ABSTRACT

Afghanistan has come to be seen as emblematic of the security threats besetting peace and security operations, and in this article we consider the response to such threats via the ‘bunkering’ of international staff. Drawing on an in-depth qualitative survey with aid and peacebuilding officials in Kabul, we illustrate how seemingly mundane risk management procedures have negative consequences for intervening institutions; for the relation between interveners and national actors; and for the purpose of intervention itself. Bunkering, we argue, is deeply political – ‘imprisoning’ staff behind ramparts while generating an illusion of presence and control for ill-conceived modes of international intervention.

One day in August 2015, an employee of a large development agency was driving through a middle-class residential area in Kabul. Meters away from her office armed men stopped the car and dragged her out of the vehicle. The woman was released by the kidnappers two months later but the institutional implications of this incident were far-reaching. Until that day the organization’s many employees lived in private houses across the city and were allowed to go to ‘whitelisted’ places. Now, in response to the kidnapping, almost all foreign staff were relocated away from Afghanistan. Eventually, a smaller number returned to Kabul, but they did not return to their old houses and lives. They had one hour to pack their things while an armored car was waiting for them. From that point on they were housed in one of the organization’s major office compounds. They lived and worked in the same space and were only allowed a few ‘social movements’ per week, restricted to embassies. Everyone had to be home in the evening and movements in the city were restricted to armored cars.

This incident is emblematic of the central concern of this article: the politics of the ‘bunkered’, high-security forms of intervention under way in many conflict zones today, from South Sudan (Duffield Citation2010) to Mali (Andersson Citation2016), and from Syria to Iraq and even Haiti (Lemay-Hébert Citation2018). Building on insights from such settings, we will here use Afghanistan as an illustrative case study of the larger challenges of bringing stability and aid into fragile contexts of high and uncertain security risk.

Much has been written about the broader rationales and conflicting agendas pertaining to crisis intervention and peace operations, and Afghanistan is certainly no exception. Yet while counterterrorism, peacebuilding, statebuilding and stability are fertile topics for academic and policy debate, the mundane and material aspects of how interventions are organized in practice are only rarely brought into the wider conversation. In this article, then, we aim to contribute to an incipient debate on the political dimensions of such practices in peace and aid operations. In particular, we will build on the fine-grained sociological approach of Erving Goffman, drawing analytical parallels between his notion of a ‘total institution’ and today’s bunkered interventions.

Pioneering scholarship on everyday aspects of international intervention has served to highlight the frequent gap between objectives and practices, often by recourse to an ethnographic approach. Apthorpe (Citation2011) has explored the ‘separate world’ of international aid workers through the notion of ‘Aidland’ – further adapted by Autesserre (Citation2014) as ‘Peaceland’, or the community of practitioners engaged in peace interventions. Other authors – notably Duffield (Citation2010) and Smirl (Citation2015) – have put focus on the material and infrastructural dimensions of peace and humanitarian interventions, as has Fast (Citation2014) in her critique of the predominant security-based responses to dealing with danger in humanitarian aid. In a similar vein, Bliesemann de Guevara (Citation2017) has illustrated the performative character of interveners’ practices, such as skirting security protocols, while Kühn (Citation2016) has shown how the smallest material objects – souvenirs bought by international interveners in conflict zones – may shape key audiences’ imaginaries back home, ‘orientalizing’ conflict zones.

Starting from everyday realities, all these authors emphasize how smaller scale social and material realities help give specific shape to interventions, often generating larger problems. More specifically, the security infrastructures discussed by, for example, Duffield and Fast are often judged to increase distance to the society that is being intervened upon, as our own earlier work has also shown (Andersson and Weigand Citation2015).

Building on this literature, our article takes further steps towards considering the politics of everyday, material dimensions of aid and peace interventions by exploring one of the biggest constraints on effective civilian engagement with Afghan society at a time of selective military drawdown: the security-related obstacles to getting anything done at all. What are the rationales and consequences of increasing ‘bunkerization’ (Duffield Citation2012) of international interveners’ operations and staff in response to the threat of violent attacks? How do international civilian workers, posited at the interface between donor governments, their organizations, and local society, reflect on security risk and protection measures – and what lessons can be drawn from these practitioners’ inside views for larger debates on international crisis interventions?

Before proceeding to answer these questions, a brief note on our methods is in order. Our in-depth qualitative survey with international workers in Afghanistan, conducted in 2016, sought to gain a broad understanding of how aid workers responded to security issues, which was in turn triangulated with follow-up interviews as well as with 18 months of fieldwork in the country in 2014/15 (Weigand Citation2017). Almost all our survey respondents were based in Kabul; unsurprisingly so, given the heavy skew of the international presence towards the capital in recent years. Indeed, large official development and UN agencies increasingly run projects outside the capital via ‘remote management’ of subsidiaries, partner organizations and local staff (Blankenship Citation2014). In this strategically situated ‘island’ within what Duffield (Citation2010) has called the ‘archipelago’ of bunkerized intervention, everyday security practices take on important political dimensions relevant to international engagement in the country as a whole, and indeed to international peace and crisis interventions writ large.

As regards our argument, we are not principally concerned with the ‘efficacy’ of international intervention, but rather with its politics and perception. Based on our triangulated survey responses, we argue that bunkerization and ‘hard’ security risk management reinforce certain power relationships within organizations as well as at their interface with key external actors – that is, it generates a security environment which may, in turn, have a deeper psychological as well as a broader sociopolitical impact, as we suggest in our conclusion.

Hard security risk management (SRM), which is based on the idea of providing security though measures such as walls, guards and armored vehicles, involves temporal dimensions (curfews, rest, and recuperation, or ‘R&R’); transport rules; ‘security advice’; and specific social arrangements (separation of foreigners and locals, and of workplace and leisure time). Given this multidimensional nature of hard SRM, we have chosen to approach the ‘bunker politics’ of Afghanistan through the sociological idiom of Goffman’s total institution. In Goffman’s definition, a total institution is ‘a place of residence and work where a large number of like-situated individuals cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time together lead an enclosed formally administered round of life’ (Goffman Citation1961, xxi). Prisons, convents, mental asylums and the armed forces are all examples of such total institutions, and they all have in common a breaking down of the usual barriers between different spheres of life (intimate, social, professional spaces) as well as a barrier between their self-contained worlds and the outside. ‘Their encompassing or total character’, Goffman (Citation1961, 4) writes, ‘is symbolized by the barrier to social intercourse with the outside and to departure that is often built right into the physical plant, such as locked doors, high walls, barbed wire’. In such institutions, a great degree of control is exerted over the institutionalized population with the aim of re-socializing them in one way or another – whether as ‘docile bodies’ in a Foucauldian sense, or for a specific purpose such as religious self-discipline (in convents) or war-fighting (in the forces).

Is total institution, we may ask, even a useful term for analyzing the rather exclusive social world of international intervention? With some caveats, we believe this to be the case: indeed, our survey respondents themselves talked about how ‘hard security’ transformed their daily lives into something akin to an institutionalized or even carceral experience. In ‘institutionalized intervention’, international workers find themselves severely constrained in how they operate and engage with local society while seeing their own mobility and control over everyday working and living conditions drastically reduced. From an insiders’ viewpoint, then, bunkering is political in an everyday sense that may generate counterintuitive consequences – especially, as we shall see, as insiders called the efficacy of hard SRM into question by noting its inconsistencies and frequent non-holistic implementation. While exploring this ‘infrapolitics’ (Scott Citation1990) of institutionalization in Kabul from an insider perspective, our article also ‘peeks over the bunker walls’ to ask, from an external viewpoint, whether the bunkered life of interveners does not also tell us something about the wider geopolitics of intervention. With a view to further comparative studies, we suggest in our conclusion that bunkerization presages a token international engagement of a lopsided kind that only manages to maintain an illusion of presence at great difficulty and expense – and with severe impacts on the relationship between intervener and intervened-upon populations.

Security scares and panic rooms: A preamble on the ‘Kabubble’

Before considering our empirical material in some detail, this section gives a brief overview of the growing bunkerization in Kabul in the past decade, and of the wider trend towards hard security. Among aid practitioners, hard SRM has long been the subject of extensive debate (e.g. Egeland, Harmer, and Stoddard Citation2011; Jackson and Zyck Citation2017; van Brabant Citation2000), while academic studies have emphasized one of its most problematic aspects, the growing global market in hard security provision (Abrahamsen and Williams Citation2011; Avant Citation2005; Krahmann Citation2010; O’Reilly Citation2010; Singer Citation2003). Many civilian workers and organizations exhibit significant ambivalence towards hard SRM, influenced by acceptance-based strategies from earlier decades – something we will see reflected in survey responses.

The landscape of international intervention in conflict-torn regions is increasingly structured via complex forms of risk management. For UN agencies, missions and NGOs alike, risk management is part of a duty of care towards employees, while at the same time fulfilling the stringent demands of insurers and assuaging fears ‘back home’ that expatriate citizens may be targeted. Yet the local consequences may be severe, as hard SRM entails transferring risk onto often ill-prepared frontline staff (Andersson and Weigand Citation2015). As we will argue throughout this article, it may also help shift power relations within intervening organizations and between these and the wider social and political world in which they operate, with significant consequences for the outcomes of intervention. One of these consequences concerns a growing distance to the intervened-upon society (Andersson and Weigand Citation2015; Bliesemann de Guevara Citation2016; Duffield Citation2012), as the Afghan example shows.

It is worth recalling that, following the 2001 invasion, the security regime of aid agencies in Kabul was rather different to what it is today. ‘Expatriates’ mingled at restaurant pools or simply walked to the frequent house parties in Kabul’s middle-class neighborhood, Taimani. Their vibrant lifestyle even served as a template for a French TV series (Kaboul Kitchen) and a Hollywood movie (Whiskey Tango Foxtrot). But in the late 2000s, following a surge in attacks, the security restrictions of most aid agencies were tightened. ‘Hard’ security became the norm. Most foreigners today live in compounds, hidden behind high walls, driven around in armored cars and protected by armed guards. Bunkerization has come to define the erstwhile ‘Kabubble’, as the self-enclosed social world of expatriates was already known in more joyful times.

Afghanistan today certainly is not a safe place to be. Since our survey, conducted in early 2016, security has deteriorated further. 29,867 security incidents were recorded in Afghanistan in 2017 alone (INSO Citation2018), killing or injuring more than 10,000 civilians (UNAMA Citation2018). In Kabul, suicide attacks and car bombs frequently shake the city, while assassinations and kidnaps are rampant. Major attacks have further targeted civilians. Most prominently, an explosion close to the highly fortified German Embassy in Kabul in May 2017 killed more than 90 people (Rasmussen Citation2017).

Aid workers have also been killed or injured in the past years, and have even been deliberately targeted. For instance, gunmen attacked the guesthouse of a Swedish NGO in Kabul in May 2017. Local aid workers, in keeping with the wider trend, are most frequently in the firing line: Humanitarian Outcomes (Citation2017) describes Afghanistan as the second most dangerous place for aid workers after Syria.

In this context, hard security can sometimes provide some necessary protection: to state the obvious, sitting in an armored car may be life-saving when close to an explosion. But as we will insist, security measures are much more than a technical exercise. With this in mind, in the rest of this article, we provide not so much an ‘external’ reading of security dynamics in Afghanistan, but rather wish to direct attention to the inside and investigate how international interveners themselves perceive their security – as well as the politics of their bunkered predicament. Our next section will consider our empirical findings at length, before drawing out some larger analytical implications, building on the notion of an ‘institutionalization’ of life in intervention.

Survey findings: Bunker politics and staff control

As we move onto our survey, we must emphasize that this research is qualitative. Our survey of international aid workers’ perception of their security and of SRM, conducted via an online form shared via our field networks, was not randomized, and so is not statistically representative. The sample size is small (n = 64), with some response bias potentially present. However, we have used the survey format principally to ask qualitative questions, with a focus on in-depth free-text responses, while triangulating with our previous comparative research on security management; with our long-term field research in Afghanistan prior to the survey (see Weigand Citation2017); and with follow-up interviews. The survey responses match the observations made during our field research, while also providing us with a wider range of insights into how different organizations manage security risks and how this is perceived by staff. Indeed, in a context where field research itself is becoming increasingly difficult due to insecurity and to the severe restrictions on independent research in the context of ‘hard security’, we need to explore alternatives to standard fieldwork models (Robben Citation2010). In other words, our choice of method in this instance should be read as part of a wider risk dilemma shared among academics and practitioners at work on the margins of the ‘danger zone’ (Andersson Citation2016).

Several of our respondents (at least 10 out of 64)Footnote1 worked for a major European government agency, which we will call ‘GovAg’ below. Our survey was conducted at a particular time, in February and March 2016, at a time when attacks were escalating even in Kabul – and soon after GovAg, along with other agencies, had decided to ‘bunker up’. Hence, the responses below (and particularly those from GovAg) provide a qualitative case study of how ‘hard security’ is imposed, and with what consequences, at a time of increasing panic over the presence of international staff in Afghanistan. Later, after our survey, GovAg workers were moved to an even more fortified compound at the outskirts of Kabul, the ‘Green Village’, where many aid operations are based at the time of writing (2018), and from where almost no local movement was possible. In other words, our research was situated at a particularly productive moment of change, or in a particular ‘social situation’ (Goffman Citation1961), in which security dilemmas were coming to the fore in interveners’ personal experience – offering an intriguing window into everyday reality inside the international ‘bunker’.

Security measures: Initial survey assessment

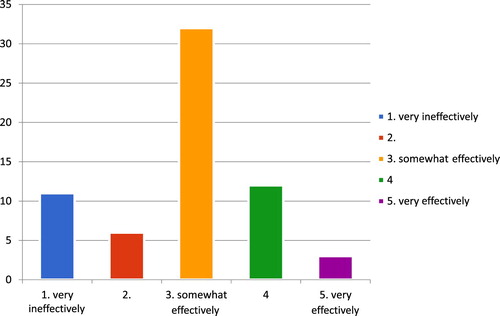

Taking the aggregate results of our survey at face value, respondents do not seem overly concerned with insecurity and security measures. Asked ‘how safe they usually feel’, the vast majority of respondents (58 out of 64) gave a value of 3 or 4 to their sense of security on a scale ranging from 1 = very unsafe to 5 = very safe. Asked about how effectively their organization’s risk management procedures helped address security concerns, somewhat more diverse responses were offered: 17 per cent (11 respondents) answered ‘very ineffectively’ (a value of 1), while half (32 out of 64) gave a value of 3; only 3 respondents answered ‘very effectively’ (). Similar answers – tilting towards a stronger sense of safety – were given when we asked more specifically about security measures at accommodation and at the place of work.

Figure 1. How effectively do your employer’s risk management procedures help to address your concerns?

So far, so unsurprising: international workers stationed in Kabul (where all but 5 of the respondents were based; the rest were in other cities in Afghanistan) are well-prepared to cope with insecurity, as one of us saw first-hand during field research. What is interesting, however, is how these answers contrasted with the free-text responses many offered to more specific questions. In sometimes considerable detail, they were highly critical of security measures as regards their inconsistencies, their side-effects, and the power relations that they helped create.

Out of our 64 respondents, 22 wrote to our optional question on whether they would like to add anything regarding security measures. Out of these, 17 were negative about hard security; 3 were even-handed or wanted more hard security; and 2 were positive about their security measures, which in both cases were of the ‘softest’ (low-profile) kind, which still existed at the time.

‘As an independent person who lives in a lower middle class area in a small apartment block and walks and uses shared taxis, I feel much safer than internationals who live in compounds and whose movements are controlled by security contractors,’ said one of these positive respondents. The other said:

As an employee of a local NGO, there were very few threats that would have been directly targeted at me. Kidnapping (mostly for financial reasons) is the only main fear. Therefore, the NGO’s security strategy (essentially, not to have a security strategy) was fine for most of the time. The absence of hard security meant I didn’t attract much attention, and could maintain a relatively high quality of life.

The negative responses to hard security, by contrast, ranged from subtle to scathing. Echoing research findings (Collinson Citation2013; Fast Citation2014; Weigand’s fieldwork conversations), many respondents noted how hard security ‘raised profile’ and changes perceptions of a locality, and so potentially created further risks, whether of a security type or in terms of work effectiveness (programmatic or financial risk). One respondent said:

I feel that instead of producing [a] realistic risk assessment, international organizations tend to generate alarms and impose extremely strict security restrictions in order to not encounter any risk. This alters significantly the perception of the local environment of their employees, affecting significantly also the quality of their work.

Another said:

Security measures are always too conservative. If you don’t allow your employees to go anywhere, you do reduce the risk of them being at the wrong place at the wrong time but you also prevent them from doing their job […] It is a difficult balance to find.

While hard security increased organizational risks in some respondents’ views, many argued that it also contributed to further insecurity. One consultant said:

I think that some security measures were more targeted at one threat, but then made another threat greater. For example – we used to drive in small Toyotas like the locals. That was great for blending in, in public. But [it] was more dangerous in case of IEDs.

While becoming a conspicuous target was mentioned by many respondents as one of the biggest drawbacks of hard security, another was the risk of untrustworthy security providers. One government agency worker said:

The harder the security, the more attention it draws, thus the less secure it can make you feel. The more people are in one place, again, the more likely the target is perceived as ‘juicy’, thus again more security brings with it the sense of insecurity.

In the view of a GovAg manager, high-profile security did not increase security ‘especially due to the fact that we have national armed guards on the compound, who could be threatened or paid outside to attack us within the compound’.

This respondent was among those seeing their organization’s security work as ‘very ineffective’. However, significantly, several of those who gave a more balanced answer of 3 to that question were also critical. One such respondent, a UN official, said, ‘Security measures taken by [UN agency] are meant to serve as a deterrent, but frequently end up attracting a high level of unwanted attention.’ In other words, respondents did not so much object to security provisions per se, but to their piecemeal and often counterproductive implementation – offering a subtler understanding of security than that propagated by their own security management.

In order to get some work done in this restrictive environment, several respondents said stretching security rules was of the essence. Forty-nine out of 64 respondents (77 per cent) reported that their organizations restricted their staff’s movements for security reasons, but 19 of them stated that they never or only sometimes followed these security rules. One said, ‘Security intelligence is so random and bad – it seems pointless.’ One UN official stated, ‘the security regulations are based on a very unlikely worst-case scenario, which hampers the work that we do. If I were to follow all the rules, it would make interviews and networking virtually impossible’. Another UN agency worker responded,

The security measures create an attractive veneer of security but would do little if we were directly targeted. If anything it makes us more conspicuous and less effective (diverting funds, alienating locals, etc.). Our management flouts certain rules to enable us to deliver on project goals but are forced to report in a specific way to headquarters.

In other words, some answers betrayed clear frustration with SRM both due to contradictions in implementation and to knock-on effects on daily work. Twenty-two respondents (34 per cent) described the security updates for staff provided by their organization as ‘useless’. As one humanitarian official with a UN agency, who gave a balanced answer of 3 to the effectiveness of security at their organization, complained:

The security approach of the organization only serves to isolate us and makes us more vulnerable. How many times have we heard that everyone is on lockdown because there is a threat against a UN compound? Can someone explain that one to me please.

More than being simply a subtle critique of the technical failings of hard SRM, the angry tone in such responses further hinted at the psychological and political implications of hard SRM, to which we will keep returning below.

‘Advice’ versus lockdown: Politics of security

Once we asked respondents more intricate questions about the everyday experience of navigating security, the criticism became stronger, and more personal. To our open optional question on whether respondents followed their organization’s security advice (‘why do or don’t you follow the advice?’), 38 gave free-text answers, of which we classified 3 as positive about SRM; 21 as largely balanced (mainly abiding by the rationale behind SRM, even though critical points were made on its relevance); while we classed 14 as negative overall about SRM, not just about specific instances of advice. Interestingly, while 7 of those gave a value of either 1 or 2 to the effectiveness of their organizations’ security procedures, 7 had rated these more positively, at 3 or 4. As one senior-level contractor in development wrote, ‘If you follow all the advice, you’ll go crazy simply because you won’t be able to leave your residence.’ Confirming observations made during field research, others did not even have that option. One GovAg respondent said: ‘There is no other choice, as we are locked into our compound. We can for sure try to avoid it through official fake invitations, but this is also limited to very rare activities.’ Another worker was scathing, in a comment of increasing relevance in the post-2016 environment:

We used to not follow [the advice] very much but then they locked us up in a compound and there’s literally no choice whether to break the rules or not anymore […] Locking your kids up is easier than looking out for them.

A growing disconnection from, and discontentment with, the employer thanks to the way hard security was imposed was thus in evidence, with responses emphasizing a sense of involuntary submission to arbitrary rules. A growing sense of employer-employee disconnect was also evident in critical notes on the business side of security. As one NGO aid manager said: ‘Security is a well-paid business that often heightens the risk and makes participants in the protocol a target.’

Amid the criticism and frustration, it was clear some workers saw SRM as, at best, a tick-box exercise covering the backs of those higher up the chain. As one mid-level UN agency official said:

It can be badly informed (UN security is somewhat of a joke), insensitive to the natural fluctuations in security, often draconian to cover the hides of security officers and thus adheres to rules for the sake of rules (rather than actual effectiveness), and paranoid.

More specifically, many respondents highlighted the power relations inherent in the imposition of ‘harder’ security. As concerns the psychology of this ‘bunker politics’ – the second strand of our argument – the sense of being ‘locked up’; of being treated as ‘kids’; and of not having any choice was affecting workers’ sense of self-esteem and self-control, with potentially very negative consequences for their morale and wellbeing.

Insecurity affected mental wellbeing for all but one of our respondents, with half of them saying it did so ‘quite a lot’ or ‘a lot’. While the risk of becoming a target was a major worry, the security measures further sharpened the sense of claustrophobia, tension, and fear. As one respondent said, drawing out a larger comparison to similar risk management procedures in other crisis zones: ‘Afghanistan and South Sudan left me burned out, constantly on the edge of a fight or tears, drinking too much, etc. It’s not the insecurity itself, it’s the crushing measures put in place as a reaction to insecurity.’

Asked optionally about how their employer dealt with risk and insecurity, 38 respondents gave free-text answers, of which we classified 19 as clearly negative; 8 relatively balanced even while including critique; and 11 as positive. Some of the positives were from those managing security or operations for their organization (‘I am the lead and we take a very immersed Afghan strategy’); from those managing their own security as independents (‘I’m free to travel on my own will to wherever I desire’); from those working in small organizations where they knew the security official well (‘he is trying to do what he think is the best’); or from those working at organizations with low-profile security (‘Generally dealt with very well, more based on negotiation than rules or physical measures’).

Among the clearly negative responses, these mainly – but not only – concerned hard security, and a range of scathing adjectives were offered on these: security measures were variously described as very bad, ‘not analytically engaged and a blanket policy’, ‘irrational and inappropriate’, arbitrary, inconsistent, ‘doing more harm than good’, ‘unhealthy’, ‘knee-jerk’, and ‘amateur’. As one respondent working for an international agency said, it was ‘a largely useless approach, fueled by Field Safety staff consisting largely of ex-military personnel’. Negative descriptions were also offered by the eight respondents giving a more balanced (‘neutral’) answer, saying security may ‘in general’ be handled well but in emergencies information was ‘poorly handled’ and procedures inadequate. As one consultant said:

Honestly, it’s rubbish. They don’t have a specific person in charge, just one of the other researchers/managers who is suddenly made a ‘security advisor’. A guy who has never been in a similar context, has no experience in that regard and who loves to dress like an American contractor. Doesn’t really make me feel much safer that he’s deciding where I can and cannot go …

Another respondent said: ‘They’re mostly just trying to be able to prove they did everything they could so that if something happens nobody can sue.’

In other words, inconsistency and lack of professionalism added to a sense of insecurity. Interestingly, however, this sentiment was shared with respondents working for organizations providing next to no security. One such respondent said, ‘There is no security policy in place and we are not insured, which makes me feel quite uncomfortable.’ On hard security, one respondent expressed a similar discomfort:

The organization does not really have a concept, from my point of view. On the one hand, we’re operating at a high profile, with armored cars etc., on the other hand, we still have only national armed guards. Altogether, very inconsequent.

In both cases – the over-production of hard security, or the absence of measures – a growing sense of disconnect from the employer was again in evidence, with not enough consideration given to a need for holistic security measures that took account of employees’ skills, views, and wellbeing.

Security at home: Zones of danger and safety

Asked, optionally, ‘how insecurity and security measures affect you at your accommodation and tell us what you think about it’, more detail was forthcoming about the sense of enclosure among those who experienced hard security. Some 11 respondents gave negative answers in free text, and all but 1 of these concerned hard security. By contrast, among the positive 11 responses almost all concerned low-profile security (as one international worker for a local NGO said, ‘Having local families next door contributes to the low-profile nature of the house. In the context of Afghan culture, it makes it feel like we are under the protection of local ‘hosts’ who care for our safety.’).

Among those giving negative responses to this question, the sense of personal, professional and cultural enclosure was prevalent: as one worker for GovAg said,

We’re not allowed to leave our compound, only for official work-related meetings. We have to wear our [GovAg] card all the time and there are cameras everywhere at the compound. Furthermore, we cannot choose with whom we want to share our accommodation, so therefore it has a big impact on our daily living.

Amid the sense of enclosure, some respondents voiced a growing suspicion of local society, and in particular of Afghan guards. One UN agency worker argued that,

While there is an ANP [Afghan National Police] checkpoint within sight of our front door, our organization believes that should we be targeted by a well-organized group (e.g. Taliban) they would conveniently be missing at the time of a raid. Thus this checkpoint may help prevent small crime, but ultimately would not assist [in] the prevention of a larger organized attack.

The one element of hard SRM that received clear positive comments was the ‘safe room’ and its infrastructure, compared favorably to the presence of guards: in the words of one respondent, ‘The safe room and multiple means of communication provide the greatest sense of security. Relying on guards, on the other hand, makes me slightly uncomfortable.’ Another offered:

We have one local unarmed guard and I’m not too convinced of his capabilities, which made me feel a bit unsafe. After a shooting in front of our gate, I convinced my housemates we needed a safe room which made me feel a lot better.

While such infrastructure was appreciated, it thus did not outweigh the additional risks of profile-raising stemming, among other things, from relocation to more prominent sites as part of a move to a compound; harder security measures at such compounds; and armed local guards. One mid-level worker for an international organization said:

We were moved from private houses to a compound recently and ever since I feel not safe anymore at all. That is mostly due to the location, as it is in a high-profile neighborhood. Before, I felt safer because no one would carry out a complex attack to get 5 foreigners. But now there’s many of us and it might just be worth it. And if that happens, the safe room is so far away from the bedrooms, it could just as well be in China.

Another said, echoing conclusions to our last section:

Security measures put in place are schizophrenic. While they are based on a hard security approach they often do not interlink at all with other efforts at ‘securing’ a location, [including] considerations about the location of the compound, soft security-type engagement with locals and the neighborhood, etc.

In short, many workers thus had a sense that hard security was not only inconsistent but that in its lack of a holistic approach it generated new dangers. Further, the resulting security environment was negatively evaluated in terms of how it distributed power, exacerbated psychological impacts, and restructured relations with local society – a key point of the next section.

Security at work: Relationships under threat

At work, there was a similar story of growing frustration with SRM. Asked about how ‘insecurity and security measures affect your daily work and what you think about it’, again an optional free-text question, 23 respondents said it affected them negatively; 5 gave a more balanced answer; and only 3 said it had no or little effect (and two of these were working in low-profile organizations). Security screenings; lockdowns; compound-based work; rules on transport (especially on the use of armored vehicles) all added to a sense of stress and frustration. In fact, as we asked respondents on their modes of transport, we had failed to consider that some were so restricted they did not move outside their compound at all: as one UN respondent pointed out,

I walk to my office, ‘cause it is in the same building. My organization would never allow me to walk [elsewhere], though I would feel relatively safe doing so and I have done so in the past – not working for the UN.

Especially at workplaces, responses indicated how hard SRM impacted on relations with local beneficiaries, Afghan staff and national counterparts, as well as on relations with other international interveners. As one respondent said, ‘Our Risk Management often announces White City or RDM [periods of restricted or no movement], therefore local staff is not allowed to report to work and we have to cancel a lot of meetings.’ Travel outside Kabul to overlook and visit their aid projects was usually out of the question. One junior international NGO worker was frustrated: ‘No ability to go to the field and monitor my projects. No ability to go to the field and help coordinate all emergency projects among multiple NGOs. Lockdowns can prevent us from attending important meetings.’ A worker at GovAg said:

Work is mostly done only from the office, field trips are very rare and need special approval. The exchange and contact between international and national colleagues hardly takes place (especially as a woman) due to several restrictions that limit the exchange after work hours.

According to another GovAg worker,

There’s no real working with Afghan ministries anymore. We cannot go out and we cannot invite them into the compound either. A lot of our staff are now working from outside Afghanistan, which makes things more complicated, too. We need to travel between Afghanistan and [our home country] all the time, which makes working hours very inefficient.

One UN agency worker said:

In an organization geared at providing humanitarian relief for local populations, it seems incredible that contact with the population frequently is impossible as a result of imposed security measures (esp. field visits – rare and few between, rather than presenting the basis for our work).

Another international NGO worker said: ‘This affects travel, when we are on lockdown. It also [affects] the relationship building element of work. There is definitely a feeling of the us/them mentality […] It is almost built into the system.’

Disconnect to local society was growing for those experiencing hard security, making work more difficult and adding to the lack of trust and understanding of the situation. One respondent, a senior UN agency manager, said:

We live and work on the same compound, with very little opportunity to go outside. Our interactions with locals are limited to work hours with national colleagues. But we are not allowed to visit them in their homes or have them over for dinner at ours for what is described as security reasons. We can’t go shopping or eat in a restaurant. We live in a fear-driven bubble.

The sense of disconnect generated, for many respondents, a deeper divide to local society. By implication, we see in the responses a certain shared sense of both locals and employees becoming disconnected in tandem from the powerful actors (whether political ones, or decision-makers in their organizations) defining the nature and form of intervention. One respondent summarized this dual predicament of locals and workers in this way: ‘No freedom; constant discussion of insecurity, including with local staff and patients who are far more affected.’ An embassy worker noted: ‘Biggest impact is the inability to go anywhere without an armed escort or [to] meet local people.’

Mental stress

‘No freedom, no privacy’, as one respondent summed it up: the sense of being controlled and disempowered was frequent, feeding into the general sense of unease and worry. Again we note how working conditions under hard security – locked into compounds, with little leisure time, restricted leisure activities and little contact with local life – took its mental toll. This was in addition to the risk of attacks itself, which was also experienced acutely by some of those in low-profile settings. Besides fear driven by attacks and the reporting of attacks via social and mainstream media, mentioned by respondents, hard security could worsen the situation considerably. As one international worker for a local NGO said: ‘Constant underlying stress, combined with [a] 6-day work week and little time off make for frequent exhaustion and occasional emotional breakdowns.’ Another said:

Insecurity simply adds to the stress already imminent in the nature of the work we do. However, as more security measures are taken, the work is more difficult, adding again to that stress. It is a vicious cycle. Personally, insecurity can give the work a little more edge, but can also be detrimental after too long a time.

The effect of security (both insecurity and security measures) on choices of leisure activity was very strong, with almost half of respondents (31) reporting it restricted their choices ‘a lot’. The most common off-time activities were catching up with international friends, including at parties in compounds, and social media contacts with those back home, rather than local engagements. Fifty-six of the respondents answered that they spend time with other international friends, while only 26 said they would do so with local friends. When asked optionally how ‘insecurity and security measures affect you in your free time’, the sense that someone else held power over respondents’ life via hard security was prevalent, along with the emotional effects in terms of frustration, lack of control and a sense of being monitored that this power relation engendered. Among those giving free-text answers on leisure, 21 gave negative responses, 13 relatively balanced ones, and only one gave a positive response in terms of no impact: ‘They do not [affect my leisure time] as I am responsible for security.’

One respondent said:

As we are not allowed to leave our compound for private reasons, we don’t really have spare time outside of the office. Therefore it is restricted to reading, watching TV, doing sports in a small gym or talking, dining and drinking with colleagues. So it has a big impact on your social contacts and leads to isolation and frustration.

One UN officer said:

As I live and work in the same compound I find it highly stressful and it is actually the only reason why I need R&R (not the actual security threats). Currently, we are also having ‘compound political’ issues, where security is trying to regulate and limit social life to a bare minimum through imposing limitations on how many people can be invited to the compound and for how long they can stay.

A GovAg worker concurred with the sense of external control and monitoring of one’s whereabouts:

Most visits to other organizations need special permission from Risk Management and the superior, who has mostly no security background. This allows the superior to know where people are going during the free time, where it might just suffice that Risk Management is informed and has given the approval.

As with reinforced workplace security, leisure-time restrictions again added to the negative consequences for relations with locals. One UN agency worker said, ‘It is impossible to establish a connection with the local population as a result [of hard security] – this, in turn, impacts the quality of the work and the types of interventions we develop.’ An international NGO consultant said security procedures

can go from not being able to meet my local Afghan friends in the place where I am housed (because there are only internationals allowed, which feels like an insult) to not being able to see them outside of the compound due to security restrictions on where I am allowed to go. This mirrors down to a feeling of isolation paired with sometimes anger (in the case of the places where nationals aren’t allowed, which feels to me like a segregated apartheid system).

Here the sense of personal frustration dovetailed with concern for locals, with both groups implicitly seen as the victims of the same system of separation enforced through hard security.

Another international NGO worker expanded on this theme of power over one’s life and relationships:

[It is] more the security measures than the actual insecurity that affect my state of mind. I find it patronizing that I need to ask for permission to go to certain places, I find it an extreme intrusion on my privacy that my Security Manager (and often also the other expats) know exactly where I am, who I am with, and what I am doing. I very much dislike my guesthouse and I hate it that I cannot choose myself where I want to live. And finally, I hate every little part of your life being monitored.

The sense of surveillance was also present to another international NGO worker:

We are extremely limited as to where we can go, and what we can do. […] Any place that we could go needed to be approved beforehand so there was very little spontaneity. The most difficult is that every single part of your life is known by your employer. Hence, many people snuck around to avoid the associated repercussions of people knowing your whereabouts.

Another NGO worker, as mentioned, brought up the carceral metaphor: ‘Every time I want to go somewhere I have to call […] a car [from the organization], they know where I am at all time, there is a curfew etc. It often feels like being in a golden prison.’

Again, some workers tried to stretch the rules to be able to get on with life and get something done, or as one UN agency worker said: ‘Because of restricted movement and transportation, life is limited to specific places during specific times, making socialization difficult. I am forced to break these rules (and lie to my employer about where I am) to have most social interactions.’ Yet in the ‘golden prison’, monitored by powerful actors in their organization via hard SRM and disconnected from local life while living in fear of attacks, a sense of purposelessness sometimes set in. While this was often implicit in the frustration expressed by so many of our respondents in the quotes above, one worker with an international organization made it explicit: ‘There is no more free time. We are barely allowed to go out and barely allowed to have friends over. So we spend most of our free time working or with colleagues, waiting to leave the country again.’

Inside the golden prison: The politics of bunker life

In extensively reporting our qualitative survey results, we have shown some of the intricacies of security risk management as perceived by international workers themselves, including purported mismatches between different elements of security provision, as well as additional risks generated by hard SRM. In what follows, we concentrate on the political and psychological/emotional aspects present in the responses above, to draw out some larger analytical implications concerning the subjective dimensions of bunkerized intervention.

In the aid world, Duffield (Citation2012) has made intriguing observations about changing aid worker subjectivities over time, from more idealistic and voluntaristic times to the professionalized aid careers of today. As he notes, institutional attempts to build a resilient ‘aid worker self’ have accompanied increased physical bunkering and selective withdrawal (Duffield Citation2012; cf. Andersson and Weigand Citation2015). However, as our survey findings show, in the Kabul of 2015–16 the ‘interventionary’ self of our respondents was clearly not fully socialized into resilient self-responsibilization. They maintained, in short, a certain distance to the institutional model being imposed upon them (even if this may yet again be changing with blanket bunkerization in the post-2016 security environment).

In other words, Goffman’s framework of a total institution may seem a counterintuitive or even unhelpful tool for understanding the social dynamics of intervention in Kabul at this time. However, in focusing on how interveners were gradually institutionalized in a particular ‘social situation’, and crucially on how they reflected on this process themselves, we may see their particular moment as one of profound change: a move from a relatively open world of intervention, where the voluntaristic ethos of earlier decades was to some degree still present, towards a closed and ‘corporate’ model. This was seen clearly when our key agency, GovAg, eventually moved all its staff from private houses scattered across Kabul into one single location – the heavily fortified ‘Green Village’ outside the city. Halfway towards this total institutionalization, then, many of our respondents were very well-placed to note its disjunctures and its damaging effects on psyche, sociality, and the politics of intervention.

If intervention was being institutionalized in Goffman’s sense, what kind of total institution did it resemble? As noted, from an emic viewpoint, the ‘total institution’ alluded to by our respondents was that of the prison. Following this line, we may indeed wish to approach the bunkerized living conditions as a ‘carceral space’, a term used broadly to describe prison-like conditions that reach beyond distinct places of confinement to encompass broader geographies (e.g. Moran Citation2015). There are some notable similarities between prisons and bunkerized intervention. First, the physical infrastructure of high walls, surveillance and armed personnel; second, the constant level of monitoring; and third, as Goffman notes as characteristic of total institutions more broadly, the restricted information pertaining to residents’ predicament. In Kabul, closed circuits of information added to the sense of powerlessness, as ‘security experts’ made final decisions on workers’ daily lives based on intelligence unknown to them. Some of our respondents said they were only confronted with decisions, not with information, making it difficult for them to make their own judgments – again echoing Goffman. We may wish to push the prison metaphor further and consider how especially the enclosed ‘totalized’ space of a compound worked almost like a Panopticon, as the intervener ‘is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication’ (Foucault Citation1975, 200).

In other words, there are grounds for taking potentially sarcastic remarks such as ‘golden prison’ quite literally, and note the parallels between carceral spaces and spaces of bunkerized intervention, broadly speaking. Above all, perhaps, the scathing way in which hard security was denounced indicates how workers found themselves on the trajectory towards institutionalization, increasingly seeing themselves as separate from – and as relatively powerless in relation to – security management.

However, besides these emic and analytical dimensions, the similarities between prisons and compounds remain rather thin. Those ensconced in fortified compounds are after all not inmates, but foreign workers who are often well-paid and are free to leave their partial confinement at any time. We believe, rather, that another total institution better reflects the kind of institutionalization seen in Kabul: the armed forces. In an expansion of Goffman’s term, Davies (Citation1989) has suggested distinguishing among institutions based on their purpose, their degree of closure, and their mode of compliance. Bunkered interventions are geared towards the performance of a defined external task (peacebuilding or statebuilding); involve a mix of coercion and normative and remunerative pressure to comply; and have a semi-closed relationship with the outside world. As such, they seem to replicate to some extent the degree of regimentation, commitment and enclosure characteristic of the armed forces, in Davies’ typology.

In a follow-up interview, one of our respondents from GovAg brought up the military metaphor when reflecting on the shifting presence of his employer in Kabul, especially with the move into Green Village. As he noted, living and working in the same space generated a kind of camaraderie familiar from the armed forces, which some workers resisted when they were first moved into shared compounds, where they sometimes had to cohabit (and share bathrooms and leisure space with) their bosses. The social arrangements – including the inability to choose where to live and with whom to share a social context, and the severe restrictions on mobility via curfews, approved destinations and prescribed forms of transport – indicated a regimented life set behind walls that very much replicated how NATO soldiers lived out their days in their Kabul compounds, as he noted.

Academics and practitioners have expended much effort on criticizing the military appropriation of humanitarianism in Afghanistan and elsewhere, as a ‘force multiplier’ in the war on terror. Coming back to our initial remarks on the scale of analysis of the Afghan conflict, our ‘micro-level’ material suggests that civilian operations in conflict zones may be ‘militarizing’ not just in the overt way of military co-optation; rather, it suggests that a subtler ‘micro-physics’ of militarization may be ongoing despite surface attempts to keep aid and military operations apart on a political level. Nor is this militarization simply about the physical surface signs of armed men and bunker walls, but is rather to be found in the social mechanisms of total institutionalization, that is, in the very sociopolitical reorganization of daily life in its temporal, intersubjective, and spatial dimensions.

We must recall that Goffman was as interested in the shared elements of different kinds of total institutions, as much as in their differences: in this vein, we may approach our Kabul case study as exemplary of the emergence of a distinct form of ‘institutionalized intervention’, complementing those listed by Davies. Moreover, we must recall Goffman’s ethnographic interest in resistance and collusion, or how ‘inmates’ and other inhabitants of total institutions engage agonistically with the structure defining their daily lives – echoing, in turn, the anthropologist James C. Scott’s (Citation1990) concern with subordinate ‘infrapolitics’ of resistance. However, our findings indicate that resistance failed to break through: it remained very much a ‘hidden transcript’, in Scott’s terms, principally revealed in anonymous survey responses and in informal field conversations.

In this regard, we may note one shared element of prisons, armed forces and aid bunkers: a ‘dependence on institutional structures’ of the kind traced by Haney (Citation2001) in his work on subjective adaptation to what he terms ‘prisonization’. This dependence may in part help explain the curious mismatch between a relatively positive or even-handed evaluation of security measures upfront in our survey, and the detailed negative and emotional responses we received further into our questioning. To borrow from Bourdieusian sociology, workers who have built their professional lives around aid interventions of the kind practised in ‘high-risk’ countries such as Afghanistan need to cultivate a certain habitus that allows them to function in their constrained environment. While this point seconds Duffield’s (Citation2010) observation about shifting forms of aid subjectivity, from a more idealistic position in earlier decades to a risk-averse aid worker subject today, our material also complicates the picture. It is clear that, in their often scathing responses, many workers who learn to cultivate the right, risk-averse ‘aid worker persona’ for times of militarized risk management are at the same time safeguarding some spaces of freedom. Psychologically in terms of their critical distance to structures of power, or practically through stretching of the rules, they find ways of drawing on all resources at their disposal (material, social, spatial and temporal) to preserve a degree of autonomy, much as inmates do in other total institutions such as the asylums of Goffman’s classic ethnography (Citation1961). This interaction between ‘subjection’ and subversion (De Dardel Citation2013) reflects the complex ‘infrapolitics’ of the bunkered aid world of Kabul – but also its limits, as attempts to ‘play the system’ repeatedly failed to blossom into political confrontation and institutional change.

Conclusion: Institutionalization and the rationales of intervention

The politics of international intervention is usually discussed at the overarching national or international level: the wisdom, say, of the military invasion of Afghanistan; of the ‘surge’, the drawdown and high-profile aerial attacks; or attempts at building a democratic state while empowering strongmen and warlords. When the focus of debate shifts to the day-to-day, small-scale realities of how interventions of different kinds are carried out, the politics is, if not left by the wayside, often de-emphasized relative to the intricacies of social and material processes of little concern to strategists, IR scholars and international policymakers. Yet our respondents in the survey were, directly or indirectly, emphasizing the politics of their predicament.

We (and our respondents) have not been concerned here with the overall ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of intervention and invasion in Afghanistan. Rather, our focus has been a more limited one: the contested power dimensions of bunkering up international civilians. However, as we will suggest in conclusion, this ‘everyday’ perspective may offer an intriguing window onto the wider political rationales and realities of intervention.

Our survey results reveal how workers highlighted an intra-institutional ‘bunker politics’ that lends power over their daily lives to security managers while severely circumscribing their work, leisure and personal spaces. Comparing the rational and emotional reactions to this shift of fortunes among aid workers with findings from the literature on total institutions, we then moved on to consider the infrapolitical dimensions of bunkered Kabul, whether in their militarized or ‘prisonized’ guise. The ‘protest statements’ as well as the initially puzzling contrasts in aggregate survey responses, we suggested here, hint at the ambivalent position workers face as they see their organizations ‘totalizing’ and controlling more and more of their daily lives, while contact points with local society, stakeholders and beneficiaries recede.

In sum, in delineating the conflictive nature of depoliticized SRM put in place for ‘workers’ own good’, we have emphasized how an account of ‘bunker politics’ needs to be accompanied by a deeper analysis of the political and psychological dimensions of the reorganization of international intervention. Further research is required to gain a more detailed understanding of these impacts of bunkerization. In particular, the ways in which local employees of international organizations and ordinary people in conflict zones perceive aid and peace interventions have to be considered, adding important empirical dimensions to the insider ‘bunker politics’ and psychology set out within this article.

We may, however, offer a few tentative suggestions for the larger comparative picture. On an institutional level, the bunkerized ‘archipelago’ (Duffield Citation2010) may be seen as serving clear political functions to the wider political project of intervention in Afghanistan. For individual agencies, as one of our respondents noted in a follow-up interview, there was often not much choice on whether to ‘stay and deliver’: some were tied directly to the political goals of ministries in their home countries, as official or semi-official development agencies, while others depended financially on the extensive aid funding disbursed in Afghanistan (much as workers benefited from the comparatively high salaries paid in this ‘high-risk’ setting). For the political paymasters back in Europe and North America, there were strong reasons not to turn back, too. Our contention is that ‘locking up the kids’ in a ‘golden prison’ where they were left to ‘count the days before leaving’ – to reiterate some striking quotes – served a very useful political purpose indeed: it indicated a semblance of ‘normality’ and ‘business as usual’, and it safeguarded decision-makers against accusations that aid worker and soldierly lives had been lost unnecessarily since the 2001 invasion, as the same interviewee again noted. As aid money kept flowing; as the EU sought mass deportation deals with Kabul for migrants arriving into Europe; and as the US escalated its kinetic approach to the Afghan hinterland, keeping some international civilians bunkered-up in Kabul ensured some historical ‘continuity’ for powerful Western governments, even if this continuity was being reduced to window dressing in reality.

Since the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, hard security has often held significant symbolic potency for international interveners and local potentates, who may signal their importance through high-visibility deterrence. In 2016–17, we see yet another, and much broader, symbolic usage of hard security in the politics of international intervention, as hard SRM facilitates a token presence in a country left to deal with the dangers ensuing from seventeen years of the ‘war on terror’, and decades of international military meddling, largely on its own. In this aspect, our respondents were also right when they compared their predicament with that of Afghans. Much as such locals were used as token beneficiaries in an aid system operated with little oversight under a strict security regime, so were international workers useful as token signs of an international presence, as some of their frustrated responses hinted. Meanwhile, the distance kept growing between both groups and global centers of power, in a pattern of remote-controlled and risk-averse international intervention that is being replicated from Kabul to Bamako, and from Tripoli to Mogadishu and Juba.

In this troubling context, scholars and policymakers must take seriously insiders’ views of today’s ‘bunker politics’ in order to arrive at more meaningful ways of building interventions to the benefit of conflict-torn societies and their inhabitants. One starting point for such a rethink, we suggest, is to be found in the attempts to break out of the restrictions that keep proliferating in the thoroughly bunkered-up ‘Kabubble’ – that is, in the infrapolitical critique and practices of insiders, whose wellbeing and productivity are ostensibly the goal of the hard security defining their daily existence in the danger zone.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Mary Kaldor and the members of the Conflict and Civil Society Research Unit at the LSE for ideas and support at various stages of our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes on contributors

Dr Florian Weigand is an ESRC Postdoctoral Fellow at the Conflict and Civil Society Research Unit, Department of International Development, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). His work is concerned with armed conflict, political authority and legitimacy, and has involved research in various conflict zones, including long-term field research in Afghanistan.

Dr Ruben Andersson is an anthropologist and associate professor at the Department of International Development, University of Oxford. He is the author of Illegality, Inc. (California, 2014) and No Go World: How fear is redrawing our maps and infecting our politics (California, March 2019).

ORCID

Florian Weigand http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2629-0934

Ruben Andersson http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3337-6437

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. All respondents had to answer what type of organization they worked for; mentioning a specific one was optional.

References

- Abrahamsen, R., and M. C. Williams. 2011. Security Beyond the State: Private Security in International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Andersson, R. 2016. “Here Be Dragons: Mapping an Ethnography of Global Danger.” Current Anthropology 57 (6): 707–731. doi: 10.1086/689211

- Andersson, R., and F. Weigand. 2015. “Intervention at Risk: The Vicious Cycle of Distance and Danger in Mali and Afghanistan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 9 (4): 519–541. doi: 10.1080/17502977.2015.1054655

- Apthorpe, R. 2011. “Coda: With Alice in Aidland: A Seriously Satirical Allegory.” In Adventures in Aidland: The Anthropology of Professionals in International Development, edited by D. Mosse, 199–220. London: Berghahn Books.

- Autesserre, S. 2014. Peaceland: Conflict Resolution and the Everyday Politics of International Intervention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Avant, D. 2005. The Market for Force: The Consequences of Privatizing Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blankenship, E. 2014. “ Delivering Aid in Contested Spaces: Afghanistan, Oxfam America Research Backgrounder.” https://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/media/files/Aid_in_Contested_Spaces_Afghanistan_1.pdf.

- Bliesemann de Guevara, B. 2016. “ Journeys to the Limits of Firsthand Knowledge: Politicians’ On-Site Visits in Zones of Conflict and Intervention.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 10 (1): 56–76. doi: 10.1080/17502977.2015.1137394

- Bliesemann de Guevara, B. 2017. “Intervention Theatre: Performance, Authenticity and Expert Knowledge in Politicians’ Travel to Post-/Conflict Spaces.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 11 (1): 58–80. doi: 10.1080/17502977.2016.1260208

- Collinson, S., and M. Duffield 2013. Paradoxes of Presence: Risk Management and Aid Culture in Challenging Environments. Humanitarian Policy Group Report.

- Davies, C. 1989. “Goffman’s Concept of the Total Institution: Criticisms and Revisions.” Human Studies 12 (1/2): 77–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00142840

- De Dardel, J. 2013. “Resisting ‘Bare Life’: Prisoners’ Agency in the New Prison Culture Era in Colombia.” In Carceral Spaces: Mobility and Agency in Imprisonment and Migrant Detention, edited by D. Moran, N. Gill, and D. Colon. Surrey: Ashgate pp. 183–198.

- Duffield, M. 2010. “Risk-Management and the Fortified Aid Compound: Everyday Life in Post-Interventionary Society.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 4 (4): 453–474. doi: 10.1080/17502971003700993

- Duffield, M. 2012. “Challenging Environments: Danger, Resilience and the Aid Industry.” Security Dialogue 43 (5): 475–492. doi: 10.1177/0967010612457975

- Egeland, J., A. Harmer, and A. Stoddard. 2011. To Stay and Deliver: Good Practice for Humanitarians in Complex Security Environments. New York: Policy Development and Studies Bureau, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- Fast, L. 2014. Aid in Danger: The Perils and Promise of Humanitarianism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Foucault, M. 1975. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Goffman, E. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Haney, C. 2001. From Prison to Home: The Effect of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families and Communities. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/psychological-impact-incarceration-implications-post-prison-adjustment.

- Humanitarian Outcomes. 2017. Aid Worker Security Report 2017. https://aidworkersecurity.org/sites/default/files/AWSR2017.pdf.

- INSO. 2018. Afghanistan Report. http://www.ngosafety.org/country/afghanistan.

- Jackson, A., and S. A. Zyck. 2017. “ Presence & Proximity: To Stay and Deliver, Five Years On”. https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/Presence%20and%20Proximity.pdf.

- Krahmann, E. 2010. States, Citizens and the Privatization of Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kühn, F.P. 2016. “The Ambiguity of Things: Souvenirs from Afghanistan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 10(1): 97-115.

- Lemay-Hébert, N. 2018. “Living in the Yellow Zone: The Political Geography of Intervention in Haiti.” Political Geography 67: 88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.08.018

- Moran, D. 2015. Carceral Geography: Spaces and Practices of Incarceration. Surrey: Ashgate.

- O’Reilly, C. 2010. “The Transnational Security Consultancy Industry.” Theoretical Criminology 14 (2): 183–210. doi: 10.1177/1362480609355702

- Rasmussen, S. E. 2017. “ Kabul: At Least 90 Killed by Massive Car Bomb in Diplomatic Quarter.” The Guardian, May 31, 2017.

- Robben, Antonius C. G. M. 2010. Iraq at a distance: what anthropologists can teach us about the war. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Scott, J. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Singer, P. W. 2003. Corporate Warriors. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Smirl, L. 2015. Spaces of Aid: How Cars, Compounds and Hotels Shape Humanitarianism. London: Zed Books.

- UNAMA. 2018. Afghanistan – Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Annual Report 2017. https://unama.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/afghanistan_protection_of_civilians_annual_report_2017_final_150218.pdf.

- van Brabant, K. 2000. “Operational Security Management in Violent Environments: A Field Manuel for Aid Agencies.” In HPN Good Practice Review No. 8. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Weigand, F. 2017. “ Waiting for Dignity: Legitimacy and Authority in Afghanistan.” PhD thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).