ABSTRACT

Inter-municipal cooperation, where two or more local governments jointly provide one or more public services across their jurisdictions, is an increasingly prevalent mode of public administration. In part, this reflects the limited success of prior rounds of privatization and amalgamation reform – and the continuing desire to economize and improve regional coordination. In part, it speaks of the wider policy fashion for seeking collaborative solutions to public problems. This article introduces a special issue on “the drivers and effects of inter-municipal cooperation.” It reviews the current evidence base and the contributions of six papers, and suggests productive avenues for future research.

1. Introduction

Inter-municipal cooperation – an arrangement in which two or more local governments provide one or more public services jointly across their jurisdictions – is an increasingly prevalent mode of public administration at the subnational level (Aldag, Warner, and Bel Citation2020; Bel et al. Citation2023; Blåka, Jacobsen, and Morken Citation2023; Niaounakis and Blank Citation2017; Dixon and Elston Citation2020; Ferraresi, Migali, and Rizzo Citation2018; Teles and; Swianiewicz Citation2018). In the last decade, the incidence of, and range of services subjected to, inter-municipal cooperation (hereafter IMC) has increased markedly – both in countries with long experience of this approach, like Spain, Italy, and France, and in others with little or no such tradition, like the United Kingdom and Ireland. This widening and deepening of interest in IMC is stimulated, in part, by the troubled history of previous local government reforms – notably, the privatization of service delivery and the amalgamation of council jurisdictions, neither of which tended to live up to policymakers’ expectations. The hope is that IMC can somehow “out do” those alternative reform options and offer a more reliable route to performance gains and/or local fiscal sustainability. But the multi-national growth of IMC is also reflective of a wider, more generalized belief in the prevalence of “interdependencies” within contemporary systems of government, and in the need for collaborative responses to achieve collectively what is unattainable individually (Agranoff and McGuire Citation2003; Kettl Citation2006). In the case of IMC, this doctrine, which is not infallible (Elston, Bel, and Wang Citation2023b), advocates that municipalities should pool their resources in order to obtain greater technical efficiency and/or more sensible management of regional externalities than could be achieved autonomously.

The research literature on IMC, which sits at the intersection of public economics, urban studies, economic geography and public administration, has grown significantly in recent years, rapidly catching up with the increased empirical incidence of cooperation. Whereas only six impact evaluations were available for inclusion in Bel and Warner’s review (Citation2015), nearly thirty could be analyzed in Bel and Sebő’s (Citation2021) meta-regression; and there has been no letup in the pace of evaluation since then (Banaszewska et al. Citation2022; Bel and Belerdas-Castro Citation2022; Bel and Elston Citation2023; Blåka, Jacobsen, and Morken Citation2023; Elston, Bel, and Wang Citation2023b, Citation2023b; Luca and Modrego Citation2021; Notsu Citation2024). Three of the six papers included in this special issue continue this important task, extending scientific knowledge on the effects of IMC reform to new policy sectors and performance dimensions, in particular by moving beyond purely “cost-based” analyses to various measures of service quality.

Research on factors that prompt the adoption of IMC has also flourished over the last decade (Arntsen, Torjesen, and Karlsen Citation2018; Bel and Warner Citation2016; Blaeschke and Haug Citation2018; Dixon and Elston Citation2020). And there is an emerging interest in what contributes to the sustenance or decline of these networks over the longer-term (Aldag and Warner Citation2018; Elston, Rackwitz, and Bel Citationforthcoming; Zeemering Citation2018; Zyzak Citation2017). While this class of studies clearly reflects scholars’ enduring interest in the dynamics of public management reform in general, empirical research on the drivers of IMC adoption also responds to the pressing need for researchers to construct more robust counterfactuals in policy evaluation – given the voluntary nature of most IMC projects and the consequent methodological challenge of self-selection bias (see below). The remaining three papers in the special issue advance this body of work into IMC drivers, including by continuing the recent turn from “instrumental” explanations of municipal choices (rooted in local government size and fiscal capacity) towards more political, ideological, and sociological factors.

All six featured papers were selected following the scientific meeting “Frontiers of Local Government Reform (Intermunicipal Cooperation and Remunicipalization”, organized in November 2022 by the Observatory of Analysis and Evaluation of Public Policies of the University of Barcelona. They then underwent the journal’s usual peer-review process. Six democratic and industrialized countries with differing institutional arrangements and administrative traditions are analyzed (Italy, Germany, Portugal, the United States, Norway, and Sweden), using a variety of statistical methods and, in one instance, a multi-case qualitative study. Together, this innovative collection demonstrates something of the empirical and conceptual frontier in the analysis of IMC and local government reform.

In the remainder of this introduction, we describe the origins and nature of IMC reform, review the current evidence base as to its drivers and effects, situate the contribution of the six papers against this background, and suggest productive avenues for future research.

2. Privatize, amalgamate, cooperate: a very short history of local government reform

A broad consensus on the desirability of state intervention in the economy and direct control over the delivery of public services presided over the central decades of the 20th century in much of the industrialized world, both in the political sphere and in scholarship. However, criticism of government intervention grew in the last decades of the century. On the one hand, this was rooted in the public choice view of politicians and bureaucrats as self-interested actors who over-supplied public services or otherwise operated with systemic inefficiency (e.g. Buchanan and Tullock Citation1962; Niskanen, Citation1971). On the other hand, influential empirical studies based on the Chicago School of regulation (e.g. Peltzman Citation1976; Stigler Citation1971) triggered skepticism about the actual results of government intervention, and pressure for policy reform.

The main prescription arising from these critiques was that governments should contract out the state’s activities, including local public services like refuse collection and even welfare services, to private firms. This involved privatizing property rights over the residual profits of the contracted activity (Vickers and Yarrow Citation1991). Early assessments of these reforms suggested that outcomes were broadly positive (e.g. Domberger and Jensen Citation1997; Savas Citation1987). The transfer of ownership and/or introduction of some measure of market competition did seem to be reducing X-inefficiency.Footnote1 But since the beginning of the current century, doubts about the economic effects of privatization have grown (Hodge, Citation2000; Clifton, Comín and Díaz Fuentes, Citation2003). Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the burgeoning empirical evidence indicated that privatization had little or no consistent effect on costs (e.g. Bel, Fageda, and Warner Citation2010; Petersen, Hjelmar, and Vrangbæk Citation2018). And, in line with transaction cost economics, concern grew that aspects of service quality that were hard to define, measure and pre-specify in contracts were neglected or compromised when produced in a market setting, leading to “quality shading” (Brogaard and Petersen Citation2022; Pasha and Williams Citation2022).

Disappointment with the results of privatization did not lead to countries abandoning this approach en masse. But it did direct increased attention towards alternative reform options.Footnote2 Amalgamation of local government units to form larger jurisdictions and/or more multi-purpose delivery organizations had occurred in many local government systems after the second World War, in countries as diverse as Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Brazil, Canada and, sometime later, the United Kingdom. This policy was revived at the turn of the 21st Century (Reingewertz and Serritzlew Citation2019), leading to further consolidations. The aim was to increase the scale at which local services were delivered, and thereby improve economic efficiency and other outcomes. However, amalgamation did not provide the expected (level of) cost savings (Andrews Citation2015; Blom-Hansen et al. Citation2016; Galizzi, Rota, and Sicilia Citation2023), and often produced negative effects on local democracy (Swianiewicz Citation2018; Tavares Citation2018).

Much of the failure of amalgamation policies has been attributed to the multi-purpose and multi-service nature of local government, and the fact that full jurisdictional amalgamation involves the enlargement of all services provided by the local government, irrespective of the cost function and minimum efficient scale for each individual activity. So, while some services gain from merger because hitherto they were produced at sub-optimal scale, others are unaffected or even lose out, because they were already operating at or above minimum efficient scale and/or are now subject to diseconomies of scale (Blom-Hansen et al. Citation2016). One possible way forward, therefore, is to focus on merging only those services for whom up-scaling is efficient, whilst leaving unchanged those that have already reached or exceeded optimal size. This is precisely what inter-municipal cooperation aims to facilitate.

Inter-municipal cooperation (IMC) is an arrangement in which two or more local governments provide one or more public services jointly across their jurisdictions. Although not at all new as a means of local public service delivery, the incidence and range of services subject to IMC have increased significantly over the last two decades. The inter-organizational arrangement can be structured in different ways: informal, formal-contractual, and formal-institutional (Holzer and Fry Citation2011).

Informal cooperation develops through flexible arrangements, oral contracts, and “hand-shake agreements” in which the contracting parties “understand the terms [of the exchange], but they are not codified or legally binding” (Spicer Citation2016, 505). Such informal cooperation is relatively frequent in the United States (Warner Citation2011), but it is much less common in Europe and elsewhere (Bel and Warner Citation2015; Hulst and van Montfort Citation2007). By contrast, formal cooperation can either take the form of contractual agreements between municipalities so that one local government delegates production to another (essentially, a buyer-seller relationship, albeit between two public-sector parties); or it involves the creation of a new, jointly owned organization to deliver the collective responsibilities. The former, which is also known as “inter-local contracting,” is the predominant form of cooperation in the United States (Holzer and Fry Citation2011; Warner and Hebdon Citation2001), and is akin to the “lead authority” model in the United Kingdom (Elston, Rackwitz, and Bel Citationforthcoming). The latter, which scholars sometimes term “institutionalized cooperation,” is the most frequent form of intermunicipal cooperation in Europe (Bel et al. Citation2023). It usually takes the form of administrative organizations or public corporations jointly governed by the cooperating municipalities and made responsible for the delivery of the service(s) in these municipalities. Occasionally, especially in southern European countries, cooperation may also be organized through higher levels of local government (e.g. counties, which sit between municipalities and regional authorities). Service provision is then voluntarily delegated by the constituent municipalities to that higher tier of government.

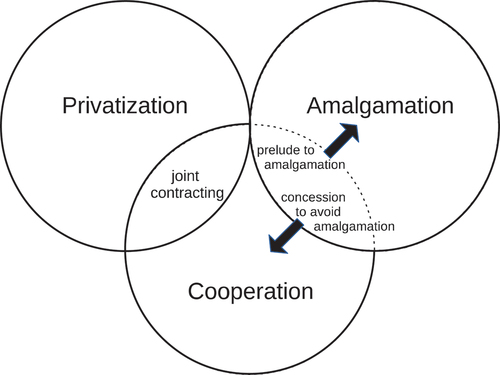

Overall, while it is descriptively convenient to introduce privatization, amalgamation and cooperation as three distinct modes of local government reform, in practice they can overlap, as illustrated in . This is especially the case between privatization and cooperation, since two or more municipalities might agree to work together to arrange the provision of a public service, but then jointly commission all or part of its production to a private operator (Bel and Elston Citationforthcoming). This is labelled “joint contracting” in ,Footnote3 although it can also involve delegated contracting. In delegated contracting, as just described, municipalities transfer the responsibility for providing the service to another tier of local government, which then may or may not decide to privatize all or part of the production. In addition, IMC can also be regarded as a “halfway house” to full amalgamation – adopted either as a prelude to a subsequent merger, or as a means to “stave off” more drastic reform when this is advocated by higher tiers of government but resisted locally (see examples of both in Elston, Rackwitz, and Bel Citationforthcoming). Finally, amalgamation reforms and privatization policies can of course also be used in combination with one another, the UK being a case in point. But since there is no essential synergy between these two approaches, an intersection of their circles in is unwarranted.

3. Unveiling the tapestry of inter-municipal cooperation

IMC is now an integral part of contemporary local governance in many parts of the world, offering a possible solution to the challenges posed by fragmented service delivery, resource constraints, and disjointed governance structures. This special issue examines a variety of aspects of IMC, unraveling the drivers of reform, the diverse outcomes that are generated, and the evolving methodologies finding favor in empirical research.

In early research, IMC was primarily analyzed considering specific service delivery characteristics, with a focus on factors like economies of scale and transaction costs (Brown and Potoski Citation2003; Hefetz and Warner Citation2012). But contemporary perspectives acknowledge the complex nature of IMC and recognize the influence of a broader spectrum of factors. As we discuss more extensively in the next section, local government characteristics, such as size, fiscal health, and political orientation, emerge as determinants shaping a municipality’s inclination towards cooperation (Bel and Warner Citation2015). Moreover, urban areas, with their higher density of potential partners and shared policy challenges, offer more opportunities for collaboration compared to rural regions (Parks and Oakerson, Citation1989). Finally, governance factors, including institutional arrangements, trust, and leadership styles, play a pivotal role in facilitating effective cooperation, fostering communication, and building commitment among participating municipalities (Elston, MacCarthaigh, and Verhoest Citation2018; Ostrom Citation1990).

Early studies particularly tested the notion of cost reduction, and often challenged the supposed guarantee of cost savings. Indeed, efficiencies were shown to be contingent upon various factors, including the municipality’s size, the capital versus labor-intensive nature of the service, and whether the selected governance mechanisms kept transaction costs at a sufficiently low level to justify the inter-organizational collaboration. These early empirical analyses concentrated largely on solid waste collection; almost 60% of the studies included in Bel and Sebő’s (Citation2021) meta-regression dealt solely with solid waste collection (and some multi-service studies in the meta-regression also included waste collection). Fortunately, more recent studies have expanded to other policy sectors, including tax collection, fire services and social services, meaning that richer and more extensive information about IMC and costs is now becoming available.

The scope of IMC outcomes being investigated has also begun to diversify, in particular through tests of the effects of cooperation on service quality, not simply costs. Just as in the neighboring literature on privatization and contracting out (Hodge Citation2000; Petersen, Hjelmar, and Vrangbæk Citation2018; Savas Citation1987), the measurement of service quality has proven to be challenging. As Moore suggested (Citation1997), service outcomes are as important as they are difficult to capture. In studies of IMC, early attempts to examine quality relied on perceptions and subjective measures (Holum and Jakobsen Citation2016); but recent studies have begun to include objective measures based on administrative data (Blåka Citation2017; Blåka, Jacobsen, and Morken Citation2023; Elston, Bel, and Wang Citation2023b, Citation2023b). Still, more comprehensive measurement of service quality, and the testing of trade-offs between different dimensions of quality, and between quality and cost savings, remains a key priority for future IMC research.

The methodological rigor of research In this field has also evolved to yield more robust findings. A notable shift involves transitioning from cross-sectional to panel data analysis. Examining longitudinal data allows researchers to observe trends over time and control for unobserved heterogeneity, providing a more nuanced understanding of how cooperation unfolds and what its longer-term effects are (e.g. Aldag, Warner, and Bel Citation2020). Additionally, quasi-experimental designs, including difference-in-differences, have gained prominence (Breuillé, Duran-Vigneron, and Samson Citation2018; Elston, Bel, and Wang Citation2023b, Citation2023b; Ferraresi, Migali, and Rizzo Citation2018; Luca and Modrego Citation2021; Notsu Citation2024). These approaches use more precise causal identification strategies to attempt to draw more definitive conclusions about the impact on IMC various outcomes. In addition, there is also some effort to study in greater depth the cost function of the services being subjected to IMC, using techniques such as stochastic frontier analysis to determine their minimum efficient scale and, hence, the degree to which municipalities are subject to a “smallness penalty” that might be corrected by joint working across municipal boundaries (Elston, Bel, and Wang Citation2023b; Niaounakis and Blank Citation2017).

Nonetheless, while difference-in-differences has become a standard approach in quasi-experimental designs, its application remains problematic in the context of IMC evaluation. Unlike amalgamations, IMC adoption decisions are typically autonomous choices made by individual municipalities (recent exceptions are policies in France and Italy that conditionally mandate for some categories of local government; see Giacomini et al., Citation2018; Tricaud Citation2023). Municipalities opting to reform may be exposed to different external events, or have different internal capacity or preferences, to those opting to remain autonomous service providers. This lessens the comparability of “treatment” and “control” group. Use of synthetic control measures and other types of matching may help to construct more valid counterfactual groups in future.

4. Advancing research on the drivers of IMC

The literature on IMC already provides many insights into the drivers of cooperation, particularly at the municipal level (Bel and Warner Citation2016). While European studies tend to view cooperation primarily as a cost-driven alternative to traditional service delivery, research from the United States explores additional factors such as spatial location and organizational considerations. Fiscal constraints are a significant predictor of IMC, often measured by debt per capita or fiscal revenues per capita. The predominant trend is that small municipalities and those facing greater fiscal pressures are more likely to engage in cooperative arrangements, likely because they seek to leverage shared resources and mitigate financial constraints (Bel and Warner Citation2015). Nonetheless, research findings are not entirely consistent on this point; and it may also the case that the municipalities most in need of reform (fiscally speaking) may simultaneously be least able to undertake it, lacking the up-front investments required to reform, or proving an unattractive prospect or even a “financial liability” to potential partner municipalities (Dixon and Elston Citation2020).

Moreover, organizational factors play an important role in the use of IMC, particularly in the U.S., with municipalities operating under the council-manager form of government being more likely to engage in cooperation (Nelson and Svara Citation2011). This aligns with the perception that council-manager governance is characterized by more professional management and less political interference, which is conducive to cooperation initiatives aimed at enhancing efficiency and effectiveness. In addition to fiscal and organizational drivers, the literature suggests that spatial factors significantly influence the propensity for intermunicipal cooperation. Geographic proximity is sometimes a key determinant, as municipalities situated in close proximity to one another are more likely to engage in collaborative efforts; although physical proximity is less needed for the sharing of councils’ administrative support services, like payroll, HR, and legal advice, where there is no direct contact with the public and greater potential for “virtual” working (Dixon and Elston Citation2020).

While the literature on drivers of IMC has traditionally paid attention to economic, structural, and geographical characteristics, other important factors such as the role of ideological preferences, citizen support, and legal frameworks have been less scrutinized. Three of the six papers in this special issue address this need for further knowledge on the drivers of IMC and offer novel empirical and theoretical insights.

Bischoff et al. (Citation2024) examine the use of IMCs for business parks in Germany, testing whether fiscal pressure increases the incentive to cooperate with neighboring municipalities. Focusing on the intensity of corporate tax competition between municipalities, the authors hypothesize that citizens and politicians express stronger support for cooperation when the municipality is facing more intense tax competition – first as a means of compensating for lost revenue with more efficient services and lower budget requirements, and second as a means of coordination that might ultimately lessen tax competition. Drawing on two original surveys of citizens and local politicians’ attitudes towards joint business parks, this study finds important discrepancies in local support towards IMC. While the intensity of tax competition and ownership of residential property is associated with citizen support for joint business parks, there is no link between corporate tax competition and local politician support for IMC. Instead, politicians’ support is lower when they stand to lose more power from cooperation. The study offers important insights for research on IMC by highlighting that citizens and politicians have distinct motivations for whether their municipality engages in cooperation with other municipalities.

Casula and Profeti (Citation2024) examine alternative models for delivering early childhood services, an area of local service delivery rarely studied in the IMC literature. Conceptually, the authors provide a novel perspective on how the degree and types of collaboration risks are determined by the institutional conditions for collaboration versus running the service alone, as well as the choice of public or private service delivery model. Drawing on a qualitative study of four cases in Italy, the article illustrates how the regional legal framework, policy trajectories, and the presence of local policy entrepreneurs influence transaction costs and collaboration risks for local actors. An important finding is that a supportive regional framework can reduce transaction costs associated with cooperation, while prior sector experience with collaboration and the presence of strong policy entrepreneurs are important when a clear framework for collaboration is absent. The study introduces new variables to the study of drivers of IMC and by showing how cooperation can co-exist with both public in-house and private outsourced service delivery.

Peixoto et al. (Citation2024) examine the provision, cooperation, and production decisions for bus transportation in Portugal. The article proposes a sequential and interdependent model of decision-making by local officials, which is then tested empirically. The study sheds light on decisions involved in bus transportation provision, offering new insights into the drivers of choices relating to both service delivery (cooperation or not) and the model of production (public, corporation, private, mixed, and so forth). The findings suggest that smaller municipalities and those with low financial autonomy are more likely to cooperate, although the authors note that these two factors may be correlated. In addition, regarding production decisions, the study shows that larger municipalities tend to externalize their services more than smaller ones, this being driven by ideological choices and the municipality’s financial status. The study offers an important general contribution to the field of IMC research by providing a theoretical framework and empirical evidence that links decisions about delivery, cooperation, and production mode in a sequential model of local government decisions.

Together, the three articles on drivers of IMC advance the field in important ways. First, by studying IMC in diverse settings (business parks, early childhood services, and bus transportation services), the studies offer valuable insights into IMC practices in service areas that are rarely studied in the literature. Second, by differentiating between the decision to cooperate and the choice of production mode, the studies by Casula and Profeti (Citation2024) and Peixoto et al. (Citation2024) push the research frontier forward by distinguishing between two crucial yet distinct decisions in local service delivery. Third, by emphasizing the political and ideological dimensions of IMC decisions, Bischoff et al. (Citation2024) and Peixoto et al. (Citation2024) address recent calls for more research beyond economic and structural drivers of local service delivery decisions. These findings highlight the importance of ideological considerations and the role of political calculation in municipal cooperation decisions, which could be included as factors in future research on IMC.

5. Advancing research on the effects of IMC

As noted, much of the early evaluation literature focused on testing IMC’s core proposition that serving the combined jurisdictions of two or more municipalities leads to economies of scale and, so, measurable cost savings. Recently, however, interest has grown in gauging the effect on service quality as well. In part, this development simply better reflects the full value proposition of IMC – which, to its advocates, should improve service quality by allowing volume-enabled specialization of the workforce, better employment prospects to aid staff retention and development, and pooled investments in technology beyond what any individual municipality could achieve on its own. But understanding the effect of IMC on service quality is also essential to ensuring that, where cost savings are reported in the literature, these represent genuine improvements in productivity as a result of re-organization, and are not simply obtained at the expense of service quality.

Blåka and Jacobsen (Citation2024) take forward this important agenda in their contribution to the special issue. Using a 17-year panel of data describing the cost and capacity of the high-risk and labor-intensive child protection services provided by Norwegian municipalities, the authors set out to test the effect of IMC on these parameters and – crucially – the relation between cost and capability. Overall, they find that IMC increases the cost of providing this vital welfare service, but that some of this increase is attributable to increased expenditure on the professional workforce once municipalities are working cooperatively. The remainder of the resource increase, however, is a result of the higher transaction costs involved in operating in networked arrangements.

Sandberg (Citation2024) continues the theme of analyzing the effect of IMC on cost and service quality combined for another labor-intensive public service – education in Sweden. Continuing the trend towards more robust, quasi-experimental methods, Sandberg employs difference-in-differences estimates on a panel dataset stretching between 1998 and 2021, in which quality is measured by educational attainment in formal examinations. The model accounts for the staggered roll-out of IMC across the time period (following Callaway and Sant’anna Citation2021), and uses propensity score matching to assist with the aforementioned self-selection issue. The results show that, for municipalities that adopted cooperation, expenditure on education decreased, but so did student attainment – thus confirming the need to distinguish cost savings from genuine productivity gains.

Finally, Aldag and Warner (Citation2024) return us to the more familiar territory of IMC and costs, though this time in the relatively usual context of a multi-service comparison of 12 different municipal functions in the state of New York in the USA. Using a panel of financial data spanning 1996 to 2016, the authors test whether the degree of agreement formalization – a hitherto under-explored variable in IMC evaluations – between cooperating both municipalities and third parties like non-profits affects performance. Although they find considerable variation across their portfolio of services, in general formalization has no measurable effect on costs.

6. Conclusion – so what’s next?

Inter-municipal cooperation is not a new phenomenon, but it has recently grown to become a significant local government reform strategy, and has attracted new theoretical and empirical attention across several fields of social science (Aldag and Warner Citation2018; Bel and Sebő Citation2021). While studies have traditionally focused on drivers related to financial, structural, and geographical characteristics, there is a need for expanded focus on additional factors such as political motives, ideology, citizen support, legitimacy, and policy learning and diffusion. Moreover, impact evaluations need to look at a range of performance metrics, including but moving beyond service costs, in order to establish when and how IMC improves local public service delivery in the round. The articles in this issue begin to address these gaps by expanding the focus on multiple drivers of cooperation, highlighting the importance of ideology, political calculation, legal frameworks, policy trajectories, and policy entrepreneurs. They also extend the recent turn in the literature towards the analysis of service quality. Together, by applying novel theoretical approaches and methodological designs, the articles advance IMC research by taking into account a range of factors forming local government decisions regarding cooperation and service delivery form.

Despite significant strides in understanding IMC, several areas warrant further exploration to fully unlock its potential and navigate its complexities. Examining how regional dynamics and institutional structures interact with cooperation and its outcomes can lead to a deeper understanding of spatial and governance influences, facilitating the tailoring of reform strategies to specific contexts and fostering cross-regional learning. Additionally, investigating the factors contributing to the long-term viability of IMCs is crucial for ensuring their enduring effectiveness and resilience in the face of changing circumstances (Aldag and Warner Citation2018, Elston, Rackwitz, and Bel Citationforthcoming, Zeemering Citation2018, Zyzak Citation2017). Finally, addressing equity concerns and ensuring that marginalized communities benefit from shared resources are essential considerations. By delving into these aspects, local governance may be able to harness the potential of IMC, fostering a more integrated and effective approach to service delivery and local governance.

Comparison of IMC against the full range of local government reform options, including contracting out, privatization, public-private partnerships, corporatization and traditional in-house provision, is also an important and so-far relatively untrodden path the future research should explore. Again, this should adopt a multidimensional approach to outcomes that evaluates both costs and quality dimensions. Other important assessment parameters include security of supply and opportunities for innovation and knowledge sharing, and should also be compared under alternative service arrangements. Just as with the literature on public versus privatized service delivery (e.g., Bel, Fageda, and Warner Citation2010; Hodge Citation2000; Petersen, Hjelmar, and Vrangbæk Citation2018), there may be important trade-offs among all these outcomes.

Another issue requiring more attention when analyzing IMC outcomes is disentangling the effects of the provider jurisdiction and mode of production. While IMC has a strong association with public production in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian countries, in continental Europe – especially Southern Europe – and other regions of the world, cooperation is often combined with private production. This implies that there can be different combinations of provision and production options (cooperation and public, cooperation and private, individual and public, and individual and private), as shown in Bel and Belerdas-Castro (Citation2023) and Bel and Elston (Citationforthcoming. Future research must shed further light on the combined and separate effects of these different combinations.

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the project PID2022-138866OB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF/EU, and the project 2021 SGR 00261, funded by Generalitat de Catalunya. We appreciate the comments received from the participants in the workshop Frontiers of Local Government Reform (Intermunicipal Cooperation and Remunicipalization), held in Barcelona, November 2022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See Leibenstein (Citation1966) for X-inefficiency.

2. While we focus here on reforms that affect the form in which local services are provided, and -in particular- the provider jurisdiction, it is worth mentioning other reforms have gained interest in the recent decades, affecting the form in which the services are delivered, within the public-private duality. On the one hand, corporatization has involved the creation of organizations external to the administration but still under government control, so that service delivery can be publicly managed with greater autonomy (van Genugten et al. Citation2023). On the other hand, re-municipalization has involved bringing back under government control the delivery of services that had previously been privatized (Clifton et al. Citation2021). A recent special issue has been recently dedicated in this journal to the latter (Re-municipalization of public services: Trend or hype’, volume 24, issue 3, 2021).

3. By “joint contracting” we mean two or more municipalities contracting with one or more private operators.

References

- Agranoff, R., and M. McGuire. 2003. Collaborative Public Management. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Aldag, A. M., and M. E. Warner. 2018. “Cooperation, Not Cost Savings: Explaining Duration of Shared Service Agreements.” Local Government Studies 44 (3): 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1411810.

- Aldag, A. M., and M. E. Warner. 2024. “Intermunicipal Cooperation and Agreement Formalization.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2023.2244628.

- Aldag, A. M., M. E. Warner, and G. Bel. 2020. “It Depends on What You Share: The Elusive Cost Savings from Service Sharing.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (2): 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz023.

- Andrews, R. 2015. “Vertical Consolidation and Financial Sustainability: Evidence from English Local Government.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (6): 1518–1545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614179.

- Arntsen, B., D. O. Torjesen, and T.-I. Karlsen. 2018. “Drivers and Barriers of Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Health Services – the Norwegian Case.” Local Government Studies 44 (3): 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1427071.

- Banaszewska, M., I. Bischoff, E. Bode, and A. Chodakowska. 2022. “Does Inter-Municipal Cooperation Help Improve Local Economic Performance? – Evidence from Poland.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 92:103748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2021.103748.

- Bel, G., and A. Belerdas-Castro. 2022. “Provision and Production Reform of Urban Fire Services: Privatization, Cooperation and Costs.” Public Management Review 24 (9): 1331–1354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1886317.

- Bel, G., I. Bischoff, S. Blåka, M. Casulla, J. Lysek, P. Swianiewicz, A. Tavares, and B. Voorn. 2023. “Styles of Inter-Municipal Cooperation and the Multiple Principal Problem: A Comparative Analysis of European Economic Area Countries.” Local Government Studies 49 (2): 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2041416.

- Bel, G., and T. Elston. 2023. “When the Time Is Right: Testing for Dynamic Effects in Collaborative Performance.” Public Management Review Forthcoming. 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2214784.

- Bel, G., and T. Elston. Forthcoming. “Disentangling the Separate and Combined Effects of Privatization and Cooperation on Local Government Service Delivery.” Public Administration. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12992.

- Bel, G., X. Fageda, and M. Warner. 2010. “Is Private Production of Public Services Cheaper Than Public Production? A Meta-Regression Analysis of Solid Waste and Water Services.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29 (3): 553–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20509.

- Bel, G., and M. Sebő. 2021. “Does Inter-Municipal Cooperation Really Reduce Delivery Costs? An Empirical Evaluation of the Rule of Scale Economies, Transaction Costs, and Governance Arrangements.” Urban Affairs Review 57 (1): 153–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419839492.

- Bel, G., and M. E. Warner. 2015. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation and Costs: Expectations and Evidence.” Public Administration 93 (1): 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12104.

- Bel, G., and M. E. Warner. 2016. “Factors Explaining Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Service Delivery: A Meta-Regression Analysis.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 19 (2): 91–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2015.1100084.

- Bischoff, I., C. Bergholz, P. Haug, and S. Melch. 2024. “Does Intense Tax Competition Boost Public Acceptance for IMC? Evidence from a Survey Among German Citizens and Local Politicians.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform. This issue. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2024.2333306.

- Blaeschke, F., and P. Haug. 2018. “Does Intermunicipal Cooperation Increase Efficiency? A Conditional Metafrontier Approach for the Hessian Wastewater Sector.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1395741.

- Blåka, S. 2017. “Service Quality, Inter-Municipal Cooperation and the Optimum Scale of Operation.” In The Rise of Common Political Order, edited by J. Trondal, 233–250. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Blåka, S., and D. I. Jacobsen. 2024. “Does Shared Service Delivery Affect Cost? A Study of the Cost-Capacity Relation in Norwegian Local Child Protection Services.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2023.2281645.

- Blåka, S., D. I. Jacobsen, and T. Morken. 2023. “Service Quality and the Optimum Number of Members in Intermunicipal Cooperation: The Case of Emergency Primary Care Services in Norway.” Public Administration 101 (2): 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12785.

- Blom-Hansen, J., K. Houlberg, S. Serritzlew, and D. Treisman. 2016. “Jurisdiction Size and Local Government Policy Expenditure: Assessing the Effect of Municipal Amalgamation.” American Political Science Review 110 (4): 812–831. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000320.

- Breuillé, M.-L., P. Duran-Vigneron, and A.-L. Samson. 2018. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation and Local Taxation.” Journal of Urban Economics 107:47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.08.001.

- Brogaard, L., and O. H. Petersen. 2022. “Privatization of Public Services: A Systematic Review of Quality Differences Between Public and Private Daycare Providers.” International Journal of Public Administration 45 (10): 794–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2021.1909619.

- Brown, T. L., and M. Potoski. 2003. “Transaction Costs and Institutional Explanations for Government Service Production Decisions.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 13 (4): 441–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mug030.

- Buchanan, J. M., and G. Tullock. 1962. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations for Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor (MI): The University of Michigan Press.

- Callaway, B., and P. H. C. Sant’anna. 2021. “Difference-In-Differences with Multiple Time Periods.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 200–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.

- Casula, M., and S. Profeti. 2024. “Not a Black or White Issue: Choosing Alternative Organizational Models for Delivering Early Childhood Services.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform This issue. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2023.2249185.

- Clifton, J., F. Comín, and D. Díaz Fuentes. 2003. Privatisation in the European Union. Public Enterprises and Integration. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Clifton, J., M. E. Warner, R. Gradus, and G. Bel. 2021. “Re-Municipalization of Public Services: Trend or Hype?” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2019.1691344.

- Dixon, R., and T. Elston. 2020. “Efficiency and Legitimacy in Collaborative Public Management: Mapping Inter-Local Agreements in England Using Social Network Analysis.” Public Administration 98 (3): 746–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12649.

- Domberger, S., and P. Jensen. 1997. “Contracting Out by the Public Sector: Theory, Evidence, Prospects.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 13 (4): 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/13.4.67.

- Elston, T., G. Bel, and H. Wang. 2023a. “The Effect of Inter-Municipal Cooperation on Social Assistance Programs: Evidence from Housing Allowances in England.” Rebuilding Macroeconomics Working Paper. London.

- Elston, T., G. Bel, and H. Wang. 2023b. “If it ain’t Broke, don’t Fix It: When Collaborative Public Management Becomes Collaborative Excess.” Public Administration Review 83 (6): 1737–1760. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13708.

- Elston, T., M. MacCarthaigh, and K. Verhoest. 2018. “Collaborative Cost-Cutting: Productive Efficiency as an Interdependency Between Public Organizations.” Public Management Review 20 (12): 1815–1835. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1438498.

- Elston, T., M. Rackwitz, and G. Bel. Forthcoming. “Going Separate Ways: Ex-Post Interdependence and the Dissolution of Collaborative Relations.” International Public Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2023.2271468.

- Ferraresi, M., G. Migali, and L. Rizzo. 2018. “Does Intermunicipal Cooperation Promote Efficiency Gains? Evidence from Italian Municipal Unions.” Journal of Regional Science 58 (5): 1017–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12388.

- Galizzi, G., S. Rota, and M. Sicilia. 2023. “Local Government Amalgamations: State of the Art and New Ways Forward.” Public Management Review 25 (12): 2428–2450. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2177327.

- Giacomini, D., A., Sancino, and A. Simonetto. 2018. “The Introduction of Mandatory Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Small Municipalities: Preliminary Lessons from Italy.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 31 (3): 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-03-2017-0071.

- Hefetz, A., and M. E. Warner. 2012. “Contracting or Public Delivery? The Importance of Service, Market and Management Characteristics.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (2): 289–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur006.

- Hodge, G. 2000. Privatization: An International Review of Performance. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Holum, M. L., and T. G. Jakobsen. 2016. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation and Satisfaction with Services: Evidence from the Norwegian Citizen Study.” International Journal of Public Administration 39 (8): 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.1029132.

- Holzer, M., and J. Fry. 2011. Shared Services and Municipal Consolidation: A Critical Analysis. Alexandria, VA: Public Technology Institute.

- Hulst, J. R., and A. van Montfort, eds. 2007. Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Kettl, D. F. 2006. “Managing Boundaries in American Administration: The Collaboration Imperative.” Public Administration Review 66 (S1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00662.x.

- Leibenstein, H. 1966. “Allocative Efficiency Vs. X-Efficiency.” American Economic Review 56 (3): 392–415.

- Luca, D., and F. Modrego. 2021. “Stronger Together? Assessing the Causal Effect of Inter‐Municipal Cooperation on the Efficiency of Small Italian Municipalities.” Journal of Regional Science 61 (1): 261–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12509.

- Moore, M. H. 1997. Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nelson, K. L., and J. H. Svara. 2011. “Form of Government Still Matters: Fostering Innovation in US Municipal Governments.” The American Review of Public Administration 42 (3): 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074011399898.

- Niaounakis, T., and J. Blank. 2017. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation, Economies of Scale and Cost Efficiency: An Application of Stochastic Frontier Analysis to Dutch Municipal Tax Departments.” Local Government Studies 43 (4): 533–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1322958.

- Niskanen, W. A. 1971. Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Livingston, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Notsu, N. 2024. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation Cloud and Tax Administrative Costs.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 105:103991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2024.103991.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Parks, R. B., and R. J. Oakerson. 1989. “Metropolitan Organization and Governance: A Local Public Economy Approach.” Urban Affairs Quarterly 25 (1): 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/004208168902500103.

- Pasha, O., and T. Williams. 2022. “Cost Saving or Quality Shading? Exploring the Impact of Contracting Out on Organizational Outcomes.” Academy of Management Proceedings 2022 (1): 14890. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2022.14890abstract.

- Peixoto, A., P. J. Camões, and A. F. Tavares. 2024. “Local Delivery of Bus Transportation Services: A Model of Interdependency of Provision and Production Choices.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform This issue. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2024.2330438.

- Peltzman, S. 1976. “Toward a More General Theory of Regulation.” Journal of Law and Economics 19 (2): 211 240. https://doi.org/10.1086/466865.

- Petersen, O. H., U. Hjelmar, and K. Vrangbæk. 2018. “Is Contracting Out of Public Services Still the Great Panacea? A Systematic Review of Studies on Economic and Quality Effects from 2000 to 2014.” Social Policy & Administration 52 (1): 130–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12297.

- Reingewertz, Y., and S. Serritzlew. 2019. “Special Issue on Municipal Amalgamations: Guest Editors’ Introduction.” Local Government Studies 45 (5): 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2019.1615465.

- Sandberg, K. 2024. “The More the Merrier? Examining the Effects of Inter-Municipal Cooperation on Costs and Service Quality in Upper Secondary Education.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2024.2326410.

- Savas, E. S. 1987. Privatization: The Key to Better Government. Chatham, NJ: Chatham House Publishers.

- Spicer, Z. 2016. “Governance by Handshake? Assessing Informal Municipal Service Sharing Relationships.” Canadian Public Policy 42 (4): 505–513. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2015-079.

- Stigler, G. 1971. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2 (1): 121. https://doi.org/10.2307/3003160.

- Swianiewicz, P. 2018. “If Territorial Fragmentation is a Problem, is Amalgamation a Solution? – Ten Years Later.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1403903.

- Tavares, A. F. 2018. “Municipal Amalgamations and Their Effects: A Literature Review.” Miscellanea Geographica 22 (1): 5–15. https://doi.org/10.2478/mgrsd-2018-0005.

- Teles, F., and P. Swianiewicz, eds. 2018. Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe: Institutions and Governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tricaud, C. 2023. “Better Alone? Evidence on the Costs of Intermunicipal Cooperation.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15999.

- van Genugten, M., B. Voorn, R. Andrews, and H. Torsteinsen. 2023. Corporatization of Local Government: Context, Experiences and Perspectives from 19 Countries, edited by U. Papenfuss. Palgrave: Houndmills.

- Vickers, J., and G. Yarrow. 1991. “Economic Perspectives on Privatization.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5 (2): 111132. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.2.111.

- Warner, M. E. 2011. “Competition or Cooperation in Urban Service Delivery?” Annals of Public & Cooperative Economics 82 (4): 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.2011.00450.x.

- Warner, M. E., and R. Hebdon. 2001. “Local Government Restructuring: Privatization and Its Alternatives.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (2): 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.2027.

- Zeemering, E. 2018. “Why Terminate? Exploring the End of Interlocal Contracts for Police Service in California Cities.” The American Review of Public Administration 48 (6): 596–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074017701224.

- Zyzak, B. 2017. “Breakdown of Inter-Organizational Cooperation: The Case of Regional Councils in Norway.” In The Rise of Common Political Order: Institutions, Public Administration and Transnational Space, edited by J. Trondal, 251–270. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.