ABSTRACT

This article examines when, how and why local agreements are used to end violent conflict, drawing on a new global dataset of local agreements. It provides a typology of security functions that local agreements deliver at different stages of the conflict-to-peace cycle, and the types of space they address and create. It examines the relationship of local agreements to national peacemaking processes, arguing that they reveal the nested nature of local, national, transnational, and international conflict in protracted conflict settings. This reality points to the need for a new political imaginary for peace processes design. The conclusion sketches its contours.

Introduction

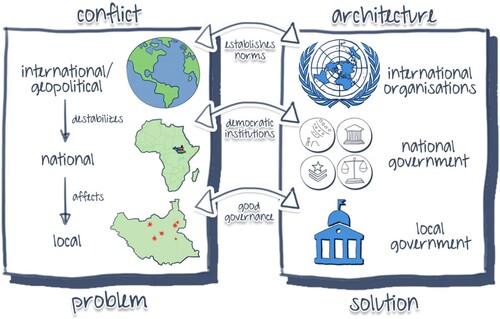

The ‘big peace’ peace process is premised on a concept of intrastate conflict that contemplates two key protagonists: on one side a dysfunctional, authoritarian, or ‘ethnically owned’ state; on the other, armed opposition groups and their supporters. Comprehensive agreement-making focuses on reaching an ‘elite pact’ between these actors, to be translated into a new constitutional structure that over time will replace violence with politics. The peace process has an implicit territorial geography – that of the nation-state. This geography is the focus for creating a revised state architecture comprising an executive, legislature and judiciary, and security forces with the aim to restoring the state’s monopoly on government and the use of force (see ; cf. Agnew Citation1994). This state architecture contemplates national government and conflict resolution to be in a hierarchical relationship with similar governance projects above at the international level and below at the local level ().

The political imaginary of this overall architecture is fractal-like, with similar governance institutions at each level operating to ensure cooperative government and conflict prevention at that level. A system of consent to be governed, operating upwards, is then somehow meant to deliver multi-scalar peace down through the hierarchy from global to national to local ().

In recent times, the peace process based on this imaginary no longer seems to fit the fragmented nature of conflict in the most complex and protracted settings, or the fragmented global order in which they sit. These settings increasingly involve a high degree of fragmentation of armed actors, more active involvement of geopolitical conflict underwriters, and more fluid conflict landscapes in which local and international actors can quickly ‘changes sides’ and ‘change partners’. This new complicated conflict tapestry, emerging in the last ten years, and typified by conflicts and peace processes in South Sudan, Sudan, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Libya, is not merely what continues when peace processes fail: it is a product of that failure. Conflict fragmentation is in part a product of the nation-state-building projects that have been tried and have failed, with new transitions becoming overlaid on earlier ones.

The spatial consequences of fragmentation are immense: if conflict can no longer be resolved by primarily focusing on national geographies and a singular conflict, how can it be brought to an end? What is the new imaginary that would underpin the search for new places and spaces of conflict resolution, and translate them into an institutionalisation that could be squared with existing state boundaries? No alternative script yet exists, even though old peacemaking tools are rapidly manifesting dysfunction as they map onto a new world they were not designed for and do not fit (de Coning Citation2018; Millar Citation2020).

In this article, we use insights from a new qualitative dataset on local agreements (PA-X Local, https://www.peaceagreements.org/lsearch), to explore the places and spaces of local agreements as an alternative frame from which to understand conflict resolution in the current moment. We use the term space to mean both actual and conceptual space, and place to mean a geographically existing location. We suggest that local agreements present a new picture of conflict and point to a new imaginary for peace processes. We begin by examining what we term a ‘globalised practice’ of local agreement-making. We then turn to consider the security functions that local agreements provide at different stages of a conflict to peace process to implementation cycle, and the types of conflict ‘space’ they attempt to address in so doing. We use the discussion to argue for a new approach to peace process design that could respond to current conflict realities.

Local agreements: A globalised practice

While useful accounts of local peacemaking practices exist, they often focus on single-country case studies that emphasise the context-specific dimensions of the practice and point to positive and negative use of such agreements in different contexts. Local agreements are by their nature context-specific and diverse, therefore the idea that comparison and comparative data can be useful is controversial. However, it is also possible to see local agreement-making as having globalised dimensions. In recent years, the PA-X Local Peace Agreement Database project has involved collecting, classifying, and coding local agreements in order to explore their comparative dimensions. This process has resulted in a collection of 318 local agreements between 1 January 1992 and 30 June 2021, in over 21 different countries, with multiple actor dyads within some of those countries (Bell et al. Citation2020). The following working definition of ‘a local agreement’ lies at the heart of the collection:

Local agreements may be formally documented, but are often informally documented or even unwritten. They relate to a geographic area smaller than the entire conflict zone, and involve at least some local actors, whether in an immediate village, neighbourhood, municipality, city or specified military zone. Their aim is to mitigate or end conflict in that area by addressing local conflict drivers and actors. (Bell et al. Citation2021)

Each component of this definition can, however, be contested by any specific example. Part of the difficulty of defining local agreements is that in almost every case ‘the local’ as a space is inevitably connected to the space of the ‘national’, the ‘transnational’, and the ‘international’ in non-hierarchical ways. In other words, the term ‘local’ implies a spatial relationship of relativity, rather than a distinct territorial space (Massey Citation1994).

Local agreement-making is globalised in three main respects. First, it is globalised in ‘the vast constellation of situated processes’ that collectively tell us something as to the role of ‘the local’ in conflict and peace-generating projects (McFarlane Citation2019, 13). Examination of local agreements across contexts illustrates: common conflict dynamics that provoke them; common ways of doing business; commonality in the forms of ‘agreement’ made; and common challenges that emerge across very different contexts (Bell et al. Citation2021). This globalised dynamic has been pointed out in previous scholarship focusing on local peacemaking (Engle Merry Citation2006; Mac Ginty and Richmond Citation2013). Local agreements sometimes embed a national peace but also serve as sites that can resist and subvert national peacemaking goals – particularly when attempting to transmit international norms.

Second, while local agreements have always been a hidden part of most peace processes, the crisis in ‘the big’ peace process means that local agreements are also increasingly a matter of international attention. As national peace processes become ‘stuck’, normatively-driven donors and external interveners such as the United Nations increasingly look to local arenas both as a place to embed a national peace deal and as a site for strategic engagement to address or even bypass logjams in the national peace process. International mediation is now often employed for local agreement-making. The United Nations (Citation2020), for example, has recently published guidelines on engaging with local mediation. A ‘glocalised’ practice of local mediation is now extensively supported by external states and international organisations (Bell et al. Citation2021; cf. Swyngedouw Citation2004).

Third, local mediators and armed actors are seldom ‘purely’ local. They are often also ‘transnational actors’ operating as ‘circulating locals’ (Engle Merry Citation2006, 40), who move between local, national, and international spheres of action, brokering in each direction with international and transnational actors. Even actors who could be viewed as primarily local often wear a range of different local and national hats simultaneously (Kappler Citation2015). International involvement in local spaces itself draws local actors into the arena of international contestation: local areas and groups increasingly find themselves part of a geopolitical and normative battleground between a range of jostling international actors that support competing local peacebuilding and war-making projects. Local actors will often be astute at cultivating these relationships and hedging between them, while normative interveners often struggle to understand what this hedging means for their projects and its normative objectives.

The spaces of local agreements and the ‘imaginary’ of the peace process’

How then should we best understand the space of local agreement-making with reference to the ‘national peace process’? We suggest that the existing peace process imaginary offers two competing visions of how local and national peace processes are linked, here using the term imaginary to mean a ‘collective structure that organizes the imagination and the symbolism of the political’ (Browne and Diehl Citation2019, 393).

The local as adjunct to the national

A first, internationally dominant vision understands local peacemaking as an often-necessary adjunct to national peacemaking. For international actors local agreements provide a possible ‘security resource’ to the deficit of national peace processes, whether at early stages of conflict onset, where local conflict can trigger national conflict, or at end stages, where it can trigger process breakdown. Many of the international reports into local peacemaking note the resources that local agreements can bring to national peacemaking efforts, and argue for their better articulation to national peacemaking strategies (e.g. Mechoulan and Zahar Citation2017). However, these reports also acknowledge the need for opportunism in providing effective support, and emphasise the need to intervene in ways that do not destroy local ownership – recommendations which sit uneasily with instrumentalising local agreement-making as a tool for national peace.

The local as equal-status site of intervention

A second approach – operating more from the ‘local turn’ – is to understand local agreements as an important site of peacemaking-as-development in their own right. This approach often resonates with local actors who understand themselves to be simply entrepreneurially ‘doing their own thing’, in a context where the state does not exist around them in any meaningful sense. International actors are often prepared to support local processes without a wider agenda where they create important moments and examples of peace, where little else is possible. Supporting local peace processes sits easily with unwritten understandings of the value of local peacebuilding activities to development, even when it is unclear they can be ‘scaled up’ into a national peace effort. ‘Local governance’ and ‘local resilience’ are all viewed as key to development, and able to be built even without a functional central state, for example as projects within cities (Pospisil and Kühn Citation2016).

Towards an alternative imaginary

We suggest, however, that the above framings in forming opposites have failed to connect with detailed appraisal of when and how local agreements operate – in part due to lack of comparative data. Using a concept of space that is both material and conceptual, we draw on the new PA-X dataset of local agreements to set out a new map of when and how local agreements are used. This data points to how peace and conflict, and national and local peacemaking, are deeply intertwined. We use this data to illustrate the different security and peacemaking roles that local agreements perform at different stages of a conflict-to-peace life-cycle, not all of which are ‘peace focused’. We set these roles out in , to comprise: (1) local ‘pre-negotiation’ agreements to de-escalate, contain, or mitigate conflict as a short-term measure in the middle of emerging or ongoing local (and even national) conflict when there is no national peace process in play; (2) local ‘framework’ agreements which attempt to produce a new local political settlement during a peace process, that will return a measure of governance and stability to the locale (whether there is a national settlement or not); and (3) local ‘implementation’ agreements which attempt in some way to implement a national peace accord that has already been signed but lacks wider social and civic involvement.

Table 1. Types of local agreement, according to function and form.

Cutting across our temporal analysis of local agreements, we point to the different types of physical and conceptual spaces that local agreements create (). The first is what we term ‘territorially-limited transcalar space’, where local agreements address a defined sub-state geography, such as a city, to produce a local political settlement in ways that can impact on the wider conflict. The second is ‘borderland mediation space’, for example between two different tribes or clans, which addresses the interfaces between different communities as places of intercommunal transaction, movement, and exchange that contain the potential for conflict or peace. The third space is what we term ‘route-of-passage space’, that is, a space such as a road or path which is a distinct from the surrounding area, created by the very act of journeying. The road as a space is often significant to those that ‘stand apart’ from the conflict, and seek to pass through it, such as pastoralists, the displaced, or indeed humanitarian workers. These three different types of space persistently appear in local agreements in intertwined ways. We consider how the security functions of local agreements connect to – and sometimes create – these types of conceptual spaces at different stages of an attempted peace or transition process.

Table 2. Types of space arising across local agreements.

Local ‘pre-negotiation’ agreements to de-escalate, contain, or mitigate conflict

A number of different types of local agreement aim to de-escalate, contain, or mitigate conflict by providing security functions to local communities, whether a national peace process is in place or not. These agreements often address all three types of conceptual space simultaneously: they can provide for intercommunal sharing of a defined space of conflict that has wider national significance (territorially limited trans-scalar); they can address how to manage the interface between one space and another and the relationships between the different groups that inhabit each space (borderland mediation); and they can protect more nomadic groups of international or locals who seek to move through spaces to deliver spiritual, moral, or physical goods or seek refuge (route-of-passage). We set out the main types of pre-negotiation agreements as follows.

Civic de-escalation attempts

Ad hoc civic agreements are produced when local civic actors negotiate their own form of agreement, often as an early response to localised outbreaks of violence. These civic agreements are regularly signed by community leaders with a degree of connection to, and influence over, local armed groups. Local armed groups may be visibly or invisibly bound by these agreements are as signatories or non-signatories because they were involved in the negotiations, are the target of agreement pleas, or are drawn into compliance using traditional or informal justice systems to underwrite and even reach agreement (Kheirallah and Alsafadi Citation2021; Ullah and Ahmad Citation2021). For example, in 2017 nine Libyan tribes signed an agreement outlining shared beliefs and principles (including ‘the refusal and denouncement of what the international community does in seeking to settle the illegal migrants inside Libya’), and called on other tribes to join them.Footnote1 In Wonduruba, South Sudan, civic and religious leaders brokered an agreement in December 2015 with the local Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) faction following widespread abuses.Footnote2 In 2016, leading citizens of Benghazi, Libya, from across the political spectrum, released a joint humanitarian call, imploring armed actors to reach an agreement to comply with humanitarian principles, that was in many respects more inclusive of conflicted groups than the national Libyan Peace Agreement.Footnote3 Similar calls for armed actors to return to dialogue in the face of violence against local communities were made in 2017 and 2019 by civil society groups in the Chocó Department of Colombia (ABC Colombia Citation2019; cf. Idler Citation2021), and tested the distinction between an agreement and a humanitarian call.

These local agreements are not a substitute for national peace processes, yet they are undertaken with a sense of a trans-scalar contribution to peace. They can be an important response to escalating conflict, because they can stem nationwide hostilities, which can be triggered regardless of whether national or international actors are engaged locally. They can play a ‘de-confliction’ role in contentious areas and stop them becoming wider conflict-ignition moments.Footnote4 They provide for conflict management in distinct geographic spaces understood as inevitable places of mixing, where peace requires the space – say a city – to be shared.

Inter-armed group de-confliction agreements

A different type of ‘de-confliction’ agreement can be found in local truces, ceasefires, de-militarisation, and humanitarian agreements. While these types of agreement can be negotiated nationally, they often emerge at local level, driven by a need to facilitate key humanitarian tasks in the midst of conflict, such as vaccination programmes or right-of-passage for relief convoys. These tasks require micro-spaces of conflict to be addressed, such as villages or checkpoints. The terms of such local agreements aim to alleviate the effects of conflict and improve the quality of life for affected populations in specific areas. Often the line between local ceasefire and humanitarian agreements is blurred: ceasefires regularly contain humanitarian provisions including access, prisoner release, or evacuation provisions – which become the motivation for the ceasefire. Conversely, local humanitarian agreements typically provide for hostilities to be suspended to enable at least windows of humanitarian relief. However, some agreements are limited to one or the other function and we address them separately below.

Truces, ceasefires, and de-militarisation agreements

As with those at national level, local truce agreements seek to suspend hostilities, but parties may also agree to: delimit territorial control; suspend propaganda; organise joint committees that oversee implementation and resolve disputes; and impose, amend, or lift curfews.Footnote5 Local ceasefire agreements often focus on a small area – a strategically significant flashpoint – including streets, neighbourhoods, municipalities, and divided cities.Footnote6 They are often brokered between commanders at the corps, brigade, and battalion levels, as well as with international peacekeeping commanders of similar rank who may have better relationships with local military counterparts than higher-ranking officers/officials. The potential scope of actors can be illustrated by a 2014 ceasefire for Arsal, Lebanon, signed by Hezbollah, al-Nusra Front, and the Lebanese Army and brokered by the Lebanese Institute for Democracy and the Muslim Clerics Association.Footnote7

These agreements can involve territorially limited political settlements with trans-scalar significance. Some local agreements fall between ceasefire agreements and agreements aimed at creating a new localised political settlement, by providing a set of commitments for demilitarisation of cities, or areas within them, or between two neighbouring areas where different armed groups dominate, in ways that have broader national significance. The agreements focus on providing for armed groups to ‘withdraw forces’ from armed conflict, remove checkpoints, and enable civilian administration of the area.Footnote8

Ceasefire and de-militarisation agreements can also produce a borderland mediation space because they create the borderland as its own space with its own governance regime. For example, some ceasefire agreements will list the grievances of the different parties, and have measures providing for delimitation and ‘peaceful coexistence’ between neighbouring areas in dispute, or entirely exempt interface areas from fighting. In Syria, two local councils from the villages of Jbala and Ma'aratamatar agreed with all armed groups present in the area that the villages would be ‘completely spared’ from the fighting, they also agreed to prevent armed groups from using roads or establishing military bases in the settlements, in effect withdrawing these villages from the immediate conflict.Footnote9 This agreement created a territorially limited settlement with trans-scalar significance, and dealt with its location as a borderland interface between areas contested by armed groups. The attempted ‘zone’ or ‘island’ for civilians can be understood as providing a buffer zone to manage the relationship between armed groups (see Hancock and Mitchell Citation2007).

Humanitarian agreements

Humanitarian agreements often create ‘route-of-passage’ spaces in providing for the free passage of humanitarian actors, rather than mediating an end to conflict. Humanitarian actors respond to the call of human need and must find a route to address it, negotiating transit through the conflicts they address. Humanitarian agreements focus on the material needs of populations in specific locations, and can provide assistance, civilian evacuations, prisoner release or exchange and information on missing persons and mortal remains, and unimpeded travel for humanitarian agencies. Agreements can be between different armed groups, or between armed groups and humanitarian agencies, to secure delivery of aid (see Price Citation2020; Pospisil Citation2022). International mediators of local humanitarian agreements tend to be drawn from humanitarian and development communities, rather than peacebuilding ones, although there are also examples of UN peacekeepers negotiating humanitarian access deals (see Goodwin Citation2005). The International Committee of the Red Cross (or Red Crescent), for example, is regularly called upon to facilitate prisoner exchanges or the evacuation of civilians from conflict-affected areas, as demonstrated by agreements in Yemen and Syria.Footnote10 Often humanitarians must negotiate with a range of local armed groups if delivery of aid is to take place. The resultant agreements are often task-focused and temporary, and while mediators may hope that they create relationships, trust, and modalities of working that might help support a national peace process to emerge, in practice wider political objectives must often be parked in order to reach agreement on relief. In the context of Syria, however, Dieckhoff argues that despite attempts by humanitarian actors to draw a clear line between frontline humanitarian negotiations and political negotiations, ‘humanitarian and political negotiations are governed by a complex interdependence’ in which it is hard to identify ‘clear-cut conceptual and practical divisions’ (Dieckhoff Citation2020, 565). In negotiating and then travelling along routes for their spiritual purposes, humanitarian actors provide a ‘map and a direction’ for literally and figuratively finding a way across the country (cf. Chatwin Citation1987, 13).

Tactical agreements

It can sometimes be difficult to delimit humanitarian agreements from more ‘tactical agreements’, that is, agreements that ostensibly focus on ‘humanitarian or security’ concerns but with the explicit or implicit aim to destabilise other groups, rather than wider stabilisation. Ceasefire or humanitarian agreements can be reached to consolidate battlefield gains, obtain control over resources, or redirect military energies towards other groups. They can seek to undermine national-level talks and elites by reinforcing claims of local-level authority and consolidating the territorial gains of a conflict dyad marginalised by the main peace process negotiations.

Two different types of tactical agreement, in particular, illustrate and indicate the fuzzy line between ‘peace agreements’ and agreements focused on conflict.

Alliance agreements

What we term ‘alliance agreements’ occur when groups agree to temporarily or permanently align against common opponents. This is sometimes a step towards a peace process when groups sign inter-group agreements in an attempt to stop fighting to form a stronger inter-group negotiation position in the national peace talks. Sometimes regional negotiation can bring together a number of groups with a common enemy, but often also with histories of conflict between them, to agree ceasefires and a joint strategy as as regards engaging with the national talks process. For example, in Myanmar, multiple Ethnic Armed Organisations came together across locales to sign a ‘nationwide ceasefire’ with the state, despite their own histories of inter-organisational conflict.Footnote11 Intercommunal agreements in Mali similarly attempted to deal with inter-Azawadi tensions and negotiating positions – with a view to Azawadi groups having a common position of engagement in the periphery–state Azawad–Mali peace negotiations.Footnote12

However, other local ceasefire agreements address inter-group conflict with a view to terminating one battle front to consolidate forces for another. For example, an agreement from Syria between the Levant Front and the People’s Protection Units (YPG), signed in February 2015, iterates the goal of pursuing a common enemy in the form of the Islamic State and the Syrian Army.Footnote13 Similarly, in 1993, the self-declared ‘Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia’, signed a series of alliance agreements with other armed actors also fighting against the central Bosnian government.Footnote14 Here, each self-declared entity agreed to a ceasefire with the others, and to recognise the legitimacy of each other’s territorial control, in part to reduce the number of open fronts and free up troops and resources. Intra-jihadist group conflict in South Waziristan, Pakistan in 2007 similarly led to an agreement between the Ahmadzai Wazir Tribe of Waziristan and the Wana Taliban, in Pakistan, which states that ‘It will be a punishable crime to shelter or assist Uzbek or their allied fighters or any local or foreign troublemakers and terrorists’, with the penalty of a fine, loss of property, and exile.Footnote15 In Libya, a myriad of local agreements reflects the proliferation of a complex tapestry of armed groups, many small, which have made different alliances and shifts over time, in strategic moves to give them strength in internal power struggles (Thornton Citation2021).

Surrender agreements

Surrender agreements are a second type of tactical agreement. Often touted as ‘humanitarian ceasefires’ or – in the case of Syria – ‘reconciliation’ agreements, what we and others term de facto ‘surrender agreements’, are deals that occur in highly asymmetrical negotiations between a dominant army and a local defence force, and aim at the withdrawal of the less powerful group through humanitarian evacuation procedures. Recent cases of such agreements have occurred in the neighbourhood enclaves of besieged cities in Syria (Haid Citation2018). Similar agreements were used in conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia to expel populations from overrun areas, and to manage the surrender of armed groups.Footnote16 Whilst this type of agreement often uses humanitarian language that emphasises the needs of local people, it also becomes a mode of consolidating military victory and territorial gains, and managing forced displacement of opposing populations while filtering out combatants from the losing side. In Syria, this dual-purpose approach has featured in criticism of local truces, which Sosnowski (Citation2020) conceptualises as ‘strangle contracts’. For example, a 2015 truce from al-Zabadani, Syria, explicitly states that fighters may not be evacuated,Footnote17 whilst the 2014 Homs Hudna mediated by the UN restricts those qualifying for evacuation as ‘civilians (children, women, elderly people)’.Footnote18 Similarly, an agreement in August 1995 in Bosnia, between General Ratko Mladic and civilian representatives of the Zepa ‘safe area’ (some of whom later testified at the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia that they had no choice but to sign), contained separate modalities for the ‘able-bodied’ and the civilian population, following the fall of the enclave’s defence forces after a concentrated shelling campaign.Footnote19

Tactical local agreements may aim for reduction of armed conflict (a bit more ‘peace’) in some directions, but to enable it to be increased (more war) in others. These agreements play out battles over ownership of political and physical space and power, rather than resolve them. The example of Syria also illustrates how local agreement-making can change over time, supported differently by different geopolitical actors, determining whether the agreements reached resolve power disputes or merely reconfigure the spatial reach of the powerful. Tactical agreements point again to the overlaying of territorial trans-scalar, borderland mediation, and route-of-passage spaces of local agreements. They also illustrate how peace and conflict are often nested and connected: as one conflict is terminated along one axis in one space, another may be incentivised elsewhere (cf. Millar Citation2020).

Local ‘framework’ agreements aimed at forms of local political settlement

Some agreements focused on ‘stopping the fighting’ go beyond ceasefires and humanitarian relief, and attempt to create ‘area-based’ political settlements, which wrap together armed actors, and communities in intercommunal forms of agreement (as our examples of civic de-escalation agreements demonstrated). These agreements also create forms of ‘territorially limited trans-scalar’ peace, but sometimes also address the need to manage borderlands, and protect those – for example, pastoralists – who seek to pass along their traditional routes-of-passage. We point to three distinct sub-types of ‘comprehensive’ local agreement.

Intercommunal peace processes

Beyond ceasefires and truces, local actors sometimes engage in localised forms of peace processes that attempt to address core conflict issues, often through indigenous conflict resolution initiatives and even local justice systems. Religious, kinship, and cultural groups may champion these processes, which can also include local government representatives. These local intercommunal processes can emerge at different stages of the national conflict and peace process, often operating on the side-lines of struggling or failing national peace processes. For example, peace conferences and community peace agreements are prevalent in pastoral-agrarian communal conflicts across Kenya, Nigeria, Somalia, and South Sudan, and have also been used in Afghanistan. These have brought together large numbers of local stakeholders including religious and traditional leaders, the business community, armed groups, and community members to address and identify root causes of conflict. The agreements often deal with access to land and water, nomadic rights, traditional or religious justice, material reparations, local governance, and security. They may use traditional forms of conflict resolution such as payment of ‘blood money’, or exchange of cattle or even women,Footnote20 some of which may run against international norms of gender equality or justice. As the oft-used term ‘conference’ indicates, often the local act of ‘coming together’ is as important as what is agreed.

The size of peace conferences vary, as does their relationship to the state. The Sudanese government in Khartoum, for example, did not support the 1999 Wunlit Conference in Southern Sudan, but local power brokers including the Sudan People’s Liberation Army contributed to the conference preparations.Footnote21 On the other hand, an agreement between the Yantaar and Hubeer sub-clans in Somalia explicitly sought support for the decision from the Transitional Federal Government.Footnote22 In Helmand Province, in Afghanistan in 2006 in Musa Qala, a jirga of elders/tribal leaders struck a 14-point written agreement with Helmand’s provincial government, and tribes of the Upper Sangin Valley ‘twice struck deals pledging loyalty in return for a more inclusive social contract’, in essence promising not to harbour Taliban fighters, and to organise security on their own terms, in return for external forces staying out (Cavendish Citation2018, 76). Greater focus on the history of intercommunal processes in many countries has led to increased state recognition and funding from international organisations and aid agencies to assist these local peace processes. Significant programmes supporting local peace agreement-making have also taken place in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Iguma Wakenge and Vlassenroot Citation2020), Somalia (Interpeace Citation2008), Nigeria, Libya, and Central African Republic (CAR) (Humanitarian Dialogue Citation2021). Interestingly, some of these projects have focused on cross-border regions and disputes leading to a form of ‘transnational local peace process’.Footnote23

‘Peace solidarity’ agreements which link to national conflict resolution efforts

Local agreements can be used to bring distinct communal grievances within the frame of a national peace process, extending its agenda at the local level. The agreements use the ‘idea’ of a national peace process to broker peace on other fronts. For example, a peace process brokered by the Community of Sant’Egidio, between Tuareg and Tebu clans in Southern Libya in 2016, produced a joint declaration supporting the Government of National Agreement created by the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement (LPA), even though there was no tangible institutional connection between the LPA and the local peace process.Footnote24 An earlier example can be seen in Colombia where, in 2001, the ‘residents and peasants’ of South Bolivar Province – a site of conflict between Colombian troops and the National Liberation Army (ELN) – met to affirm their support for the dialogue between the two warring parties.Footnote25 These ‘peace solidarity’ agreements address localised grievances perhaps considered outside the national framework, but where local communities view the national agreement as providing an opportunity for local peace gains.

City deals

Cities often aim for forms of local political settlement (territorial trans-scalar), in ways that can become a symbolic fractal of national and international attempts to reach a wider political settlement. Interesting examples exist where cities have tried to ‘except’ themselves from national conflict, or to deal with how that conflict plays out within the city space, or to extend the concept of the national peace process to deal with quite different forms of city violence as described above. For example, after parties reached multiple comprehensive agreements to resolve conflict across Bosnia in 1995, in February 1997 intercommunal violence escalated in the city of Mostar, which had been divided and the site of various frontlines throughout the war. In response to the violence, representatives of the Presidency, national party leaders, and the power-sharing government in Mostar (the mayor and deputy mayor representing different ethnic communities) met under the auspices of the internationally appointed Office of the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina and agreed a series of ‘Decisions on Mostar’ to calm tensions and prevent further violence.Footnote26 Despite addressing local insecurity and the functioning of policing structures in one city, the agreement can also be understood as a litmus test for the fragile, nationwide power-sharing settlement (International Crisis Group Citation1997). Indeed, Mostar had already ‘localised’ the main peace agreement that created the (Bosniak–Croat majority) Federation, by including an ‘Interim Statute for Mostar’.Footnote27 A similar ‘localised’ agreement was created within the wider Dayton Peace Agreement that later brought peace to the country as a whole: the town of Brčko on a contentious border between the Federation and the (Serb majority) Republika Srpska, was ‘except’ from the Agreement, to be the subject of a future internationalised arbitration over its location and arrangements, with its own international administration.Footnote28

In the city of Batangafo in the Central African Republic, armed groups operating within the city, alongside religious groups, youth representatives, civil society representatives, the ‘peace and social cohesion committee’, the sub-prefect, and the mayor signed two agreements in 2018 and 2019. Both agreements committed the Ex-Seleka and the Anti-Balaka to ensure free movement, ‘real collaboration’, and to establish a ‘joint monitoring committee to preserve peace in said locality’, under the supervision of the UN mission in CAR (MINUSCA).Footnote29 Interestingly, although the points of agreement related to specific local issues within Batangafo, both agreements also state that ‘this agreement will serve as a transposable model for certain conflict zones in Central African territory’. The city deal had national or ‘trans-scalar’ aspirations: it was not just a deal for the ‘specific locality’, but offered the possibility of a transposed peace process model with opportunities to ‘scale out’ and ‘scale up’, and as such was supported by the UN mission, although the mission was criticised for the relationship to the national process being unclear (Boutellis, Mechoulan, and Zahar Citation2020).

Local ‘implementation’ agreements to develop and extend national peace agreement outcomes

Our third type of local agreement comprises those agreements that are used to develop national peace processes in situations where conflict has become fragmented and the conflict fragments threaten to destabilise national peace processes by undermining implementation of national peace agreements. We identify two different types of local agreement.

State-–local ‘mop-up’ agreements

Local agreements that we term ‘mop-up’ are agreements used alongside national peace settlements, between governments and minor insurgent groups operating in distinct areas or with reference to distinct populations. These agreements offer insurgents material resources to disarm, reorganise, and participate in political processes as political parties. They often address local concerns of exclusion and de-development. The peace process in Nepal, for example, saw attention to local conflict in 2006 with the provision of Local Peace Councils.Footnote30 Following the ratification of the 2007 Interim Constitution, the Government of Nepal signed over 40 short bilateral agreements with insurgent ethnic groups, such as the Madheshi Virus Killer Party and Madheshi Mukti Tigers, which often had small membership and military capacity, with organised crime as much a driving factor as political motivations.Footnote31 Part of the impetus for these agreements was the need to ensure a safe environment at the local level for elections: the agreements deal with the localised violence of small groups, and at the same time borderland interface between the central state and its periphery, and between the national and the local. Similar agreements in Colombia saw the state negotiation to end the violence of a range of locally based leftist guerrilla groups as part of a peace process driven by negotiations with the larger Movimiento 19 de Abril, or M-19, which resulted in the Colombian Constitution of 1991. This was a larger scale attempt to use civil society momentum to broaden the reach of the peace process.Footnote32

This type of ‘peace process roll-out’ can be created by national peace process implementation mechanisms. The Kenyan national peace process architecture, for example, rolled out mini processes to address ‘local’ conflict drivers. The National Cohesion and Integration Act No. 12 of 2008 established the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NICC Citation2021) to help implement the national peace process mediated by the African Union after the 2007/8 post-election violence. One of this statutory body’s functions is to mitigate ethnically motivated violence, which it attempts by facilitating and supporting what are often referred to in Kenya as ‘community peace agreements’ in response to longstanding intercommunal and electoral-related violence in different parts of the country.Footnote33 Similarly, also as part of the 2008 process, the National Steering Committee on Peacebuilding Conflict Management (NSC) was empowered to widen to more districts the existing practice of using District Peace Committees to manage conflict in the northern and north-eastern arid and semi-arid parts of the country (NSC Citation2010).

The resulting agreements are signed by long roll calls of officials from neighbouring areas. They operate to redefine the borderlands between localities involved in intercommunal disputes (creating borderland mediation space), and the modalities of passage in and out of these localities for both people and animals (route-of-passage space). They also have trans-scalar dimensions: both communities often agree to ‘invite the state in’, calling for national police and army to police the borderlands between the areas, thereby building and extending state authority towards restoring its monopoly on the use of force in rural areas. The border that is mediated is not just one between conflict communities but also between these communities and the state.

Reconstruction and reconnection agreements

Where large-scale conflict has destroyed physical infrastructure, local agreements are often also needed for reconstruction and reconnection of nationally significant infrastructure, but also the very interpersonal relationships in defined technical spaces – border crossings, railway stations, power stations. One agreement from Sarajevo signed in July 1993 re-established the gas, electricity, and water supply and guaranteed the safety of peacekeepers undertaking repairs.Footnote34 Although the agreement related to the infrastructure of just one of several besieged cities, it was signed between the then Bosnian President, the president of Republika Srpska, and the French Minister for Health and Humanitarian Affairs, and stands on the borderline between national and local agreement, given the national significance of the Sarajevo siege at the time. Throughout conflict between Georgia and Abkhazia in the 1990s, officials and engineers from both sides cooperated to keep the Inguri dam and hydroelectric power station open, due to the fact that it supplied electricity to both sides of the border. The ongoing and ultimately inconclusive geo-national ‘peace process’ had a tripartite geopolitical structure involving political leaders from Russia, Georgia, and Abkhazia. However, below that structure, layers of coordinating mechanisms, committees and working groups often formulated what were – in effect, local reconstruction agreements (Garb Citation1999; Prelz Oltramonti Citation2015, 303). Agreement-making can be devolved down formally or informally, for example in hyper-local cross-border agreements between public servants, with vital importance to nationwide public services that in practice have to be rebuilt in the micro-space of the particular locale in which the service connection has broken down. At an interpersonal level, reconstruction agreements create a local ecosystem of cooperation, but it is an ecosystem with national import, in that it restores or keeps open vital communications and services and enables also the supply of goods. The relationships and services established can often keep going even when national or international peace falters. At an interstate level, the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan, for example, agreed modalities that enabled technical engineers to continue to solve disputes over cross-border water management, which sustained practical cooperation even at the moments of extreme nuclear tension between the two states at the diplomatic level.

Interesting and very different local reconstruction agreements arise in Iraq in the aftermath of the occupation by ISIS with local agreements that simultaneously deal with both physical and relationship reconstruction once ISIS had departed. These town pacts focused on restoring relationships after ISIS had been ‘defeated’ and displaced and were reached between the communities left to deal with the aftermath of ISIS occupation. While not direct ‘peace agreements’ with ISIS, the agreements go much further than physical reconstruction, to address the fractured inter communal relationships left behind by the grey zone forms of co-optation that ISIS had used (see Sanad and USIP Citation2018). They read almost as agreements with the ‘ghost of ISIS’, which remains present in perceptions of degrees of local complicity with ISIS in the persecution of minority groups or women. These physical and metaphysical reconstruction efforts can start to become indistinguishable from on-going conflict resolution and peacemaking, or development projects, or forms of ongoing traditional conflict-resolution. They are focused on creating interpersonal peace, but also civic peace, and form a way of negotiating over what the conflict ‘was about’.

Conclusion: Towards a new imaginary for peace processes

We started with the idea that local agreement-making has been elevated by the premise that local agreements form a bottom-up alternative to a big peace process in contexts where it seems to have been tried and failed multiple times. However, our discussion illustrates the complexity of differentiated practices of local agreement-making which need to be better understood. In conclusion we argue that international engagement often operates without a clear imaginary for how to connect local agreement-making to the national peace process, because there are often multiple, very different processes at play, and their connection to the national is never simple. We set out how our interrogation of the space of local agreements begins to offer a new political imaginary of both conflict and peace process.

Understanding the ‘fragment state’

Local peace agreements are not merely local and not just about peace. They point to the reality that the traditional peace process has neither resulted in stable states, nor left in place a fragile state, but has institutionalised a hyper-fragmented space within the state’s territory the fragment state. The fragment state's invisible institutionalisation is remarkably resilient and impervious to any attempt to create a state architecture. Hyper-fragmentation of conflict is created by a proliferation of armed groups challenging the unitary state. However, fragmentation is also reinforced from ‘above’ – perpetuated by the incentive structures of successive peacebuilding interventions, often rotating through very different types of international mediation. Diverse normative and ‘pragmatic’ international actors, often with incompatible goals, have increasingly become embedded in national and local governance structures. Fragmentation characterises a fluid conflict landscape in which local and international actors can quickly change sides and change partners in ongoing processes of assembling, disassembling, and reassembling. All actors can jump between international, national, and local levels of operation, depending on where they best can achieve their goals.

The local as site of local, national, and geopolitical contest

From this view, sub-state locales have become important spaces for international and national actors to occupy because they are strategic spaces in which to incubate alternative spatial framings for peace or conflict. These conflict landscapes defy the unitary national peace process imaginary, and therefore an overarching narrative of how local peace processes contribute to a national peace process is often impossible. Indeed local agreements reveal how ‘the national’ is often itself merely a ‘local fragment’ with limited geographical and structural reach, itself a would-be fractal of the whole, rather than the whole within which the other fractals are contained. As national peace and transition processes stall, and conflict dynamics mutate, interim state institutions often become increasingly illegitimate and shrunken over time. They are able to manifest and govern only in capital cities, or even merely zones within them, to offer the city centre as a gated community and buffer from the non-institutionalised conflict-scape beyond. Libya, Yemen, and Palestine have even produced de facto competing capital cities, with competing governments and continue to frustrate any concept of national peace beyond one that is itself localised, broken up, and intercommunally conflicted.

To move to a new peace process imaginary requires dealing with this complex shape-shifting world of interrelated conflicts that reach beyond borders. It requires any idea of ‘the’ peace process to be replaced by ‘multi-level interconnected peace processes’. Local actors have become a more central and more complex part of the national picture, because it is a picture of a locally fragmented conflict system. To some extent, international actors are already grappling with this new world, and recognise this fragmentation in reaching out to engage with local agreement practices. However, they lack a language and toolkit to enable them to ground and justify this practice in terms of a clear sense of how it will deliver the national peace they seek. They also find it difficult to understand the complex relationship between projects of peace and projects of war as sometimes coexisting, meaning that they can end up ‘burnt’ when local peacemakers do not play what internationals understand to be the national peacemaking game. Internationals struggle to imagine what the project of ‘scaling up’ looks like because there is no viable central state project to ‘scale up’ to.

Towards a new peace process imaginary

What then is the new peace process imaginary that local agreements point to? It is not yet a completely woven picture. However, it is a story that begins by recognising that the national hierarchical imaginary of state architecture is simply the wrong metaphor through which to understand how state institutions can contain conflict. In place of ‘designing a peace process’ focused on this end, we suggest it is important to begin to understand and map the fragments which operate spatially and conceptually to variously create geographic, group-based, and project-based relationships with capacity for conflict and peace. If the old imaginary was one of architecture, an alternative new imaginary rooted in metaphors of ‘variable geometry’, or even particle physics, should drive analysis of how forces pull individuals and groups together and push them apart, so as to provide a more fruitful image of the type of spaces and places where peace can be created (see McCrudden Citation2015). ‘Fragment mapping’ would point beyond the national peace process imaginary by making visible fragmented conflict that operates in combination as a ‘system’ which must be unwound, rather than ended. Fragment mapping, however, could also usefully reveal the types of networks, relationships, and moments of dialogue and cooperation that make up persistent practices of conflict disruption which exist in the places and spaces the national peace process does not reach or care about.

This is an imaginary that cannot be drawn two-dimensionally, and interestingly the ‘local’ is driving a set of innovative methodologies and ‘ways of seeing’ which could be applied to support new thinking about what the state really ‘looks like’ in place of imagining it in terms of state architecture. Important and detailed ‘micro-level’ peace research projects are beginning to exist, from the small arms network mapping in South Sudan (Small Arms Survey Citation2020), to a ‘sense-making’ research project in Uganda (Amanela et al. Citation2020), to increasingly micro ‘conflict event’ data collection projects (ACLED Citation2021), to everyday peace indicators gathered through mobile phones (Firchow and Mac Ginty Citation2020). Once processes of assembling and disassembling in pursuit of war or peace are better understood, more practical locally driven projects of social justice, which are not dependent on a magical national ‘fix’, can be supported to address conflict.

This type of granulated understanding of locally intertwined peace and conflict process matters because the space of the imagined future nation-state is indeed an imagined and imaginary one. It imagines itself to occupy the whole space of the state with a unified set of institutions that often only really exists on the pages of the peace agreement and the Gantt charts in international offices. There are other games in town, and in cities, villages, communities, and borderlands, that will equally determine the shape of the state that emerges and whether socially just outcomes are possible.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the many contributors and supporters of this work, including Susanne Buckley-Zistel and Annika Björkdahl for their considered responses to earlier drafts. Thanks are due to Robert Forster for his contributions to our earlier work and thinking on local agreements; to Monalisa Adhikari, Sanja Badanjak, Juline Beaujouan, Margherita Distrotti, Tim Epple, and Robert Wilson for their collaborative work with us on the PA-X Local Peace Agreements Database; to Fiona Knäussel for work on the illustration in ; and to Jan Pospisil and the expert contributors and participants of two joint analysis workshops on local peace processes organised by the Political Settlements Research Programme and the British Academy in London and Nairobi in 2019, which moved our thinking forward.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Christine Bell

Christine Bell is a Director of the Peace and Conflict Resolution Evidence Programme (PeaceRep), Professor of Constitutional Law, and Assistant Principal (Global Justice), University of Edinburgh.

Laura Wise

Laura Wise is a Research Fellow with the Peace and Conflict Resolution Evidence Programme (PeaceRep), University of Edinburgh.

Notes

1 Libya: Agreement of Social Honour for the Tribes of Tarhūnah, and the Tribes of Ghriyān, Mashāshiyyah, al-Qal’ah, Yafrin, Jādū, Kābāw, Nālūt, and Wāzin, 8 February 2017.

2 South Sudan: Agreement between the Wonduruba Community and the SPLA Commando Unit, 3 December 2015.

3 Libya: Humanitarian Appeal for Benghazi, 16 March 2016.

4 Burundi: Contract of peaceful cohabitation (neighbourhood Teza ii of Kamenge), Burundi, 30 June 2004.

5 Syria: East Qalamoun Ceasefire, 5 September 2017; Syria: Points of Truce with the People’s Protection Units, 14 April 2014.

6 Yemen: Agreement to Cease Fire between the Tihami Movement in Harah al-Yemen and Ansar Allah, 24 October 2014; Bosnia: Announcement (Ceasefire for Vitez municipality), 22 October 1992.

7 Lebanon/Syria: Arsal 24-Hour Ceasefire Agreement, 5 August 2014.

8 Libya: Accord and Peaceful Coexistence Document between the Al Qadhadhfa Tribe and the Awlad Sulayman Tribe, 4 December 2016. Mali: Commitment to a unilateral ceasefire from Youssouf Toloba and his armed group, Dan Nan Ambassagou, 27 September 2018. Yemen: Agreement between the Houthis and the Arhab Tribes, 9 February 2014.

9 Syria: Decree of the civil administration in the villages of Jbala and Ma'aratamatar, 28 February 2018.

10 Yemen: Dhalea Ceasefire, 20 April 2016.

11 Myanmar: The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) between The Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAO), 15 October 2015.

12 Mali/Azawad: Protocol D'Entente, 27 August 2014.

13 Syria: Levant Front and People’s Protection Units Agreement (Unnamed), 5 February 2015.

14 Bosnia: Joint Statement, 7 November 1993.

15 Pakistan. Ahmadzai Wazir Wana Peace Agreement, 15 April 2007.

16 Croatia: Agreement between the JNA and the Representatives of Ilok, 14 October 1991; Croatia, 8 August 1995. Agreement on the Surrender of the 21st Corps.

17 Syria: ‘Hudna’ (truce) of al-Zabadani, Kefriyya and al-Fu’aa, 20 September 2015.

18 Syria: Homs Hudna Agreement, 7 February 2014.

19 Bosnia: Agreement on the Disarmament of the Able-Bodied Population in the Zepa Enclave, 24 July 1995.

20 Somalia: Adadda Peace Agreement, 10 March 2007.

21 South Sudan: Wunlit Dinka Nuer Covenant and Resolutions, 8 March 1999.

22 Somalia: Final Agreement from the National Reconciliation Council-led Initiative, 15 May 2007.

23 Ethiopia/Kenya, Agreed Minutes of the Second Meeting between Ethiopian Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Regional State and Kenya’s Rift Valley Province Administrators/Commissioners together with Community Representatives, Hawassa, Ethiopia, 2 November 2009.

24 Libya: Joint declaration of the representatives of Touareg and Tebou tribes in 4 points supporting the Presidency Council of the Government of National Agreement which recently took office in Tripoli, 24 April 2016.

25 Colombia: Aguas Lindas Declaration, 31 January 2001.

26 Bosnia: Decisions on Mostar of 12 February 1997.

27 Bosnia: Dayton Agreement on Implementing the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Dayton, 10 November 1995.

28 Bosnia: General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Dayton Peace Agreement), 21 November 1995, Agreement on Inter-Entity Boundary Issues, Article V: Arbitration for the Brcko Area.

29 Central African Republic: Accord entre les Groupes Armes de Batangafo, 24 February 2018; Central African Republic: Accord Entre Les Groupes Armes de Batangafo, 9 January 2019.

30 Nepal: Local Peace Council and its Procedure, 1 September 2006.

31 Nepalese Ceasefire Agreements, 2008–2010, PA-X Peace Agreements Database.

32 See, for example, agreements from Colombia listed on PA-X between 1990 and 1992 (excluding the 1991 Constitution).

33 Kenya: Nakuru County Peace Accord, 19 August 2012.

34 Bosnia: Agreement to restore the public utilities in and around the city of Sarajevo, 12 July 1993.

References

- ABC Colombia. 2019. “Communities in Chocó call on all armed actors in the Colombian conflict to respect International Humanitarian Law”. ABC Colombia, February 15. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.abcolombia.org.uk/communities-in-choco-call-on-all-armed-actors-in-the-colombian-conflict-to-respect-international-humanitarian-law/.

- Agnew, John. 1994. “The Territorial Trap: The Geographical Assumptions of International Relations Theory.” Review of International Political Economy 1 (1): 53–80. doi:10.1080/09692299408434268.

- Amanela, Suleiman, Tracy Flora Ayee, Stephanie Buell, Alice Escande, Tony Quinlan, Anouk S. Rigterink, Mareike Schomerus, Samuel Sharp, and Sarah Swanson. 2020. The Mental Landscape of Post-Conflict Life in Northern Uganda. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). Accessed February 19, 2021. https://acleddata.com/#/dashboard.

- Bell, Christine, Laura Wise, Juline Beaujouan, Tim Epple, Robert Forster, and Robert Wilson. 2021. “A Globalised Practice of Local Peace Agreements.” In Local Peace Processes. London: British Academy.

- Bell, Christine, Monalisa Adhikari, Sanja Badanjak, Juline Beaujouan, Margherita Distrotti, Tim Epple, Robert Forster, Robert Wilson, and Laura Wise. 2020. PA-X Local Peace Agreements Database and Dataset, Version 1. www.peaceagreements.org/lsearch.

- Boutellis, Arthur, Delphine Mechoulan, and Marie-Jöelle Zahar. 2020. Parallel Tracks or Connected Pieces? UN Peace Operations, Local Mediation, and Peace Processes. New York: International Peace Institute.

- Browne, Craig, and Paula Diehl. 2019. “Conceptualising the Political Imaginary: An Introduction to the Special Issue.” Social Epistemology 33(5): 393–397. doi:10.1080/02691728.2019.1652859

- Cavendish, Julius. 2018. “Brokering Local Settlements in Helmand: Practical Insights for Inclusion.” In Incremental Peace in Afghanistan, edited by Anna Larson, and Alexander Ramsbotham, 74–79. London: Conciliation Resources.

- Chatwin, Bruce. 1987. The Songlines. New York: Penguin.

- de Coning, Cedric. 2018. “Adaptive Peacebuilding.” International Affairs 94 (2): 301–317. DOI: 10.1093/ia/iix251

- Dieckhoff, Milena. 2020. “Reconsidering the Humanitarian Space: Complex Interdependence Between Humanitarian and Peace Negotiations in Syria.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (4): 564–586. doi:10.1080/13523260.2020.1773025

- Engle Merry, S. 2006. “Transnational Human Rights and Local Activism: Mapping the Middle.” American Anthropologist 108 (1): 38–51. DOI: 10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.38

- Firchow, Pamela, and Roger Mac Ginty. 2020. “Including Hard-to-Access Populations Using Mobile Phone Surveys and Participatory Indicators.” Sociological Methods & Research 49 (1): 133–160. DOI: 10.1177/004912411772970

- Garb, Paula. 1999. “The Inguri Power Complex.” In Accord: A Question of Sovereignty: The Georgia–Abkhazia Peace Process, edited by Jonathan Cohen, 35. London: Conciliation Resources.

- Goodwin, Deborah. 2005. The Military and Negotiation: The Role of the Soldier-Diplomat. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Haid, Haid. 2018. The Details of ‘Reconciliation Deals’ Expose How They Are Anything But. Chatham House, August. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://syria.chathamhouse.org/research/the-details-of-reconciliation-deals-expose-how-they-are-anything-but-a-closer-look-at-the-regimes-process-reveals-its-real-goal-retribution-and-control.

- Hancock, Landon, and Christopher Mitchell, eds. 2007. Zones of Peace. Boulder, CO: Kumarian Press.

- Humanitarian Dialogue. “Where We Work.” Humanitarian Dialogue. Accessed February 19, 2020. https://www.hdcentre.org/where-we-work/.

- Idler, Annette. 2021. “Local Peace Processes in Colombia.” In Local Peace Processes. London: British Academy.

- Iguma Wakenge, Claude, and Koen Vlassenroot. 2020. Do Local Agreements Forge Peace? The Case of Eastern DRC. Conflict Research Group: Ghent University.

- International Crisis Group. 1997. “Grave Situation in Mostar”. International Crisis Group, February 13. Accessed December 15 2020. https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6a6d240.html.

- Interpeace. 2008. The Search for Peace: Community-Based Peace Processes in South-Central Somalia. Mogadishu: The Center for Research and Dialogue.

- Kappler, Stefanie. 2015. “The Dynamic Local: Delocalisation and (re-) Localisation in the Search for Peacebuilding Identity.” Third World Quarterly 36 (5): 875–889. DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1025740

- Kheirallah, Feras, and Aya Alsafadi. 2021. “A Glimpse of the Tribal Judiciary in Jordan; Peace at all Costs.” In Local Peace Processes. London: British Academy.

- Mac Ginty, Roger, and Oliver P. Richmond. 2013. “The Local Turn in Peace Building: A Critical Agenda for Peace.” Third World Quarterly 34 (5): 763–783. DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2013.800750.

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. A Global Sense of Place in Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McCrudden, Chris. 2015. “State Architecture: Subsidiarity, Devolution, Federalism and Independence.” In The Cambridge Companion to Public Law, edited by Mark Elliott, and David Feldman, 193–214. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McFarlane, Colin. 2019. “The Fragment City and the Global Urban Condition.” In Governing the Plural City, 9–12. London: British Academy.

- Mechoulan, Delphine, and Marie-Jöelle Zahar. 2017. Peace by Pieces? Local Mediation and Sustainable Peace in the Central African Republic. New York: International Peace Institute.

- Millar, Gearoid. 2020. “Toward a Trans-Scalar Peace System: Challenging Complex Global Conflict Systems.” Peacebuilding 8 (3): 261–278. DOI: 10.1080/21647259.2019.1634866

- National Cohesion and Integration Commission. ‘Functions of the Commission’. Nairobi: NCIC. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.cohesion.or.ke/index.php/about-us/functions-of-the-commission.

- National Steering Committee on Peace Building and Conflict Management. 2010. Peace Committees in Kenya: A Mapping Report on Existing Peace Building Structures. Nairobi: NSC. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.christinebukania.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DPC-Mapping-Report-2010-1.pdf

- Pospisil, Jan. 2022. “Dissolving Conflict. Local Peace Agreements and Armed Conflict Transitions.” Peacebuilding 10 (2): 122–137. DOI: 10.1080/21647259.2022.2032945

- Pospisil, Jan, and Florian P. Kühn. 2016. “The Resilient State: New Regulatory Modes in International Approaches to State Building?” Third World Quarterly 37 (1): 1–16. DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1086637

- Prelz Oltramonti, Giulia. 2015. “The Political Economy of a de Facto State: The Importance of Local Stakeholders in the Case of Abkhazia.” Caucasus Survey 3 (3): 291–308. DOI: 10.1080/23761199.2015.1102452

- Price, Roz. 2020. Humanitarian Pauses and Corridors in Contexts of Conflict. K4D Helpdesk, Report 883. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

- Sanad/United States Institute of Peace. 2018. “Announcement of Peaceful Coexistence Pact of Honor for the Tribes in Al- Ayadiyah Sub-District.” ReliefWeb, August 10. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraq-announcement-peaceful-coexistence-pact-honor-tribes-al-ayadiyah-sub-district.

- Small Arms Survey. 2020. “New from HSBA: South Sudan Actors and Alliances Map.” Geneva: Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. Accessed February 19, 2020. http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/about-us/highlights/2020/highlight-hsba-maapss.html.

- Sosnowski, Marika. 2020. “Reconciliation Agreements as Strangle Contracts: Ramifications for Property and Citizenship Rights in the Syrian Civil war.” Peacebuilding 8 (4): 460–475. DOI: 10.1080/21647259.2019.1646693

- Swyngedouw, Erik. 2004. “Globalisation or ‘Glocalisation’? Networks, Territories and Rescaling.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 17 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1080/0955757042000203632

- Thornton, Christopher. 2021. “The Libyan Carousel: The Interaction of Local and National Conflict Dynamics in Libya.” In Local Peace Processes, 22–29. London: British Academy.

- Ullah, Farhat, and Nizar Ahmad. 2021. “The Experience of Local Peace Committees in Conflict-Affected Areas of Pakistan.” In Local Peace Processes, 56–62. London: British Academy.

- United Nations. 2020. UN Support to Local Mediation: Challenges and Opportunities. New York: United Nations.