ABSTRACT

Self-construal refers to the process by which individuals define the self in relation to others. It underpins cognition, motivation, and social behavior. While the importance of the self is well acknowledged in the field of second language (L2) learning motivation, how self-construal is associated with L2 learning motivation in project-based learning (PBL) settings remains understudied. Further, considering the observed link between self-construal and gender, self-construal may also account for how gender differences emerge in L2 learning motivation. This study examined the associations among self-construal, gender, and motivation to learn English as a foreign language (EFL) in a PBL context. Japanese university students responded to questionnaires on self-construal and motivation after being taught by the PBL approach for one year. The results showed a prominent impact of gender and self-construal on motivation. Female students and students with higher interdependent self-construal tended to be more motivated toward L2 learning, while male students and students with lower interdependent self-construal tended to be less motivated.

Introduction

Since Dörnyei (Citation2005) proposed the second language (L2) Motivational Self System, learners’ sense of self has been drawing increasing attention in research to enable a better understanding of L2 learning motivation. Indeed, researchers in the field of L2 learning motivation have examined various aspects of the construct of self, such as the ideal L2 self, L2 self-confidence, self-concept, and self-efficacy (Dörnyei and Ushioda Citation2009; MacIntyre et al. Citation1998; Mercer Citation2014; Mills Citation2009). As the self is a complex and vast construct, some researchers consider motivation ‘as part of the learner’s identity/self’ (Dörnyei and Ushioda Citation2009, 350), while others conceptualize it as a dimension that may be guided by the learner’s self, such as self-concept (Mercer Citation2014). Despite the multitude of constructs explored by researchers, the sense of self in most motivational studies has been conceptualized as an L2 domain-specific construct. To illustrate, the ideal L2 self concerns ‘a desirable self-image of the kind of L2 user that one would ideally like to be in the future’ (Dörnyei and Ryan Citation2015, 87) and self-concept has been defined as ‘an individual’s self-descriptions of competence and evaluative feelings about themselves as foreign language learners’ (Mercer Citation2014, 53).

In contrast, self-construal refers to the process by which individuals define their ‘selves’ in relation to others (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991) and represents their general disposition beyond the domain of L2 learning. While the importance of the self is well acknowledged in the field of L2 learning motivation (Mercer Citation2014; Serafini Citation2020), research employing self-construal is extremely limited. Indeed, only two empirical studies (Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013; Tanaka Citation2020) seem to have examined L2 learning motivation using self-construal. As self-construal underpins cognition, motivation, and social behavior (Cross, Hardin, and Gercek-Swing Citation2011; Markus and Kitayama Citation1991), it is assumed to offer an approach that clarifies L2 learning motivational mechanism from a different perspective.

Self-construal is of two types: independent and interdependent (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991). Those with independent self-construal perceive the self as independent of others and place high value on autonomy and independence, while those with interdependent self-construal perceive the self as interconnected with others and strive to maintain harmonious social interactions. Prior research using the self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan and Deci Citation2017) has demonstrated the crucial role of independent self-construal in increasing autonomous motivation (Kong and Ho Citation2016; Lee and Pounders Citation2019; Tanaka Citation2020). However, given the positive link with foreign language learning motivation (Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013), interdependent self-construal – which emphasizes orientations toward social interaction – may also play a dominant role in enhancing autonomous motivation in an L2 learning context that is rich in peer interaction. Among the various learning contexts, this study focused on project-based learning (PBL) settings. As learners are required to be independent to pursue their project and simultaneously be social to enable interaction with their peers in PBL settings, both types of self-construal may play significant roles in the learning context. However, how they operate in the PBL context is yet to be explored. As self-construal is assumed to guide learners’ preferences concerning L2 learning, research employing the construct may clarify the ways in which learner motivation varies corresponding to their personal dispositions in the PBL setting. Furthermore, although male students tend to be less motivated toward L2 learning (Henry Citation2011; Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013; Yashima, Nishida, and Mizumoto Citation2017; You, Dörnyei, and Csizér Citation2016), how such gender differences emerge remains unknown. As self-construal tends to mediate the association between gender and motivation (Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013), research employing self-construal may offer new insights into attenuating the adverse effects of gender, if any. Given these gaps, this study aimed to examine the associations between self-construal, gender, and motivation to learn English as a foreign language (EFL) in PBL settings.

Literature review

Motivation

SDT (Ryan and Deci Citation2017) is the second-most frequently employed framework in the research field of L2 learning motivation (Vonkova et al. Citation2021). In the SDT framework, motivation is broadly classified into three types: intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation, based on the extent to which behavior regulation of an individual is autonomous or controlled (Ryan and Deci Citation2017). Intrinsic motivation is the most self-determined type and involves seeking enjoyment and congruence with one’s core self. Amotivation refers to a lack of motivation for a given behavior and is analogous to learned helplessness (Legault, Green-Demers, and Pelletier Citation2006). Extrinsic motivation represents externally regulated motivation and is further categorized into three types in L2 motivational research: identified, introjected, and external regulations (McEown, Noels, and Saumure Citation2014; Noels Citation2001). Identified regulation is the most self-determined type and is centered around the value and importance individuals place on behaviors. While introjected regulation refers to motivation regulated by the maintenance of self-worth, external regulation represents motivation controlled by external factors such as grades. As intrinsic motivation and identified regulation are completely or considerably congruent with the core self, these two types of motivation are classified as autonomous motivation. Introjected and external regulation are externally regulated, or derived from externally imposed norms; hence, they are called controlled motivation (Ryan and Deci Citation2017).

As self-determination is the pillar of the theory, more self-determined, autonomous motivation is important for yielding greater outcomes in various domains (Ryan and Deci Citation2017). Prior L2 learning motivation research has confirmed the positive effects of autonomous motivation (intrinsic motivation and/or identified regulation) on diverse aspects of L2 learning, such as learning outcomes (Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation2001; Oga-Baldwin et al. Citation2017; Tanaka Citation2013, Citation2017, Citation2021), self-evaluation (Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation1999), self-confidence (Pae Citation2008), intention to persist and/or motivational intensity (McEown, Noels, and Saumure Citation2014; Noels Citation2001; Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation1999, Citation2001; Noels et al. Citation2000), willingness to communicate (Joe, Hiver, and Al-Hoorie Citation2017), and engagement (Noels, Lascano, and Saumure Citation2019). On the contrary, amotivation yields detrimental consequences, such as poorer learning outcomes (Vandergrift Citation2005), a lack of motivational intensity and/or a lack of intention to continue (McEown, Noels, and Saumure Citation2014; Noels Citation2001; Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation1999, Citation2001; Noels et al. Citation2000), higher anxiety levels (Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation1999; Noels et al. Citation2000) and lower self-evaluation (McEown, Noels, and Saumure Citation2014). Concerning controlled motivation, external regulation was occasionally associated positively with outcome measures, but at a significantly lower degree than autonomous motivation (Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation1999; Noels et al. Citation2000). Furthermore, introjected regulation induced negative consequences in some conditions (Noels Citation2001; Tanaka Citation2013). In general, however, introjected and/or external regulation tend to be unrelated with outcomes, including learning outcomes (McEown, Noels, and Saumure Citation2014; Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation2001; Oga-Baldwin et al. Citation2017; Tanaka Citation2017; Vandergrift Citation2005), self-evaluation (McEown, Noels, and Saumure Citation2014), and intention to persist and motivational intensity (Noels, Clément, and Pelletier Citation2001). Considering the beneficial and detrimental consequences of autonomous motivation and amotivation, this study aimed to examine the factors that induce these types of motivation.

Self-construal and motivation

As mentioned in the introduction, there are two types of self-construal: independent and interdependent (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991). Those with independent self-construal interpret the self as being separated and distinct from others and hence, value independence and autonomy; however, those with interdependent self-construal interpret the self as being connected to others and therefore, place importance on maintaining harmonious interpersonal relationships. Given the shared property of autonomy between independent self-construal and autonomous motivation, a positive association is postulated between them. Meanwhile, those with interdependent self-construal tend to be susceptible to externally imposed values for the maintenance of interpersonal relationships (Cross, Hardin, and Gercek-Swing Citation2011). As controlled motivation is externally regulated or derived from externally imposed norms, a positive link is implied between interdependent self-construal and controlled motivation.

Evidence from prior studies supports these connections. For example, in their study of social marketing, Lee and Pounders (Citation2019) demonstrated that independent self-construal was positively associated with autonomous motivation under intrinsic goal framing. Kong and Ho (Citation2016) also demonstrated a positive association between independent self-construal and intrinsic workplace motivation. While these findings are not particularly specific to L2 learning, research in the field of L2 learning motivation has also revealed a link between independent self-construal and autonomous motivation. Tanaka (Citation2020) examined the role of self-construal in EFL vocabulary learning among secondary school students in Japan, and identified independent self-construal as a positive and negative predictor of autonomous motivation and amotivation respectively, and interdependent self-construal as a positive predictor of controlled motivation. Furthermore, as autonomous motivation positively impacted vocabulary size, independent self-construal appeared advantageous in EFL vocabulary learning.

Despite the dominant role of independent self-construal in enhancing SDT autonomous motivation, the roles played by self-construal may be adjustable according to L2 learning contexts. As a large part of vocabulary learning often consists of self-directed homework, which does not entail peer interaction, a lack of social interaction may have reinforced the prominence of independent self-construal in such a learning context. However, as language is a means of communication, L2 learning usually emphasizes social interaction. Given the social orientation of those with interdependent self-construal (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991), interdependent self-construal may strongly influence motivation in an L2 learning context that emphasizes social interactions. Indeed, the link between interdependent self-construal and foreign language learning motivation was documented in a study by Henry and Cliffordson (Citation2013). They examined the effects of self-construal on the association between gender and foreign language motivation among 269 secondary school students in Sweden and demonstrated the prominence of interdependent self-construal as the predictor of the ideal third-language (L3) self. As the ideal L3 self involves a vision for future social interactions in the target language, the association between interdependent self-construal and motivation can be attributed to the learning context that emphasizes social interaction. Although the importance of independent self-construal was demonstrated in a solitary learning context such as vocabulary learning (Tanaka Citation2020), interdependent self-construal may play a significant role in enhancing SDT autonomous motivation in an L2 learning context that emphasizes social interactions.

Gender, self-construal, and motivation

In addition to motivation, self-construal is also closely linked with gender differences. Although there is significant variation within males and females, men are inclined toward independent self-construal, while women are more likely to experience interdependent self-construal (Cross and Madson Citation1997; Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013). Reviewing research in the field of psychology, Cross and Madson (Citation1997) argued that these gender differences in self-construal impact differences in interpersonal orientation. As a sense of connectedness and relatedness with others can be enhanced by building close relationships and enjoying group membership (12), women, with their higher tendency for interdependent self-construal, are more likely to be oriented toward social interactions (14). As women tend to be more willing to share their emotions, they build more intimate interpersonal relationships (16). Further, women are more attentive and responsive, thereby facilitating smooth and harmonious interactions (10).

Given the interpersonal interactions inherent in L2 learning, it can be assumed that women are more motivated toward L2 learning. Previous research has demonstrated systematic gender differences in L2 learning motivation. Reviewing more than 20 studies on gender differences in L2 motivation, Henry (Citation2011) reported that female students tended to have higher scores in integrativeness (Gardner Citation1985) and the ideal L2 self (Dörnyei Citation2005) in most studies. Although some of the reviewed studies found statistically insignificant gender differences, Henry (Citation2011), through a comprehensive summary, suggested that female students are more likely to be motivated toward L2 learning.

Some recent studies have corroborated these findings. For example, Yashima, Nishida, and Mizumoto (Citation2017) investigated the effects of beliefs and gender on motivation and learning outcomes among first-year university students in Japan and found that women scored higher in communication orientation, ideal L2 self, and English proficiency. They also found that women’s greater interest in communication leads to a stronger vision of the ideal L2 self, positively affecting their English proficiency. You, Dörnyei, and Csizér (Citation2016) explored the impact of visionary capacity on motivational dispositions of secondary and tertiary level students in China and found that female students had a higher visionary capacity and stronger ideal L2 self. Overall, the advantages females have in L2 learning motivation have been well documented in the existing literature; however, it simultaneously indicates males’ tendency for lower motivation toward L2 learning. Given the associations between self-construal and gender, and between gender and motivation, self-construal may offer insights as to how the motivational tendencies of women and men can be fostered and mitigated.

Thus far, the study by Henry and Cliffordson (Citation2013) is the only extant empirical study to investigate the interactional effects of gender and self-construal in L2 learning motivation. As mentioned earlier, Henry and Cliffordson (Citation2013) examined the effects of gender and self-construal on the ideal L2 and L3 selves among 269 secondary school students (140 female and 129 male adolescents) in Sweden. Although no gender difference was found in the ideal L2 self, female students had higher ideal L3 self via the mediating role of interdependent self-construal. Given the involvement of self-construal in the association between gender and the ideal L3 self, self-construal may be a mediator between gender and other types of motivation, such as autonomous motivation. Insights into the influence of self-construal in the relationships between gender and motivation may have practical utility in attenuating an undesirable effect of gender, if any.

Project-based learning

As mentioned above, this study focused on a PBL context for L2 learning. PBL in L2 education ‘involves students refining and honing their language skills through the completion of projects both in and outside of the classroom’ (Laverick Citation2019, 3). Activities in PBL include planning, gathering, and discussing information, and oral or written reporting (Hedge Citation1993). PBL may also be defined as a social practice as students often socialize through a series of individual or group activities (Slater, Beckett, and Aufderhaar Citation2006). Prior research has reported various benefits of incorporating PBL into L2 learning. The most commonly cited benefits include intensity of motivation, engagement, and enjoyment; increased autonomy, independence, and self-initiation; and improved abilities to function in a group and make decisions (Stoller Citation2006). These characteristics appear to be common to either type of self-construal. As described earlier, the core properties of independent self-construal are autonomy and independence (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991); these are generally fostered through the self-directed nature of PBL (Mills Citation2009; Stoller Citation2006). In contrast, the social aspect of PBL (Slater, Beckett, and Aufderhaar Citation2006) tends to promote cooperative and collaborative skills (Stoller Citation2006); these properties are generally emphasized in interdependent self-construal, which values harmony and relatedness with others (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991). Although the properties pertinent to both types of self-construal are required in PBL settings, it is unclear how they operate in the said context. Further, gender differences in motivation are also unexplored in PBL settings. Given the postulated associations among self-construal, gender, and motivation, self-construal may account for the gender differences in this setting, if any.

The present study

The following three gaps were identified in the relevant literature. First, although prior studies have demonstrated a positive link between autonomous motivation and independent self-construal (Kong and Ho Citation2016; Lee and Pounders Citation2019; Tanaka Citation2020), the effects of self-construal on autonomous motivation may vary according to L2 learning contexts. Though PBL is likely to benefit from both types of self-construal, it is still unclear how self-construal operates in PBL settings. Second, despite the well-documented gender differences in L2 learning motivation (Henry Citation2011; Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013; Yashima, Nishida, and Mizumoto Citation2017), it remains unknown how gender is associated with L2 learning motivation in PBL settings. Third, whether self-construal can mediate the association between gender and motivation in PBL settings remains unexplored. As these issues are yet to be addressed, this study investigated the following research questions:

To what extent does self-construal predict L2 learning motivation in a PBL setting?

To what extent are gender differences in L2 learning motivation observed in a PBL setting?

To what extent does self-construal mediate the association between gender and L2 learning motivation in a PBL setting?

Methods

Participants

The participants in this study were second-year university students belonging to the department of sports and health science at a Japanese private university, who voluntarily consented to participate. Although English proficiency varied among the participants, their mean scores were approximately 450 on the Test of English for International Communication based on their self-report. As most Japanese people are not required to speak English in daily life, many students were assumed not to have frequent opportunities to use English except for English classes. Data from 180 students (118 males and 62 females) were used for the main analysis after data screening based on Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007). All the participants were Japanese, except for one who was Chinese.

Pedagogical context

The department offered four required PBL English courses over two years (with one course consisting of 15 weekly sessions × four semesters). Data were collected after the participants had taken two PBL courses (i.e. one academic year) to ensure sufficient PBL experience. The students worked on two projects (one project × two semesters), delivered four presentations (two presentations × two semesters), and wrote two papers (one term paper × two semesters) in the first academic year. While the projects in the first semester were based on information from books and articles, for the second semester, the students conducted a survey study. The project topics were chosen by the students, with examples including ‘doping in sports’ in the first semester, and ‘the effects of childhood exercise habits on adolescent athletic abilities’ in the second. As with typical PBL activities (see Hedge Citation1993; Slater, Beckett, and Aufderhaar Citation2006), students designed their own project, gathered, analyzed, and synthesized data; they then presented their study in the form of oral and written reports in each semester. Further, the students were assigned to prepare a part of their presentation weekly, practicing it, and exchanging feedback with their classmates in class. Consequently, they had frequent presentation practice through peer interactions in class. While students were required to be autonomous and independent as individual researchers, they were also expected to be social for peer interaction in class.

Instruments and procedures

This study used gender information and two types of questionnaires to measure participants’ self-construal and L2 learning motivation. Although the Self-Construal Scale (SCS; Singelis Citation1994) is commonly used to measure self-construal (Cross, Hardin, and Gercek-Swing Citation2011), the scale proposed by Takata (Citation2000) is more appropriate for the Japanese cultural context (Takata Citation2003). This study, thus, employed the scale proposed by Takata (Citation2000) to measure the students’ self-construal. See Kashima and Hardie (Citation2000) for the convergence and divergence between SCS and the scale proposed by Takata (Citation2000). The scale proposed by Takata (Citation2000) comprises four constructs (k = 20). Two constructs are designed to measure independent self-construal: dogmatism (k = 6) and individuality (k = 4). Those with dogmatism tend to be decisive and stick to their beliefs. Items for dogmatism included ‘The best decisions are the ones I make by myself’ and ‘Even if people around me have different ideas, I stick to my beliefs.’ Those with individuality tend to see themselves to be distinct from others and express their opinions. Items for individuality included ‘I always try to have opinions of my own’ and ‘I always express my opinions clearly.’ The remaining two constructs are designed to measure interdependent self-construal: dependency on others (k = 6) and evaluation apprehension (k = 4). Those with dependency on others tend to value relatedness and harmony with others. Items for dependency on others included: ‘It is important to maintain harmony with others’ and ‘When I differ in opinions from others, I often accept their opinions.’ Those with evaluation apprehension tend to be concerned about evaluation by others. Items for evaluation apprehension included ‘I care about what others think of me’ and ‘Sometimes I am worried about how things will turn out and have difficulty in getting started.’ Construct reliability was examined using SPSS 24 for Windows (IBM Corp. Citation2016). Cronbach’s alpha was .64 for dogmatism, .75 for individuality, .66 for dependency on others, and .79 for evaluation apprehension. Although dogmatism and dependency on others exhibited a reliability estimate of < .70, they were employed with caution, given their importance in the self-construal scale.

Participants’ motivation was measured in terms of the three types of SDT motivation (intrinsic motivation (k = 5), identified regulation (k = 5), and amotivation (k = 5)) as the connection between self-construal and autonomous motivation is of particular interest to the current study. A scale developed by Tanaka (Citation2021) was used to measure intrinsic motivation and amotivation. In response to the lead question ‘Why do you study English?’ items for intrinsic motivation included ‘Because learning English is enjoyable’ and ‘Because delivering a presentation in English is enjoyable,’ while items for amotivation included ‘I cannot see why I have to study English’ and ‘I won’t get anything out of learning English.’ Items for identified regulation were created drawing on Tanaka (Citation2017) and tailored to the context of PBL incorporating oral presentations as an outcome. Items included ‘Because it is important to learn English’ and ‘Because English presentation skills will be useful in the future.’ Cronbach’s alpha was .86, .82, and .83 for intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, and amotivation, respectively. The participants responded to the questionnaires during class in the first session of the third semester, i.e. after experiencing PBL lessons for one year. As language proficiency affects the quality of responses in non-native language questionnaires (Wenz, Al Baghal, and Gaia Citation2021), all the questionnaire items were written in Japanese. Further, items were rated on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree).

Data analysis

Prior to the main analysis, a Rasch analysis was conducted to convert raw ordinal data to interval data (e.g. the logit scale) using Winsteps 3.80.0 (Linacre Citation2013). In the main analysis, Rasch person logits was used on all variables except gender. Data screening was performed based on Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007) and Field (Citation2013). A total of seven univariate and multivariate outliers identified using SPSS 24 for Windows (IBM Corp. Citation2016) were deleted at this stage. Results of the other assumptions of multivariate analysis, such as normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, and the absence of multicollinearity (the variance inflation factor (VIF) < 10, and the tolerance statistic > 0.2; Field Citation2013, 325), were adequately met. Appendix A presents intercorrelations among questionnaire constructs used in this study. While a path analysis was conducted to address the first research question, a one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to answer the second research question. Concerning the third research question, a MANOVA was first performed to identify gender differences in self-construal. Further analysis may be conducted contingent upon the MANOVA results.

Results

Descriptive statistics

shows the Rasch logit descriptive statistics for the variables in this study. With a mean of 0, positive and negative logits indicate that they are higher and lower than the mean, respectively (Bond, Yan, and Heene Citation2021). As participants’ intrinsic motivation was lower than the mean, they were not intrinsically motivated to study English in this context. In contrast, as they exhibited low amotivation and high identified regulation, they were not demotivated but motivated to learn English because of the value they perceived in learning English. As dependency on others and evaluation apprehension exhibited by them were very high, they tended to have high interdependent self-construal, although the integrated Rasch estimate of this construct was slightly higher than the mean.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Self-construal and motivation

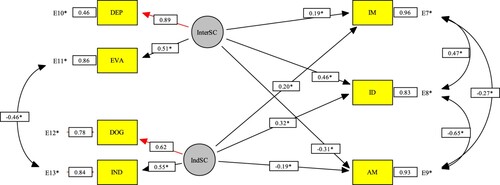

The first research question concerns the extent to which self-construal predicts L2 learning motivation in PBL settings. A path model () was created with a commonly used computer program for structural equation modeling, EQS 6.2 for Windows (Bentler and Wu Citation2012). As the assumption of multivariate normality was met (See Byrne Citation2006, for more information), the parameters in the model were estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The model yielded the following fit indices: χ2(7) 11.92, p = .10, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) .98, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) [90% Confidence Intervals (CI)] .06 [.00, .12]. While a well-fitting model exhibits values close to .95 for CFI and values less than .05 for RMSEA, the cutoff values for an adequate model fit are a CFI of .90 or above and a RMSEA of .08 or below (Byrne Citation2006). Thus, the fit of the hypothesized model was satisfactory.

Figure 1. The path model with estimated parameters. Note. InterSC = Interdependent self-construal; IndSC = Independent self-construal; DEP

= Dependency on others; EVA = Evaluation apprehension; DOG = Dogmatism; IND = Individuality; IM = Intrinsic motivation; ID = Identified regulation; AM = Amotivation.

As shown in , interdependent self-construal predicted intrinsic motivation and identified regulation positively and amotivation negatively. In other words, those participants who perceived themselves as interconnected with others and had greater social orientation tended to be motivated to a greater extent by factors such as enjoyment and the value placed in learning English, and exhibited lower degrees of amotivation in the PBL settings. However, those with lower interdependent self-construal tended to be less motivated by factors such as enjoyment and the value placed in learning English, and were more prone to amotivation. At the same time, independent self-construal was not associated with intrinsic motivation or amotivation, but it was a significant predictor of identified regulation. In other words, participants who perceived themselves as distinct from others and valued independence and autonomy tended to be more motivated because of the perceived importance of learning English. On the contrary, the degree of intrinsic motivation and amotivation did not vary according to the levels of their independent self-construal.

Table 2. Parameter estimates for self-construal predicting motivation.

Gender and motivation

The second research question concerns the gender differences in L2 learning motivation in a PBL setting. A MANOVA was conducted using SPSS 24 for Windows (IBM Corp. Citation2016) to address this issue. As Box’s M test was non-significant, the assumption of the homogeneity of covariance matrices was met. Significant differences were found between males and females on the three dependent measures, Wilks’s Λ = .96, F(3, 176) 2.75, p = .044. The multivariate η2 based on Wilks’s Λ was .05. Subsequently, analyses of variances (ANOVA) on each dependent variable were performed as follow-up tests to the MANOVA. As Levene’s F test revealed that the homogeneity of variance assumption was not met for identified regulation and amotivation, Welch’s F test was used (see Field Citation2013, for more information). The results of the follow-up ANOVA were as follows: intrinsic motivation (F(1, 127.71) 4.78, p = .031), identified regulation (F(1, 102.99) 6.34, p = .013), and amotivation (F(1, 105.81) 4.15, p = .031).

As shown in , female participants tended to have higher intrinsic motivation and identified regulation and lower amotivation, which coincides with the motivational patterns for those with higher interdependent self-construal. Conversely, male participants tended to have lower intrinsic motivation and identified regulation and higher amotivation, which coincides with the motivational patterns for those with lower interdependent self-construal.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for each gender group.

Despite the apparent mean differences as shown in , it should be noted that the gender differences were statistically significant for intrinsic motivation and identified regulation, but not for amotivation, when the alpha level of .05 was corrected using Holm’s sequential Bonferroni procedure to avoid type I errors. Nevertheless, the findings revealed that the women were more motivated than men to learn English in this setting.

Roles of self-construal in the association between gender and motivation

Although the findings of the second research question support gender differences in motivation, prior research has suggested the involvement of self-construal in these differences (Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013). A MANOVA was first conducted to examine whether gender differences exist in two types of self-construal using SPSS 24 for Windows (IBM Corp. Citation2016). The results showed no significant differences between the gender groups on the two dependent measures, Wilks’s Λ = .99, F(2, 177) 1.33, p = .268. As shown in , the degree of independent and interdependent self-construal did not vary with gender. As the lack of the gender differences in self-construal was evident, no further analysis was conducted to explore the mediating role of self-construal in the association between gender and motivation. Overall, it appears that self-construal is not related to gender differences in motivation. Instead, gender seems to have a direct effect on motivation that is independent of self-construal in this learning context.

Discussion

This study investigated the roles of gender and self-construal in the motivation to learn English in PBL settings. The findings of the first research question concerning the association between self-construal and motivation indicate the adjustable nature of self-construal according to the learning context. Concerning identified regulation, which focuses on motivation derived from the value and importance of learning, both types of self-construal were significant predictors. However, only interdependent self-construal affected the degree of intrinsic motivation and amotivation in this learning context. Given the theoretically and empirically evidenced link between SDT autonomous motivation and independent self-construal (Kong and Ho Citation2016; Lee and Pounders Citation2019; Tanaka Citation2020), a lack of significance in independent self-construal is somewhat surprising. However, the contextual effects may explain this phenomenon. As discussed earlier, the PBL context of this study encouraged peer interactions in class. The students were frequently involved in pair and group work, practicing their presentations in class and obtaining feedback on their projects. Just as intrinsic motivation driven by enjoyment is spontaneous and in accordance with the core self (Ryan and Deci Citation2017), socially-oriented learners with high interdependent self-construal are assumed to be autonomous and congruent with their core self when enjoying peer interactions. Although autonomy and independence are the core properties of independent self-construal, as the social aspect of PBL gives rise to the autonomous state among learners with high interdependent self-construal, interdependent self-construal may override autonomy derived from independent self-construal and play a more conspicuous role in this learning context. Independent self-construal may have a more prominent impact on intrinsic motivation and amotivation in learning contexts that require solitary learning (e.g. self-directed vocabulary learning) as demonstrated by Tanaka (Citation2020), while interdependent self-construal may play a key role in learning contexts that emphasize social interaction.

The second and third research questions concerned gender differences in motivation and the role of self-construal in the relationship between gender and motivation. In line with the prior research that has demonstrated motivated and less motivated tendencies among women and men in L2 learning (Henry Citation2011; Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013; Yashima, Nishida, and Mizumoto Citation2017; You, Dörnyei, and Csizér Citation2016), the female participants tended to be more motivated toward L2 learning than the male participants, and the male students tended to be demotivated to learn in this context. Due to the lack of the involvement of self-construal in the association between gender and motivation, it is uncertain how L2 learning motivation of the two genders differs in the current study context. As suggested in prior studies (Henry Citation2011; Yashima, Nishida, and Mizumoto Citation2017), communication orientation may account for the difference. However, further studies are warranted to investigate the other possibilities.

This study demonstrated that female students and students with higher interdependent self-construal tended to be more motivated toward L2 learning, while male students and students with lower interdependent self-construal tended to be less motivated. Despite the similarity in the motivational tendencies between gender and interdependent self-construal, female and male participants did not exhibit their respective motivational tendencies due to their interdependent self-construal attributes. A lack of involvement of self-construal in the association between gender and motivation may be explained by the cultural and societal characteristics of the current study’s context. Although there are variations within the same culture, Japan, where this study was conducted, is traditionally considered to be a collectivist society (Triandis Citation1995). As collectivist cultures generally emphasize the properties of interdependent self-construal such as connectedness to others (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991), the Japanese are inclined to have interdependent self-construal rather than independent self-construal, regardless of gender. Indeed, there were no gender differences in self-construal among the participants of this study. Perhaps, interdependent self-construal may not explain gender differences in motivation in a more collectivist culture, where interdependent self-construal is emphasized and gender differences in self-construal are obscured. On the contrary, given the evidenced gender differences in self-construal in more individualistic societies (Cross and Madson Citation1997), interdependent self-construal may mediate the association between gender and motivation in this context. This is in line with Henry and Cliffordson (Citation2013), who demonstrated the mediating role of interdependent self-construal in the relationship between gender and the ideal L3 self in Sweden, which is traditionally considered to be an individualistic society (Triandis Citation1995).

Furthermore, levels of gender equality may affect how self-construal operates in gender differences in motivation. According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2020 rankings (World Economic Forum Citation2019), Japan ranked 121st among 153 countries and has high levels of gender inequality. Gender differences in motivation might have been salient in this study because traditional gender roles and marked gender inequality are still prevalent in Japan. As demonstrated in the study by Henry and Cliffordson (Citation2013), self-construal may play an influential role in the relationship between gender and motivation in a more gender-equal society, such as Sweden, which ranked 4th in the Global Gender Gap Report 2020 rankings (World Economic Forum Citation2019). On the contrary, it may play a less conspicuous role in gender differences in motivation in a less gender egalitarian society such as Japan.

Overall, as self-construal was not related to the gender differences in motivation, it does not have the power to reduce the motivational disadvantage men tend to have in PBL in the current learning context. However, self-construal has been shown to mediate how gender affects motivation in a more egalitarian and individualistic society (e.g. Henry and Cliffordson Citation2013). Identifying factors that affect self-construal may help in improvement of low motivational tendencies in men in such contexts. On the contrary, as the degree of gender equality and collectivism in a society may affect the role of self-construal in reducing the undesirable effects of gender on motivation, further studies need to be conducted in diverse contexts.

Conclusion

This study examined the impact of gender and self-construal on L2 learning motivation in PBL settings. The results highlight the advantage possessed by female students and those manifesting interdependent self-construal in promoting higher motivation in this learning context. Although the causes of gender differences in motivation remain unclear in the current study context, the findings pertaining to self-construal have several implications. First, as those with higher interdependent self-construal have socially-oriented motives for behaviors (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991), incorporating various types of peer interaction activities may boost their motivation further. Second, those with lower interdependent self-construal may have a disadvantage in L2 learning in such settings due to the incongruence between the interaction-heavy nature of the PBL learning approach and their personal values in social orientations. Although it is not feasible to tailor a teaching approach to each student’s learning preference, teachers can be creative in mitigating the negative outcomes arising from incongruences affecting learning motivation. For example, as communication orientation may change depending on the interlocutors, teachers can devise pair and group formations to promote willingness to communicate among those with lower social interaction tendencies. Further, teachers may inform them of the merits of learning through peer interaction in PBL repeatedly. Through understanding and internalizing the values, the students may be more motivated to participate in the learning activities.

Several limitations of this study should also be noted. First, as some constructs used in this study exhibited a reliability estimate of below 0.7, the results may need to be interpreted with caution. Second, the source of data for this study was self-reported questionnaires. Although the results of the analyses are reliable, several other methodological approaches (e.g. qualitative data analysis including interviews and observations) need to be combined to triangulate and support the validity of the findings in further studies. Third, the scope of the current research was limited as only a small number of variables were included in this study. SDT postulates that motivation may be internalized by satisfying the three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan and Deci Citation2017); therefore, incorporating these variables in future research may clarify the interplay among gender, self-construal, and motivation more comprehensively. Fourth, as this study employed a cross-sectional design in which data were collected at a single point of time, only a snapshot of the connections among gender, self-construal, and motivation was revealed. Employing a longitudinal design would help in understanding the temporal variability of motivation in relation to self-construal. Fifth, although self-construal represents the domain of general traits of individuals, this attribute has been reported to change with age (Takata Citation2000). As the findings may capture the characteristics of undergraduate students specifically, further research with different age groups is necessary to reveal a more thorough picture of the roles of self-construal in L2 learning.

Despite these limitations, this study has demonstrated the roles of self-construal and gender in understanding L2 learning motivation in PBL settings. The effects of independent and interdependent self-construal vary according to context. As Serafini (Citation2020) argues, further studies using the construct of self-construal are necessary with a variety of students in multiple learning, cultural, and societal contexts to gain a better understanding of the relevant influences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mitsuko Tanaka

Mitsuko Tanaka is an associate professor at Osaka University, Japan. Her research interests include individual differences in SLA and language assessment.

References

- Bentler, P., and E. Wu. 2012. EQS for Windows (Version 6.2) [Computer Software]. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc.

- Bond, T., Z. Yan, and M. Heene. 2021. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. 4th ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Byrne, B. M. 2006. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cross, S., E. Hardin, and B. Gercek-Swing. 2011. “The What, How, Why, and Where of Self-Construal.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 15 (2): 142–179. doi:10.1177/1088868310373752.

- Cross, S., and L. Madson. 1997. “Models of the Self: Self-Construals and Gender.” Psychological Bulletin 122 (1): 5–37. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2005. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Dörnyei, Z., and S. Ryan. 2015. The Psychology of the Language Learner Revisited. New York: Routledge.

- Dörnyei, Z., and E. Ushioda. 2009. “Motivation, Language Identities and the L2 Self: Future Research Directions.” In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, edited by Z. Dörnyei, and E. Ushioda, 350–356. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Field, A. 2013. Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics. London: Sage.

- Gardner, R. C. 1985. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London, UK: Edward Arnold.

- Hedge, T. 1993. “Key Concepts in ELT.” ELT Journal 47 (3): 275–277. doi:10.1093/elt/47.3.275.

- Henry, A. 2011. “Gender Differences in L2 Motivation: A Reassessment.” In Gender Gap: Causes, Experiences and Effects, edited by S. A. Davies, 81–102. New York: Nova Science.

- Henry, A., and C. Cliffordson. 2013. “Motivation, Gender, and Possible Selves.” Language Learning 63 (2): 271–295. doi:10.1111/lang.12009.

- IBM Corp. 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 24.0) [Computer Software]. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Joe, H.-K., P. Hiver, and A. H. Al-Hoorie. 2017. “Classroom Social Climate, Self-Determined Motivation, Willingness to Communicate, and Achievement: A Study of Structural Relationships in Instructed Second Language Settings.” Learning and Individual Differences 53: 133–144. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2016.11.005.

- Kashima, E., and E. Hardie. 2000. “The Development and Validation of the Relational, Individual, and Collective Self-Aspects (RIC) Scale.” Asian Journal of Social Psychology 3 (1): 19–48. doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00053.

- Kong, T., and V. Ho. 2016. “A Self-Determination Perspective of Strengths use at Work: Examining its Determinant and Performance Implications.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 11 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1004555.

- Laverick, E. K. 2019. Project-Based Learning. Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press.

- Lee, S., and K. R. Pounders. 2019. “Intrinsic Versus Extrinsic Goals: The Role of Self-Construal in Understanding Consumer Response to Goal Framing in Social Marketing.” Journal of Business Research 94: 99–112. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.039.

- Legault, L., I. Green-Demers, and L. Pelletier. 2006. “Why do High School Students Lack Motivation in the Classroom? Toward an Understanding of Academic Amotivation and the Role of Social Support.” Journal of Educational Psychology 98 (3): 567–582. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.567.

- Linacre, J. M. 2013. Winsteps (Version 3.80.0) [Computer Software]. Beaverton, OR: Winsteps.com.

- MacIntyre, P., Z. Dörnyei, R. Clément, and K. Noels. 1998. “Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2 Confidence and Affiliation.” The Modern Language Journal 82 (4): 545–562. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x.

- Markus, H., and S. Kitayama. 1991. “Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation.” Psychological Review 98 (2): 224–253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224.

- McEown, M., K. Noels, and K. Saumure. 2014. “Students’ Self-Determined and Integrative Orientations and Teachers’ Motivational Support in a Japanese as a Foreign Language Context.” System 45: 227–241. doi:10.1016/j.system.2014.06.001.

- Mercer, S. 2014. “Re-Imagining the Self as a Network of Relationship.” In The Impact of Self-Concept on Language Learning, edited by K. Csizér, and M. Magid, 51–69. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Mills, N. 2009. “A Guide du Routard Simulation: Increasing Self-Efficacy in the Standards through Project-Based Learning.” Foreign Language Annals 42 (4): 607–639. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2009.01046.x.

- Noels, K. 2001. “Learning Spanish as a Second Language: Learners’ Orientations and Perceptions of their Teachers’ Communication Style.” Language Learning 51 (1): 107–144. doi:10.1111/0023-8333.00149.

- Noels, K., R. Clément, and L. Pelletier. 1999. “Perceptions of Teachers’ Communicative Style and Students’ Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation.” Modern Language Journal 83 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1111/0026-7902.00003.

- Noels, K., R. Clément, and L. Pelletier. 2001. “Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Integrative Orientations of French Canadian Learners of English.” Canadian Modern Language Review 57: 424–442. doi:10.3138/cmlr.57.3.424.

- Noels, K. A., D. I. V. Lascano, and K. Saumure. 2019. “The Development of Self-Determination across the Language Course: Trajectories of Motivational Change and the Dynamic Interplay of Psychological Needs, Orientations, and Engagement.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41 (4): 821–851. doi:10.1017/S0272263118000189.

- Noels, K., L. Pelletier, R. Clément, and R. Vallerand. 2000. “Why are you Learning a Second Language? Motivational Orientations and Self-Determination Theory.” Language Learning 50 (1): 57–85. doi:10.1111/0023-8333.00111.

- Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., Y. Nakata, P. Parker, and R. M. Ryan. 2017. “Motivating Young Language Learners: A Longitudinal Model of Self-Determined Motivation in Elementary School Foreign Language Classes.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 49: 140–150. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.010.

- Pae, Tae-II. 2008. “Second Language Orientation and Self-Determination Theory: A Structural Analysis of the Factors Affecting Second Language Achievement.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 27: 5–27. doi:10.1177/0261927X07309509

- Ryan, R., and E. Deci. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Press.

- Serafini, E. 2020. “Further Situating Learner Possible Selves in Context: A Proposal to Replicate Henry and Cliffordson (2013) and Lasagabaster (2016).” Language Teaching 53 (2): 215–226. doi:10.1017/S0261444819000144.

- Singelis, T. 1994. “The Measurement of Independent and Interdependent Self-Construals.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20 (5): 580–591. doi:10.1177/0146167294205014.

- Slater, T., G. H. Beckett, and C. Aufderhaar. 2006. “Assessing Projects as Second Language and Content Learning.” In Project-Based Second and Foreign Language Education: Past, Present, and Future, edited by G. H. Beckett, and P. C. Miller, 241–260. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Stoller, F. 2006. “Establishing a Theoretical Foundation for Project-Based Learning in Second and Foreign Language Contexts.” In Project-Based Second and Foreign Language Education: Past, Present, and Future, edited by G. H. Beckett, and P. C. Miller, 19–40. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Tabachnick, B., and L. Fidell. 2007. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Takata, T. 2000. “On the Scale for Measuring Independent-Interdependent View of Self.” Bulletin of Research Institute of Nara University 8: 145–163.

- Takata, T. 2003. “Self-Enhancement and Self-Criticism in Japanese Culture: An Experimental Analysis.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 34 (5): 542–551. doi:10.1177/0022022103256477.

- Tanaka, M. 2013. “Examining Kanji Learning Motivation using Self-Determination Theory.” System 41 (3): 804–816. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.08.004.

- Tanaka, M. 2017. “Examining EFL Vocabulary Learning Motivation in a Demotivating Learning Environment.” System 65: 130–138. doi:10.1016/j.system.2017.01.010.

- Tanaka, M. 2020. “The role of Self-Construal in EFL Vocabulary Learning.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1515/iral-2019.0082

- Tanaka, M. 2021. “Individual Perceptions of Group Work Environment, Motivation, and Achievement.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1515/iral-2020.0183

- Triandis, H. C. 1995. Individualism and Collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Vandergrift, L. 2005. “Relationships among Motivation Orientations, Metacognitive Awareness and Proficiency in L2 Listening.” Applied Linguistics 26 (1): 70–89. doi:10.1093/applin/amh039.

- Vonkova, H., J. Jones, A. Moore, I. Altinkalp, and H. Selcuk. 2021. “A Review of Recent Research in EFL Motivation: Research Trends, Emerging Methodologies, and Diversity of Researched Populations.” System 103: 102622. doi:10.1016/j.system.2021.102622.

- Wenz, A., T. Al Baghal, and A. Gaia. 2021. “Language Proficiency among Respondents: Implications for Data Quality in a Longitudinal Face-to-Face Survey.” Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 9 (1): 73–93. doi:10.1093/jssam/smz045.

- World Economic Forum. 2019. Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf

- Yashima, T., R. Nishida, and A. Mizumoto. 2017. “Influence of Learner Beliefs and Gender on the Motivating Power of L2 Selves.” The Modern Language Journal 101 (4): 691–711. doi:10.1111/modl.12430.

- You, C., Z. Dörnyei, and K. Csizér. 2016. “Motivation, Vision, and Gender: A Survey of Learners of English in China.” Language Learning 66 (1): 94–123. doi:10.1111/lang.12140.