ABSTRACT

Why have population monitoring, migration control and surveillance become a significant area of common ground in EU-African migration cooperation? This article examines the securitisation of borders in the West Africa region. It finds that state actors in Senegal and Ghana perceive the technocratic solutions that arise from this cooperation as useful in attaining domestic governance and statebuilding goals, and have presented the ECOWAS regional integration agenda and border securitisation project as congruent. This article proposes that the depoliticised nature of security cooperation, alongside specific features of the domestic policymaking contexts, allows the circumvention of domestic critique of securitisation.

Introduction

Security has formed a core component of the EU’s migration cooperation with African and other non-EU countries, where the EU’s two-pronged approach in external migration governance emphasises both security and development elements in its policies and interventions in targeted countries (Boswell Citation2003). This dual focus on security and development is formally reflected in the EU’s approach since the introduction of the Global Approach to Migration and Mobility (GAMM) in 2005. Contextually, the management of the EU’s external borders also increasingly takes place in locales far removed from Europe, extending from the EU’s traditional geopolitical neighbourhood of North Africa into the ‘hinterlands’ of sub-Saharan Africa (Del Sarto Citation2009). In this process of ‘externalising’ the EU’s borders, African governments are heralded as partners in a form of management where traditional, overt relations of force are avoided in favour of a narrative of harmonious cooperation (Collyer Citation2016). By drawing on a discourse of ‘win-win’ scenarios and ‘partnership’, European policymakers have presented the idea that migration is best ‘managed’ to yield benefits, and that interests in migration control are common to European and African stakeholders (Kunz and Maisenbacher Citation2013; Lavenex and Kunz Citation2008). As a result, the EU, with a degree of success, has attempted to reduce the porosity of West African borders and has advanced an agenda of migration control and surveillance.

While the advancement of migration control, security rationales, and border management capacity-building in the Sahel has been well documented in the existing literature (see e.g. Aguillon Citation2018; Cross Citation2013; Frowd Citation2018; Sandor Citation2016; Van Dessel Citation2021), how political actors in African states have positioned themselves in relation to such migration governance ideas, and their possible motivations for participating in this capacity-building, is less clear. At the outset, these ideas appear largely ‘external’ to a region where migration as a practice has a long history, and the regional integration agenda under the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is considered the most developed on the continent (Lavenex and Piper Citation2021; Idrissa Citation2019). However, West African states also invoke security narratives on a strategic and ad-hoc basis to assert their own borders and statehood. This has for instance resulted in deportations between West African states, both historically and in contemporary times.

Recent scholarship has sought to address this gap in understanding the ambitions and strategies of third country governments in furthering security policy development. This has helped to bring to the foreground the perceptions and strategies of domestic political actors that have formed in response to external proposals, agendas, and funding. Contributions to this literature have shown how local authorities play a crucial role in determining whether potential conflicts between actors’ positions are either highlighted or avoided (Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn Citation2020), and in ‘localising’ external ideas or norms to local sensitivities (Cassarino Citation2018b). They argue against depicting domestic actors as necessarily resisting or subverting international security norms in a simple binary narrative that sees securitisation as something that the ‘West has done to Africa’ (Fisher and Anderson Citation2015, 132; see also Moe and Geis Citation2020). In Lebanon, Tholens (Citation2017) demonstrated that domestic security actors exercised agency in cooperation dynamics by making use of a vast network of diplomatic liaisons to ensure the flow of security assistance. Similarly, Sandor (Citation2016) demonstrated that political and security elites in Senegal have exploited longstanding social and economic connections with European and North American partners to convince international actors to fund Senegalese security capacity-building. Fisher and Anderson’s (Citation2015) analysis of regimes in Chad, Uganda, Rwanda, and Ethiopia concluded that there is an active pursuit of securitisation by these governments – belying the notion of African state actors as subordinates to a western security agenda.

This article examines West African domestic interests in securitisation and contributes to the growing body of literature that examines the preferences, interests, and strategies of state actors in (West) Africa when they engage with external actors in migration governance (see Adam et al. Citation2020; Chou and Gibert Citation2012; Mouthaan Citation2019; Reslow Citation2012; Zanker Citation2019). In particular, the article considers: how do inherent features of security cooperation and migration management remove domestic barriers to pursuing this form of cooperation? These features include the deeply technocratic and depoliticised nature of security cooperation; that it operates in a sphere ‘above’ domestic politics due to its transnational nature; and that, with the exception of border communities where the border ‘spectacle’ is played out (see e.g. Carlotti Citation2021), it enjoys low visibility among local communities. This stands in contrast to other areas of EU-African migration cooperation, such as cooperation on migrant returns and readmission, where it has been shown that West African states are primarily interested in preventing deepened cooperation with the EU on return and readmission agreements. Enhanced cooperation on migrant returns is for instance typically poorly aligned with West African states’ domestic interests, highly visible in communities, and subject to potentially significant domestic contestation (Maru Citation2021; Mouthaan Citation2019; Stutz and Trauner Citation2021).

The core empirical contribution of this article consists of two parts. Firstly, the article analyses the specific ways in which West African state interests in border management and security have points of alignment with the border securitisation agenda advanced by the EU, using Senegal and Ghana as case studies. It explores how African governments have tangible reasons to leverage international migration and security concerns over the Sahel’s porous borders. Secondly, the analysis delves into aspects of the domestic policy-making contexts in Senegal and Ghana, and how actors perceive and negotiate potential constraints in decision-making. While there has been a domestic critique of securitisation among non-state actors (NSAs) and in particular some civil society organisations (CSOs), NSAs face various challenges in accessing decision-makers in government, and their efforts have largely failed to re-orient government policy or to prevent deepened cooperation in this area. Senegalese and Ghanaian policymakers instead balance commitments to regional integration and mobility within the ECOWAS region with increasing securitisation. I contend that state actors take advantage of a relative absence of constraints to present the ECOWAS integration agenda and the securitisation of borders in the ECOWAS region as congruent. The apparent congruence of two different narratives is nonetheless not a given – rather, this congruence is co-constructed by African civil servants undertaking day-to-day tasks within government bureaucracies.

The case study selection of Senegal and Ghana reflects both countries’ significant engagement with the EU and EU Member States in migration governance initiatives, where Senegal in particular has been a key beneficiary of funding for migration projects under the EU’s Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (launched in 2015). In addition, both countries are ECOWAS Member States and are active in regional governance platforms and dialogues. Both countries remain aid-dependent but have a reputation for achieving political and economic reform and maintaining political stability – and have been preferred recipients of international aid.

The analysis draws on fieldwork conducted at three sites: Brussels, Dakar, and Accra. Forty-two semi-structured interviews were conducted in 2017–2018 with officials at the EU Delegations in Dakar and Accra; Senegalese and Ghanaian civil servants (in particular officials based in the respective Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Interior, but also other ministries involved in aspects of migration governance); EU project implementers (both in field offices and in Brussels); International Organization for Migration (IOM) staff; representatives of civil society organisations in Senegal and Ghana, including migrant associations; a senior EU Member State diplomat involved in the Rabat ProcessFootnote1; and Senegalese and Ghanaian epistemic communities. These interviews were conducted as part of a larger research project that focused more broadly on aspects of the EU’s migration cooperation with Senegal and Ghana. Interview data used in this article was selected according to insight afforded into the interests, perceptions, and strategies of domestic actors (state and non-state) in Senegal and Ghana within EU-African migration-focused security cooperation. A further ten interviews were conducted with officials working at EU institutions and agencies in Brussels (the European External Action Service, and European Commission Directorate-Generals) in a migration policy capacity: although these informed the wider research project, they are not directly included in this article’s analysis.

Interviewee selection was purposeful, where interviewees were selected against the criteria of being involved in a professional capacity in EU-African migration cooperation, or in development projects relating to migration or migrants. A combination of snowball sampling and criterion sampling was used, and participant data was anonymised to protect the identity of participants. Interview transcripts were thematically coded and analysed using Atlas Ti, where an initial round of codes was revised and re-grouped into fewer themes in subsequent rounds of coding. Policy documents are also used in the analysis, in particular the National Migration Policy (NMP) documents of both case studies. The Senegalese NMP document is not currently available online but was obtained during fieldwork from the Senegalese Ministry of Finance.

The next section lays out the underpinning theoretical rationale. The subsequent sections lay out the historical context of migration and migration governance in the region and case study countries, and the empirical analysis detailed above. The concluding discussion reasserts the relevance of a closer examination of domestic actors’ interests, opportunities, and constraints in scholarship on EU-African migration cooperation.

Conceptualising migration and security frameworks in Africa

The analysis builds on scholarship that considers the rationales of African states when engaging proactively and strategically with external actors and donor-driven agendas, and in particular statebuilding incentives. This includes Bayart’s theory that sub-Saharan political actors ‘compensate for their difficulties in the autonomization of their power’ by making recourse to the resources found in the external environment in strategies of extraversion (Bayart and Ellis Citation2000, 218). The re-emergence of the state as the preferred ‘partner’ of international donors since the 1990s (Fisher and Anderson Citation2015) has similarly created opportunities for the securitisation of development to strengthen the capacity, reach, and power of the state in both authoritarian and democratic African states. The securitisation of migration policies in North and West Africa is thus closely linked to African state actors’ interests both in the economic and material benefits that can be derived from such cooperation (including military assistance, technical equipment, and financial support), but also immaterial benefits (regime legitimacy, territorial integrity) (Cassarino Citation2018b; Andersson and Keen Citation2019). As Whitfield and Fraser (Citation2010, 352) have argued, African governments have developed implicit strategies for negotiating aid in their efforts to achieve the most favourable outcome in terms of maximising funding and policy autonomy.

The dynamics of securitisation in countries reliant on donor funding, and characterised by a weak administrative capacity, differ in some ways from securitisation in non-aid dependent countries. For instance, the inclusion of such a lens in policy agendas in African countries can be seen as a performative act of ‘rhetorical mirroring’ (Zanker Citation2019), catering to external donors’ appetite for security cooperation and representing, at its core, an effort to achieve leverage in an asymmetric EU-African relationship. Aid-recipient states are also more likely to approach migration governance as an ‘intermestic’ issue – i.e. situated between foreign and domestic interests (Adam et al. Citation2020).

Power gains in relations with donors and statebuilding ambitions are therefore a potentially significant factor that shape African state actors’ interests – and subsequent active participation – in EU and international migration cooperation. The technocratic nature of migration management is of particular appeal to these actors who often perceive technological solutions as appropriate in solving domestic governance challenges. Domestic policymakers may be keen, for instance, to modernise systems within the state apparatus and bring these in line with international standards. The strong and sustained external interest in providing resources and other capacity-building support for security capacity-building also offers opportunities for domestic security and political elites to bolster their mandate and expand their activities by exploiting donor interest. As a weak administrative capacity is a feature of Senegalese and Ghanaian administrations, opportunities to expand state power and control over domestic populations can constitute a significant incentive to engage.

Security knowledge has also been argued to be driven and perpetuated according to a particular worldview: one which places normative value on the Westphalian notion of statehood, and where ‘successful’ governance is construed as territorial control and a good visibility of the population (Little Citation2007; Frowd Citation2018; Waltz Citation1979). Accordingly, territorial control and population visibility may be perceived as standards to emulate. International relations scholars and sociologists have argued that emulation may appeal to states because doing so confers legitimacy: in emulating what is perceived as successful practice elsewhere, actors reduce uncertainty and complexity in their policy choices in a process of ‘mimetic isomorphism’, or ‘lesson drawing’ (Börzel and Risse Citation2003; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2004; Powell and DiMaggio Citation1991). Security narratives also confer legitimacy on a state in performing its function of protecting its citizens from threats, whether real or constructed (Bigo Citation2002; Huysmans Citation2006).

Finally, by examining the broader historical context of migration and its governance in the West African region, the analysis draws on studies that have taken steps to contextualise migration policies within processes and situated histories such as colonial experiences and postcolonial state formation, nation-building, development histories and structural dependency: something that has not been regularly or systematically done in theories of migration that have emerged largely from Europe and North America (Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2020; Gazzotti, Mouthaan, and Natter Citation2022; Sadiq and Tsourapas Citation2021). Recent empirical studies of African states’ domestic agency in security cooperation have begun to address this gap, examining, for instance, specific domestic policy and/or geopolitical interests such as in Niger and Mauritania (Frowd Citation2014), Senegal and Ghana (Adam et al. Citation2020), and Tunisia (Natter Citation2021). This historical contextualisation is important in understanding domestic policy contexts – and the statebuilding ambitions of West African governments.

Technocratic and depoliticised migration management

In exploring state actors’ perceptions of opportunities and constraints, I also examine the implications of a managerial type of migration governance that emphasises technical considerations (rather than political choices) around migration policies, and the routinisation of migration control practices (Geiger and Pécoud Citation2010; Maertens Citation2018; Pécoud Citation2015). These characteristics effectively serve to depoliticise migration governance practices and hide them from public scrutiny and eventual contestation. In some areas of migration cooperation, a strategy of depoliticisation is difficult to enact, such as in the case of forced returns; however, efforts are still made to render cooperation less obvious. This is evident in the increasing use of informal arrangements to conduct returns that are less visible to European and African audiences (Cassarino Citation2018a).

Different schools of thought have produced theories to conceptualise the building of migration-security links. Critical security scholars have examined the forging of these links in the case of Western politics, analysing the framing of immigration to the Global North as a challenge needing security-oriented solutions (see Bigo Citation2002; Huysmans Citation2006; van Munster Citation2009). The Copenhagen School proposed that mechanisms of securitising migration necessitate the constructing of migration as a security threat through performative acts that elevate political discourse on migration to the realm of the ‘exceptional’. This allows for restrictive policies to be implemented that may not in other circumstances be accepted as legitimate. In comparison, work in critical border studies sees the security rationale as perpetuated by technocratic processes, emphasising the role of technocratic management and surveillance technologies therein, as well as the everyday practices of non-state security actors who ‘perform’ borders (Boswell Citation2007; Neal Citation2009; Raineri Citation2021). These two logics of securitisation are often presented as conflicting, although the divide may be somewhat artificial: elements of ‘exception’ and ‘routine’ can and do operate simultaneously (Bourbeau Citation2017). Finally, the often highly transnational nature of security cooperation can act as insulation from domestic societal pressures, and domestic actors may also perceive the opportunity to extract legitimacy from ‘outside’, rather than from the domestic sphere.

In sum, these are characteristics that distinguish migration management as a field of migration governance. The literature considers how depoliticisation is an attractive strategy for international organisations (Geiger and Pécoud Citation2010; Maertens Citation2018) and the EU (Cassarino Citation2018a) in migration governance. However, less is known about how political and security actors in African democracies may find these characteristics useful, such as in deploying (de)politicisation as a strategy to circumvent eventual domestic opposition or overcome institutional constraints to migration cooperation.

Historical context: migration and its governance in the West African region

As a practice, migration has a longstanding history in the West African region. Trans-Saharan trade routes were well established in pre-colonial times, dating back to the 6th century (Bakewell et al. Citation2009; Walther and Retaillé Citation2008). In the precolonial era, West Africans migrated for diverse reasons including pastoralism, employment, commerce and evangelisation; but also as a result of natural disasters and warfare (Adepoju Citation1995). Following independence, relatively prosperous countries such as Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire attracted large numbers of migrants from the region. While Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Nigeria were major migrant-receiving nations, buoyed by their economies, countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, Togo, and Cape Verde remained labour exporting countries. Senegal was both a migrant-receiving and a labour exporting nation. Shifting economic and political conditions engendered changes whereby both Senegal and Ghana would increasingly become countries of emigration. In Senegal, the fall in the global price of groundnut oil was a blow to the Senegalese economy and altered the country from an immigration nation to a nation largely of emigration after 1975 (Cross Citation2013). Remittances from Senegalese migrants abroad gained in importance as a source of income with the onset of several factors as of 1994: the devaluation of the CFA franc, the hike in petrol prices, and the collapse of agricultural sectors. Although international, extra-regional migration flows became more common, these were (and remain) of a much smaller scale than migration within the region (Black, King, and Tiemoko Citation2003).

Efforts to shape West African migration flows also have a long history. Colonisation led to the construction of the ‘modern nation’, while also introducing a distinction between ‘internal’ and ‘international’ migration (this distinction did not exist for pre-colonial African institutions) (Akin Aina Citation1995, 41). Efforts to control African mobility date back to the colonial era, where colonial systems of tax collection and law imposition relied on knowing individuals’ whereabouts (Bakewell Citation2008).

Despite their apparent external origin, restrictive migration policies have also been deployed selectively by West African governments in the management of their relations with states in the wider region. Post-independence, West African nascent states adopted policies to encourage migration, but also conducted expulsions of migrants in times of political and economic turmoil. The Ghanaian government introduced the Aliens’ Compliance Order in 1969 which resulted in mass expulsions of undocumented immigrants in Ghana: citizens of Nigeria, Togo, and Benin were among those affected, with estimations that half a million were expelled (Adepoju Citation1983; Peil Citation1971). These expulsions were conducted in a climate where migrants were scapegoated for a deteriorating economic situation (Bakewell et al. Citation2009). Other African countries can also be seen to have practiced deportations – Senegal, for instance, expelled Guineans in 1967 (Adepoju Citation1983). Expulsion remains a tool that African states deploy: although expulsion en masse is prohibited by the 1979 ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, large numbers of ECOWAS migrant workers were expelled from, for instance, Nigeria in the 1980s, and from Côte d’Ivoire in the run-up to the 2000 presidential elections (Awumbila et al. Citation2014).

Alongside these ad-hoc shifts in national migration governance strategies – that largely reflect dynamics of domestic politics, and the role of political elites therein – regional integration agendas also feature as a significant, historical development in West African migration governance. In 1979, with the intention of fostering deeper regional integration, the ECOWAS regional body introduced rules aimed at facilitating the mobility of citizens across the Member States. This established free movement within the bloc, as well as the right to reside in other ECOWAS countries. The ECOWAS States agreed in 1979 to the simplification of administrative procedures at border posts and the reduction in the number of checkpoints (Adepoju Citation2009; Coderre Citation2018).

The free movement of persons within the region is thus a cornerstone of a regional integration policy that many West African states have subscribed to. However, the implementation of the 1979 ECOWAS protocol has been fraught with challenges, including reports of discrimination and refusal of admission for arbitrary reasons; demands for bribes from border officials and harassment at borders; a lack of harmonised immigration procedures and documents; and a limited knowledge among both immigration officials and the general public of the ECOWAS free movement protocol (Awumbila, Teye, and Nikoi Citation2018; Teye, Awumbila, and Benneh Citation2015). Indigenisation policies are implemented by African countries with the stated aim of protecting jobs from immigrants. With expulsions still forming common practice, and the expansion of strict border control practices, the free movement of people within the region is thus regularly impeded (Awumbila et al. Citation2014).

With the consolidation of partnerships between European and West African actors on migration cooperation since the early 2000s, a security focus features more prominently in West African regional policy agendas on migration (Coderre Citation2018; Kabbanji Citation2011). The accommodation of security goals alongside a regional integration agenda – purporting to both control and ease movements across borders – has been argued to potentially undermine regional integration plans in countries such as Nigeria (Arhin-Sam and Zanker Citation2019). It also potentially ‘re-legitimizes policy approaches that the ECOWAS protocol had de-legitimized’, such as rigid borders and mass deportations reminiscent of independence era policies, instead of promoting the removal of obstacles to freedom of mobility – something that has been integral to the ECOWAS regional integration project (Idrissa Citation2019, 14).

National policy frameworks in Senegal and Ghana also increasingly reflect a dual focus on facilitating mobility, and securitising borders. For instance, Coderre (Citation2018) highlights a clear ambiguity in the Senegalese law 2016-09 introducing the biometric ID card, intended to simultaneously facilitate mobility within the ECOWAS region, and serve as a tool in counter-terrorism measures. This dual focus is indicative of a broader trend in policy discourse: a pre-existing, West African regional integration agenda that advocates the removal of formal and informal obstacles to mobility; and ongoing security capacity-building.

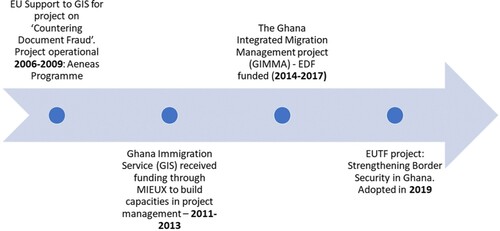

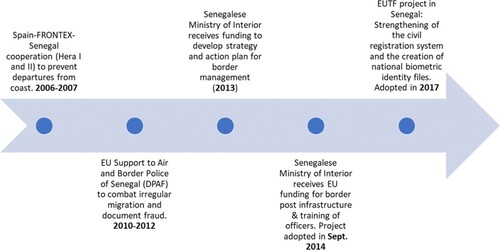

In both Senegal and Ghana, state actors have extensively engaged with the EU and EU Member States in the area of border management, documenting migration, and – especially in the case of Senegal – population registration and documentation by establishing a functioning civil registry. and represent some of the key projects on border management capacity-building that have taken place since the introduction of the EU’s GAMM in 2005 (while emphasising that this is not an exhaustive list).

Figure 2. Projects in Senegal since 2006. Sources: author’s compilation; EEAS Citation2017; IOM Citation2017.

A historical lens illustrates that African state actors have often adopted restrictive migration policies, for example when it is politically expedient. While the ECOWAS integration agenda provides an imperative to remove obstacles to mobility, it is hampered by multiple implementation challenges. The next sections delve into the specific gains that Senegalese and Ghanaian state actors perceive in security capacity-building.

Governance, monitoring, and reputational gains

African policymakers are interested in forms of cooperation with the EU that add to their own governance toolbox. Expanding documentation on the population, in the form of a comprehensive civil registry, was identified in the Rabat Process as being of interest to African partner countries. Reliable civil registries in African countries provide EU states with a mechanism to identify undocumented migrants in Europe; however, they are also ‘essential to countries who want to build their economy and have a political, demographic and democratic governance’ as observed by an EU Member State diplomat.Footnote2

With a budget of 28 million euros, the EU Trust Fund project supporting the creation of a civil registry in Senegal constitutes one of the Fund’s most significant project interventions in the country (EC Citation2019). Senegalese state actors across various ministries welcomed the initiative. An interviewee working in the diplomatic branch of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Senegalese Abroad (MAESE) was enthusiastic about the EU’s support in this domain, emphasising that a key concern for the state is the ‘massive document fraud’ that takes place in the country, which in turn is closely linked to the issue of an unreliable civil registry.Footnote3 The Senegalese and Ghanaian NMPs both stress the need for a system of reliable documentation on the resident population, including immigrants (Ghanaian NMP 2016, 46; Senegalese NMP 2017, Art. 226). For Ministries of Interior, the introduction of biometric databases facilitates their ability to carry out activities in line with their mandate to manage entry and exit to Senegalese and Ghanaian territories, as well as monitoring the resident population.

The issue of a reliable civil registry is closely linked to the larger question of limited data and statistics on migration in both countries. A senior official at the Ghanaian Ministry of Interior identified data collection to be a key issue in governance, citing an absence of official statistics on how many Ghanaians reside abroad, or an idea of how many migrate irregularly.Footnote4 A civil society representative felt that it was ‘inconceivable’ that a ‘migration state’ such as Senegal lacks reliable migration data, and instead relies heavily on the IOM for migration statistics: the reliance on an external actor for data to inform government policy is perceived by domestic actors as a sovereignty issue.Footnote5 Collected data is often not harmonised in a way that would enable comparison or meaningful analysis; in other cases, data is not shared between ministries and institutions.Footnote6 A senior official at the Senegalese Air and Border Police (DPAF) noted that one of the agency’s goals was to create a profile of migrants travelling outside of Senegal, which would require increased data collection on travel, and improved information sharing between police services.Footnote7 The problem of limited data on migration is reflected in the Senegalese NMP, which notes that the available data is fragmented, and collected on an ad-hoc basis. This makes it difficult to ‘observe the evolution of the migratory phenomenon over time’, with the current system of data collection on migration being perceived as inadequate to reliably inform decision-making in government (Senegalese NMP 2016, 16). In Ghana, the IOM has introduced data harmonising and sharing tools with the aim of contributing to more effective migration management and monitoring migration trends.Footnote8

The EU has thus far funded virtually all that is ‘biometrics’ in Senegal.Footnote9 Ultimately, advances in biometry serve to improve the ‘traceability’ of persons, including those on the move. MAESE’s diplomatic branch deals with requests for identifications of Senegalese irregular migrants, and with the rolling out of a biometric ID card system, the ministry anticipates that identification missions will become easier, thus serving as a potentially useful tool to block return orders issued by EU Member States in cases of (incorrect) assumption of Senegalese citizenship.Footnote10

Ministries thus perceive technological modernisation and increased access to reliable data as useful in addressing issues of domestic governance, and sovereignty concerns. The political choice of pursuing technological solutions for domestic governance issues also has reputational ends, as institutionalised techniques help to establish an organisation as ‘appropriate, rational and modern’ (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977, 344). The Senegalese NMP (2017) notes, for instance, that Senegal’s manual databases are ‘globally obsolete’ and in need of modernisation (Art. 78). Reputational gains that set the country apart from others in the region act as an incentive: that Senegal is the first ECOWAS country to launch the ECOWAS biometric ID card establishes the West African nation as a forerunner in the region, something that interviewees across ministries were keen to highlight.Footnote11

The rolling out of a national biometric ID card is also a priority of the Ghanaian administration, although Ghana and Nigeria have preferred to develop their own ID card independently of the ECOWAS model.Footnote12 Technological advances in biometry thereby assist state actors in modernising governance mechanisms and bringing these in line with international standards, capable of dealing with the challenges of document fraud and other governance challenges linked to a weak civil registry.

Building institutional capacity within the state apparatus

In addition, a wide array of donor funding offers West African state actors various opportunities to source funds for institutional capacity-building. Over time, domestic security actors have capitalised on these opportunities, becoming adept at navigating and accessing the multiple external funds available to them, and tailoring interventions to their own strategic priorities.

In the case of both Senegal and Ghana, national actors have proactively requested support from EU and international partners to build capacity in border management and border surveillance. The EU’s Migration EU Expertise (MIEUX) initiative supports requests for technical assistance from partner countries and regional organisations in all four areas of the thematic pillars of the EU’s GAMM. A request was received from the Senegalese Ministry of Interior after which a project was launched in 2010 to develop the national border management strategy for Senegal.Footnote13 Another MIEUX project implemented in Senegal from 2010–2012 focused on combatting irregular migration and document fraud, with the project request made by the Senegalese DPAF in coordination with police and immigration departments of several other West African states. Ghanaian ministries placed three successful requests for technical assistance with MIEUX. Of these three requests, one was made by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and two by GIS and the Ministry of Interior.Footnote14 The two requests made by GIS demonstrated a strong interest in institutional capacity-building – with one in particular focusing on building the agency’s project management capacity, in light of the many projects it had already secured.

GIS (and more broadly the Ministry of Interior of Ghana) has seen its capacities significantly expanded through cooperation with the EU, as evidenced by flagship projects such as the GIMMA project.Footnote15 A senior official based in the Migration Information Bureau of GIS noted that the agency had enjoyed ‘good relations with the EU’ and that this had resulted in the implementation of many projects during the interviewee’s time at GIS (since 2004).Footnote16 GIS has also enjoyed ongoing bilateral funding, with individual EU Member States involved in supporting the development of particular areas of the GIS’s capacities (for instance, the Netherlands financed the training of Ghanaian officers in detecting document fraud).Footnote17 An official dealing with EU relations within the Ghanaian Ministry of Foreign Affairs perceived that GIS had built a strong working relationship with the EU, and had done so more successfully than other entities of the Ghanaian government.Footnote18 A migration academic in Ghana similarly commented that while EU support extended to different government agencies, the capacity-building of GIS stood out in particular.Footnote19 In Senegal, cooperation with the Senegalese Ministry of Interior led to the inauguration in late 2017 of a series of border posts as part of the EU-funded Projet d’appui à la gestion des frontières that aims to further build the capacities of the Senegalese Police, Gendarmerie, and Customs (EEAS Citation2017). Equally, the Senegalese DPAF has seen its capacities expanded through cooperation on migration management with Spain (where this cooperation effectively terminated all migrant departures from the Senegalese coastline).Footnote20

In comparison, there has been more limited institutional capacity-building within other ministries involved in migration governance. This is the case for instance for the Ministry of Labour in Ghana, whose budgetary constraints affect its capacity to effectively regulate the informal recruitment of Ghanaian nationals to Middle Eastern countries (and to address human rights infringements); and to negotiate labour exchange agreements. Institutional weakness is cited as at least one reason why an agreement on the exchange of labour between Ghana and European countries has not been forthcoming, with an interviewee at the EU Delegation in Ghana noting that the lack of a ‘proper institutional structure’ hampered the ministry’s ability to negotiate such agreements.Footnote21 The securitisation of Senegalese and Ghanaian migration policies appears to be linked to the relative success of select ministries and agencies in building their institutional capacity through strong networks with external donors – and through donor interest in selectively building capacity within the Senegalese and Ghanaian state apparatus.

Regional integration agendas and securitisation

West African state actors thus have statebuilding interests in security cooperation with external partners, and perceive opportunities to expand their institutional capacity through tailored relationships with European counterparts. Yet, how do domestic policy actors perceive, on the one hand, their commitments to facilitating mobility within the region, and on the other hand their activities in expanding security cooperation? An increasing commitment – both at the national and regional level – to the management of migration (controlling and monitoring legal migration, and repressing irregular migration) can be said to overshadow the ECOWAS protocol on freedom of movement (Idrissa Citation2019). There is, however, evidence of a lack of political will among state actors to fully implement the protocol: for instance, Castillejo (Citation2019, 22) points to power dynamics, tensions and lack of trust between the ECOWAS Member States, and concerns about the economic impact of full implementation. This can be exacerbated by the large economic and labour market disparities between ECOWAS countries, and concerns about large influxes of immigrants from the region. I examine the question above with reference to the 1979 ECOWAS protocol, including the subsequent commitment of ECOWAS states to reduce administrative controls and border points, and to coordinate on the eradication of formal and informal obstacles to mobility and integration in the region.

Interviewees in Ghanaian and Senegalese ministries, and particularly the ministries of Interior, largely presented the expansion of border controls as congruent with the free movement protocol of ECOWAS. One prominent argument was that monitoring entry and exit has always been a feature of the ECOWAS ‘borderless’ regime, as described by a project manager at the IOM in Ghana: ‘ECOWAS is seeking to ensure that we operate the borderless system. But that does not take away border management. You need to ensure that even though it is borderless, you know who is coming in and going out’.Footnote22 A senior official at the Senegalese DPAF noted that free movement within the bloc is enshrined, but similarly reiterated that movement should take place with a valid ID document; this argument was echoed by an interviewee in Ghana Immigration Service.Footnote23 The DPAF officer asserted that alongside citizens’ right to free movement, states also have a right and duty to control borders, observing that the politics around this ‘adapt’ accordingly.

This interpretation is not necessarily shared across ministries and agencies. While one civil servant at the Europe Desk, Ghanaian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, agreed that ‘well managed’ migration was perfectly in line with the government’s aims and commitments, another interviewee highlighted the ministry’s preference for adopting a regional approach in a way that ‘[looks] at security’ in conjunction with other issues: ‘They are two sides of the same coin: if you address the security but you do not address the other side, then you may not achieve the desired result. We prefer a more holistic approach to the issue’.Footnote24

As major countries of immigration in the region, relations with immigrant populations also arose as a domestic policy concern that made migration management policies appealing. In Ghana, academic consultants involved in the drafting of the Ghanaian NMP attributed concerns around important influxes of Nigerian immigrants to the country to the initial strong focus on securitisation within the policy document. As one of the consultants noted: ‘Nigerians were beginning to move a lot into Ghana – Nigerians [were blamed] for all of Ghana’s woes’.Footnote25 The Ghanaian NMP also refers to tensions regarding the nomadic Pastoralists (Fulani) that move cattle for pasture through Ghana, resulting at times in violent conflicts between Fulani and locals. The ‘management’ of these nomadic peoples is described in the NMP as a major challenge, alongside the absence of strategies to systematically register this population and monitor their activities.

In Senegal, the integration of ECOWAS immigrants in the country in line with national and ECOWAS legal frameworks promoting the right to establishment was considered by NSAs as an issue that the government had failed to adequately address. Several interviewees – based in European NGOs in Senegal, and Senegalese civil society actors – stated that integrating informal immigrant populations from the wider region was a low migration policy priority for the Senegalese government, with many such populations unable to access services in Senegal to which they were otherwise entitled to.Footnote26 The Senegalese NMP reaffirms the country’s reputation as one of ‘hospitality’ to immigrants, and to safeguarding immigrant rights. However, it also acknowledges that the lack of updated national legislation since 1971 concerning the entry, stay and establishment of immigrants on Senegalese territory is problematic, and remains an issue that the government has been slow to address.

Domestic critique

There has been domestic dissent and critique of securitisation, despite state actors’ efforts to downplay the possible implications of expanded security cooperation for regional integration efforts. Some CSOs have sought to (re)politicise EU ‘externalisation’ and associated securitisation in the Sahel while also continuing to flag issues related to the fragmented implementation of the regional integration agenda. However, the effectiveness of domestic critique has been hampered by multiple constraints, many linked to features of the domestic policy context including the nature of interactions with national policymakers.

In practice, infringements on the right to free movement within ECOWAS such as those outlined earlier have remained common (Coderre Citation2018; CONGAD Citation2017). Local CSOs in Senegal have strenuously sought to raise the issue of increasing incidence of harassment of migrants at borders in the Sahel with national policymakers, as well as various social issues that have been observed in traditional border communities. Both are phenomena that CSOs have linked with increasing securitisation (CONGAD Citation2017). In addition, there remains a strong need for awareness-raising on rights conferred to ECOWAS citizens in communities in Senegal and Ghana, whereby local CSOs raise awareness on this topic as a core part of their activities.Footnote27

A proportion of civil society actors working on migration issues in Senegal engage in political advocacy on migration topics. The ECOWAS protocol and associated legal frameworks form a key reference point for these actors in their contestation of political narratives on migration. For example, the network of Senegalese civil society organisations, CONGAD, actively lobbies the Senegalese government on migrant rights issues and strives to build the institutional capacity of CSOs to form their own critical assessment of migration governance issues in the country and region. A coordinated campaign of the network sought to challenge the hardening of immigration controls in West Africa using the example of the Senegalese-Mauritanian border, and the arrest and deportation of migrants that this has entailed, which it argues is directly in contradiction with free movement protocols established between Mauritania and ECOWAS. It thus considers ‘the proliferation of obstacles to the freedom of movement of persons’ to have the cumulative effect of putting the right to mobility in the region at risk (CONGAD Citation2017, 18). CONGAD’s research and advocacy directly links EU external governance since 2015 to the tightening of Mauritanian legislation. Three different civil society interviewees in Dakar also included advocacy and political lobbying among their organisation’s principal activities, where advocacy activities were targeted at either the Senegalese state, or international actors, or both. Not all civil society actors are critical of securitisation practices, and indeed in Ghana political advocacy conducted by civil society actors on the topic of securitisation was less prominent.

A key difference between Ghana and Senegal is that consultation with NGOs in Senegal on migration issues is formalised, while in Ghana state-civil society interactions on migration topics occur informally. An interviewee at the Ghanaian Ministry of Justice noted that ‘We don’t have any dealings with them, unless a problem comes up’, while an official at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs commented that a channel existed, but interactions were ‘not too formalised’.Footnote28 An interviewee at GIS indicated that some activities were undertaken with CSOs, but that CSOs were not influential in shaping GIS policy or activities.Footnote29 In comparison, the Senegalese state has structures in place to engage with CSOs active in migration in the country.

However, in both countries, civil society interviewees reported struggles to access domestic policymakers. Difficulties also arose because of constraints placed on CSOs by government administrations, and the resource-intensive demands made of CSOs by their interlocutors in government. In Senegal, interviewees from two different European NGOs working on migration issues in the country noted that it was more difficult to access Senegalese decision-makers than EU or international counterparts. One project implementer characterised the Senegalese state’s approach to migration governance as ‘nationalist’ with state actors guarding ownership over migration project interventions, ensuring the state retained its privileged access to donor funds; in addition, the government required CSOs to submit regular programme reports, ostensibly to retain oversight of their activities.Footnote30 Civil society interviewees also made claims of government elitism which made bringing concerns to the attention of policymakers more difficult. One interviewee at a Ghanaian CSO noted that civil servants, working primarily in offices, were detached from issues happening ‘on the ground’; government decision-makers also were reported to increasingly demand evidence and detailed reports from CSOs when presenting an issue of concern to policymakers.Footnote31 Yet, CSOs are constrained by limited budgets which affects the extent of data collection and research they can undertake on any given issue.Footnote32

Finally, party politics and elections can affect the efforts of these actors to raise their concerns with government administrations. A project manager of a Senegalese NGO working on migrants’ rights noted that advocacy interventions were highly time-sensitive: policymakers were often occupied with political campaigning especially around elections, while changes in administrations also resulted in the need for building new networks.Footnote33 In addition, civil society actors reported migration policy interests on the part of state actors to be skewed in favour of particular topics, such as economic gains from diaspora engagement – and comparatively less interest in other topics such as the formulation of a comprehensive approach to protect immigrants’ rights in Senegal.Footnote34

These various constraints have meant that although there has been domestic dissent, such critique has been largely ineffective at re-politicising increased securitisation and re-orientating national policy.

A buffer from domestic constraints

This section conceptualises the links between state actors’ interests in securitisation, and perceptions of the opportunities and constraints that have been outlined in this article. While some areas of migration management have been subject to successful domestic politicisation, media attention and therefore public contestation (e.g. cooperation in returns and readmission), the comparative lack of barriers that Senegalese and Ghanaian state actors have encountered in border management and population monitoring has made this a fruitful area for cooperation. This link is explored and conceptualised in below, in the example of two different areas of migration governance.

Table 1. Mapping domestic issue salience on securitisation – Senegal and Ghana.

Low levels of domestic politicisation of an issue ensure fewer constraints for external actors and domestic actors to secure agreement in a given area of cooperation. When an area of cooperation is both contentious and highly visible to domestic audiences, this forms an important obstacle for cooperation. As noted previously, the capacity of EU and African policymakers to depoliticise returns is highly limited due to media attention and strong domestic opposition.

The transnationalisation of a given policy issue acts on the other hand as a buffer from domestic constraints: as more external actors are involved in a given area of cooperation, two developments may occur. Firstly, international actors aim to detach cooperation from political fields, whereby cooperation is increasingly routinised and characterised by technical intervention as is the case of migration governance initiatives shaped by security rationales. This characterises many of the migration management projects implemented under the EU’s Trust Fund in Senegal and Ghana, such as the building of civil registries. Depoliticisation is thus a strategy used by transnational actors to maintain or expand their field of intervention. However, it is also evident that depoliticised, technocratic migration governance offers African state actors the opportunity to pursue forms of capacity-building with the support of external partners – and that they have done so proactively when such cooperation aligns with their own interests.

Conclusion

While policy priorities often diverge between the EU and African states in migration cooperation (Adam et al. Citation2020; Maru Citation2021), this article has demonstrated that in the matter of security and border management, there has been common ground. In the case of Senegal and Ghana, state actors’ interests in expanding technocratic security cooperation in migration management include opportunities for reputational gains and statebuilding, modernisation of systems and tools used in public governance, increasing domestic governance capacities, and the building of institutional capacity within the state apparatus. These emerge as key reasons why Senegal and Ghana have proactively engaged with the EU in specific forms of migration management.

This article has argued that dynamics of African domestic agency are key in understanding why the notion of compatibility of migration governance models – notably, the ECOWAS integration agenda and protocol on free movement, and expanded securitisation – has gone largely uncontended. While external actors’ interest in securitising ECOWAS borders and West African migration policies could have been interpreted and acted on as a clash of ideas, it is collective social actors that play an important role in this process by challenging the validity of a norm or rule by referring to another norm or rule (Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn Citation2020). This article finds that the lack of contestation in Senegal and Ghana by state actors can be attributed to the benefits these actors have perceived from downplaying the notion that the two agendas are incompatible.

The notion of congruence between the two is nonetheless one that is constructed by political actors, as indeed other actors argue that increased securitisation undermines free movement and integration in the region and exacerbates existing implementation challenges (CONGAD Citation2017); it also potentially further legitimises the use of restrictive policies such as expulsions that African states have themselves deployed in their relations with other ECOWAS states (Idrissa Citation2019). Contention is largely absent in domestic discourse with the exception of some civil society actors that engage in political advocacy. Yet domestic critique from these arenas has been largely ineffective at re-politicising the issue. Generally, non-state actors active in West African migration governance face challenges when engaging with governments at the national and regional level (Bisong Citation2021). This includes their often-limited human and financial capacity to engage state actors; and their selective inclusion (or exclusion) by governments in policy spheres.

I proposed that the perception of a relative lack of domestic constraints in depoliticised areas of migration cooperation also emerges as an important factor that accounts, perhaps significantly, for the proactive engagement of West African state actors in this form of migration cooperation. While this analysis has focused on the ‘why’ of domestic actors’ participation in border securitisation, a further research agenda would benefit from a more explicit focus on the ‘how’: in particular, the precise strategies African domestic actors devise and deploy when securitising their borders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Melissa Mouthaan

Melissa Mouthaan completed her PhD at the Centre of Development Studies, University of Cambridge in 2020. Her research focused on the EU's cooperation with West African countries in migration and she conducted fieldwork in Senegal, Ghana and Brussels in 2017–2018. Her thesis examines the politics of migration policy formulation and the ability of African countries to shape migration governance agendas. She is currently working as a policy analyst at the OECD, having previously worked in research and consultancy at Cambridge University Press and Assessment, the European Commission, UNESCO, and Oxfam GB.

Notes

1 The Rabat Process was founded in 2006 as a regional migration dialogue platform between European states, the EU, and West and Central African states.

2 Interview with diplomat of an EU Member State, Brussels, September 2017.

3 Interview with MAESE official, Dakar, November 2017.

4 Interview with Ministry of Interior of Ghana official, Accra, February 2018.

5 Notes from government-civil society workshop, Dakar, November 2017.

6 Interview with project manager at the International Organization for Migration (IOM), Brussels, September 2017. The interviewee was commenting specifically on the case of Senegal.

7 Interview with DPAF official, Dakar, November 2017.

8 Interview with IOM representative, Accra, February 2018.

9 Interview with MAESE official, Dakar, November 2017.

10 Interviews with two MAESE officials, Dakar, November 2017.

11 Interviews with: one official at the Directorate-General for Senegalese Abroad; one official at DPAF. Dakar, November 2017.

12 Interview with official at EU Delegation to Ghana, Accra, January 2018.

13 Interview with ICMPD project coordinator, Brussels, September 2017.

14 The request made by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs aimed at creating a Diaspora Engagement Policy and resulted in a project that was later abandoned in favour of another implementer.

15 The Ghana Integrated Migration Management project (2014-2017). Its three components consisted of enhancing institutional capacities of law enforcement officers; disincentivising irregular migration through awareness raising campaigns; and strengthening migration data management.

16 Interview with GIS senior official, Accra, March 2018.

17 Interview with GIS senior official, Accra, March 2018.

18 Interview with Ministry of Foreign Affairs desk officer, Accra, February 2018.

19 Interview at the University of Ghana, Accra, February 2018.

20 Interview with DPAF official, Dakar, November 2017.

21 Interview with official at the EU Delegation, Accra, January 2018.

22 Interview with IOM representative, Accra, February 2018.

23 Interviews with: DPAF official, Dakar, November 2017; GIS official, Accra, March 2018.

24 Interviews with two officials at Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Europe Desk and Multilateral Relations Bureau. Accra, February 2018.

25 Interviews with two migration academics at the Centre for Migration Studies, University of Ghana. Accra, February-March 2018.

26 Interviews with: representatives of one Senegalese CSO; one Italian CSO; one migration academic at Cheikh Anta Diop University. Dakar and remote, October-December 2017.

27 Interview with a project manager of a Senegalese CSO, Dakar, October 2017.

28 Interviews with: Ministry of Justice senior civil servant, Attorney-General’s Office; Ministry of Foreign Affairs official, Multilateral Relations Bureau. Accra, February-March 2018.

29 Interview with GIS senior official, Accra, March 2018.

30 Interview with the project coordinator of an Italian CSO, Dakar, November 2017.

31 Interview with the executive director of a Ghanaian CSO, Accra, March 2018.

32 Interview with a project manager of a Senegalese CSO, Dakar, November 2017.

33 Interview with a project manager of a Senegalese CSO, Dakar, October 2017.

34 Interviews with: representatives of two Senegalese CSOs; one Italian CSO. Dakar, October-November 2017.

References

- Adam, Ilke, Florian Trauner, Leonie Jegen, and Christof Roos. 2020. “West African Interests in (EU) Migration Policy. Balancing Domestic Priorities with External Incentives.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (April): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1750354.

- Adamson, Fiona, and Gerasimos Tsourapas. 2020. “The Migration State in the Global South: Nationalizing, Developmental, and Neoliberal Models of Migration Management.” International Migration Review 54 (3): 853–882. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319879057.

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 1983. “Undocumented Migration in Africa: Trends and Policies.” International Migration 21 (2): 204–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.1983.tb00457.x.

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 1995. “Migration in Africa: An Overview.” In The Migration Experience in Africa, edited by Jonathan Baker, and Tade Akin Aina, 87–108. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 2009. “Migration Management in West Africa Within the Context of ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement of Persons and the Common Approach on Migration: Challenges and Prospects.” In Regional Challenges of West African Migration, edited by M. Trémolières, 18–47. Paris: OECD.

- Aguillon, Marie-Dominique. 2018. “Encouraging ‘Returns’, Obstructing Departures and Constructing Causal Links. The New Creed of Euro-African Migration Management.” Working Paper 54. Sussex: Migrating Out of Poverty.

- Akin Aina, Tade. 1995. “Internal Non-metropolitian Migration and the Development Process in Africa.” In The Migration Experience in Africa, edited by Jonathan Baker, and Tade Akin Aina, 41–53. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Andersson, Ruben, and David Keen. 2019. “Partners in Crime? The Impacts of Europe’s Outsourced Migration Controls on Peace, Stability and Rights.” Saferworld. https://www.saferworld.org.uk/resources/publications/1217-partners-in-crime-the-impacts-of-europeas-outsourced-migration-controls-on-peace-stability-and-rights.

- Arhin-Sam, Kwaku, and Franzisca Zanker. 2019. “Nigeria at a Crossroads: The Political Stakes of Migration Governance.” Policy Brief ISSN 2626-4404. Mercator Dialogue on Asylum and Migration (MEDAM).

- Awumbila, Mariama, Yaw Benneh, Joseph Teye, and George Atiim. 2014. “Across Artificial Borders: An Assessment of Labour Migration in the ECOWAS Region.” Research Report ACPOBS/2014/PUB05. ACP Observatory on Migration.

- Awumbila, Mariama, Joseph Teye, and Ebenezer Nikoi. 2018. “Assessment of the Implementation of the ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol in Ghana and Sierra Leone.” MADE West Africa. http://www.madenetwork.org/sites/default/files/CMS%20research%20Guinea%20Sierra%20Leone%20WA%202018.pdf.

- Bakewell, Oliver. 2008. “‘Keeping Them in Their Place’: The Ambivalent Relationship Between Development and Migration in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 29 (7): 1341–1358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802386492.

- Bakewell, Oliver, Hein de Haas, Stephen Castles, Simona Vezzoli, and Gunvor Jónsson. 2009. “South-South Migration and Human Development Reflections on African Experiences.” Working Paper 15. International Migration Institute.

- Bayart, Jean-François, and Stephen Ellis. 2000. “Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion.” African Affairs 99 (395): 217–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/99.395.217.

- Bigo, Didier. 2002. “Security and Immigration: Toward a Critique of the Governmentality of Unease.” Alternatives 27: 63–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/03043754020270S105.

- Bisong, Amanda. 2021. “Invented, Invited and Instrumentalised Spaces: Conceptualising Non-state Actor Engagement in Regional Migration Governance in West Africa.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (November): 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1972570.

- Black, Richard, Russell King, and Richmond Tiemoko. 2003. “Migration, Return and Small Enterprise Development in Ghana: A Route out of Poverty?” Working Paper Sussex Migration Working Paper no. 9. Sussex: Sussex Centre for Migration Research.

- Boswell, Christina. 2003. “The ‘External Dimension’ of EU Immigration and Asylum Policy.” International Affairs 79 (3): 619–639. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00326.

- Boswell, Christina. 2007. “Theorizing Migration Policy: Is There a Third Way?” International Migration Review 41 (1): 75–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00057.x.

- Bourbeau, Philippe. 2017. Handbook on Migration and Security. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Börzel, Tanja, and Thomas Risse. 2003. “Conceptualizing the Domestic Impact of Europe.” In The Politics of Europeanization, edited by Kevin Featherstone, and Claudio Radaelli. Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/0199252092.003.0003.

- Carlotti, Sebastian. 2021. “Behind the Curtain of the Border Spectacle: Introducing ‘Illegal’ Movement and Racialized Profiling in the West African Region.” Social Sciences 10 (April): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040139.

- Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. 2018a. “Informalising EU Readmission Policy.” In The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs Research, edited by F. Trauner, and Ariadna Ripoll Servent, 83–98. Oxford: Routledge.

- Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. 2018b. “Beyond the Criminalisation of Migration: A Non-western Perspective.” International Journal of Migration and Border Studies 4 (4): 397–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMBS.2018.096756.

- Castillejo, Clare. 2019. “The Influence of EU Migration Policy on Regional Free Movement in the IGAD and ECOWAS Regions.” Discussion Paper 11/2019. Bonn: German Development Institute. https://www.die-gdi.de/en/discussion-paper/article/the-influence-of-eu-migration-policy-on-regional-free-movement-in-the-igad-and-ecowas-regions/.

- Chou, Meng-Hsuan, and Marie Gibert. 2012. “The EU-Senegal Mobility Partnership: From Launch to Suspension and Negotiation Failure.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 8 (4): 408–427.

- Coderre, Mylène. 2018. Entre Libre-Circulation En Afrique de l’Ouest et Coopération Migratoire Avec l’Union Européenne: Quels Enjeux Pour La Gestion Des Migrations Au Sénégal? [Between Free Movement in West Africa and Migration Cooperation with the European Union: What Issues for Migration Management in Senegal?]” 44. Les Cahiers Du CRIEC. Montreal: UQAM.

- Collyer, Michael. 2016. “Geopolitics as a Migration Governance Strategy: European Union Bilateral Relations with Southern Mediterranean Countries.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (4): 606–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1106111.

- CONGAD. 2017. “Axe Rosso-Nouakchott: Des Mobilités En Danger. Rapport d’observation à La Frontière Sénégal-Mauritanie [Rosso-Nouakchott Axis: Mobilities in Danger. Observation report at the Senegal-Mauritania border].” https://www.lacimade.org/publication/axe-rosso-nouakchott-mobilites-danger/.

- Cross, Hannah. 2013. Migrants, Borders and Global Capitalism: West African Labour Mobility and EU Borders. London: Routledge.

- Del Sarto, Raffaella. 2009. “Borderlands: The Middle East and North Africa as the EU’s Southern Buffer Zone.” In Mediterranean Frontiers: Borders, Conflict and Memory in a Transactional World, edited by Dimitar Bechev, and Kalypso Nicolaidis, 149–166. London: Tauris Academic Studies.

- EC. 2019. “EUTF National Projects – Senegal.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/sahel-lake-chad/senegal.

- EEAS. 2017. “Press Release. Contrôle et Surveillance Des Frontières: Le Sénégal et l’Union Européenne Inaugurent de Nouveaux Poste-Frontières [Border Control and Surveillance: Senegal and the European Union Inaugurate New Border Posts].” October 27, 2017. https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/senegal_fr/34710.

- Fisher, Jonathan, and David M. Anderson. 2015. “Authoritarianism and the Securitization of Development in Africa.” International Affairs 91 (1): 131–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12190.

- Frowd, Philippe M. 2014. “The Field of Border Control in Mauritania.” Security Dialogue 45 (3): 226–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614525001.

- Frowd, Philippe M. 2018. Security at the Borders: Transnational Practices and Technologies in West Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gazzotti, Lorena, Melissa Mouthaan, and Katharina Natter. 2022. “Embracing Complexity in ‘Southern’ Migration Governance.” Territory, Politics, Governance (March): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2022.2039277.

- Geiger, Martin, and Antoine Pécoud. 2010. “The Politics of International Migration Management.” In Politics of International Migration Management, edited by Martin Geiger, and Antoine Pécoud, 1–20. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huysmans, Jef. 2006. The Politics of Insecurity: Fear, Migration, and Asylum in the EU. London: Routledge.

- Idrissa, Rahmane. 2019. “Dialogue in Divergence: The Impact of EU Migration Policy on West African Integration: The Cases of Nigeria, Mali, and Niger.” FES Papers. Bonn: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- IOM. 2017. “UN Migration Agency: Senegal Improves Border Management Practices.” October 31, 2017. https://www.iom.int/news/un-migration-agency-senegal-improves-border-management-practices.

- Kabbanji, Lama. 2011. “Vers une reconfiguration de l’agenda politique migratoire en Afrique de l’Ouest.” Études internationales 42 (1): 47–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/045877ar.

- Kreuder-Sonnen, Christian, and Michael Zürn. 2020. “After Fragmentation: Norm Collisions, Interface Conflicts, and Conflict Management.” Global Constitutionalism 9 (2): 241–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045381719000315.

- Kunz, Rahel, and Julia Maisenbacher. 2013. “Beyond Conditionality Versus Cooperation: Power and Resistance in the Case of EU Mobility Partnerships and Swiss Migration Partnerships.” Migration Studies 1 (2): 196–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnt011.

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Rahel Kunz. 2008. “The Migration–Development Nexus in EU External Relations.” Journal of European Integration 30 (3): 439–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036330802142152.

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Nicola Piper. 2021. “Regions and Global Migration Governance: Perspectives ‘from above’, ‘from below’ and ‘from Beyond’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (November): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1972564.

- Little, Richard. 2007. International Relations: Metaphors, Myths and Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maertens, Lucile. 2018. “Depoliticisation as a Securitising Move: The Case of the United Nations Environment Programme.” European Journal of International Security 3 (3): 344–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2018.5.

- Maru, Mehari Taddele. 2021. “Migration Policy-Making in Africa: Determinants and Implications for Cooperation with Europe.” Working Paper. European University Institute. https://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/71355.

- Meyer, John, and Brian Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/226550.

- Moe, Louise Wiuff, and Anna Geis. 2020. “Hybridity and Friction in Organizational Politics: New Perspectives on the African Security Regime Complex.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14 (2): 148–170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2020.1729618.

- Mouthaan, Melissa. 2019. “Unpacking Domestic Preferences in the Policy-‘Receiving’ State: The EU’s Migration Cooperation with Senegal and Ghana.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (1): 35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0141-7.

- Natter, Katharina. 2021. “Tunisia’s Migration Politics Throughout the 2011 Revolution: Revisiting the Democratisation–Migrant Rights Nexus.” Third World Quarterly (July): 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1940126.

- Neal, Andrew. 2009. “Securitization and Risk at the EU Border: The Origins of FRONTEX*.” Journal of Common Market Studies 47 (2): 333–356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2009.00807.x.

- Peil, Margaret. 1971. “The Expulsion of West African Aliens.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 9 (2): 205–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00024903.

- Pécoud, Antoine. 2015. Depoliticising Migration: Global Governance and International Migration Narratives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Powell, Walter W, and Paul DiMaggio. 1991. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Raineri, Luca. 2021. “The Bioeconomy of Sahel Borders: Informal Practices of Revenue and Data Extraction.” Geopolitics (April): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1868439.

- Reslow, Natasja. 2012. “The Role of Third Countries in EU Migration Policy: The Mobility Partnerships.” European Journal of Migration and Law 14 (4): 393–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15718166-12342015.

- Sadiq, Kamal, and Gerasimos Tsourapas. 2021. “The Postcolonial Migration State.” European Journal of International Relations (April): Article 13540661211000114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/13540661211000114.

- Sandor, Adam. 2016. “Border Security and Drug Trafficking in Senegal: AIRCOP and Global Security Assemblages.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 10 (4): 490–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2016.1240425.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Ulrich Sedelmeier. 2004. “Governance by Conditionality: EU Rule Transfer to the Candidate Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (4): 661–679. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176042000248089.

- Stutz, Philipp, and Florian Trauner. 2021. “The EU’s ‘Return Rate’ with Third Countries: Why EU Readmission Agreements Do Not Make Much Difference.” International Migration 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12901.

- Teye, Joseph, Mariama Awumbila, and Yaw Benneh. 2015. “Intra-Regional Migration in the ECOWAS Region: Trends and Emerging Challenges.” In Migration and Civil Society as Development Drivers – A Regional Perspective, edited by Ablam Akoutou, Rike Sohn, Matthias Vogl, and David Yeboah, 97–124. Bonn: Zei Centre for European Integration Studies.

- Tholens, Simone. 2017. “Border Management in an Era of ‘Statebuilding Lite’: Security Assistance and Lebanon’s Hybrid Sovereignty.” International Affairs 93 (4): 865–882. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix069.

- Van Dessel, Julia. 2021. “Externalization Through ‘Awareness-Raising’: The Border Spectacle of EU Migration Information Campaigns in Niger.” Territory, Politics, Governance (October): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1974535.

- van Munster, Rens. 2009. Securitizing Immigration: The Politics of Risk in the EU. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Walther, Olivier, and Denis Retaillé. 2008. “Le modèle sahélien de la circulation, de la mobilité et de l’incertitude spatiale.” Autrepart 47 (3): 109–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/autr.047.0109.

- Waltz, Kenneth. 1979. Theory of International Politics. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- Whitfield, Lindsay, and Alastair Fraser. 2010. “Negotiating Aid: The Structural Conditions Shaping the Negotiating Strategies of African Governments.” International Negotiation 15 (3): 341–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/157180610X529582.

- Zanker, Franzisca. 2019. “Managing or Restricting Movement? Diverging Approaches of African and European Migration Governance.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (1): 17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0115-9.