ABSTRACT

Researching mindsets has become a topic of considerable interest in language learning. However, the majority of studies tend to focus on learners and their mindsets, with very little research examining the mindsets of teachers, either in-service or pre-service. Yet, teachers' mindset beliefs about their competences as educators are likely to be fundamental to their willingness to engage in professional development and how they cope with challenges. In this study, we addressed two research questions: 1. What are pre-service teachers' mindsets about diverse language teaching competences? 2. In what ways do pre-service teachers explain their mindset beliefs about language teaching? Data were collected from 12 pre-service language teachers in Austria and Norway using two semi-structured interviews, a short background questionnaire, and a sorting task prior to the second interview. During the sorting task, the teachers arranged statements along a continuum and were asked in the following interview to explain their sorting. The findings revealed a set of interrelated beliefs best thought of as a system including beliefs beyond malleability. There was no evidence of categorical mindset beliefs but more orientations towards a particular perspective. The study raises important questions for research methodologies using binary dichotomies and single-point data collection tools.

1. Introduction

Mindsets refer to the beliefs an individual has about the malleability of some human characteristic or ability (Dweck Citation2006). Typically, research has focused on beliefs about intelligence or academic abilities, although there has also been research examining mindsets on other domains such as personality (Schleider and Weisz Citation2016), happiness (Van Tongeren and Burnette Citation2018), and relationships (Lou and Li Citation2017). In education, research on mindsets has mushroomed (see Sisk et al. Citation2018 for a review), and they have also become a topic of considerable interest in respect to language learning specifically (e.g. Lou and Noels Citation2016, Citation2017, 2019; Mercer and Ryan Citation2010).

Despite the growing interest in this topic, the research remains relatively imbalanced. Firstly, different subject domains are differently represented and the research on language learning, especially languages other than English, is relatively scant (for exceptions, see Lanvers Citation2020). Secondly, the majority of mindset studies have tended to focus on learners, with very little research examining the mindsets of teachers, either in-service or pre-service (for an exception, see Irie, Ryan, and Mercer Citation2018). Yet, teachers’ mindset beliefs about their competences as educators are likely to be fundamental to their willingness to engage in professional development (Dweck, Citation2014). Importantly, these beliefs also appear to be connected to how teachers cope with challenges they may encounter throughout their careers and can thus be influential for their sense of wellbeing and resilience (e.g. Zeng et al. Citation2019). Among pre-service teachers, mindset beliefs are especially important to understand as these are teachers who are still developing their professional competences. If they can be supported in promoting a growth mindset, they will be more likely to make the most of the learning opportunities available now and in the future and are likely to display more resilience and be better able to protect themselves against burnout throughout their careers. Finally, a third problem within mindsets research has been the predominance of quantitative studies and thus a tendency to reduce mindsets to narrow conceptualisations and fragmented individual beliefs, which limits the potential to understand them as ‘meaning systems’ comprised of multiple beliefs (Dweck and Yeager Citation2019).

In this study, we investigated the teaching mindsets among pre-service foreign language teachers in the final stages of their studies in Norway and Austria. The study adopted a qualitative approach to understand the complexity and nuance of mindset beliefs. Given the absence of existent work in this area, we chose to adopt a more exploratory methodology to enable us to generate insights grounded in the situated complexity of the data.

2. Literature review

2.1. Complexifying mindsets

Mindsets are the beliefs an individual has about the malleability of some aspect of human nature (Dweck Citation2006). Fixed mindsets refer to beliefs an individual may hold which suggest that an aspect of a person’s intelligence or character is unchangeable; it is a fixed given attribute. In contrast, a growth mindset refers to beliefs that intelligence and character can be changed, and potentially improved.

Work by Dweck and colleagues have advanced our understandings of how these beliefs affect our behaviours, emotions, motivations, and achievement (see, e.g. Dweck and Yeager Citation2019; Haimovitz & Dweck Citation2017); however, work has tended to be largely quantitative in character and has typically by design simplified the notion creating a simple dichotomy between fixed mindsets and growth mindsets. Yet, the common usage of the term mindset implies ‘a set of beliefs or attitudes’ (Oxford Languages and Google). Dweck and Yeager (Citation2019) also conceptualised mindsets as ‘meaning systems’ in which multiple sets of motivational beliefs come together and indeed this was Dweck’s original starting point. In language education, through qualitative work, Mercer and Ryan (Citation2010) and Ryan and Mercer (Citation2012a) also drew attention to the problematic binary positioning of learners holding solely either a fixed or growth mindset and instead they suggested conceiving of mindsets as stretching along a continuum with many students often being somewhere around the middle with a blend of both fixed and growth aspects. Lou and Noels (Citation2019) also raised questions about the ‘categorical’ nature of mindsets and suggested most people have a mixture of beliefs with an individual rarely subscribing exclusively to one set of beliefs, even within a single domain. As such, it may make more sense to talk of a ‘mindset orientation’ in which a person tends towards a certain way of framing their thinking about ability in a domain without it being seen as categorical. Interestingly, Lou and Noels (Citation2019) go on to suggest that the complexity of mindset beliefs may be especially acute in language learning given that multiple effort- and malleability-related beliefs come together to affect one’s understanding of how able someone is to learn a language. In sum, Lou and Noels (Citation2019) argue that given the multiple competences and abilities which come together in language learning, there is a need for a greater understanding of this complexity in mindset work (see also Mercer and Ryan Citation2009).

These multiple domains also point to a second area of complexity within mindsets research, namely, the establishing of a domain. Traditionally, within education, mindset beliefs are researched in specific domains such as beliefs about intelligence (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, and Dweck Citation2007) or within specific subject areas such as maths (Bostwick et al. Citation2017) or foreign language learning (Lou and Noels Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2019; Mercer and Ryan Citation2010; Zarrinabadi, Rezazadeh, and Chehrazi Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Their domain-specific character means that individuals may hold different mindsets in different domains without any sense of paradox or inconsistency. In other words, an individual may have a more growth mindset orientation about language learning but a more fixed mindset orientation about their artistic abilities. However, even within an area such as language learning, people may hold differing beliefs in domains such as their speaking ability and their ability to write in the foreign language (see also Mercer and Ryan Citation2010; Ryan and Mercer Citation2012a). As such, when researching mindsets, the level and nature of domain under investigation needs to be clearly stated.

The implications for this study are to begin from the premise that the domain is important to define, that multiple domains may interconnect in diverse and potentially contradictory ways, that a domain of mindset beliefs is comprised of multiple sets of beliefs which may interact in complex ways, and thus that mindsets are best thought of as an interrelated set of beliefs which may blend in complex ways leading to a mindset orientation more than categorical belief frame.

2.2. Teacher mindsets in teacher education

Typically, the focus of mindset work in most disciplines has been on the learner and their mindsets about their intelligence, academic abilities, or specific subject abilities. In comparison, there has been notably less research examining teacher mindsets. Interestingly, the limited work on teacher mindsets that does exist usually investigates what mindsets teachers have about their learners’ abilities and often examines the subsequent effects of these mindsets on their teaching behaviours (see, e.g. Patrick and Joshi Citation2019; Rissanen et al. Citation2019).

In contrast, the domain of teaching competences and teachers’ mindsets about their own abilities as educators in a specific subject area remain rare. Dweck (Citation2014) reports on a PhD conducted by Gero which examined teacher mindsets and concluded that those with a growth mindset were more open to feedback, more likely to engage in professional development, and more willing to take part in peer observations. She highlights in particular the problems for pre-service teachers who may have fixed mindsets about their abilities as teachers or see their skills as being based on some natural talent for teaching. She suggests that teachers with a fixed mindset may end up leaving the profession concluding that, ‘they didn't really have the talent in the first place or that the kids were intractable' (Dweck, Citation2014, 13). Given the high rates of attrition across the profession, especially within the early years of the career (e.g. Borman and Dowling Citation2008; Ingersoll Citation2003), it would be especially important to understand any beliefs that may be inhibiting teacher growth and retention.

In Second Language Acquisition, Mercer (Citation2018) has argued that research has tended to focus on learners to such an extent that the psychology of the teacher remains under-examined in comparative terms and this is most certainly true as far as mindset research is concerned. One of the only studies on teacher mindsets in language education forms the inspiration for this study. Irie, Ryan, and Mercer (Citation2018) conducted a Q methodology study with 51 pre-service teachers in Austria to understand their mindsets about language teaching. In a Q study, participants are asked to sort and order a series of statements along a continuum in a forced template pyramid shape. In that study, the statements were drawn from the literature and the analysis of written narratives about ‘good language teaching’ from a different sample of the same target population of pre-service teachers. This resulted in a selection of 56 statements covering a broad range of language teacher competences. The research found that the teachers overwhelmingly tended towards the profile of developing professional which is perhaps not surprising given that this population are in the process of learning to become teachers and so can be expected to have a more optimistic, growth view of the learnability of teaching competences. However, perhaps a more interesting distinction was found in regard to some initial differences in terms of certain competences. They found that some teachers distinguished between more ‘technical’ aspects of teaching as more learnable and more personality-related or social-interpersonal skills as more fixed characteristics. However, there was diversity across the teacher profiles and across the set of competences for each area of competence.

Inspired by this study and wishing to explore the area in more depth, this study took several important lessons from the work by Irie, Ryan, and Mercer (Citation2018). Firstly, it is important to view language teacher competence as comprised of multiple skills and abilities including language proficiency but also didactic, pedagogical, and social competences. Secondly, the sorting procedure was found to be an excellent method for revealing more nuanced understandings of mindsets. Being asked to sort and think aloud during or directly after the sorting process offers a valuable qualitative insight to supplement the Q method quantitative data; however, this form of data remained unexplored in Irie et al.’s (Citation2018) study. In this current study, we adopted a simplified version of a Q sorting procedure to provide a focused but open opportunity to explore mindsets in depth and in greater complexity centring on a qualitative approach and the interview data about the sort.

3. Methodology

Given the absence of research in the area of language teacher mindsets, we chose to take an exploratory qualitative design that would allow unexpected aspects of the teachers’ mindsets to emerge as well as complexity and possible paradoxes. We set the overall domain as language teaching and included subdomains to reflect competences in language knowledge, didactics, pedagogy, and social skills. As such, the study was designed around two main research questions:

What are pre-service teachers’ mindsets about diverse language teaching competences?

In what ways do pre-service teachers explain their mindset beliefs about language teaching?

3.1. Design

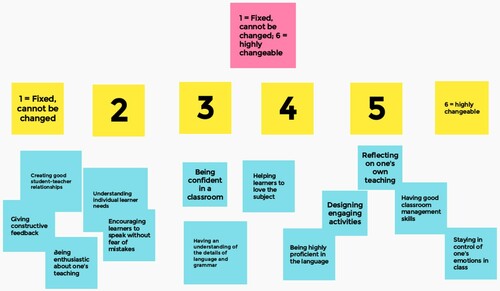

The study had three stages. In the first stage, participants were asked to complete a brief online questionnaire which gathered data in three sections. Firstly, there was a section for background data about the participants to contextualise their interviews, then a section on their wellbeing measured using the PERMA profiler (Butler and Kern Citation2016), and, finally, a section on their future selves as language teachers based on a future selves scale by Strauss, Griffin, and Parker (Citation2012). The second stage involved a semi-structured interview grouped around three main areas exploring (1) students’ biographies as language learners and teachers including their self-concept as teachers, (2) their beliefs about language teaching and learning, and (3) their overall sense of wellbeing. These interviews lasted between 31 mins (shortest) to 62 mins (longest). Approximately one week after the first interview, the students were sent an interactive whiteboard (jamboard) with 13 statements about language teaching that they were asked to sort on a scale from 1 to 6 (from not changeable at all to highly changeable) (see ). All whiteboards were identical in format when presented to students.

The 13 statements were chosen and adapted from among the 56 statements selected for the Q methodology study by Irie, Ryan, and Mercer (Citation2018). In this study, we needed to reduce the number of statements to make it feasible for participants to sort them meaningfully and to be able to reflect on each of the competences and how they relate to each other in the subsequent interview. When selecting the statements, we organised the 56 statements into four main categories representing domains identified as didactic teaching skills, subject knowledge, teacher personality, and interpersonal social competences as inspired by the groupings in Irie, Ryan, and Mercer (Citation2018). From these 56, we collectively agreed on those statements which we felt were most central to the concerns of this population across these areas.

Once the participants had completed the sorting of the statements on the digital whiteboard in their own time, we met for a second interview so the participants could explain their reasoning for their sorting of the statements. This interview also followed a semi-structured protocol which was focused primarily on participants explaining the thinking behind their categorisations. There were three main sections: (1) their general response to the task, (2) details about their sorting of items and rationale, and (3) their reflections and thoughts related to taking part in the study and any other questions and comments they may have. During these interviews, the participants could make changes to their sorting if they wished. These interviews lasted between 18 mins (shortest) to 49 mins (longest). In sum, both sets of interviews generated a total data corpus across both contexts of 142, 484 words.

3.2. Participants and context

The study explicitly sought to work with pre-service teachers in Austria and Norway. There were two main reasons. Firstly, both researchers had extensive prior experience in these contexts and thus were sensitive to contextual variation and nuance. Secondly, the contexts of pre-service education in both settings were comparable, for example, in regards to choosing two subjects to teach at school and a separation of subject, pedagogy, and language teaching methodology in the pre-service education programmes. Although there are naturally differences in the systems, the overall teacher education structure and subsequent teaching roles meant that they were meaningfully comparable.

Each researcher approached students in their respective teacher education programmes by an email sent to mailing lists asking for volunteers to take part in the study. Participants (n = 12) were presented with an information sheet and consent form to complete before any data were collected. The study was ethically approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data. Students opted in by contacting the respective researcher directly and expressing their interest in taking part in the study. As a form of reciprocity, after data were collected, students were provided useful resources and articles about teacher mindsets and wellbeing. A table with the basic biographical data and pseudonyms of the twelve participants is provided below in .

Table 1. Participants’ biographic information.

3.3. Analysis

The digitally recorded interviews were fully transcribed for content using intelligent verbatim transcription. At the first stage of the data analysis, interviews from two participants, one from each context, were thoroughly read and coded inductively by both researchers separately. Throughout the analytical process, we used our institutions’ respective tools for qualitative analysis, NVivo and Atlas. During this first reading, preliminary categories were drafted, shared, and discussed. The initial codes were mainly related to the main domains of didactic competences, language knowledge, teacher personality and interpersonal social competences, as well as three dimensions of growth orientations (fixed, growth, mixed). Furthermore, prototypical text passages, and rules for distinguishing different categories were formulated. At the second stage, each researcher analysed half of the data set. Thereafter, the coding list of each researcher was shared and discussed in order to reach a mutual understanding of the main categories and emerging themes and to enhance the trustworthiness of the study. A detailed coding list was made with codes for the main domains, for each competence in the sorting task, and codes to categorise statements related to a fixed or growth mindset. Additional important categories were locus of control, wellbeing, context, experience, and interrelationship between factors. At the third stage, one of the researchers analysed the full data set using the agreed coding procedures and categories. Next, a preliminary analytical vignette of each participant was written, including main themes and key data extracts. At the final stage of the analysis, the vignettes and all coding themes were discussed in-depth by both researchers at a final meeting. After another round of merging and renaming some categories, the final list of themes related to this study’s RQs included the following major themes:

4. Findings

4.1. Mindset orientations

When studying the pre-service teachers’ categorisation of the 13 different competences solely based on the sorting categories (see ), one gets the impression that they are strongly oriented towards growth. The lowest mean score is 3.8 (Being enthusiastic about one’s own teaching, Helping learners to love the subject), whereas the highest score is 5.5 (Giving constructive feedback) with most statements being higher than 4. In fact, none of the participants put any statement in category 1 and only three (Fredrik, Petra, Lara) placed any in category 2.

Table 2. Mean Scores on Malleability for Each Statement in the Sorting Activity

Furthermore, when initially discussing the sorting of the competences as a task, all participants stated that no competences are completely fixed, thus indicating an overall growth orientation to being and becoming a teacher. However, several students (Klara, Maria, Siri, Thora, Hans) stated that they wanted to believe that everything can change. As Klara explained, ‘But it was a little difficult for me to sort it because I, I want to be positive on these sort of things, and to say: Everyone can change everything they want’. Interestingly, Thora said that she believes her generation has been brought up with the beliefs that change is always possible:

Maybe I'm a bit naive. If you can say that. I tried being like critical against my own opinions that I may be like, I think maybe I'm a typical millennial there. I think maybe every theme can be thought changed, learned.

When the participants elucidated on their sorting, most of the pre-service teachers clarified that several competences were only malleable to a limited degree. For example, Mia explained: ‘Okay, so I started at the bottom with one. I didn't put anything there because I think all of these things can be changed, but only to a certain degree.’ Although there is considerable variation in the data, there was a general tendency to position personality type competences as a more fixed orientation and didactic, pedagogical and linguistic type competences as a more growth orientation. Thus, some of the lowest ranked statements during the sorting task were ‘Being enthusiastic about your subject’, ‘Staying in control of one’s emotions’, and ‘Being confident in a classroom’. According to Fredrik, your personality and abilities are more or less set and difficult to change once you have become a teenager. Talking about ‘Being enthusiastic about your subject’, Fredrik explained:

I mean, you can fake it, but I don't think you can really learn to be enthusiastic. So, I think this enthusiasm and being in a classroom, it is a joy that some people have and others don’t, and you can try to teach people to be enthusiastic about something, but I'm not sure how well that would work, if they already or if they don't already enjoy it in some way.

Moreover, several participants (Mia, Doris, Klara, Fredrik, Lara, Lars) perceived being confident as a character trait that cannot be easily changed. Doris stated, ‘I think confidence is sometimes very much tied to personality, and you can’t change your personality’. Also staying in control of one’s emotions was perceived as being hard to alter by some of the students (Fredrik, Hans, Thora, Doris, Mia), as your emotions were seen as strongly tied to who you are as a person. Thora explains: ‘But I think emotions are hard to control, (…) because I think you can train but I think it's harder to train. I think that's more based on you as a human being’. Other competences such as the ability to interact with learners and to understand their needs were also perceived of as being related to personality by some participants (Doris, Petra, Lars, Fredrik, Klara), and thus they viewed some teachers as being naturally better with people than others. Doris, for example, confessed she struggles with building a good student relationship:

I think creating a good student-teacher relationship, when I compare myself to other student teachers, I really struggle with that. Um, so, I'm not sure if that's my personality, or if it's something I can change. I haven't found something an angle which I could change or work on, because I'm trying my best.

On the whole, the pre-service teachers tended to believe that didactical, pedagogical and linguistic competences are highly changeable and these competences can develop as long as you make an effort. For example, Susi perceived having good classroom management skills as quite changeable because it is possible to learn certain techniques: ‘I think there are so many great tips. And then you can easily change them and it's effective, and students notice, if you do that, and you yourself notice if it's efficient what you're doing, so I also think it's easier to change'. Eight participants (Fredrik, Thora, Doris, Klara, Mia, Lars, Lara Siri) placed one or both of the statements on linguistic competences on position 6 and saw them as highly changeable. Mia explained: ‘I think this is totally changeable because you can, if you're motivated, and you have a seminar, you can learn all those things'. Mia’s comment pointed to an aspect discussed by some of these pre-service teachers which suggests that possibly having been taught a competence in a course or in school implies that this must be learnable and thus malleable.

4.2. Mindsets systems of beliefs

As participants explained the reasoning for their mindset orientations, it became apparent that there were other key beliefs which interconnected with their mindset beliefs. This indicates that mindsets function as systems of connected beliefs, rather than isolated beliefs of malleability. In these data, the two most notable sets of beliefs which appear to be tightly interwoven with the mindsets beliefs of malleability were beliefs about locus of control and beliefs about natural progression or acquisition of competences.

4.2.1. Locus of control

When discussing the competences around social skills, six participants (Doris, Lara, Thora, Klara, Mia, Susi) explained that these could not be completely malleable because they were not entirely in your control and so they might be rather fixed. In essence, you can be as enthusiastic as you like, encourage your learners to speak in class and work on building strong relationships, but if your learners are not willing to engage, there is little you can do. According to Thora,

Of course, I want to, there's a lot of things I wanted to say highly changeable here. But again, I think not just focusing on myself, but it's going to be a relationship, there's going to be two parts here. And you can do as much as you can do, but that's the hard part. When it comes to human relationships, and relations as in how much are you in charge of another person's thinking and feeling surrounding another human?

4.2.2. Beliefs about natural progression or acquisition

Another interesting finding was the trust in time and experience rather than conscious effort for developing their competences, especially again in regard to social skills expressed by some participants. ‘Experience is the keyword’, according to Maria. In respect to the statement ‘Understanding individual learners’ needs’, Lara stated,

I think that's also highly changeable. Because I think maybe it can be difficult when you start to teach. And that's why I put it on the highly changeable because I think the more experience you have with dealing with the students at different ages, I think, the easier it can get to see kind of patterns.

4.3. Dynamism of mindset orientations

Another dimension that became evident during the study was the dynamism of mindsets. Even within the course of the interview, three of the participants (Petra, Lars, Thora) displayed a change in their mindsets. As mindsets have typically been portrayed as deeply rooted beliefs, it was interesting to note how the reported beliefs changed during the interviews when students had time to reflect on and explain their statements. The biggest changes were made by Petra, who ended up reorganising several competences during the interview as she reflected out loud on her thinking. Interestingly, Lars had the impression that he had developed a stronger growth-oriented mindset as a result of having done the sorting task: ‘Before I came here today some of these aspects I maybe thought of them as quite fixed. And now when I got the time to consider it. Yeah.”

5. Discussion

From the analysis of the data, there are a number of issues with important implications in terms of the complexity of mindset conceptualisations and several methodological concerns.

5.1. Mindset orientations

Firstly, there were hardly any categorical beliefs evinced in the data. Even the statements placed on position 6 on the jamboard were often talked about in more complex terms. These data reinforced the notion of a mindset orientation, rather than a binary categorical distinction between fixed and growth. Overall, the group tended towards a more growth orientation generally about teacher competences but, on closer inspection, their overall mindset and specific competence mindsets were in fact more typically a blend of fixed and growth perspectives with a leaning one way or the other. This is in line with other work which has also questioned the simplistic dichotomy which dominates mindset research and discourse (e.g. Lou and Noels Citation2019; Mercer and Ryan Citation2010; Ryan & Mercer Citation2012a).

In terms of the orientations which predominated in these data, the technical aspects of language teaching including didactic, pedagogical and linguistic competences were often seen from a more growth orientation perspective. This is perhaps not surprising given that these pre-service teachers are in the process of studying to become a teacher at university and this would reflect their experiences in their courses (see also Irie, Ryan, and Mercer Citation2018). However, in contrast, competences seen as being more tied to personality factors or social skills tended to be viewed as more fixed. This confirms the initial work by Irie, Ryan, and Mercer (Citation2018). Given the criticality assigned to socio-emotional competences in language teaching (Dewaele, Gkonou, and Mercer Citation2018), it is worrying that some of these teachers do not believe that these skills can be easily developed. Work conducted by Yeager and colleagues into the area of social and personality mindsets has found that holding a fixed mindset about personality traits can lead to lower wellbeing and stress when individuals face social difficulties (e.g. Yeager et al. Citation2014; Yeager and Dweck Citation2012). Interestingly, one of the primary causes of stress reported by teachers can stem from poor relationships with learners and social threats such as discipline issues (e.g. Lewis Citation1999; Spilt, Koomen, and Thijs Citation2011). The work on social and personality mindsets suggests that if teachers could be encouraged to develop a more growth mindset about their competences in these areas, it could also boost their resilience and protect their professional wellbeing, in particular if they encounter such problems during their careers (cf. Schroder et al. Citation2015; Yeager et al. Citation2014). In addition, work by Romero et al. (Citation2014) showed in their study that when students with lower wellbeing scores believed that their emotions were malleable, they were able to improve their wellbeing scores over time suggesting the importance for wellbeing and managing of emotions of believing that your emotions are within your control. They conclude that, ‘in the same way that intelligence theories are particularly important when students face academic challenges, emotional theories are particularly important when students are experiencing emotional challenges’ (Romero et al. Citation2014, 232). In sum, there is much scope for work to better understand teachers’ social and emotional mindsets, which have the potential to impact strongly on their professional wellbeing.

5.2. Mindsets as systems of beliefs

Lou and Noels (Citation2019) have argued against the piecemeal approach to researching mindsets arguing for the importance of understanding the ‘systems of meaning’. Recently, Dweck (Citation2017) has begun work on a theory which combines mindsets with other powerful theories in motivation research. As she explains, ‘At present, we have some powerful theories, but many seem to be isolated theories explaining isolated phenomena Because of this, we get only piecemeal glimpses of how people work and how to help them function better’ (Dweck Citation2017, 689). In this study, we also glimpsed this complexity specifically in relation to mindsets, locus of control, beliefs about natural acquisition processes, and other general beliefs about learning and teaching.

Beliefs about locus of control relate to the original framework of self theories proposed by Dweck (Citation1999) and are a core component of attributions (Weiner Citation1985). For these pre-service teachers, if they believed a competence not to be fully within their locus of control, then they inevitably tended to a more fixed orientation as this was not something they believed they could change. Although they may believe it can change per se, they do not believe they personally are able to change it. This subtle but critical distinction is an important dimension to bear in mind, especially when discussing teacher mindsets in which many competences are typically defined in terms of learner outcomes. The relationship between teaching and learning is complex but the degree of growth or fixed orientation and the relationship to locus of control would be important to understand for pedagogical practices, teacher expectations, as well as the subsequent impact on student achievement (cf. De Boer, Timmermans, and van der Werf Citation2018).

The data also revealed that some pre-service teachers believed that certain competences would be acquired without effort with time and experience. This is reminiscent of work by Ryan and Mercer (Citation2011) who found some students held beliefs about natural acquisition in the context of study abroad. The authors raised concerns about the implications for learner agency if natural processes are seen as the agent of success, rather than the individual themselves. For pre-service teachers, it would be problematic if they felt unable to proactively take action to improve certain competences, especially in case they were to encounter difficulties in this domain.

5.3. Methodological lessons learned

The approach taken in this study was innovative in its design and one we feel extremely positive about. In this short paper, we have only been able to report upon a fraction of the rich data that this method generated. In particular, given the deep rooted and often implicit nature of mindsets, it is important to allow respondents the time to reflect more deeply on their beliefs but also make distinctions between competences and facets of a domain. The sorting task in combination with semi-structured interviews allowed nuanced and complex mindset belief systems to emerge. Interestingly, the data revealed clear discrepancies between the sorting task numerical scores and how the participants then talked about these statements. This serves as an important caution for quantitative studies relying solely on numerical data about mindsets. It suggests not only the risk of reporting bias through a scripted discourse about what they know they ‘ought’ to believe, but this study also highlights the potential for change over time within an interview and on deeper reflection.

Despite the fact mindsets are often portrayed as being relatively static, there is evidence that mindsets can change across time and place (Irie, Ryan, and Mercer Citation2018; Rattan, Good, and Dweck Citation2012; Ryan and Mercer Citation2012b; Wilson and English Citation2017), and are sensitive to priming (Lou and Noels Citation2016). This has important implications for any study collecting data at a single point in time. In this study, an additional limitation concerns the fact both samples came from comparable populations in Europe and further research could extend the design to examine teachers or pre-service teachers from different countries and cultural contexts, especially given the indications of potential cultural sensitivity of mindsets (see, e.g. Jose and Ballamy Citation2012; Ryan and Mercer Citation2012). At present, cross-cultural work on mindsets is limited and Lou and Noels (Citation2020, p. 553) conclude their extensive review by stating that, ‘little is known about whether the results of language mindsets studies are generalisable outside of Western countries’. Clearly, cross-cultural work in the domain of language education would be especially important. In addition, the majority of work has been conducted with English as a foreign or second language and very little has been carried out within domains of languages other than English (for an exception, see, Lanvers Citation2020).

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have reported on a qualitative study using an innovative research methodology to explore the mindset orientations of pre-service language teachers. It has revealed the complexity of mindset beliefs in terms of their interconnections with other beliefs and the blending of both growth and fixed perspectives about a single competence and within a domain. This suggests the value of research which enables such complex systems of beliefs to emerge and be better understood from a holistic, rather than fragmented perspective. In addition, this study focused on a neglected population who are extremely important to understand as their mindsets about their own competences as educators will be likely to impact not only on their willingness to engage in professional development now and in the future, but also their wellbeing and sense of agency. Teacher education programmes could consider addressing these mindsets explicitly and, indeed, this kind of sorting task may be one useful pedagogical tool to trigger reflection and critical discussion. This study hopes to open the agenda for research into language teacher mindsets and further research is needed to understand mindset orientations across domains, in diverse contexts, with different languages, and with teachers across the career trajectory. The almost complete absence of any work in this area suggests a rich agenda for future studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Åsta Haukås

Åsta Haukås is a professor of applied linguistics and language teacher educator in the Department of Foreign Languages at the University of Bergen, Norway. Her research interests include multilingualism, metacognition on language learning and teaching, language teacher psychology, and language teachers' professional development.

Sarah Mercer

Sarah Mercer is Professor of Foreign Language Teaching and Head of ELT at the University of Graz. She is the author, co-author and co-editor of several books in the field of language learning psychology. In 2018, she was awarded the Robert C Gardner Award for excellence in second language research.

References

- Blackwell, L., K. Trzesniewski, and C. S. Dweck. 2007. “Implicit Theories of Intelligence Predict Achievement Across an Adolescent Transition: A Longitudinal Study and an Intervention.” Child Development 78: 246–263.

- Borman, G. D., and N. M. Dowling. 2008. “Teacher Attrition and Retention: A Meta-Analytic and Narrative Review of the Research.” Review of Educational Research 78 (3): 367–409. Doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308321455.

- Bostwick, K. C., R. J. Collie, A. J. Martin, and T. L. Durksen. 2017. “Students’ Growth Mindsets, Goals, and Academic Outcomes in Mathematics.” Zeitschrift für Psychologie 225: 107–116. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000287.

- Butler, J., and M. L. Kern. 2016. “The PERMA-Profiler: A Brief Multidimensional Measure of Flourishing.” International Journal of Wellbeing 6 (3): 1–48. Doi:https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526.

- De Boer, H., A. C. Timmermans, and M. P. C. van der Werf. 2018. “The Effects of Teacher Expectation Interventions on Teachers’ Expectations and Student Achievement: Narrative Review and Meta-Analysis.” Educational Research and Evaluation 24 (3): 180–200. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2018.1550834.

- Dewaele, J.-M., C. Gkonou, and S. Mercer. 2018. “Do ESL/EFL Teachers’ Emotional Intelligence, Teaching Experience, Proficiency and Gender Affect Their Classroom Practice?” In Emotions in Second Language Teaching, edited by J. Martínez Agudo, 125–141. Cham: Springer.

- Dweck, C. S. 1999. Self-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality and Development. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

- Dweck, C. S. 2006. Mindset: The new Psychology of Success. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Dweck, C. S. 2014. “Teachers’ Mindsets: Every Student has Something to Teach me.” Educational Horizons 93(2): 10–14. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013175X14561420

- Dweck, C. S. 2017. “From Needs to Goals and Representations: Foundations for a Unified Theory of Motivation, Personality, and Development.” Psychological Review 124 (6): 689–719. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000082.

- Dweck, C. S., and D. S. Yeager. 2019. “Mindsets: A View from Two Eras.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 14 (3): 481–496. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166.

- Haimovitz, K., and C. S. Dweck. 2017. “The Origins of Children's Growth and Fixed Mindsets.” Child Development 88 (6): 1849–1859.

- Ingersoll, R. 2003. Is There Really a Teacher Shortage? Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/133/.

- Irie, K., S. Ryan, and S. Mercer. 2018. “Using Q Methodology to Investigate Pre-Service EFL Teachers’ Mindsets About Teaching Competences.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 8 (3): 575–598. Doi:https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.3.3.

- Jose, P. E., and M. A. Ballamy. 2012. “Relationships of Parents’ Theories of Intelligence with Children’s Persistence/Learned Helplessness: A Cross-Cultural Comparison.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 43 (6): 999–1018. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111421633.

- Lanvers, U. 2020. “Changing Language Mindsets About Modern Languages: A School Intervention.” The Language Learning Journal 48 (5): 571–597. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1802771.

- Lewis, R. 1999. “Teachers Coping with the Stress of Classroom Discipline.” Social Psychology of Education 3: 155–171. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009627827937.

- Lou, N. M., and L. M. W. Li. 2017. “Interpersonal Relationship Mindsets and Rejection Sensitivity Across Cultures: The Role of Relational Mobility.” Personality and Individual Differences 108: 200–206. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.004.

- Lou, N. M., and K. A. Noels. 2016. “Changing Language Mindsets: Implications for Goal Orientations and Responses to Failure in and Outside the Second Language Classroom.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 46: 22–33. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.03.004.

- Lou, N. M., and Noels, K. A. 2017. “Measuring Language Mindsets and Modeling Their Relations with Goal Orientations and Emotional and Behavioral Responses in Failure Situations.” The Modern Language Journal 101(1): 214–243. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12380

- Lou, N. M., and K. A. Noels. 2019. “Promoting Growth in Foreign and Second Language Education: A Research Agenda for Mindsets in Language Learning and Teaching.” System 86: 102126. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102126.

- Lou, N. M., and K. A. Noels. 2020. “Breaking the Vicious Cycle of Language Anxiety: Growth Language Mindsets Improve Lower-Competence ESL Students’ Intercultural Interactions.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 61: 101847. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101847.

- Mercer, S. 2018. “Psychology for Language Learning: Spare a Thought for the Teacher.” Language Teaching 51 (4): 504–525. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000258.

- Mercer, S., and S. Ryan. 2009. “Beliefs About Talent: Help or Hindrance?” ELT News 60: 14–16.

- Mercer, S., and S. Ryan. 2010. “A Mindset for EFL: Learners’ Beliefs About the Role of Natural Talent.” ELT Journal 64 (4): 436–444. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp083.

- Patrick, S. K., and E. Joshi. 2019. ““Set in Stone” or “Willing to Grow”? Teacher Sensemaking During a Growth Mindset Initiative.” Teaching and Teacher Education 83: 156–167. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.009.

- Rattan, A., C. Good, and C. S. Dweck. 2012. ““It’s Ok – Not Everyone Can be Good at Math”: Instructors with an Entity Theory Comfort (and Demotivate) Students.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 731–737. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.012.

- Rissanen, I., E. Kuusisto, M. Tuiminen, and K. Tirri. 2019. “In Search of a Growth Mindset Pedagogy: A Case Study of one Teacher’s Classroom Practices in a Finnish Elementary School.” Teaching and Teacher Education 77: 204–213. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.10.002.

- Romero, C., A. Master, D. Paunesku, C. S. Dweck, and J. J. Gross. 2014. “Academic and Emotional Functioning in Middle School: the Role of Implicit Theories.” Emotion 14 (2): 227–234. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035490.PMID:24512251.

- Ryan, S., and S. Mercer. 2011. “Natural Talent, Natural Acquisition and Abroad: Learner Attributions of Agency in Language Learning.” In Identity, Motivation and Autonomy in Language Learning, edited by G. Murray, X. Gao, and T. Lamb, 160–176. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Ryan, S., and S. Mercer. 2012a. “Implicit Theories: Language Learning Mindsets.” In Psychology for Language Learning, edited by S. Mercer, S. Ryan, and M. Williams, 74–89. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ryan, S., and S. Mercer. 2012b. “Language Learning Mindsets Across Cultural Settings: English Learners in Austria and Japan.” OnCue Journal 6 (1): 6–22.

- Schleider, J. L., and J. R. Weisz. 2016. “Reducing Risk for Anxiety and Depression in Adolescents: Effects of a Single-Session Intervention Teaching That Personality Can Change.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 87: 170–181. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.09.011.

- Schroder, H. S., S. Dawood, M. M. Yalch, M. B. Donnellan, and J. S. Moser. 2015. “The Role of Implicit Theories in Mental Health Symptoms, Emotion Regulation, and Hypothetical Treatment Choices in College Students.” Cognitive Therapy and Research 39: 120–139. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9652-6.

- Sisk, V. F., A. P. Burgoyne, J. Sun, J. L. Butler, and B. N. Macnamara. 2018. “To What Extent and Under Which Circumstances are Growth Mind-Sets Important to Academic Achievement? Two Meta-Analyses.” Psychological Science 29 (4): 549–571. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617739704.

- Spilt, J. L., H. M. Y. Koomen, and J. T. Thijs. 2011. “Teacher Wellbeing: The Importance of Teacher-Student Relationships.” Educational Psychology Review 23: 457–477.

- Strauss, K., M. S. Griffin, and S. K. Parker. 2012. “Future Work Selves: How Salient Hoped-for Identities Motivate Proactive Career Behaviours.” Journal of Applied Psychology 97 (3): 580–598. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026423.

- Van Tongeren, D. R., and J. L. Burnette. 2018. “Do you Believe Happiness Can Change? An Investigation of the Relationship Between Happiness Mindsets, Well-Being, and Satisfaction.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 13 (2): 101–109. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1257050.

- Weiner, B. 1985. “An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion.” Psychological Review 92: 548–573. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548.

- Wilson, A. E., and J. A. English. 2017. “The Motivated Fluidity of Lay Theories of Change.” In The Science of Lay Theories, edited by C. Zedelius, B. Müller, and J. Schooler, 17–43. Cham: Springer.

- Yeager, D. S., and C. S. Dweck. 2012. “Mindsets That Promote Resilience: When Students Believe That Personal Characteristics Can be Developed.” Educational Psychologist 47 (4): 302–314. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.722805.

- Yeager, D. S., K. Trzesniewski, B. Spitzer, J. Powers, and C. S. Dweck. 2014. “The Far-Reaching Effects of Believing People Can Change: Implicit Theories of Personality Shape Stress, Health, and Achievement During Adolescence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106 (6): 867–884. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036335.

- Zeng, G., X. Chen, H. Y. Cheung, and K. Peng. 2019. “Teachers’ Growth Mindset and Work Engagement in the Chinese Educational Context: Well-Being and Perseverance of Effort as Mediators.” Frontiers in Psychology 10. Doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00839.

- Zarrinabadi, N., M. Rezazadeh, and A. Chehrazi. 2021a. “The Links Between Grammar Learning Strategies and Language Mindsets among L2 and L3 Learners: Examining the Role of Gender.” International Journal of Multilingualism, Doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1871356.

- Zarrinabadi, N., N. M. Lou, and M. Shirzad. 2021b. “Autonomy Support Predicts Language Mindsets: Implications for Developing Communicative Competence and Willingness to Communicate in EFL Classrooms.” Learning and Individual Differences 86: 101981. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.101981.