?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose

This study explores the usability, usefulness and user experience of the Forward with Dementia website for people with dementia and family carers, and identifies strategies to improve web design for this population.

Methods

The website was iteratively user-tested by 12 participants (five people with dementia, seven carers) using the Zoom platform. Data collection involved observations, semi-structured interviews and questionnaires. Integrative mixed-method data analysis was used, informed by inductive thematic qualitative analysis.

Results

Users of Version 1 of the website experienced web functionality, navigation and legibility issues. Strategies for desirable web design were identified as simplifying functions, streamlining navigation and decluttering page layouts. Implementation of strategies produced improvements in usability, user experience and usefulness in Version 2, with mean System Usability Scale scores improving from 15 to 84, and mean task completion improving from 55% to 89%. The user journey for people with dementia and carers overlapped, but each group had their own unique needs in the context of web design.

Conclusions

The interplay between a website’s content, functionality, navigation and legibility can profoundly influence user perceptions of a website. Dementia-related websites play an important role in informing audiences of management strategies, service availability and planning for the progression of dementia. Findings of this study may assist in guiding future web development targeting this population.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

People with cognitive impairment can provide useful feedback on design and accessibility of websites, and their input should be obtained when developing digital applications for this group.

This paper provides practical suggestions for website design features to improve function, legibility and navigation of websites for older people and people living with dementia.

Introduction

Dementia affects 47 million people globally and encompasses a range of neurocognitive conditions characterized by progressive declines in cognitive, functional and physical capabilities [Citation1]. Global dementia prevalence is expected to rise to 75 million by 2030, costing an estimated US$2 trillion in direct medical and social costs, and opportunity costs associated with informal care [Citation2]. Since 1990, the number of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) attributed to dementia have increased at rates several times higher than any other disease group, drawing considerable resources from communities, health care systems and governments [Citation2].

Cognitive difficulties for people with dementia can manifest as a declined ability in frontal and executive functioning, hindering capacity for planning, abstract thinking, problem solving and judgement [Citation3]. Dementia may also lead to a progressive decline in learning, memory and language capabilities [Citation3]. Impaired motor planning and ability, and reduced physiological reserves can exacerbate the incidence of frailty, falls, malnutrition and other physical comorbidities [Citation4]. Furthermore, sensory challenges such as visual-perceptual impairments, and visual or auditory hallucinations can be experienced by people with dementia [Citation3]. Cognitive, motor and sensory challenges may compound each other, severely impacting daily functional activities.

Family carers of people with dementia also experience substantial physical, psychological and social impacts as they face increasingly challenging needs. Carers experience higher rates and severity of adverse mental health outcomes while also reporting poorer levels of physical health, sleep, exercise and social support [Citation5]. Caring for a person with dementia usually takes place over a long time span and requires significantly more hours per week than caring for individuals with other conditions, impacting carers’ social and financial livelihoods [Citation6].

Recently accelerated by COVID-19 social distancing requirements, health and social care providers are increasingly exploring opportunities to provide dementia information, education and intervention via digital applications [Citation7]. These include software ranging from websites to communication programs and utility software that are run on a computer, tablet or mobile interface. Declines in executive functioning, language, motor and visuo-perceptual capabilities experienced by people with dementia [Citation3,Citation4] can be a significant barrier to successful digital health application usage [Citation8,Citation9]. Nonetheless, substantial increases in internet uptake by older people and a greater focus on self-management for people living with chronic disease are expanding the potential for digital dementia applications [Citation10,Citation11]. Emerging digital applications have been used by people with dementia to assist with activities of daily living as well as to facilitate management, planning, communication, learning or other unmet needs [Citation12–14].

The knowledge base for the design of digital applications for people with dementia is emerging. Previously, this population has been largely excluded from research and design processes [Citation15,Citation16]. However, attempts at user-testing with this group showed that valuable data can be collected by using appropriate procedures, tools and conditions [Citation12,Citation16]. User-testing studies often utilize a mixture of participant observations, interviews and questionnaires to determine application effectiveness and provide recommendations on digital interface design [Citation16,Citation17]. Past user-testing studies have led to improved content and terminology [Citation18,Citation19], reduced navigational or functionality issues [Citation18–21], informed typography, layout and aesthetics [Citation22–24], as well as stimulated improvements in accessibility guidance such as the international Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) [Citation25] for digital applications.

However, the current evidence base informing digital application design for people with dementia remains small, and predominantly focuses on early stages of application development [Citation16,Citation17], or on the needs of people with dementia as defined by carers [Citation26].

Carers and people with dementia tend to be in older age groups and their familiarity with digital technologies is typically lower than that of younger cohorts [Citation27]. There is however a range of digital uptake and literacy within older people, with many demonstrating high levels of technological competence [Citation28]. Knowledge concerning the design of digital applications for older people, such as implementing large sans serif typeface, simplified scrolling and minimalist interfaces also applies to carers and people with dementia [Citation19].

Carers have been more involved in the development of dementia applications than people with dementia, with some researchers suggesting that the needs of people with dementia might be supplanted by the needs of carers [Citation29]. Carers report needs for knowledge, resources and decision support aids to prepare for the large range of care and decision making they take on as dementia progresses [Citation6]; these needs could be supported through digital applications. A systematic review of 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that internet-based supportive interventions improved mental health outcomes but required greater personalization to help carers develop coping competence, react to behavioural symptoms, and alleviate carer burden [Citation30].

To answer these and other identified dementia support needs, the Forward with Dementia website (www.forwardwithdementia.org) was developed to provide post-diagnosis information for people with dementia and carers by the international research collaboration COGNISANCE (Co-Designing Dementia Diagnosis And Post Diagnostic Care). The website provides a browsable collection of articles tailored to either people with dementia or carers. In Version 1 (V.1) of the website, an associated “toolkit” allowed users, through creation of a unique URL, to create their own library of articles, and develop a prioritized, online schedule of practical actions as suggested at the end of each article. Both the website and toolkit allow printing, downloading or emailing articles. The design, content and basic functions of the website were co-designed with people with dementia, carers and health and social care professionals [Citation31] and web developers utilized WCAG 2.0 (2018) as guiding principles. This study was conducted during the adaptation and evolution phase of web development, where key errors, omissions and shortcomings were identified and addressed [Citation32].

This study aimed to explore the usability, usefulness and user experience of the Forward with Dementia website for people with dementia and carers. Additionally, this study aimed to identify strategies for designing digital applications to be used by people with dementia and carers.

Materials and methods

Design

We conducted an observational cross-sectional study, employing qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate website usability, user experience and usefulness. Definitions and methods are provided in . The study was conducted over two phases. Version 1 of the Forward with Dementia website was tested in phase one. User feedback from V.1 informed major changes to the navigation, functionality, legibility and minor changes to the content to produce V.2, which was tested in phase two. Recruitment was pragmatic, conducted during COVID-19 lockdowns and within tight time frames required by the web developers. Participants were drawn from a population who volunteered to participate in further research through the COGNISANCE project [Citation31]. Attempts were made to sample from different levels of digital literacy, location, age and gender to create diversity within the group. Participants were not required to test both versions of the website. Four participants tested V.1, two of whom also tested V.2. Nine additional participants tested V.2.

Table 1. Ergonomics of human–system interaction.

Ethical approval for this study was given by the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC no. 2021/329).

Participants

Five people with early-stage dementia and seven family carers participated in user testing (). Formal assessment of stage of dementia was not conducted. However, all participants retained the ability to provide informed consent and were competent in the use of all basic computer functions. Additional inclusion criteria for all participants were access to a personal internet connected device, use of the internet more than once a week, not having a visual or physical impairment that prevented the use of internet device, over 18 years old, and able to read English at a sufficient level to navigate an English language website.

Table 2. Participant demographics.

Procedure

The website was tested by participants using their own internet browsing device. Participants shared their screen and interacted with researchers via Zoom videoconference in a physical setting of their choice. Sessions were recorded via Zoom and recordings stored in secure password-protected servers. Recordings were transcribed using Otter AI software [Citation36]. NVivo [Citation37] was utilized to assist with the coding and analysis of qualitative data.

Participants were asked to browse the Australian Forward with Dementia website for 60–75 min while sharing their screen via Zoom. Participants were instructed to explore the website at their own pace while researchers observed their interaction with the website and asked questions based on the semi-structured interview guide.

Carers were encouraged to express their moment-by-moment thoughts, intentions, beliefs and expectations as part of the think-aloud protocol (TAP) [Citation38]. For people with dementia, the TAP was not strictly promoted as previous user-testing studies with people with dementia found that TAP hindered participants’ ability to concentrate on the application and did not yield insightful information [Citation12,Citation20]. People with dementia were encouraged to express their thoughts as they browsed the site, but with less regular prompting from researchers.

A list of six common tasks relating to navigation and functions of the website (e.g., scrolling, printing and navigating to and from an external link) that would demonstrate mastery was created (). Researchers observed whether tasks were independently attempted. If no attempt was made, participants received gradually increasing levels of assistance from researchers, from non-directive prompts, e.g., “Would you find this useful to have a printed copy of this article?” to direct requests, e.g., “Can you scroll to the print button and try printing an article?” until the task was able to be completed [Citation19]. Tasks differed slightly depending on the difference between V.1 and V.2 functionality at the time of user-testing.

Table 3. Tasks tested during user testing.

Data collected

Participant interviews, questionnaires and observation enabled data triangulation to enhance credibility and address weaknesses of each individual data collection method.

A semi-structured interview guide was used to collect qualitative data during and after user-testing. Examples of questions asked include “What aspects of the website were most helpful/unhelpful to you?” or “How useful was function X in helping you reach your goals”? This facilitated open-ended discussion around the usability, usefulness and user experience of the website.

The System Usability Scale (SUS) [Citation34] consists of 10 short statements about usability of digital interfaces. Following review by JZ and LFL, the SUS was simplified by changing words, terms and question order to be more relevant to participants of the current study. For example, the original statement “I think that I would use this system frequently” was simplified to “I think that I would use this website frequently”. The SUS captures quantitative data on a five-point Likert scale regarding participant perceptions of the usability, user experience and usefulness of the site. The first five questions concern agreement with positive aspects and the remaining five questions concern negative aspects of the participants’ interaction with the website. The SUS was administered at the end of the session. The original and simplified version is available in Appendix 1.

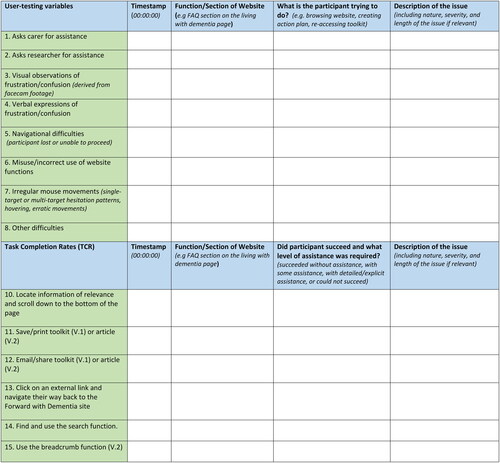

A User-Testing Behaviour Observation Grid () was developed by JZ and LFL based on key variables measured in similar studies [Citation19,Citation21,Citation22]. This grid facilitated collection of both quantitative and qualitative data, and recorded Task Completion Rates (TCRs), observations of user/navigational error, verbal and visual indications of difficulties, and irregular mouse movements [Citation19,Citation21,Citation22]. Observations were recorded during user-testing sessions by using this grid, with observations reviewed by analysing video recordings.

Figure 1. Participant behaviour observation grid and task completion activities.

Data analysis

Audio recordings of semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim and content analysis [Citation39] undertaken to identify common topics, ideas or patterns relating to the constructs of usability, usefulness and user experience. Integrative mixed-method interpretation [Citation40,Citation41] was undertaken by JZ, in collaboration with MG and LFL.

Notes taken using the observation grid and participant transcripts were analysed using line-by-line coding. Notes related to usability, user experience or usefulness were assigned a code (e.g., page length, scrolling and labels) and entered into NVivo analysis software. Codes with similar characteristics were compiled into categories (e.g., barriers to information pathways) which ultimately informed themes (e.g., navigational usability), and were then mapped to the three main constructs of usability, user experience, and usefulness. Quotes were those most representative of the entire sample’s experiences within each category/theme. Quotes that highlighted issues experienced by a subsection of participants were also used. Qualitative data captured through participant observation (visual observations of frustration, navigational difficulties, unvocalized issues) have also been recorded within the participant behaviour grids and captured in NVivo to assist with analysis.

Integration through narrative with a weaving approach [Citation42] was used to merge quantitative data with qualitative findings from interviews and participant observation. This entailed the concurrent but independent analysis of our quantitative and qualitative data. An integrated analysis of all data on a theme-by-theme or concept-by-concept basis was used to understand participant experiences of the website.

Results

Interview and participant observation data

From interviews, observation data and the TAP protocol, people with dementia and carers described characteristics they considered important for a usable, user friendly and useful website. Results are presented in (website content including information, images, language and terminology), (website functionality including search, scroll up/down arrow, breadcrumb, print, email and toolkit functions), (website navigation involving movement between and within pages of the website) and (website legibility such as visual design and typography). These characteristics emphasized simplification, reduction of number of steps for any action, streamlining of navigation, clarity of presentation and respectful language to support usability.

Table 4. Characteristics relating to user experience and usefulness of website content including information, images, language and terminology (participant interview responses are quoted and italicized).

Table 5. Characteristics of website functionality including search, scroll up/down arrow, breadcrumbs, print, email and toolkit functions (participant interview responses are quoted and italicized).

Table 6. Characteristics of website navigation between and within pages of the website (participant interview responses are quoted and italicized).

Table 7. Characteristics around website legibility such as visual design and typography (participant interview responses are quoted and italicized).

In V.1 of the website, content was regarded as useful due to its comprehensiveness of content, practicality and reassuring tone, but it did not meet other desired website characteristics. Participants found navigation was unclear and unintuitive, functionalities too complex, and visual design cluttered.

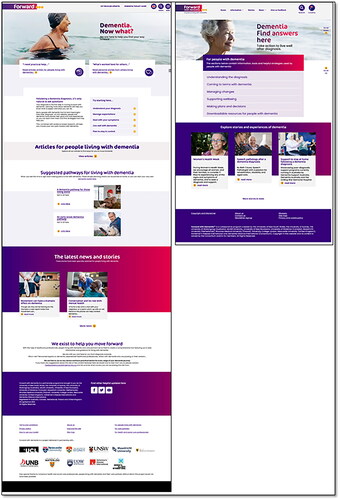

Website V.2 simplified functionalities. The toolkit was removed due to its overly complex and unintuitive nature, and poor integration into the main website, and replaced with a print and email function in the main website. V.2 navigation was streamlined, with more direct user pathways by shortening pages to reduce the need for scrolling and implementing alternative ways to navigate such as the breadcrumb function. Decluttering of the website by simplifying layout, reducing the number of clickable options, and incorporating adequate white space helped enhance legibility. While improvements across the website were not entirely uniform, the strategies identified for creating a usable, user friendly and useful digital application were more often achieved in V.2. A side-by-side screenshot of V.1 and V.2 of the landing page is shown in . This side-by-side comparison illustrates that web design may appear aesthetically pleasing but perform poorly for users without detailed consideration of the needs of people with specific cognitive, motor and sensory issues.

Figure 2. Side-by-side comparison of V.1 (left) and V.2 (right).

Task Completion Rates and System Usability Scale

shows TCRs. TCRs recorded in V.1 indicated that participants experienced difficulties saving, printing and emailing content. Completion rates of these tasks improved for V.2. For example, there was an improvement of 88.8% in TCR percentage for item-2 relevant to saving/printing, and a smaller improvement of 30.5% and 38.8% in TCR percentage for item-3 relevant to emailing/sharing and item-4 relevant to navigating, respectively. However, people with dementia continued to have difficulties with the email function.

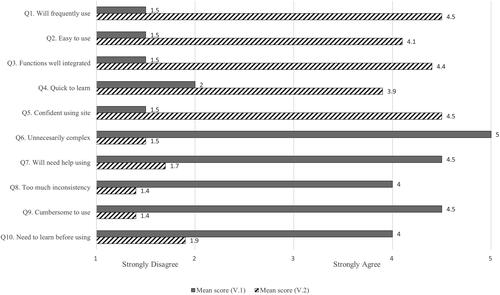

Comparison of mean SUS [Citation43] scores showed improvement on all 10 domains (). For the first five questions concerning positive interactions with the website, mean scores changed from = 1.60 to

= 4.28, where a higher score indicates higher usability. For the last five questions concerning negative interactions with the website, mean scores changed from

= 4.40 to

= 1.58, with a lower score indicating fewer usability barriers. Mean SUS scores were calculated from the 10 questions using standard SUS scoring processes [Citation43] and improved from

= 15.0 in V.1 to

= 83.75 in Version 2, with a score of >68 indicating better than average usability [Citation43].

Figure 3. Simplified System Usability Scale scores.

Table 8. Task Completion Rates.

Discussion

The purpose of this user testing study was to explore the usability, usefulness and user experience of the Forward with Dementia website for people recently diagnosed with dementia and carers, as well as identify strategies to improve both Forward with Dementia during website development website for these users and develop recommendations for improvement of digital interfaces for this population in Australia.

Usability and user experience of V.1 and V.2 of the Forward with Dementia website

Data from participant observation, interviews and the SUS indicate that the overall usability and user experience of V.1 were subpar. Long user pathways, overly complicated functionalities, and cluttered layouts contributed to negative participant feedback, low SUS scores and low TCRs. Improvements in these areas meant that V.2 was more usable as reflected in improved SUS scores, TCRs and interview feedback. Content usefulness was high for both versions. While only one carer (carer 7) and one person with dementia (participant 3) tested both V.1 and V.2, their feedback emphasized streamlined navigation, simplified functionalities and enhanced legibility.

Experiences of carers compared with people with dementia

Carers and people with dementia had overlapping perceptions of usability, user experience and usefulness, with key exceptions in several areas. Some participants from both groups did not realize there was content below the initial screen or found scrolling difficult. People with dementia experienced and verbalized these difficulties frequently, consistent with previous research [Citation16]. Difficulties with functions that required or assumed additional set up, such as email, were more prominent in people with dementia. They also experienced more direct and intense responses to colour, images and language. For example, people with dementia were more likely to complain about text and background colour contrasts, likely due to oculo-visual changes associated with dementia [Citation44]. People with dementia were also more sensitive to images portraying people with dementia, requesting depiction of wider range of age groups. While the language used was generally perceived to be appropriate by all participants, people with dementia were more ready to suggest friendlier or more understandable phrases. This may reflect different sensitivities to language between people with dementia and the general public [Citation24].

Perceptions of function usefulness slightly differed between groups. The print and email functions were appreciated by most participants. Carers were generally more enthusiastic about the email function compared to people with dementia, who conversely prioritized the ability to print. This may be because carers are more likely to be advocates and share information [Citation45].

Furthermore, people with dementia and carers looked for slightly different content, not just in terms of information, but also in subtextual needs. The Forward with Dementia site was valued by offering content tailored to specific informational and resource needs of each group, such as information and strategies to prevent or manage family carer burnout for carers, or information and resources on how to share the diagnosis for people with dementia.

Desired characteristics of digital applications for people with dementia and carers

This study found that minimalist design that reduced cognitive load better met the needs of people with dementia and carers. This may be achieved through decluttering interfaces, shortening user pathways and simplifying functions. People with dementia and carers wanted websites where it was easy find, save and share information, and that information should be comprehensive, practical and reassuring.

The desired characteristics identified in this study are consistent with the literature. The use of simple, clear and direct language to minimize misinterpretations of content and web elements has been frequently promoted [Citation18,Citation19]. The need to minimize scrolling and reduce pathways to information is well documented for people with dementia and older populations [Citation16,Citation46]. Intuitive but minimalist layouts with shortened page lengths reduces content density [Citation18,Citation21] and decreasing clickable options reduces cognitive load [Citation15,Citation47]. This study identified the importance of colour, colour contrast and typographic elements to enhance legibility, as documented by previous user-testing studies [Citation22,Citation23]. These findings also generally mirror recommendations/guidelines for designing websites for older people and people with other cognitive conditions [Citation19,Citation23,Citation27]. Previous studies have indicated uncertainties about the impact of labels and visual aids in assisting navigation within this population [Citation24,Citation48]. This study found that labels and icons are desirable for assisting navigation when prioritized for salient user pathways and implemented alongside a minimalist layout. The literature is mixed on the use of bullet points for people with dementia [Citation18,Citation21], but bullet points are recommended based on the findings of this study.

This study was consistent with previous research where carers emphasized the need for comprehensive, practical and reassuring content [Citation14]. In addition, we found tailoring content into separate sections for people with dementia and carers was highly useful compared to producing combined content for both groups.

This study illustrates that website components (content, functionality, legibility and navigation) are deeply interconnected from a user perspective. For example, being able to notice and use website functions such as the search bar is influenced by the overall legibility of the web page. The effectiveness of the search function shapes user navigation towards relevant content. As such, individual website components need to be designed in a manner that considers the whole user journey. For people with dementia one navigational barrier might mean they could not access large sections of content. Website components need to be designed in an integrated manner that considers a user’s potential motor, sensory or cognitive limitations. A holistic, user-centred design process will continue to be central in developing successful digital applications for people with dementia and carers. Considerations for website design with this population is summarized in .

Table 9. Key considerations for designing digital applications for people with dementia and family carers.

Further research is required to confirm findings, explore other design intricacies, and enhance knowledge in this area. Areas of particular interest may include the development of websites that negate the need to scroll, given the ubiquity of scrolling issues across the literature, and found in this study. Digital applications that simplify the process of acquiring, saving and sharing potentially large amounts of information should also be further researched.

Limitations

This study has limitations that may influence the generalizability of findings. Despite accounting for only 6–8% of dementia diagnoses [Citation49], three out of five participants with dementia in this study were diagnosed with younger onset dementia. Participants were recruited from the COGNISANCE database and investigator networks, had previously been involved in dementia research or advocacy, and are not necessarily a “typical” person with dementia or carer.

Prior interactions with researchers and the COGNISANCE project by participants and the videoconference nature of data collection may have increased the risk of social desirability bias [Citation50]. Researchers attempted to negate this by repeatedly encouraging participants to give honest feedback and checking findings against recorded participant observations. The retest effect may have also altered user behaviour for the two participants who tested both V.1 and V.2, potentially inflating perceptions of usability, user experience and usefulness [Citation51]. TCRs were introduced as an objective measure to mitigate these limitations.

The study design was affected by difficulties with recruitment during COVID-19 lockdowns and inflexible timelines for website development, resulting in uneven sample size for testing V.1 and V.2. Additionally, not all functionalities were tested in V.2, leading to missing TCR data. SUS data for carers 1 and 2 in V.1 were not collected. However, data collected from participant observation, interviews and TCRs for carers 1 and 2 were consistent with others from the same phase of the study.

This study did not explore other modalities of website usage such as information delivery via video or audio as an alternative to reading. Future research could consider contrasting user experience of different modalities.

Conclusions

Participant observations, interviews and questionnaire data demonstrated that the content in V.1 of the Forward with Dementia website was useful, but with poor usability and user experience in website functionality, navigation and legibility. Strategies to address these issues were successfully implemented to improve usability in V.2. However, some participants still struggled with certain aspects. Some people with dementia continued to find scrolling difficult, found the colour contrast in certain sections of the website hard to see, and could not use the email and print functions. This study illustrates the interplay between a website’s content, functionality, navigation and legibility can profoundly influence user perceptions of a website and they need to be co-designed in an integrated and user-centred manner.

Health and wellbeing information is increasingly available online. To ensure its accessibility by older people, and people with dementia, it is essential to increase understanding of how they interact with, and derive the most benefit from, using digital interfaces. This study provides key considerations for digital interface design for people with dementia and family carers and may guide future web development targeting this population.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the contribution of participants to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are not available due to ethical reasons.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025; Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Prince MJ, Wimo A, Guerchet MM, et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015 – the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015.

- Husain M, Schott JM. Oxford textbook of cognitive neurology and dementia. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Kurrle S. Physical comorbidities of dementia: recognition and rehabilitation. In Low L-F and Laver K (Eds.), Dementia Rehabilitation. London: Elsevier Inc.; 2021. p. 213–225.

- Connell CM, Janevic MR, Gallant MP. The costs of caring: impact of dementia on family caregivers. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2001;14(4):179–187.

- Thompson GN, Roger K. Understanding the needs of family caregivers of older adults dying with dementia. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(3):223–231.

- World Health Organization. Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2021.

- Yi JS, Pittman CA, Price CL, et al. Telemedicine and dementia care: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(7):1396–1402.e18.

- Savitch N, Zaphiris P, editors. Accessible websites for people with dementia: a preliminary investigation into information architecture. International Conference on Computers for Handicapped Persons. Springer; 2006.

- Ienca M, Fabrice J, Elger B, et al. Intelligent assistive technology for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56(4):1301–1340.

- Brown A, O'Connor S. Mobile health applications for people with dementia: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Inform Health Soc Care. 2020;45(4):343–359.

- Gibson G, Newton L, Pritchard G, et al. The provision of assistive technology products and services for people with dementia in the United Kingdom. Dementia. 2016;15(4):681–701.

- Mulvenna MD, Nugent CD, Moelaert F, et al. Supporting people with dementia using pervasive healthcare technologies. In: Mulvenna MD, Nugent CD, editors. Supporting people with dementia using pervasive health technologies. London: Springer London; 2010. p. 3–14.

- Lauriks S, Reinersmann A, Van der Roest HG, et al. Review of ICT-based services for identified unmet needs in people with dementia. Ageing Res Rev. 2007;6(3):223–246.

- Boman I-L, Nygård L, Rosenberg L. Users’ and professionals’ contributions in the process of designing an easy-to-use videophone for people with dementia. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014;9(2):164–172.

- Rai HK, Barroso AC, Yates L, et al. Involvement of people with dementia in the development of technology-based interventions: narrative synthesis review and best practice guidelines. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e17531.

- Span M, Hettinga M, Vernooij-Dassen M, et al. Involving people with dementia in the development of supportive IT applications: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):535–551.

- Bogza L-M, Patry-Lebeau C, Farmanova E, et al. User-centered design and evaluation of a web-based decision aid for older adults living with mild cognitive impairment and their health care providers: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e17406.

- Hattink B, Droes R-M, Sikkes S, et al. Evaluation of the Digital Alzheimer Center: testing usability and usefulness of an online portal for patients with dementia and their carers. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(3):e5040.

- Span M, Hettinga M, Groen-van de Ven L, et al. Involving people with dementia in developing an interactive web tool for shared decision-making: experiences with a participatory design approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(12):1410–1420.

- Freeman E, Clare L, Savitch N, et al. Improving website accessibility for people with early-stage dementia: a preliminary investigation. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(5):442–448.

- Quintana M, Anderberg P, Sanmartin Berglund J, et al. Feasibility-usability study of a tablet app adapted specifically for persons with cognitive impairment—SMART4MD (support monitoring and reminder technology for mild dementia). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6816.

- Borg J, Lantz A, Gulliksen J. Accessibility to electronic communication for people with cognitive disabilities: a systematic search and review of empirical evidence. Univ Access Inf Soc. 2015;14(4):547–562.

- Sarne-Fleischmann V, Tractinsky N, Dwolatzky T, et al., editors. Personalized reminiscence therapy for patients with Alzheimer’s disease using a computerized system. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments; 2011.

- Accessibility Guidelines Working Group. Making content usable for people with cognitive and learning disabilities: W3C Working Group Note; [cited 2021 Apr 29]; 2021. https://www.w3.org/TR/coga-usable/

- Kerkhof YJF, Rabiee F, Willems CG. Experiences of using a memory aid to structure and support daily activities in a small-scale group accommodation for people with dementia. Dementia. 2015;14(5):633–649.

- Czaja SJ, Sharit J, Lee CC, et al. Factors influencing use of an e-health website in a community sample of older adults. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(2):277–284.

- Wolverson E, White C, Dunn R, et al. The use of a bespoke website developed for people with dementia and carers: users’ experiences, perceptions and support needs. Dementia. 2022;21(1):94–113.

- Orpwood R, Sixsmith A, Torrington J, et al. Designing technology to support quality of life of people with dementia. Technol Disabil. 2007;19(2–3):103–112.

- Leng M, Zhao Y, Xiao H, et al. Internet-Based supportive interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e19468.

- Brodaty H, Low L-F, Vedel I, et al. Annual scientific report: co-designing dementia diagnosis and post-diagnostic care. COGNISANCE; 2020.

- Brender McNair J, Brender J. Handbook of evaluation methods for health informatics. Burlington: Elsevier Science & Technology; 2006.

- International Organisation for Standardisation. Ergonomics of human–system interaction – part 210: human-centred design for interactive systems. 2019. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-210:ed-2:v1:en

- Brooke J. SUS: a quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval Ind. 1995;11(30):189.

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quart. 1989;13(3):319–340.

- Liang S, Fu YO; 2021. https://otter.ai/

- QSR International. Nvivo; 2021. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Fonteyn ME, Kuipers B, Grobe SJ. A description of think aloud method and protocol analysis. Qual Health Res. 1993;3(4):430–441.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):846–854.

- Bazeley P. Planning for analysis. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2018. p. 21.

- Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156.

- Sauro J, Lewis JR. Chapter 2 – quantifying user research. In: Sauro J, Lewis JR, editors. Quantifying the user experience. 2nd ed. Boston: Morgan Kaufmann; 2016. p. 9–18.

- Armstrong R, Kergoat H. Oculo‐visual changes and clinical considerations affecting older patients with dementia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2015;35(4):352–376.

- Fetherstonhaugh D, Rayner J-A, Solly K, et al. ‘You become their advocate’: the experiences of family carers as advocates for older people with dementia living in residential aged care. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(5–6):676–686.

- Small J, Schallau P, Brown K, et al., editors. Web accessibility for people with cognitive disabilities. CHI'05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2005.

- Astell AJ, Joddrell P, Groenewoud H, et al. Does familiarity affect the enjoyment of touchscreen games for people with dementia? Int J Med Inform. 2016;91:e1–e8.

- Boyd H, Jones S, Harris N, et al., editors. Development and testing of the inTouch video link for people with dementia: design approach and practical challenges. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); 2014. IEEE.

- Sansoni J, Duncan C, Grootemaat P, et al. Younger onset dementia: a review of the literature to inform service development. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31(8):693–705.

- Larson RB. Controlling social desirability bias. Int J Market Res. 2019;61(5):534–547.

- Scharfen J, Jansen K, Holling H. Retest effects in working memory capacity tests: a meta-analysis. Psychon Bull Rev. 2018;25(6):2175–2199.