Abstract

Purpose of the article

The aim of this study was to determine user satisfaction with manual wheelchairs in the United Kingdom and to determine areas that could be improved to help drive future design and development.

Materials and Methods

Manual wheelchair users, aged 18-65 years old living in the United Kingdom, were invited, to complete an online cross-sectional questionnaire. The link to the questionnaire was distributed using a range of methods to charities, organisations and wheelchair user groups via invitation by email and social media. Responses were gathered from 122 respondents and analysed using descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation and content analysis.

Results

Respondents felt comfort (39.3%), weight (35.4%), manoeuvrability (34.3%) and durability (30.7%) were the most important features of a wheelchair. Seventy percent of respondents that were “not at all satisfied” with their current wheelchair were fitted by the National Health Service (NHS, X2 = 42.39, p < 0.001). Ninety percent of respondents who were “not at all satisfied” with their current wheelchair experienced issues with comfort (X2 = 17.82, p = 0.001). Sixty percent who were “not satisfied at all” with their wheelchair had not chosen their wheelchair (X2 = 25.15, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Wheelchair satisfaction was largely determined by comfort, location of the users’ wheelchair fitting (for example the NHS) and users choosing their own wheelchair. Future wheelchair designs should utilise a user centred and inclusive design approach to cater for a wider range of individual needs and requirements.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Manual wheelchair users in the UK are more likely to be satisfied with their wheelchair if they were fitted by a service other than the National Health Service (NHS), chose their own wheelchair and experience no issues with comfort.

Wheelchair fittings should account for individual differences and requirements as no model or size can cater for all users. This may help increase wheelchair satisfaction and comfort for the user.

Manufacturers should consider more inclusive designs to cater for a wider range of users, for example accommodating female users at different stages throughout their lifetime.

Introduction

To function independently, manual wheelchair users must acquire a variety of wheelchair skills to manage physical barriers they face in daily life. From curbs on pavements to steps into shops, the man-made environment is so often designed and built for ambulant individuals with little consideration for wheelchair users [Citation1]. However, the surrounding environment may not be the only obstacle wheelchair users have to encounter daily. For some users their own wheelchair provides a further hindrance making getting around even more difficult.

Manual wheelchairs become an extension of self [Citation2], are key for survival [Citation3], replace the function of the lower limbs and thus ideally must be custom fit to the user [Citation4]. They are an important physical aid allowing users to live an independent life [Citation3]. A wheelchair is a highly personalised device that ultimately should be chosen with precision and care. Cumbersome, ill-fitting and uncomfortable wheelchairs are likely to have a negative impact on the user’s health, mobility and overall quality of life [Citation5]. Wheelchair prescription should comprise of a series of stages, involving assessment, education, skills training and regular follow-ups [Citation6]. Difficulty when prescribing an individual a wheelchair can often lead to longer term issues for the user.

Often thrust into becoming a wheelchair user, when an individual is first prescribed a wheelchair, they are unlikely to know what their wheelchair requirements are [Citation5]. The requirements of a wheelchair user do not remain static and are highly likely to change over time predominantly due to both aging and decreased mobility owing to degenerative conditions [Citation7], or as physical fitness and wheelchair skills develop over time. Initial prescription of wheelchairs is often undertaken by wheelchair services or by wheelchair manufacturers. The former is likely to vary between regional location, expertise available and economic cost [Citation8]. Whilst the latter would be very knowledgeable about their own products, commercial bias may be apparent when prescribing a wheelchair, hence the wheelchair prescribed may not be solely driven by the wheelchair user’s needs and requirements. Importantly, individuals involved in wheelchair prescription are often not wheelchair users themselves so are unlikely to intrinsically understand the needs of the user [Citation5]. Therefore, a wheelchair may need to provide additional support and manoeuvrability than what was initially required and prescribed. Consideration also needs to be given to the practicality and economic cost to the user throughout their lifetime with their changing needs.

When assessing the quality of a manual wheelchair, an important aspect is the satisfaction of the wheelchair user [Citation9]. Levels of satisfaction with assistive technology have been predominantly investigated using the Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology-Version 2.0 (QUEST) questionnaire. Studies using the QUEST have reported that ease of use and comfort are important aspects supporting high levels of satisfaction for wheelchair users with a spinal cord injury and participants from specific nationalities [Citation9–13]. Satisfaction with wheelchair features is associated with improvements in quality of life and participation, whilst an inappropriate wheelchair can be more limiting than the impairment and/or environment [Citation3,Citation9,Citation13]. Whilst some studies have reported a high proportion of participants do have high satisfaction with their wheelchairs, participants have instead expressed a larger dissatisfaction with service related aspects, such as provision, repair, maintenance, and follow-up [Citation3,Citation9,Citation13,Citation14]. Nevertheless, limited information exists on satisfaction of manual wheelchair users based in the UK and across user groups with different medical conditions or injuries. Additionally, a deeper understanding of the drivers of wheelchair satisfaction and areas where improvement are required is currently lacking, which cannot be gathered when using the QUEST 2.0.

Wheelchairs that accommodate wheelchair users’ needs facilitate their interaction with the surroundings and promote better wheelchair satisfaction and quality of life [Citation1,Citation8]. Therefore, the aim of this study is to increase the understanding of wheelchair satisfaction and areas of improvement for manual wheelchairs users in the UK to help drive future design and development.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study used a quantitative with acceptance of qualitative data mixed methods design. Multiple choice questions and free text option questions (using content analysis) were quantified, whilst broader insights of the opinions of respondents on future wheelchair design were not quantified to prevent a loss of information and meaning.

The online cross-sectional questionnaire was developed on the digital platform Google Forms. Manual wheelchair users, aged 18–65 years old living in the United Kingdom were asked to voluntarily complete the questionnaire. This age range was chosen to focus on respondents aged from early adulthood (18–44 years old) to late middle age (45–65 years old) (Erikson, 1968). The author plans to conduct a separate study for older adult wheelchair users (over 65 years) to better understand whether the drivers for wheelchair satisfaction are the same for older adults compared to whose in early to mid adulthood.

The link to the questionnaire was distributed using a range of methods to charities, organisations and wheelchair user groups via invitation by email, LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter. All respondents completed the questionnaire between November 2020 and March 2021. This time period was chosen to account for any potential impact of the Christmas holiday period and the COVID-19 pandemic on the response rate.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire aimed to provide a holistic overview of wheelchair user’s satisfaction and related aspects, plus key areas of improvement for end users. As such, a questionnaire was created to target these research aims. The questionnaire was not tested for validity and reliability prior to use, however, a pilot questionnaire was tested with a group of 25 wheelchair users to check readability. Adjustments were made to the wording of items, multiple choice options and a reduction in the number of free-text questions to improve overall clarity and understanding of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was split into 3 sections consisting of a total of 23 questions. These 3 sections were: (1) respondent demographics, (2) wheelchair usage and prescription, and (3) importance and improvements of their current wheelchair. In Section 1 respondents were asked about their age, gender, weight, and diagnoses. Section 2 was related to the respondent’s wheelchair usage and prescription, including questions on their typical hours of usage, reasons for choice of wheelchair and fitting of wheelchair. Section 3 asked respondents to select features they felt were the most important to them as a wheelchair user and potential improvements to their current wheelchair, including any potential issues with discomfort (body locations where comfort was experienced and severity of the discomfort). The questionnaire contained 19 checkbox questions, 1 likert scale question (wheelchair satisfaction) and one rating question (severity of the discomfort). An additional two questions contained a free-text option, where the respondent was asked to provide further information regarding improvements of their current wheelchair and future wheelchair design.

Respondents

A participant information sheet was provided as part of the questionnaire and consent was implied by the completion of the questionnaire. Ethics was granted by Nottingham Trent University Ethics Committee (ethics number: 18 19-71). A total of 125 questionnaires were answered, however three were excluded because they were duplicate (exact same responses and unique ID), therefore there were a total of 122 respondents to the questionnaire. To ensure confidentiality, all data was anonymised and no identifying data was linked to the collected dataset.

Statistical analysis

Data from completed questionnaires were entered into SPSS (Version 26) and analysed using descriptive statistics (means and proportions) and cross tabulation (chi-square). Multiple responses were allowed for some questions with the percentages and n related to the total number of responses and not the total number of respondents for the questionnaire (n = 122). The focus of the cross-tabulation analysis was to analyse the relationship between: (1) the location of the wheelchair fitting and satisfaction with current wheelchair, (2) the amount of comfort and satisfaction with current wheelchair and 3) whether the respondents chose their wheelchair and satisfaction with current wheelchair.

For one of the questions using the free-text option (improvement to current wheelchair), content analysis was undertaken and involved identifying and coding information from the respondent’s comments to create a series of themes that represented the data. The themes were then quantified. To increase the validity of the study and to guard against perceptual biases [Citation15], themes were verified and discussed with another researcher. For the other free text question (design improvements), themes were identified but not quantified in order to provide greater insight on this topic. Quantifying these results would have resulted in the loss of information and context in relation to respondent’s opinions on future wheelchair design.

Results

Respondent demographics

The survey received 122 responses. The demographics of the respondents are shown in .

Table 1. Demographics of respondents (n = 122).

Wheelchair usage and prescription

Typical wheelchair usage of the respondents is shown in .

Table 2. Typical wheelchair usage of respondents and weight of current wheelchair (n = 122).

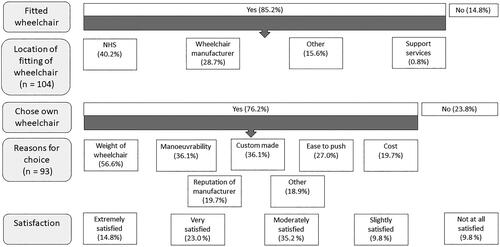

shows responses regarding the respondent’s current wheelchair, relating to the fit, the reasons for choosing their wheelchair and their overall satisfaction with their wheelchair. The percentage of respondents that reported their requirements for their wheelchair had changed since they purchased their current wheelchair was 50.8% (n = 62), with varying reasons for the change. A subsequent injury or illness, degenerative condition or other, stated as the reason for requirement changes by 14.0% (n = 17) of respondents, whilst 5.8% (n = 7) stated the reason was age related decline in function. In contrast, 19.0% (n = 23) reported greater confidence in wheelchair skills, 17.4% (n = 21) greater independence and 15.7% (n = 19) an increase in physical fitness for why changes were required for their wheelchair.

Figure 1. Number of responses to questions about respondent’s current wheelchair. Questions related to the fitting, the reasons for choosing their wheelchair and users overall satisfaction with their wheelchair. Unless stated otherwise in the figure, all respondents (n = 122) answered each question. Respondents could select multiple responses for the question: reasons for choice of wheelchair.

Importance of features and improvements of current wheelchair

There was a significant association (X2 = 42.39, p < 0.001) between where a respondent’s wheelchair was fitted and their satisfaction with their wheelchair. Seventy percent of respondents that were “not at all satisfied” with their current wheelchair were fitted by the National Health Service (NHS), whilst 41.2% who were “extremely satisfied” with their current wheelchair were fitted by a service other than the NHS, manufacturer or support services. There was a significant association (X2 = 17.82, p = 0.001) between issues with comfort and satisfaction with their current wheelchair. Ninety percent of respondents who were “not at all satisfied” with their current wheelchair experienced issues with comfort, compared to 64.7% of respondents who were “extremely satisfied” with their current wheelchair and did not experience any issues with comfort. A significant association was observed between those respondents who chose their wheelchair and satisfaction with their wheelchair (X2 = 25.15, p < 0.001). All respondents who rated they were “extremely satisfied” with their current wheelchair had chosen their wheelchair, compared to 60.0% of respondents who were “not satisfied at all” had not chosen their wheelchair.

Respondents felt that comfort (n = 110, 39.3%), weight (n = 99, 35.4%), manoeuvrability (n = 96, 34.3%) and durability (n = 86, 30.7%) were the most important features for them as a wheelchair user. Whilst aesthetics (n = 46, 16.4%), adjustability (n = 35, 12.5%) and foldability (n = 29, 10.4%) were less important.

Weight was one of the most popular areas of improvement respondents felt were necessary for their current wheelchair (n = 32, 18.6%), whilst improving a specific component was also highly popular (n = 46, 26.7%). Selected design improvements suggested by respondents are shown in .

Table 3. Design improvements suggested by respondents.

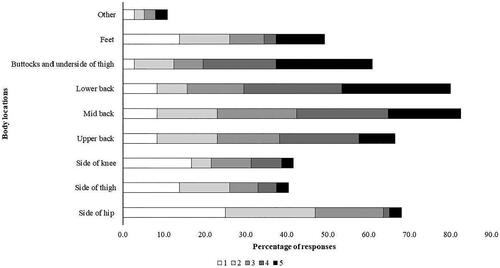

The percentage of respondents that stated they suffered from comfort issues whilst in their wheelchair was 63.1% (n = 77). shows the regions of discomfort at different body locations and severity of the discomfort at each region. To attempt to alleviate any discomfort most respondents used extra cushioning in their wheelchair (n = 30, 34.1%), but a large majority of respondents stated that they didn’t use anything to help (n = 45, 51.1%).

Figure 2. Regions of discomfort at different body locations and severity of the discomfort. Respondents were asked to rank the severity of the discomfort at each region, 1 = little discomfort, 5 = maximum discomfort.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to increase our understanding of wheelchair satisfaction and areas of improvement for manual wheelchairs users in early adulthood to late middle age in the UK. This study presents the demographics of 122 manual wheelchair users living in the UK aged 18-65 years old, alongside their wheelchair type, usage and suggested preferences and improvements of their current daily wheelchair. Wheelchair users were the most satisfied with their wheelchair if they had chosen their own wheelchair, were fitted by services outside of the NHS and had no issues with comfort. These findings signify that wheelchair users need to have greater autonomy when choosing their wheelchair, and fittings need to account for individual differences and requirements as no model or size can cater for all users [Citation16]. For example, accounting for variation in body size and shape for female wheelchair users or mothers with children (). A limited range of wheelchairs with limited options will likely result in an inappropriate wheelchair for users [Citation16].

Most wheelchair users are thrust into becoming a wheelchair user fairly quickly and therefore do not know what their specific wheelchair requirements are [Citation5]. Hence, wheelchair users must rely on fitters providing a thorough analysis of their body size, shape and current needs to prescribe a satisfactory wheelchair. However, the results from this questionnaire seem to suggest that wheelchair users do not feel a thorough analysis occurred when they were fitted by the NHS. The whole prescription process should consist of several steps that include individual assessment of specific needs of the user, wheelchair fit and prescription, wheelchair skills training, education on maintenance of the wheelchair and regularly follow-ups to check fit, repairs and usage [Citation6,Citation16,Citation17]. How many wheelchair users undertake each one of these steps when being prescribed a wheelchair is unknown, but previous studies have reported user dissatisfaction with follow up, maintenance and repairs of their wheelchairs [Citation9,Citation18,Citation19]. Poor provision of the whole prescription process could help explain why such a large majority of the respondents had issues with comfort (63.1%). This is even more important when the requirements of a wheelchair change over time, as experienced by 50% of the respondents in the present study. Therefore, the needs and fit of the wheelchair is likely to also change. Utilising a user-centred approach where the wheelchair user feels involved with the wheelchair prescription process and the device meets their expectations could impact user satisfaction [Citation20]. Previous literature, although based on wheelchair users in the US and Sweden, has shown that wheelchair users are often not taught about their wheelchair, for example, how to care, maintain and adjust their wheelchair [Citation17,Citation21]. Hence users are unlikely to be able to determine their own adjustments or maintenance when required [Citation17], potentially leading to issues with comfort. A more thorough prescription, assessment and education process with follow up assessments [Citation16], conducted without long wait times [Citation3], undertaken in the user’s home and surrounding environment may help reduce issues with comfort. This will ensure the wheelchair is suitable for the user for a longer period of time, ensures individual freedoms [Citation3] and enables users to adjust and maintain their wheelchair themselves.

Out of the respondents who were not satisfied with their wheelchair, 90.0% experienced issues with comfort, indicating that comfort is a large driving force for wheelchair satisfaction, supporting findings by previous studies [Citation9,Citation10,Citation19]. The majority of respondents did not use anything to alleviate their discomfort (51.1%), which may indicate that wheelchair users expect to experience discomfort when using their wheelchair or they are not sure what is available to improve their comfort. The greater severity of discomfort at the buttocks, underside of thigh and lower back could be related to the typical regions at which wheelchair users experience pressure sores, occurring at the ischial tuberosities and the sacrum [Citation22–24] and where users feel most vibration during use [Citation25]. Adaptations to wheelchair design should aim to reduce discomfort at these regions, even if users are only using their wheelchair for a short period of time. Similarly to fit, if users are offered and engage with a more thorough prescription, assessment and education process they might be better placed to alleviate discomfort before the discomfort impacts quality of life and leads to medical complications, such as pressure sores. Greater comfort will lead to higher wheelchair satisfaction, with users with higher wheelchair satisfaction more likely to use their wheelchairs for longer [Citation10]. In the present study the respondents weren’t asked whether they were currently or had previously suffered from any pressure sores, if they are currently experiencing any pain or where they had had pressure sores previously. It has been reported that a lack of support provided by the wheelchair is strongly associated with pain, and pain and instability show associations with dissatisfaction with sitting in a wheelchair [Citation26]. Lack of support relates to the fitting of the wheelchair to the user, again stressing the importance of a thorough wheelchair fitting process [Citation26]. Pain and discomfort may be reduced following appropriate interventions [Citation27], but how this can be achieved is likely individually driven. For instance, discomfort at one region might be alleviated by removing support in another part of the wheelchair or providing cushioning at another region to alter positioning. Therefore, locations of discomfort for manual wheelchair users needs to be explored further, focusing on how this discomfort could be alleviated and the relationship between discomfort, pain, instability and satisfaction across medical conditions and injuries.

Although not investigated in the present study, discomfort and potential pain could be further exaggerated by ride discomfort, which is likely to differ between wheelchairs [Citation28]. Discomfort experienced by wheelchair users is likely to vary throughout the day and be dependent on the amount of time spent stationary, propelling the wheelchair or travelling over various terrains. Users may experience insecurity [Citation28] in their wheelchairs or large amounts of vibration [Citation25,Citation29] affecting rider discomfort, which is likely to be related to the technical quality and useability of the wheelchair. Future research should incorporate questions on rider discomfort and pain to distinguish the main driver for the user’s discomfort and pain to help guide future wheelchair design.

Similarly, to wheelchair prescription and fitting, respondents felt that wheelchair design was so often not driven or centred on the user (). Respondents want more involvement in the design process to feel their needs are being met by manual wheelchairs currently available to purchase. Acknowledgement by manufacturers that no model or size can cater for all users and more inclusive design should be utilised, in addition to the understanding of the complexity of accommodating individual needs appropriately [Citation18]. Some respondents felt wheelchair design did not accommodate or fitting was not adapted for female body shapes or for women throughout the lifetime, i.e. pregnancy, breastfeeding mothers or women with young children [Citation30]. Previous literature has found that in general females evaluated their wheelchairs more negatively than males and also experience more pain [Citation26], signifying that wheelchair designers need to consider potential gender related differences in relation to anatomy and lifestyles to meet a wider range of users’ preferences and expectations [Citation30,Citation31].

One of the key findings is that the weight of a wheelchair is integral for users and is one of the main reasons users choose their wheelchairs and consider it to be one of the most important features of a wheelchair, supporting findings from previous studies [Citation9–11]. When pushing a lighter wheelchair, less propulsive forces are required resulting in faster speeds, further distances travelled and the use of less energy [Citation32]. This is even more prominent when propelling up an incline. Hence it is recommended that users select the lightest possible wheelchair to maximise efficiency whilst minimising propulsive forces [Citation33]. Lighter wheelchairs tend to utilise wheelchair frames and components manufactured with materials with high strength-weight ratios [Citation34]. These ultra-light wheelchairs are also more expensive to purchase because of the lightweight materials used to build them. However, an improvement in durability should reduce the number of repairs and the associated costs as well as improve the overall manoeuvrability of the wheelchair [Citation34]. Participants in the present study were asked to state, and not directly measure, the approximate weight of their wheelchair, hence participants might have underestimated the total weight of their wheelchair, including all associated parts. Nonetheless, perhaps unsurprisingly, wheelchair users want and need lightweight wheelchairs, that are both durable and easy to manoeuvre. Future wheelchair designs should aim to increase the durability and reduce the weight of wheelchairs to improve manoeuvrability, whilst keeping costs low to enable suitable access to the end user.

The distribution of weight within the wheelchair is also important and optimising weight distribution by wheelchair design or adjustments of the axle will also likely impact propulsion effort and manoeuvrability [Citation35,Citation36]. Modifying wheelchair configuration should aim to optimise the stability of the wheelchair system and improve the biomechanics of manual propulsion, manoeuvrability and comfort of the user [Citation37]. Finding the optimal balance between stability and mobility is integral when prescribing and adjusting a wheelchair, as improving one will impact the other [Citation37]. The best way to achieve the balance between mobility and stability must be based on the user’s functionality, requirements and needs of the wheelchair.

The questionnaire used in this study did not gather extensive information on the respondents’ use of their wheelchair in their home and/or built environment, aside from whether they used the wheelchair inside and/or outside the house. However, a wheelchair that is chosen by the user, provides the correct fit, is comfortable, easy to manoeuvre and durable will not benefit the user if environmental access is not adequate. In contrast, a fully accessible environment, whether inside the home or in the built environment, will be of no benefit to a wheelchair user if their wheelchair is difficult to manoeuvre, does not fit and is uncomfortable [Citation38]. Therefore, both the suitability of a wheelchair and the accessibility of the surrounding environment should be considered for individual wheelchair users, to ensure a perfect marriage between the two [39].

Limitations

Recruitment for this study was through email and groups on social media, which may have resulted in a non-representative sample of wheelchair users. Hence, wheelchair users that are not part of the organisations contacted or are not part of these online groups did not have the opportunity to be involved. In relation to diagnoses, most respondents had a spinal cord injury, but it is difficult to determine if this is representative of the manual wheelchair users in the UK, since this information is not publicly available. It should be noted that the sample was restricted to participants aged 18–65 years old living in the UK. As per the described biases, the findings may not wholly reflect the views of the population group and findings cannot be generalised to wheelchair users outside of the sampled age range.

Although there are questionnaires related to wheelchair satisfaction that have been tested for validity and reliability, namely the QUEST 2.0 and Wheelchair Satisfaction Questionnaire (WSQ) [Citation38], these only cover a select number of items. The present study aimed to provide a holistic overview of manual wheelchair user’s satisfaction and key areas of improvement for end users.

Conclusion

In the present study wheelchair satisfaction was largely determined by comfort, location of the users’ wheelchair fitting and users choosing their own wheelchair. Wheelchair fittings should account for individual differences, current requirements, follow up checks for fit and comfort and acknowledge that the wide range of individual needs cannot be catered for with a limited range of wheelchairs. Future wheelchair designs should aim to reduce the weight of the wheelchair, increase durability and improve manoeuvrability whilst ensuring costs are kept low for the end user. Accordingly, manufacturers should utilise a user centred design approach and involve wheelchair users in the design process, in addition to considering more inclusive designs to cater for a wider range of users, for example female users.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Ruth Boat for her guidance and assistance whilst writing the manuscript. The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Imrie R, Kumar M. Focusing on disability and access in the built environment. Disabil Soc. 1998;13:357–374.

- Cooper RA. Wheelchairs selection and configuration. New York: Demos Medical; 1998.

- Gowran RJ, Clifford A, Gallagher A, et al. Wheelchair and seating assistive technology provision: a gateway to freedom. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(3):370–381. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1768303.

- Cooper RA, Boninger ML, Spaeth DM, et al. Engineering better wheelchairs to enhance community participation. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2006;14(4):438–455. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2006.888382.

- Philips L, Angelo N. Clinical perspectives on wheelchair selection: an overview with reflections, past and present of a consumer. Choosing a wheelchair system. J Rehabil Res Dev Clin Suppl. 1990;1:1–7.

- Stefanac S, Grabovac I, Fristedt S. Wheelchair users’ satisfaction with the prescribed wheelchairs and wheelchair services in Croatia. Coll Antropol. 2019;42:193–198.

- Platts EA. Wheelchair design – Survey of users’ views. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67(5):414–416.

- Smith C, McCreadie M, Unsworth J. Prescribing wheelchairs: the opinions of wheelchair users and their carers. Clin Rehabil. 1995;9(1):74–80. doi: 10.1177/026921559500900112.

- De Groot S, Post MWM, Bongers-Janssen HMH, et al. Is manual wheelchair satisfaction related to active lifestyle and participation in people with a spinal cord injury? Spinal Cord. 2011;49(4):560–565. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.150.

- Samuelsson K, Wressle E. User satisfaction with mobility assistive devices: an important element in the rehabilitation process. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(7):551–558. doi: 10.1080/09638280701355777.

- Sarour M, Jacob T, Kram N. Wheelchair satisfaction among elderly Arab and Jewish patients – a cross-sectional survey. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2023;18(4):363–368. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2020.1853830.

- Marchiori C, Bensmail D, Gagnon D, et al. Manual wheelchair satisfaction among long-term users and caregivers: a French study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(2):181–192. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0092.

- Visagie S, Mlambo T, Van der Veen J, et al. Impact of structured wheelchair services on satisfaction and function of wheelchair users in Zimbabwe. Afr J Disabil. 2016;5:1–11.

- Gallagher A, Cleary G, Clifford A, et al. “Unknown world of wheelchairs” a mixed methods study exploring experiences of wheelchair and seating assistive technology provision for people with spinal cord injury in an Irish context. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:1946–1958.

- LeCompte MD, Goetz JP. Problems of reliability and validity in ethnographic research. Rev Educ Res. 1982;52:31–60.

- World Health Organization. Wheelchair provision guidelines. Report, World Health Organization, Geneva (CH), 2023.

- Hansen R, Tresse S, Gunnarsson RK. Fewer accidents and better maintenance with active wheelchair check-ups: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(6):631–639. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr777oa.

- Bergström AL, Samuelsson K. Evaluation of manual wheelchairs by individuals with spinal cord injuries. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(3):175–182. doi: 10.1080/17483100600573230.

- Larsson Ranada Å, Lidström H. Satisfaction with assistive technology device in relation to the service delivery process—a systematic review. Assist Technol. 2019;31(2):82–97. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2017.1367737.

- Morgan KA, Engsberg JR, Gray DB. Important wheelchair skills for new manual wheelchair users: health care professional and wheelchair user perspectives. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(1):28–38. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2015.1063015.

- Führer MJ, Garber SL, Rintala DH, et al. Pressure ulcers in community-resident persons with spinal cord injury: prevalence and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74(11):1172–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(23)00010-2.

- Thorfinn J, Sjöberg F, Lidman D. Sitting pressure and perfusion of buttock skin in paraplegic and tetraplegic patients, and in healthy subjects: a comparative study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2002;36(5):279–283. doi: 10.1080/028443102320791824.

- Pompeo M, Baxter C. Sacral and ischial pressure ulcers: evaluation, treatment, and differentiation. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2000;46(1):18–23.

- Maeda S, Futatsuka M, Yonesaki J, et al. Relationship between questionnaire survey results of vibration complaints of wheelchair users and vibration transmissibility of manual wheelchair. Environ Health Prev Med. 2003;8(3):82–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02897920.

- Valent L, Nachtegaal J, Faber W, et al. Experienced sitting-related problems and association with personal, lesion and wheelchair characteristics in persons with long-standing paraplegia and tetraplegia. Spinal Cord. 2019;57(7):603–613. doi: 10.1038/s41393-019-0272-6.

- Thyberg M, Gerdle B, Samuelsson K, et al. Wheelchair seating intervention. Results from a client-centred approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(15):677–682. doi: 10.1080/09638280110049900.

- DiGiovine MM, Cooper RA, Boninger ML, et al. User assessment of manual wheelchair ride comfort and ergonomics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(4):490–494. doi: 10.1053/mr.2000.3845.

- Garcia-Mendez Y, Pearlman JL, Boninger ML, et al. Health risks of vibration exposure to wheelchair users in the community. J Spinal Cord Med. 2013;36(4):365–375. doi: 10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000124.

- Greenhalgh M, Rigot S, Eckstein S, et al. A consumer assessment of women who use wheelchairs. J Mil Veteran Fam Health. 2021;7:40–49.

- Lanutti JNL, Medola FO, Gonçalves DD, et al. The significance of manual wheelchairs: a comparative study on male and female users. Procedia Manuf. 2015;3:6079–6085. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.752.

- Beekman CE, Miller-Porter L, Schoneberger M. Energy cost of propulsion in standard and ultralight wheelchairs in people with spinal cord injuries. Phys Ther. 1999;79(2):146–158. doi: 10.1093/ptj/79.2.146.

- Boninger ML, Water RL, Chase T, et al. Preservation of upper limb function following spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2005;28:434–470.

- Gebrosky B, Grindle G, Cooper R, et al. Comparison of carbon fibre and aluminium materials in the construction of ultralight wheelchairs. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(4):432–441. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2019.1587018.

- Lin J-T, Springle S. The impact of wheelchair weight distribution and human physiological fitness on over-ground maneuver. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:92–96.

- Sprigle S, Huang M. Impact of mass and weight distribution on manual wheelchair propulsion torque. Assist Technol. 2015;27(4):226–235. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2015.1039149.

- Medola FO, Elui VMC, Santana C da S, et al. Aspects of manual wheelchair configuration affecting mobility: a review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(2):313–318. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.313.

- Hoenig H, Pieper C, Zolkewitz M, et al. Wheelchair users are not necessarily wheelchair bound. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:645–654.

- Kaye HS, Kang T, LaPlante MP. Mobility device use in the United States. Disability statistics report 14. San Francisco, CA: National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, US Department; 2000. p. 1–60.