Abstract

Purpose

Globally, one in three individuals needs at least one assistive product. The primary objective of this study was to conduct a survey of Pakistani rehabilitation service providers to determine what proportion provide assistive technology and if their characteristics (including geographical region, education, and experience) are associated with adherence to the service delivery process. The secondary objective was to determine if individuals that provide assistive technology adhere to a standard assistive technology service delivery process. The tertiary objective was to determine if the providers that adhered to a standard delivery process had characteristics that differed from the rest of the service providers.

Materials and Methods

An online survey composed of multiple-choice questions was distributed to physiotherapists, community-based healthcare workers, and related rehabilitation professions through a convenience sampling method. SPSS Statistics was used to develop correlation matrices to determine Pearson’s coefficient of number of steps, education level, experience level and continuing education received.

Results

There were 71 respondents from 4 Pakistani provinces. 53.5% of respondents stated they provide assistive technology. There was participation in most steps of the service delivery process. There is weak correlation between number of steps and education level, number of steps and experience level, and number of steps and continuing education received.

Conclusions

While the majority of respondents provide assistive technology, a significant proportion (46.5%) don’t. This may suggest there is a need for additional advocacy and awareness raising of the benefits of and how to access assistive technology in Pakistan.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Pakistan implemented a Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment and determined that only 22% of the population that needs an assistive device has had their needs met.

From a relatively small sample, this study investigated if there is a presence of assistive technology service delivery in Pakistan and whether traditional education, experience, or continuing education promotes participation in the assistive technology service delivery process.

This study found a presence of assistive technology service delivery in Pakistan, but found weak correlations between participation in the service delivery process with traditional education, experience, and continuing education.

These findings suggest that there is room for additional advocacy and awareness training on assistive technology in Pakistan.

Introduction/background

According to the World Health Organization, “assistive technology is an umbrella term covering the systems and services related to the delivery of assistive products and services” [Citation1–3]. Assistive technology may mitigate challenges related to health and function, community participation, and independence for individuals with disabilities. Considering approximately 15% of the global population has a disability, assistive technology can significantly improve lives. Based on the Global Report on Assistive Technology, one in three people globally need at least one assistive product, yet, nearly one billion are denied access [Citation4]. This umbrella concept of assistive technology is characterized by the WHO Global Consortium on Assistive Technology (GATE) “5-Ps” which suggests that in order to have an effective assistive technology ecosystem, there need to be policies that help to ensure that personnel are trained and people receive the products and provision services they require [Citation4].

The evidence-based assistive technology service provision process typically consists of seven parts: (1) the evaluation of the client, (2) the prescription of the appropriate technology, (3) funding and ordering the product, (4) product preparation/assembly, (5) fitting the product to the client, (6) training the user and their family/caregiver on how to use the technology, and (7) a follow-up visit to ensure the product is meeting the client’s needs which may include maintenance or repair of the device [Citation5,Citation6].

The first step to implementing assistive technology is to assess the need. The World Health Organization developed a population-based Rapid Assistive Technology Tool for “rapid mapping of need, demand, supply, and user satisfaction of Assistive Technology” [Citation7]. The first country to implement the WHO rapid assessment was Pakistan after participating in Rehabilitation 2030: A Call to Action, a meeting to accelerate the implementation of rehabilitation services. Previous attempts to improve disability services in Pakistan had been slowed due to lack of reliable data and an inappropriate needs assessment [Citation8]. The rapid assessment was conducted at a national level with 9000 households and 63,000 individuals. It identified that 23.5% of the population had at least some difficulty with one functional domain, 16.8% of the population required an assistive device, and only 22.3% of these individuals had their needs met [Citation9].

In response to this, in collaboration with WHO, Pakistan has implemented a multidisciplinary rehabilitation workforce, financial policies for assistive technology access, and training for assistive technology users [Citation7,Citation10]. Stakeholders from Pakistan and WHO identified barriers to assistive technology provision including “lack of awareness at different levels (users, general public, health care providers, government), the role of gender, and placement of assistive technology within universal health coverage” [Citation10]. Gender inequality can affect access to assistive technology through limitations on funding and transportation. If assistive technology is not funded through universal health coverage, individuals may have limited available finances to purchase assistive technology on their own. Aside from Pakistan’s attempts to improve access to assistive technology, other studies explored the advancement of disability inclusion in Pakistan from a cultural viewpoint [Citation11,Citation12] and determined that the collective understanding of disability in Pakistan is positive in comparison to the UK, which may serve as a key facilitator to implementation and availability of services. This is because the UK group’s responses were skewed towards a negative view of disability in comparison to the Pakistan group, which implies that there is a greater social stigma associated with wheelchairs in the UK [Citation11]. To date, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, the literature has focused on the perspective of people with disabilities themselves rather than the providers.

Despite initial implementation progress and awareness of barriers in Pakistan, gaps remain in understanding the prevalence and description of who provides assistive technology services. To this end, the objectives of this study were to (1) determine who provides assistive technology in Pakistan and describe their characteristics, such as education, geographical region, occupation, and experience; (2) determine if the individuals that provide assistive technology adhere to the assistive technology service delivery process [Citation13]; and (3) determine if the providers that adhered to a standard delivery process had characteristics that differed from the rest of the service providers.

Methods

Survey development

An online survey implemented in Qualtrics was developed that included 12 multiple choice questions across 4 sections: Introduction and demographics, AT Education, Prescribing AT, and Follow-up. This study is covered under the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board protocol STUDY19100169. The survey was administered online and distributed through email, Facebook, and Messenger.

The primary objective was addressed by including two sections that applied to all respondents: “Prescribing AT” and “Introduction and Demographics.” Skip logic was employed to ensure relevance for both those who provide and do not provide assistive technology. Demographic queries included age, location, occupation, years of experience, highest level of education, and whether a respondent has a disability or uses an assistive product. Five questions were inspired by the World Health Organization Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment, including basic demographics of the respondents, what functionality providers addressed, and barriers to access.

The secondary survey objective was addressed by adding the section “Prescribing AT.” This section was content validated based on evidence-based service delivery processes in the literature [Citation5,Citation6]. Common process elements include assessment, prescription, funding and ordering, product preparation/assembly, fitting, training of users/families and caregivers, and follow up/maintenance/repair [Citation5,Citation6]. The tertiary objective was addressed by adding the section “AT Education.” This section was selected as a key provider characteristic to explore, including training received, the format of education that was received, and the location of training received.

Once the survey was finalized, it was reviewed for face validity by two subject matter experts who are assistive technology educators and researchers, have a combined 35 years of assistive technology experience, and are engaged in multiple global professional societies related to assistive technology.

Recruitment

There were four inclusion criteria: (1) Serve in a client-facing rehabilitation role in Pakistan; (2) 18 years of age or older; (3) Completed secondary education (grades 11 and 12) in Pakistan; (4) Able to read, write, and understand English. Prior to starting the survey, each respondent was presented with a paragraph summarizing how their information would be used and established informed consent through the respondent’s continuation of the survey. Through a convenience sampling method, the survey was distributed to 13 disability service organizations in Pakistan: Pakistan Disabled Foundation, Pakistan Society for the Rehabilitation for the Disabled, Comfort Zone, LC Disability and Development Program, NOWPDP, Peshawar Paraplegic Center, Dar ul Sukun, Special Talent Exchange Program, Society for Special Persons, Association for Rehabilitation for the Physically Disabled, Al-Noor Special Children School, VCare Welfare Trust, and Helping Hand Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences. Each of these organizations were contacted via email and through Facebook Messenger, if applicable [Citation14]. The survey was launched on 18 May 2022, and concluded on 10 June 2022.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographics and adherence to steps. Three demographic variables were selected for further analysis to determine whether there was a correlation between number of steps and education level, number of steps and experience level, and number of steps and continuing education received. The SPSS Statistics application for Mac OS X was used to develop correlation matrices and calculate the Pearson’s coefficient. To achieve this, the survey data was exported from the Qualtrics application to a SPSS format. A new variable was created to represent the “total number of steps” in the service delivery process in which respondents participated. This variable was created using the SUM function and adding the previous 7 independent variables that represented each part of the service delivery process. The variable “continuing education received” was recoded to have the value “1” representing respondents that received continuing education and the value “0” representing respondents that did not receive continuing education in the variable’s value definition. To determine Pearson’s coefficient, a coefficient matrix was created.

Results

The survey received 71 responses from four out of five regions of Pakistan. Related to the primary objective, 53.5% of respondents provide AT. More than half of the respondents were 25–34 years old (56.8%) and worked in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (61.5%). 56.4% of respondents were physiotherapists, while the rest of the respondents were community-based healthcare workers, prosthetists/orthotists, and administrative professionals. Few respondents (5.4%) mentioned they had a disability or used an assistive product. Most respondents had 0–3 years of experience in their profession (45.9%) and a graduate degree (36.1%). In terms of assistive technology education, most individuals (42.1%) received their education in school and many others (36.8%) received it in the format of continuing education workshops or seminars.

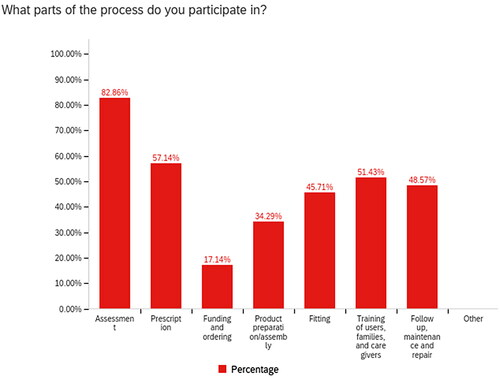

demonstrates provider adherence to a standard assistive technology service delivery process. The funding (17.2%) and product assembly (34.3%) steps were the two elements of the process that had the least amount of participation. In contrast, the majority of providers participated in the assessment (82.9%) and prescription (57.2%) steps. Only three out of thirty-eight (7.9%) individuals that prescribed assistive technology participated in all parts of the service delivery process.

Figure 1. Provision process participation.

There were few associations between providers’ characteristics and adherence to the assistive technology service delivery process. There was a weak correlation between total number of steps and continuing education (r = 0.22), total number of steps and experience level (r = 0.24), and total number of steps and education level (r = 0.15) ().

Table 1. Correlations between total number of steps participated in, experience level, education and continuing education received.

The three respondents that indicated they fully adhere to the service delivery process (participate in 100% of steps) were located in the same region (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) but have different occupations (physiotherapist, community-based healthcare worker, and a prosthetist/orthotist), range of experience (0–20 years of experience), and education levels (high school-undergraduate degree). All three respondents indicated that they have received formal training, continuing education, and shadowing experiences.

Discussion

Only a slight majority of respondents provide assistive technology. This may be due to the majority of respondents being physiotherapists. The provision of assistive technology is not required for every physiotherapist in training nor consistently in the scope of practice [Citation15]. This may also be associated with why the majority of respondents had a graduate degree since a five-year degree with one year of residency is typically required to become a physiotherapist [Citation15–17]. Most participants lived in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa which is among the most populated and wealthiest Pakistani provinces where assistive technology may be more prevalent and accessible [Citation18]. Additionally, the organizations that were contacted through convenience sampling methods are largely located there. Considering most of Pakistan’s working class is categorized as young, where 38% of the population is between 15 and 34, the survey sample was generally representative of the workforce. [Citation19]. In general, the lack of participation of assistive technology providers in the survey is indicative of a significant need in the field.

Related to the secondary objective, to determine if the individuals that provide assistive technology adhere to a standard assistive technology service delivery process, it is evident that participation in all steps is inconsistent. A minority of the respondents participated in funding. This may be because most clients pay out of pocket for assistive technology in Pakistan, therefore providers are not as engaged in this part of the process [Citation20]. Currently in Pakistan and other lower income countries the production of assistive technology is difficult due to production costs, even if there are ample resources [Citation21,Citation22]. If policies are implemented to lower production cost or enable government coverage of assistive technology, Pakistan may reap economic benefits through more participation in the workforce among people with disabilities [Citation23].

Related to the third objective, few associations exist between process adherence and provider characteristics. Out of all the variables, the total number of steps and education had the weakest association. This is surprising as respondents learned to participate in the service delivery process mainly through schooling, then continuing education or shadowing on the job. Based on the results, it can be assumed that individuals are trained in various ways, yet they are still not participating in more parts of the assistive technology service delivery process. This may infer there may be opportunities to strengthen assistive technology education, continuing education modules, and professional development in the workplace. This may be due to lack of information about the service delivery process being included in education, continuing education and the workplace. It is possible that there are other characteristics that contributed to adherence to the service delivery process, such as the steps in the service delivery process not being part of professional training. It would be interesting to investigate the association of number of steps and factors such as location, occupation, or whether a provider has a disability which were not included in this study’s analysis due to limited responses.

Recommendations for increasing awareness and engagement in the field

Limited physical resources, funding, and time constraints may be why assistive technology education has not yet been included in curricula for entry-to-practice students or clinicians [Citation24]. One barrier that may be easier to address is the lack of awareness among educators in rehabilitation programs [Citation24]. Online training may be a mechanism to address assistive technology awareness, knowledge, and skill gaps. One study demonstrated that ongoing education to physical therapists for the management of neck pain significantly reduced disability for patients as well as the number of follow-up visits [Citation25]. This shows that continuing education may play a significant role in improving patient outcomes. Several organizations offer continuing education accredited by the International Association for Continuing Education and Training (IACET) which provides assurance of quality training that meets established standards including the Rehabilitation Engineering Society of North America and Assistive Technology Industry Association [Citation26–28]. The World Health Organization also publishes training and professional development open-source resources according to a quality assurance process and recently released the Training in Assistive Products (TAP) [Citation29]. Continuing education is beneficial in helping professionals adapt to change and stay up to date with the advancements in their industry [Citation30].

Based on a rapid review, mass media marketing campaigns, public deliberation methods, eHealth interventions, and social media are effective in raising public awareness and promoting engagement in general health issues [Citation31]. Educating others through these campaigns may inspire users to advocate for their needs leading to increased funding for education and resources to provide quality assistive technology products and services. Providers can educate users on the many nonprofit organizations and government organizations in Pakistan dedicated to serving individuals with disabilities, such as NOWPD, NDF Pakistan, and Darul Sukun [Citation32–34]. These organizations are focused on empowering individuals with disabilities through education, skills development, and other initiatives. There are also ample international resources designed to raise awareness about specific types of assistive technology. One example is the Wheelchair Service Training Packages, developed by the World Health Organization, which includes training manuals, participant workbooks, presentations, videos, and posters [Citation35] and follow-on interactive resources developed by the International Society of Wheelchair Professionals [Citation36–40].

Policies help to increase awareness for individuals with disabilities’ needs and rights. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities defines the steps each country needs to take to ensure individuals with disabilities have fully realized human rights including the development of policies that ensure individuals with disabilities are to be treated equally [Citation41]. Pakistan ratified the CRPD in July 2011, therefore agreeing to work towards equal participation in society and removing barriers to inclusion [Citation42]. In 1992, the United Nations established the International Day of Persons with Disabilities [Citation43]. This day provides governments an opportunity to support activities that increase awareness of disability issues. Pakistani providers can work with organizations to create events on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities that raise awareness about the types of technology that can increase the independence of the citizens of Pakistan. This increase in awareness may help the public understand the unseen needs of people with disabilities and may empower stakeholders to develop a more equitable assistive technology delivery system.

Future work

A follow-on qualitative study could help to improve understanding of adherence to service delivery steps. Once these reasons are identified, a plan should be drafted to determine how to overcome these barriers.

Future studies should investigate if there is a positive correlation between a provider’s participation in all parts of the service delivery process in Pakistan and positive client outcomes. Although studies show that participation in the service delivery process leads to satisfaction of the user with an assistive technology device, it is important to determine if that is still the case with the current service delivery system in Pakistan and how satisfaction of the user can be improved [Citation44].

In order to improve the state of service delivery in Pakistan, an analysis of current interventions in the service delivery process should be implemented. Once these interventions are identified, outcome measures should be facilitated to measure the state of the service delivery process before and after interventions are implemented to determine their benefit.

Limitations

This survey was developed to evaluate the assistive technology service delivery practice of Pakistani providers. The findings have limited generalizability due to a relatively homogeneous sample. Despite distribution across each state in Pakistan, a majority of the responses are from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. This region contains almost 12% of Pakistan’s population, of which most live in rural locations [Citation45], so it is not an accurate representation of the rest of Pakistan’s service delivery practice. Another limitation is that a majority of the respondents are physiotherapists and very few are community-based healthcare workers. More responses representative of other professions that commonly include assistive technology in their scope of practice may have provided an opportunity for further data analysis. Individuals that did not acquire an education in Pakistan through traditional methods were also excluded from this study. However, based on the net migration of Pakistan being −0.921 per 1000 population, the number of individuals excluded is likely to be very low [Citation46]. An additional limitation is that the survey was in English so individuals that are not able to read English were not able to provide input. The last limitation is that this survey was distributed online through email, Facebook, and Messenger. Thus, respondents who do not actively use these online services would not have been invited to participate in the survey.

Conclusion

This study concluded that approximately half of the respondents provide assistive technology, those who do have varied adherence to a standard service delivery process, and that there is little association between a provider’s personal characteristics (e.g., education, experience level) and their adherence to such a process. This suggests there is opportunity to raise awareness of the importance and provide evidence of impact of assistive technology and increase interventions to support education and implementation of service delivery processes in Pakistan.

Future studies should explore service delivery education through continuing education and increased shadowing experiences for younger professionals, particularly in the physiotherapy department of universities, as assistive technology may most commonly be represented in their scope of practice [Citation47–50]. Outside the classroom, providers should explore the implementation of public events that educate users on assistive technology, self-advocacy, and resources for individuals with disabilities. Lastly, future studies should focus on a deeper analysis of the funding process to improve service delivery in Pakistan as this step was least followed by the responding providers in this study [Citation51]. Research may also provide additional evidence of the impact and return on investment of appropriate assistive technology service delivery by measuring the outcomes of clients who have been served by providers who are following a standard service delivery process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [MG], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. World Report on Disability [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2011. [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability.

- World Bank. Disability Inclusion Overview [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2022. [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability.

- WHO. Assistive technology: fact sheet [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2016. [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/assistive-technology/en/

- World Health Organization, & United Nations Children’s Fund. Global report on assistive technology. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2022.

- de Witte L, Steel E, Gupta S, et al. Assistive technology provision: towards an international framework for assuring availability and accessibility of affordable high-quality assistive technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(5):467–472. doi:10.1080/17483107.2018.1470264.

- Brandt Å, Hansen EM, Christensen JR. The effects of assistive technology service delivery processes and factors associated with positive outcomes - a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(5):590–603. doi:10.1080/17483107.2019.1682067.

- WHO. Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment tool (rATA) [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland) World Health Organization; 2022. [cited 2022 July 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-ATM-2021.1.

- WHO. Rehabilitation 2030 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2017. [cited 2022 July 11]. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/health-topics/rehabilitation/call-for-action/rehab2030meetingreport_plain_text_version.pdf?sfvrsn=891ff06f_5.

- WHO. Rapid assistive technology assessment in Pakistan. World Health Organization; 2022. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/assistive-technology-2/base-line-survey-in-pakistans.pdf?sfvrsn=3ed8c9a8_11.

- World Health Organization. Summary report on the consultative meeting on improving access to assistive technology in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. (No. WHO-EM/HMS/038/E). Islamabad (Pakistan): World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2018.

- Salman A, Torrens GE, Iftikhar H, et al. The influence of social context on the perception of assistive technology: using a semantic differential scale to compare young adults’ views from the United Kingdom and Pakistan. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(5):563–576. doi:10.1080/17483107.2019.1646819.

- Asghar S, Torrens G, Harland RG. Cross-cultural influences on the semantics ascribed to assistive technology product and its envisaged user. Presented at The Asia Conference on Media, Communication & Film 2018, Tokyo, Japan, 2018 October 9–11.

- Ripat J, Booth A. Characteristics of assistive technology service delivery models: stakeholder perspectives and preferences. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(24):1461–1470. doi:10.1080/09638280500264535.

- Disability Support International. Pakistan | Ds-International [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Ds-International; 2022. [cited 2022 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.ds-international.org/pakistan.

- Sarwar M, Khalid MT. Emerging responsibility of a physiotherapist in the healthcare system for an individual, family, community and country. Int J Inform Educ Technol. 2015;1(3):99–104. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350754714_Emerging_Responsibility_of_a_Physiotherapist_in_the_Healthcare_System_for_an_Individual_Family_Community_and_Country

- Adeel M, Chaudhry A. Physical therapy students’ perceptions of the educational environment at physical therapy institutes in Pakistan. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2020;17:7. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.7.

- Curriculum of Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT): 5-years degree programme. [Internet], Karachi(Pakistan), Higher Education Commission. Islamabad: Higher Education Commission; 2010-2011. [cited 2019 Dec 5]. Available from: https://hec.gov.pk/english/services/universities/RevisedCurricula/Documents/2010-2011/PhysicalTherapy-2010.pdf.

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Development_Statistics_2020. [Internet], Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; 2020 [cited 2022 Jul 22] Available from: https://kp.gov.pk/uploads/2021/08/Development_Statistics_2020.pdf.

- Imtiaz A. Pakistan economic survey 2022–2023. Economic Adviser’s Wing Finance Division, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad, Pakistan; 2023.

- Desideri L. Assistive technology service delivery for children with multiple disabilities [dissertation]. Maastricht (Netherlands): University of Maastricht; 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301228352_Assistive_technology_service_delivery_for_children_with_multiple_disabilities_a_family-centred_approach_to_assure_quality.

- Begum T. National language dilemma and its potential role in nation building: academicians’ perception in Pakistan. Power and Education. 2022;14(2):186–192. doi:10.1177/17577438221080262.

- Shi G, Ke S, Banozic A. The role of assistive technology in advancing sustainable development goals. Front Polit Sci. 2022;4:859272. doi:10.3389/fpos.2022.859272.

- Albala SA, Kasteng F, Eide AH, et al. Scoping review of economic evaluations of assistive technology globally. Assist Technol. 2021;33(sup1):50–67. doi:10.1080/10400435.2021.1960449.

- Burrola-Mendez Y, Kamalakannan S, Rushton PW, et al. Wheelchair service provision education for healthcare professional students, healthcare personnel and educators across low- to high-resourced settings: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil Assis Technol. 2023;18(1):67–88. doi:10.1080/17483107.2022.2037757.

- Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Brennan GP, et al. Does continuing education improve physical therapists’ effectiveness in treating neck pain? A randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 1 January 2009;89Issue(1):38–47. doi:10.2522/ptj.20080033.

- RESNA > Certification > Continuing Education [Internet]. Washington (DC): Rehabilitation Engineering Society of North America. [cited 2022 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.resna.org/Certification/Continuing-Education.

- Learning Center CEUs - Assistive Technology Industry Association [Internet]. Chicago(IL), Assistive Technology Industry Association; [cited 2022 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.atia.org/learning-center-ceus/.

- About the CEU – IACET. [Internet]. Sterling (VA): International Association for Continuing Education and Training; [cited 2022 Jul 25]. https://www.iacet.org/standards/ansi-iacet-2018-1-standard-for-continuing-education-and-training/continuing-education-unit-ceu/about-the-ceu/.

- Training in Assistive Products – Online modules for community-level personnel and users of assistive products. [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland), Training in Assistive Products – Online Modules for Community-Level Personnel and Users of Assistive Products; World Health Organization. [cited 2022 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.gate-tap.org/.

- Laal M, Salamati P. Lifelong learning; why do we need it? - ScienceDirect. ScienceDirect.Com | Science, Health and Medical Journals, Full Text Articles and Books. Science Direct. 2012. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042811030023.

- Seymour J. The impact of public health awareness campaigns on the awareness and quality of palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S1):S30–S36. PMID: 29283867; PMCID: PMC5733664. doi:10.1089/jpm.2017.0391.

- NOWPDP - Leading disability organization in Pakistan [Internet]. Pakistan, NOWPDP - Leading Disability Organization in Pakistan; NowPD. [cited 2022 Dec 10], Available from: https://www.nowpdp.org.pk/home.

- NDF Pakistan. [Internet]. Nawabshah(Pakistan), NDF Pakistan; Nabila Mughal. [cited 2022 Dec 10]. Available from: https://ndfpakistan.org/

- Darul Sukun - A Centre of Peace & Love. [Internet]. Darul Sukun; Darul Sukun; 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 10]. Available from: https://darulsukun.com/

- Fung KH, Rushton PW, Gartz R, et al. Wheelchair service provision education in academia. Afr J Disabil. 2017;6:340. PMID: 28936415; PMCID: PMC5594266. doi:10.4102/ajod.v6i0.340.

- Munera S, Goldberg M, Kandavel K, et al. Development and evaluation of a wheelchair service provision training of trainers programme. Afr J Disabil. 2017;6:360. doi:10.4102/ajod.v6i0.360.

- Gartz R, Goldberg M, Miles A, et al. Development of a contextually appropriate, reliable and valid basic Wheelchair Service Provision Test. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(4):333–340. doi:10.3109/17483107.2016.1166527.

- Burrola-Mendez Y, Goldberg M, Gartz R, et al. Development of a hybrid course on wheelchair service provision for clinicians in international contexts. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199251. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0199251.

- Rushton PW, Fung K, Gauthier M, et al. Development of a toolkit for educators of the wheelchair service provision process: the Seating and Mobility Academic Resource Toolkit (SMART). Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):14. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-0453-6.

- Ardianuari S, Goldberg M, Pearlman J, et al. Development, validation and feasibility study of a remote basic skills assessment for wheelchair service providers. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2022;17(4):462–472. doi:10.1080/17483107.2020.1799250.

- Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Treaty Series. 2006;2515:3. [Internet] [cited 30 Nov, 2022]. Available from: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=080000028017bf87&clang=_en

- Pakistan Ratifies the CRPD [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): International Disability Alliance; 2011 [cited 2022 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/blog/pakistan-ratifies-crpd.

- Fisher KR, Purcal C. Policies to change attitudes to people with disabilities. Scand J Disabil Res. 2017;19(2):161–174. doi:10.1080/15017419.2016.1222303.

- Larsson Ranada Å, Lidström H. Satisfaction with assistive technology device in relation to the service delivery process-a systematic review. Assist Technol. 2019;31(2):82–97. doi:10.1080/10400435.2017.1367737.

- About Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. [Internet]. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa(Pakistan), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Official Web Portal, Khyber Pakhtunwa Information Technology Board. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. Available from: https://kp.gov.pk/page/know_khyber_pakhtunkhwa.

- Pakistan Net Migration Rate 1950–2022 | MacroTrends. Macrotrends | The Long Term Perspective on Markets; Macrotrends LLC. United Nations - World Population Prospect. 2010–2023 [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/PAK/pakistan/net-migration#:∼:text=The%20current%20net%20migration%20rate,a%204.42%25%20decline%20from%202019.

- Sarver WL, Seabold K, Kline M. Shadowing to improve teamwork and communication: a potential strategy for surge staffing. Nurse Lead. 2020;18(6):597–603. Epub 2020 Jul 19. PMID: 32837350; PMCID: PMC7369004. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2020.05.010.

- Marasinghe K, Lapitan J, Ross A. Assistive technologies for ageing populations in six low-income and Middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ. 2015; 4. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.3389/fpos.2022.859272/full

- The Difference Between Continuing Education and Professional Development. [Internet]. Orange Beach (AL). An Online University with Unlimited Possibilities | Columbia Southern University, Colombia Southern University. 2021 [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.columbiasouthern.edu/blog/blog-articles/2021/april/continuing-education-and-professional-development/.

- Kusnoor AV, Stelljes LA. Interprofessional learning through shadowing: insights and lessons learned. Med Teach. 2016;38(12):1278–1284. PMID: 27647042; PMCID: PMC5214521. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2016.1230186.

- Ahmad M, Khan AB, Nasem F. Policies for special persons in Pakistan: analysis of policy implementation. Berkley J Soc Sci. 2011;1(2). https://www.humanitarianlibrary.org/sites/default/files/2014/02/Feb%201.pdf