ABSTRACT

Studies on Security Force Assistance (SFA) have hitherto been dominated by different iterations of the principal-agent perspective to explain relations between provider and recipient. Yet, while such frameworks aptly illustrate these dynamics from a macro perspective, they are inadequate when analysing the complexity of practices on the ground. To mitigate this short-coming, the present article uses a Social Network Analysis framework to provide an in-depth micro analysis of relations between different SFA providers and the recipient state: Niger, focusing on the Belgian Special Forces. Drawing on field observations and more than 40 interviews in Niger, the present study increases our understanding of how dynamic (in)formal social networks impact the development of SFA. It points to the importance of timing, contingency and individual encounters as central in the understanding of how SFA develops and at times strays from strategies.

Introduction

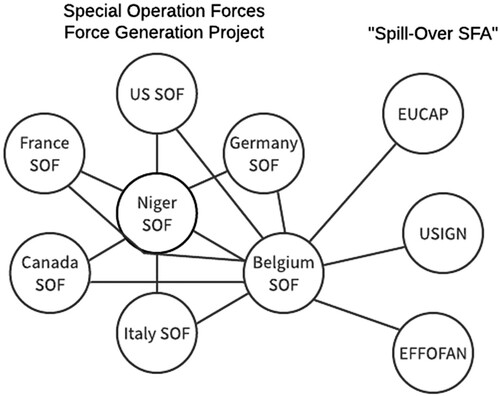

In February 2018 a Nigerien presidential order issued the Nigerien Special Operations Command to set up 12 special intervention battalions of 550 troops per battalion over the coming five years (White Paper Citation2018). The order came in the context of a rapidly deteriorating security situation with increasing threat levels on all borders of the country. Various bilateral partners had over the years provided training, equipment and assistance to different units and in different settings, yet while several Special Operation Forces (SOF) companies and battalions had been trained through multinational exercises like Flintlock, the new Force Generation Project became a coordinated structure and an objective for the various Security Force Assistance (SFA) efforts, including the Belgian SOF.

The aim of this article is to give a detailed analysis of SFA by the Belgian SOF’s engagement in Niger and illustrate how the use of Social Network Analysis (SNA) can increase our understanding of how (in)formal networks, individual connections and encounters, influence SFA. A second aim is to map provider states’ SFA projects in Niger to get an overall understanding of the context in which these activities are taking place. The article therefore contributes to the SFA literature empirically, methodologically and theoretically. Empirically, it provides a rare micro-level analysis of how SFA evolves and expands in practice. Methodologically it employs participant observation of SFA with the author embedded in a Special Forces unit in the field. Theoretically, the article is innovative as the first attempt to use SNA to complement principal-agent theory to explain SFA from a micro-level perspective.

Different types of SFA have become increasingly popular since 9/11 to fight terrorism and achieve stability in fragile regions without the provider having to deploy a considerable number of troops on the ground (Guido Citation2019). Training, equipping, advising and professionalising local forces to maintain or achieve stability have become seen as a cost- and resource efficient method to curb turbulence in areas which are prone to the proliferation of armed groups (Knowles and Watson Citation2018), but also to advance democracy in post-conflict states (Harkness Citation2015) and to maintain connections and a ‘footprint’ in former colonies (Wilén Citation2013). Often however, these efforts have resulted in unintended consequences and observers have lamented the lack of a clear strategy on the part of both providers and recipients (Matisek and Reno Citation2019; Guido Citation2019).

To increase understanding of the relations between SFA providers and recipients a dominating trend in the literature has been to adopt different iterations of the principal-agent perspective (Biddle et al. Citation2018; Burchard and Burgess Citation2019; Rittinger Citation2017). This research is useful to get an overarching idea of the bilateral relations between a provider and a recipient, yet it does not suffice to explain the complexity of relations that characterises SFA on an every-day basis, relations which often are key to the development and operationalisation of SFA. In addition, a principal-agent perspective only provides a partial explanation to why SFA efforts often fail to follow a coherent and linear strategy: interest misalignment and shirking (Biddle et al. Citation2018). This is in part because the principal-agent perspective usually focuses on a macro level, thereby ignoring micro practices which can contribute to an empirically richer and more detailed explanation. Additionally, the principal-agent approach often only focus on relations between one principal and an agent, while in reality, there are often several different principals providing assistance to the same agent, thereby suggesting a more complex relationship. To complement the principal-agent theory the present article adopts a SNA perspective to provide an in-depth analysis of the relations, networks and (in)formal connections between providers themselves, and between providers and the recipient state.

This perspective enables us to see how power relations during SFA is partly related to an actor’s position in a broader network of connections between providers and recipients. Central positions of actors with limited financial and material contributions in such networks may grant them a disproportionate amount of influence, while a remote positioning with few connections undermine such possibilities. The network position is of lesser importance for states with a large financial capacity, such as the US, since it can influence relations even outside any network due to its material and financial capabilities. Nevertheless, connections and ties with key nodes remain essential even for such major actors, as they also benefit from projecting an image of being a team player.Footnote1

For the recipient state, the more ties it develops with different providers, the more opportunities it has to ‘pick and choose’ from what still remains a largely supply-driven field of SFA. Adopting an SNA perspective on SFA implementation allows for a richer understanding of the complexity of relations, while underlining the dynamic interplay between individual actors and the broader context. It also provides us with an additional answer to why SFA efforts often fail to follow a clear, overarching strategy, as ad hoc meetings, informal networks and relations are difficult to predict and plan. These unintended networks and meetings at times result in ‘spill-over’ activities, understood as ad-hoc SFA activities that are not planned in relation to an overarching strategy or in the framework of the key SFA activity under way. It is important to understand how these spill-over activities are created, not only because they, too, form part of what SFA on the ground is, but also because they, in turn, trigger new partnerships and additional activities.

In terms of method and material, this article is based on extensive fieldwork, including participant observation of security force training, interviews and discussions with various military and civilian actors. The majority of the interviews have been conducted in Niger, during three field trips of two weeks each. During two of these trips I was embedded with the Belgian SOF and observed their everyday duties, trainings, meetings and encounters with both military and civilian actors. I also attended some formal meetings and social events. At the time of the study Belgium organised coordination meetings between several of the states which were involved in the Nigerien Force Generation Project which gave me opportunities to interview and discuss with militaries from other countries, including the host nation, Niger. This material has been supplemented with several interviews in Belgium, primarily with Belgian military officers and soldiers.

All of those formally interviewed were given a consent form to read, which I also explained verbally. Most of the interviews were conducted under the promise of anonymity. To protect the interviewees’ identities while maintaining an acceptable level of analytical precision, I have sorted the anonymised interviewees into the categories of civilian or military, Nigerien or ‘foreign’ (i.e. a non-Nigerien actor operating in Niger), while exact dates and places are omitted. Niamey is a central hub for many international NGOs and a number of military members from different states. When interviewees are stated as ‘foreign’, this multicultural environment should be taken into account. While this article relies heavily on these primary sources, the aim is not to attribute specific statements to a specific person, but rather to get an understanding of the perceptions, practices and relations that together construct SFA in the framework of the SOF Force Generation Project and beyond.

The article begins by introducing SFA through the perspective of SNA, explaining how it could complement the principal-agent framework. In the second part, the case study and the main SFA providers in the Force Generation Project illustrate the context and the actors of the social network created around SFA. An analysis of the social practices, ties, and encounters in informal meetings and the development of course material and spill-over SFA activities is the focus for the third part, before a conclusion draws out the main findings of the article.

Security force assistance from a social network analytical perspective

As the introduction to this Special Issue highlights, SFA has many, and often overlapping, definitions. In this article, SFA is understood as a set of activities performed by an external actor (provider) equipping and training an armed unit (recipient) with a stated aim to strengthen the recipients’ operational capacity and professionalism (Rolandsen, Dwyer and Reno Citation2021). It is thus not seen as synonymous to ‘remote warfare’ (Knowles and Matisek Citation2019, 11) or ‘light footprint warfare’ (Karlshoej-Pedersen, Citation2018). SFA is understood as not only aimed at (preparing for) warfighting or achieving security objectives (see for example Knowles and Matisek Citation2019), but also as practices and activities which intend to improve the capacity of a recipient state’s armed forces for other purposes. Such purposes include maintaining or developing diplomatic relations and cooperation between provider and recipient states; providing training and field experience for the partner nation’s forces (Wilén, Citation2013, Citation2019) or fostering democratisation efforts by helping to develop merits-based institutions (Harkness Citation2015, 219).

Proponents of the principal-agent approach have highlighted important aspects of the relationship between providers and recipients of SFA (Biddle et al. Citation2018; Burchard and Burgess Citation2019; Rittinger Citation2017). For instance, Biddle et al. have pointed to the fact that SFA only attracts ‘flawed agents’ to the market for assistance, since stable and institutionally strong governments rarely suffer from the kind of domestic unrest that draws interest from foreign predation threats. This often implies large interest misalignments between providers and recipients, resulting in difficult monitoring challenges and conditions of enforcements (Biddle et al. Citation2018, 97; see also Watts Citation2015, xi). Furthermore, a principal-agent perspective allows understanding how multiple principals increase the options and power of the agent to ‘pick and choose’, a tendency that can be mitigated through coordination between providers if they are willing to impose joint conditionalities upon the recipient (Biddle et al. Citation2018, 103).

Yet, the principal-agent conceptualisation does not allow for an in-depth analysis of the micro-relations between several principals, or between principals and the agent. It also fails to explain why SFA often evolves in ad hoc directions, through contingency, encounters and networks. In addition, most SFA analyses have focused on the US (Larsdotter Citation2015; Harkness Citation2015; Karlin Citation2017; Matisek and Reno Citation2019; Guido Citation2019) or the UK (Knowles and Watson Citation2018; Knowles and Matisek Citation2019) as singular, unified and monolithic principals, overlooking both small state providers and the relationships that exist between, and within, different providers, in the same recipient country.Footnote2 Precisely because of its focus on the intricate relationships between different actors, SNA can provide a useful complement to the principal-agent approach when researching SFA.

There are a number of different perspectives and studies which subscribe to the SNA approach (Scott Citation1987). Yet, all approaches share the assumption that the patterning of social ties in which actors are embedded has important implications for those actors (Freeman, Citation2004, 2). A core theoretical problem in SNA is therefore to explain the occurrence of different structures and account for variations in linkages between actors (Knoke and Yang Citation2011, 8). I draw three postulates from the broader understanding of SNA for the analysis here:

the position a node has in a network determines in part the opportunities and constraints that it encounters and is therefore of importance for a node’s performance (Borgatti et al. Citation2009, 894).

The ties that connect nodes can be divided into four different types: similarities, social relations, interactions and flows. Understanding what they are and how they influence each other is useful when deciphering and explaining outcomes of social networks (Borgatti et al. Citation2009, 894). The density and content of ties will also affect the positioning and type of interactions between nodes.

Informal associations of people among whom there is a degree of group feeling and in which a certain group norm of behaviour has been established can be understood as Cliques. As such the concept describes a particular configuration of informal interpersonal relations (Scott Citation1987, 9).

These three postulates all build on the core assumptions of SNA and together they enable us to elucidate the relationships that characterise SFA on a micro-level.

Exemplifying these postulates in this case, a central node position, such as a coordinating role for a provider of SFA, would hence yield important social capital (Scott Citation1987, 23). Translating the ties connecting nodes to the present study, similarities can include location, temporal space, and attributes such as gender and occupation. Social relations contain the roles of the nodes - for example providers are all sharing ties with the same recipient nation - while interactions can take multiple forms, from brief encounters to working alongside each other. Finally, flows take the shape of information or material that is transmitted from one node to another, such as a training course by a provider, which thereby includes the transmission of information (Borgatti et al. Citation2009, 894).

SNA can also analyse relations when there are several providers to one recipient. Understanding each actor (provider/recipient) as a node, a central node is called an ‘ego’ which is placed in an ‘ego network’ with the different SFA providers surrounding the ego. Deciding which node is to be the central point, the ego, will affect the results of the analysis (Furman Citation2016, 7). Here, the Nigerien Special Forces are positioned as the ego node. There are typically lots of structural holes in the ego network (the absence of a tie among a pair of nodes). Because of these holes, the ego performs better than the rest of the network in certain competitive settings, because it can play unconnected nodes against each other (Borgatti et al. Citation2009, 894). Conversely, if the node’s contacts are ‘bound’ together and can communicate and coordinate to act as one, they are creating a strong ‘other’ for the ego to negotiate with (Borgatti et al. 2009, 894). Thus, when the recipient state is the central node, i.e. the ego, it may pursue multiple bilateral relations with providers rather than to coordinate them – thereby increasing assistance opportunities. In contrast, if the providers manage to coordinate their efforts and align interests, the chances that they are able to affect the recipient state in the desired way increase. A node may also change its position in a network, depending on the density of ties with other nodes, in particular an ego node. In the following sections I use this ego-network conceptualisation when analysing the relationship between the different provider states, and between recipient and providers in order to understand how SFA is evolving and functioning in cases where a host nation has many different partners.

Niger – A privileged security partner

Niger is a state which consistently is found at the bottom of the UN Human Development Index, with one of the highest population growth rates in the world and chronic food insecurity and recurrent natural crises (UN HDI Citation2020). As a fragile state, it has nevertheless been a long-standing ally in the US fight against terrorism, benefitting from several different types of security assistance. The Pan-Sahel Initiative, initiated in 2003 in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, was for example followed by two new partnerships in 2005 and 2015. The larger US-initiated Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership replaced the Pan-Sahel Initiative in 2005 and started the annual multi-national Flintlock Exercise in the West African region, the US Africa Command’s SOF Exercise, which gathers over 2000 personnel from more than 30 states on an annual basis (AFRICOM). Niger’s central role in two of the more recent regional security collaborations, the Multinational Joint Task ForceFootnote3 and the G5 Sahel Joint ForceFootnote4, as well as its contribution of troops to multilateral peace operations, has reinforced its central role for SFA efforts in the region. Between 2011 and 2015 for example, Niger was one of three states taking part in the EU’s Counter Terrorism Sahel Project, an initiative which aimed to improve the capacity of internal security forces and judiciary to prevent and deter organised crime and terrorism (EU Commission Citation2015), while EUCAP Sahel Niger has provided advice and training to Niger’s security forces to increase capacity and interoperability since 2012 (EUCAP Sahel).

In spite of these efforts, the security situation has rapidly deteriorated in recent years due to an increase in IED attacks, particularly against the security forces in the West of the country (ACLED Citation2019), as well as a swift spill-over of terrorist groups and refugee flows from neighbouring states on all borders, but especially from Mali and Burkina Faso. As a result of this, direct attacks on civilians in Niger have also risen steeply, with a 500 percent increase between November 2018 and March 2019 compared to the same period the year before (ACLED Citation2019). In 2021 attacks on two villages left 105 dead, while attacks on three villages in the Tahoua region close to the Malian border killed 137 people in March the same year. These attacks come from both non-state militias and Nigerien armed forces. The Nigerien forces have themselves suffered a large number of casualties during the past two years. Rebels killed 71 soldiers in an attack in December 2019, yet the deadliest incident to date was the battle of Chinagodrar in January 2020 when armed militias attacked a military base in the Tillabéri region resulted in 89 soldiers’ deaths.

At the same time the Nigerien armed forces have, just as the neighbouring armies, been accused of an increasing number of abuses and extrajudicial killings in the past two years, most recently in September 2020 when a Human Rights report accused the army of the disappearance of 102 civilians after the discovery of a mass grave in the Tillabéri region (Mamane Citation2020). A major corruption scandal also shook the Nigerien Defence Ministry in 2020, when it was discovered that over $137 million had been lost in rigged bidding processes, fake competition, and inflated pricing in international arm deals (Anderson et al. Citation2020). These recent developments have been overshadowed by Niger’s geostrategic location, regional involvement in security collaborations and the President’s willingness to host foreign troops for SFA providers. Niger is thus currently host to hundreds of troops from several different Western provider states. The recent Force Generation Project in Niger should be seen against this backdrop of a fragile state in a deteriorating security situation.

I. With a Little Help from My Friends: Niger SOF Force Generation Project

Belgium – A coordinating role

Belgium’s Memorandum of Understanding with Niger from 2005 was in a ‘sleeping mode’ until Niger became Belgium’s partner nation in the Flintlock Exercise in 2015. After only two years, Belgium decided to expand its military collaboration with Niger and establish a long-term partnership in an operation called Operation New Nero (ONN) (Wilén Citation2019). In early 2018, a unit of approximately 10 people from the Belgian Special Forces started exploring various opportunities in Niamey to contribute to SFA. They met with both the Nigerien Military and other Western Partner Nations (WPN) to discuss possibilities. The Belgian unit rapidly seised the opportunity to develop a common curriculum: Programme Of Instruction (POI) together with Nigerien authorities and other WPNs, to standardise the training of the Niger SOF (Interviews with Belgian Military, Brussels, November 2018; Interview with Nigerien Military, Niamey, March 2019). Belgium’s initiative in the POIs gave it an unofficial role as a coordinating element between the different WPNs taking part in the Project and the Nigerien Special Operations Command early on (SOFLE’s 3D Network). As such, it has been able to establish sustained relations with several other actors, including civilian organisations, and develop dense ties with the Nigerien Special Forces node, as we will see below.

US – A long-term, heavy footprint

The US has been training and equipping Nigerien security forces since 2002 under various military programmes, however, it was not until four American Green Berets and four Nigerien soldiers were killed in an ambush outside of Tongo Tongo in 2017 that the US presence in the country attracted wide-spread scrutiny from the media (Lebovich Citation2017; Baillie Citation2018; Penney Citation2018; Morgan Citation2018; Turse Citation2018). Since then, US forces in the country have faced increased attention, but according to media, the military continues to ‘obscure the nature of its actions through ambiguous language and outright secrecy’ (Penney Citation2018). The US has a substantive presence in the state, with five military sites in places like Arlit and Ouallam, including two cooperative security locations in Niamey and Agadez (Turse Citation2018). In Agadez, the US has also constructed a $110-million drone base which will permanently house US troops and Nigerien special forces (Ajala Citation2018, 24). At the time of the attack in October 2017, the US had approximately 800 troops in the country which constituted the state hosting the second most US military personnel in Africa (Watson Citation2017).

In addition to these initiatives, the US is also playing an active part in the SOF Force Generation Project. As noted above, US SOF have trained several Nigerien companies, constituting battalions, even before 2018 yet since 2018, this training is inscribed in the larger Force Generation Project. Between April 2018 and July 2019, the US has trained at least six special intervention companies in various locations in Niger (Interview WPN Military, Niamey, March 2019). In addition to these companies, the US has also trained and equipped two other Special Forces Companies called FEN (Forces Expeditionaires du Niger) of about 130 troops each, which are deployed to two different regions in Niger (Niger Internal Document; Interview with WPN military, Niamey, March 2019). Thus, as a long-standing SFA provider, the US has strong bilateral ties with Niger buttressed by considerable flows of equipment, training and financial assistance. The connection between the US and Niger node is crucial to the Force Generation Project overall, yet the US has chosen to avoid playing a coordinating role in the larger network of providers.

Germany – training and infrastructure

Military engineers from Niger have been trained in Germany since 1993, but the German SOF operation Gazelle Niger is relatively recent (Interview with WPN military, Niamey, March 2019). Since early 2018, Germany has reinforced its presence in the country, closely linked to its engagement in neighbouring Mali, where Germany has 190 personnel working for EU Training Mission in Mali (EUTM Mali) and approximately 400 troops for MINUSMA, located in Camp Castor in Gao (Kelly Citation2019). Discussions about how Operation Gazelle can integrate into the expanded EUTM Mali mandate in Niger were underway in 2021. Germany’s engagement in MINUSMA was also the background for the decision to build a military base in Niger. Finished in November of 2018, it serves as a logistical base for hostage missions and to assist the UN mission in Mali (Interview WPN military, Niamey, March 2019). Yet, presently Germany is most visible in the building of military infrastructure in Niger, including a Military Academy in Agadez for Non-Commissioned Officers and another Military Academy for the Special Operations Forces in Tillia.

The Special Operations Academy is key to the Force Generation Project as it will host technical and tactical qualification courses as well as certification for the units, meaning that they will receive a certificate proving that they have passed the courses required for the Special Operations Forces. The aim is that Niger will be able to run the academy after two years of WPN assistance in training and doctrine writing (Interview WPN, Niamey, March 2019). Germany is financing the building of the Special Operations Academy, yet when it comes to the doctrine development and the actual conduct, Niger and Germany are collaborating with other WPNs (internal document). In terms of formation of the Special Intervention Companies, the German unit arrived in May 2018, and decided to move into a house opposite the Belgian unit after a meeting to facilitate conditions for collaboration (Interview with WPN Military, Niamey, March 2019). Germany started training the first company in October 2018 with an additional two companies being trained during 2019 with the new POIs. Germany has chosen to only use Special Forces units for the training, given the high security risks in the regions where the training takes place (Interview WPN Military, Niamey, March 2019).

Canada – A growing engagement

Canada’s involvement in Niger takes place within Operation Naberius, which since 2013 has been Canada’s contribution to Exercise Flintlock (Raffey Citation2017). Canadian troops have also conducted bilateral training of Nigerien troops since 2016, with two training courses per year, lasting 8 weeks (Interview WPN Military, Niamey, March 2019). Since the fall of 2018, when the POI was approved by Niger, the Canadians have taught the new 14-week POI with the support of Belgian soldiers so that the Belgians could notice first-hand the effect in practice and later adapt it accordingly to better serve the Nigeriens. The plan is to continue to teach a 14 weeks training course in spring-summer and an 8 weeks training in the fall of each year (Email correspondence WPN, Military May 2019). This training falls under the current Force Generation Project, which is supposed to be completed by the end of 2022, yet, so far there is no official end-date for Canada’s involvement in the training.

Practices, labour division, social networks

Since the beginning of 2018 the Belgian Special Forces have somewhat unexpectedly taken on an unofficial coordinating role for the providers involved in the Force Generation Project. It is surprising, given Belgium’s relatively recent presence in Niger, its limited capacity to provide equipment, and the fact that prior to 2018 it had not trained any complete battalion, contrary to the US. Drawing on the SNA postulates introduced earlier however, allows explaining Belgium’s central position in the SFA networks. Partly, it can be explained by the similarities in relations between Niger and Belgium. A first similarity is the language. The Belgian unit’s language capacities in French greatly facilitate communication with the Nigerien French-speaking colleagues. Contrary to France, Belgium also benefits from not having any colonial history in the country. France, also sharing a common language with Niger, has been a latecomer to the Force Generation Project, thereby having to adapt to the (in)formal structures already in place.

Another similarity is the fact that Belgian and Nigerien armies are roughly the same size. This strengthens Belgium’s cognitive social relations, in the sense that it ‘understands’ the context and what is has to work with, while preventing it from becoming perceived as an imposing or threatening power – both to the Nigeriens and to the other WPNs. Drawing on its central role, Belgium has also been keen to set up coordinating meetings and social practices between WPNs, Nigerien key actors and actors from civil society which have generated new opportunities for expanding and multiplying SFA activities outside of the Force Generation Project. Belgium’s informal coordinator role has benefitted from structural attributes such as language and army size, but also contingencies such as timing, proactive team members on the ground, and important personal connections with Nigerien key actors and other Western providers. The fact that no other state involved seem to have sought this coordinating role is clearly also facilitating Belgium’s position. This role is nevertheless not fixed: networks are dynamic and change continuously. Particular structural relations exist only at specific time-and-place locales and either disappear or are suspended when participants are elsewhere (Knoke and Yang Citation2011, 5), making the sustainability of the current configuration dependent on how the context and the actors evolve over time.

The Belgian Special Forces in Niamey started what they called ‘SOF Fusion Cell’ meetings between the providers involved in the Force Generation Project as well as a Nigerien representative during 2018. The ‘Fusion Cell’ meetings gather representatives from the different WPNs involved in the project, usually the national coordinator– technically referred to as Special Operations Force Liaison Element (SOFLE) – and another team member. The meetings take place in the Belgian team house every two weeks (Dehaene Citation2019). The Belgian SOFLE starts off the meeting by summarising the different SFA activities that have taken place since the last meeting, or that are scheduled to take place, and also takes up a few issues for discussion. Each representative then takes his turn, summarising the main activities since last meeting and identifying issues at stake that needs to be discussed. Topics range between lessons learned from the actual teaching of the new POIs in practice, the building of the military academy, to more day-to-day coordination concerning when and where training courses will take place (Interview with WPN Military, Niamey, October 2020).

The establishment of the ‘Fusion Cell’ meetings can be described as a ‘sub-group’, a clique of the broader social network that the Force Generation Project constitutes. The meetings are informal, and they take place between a group of people where there is a degree of group feeling and in which a certain group norm of behaviour have been established (Scott Citation1987, 9). In the case of the ‘Fusion Cell’, the group feeling is established through several ties. The similarities are evident: they are all in Niamey (location), of the same genderFootnote6 (attribute), working in similar organisations (membership), and importantly, they all identify as Special Forces, a strong identity marker not only outside the military, but also within the different military divisions and departments. In terms of social relations, they are all working together as providers to the Niger military. They are interacting and collaborating through the meetings, and thereby also contributing to flows of information, and at times of resources. While there is a certain ad-hoc aspect to its existence due to its informality, there are also aspects which can be manipulated. Each ‘national node’ can for example choose to deploy a representative that fits into the ‘clique’, in terms of similar attributes, like gender, age, and membership.

The creation of this sub-group is clearly part of the larger social network that is constituting and shaping SFA in Niger. A clear group norm among the SFA providers is to avoid duplicating other actors’ efforts and respect each other’s sovereignty – each actor has the choice to collaborate or not. Its existence facilitates communication and coordination between the providers to the extent that the members are willing to share their bilateral projects. It also makes it possible to identify common problems and solutions by building on each others’ experiences and resources, both human and material. While the relations within the clique appear to flow relatively smoothly, the fact that this is an informal, voluntary and horizontal group also makes its existence delicate.

A natural division of labour takes place, due to the fact that each WPN has its ‘own’ battalions to train and equip. New demands for training and equipment for additional battalions from different units in the Nigerien army are also discussed during the ‘Fusion Cell’ meetings: there are several actors outside of the Nigerien Special Forces who are interested in formations and equipment. One participant explains that his contingent will get a visit from national expert trainers in a particular domain which interests another team. The opportunity to collaborate is seised and they decide to discuss specific modalities closer to the date (Interview WPN military, Niamey, March 2019).

Discussions also evolve around the type of weapons training that each contingent will give, making sure that they are talking about the same weapon and the same techniques and thereby ensuring standardisation of training and material. Here, the asymmetry between the WPN becomes evident as Belgium is not contributing any equipment apart from a locally produced first aid kit while the US, Canada and Germany are all providing considerable amounts of military equipment (Interview with WPN Military, Niamey, March 2019). One team leader explains that he would like to identify methods of planning and milestones with the Nigerien counterparts to better coordinate training between the different units, which others agree is important. The Belgian SOFLE takes notes throughout the meeting, while asking clarifying questions at times and summarising discussions for a minute report that is sent to everyone after the meeting (Interview with WPN Military, Niamey, March 2019).

Every other week, the Belgian contingent organises a social event, with drinks and snacks for a wide range of civilian and military actors in Niamey. The ‘Fusion Cell’ meeting often takes place immediately before the social event, which facilitates the participation of the different unit members. Apart from the Special Forces members, advisors and trainers from multilateral missions like the EU mission (EUCAP) are invited. Expat staff from NGOs and civilian personnel from embassies of the different WPNs are also regular invitees at these social encounters, just as Nigerien commanders and at times Nigerien academics (Author Observation, Niamey, March, October 2019, November 2020).

A military officer explains why he finds these social encounters very useful:

‘Yesterday for example, I talked to a girl that worked for an NGO that is present in the region where we will do the training for our companies. I could get information about the security situation in the region without having to go there, and I now also have a contact which can help us establish contacts with local population in the area, once we are in place’ (informal discussion, WPN Military, Brussels, May 2019).

These regularised social gatherings are complemented by smaller meetings between provider SOFLEs to discuss specific aspects, while the Nigerien SOF Commander maintains contact with the respective SOFLEs through continuous meetings. As I was on my way into the interview with the Commander for example, a SOFLE from one of the provider states was on the way out of the office, while another is scheduled for a meeting later during the same day. The Commander, who has been trained both in the US, and by the US in Niger, speaks an impeccable English and is particularly appreciated by providers because he has an understanding of both how Western and the Nigerien armed forces’ function.

Belgium’s central role in the field of social networking is not coincidental, but part of their strategy to build trust among key contacts, both WPN and Nigerien actors (SOFLE 3D Networking internal document). The understanding is that building social networks will open up new opportunities for collaboration and gradually diminish obstacles. The Belgian unit in place has therefore reached out to both civil and military actors in Niamey, through formal and informal events and presentations of the presence and purpose of the Belgian SOF in Niamey (BEL SOFLE COS FGP). Underpinning their presentation is the Localization Strategy which is the current guiding document for Belgium’s presence in Niger and which advocates for a non-intrusive, self-sustainable resilience enhancement approach (Dehaene Citation2019). It is also this approach which has been the basis for the development of the new POIs.

I. The Development of a Standardised Program of Instruction (POI)

The complete POI consists of more than 11 modules that constitute the technical phase of an initial qualification course for special intervention battalion soldiers and cadres, including subjects such as marksmanship, navigation, counter IED (improvised explosive devices), small unit tactics and combat first aid (Dehane Citation2019, 38). The writing of the new POIs was mostly done by the Belgian unit in place, but other providers also assisted, while communication and exchanges with Nigerien commanders took place continuously to ensure that the content was adapted to the local context (Interviews WPN & Niger Militaries, March 2019). The influence of the civil–military encounters is also reflected in the new POI. Representatives of humanitarian organisations have been invited to presentations of Belgian Special Forces’ presence in Niamey and its involvement in the Force Generation Project, including the development of the new POI modules. These meetings have facilitated a civil–military collaboration which have resulted in both the UNHCR and ICRC writing modules for the new POIs, and ICRC giving a module in the Asymmetric Warfare course (SOFLE’s 3D Networking).

The development of the new POIs clearly shows the importance of networks and an understanding of, and guidance from local realities. Yet, it also demonstrates inconsistencies in the standardisation process and asymmetry between the WPNs. While most WPNs have now agreed to use the new POIs, there are still states which are not using them in their training, making it difficult to talk about a complete standardisation. One military bluntly stated that: ‘they [a WPN] continue to do their thing, and in any case, the Nigeriens do their own POIs after our training’ (Interview WPN Military, Niamey, March 2019).Footnote7

II. ‘Spill-Over SFA activities’ as Consequences of Social Networks

Several other ‘spill-over SFA activities’ are also a result of the Belgian unit’s local centrality in the POI network and the fact that one of the key Nigerien contact persons involved in the development of the POI was on loan from the Nigerien Special Forces to the national officer academy EFFOFAN (Interview with Nigerien Military, Niamey, March 2019). This means a strengthened connection between the Belgian unit, the Special Operation Command and the officer academy. In the development of the SOF POI for the module on Military Operations in Urban Terrain for example, a two-week train-the-trainer course is given to approximately 50 Nigerien officer candidates at Officer Academy by the Belgians.

These ‘spill-over activities’ can be considered added value resulting from the social network established in the framework of the Force Generation Project and more specifically, the development of the POIs. The example above allowed both for the national officer academy to have students trained in urban warfare and the Belgians to test the course and the Train-The-Trainer philosophy (Van der Spiegel Citation2018, p. 30). Training both the border police and the Special Interventions Battalions with the same POIs is also beneficial for the interoperability of the Nigerien security forces. Given that many of the forces will be deployed in the same zones, these spill-over activities can also be seen as chosen opportunities that maximise the added value of the standardised approach.

While there are thus many positive aspects from the existence of spill-over activities, including the fact that training additional units may reduce internal friction between units, there is also the possibility that they will draw attention and resources away from the core activities in a resources constraint context, and thereby also undermine its effectiveness. The identification of spill-over activities is important to our understanding of the difficulties in planning, implementing and evaluating coherent strategies in SFA – something that is often pointed out as missing in the literature (Guido Citation2019; Brown and Karlin, Citation2018; Matisek and Reno Citation2019). While overarching strategies may be useful to provide clear objectives and a sense of direction, in practice, actors from both the recipient and the provider nation often stray from the initial plan to seise additional opportunities.

Conclusion

In this article I have uncovered the importance of informal networks, ad hoc encounters and personal relations in the development and functioning of SFA through a micro-level Social Network Analysis in the framework of a SOF Force Generation Project in Niger. I have focused on Belgium’s informal role as a coordinator in the development of a standardised curriculum for Niger SOF and highlighted the opportunities that present itself to locally centralised nodes/actors, both in terms of contacts and networks outside of the military sphere and with regard to, what I have called here ‘spill-over SFA activities’.

The micro-analysis has allowed for a better understanding of how SFA often evolves in a non-linear fashion strongly influenced by connections, contingency and timing. This is evident in how social networks and ties open up new opportunities in the shape of spill-over activities outside of the main focus for the Force Generation Project, like training for the gendarmerie, the border police, or the military academy. These spill-over activities are often initiated precisely because of ties and connections between key actors.

In the case of the unit commander who asked for training for his battalions even though the unit was no longer part of SOF, his demand can be explained by ties characterised by flows of equipment and information. Yet, the collaboration between the Belgian Special Forces and EUCAP in the framework of training the above-mentioned border police units may be traced back to ties of similarity between the EUCAP director and the SOFLE who share the same nationality. Similarities such as language and army size, between Niger and Belgium also help to explain Belgium’s central role in SFA, in spite of the fact that Belgium is not providing any equipment (flow). This is important for our understanding of SFA in Niger because it helps explain why some states, such as Belgium, can ‘punch above their weight’ in terms of having a seat at the table with the other providers.

Theoretically, the SNA perspective elucidates the complexity and the social dimensions that characterise cases where there are several providers in a recipient state, organised along bilateral formal structures and informal multilateral networks. Such a perspective is able to complement the overarching principal-agent analysis and give a thicker description of how relations between actors influence SFA and makes it evolve in different directions. The SNA perspective makes space for the importance of individual connections through its emphasis on interactions and similarities while taking into account the broader structure which ties into and constitute these connections. The different social connections and practices between WPNs also makes it possible to explain why providers in some cases are able to exercise a coordinated pressure on the receiver, while in other cases, when purely bilateral relations are privileged, it allows more space and flexibility for the receiver.

This micro-analysis of SFA in Niger has shown the importance of (in)formal networks, ad hoc encounters and personal relations in the planning, development and implementation of SFA. It has also underlined the bonding effect that similarities between actors can have when creating ties and developing interactions. Nevertheless, the absence of a common multilateral structure and hierarchy also make these networks fragile, meaning that they depend primarily on the chemistry and mutual understanding between individuals. Changing the personnel can thus have larger implications than expected in cases where collaboration networks are horizontal without an overarching command structure. These findings are likely to apply to other SFA cases as well. Avenues for further research thus include micro-level analysis of other case studies to establish the extent that (in)formal networks and contingency impact the development of SFA on an every-day level.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Belgian Special Operations Regiment for access and assistance, all interviewees for their time, as well as the participants of the PRIO workshop in Ghana, 2019 for comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nina Wilén

Nina Wilén is Associate Professor in Political Science at Lund University and Director of the Africa Program at Egmont Institute. She has published extensively on security force assistance and SSR in Africa amongst other. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 A node is understood as the point/an actor in a network at which lines or pathways intersect or branch.

2 New exceptions include studies by Kjetil Enstad (Citation2020).

3 MNJTF includes Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Benin and Nigeria and was reinvigorated in early 2015 to fight Islamic State West Africa Province, previously known as Boko Haram (Military Balance Citation2018, 430).

4 The G5 Sahel Joint Force was set up in 2017 and is composed by Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Chad and Niger.

5 Exact information about dates, figures and locations are difficult to obtain, yet even when such information does exist, I have deliberately avoided mentioning it because of the security risks it could imply for the different forces involved.

6 As of late 2020, female members of the Special Forces also participated in said meetings.

7 This is a simplified illustration of the main nodes in the current Force Generation Project with a focus on the Belgian Special Forces’ position and connections. It is thus highly possible that other nodes/units have similar ties that are not included in this depiction.

References

- ACLED. 2019. “Explosive Developments: The Growing Threat of IEDS in Western Niger.” 19 June. Accessed 21 August 2019. https://www.acleddata.com/2019/06/19/explosive-developments-the-growing-threat-of-ieds-in-western-niger/.

- AFRICOM. “Trans Sahara Counter Terrorism Partnership.” Accessed August, 23, 2019. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwiHh6yA2pjkAhVBbVAKHa6iA_8QFjAAegQIARAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.africom.mil%2FDoc%2F7432&usg=AOvVaw0SdSolKVWAkLW8GM24n_X5.

- Ajala, O. 2018. “US Drone Base in Agadez.” The RUSI Journal 163 (5): 20–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2018.1552452.

- Anderson, M., Sharife, K., and N. Prevost. 2020. “How a Notorious Arms Dealer Hijacked Niger’s Budget and Bought Weapons from Russia.” Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project OCCRP, 6 August. Accessed 29 September 2020. https://www.occrp.org/en/investigations/notorious-arms-dealer-hijacked-nigers-budget-and-bought-arms-from-russia.

- Baillie, C. 2018. “Explainer: the role of foreign military forces in Niger”, The Conversation, September 9. Accessed August 20, 2019. https://theconversation.com/explainer-the-role-of-foreign-military-forces-in-niger-102503.

- Biddle, S., J. Macdonald, and R. Baker. 2018. “Small Footprint, Small Payoff: The Military Effectiveness of Security Force Assistance.” Journal of Strategic Studies 41 (1-2): 89–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2017.1307745.

- Borgatti, S. P., A. Mehra, D. J. Brass, and G. Labianca. 2009. “Network Analysis in the Social Sciences.” Science 323: 892–895. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165821.

- Brown, F. Z., and M. E. Karlin. 2018. “Friends with Benefits. What the Reliance on Local Partners Means for US Strategy.” Foreign Affairs 8, May. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2018-05-08/friends-benefits.

- Burchard, S., and S. Burgess. 2019. “US Training of African Forces and Military Assistance, 1997-2017: Security versus Human Rights in Principal-Agent Relations.” African Security 11 (4): 339–369. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2018.1560969.

- Dehaene, P. 2019. “The Localization Strategy: Strategic Sense for Special Operations Forces in Niger.” CTX 9 (1): 29–38. https://globalecco.org/documents/10180/806006/CTXVol9Issue1+Dehaene+-2/d02c5f94-924a-42d7-a464-9062f0e3617c.

- Ellis, S. 2004. “Briefing: The Pan-Sahel Initiative.” African Affairs 103 (412): 459–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adh067.

- Enstad, K. 2020. “Doing One's Job: Translating Politics into Military Practice in the Norwegian Mentoring Mission to Iraq." Small Wars & Insurgencies 31 (2): 402–419.

- European Commission 2015. Final Review of the CT Sahel Project. December. http://ct-morse.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CT-Sahel-Final-review-EN-Dec-2015.pdf.

- Freeman, L. C. 2004. The Development of Social Network Analysis. Vancouver: Empirical Press.

- Furman, T. 2016. “Strategic Targeting: A Social Network Approach Across the Phases of War.” Military Operations Research 21 (4): 5–22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26296071.

- Guido, L. T. C. J. 2019. “The American Way of War in Africa: The Case of Niger.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 30 (1): 176–199. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1554337.

- Harkness, K. 2015. “Security Assistance in Africa: The Case for More.” Parameters 45 (2): 13–24. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00062677/00010.

- Karlin, M. 2017. “Why Military Assistance Programs Disappoint.” Foreign Affairs, 16 October. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2017-10-16/why-military-assistance-programs-disappoint.

- Karlshoej-Pedersen, M. 2018. “’Light Footprint’ Operations Keep US Troops in the Dark.” Defense One. 5 October. Accessed 19 August 2019. https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2018/10/light-footprint-operations-keep-us-troops-dark/151797/?oref=d-river.

- Kelly, F. 2019. “German Parliament Extends Africa Military Missions.” The Defense Post. 10 May. Accessed August 21, 2019. https://thedefensepost.com/2019/05/10/germany-deployment-extended-mali-niger-somalia/.

- Knoke, D., and S. Yang. 2011. Social Network Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Knowles, E., and J. Matisek. 2019. “Western Security Force Assistance in Weak States.” The RUSI Journal 164 (3): 10–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2019.1643258.

- Knowles, E. and A. Watson. 2018. “No such thing as a quick fix. The aspiration-capabilities gap in British remote warfare.” Oxford Research Group, Remote Warfare Programme, London.

- Larsdotter, K. 2015. “Security Assistance in Africa: The Case for Less.” Parameter 45 (2): 25–34. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00062677/00010.

- Lebovich, A. 2017. “The Real Reason U.S. Troops are in Niger.” Foreign Policy. 27 October. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/10/27/the-real-reason-u-s-troops-are-in-niger/.

- Mamane, D. 2020. “Niger’s Army Accused in Disappearance of 102 Civilians.” The Washington Post. 5 September. Accessed 29 September 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/nigers-army-accused-in-disappearance-of-102-civilians/2020/09/05/fc7a4c36-ef7f-11ea-bd08-1b10132b458f_story.html.

- Matisek, J. and W. Reno. 2019. “Getting American Security Force Assistance Right. Political Context Matters”. Joint Force Quarterly 92: 65–73, 1st Quarter. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-92/jfq-92.pdf.

- Military Balance. 2018. International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

- Mische, A. 2011. “Relational Sociology, Culture and Agency.” In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, edited by Scott, J. & P.J. Carrington, 80-99. London: Sage.

- Morgan, W. 2018. “Behind the Secret U.S. War in Africa.” Politico. 2 July. Accessed 18 August 2019. https://www.politico.com/story/2018/07/02/secret-war-africa-pentagon-664005.

- Penney, J., 2018. “The ‘Myths and Lies’ behind the U.S. Military’s Growing Presence in Africa.” World Politics Review, June 19. Accessed 1 August 2019. https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/myths-and-lies-behind-us-militarys-growing-presence-africa-0.

- Raffey, N. 2017. “Operation NABERIUS: The Canadian Forces’ Role in Combating Boko Haram”. NATO Association of Canada, 27 March. Accessed August 9, 2019. http://natoassociation.ca/operation-naberius-the-canadian-forces-role-in-combating-boko-haram/.

- Rittinger, E. 2017. “Arming the Other: American Small Wars, Local Proxies, and the Social Construction of the Principal-Agent Problem.” International Studies Quarterly 61 (2): 369–409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx021.

- Rolandsen, Ø. H., M. Dwyer, and W. Reno. 2021. “Security Force Assistance to Fragile States: A Framework of Analysis.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 15 (5): 563–579. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2021.1988224.

- Scott, J. 1987. Social Network Analysis. A Handbook. London: Sage Publications.

- Smirl, L. 2016. “’Not Welcome at the Holiday Inn’: How a Sarajevan Hotel Influenced Geo-politics.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 10 (1): 32–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2015.1137398.

- Turse, N. 2018. “US Military Says it has a “Light Footprint’ in Africa. These Documents Show a Vast Network of Bases.” The Intercept, 1 December. Accessed 5 August 2019. https://theintercept.com/2018/12/01/u-s-military-says-it-has-a-light-footprint-in-africa-these-documents-show-a-vast-network-of-bases/.

- UN Human Development Index. 2020. Accessed 26 July 2021. http://hdr.undp.org/en/data.

- US Department of State. 2017. “Security Governance Initiative (SGI) 2017 Review.” Accessed 23 August 2019. www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=%E2%80%9CSecurity+Governance+Initiative+%28SGI%29+2017+Review%E2%80%9D#.

- Van Der Spiegel, T. 2018. “Belgian SF Gp Localization Strategy and the Human Domain (HD). Special Warfare and applied Strategic Tactics - Niger.” Internal Document, Belgian Defense.

- Watson, K. 2017. “Where Does the US Have Troops in Africa, and why?” CBS News. 23 October. Accessed 28 January 2020. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/where-does-the-u-s-have-troops-in-africa-and-why/.

- Watts, S. 2015. Identifying and Mitigating Risks in Security Sector Assistance for Africa's Fragile States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Watts, S., C. Baxter, M. Dunigan, and C. Rizzi. 2012. The Uses and Limits of Small-Scale Military Interventions. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Wilén, N. 2013. “Tintin is No Longer in the Congo”. Royal Military Academy. Accessed 27 January 2020. https://issat.dcaf.ch/Learn/Resource-Library/Policy-and-Research-Papers/Tintin-is-no-longer-in-the-Congo-A-Transformative-Analysis-of-Belgian-Defence-Policies-in-Central-Africa.

- Wilén, N. 2018. “Examining the Links between Security Sector Reform and Peacekeeping Troop Contribution in Post-Conflict States.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (1): 64–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1426680.

- Wilén, N. 2019. “Belgian Special Forces in the Sahel: A Minimal Footprint with Maximal Output”, Egmont Institute, Africa Policy Brief, n°26. May.

- Wilén, N. and P. Dehaene. 2020. “Défis de l’assistance aux forces de sécurité: comprendre le contexte local et harmoniser les intérêts.” Observatoire Boutos-Ghali du Maintien de la Paix. July 2020.

Internal Documents

- “BEL SOFLE COS Force Generation project”. 2018. Belgian Defense.

- “Sovereignty and Complexity: SOF Strategic Sense in the Sahel”. 2018. Belgian Defense.

- “The SOFLE’s 3D Networking”. 2018. Belgian Defense.

- “White Paper Niger: Sovereignty & Complexity: Strategic Sense for SOF Operations in Niger”. 2018. Belgian Defense.