Abstract

The massive expenditure on UN peacekeeping missions combined with a significant commitment of personnel and infrastructure creates ‘peacekeeping economies’ within host societies. We need to understand when and how peacekeeping economies are created and the kinds of factors that mitigate their occurrence, size and impact. Previous research indicates an overall tendency of UN missions to minimize involvement in host communities’ economies, and considerable variation in the level of economic impact. Especially in insecure environments, the modalities of UN peacekeeping limit the level of economic interaction with host societies. South Sudan is a case in point. Annually about 10,000 people are employed and $1 billion on average spent on peacekeeping in South Sudan. However, at both the macro and micro levels the economic impact of peacekeeping has been overshadowed by the concurrent influx of oil revenue. Oil money has created a boom in the larger towns that dwarfs the impact of peacekeeping activities. The lack of domestic markets and skilled labour reduces opportunities for the missions, and their foreign personnel, to engage in economic transactions with South Sudanese.

Introduction

UN peacekeeping missions have, over the last two decades, been assigned ever-expanding mandates including peacebuilding and governance reforms, but they are only to a limited degree intended or able to implement programmes of social and economic change. They should instead create the space where such changes can take place. Yet separate from the question of facilitating overall developmental change is the social and economic impact of mission activities. Much recent research on peacekeeping and peacebuilding has been preoccupied with how to gauge the effect that peacekeepers and peacekeeping missions have on ‘the local’.Footnote1 While ethnographic methods have increasingly been used to address this question, a more traditional economic study (investigating eight peacekeeping missions) has shown that missions have little macro-economic impact on national economies (Carnahan, Durch, and Gilmore Citation2006). Only a small fraction of their budgets—as little as 5%—is spent in host countries, and most of peacekeepers’ pay is wired to their home bank accounts; little is spent locally.

Peacekeeping economies are nevertheless ubiquitous in most countries where international peacekeepers are present. The presence of peacekeeping operations inevitably spawns a plethora of micro-level transactions. By studying these transactions, scholars may shed light on the nature and implications of relations between individual peacekeepers and the host population. This approach conceptualizes the economies generated by the activities and demands of peacekeepers as fields of political and social interaction—meeting places between cultures—that have specific sets of players and rules. Identifying the mechanisms and modalities that govern transactions and interactions between peacekeepers and locals—and when and where these take place—helps us to understand whether (or which) modalities of peacekeeping operations have negative, unintended consequences for certain segments of host societies (Dzinesa Citation2004; Zanotti Citation2008; Büscher and Vlassenroot Citation2010; Jennings Citation2014), and conversely where (or how) these operations may have a positive impact. Concurrently, it is necessary to take a step back to ask: when and where do such peacekeeping economies occur, and what determines their extent as spatial and temporal phenomena? Can we take for granted any connections, even transactional ones, between the host society and the missions and their personnel? And where the connections that do exist are highly circumscribed or are overshadowed by other, more dominant economic arrangements and revenue sources, how can peacekeeping economies be studied?

This article proposes preliminary answers to these questions through an investigation of the stunted peacekeeping economy in South Sudan in the period 2005–12, corresponding to the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) (2005–11) and the first years of its successor, the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS).Footnote2 The article explores ways in which UNMIS and UNMISS have interacted with the national and local (Juba-based) economy, both on the institutional level and as a collective of individuals. South Sudan offers an interesting context for the study of peacekeeping economies: here the peacekeeping operations have been large, long and costly. By association with the much publicized peace agreement in 2005 and South Sudan's subsequent secession in 2011 the operations have been vested with considerable international prestige. Nevertheless, peacekeeping economies in South Sudan, at least up to December 2013, have been surprisingly small. This anomaly is related to restrictive security procedures, and a ‘bunker mentality’ that reduces the level of economic interaction with the host society (Duffield Citation2010). Interactions with the host population is further limited by missions’ tendency to favour professional, formal, large-scale, and often foreign economic actors when they must procure things locally (Jennings Citation2013). Meanwhile, South Sudan has, until recently, been an oil-rich rentier economy, wherein the revenues from oil hugely overshadow the economic effect of peacekeeping activities, and provide a central focus and source of income for elites, government employees (civil and military) and their networks of clients. The oil economy in Juba and other larger towns are characterized by high levels of import and consumption, rather than investment and development, which interestingly mirror those of peacekeeping economies elsewhere in Africa. While focusing specifically on South Sudan, this investigation has general applicability by providing insight into how and where peacekeeping economies may develop, and factors determining their extent.

Peacekeeping in South Sudan: Struggling against Irrelevance

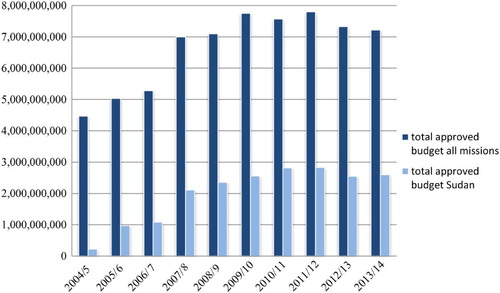

UN peacekeeping missions in Sudan and South Sudan over the last decade have been expensive, and they continue to be vested with considerable political responsibility. The two countries currently host three missions: UNMISS; the hybrid UN and AU Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), since 2007; and the much smaller UN Interim Security Force in Abyei (UNISFA), since 2011, which is in essence a mechanism for funding the Ethiopian stabilization force in Abyei. Conversely, UNMISS and UNAMID are large missions with a wide peacebuilding mandate, and are regarded as main pillars of the international effort to maintain stability in the two countries. The overall cost of peacekeeping in the two countries is formidable, and in some years has represented about a third of the funds spent on peacekeeping globally (see ).Footnote3 In terms of accumulated expenditure, peacekeeping in the two Sudans (approximately $20 billionFootnote4 since 2004) has been by far the most costly peace intervention of the last decade.Footnote5 The combined budgets of the UNMIS and UNMISS for the period 2005–13 are close to $10 billion. The performance of these missions is therefore an indicator of the state of peacekeeping in general. Continued civil war in Darfur and the outbreak of a new conflict in South Sudan in December 2013 open up broader questions about the purpose and effectiveness of the operations.

Figure 1. Cost of UNDPKO missions in Sudan and South Sudan as a share of total UNDPKO missions’ budget.

The initial UNMIS operation's raison d’être was the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the government of Sudan (represented by the ruling National Congress Party or NCP) and the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). The CPA was negotiated between June 2002 and December 2004 and signed on 9 January 2005, and made extensive concessions to the rebels. These included a ceasefire agreement and various disarmament provisions, as well as withdrawal of the Sudanese armed forces from the South. The SPLM/A wanted a peacekeeping mission in order to guarantee implementation of the agreement (van der Lijn Citation2010, 42).

Because of its initial design and the political situation at the time (2005), UNMIS was not intended to be a major provider of security or facilitator of the international presence in South Sudan (van der Lijn Citation2010, 48–49; see also Arenas-García Citation2010; Hemmer Citation2013; Lie and de Carvalho Citation2010). Indeed, the mission was neither the vanguard of international engagement there, nor necessary for it. The presence of a UN military contingent was first and foremost symbolic—a gesture demonstrating the interest and commitment of the international community, and giving the UN greater weight in dealing with Sudanese and South Sudanese parties to the peace agreement.

The fashion of the time dictated a broad mandate for UNMIS, which included protection of civilians, peacebuilding and democratization (Bellamy and Williams Citation2010; UNDPKO Citation2009). However, the mission lacked the capacity to cover an area the size of France, and the government in Juba considered the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) capable of maintaining control (Johnson Citation2012; van der Lijn Citation2010, 41). But when, after 2005, the SPLA initiated a programme of restructuring and professionalism (Munive Citation2014), its reduced presence in the countryside left a security vacuum that neither UNMIS nor a dysfunctional national police force could fill.Footnote6 Increasing local violence and insecurity spawned vigilantism and arms-keeping among a population already militarized and accustomed to a very light government presence (see Rolandsen Citation2009).

In subsequent years, UNMIS's political results were mixed. It intervened in Malakal in Citation2006 and 2008 when former militia groups, newly absorbed into the Sudanese armed forces, clashed with SPLA soldiers. But despite having played an active role in preventing escalation of violence between the parties after skirmishes in May 2008, UNMIS did little to stop government forces from reoccupying Abyei in May 2011. Nor did it contribute to a peaceful solution in June, when civil war broke out in South Kordofan (Johnson Citation2012).

Despite a mandate to protect civilians, UNMIS demonstrated little will and limited capacity to deal with escalating local violence in rural areas, which might have killed as many as 10,000 people between 2005 and 2011. Its contingents were mainly meant to protect military observers and civilian staff—not to control often-armed civilians, who could in a matter of days mobilize in groups of several thousand. Ambitious changes were made in 2011, with a Chapter VII mandate to protect civilians and the goal of a broader presence on the ground (United Nations Security Council Citation2011). But an increase in assigned activities did not result in cumulative improvement of security in the countryside.

‘UNMIS’ became ‘UNMISS’ following South Sudan's independence on 9 July 2011. Restricted to South Sudan, the current mission has been presented as the spearhead of a new breed of UN operations with an explicit peacebuilding mandate (da Costa and Karlsrud Citation2012, 58). This ambition was foreclosed in December 2013 with the outbreak of a new civil war. Within hours of the first shots, people in Juba, the capital, began to arrive at UNMISS compounds in search of protection. Over the next few months, compounds guarded by the UNMISS admitted more than 100,000 people in Juba and the three states (Unity, Upper Nile and Jonglei) engulfed by the war (see Rolandsen et al. Citation2015). In response to the new conflict and the increased responsibilities of the mission, on 27 May 2014 the UN Security Council revised the mandate and assigned more troops (United Nations Security Council Citation2014). Ironically, the outbreak of this conflict resulted in larger budgets and new tasks for the UNMISS, which—when there had still been a peace to be kept—had been subjected to accusations of inefficiency and irrelevance. Such modest results from the period 2005–12 prompt the question of whether these massive missions have had many other kinds of impact on South Sudanese society beyond offering some humanitarian assistance.

South Sudan's Oil Economy

Peacekeeping operations’ interaction with host economies is partly determined by the size and diversity of those economies (Carnahan, Durch, and Gilmore Citation2006). Establishment of the peacekeeping mission coincided with the influx of oil revenue to the autonomous government in South Sudan. Much of that revenue, in the billions of dollars, was at the disposal of South Sudanese and spent inside the country. But instead of having an economy of investment and development, South Sudan has one of import and consumption (e.g. Munive Citation2014). The demand of South Sudanese elites and their dependants for imported consumer goods, luxury accommodation and expensive cars completely overshadowed the domestic expenditure of the missions. Skilled labour, traders, and entrepreneurs, largely from neighbouring countries, imported goods, offered services, and built shops, gas stations, hotels and restaurants. The economies that sprang up in the larger towns—Juba foremost—have many of the same characteristics of peacekeeping economies, but they are driven first and foremost by oil money, not peacekeeping activities. The oil economy has dwarfed the economic impact of the UN missions even around their own bases.

South Sudan is still one of the poorest countries in Africa, with a large share of its estimated 10.9 million inhabitants living below the official poverty line (World Bank Citation2013). Except for an expanding mobile phone network, South Sudan has almost no modern infrastructure. The Juba–Nimule road to Uganda is the only paved road outside the capital, and many other roads are difficult to negotiate during the rainy season (May–October). The country depends on diesel generators for electricity (US Department of State Citation2013). As a foreign aid worker notes, ‘this place makes Afghanistan look developed’ (”A New Country” Citation2013). Beyond this, we know little about South Sudan's economy; statistics are impressionistic only, because the government and the international community lack any monitoring capacity. The formal economy revolves around the government's oil revenue, while the private sector is largely informal. Moreover, because of war and stagnation, a considerable share of South Sudan's economy is based on subsistent production and barter (Muvawala and Mugisha Citation2014). Recent years’ austerity measures and attempts to increase revenues from taxation of non-oil sectors have had little impact, up from 2% of overall income in 2011 to 4% in 2012 (Munive Citation2014, 340). By early 2015, as a consequence of reduced oil production and plummeting oil prices, it was evident that South Sudan was in deep economic crisis.

Juba has two economies: one boosted by oil revenues and run by wealthy South Sudanese businessmen and regional entrepreneurs, the other significantly smaller yet encompassing the majority of the population (Martin and Mosel Citation2011, 13; see also Aning and Edu-Afful Citation2013 on dual economies). After the peace agreement in 2005, people from rural areas and returning refugees flocked to Juba for access to medical treatment, education and modern infrastructure (Martin and Mosel Citation2011). This sudden and uncontrolled growth resulted in a large population without the financial resources to buy land and struggling with the high cost of living (Grant and Thompson Citation2013). Many town-dwellers rely on foreign remittances and help from relatives, while the majority of waged workers are employed by the government. Since December 2013, war has increased internal migration, and hundreds of thousands have sought refuge in neighbouring countries. The reduction of oil revenue has led to arrears in government salaries, further shrinking the monetary sector of the economy. Big international companies are reluctant to make long-term investments in South Sudan because of the lack of a legal framework, the high level of corruption, and insecurity generated by conflict (Martin and Mosel Citation2011, 13). An exception might be land. According to a report by David Deng (Citation2011), investors from the USA, India, China, Malaysia and Turkey, as well as Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda, have been involved in a massive land grab. Deng states that ‘from 2007 and 2010, foreign companies, governments and individuals have sought or acquired at least 2.64 million hectares (26,400 [sic] km2) of land for projects in the agriculture, biofuel and forestry sectors’ (Citation2011, 8).

Since the 1980s, oil has played a central role in the domestic politics, economy and international relations of Sudan. The sharing of oil revenue was a key issue in the negotiation of the 2005 peace agreement. Despite a subsequent (September 2012) deal, oil is still a major source of tension between the two states (Jumbert and Rolandsen Citation2013). South Sudan's formal economy is the most oil-dependent in the world. Between 2005 and 2011, oil accounted for 99% of the government's revenue and approximately 60% of measured GDP ().Footnote7 Oil has also attracted foreign investors aiming for short-term profit. Along with Western companies, Chinese, Indian and Malaysian businesses compete for their share of South Sudanese oil (Shankleman Citation2011; Patey Citation2010, 622–625). Recent instability and political unpredictability have, however, curbed some of the initial interest in the oil sector. The rest of the South Sudanese economy remains undiversified and dependent on low productivity ‘unpaid agriculture and pastoralists work’ (World Bank Citation2013).

Table 1. Oil revenues as percentage of total government revenues

According to the Ministry of Finance (reproduced in Shankleman Citation2011, 10), during the period 2005–11 annual oil revenue ranged between $750 million and $3 billion.Footnote8 Thanks to this revenue, South Sudan, then an autonomous area of Sudan, had a higher income than many other countries facing reconstruction after civil wars (World Bank Citation2013). It is difficult to estimate the exact amount of oil revenue spent inside South Sudan because of low accountability and the assumed high level of corruption (Mores Citation2013). Still, most of the money paid in salaries to soldiers and civil servants seems to have circulated inside South Sudan. According to a World Bank report, oil revenue enabled the government after independence to sustain public expenditure averaging $300 per person, a much higher level than in neighbouring countries (Adiebo, Bandiera, and Zacchia Citation2013).

To fully appreciate the impact of oil revenue on South Sudanese society, it is necessary to consider the political economy of neo-patrimonialism (Chabal and Daloz Citation1999). Foreign observers often comment on how South Sudanese in general experience no benefits from the government's oil revenue. And certainly little has been done in terms of state-initiated socio-economic development; a considerable amount of oil money is likely to have been siphoned off to foreign bank accounts. But an important share has certainly been spent on political stability and maintenance of patronage networks. As summarized by Alex de Waal (Citation2014), the political leadership of South Sudan has since 2005 used oil money to buy off and co-opt potential spoilers of the CPA. At least until recently, this has had a trickle-down effect. Political opponents of the government have received official positions from which they can enrich themselves and maintain their own patronage networks. Former members of militias and other armed groups have been loosely incorporated into the army, and both officers and other ranks have received generous salaries and benefits. Typically, one soldier or civil servant may be the sole provider and patron for an extended family. Thus, oil revenue circulates within the South Sudanese economy, which has attracted crowds of foreign traders and entrepreneurs offering goods, services and accommodation to the different layers of the patron–client networks, from Chinese plastic chairs to high-end cars (Stockman Citation2013). A similar, but smaller, trickle-down effect is observable in the 1,600–1,700 South Sudanese employed within UNMISS (see below). This combination of an undiversified subsistent economy awash with a sudden injection of oil revenue impacted on the ways in which the UN mission and its personnel have interacted with South Sudanese in general.

First, however, it is important to note the recent reversal in fortunes, largely self-inflicted, that has led to renewed conflict. In particular, the diminished flow of money to the neo-patrimonial economy was an important factor behind the outbreak of the new civil war in December 2013 (de Waal Citation2014). When unilaterally deciding to shut down oil production in January 2012, South Sudanese leaders expected government reserves and borrowing to carry them through the hiatus. At first this strategy seemed to work, but the shutdown lasted longer than expected and, in early 2013, the country faced a fiscal crisis. Partly because of this and partly because of political deadlock, powerful factions were suddenly cut off from government positions and from the revenue stream. Increased political tension ensued, and the opportunity cost of going back to war was considerably reduced (see Rolandsen Citation2015).

UN Missions’ Interaction with South Sudan's Economy

Opportunities for economic transactions depend in part on the nature of the economy where a peace operation is inserted: a well-resourced mission within a relatively advanced monetary economy might have a higher level of interaction than one operating in a poor and undiversified economy (Aning and Edu-Afful Citation2013, 21). South Sudan definitely belongs to the latter category. Also, extreme neo-patrimonialism and an unregulated economy add to the difficulty for a bureaucratic organization like the UN to do business with South Sudanese. The mission conducts most of its procurement abroad and, when soliciting contracts for activities inside the country, it relies mainly on foreign contractors. Almost everything the peacekeeping missions in South Sudan need arrives from abroad by plane or in containers transported on trucks or barges.Footnote9 South Sudanese have little contact with UNMIS and UNMISS personnel. While all economic activity leaves a footprint, it is significantly lighter when neither seller nor buyer is South Sudanese.

This economic bypass resonates with Mark Duffield's (Citation2010, 475) observation that UN intervention is ‘bunkerized’. He cites Sudan, which at that time was still united, as an example of the way in which the international aid community insulates itself from host societies. His metaphor for foreign aid compounds in South Sudan is an ‘archipelago’, into which access is restricted and hedged with security controls (Duffield Citation2010, 477; Henry Citation2013). An aspect of this phenomenon is arguably to avoid economic interaction with the host economy; such interaction in the context of a murky and unregulated economy might lead to allegations of distorting local markets or mismanagement of funds. This tendency also constrains interaction between locals and individual peacekeepers.

Bearing these limitations in mind, three points of interaction have been identified: individual spending of personal allowances, salaries paid to national staff, and local procurement (Carnahan, Durch, and Gilmore Citation2006, 16). Some other mission activities, such as the so-called Quick Impact Projects (QIPs) and road maintenance, may also generate economic interaction. Here we will first focus on the opportunities of individual peacekeepers to interact with the South Sudanese economy; then how and when mission activities in general may be relevant for the economy of South Sudanese.

Peacekeeping Staff's Individual Interaction with the South Sudanese Economy

Peacekeeping economies might materialize as a consequence of foreign personnel interacting with the host economy or when South Sudanese are employed by the mission. We distinguish several categories of personnel and their respective opportunities (and desire) to interact with the host economy. The vast majority of personnel are regular soldiers (see ). They are for most intents and purposes insulated from the host economy. It is therefore the much smaller numbers of military officers, police, civilian staff and South Sudanese employees who for the most part conduct economic transactions within the host economy. The degree and type of interaction also depends on where peacekeepers are posted: in the larger urban centres there are more opportunities to engage in economic transactions than in mission outposts or in smaller towns.Footnote10 Temporal difference may also be observed: during the period from 2008 to 2012 the offer of goods in shops and markets was more diverse and accommodation was to greater degree available outside mission compounds when compared to earlier years and the subsequent period of civil war (from January 2014).

Table 2. UNMIS/UNMISS staff by category, 2004–2014

During the UNMIS period (2005–11), military personnel allocated to force protection functions constituted about 80% of the foreign staff. These were regular soldiers mainly from India, Bangladesh, Egypt, Kenya and Pakistan (UNMIS Citation2006). They were barracked within designated, fenced and guarded UNMIS compounds. Military contingents are expected to be equipped by their countries of origin. Even food is brought from abroad. Hence, members of military contingents have practically no incentive, and limited opportunity, for social or other interaction with South Sudanese.

Military observers, military staff, police, civilian staff and UN volunteers constitute less than 20% of the foreign staff, but, unlike contingent military personnel, these have considerable opportunity to interact with the host population and South Sudanese economy. Still, they have little incentive to do so. UN compounds are comparable to small towns and usually provide all that the staff need in terms of goods and services. The main South Sudanese towns do have bars and restaurants catering to rich locals and to foreigners in general, and these attract mission personnel; this is the main source of economic interaction between mission personnel and locals.

There are also spatial obstacles to economic interaction between these personnel and South Sudanese. Peacekeeping compounds are in most cases located outside the towns; curfews and other rules restrict movement between compounds and town centres. In consequence, most staff eat at a compound cafeteria and buy groceries from the post's shop. In some cases problems have arisen in supplying the shops, but local markets do not serve as a substitute: mission personnel go without (e.g. fresh vegetables) or the mission organizes special deliveries. In towns outside Juba, goods at the local market of interest to the foreign personnel were quite limited. One team site leader in Yambio explained that he spent US$600 per month (150 per week) on accommodation and food at the UNICEF compound. At the compound, there was an all-inclusive deal (also washing included). He spent hardly any money inside Yambio. During his time in Yambio, he would occasionally buy goods from the PX in Juba (international UNMIS store) or ask people to buy things for him. He would on average spend US$50 per month on these purchases.Footnote11

Following the outbreak of war, several of the main towns were looted and destroyed, and for security and other reasons restrictions on movement have become even stricter.

Interviews with foreign former UNMIS staff indicate that the mission discouraged them from ‘fraternization’ with South Sudanese.Footnote12 Although this policy was intended to curtail sexual interaction, it tended to be interpreted more broadly as encompassing all kinds of social contact unrelated to mission activities. Many peacekeepers have in any case little motivation for interacting with South Sudanese, and find it convenient to spend their free time with other foreigners.Footnote13 Mission budgets moreover include funds for providing, within the compounds, recreational facilities as ‘an essential part of ensuring a healthy working, living and recreational environment for all categories of staff serving in peacekeeping missions’ (UN OIOS Citation2009, 6). UNMIS spent $300,000 on gym and sports equipment for the fiscal year 2008–9 (UN OIOS Citation2009, 4). The peacekeepers’ compounds usually have a library too, and a TV/game room. A 2009 UN audit explains that, for security reasons, non-contingent staff travelling on business within the area of operation must stay in UNMIS-provided accommodation (compounds, guesthouses, hotels, etc.) (UN OIOS Citation2009, 1).Footnote14

In consequence, the fortified compound is ‘a place of refuge and consumption’ where the walls and razor-wire fence ‘demarcate an inner zone of normality and civilization’ (Duffield Citation2010, 468). UNMISS was expected to follow a different tack, with more openness and interaction with South Sudanese society as a stated goal. But some peacekeepers have claimed that the UNMISS security requirements were ‘worse than’ those ‘under the UNMIS’, with additional security restrictions and risk aversion (Hemmer Citation2013, 6; da Costa and Karlsrud Citation2012, 59–60).

UN employment of South Sudanese creates spaces of exchange, and their salaries may constitute the peacekeeping operations’ most significant contribution to the host economy. But that effect should not be exaggerated; locals earn less than foreign staff and are employed mostly as guards, cleaners, cooks, drivers, mechanics, and other low-paying jobs. It appears, moreover, that the missions struggle to fill those positions. Part of the explanation for the recruitment problem is that skilled workers prefer government or private employment. Until the recent crisis, government positions were coveted for their long-term security and other advantages, while private enterprises, particularly oil companies, pay better than the UN. To deal with this problem, the peacekeeping missions have employed workers from neighbouring countries on a short-term basis (United Nations Security Council Citation2005, 16; Citation2007, 13–14).

Seen as a whole, the South Sudanese economy holds little interest and few opportunities for foreign staff. For those personnel who might seek services, accommodation and entertainment outside the UN compounds, there is little on offer. Juba has been an exception, but even there self-sufficiency has been the mission's goal. The tendency to bypass South Sudanese and interact with other foreigners is evident in all relevant sectors. As in the Middle Eastern oil countries, the presence of a large foreign labour force has become a socio-political challenge; many South Sudanese in urban areas resent the presence of Eritreans, Ethiopians, Kenyans and Ugandans, not to mention northern Sudanese. It appears that many of the foreign workers lost their jobs and left after the economic contraction that followed the outbreak of civil war in 2013. Further research is needed to determine what impact this may have had on mission employment.Footnote15

Peacekeeping Economies Created by Official Mission Activities

Official UN mission activities create opportunities for economic interaction between peacekeepers and South Sudanese. Procurement of goods and services is important in this regard, as are QIPs and, more indirectly, mission-initiated infrastructure development.

During the period 2001–10—before Sudan was broken up—the country's economy grew rapidly because of oil production. Khartoum became a boom town offering a well-developed import infrastructure. Within an expanding private sector, there was a plethora of companies and entrepreneurs offering goods and equipment to the UN missions and their headquarters. As explained above, the situation in South Sudan was different: there was almost no infrastructure or domestic private sector when a peace was signed in 2005. In the following years oil revenue created a bubble economy in Juba, but South Sudanese traders still lacked the capacity to cater to the UN mission.

UN procurement in goods and services in Sudan increased from $57.7 million in 2005 to $269.6 million in 2010 (UN Procurement Division Citation2015). These amounts were significant within the national context, but were even so a small share of total UN spending on assistance to Sudan. Considering the nature of its economy during this period, procurement in South Sudan must have been slight at best. Although UNMIS activities for the most part took place there, politics dictated that the mission operate out of the national capital, Khartoum—400 km from South Sudan's northernmost border and more than 1,000 km from Juba.

After independence, procurement inside South Sudan increased rapidly, but in terms of the total budget this still accounted for a small proportion—in 2013 some $133.9 million, or 0.8% of the global peacekeeping budget (UNOPS Citation2014, 38). Both in Sudan and South Sudan, most procurement is related to services; in 2013 UN agencies spent only $16.4 million (UNOPS Citation2014, 38) on goods in South Sudan. This indicates how peacekeeping missions handle procurement, which is based on organizational blueprints and standardized systems. Furthermore, a large share of the missions’ non-salary cost is related to transportation—aviation, vehicles and fuel—largely procured abroad (ACABQ Citation2013, 3).Footnote16 The system is assumed to be cost-effective and transparent, but one consequence—for better or worse—is that economic interaction with the host country remains minimal.

Local procurement in South Sudan is also limited by the lack of markets and transportation infrastructure. But even when local procurement takes place, South Sudanese tend to be excluded. As explained above, the oil economy has brought an influx of traders and entrepreneurs—in particular from Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia—into Juba and the other larger towns. Mechanisms implemented by the United Nations to prevent fraud and abuse also limit the ability of the peacekeeping mission to act independently. For example, owing to the excessive red tape required by New York, it took months for UNMIS to donate a few tents to a local community in Abyei (Johnson Citation2012, 651).

There is an inherent ambiguity in the discussion of mission-initiated interaction with host economies. While the UN needs to display cost-efficiency and transparency in its procurement procedures, member countries also want what they regard as a fair share of contracts. It is thus important for the UN to document how much it buys from various member countries. Procurement in host countries is seen as beneficial, but the UN is criticized for creating artificial demand and unsustainable economies in host countries. However, evidence presented above from Sudan and South Sudan suggests that the level of procurement in these countries can be sustained within an expanding oil economy. The ongoing civil war might also change the current balance of economic power in South Sudan as the oil sector shrinks, the UN operation expands, and the internally displaced population increases the mission's interaction with new segments of the host population.

Another possible form of economic interaction with locals is the Quick Impact Projects. Since 2000, it has been UN policy to implement ‘small, visible and rapidly implementable projects intended to establish and build confidence of the local population in the Mission and the peace process’ (UN OIOS Citation2010, 6). For this purpose, UNMIS and UNMISS have received annual allocations between $178,000 (2008/9) and $2 million (2006/7) (UN OIOS Citation2008a, 6). The maximum budget for any single project was $25,000 (UN OIOS Citation2008a, 7). These QIPs thus claimed only a tiny fraction of official budgets, and could not by themselves create a local peacekeeping economy. But, when considering that almost all of the rest of the missions’ funds were spent outside South Sudan while a considerable share of the QIP money was supposed to be spent in the smaller towns and rural areas, these projects could have been a significant source of economic interaction between the missions and ordinary South Sudanese.

The QIPs have, however, neither served their stated purpose nor had any significant unintended local economic impact. The projects in South Sudan have been ill-conceived, and little effort has been invested in planning and implementing them (UN OIOS Citation2008a, 8). Instead, interested military observers and police personnel took responsibility for administering QIPs as an extra duty or a hobby.Footnote17 This resulted in random follow-up; the 2008 audit report is rife with examples of badly planned and poorly executed projects. For example, after a bus shed was constructed in one of Juba's markets at the cost of more than $14,000 (UN OIOS Citation2008a, 8), the bus stop moved but of course the shed, built of corrugated iron sheets and concrete, remained. After a community resource centre was approved in 2007 for Kwajok, in Warrap, the local government director in charge withdrew more than $5,000, but nothing was done and the whereabouts of the funds remained a mystery as of late 2008 (UN OIOS Citation2008a, 9).

South Sudanese had little opportunity to access QIP funds because UN regulations required that funds be transferred to a bank account. At least up to 2008, South Sudan had practically no banking system that could facilitate this, and various kinds of problems and delays ensued. The audit report explains that some projects stalled because implementers could not withdraw money supposedly transferred to local branches (UN OIOS Citation2008a, 10). Such requirements benefit transnational operations with bank accounts in neighbouring countries, which were normal for foreign businessmen and, in some cases, well-connected and resourceful southerners.

Finally, peacekeeping missions’ construction and repair of roads might generate economic activity within host societies. Donors occasionally provide equipment for maintenance of main roads. The contribution of UNMIS and UNMISS, however, was slight compared to work carried out by regional contractors and the World Food Programme. Road improvement has focused on mission needs and—based on observations around various team sites—there seems to be no economic activity created by road construction or local procurement.Footnote18 Again South Sudanese have been bypassed; an audit revealed that UNMIS did not use local contractors for road maintenance because they were too costly or, in many cases, there were none (UN OIOS Citation2008b, 3). Of the roads maintained by UNMIS, those connecting HQs to main supply routes and team sites were prioritized. In the first two years, the mission built only two bridges on the section of road between Juba and Yei, and one of them, at Kulipapa, collapsed less than a year after it was built. Lack of adequate building material was reportedly the reason for the collapse (UN OIOS Citation2008b, 5–6).

Conclusion

We have seen that, although the budgets of UNMIS and UNMISS are large, little is spent inside South Sudan. The opportunity for economic interaction between South Sudanese and the mission and its personnel is severely restricted. Until recently the enclaves of peacekeeping economies in South Sudan have emerged within the larger unproductive, import-focused consumption economy created by the influx of oil revenue. Although the missions and their employees do spend money inside South Sudan, their counterparts are often foreign businessmen. The consequence is a set of economic practices which tend to bypass South Sudanese and the national economy. It is mostly South Sudanese employed as staff who are drawn into the archipelagic peacekeeping business. Although the policy of segregation—of keeping the host society at arm's length—is a more general trend, the combination of insecurity and a largely subsistent economy makes this tendency more pronounced in South Sudan than it might be elsewhere.

Mission self-sufficiency makes sense from a narrow perspective of security and efficiency: exposing a mission to the often unpredictable and informal economy of a post-war setting could not only hinder the effectiveness of the mission, but also put its personnel at risk when there is no reliable supply of food, fuel and health services. Still, by involvement in, or at least contact with, the everyday lives of the local population, peacebuilding enhances its potential to succeed and to be viewed as important by the intended beneficiaries. This is especially so in places such as South Sudan, where economic activities at the grassroots level largely take place within the informal and subsistent sector. A consequence of peacekeepers staying aloof and disengaged is their irrelevance and alienation.

The new civil war in South Sudan changes parameters regulating relations between peacekeepers and the host economy. Increased insecurity, a cooling down of the economy and a contraction of the private sector further reduce the opportunity for the mission to interact with the South Sudanese economy. But while other economic actors withdraw, UNMISS is increasing its presence. This development might imply that the mission's relative economic importance will grow, as observed in comparative cases elsewhere in Africa (e.g. Liberia and DRC). Although escalating violence and a general state of insecurity result in additional restrictions on mission personnel's interaction with South Sudanese, the presence of more than 100,000 refugees within UNMISS compounds or newly created UNMISS-protected sites suggests that new types of economic transaction might take place. Finally, in an increasingly polarized South Sudan, the economic patronage generated by employment of national staff might become more difficult for the UNMISS to handle. Within divided communities where access to employment has been significantly reduced, the hiring of national staff might prove a political liability, and even a security risk for UNMISS. Thus, in the years to come it will be necessary to systematically research the peacekeeping economies of South Sudan.

Acknowledgements

A preliminary version of this article was presented at the 5th European Conference on African Studies, Lisbon, 29 June 2013. Julie Oberting, Fanny Nicolaisen, Daniel Blocq and Kjetil Daatland have in various capacities assisted in collection of data for the project. William Reno, Kristin B. Sandvik and the RCN project group led by Morten Bøås and Kathleen Jennings provided valuable advice and suggestions, but the author is still solely responsible for the final product.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (RCN) under the NORGLOBAL programme [grant number 207757].

Notes on Contributor

Øystein H. Rolandsen is a Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and an area specialist for East Africa and the Horn of Africa. He holds a PhD in History and has published broadly on issues related to conflict dynamics and peacebuilding. ([email protected])

ORCID

Øystein H. Rolandsen http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5298-9266

Notes

1 See a short overview of this literature in Jennings and Bøås (Citation2015).

2 The research for the article is based on analysis of mission-related documentation, observation in the field since 2006, and by conversations with personnel of the UN mission in Sudan (UNMIS) and the UN mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). In mid-2013 five former UNMIS officers were approached individually and replied to a list of open ended questions. Below these are referred to as Respondents 01-05.

3 UNDPKO, Peacekeeping fact sheets available from: http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/resources/statistics/factsheet.shtml

4 All references to currency in this article are expressed in US dollars.

5 Estimates based on United Nations annual budget and expenditure reports to the General Assembly. In comparison, the costs of UN missions in Haiti (MINUSTAH) totalled US$3.9 billion and the UN missions in DR Congo (MONUC and MONUSCO) totalled US$8 billion between 2005 and 2013. These figures are calculated based on the Annual Review of Global Peace Operations 2006–13.

6 As part of the peace agreement the parties formed joint integrated units, which were also supposed to contribute towards domestic security, but these proved to be largely dysfunctional.

7 Estimation based on data in the Government of Southern Sudan Annual Budget (Ministry of Finance & Economic Planning Citation2014).

8 It is difficult to find accurate and reliable figures for the size of South Sudan's oil revenue and sources are contradictory, but we know that the revenue was in the billions and that it fluctuated considerably.

9 Observation in the field and conversation with UNMIS and UNMISS personnel.

10 Except sodas, Raga had practically nothing to offer a UNMIS military observer, respondent 01, former UNMIS officer.

11 Respondent 04, former UNMIS officer.

12 Respondent 02, former UNMIS officer; see also correspondence with UN management, September 2014.

13 Observation in the field and conversation with UNMIS and UNMISS personnel.

14 For that purpose, the mission built 1,653 housing units in sectorial headquarters, in Khartoum and El Obeid (UN OIOS Citation2010).

15 During 2015 a team of PRIO researchers led by the present author conducts research funded by the Norwegian MFA on transnational transaction and economic impact of the current civil war in South Sudan.

16 Observation based on UNMIS and UNMISS budget performance reported to the United Nations General Assembly.

17 Respondent 03 UNMIS officer; see also Respondent 05, UNMIS officer; UN OIOS (Citation2008a).

18 Ø. H. Rolandsen, field notes 2006–8 from Aweil, Yei, Torit, Bentiu, Bor and Rumbek.

References

- Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions (ACABQ). 2013. Budget Performance for the Period from 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012 and Proposed Budget for the Period from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014 of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan. A/67/780/Add.17. United Nations. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/67/780/Add.17

- Adiebo, Kimo, Luca Bandiera, and Paolo Zacchia. 2013. “Public Expenditures in South Sudan: Are They Delivering.” The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/02/17682880/public-expenditures-south-sudan-delivering

- Aning, Kwesi, and Fiifi Edu-Afful. 2013. “Unintended Impacts and the Gendered Consequences of Peacekeeping Economies in Liberia.” International Peacekeeping 20 (1): 17–32. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2013.761828

- Arenas-García, Nahuel. 2010. “The UNMIS in South Sudan: Challenges and Dilemmas.” Institute of Studies on Conflicts and Humanitarian Action, Document no. 5. http://iecah.org/web/images/stories/publicaciones/documentos/descargas/documento5_en.pdf

- Bellamy, Alex J., and Paul Williams. 2010. Understanding Peacekeeping. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Büscher, Karen, and Koen Vlassenroot. 2010. “Humanitarian Presence and Urban Development: New Opportunities and Contrasts in Goma, DRC.” Disasters 34 (2): S256–S273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01157.x

- Carnahan, Michael, William J. Durch, and Scott Gilmore. 2006. Economic Impact of Peacekeeping: Final Report. United Nations, Peacekeeping Best Practices Unit. http://www.peacekeepingresourcehub.unlb.org/PBPS/Library/EIP_FINAL_Report_March20_2006doc.pdf

- Chabal, Patrick, and Jean-Pascal Daloz. 1999. Africa Works: Disorder as Political Instrument. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Da Costa, Diana Felix, and John Karlsrud. 2012. “Contextualising Liberal Peacebuilding for Local Circumstances: UNMISS and Local Peacebuilding in South Sudan.” Journal of Peacebuilding and Development 7 (2): 53–66. doi:10.1080/15423166.2012.743814 doi: 10.1080/15423166.2012.743814

- Deng, David K. 2011. The New Frontier: A Baseline Survey of Large-Scale Land-Based Investment in Southern Sudan. Oslo: Norwegian People's Aid. http://www.rtfn-watch.org/uploads/media/new_frontier_large-scale_land_grab_sout_sudan.pdf

- De Waal, Alex. 2014. “When Kleptocracy Becomes Insolvent: Brute Causes of the Civil War in South Sudan.” African Affairs 113 (452): 347–369. doi:10.1093/afraf/adu028 doi: 10.1093/afraf/adu028

- Duffield, M. 2010. “Risk-Management and the Fortified Aid Compound: Everyday Life in Post-Interventionary Society.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 4 (4): 453–474. doi: 10.1080/17502971003700993

- Dzinesa, Gwinyayi Albert. 2004. “A Comparative Perspective of UN Peacekeeping in Angola and Namibia.” International Peacekeeping 11 (4): 644–663. doi: 10.1080/1353331042000248678

- Grant, Richard, and Daniel Thompson. 2013. “The Development Complex, Rural Economy and Urban-Spatial and Economic Development in Juba, South Sudan.” Local Economy 28 (2): 218–230. doi: 10.1177/0269094212468400

- Hemmer, Jort. 2013. We Are Laying the Groundwork for Our Own Failure. Conflict Research Unit Policy Brief 25. Clingendael Institute.

- Henry, Marsha. 2013. “Parades, Parties and Pests: The Contradictions of Peacekeepers’ Everyday Lives.” Conference Paper presented at The 5th European Conference on African Studies. Lisbon.

- Jennings, Kathleen M. 2013. “Peacekeeping as Bypassing: A Political Economy of ‘Blue Helmet Havens.’” Conference Paper presented at The International Studies Association Annual Conference. San Francisco.

- Jennings, Kathleen M. 2014. “Service, Sex, and Security: Gendered Peacekeeping Economies in Liberia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” Security Dialogue 45 (4): 313–330. doi: 10.1177/0967010614537330

- Jennings, Kathleen M. and Morten Bøås. 2015. “Transactions and Interactions: Everyday Life in the Peacekeeping Economy.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 9 (3). doi:10.1080/17502977.2015.1054659.

- Johnson, Chris. 2012. “Peacemaking and Peacekeeping: Reflections from Abyei.” International Peacekeeping 19 (5): 640–54. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2012.722009

- Jumbert, Maria Gabrielsen, and Øystein H. Rolandsen. 2013. After the Split: Post-Secession Negotiations between South Sudan and Sudan. Noref Report. Oslo: Noref. http://www.peacebuilding.no/Regions/Africa/Sudan-and-South-Sudan/Publications/After-the-split-post-secession-negotiations-between-South-Sudan-and-Sudan

- Lie, Jon Harald Sande, and Benjamin de Carvalho. 2010. “Between Culture and Concept: The Protection of Civilians in Sudan (UNMIS).” Journal of International Peacekeeping 14 (1–2): 1–2. doi: 10.1163/187541110X12592205205658

- Martin, Ellen, and Irina Mosel. 2011. City Limits: Urbanisation and Vulnerability in Sudan—Juba Case Study. Humanitarian Policy Group. London: Overseas Development Institute. http://www.odi.org/publications/5290-referendum-urbanisation-displacement-juba-city-poverty-crime-banditry-conflict-gangs-land

- Ministry of Finance & Economic Planning. 2014. “Historical Budget Tables 2005–2014.” Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Republic of South Sudan. http://www.grss-mof.org/services/publications/?doc_sec=budget&doc_cat=budgets.

- Mores, Magali. 2013. Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption in South Sudan. U4 Expert Answer. n.p.: Anti-Corruption Resource Centre. http://www.transparency.org/files/content/corruptionqas/371_Overview_of_corruption_and_anti-corruption_in_South_Sudan.pdf

- Munive, Jairo. 2014. “Invisible Labour: The Political Economy of Reintegration in South Sudan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 8 (4): 334–356. doi:10.1080/17502977.2014.964451 doi: 10.1080/17502977.2014.964451

- Muvawala, Joseph, and Frederick Mugisha. 2014. African Economic Outlook: South Sudan 2014. Issy les Moulineaux, France: African Economic Outlook. http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/fileadmin/uploads/aeo/2014/PDF/CN_Long_EN/SoudanDuSUd_ENG.pdf

- “A New Country Rises from the Ruins.” 2013. Economist, May 4. http://lb-stage.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21577074-worlds-youngest-country-struggles-build-decent-government-and-society

- Patey, L. A. 2010. “Crude Days Ahead? Oil and the Resource Curse in Sudan.” African Affairs 109 (437): 617–636. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adq043

- Rolandsen, Øystein H. 2009. Land, Security and Peace Building in the Southern Sudan. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO). http://file.prio.no/Publication_files/Prio/Land,%20Security%20and%20Peace%20Building%20in%20the%20Southern%20Sudan,%20PRIO%20Paper%202009.pdf

- Rolandsen, Øystein H. 2015. “Another Civil War in South Sudan: The Failure of Guerrilla Government?” Journal of Eastern African Studies 9 (1): 163–174. doi:10.1080/17531055.2014.993210 doi: 10.1080/17531055.2014.993210

- Rolandsen, Øystein H., Helene Molteberg Glomnes, Sebabatso Manoeli, and Fanny Nicolaisen. 2015. “A Year of South Sudan's Third Civil War.” International Area Studies Review 18 (1): 87–104. doi: 10.1177/2233865915573797

- Shankleman, Jill. 2011. Oil and State Building in South Sudan: New Country, Old Industry. Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace.

- Stockman, Farah. 2013. “Cowboy Capitalists Rush into South Sudan—The Boston Globe.” Boston Globe, June 9. https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2013/06/08/cowboy-capitalists-rush-into-south-sudan/Mkk9CBw5idzolS3C38F1BJ/story.html

- UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UNDPKO). 2009. A New Partnership Agenda Charting a New Horizon for UN Peacekeeping. New York. http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/documents/newhorizon.pdf

- United Nations Security Council. 2005. “Report of the Secretary-General on the Sudan.” http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2005/579

- United Nations Security Council. 2007. “Report of the Secretary-General on the Sudan.” http://www.un.org/Docs/journal/asp/ws.asp?m=S/2007/42

- United Nations Security Council. 2011. “Resolution 1996 (2011).” July 8. http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1996(2011)

- United Nations Security Council. 2014. “Security Council, Adopting Resolution 2155 (2014), Extends Mandate of Mission in South Sudan, Bolstering Its Strength to Quell Surging Violence | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases.” May 27. http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11414.doc.htm

- UNMIS (UN Mission in Sudan). 2006. CPA Monitor Annex 46: UNMIS Troops Deployment by Country. UNMIS. http://unmis.unmissions.org/Portals/UNMIS/CPA%20Monitor/Annexes/Annex%2046%20-%20Troop%20Deployment%20by%20Country%20-%200610.pdf

- UN Office of Internal Oversight Services (UN OIOS). 2008a. Audit Report: Quick Impact Projects in UNMIS. New York: United Nations.

- UN OIOS. 2008b. Audit Report: Roads Repairs and Maintenance Project in UNMIS. New York: United Nations.

- UN OIOS). 2009. Provision of Permanent Accommodations in UNMIS. Internal audit report. UN OIOS. http://usun.state.gov/documents/organization/159852.pdf

- UN OIOS. 2010. Audit Report: Quick Impact Projects in UNMIS. New York: United Nations.

- UNOPS (United Nations Office for Project Services). 2014. 2013 Annual Statistical Report on United Nations Procurement. United Nations Office for Project Services. https://www.ungm.org/Public/KnowledgeCentre/StatisticalReport

- UN Procurement Division. 2015. Procurement by Country, 2005–2014, UN Procurement Division, https://www.un.org/Depts/ptd/procurement-by-country-table-detail/2005.

- US Department of State. 2013. South Sudan. Report. Department of State, Office of Website Management, Bureau of Public Affairs. South Sudan. http://www.state.gov/e/eb/rls/othr/ics/2013/204855.htm

- Van der Lijn, Jaïr. 2010. “Success and Failure of UN Peacekeeping Operations: UNMIS in Sudan.” Journal of International Peacekeeping 14 (1–2): 1–2. doi: 10.1163/187541110X12592205205531

- World Bank. 2013. “South Sudan Overview.” April. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southsudan/overview

- Zanotti, Laura. 2008. “Imagining Democracy, Building Unsustainable Institutions: The UN Peacekeeping Operation in Haiti.” Security Dialogue 39 (5): 539–561. doi: 10.1177/0967010608096151