ABSTRACT

Employing the concept of ‘utility of force' and advancing a new counterpart – the ‘disutility of force' – this article explores why France's military intervention in Mali failed despite a major French material power advantage over the armed groups it was combatting. We explore how France’s military approach, unable to adapt appropriately to a changing context, not only failed to generate political utility in the form of a resolution to the conflict, but actually created disutilities of force that deepened it. This failure reignited postcolonial tensions that both increased the intractability of the conflict and made it harder to change course.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

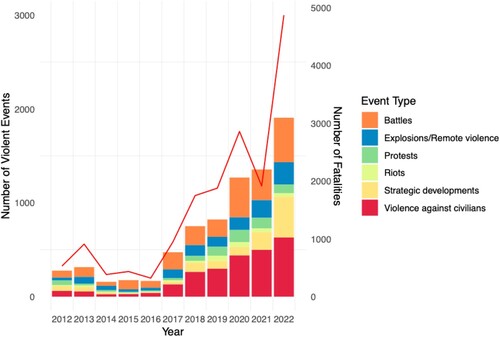

In 2013 France launched Operation Serval to uproot al-Qaeda-linked armed groups from towns they had seized in northern and central Mali. Nearly ten years later, it is hard to characterize France’s intervention as anything other than failure (Pérouse de Montclos Citation2022). Attacks perpetrated by these groups have increased substantially, leading to tens of thousands of fatalities (see ). Militants have spread to neighbouring countries and now threaten West African coastal states. Inside Mali, the military launched two coups and supplanted the former democratic government. Following these developments, in February 2022, France announced the withdrawal of Operation Barkhane (Serval’s successor) from Mali, amidst popular protests against its presence and diplomatic tensions with the Malian junta.

Figure 1. Violent events and fatalities in Mali 2012–22. Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); www.acleddata.com. Bar chart and left-hand y axis depict violent events; line and right-hand y axis depict fatalities.

This situation represents an empirical puzzle. By a very considerable margin, France and its partners in Mali enjoyed a much higher capacity to deploy force than the armed groups they faced. Yet, at a strategic level, they were roundly thwarted. Notwithstanding important differences, like the US and UK in their recent interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, France leaves with a strategic defeat in its wake despite a huge material power advantage.

This article seeks to explain why France failed to defeat these armed groups and improve the security situation in Mali despite this significant material preponderance. Why was France not able to capitalize on the force at its disposal despite a decade of intervention and billions of Euros spent?

We employ the notion of ‘utility of force’ and advance a new closely-related concept – the ‘disutility of force’ – to capture these dynamics. The utility of force is a concept developed to draw attention to the political utility derived from the use of armed force (Smith Citation2005; Angstrom Citation2008). By contrast, we propose the notion of a disutility of force to capture how France’s use of force, rather than provide a means to a political solution, made both the military situation worse and the attainment of a political outcome harder over time.

Other scholars have studied the Malian crisis and highlighted Barkhane’s unrealistic ambitions to eradicate terrorism across the enormous Sahelian region (Goffi Citation2017), criticized the overly militaristic focus of France and its partners (Wing Citation2016; Guichaoua Citation2020), and explored the ‘security traffic jam’ that sees multiple interveners, ineffective coordination, and competing mandates, interests, and priorities (Cold-Ravnkilde and Jacobsen Citation2020; Albrecht and Cold-Ravnkilde Citation2020; Marsh and Rolandsen Citation2021). Charbonneau (Citation2019; Citation2021) has explored France’s ‘counterinsurgency governance’ underpinning a logic of ‘perpetual intervention’ unable to provide sustainable peace, while Gazeley (Citation2022) has argued that France wrongly located the roots of Mali’s security problems in state weakness and thus set the conditions for a return to military rule. Pérouse de Montclos (Citation2020; Citation2022) synthesized these critiques about a ‘mission impossible’ intervention based upon an ill-adapted militaristic strategy which was doomed to fail.

This article makes an original contribution to this literature by examining the failures of France's military approach and analysing the consequences of this failure in a highly charged postcolonial context where suspicions of France are deep-seated. We argue that France’s military strategy in Mali was not only unable to contain the armed groups, but also made the conflict worse. At its root, this stems from a failure to adapt to changes in the character of the insurgency. Militarily at a local level, France and its partners pursued a strategy that exacerbated underlying conflict dynamics and provided opportunities for their opponents, which these groups gladly seized. Meanwhile, politically at a national level, the gap between France’s perceived military power and the very minimal utility derived from this force has over time, in a highly charged postcolonial context, undermined Paris in the eyes of both regional governments and populations, fuelling considerable scepticism surrounding France’s motives and driving a rise of conspiracy theories about France’s actions. At the same time, France’s position as the postcolonial power limited its leverage in Mali and reduced its room for manoeuvre. Taken together, this military failure and the deep political crisis it helped create made France's position in Mali increasingly untenable.

To be sure, France is not solely responsible for this crisis. As we discuss below, the Malian government and armed forces, non-state militias, and international players all contributed (albeit not equally). Nevertheless, our focus is on the French intervention – first Operation Serval (2013–4) then Barkhane (2014–22) – and the wider French-led assemblage of initiatives in Mali and the broader Sahel, which included the European task force Takuba, the G5 Sahel Joint Force, the European Union’s (EU) Training Mission in Mali (EUTM), and its Capacity Building Mission in the Sahel (EUCAP Sahel Mali). We also make reference to the United Nations’ Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), for which France was the penholder.

This article is based on 19 interviews with policymakers, senior officials and local analysts based in Bamako, Dakar, Paris, and Brussels conducted between January 2019 and July 2022, complemented by local and international media reporting on the Malian (and wider Sahelian) conflict, and grey literature and opinion survey data produced by think tanks and non-governmental organizations. This data was then subjected to a directed content analysis to explore the relevant themes of the paper around the character of the war in Mali, the nature of the French operation (including the intersection with other actors’ efforts) and the political utilities and disutilities witnessed.

The article comprises five sections. First, we define the concept of a ‘disutility of force’. Second, we provide an overview of the war in Mali and the French intervention and demonstrate how armed groups’ strategies have shifted over time. Third, we analyse the French-led assemblage’s ‘mal-adaptation’ to the insurgency’s evolution. Fourth, we explore the reasons behind this failure to adapt. Finally, we analyse the political consequences of this failure in a highly charged postcolonial context. Taken together we argue that this has translated into an overall ‘disutility of force’ for France in Mali. A brief conclusion discusses the wider implications of our study.

Conceptualizing the disutility of force

We employ the notion of the ‘utility of force’ and advance a corollary, the ‘disutility of force’, to explore France’s failures in Mali. The idea of the utility of force, popularized by Smith (Citation2005) and further supported by the work of Simpson (Citation2012), refers not to the use of force (the types of forces and weapons systems deployed), but rather its usefulness – that is the political payoff derived from the use of armed force. According to Smith (Citation2005), the utility of force often lies not in the destruction of the enemy (as envisaged in conventional war), but rather in creating a military condition that allows a conflict to be resolved by other (non-military) means. Simpson (Citation2012) further argues that military action taking place among a population is inherently political, and ‘winning’ is thus as much about the perception of third parties as it is defeating the enemy in battle. This is especially important in counter-insurgency contexts (like Mali) where obtaining the support of the affected population is often a key aim – something complicated by the colonial legacies affecting France’s relations with, and perception in, Mali. In these circumstances even a clear military victory may backfire if it is negatively perceived by the population.

In our view, the corollary of the utility of force is that the strategically inappropriate use of force can over time create disutilities of force, which in turn actively create political and military setbacks that make reaching an acceptable political outcome harder than it was in the status quo ante. In such circumstances, misapplied strategy worsens the very situation it was intended to solve as it not only fails to create a military condition that allows the conflict to be ‘resolved through other means’ but also creates military and non-military dynamics that militate against the resolution of the conflict. When an actor is creating disutilities of force, the harder it pushes, the more resources it deploys, and the longer it deploys them for, the worse the situation becomes.

We explore this concept of disutility of force using three complementary notions. Disutility arises when the nature of the force deployed is not strategically appropriate to the context. We analyse France’s strategy in Mali in relation to the evolving nature of the conflict, and pinpoint specific failures to adapt this strategy, despite initial successes. Here we build in part on the work of Arreguín-Toft (Citation2001), who observes that the misapplication of strategy is key in explaining why powerful states lose to weaker opponents, and that of Kilcullen (Citation2010, 2), who considers counterinsurgency as ‘at heart an adaptation battle’ in which one must ‘rapidly develop and learn new techniques and apply them in a fast-moving, high-threat environment […], rapidly changing them as the environment shifts.’ While we do not claim that France’s approach did not evolve at all between 2013 and 2022, we highlight that even when strategic shifts occurred, they were not successful, and ultimately amounted to a ‘mal-adaptation’ to the changing strategic interaction between France and the insurgent groups.

Second, we analyse the factors contributing to this strategic mal-adaptation – the reasons why France failed to adequately adapt its strategy in order to derive utility of force. To do so, we draw from the notion of ‘foreign policy entrapment’ employed by Plank and Bergmann (Citation2021) to explain the evolution of EU foreign policy in the Sahel through path dependencies (deriving from the policy direction set initially) and lock-in effects (caused by subsequent decisions) preventing policy shifts later on. We explore why France was unable to adequately change its strategy using a similar notion of ‘strategy entrapment’, highlighting the weight of the domestic narrative about the intervention in Mali and decision-making structures in Paris, and the lock-in effects of short-term objectives at odds with Barkhane’s overall strategic objectives.

Finally, we analyse the effects of this strategic mal-adaptation on the ground – the practical disutilities of force, one may say – taking into account how the postcolonial context shapes attitudes and perceptions of the military action on all sides. As Gegout (Citation2018, 57) has argued, ‘military intervention takes place in a context of perceived European supremacy over African elites and citizens emanating from Europe's colonial past, and its present military, economic, institutional and cultural superiority over African states.’ While she focuses on how this neocolonial context affects European actors’ motivations to intervene (or not), we argue that postcolonial legacies (including but not limited to neocolonialism) also affect how the intervention unfolds. We also draw upon Guichaoua’s (Citation2020) analysis of how France’s interventionism affects the way it is perceived by Sahelian audiences and its relations with domestic elites. These ‘on the ground disutilities’ further contributed to this strategy entrapment, compounding the problems facing the French intervention until withdrawal was the only possible option.

The war in Mali and the French intervention

The war in Mali finds its roots in the Tuareg rebellion launched in January 2012 by the Mouvement National pour la Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA), a separatist Tuareg group, allied with Islamist armed groups (Whitehouse Citation2021). The rebellion managed to defeat the Malian army on several occasions – benefitting from an unprecedented arsenal at their disposal brought from Libya by Tuareg fighters – and to seize control of several towns across the northern region, fuelling a feeling of humiliation among the armed forces and resentment towards the government of Amadou Toumani Touré, who was toppled in a coup in March 2012. As power in Bamako was officially transferred to an interim civilian government, the rebels expanded their control and proclaimed the independence of ‘Azawad’ on 4 April 2012, effectively cutting Mali in two. However, in most of the area, the MNLA was quickly side-lined by its erstwhile Islamist allies whose objective was not the independence of Azawad, but the implementation of Sharia law across Mali.

As the security situation in northern Mali deteriorated, the UN adopted a resolution allowing the deployment of an African force in Mali in December 2012. However, the incapacity to rapidly deploy this force emboldened the Islamist groups, illustrated by Ansar Dine’s southward incursion with an attack on the Konna army base on 9 January 2013, and galvanized hitherto reluctant French policymakers to intervene directly. French President François Hollande launched Operation Serval on 11 January 2013. France’s 3,500 troops, accompanied by 2,000 Chadian soldiers and the Malian armed forces, recaptured all major population centres in a matter of weeks, leading President Hollande to announce the operation’s successful completion in July 2014. From a military point of view, Serval was almost a ‘classical war’, insofar as there was an identifiable enemy (the violent Islamist groups allied with the MNLA) that could be directly defeated.Footnote1 With the territorial ‘defeat’ of these groups, the deployment of force had demonstrated its core utility – the destruction and removal of the enemy.

This victory however was illusory: what remained of these groups had dispersed into the centre of Mali and neighbouring countries. This led France to transform Serval into a more ambitious regional operation, Operation Barkhane, in August 2014. It recast French military actions in the region as a wide-ranging counterterrorism operation targeting violent Islamist groups, with a mandate to operate across borders with its theatre of operations stretched across five countries: Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad. Barkhane’s aim was twofold: to support the armed forces of the participating countries in their efforts to contain the activities of armed groups, and to help national armies to rebuild so that they could take over counterterrorist operations from French forces and prevent the re-establishment of terrorist sanctuaries in the region.

French operations were supported by an assemblage of initiatives launched by various partners. The European Union launched the EUTM in February 2013 to retrain Malian armed forces, and the EUCAP-Sahel Mali in January 2015 to build the capacity of the Malian police and gendarmerie in crisis management. The UN launched the MINUSMA in July 2013 with a mandate to promote peace and reconciliation and to protect civilians. France would later encourage the launch of military initiatives to ‘share the burden’ with Barkhane, such as the G5-Sahel Joint Force, formally set up in 2017 by Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Niger and Mauritania with strong French encouragement, and the European task force Takuba, a multinational unit set up in 2020 and made up of contingents from several European countries under French command.

The French intervention in Mali aimed at defeating ‘jihadist’ armed groups operating in the Sahel, whose strategies shifted over time – from terrorism, to quasi-conventional warfare, to insurgency – altering the nature of the conflict. These groups include Ansar Dine, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al-Mourabitoun, and Katiba Macina (created by Hamadou Kouffa in 2015) – all of which went on to coalesce within the Support Group for Islam and Muslims (JNIM) in 2017 – and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), the local branch of the Islamic State founded in 2015 (Lebovich Citation2019).

Before 2012, armed groups were already present in northern Mali, most prominently AQIM. At the time, AQIM’s activities consisted in a mix of terrorist operations (including civilian attacks, targeted assassinations, small scale ambushes/suicide bombings against military targets, and kidnapping) and illegal economic activities. During this period, AQIM used violence partly for terroristic effect to add weight to their calls for Sharia and anti-Western invectives, and partly to pursue their economic interests (Chivvis Citation2015, 32–33).

This changed during the 2012 Tuareg uprising. Hamadou Kouffa, who went on to be the leader of the Katiba Macina, was reportedly involved in the seizure of Konna during Ansar Dine’s incursion into southern Mali in 2012 (Zenn Citation2015). In such operations, these groups behaved much like a semi-conventional army – fighting the Malian army symmetrically in battle to gain and hold territory. This strategy allowed them to oust the Malian army, but by massing their forces, also exposed them to French airstrikes (Chivvis Citation2015, 13). These groups did not provide an example of a highly effective conventional force, but the logic of violent action for them was clearly distinct from the previous terrorism-focused actions. Sufficient against the Malian army, this strategy failed against the conventional forces of France.

Following the success of Operation Serval, these groups dispersed across the region, and in many cases embedded themselves within the population. This led to another strategic shift, as they adopted a form of population-centric insurgency. Groups such as Katiba Macina progressively pursued a twin approach which consisted in embedding themselves in existing socio-political grievances between ethnic groups in central Mali, and in presenting themselves as the defenders of the Fulani community, for example by connecting their own ‘jihad’ to the historical ‘Fulani jihad’ of Seku Amadu in the nineteenth century (Ammour Citation2020). The ISGS also adopted a similar approach of ingratiating themselves with Fulani populations, offering a mixture of basic (but nonetheless valued) services and coercion for those who do not work with them (Raineri Citation2022). This engendered a complex quasi-protective, quasi-exploitative relationship with the population.

This population-centric approach can best be described as ‘revolutionary warfare’: a mixture of guerrilla tactics combined with a strategy built on political subversion (Whiteside Citation2016; Stoddard Citation2019). In such circumstances, the utility of guerrilla violence is not to hold ground or defeat opposing forces in battle as in conventional warfare, nor to amplify a political statement as in terrorism, but rather to create the physical and political space for the subversion of society. This is why militants, including Katiba Macina and ISGS, target both prominent leaders and representatives of the state who challenge their legitimacy, as well as military and UN forces who physically challenge their presence.

An insurgency's focus on the population does not mean that it is benign, nor that it treats all civilians well. Katiba Macina and ISGS are violent to those they perceive as cooperating with their enemies, and have exacerbated conflicts with Dogon and, to a lesser extent, Bambara communities, fuelling violence against Fulanis (International Crisis Group Citation2020). These groups present themselves as protectors of Fulani communities, but this is often from violence that they have themselves helped to trigger. This strategy has contributed to destabilizing the Malian state’s abilities to reassert itself in central Mali, and subsequently triggered the use of violent state-aligned non-state actors (Ammour Citation2020).

In the context of the Sahel, as elsewhere, the armed groups in question are often labelled ‘terrorists’. While this is rhetorically appealing and contains an important element of truth insofar as these groups do use the tactic of terrorism, it is only partly accurate as terrorism remains only one, and in some cases a declining, feature of these groups’ military repertoire (Hassan Citation2019; Pérouse de Montclos Citation2018). The strategic shift these groups operated – from terrorism to quasi-conventional warfare to insurgency – changed the nature of the conflict. Our contention is that France and its partners failed to adapt accordingly, thus creating disutilities of force which only made the situation worse as time went on.

Mal-adaptation of a mis-matched strategy

The character of the security challenges facing Barkhane in 2014 were very different from those faced by Serval earlier. By then, armed groups had mostly dissolved into the population in the centre of Mali and in neighbouring countries. Barkhane thus faced a conflict more akin to a localized insurrection and intercommunal conflict than to either a conventional war or terrorism. It therefore required a concept of operations closer to counterinsurgency, in which providing support to the population is crucial to insulate them from the insurgent groups and to ensure peaceful relations between communities.

From the French military’s point of view, the shift from the Mali-focused Operation Serval to the regional Operation Barkhane was a way to adapt their strategy to the evolving nature of the security threat.Footnote2 However, despite this geographical adaptation, military action remained focused primarily on eliminating the ‘terrorist’ threat, and the French military neither fully appreciated nor sufficiently addressed the fundamental change in the armed groups’ strategy (Michel Citation2023, 66–69). Indeed, rather than isolate the militants and protect the targeted communities, Barkhane’s strategy was to directly pursue the armed groups wherever they were operating across the Sahel region, thus maintaining a counterterrorist approach.Footnote3 This yielded minimal security payoff. The ‘neutralization’ (to use the French military’s favoured term) of prominent combatants, such as Abdelmalek Droukdel, the head of AQIM, and Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui, the head of ISGS, brought no obvious improvement to the human security situation (Pérouse de Montclos Citation2022, 21–22). For these armed groups, whose structure is diffused and decentralized, losing leaders is a setback but not an overall impediment to their long-term success, and they have proven able to find new leaders fairly easily.Footnote4 The core of these insurgents’ strategy was control over the population, which provided the cover, intelligence, resources, and people power they needed. France’s counterterrorist, enemy-centric operations and the need to prioritize force protection, which greatly reduced the mobility of French forces and thus their ability to protect the population (Michel Citation2023, 68–69), meant that they were unable to adequately respond to this change in the insurgents’ strategy.

By 2017 it was clear that France’s approach was not working, as the security situation was continuing to deteriorate (see ). The election of Emmanuel Macron to the French presidency in May 2017 prompted some shifts in the French approach, driven by Macron’s fear that France was getting bogged down in the region.Footnote5

First, Macron actively promoted the creation of the G5 Sahel Joint Force, a regional taskforce comprising troops from the five countries involved in the G5 Sahel, namely Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger (Dieng, Onguny, and Mfondi Citation2020). The objective was to build up the Joint Force so that it could take over from Barkhane, and effectively secure borders and conduct cross-border counterterrorist operations, thus allowing France to pull back from frontline military operations – an exit strategy which had been sorely lacking (Desgrais Citation2019). However, the Joint Force was barely operational in practice, and was put to rest in 2022 by Chad’s decision to pull away its troops from Niger and Mali’s sudden decision to leave the regional alliance (Sandnes Citation2023)

Second, increasingly recognizing the logistical challenge of operating across a vast area and difficult terrain nearly twice the size of western Europe, the French forces reviewed the scope of their operation and sought to rely on other actors. From 2017, they decided to concentrate their military efforts on the so-called ‘Three Borders’ zone between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger (where ISGS was active).Footnote6 They also cooperated with other actors, including the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa), as well as with self-defence militias such as the Imghad Tuareg Self-Defence Group and Allies (GATIA), which by this time was working with the Malian government in the fight against ISGS (Thurston Citation2018).

Collaboration was also necessary in their pursuit of an ‘oil spot’ strategy – a strategy first developed in colonial times – aimed at securing conquered zones by restoring public order and civilian authority, before going on to conquer new areas, as laid out in 2019 by the French Army’s Chief of Staff (Assemblée Nationale Citation2019; see also Dabo 2019). However, while Barkhane had the military power to wrest control of territory from armed groups, they did not have sufficient troops on the ground to hold that territory once they left to take on armed groups in another area.Footnote7 France thus relied on other actors, notably the FAMa and the MINUSMA, to provide protection and services to the populations of these areas, in a ‘division of labour’ between counterterrorism and peacekeeping (Charbonneau Citation2017).

The problem was that MINUSMA did not have sufficient resources to hold areas that French forces had liberated from the control of the armed groups (van der Lijn et al. Citation2019). Although from 2018 its mandate included to ensure prompt and effective responses to threats of violence against civilians and to prevent a return of armed elements to liberated areas, this was to happen ‘within existing resources’, meaning that it was in practice impossible for MINUSMA forces to effectively secure the areas liberated by Barkhane.Footnote8 Moreover, the Malian government’s lack of political will to tackle the armed groups further undermined the ability of the FAMa and MINUSMA to tackle the insurgents (Nsaibia and Duhamel Citation2021).Footnote9 As a result, armed groups simply moved back in when French troops left.Footnote10 This also impacted intelligence collection, as people were unwilling to provide information to French troops for fear of reprisals when the groups returned.Footnote11 The population control strategies employed by the militants thus continued relatively unimpeded.

Meanwhile, the well-documented human rights violations committed by the FAMa and the self-defence groups working with them – including GATIA but also Dogon militias – particularly against Fulani communities, ran against the armed forces’ mandate to protect local populations (Human Rights Watch Citation2018; Benjaminsen and Ba Citation2021). Indeed, both the militias and the FAMa have targeted civilians for their perceived support for militants rather than helping to protect them from predatory armed groups (Ibrahim and Zapata Citation2018). This has prevented the expected stabilization of conflict-affected communities, but has also been one of the drivers that have pushed some Fulani to join armed groups offering ‘protection’ against the army and pro-state militias (International Crisis Group Citation2020; see also Raineri Citation2022; Bøås, Wakhab Cissé, and Mahamane Citation2020). Barkhane’s cooperation with the FAMa and – until 2018 – with GATIA harmed the way France and its international partners were perceived by local populations, delegitimizing Barkhane and, by association, its international partners, who were seen as at best irrelevant to, and at worst complicit in, these violent dynamics (Pérouse de Montclos Citation2020, 42–48). The violence deployed by French soldiers themselves – increased by the ‘war on terror’ narrative (Daho, Pouponneau, and Siméant-Germanos Citation2022, 112–14) – should not be understated either, including France’s use of high-casualty airstrikes (Gazeley Citation2022, 280). This was best illustrated in January 2021, when a French airstrike targeted a wedding celebration, killing at least 21 civilians. This incident – and the way it was communicated about by French authorities – unsurprisingly fuelled resentment against the French intervention (Vincent, Bensimon, and Lorgerie Citation2021).

Meanwhile, increasingly recognising the limits of a narrow counterterrorist approach, France made some attempts to demilitarize policymaking and to coordinate security, aid, and development actions in the region. For example, President Macron appointed Jean-Marc Châtaigner as Special Envoy for the Sahel, got the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) more involved, and launched the Sahel Alliance, together with Germany, the EU, the African Development Bank, the World Bank, and the United Nations Development Programme, to promote international cooperation for governance, internal security, and development initiatives in the G5 Sahel countries. The Sahel Alliance was supposed to provide a response to the deeper issues plaguing the region standing in the way of peace and stability. In January 2020, during a summit of the G5 Sahel heads of states with President Macron, a new initiative dubbed ‘Coalition for the Sahel’ was announced, with the aim to integrate and better coordinate the security and development objectives. A year later, President Macron announced a ‘sursaut civil’ (civilian surge) to accompany the surge of troops operating under Barkhane to 5,100.

Despite this, aid flows were primarily an instrument in support of counterinsurgency measures and were seen as a way of providing legitimacy to the French military operation. Although the Sahel was declared a foreign policy priority, the five Sahel states accounted for only 10 percent of total French development assistance to Africa in 2018. Mali, in particular, was receiving only 2.5 percent, a level of funding that has remained broadly unchanged since 2013. This shows the discrepancy between declared political priorities and the actual allocation of funds (Erforth and Tull Citation2022). Moreover, if the hope was that this discrepancy would be addressed by bringing other donors on board through the launch of the Sahel Alliance, their impact was limited. Ultimately, the ‘sursaut civil’ did not happen, and the main focus of the French intervention remained the military dimension.

Coordination between EU services and instruments designed to fill this ‘population protection’ gap was also less than optimal. EUCAP Sahel Mali was responsible for supporting the reform of the security sector and assisting the police and gendarmerie, with a view to reassert the state’s authority across the country, while the Sahel Alliance was supposed to coordinate development initiatives. However, EUCAP Sahel-Mali was under-resourced for the scale of the task and hampered by short mandates and frequent staff turnover, making it impossible to develop long-term, locally-grounded strategies (Marsh and Rolandsen Citation2021, 623–24). In addition, competition between EU actors over project implementation impeded their effectiveness. For example, the EU undertook various security initiatives that were not coordinated with EUCAP Sahel Mali, such as the Support Programme to Strengthen Security in the Mopti and Gao regions and to manage border areas (PARSEC), launched in 2016, or the Prevention of Conflict, Rule of Law/Security Sector Reform, Integrated Approach, Stabilization and Mediation (PRISM) unit created within the European External Action Service (EEAS) in 2017 (Lopez Lucia Citation2019).

Problems of coordination resulted from the fact that stakeholders in Brussels and on the ground had diverging views and priorities. Competition and leadership struggles among these stakeholders further harmed coordination and implementation (Lopez Lucia Citation2019). Finally, as the human rights abuses documented above demonstrate, the EUTM’s efforts at retraining the Malian army, which included training in international human rights law, clearly did not translate into its military practice (Tull Citation2019, 406).

In summary, the French strategy in Mali did not adapt successfully to the changing nature of the conflict it faced. We do not claim that the military were unaware of the changes that were taking place on the ground – as our interviews with senior French military officials showed – or of the need to maintain the confidence of the population, without which no external military operation can succeed, and indeed there were some attempts at changing course. Rather we suggest that there was no comprehensive shift in the French-led military strategy to meet this challenge, and that the evolution of French strategy ultimately amounted to a mal-adaptation.

Strategy entrapment: Why did France fail to adapt?

Why was France unable to make the necessary changes to its strategy? Changing direction once overall strategy has been agreed is never easy. The process of bringing the many political and military actors involved together, in this case at both national and international level, to establish an agreed strategy and deliver it, takes time and is far from straightforward. A change of strategy is thus difficult, not least because to do so could be seen as an admission of the failure of the original strategy.Footnote12

This was compounded by the multiplicity of actors involved and the lack of coordination between them, as discussed above. France was relying on other actors – the Malian state, MINUSMA, EU initiatives – to deliver population-centric elements, but as we have previously shown, these actors faced major challenges in their ability to deliver this part of the strategy, and the Malian government lacked the political will to do so. As a result, the French strategy remained focused on the military response to the crisis and was unable to deliver improvements to the security situation for the majority of the population. Yet the question remains: why, as these problems became increasingly clear, were the necessary strategic changes not made?

We argue that two sets of dynamics led to ‘strategy entrapment’ – a concept derived from Plank and Bergmann’s (Citation2021) notion of policy entrapment. On the one hand, domestic imperatives greatly constrained any shift away from counterterrorism to a more population-centric approach. The French public narrative focused on the ‘jihadist’ ‘terrorist’ threat these groups represented for French interests and the need to ‘neutralize’ the leaders of these groups (Pérouse de Montclos Citation2020, 108–09). The need to satisfy their domestic constituency (French voters) made it easy for the French government to rationalize the immediate need to focus on the use of force, and distracted attention – and resources – from addressing deeply problematic governance practices in Mali. Meanwhile, the maintenance of a privileged sphere of influence in west and central Africa is seen as central to France’s role, and its perception of itself, as a global power. Policymakers in Paris see the French military as playing a fundamental role in enabling this. Moreover, external operations are central to the strategic culture of the French army (Leboeuf and Quenot-Suarez Citation2014; Powell Citation2017). Internal power struggles for primacy in the determination of French policy in Mali between the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in which the former was able to carve out for itself the preponderant role, also constrained any strategic shift to less militaristic approaches (Daho, Pouponneau, and Siméant-Germanos Citation2022, 101–26).

On the other hand, a tension emerged between short-term objectives – making quick counterterrorist ‘wins’ and pulling French troops out – and the long-standing objectives of the French intervention to facilitate the reassertion of Malian state sovereignty across the country and bring peace and stability to the region. This tension was even harder to disentangle considering the human rights violations perpetrated by the FAMa and the militias working with them. The tactical decision to support certain armed groups, such as GATIA, as part of the fight against terrorism, meant in effect accepting, or at least turning a blind eye to, the risk of severe human rights abuses, which undermined the strategic goal of defeating the insurgency. Meanwhile, the level of evidence required to restrain and pressure a partner government, and the level of political capital expended in order to do so, is very high, especially as this could open France to further accusations of neocolonialism and quite quickly deteriorate the relationship between France and Mali.Footnote13 On the other hand, France’s exit plan relied on developing the capacity of the FAMa and having them take control of security provision.Footnote14 As such, highlighting very vocally their abuses and the mistakes they made, or placing significant public pressure on the FAMa, would signal that the French strategy to leave was flawed, while also widening the gap between France’s exit strategy and Barkhane’s on-the-ground strategic objective of containing the insurgency.

In summary, France’s ability to make the necessary changes to its strategy in Mali were constrained. The initial narrative describing the intervention as a fight against ‘terrorism’ (and this portrayal to domestic audiences) and the dynamics of decision-making regarding the Sahel in Paris created path dependencies that made it difficult to shift course. Meanwhile, short-term objectives and choices made to meet them (such as partnering with militias in counterterrorist operations) further constrained France’s ability to successfully adapt to the changing context, which in turn created political disutilities of force on the ground.

‘On the ground’ disutilities of force in a postcolonial context

The French intervention, because it failed to adequately adapt to the changing character of the conflict, was unable to improve security in the conflict-affected areas of the country. Yet we argue that this failure had broader consequences that made the French presence increasingly untenable. France’s failure to improve security despite the (perceived) means at its disposal fuelled negative sentiment towards France in Mali and across the region. The postcolonial context provided fertile ground for this sentiment, which the Malian authorities could effectively exploit in their own quest for legitimacy following the 2020 coup.

France’s Operation Serval had initially aroused euphoria among Malians, who perceived it as a force of liberation that had protected Malian sovereignty and restored the country’s territorial integrity.Footnote15 A Malian newspaper recalled how ‘[i]n 2013, French soldiers were welcomed like heroes by cheering crowds along the road as they passed by’ (Sylla Citation2022, our translation). But by mid-2014 already, French forces were no longer seen as a neutral broker between the different parties to the Malian conflict. Polling data from Mali-Mètre, an initiative of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Bamako, illustrates this shift in popular perceptions. While 3 out of 4 Malians deemed the French intervention necessary at the end of 2012, and even had a positive view of the French military presence in 2013, popular support for Operation Barkhane dwindled over the following years, and plummeted in November 2019 when 79 percent of respondents stated they were not satisfied with it.Footnote16 Another opinion poll carried out in Bamako in January 2022 recorded 96 percent of negative opinions regarding the French presence (Guindo Citation2022). Although this should be treated with caution and is not necessarily representative of views outside of the capital, it is nonetheless indicative of a significant perception among parts of the Malian population. This growing hostility was dramatically illustrated when, in November 2021, protesters held up a French military convoy for several days along its course through Burkina Faso and Niger (Bensimon and Vincent Citation2021).

The failure of the French-led intervention to improve security despite the military resources at its disposal and its history of colonial domination were increasingly perceived by Malians as surprising and suggested that France was, at best, not trying very hard or, at worst, actively assisting the armed groups. The perceived supremacy of France, derived from its colonial past and its military superiority over African states highlighted by Gegout (Citation2018, 57), shaped popular expectations towards the French intervention. In the popular imagination, it was hard to fathom how a country that had controlled the whole region through a system of colonial rule could fail to quell a few thousand jihadists. As Haidara (Citation2020) noted, ‘the reality is that it seems difficult for many [in the Malian] population to believe that Barkhane and the MINUSMA – given the considerable means at their disposal – are really incapable of reducing the harmful power of armed terrorist groups, or at least of protecting them against these groups’.

Perceptions were also influenced by the asymmetry at play between France and the armed groups inherent to guerilla-type warfare. Because the French military and their partners had a far stronger military capacity than the militants, their military successes provided little political pay-off for them among the wider Malian population. French successes at a tactical level were expected, and even significant ‘wins’, such as the removal of a prominent leader, were undermined by the inevitable next large-scale attack. Short-term tactical successes brought few political benefits, and the benefits they did accrue diminished over time. By contrast, significant victories for the insurgents, such as the attacks at Idelimane in 2019 where dozens of Malian soldiers were killed, significantly undermined popular support for France’s military presence and operations, and signalled to local, national, and international players that the insurgency could not be eliminated – and to some that France was not trying (Nsaibia and Duhamel Citation2021; Pérouse de Montclos Citation2020, 48).

Meanwhile, some of the French army’s actions proved controversial, such as the establishment of military bases in the country – something Mali’s first president, Modibo Keita, had fiercely refused in 1961 (Mali Demain Citation2014). Another example was France’s refusal to help the Malian army retake Kidal – in the North – from the MNLA in May 2014, an operation which resulted in the death of 50 Malian soldiers. This, coupled with France’s joint patrols with Tuareg militias, fuelled rumours that Paris was seeking to partition Mali (Tull Citation2021, 160). As time went on and security deteriorated, the French deployment of force was increasingly seen, not as protecting Malian sovereignty, but as facilitating a form of ‘internationalized government’, in which local political elites were complicit and which many Malians experienced ‘as a humiliation and violation of the country’s sovereignty’ (Tull Citation2021, 153).

This growing dissatisfaction with the French army’s presence was accompanied by a multiplication of conspiracy theories about the purported ‘true’ reasons for the French intervention among sizeable sections of the Malian population, which have proliferated on social media. This has included videos purporting to show French troops supplying motorcycles to jihadistsFootnote17 (Faivre Le Cadre Citation2019), photos allegedly showing French soldiers stealing gold from a Malian mineFootnote18 (Galan Citation2021), or a video described as showing Malian customs dismantling a gold smuggling operation perpetrated by French soldiers upon orders from the Elysée PalaceFootnote19 (Pezet Citation2019). These conspiracy theories have been spread by prominent individuals, such as Malian singer Salif Keita and politicians such as Oumar Mariko, president of the leftist political party Solidarité Africaine pour la Démocratie et l’Indépendance (SADI), helping get them traction among the population (Haidara Citation2020).

The suspicion of France and its motives is deeply rooted in the Malian experience of French colonialism. For example, the perception that France was in alliance with the MNLA has its origins in the colonial period, when the Tuareg occupied a privileged place in the French colonial imagination, including being exempted from forced labour and military conscription (Lecocq and Klute Citation2013). Today, many Malians, particularly but not only among the governing elites in Bamako, believe that France continues to harbour sympathies for the Tuareg and that it had secretly agreed to hand Kidal, which the Malian army was not allowed to enter, over to the MNLA (Tull Citation2021).

France was also constrained in how far it could push the Malian government to act by its status as the former colonial power. Indeed, one could argue that it had used up its ‘moral capital’ in the north and any attempt to undertake a more extensive military intervention into the centre of the country, or indeed any concerted attempt to tell the Malian government what to do, would have risked France being accused once again of neocolonialism.Footnote20

The problem of being the former colonial power was compounded by the lack of consistency in France’s policymaking in the region. In 2019, French troops were deployed to support Chadian President Idriss Déby's efforts to quell a rebellion in the north of the country by bombing rebel convoys that were converging on N’Djamena. This fell completely outside Barkhane’s mandate, which was to carry out counterterrorist operations against jihadist forces (seen as everybody's enemy) – not to protect an authoritarian ruler’s regime. In 2021, after Président Déby’s death, France endorsed the unconstitutional power grab by his son, General Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno – even though France had consistently criticized the Malian junta since it seized power in two military coups in 2020 and 2021 and insisted that new elections should take place by February 2022. This has led to accusations that France applies double standards in its dealings with Sahelian governments, discrediting its role and the motivations behind its presence in the region.

Flat-footed reactions by French leaders – themselves rooted in (neo)colonial cultures and attitudes – have also added fuel to the fire. A significant example was when, following the death of 13 French soldiers in Mali in November 2019 and amidst growing popular protests against the French intervention across the region, President Macron ‘summoned’ the heads of states of the Sahelian countries to a summit in Pau, and demanded their clear re-commitment to the French presence (Guichaoua Citation2020). French authorities have routinely treated any criticism as ingratitude, rooted in the narrative that France was fighting against ‘jihadist barbary’ and terrorism in the Sahel (Pérouse de Montclos Citation2020, 118–27) – an attitude perceived as arrogant and neocolonial in Mali and across the region (see Diop et al. Citation2020).

While France’s failings created disutilities of force, and the postcolonial context provided a fertile ground for criticism, suspicions, and conspiracies to take hold, the Malian authorities also played a part. The focus of this paper has been on the French-led intervention, but we do not deny the agency of the Malian governing elite, who used this opportunity to strengthen their own legitimacy. Assimi Goïta orchestrated a coup toppling Ibrahim Boubacar Keita in August 2020 amidst massive anti-government protests, and consolidated his military regime in a second coup in May 2021. Since then, the Malian authorities have made repeated allegations against France’s presence in the country. For example, in a speech in February 2022, Prime Minister Choguel Kokalla Maiga stated that ‘hundreds and hundreds of Malians have been massacred over the years despite the presence of over 50,000 soldiers: the armed forces of Mali, Barkhane, Takuba, G5 Sahel, EUCAP, EUTM’, and that ‘despite this massive presence of international forces, Malians, every day, continue to lose their parents, their children and their loved ones’.Footnote21

As Guichaoua (Citation2020, 911) argued, the manner in which the French intervention was carried out ‘created space for vocal contestation articulated around national sovereignty.’ In this context, the military authorities have been able to both take advantage of and contribute to the growing resentment against France and its international partners in order to project themselves as the true protectors of Malian sovereignty, and to shift the blame for the persistent lack of security away from the FAMa (and the Malian state).

Ultimately, the French intervention failed to reach its objective to improve human security in Mali and the region, but its inability to adequately adapt had further consequences on the ground. Within a charged postcolonial context, this further undermined the way France was perceived by the population and its relations with the new Malian authorities in quest of domestic legitimacy, making the situation worse over time and inevitably leading to failure.

Conclusion

Ten years after the launch of Operation Serval, Barkhane has left the country without having achieved its objectives and leaving behind no tangible improvement in the security context, as the cycle of violence continues in Mali and continues to spread across the region (Powell Citation2022). In June 2023, the Malian government also demanded the withdrawal of MINUSMA, which was voted by the Security Council shortly afterwards and is now underway. Meanwhile, Mali has increased its cooperation with the Russian-owned Wagner group, which has seen increased violence against civilians and little counterinsurgency impact (Gurcov and Héni Nsaibia Citation2023). The French presence in the Sahel is further threatened following military coups in Burkina Faso and Niger.

Admittedly, we do not know what would have happened if France had not intervened, or if the intervention had been carried out differently – though the narrative that without it, Mali would have fallen under the control of jihadist groups in a scenario akin to the Taliban’s seizure of Afghanistan has since been largely refuted (Pérouse de Montclos Citation2022). However, this is not what is at stake here.

What this article has shown is that the French-led intervention in Mali – despite the military means at its disposal – failed to adequately adapt its strategy to an evolving context. While the conflict shifted away from terrorism, then quasi-conventional warfare, to a guerilla-type insurgency, France’s intervention remained focused on counterterrorism and relied on other actors to fill the population-protection gap in its strategy (which they were not able to do). France did not manage to use its military forces to help create a condition that would allow the conflict to be solved by other means, but instead provided opportunities for the armed groups Barkhane was combatting, which they duly seized.

This mal-adaptation was driven by a strategy entrapment dynamic rooted in domestic imperatives underpinning decision-making on the war in Mali, and tensions between Barkhane’s more immediate goal of presenting counterterrorism ‘wins’ and the longer-term strategic need for an exit strategy.

We argue that by failing to adapt, the French intervention not only failed militarily in improving security in the conflict-affected parts of the country, it also made the situation more untenable. France’s military failure despite the (perceived) means at its disposal has fuelled negative sentiment towards its presence in Mali and across the region. The postcolonial context has provided fertile ground for this sentiment, while the Malian military regime has also effectively exploited it to build their own legitimacy. Overall, despite the resources spent and force used in Mali, France’s misaligned strategy meant it drew minimal utility while at the same time generating considerable disutility from this force.

This article has focused on the French intervention. This does not mean that we believe that France is solely responsible for the current situation. In addition to the failures of other international actors involved in the Sahel’s ‘security traffic jam’ (Cold-Ravnkilde and Jacobsen Citation2020), the Malian government under President Ibrahim Boubakar Keita had numerous opportunities to enact the necessary political reforms and begin to restore government services, but failed to do so. The status quo brought some advantages to political elites in Bamako, who could delegate security provision to outsiders, thus evading responsibility for their own failures and claiming this foreign presence constrained their sovereign power (Tull Citation2019, 421). The current military regime has continued with a military-focused strategy to address the crisis, but it remains unclear how or if this can improve the human security situation in the country.

By focusing on France’s intervention in Mali, we contribute to a growing literature looking critically at foreign interventions, especially those underpinned by postcolonial legacies (Charbonneau Citation2016; Gegout Citation2018; Pérouse de Montclos Citation2020; Guichaoua Citation2020), and arguing for the importance of reflexivity over time in military strategy, in order to ensure that political and military strategy are aligned. The concept of the ‘utility of force’ draws our attention to how strategies support (or not) political outcomes. The new corollary that we have advanced here – the disutility of force – highlights how misconceived strategies that are not grounded in a sound understanding of the conflict can actively compound the conflict dynamics and make them harder to resolve.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Edoardo Baldaro, Elisa Lopez Lucia and Amy Lavery for their support and assistance in writing this article and the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. All errors of course remain our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eloïse Bertrand

Dr Eloïse Bertrand was recently appointed Assistant Professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. Previously, she was a Research Fellow at the University of Portsmouth.

Tony Chafer

Tony Chafer is Emeritus Professor of African and French Studies in the Centre for European and International Studies Research (CEISR) at the University of Portsmouth.

Ed Stoddard

Dr Edward Stoddard is a Reader in International Security in the CEISR at the University of Portsmouth and an Affiliated Researcher at the Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Pisa.

Notes

1 Interview with senior French military officer, Bamako, February 2019.

2 Interview with senior French military officer, Paris, March 2019.

3 Interview with senior French military officer, Bamako, February 2019.

4 Phone interview with former French ambassador to Mali, July 2019; interview with former French senior military officer, Bamako, January 2019.

5 Interview with a senior French military officer, Paris, March 2019.

6 Phone interview with former French ambassador to Mali, July 2019; interview with former French senior military officer, Bamako, January 2019.

7 Interviews with senior French military officer, Bamako, February 2019 and with senior British military officer, Dakar, March 2019.

8 Interview with senior UN official, Bamako, June 2022.

9 Interviews with senior UN official, Bamako, January 2019; phone interview with former French ambassador to Mali, Paris, July 2019.

10 Interview with senior French military officer, Paris, December 2020.

11 Interview with Lori-Ann Benoni, Institute of Security Studies, Dakar, March 2019.

12 Interview with official from the Partnership for Security and Stability in the Sahel, European External Action Service, Brussels, April 2022.

13 Interview with official from the Partnership for Security and Stability in the Sahel, European External Action Service, Brussels, April 2022

14 Interview with a senior French military officer, Paris, March 2019.

15 Interview with a senior French military officer, Paris, July 2019.

16 Data was extracted from the Mali-Mètre reports available on the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung’s website: https://mali.fes.de/mali-metre

17 These motorcycles had indeed been transported by Barkhane but were in fact supplied to the FAMa.

18 These photos were of American soldiers in Iraq during the seizure of gold shipments.

19 The video was in fact filmed in Ghana.

20 Phone interview with former French ambassador to Mali, July 2019.

21 Speech made by Prime Minister Dr Choguel Kokalla Maiga in Ségou for the Ségou Art 2022 opening ceremony on 4 February 2022. Accessible at https://www.facebook.com/GandhiMalien1/videos/318722123603857/?extid=NS-UNK-UNK-UNK-AN_GK0T-GK1C

References

- Albrecht, Peter, and Signe Cold-Ravnkilde. 2020. “National Interests as Friction: Peacekeeping in Somalia and Mali.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14 (2): 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2020.1719789.

- Ammour, Laurence-Aïda. 2020. ‘How Violent Extremist Groups Exploit Intercommunal Conflicts in the Sahel’. Africa Center for Strategic Studies (blog). 26 February 2020. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/how-violent-extremist-groups-exploit-intercommunal-conflicts-in-the-sahel/.

- Angstrom, Jan. 2008. “Introduction: Exploring the Utility of Armed Force in Modern Conflict.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 19 (3): 297–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592310802228641.

- Arreguín-Toft, Ivan. 2001. “How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict.” International Security 26 (1): 93–128. https://doi.org/10.1162/016228801753212868.

- Assemblée Nationale. 2019. ‘Audition du Général François Lecointre, Chef D’état–Major des Armées’. Compte Rendu 12. Commission des Affaires étrangères. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/15/comptes-rendus/cion_def/l15cion_def1819042_compte-rendu.pdf.

- Benjaminsen, Tor A., and Boubacar Ba. 2021. “Fulani-Dogon Killings in Mali: Farmer-Herder Conflicts as Insurgency and Counterinsurgency.” African Security 14 (1): 4–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2021.1925035.

- Bensimon, Cyril, and Elise Vincent. 2021. ‘Au Sahel, un Convoi de L’armée Française Face à la Colère populaire’. Le Monde, 30 November 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2021/11/30/au-sahel-un-convoi-de-l-armee-francaise-face-a-la-colere-populaire_6104159_3212.html.

- Bøås, Morten, Abdoul Wakhab Cissé, and Laouali Mahamane. 2020. “Explaining Violence in Tillabéri: Insurgent Appropriation of Local Grievances?” The International Spectator 55 (4): 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2020.1833567.

- Charbonneau, Bruno. 2016. France and the New Imperialism: Security Policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. London and New York: Routledge.

- Charbonneau, Bruno. 2017. “Intervention in Mali: Building Peace Between Peacekeeping and Counterterrorism.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35 (4): 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2017.1363383.

- Charbonneau, Bruno. 2019. “Faire la Paix au Mali: Les Limites de L’acharnement Contre-Terroriste.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des études Africaines 53 (3): 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2019.1666017.

- Charbonneau, Bruno. 2021. “Counter-Insurgency Governance in the Sahel.” International Affairs 97 (6): 1805–1823. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab182.

- Chivvis, Christopher S. 2015. The French War on Al Qa’ida in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cold-Ravnkilde, Signe Marie, and Katja Lindskov Jacobsen. 2020. “Disentangling the Security Traffic Jam in the Sahel: Constitutive Effects of Contemporary Interventionism.” International Affairs 96 (4): 855–874. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa093.

- Daho, Grégory, Florent Pouponneau, and Johanna Siméant-Germanos. 2022. Entrer en Guerre au Mali : Luttes Politiques et Bureaucratiques Autour de L’intervention Française. Paris: Editions Rue d’ULM.

- Desgrais, Nicolas. 2019. ‘Cinq ans après, une radioscopie du G5 Sahel.’ Paris: Observatoire du monde arabo-musulman et du Sahel, Fondation nationale pour la recherche stratégique. https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/programmes/observatoire-du-monde-arabo-musulman-et-du-sahel/publications/201913.pdf.

- Dieng, Moda, Philip Onguny, and Amadou Ghouenzen Mfondi. 2020. “Leadership Without Membership: France and the G5 Sahel Joint Force.” African Journal of Terrorism and Insurgency Research 1 (2): 21–41. https://doi.org/10.31920/2732-5008/2020/v1n2a2.

- Diop, Boubacar Boris, Patrice Garesio, Mahamat Nour Ibedou, Demba Karyom Kamadji, Eric Kinda, Younous Mahadjir, Issa Ndiaye, et al. 2020. ‘Sommet de Pau: sentiment anti-français ou sentiment anti-Françafrique?’ Mediapart (blog). 12 January 2020. https://blogs.mediapart.fr/les-invites-de-mediapart/blog/120120/sommet-de-pau-sentiment-anti-francais-ou-sentiment-anti-francafrique.

- Erforth, Benedikt, and Denis M. Tull. 2022. ‘The Failure of French Sahel Policy: An Opportunity for European Cooperation?’ Megatrends Afrika (blog). 5 September 2022. https://www.megatrends-afrika.de/en/publication/mta-spotlight-13-the-failure-of-french-sahel-policy.

- Faivre Le Cadre, Anne-Sophie. 2019. ‘Non, L’armée Française n’a pas Livré des Motos à des Jihadistes au Mali’. AFP Factuel, 4 December 2019. https://factuel.afp.com/non-larmee-francaise-na-pas-livre-des-motos-des-jihadistes-au-mali.

- Galan, Julia. 2021. ‘Des Images de Soldats Français au Mali Pillant les Réserves D’or du Pays ? Attention, Intox !’ Les Observateurs - France 24, 11 June 2021. https://observers.france24.com/fr/afrique/20210611-intox-soldats-fran%C3%A7ais-pillage-or-mali.

- Gazeley, Joe. 2022. “The Strong ‘Weak State’: French Statebuilding and Military Rule in Mali.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 16 (3): 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2022.2030627.

- Gegout, Catherine. 2018. Why Europe Intervenes in Africa: Security Prestige and the Legacy of Colonialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goffi, Emmanuel R. 2017. ‘Opération Barkhane : Entre victoires tactiques et échec stratégique’. Rapport de recherche 3. Montreal: Centre FrancoPaix en résolution des conflits et missions de paix. https://dandurand.uqam.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Rapport_Recherche_3_FrancoPaix.pdf.

- Guichaoua, Yvan. 2020. “The Bitter Harvest of French Interventionism in the Sahel.” International Affairs 96 (4): 895–911. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa094.

- Guindo, Sidiki. 2022. ‘Avis de la population sur l’actualité nationale et internationale.’ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KBo7Dc_3pAadPoxLM40I6vJ76RdSJ62b/view.

- Gurcov, Ladd Serwat, and Nichita Héni Nsaibia. 2023. ‘Moving Out of the Shadows: Shifts in Wagner Group Operations Around the World’. ACLED. https://acleddata.com/2023/08/02/moving-out-of-the-shadows-shifts-in-wagner-group-operations-around-the-world/.

- Haidara, Boubacar. 2020. ‘Pourquoi l’opinion publique malienne a une vision négative de l’opération Barkhane’. The Conversation (blog). 10 February 2020. http://theconversation.com/pourquoi-lopinion-publique-malienne-a-une-vision-negative-de-loperation-barkhane-130640.

- Hassan, Hassan. 2019. ‘Sunni Jihad Is Going Local’. The Atlantic (blog). 15 February 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/02/sunni-jihad-turns-away-transnational-terrorism/582745/.

- Human Rights Watch. 2018. ‘“We Used to Be Brothers”’. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/12/07/we-used-be-brothers/self-defense-group-abuses-central-mali.

- Ibrahim, Ibrahim Yahaya, and Mollie Zapata. 2018. ‘Regions at Risk: Preventing Mass Atrocities in Mali’. Early Warning Country Report. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/Mali_Report_English_FINAL_April_2018.pdf.

- International Crisis Group. 2020. ‘Reversing Central Mali’s Descent into Communal Violence’. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/293-enrayer-la-communautarisation-de-la-violence-au-centre-du-mali.

- Kilcullen, David J. 2010. Counterinsurgency. London: Hurst Publishers.

- Leboeuf, Aline, and Hélène Quenot-Suarez. 2014. ‘La Politique Africaine de la France Sous François Hollande : Renouvellement et Impensé stratégique’. Paris: Institut Français des Relations Internationales. https://www.ifri.org/fr/publications/ouvrages-de-lifri/politique-africaine-de-france-francois-hollande-renouvellement.

- Lebovich, Andrew. 2019. ‘Mapping Armed Groups in Mali and the Sahel’. European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/special/sahel_mapping.

- Lecocq, Baz, and Georg Klute. 2013. “Tuareg Separatism in Mali.” International Journal: Canada's Journal of Global Policy Analysis 68 (3): 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702013505431.

- Lijn, Jaïr van der, Noura Abouelnasr, Tofayel Ahmed, Linda Darkwa, Tobias von Gienanth, Fiifi Edu-Afful, John Karlsrud, and Natasja Rupesinghe. 2019. Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission in Mali / MINUSMA. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. https://nupi.brage.unit.no/nupi-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2599513/EPON-report%204-2019.pdf?sequence=7.

- Lopez Lucia, Elisa. 2019. ‘The European Union Integrated and Regionalised Approach towards the Sahel’. Montreal: Centre FrancoPaix en résolution des conflits et missions de paix.

- Mali Demain. 2014. ‘Adresse du Président Modibo Kéïta le 21 janvier 1961 : Evacuation rapide des troupes françaises du Mali’, 18 January 2014. https://www.maliweb.net/armee/adresse-du-president-modibo-keita-le-21-janvier-1961-evacuation-rapide-des-troupes-francaises-du-mali-190241.html.

- Marsh, Nicholas, and Øystein H. Rolandsen. 2021. “Fragmented We Fall: Security Sector Cohesion and the Impact of Foreign Security Force Assistance in Mali.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 15 (5): 614–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2021.1988226.

- Michel, Charles. 2023. Le Chat sur la Dune – Journal de Marche et D’opérations D’un Officier Français au Sahel (2013–2022). Beychac-et-Caillau: Lavauzelle.

- Nsaibia, Héni, and Jules Duhamel. 2021. ‘Sahel 2021: Communal Wars, Broken Ceasefires, and Shifting Frontlines’. ACLED. 17 June 2021. https://acleddata.com/2021/06/17/sahel-2021-communal-wars-broken-ceasefires-and-shifting-frontlines/.

- Pezet, Jacques. 2019. ‘Non, la douane du Mali n’a pas démantelé un trafic d’or effectué par des militaires français sous les ordres de l’Elysée’. Libération, 10 September 2019. https://www.liberation.fr/checknews/2019/09/10/non-la-douane-du-mali-n-a-pas-demantele-un-trafic-d-or-effectue-par-des-militaires-francais-sous-les_1750514/.

- Pérouse de Montclos, Marc-Antoine. 2018. L’Afrique, Nouvelle Frontière du Djihad ? Paris: La Découverte.

- Pérouse de Montclos, Marc-Antoine. 2020. Une Guerre Perdue: La France au Sahel. Paris: JC Lattès.

- Pérouse de Montclos, Marc-Antoine. 2022. “La France au Sahel: Les Raisons D’une défaite.” Juin, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.3917/etu.4294.0019.

- Plank, Friedrich, and Julian Bergmann. 2021. “The European Union as a Security Actor in the Sahel.” European Review of International Studies 8 (3): 382–412. https://doi.org/10.1163/21967415-08030006.

- Powell, Nathaniel K. 2017. “Battling Instability? The Recurring Logic of French Military Interventions in Africa.” African Security 10 (1): 47–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2016.1270141.

- Powell, Nathaniel K. 2022. ‘Why France Failed in Mali’. War on the Rocks (blog). 21 February 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2022/02/why-france-failed-in-mali/.

- Raineri, Luca. 2022. “Explaining the Rise of Jihadism in Africa: The Crucial Case of the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara.” Terrorism and Political Violence 34 (8): 1632–1646. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1828078.

- Sandnes, Marie. 2023. “The Impact of External Support on Coalition Efficiency: The Case of the G5 Sahel Joint Force.” Defence Studies 23 (3): 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2023.2213637.

- Simpson, Emile. 2012. War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First Century Combat as Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, Rupert. 2005. The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World. London: Allen Lane.

- Stoddard, Edward. 2019. “Revolutionary Warfare? Assessing the Character of Competing Factions Within the Boko Haram Insurgency.” African Security 12 (3–4): 300–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2019.1668632.

- Sylla, Mohamed. 2022. ‘Comment la France a échoué au Mali’. L’Aube, 21 February 2022. https://www.maliweb.net/economie/cooperation/comment-la-france-a-echoue-au-mali-2965685.html.

- Thurston, Alex. 2018. ‘Why Do Political Challenges in Mali Persist?’ IPI Global Observatory (blog). 12 December 2018. https://theglobalobservatory.org/2018/12/why-mali-political-challenges-persist/.

- Tull, Denis M. 2019. “Rebuilding Mali’s Army: The Dissonant Relationship Between Mali and Its International Partners.” International Affairs 95 (2): 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz003.

- Tull, Denis M. 2021. “Contester la France: Rumeurs, Intervention et Politique de Vérité au Mali.” Critique Internationale N°90 (1): 151–171. https://doi.org/10.3917/crii.090.0154.

- Vincent, Elise, Cyril Bensimon, and Paul Lorgerie. 2021. ‘Au Mali, L’armée Française en Accusation, un Mois Après la Frappe Contestée de « Barkhane » Près du Village de Bounti’. Le Monde, 11 February 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2021/02/11/au-mali-l-armee-francaise-en-accusation-un-mois-apres-la-frappe-contestee-de-barkhane-sur-le-village-de-bounti_6069527_3212.html.

- Whitehouse, Bruce. 2021. “Mali: Collapse and Instability.” In The Oxford Handbook of the African Sahel, edited by Leonardo A. Villalón, 127–145. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Whiteside, Craig. 2016. “The Islamic State and the Return of Revolutionary Warfare.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 27 (5): 743–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2016.1208287.

- Wing, Susanna D. 2016. “French Intervention in Mali: Strategic Alliances, Long-Term Regional Presence?” Small Wars & Insurgencies 27 (1): 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2016.1123433.

- Zenn, Jacob. 2015. “The Sahel’s Militant “Melting Pot”: Hamadou Kouffa’s Macina Liberation Front (FLM).” Terrorism Monitor 13 (22): 3–6.