding. Codes were examined, discussed and reviewed as patterns were discerned. Five potential themes were presented to and reviewed by the whole research team in a data analysis workshop attended by all authors, who had previously received all interview transcripts for review. On the basis of the workshop, developing themes were revised (DB and JD). These were once more reviewed by all authors, whose further feedback and clarifications were incorporated. This review process lead to the refinement of the core themes and subthemes presented below.

Results

Engagement data

Video update frequency

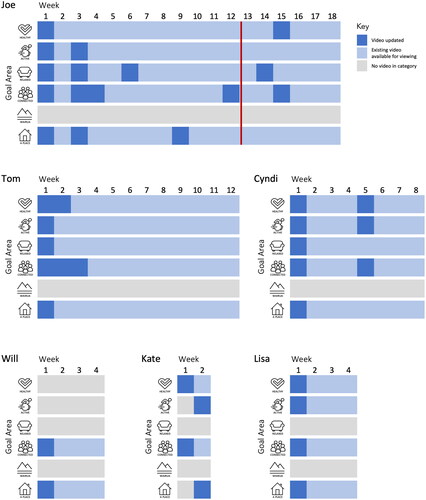

displays this timeline of video updates across each goal area, on a per-client basis.

Figure 2. Updates to Rehab Portal per client, by video category and weeks of stay. Individual timelines that show when videos were updated for six clients, for each of the goal areas ‘Healthy’, ‘Active’, ‘Relaxed’, ‘Connected’, ‘Wairua’, and ‘A Place’. Each client has videos added in the first week, in four of the cases to five goal areas. No client has videos for ‘Wairua’. After initial videos are added, updates were sporadic for the two of the longer-staying clients (stays of 18 weeks–Joe and 8 weeks–Cyndi), but were made only in the first three weeks for one other long-staying client (with a stay of 12 weeks–Tom), while no updates were made to the videos of the shorter staying clients (4 weeks–Will, 2 weeks–Kate, 4 weeks–Lisa) after they were initially loaded in the first two weeks.

For all clients, videos were recorded for two to five overarching goal areas. Although Wairua (spirituality) was a standard goal area to be considered for clients in the service, no goals were set in this area. Connected (relationships and being connected to other people) and A Place (a place to call home, having somewhere that you live and belong) were the two goal areas consistently used for all participants.

Contrary to our expectation, we saw only infrequent updates in goal videos across the course of the inpatient rehabilitation for the six clients with the exception of one client—Joe—who had multiple video updates. Notably, however, the majority of these updates occurred in the first 12 weeks of this client’s use of the portal—when videos were being recorded with the research team and then installed onto the device manually. This created a natural focal point for the clinical team to update their videos. From Week 13 videos were recorded by the clinical team directly into the Rehab Portal using the front-facing video camera, and this same procedure was used throughout the entirety of the stay of the other five clients. This feature was always part of the planned Rehab Portal design, and was expected to make it easier for clinicians to seamlessly record video updates during client sessions, rather than this being moderated by the research team. However, the data in suggests that once this feature was available video updates appeared to decrease in frequency. Indeed, for three of the six (Will, Kate, and Lisa), no updated videos were recorded in any goal area once a video had been initially recorded, and in one other case (Tom) updates to the videos occurred in only some goal areas, and in only the first 3 weeks of a 12 week stay.

Our interview findings, discussed below, provide insights into the ways that clinicians were approaching and using this platform.

Client use of Rehab Portal

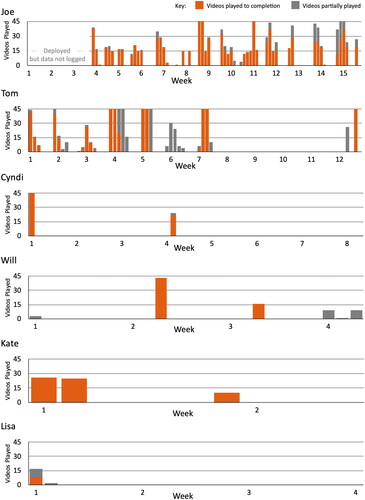

displays how often videos were played on the Rehab Portal by clients, and how many of those videos were played to completion.

Figure 3. Videos played per day from tablet deployment, by client. Daily data for each of six clients for how many times videos were played partially and to completion on each day of their stays, which ranged from 2 weeks to 18 weeks. Joe made heavy use of videos on many days throughtout their stay, frequently watching all 15 videos to completion, and with a maximum of 117 videos played and 102 videos completed on the most active day. Tom viewed videos on 3–5 days most weeks for his first seven weeks of his stay, often watching 15 to over 45 videos to completion a day. On his peak day he watched 238 videos, 174 of these to completion. However, he watched no videos from Week 8 to 11. He viewed videos again on two days in Week 12. Cyndi watched videos on only two days of her 8 week stay, playing videos 77 times times on her first day, 75 times to completion, and over 20 times one one day in Week 4. Will likewise had sporadic viewing, watching videos only six days across his four week stay, with a peak of nearly 45 views in Week 2, one day of just over 15 views in Week 3, and four other days of 1-10 views. Kate watched around 25 videos one Days 1 and 2, about 10 videos at the end of Week 1, and did not view vides again during her two week stay. Finally, Lisa viewed just over 15 videos on Day 1, half to completion, partially watched a couple of videos on Day 2, and did not watch videos again during her stay.

Clients had goals set in a maximum of five goal areas (fewer for some clients). In each case, there were three videos per goal (Why, What and How). Therefore, when a client viewed 15 videos in a day, this can be interpreted as having watched the videos across each of their goal areas once. As can be seen in , on days of high engagement, clients often watched all of the videos available to them, and on many engagement days they watched all of the videos multiple times, and many to completion. The figure displays up to the first 45 video plays in a day, so outlier days do not render other data hard to read. On high engagement days several clients exceeded this number and the full number of plays is recorded in the figure footnote.

Two clients, Joe and Tom, displayed consistently high levels of engagement with the Rehab Portal. Joe was engaged across all of his inpatient rehabilitation. Joe was the first client to use the Rehab Portal, and for the first three weeks we collected usage data via a third party analytics tool, which did not prove to be reliable. At the three week point, we replaced the tool with local storage on device of our own logging data, enabling a consistent record to be maintained. Data for the remainder of Joe’s extended inpatient stay show a high level of engagement with the Rehab Portal. This is particularly so when it is considered that Joe had regular two-day weekend leave periods at home during this period, which correspond with many of the periods of non-use in his profile.

Tom displayed significant engagement for the first eight weeks of his inpatient stay, frequently watching videos and often watching all available videos multiple times to completion on days he engaged with the portal. His clinical team reported that he was extremely confused about multiple aspects of his rehabilitation including the purpose of the portal. However, for a few days, Tom began recording a thought record prompted by seeing the ‘record’ button and encouraged by his speech language therapist. Videos were last updated for Tom during Week 3 of his stay. After Week 7, Tom ceased viewing any videos until the week of his discharge.

More limited levels of engagement were evident for the remaining four clients. Videos were watched on some occasions, but on most days there was no engagement with the Rehab Portal. In Cyndi’s case there was one update of videos at Week 6, but for the remaining three clients, videos were created by the clinical team at outset but were not updated during their stay. (Note that for Will and Lisa their total inpatient stays extended 18 weeks and 10 weeks after Rehab Portal deployment. Data is presented here for the first four weeks only, as that was the period of formal data collection. However, the Rehab Portal remained available to these clients and their teams after this period, and we understand engagement with the Rehab Portal remained extremely low for the remainder of their stays.)

Interview findings

Disrupting practice

Changing how things are done

The Rehab Portal required goal setting to be done in a Why-What-How format and encouraged regular video updates. Inherent in the approach was an expectation that rehabilitation goal setting be client-centred, participation- and role-focused, embedded in the process of rehabilitation, and that goals would be regularly reviewed.

“It made me more aware, kind of going through that process of the, what was it? The Why, What, How and yeah kind of breaking that down, making things really functional, and the whole interdisciplinary approach, so I definitely think it made me more aware of that…”

Anna (Clinician)

The approach was designed to match the service goal philosophy and as such, the Portal was originally conceptualised as a novel way of operationalising an existing goal planning process. However, in reality, fully integrating the Portal into therapy sessions required a change in practice which proved to be challenging for some clinicians:

“I think maybe some therapists aren’t as flexible in their thinking. So, it’s kind of hard for them to say well this is the goal I have in my mind, how can I put it into this format…”

Anna (Clinician)

Clinicians reported the approach prompted a shift in their thinking about goals, and changed how they framed goals for clients. Other changes included actively reformulating goals during therapy sessions with clients, who could direct the process. As such, it relied heavily on the ability of clinicians to think on their feet.

“I guess it’s a different sort of flow chart of considering the goals. I wouldn’t say I’m necessarily setting different goals, it was just the way that it’s kind of, the goals are framed, and potentially framing them with clients, I guess I was talking about the goals is different because of the structure. I guess it’s not how I would have normally necessarily have talked about them but because of the structure then I kind of did. … just yeah maybe a slightly different way of thinking about the goals.”

Angela (Clinician)

In reflecting on the use of the Portal, some clinicians conceded that while there was an intent to be client-centred in practice that this could fall to the wayside. On the contrary, the Portal provided a structural support to explicitly connect to meaning (the ‘Why’), to potentially increase the value of rehabilitation for clients.

“We try our best to make rehab client-centred but you know we often get bogged down in the process of things and previous experience and all those kinds of things and we try and you know incorporate it into activities they like but actually anchoring it to a meaning is probably the best way in order for them to feel motivated to do it and… how we can actually make our rehab more meaningful”

Lillian (Clinician)

Deviating from usual routines

Clinicians required ongoing implementation supports, including in-service training and coaching from on-site clinical leaders (MvS, JA) who held dual roles as core members of the research team.

“I think it’s just a matter of getting everybody on board… I think it needs to be very interdisciplinary for that to work. And I think after we had that kind of in-service by you guys, it was kind of, Oh OK, like I wish I kind of would have had that before participating in the project… it was just a bit of a challenge fitting in our goals in that way but I think we were coming from more of a MDT [multidisciplinary team] perspective as opposed to IDT [interdisciplinary team].”

Anna (Clinician)

Despite this, clinicians’ somewhat limited engagement with the tool appeared to be partly due to the simple reality that it can take a long time to develop experience and confidence in using a new tool in practice—and that until something becomes ‘business as usual’ it takes considerable and specific effort to use it well.

“This is something new that isn’t set into, you don’t do it when you’re doing your notes. You don’t have an automatic prompt for it so that’s probably why it went to the wayside with me.”

Kay (Clinician)

Adding burden

Some clinicians perceived the Portal to be extra to their existing practices, rather than an integrated part of existing therapy sessions. This created additional time pressures and may have contributed to those clinicians giving a low priority to engagement with the Rehab Portal.

“It took, I suppose, from time that you were spending with clients… because we’re setting our goals in the [Clinical Records System], it’s already set. It was just a duplication of that for me… I think the idea of making the goals more personal and obtainable for clients is really important… But there’s also the negatives of it does take away from therapists’ time”

Kay (Clinician)

This was not true of all clinicians, however. Some recognised that the Rehab Portal could be integrated fairly seamlessly within the existing therapeutic interactions.

“I think that the biggest thing is, don’t think of it as extra work… try your best to incorporate it into your sessions, because I think that probably is the biggest barrier… and like comments from other therapists, who have been a part of it, is basically around those things, is it’s like an extra… but I think that it probably shouldn’t be and I think that mentality was probably one of the limiting factors… do it as part of your sessions. It’s not high pressure or anything. It’s just trying to have a conversation with your clients like you would at the end of any session.”

Lillian (Clinician)

That said, the location where videos could be recorded was fixed because the tablets were installed on wall mounts in client bedrooms, and not every session was conducted in or near patient bedrooms.

“I guess the thing that I found most tricky was finding the time to do it, so my sessions with clients are sometimes in their rooms, but mostly not. So, it might be that I had taken a client out to do like a food shop, or out on a community trip or something like that, and I just, I wasn’t even going back to their bedroom with them, we’d used up the full amount of time”

Angela (Clinician)

We observed this was particularly a challenge for physiotherapists, who appeared to deliver the majority of their interventions in their multi-resource gym facilities, and in many cases appeared to never visit clients in their own rooms.

Threatening professional integrity

Engagement with the new practices in the Rehab Portal created a number of potential threats to clinician integrity. Using the Portal exposed clinician practice in a way that had not occurred before. Previous practice enabled clinicians to simply record a goal in the clinical record and then implement it. Discussing a client’s goals and recording videos crystallised clinician actions in a more visible way. This was accompanied by discomfort and awkwardness at appearing on video and a loss of control as the videos were able to be viewed by the client, family and other clinicians once recorded.

“I think if I got used to it… then I would get better at working out what to put on but from my perspective I was still at the stage where I needed to go away, write everything down almost like a script, come back and then read it… cos I’m not very good on camera, I get quite anxious. Over time, that would sort of go and then I’d sort of, it would flow, but I hadn’t got to that point where it had… I need to overcome my own being on camera, talking into the camera, just seeing my face makes me feel awkward. Like I said, at the moment I think I’m just, I was at the stage where I had to have my script written out cos otherwise I ramble. I think no client needs to listen to me rambling away.”

Angela (Clinician)

These videos captured clinician communication in a new persistent record. There was a sense of exposure as previously private or hidden work was on display.

“She talked us through… how it was best to actually give the goals, and like the wording around it and that it was more supposed to be a conversation, it was more supposed to be you know trying to relate to the client at their level and things like that… and I think that was really helpful, because I think prior to that, I maybe felt a little bit pressured and was like, oh my gosh what am I going to say…”

Lillian (Clinician)

It seemed at least some clinicians feared this highlighted limitations in their work that were not best practice. This was especially felt in areas where they felt less confident. In particular there was a recognition, or at least a perception by clinicians, that they were not doing well at recording goals in their usual practice.

“I’m useless at doing written goals and professional goals anyway at the best of times, so to have to do both at the same time is, yeah, run out of time, not enough time in the day.”

Leanne (Clinician)

Indeed, the development of the Rehab Portal itself was perceived by one clinician as evidence of these weaknesses, rather than as a tool to support the therapeutic effectiveness of a competent rehabilitation team.

“I guess this is the whole reason, well one of the reasons why the app’s been developed, that we’re not even very good here at keeping on top of our written goals, like not that we’re not keeping on top of them in real life, cos I feel that everything we’re doing is goals-related. It’s just that when we have to keep updating them on the computer system, we’re not necessarily keeping them up to date there”

Angela (Clinician)

Repositioning goal planning

In some cases, goal setting seemed to primarily function as a process of determining the goals a client held, rather than using the process itself as an ongoing therapeutic tool for engagement. In this sense, the Rehab Portal platform was used as a vehicle to present goals—rather than a communication platform that might support engagement in clients with consistent use over time.

“I think I only recorded on the app once I believe, and I think that was more, not because, well mostly because Lisa didn’t think she had any goals. She was a really tricky client because I guess from our perspective one of the main goals of using the [Rehab] Portal was to help increase her awareness of why we were doing what we were doing, but I don’t know if it was a useful vehicle for that. I don’t know if anything would be apart from just her learning… she didn’t really think she had any goals and so, the whole system for her was kind of maybe not something that she really resonated with”

Lillian (Clinician)

When it worked well, the Rehab Portal catalysed a repositioning of goal setting away from being clinician directed, towards an ongoing, dynamic collaboration between clinicians and clients and their family/whānau.

“I think it definitely helped him, yeah it was definitely key in helping him develop his own goals, because if we didn’t have this, this kind of goal setting activity prior to recording, I’m not sure if I would have pushed him to initiate his own goals which he has trouble doing… it kind of forced us as therapists to really ask – Joe, what do you want to do? … So maybe without this experience I might have said, OK well we’ll just do this and it’s functional… but this really forced him [the client] to generate what he wanted to work on”

Anna (Clinician)

Some clinicians were responsive to adapting to a client-centred process, and for them goal setting developed into a ‘point of discussion’ that transformed the recording of goals into an activity which became ‘like a therapy session’. This reframed the purpose of therapy sessions themselves, and was a shift in practice for the clinician.

“I do think that it makes, you’re doubly aware that it’s the client’s goals, it’s not yours… the benefit that I saw was the fact that Joe started taking ownership of it and that’s what I wanted to see. It became his Portal and his goals, and I think that’s probably what’s more different, is that he had more buy in because it was his face looking back at him, it was his voice, his goals and his words. So that was great.”

Stella (Clinician)

There was a positive impact and a sense of ownership when the client had opportunity to engage more fully with the app, facilitating new opportunities for greater discussion of goals and more effective communication. This was recognised by the client as well.

“OK, this is all about me, this is not about anyone else. This is about what I want to achieve not anyone else, which is quite good to have cos you’re like, ‘OK, this makes a lot more sense’ and you’re like, ‘Sweet, it’s what I want to achieve and how am I going to do it?’ It felt a little bit more personal because it was me up there, not someone else—which you’re like, OK, now I really have to do it.”

Joe (Client)

There was also the potential benefit of providing another pathway to communicate about the rehabilitation process with a client’s family as noted by one of the clinicians who observed this in action.

“The other thing I really liked about it is I think family actually understood what we were doing. If they weren’t here as often as they’d like to be or for whatever reason, they could actually flick through it and see the change and see what the client’s meant to be doing the next week too…It’s probably one of the biggest benefits to be honest, is that they still feel that they have engagement with the rehab programme”

Stella (Clinician)

Clinician motivation played a key role in use of the Rehab Portal. Some clinicians saw the potential therapeutic benefits, such as a role for the Portal in supporting engagement of clients who initially lacked awareness.

“With a lot of our clients they don’t have awareness, but I think for some people this tool actually could help that… I saw Kate when she was using it and for her, it was a tool for insight because she was talking in these videos and she had no idea. She couldn’t remember the fact that she was talking in the videos. So for her it was kind of like that realisation that, oh I actually do have problems.”

Lillian (Clinician)

Despite these positive experiences, not all clinicians interviewed felt engaged with the Rehab Portal during the app trial—it seemed reluctantly used over the period of the trial by a number of clinicians. This reluctance appeared to stem from the need to change existing practices.

“Goal setting’s really hard with clients with brain injury, it’s just a difficult thing, the general population. I think that [the Rehab Portal is] a good concept, but I don’t know that it’s changed how I’ve done goal setting.”

Carmen (Clinician)

Some clinicians displayed lower levels of engagement during the app trial and struggled to adjust to the new requirements. However, in hindsight some recognised the potential for the app to positively impact therapy outcomes. This clinician reflected on the amount of information she was initially giving the client compared to when the client himself was given the opportunity to engage with the Portal and simplified his goals.

“I think I probably would simplify stuff if I did it again. I think you know perhaps we had too much and Joe had very specific communication cognitive needs but really the simplifying it further was what worked for him. And, you know, that might be our learning too because we tried to incorporate a lot, but actually it was the simplified version that worked the best.”

Stella (Clinician)

Reverting to the status quo

The unexpected impact of client demotivation: “Nothing to work on”

When clients displayed what was perceived as low motivation to use the Rehab Portal app, clinicians appeared to accept the reluctance of those clients, rather than proactively encouraging its usage.

“I said to her, ‘Are you interested in, you know, if I manage to access onto it to and record some videos for you, would you be going onto it to look at the videos?’ And she basically said no, so she probably wasn’t…”

Angela (Clinician)

Later, the same clinician indicated that choosing not to use the Portal was in response to the client’s level of engagement:

“I would have prioritised it more if I thought it was something she was actually more engaged in.”

Angela (Clinician)

It was disappointing that the Portal was perceived by at least some clinicians, as only appropriate when clients displayed motivation to use it, rather than utilising it as a tool for creating and maintaining client engagement. Some realised the potential it had for encouraging motivation in clients in theory but in practice found it difficult to translate that to individual clients.

“just the clients that we’ve thought would be appropriate just haven’t interacted very well, and it’s unfortunate cos I think that it could be a motivating tool.”

Carmen (Clinician)

The process abandoned

Our observation was that the personality of both client and clinician appeared to play a role in these dynamics. When discussions about rehabilitation goals were leading to conflict with clients, clinicians would sometimes withdraw from the process, rather than risk a deterioration in their therapeutic relationship.

"Something that held me back was my client’s attitude towards it, so that made me nervous to go up to her room, to go record it, because of her attitude towards goal setting…”

Carmen (Clinician)

Returning to this topic later, the same clinician remarked:

“Cos you’d think that someone with really poor memory would be great for this but I guess the personality interacted with that. Someone with poor memory would be great but you’ve got to take into account their personality”

Carmen (Clinician)

Clinicians’ reticence to engage with the process appeared to be reflected in how they interacted with clients using the Portal, with some clients noticing their clinicians seemed to be lacking in encouragement or direction.

“I think what would have been really good with the app and it probably would have worked better for me, would be if I had some more continuity with the girls [therapists]. Instead, I felt left to my own devices and so I didn’t do anything for several weeks.”

Cyndi (Client)

“Cos, I haven’t really used it, so maybe being more connected to who I’m meant to be using it with”

Lisa (Client)

As discussed earlier, however, when clinicians recognised the Rehab Portal as a therapeutic tool they engaged more readily than those who saw it as just a tool for recording goals and nothing more.

“I think there’s lots of different things that clients can get out of it, so awareness is probably a really good one around why they’re working on what they’re working on because they have those really big goals but they don’t actually know how to get there… for people with memory problems it’s gonna be really useful as well reminding them why we’re doing what we’re doing and where they are … and I also think for some people as well it’s a really good tool for their own rehab in recognising what things they do want to work on cos goal setting is kind of hard.”

Lillian (Clinician)

Discussion

It appears that for many rehabilitation therapists, dynamic collaboration around goals during therapy sessions may require a new way of working with clients. For clinicians, active engagement with the Rehab Portal encouraged a critical reflection on goal setting practices, facilitating a move away from a multidisciplinary goal process to interdisciplinary, client-centred rehabilitation planning, with the benefit of making therapy more relevant for clients. At the same time, this challenge to move to a new mode of practice was not straightforward, and suggests that when faced with client apathy or resistance, clinicians may not persist with attempts to implement a practice pattern they are less familiar with.

While there is demonstrated value in rehabilitation in attending to the extent to which goals are feasible to achieve [Citation10], this does not mean goals setting should be driven by what is deemed by clinicians to be ‘appropriate’ for a particular client or those things that will achievable during the course of a rehabilitation stay—it is important that goals are also meaningful and important to clients [Citation5,Citation30] and that work is done to integrate life goals with more immediate rehabilitation goals [Citation31]. Part of this will lie in the initial process of selecting goals in the goal planning process. Another potential component of this for clients with cognitive impairment may be communication tools, such as using approaches like the video recordings examined in the current research.

While the use of video recordings or technology platforms is certainly not the only possible facilitator for such change, it has the potential to play a role in addressing a number of barriers. This includes through providing a novel pathway to address client knowledge gaps regarding their condition and the rehabilitation process, and addressing limitations in client access to time with clinicians, both of which have been identified as import barriers to effective goal setting processes [Citation32]. In a parallel to the way that video self-modeling can be useful to gain insight into communication patterns after brain injury [Citation33], it is possible that engaging with videos of themselves and those around them talking about their rehabilitation needs and goals may facilitate clients to grasp on to and understand the importance and meaningfulness of these observations. This may therefore assist in some cases in bridging the perspectives of clients and their families, support people and clinical support teams.

The findings of this trial have cast light on both potential benefits and difficulties in the implementation of this new (potentially) supportive technology. We cannot say with confidence what the effect would be if this technology was implemented into routine practice. Of particular interest would be to see the effect on both clinician practices and clients if videos were consistently updated in the Rehab Portal on a weekly basis, to increase the likelihood that the content would continue to be both engaging and current for clients. It is possible that future studies or clinical deployments would want to examine mechanisms to support, encourage or require video updates on a regular schedule, given we did not see these spontaneously occur in the course of this initial trial deployment.

Limitations of the current study

Clients for this sample were selected by the clinical service team members (MVS and JA) on the basis of perceived suitability for the intervention. These clients were not representative of the rehabilitation service they were drawn from (which in particular has an average length of stay of just 28 days on average) and thus they are not likely to be representative of all clients likely to pass through an inpatient brain injury rehabilitation centre. These clients were not, however, selected on the basis of being high functioning or having particular ability with information technology. We anticipate that any future version of the Rehab Portal app will be able to be used with clients who function at a range of levels of cognitive functioning.

We made many observations in working alongside the clinical teams, and collected a substantial depth of information through interviews. Other clinicians might however, have had other experiences. It would be interesting to collect a broader range of observations, comparisons and feedback of this or similar technologies being more widely incorporated into usual practice. This would likewise allow observations over a longer total period of time, with service-wide engagement that would allow for familiarisation for all therapists in a rehabilitation team. This may enable organic staff interactions to support moving such a system from a novel technology to being embedded into usual practice.

Conclusions

Good communication is fundamental to the delivery of clinical services. There is a limit on how much time clinicians can spend sitting down and talking to clients directly, no matter how client-centred a service is. Despite this, we have paid scant attention to using asynchronous modes of communication to support effective communication between clients and clinicians. In particular, while video is a widespread and growing media of mainstream communication, we are not aware of instances of routinely using it as a support for communication in brain injury rehabilitation clinical service delivery. There is the potential that such approaches may in the future facilitate improved communication, improved client and family understanding of clinical care, and thus improved outcomes for clients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Morris JH, Kayes N, McCormack B. Editorial: person-Centred rehabilitation – theory, practice, and research. Front Rehabil Sci. 2022;3:980314.

- Kang E, Kim MY, Lipsey KL, et al. Person-Centered goal setting: a systematic review of intervention components and level of active engagement in rehabilitation Goal-Setting interventions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(1):121–130.e3.

- Conrad N, Doering BK, Rief W, et al. Looking beyond the importance of life goals. The personal goal model of subjective well-being in neuropsychological rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(5):431–443.

- McPherson KM, Kayes NM, Kersten P. MEANING as a smarter approach to goals in rehabilitation. Rehabil Goal Setting Theory Pract Evid. 2014;105–119. ISBN: 9780429106828.

- Levack WMM, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. Purposes and mechanisms of goal planning in rehabilitation: the need for a critical distinction. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(12):741–749.

- Cameron LJ, Somerville LM, Naismith CE, et al. A qualitative investigation into the patient-centered goal-setting practices of allied health clinicians working in rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(6):827–840.

- Lloyd A, Bannigan K, Sugavanam T, et al. Experiences of stroke survivors, their families and unpaid carers in goal setting within stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16:1418–1453.

- Plant S, Tyson SF. A multicentre study of how goal-setting is practised during inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(2):263–272.

- Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):291–295.

- Van Bost G, Van Damme S, Crombez G. Goal reengagement is related to mental well-being, life satisfaction and acceptance in people with an acquired brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30(9):1814–1828.

- Knutti K, Björklund Carlstedt A, Clasen R, et al. Impacts of goal setting on engagement and rehabilitation outcomes following acquired brain injury: a systematic review of reviews. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;44(12):2581–2590.

- Levack WMM, Kayes NM, Fadyl JK. Experience of recovery and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(12):986–999.

- Doig E, Fleming J, Cornwell PL, et al. Qualitative exploration of a Client-Centered, Goal-Directed approach to Community-Based occupational therapy for adults with traumatic brain injury. Am J Occup Ther. 2009;63(5):559–568.

- Jamieson M, Cullen B, McGee-Lennon M, et al. Technological memory aid use by people with acquired brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;27(6):919–936.

- Jamieson M, Monastra M, Gillies G, et al. The use of a smartwatch as a prompting device for people with acquired brain injury: a single case experimental design study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;29(4):513–533.

- Brunner M, Hemsley B, Togher L, et al. Technology and its role in rehabilitation for people with cognitive-communication disability following a traumatic brain injury (TBI). Brain Inj. 2017;31(8):1028–1043.

- Sansonetti D, Nicks RJ, Unsworth C. Barriers and enablers to aligning rehabilitation goals to patient life roles following acquired brain injury. Aust Occup Ther J. 2018;65(6):512–522.

- Dikmen SS, Corrigan JD, Levin HS, et al. Cognitive outcome following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(6):430–438.

- Svoboda E, Richards B, Leach L, et al. PDA and smartphone use by individuals with moderate-to-severe memory impairment: application of a theory-driven training programme. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2012;22(3):408–427.

- Wong D, Sinclair K, Seabrook E, et al. Smartphones as assistive technology following traumatic brain injury: a preliminary study of what helps and what hinders. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(23):2387–2394.

- Evald L. Prospective memory rehabilitation using smartphones in patients with TBI: what do participants report? Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2015;25(2):283–297.

- Dalton C, Farrell R, De Souza A, et al. Patient inclusion in goal setting during early inpatient rehabilitation after acquired brain injury. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(2):165–173.

- Evans JJ. Goal setting during rehabilitation early and late after acquired brain injury. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25(6):651–655.

- Ylvisaker M, McPherson K, Kayes N, et al. Metaphoric identity mapping: facilitating goal setting and engagement in rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18(5-6):713–741.

- Dungey K, Douglas D, Pick V, et al. Role-based goal setting in catastrophically brain injured individuals: a new paradigm. JARNA off J Australas Rehabil Nurses Assoc. 2020;23:7–12.

- McGrath JC. Ethical practice in brain injury rehabilitation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- Zargaran E, Schuurman N, Nicol AJ, et al. The electronic trauma health record: design and usability of a novel tablet-based tool for trauma care and injury surveillance in low resource settings. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(1):41–50.

- Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, et al. Thematic analysis. In: Carla Willig, Wendy Stainton-Rogers, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. 2nd ed. SAGE; 2017. p. 17–37. ISBN: 978-1-4739-2521-2

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- Prescott S, Doig E, Fleming J, et al. Goal statements in brain injury rehabilitation: a cohort study of client-centredness and relationship with goal outcome. Brain Impair. 2019;20:226–239.

- Nielsen IH, Poulsen I, Larsen K, et al. Life goals as a driving force in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: a longitudinal dyadic perspective. Brain Inj. 2022;36(9):1158–1166.

- Crawford L, Maxwell J, Colquhoun H, et al. Facilitators and barriers to patient-centred goal-setting in rehabilitation: a scoping review. Clin Rehabil. 2022;36(12):1694–1704.

- Hoepner JK, Sievert A, Guenther K. Joint video self-modeling for persons with traumatic brain injury and their partners: a case series. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2021;30(2S):863–882.