ABSTRACT

Effective and legitimate governance supposedly form a mutually reinforcing relationship, a virtuous circle of governance. We critically explore this argument in the context of limited statehood and underline why such areas challenge key assumptions underpinning the virtuous circle argument. In this special issue we ask: Does the effectiveness of governance affect the legitimacy of governance actors and institutions in areas of limited statehood, and vice versa? We develop a theoretical model of the virtuous circle and show that making such circles work is more complex, demanding and unlikely than often assumed. Empirical studies need to take these complexities into account, and policy makers are well-advised to adjust their policies accordingly.

Introduction

This special issue on the interplay between the effectiveness and legitimacy of governance in areas of limited statehood begins with a set of questions familiar to every student of world politics: How can governance – defined here as the intentional provision of collectively binding rules and/or public goods and services (Risse Citation2011, 9) – be effective, if cooperation with political institutions is burdensome, and compliance can neither be reliably bought nor ensured by coercion? And how can governance institutions gain legitimacy, if participatory procedures are limited or even completely lacking? Over the last few decades, these questions have become a dominant problem for political scientists who have sought to explain the relative success and legitimacy of global governance institutions in an international system that lacks hierarchical structures, a monopoly of force, and democratic mechanisms (Axelrod and Keohane Citation1985; Hurd Citation1999; Scharpf Citation1999). In large parts of today’s world, weak state institutions and external and non-state governance actors struggle with a set of similar problems. This led scholars to explore the analogue question of how effective and empirically legitimate governance is possible in areas of limited statehood – that is, in polities where the state lacks the ability to implement central decisions and/or exert a monopoly over the use of force (Risse Citation2011, 4–5).

One possible answer to this question has recently gained much attention in the scholarly literature and the policy world (Levi and Sacks Citation2009; NORAD Citation2009; World Bank Citation2011; Brinkerhoff, Wetterberg, and Dunn Citation2012; Mcloughlin Citation2015). The idea is that the effectiveness and legitimacy of governance are mutually dependent and mutually reinforcing. According to this argument, effective governance increases the legitimacy of the responsible governance actors, and higher levels of legitimacy increases their effectiveness. We call this the virtuous circle of governance.

If correct, the virtuous circle argument would be of great practical importance both for domestic politics and external engagement in areas of limited statehood. It would give rise to the hope that effective service provision is the first step in a self-reinforcing process, which ultimately generates effective and legitimate political institutions in parts of the world where these are currently absent. It is for this reason that legitimacy – understood here as a population’s belief that its political institutions have a right to rule – is increasingly seen both as an antidote to state fragility (Zoellick Citation2008; World Bank Citation2011, xi, 84–89), and as a panacea for the ills of ineffective development assistance (Beisheim et al. Citation2014; Schäferhoff Citation2014), peace-building (Whalan Citation2013; von Billerbeck and Gippert Citation2017) and even full-scale state-building interventions (Lemay-Hébert Citation2009; Lake Citation2016).

It is the aim of this issue to assess whether these hopes are justified. Therefore, we ask:

– Does the legitimacy of governance actors and institutions increase the effectiveness of governance in areas of limited statehood?

– And vice versa, does the effectiveness of governance increase the legitimacy of governance actors and institutions under these conditions?

However, is the interplay between effective and legitimate governance really as simple and straightforward as the virtuous circle argument suggests? Works by authors such as Levi and Sacks (Citation2009), Schmelzle (Citation2011), Mcloughlin (Citation2015), and Krampe and Gignoux (Citation2018) indicate that the causal relationship is much more complex and demanding than it might appear at first. This introduction further develops these skeptical arguments by proposing a theoretical model of a virtuous circle of governance that goes beyond the simplistic idea that effectiveness directly enhances legitimacy and vice versa by specifying necessary preconditions and intervening mechanisms. This model helps to explain, for example, why the chances of establishing a virtuous circle might depend on the type of governance actors involved, whether there is competition between various actors, and on the policy field that they seek to regulate.

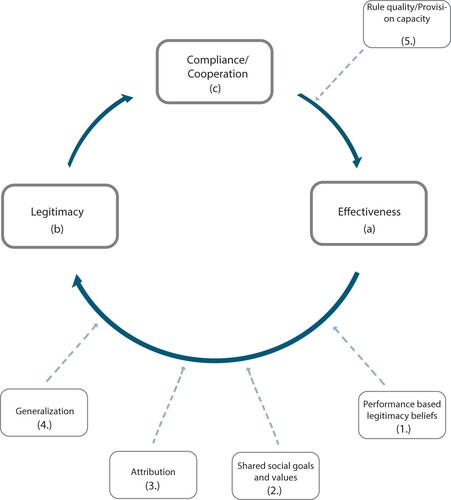

Building on our model and on the empirical results of the contributions we make three main arguments. First, on a theoretical level, we identify five conditions that have to be met in order to create a virtuous circle of governance. These are: performance-based legitimacy beliefs of governance audiences, shared social goals and values between governance actors and audiences, the attribution of governance success and failure, generalization of governance performance, and finally rule quality and provision capacity of the governance actor. These conditions make the emergence of a virtuous circle of governance more demanding and context-dependent. They suggest, for example, that it may be easier to establish a virtuous circle for less controversial and easily attributable types of governance, such as basic health care, than for more politicized or less visible goods, such as policing or environmental protection. Our model therefore cautions against a technocratic, apolitical reading of the virtuous circle argument that assumes universally beneficial solutions for every governance issue, which would automatically translate into increased legitimacy. Second, our empirical contributions corroborate these theoretical assumptions. They show that effective governance is no silver bullet for gaining legitimacy, and that legitimacy does not automatically increase governance effectiveness. While effective governance can help to enhance the legitimacy of state, non-state and external actors, and more legitimacy may translate into more effective governance, the five conditions we identify are crucial for this to happen. Third, external policy initiatives are well-advised not to rely on simplified and overly optimistic assumptions about establishing virtuous circles of governance. Development and state-building initiatives with too narrow a focus on the effectiveness-legitimacy nexus are therefore likely to fail.

The first section of this special issue consists of empirical studies that apply our model within the context of limited statehood. They provide insights on the causal relationship between governance effectiveness and legitimacy and test the heuristic value of our model and its individual components. In order to assess whether the argument can be generalized, the contributions draw on diverse data sources such as surveys and historical data, and complementary methods like experiments, regression analysis, and comparative case studies. They explore whether the emergence of a virtuous circle depends on the policy field (see e.g. Winters, Dietrich, and Mahmud (Citation2018) on public health; Mcloughlin (Citation2018) on education, or Stollenwerk (Citation2018b) on security) or type of governance actor (see e.g. Mcloughlin (Citation2018) for state-, Krieger (Citation2018) for non-state-, and Ciorciari and Krasner (Citation2018) for external actors). The wide geographical range of areas that the studies cover, including Bangladesh (Winters, Dietrich, and Mahmud Citation2018), Sri Lanka (Mcloughlin Citation2018), Timor Leste, Liberia, Kosovo and Haiti (Ciorciari and Krasner Citation2018), and Afghanistan (Stollenwerk Citation2018b), further puts the generalizability of our findings to the test.

The second part of the special issue focuses on the political, legal, and normative implications of the virtuous circle argument. The articles by Remmert and Walter-Drop (Citation2018) and Krieger (Citation2018) ask how foreign policy and international law should adapt to the role legitimacy plays in areas of limited statehood. They provide empirically grounded policy recommendations for actors engaging in development and state-building. Additionally, the contribution by Rubenstein (Citation2018) critically interrogates the conceptual framework of the special issue. Rubenstein asks whether the virtuous circle argument and the notion of limited statehood provide a one-sided and normatively undesirable model of politics in countries where state capacity is limited. The issue concludes with a summarizing article by Levi (Citation2018), critically reflecting the contributions as a whole and the avenues for future research they indicate.

In what follows, we will first introduce the term areas of limited statehood, to then explain why understanding the interplay between effective and legitimate governance is particularly important in this context. After this, we will define the key concepts of legitimacy and governance effectiveness, and introduce our virtuous circle model, which seeks to explain under what conditions these qualities are actually mutually reinforcing. Finally, we identify four specific challenges that areas of limited statehood pose for the virtuous circle argument.

Areas of limited statehood as a context for virtuous circles of governance

Since the early 1990s, the inability (or unwillingness) of state institutions to create public goods and basic social order in large parts of the world has been a dominant issue of international politics. The humanitarian costs and security risks associated with state decline have led to a vibrant debate among scholars of international relations, comparative politics, and development studies about its causes and consequences for foreign and development policy (Rotberg Citation2004; Bates Citation2008; Acemoglu and Robinson Citation2012; Lake Citation2016). At the heart of these debates is the question of how statehood, and consequently the lack thereof, should be defined (Lemay-Hébert Citation2009; Eriksen Citation2011). According to one influential school of thought exemplified by the literature on state failure (Rotberg Citation2004) and state collapse (Zartman Citation1995), statehood is a performance-based concept. This means that degrees of statehood are defined by the level of the actual provision of certain public goods and services, which are thought to be essential state functions.

There are, however, at least two major problems with performance-based definitions of statehood. The first problem concerns the underlying notion of essential state functions that form the benchmark for statehood. Theoretical work in this tradition has the tendency to treat typical features and activities of specific states, namely democratic capitalist welfare states, as essential properties of the category state (e.g. Rotberg Citation2004, 3–7; Eizenstat, Porter, and Weinstein Citation2005, 136). For example, while the provision of welfare services is an important standard for the normative evaluation of states, it seems misplaced as a condition for statehood, since it conceptually rules out the possibility of states without public welfare services. Moreover, identifying statehood with the provision of beneficial goods and services, such as security, welfare, and the rule of law seems like an unwarranted idealization. The second difficulty is that performance-based accounts define statehood by a state’s actual governance activities, i.e. whether or not it provides certain service, and not by its capacity to govern.Footnote1 This way of defining statehood and lacking statehood respectively, is problematic, since it obscures the causes of and responsibility for the absence of governance services. It fails to conceptually differentiate between cases in which poor governance services are due to lacking capacities, on the one hand, and lacking political will, on the other. The performance-based approach categorizes both as instances of weak or deficient statehood. This is unfortunate, since the distinction between unwilling and unable states has important policy implications. Whereas lacking capacities suggests a more technical policy approach that centres on aid and capacity building, the problem of lacking will calls for a more political approach that focuses on changing the incentives of the responsible actors, either by exercising pressure or offering rewards (Rubenstein Citation2018).

In response to these problems of performance-based conceptualizations, we therefore define statehood as the institutional capacity to create and implement binding rules, and to establish a monopoly of force within its entire jurisdiction. This definition allows for the possibility of states that are able but nevertheless unwilling to provide public goods. Accordingly, we define areas of limited statehood as territorial regions or policy fields, where the state lacks the capacity to set and enforce decisions and/or the monopoly over the use of force (Risse Citation2011, 4–5). In such areas, state institutions have lost what Krasner (Citation1999, 4) has called domestic sovereignty, i.e. the ‘ability of public authorities to exercise effective control within the borders of their own polity’.

This capacity-based account averts both problems of the performance-based definition: It defines statehood as the capacity to enforce political decisions independent of their content and it presupposes neither the existence of essential state functions nor the intrinsic desirability of statehood. Moreover, it differentiates between the provision of governance services and an actor’s capacity to rule authoritatively. Clearly differentiating between statehood and governance allows for taking the governance contributions of external and non-state actors seriously, since such a perspective does not automatically identify governance services with state activities. Furthermore, analyzing areas of limited statehood instead of entire countries allows for sub-national analyses of statehood and governance (see Stollenwerk Citation2018a).

Limited statehood and the interplay between effective and legitimate governance

While the virtuous circle argument could be valid for areas of consolidated statehood and areas of limited statehood alike, this special issue focuses exclusively on the latter. We think that this focus is warranted for three reasons.

The first concerns the political and humanitarian relevance of understanding how governance succeeds under these conditions. The incapacity of some states to provide social order within their jurisdictions has called attention to the social costs – exemplified by the fate of Somalia with its recurring famines and prolonged civil war – and security implications of weak states. However, the concept of limited statehood has a much wider scope than these examples suggest. More than two thirds of the world’s countries display limited state capacity in some parts of their territory or in a number of policy fields (Stollenwerk Citation2018a, 112–114). Yet a lack of state capacity does not automatically imply a lack of governance. Rather, a variety of governance actors provide collective goods under conditions of limited statehood. Examples include non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and transnational companies that supply health care (Hönke and Thauer Citation2014; Schäferhoff Citation2014), international organizations that engage in security provision (Krasner Citation2004; Matanock Citation2014), and traditional authorities that exercise jurisdiction (Kötter et al. Citation2015). Considering its importance, we know relatively little about how governance succeeds in areas of limited statehood. However, arguments for the central role of legitimacy in these contexts have recently gained popularity among scholars and policy makers, both with respect to state (Levi and Sacks Citation2009) and external or non-state actors (Whalan Citation2013; Krasner and Risse Citation2014). Given the prominence of the idea that legitimacy leads to effective governance and vice versa, more evidence on its validity is needed.

A second reason for focusing our research on areas of limited statehood is the variety and complex interplay of different governance actors in these contexts. Unlike in Western welfare states, where the state usually controls the delivery of public services, external and non-state actors play an indispensable role for governance provision in such areas. Examples that are discussed in this issue are security provision by the International Security Assistance Force’s (ISAF) in Afghanistan (Remmert and Walter-Drop Citation2018; Stollenwerk Citation2018b) or the Smiling Sun Clinics, a network of U.S.-funded, local-NGO run health care facilities in Bangladesh (Winters, Dietrich, and Mahmud Citation2018). The relevance of these external and/or non-state actors for the interplay between governance legitimacy and effectiveness is twofold. First, whether governance activities of these actors undermine or strengthen the bond between the state and its citizens remains an unanswered question. Some studies have argued that non-state service provision can undermine the state’s legitimacy, since citizens will not credit the state, but other governance actors for effective governance (Fowler Citation1991; Milner, Nielson, and Findley Citation2016). Other research has emphasized that non-state service provision might strengthen the state’s legitimacy, since citizens credit the state with successfully managing service delivery, carried out by other actors (Dietrich and Winters Citation2015; Brass Citation2016). Several contributions to this special issue contribute to this debate by exploring how and under which conditions external and non-state governance influences state legitimacy. Second, effective governance by external/non-state actors might significantly contribute to their legitimacy, and create a mutually reinforcing interplay between effectiveness and legitimacy for these actors. A specific problem that external actors and non-state actors face in this context are multiple legitimacy audiences (Bliesemann de Guevara and Kühn Citation2010; Zaum Citation2012; Coleman Citation2017). To govern effectively, external actors such as ISAF require not only a certain degree of legitimacy vis-à-vis the local population, but they also need the acceptance of a variety of other actors such as the Afghan state, the UN Security Council, or the political elites and publics of the states that contribute resources to missions. The same holds true for non-state actors such as NGOs who search for legitimacy among local actors, state institutions, funding organizations and regulatory bodies. Whenever there are multiple legitimacy audiences there is a potential for legitimacy dilemmas: Situations in which the actions that are necessary to increases an actor’s legitimacy vis-à-vis one vital audience decrease it among another. These conflicts abound in areas of limited statehood (Krieger Citation2018; Remmert and Walter-Drop Citation2018).

A third argument for the focus on areas of limited statehood is that the effects of legitimacy on governance should be particularly pronounced under these conditions (see also Risse and Stollenwerk Citation2018, 406–407). Under conditions of limited statehood, the belief in the legitimacy of a governance actor will be the only likely explanation for the cooperation of the governed, since state actors and most non-state actors lack the resources and capacities to effectively ensure compliance by either setting incentives or threatening sanctions. This forms a stark contrast to governance in consolidated states, where compliant behaviour is somewhat overdetermined. Here, sanctions and credible threats of coercion are usually attached to every official norm and regulation – both for reasons of deterrence and assurance that burdensome rules will be generally complied with (Levi Citation1988). Thus, conditions of limited statehood isolate the causal effect of legitimacy on governance effectiveness. A similar argument can also be made for the other part of the virtuous circle argument, the impact of effective governance on legitimacy. Since a reputation for effective governance is for many external actors the only source of legitimacy to draw on, areas of limited statehood provide a text-book setting for studying its effect on perceptions of legitimacy.

The key variables: Effectiveness and legitimacy

To understand the causal relationship between effectiveness and legitimacy and to illustrate how they might interact in a virtuous circle of governance, it is necessary to get a clear grasp of both concepts. In our framework, governance effectiveness and legitimacy are two distinct but interconnected criteria. While questions of effectiveness are concerned with the consequences of governance, legitimacy focuses on the empirical acceptance of governance regimes. The special issue acknowledges and discusses various sources for legitimacy, such as democratic authorization and traditional or religious authority. However, since the relationship between effectiveness and legitimacy is the core interest of the volume, performance-based sources of legitimacy are the main focus of the contributions.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness is an evaluative category that assesses political institutions and governance regimes in reference to their intended consequences. This focus on intended effects suggests a broadly teleological perspective on institutions, which construes them as tools that are supposed to fulfil specific functions (Underdal Citation2004, 27). In this view, political institutions are means to specific ends, which they either set for themselves or which are assigned to them by stakeholders. The concept of effectiveness reflects this instrumental view: An institution’s effectiveness is the degree to which it realizes the goals it is supposed to achieve (Etzioni Citation1964, 8). This definition has three important implications (Underdal Citation2004, 27–28): First, there is an important difference between the effectiveness and the efficiency of institutions. Whereas the former concept measures gross goal attainment the latter refers to net performance. Second, judgements of effectiveness do not assess whether an institution’s overall (intended and unintended) effects are beneficial or harmful, but only whether it achieves its intended aims. Third, more effective governance is not necessarily normatively better than less effective governance. Effective governance is on balance harmful either if the stated goals of an institution are objectionable or if detrimental side effects outweigh its intended positive impact. However, an instrumental perspective on institutions also implies that some degree of effectiveness might be necessary to justify the existence of governance institutions in the first place, especially if they impose costs on their subjects (Jacob, Ladwig, and Schmelzle Citation2018, 571–573). This potential relationship between an institution’s performance and its legitimacy is of course crucial for the virtuous circle argument.

Whereas the conceptualization of governance effectiveness as gross goal attainment is clear enough in the abstract, its concrete operationalization and measurement can be extremely complicated. The policy analysis literature often differentiates between three dimensions of effectiveness: output, outcome, and impact. Output refers to the implemented policy instruments, outcome describes the behavioural change that these instruments induce, while impact denotes the degree to which the stated policy problem is actually solved through this behavioural change (Young Citation2004). It is obvious that impact is, for most research questions, the most relevant of these dimensions but also the most difficult to measure. Depending on who evaluates an institution’s problem-solving record, significantly different perceptions of the effectiveness of governance may emerge (Stollenwerk Citation2018a, 115–120). Consequently, effectiveness in terms of impact is neither an apolitical nor an objective category. Assessments of effectiveness depend upon the aims and intentions of the governance actors and the values and biases of the audiences.

The virtuous circle argument focuses on the outcome and impact dimension of effectiveness. It describes how (the perception of) goal attainment (impact) leads to higher levels of legitimacy, and how (the perception of) legitimacy increases voluntary cooperation and compliance (outcome), which helps governance actors to achieve their goals (impact). However, problems of measurement and conflicting perceptions of the goals and impact of governance regimes abound here as well. Depending on their research questions and data availability, the contributions to this special issue therefore use differing conceptualizations and indicators of effectiveness and analyze effectiveness assessments from different audiences.

Legitimacy

The concept of legitimacy is infamously obscure. One source of confusion is its different application in empirical political science, on the one hand, and normative political theory, on the other. In empirical social science, the term usually refers to the beliefs and attitudes of the governed regarding the normative status of political institutions. In contrast, political theorists use the term to express evaluative judgements about the actual normative status of such institutions. These differences in usage led many scholars to make a sharp distinction between two concepts of legitimacy: one empirical (or descriptive); one normative (or prescriptive) (Beetham Citation1991, 5–15; Simmons Citation1999, 748–750).

We posit that this two-concept thesis is misleading. Instead of speaking of two different concepts of legitimacy, it is more fruitful to consider that there is an empirical and a normative perspective on the same concept. Thus, while this special issue focuses on the empirical perspective on legitimacy as the social acceptance of a governance actor’s right to rule by the relevant audiences, we are aware that these empirical expressions of legitimacy reflect normative beliefs of the audiences.

The normative nature of legitimacy is recognizable in the classic discussion of the concept by Weber (Citation1978). Weber argues that legitimacy refers to a relationship of authority between rulers and subordinates – a relationship that both parties perceive as binding. In contrast to power relationships, such relationships of legitimate authority are genuinely normative. In the eyes of the subordinates, the rulers have a right to issue morally binding norms and directives, whereas subordinates are under an obligation to comply with them, largely independent of their specific content (Weber Citation1978, see also below).

This capacity to create largely content-independent normative reasons for compliance sets legitimacy apart from other politically important motives for compliance, such as (content-dependent and prudential) genuine self-interest, (content-independent and prudential) incentives and sanctions, and (content-dependent and normative) substantive moral approval (Schmelzle Citation2011, Citation2015, 57–59). If we take the type of reason (prudential vs. normative) and content-dependence as two analytical categories, we obtain the following two-by-two matrix:

Table 1. Reasons for compliance.

The distinction between content-dependent and content-independent reasons for compliance helps us to see why legitimacy, and the ability to set incentives and create credible sanctions are essential prerequisites for the stability of every complex social order (). Content-dependent reasons for compliance – substantive moral approval and self-interest – induce compliance only if the substance of the rules in question is either in (nearly) everyone’s interest, or if substantial moral convictions converge absolutely. Both cases should be extremely rare. In contrast, sanctions and legitimacy can bring about compliant behaviour even under conditions of pervasive disagreement and conflicts of interests. The key difference between these two mechanisms is that legitimacy induces voluntary compliance, whereas sanctions can only produce begrudging compliance that evaporates when detection becomes unlikely or non-compliance less costly than compliance. As a mechanism of social coordination, sanctions and incentives are therefore either less reliable or much more costly – and often morally problematic – than legitimacy. This is especially challenging under conditions of limited statehood, where state, external, and non-state actors alike usually lack the capacities and resources to enforce rules by force in the long run.

As noted above, the belief in a political institution’s legitimacy can have different sources. Weber (Citation1978), for example, famously distinguished between charismatic, traditional, and legal-rational sources of legitimacy. Scharpf (Citation1999) more recently introduced the distinction between input and output as foundations of legitimacy. In this special issue, we differentiate between two broad categories of sources: Legitimacy derived through accepted norms (e.g. orders of succession) or procedures (e.g. elections) on the one hand (intrinsic legitimacy), and positive experiences with the performance of governance actors on the other (performance-based legitimacy). We argue that these sources of legitimacy have distinct consequences for the likelihood of cooperative behaviour and for the strength and scope of legitimacy beliefs. Therefore, different sources of legitimacy lead to varying degrees of legitimacy. gives a schematic overview of the sources, behavioural consequences, and dominant modes of reasoning of the degrees of legitimacy.

Table 2. Degrees of legitimacy.

An actor is intrinsically legitimate (the strongest degree of legitimacy) if the relevant audiences believe that its ‘rules and regulations are entitled to be obeyed by virtue of who made the decision or how it was made’ (Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Citation2009, 354). Examples of intrinsic legitimacy include democratic procedures, hereditary succession, and religious or traditional authority (see ). Whether or not intrinsically legitimate actors govern effectively is of secondary importance as long as they perform above a certain threshold. In contrast, we understand performance-based legitimacy as a weaker degree of legitimacy that originates from experiences of performances that resonate with the values and interests of the relevant audiences. The idea here is that fair and reliable delivery of goods and services deemed beneficial can earn the responsible actor the right to be obeyed even if doing so is not in the immediate self-interest of the recipient (Rothstein Citation2009). Critics of the notion of performance-based legitimacy (e.g. Levi Citation2018) argue that valued services cannot create normative reasons for compliance, and hence legitimacy, but only a prudential conviction that compliance is beneficial in the long run. From this perspective, effective governance is one part of a rational bargain in which goods and services are exchanged for cooperation rather than a source of genuine legitimacy. This rationalist critique is important for understanding the challenges and limits of gaining performance-based legitimacy through effectiveness (more on this below). However, this critique ignores that effective performance of valued services can initiate a process in which instant reciprocity transforms into more generalized forms of cooperation over time. During this process, close monitoring of exchanges and constant cost-benefit calculations are gradually replaced by more trusting attitudes, and finally normative expectations or even feelings of loyalty (see Putnam Citation1993, 163–186).Footnote2 We argue that it makes sense to speak of performance-based legitimacy as soon as effective service provision has created a general willingness to cooperate with governance actors that is not solely based on the foreseeable benefit of cooperating, but rather on a sense of obligation acquired through positive past interactions. Cooperation for reasons of performance-based legitimacy is therefore motivated rather by a logic of appropriateness than logic of consequences.

Performance-based legitimacy contrasts with another type of cooperative stance that we call benefit-of-the-doubt cooperation. Benefit-of-the-doubt cooperation is where governance addressees are willing to try their luck with a potential governance actor based on reputation and anticipated performance. In contrast to performance-based legitimacy, benefit-of-the-doubt cooperation does not create a ‘reservoir of support’ (Easton Citation1957, 399). It reflects the willingness of the relevant actors to play tit-for-tat (Axelrod Citation1984), exchanging cooperation for services. Benefit-of-the-doubt cooperation is an important category for the virtuous circle argument since it can facilitate interactions that create performance-based legitimacy in the long run.

A lack of legitimacy leads to a lack of voluntary cooperation or even active resistance against a governance actor or institution. Perceptions of illegitimacy can result from failures to deliver desired services, a lack of democratic authorization, or from the ethnic, religious or national identity of governance actors. A lack of legitimacy prevents virtuous circles of governance from evolving and may turn into a vicious circle of governance, where illegitimacy leads to ineffectiveness in a mutually reinforcing process.

The virtuous circle model

This section introduces our theoretical model of a virtuous circle of governance that identifies five conditions that influence the causal interplay between governance effectiveness and legitimacy (see Schmelzle Citation2011 for an earlier version of the model). A virtuous circle may not only develop for the state, but also for external and non-state actors or for the interplay among different actors. The model of a virtuous circle of governance in is therefore explicitly applicable to state, external and non-state actors alike.

From effectiveness to legitimacy

Following arguments of performance-based legitimacy (Scharpf Citation1999; Rothstein Citation2009), a governance actor should be considered more legitimate the more effective governance provision is. Thus, effectiveness (box a) is a potentially powerful source of legitimacy (box b). The model identifies four conditions (boxes 1–4) that are necessary to make the causal link from effectiveness to legitimacy plausible, i.e. the lower half of the virtuous circle.

Performance-based legitimacy beliefs: The effectiveness of a governance institution will only contribute to its legitimacy if the governance audience at least partly bases its legitimacy beliefs on assessments of effectiveness. In other words, governance effectiveness must be a part of the audience’s conception of legitimacy, in order to establish a causal connection from effectiveness to legitimacy (box 1). If, for example, a political community holds that only traditional or native authority is justified, then external actors will not be able to gain legitimacy, no matter how effective their governance is (see Ciorciari and Krasner Citation2018; Stollenwerk Citation2018b).

Shared social goals and values: The effectiveness of a governance regime will increase its legitimacy if governance actors and the legitimacy audiences share the same governance goals and social values (box 2). Providing education, for example, will only increase the legitimacy of a governance actor if a substantial part of the relevant audiences values (that very type of) education, finds it worthwhile and appropriate for the actor to provide it, and approves of the actor’s distribution of access to education (see Mcloughlin Citation2018). This condition prevents politically naive and technocratic readings of the virtuous circle argument that assume universally acceptable solutions for every governance problem. Instead, it suggests that the prospects of a virtuous circle dependent on the degree to which a governance issue is politically contested. Therefore, it might be easier to gain performance-based legitimacy for less controversial and rather basic types of governance, such as rudimentary health care (Winters, Dietrich, and Mahmud Citation2018), than for more politicized and contested goods, such as policing and criminal justice (Ciorciari and Krasner Citation2018).

Attribution: To transform effective rule into increased legitimacy, the governance audiences have to be able to identify the responsible governance actors and connect them to positive results (box 3). In areas of limited statehood, attributing credit or blame for governance success and failure can be challenging (Mcloughlin Citation2015, 350–351). With a multitude of governance actors, it becomes hard to identify the actors responsible for certain results and to grant them legitimacy accordingly (see Ciorciari and Krasner Citation2018; Stollenwerk Citation2018b; Winters, Dietrich, and Mahmud Citation2018).

Generalization: To make the causal pathway from effectiveness to legitimacy viable, governance audiences need to connect positive experiences to a governance institution and its representatives as a general attribute of that institution (box 4). In Easton’s (Citation1975) terminology, specific support for a policy or political action has to turn into broader diffuse support for a governance regime as a whole. Governance audiences have to transform an experience of effective governance in one specific situation or policy field into a lasting and more general understanding of an institution (see Mcloughlin Citation2018).

From legitimacy to effectiveness

The second focus of our theoretical model is the causal pathway from legitimacy to effectiveness (in terms of impact), i.e. the upper half of the virtuous circle. This argument evolves in three steps (see ). First, the assumption is that, all things being equal, an increase in a governance actor’s legitimacy (box b) will lead to higher levels of content-independent compliance and cooperation of the governed and other relevant audiences (box c). These behavioural changes reflect the outcome dimension of effectiveness. Compliance refers here to the general willingness to abide by the rules set by governance actors, whereas cooperation refers to a broader spectrum of collaborative behaviour. It ranges from non-resistance, to the acceptance of goods and services, to contributing to their production and maintenance. In a second step, the model assumes that more compliance and cooperation lead to more effectiveness (box a) in the sense of higher impact. The idea is that these behavioural changes facilitate the production of the intended public goods. However, whether or not compliant and cooperative behaviour actually solves any policy problems depends on the conditions of rule quality and provision capacity (box 5; Krieger Citation2018). This condition states that behavioural change only translates into successful policies, if the prescribed behaviour is well-suited to achieve the intended policy goals and governance actors have sufficient capacities to provide goods and services, if a satisfying level of cooperation is met.

Areas of limited statehood as a challenge for the virtuous circle argument

The virtuous circle argument was originally developed with a focus on state actors (Levi and Sacks Citation2009; Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Citation2009). This special issue, however, takes both a wider and narrower perspective: It is wider in that we do not restrict the analysis to state actors, but also explore the interplay between effectiveness and legitimacy of governance by external and non-state actors. It is narrower in that we confine our research to the context of areas of limited statehood, characterized by weak state institutions and a multitude of non-state and external governance actors. In this section, we highlight four key challenges arising from limited statehood which complicate the emergence of a virtuous circle of governance for state, external, and non-state actors alike.

Plurality of governance actors

In areas of limited statehood, external and non-state actors are indispensable for the delivery of important governance services. However, the involvement of these types of actors causes problems unique to limited statehood. A first problem arises as external governance actors particularly depend on effective performance for legitimacy, since they are usually neither democratically authorized nor able to they draw on other sources of legitimacy (Boege, Brown, and Clements Citation2009). Hence, the degree to which audiences hold performance-based legitimacy beliefs (see ) becomes crucial for external actors who cannot rely on ethnic or religious bonds or other sources of intrinsic legitimacy. Other research shows that external aid and service provision does not necessarily increase the legitimacy of the external actors (Böhnke and Zürcher Citation2013 for Afghanistan) and that alien authorities’ performance is judged much harsher than that of native ones (Blair Citation2017 for Liberia). Even if external actors provide goods and services, recipients may nevertheless view external provision as normatively defective; external engagement may only be tolerated as long as the responsible state is in absolutely no condition to fulfill its tasks (Blair Citation2017; but see Dietrich and Winters Citation2015; Brass Citation2016 for contrary evidence).

If governance is justified entirely instrumentally, the potential scope of legitimate governance is drastically diminished, since the governance actors and the affected audiences must have a preexisting shared understanding of societal goals and values, as well as corresponding policy solutions (see Jacob, Ladwig, and Schmelzle Citation2018, 572–573). Otherwise, governance actors have no mandate to rule, no matter how effective they are, according to their own assessment of societal problems and ends. In areas of limited statehood, especially external actors should therefore consider to restrict themselves to governance in policy fields for which a broad consensus on social goals and values exists (see , box 2).

A second problem arises from the plurality of governance actors. One of the main structural differences between politics in areas of limited statehood and in consolidated states is that among the plurality of actors none bears ultimate political responsibility. This multitude of state, external, and non-state actors involved in governance provision makes it extremely demanding to attribute responsibility for effective or harmful governance to a certain actor (Mcloughlin Citation2015, 350–351). One example is Haiti, the so-called republic of NGOs, where the number of active organizations prevents correct attribution and generalization (see , box 3 and 4).

Limited state capacity

By definition, state institutions in areas of limited statehood lack the capacity to govern effectively and, left to their own devices, are consequently largely unable to create performance-based legitimacy. Under these conditions, effective governance by external and non-state actors affects the legitimacy of the host state. This raises the question of whether and under what conditions does effective governance by external and non-state actors rub off on host states? Could states with limited capacity, for example, siphon off legitimacy – and, in turn, increased effectiveness – by inviting and consenting to (effective) external governance on their territory (see Ciorciari and Krasner Citation2018; Remmert and Walter-Drop Citation2018; Winters, Dietrich, and Mahmud Citation2018)? Conversely, which conditions have an opposite effect – namely effective governance by external actors undermining the legitimacy of the host state by demonstrating its own incapacity? The answers to these questions are central for policy initiatives seeking to stabilize fragile states through governance by external actors (Zoellick Citation2008; World Bank Citation2011, 185–208).

Other sources of legitimacy

Effective governance is only one source of legitimacy (Risse and Stollenwerk Citation2018, 410–411). For example, opportunities for democratic participation (Strebel, Kübler, and Marcinkowski Citation2018) and procedural fairness (Tyler Citation1990) have been shown to increase a state’s legitimacy. Furthermore, religion, ethnic identity, or charisma may be relevant sources of legitimacy in areas of limited statehood, and possibly trump governance effectiveness as a source of legitimacy (Boege, Brown, and Clements Citation2009). Yet, we know little about the extent to which effective governance aids governance legitimacy, and whether alternative sources of legitimacy could be more important. Recent research has found that procedural justice may trump effective goods and service provision in the creation of legitimate states (Fisk and Cherney Citation2017, 276–277). Thus, determining whether state, external, and non-state governance actors can indeed acquire legitimacy through effectiveness alone, or whether governance recipients ask for other qualities to attribute legitimacy to governance actors is highly relevant. If, for example, effective service provision turned out to be merely necessary but not sufficient for gaining legitimacy, this would constitute a serious problem for (external) actors that have no access to other sources of legitimacy. Additionally, attributions of legitimacy always reflect norms and values among specific audiences and these values differ and change over time as well as across geographical regions. Therefore, assuming that effectiveness of governance always leads to more legitimacy seems deterministic and implausible. How widespread sources of legitimacy are across areas of limited statehood is an empirical question that so far we know little about.

Diverse legitimacy audiences

A fourth challenge to the virtuous circle argument is the diversity of legitimacy audiences. Governance actors and institutions need to win legitimacy on the international as well as on the domestic level with different audiences (Tomz Citation2007; Zaum Citation2012; Coleman Citation2017). State-building initiatives, for example, seek to build states that are both recognized by the international community and accepted by the domestic population. This may result in legitimacy dilemmas: Situations in which the actions that are necessary to gain or maintain legitimacy with one audience decrease it with another (see Lake Citation2016). Within areas of limited statehood, diverse legitimacy audiences further complicate establishing virtuous circles of governance (Risse and Stollenwerk Citation2018, 411–413). For example, ethnic cleavages can lead to similar dilemmas in which winning legitimacy among one ethnic group may mean a loss of legitimacy with another part of the population. In situations like these, governance actors may need to prioritize whose demands they try to satisfy in order to start a virtuous circle. However, this may simultaneously lead to vicious circles of illegitimacy, resistance and ineffective governance with other audiences (Mcloughlin Citation2018).

Conclusion

The virtuous circle argument has gained prominence in debates on development assistance, peace- and state-building. It promises a causal mechanism through which effective service provision can be converted into sustainable and resilient governance institutions by increasing legitimacy. This seemingly supports the aid effectiveness agenda of the Accra, Paris, and Busan Declarations which sketch an apolitical notion of development that considers effective service provision as the sole benchmark for and justification of aid, and by extension, domestic institutions. But the hope for a virtuous circle of governance as panacea for all the problems of weak and limited statehood might be misleading. In this introduction, we presented a theoretical model of a virtuous circle which contributes to a more nuanced and politically less naive understanding of this complex causal relationship. We have argued that the prospects of converting effective governance into legitimacy depend on four conditions: performance-based legitimacy beliefs on the side of the governance audiences, shared social goals and values between governance actors and audiences, correct attribution of governance effectiveness to a governance actor, and generalization of governance success. Additionally, for increased legitimacy to result in more effective governance, governance actors need the administrative capacities to transform the audience′s willingness to cooperate and comply into impactful policies.

Areas of limited statehood as the theoretical and empirical context for this research challenge the idea of a virtuous circle of governance in at least four ways. First, the multitude of and complex interplay between different governance actors make it difficult to attribute governance success and failure to particular actors. Second, given limited capacities of the state it is questionable whether external and non-state governance helps to make or break the social contract between citizens and the state. Third, multiple potential sources of legitimacy exist in areas of limited statehood. Thus, we know little about how far effective governance can take actors and institutions in acquiring legitimacy. And finally, the diversity of legitimacy audiences renders it unlikely that a unified consensus about legitimate and effective actors will evolve.

The contributions of this special issue address those challenges and focus on different elements of the model, various policy fields, and diverse governance actors. They use a wide variety of data and methods to assess the plausibility and explanatory power of the model and the relevance of the challenges identified above. Taken together, these empirical studies make a preliminary case that the conditions identified in the model play an important role for the interplay between legitimacy and effectiveness under conditions of limited statehood. However, to further substantiate these results, future research needs to analyze the explanatory value of the model’s elements more systematically and for a wider variety of actors, issue areas, and world regions.

If virtuous circles of governance work in areas of limited statehood, they are of immense political importance. However, if the processes that lead to such circles are as complex, demanding, and politically contested as this introduction argues, there is good reason to be more humble about assumptions of establishing such circles and to adjust policies accordingly.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all authors of the special issue, the editors of the Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, and the anonymous reviewers for their detailed comments on the draft of this introduction. We also thank the commentators and audiences at the American Political Science Association's Annual Meeting, San Francisco 2017, and at the international conference of the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 700, Berlin 2017 for their input. Funding for this project has been granted by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Cord Schmelzle is a postdoctoral research associate at the Department of Political Science, University of Hamburg, Germany.

Eric Stollenwerk is a Research Associate at the Otto Suhr Institute of Political Science at the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We are fully aware that it can be epistemically challenging to assess whether poor service provision is due to a lack of capacity or to a lack of political will – not least because lacking capacities can be a deliberative result of political decisions. But this fact does neither diminish the analytical relevance of the distinction nor imply that it is always difficult to make. We have, for example, no difficulties of knowing that the dismal state of the United States’ public health care system is due to a lack of political will, not to a lack of capacity. That is why other countries do not offer the US development aid to fix their health care system.

2 Levi (Citation1988, Citation1998) makes a similar argument for the evolution of trust in institutions. Her contribution in this volume discusses the similarities and differences between performance-based legitimacy on the one hand and trust in institutions on the other.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown Publishers.

- Axelrod, Robert. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

- Axelrod, Robert, and Robert O. Keohane. 1985. “Achieving Cooperation Under Anarchy: Strategies and Institutions.” World Politics 38 (1): 226–254.

- Bates, Robert H. 2008. When Things Fell Apart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beetham, David. 1991. The Legitimation of Power. Houndmills: Macmillan.

- Beisheim, Marianne, Andrea Liese, Hannah Janetschek, and Johanna Sarre. 2014. “Transnational Partnerships: Conditions for Successful Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Governance 27 (4): 655–673.

- Blair, Robert. 2017. “Legitimacy After Violence: Evidence from Two Lab-in-the-Field Experiments in Liberia.” SSRN Working Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2326671.

- Bliesemann de Guevara, Berit, and Florian Kühn. 2010. Illusion Statebuilding: Warum sich der westliche Staat so schwer exportieren lässt. Edition Körber-Stiftung: Hamburg.

- Boege, Volker, Anne Brown, and Kevin Clements. 2009. “Hybrid Political Orders, not Fragile States.” Peace Review 21 (1): 13–21.

- Böhnke, Jan, and Christoph Zürcher. 2013. “Aid, Minds and Hearts: The Impact of Aid in Conflict Zones.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 30 (5): 411–432.

- Brass, Jennifer. 2016. Allies or Adversaries: NGOs and the State in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brinkerhoff, Derick W., Anna Wetterberg, and Stephen Dunn. 2012. “Service Delivery and Legitimacy in Fragile and Conflict-affected States.” Public Management Review 14 (2): 273–293.

- Ciorciari, John D., and Stephen D. Krasner. 2018. “Contracting Out, Legitimacy, and State Building.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 484–505. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1499198.

- Coleman, Katharina. 2017. “The Legitimacy Audience Shapes the Coalition: Lessons from Afghanistan, 2001.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 11 (3): 339–358.

- Dietrich, Simone, and Matthew S. Winters. 2015. “Foreign Aid and Government Legitimacy.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 2 (2): 164–171.

- Easton, David. 1957. “An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems.” World Politics 9 (3): 383–400.

- Easton, David. 1975. “A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5 (04): 435–457.

- Eizenstat, Stuart, John Porter, and Jeremy Weinstein. 2005. “Rebuilding Weak States.” Foreign Affairs 84: 134–146.

- Eriksen, Stein Sundstøl. 2011. “‘State Failure’in Theory and Practice: The Idea of the State and the Contradictions of State Formation.” Review of International Studies 37 (1): 229–247.

- Etzioni, Amitai. 1964. Modern Organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Fisk, Kylie, and Adrian Cherney. 2017. “Pathways to Institutional Legitimacy in Postconflict Societies: Perceptions of Process and Performance in Nepal.” Governance 30 (2): 263–281.

- Fowler, Alan. 1991. “The Role of NGOs in Changing State-society Relations: Perspectives from Eastern and Southern Africa.” Development Policy Review 9 (1): 53–84.

- Hönke, Jana, and Christian Thauer. 2014. “Multinational Corporations and Service Provision in Sub-Saharan Africa: Legitimacy and Institutionalization Matter.” Governance 27 (4): 697–716.

- Hurd, Ian. 1999. “Legitimacy and Authority in International Politics.” International Organization 53 (2): 379–408.

- Jacob, Daniel, Bernd Ladwig, and Cord Schmelzle. 2018. “Normative Political Theory.” In Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja Börzel, and Anke Draude, 564–584. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kötter, Matthias, Tilmann Röder, Gunnar Folke Schuppert, and Rüdiger Wolfrum, eds. 2015. Non-State Justice Institutions and the Law. Decision-Making at the Interface of Tradition, Religion and the State. London: Palgrave.

- Krampe, Florian, and Suzanne Gignoux. 2018. “Water Service Provision and Peacebuilding in East Timor: Exploring the Socioecological Determinants for Sustaining Peace.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (2): 185–207.

- Krasner, Stephen D. 1999. Sovereignty. Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Krasner, Stephen D. 2004. “Sharing Sovereignty. New Institutions for Collapsed and Failing States.” International Security 29 (2): 85–120.

- Krasner, Stephen D., and Thomas Risse. 2014. “External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction.” Governance 27 (4): 545–567.

- Krieger, Heike. 2018. “International Law and Governance by Armed Groups: Caught in the Legitimacy Trap?” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 563–583. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1504489.

- Lake, David. 2016. The Statebuilder’s Dilemma. On the Limits of Foreign Intervention. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Lemay-Hébert, Nicolas. 2009. “Statebuilding without Nation-Building? Legitimacy, State Failure and the Limits of the Institutionalist Approach.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 3 (1): 21–45.

- Levi, Margaret. 1988. Of Rule and Revenue. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Levi, Margaret. 1998. “A State of Trust.” In Trust and Governance, edited by Valerie Braithwaite and Margaret Levi, 77–101. New York: Sage Foundation.

- Levi, Margaret. 2018. “The Who, What, and Why of Performance-based Legitimacy.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 603–610. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1520955.

- Levi, Margaret, and Audrey Sacks. 2009. “Legitimating Beliefs: Sources and Indicators.” Regulation & Governance 3 (4): 311–333.

- Levi, Margaret, Audrey Sacks, and Tom Tyler. 2009. “Conceptualizing Legitimacy, Measuring Legitimating Beliefs.” American Behavioral Scientist 53 (3): 354–375.

- Matanock, Aila. 2014. “Governance Delegation Agreements: Shared Sovereignty as a Substitute for Limited Statehood.” Governance 27 (4): 589–612.

- Mcloughlin, Claire. 2015. “When does Service Delivery Improve the Legitimacy of a Fragile or Conflict-affected State?” Governance 28 (3): 341–356.

- Mcloughlin, Claire. 2018. “When the Virtuous Circle Unravels: Unfair Service Provision and State De-legitimation in Divided Societies.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 527–544. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1482126.

- Milner, Helen, Daniel Nielson, and Michael Findley. 2016. “Citizen Preferences and Public Goods: Comparing Preferences for Foreign Aid and Government Programs in Uganda.” The Review of International Organizations 11 (2): 219–245.

- NORAD, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. 2009. The Legitimacy of the State in Fragile Situations. Oslo: NORAD.

- Putnam, Robert. 1993. Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Remmert, David, and Gregor Walter-Drop. 2018. “Escaping the Isomorphic Bias: Towards a Legitimacy-centered Approach to State-Building.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 545–562. doi: 10.1080/17502977.2018.1546475

- Risse, Thomas. 2011. “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood. Introduction and Overview.” In Governance Without a State. Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, 1–35. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Risse, Thomas, and Eric Stollenwerk. 2018. “Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Annual Review of Political Science 21: 403–418.

- Rotberg, Robert. 2004. “The Failure and Collapse of Nation-States: Breakdown, Prevention and Repair.” In When States Fail. Causes and Consequences, edited by Robert Rotberg, 1–49. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rothstein, Bo. 2009. “Creating Political Legitimacy Electoral Democracy Versus Quality of Government.” American Behavioral Scientist 53 (3): 311–330.

- Rubenstein, Jennifer. 2018. “The ‘Virtuous Circle’ Argument, Political Judgment, and Citizens’ Political Resistance.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 584–602. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1488436.

- Scharpf, Fritz. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schäferhoff, Marco. 2014. “External Actors and the Provision of Public Health Services in Somalia.” Governance 27 (4): 675–695.

- Schmelzle, Cord. 2011. “Evaluating Governance: Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” SFB-Governance Working Paper Series Nr. 26, Berlin.

- Schmelzle, Cord. 2015. Politische Legitimität und zerfallene Staatlichkeit. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Simmons, A. John. 1999. “Justification and Legitimacy.” Ethics 109 (4): 739–771.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. 2018a. “Measuring Governance and Limited Statehood.” In Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja Börzel, and Anke Draude, 106–127. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. 2018b. “Securing Legitimacy? Perceptions of Security and ISAF’s Legitimacy in Northeast Afghanistan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 506–526. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1504855.

- Strebel, Michael Andrea, Daniel Kübler, and Frank Marcinkowski. 2018. “The Importance of Input and Output Legitimacy in Democratic Governance: Evidence from a Population-based Survey Experiment in Four West European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12293.

- Tomz, Michael. 2007. “Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations: An Experimental Approach.” International Organization 61 (4): 821–840.

- Tyler, Tom. 1990. Why People Obey the Law. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Underdal, Arild. 2004. “Methodological Challenges in the Study of Regime Effectiveness.” In Regime Consequences. Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies, edited by Arild Underdal and Oran Young, 27–48. Dordrecht: Springer.

- von Billerbeck, Sarah, and Birte Julia Gippert. 2017. “Legitimacy in Conflict: Concepts, Practices, Challenges.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 11 (3): 273–285.

- Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Whalan, Jeni. 2013. How Peace Operations Work: Power, Legitimacy, and Effectiveness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Winters, Matthew S., Simone Dietrich, and Minhaj Mahmud. 2018. “Aiding the Virtuous Circle? International Development Assistance and Citizen Confidence in Government in Bangladesh.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 468–483. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1520954.

- World Bank. 2011. World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Young, Oran. 2004. “The Consequences of Iinternational Regimes.” In Regime Consequences. Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies, edited by Arild Underdal and Oran Young, 3–23. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Zartman, I. William. 1995. “Introduction. Posing the Problem of State Collapse.” In Collapsed States: The Disintegration and Restoration of Legitimate Authority, edited by I. William Zartman, 1–14. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Zaum, Dominik. 2012. “Statebuilding and Governance. The Conundrums of Legitimacy and Local Ownership.” In Peacebuilding, Power, and Politics in Africa, edited by Devon Curtis and Gwinyayi Dzinesa, 47–62. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Zoellick, Robert. 2008. “Fragile States: Securing Development.” Survival 50 (6): 67–84.