ABSTRACT

Given that teaching is a complex task and that teacher education programmes (TEPs) are usually short, it can be difficult to examine the learning process of pre-service teachers. Based on an analysis of previous studies and empirical research, this study examines the learning process of trainee language teachers during a TEP at a Finnish university. Narrative-like visual and written data were collected from the trainee teachers at the onset (N = 51) and end (N = 43) of the one-year TEP. These multimodal data were qualitatively analysed using transformative learning as the theoretical framework. The results of the study revealed that the trainee teachers encountered several disorienting dilemmas at the start of the programme, mostly related to self-esteem as a teacher, classroom work, and subject-matter knowledge. The change during the TEP was seen especially in the increase of self-confidence and in the motivation to work with learners. Additionally, the findings showed that trainees needed more support from their mentoring teachers, especially in terms of working more creatively in the classroom. Moreover, our study provides a method for how pre-service teachers’ learning processes can be captured and reflected during the TEP.

1. Introduction

An ideal foreign language (FL) teacher should be creative, flexible, and enthusiastic about his or her target language and culture (Borg Citation2006a). Through this engagement, FL teachers can inspire students to explore languages and cultures inside and outside the classroom. During TEP, pre-service teachers develop conceptions of themselves as FL teachers, which might be idealistic. The underlying reason could be that ‘TEPs are unable to reproduce environments like those teachers face when they graduate’ (Farrell Citation2009, 182). Based on our experiences with the education of language teachers, trainee FL teachers in Finland have positive experiences of their language teachers at school, and for some of the trainees, these teachers were the reason why they opted for the teaching profession. When entering the TEP, trainees may be unrealistic in their optimism (Pajares Citation1992). In most cases, TEP offers a relatively short time for teachers’ development (Virta Citation2002). Therefore, it can be difficult for instructors to observe and change such unrealistic expectations. Many studies, for instance, Pajares (Citation1992; Kagan Citation1992), opined that the beliefs of pre-service teachers are resistant to change. This makes the examination of prior beliefs necessary (Melo-Pfeifer and Chik Citation2020) considering their strong influence and ‘the relatively weak impact of language teacher education programs on the action of novice teachers’ (Farrell Citation2009, 183). Given that teaching is a complex task, learning it during TEP can be very difficult. One motivation for this study is the observation that teacher education should provide knowledge about the uncertainties associated with teaching and offer tools for reflection and discussion. There are studies available on the effects of language teacher education on pre-service teachers (Borg Citation2006b), however, most of these studies focus on pre-service teachers of English. Therefore, we focused on pre-service teachers of languages other than English.

Based on narrative-like multimodal postcards addressed to future selves, this study elucidates the learning process of pre-service teachers during a one-year TEP at a Finnish university. Based on previous studies on language teacher education, the transformation during the learning process and changes in beliefs are analysed using transformative learning theory (Mezirow Citation1978) as a theoretical framework. In Section 2, previous studies regarding transformative learning through writing and the development of trainee language teachers during teacher education are discussed, especially studies in which multimodal data were used. In Section 3, studies involving the impact of teacher education on language teachers’ learning process are discussed. Subsequently, the data comprising multimodal postcards produced by trainees at the beginning and end of the TEP were analysed using transformative learning as a theoretical framework. Finally, the results of the study are discussed and their implications for FL teacher education are outlined.

2. Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework used in this study is based on the transformative (adult) learning theory that was first introduced by Mezirow (Citation1978, Citation1991) and, among others, advanced by Taylor (Citation2007) and Illeris (Citation2014a). When referring to transformation, Mezirow (Citation1978, Citation1991) primarily meant adult learners’ adoption of a new frame of reference, ‘a perspective on a certain disorienting event’ that transformed something in their life. Mezirow (Citation2006, Citation2009) later complemented his theory by including emotions and social relationships in transformative processes. Taylor (Citation2009) stated that it is important to process feelings when fostering transformative learning because doing so increases the power of critical reflection. For instance, for teacher educators willing to foster transformative learning, this would require an active dialogue with their students about their feelings.

The theory of transformative learning was initially used mainly to analyse holistic adult learning processes (Cranton Citation2009). Subsequently, the theory has been adapted into different contexts, for instance, in the context of teacher education (Weinberg et al. Citation2020) and language teacher education (Arshavskaya Citation2017). As an example, Arshavskaya (Citation2017) conducted case studies of two prospective language teachers who maintained blogs over the course of one academic semester (15 weeks). Her results revealed that the teachers’ focused on themselves as a teacher. Moreover, the findings indicate that teachers’ writing practices can contribute to their development as teachers and serve as an important tool in investigations of the development of pre-service teachers. Recently, McConn and Geetter (Citation2020) found disorienting dilemmas within two English teacher candidates’ beliefs, lesson plans, videos of teaching, and their responses to interview questions. Above all, the candidates felt anxious in front of the students and frustrated because of their preconceptions about teaching.

In general, at all stages of their careers, teachers benefit from writing as a reflective practice. Several studies have demonstrated that reflective writing is beneficial when language teachers are learning how to teach (Burton Citation2009; Johnson and Golombek Citation2011) and to observe their transformative learning process (Arshavskaya Citation2017). Reflective writing mostly manifests as the writing of learning diaries and journals. This method has been used in studies that have explored the learning processes of both language teachers (Farrell Citation2009; Huang Citation2006) and learners (Huang Citation2005). The written format usually intensifies the reflective experience because it challenges learners ‘to both recall from memory and verbally articulate reflective moments during their teaching practice, particularly about a phenomenon (teaching) that often operates at a tacit level’ (Taylor Citation2009, 9).

Multimodal linguistics biographies, including drawings, have been used to investigate, for instance, language teacher candidates’ linguistic knowledge (Coffey Citation2015), their future professions (Brandão and Ana Citation2019; Ruohotie-Lyhty and Pitkänen-Huhta Citation2020), beliefs about languages and multilingual language learning (Melo-Pfeifer and Chik Citation2020), and autobiographical reflections of in-service language teachers (Choi Citation2013). In a study not related to language teacher education, Meijer, De Graaf, and Meirink (Citation2011) used a line-drawing technique that focused on the key experiences of trainee teachers teaching different subjects during the complex and emotionally challenging first year of teaching in the Netherlands. Their results indicated that the first year of teaching was filled with highs and lows for the teachers. Especially the lows were needed for development. In the Finnish context, Kalaja et al. (Citation2013) experimented with visual narratives to follow the development of university language students into qualified English teachers. They asked the students to draw portrait of themselves as learners of English. By analysing the portraits, they aimed to identify the drawings that revealed the students’ beliefs about learning English. Most of the trainee English teachers drew themselves alone, as if no students or other people participated in their English lessons. Contrasting futures as a teacher – that is, the best and worst case scenarios – were detected in visualisations of 61 pre-service language teachers, in a recent study from Finland by Ruohotie-Lyhty and Pitkänen-Huhta (Citation2020).

In summary, there is emerging interest in using visual material besides written narratives in investigating language teacher education (Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer Citation2019; Kalaja and Pitkänen-Huhta Citation2018), for instance, to foster reflexivity on teachers’ own language learning history (Coffey Citation2015). This study aims to show how multimodal postcards including writings and drawings can be used to capture the change in beliefs during the TEP in a way that trainees themselves (and not only researchers) can profit from the research approach by getting the chance to reflect on their change (cf. Mezirow Citation2000).

3. Literature review

Studies on the learning process of pre-service language teachers have yielded contradictory results regarding the impact of teacher education. A set of studies has revealed positive changes, yet another has reported a lack of any personal development as a result of teacher education. Positive results were obtained, for instance, by Cabaroglu and Roberts (Citation2000), who explored 25 trainee language teachers during a 36-week course in FL teaching to capture the changes in their pre-existing beliefs on learning and teaching. Most of the trainee teachers exhibited some changes, and a few exhibited radical changes. By contrast, Kagan (Citation1992), who reviewed studies on the professional growth of pre-service and novice teachers, concluded that pre-service teachers’ personal beliefs and images usually remained inflexible during the TEP. She noticed that during this developmental stage, three primary tasks were accomplished: (i) trainees acquired knowledge of pupils, (ii) they learned to modify and reconstruct their self-image as a teacher, and (iii) they were able to integrate classroom management and instruction. Similar results were obtained by Numrich (Citation1996), who analysed diaries maintained by 26 novice English teachers during a practicum. Her findings showed that novice teachers focused mostly on students’ reactions rather than on themselves. They felt challenged when managing class time, providing clear directions, responding to various students’ needs, teaching grammar effectively, and assessing students’ learning.

Prior language learning experiences at school can hinder the development process of teachers in training. This could be observed, for instance, in Johnson’s (Citation1994) multiple-source (written journals, observations) study of four pre-service English teachers. The trainees described their own beliefs about language teachers and teaching during their 15-week practicum. Johnson found that these beliefs originated from the trainees’ formal language learning experiences; for example negative images of teachers who simply followed the book. In addition, all pre-service teachers in her study were critical of their own teacher-directed instructional practices, but they felt powerless regarding effecting any change because alternative teaching models were not offered to them during the practicum. Furthermore, Johnson observed that pre-service teachers’ images of themselves as teachers and of teaching were in sharp contrast to the classroom realities they faced during the practicum. A more recent study by Yuan and Lee (Citation2014), based on semi-structures interviews, examined the process of belief change among three Chinese English teacher candidates during the teaching practicum. Despite the short duration of the practicum, the candidates’ beliefs about language teaching and about themselves as teachers were transformed and developed. Their research revealed ‘a more complex process in which the original beliefs are not simply rejected and replaced by the opposite ones but are modified and refined through field learning activities’ (Yuan and Lee Citation2014, 9).

In previous comparative studies involving novice and expert language teachers, differences and similarities were observed between both sets of teachers. One similarity shared by both groups was the feeling of uncertainty. This was reported by Tsui (Citation2003), who compared the expertise of two novice and two experienced ESL teachers. To handle this uncertainty, the novice teachers prepared more detailed lesson plans than their experienced colleagues. According to Tsui, novice teachers often went through a ‘survival phase’, and in this phase, they were found to be preoccupied with their own survival in the classroom. Through positive experiences, they reached the ‘stabilization phase’. In this phase, their focus changed from the self to students. They became more flexible in classroom management and could manage unpredictable situations better (Tsui Citation2003, 79–80). Negative experiences were often related to feelings of uncertainty. In the Canadian context, Gatbonton (Citation2008) explored the teaching-related thought processes of novice English teachers and compared her findings with those of her previous study, which focused on experienced ESL teachers. The comparison indicated that both novice and experienced L2 teachers were attentive to students’ behaviours in the classroom. One observed difference was that novice teachers focused more on students’ negative reactions than on their positive reactions. This can be ascribed to the feeling of uncertainty that novice teachers usually have about themselves in the classroom.

Thus, based on the abovementioned studies on changes in beliefs during language teacher education, uncertainties and difficulties seem to be the ‘trigger point’ in the learning process of becoming language teachers. As the theory of transformative learning builds on disorienting dilemmas that learners experience at the beginning of their learning process and are the starting point of the transformative learning process (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991), we focus on the change in beliefs (Tillema Citation1998) during the one-year teacher education programme to capture the transformation of the learning process of the pre-service language teachers.

4. Purpose of the study

In this study, we examine pre-service teachers’ beliefs about themselves as FL teachers, and at the onset documented in multimodal ‘postcards’ (Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer Citation2019), and at the end of the one-year TEP documented responses to these. The aim is mainly to reveal the change in their beliefs and transformation of the learning process during the one-year teacher education programme. The specific research questions are as follows:

How did pre-service teachers see themselves as FL teachers at the beginning of the one-year TEP?

How did pre-service language teachers’ beliefs change during the programme?

5. Method

5.1. Study context

The research-based teacher education offered in Finland, which includes practical training in teacher training schools, is often seen as the reason why Finland has succeeded in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (Sahlberg Citation2010). Moreover, the crucial role of teacher-training schools and the use of mentoring teachers in Finnish teacher education are factors that must be considered when investigating the development of Finnish trainee teachers. Although Finnish teacher-training schools are generally regarded as unique in the European context, they do not differ considerably from mainstream schools in Finland (Pollari, Salo, and Koski Citation2018). Hence, the teacher-training schools provide ‘real-life surroundings’ for trainees. The environments in these schools correspond to the ones that teachers may face when they graduate. This eventually reduces the ‘reality shock’ (Veenman Citation1984; cited in Farrell Citation2009) that novice teachers often experience after teacher education.

Students from various academic backgrounds enrol in the TEP in Finland. In most cases, they apply to the one-year TEP at the Department of Teacher Education after receiving their bachelor's degree in their major subject from the corresponding university departments. In the Finnish context, subject teacher education is imparted through different departments. Subject-matter knowledge (Andrews Citation2003) is acquired from the respective university departments, and pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman Citation1987) during the one-year TEP that occurs both at the Department of Teacher Education and the Teacher Training School associated with the Faculty of Education. As a result, they apply the academic knowledge acquired in university courses and the pedagogical content knowledge of classroom settings acquired during the TEP. In the Teacher Training School, pre-service teachers learn practical skills and the underlying pedagogical backgrounds by working in a real classroom supervised by experienced mentoring teachers, who, in the sense of Mezirow (Citation1978, Citation1991), can be regarded as persons playing an important role during the trainees’ learning process. In the context of this study, the number of classes taught by the trainees at the Teacher Training School during the TEP varied from 15–30. In less taught languages, such as Spanish, Italian, and Russian, the number was usually smaller than in more frequently taught languages, such as Swedish, German, or French. After lessons, trainees usually receive feedback from their mentoring teachers and, from their peers. This study is based on part of pedagogical studies at the Department of Teacher Education. The course objectives were closely aligned, among others, with the following domains: teacher's professional ethics, professional development and dimensions of the teaching profession, multiliteracy, and language awareness.

5.2. Data collection and participants

As is often the case in studies on teachers’ cognition (cf. Borg Citation2006b, 168), reflective writing and drawing (cf. Barkhuizen, Benson, and Chik Citation2014, Ch. 3) were selected as the data collection methods in this study. The multimodal data (Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer Citation2019) were gathered through the course activities during a one-year TEP at a Finnish university. Two types of data were collected: (1) multimodal’postcards’ that were drawn and handwritten after the first ABC weeks in the TEP, and (2) responses to these postcards that were written at the end of the TEP. The postcard drawing and writing activity aimed to integrate reflective practices into the TEP. We believe this would encourage pre-service FL teachers to become aware of and critically examine their beliefs, expectations, and practices (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991; Borg Citation2011). One reason for combining visual and written data was because these data can reveal different aspects (Kalaja et al. Citation2013), both as an arts-based research practice (Leavy Citation2009) and as visual storytelling including visual images and accompanying texts (Coffey Citation2015). Drawings can also reveal turning points and moments of crisis (Tasker Citation2018).

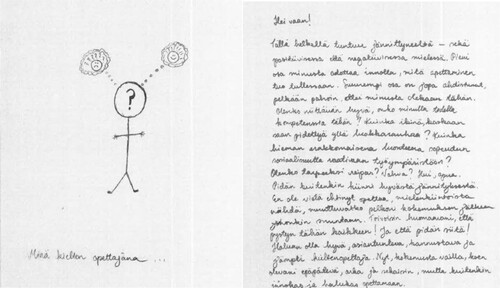

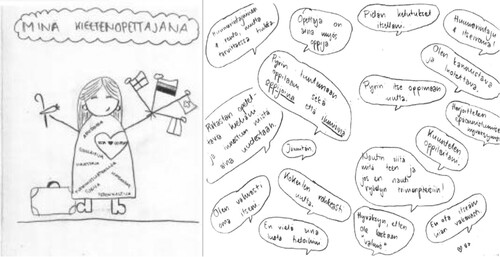

Because it is important for teacher educators to focus on the emotional needs of trainees (Meijer, de Graaf, and Meirink Citation2011; Taylor Citation2009), especially at the start of the course, the trainees were asked to produce postcards after their ABC first weeks in the TEP. By that time, trainees had completed some theoretical studies in the Department of Teacher Education and observed lessons at the Teacher Training School. The postcard task was given as follows: ‘Draw a picture of yourself and describe yourself as a foreign language teacher as you are now [September/October]. Address “post card” to yourself. It will be handed to you when you have finished teacher training’[April/May]. Trainees were given blank sheets of paper and materials for colouring to accomplish the task. They decided for themselves how they combined the components, such as drawings with texts, symbols or words. As the task was entitled ‘Me as a language teacher’ (fi. Minä kieltenopettajana) by the teacher educator, most students headed their postcards in the same way ().

As the data collection was done in the middle of a busy teaching period, approximately one teaching hour was assigned to the trainees for postcard writing and drawing during the course (Coffey Citation2015). After writing the postcards, trainees had a chance to reflect on them with their peers. Thereafter, the teacher educator collected the postcards (1–4 pages) and kept them until the trainees wrote responses (1–2 pages) to the postcards at the end of the TEP. In most cases, when the trainees wrote responses to their own postcards, they had almost completed their pedagogical studies (35 ECTS) and taught 15–30 classes in their major and, in most cases, some classes in their minor at the Teacher Training School.

As summarised in , the data were collected during two consecutive TEPs. At the beginning of TEPs, a total of 51 teacher trainees recorded their reflections in writing and drawing. At the end of TEPs, 43 trainees responded to their reflections, mostly in writing. Fewer responses were obtained at the end of the TEPs because a few of the trainees did not attend the class in which the responses were written. In this study's target university, the number of FL teacher trainees accepted per year varies between 50–70. This means that approximately half of the trainees enrolled in the academic year participated in the study. All majored participants presented languages other than English (). To guarantee participant anonymity (N = 51, St. 1–51, hereinafter), a few languages were grouped together. Because it was possible to identify the male students, student gender was omitted when quoting student responses.

Table 1. Data Collection and Participants.

5.3. Data analysis

As outlined in Section 2, the concept of transformative learning (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991; Taylor Citation2009) was used as the theoretical framework in our analysis. We aimed to determine how language teacher education changed or transformed trainees’ beliefs (Tillema Citation1998; Borg Citation2006b, Citation2011; Yuan and Lee Citation2014). With a self-examination of emotions and individual experiences, we referred to the trainees’ individual experiences that were relevant for transformation (cf. Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991; Taylor Citation2009) or development during the TEP. Data were collected in two different places and at different times, which led to ‘transformed conceptualizations’ of trainees as teachers and eventually, after the TEP, to ‘transformed modes of engagement in the activities of teaching’ (Johnson and Golombek Citation2011, 490). The following concepts from the theory of transformative learning were used to analyse the data:

Disorienting dilemma

In the context of this study, a disorienting dilemma refers to a significant personal event or a critical turning point from the trainee's perspective during the teacher education. Moreover, it can refer to something that a trainee is willing to change during the practicum (cf. Taylor Citation2000).

(ii) Critical reflection, dialogue, and rebuilding lives

Trainees were invited to engage in dialogue with themselves. As Mezirow (Citation1998, 185) stated, reflection can be a ‘turning back’ on experience and ‘one can reflect on oneself reflecting’. When trainees opened the postcards at the end of the TEP, they had a chance to reflect on their thoughts at the onset of the programme and their experiences throughout the programme. The goal of the postcard to future self was to capture the development or transition of trainees towards new perspectives (Mezirow Citation2000), that is, in our context, change in beliefs. Moreover, the aim was through arts-based research approach to get trainees to ‘express or get at some aspect of their lives that would otherwise remain untapped’ (Leavy Citation2009, 218).

In this study, data analysis was performed using qualitative methods, especially content analysis (Miles and Michael Huberman Citation1994), which can be not only qualitative but also quantitative (Huang Citation2005). The teacher educator/researcher read all the data multiple times and noted the most salient topics that emerged from the visual and written data. The data were interpreted and categorised using the theory of transformative learning as the theoretical framework. The grounded theory approach was used to avoid predetermination of the results (Strauss and Corbin Citation2008). The motives depicted in the drawings produced by the trainees were described and categorised. Qualitative analysis of the postcards and answers was conducted in the original language of the respondents (Finnish). In Section 6, the selected quotations from the data in the Finnish language were translated to English by the author.

5.3. Limitations

Using multiple sources, we attempted to avoid the weaknesses of a single data collection method (cf. Bailey Citation2006, Ch. 6) and thus increase the reliability and validity of the research (cf. Burns Citation1999, Ch. 2). One limitation of this study is its subjective nature – the author played a double role as a researcher and teacher educator, and the respondents were well known to the researcher. Another limitation could be the short length of the Finnish subject TEP [from September to May] from the viewpoint of observing trainees’ development (Virta Citation2002). In addition, during the data collection, information on the exact number of classes taught by pre-service teachers was not gathered. Despite the limited number of participants, the multimodal data including arts-based writings were extensive and detailed (Leavy Citation2009, 28). However, we do not intend to ‘make claims about generalising the findings of the research to large populations’ (Burns Citation1999, 23). Moreover, we acknowledge that our research focused on a limited geographical area of Finland, which is important to mention because the content and organisation of Finnish subject TEPs vary from one university to another.

6. Findings

The results of this study are presented in consideration of our two main research questions. To support the research findings, examples of drawings and quotations from trainees’ writings are included.

6.1. Self-portraits and disorienting dilemmas at the onset of the TEP

In the postcard drawings, we observed how the trainee FL teachers saw themselves at the beginning of the TEP. Both images of ideal language teachers and disorienting dilemmas could be observed. Trainees mostly drew themselves as the ideal teachers they wanted to become. The subjects depicted in the drawings represented in the postcards are summarised in .

Table 2. Trainees’ (N = 51) visual representations in the postcards.

As summarised in , the most represented figurations were trainees themselves with positive symbols (hearts, smileys) (Figure 2). Six trainees represented themselves in a negative context (Figures 1 and 3). The negative artefacts presented in postcards were, for instance, turbulences, question marks and a wooden pointer, which is usually associated with ‘old school’ teachers in Finland. The positive and negative artefacts in the visualisations pointed at contrasting future scenarios as a teacher ( and ; similarly Ruohotie-Lyhty and Pitkänen-Huhta Citation2020). Six of the 51 participants drew themselves standing alone (cf. Kalaja et al. Citation2013). Five trainees draw themselves with their future students. Compared to the trainees themselves, their students were drawn as small figures. Interestingly, the subjects presented in the drawings on the postcards were positive in many cases compared to the written texts, which hinted at uncertainty. The positive reactions or greetings in the self-portraits were often expressed in the target language (Bene! Bra jobbat! Guten Tag! Bonjour! etc.) in speech bubbles. The decorative artefacts were books or elements from the classroom (smart board etc.) or artefacts related to the target culture (flags, Russian dolls, etc.) that referred to commonly shared culturally bound representations (Coffey Citation2015; Melo-Pfeifer and Chik Citation2020). Eight trainees drew images with no connection to language teaching, e.g. flowers, dogs, bunnies, the sun, and butterflies.

In accompanying written texts to the visual representations in the postcards, the trainees often described the type of language teacher that they would like to become and described their feelings (Taylor Citation2009) at the onset of the TEP. In the analysis of the written texts, we concentrated on feelings hinting at disorienting dilemmas, because negative feelings can be understood as a trigger for transformation (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991; Arshavskaya Citation2017). shows the distribution of the disorienting dilemmas mentioned by the pre-service teachers (N = 51) at the onset of the TEP. At the onset of the TEP, 21 of 51 trainees expressed feelings of uncertainty at the onset of the TEP.

Table 3. Distribution of the disorienting dilemmas mentioned by the pre-service teachers (N = 51) (the number of trainees who mentioned the topic presented in brackets, multiple mentioning possible).

It can be observed that most of the disorienting dilemmas expressed in postcards were related to the self-esteem (). This seemed to be something trainees were willing to change during the TEP (cf. Taylor Citation2000). Besides the visual representations, some trainees wrote to postcards encouraging words such as ‘don't be afraid’ or ‘work hard’, as to empower themselves. Together with feelings of uncertainty, the trainees often expressed also positive feelings about teaching, for instance, they stated that they were ‘very inspired’, ‘willing to learn’, ‘willing to realise own ideas’, or ‘for the first time in my life I was called teacher, and it naturally felt good’. However, the positive feelings were often complemented with the word ‘but’, for instance, ‘I am very excited, but at the same time, I feel stressed’ or ‘I am curious, but at the same time distressed’. Also, 8 trainees out of 51 expressed only positive emotions without mentioning any feelings of uncertainty, such as ‘Finally, my dream of being a language teacher is coming true’ or ‘We got very positive feedback from our mentoring teacher. We were touching in front of the class, s/he said :)’. This can be understood as a lack of a disorienting dilemma (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991; Arshavskaya Citation2017).

As summarised in , managing or controlling the class caused uncertainty for 15 of the 51 trainees (cf. Numrich Citation1996), probably because, at the time of writing, the trainees had recently returned from a period of classroom observation at the Teacher Training School, where they had seen teachers working in loud classrooms, as the example in illustrates. Further, 12 of the 51 trainees brought up their uncertainties concerning subject-matter knowledge (cf. Andrews Citation2003). In particular, they were concerned whether their proficiency in the target language would be sufficient for the teaching profession (Huang Citation2005; Yuan and Lee Citation2014). Three trainees had concerns regarding the future of language teaching or their future employment because in Finland, the popularity of FLs other than English is waning (Kangasvieri Citation2019). The students who had not taught before were especially uncertain. For instance, one trainee stated that after the first few lessons, s/he had started to feel that s/he ‘could possibly be a good teacher’ (St. 34, Spanish). Another trainee stated that ‘the ideas seems so good at home when I plan them, but implementing them in the classroom is totally different’ (St. 35, Italian/French/Russian). Trainees with some prior teaching experience seemed more ‘relaxed’. Especially by trainees with no prior teaching experience, tensions between the ideal images of themselves as teachers and implemented practices could be observed (McConn and Geetter Citation2020). One student found the transition from the role of a student to that the role of a teacher difficult (cf. Farrell Citation2009).

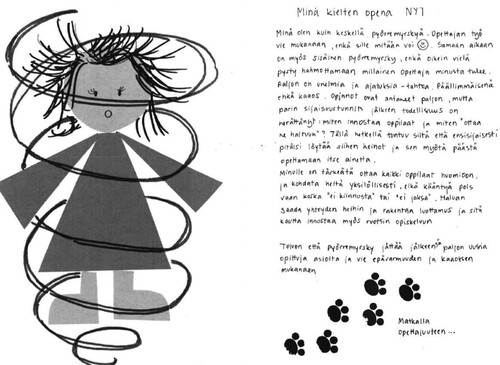

6.2. Trainees in dialogue with themselves at the end of the TEP

When postcards were opened at the end of the TEP, the trainees (N = 43) reflected on their experiences during the TEP. Seeing postcards in which their feelings were described prompted the trainees to reflect on their mentioned trigger points at the start of the TEP (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991; Taylor Citation2009). According to Mezirow (Citation1998, 190) ‘learning may be understood as the process of using a prior interpretation to construe a new or revised interpretation of the meaning of one's experience’. In responses to postcards, most trainees reported about a positive change during the TEP. shows the distribution of trainees’ reported changes in their responses to the postcards at the end of the TEP.

Table 4. Distribution of the changes reported by the pre-service teachers (N = 43) (the number of the trainees who mentioned the topic presented in brackets, multiple mentioning possible).

It could be observed that trainees’ beliefs had changed during the teacher education programme. Sixteen trainees mentioned that their self-confidence as a teacher had increased and 14 felt more secure in the classroom work, as the following extracts from the written responses demonstrate:

In the autumn, I was a little bit shy and very attached to the lesson plan. Now, I have the courage to skip the plan if needed and to live with the group. [–] (St. 1, Italian/French/Russian)

Classroom management, which was my greatest challenge, does not faze me anymore. I feel that I have found ways to manage the group. I am not scared anymore if it gets loud sometimes. Somehow, I have the courage to be imperfect [–] (St. 49, Swedish)

At the end of the TEP, 11 of 43 trainees had noticed that their work with learners, especially with younger learners, was motivating, as the following extract illustrates:

[–] My best experiences have been those in which I successfully created a good communication channel with my students. [–]. I still feel teaching younger learners is the most suitable for me. I think that with them, communication is more authentic, and I get something for myself when I teach. (St. 28, German)

Three trainees of 43 brought up their disappointment towards the TEP. Some trainees would have needed more support from the mentoring teachers to work more creatively in the classroom and realise their own ideas (cf. Johnson Citation1994). For instance, one trainee mentioned that s/he feels that his/her lessons are ‘planned for the mentoring teacher’ (St. 47, Swedish) and one trainee indicated that s/he ‘had to teach as written in the lesson plan’ (St. 32, Italian/French/Russian). To summarise, in the context of our study, the role of the supportive relationship (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991) did not seem to be significant during the learning process.

7. Discussion

Based on narrative-like writings and drawings collected at the onset and end of the one-year TEP, we aimed to demonstrate the learning processes and development of 51 FL teacher trainees. The theory of transformative learning (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991) served as the theoretical framework for our analysis. The postcard writing and drawing activity allowed the trainees to have a dialogue with themselves and to reflect critically on their own development (Mezirow Citation1991). The reflective writing activity sheds light on their development from student to teacher (cf. Taylor Citation2009), which is ‘not a simple transition’ (Farrell Citation2009, 183).

The results of this study clearly demonstrate that almost all trainees experienced a disorienting dilemma of some kind at the onset of teacher education (Weinberg et al. Citation2020; McConn and Geetter Citation2020). Most of the expressed feelings of uncertainty were related to self-esteem as a teacher. Besides these, we discovered the following factors causing uncertainty: classroom work, subject-matter knowledge, concerns about the teaching profession, and trainees’ ‘survival’ during the TEP. Concerns about knowledge of the subject matter mostly described how the trainees succeeded in using the target language in classroom. Our findings indicate that such crises are needed to catalyse the learning or development process (cf. Meijer, De Graaf, and Meirink Citation2011). Despite their feelings of uncertainty, the trainees in this study expressed their positive expectations through the drawings depicting them as ideal language teachers and the encouraging, motivating words written to their future selves (cf. Illeris Citation2014b).

These findings indicate that the development of trainees varied individually during the TEP. The most remarkable benefit of the TEP was that it increased the 16 trainees’ self-confidence (N = 43). Despite this, at the end of the TEP, 7 of the 43 trainees still felt insecure and felt that they were not teachers. The results of this study indicate that besides growing self-confidence as a teacher, the learning had taken place especially in the category classroom work. At the end of the TEP, 11 of 43 trainees found working with learners motivating and three trainees mentioned that classroom management was not scary anymore. Regarding this, the Finnish teacher education system seemed to have a positive influence on trainees learning process. Our findings indicate that within the one-year TEP, Finnish trainee teachers encounter many factors that cause ‘reality shock’ (Veenman Citation1984; Farrell Citation2009). Hence, Finnish teacher education seems to be successful in reproducing environments similar to those that teachers will face when they graduate (Pollari, Salo, and Koski Citation2018). This may smoothen their entry as teachers in mainstream schools. However, alternative learner-centric teaching models should have been offered by mentoring teachers so that trainees can ‘have successful encounters with alternative instructional practices’ to change their teacher-led instructional practices (Johnson Citation1994, 451). This calls for mentoring teachers and teacher educators to make their tacit knowledge visible, for instance, using think-aloud methods (Sheridan, Durksen, and Tindall-Ford Citation2019).

At the start of the TEP, the trainees were more concerned about students’ negative reactions during the lessons and causing problems in the classroom work (cf. Gatbonton Citation2008). However, after gathering more teaching experiences during the TEP, positive feedback from the learners motivated the trainee teachers and some of them reflected at the end of the TEP on how they could activate the learners to use the target language in the classroom. Moreover, our findings indicate that the trainees would have needed more support from their mentoring teachers, especially regarding working more creatively in the classroom. A few trainees found validation for their career choice, while a few others remained very insecure. To summarise, even if several trainees go through the same TEP, they experience teaching individually and are at different stages of development at the end of the programme.

Generally, these findings indicate that the TEP at a Finnish university influenced trainee development and transformed the lives of many trainees (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991), although the course duration was limited (from September to May). Given that teaching is invariably associated with uncertainty, TEPs should impart knowledge about such uncertainty and provide tools for reflection and discussion (cf. McConn and Geetter Citation2020). This study's findings support those of other studies that have found reflective writing to be a helpful tool for analysing the development of teachers (Coffey Citation2015; Arshavskaya Citation2017). In our case, postcard writing enabled the observation of the transformative learning process (Mezirow Citation2000) among the trainees during the TEP. The trainees had a chance to adopt new perspectives on disorienting dilemmas (Mezirow Citation1978, Citation1991; Cranton Citation2009). As teaching always includes some uncertainty, teachers’ educators should inform trainees about this uncertainty and offer the tools to manage it. To this end, the postcard drawing and writing at the onset and end of the TEP provided a tool for reflection and discussion. Moreover, trainee teachers need guidance in writing about their teaching experiences (cf. Arshavskaya Citation2017). The findings of this study confirmed that the content of language TEPs should include the work of language teachers and the teaching itself, that is, how to teach languages and not only how languages are learned (cf. Yuan and Lee Citation2014). Because teaching is a complex task to master, it is difficult to describe or teach it to others.

8. Conclusion

In this study, we report on a study we conducted exploring Finnish pre-service language teachers’ learning processes documented in multimodal postcards produced at the onset and end of the one-year TEP. The importance of this topic was justified by the fact that reflective writing is beneficial when teaching is learned. Additionally, research projects that combine the examination of both writing and drawing are currently receiving more attention in the field of language teacher education. In this study, various concepts generated based on the theory of transformative learning (disorienting dilemma, critical reflection of individual experiences, dialogue, and rebuilding lives) were utilised to capture the development of trainee FL teachers during the one-year TEP and how the trainees interpreted their experiences at the end of the TEP. The multimodal data were collected from the trainee teachers at the onset (N = 51) and end (N = 43) of the one-year TEP at a Finnish university. The findings revealed that trainee teachers experienced various uncertainties at the programme's onset: they simultaneously had ideal images of themselves as teachers, but also had disorienting dilemmas. Based on our results, at the onset of the TEP, positive feelings were represented mostly in drawings and negative in writings. Most of the disorienting dilemmas were related to feelings of insecurity and inexperience. Other categories causing uncertainty were classroom work (such as noisy classrooms), subject-matter knowledge (linguistic skills), teaching profession and the TEP. In general, the findings clearly indicated that the language teacher education programme influenced trainees’ learning processes. Regarding language teacher education, there is a need for more studies that focus on the learning process of pre-service teachers to increase the understanding of how language teachers learn from their experiences and how these could be thematised and ‘didacticised’ or adapted into TEP practices.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and the teacher trainees who participated in the study for their open-minded cooperation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Minna Maijala

Minna Maijala, Ph.D. in German (2003), Ph.D. in Education (2010), is Associate Professor in Language Teaching and Learning at the School of Languages and Translation Studies, University of Turku, Finland. In 2004–2018, she has worked as a senior lecturer at the Language Centre, University of Turku and at the Department of Teacher Education, University of Turku. Her research interests are teaching and learning German as a foreign language, the cultural content in foreign language teaching, and foreign language teaching materials.

References

- Andrews, Stephen. 2003. “Teacher Language Awareness and the Professional Knowledge Base of the L2 Teacher.” Language Awareness 12 (2): 81–95.

- Arshavskaya, Ekaterina. 2017. “Becoming a Language Teacher: Exploring the Transformative Potential of Blogs.” System 69: 15–25.

- Bailey, Kathleen M. 2006. Language Teacher Supervision: A Case-Based Approach. Stuttgart: Ernst Klett Sprachen.

- Barkhuizen, Gary, Phil Benson, and Alice Chik. 2014. Narrative Inquiry in Language Teaching and Learning Research. New York: Routledge.

- Borg, Simon. 2006a. “The Distinctive Characteristics of Foreign Language Teachers.” Language Teaching Research 10 (1): 3–31.

- Borg, Simon. 2006b. Teacher Cognition and Language Education. Research and Practice. London: Continuum.

- Borg, Simon. 2011. “The Impact of in-Service Teacher Education on Language Teachers’ Beliefs.” System 39 (3): 370–380.

- Brandão, de Laurentiis, and C. Ana. 2019. “Imagining Second Language Teaching in Brazil: What Stories do Student Teachers Draw?” In Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words, edited by Paula Kalaja, and Silvia Melo-Pfeifer, 197–213. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Burns, Anne. 1999. Collaborative Action Research for English Language Teachers. Cambridge: CUP.

- Burton, Jill. 2009. “Reflective Practice.” In The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education, edited by Anne Burns, and Jack C. Richards, 298–307. Cambridge: CUP.

- Cabaroglu, Nese, and Jon Roberts. 2000. “Development in Student Teachers’ Pre-Existing Beliefs During a 1-Year PGCE Programme.” System 28 (3): 387–402.

- Choi, Tat H. 2013. “Autobiographical Reflections for Teacher Professional Learning.” Professional Development in Education 39 (5): 822–840.

- Coffey, Simon. 2015. “Reframing Teachers’ Language Knowledge through Metaphor Analysis of Language Portraits.” The Modern Language Journal 99 (3): 500–514.

- Cranton, Patricia. 2009. “Foreword.” In Creative Expression in Transformative Learning: Tools and Teachniques for Educators of Adults, edited by Chad Hoggan, Soni Simpson, and Heather Stuckey, vii–x. Malbar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

- Farrell, Thomas S. C. 2009. “The Novice Teacher Experience.” In The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education, edited by Anne Burns, and Jack C. Richards, 182–189. Cambridge: CUP.

- Gatbonton, Elizabeth. 2008. “Looking Beyond Teachers’ Classroom Behaviour: Novice and Experienced ESL Teachers’ Pedagogical Knowledge.” Language Teaching Research 12 (2): 161–182.

- Huang, Jing. 2005. “A Diary Study of Difficulties and Constraints in EFL Learning.” System 33 (4): 609–621.

- Huang, Jing. 2006. “Learner Resistance in Metacognition Training? An Exploration of Mismatches Between Learner and Teacher Agendas.” Language Teaching Research 10 (1): 95–117.

- Illeris, Knud. 2014a. “Transformative Learning re-Defined: As Changes in Elements of the Identity.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 33 (5): 573–586.

- Illeris, Knud. 2014b. “Transformative Learning and Identity.” Journal of Transformative Education 12 (2): 148–163.

- Johnson, Karen E. 1994. “The Emerging Beliefs and Instructional Practices of Preservice English as a Second Language Teachers.” Teaching & Teacher Education 10 (4): 439–452.

- Johnson, Karen E., and Paula R. Golombek. 2011. “The Transformative Power of Narrative in Second Language Teacher Education.” Tesol Quarterly 45 (3): 486–509.

- Kagan, Dona M. 1992. “Professional Growth among Preservice and Beginning Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 62 (2): 129–169.

- Kalaja, Paula, Riikka Alanen, Hannele Dufva, and Gary Barkhuizen. 2013. “Experimenting with Visual Narratives.” In Narrative Research in Applied Linguistics, edited by Gary Barkhuizen, 105–131. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kalaja, Paula, and Silvia Melo-Pfeifer, eds. 2019. Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Kalaja, Paula, and Anne Pitkänen-Huhta. 2018. “Introduction to the ALR Double Special Issue ‘Visual Methods in Applied Language Studies.’” Applied Linguistics Review 9 (2-3): 157–176.

- Kangasvieri, Teija. 2019. “L2 Motivation in Focus: The Case of Finnish Comprehensive School Students.” The Language Learning Journal 47 (2): 188–203.

- Leavy, Patricia. 2009. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

- McConn, Matthew L., and Donna Geetter. 2020. “ Liminal States of Disorienting Dilemmas: Two Case Studies of English Teacher Candidates.” Journal of Transformative Education. doi:10.1177/1541344620909444.

- Meijer, Paulien C., Gitta De Graaf, and Jacobiene Meirink. 2011. “Key Experiences in Student Teachers’ Development.” Teachers and Teaching 17 (1): 115–129.

- Melo-Pfeifer, Silvia, and Alice Chik. 2020. “Multimodal Linguistic Biographies of Prospective Foreign Language Teachers in Germany: Reconstructing Beliefs About Languages and Multilingual Language Learning in Initial Teacher Education.” International Journal of Multilingualism. doi:10.1080/14790718.2020.1753748.

- Mezirow, Jack. 1978. “Perspective Transformation.” Adult Education 28 (2): 100–110.

- Mezirow, Jack. 1991. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, Jack. 1998. “On Critical Reflection.” Adult Education Quarterly 48 (3): 185–198.

- Mezirow, Jack. 2000. “Learning to Think Like an Adult: Core Concepts of Transformation Theory.” In Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress, edited by J. Mezirow, 3–34. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, Jack. 2006. “Musings and Reflections on the Meaning, Context, and Process of Transformative Learning: A Dialogue Between John M. Dirkx and Jack Mezirow.” Journal of Transformative Education 4 (2): 123–139.

- Mezirow, Jack. 2009. “An Overview on Transformative Learning.” In Contemporary Theories of Learning. Learning Theorists … in Their Own Words. London, edited by Knud Illeris, 90–105. New York: Routledge.

- Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Numrich, Carol. 1996. “On Becoming a Language Teacher: Insights from Diary Studies.” TESOL Quarterly 30 (1): 131–153.

- Pajares, M. Frank. 1992. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning Up a Messy Construct.” Review of Educational Research 62: 307–332.

- Pollari, Pirjo, Olli-Pekka Salo, and Kirsti Koski. 2018. “In Teachers We Trust–The Finnish Way to Teach and Learn.” ie: Inquiry in Education 10 (1): 4.

- Ruohotie-Lyhty, Maria, and Anne Pitkänen-Huhta. 2020. “Status versus Nature of Work: Pre-Service Language Teachers Envisioning Their Future Profession.” European Journal of Teacher Education. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1788535.

- Sahlberg, Pasi. 2010. “The Secret to Finland’s Success: Educating Teachers.” Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education 2: 1–8.

- Sheridan, Lynn, Tracy L. Durksen, and Sharon Tindall-Ford. 2019. “Understanding the Reasoning of pre-Service Teachers: A Think-Aloud Study Using Contextualised Teaching Scenarios.” Teacher Development 23 (4): 425–446.

- Shulman, Lee. 1987. “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 57 (1): 1–23.

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Tasker, Isabel. 2018. “Timeline Analysis of Complex Language Learning Trajectories: Data Visualisation as Conceptual Tool and Method.” Applied Linguistics Review 9 (2–3): 449–473.

- Taylor, Edward W. 2000. “Analyzing Research on Transformative Learning Theory.” In Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress, edited by Jack Mezirow, 285–329. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Taylor, Edward W. 2007. “An Update of Transformative Learning Theory: A Critical Review of the Empirical Research (1999–2005).” International Journal of Lifelong Education 26 (2): 173–191.

- Taylor, Edward W. 2009. “Fostering Transformative Learning.” In Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace, and Higher Education, edited by Jack Mezirow, and Edward Taylor, 3–17. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Tillema, Harm H. 1998. “Stability and Change in Student Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching.” Teachers and Teaching 4 (2): 217–228.

- Tsui, Anne. 2003. Expertise in Teaching: Case Studies of ESL Teachers. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Veenman, Simon. 1984. “Perceived Problems of Beginning Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 54 (2): 143–178.

- Virta, Arja. 2002. “Becoming a History Teacher: Observations on the Beliefs and Growth of Student Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 18: 687–698.

- Weinberg, Andrea E., Carlie D. Trott, Wendy Wakefield, Eileen G. Merritt, and Leanna Archambault. 2020. “Looking Inward, Outward, and Forward: Exploring the Process of Transformative Learning in Teacher Education for a Sustainable Future.” Sustainability Science 15 (6): 1767–1787.

- Yuan, Rui, and Icy Lee. 2014. “Pre-service Teachers’ Changing Beliefs in the Teaching Practicum: Three Cases in an EFL Context.” System 44: 1–12.