ABSTRACT

Effective information behaviour is crucial in all translation competence models but our understanding of how information skills develop and how translators interact with information found in online resources is still limited. In this article we focus on information behaviour (needs and use) of bidirectional translators who frequently translate into their native (L1) and their non-native language (L2). The theoretical underpinnings come from information studies: (1) information is needed when cognitive uncertainty arises and – when found – it allows the translator to make an informed decision; (2) translators are driven by economy of effort and will minimise the cost of searching for information. The empirical evidence comes from a study of 30 professional bidirectional translators who translated two texts into their native language of low diffusion (Polish) and into their non-native major language (English). A close analysis of their information behaviour included data obtained by keylogging, eye-tracking and screen recording, and showed that using online resources adds more cognitive effort when translators work into their L2. We use the results to draft a model of information behaviour which shows how the use of online resources is affected by the translation direction.

1. Introduction

In small translation markets where the home language has a low diffusion translators need to be versatile and translate into their L1 and L2, that is they provide services in bidirectional translation (Pavlović Citation2007b; Whyatt and Kościuczuk Citation2013; Ferreira and Schwieter Citation2017; Chmiel Citation2018). It seems intuitive that when translating into L2, translators will rely more on external support – now this support usually comes from online resources (henceforth OR). To verify this intuition, it seems imperative to understand the cognitive consequences of searching for information in the translation process, especially with respect to the amount of information which is easily accessible in the digital era. This article is an attempt to go back to the basics of information behaviour research and see how the findings can be applied to the use of OR in translation, especially when one of the languages is an LLD – a language of low diffusion (Section 2). Section 3 explores the relationship between information skills and translation expertise, and argues for a better understanding of how directionality affects translation and information needs. To contribute to this cause, in Section 4 we report on the EDiT project in which we observed how translators interact with information in OR during the translation process. We discuss the results of the study and formulate a tentative model of information behaviour in bidirectional translation – the IBiBT model (Section 5), which can be further validated and used in the training of bidirectional translators. In Section 6 we share some suggestions on how our findings can be applied in translator training.

2. Information behaviour

Information literacy – defined as ‘the ability to locate, evaluate and use information wisely’ (Kuhlthau Citation2008, 71), has become indispensable in educational, personal and professional contexts. In the present digital era, translation as a complex cognitive process heavily relies on efficient skills to use information/documentation resources. In search of a solid theoretical footing, we review insights from information studies (Fisher, Erdelez, and McKechnie Citation2005; Case Citation2007). We focus on two main concepts which are of particular interest in the context of translation: the uncertainty principle and the cost-benefit analysis.

2.1. The uncertainty principle and knowledge construction

People look for information when they experience ‘cognitive uncertainty’, i.e. when they become aware that their knowledge is insufficient to reach an intended goal. For example, in Blom’s (Citation1983) Task Performance Model, information need is a task performance need essential for the task to be completed. Dervin (Citation1998, Citation2003) in her ‘Sense-Making Methodology’ also sees information seeking as constructing knowledge in the process of achieving a desired outcome. The information when found acts as a bridge filling a gap between the current situation in which a problem arises and the desired outcome.

In Kuhlthau’s (Citation2008) Information Search Process (ISP) model, uncertainty, or even apprehension is experienced when a person becomes aware that information is needed to complete the task (stage 1). Stage (2) called selection, i.e. deciding what is needed, e.g. typing a query, brings optimism and the searching process starts, followed by exploration (stage 3) – believed to be the most difficult stage as the searcher may experience confusion because of inconsistent results. In stage 4, called focus formulation – the seeker confidently locates relevant information and is ready for collection and presentation (stage 5 and 6) – putting the information to use and completing the assignment. Kuhlthau’s ISP model shows how the initial uncertainty of the information seeker is gradually replaced by confidence and the feeling of closure and satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Kuhlthau (Citation2008) explains that depending on task complexity some stages may be skipped but in more complex tasks all the stages might be experienced.

The above approaches to information needs and use can be applied to translators who resort to information searching when they become uncertain and cannot solve a translation problem (Tirkkonen-Condit Citation2000; Angelone Citation2010). The desired information will fill a missing link in the translator’s knowledge network (see Whyatt Citation2012, 199) and will lead to a decision until another problem arises and the searching–solution cycle starts again. The ISP model points to the cognitive, physical and affective costs of information seeking. Indeed, Hvelplund (Citation2017) used eye-tracking and reported that consulting digital resources takes up a considerable amount of the translation process and the increase in the cognitive load is reflected in ‘longer fixations and larger pupils during resource consultation’ (71).

2.2. A cost-benefit analysis

According to the Optimal Foraging Theory (Sandstrom Citation1994; Pirolli and Card Citation1999), users, in a metaphorical sense, hunt and gather information. As in any rational behaviour, the heuristics of information foraging is based on the principle that the cost of obtaining information cannot be higher than the benefit from the information. The user is interested in fast and easy access to information in line with the principle of least effort (Zipf Citation1949; Mooers Citation1996).

The cost-benefit analysis – the time needed to find and process information – has gained new meaning for translators in the digital age. Access to information is fast but the searching process might be tedious, and requires the decision whether to trust or mistrust the data (Pym Citation2013, 490). On the other hand, access to information is not equally rich for all languages. Kuusi, Koskinen, and Riionheimo (Citation2019, 40–41) report on information seeking during translation involving Karelian, a minority language spoken in Finland and Russia. The authors choose the term information seeking to underline the fact that the information may not be found. To quote:

In the context of minority language translation with limited diffusion and reduced domains, information seeking is, however, rarely a process of easy retrieval, or a straightforward matter of locating authoritative sources and using the most apt terminology, since such preexisting established vocabulary often does not exist.

Paradoxically, the authors conclude that even unproductive information searching leads to knowledge construction (forces students to improve their lexicon and phraseology). Translators’ information behaviour can be embraced by translation pedagogy as a ‘means towards self-discovery and lifelong learning’ (Enríquez Raído Citation2013). Effective information skills are a key factor in translation expertise development (Hirci Citation2012; Pakkala-Weckström Citation2015).

3. Information behaviour and translation expertise

Information behaviour (IB) as a broad term to describe the use of external resources, both offline and online, is central to contemporary translation competence models – PACTE’s instrumental competence (Kuznik Citation2017) and EMT’s thematic and information mining competence (2009). IB is also at the core of the international translation services standard (ISO 17100 Citation2015) and involves a number of behaviours exhibited by experienced translators.

Within the PACTE model, instrumental competence comprises the external support of the decision-making process during translation: the consultation of documentation sources and communication technologies. The use of instrumental resources is characteristic for translators, regardless of translation direction (Kuznik Citation2017). In the EMT model, the thematic and information mining competences are closely intertwined. Thematic competence is knowing how to search for specific information, but the information mining sub-competence is most important: ‘Knowing how to use tools and search engines effectively (e.g. terminology software, electronic corpora, electronic dictionaries)’ (EMT expert group Citation2009, 6). Finally, the ISO standard (Citation2015) states that professional translators should master research tools and efficiently use the information resources at their disposal.

3.1. Expert use of OR

It is tacitly assumed that the translator’s IB develops parallel to the development of translation expertise and becomes a refined skill used with economy of effort (Proctor and Dutta Citation1995, 18). Experienced translators exhibit more complex and effective IB. Hvelplund (Citation2017, 79) notes that information searching as a complex task is more resistant to automation and subject to individual variation. However, certain text types are more demanding as regards information searching than others, i.e. specialised texts will generate more research needs than general-purpose or literary texts (Hvelplund and Dragsted Citation2018). Enríquez Raído (Citation2014, 109) pointed out that experts can skilfully coordinate ‘ST [source text] reading, background research, translation interspersed with selected research, and problem-solving reporting’ with less cognitive strain.

Experts use different types of OR, preferring search engines and parallel texts to dictionaries (Massey and Ehrensberger-Dow Citation2011, 198; Enríquez Raído Citation2014; Paradowska Citation2015). However, Gough (Citation2017, 250) observed that most participants in her study adopted a bottom-up approach, i.e. started with known resources and then moved on to search engine queries. Gough’s (Citation2017) study examined the online behaviour of 16 freelance translators in their natural work environment, translating into their native language from English. One third of the searches involved a top-down approach, i.e. with keyword searches as an initial step (252). Experienced translators also knew about the trustworthiness of OR. They cautiously consulted Wikipedia, aware of its community-generated content (251).

Furthermore, professional translators know a wide array of OR and exhibit a more complex search behaviour as reported by the PACTE group (Kuznik Citation2017; Kuznik and Olalla-Soler Citation2018). Hvelplund’s (Citation2017) study explored search strategies and resource types used by 18 professional translators in L1 translation (English into Danish) of literary and specialised texts. Searching addressed terminological issues and 75% of the searching events referred to bilingual resources/term bases (80–81). The use of other tools indicated the awareness of how to solve a specific problem encountered in the ST (82). One third of the translators used reference websites for information about specialised terminology.

Expert searching involves certain strategies (Enríquez Raído Citation2014), often search engine queries and validations of hunches on different websites. Some experienced translators plan their research, while others operate in a less structured way (Gough Citation2017, 248). Hvelplund (Citation2017, 82) noted that professional translators in his study seemed to ‘make a guess’ when faced with a low-frequency term, ‘possibly because they do not have a set of strategies available to identify a likely translation equivalent’. Professional translators’ searching is often ‘deep’, i.e. involves analysing a number of resources rather than scanning search engine result pages (‘shallow’). It also means the readiness to reformulate and refine queries as new ideas emerge. Furthermore, the knowledge of search strategies increases the use of operators and tendency to validate solutions as shown by Paradowska’s (Citation2015) study of the development of research competence in translation students. Interestingly, Hvelplund (Citation2017, 81) reported that most of his participants performed shallow Google searches, rarely using specialised dictionaries. Moreover, Google images was a search strategy in Hvelplund’s study, which may have some potential in terms of teaching diverse information searching. However, this type of searching is subject to personal preference and might depend on the text type and topic.

The key question in this article is how the direction of translation affects the translator’s IB. It is important to bear in mind that most bidirectional translators work with languages in which they have unequal proficiency due to unequal experience of using both languages. In addition, the status and prestige of the two languages usually differs – e.g. a world major language like English with rich OR and a language of low diffusion (e.g. Polish, Croatian, Finnish) with limited resources.

3.2. The use of OR in L1 and L2 translation

Few translation process research (TPR) studies compare the use of external resources when working into L1 and L2 (Pavlović Citation2007a; Ferreira et al. Citation2016).Footnote1 Buchweitz and Alves (Citation2006) report that students used more resources in the orientation stage (before they started translating) when the ST was in their L2. Ferreira et al. (Citation2016) studied four professional translators with more than six years of experience and found that, contrary to their expectations, three translators allocated more attention (as recorded by the eye-tracker) to the Internet browser when translating into their L1.

Pavlović (Citation2007a, 138) analysed collaborative think aloud protocols and noted that students relied more on OR in L2 translation, and used the solutions they found more often than in L1 translation. She also observed that students displayed individual preferences for certain types of resources irrespective of directionality and commented that:

[R]esources other than bilingual dictionaries (especially the electronic resources) can provide more help in L2 translation, at least when the L2 in question is English. This can easily be explained by the abundance of materials in English on the Internet, compared to the number of texts and tools available in a language of limited diffusion such as Croatian (138–139).

The imbalance in the available resources was also noted by Gough (Citation2017, 247) who observed that translators reported dissatisfaction with the availability of OR while translating into Polish, Hungarian, and Dutch. Kuznik and Olalla-Soler (Citation2018) compared translation trainees to professional translators and generally confirmed a greater reliance on external resources when translating into L2 for both groups. They also found a relationship between the ‘number of resources, time taken on searches, and number of searches’ (49), and the quality (acceptability) of L2 translations but only for professional translators. Livbjerg and Mees (Citation2003, 127) conducted a TAP study and reported that for the students who translated a domain-general text from Danish into English (L2) access to dictionaries extended the time spent on translation by 26 minutes on average, but it did not correlate with the quality of the final product.

The prediction of larger information needs in L2 translation is in line with the current findings from neuroscience and bilingualism research which confirm the so-called L2 cognitive disadvantage. Muñoz, Calvo, and García (Citation2019) review neurocognitive studies and conclude that, ‘differential in vivo patterns for FT [forward translation meaning L2 translation] across methods and translation units suggest that this direction implies greater linguistic and extralinguistic processing demands’ (9).

Christoffels, Ganushchak, and Koester (Citation2013) conducted an event-related potentials (ERP) study of word translation in proficient bilinguals and concluded that translating into L2 was more effortful in terms of lexical retrieval and attentional demands whereas translating into L1 resulted in more effortful comprehension of L2 words (see also García, Mikulan, and Ibáñez Citation2016). Numerous reaction time studies reported that participants were much faster translating words from L2 into their L1 than the other way round (Kroll et al. Citation2010), although the speed of access is modulated by other factors, such as language proficiency, word frequency, concreteness or the degree of semantic overlap between translation equivalents (Duyck and Brysbaert Citation2004; Basnight-Brown and Altarriba Citation2007). Hatzidaki and Pothos (Citation2008) tested English-Greek and English-French bilinguals in a sight translation task and found that more semantic information is activated when translating from L1 into L2 than the other way round, and the imbalance affects translation performance.

Summing up, bidirectional translators resort to external support not only to resolve lexical and conceptual problems, but also to speed up access to their internal mental lexicons (Diamond et al. Citation2014). Larger information needs and more taxing processing demands when working into L2 predict heavier reliance on online resources. Below we report on a study to assess if these insights can be empirically validated.

4. The study

The study is a part of a larger project designed to investigate the effects of directionality on the process of translation and its end product – the EDiT project (Whyatt Citation2018, Citation2019).

4.1. Aims and methods

The aim of the study is twofold. First, we want to see how the translator’s information behaviour impacts the process of translation. Next, we want to see whether translating into L2 requires more support from online resources and is therefore cognitively more demanding than translating into L1.

The research design follows the assumptions that ‘cognitive processing has measurable behavioural correlates’ (Jakobsen Citation2014, 75). We use keylogging (Translog II) and eye-tracking (Eyelink 1000 Plus), which provide an insight into the temporal aspects such as: task duration, time needed to read the text before typing starts (orientation), time for drafting the TT, and time for end revision. Time is taken as a correlate of cognitive effort needed to perform the translation task. Longer pauses during typing and their duration reflect difficulties (uncertainty, indecision) experienced by the translator including searching for information in OR. The eye behaviour of the translator, i.e. the number of times the eyes focus on the ST, TT and on OR, and the duration of the fixations is taken as a correlate of the cognitive effort needed to process the textual input (Pavlović and Jensen Citation2009; Hvelplund Citation2017). The screen capture software (Morae) is used to monitor the way translators interacted with information. We formulated three research questions (RQs):

(1) How does the use of OR affect the process of translation in terms of time and cognitive effort?

(2) Does the direction of translation affect the way translators use OR?

(3) Does the time spent in OR correlate with the quality of translated texts?

4.2. Participants, materials, procedure

Thirty professional translators participated in the study and 26 data sets were analysed.Footnote2 At least three years of professional experience with regular translation (minimum 50 pages per month) was required and participation was remunerated.

The study materials comprised tests gauging language dominance and four STs (around 160 words each) – two in Polish and two in English (see Whyatt Citation2018, Citation2019 for details). Each translation direction featured two different text types (Reiss Citation1976): a product description (descriptive) and a film review (expressive). The texts were balanced in terms of their Gunning Fog readability scores (14.1 for the English texts and 14.2 for the Polish pair). Task order was counterbalanced and the order of texts was randomised to minimise the spill over effects (Mellinger and Hanson Citation2018). All our participants were dominant in Polish, their L1, but also highly proficient in English. They all performed the tasks individually and on the same computer with the screen divided into the Translog window on the left-hand side (ST at the top and the TT at the bottom) and the Internet browser on the right-hand side of the computer screen (see ). This set-up provided easy access to OR without the need to switch windows. To ensure no cross-participant interference regarding the choice of resources or phrasing of search queries, Google Chrome was in private mode.

4.3. Data analysis

The data from keylogging, eye-tracking and screen capture were analysed to answer the three research questions. To answer RQ1, a correlational analysis (Spearman’s correlation) of total task time and time spent in the Internet browser was carried out. A three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a repeated measures design was conducted to see if the average fixation duration as a correlate of cognitive effort is longer when using OR than when working on the ST and TT alone. To answer RQ2, linear mixed effects analyses (LME) were carried out, with participants as random effects and translation direction and text type as fixed effects. The following dependent variables for both directions of translation and text types were explored: time in OR (taken as a percentage of total task time), number of searches, i.e. queries typed in the browser throughout the entire task, number of searches performed in orientation, drafting and revision, the range of OR consulted (how many different sources were used), the kind of OR used (bilingual, monolingual, knowledge resources), and the type of searches performed (single, double or multiple). It was also noted whether the double and multiple look-ups involved a change of sites or a cross-language check (e.g. when an equivalent is found but the translator seeks reassurance in the target language context). In the case of significant interaction effects we conducted post-hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction to control for false positive results in multiple comparisons. Finally, to answer RQ3, Spearman’s correlational analysis was applied: the time spent in OR by translators was correlated with the quality operationalised as the time needed by the proof-readers to correct the translated texts to make them publishable (Whyatt Citation2019).

4.4. Results

The results are presented with reference to each research question.

4.4.1. How does the use of OR affect the process of translation in terms of time and cognitive effort?

The use of OR adds up to the temporal and cognitive effort during the process of translation. There is a statistically significant strong positive correlation between total task duration [s] and time in OR [s] (rs = 0.68, p< 0.0001). The observed relationship is stronger for L2 translation (rs = 0.76) than L1 translation (rs = 0.61), and stronger for product description (rs = 0.82) than film reviews (rs = 0.67). Bearing in mind that using OR disrupts the process of typing the TT, we correlated the number of performed searches with the number of pauses longer than 5 and 10 seconds. Correlation analyses revealed a statistically significant strong positive correlation between the number of searches and the number of pauses longer than 10 s (rs = 0.53, p< 0.0001), and a slightly weaker positive correlation between the number of searches and the number of pauses longer than 5 s (rs = 0.38, p< 0.0001). We found comparable correlation coefficients in both directions of translation and for both text types

A three-way ANOVA (the factors: area, direction, and text type) with a repeated measures design revealed a significant effect of area at which our participants looked (ST, TT, OR), F(2,184) = 155.64, p< 0.0001 on average fixation duration. Contrast analyses showed a significantly longer average fixation duration (greater cognitive effort, p< 0.0001) for the use of OR (M= 320.30 ms) than for the ST reading (M= 222.03 ms), and no significant differences for the use of OR and the visual attention to the TT (M = 313.81 ms), p= 0.360. Interestingly, the effect of the factor area was the only statistically significant effect found here (including all possible interaction effects). The results show that the use of OR (interacting with information) increases cognitive effort irrespective of the direction of translation or the text type.

4.4.2. Does the direction of translation affect the way translators use OR?

The LME analysis showed no statistically significant effect of translation direction (b= −2.58, SE = 2.09, t= −1.24, p> 0.05) in terms of the percentage of the total task time spent in OR. However, we observed a statistically significant effect of text type (b= −7.54, SE = 2.09, t= −3.61, p< 0.01), with our participants spending a significantly higher percentage of total task time in OR when translating product descriptions (M= 23.79) than the film reviews (M= 15.19). The interaction effect of translation direction and text type was not significant (b= −2.11, SE = 2.96, t= −0.71, p> 0.05).

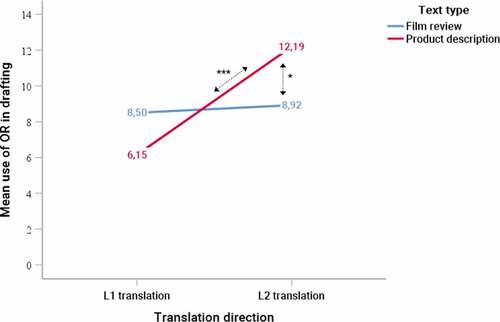

With respect to the number of entries into OR, we found a statistically significant effect of translation direction (b= −5.54, SE = 1.29, t= −4.30, p< 0.001), and of text type (b= −3.58, SE = 1.29, t= −2.78, p< 0.01). The participants performed significantly more searches in OR in L2 translation (M= 11.75) than L1 translation (M= 8.71), and significantly more when translating product descriptions (M= 10.77) compared to the film reviews (M= 9.69). Also, an interaction effect of translation direction and text type yielded statistical significance (b= 5.00, SE = 1.82, t = 2.74, p< 0.01). Significant differences are illustrated in .

Figure 2. Effect of translation direction (x-axis) on the mean number of searches (y-axis) varying as a function of Text type (line) (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

Concerning the stages of the translation process when the translators searched for information, we observed a statistically significant effect of translation direction (b= 0.62, SE = 0.19, t= 3.29, p< 0.01). In the orientation phase the participants used OR significantly more frequently in L1 translation (M= 0.77) than in L2 translation (M= 0.38). The effect of text type was not significant, and neither was the interaction effect (see ).

Table 1. Effect sizes (bs), standard errors (SEs), and t-values for LME models across translation stages

The effect of translation direction was also found to be statistically significant (b= −6.04, SE = 1.26, t= −4.80, p< 0.001) in the drafting phase, with OR used more frequently in L2 (M= 10.56) than L1 translation (M= 7.33). The LME analyses also showed a statistically significant effect of text type (b= −3.27, SE = 1.26, t= −2.60, p< 0.05). While drafting, the participants used OR significantly more in the translation of product descriptions (M= 9.17) than the film reviews (M= 8.71). We also found a statistically significant interaction effect of translation direction and text type (b= 5.62, SE = 1.78, t= 3.15, p< 0.01). depicts the significant differences

Figure 3. Effect of translation direction (x-axis) on the mean use of OR in drafting (y-axis) varying as a function of Text type (line) (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001)

Finally, in the revision phase, none of the investigated effects (translation direction, text type, the interaction thereof) reached statistical significance (see ).

As regards the range of OR used by the participants, no significant effects were observed (translation direction: b= −0.35, SE = 0.29, t= −1.20, p> 0.05; text type: b= 0.15, SE = 0.29, t= 0.53, p> 0.05; interaction of the two: b= −0.23, SE = 0.41, t= −0.57, p> 0.05).

We classified the resources into three categories: knowledge resources (Wikipedia, Google searches for factual information, etc.), bilingual resources (dictionaries, bilingual corpora) and monolingual resources (monolingual dictionaries, thesauri, language advice sites). For the use of knowledge OR, the LME analysis showed no statistically significant effect of translation direction or text type (see ), and no statistically significant interaction effect of these two factors (b= −2.04, SE = 1.06, t= −1.92, p= 0.58).

Table 2. Effect sizes (bs), standard errors (SEs), and t-values for LME models across three kinds of resources

For the use of bilingual OR, the LME analysis revealed a statistically significant effect of translation direction (b= −5.88, SE = 1.27, t= −4.64, p< 0.0001) and no statistically significant effect of text type (see ). The participants used bilingual resources significantly more frequently in L2 (M= 8.38) than L1 translation (M= 5.52). The interaction effect of translation direction and text type yielded statistical significance (b= 6.04, SE = 1.80, t= 3.36, p< 0.01) – the participants used bilingual OR significantly more only when translating product descriptions into L2 (M= 9.50) (M= 3.62 for L1) (p< 0.0001. When translating into L1, our participants used bilingual OR more frequently (p< 0.01) when working on the film reviews (M= 7.42) versus product descriptions (M= 3.62). No other differences were found to be statistically significant.

Finally, there was no statistically significant effect of translation direction, text type, or their interaction effect on the number of times the translators used monolingual resources (see ).

The last aspect of the IB we tested was the complexity of searches performed when consulting OR. Single searches (i.e. one source provided sufficient information to solve a problem) were by far the most frequent irrespective of the translation direction (b= −1.15, SE = 0.79, t= −1.46, p> 0.05) and text type (b= −1.15, SE = 0.79, t= −1.46, p> 0.05). A statistically significant effect of translation direction was found only with a higher number of double (b= −0.42, SE = 0.15, t= −2.83, p< 0.01) and multiple searches (b= −0.58, SE = 0.12, t= −4.64, p< 0.0001) followed by a cross-language check in L2 translation. This points to more cognitive uncertainty when working into L2.

4.4.3. Does the time spent in OR correlate with the quality of translated texts?

RQ3 asks about the impact of IB on the quality of the translated texts. There is a statistically significant moderate negative correlation (rs = −0.353, p< 0.0001) between the time spent in OR by the translators and the time the proof-readers needed to make the translated texts publishable. The negative correlation for L2 translation is moderate (rs = −0.326, p< 0.05) and becomes weaker for L1 translations (rs = −0.295, p< 0.05). It is noteworthy that the recorded negative correlation is not strong.

5. Discussion and sketch of the IBiBT model

The results of the empirical study with experienced bidirectional translators working from Polish (L1) into English (L2) and vice versa show that searching for information in OR has cognitive costs which naturally add up to the complexity of the translation process. The positive correlation between the time spent in the Internet browser and total time needed to translate the experimental texts was slightly stronger for L2 than for L1 translation. Furthermore, reading while searching for information is much more demanding (less linear and in need of dynamic reorientation) than reading the ST, and comparable to the visual attention paid to the emerging TT. These results are in line with Hvelplund (Citation2017), and Livbjerg and Mees (Citation2003, 127) in terms of increased effort when using OR and consistent with Pavlović (Citation2007a) and PACTE (Kuznik and Olalla-Soler Citation2018) in terms of more effort in OR in L2 translation.

Translation direction and its interaction with text type has a significant impact on the information needs and use by the translators but the network of effects is quite complex and dynamic. Significantly more queries were typed in OR when translation was done into L2, and more often in product description texts. This shows more uncertainty when translating into the weaker language (L2), which is justified by neurolinguistic and behavioural studies (Muñoz, Calvo, and García Citation2019). However, bearing in mind the lack of a significant effect of translation direction on the percentage of time in OR, it seems that a lot of consultations were brief but sufficient to act as a bridge in constructing knowledge to make a decision. This confirms the cost-benefit approach in the translator’s IB (Pirolli and Card Citation1999). However, significantly more complex searches (double and multiple with a cross-language check) were needed in L2 translation, most likely to verify the appropriateness of L2 words or phrases. This kind of pronounced uncertainty was not present when working into L1 – most likely because of the richer semantic representation and more reliable language intuition (Kuznik and Olalla-Soler Citation2018).

A more fine-grained approach to the kind of resources used (knowledge, bilingual, and monolingual) shows that most information needs are satisfied by turning to bilingual resources (Hvelplund Citation2017), but this happens significantly more in L2 translation (M= 8.38) than in L1 translation (M= 5.52). Again, directionality interacts with text type, and translating the technical texts requires more support from bilingual resources (dictionaries, bilingual corpora, translators’ forums such as proz.com). Interestingly, there were no significant differences in the use of monolingual resources and knowledge resources. Although the translators rarely used OR in the orientation stage, they used them significantly more often in L1 translation, i.e. when the ST was in their L2 showing the L2 cognitive disadvantage with more information searching in OR to construct meaning (Duyck and Brysbaert Citation2004).

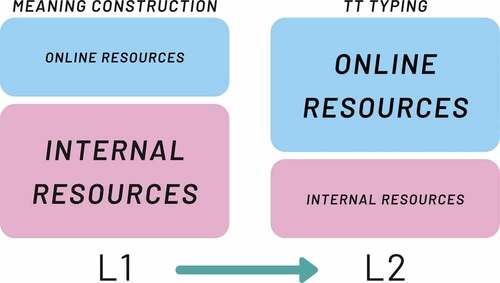

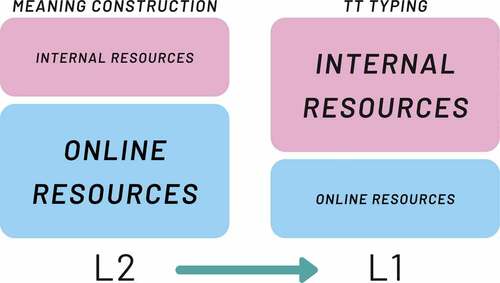

The more effortful processing and significantly more queries typed in the Internet browser occurred when drafting translation in the L2 direction. The study by the PACTE group showed similar patterns, with most consultations in the drafting for the students and professional translators alike (Kuznik and Olalla-Soler Citation2018, 36). Finally, there are no significant effects of translation direction or text type in the revision stage. In this way, our results differ from the PACTE study which showed more use of OR in end revision in the L1 direction (Kuznik and Olalla-Soler Citation2018, 37). The results discussed so far are illustrated in in which the significant differences in IB depending on the direction of translation are visualised in a sketch of a model.

The model shows how the use of ORs in bidirectional translation is driven by cognitive uncertainty experienced at different stages depending on directionality – more support is needed to construct meaning in L1 translation, but when typing the target text, online resources are consulted more in L2 translation. The actual proportion of interaction between the translators’ internal resources and online resources is also modulated by the type of text. The impact of both factors, the direction of translation and the text type, on information needs and use should be made more explicit when preparing students to provide services in bidirectional translation.

Finally, the texts produced by the translators who spent more time in OR needed less time to be corrected, pointing to a correlation between IB and the quality of translation and thus confirming the effective use of online resources. This result has to be interpreted with caution as the correlation is moderate to weak. PACTE (Kuznik Citation2017) found a correlation between the use of OR and the quality of L2 translations for professional translators but not for translation students (also Livbjerg and Mees Citation2003; Pokorn et al. Citation2020). The dynamic interaction between the use of OR, translation expertise, directionality and the quality of translated texts needs to be explored in more detail and the results could prove important for the training of translators (Gough Citation2019), and especially of bidirectional translators.

6. Implications for the training of bidirectional translators

The results of the study highlight the need to prepare future translators who are likely to provide services in bidirectional translation to expect different information needs depending on the direction in which they translate. If they translate between an LLD and, for example English as a lingua franca, they might also experience an imbalance in the available resources. Our participants, being experienced translators, used an equal range of resources in both directions, but L2 translation injected a greater measure of uncertainty into the translation process, compared to L1 translation, therefore some awareness raising tasks could be suggested. For example, trainees could make a record of their information searching when translating a similar text into their L1 and L2 to identify their own information needs depending on the translation direction. Sharing their experiences in the classroom could provide opportunities to discuss the range of available resources for each translation direction, as well as to focus on language-specific cross-cultural issues (Pokorn et al. Citation2020). This is especially important when the students’ L1 is a language of low diffusion and low resources and when, at the beginning of their training they lack the knowledge of which OR are trustworthy (Pym Citation2013).

Avoiding unnecessary risks was demonstrated by the professional translators in our study who, while favouring bilingual dictionaries, performed more cross-language checks when translating into their L2. This shows that, despite their experience in bidirectional translation, they treated the L2 equivalents found in bilingual dictionaries with limited confidence and used them only when the gap between the uncertain and the certain was bridged by an additional check in L2 OR. The translation students could develop this vigilant procedure by using parallel texts to check the potential equivalents they find in bilingual dictionaries or bilingual concordancers. This could be practised either when translating short texts representing various types, or as pre-translation tasks with the focus on the so-called rich points – words which are likely to require the use of OR. The exercise would involve reading and analysing a specialised text (both in L2 and L1) without drafting the translation at all to lessen the cognitive effort of the entire process. Using authentic texts (like the product description in this study) would further allow students to immerse themselves in the task of researching a new domain, its terminology and phraseology to boost their ST analysis and build up their confidence before they start drafting their translation. An alternative task could involve building task-and-text-specific corpora in the source and target languages – the so-called DIY corpora (Bernardini Citation2016). This would illustrate the difference in text availability in LLDs as opposed to the abundance of resources in English for various topics and domains, even very narrow ones. Students would then be able to discuss any potential difficulties they had with finding texts suitable for this exercise and work out procedures to arrive at a satisfactory solution being guided by the information they find (Kuusi, Koskinen, and Riionheimo Citation2019).

Finally, translation students should be encouraged to use information sources wisely in line with their own personal style (Gough Citation2019) and be aware that the process of searching for information adds up to the temporal and cognitive cost needed for translation (Hvelplund Citation2017). The very awareness of different information needs depending on the direction and text type may serve as a compelling argument for translation trainees to allot more time to the stages of the translation process which require more time in OR. Such conscious planning might lead to improving their ability to meet client deadlines. Searching for information is a process with its own physical, cognitive and affective cost (Kuhlthau Citation2008) but the cost of obtaining information should not exceed the benefits from using it.

7. Conclusions

Translation is knowledge intensive work. Translators search for information when they experience uncertainty in their knowledge construction processes in the hope that OR will facilitate their decision making. The results of the study combining keylogging, eye-tracking, screen recordings and the work of proof-readers who corrected the translated texts show that: (1) searching for information adds more cognitive effort to the already demanding process of translation, and slightly more when the translators work into their L2; (2) professional translators experience more uncertainty when producing translation into their L2; (3) the majority of problems are of a linguistic nature and bilingual resources are most frequently used but significantly more in the L2 direction; (4) translators follow the least effort principle and single searches are most common irrespective of the direction; (5) skilful searching for information might have a positive effect on the quality of translated texts, including L2 translations. We used the empirical evidence to model the information behaviour in bidirectional translation and we suggested how the results can be used to raise awareness of different information needs in translation students. The study presented here is not without limitations – it is based on one language pair and professional translators who, most likely have well-tested searching strategies. More research on how information behaviour evolves into efficient skills is needed, especially to give guidance to bidirectional translators in situations when the desired information is not found – e.g. when one of the languages is of low diffusion and there are limited resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Science Centre Poland for supporting the EDiT project (grant No. UMO-2015/17/B/HS6/03944). We are grateful to all of the translators and proof-readers who participated in the project and to our colleagues: Marcin Turski and Tomasz Kościuczuk for their help with collecting the experimental data. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments which helped us improve this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Although the use of external resources (printed dictionaries) was reported in some TAP studies, many later TPR studies did not allow the participants to use OR because: (1) the keylogging program in which the translators worked (Translog) would not record the activity anyway; (2) when eye-tracking was added, using OR was believed to complicate the data collection process (Pavlović and Jensen Citation2009, 95; Lourenço da Silva et al. Citation2017, 117).

2. Four data sets were incomplete. Out of 26 participants 2 were also excluded from the eye-tracking analysis either because of the missing data set or poor quality of the eye-tracking record.

References

- Angelone, E. 2010. “Uncertainty, Uncertainty Management and Metacognitive Problem Solving in the Translation Task.” In Translation and Cognition, edited by G. Shreve and E. Angelone, 17–40. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Basnight-Brown, D. M., and J. Altarriba. 2007. “The Influence of Emotion and Culture on Language Representation and Processing.” In Advances in Culturally-Aware Intelligent Systems and in Cross-Cultural Psychological Studies, edited by C. Faucher, 415–432. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67024-9_19.

- Bernardini, S. 2016. “Discovery Learning in the Language-For-Translation Classroom: Corpora as Learning Aids.” Cadernos De Tradução 36 (1): 14–35. doi:10.5007/2175-7968.2016v36nesp1p14.

- Blom, A. 1983. “The Task Performance of the Scientist and How It Affects an Information Service.” Mousaion 3 (1): 3–26.

- Buchweitz, A., and F. Alves. 2006. “Cognitive Adaptation in Translation.” Letras De Hoje 41 (2): 241–272.

- Case, D. O. 2007. Looking for Information: A Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs, and Behavior. 2nd ed. Oxford: Academic Press.

- Chmiel, A. 2018. “Meaning and Words in the Conference Interpreter’s Mind.” Translation, Cognition & Behavior 1 (1): 21–41. doi:10.1075/tcb.00002.chm.

- Christoffels, I. K., L. Ganushchak, and D. Koester. 2013. “Language Conflict in Translation: An ERP Study of Translation Production.” Journal of Cognitive Psychology 25 (5): 646–664. doi:10.1080/20445911.2013.821127.

- da Silva, L., A. Igor, F. Alves, M. Schmaltz, A. Pagano, D. Wong, L. Chao, et al. 2017. “Translation, Post-Editing and Directionality: A Study of Effort in the Chinese-Portuguese Language Pair.” In Translation in Transition: Between Cognition, Computing and Technology, edited by A. L. Jakobsen and B. Mesa-Lao, 108–134. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/btl.133.04lou.

- Dervin, B. 1998. “Sense-making Theory and Practice: An Overview of User Interests in Knowledge Seeking and Use.” Journal of Knowledge Management 2 (2): 36–46. doi:10.1108/13673279810249369.

- Dervin, B. 2003. “From the Mind’s Eye of the User: The Sense-Making Qualitative-Quantitative Methodology.” In Sense-Making Methodology Reader: Selected Writings of Brenda Dervin, edited by B. Dervin, L. Foreman-Wernet, and E. Lauterbach, 269–292. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Diamond, B., G. Shreve, A. Golden, and D.-N. Valkiria. 2014. “Processing Speed, Switching and Cognitive Control in the Bilingual Brain.” The Development of Translation Competence: Theories and Methodologies from Psycholinguistics and Cognitive Science. edited by J. W. Schwieter and A. Ferreira, 200–238. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10879367

- Duyck, W., and M. Brysbaert. 2004. “Forward and Backward Number Translation Requires Conceptual Mediation in Both Balanced and Unbalanced Bilinguals.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 30 (5): 889–906. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.30.5.889.

- EMT (European Master’s in Translation) expert group. 2009. “Competences for Professional Translators, Experts in Multilingual and Multimedia Communication.” http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/translation/programmes/emt/key_documents/emt_competences_translators_en.pdf

- Enríquez Raído, V. 2013. “Teaching Translation Technologies ‘Everyware’: Towards a Self-Discovery and Lifelong Learning Approach.” Revista Tradumàtica 11: 275–285. doi:10.5565/rev/tradumatica.52.

- Enríquez Raído, V. 2014. Translation and Web Searching. New York: Routledge.

- Ferreira, A., and J. W. Schwieter. 2017. “Directionality in Translation.” In The Handbook of Translation and Cognition, edited by J. W. Schwieter and A. Ferreira, 90–105. New York: Wiley and Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781119241485.ch5.

- Ferreira, A., J. W. Schwieter, A. Gottardo, and J. Jones. 2016. “Cognitive Effort in Direct and Inverse Translation Performance: Insight from Eye-Tracking Technology.” Cad. Trad., Florianópolis 36 (3): 60–80. doi:10.5007/2175-7968.2016v36n3p60.

- Fisher, K. E., S. Erdelez, and L. E. F. McKechnie, eds. 2005. Theories of Information Behavior. Medford, NJ: Information Today.

- García, A. M., E. Mikulan, and A. Ibáñez. 2016. “A Neuroscientific Toolkit for Translation Studies.” In Reembedding Translation Process Research, edited by R. M. Martín, 21–46. Vol. 128. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/btl.128.02gar.

- Gough, J. 2017. “The Patterns of Interaction between Professional Translators and Online Resources.” PhD Thesis, University of Surrey. http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/813254/

- Gough, J. 2019. “Developing Translation-oriented Research Competence: What Can We Learn from Professional Translators?” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 13 (3): 342–359. doi:10.1080/1750399X.2019.1656404.

- Hatzidaki, A., and E. M. Pothos. 2008. “Bilingual Language Representation and Cognitive Processes in Translation.” Applied Psycholinguistics 29 (1): 125–150. doi:10.1017/S0142716408080065.

- Hirci, N. 2012. “Electronic Reference Resources for Translators: Implications for Productivity and Translation Quality.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 6 (2): 219–236. doi:10.1080/13556509.2012.10798837.

- Hvelplund, K. T. 2017. “Translators’ Use of Digital Resources during Translation.” HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business 56 (October): 71. doi:10.7146/hjlcb.v0i56.97205.

- Hvelplund, K. T., and B. Dragsted. 2018. “Genre Familiarity and Translation Processing: Differences and Similarities between Literary and LSP Translators.” In Innovation and Expansion in Translation Process Research, edited by I. Lacruz and R. Jääskeläinen, 55–76. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/ata.18.04tan.

- ISO (International Organisation for Standardisation). 2015. “ISO 17100:2015: Translation Services – Requirements for Translation Services.” http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=59149

- Jakobsen, A. L. 2014. “The Development and Current State of Translation Process Research.” In The Known Unknowns of Translation Studies, edited by E. Brems, R. Meylaerts, and L. van Doorslaer, 65–88. Vol. 69. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/bct.69.

- Judith.F., K., J. G. Van Hell, N. Tokowicz, and D. W. Green. 2010. “The Revised Hierarchical Model: A Critical Review and Assessment.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 13 (3): 373–381. doi:10.1017/S136672891000009X.

- Kuhlthau, C. C. 2008. “From Information to Meaning: Confronting Challenges of the Twenty-First Century.” Libri 58 (2): 2. doi:10.1515/libr.2008.008.

- Kuusi, P., K. Koskinen, and H. Riionheimo. 2019. “Seek and Thou Shalt Learn: Information Seeking and Language Learning in Minority Language Translation.” Translation and Language Teaching: Continuing the Dialogue. edited by M. Koletnik and N. Froeliger, 39–58. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. https://researchportal.helsinki.fi/en/publications/seek-and-thou-shalt-learn-information-seeking-and-language-learni

- Kuznik, A. 2017. “Use of Instrumental Resources.” In Researching Translation Competence by PACTE Group, edited by A. H. Albir, 219–241. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/btl.127.

- Kuznik, A., and C. Olalla-Soler. 2018. “Results of PACTE Group’s Experimental Research on Translation Competence Acquisition. The Acquisition of the Instrumental Sub-Competence.” Across Languages and Cultures 19 (1): 19–51. doi:10.1556/084.2018.19.1.2.

- Livbjerg, I., and I. M. Mees. 2003. “Patterns of Dictionary Use in Non-Domain-Specific Translation.” In Triangulating Translation: Perspectives in Process Oriented Research, edited by F. Alves, 123–136. Amsterdam: Benjamins. doi:10.1075/btl.45.11liv.

- Massey, G., and M. Ehrensberger-Dow. 2011. “Investigating Information Literacy: A Growing Priority in Translation Studies.” Across Languages and Cultures 12 (2): 193–211. doi:10.1556/Acr.12.2011.2.4.

- Mellinger, C. D., and T. A. Hanson. 2018. “Order Effects in the Translation Process.” Translation, Cognition & Behavior 1 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1075/tcb.00001.mel.

- Mooers, C. N. 1996. “Mooers’ Law: Or, Why Some Retrieval Systems are Used and Others are Not.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 23 (1): 22–23.

- Muñoz, E., N. Calvo, and A. M. García. 2019. “Grounding Translation and Interpreting in the Brain: What Has Been, Can Be, and Must Be Done.” Perspectives 27 (4): 483–509. doi:10.1080/0907676X.2018.1549575.

- Pakkala-Weckström, M. 2015. “Student’s Data Mining Skills in Second-Year Undergraduate Translation.” Current Trends in Translation Teaching and Learning 2 (32): 139–170.

- Paradowska, U. 2015. “Expert Web Searching Skills for Translators – A Multiple-Case Study.” In Constructing Translation Competence, edited by M. Deckert and P. Pietrzak, 275–285. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Pavlović, N. 2007a. Directionality in Collaborative Translation Processes. Tarragona: Univesitat Rovira i Virgili.

- Pavlović, N. 2007b. “Directionality in Translation and Interpreting Practice. Report on a Questionnaire Survey in Croatia.” Forum 5 (2): 79–99. doi:10.1075/forum.5.2.05pav.

- Pavlović, N., and K. Jensen. 2009. “Eye Tracking Translation Directionality.” In Translation Research Projects 2, edited by A. Pym and A. Perekrestenko, 101–119. Tarragona: Intercultural Studies Group.

- Pirolli, P., and S. Card. 1999. “Information Foraging.” Psychological Review 106 (4): 643–675. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.643.

- Pokorn, N. K., J. Blake, D. Reindl, and A. P. Peterlin. 2020. “The Influence of Directionality on the Quality of Translation Output in Educational Settings.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 14 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/1750399X.2019.1594563.

- Proctor, R. W., and A. Dutta. 1995. Skill Acquisition and Human Performance.London: Sage Publications.

- Pym, A. 2013. “Translation Skill-Sets in a Machine-Translation Age.” Meta 58 (3): 487–503. doi:10.7202/1025047ar.

- Reiss, K. 1976. Texttyp und Übersetzsungsmethode. Kronberg: Scriptor.

- Sandstrom, P. E. 1994. “An Optimal Foraging Approach to Information Seeking and Use.” The Library Quarterly 64 (4): 414–449. doi:10.1086/602724.

- Tirkkonen-Condit, S. 2000. “Uncertainty in Translation Processes.” In Tapping and Mapping the Processes of Translation and Interpreting: Outlooks on Empirical Research, edited by S. Tirkkonen-Condit and R. Jääskeläinen, 123–142. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Whyatt, B. 2012. Translation as a Human Skill. From Predisposition to Expertise.Poznan: Adam Mickiewicz University Press.

- Whyatt, B. 2018. “Old Habits Die Hard: Towards Understanding L2 Translation.” Między Oryginałem a Przekładem 24 (41): 89–112. doi:10.12797/MOaP.24.2018.41.05.

- Whyatt, B. 2019. “In Search of Directionality Effects in the Translation Process and in the End Product.” Translation, Cognition & Behavior 2 (1): 79–100. doi:10.1075/tcb.00020.why.

- Whyatt, B., and T.Kościuczuk. 2013. “Translation into a Non-Native Language: The Double Life of the Native-Speakership Axiom.” MTM. Translation Journal 5: 60–79.

- Zipf, G. K. 1949. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort: An Introduction to Human Ecology. Cambridge, Mass: Addison-Wesley Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1950-00412-000