ABSTRACT

How can governments gain the trust of their citizens after civil war? Although previous work has thoroughly considered the drivers of governmental trust, we know relatively little about the role of security perceptions in post-conflict settings. Drawing on data from an original survey fielded with 2000 respondents from Liberia, we show that citizens’ security perceptions shape their trust in government. We also demonstrate that explicit attribution of security to specific institutions is key for linking more effective security governance with more trust. Our findings have significant implications for the design of security institutions and statebuilding in post-conflict settings.

Introduction

Under what conditions can a government gain the trust of its citizens after conflict? The question of what leads citizens to accept a government’s right to rule – i.e. consider it trustworthy and legitimate (Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Citation2009; Risse and Stollenwerk Citation2018) – is central to the study of governance in areas of limited statehood. Although previous work has emphasized general public goods provision, free and fair elections, and just institutions as key to government trust, we know comparatively little about the relationship between security and trust. This omission is particularly problematic given the importance of trust in government to statebuilding in post-conflict settings that can be unsafe for large segments of the population (Goldstone Citation2008). Our research addresses this gap by investigating how perceptions of security affect trust in government.

We argue that security perceptions are a critical source of governmental trust for post-conflict societies. This study suggests that a secure environment is an indispensable part of a healthy social contract between a government and its citizens, especially in areas of limited statehood. As such, security is an essential component of effective governance and a key output or performance by which citizens assess whether they can trust their government (Call and Wyeth Citation2008; Rotberg Citation2004). However, we show that citizens’ subjective evaluation of their country’s security situation rather than any given objective metric of security determines this judgment.

We test our argument using an original, nationwide survey of 2000 residents of Liberia covering all 15 counties, with urban and rural respondents. Liberia is a weakly institutionalized post-conflict setting where areas of limited statehood with competing governance authorities abound, presenting a challenging case for our argument. Nonetheless, we uncover a substantive and statistically significant positive relationship between perceptions of national security government trust at both the community and higher levels of governance. Individual perceptions of security are positively associated with governmental trust, though only for individuals who explicitly attribute their personal security to government actors. This relationship holds even when we account for other likely sources of trust.

The challenge for governments ruling states with limited capacities is that they must gain the trust of their citizens in order to generate the compliance and cooperation of the population so that they can govern effectively, often during or after conflict. However, by definition, weak central state institutions lack the administrative capacity to make and implement rules and/or have only incomplete monopoly of force (Risse Citation2011). Although exhaustion from war and fear of its resurgence may be a powerful motivator for compliance, states with weak capacities generally lack other mechanisms such as coercion to achieve policy objectives and governance outcomes. In any case, coercion is much more costly and resource-intensive for achieving compliance and cooperation than gaining the population’s trust (Levi and Sacks Citation2009; Tyler Citation1990). Therefore, trust provides a key tool for governments of states containing significant areas of limited statehood to induce lasting peaceful cooperation and ensure effective governance.

Our analysis offers a theoretical and empirical roadmap for understanding the role of security perceptions in establishing governmental trust. Our framework applies output-based theories of legitimacy to understand the drivers of government trust. Such theories argue that effective governance results in higher legitimacy for governance actors, particularly for the state (Fisk and Cherney Citation2017; Scharpf Citation1999). We apply this logic to settings where effective governance means security: if the state makes citizens feel secure, citizens reward the government with more trust. Security may be particularly important where large parts of the population have suffered from insecurity or violence, as is the case in many areas of limited statehood. Moreover, trust can set in motion a virtuous circle of governance in areas of limited statehood. In such a circle, effective and trustworthy governance become mutually reinforcing, ensuring stable and effective governance (Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018). According to this argument, effective governance helps to build trust in government, and increased trust allows governments to provide more effective governance such as greater security.

This article contributes to scholarship on institutional design in post-conflict settings and areas of limited statehood. We show that citizens’ perceptions of their country as safe and secure is a critical and foundational first step for governmental trust even in the most challenging of circumstances. Our analysis suggests that security perceptions matter more than the mere absence of violent events for gaining the trust of a populace. This finding complements existing arguments that emphasize the importance of the design of electoral institutions, power-sharing agreements, and elite pacts for governance in post-conflict settings (Durant and Weintraub Citation2014; Matanock Citation2017; Matanock and Garbiras-Díaz Citation2018; Nomikos Citation2021). In line with more recent work (Arriola et al. Citation2021; De Bruin Citation2020), we demonstrate that variation in the institutional design of state security institutions in particular can have important consequences for the stability of fragile settings.

Furthermore, we contribute to the burgeoning literature on micro-level processes of development and statebuilding (Blair Citation2019; Blair, Karim, and Morse Citation2019; Fearon, Humphreys, and Weinstein Citation2015). We take seriously the need to disentangle the micro-level dynamics of governance from more general, macro-level processes of conflict. We show that effective security governance does not have the same relevance for gaining the trust of all citizens in the same way. This points to the relevance of considering the conditions under which trust in governance develops for different kinds of citizens.

Building trust in government after conflict

Distinguishing governmental trust from legitimacy

This article rests on output-based theories of legitimacy, which hold that the state derives legitimacy from its ability to provide public goods and services, security being one such good (Fisk and Cherney Citation2017; Scharpf Citation1999; Stollenwerk Citation2018). Output-based theories of legitimacy have been prominent in the social sciences for decades, but much of this work focuses on Western consolidated statehood (Dahrendorf Citation1980; Lipset Citation1959; Rothschild Citation1977). Empirical studies on the sources of legitimacy in areas of limited statehood remain rare and have presented mixed findings; some find support for the central claims of output-based theories of legitimacy (e.g. Gilley Citation2009; Levi and Sacks Citation2009), others find only mixed support (e.g. Fisk and Cherney Citation2017; Mazepus Citation2017). Hence, the extent to which states in areas of limited statehood derive legitimacy from public goods provision, as these theories would predict, is unclear.

We apply the logic of output-based theories of legitimacy to the related concept of governmental trust. We understand legitimacy to obtain when ‘the features of authoritative institutions, or the choices of individuals in authority, enhance the intrinsic motivations of citizens to carry out certain social duties’ (Dickson, Gordon, and Huber Citation2022, 1, emphasis added). This definition excludes extrinsic motivations of citizens to follow the edicts of government driven by the material capabilities and behaviour of governments. Given that the focus of this study is explicitly on security provision, a material factor shaping intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, we examine governmental trust rather than legitimacy.

Drawing on the seminal work by Dickson, Gordon, and Huber (Citation2022), we assume that citizens trust their government when the behaviour of the government enhances the intrinsic or extrinsic motivations of citizens to carry out their social duties. Trust thereby provides governance actors with a ‘reservoir of cooperation’ (Risse and Stollenwerk Citation2018) upon which they can draw even in the absence of statehood. Government trust leads to less costly compliance and cooperation than coercive forms of social coordination (Levi Citation1988; Tyler Citation1990). Moreover, if citizens view a state as trustworthy, they will continue to cooperate and comply with the state’s rule even if they do not agree with every decision and every policy. As long as governmental behaviour remains within the boundaries of what its citizens consider acceptable, they will continue to cooperate. Of course, repeated long-term abuse of the trust populations bestow upon a government by state institutions themselves and failure to meet citizens’ governance expectations will erode governmental trust.

Security perceptions as a source of governmental trust

Effective governance entails providing security to a population. We consider governance to be the various institutionalized modes of social coordination to make and implement collectively binding rules and/or to provide collective goods (Risse Citation2011). With respect to security, relevant actors include the police and army for providing the collective good. Citizens’ perceptions of governance are an essential part of its effectiveness (Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi Citation2009; Stollenwerk Citation2018). Therefore, we consider security governance as effective if citizens perceive it as such (i.e. feel secure). If citizens feel secure, they might be more inclined to trust their governments. In other words, if citizens are satisfied with the security provision output of the government, they are more likely to consider it trustworthy. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1: Individual perceptions of security are positively associated with governmental trust.

Moreover, we posit that when civilians feel more secure, they trust their government more if they explicitly attribute their security to formal government institutions. Stollenwerk (Citation2018) has tested this argument in Afghanistan, finding that this type of explicit attribution is a key condition to link improved security perceptions with higher trust of governance actors. In his study, Afghans who felt more secure and explicitly attributed this security to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) were also more likely to view ISAF as trustworthy (McLoughlin Citation2015).

Two possible effects could be occurring simultaneously. On one hand, it might be that individuals who attribute security to the state become disenchanted when they do not feel safe, expressing less trust in government actors. On the other hand, it could also be that individuals who do not attribute security to the state continue to hold the government in high esteem even when they do not feel safe because they expect comparatively little from their government. We test for the conditional aspects of our argument by considering two additional hypotheses:

H2a: Among individuals who explicitly attribute their security to state institutions, those who feel safe are more likely than those who do not to express trust in their government.

H2b: Among individuals who do not explicitly attribute their security to state institutions, those who feel safe are not more likely than those who do not to express trust in their government.

Context: Governmental trust in post-conflict Liberia

The Liberian government has struggled to provide security and to gain the trust of the population in the areas of limited statehood that pervade the country. Hence, we consider Liberia to be a useful test case for our arguments that also indicates their relevance for areas of limited statehood more broadly. If we find that security provision is a source of governmental trust in Liberia, then this is an indication that our arguments may apply to areas of limited statehood more generally. Specifically, we chose Liberia for five reasons.

First, state institutions cannot be seen as a source of security by default. Liberia experienced two civil wars between 1989 and 2003 producing an environment where Liberians often reported feeling unsafe long after the fighting had officially ended (de Carvalho and Nagelhus Schia Citation2011). Although the security situation has improved after the end of the civil wars, Liberians are frequently exposed to crime and violence. Moreover, state institutions like the police or the army continue to be underfunded and ill-equipped to tackle violence and crime effectively (Blair, Blattman, and Hartman Citation2017; Bøås and Stig Citation2010).

Second, the Liberian state has for long suffered from a trust deficit. The conflicts of the past three decades reflect the existence of severe fractures between the state and its citizens (Hegre, Østby, and Raleigh Citation2009). State actors and institutions were involved in large scale fighting activities during the wars, which has caused significant mistrust and skepticism towards the state. As in other fragile settings (Grossman, Nomikos, and Siddiqui Citation2023), conflict between various governance actors, state and non-state alike, likewise has generated mistrust. This mistrust is so severe that in the beginning stages of the Ebola epidemic, many Liberians refused to comply with public health protocols because they believed that the disease was a fabrication of the government, designed to collect more foreign aid (Blair, Morse, and Tsai Citation2017; Tsai, Morse, and Blair Citation2020). At the community level, Liberian citizens report that they perceive traditional leaders as more powerful and trustworthy than local government (Blair, Blattman, and Hartman Citation2017). If and how the Liberian state can (re-)build trust in the eyes of its citizens may depend to a large extent on the security Liberians experience.

Third, non-state actors play an important role in Liberian governance, especially in the security sector (Bøås and Stig Citation2010). Traditional chiefs and secret societies are historically considered the primary source of local security, and past research shows this undermines the effectiveness of the Liberian state in security provision in measurable ways (Blair, Karim, and Morse Citation2019; Fearon, Humphreys, and Weinstein Citation2015). Liberia has not, like some African states, worked in tandem with traditional leaders to target public goods provision to local communities, which might lessen the perceived divide between traditional leaders and the state (Baldwin Citation2015; Mustasilta Citation2021). In addition, many former combatants formed extralegal groups that maintained order and stability in Liberia after the end of the civil wars (Cheng Citation2018). These non-state actors all provide security to Liberian communities, often in conflict with each other or the state (Blair, Karim, and Morse Citation2019).

Fourth, external actors are key in the Liberian security sector. The United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) was the longest multidimensional peacekeeping operation in the UN’s history. At the time of the research in 2018, UNMIL was underway and had been since 2003 (UNMIL ended on 30 March 2018). While its mission was to aid the Liberian government in regaining its people’s trust and to establish an enduringly peaceful environment, its presence may have effectively diverted credit for security (Bargués-Pedreny and Martin de Almagro Citation2020; Blair Citation2019; Mvukiyehe Citation2017). Therefore, since it is not clear whether citizens attribute improvements in governance to the state or to external and non-state actors, security perceptions are unlikely to be a straightforward source of governmental trust.

Fifth, areas of limited statehood pervade Liberian territory even 17 years after the civil war officially ended (Bøås Citation2001; Cheng Citation2018; Clapham Citation1998; Reisinger Citation2009). Liberians in these areas may have no or little contact to the state, and thus they might be less likely to perceive the state as a security provider and consequentially afford it little of their trust. Limited state capacity and little state reach may deteriorate citizens’ trust in their governments.

Finally, it worth mentioning that explicit attribution may be lacking in our test case for two reasons. First, the state frequently displays predatory behaviour towards its own citizens in areas of limited statehood and in Sub-Saharan Africa in particular (Baker Citation2010, Citation2015; Reno Citation2015). Under such circumstances, citizens may attribute insecurity to the state resulting in a decline of governmental trust. Second, traditional leaders and UN troops are often relevant governors. Citizens may attribute their physical security to these non-state or external actors, but not to the state. This underlines the need to analyse the extent to which explicit attribution of (in-)security matters for the governmental trust.

Research design

Data

We test our hypotheses with an analysis of data from an original SMS survey fielded with 2000 respondents in March 2018 using random digit dialling (RDD). We collaborated with the survey firm Orange Door Research, which used a large sample of Liberian phone numbers to conduct the surveys. The survey is nationally representative for Liberians 18 years and older owning a mobile phone. About 75 per cent of the population has access to mobile phones in Liberia. We randomly sampled respondents from GeoPoll’s subscriber database according to the geographic specification we provided to obtain representation from all 15 counties. We use county-specific questions in the survey itself to validate the location of each respondent. The survey was opt-in, meaning respondents needed to explicitly give consent to start it. Upon successful completion of the survey, each respondent received the local equivalent of $0.50 in airtime top-up credit as an incentive.

Using mobile phone surveys potentially introduces biases in the data that need to be kept in mind. Although mobile phone use in Liberia is common and widespread the sampled population is likely to reflect some specific socio-economic features. Our use of SMS services to conduct the survey implies respondents are likely to be literate and need to possess sufficient economic resources in order to own a mobile phone. Moreover, given the content of the survey, respondents may skew towards those with more education and greater interest in political issues. However, we still chose the phone survey to answer our research question because it allowed us to reach areas of Liberia that might have been impossible to cover through face-to-face surveys. Additionally, in-person interviews would have been more visible and easier to track, potentially endangering survey participants if they were candid about their views on sensitive issues like security and governmental trust.

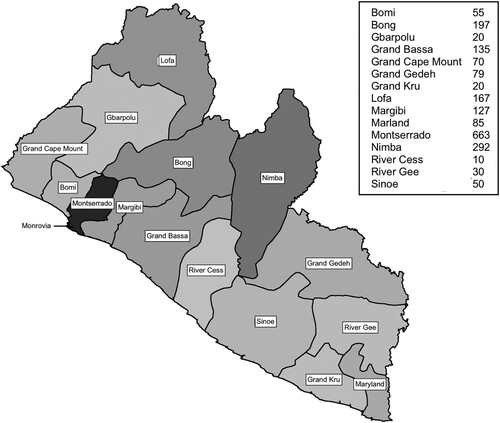

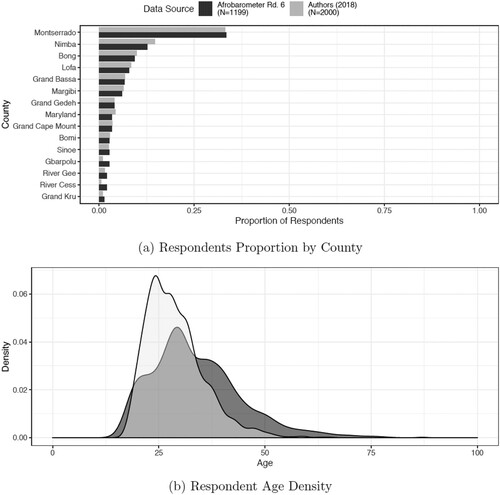

displays the distribution of our respondents across Liberia. As the figure shows, our sample is geographically diverse. Although 663 out of 2000 respondents (33.15 per cent) are from Monrovia or the surrounding county, Montserrado, the vast majority of our respondents are from counties far from the capital. A comparison of our sample to Round 6 of the Afrobarometer, which is ‘a representative cross-section of all citizens of voting age in a given country’ (Afrobarameter Citation2019) and is generally considered the gold standard for large scale survey data in Sub-Saharan Africa, underlines the representativeness and quality of our data. Round 6 of the Afrobarometer was conducted in 2015 in Liberia and generated 1199 respondents. In (a), we compare the proportion of respondents sampled in each county by the Afrobarometer and by our procedure. There is no substantively or statistically significant difference in sampling proportion in any of the 15 counties between the two sets of data.

reports summary statistics from the survey. The average age of each respondents is almost 29 years old and 59 per cent of our respondents were male. As (b) shows, our sample skews a little younger than the Afrobarometer, though the substantive differences in density are minor – both studies primarily survey individuals aged 20 to 40. Although we do not anticipate that these differences in the makeup of our sample would systematically bias our findings, we do adjust for age and gender in our empirical models since research has shown that these are the most salient demographic cleavages in Liberian society (Fearon, Humphreys, and Weinstein Citation2015).

Table 1. Summary statistics from survey.

Statistical modelling

In order to include individual as well as county-level covariates, we employ multilevel models in our regression. Multilevel models adjust for relevant covariates at both the micro- and macro-level. Since we expect county-level variables as well as individual-level variables to be associated with the degree of governmental trust, we take these variables into account to minimize omitted variable bias (Wenzelburger, Jäckle, and König Citation2014). Multilevel modelling makes more robust inferences than standard regression techniques when taking macro- and micro-level variables into account simultaneously (Hox Citation2010; Snijders and Bosker Citation2012; Steenbergen and Jones Citation2002). Whereas standard regression techniques assume that units of analysis are independent and identically distributed, multilevel models allow us to identify a second-order unit (e.g. a county) according to which individual units cluster and share certain characteristics. We relied on random intercept models in our analysis as they are stable and reliable given the low number of second level units. Such models assume that the second-level units (i.e. counties) start from different intercept values but that explanatory variables have the same coefficient magnitude across counties (Hox Citation2010).

Dependent variables

Our dependent variables are measured by two questions that asked respondents to say how much trust they have in their government at different levels (county-level and community-level). We asked respondents ‘How much trust do you have in government at the county level?’ and ‘How much trust do you have in government at the community level?’. We avoided asking specifically about national-level institutions because we did not want to generate responses to our questions that were specifically tied to a governmental authority that respondents might have opinions about but little contact with. We felt that these would affect responses through a different channel than what we theorize. Furthermore, we use the term ‘government’ instead of ‘state institutions’ or related terms after the pre-test and discussions about the questionnaire and the right wording with Liberians and local partners. From these questions, we created a binary indicator for whether respondents said they had much/very much trust (1) or no/little trust (0) in the corresponding state authority. About half said they had much or very much trust in either their county or community government.

While our study focuses on trust in government, we note here that it may capture some elements of state legitimacy as well. Empirically ‘government’ is a common synonym for state institutions understood by Liberians. More generally, while legitimacy is notoriously difficult to measure (Blair Citation2018; Gilley Citation2009; Risse and Stollenwerk Citation2018; Weatherford Citation1992), questions about trust in state institutions provide useful proxy measures of state legitimacy (Gilley Citation2009; von Haldenwang Citation2016). However, we caution against extrapolating from our findings about government trust to state legitimacy. Whereas individual perceptions of state legitimacy are conceptually best thought of as being intrinsically motivated, trust may be affected by material concerns, and hence can also be extrinsically motivated (Dickson, Gordon, and Huber Citation2022; Gordon and Huber Citation2019).

Independent variables

We generate two key independent variables to operationalize perception of security provision using our survey data. First, we create the binary variable Liberia security using answers to a question about the security situation in Liberia as a whole. We grouped together respondents who said ‘Very Bad’ (coded as 0) and respondents who answered ‘Bad’, ‘Good’, or ‘Very Good’ (coded as 1). This measure captures the respondents’ security perception at the country level. Second, we created the binary Security perception using answers to a question about whether respondents say that they or their family members have felt unsafe in their neighbourhood in the past 12 months. We grouped together respondents who said that they have felt unsafe ‘Many times’ (coded as 0) and respondents who answered ‘Never’, ‘Once or twice’, or ‘Several Times’ (coded as 1). This measure captures the respondents’ security perception at a personal level. Finally, we also use a binary indicator, Informal attribution, to measure whether respondents attribute security to a state institution (either the police or the military) or to informal non-state sources of conflict resolution. Through this we are able to assess whether citizens explicitly attribute their (in-)security to the state (H2a and H2b).

Control variables

In our multilevel models, we account for factors that scholars suggest may shape perceptions of government trust and, along the way, perceptions of security as well. We adjust for the number of UN peacekeeping personnel deployed, on average, in the county over the course of UNMIL’s deployment (Hunnicutt and Nomikos Citation2020). To control for de facto security, we create a variable, physically attacked, that captures whether respondents say that they or anyone in their family have been exposed to violence in the past 12 months. We also include a county-level variable that captures recent violent incidents using the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) dataset (Raleigh et al. Citation2010). Finally, the models control for age and gender in order to adjust for the distribution of our sample and to minimize confounding due to respondents’ demographic characteristics.

Results

Main results: Security perceptions and governmental trust

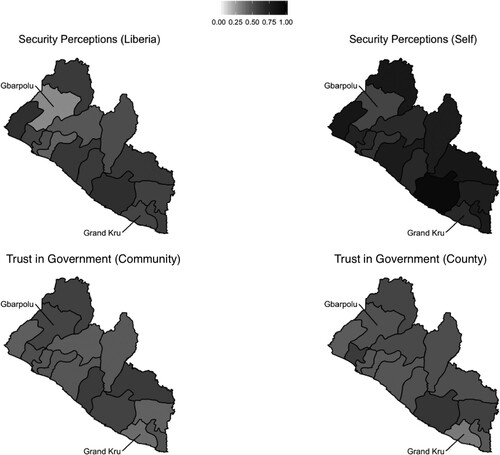

Our study investigates whether individual perceptions of security are associated with governmental trust. To assess this, we look at the relationship between trust in government community- and county-level state institutions in Liberia, our two dependent variables, and perceptions of national security and individual security, our primary independent variables. The map in the upper left panel of shows the proportion of Liberians by county evaluating the security situation in the country in general as positive, i.e. security governance as effective. The upper right panel shows the proportion of Liberians by county evaluating the security situation in their neighbourhood as positive, i.e. security governance as effective. The map in the lower left panel shows the proportion of people who say they trust their community government. The final map in the lower right panel displays the proportion of people who say they trust their county government. For all maps, darker colours signal higher security/higher government trust. As the maps in demonstrate, the relationship between perceptions of security and governmental trust is far from clear in Liberia.

For example, though a large proportion of citizens (0.95) in Grand Kru county in southern Liberia perceive their personal security positively, the proportion of citizens who view county- or community-level governmental institutions as trustworthy in the same county is quite low, 0.35 and 0.40 respectively.Footnote1 In counties like Gbarpolu in northwest Liberia, though relatively fewer respondents view the national security situation positively (0.70), most perceive county- or community-level institutions as trustworthy, 0.50 and 0.55 respectively. These examples stress that the association between perceptions of effective security governance and governmental trust is not straightforward, necessitating a micro-level investigation of how the two factors relate.

reports the results of our regressions of government trust at the county-level (Models 1 and 2) and community-level (Models 3 and 4) on perception of Liberian security. Models 1 and 3 include all of our set of individual-level and county-level variable controls. In Models 2 and 4, we include the binary indicator for whether respondents attribute security to informal non-state conflict resolution institutions as well as the interaction between this indicator and perception of Liberian security. In , we report the results from the same regression models (numbered 5–8) except with perception of individual security as the main predictor rather than perception of national security.

Table 2. Multilevel model logit regression results, perception of Liberian security.

Table 3. Multilevel model logit regression results, perception of individual security.

We find robust empirical support for Hypothesis 1 at both the county and community-level when we measure security perceptions at the national-level (models in ) but not at the individual level (models in ). The positive and statistically significant coefficients associated with Liberian security in Models 1–4 suggest that respondents who felt the country was more safe and secure were also more likely to express trust in the government. Although we hesitate to derive a strong causal interpretation given the cross-sectional nature of the data, these results imply that citizens’ assessment of the national security situation is quite relevant for their views of the governments. Citizens satisfied with the national security situation are twice as likely as those who are dissatisfied to say they trust their government. At the same time, counter to our own expectations, we do not observe a statistically significant relationship between individual security perceptions and trust in government. We analyse these null results further in the discussion section below.

Conditional results: Attribution of security as moderator

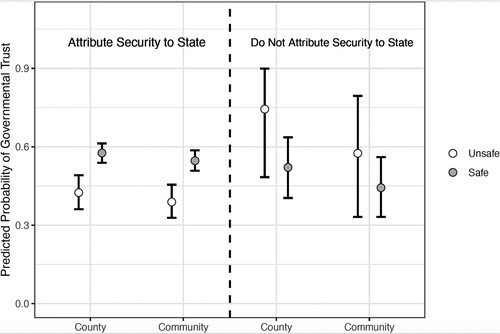

Next, we examine Hypothesis 2a and 2b, which considered the association between security perceptions and trust in government moderated by the degree to which respondents attribute their security explicitly to governmental actors. For ease of interpretation, we use the estimates from Models 2 and 4 of to derive the predicted probability that an individual express trust in government conditional on whether they attribute security to government actors or not. We graph the results in . The left side of the figure graphs the predicted probability individuals say they trust government at the county and community level separated by whether they consider Liberia safe (grey-shaded circles) or unsafe (white-shaded circles).

Figure 4. Predicted probability of trust in government as function of perception of security and security attribution, county and community government.

The analysis graphed in provides strong evidence in favour of Hypothesis 2a. Individuals who attribute security to the state and feel safe are more probable than not to say they trust their government: 56.5 per cent predicted probability for county government and 53.5 per cent for community government. Those percentages decrease by a statistically and substantially significant amount for individuals who attribute security to the state and do not feel safe to 41.1 and 37.4 per cent for county and community governments respectively. In line with the prediction of Hypothesis 2a, this drop suggests that there exists a positive relationship between security perception and trust in government among individuals who attribute security to state institutions.

also offers evidence in favour of Hypothesis 2b, which stated that there would not be a relationship between security perceptions and governmental trust for individuals who do not attribute security to state institutions. We find a high probability that individuals who do not attribute security to the state and feel safe express trust in government: 50.6 per cent predicted probability for county government and 42.6 per cent for community government. However, we do not find that these percentages decrease by a statistically significant amount for those individuals who do not attribute security to the state and feel unsafe. If anything, we find a higher probability for individuals who do not attribute security to the state and feel unsafe express trust in government. Although we hesitate to interpret these findings given their lack of precision, these probabilities offer some additional evidence that security perceptions do not drive governmental trust for individuals who do not attribute security to the state.

Robustness checks

We conduct three additional checks to ensure the robustness of our empirical findings, which we report in full in the Online Appendix. Public goods provision is a plausible confounder since the government is better able to provide goods in areas that are more stable and where residents feel more secure. We find no evidence that the omission of other types of public goods provision from our empirical analysis might have biased our main results. An additional concern may be that we have not properly accounted for the role of foreign aid specifically (Haass Citation2021; Weintraub Citation2016). Yet the magnitude, direction, and precision of the main coefficients remained robust to the inclusion of measures of foreign aid, regardless of model specification. Lastly, it might be that our results are a function of the way in which we coded our dependent variables. However, our results are robust to a conservative recoding of the dependent variables, the use of a probit model, or the use of an ordered logit model if we chose to retain the ordinal nature of the dependent variables. While we hesitate to interpret these results further, they do make us more confident in the robustness of the associations presented in the main analysis.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that when Liberians perceive of their country as safe, they are also more likely to perceive the Liberian government as trustworthy at both the county and community levels. In this section, we delve into these findings in greater detail. We begin by considering a set of alternative explanations for our findings before discussing the possibility of reverse causality. We conclude by returning to the relationship between individual perceptions of security and governmental trust.

Alternative explanations

Security provision is not the only source of governmental trust and alternative explanations for perceiving the government as trustworthy are relevant. To what extent do security perceptions drive governmental trust compared to other sources of trust? To answer this question, we examine four potential alternative explanations. First, we measure whether citizens perceive elections as free and fair, a prominent source of governmental trust according to scholars of democratic governance and legitimacy. We generated the variable Free and fair elections from our survey to capture the extent to which Liberians perceive elections as free and fair. Second, we measure whether citizens believe that their tribal group is treated fairly. We include a procedural justice variable reflecting whether respondents say that their tribal group is being treated fairly in Liberia. Third, since corruption affects government trust negatively because citizens expect the state and its institutions to function in an uncorrupt, fair, and objective way, we examine the degree to which respondents perceived the government as corrupt. We include corruption as an indicator for how corrupt respondents believe Liberian state institutions to be. Finally, we also include a variable called state contact that indicates citizens’ contact with state institutions since citizens with more frequent contact with the government through state institutions might be more likely to trust the government.

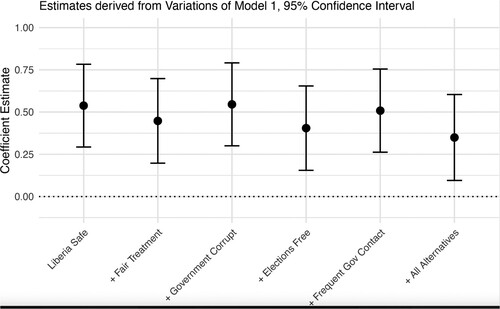

In order to empirically investigate whether these alternatives are driving governmental trust rather than perceptions of Liberian safety, we rerun Model 1 from and add the variables representing each alternative explanations to see whether any of them change the estimated relationship between security perceptions and governmental trust. graphs the coefficient estimate for security perceptions as measured by perception of Liberia as safe in six different variations of the regression in Model 1. The baseline model (‘Liberia safe’) graphs the estimate without any additional explanatory variables. We then add the variables for each explanation and, lastly, all of them in the same model. The figure shows that the estimate for security perceptions remains relatively unchanged and statistically significant even when adjusting for alternative explanations. Put otherwise, while each of these explanations likely contributes to governmental trust in their own right, they cannot account for the entirety of the association between security perceptions and governmental trust.

Reverse causality

A related concern is that of reverse causality. Specifically, it might be the case that governmental trust creates perceptions of security among Liberians rather than the other way around. For example, from the government's perspective, it might be the case that in areas where citizens’ predisposition to comply with the government is higher because of higher trust, governments invest more in providing public goods such as security (Aldama Citation2022). Alternatively, from the individual perspective, it might simply be the case that people predisposed to believe their government is more trustworthy also believe that their country is more secure.

Although our research design cannot definitively rule out the possibility of reverse causality, there are several reasons that we do not believe that this substantially impacts our conclusions. To begin with, as shown in and , we do not find a relationship between perceptions trust in government and de facto security. This suggests that it is not the case that in areas where the Liberian government is more trustworthy it invests more heavily in security provision.

It is also unlikely that reverse causality explains our findings from an individual perspective. If our findings are due primarily to the fact that individuals that are predisposed to believe that their government is more trustworthy also believe that their country is more secure, we should not observe a moderating effect of attributing security to the government. Indeed, if individual perceptions of government trust cause perceptions of security, they should so independently of attribution of security provision.

Reconsidering perception of security to self

Our theory predicts a relationship between perceptions of security and trust in government. The theoretical intuition is that bolstering national security or individual security would offer a way for the government to prove its ability to provide a service (security) for its people. We initially had expected that perceptions of national security and perceptions of self-security would both measure generalized security perception. As a result, we expected a positive relationship between both measures and governmental trust: citizens who feel safe should trust the government more.

However, our empirical analysis shows no statistically significant relationship between perceptions of self-security and trust in government. Although this result runs counter to our initial expectations, we believe that this difference is explained by the fact that Liberians do not think of their feelings of general safety as related to governance. Returning to our theory, the intuition is that citizens do not view their personal safety as a service provided to them by the government in the same way as national security.

Our empirical analysis of the predictors of government trust as a function of perception of self-security, which we summarize in , suggests two patterns consistent with this interpretation of the lack of a relationship. First, we do not find any relationship between security attribution, self-security perceptions, and governmental trust. In other words, individuals who feel unsafe and attribute security to the government do not trust the government less than those who feel unsafe and do not attribute security to the government. Second, across all models, we find a strong relationship between individuals who have not experienced attacks in the past year (the ‘Lack of attack’ variable) and governmental trust when adjusting for security perceptions. Put otherwise, individuals who feel unsafe – their security perception – but have not experienced violence in the past year still say they that they trust their government. That is, it is possible for a government to retain the trust of individuals who feel unsafe, as long as it can protect them from being individually targeted.

Conclusion

Our study examined the sources of governmental trust in areas of limited statehood after a recent conflict. We derived a set of hypotheses for an in-depth test of Liberia as a country displaying multiple areas of limited statehood. We analysed data from an original survey of 2000 respondents fielded in all 15 counties of Liberia and present the results of a series of multilevel models.

We find that citizens’ security perceptions are a highly relevant source of governmental trust in areas of limited statehood. We find strong evidence in favour of our main hypothesis that perceptions of security are positively associated with governmental trust, but only when we measure security perceptions in terms of national security. We also find support for our secondary hypothesis that perception of security as a source of governmental trust is conditional on explicit attribution of that security to a state actor. This underlines the findings for our main hypotheses and stresses the importance of explicit attribution to link more effective governance with more trust. The link between effective governance and increased governmental trust does not work automatically and often requires that citizens explicitly attribute effective governance to the state.

However, we do not argue that perceptions of security are the only source for governmental trust. Rather, we hold that we need to incorporate citizens’ subjective security perceptions into our understanding of the different sources of trust. Still, citizens expect more from the state than mere effectiveness. A single source of governmental trust is unlikely to succeed in explaining and establishing lasting relationships between a government and its citizens.

Our findings have important implications for policymakers concerned with establishing trustworthy governance institutions in areas of limited statehood. External actors trying to strengthen governmental trust in areas of limited statehood should dedicate resources to making citizens feel like their country is safe and secure. This also implies that external actors should refrain from strengthening state institutions that use predatory means against their own citizens and are a source of insecurity themselves. Additionally, policymakers ought to tailor interventions to the level of governance.

Given the limitations of our research, we suggest three areas of further exploration. First, this study offers valuable insight on the extent to which security perceptions shape governmental trust for domestic state institutions on different levels. However, such studies should extend beyond the domestic government. In particular, existing scholarship has considered the relationship between public goods provision and perceptions of traditional actors (Baldwin Citation2015; Brierley and Ofosu Citation2023) and international actors (Bush and Prather Citation2022; Nomikos Citation2022)? Does this relationship extend to security perceptions? Knowing how not only state institutions, but also international actors and local non-state actors can gain the trust of local populations would not only be of great analytical value, but also of tremendous political relevance as it would help policy-makers to ensure the trustworthiness of various governance actors and thereby long lasting and peaceful cooperation between governors and governed.

Second, we build our results on original cross-sectional survey data. Still, future studies ought to aim for long-term panel data that helps to capture changes in the relevant variables over time to increase causal inference. As we rely on cross-sectional data, we refrain from making any strong causal claims, but rather read our findings in correlational terms. Through long-term panel data it will be possible to further substantiate our findings and to clarify the causal arguments that build the backbone of output-based theories of legitimacy included in this study. Our findings indicate a possible virtuous circle of governance between effective and trustworthy governance. As effective governance seems to be a strong source of governmental trust, increased trust may in turn also allow for more effective governance creating such a virtuous circle (see also Levi and Sacks Citation2009; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018). However, to test this assumption and to tackle the problem of reversed causality, additional data are necessary.

Third, we used Liberia as a first test case for our theoretical arguments. Hence, we suggest carrying out comparable studies in further empirical environments. These may focus on Sub-Saharan Africa, but areas of limited statehood in Latin America or Southeast Asia would also offer fruitful possibilities for comparison. This would help determine whether our findings apply to areas of limited statehood more broadly or whether they are region or even country-specific.

nomikos_stollenwerk_appendix_jisb.pdf

Download PDF (230.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Aila Matanock and Michael Weintraub for comments on the paper and to the team at Orange Door Research, especially Michael Kleinman and Nicholai Lidow, for their assistance in fielding the survey. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2019 meetings of the International Studies Association, the 2019 meetings of the American Political Science Association, and the meeting of the Folke Bernadotte Academy research working group in Monrovia, Liberia in November 2018.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in an OSF repository at https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/hd28z

and in the supplementary materials of the article.Additional information

Notes on contributors

William G. Nomikos

William G. Nomikos is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara where he serves as director of the Data-driven Analysis of Peace Project and is a member of the 2035 Initiative. His work examines how identity and domestic politics shape international intervention using a mix of computational, experimental, econometric, and field methods. His first book, Local Peace, International Builders: How the UN Builds Peace from the Bottom Up (Cambridge University Press 2024), examines the conditions under which international actors successfully bring order, peace, and stability to fragile settings. He is currently conducting research related to the politics of statebuilding, climate change and conflict, and intergroup trust in fragile settings.

Eric Stollenwerk

Eric Stollenwerk is a research fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg, Germany. He previously conducted his research at the Freie Universität Berlin, Stanford University, and the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). His work lies at the intersection of international relations, comparative politics, and peace and conflict studies. He has published his work in journals including the Annual Review of Political Science, Democratization, the Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Terrorism and Political Violence, and Daedalus. His book, Effective and Legitimate Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood, was published by Oxford University Press in 2022.

Notes

1 See for full county names. See also Sabrina Karim’s work (Karim Citation2017; Citation2020) in this area for in-depth exploration of the mechanisms of security-sector reform.

References

- Afrobarameter. 2019. “Sampling Principles and Weighting.” https://www.afrobarometer.org/surveys-and-methods/sampling-principles.

- Aldama, A. 2022. “A Theory of Social Programs, Legitimacy, and Citizen Cooperation with the State.” Journal of Peace Research 59 (4): 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433211042792.

- Arriola, Leonardo R., David A. Dow, Aila M. Matanock, and Michaela Mattes. 2021. “Policing Institutions and Post-Conflict Peace.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 65 (10): 1738–1763. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027211013088.

- Baker, Bruce. 2010. “Linking State and Non-State Security and Justice.” Development Policy Review 28 (5): 597–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00500.x.

- Baker, Bruce. 2015. “Unchanging Public Order Policing in Changing Times in East Africa.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 53 (3): 365–389. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X15000567.

- Baldwin, Kate. 2015. The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bargués-Pedreny, Pol, and Maria Martin de Almagro. 2020. “Prevention from Afar: Gendering Resilience and Sustaining Hope in Post-UNMIL Liberia.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14 (3): 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2019.1663987.

- Blair, Robert A. 2018. Legitimacy after Violence: Evidence from Two Lab-in-the-Field Experiments in Liberia. SSRN. Accessed November 20, 2019. https://ssrn.com/abstract = 2326671.

- Blair, Robert A. 2019. “International Intervention and the Rule of Law after Civil War: Evidence from Liberia.” International Organization 73 (2): 365–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818319000031.

- Blair, Robert A., Christopher Blattman, and Alexandra Hartman. 2017. “Predicting Local Violence: Evidence from a Panel Survey in Liberia.” Journal of Peace Research 54 (2): 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316684009.

- Blair, Robert A., Sabrina M. Karim, and Benjamin S. Morse. 2019. “Establishing the Rule of Law in Weak and War-Torn States: Evidence from a Field Experiment with the Liberian National Police.” American Political Science Review 113 (3): 641–657. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000121.

- Blair, Robert A., Benjamin S. Morse, and Lily L. Tsai. 2017. “Public Health and Public Trust: Survey Evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic in Liberia.” Social Science & Medicine 172 (1–2): 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016.

- Bøås, Morten. 2001. “Liberia and Sierra Leone – Dead Ringers? The Logic of Neopatrimonial Rule.” Third World Quarterly 22 (5): 697–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590120084566.

- Bøås, Morten, and Karianne Stig. 2010. “Security Sector Reform in Liberia: An Uneven Partnership Without Local Ownership.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 4 (3): 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2010.498934.

- Brierley, Sarah, and George Kwaku Ofosu. 2023. “Chiefs’ Endorsements and Voter Behavior.” Comparative Political Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140231194916.

- Bush, Sarah Sunn, and Lauren Prather. 2022. Monitors and Meddlers: How Foreign Actors Influence Local Trust in Elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Call, Charles T., and Vanessa Wyeth, eds. 2008. Building States to Build Peace. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Cheng, Christine. 2018. Extralegal Groups in Post-Conflict Liberia: How Trade Makes the State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clapham, Christopher. 1998. “Degrees of Statehood.” Review of International Studies 24 (2): 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210598001430.

- Dahrendorf, Ralf. 1980. “Effectiveness and Legitimacy: On the ‘Governability’ of Democracies.” The Political Quarterly 51 (4): 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.1980.tb02520.x.

- De Bruin, Erica. 2020. How to Prevent Coups d’état: Counterbalancing and Regime Survival. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- de Carvalho, Benjamin, and Niels Nagelhus Schia. 2011. “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Liberia and the Case for a Comprehensive Approach to the Rule of Law.” Journal of International Relations and Development 14 (1): 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1057/jird.2010.26.

- Dickson, E. S., S. C. Gordon, and G. A. Huber. 2022. “Identifying Legitimacy: Experimental Evidence on Compliance with Authority.” Science Advances 8 (7): eabj7377. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj7377.

- Durant, T. Clark, and Michael Weintraub. 2014. “How to Make Democracy Self-Enforcing after Civil War: Enabling Credible yet Adaptable Elite Pacts.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 31 (5): 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894213520372.

- Fearon, James D., Macartan Humphreys, and Jeremy M. Weinstein. 2015. “How Does Development Assistance Affect Collective Action Capacity? Results from a Field Experiment in Post-Conflict Liberia.” American Political Science Review 109 (3): 450–469. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055415000283.

- Fisk, Kylie, and Adrian Cherney. 2017. “Pathways to Institutional Legitimacy in Postconflict Societies: Perceptions of Process and Performance in Nepal.” Governance 30 (2): 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12208.

- Gilley, Bruce. 2009. The Right to Rule: How States Win and Lose Legitimacy. New York: Routledge.

- Goldstone, Jack A. 2008. “Pathways to State Failure.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 25 (4): 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388940802397343.

- Gordon, S. C., and G. A. Huber. 2019. “The Empirical Study of Legitimate Authority: Normative Guidance for Positive Analysis.” NOMOS: American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy 61:328.

- Grossman, Allison N., William G. Nomikos, and Niloufer A. Siddiqui. 2023. “Can Appeals for Peace Promote Tolerance and Mitigate Support for Extremism? Evidence from an Experiment with Adolescents in Burkina Faso.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 10 (1): 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2022.1.

- Haass, Felix. 2021. “The Democracy Dilemma. Aid, Power-Sharing Governments, and Post-Conflict Democratization.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 38 (2): 200–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894219830960.

- Hegre, Håvard, Gudrun Østby, and Clionadh Raleigh. 2009. “Poverty and Civil War Events: A Disaggregated Study of Liberia.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (4): 598–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002709336459.

- Hox, Joop J. 2010. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. 2nd ed. Quantitative Methodology Series. New York: Routledge.

- Hunnicutt, Patrick, and William G. Nomikos. 2020. “Nationality, Gender, and Deployments at the Local Level: Introducing the RADPKO Dataset.” International Peacekeeping 27 (4): 645–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2020.1738228.

- Karim, Sabrina M. 2017. “Restoring Confidence in Post-Conflict Security Sectors: Survey Evidence from Liberia on Female Ratio Balancing Reforms.” British Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 799–821. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000035.

- Karim, Sabrina. 2020. “Relational State Building in Areas of Limited Statehood: Experimental Evidence on the Attitudes of the Police.” American Political Science Review 114 (2): 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000716. https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/relational-state-building-in-areas-of-limited-statehood-experimental-evidence-on-the-attitudes-of-the-police/12D6C2437F5859C7EF55277A683421F5.

- Levi, Margaret. 1988. Of Rule and Revenue. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Levi, Margaret, and Audrey Sacks. 2009. “Legitimating Beliefs: Sources and Indicators.” Regulation & Governance 3 (4): 311–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2009.01066.x.

- Levi, Margaret, Audrey Sacks, and Tom R. Tyler. 2009. “Conceptualizing Legitimacy, Measuring Legitimating Beliefs.” American Behavioral Scientist 53 (3): 354–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338797. http://abs.sagepub.com/content/53/3/354.abstract.

- Lipset, Seymour M. 1959. “Some Social Requisits of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” The American Political Science Review 53 (1): 69–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/1951731.

- Matanock, Aila M. 2017. Electing Peace: From Civil Conflict to Political Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Matanock, Aila M, and Natalia Garbiras-Díaz. 2018. “Considering Concessions: A Survey Experiment on the Colombian Peace Process.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 35 (6): 637–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894218787784.

- Mazepus, Honorata. 2017. “What Makes Political Authorities Legitimate? Students’ Ideas about Legitimacy in Five European Democracies and Hybrid Regimes.” Contemporary Politics 23 (3): 306–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1306762.

- McLoughlin, Claire. 2015. “When Does Service Delivery Improve the Legitimacy of a Fragile or Conflict-Affected State?” Governance 28 (3): 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12091.

- Mustasilta, Katariina. 2021. “The Implications of Traditional Authority Contest for Local-Level Stability – Evidence from South Africa.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 38 (4): 457–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894220959655.

- Mvukiyehe, Eric. 2017. “Promoting Political Participation in War-Torn Countries: Microlevel Evidence from Postwar Liberia.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62 (8): 1686–1726. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002717698019.

- Nomikos, William G 2021. “Why Share? An Analysis of the Sources of Post-Conflict Power-Sharing.” Journal of Peace Research 58 (2): 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234332092973..

- Nomikos, William G. 2022. “Peacekeeping and the Enforcement of Intergroup Cooperation: Evidence from Mali.” The Journal of Politics 84 (1): 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1086/715246.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. 2010. “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 47 (5): 651–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310378914.

- Reisinger, Christian. 2009. “A Framework for the Analysis of Post-Conflict Situations: Liberia and Mozambique Reconsidered.” International Peacekeeping 16 (4): 483–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533310903184689.

- Reno, William. 2015. “Predatory States and State Transformation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Transformations of the State, edited by Stephan Leibfried, Evelyne Huber, Matthew Lange, Jonah D. Levy, and John D. Stephens, 730–744. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Risse, Thomas. 2011. Governance Without a State? Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Risse, Thomas, and Eric Stollenwerk. 2018. “Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Annual Review of Political Science 21 (1): 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-023610.

- Rotberg, Robert I. 2004. When States Fail: Causes and Consequences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rothschild, Joseph. 1977. “Observations on Political Legitimacy in Contemporary Europe.” Political Science Quarterly 92 (3): 487–501. https://doi.org/10.2307/2148504.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmelzle, Cord, and Eric Stollenwerk. 2018. “Virtuous or Vicious Circle? Governance Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1531649.

- Snijders, Tom A. B., and Roel J. Bosker. 2012. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Steenbergen, Marco R., and Bradford S. Jones. 2002. “Modeling Multilevel Data Structures.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (1): 218–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088424. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088424.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E., Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul F. Fitoussi. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Accessed November 21, 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/118025/118123/Fitoussi+Commission+report.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. 2018. “Securing Legitimacy? Perceptions of Security and ISAF’s Legitimacy in Northeast Afghanistan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 506–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1504855.

- Tsai, Lily L., Benjamin S. Morse, and Robert A. Blair. 2020. “Building Credibility and Cooperation in Low-Trust Settings: Persuasion and Source Accountability in Liberia During the 2014–2015 Ebola Crisis.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (10–11): 1582–1618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019897698.

- Tyler, Tom R. 1990. Why People Obey the Law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- von Haldenwang, Christian. 2016. Measuring Legitimacy – New Trends, Old Shortcomings? Bonn: German Development Institute.

- Weatherford, M. Stephen. 1992. “Measuring Political Legitimacy.” The American Political Science Review 86 (1): 149–166. https://doi.org/10.2307/1964021.

- Weintraub, Michael. 2016. “Do All Good Things Go Together? Development Assistance and Insurgent Violence in Civil War.” The Journal of Politics 78 (4): 989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1086/686026.

- Wenzelburger, Georg, Sebastian Jäckle, and Pascal König. 2014. Weiterführende Statistische Methoden für Politikwissenschaftler: Die Anwendungsbezogene Einführung mit STATA. München: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag.