ABSTRACT

This research project explores the extent to which historic guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust (provided by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA)) align with the experiences of practising independent-school teachers in the UK. This article presents data from a small-scale exploratory case study carried out in summer 2019 at two different independent-schools in England. Overall, results suggested that there was no definitive alignment between official teaching guidelines and their enactment in classrooms. Teachers’ opinions on what to teach about genocide are more similar to those outlined in existing guidelines than their views on how to teach about genocide. The outcomes of this research advance the case for greater collaboration between educational institutions and practising teachers.

Introduction

In theory, the difference between theory and practice is small. In practice, the difference between theory and practice is large. (Jan L. A. van de Snepscheut, Dutch computer scientist and educational theorist (quoted, Scitech Book News, 2008, xxvii))

The relationship between educational theory and practice is a complex issue. To what extent are transnational policies and pedagogical norms translated – and not translated – into classroom practice? This research project was conceived as an exploration of the extent to which historic guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust provided by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) are substantiated by the wider experiences of practising independent-school teachers.

Teachers are faced with the challenge of translating abstract pedagogical guidelines into workable classroom praxis. The reasons behind an occasional failure to ‘bridge the gap’ between theory and reality have been subject to scrutiny. The sociologist Hallinan, in 1996, identified a disconnect between research centers for educational studies and the actual school environments upon which hypotheses are projected, resulting in ‘a serious communication gap between researchers and practitioners: as a consequence, educators frequently fail to rely on social science research to inform policy and practice.’Footnote1 However, more recent ventures, such as the Education Endowment Foundation Teaching and Learning Toolkit (updated in June 2018) have renewed existing efforts to bring the spheres of theory and practice closer.Footnote2 Naturally, generalized theories of education cannot always take into account the idiosyncrasies of specific school contexts. This research report, therefore, proceeds in accordance with Cheng’s conclusion – drawn from the results of detailed interviews with early-career teachers – that educational guidelines can only hope to ‘equip student teachers with a set of competencies … to cope with the complexity of specific challenges in their everyday teaching work.’Footnote3

Centrally, genocide is undeniably an extremely challenging topic both for educators to teach, and for students to learn. Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel captured this difficulty:

How do you teach events that deny knowledge, experiences that go beyond imagination? How do you tell children, big and small, that society could lose its mind and start murdering its own soul and its own future?Footnote4

Research framework and its limitations

Primarily, this exploratory report seeks to assess the extent to which a range of abstract recommendations of how genocide should be taught and learned align with the classroom experiences of a sample set of independent-school teachers.

Journal articles, monographs, and policy papers have been published concerning the theoretical aims, frameworks and methodology of genocide education. Strategies provided by International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (2018) – now a legacy version – for teaching about the Holocaust, sponsored by the governments of some 31 countries, represent perhaps the most orthodox guidelines against which to frame current practice.Footnote5 These pre-2020 IHRA guidelines form the key points of reference around which this report revolves. For the purposes of this investigation, the fundamental principles of Holocaust education outlined by the IHRA were expanded in order to apply to genocide education as a whole. The findings of this research hopefully demonstrate that the tenets of Holocaust education often can be interchangeable with teaching about other genocides.

Nevertheless, the IHRA guidelines are not without fallibilities. The guidelines were drafted in 2001, and published in 2003. Despite re-editions in 2015 and 2018, few substantial revisions to the original document were made until early 2020, after this research project had taken place.Footnote6 The guidelines are seemingly intended to be global in scope and lack specificity for individual geographical or educational settings. Moreover, the guidelines were composed by the IHRA’s Education Working Group (EWG). It has also been noted that membership of the EWG is primarily composed of policy experts, academics and religious leaders, rather than practising school teachers. German educationalist Bodo Von Borries delivered an especially coruscating appraisal of the IHRA’s representative authority:

In one respect, the IHRA is a lobby group of professionals. This is certainly not all that it is but it does also have this character. This makes the IHRA a very special organisation, and one that is not universally liked. IHRA activists do not represent the majority of their societies, or even, in some cases, of their governments.Footnote7

However, it must be acknowledged that revised IHRA teaching guidelines were issued in early 2020, a few months after this investigation took place. These edited IHRA recommendations displayed a certain degree more interaction with school-based research than previous iterations of the guidelines.Footnote8

Nevertheless, the primary objective of this article is not to moralize on the teaching and learning of genocides. There is no unilateral model of pedagogical efficacy regarding the topic, and as such it is unhelpful to distinguish between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ approaches. Indeed, the contradictions and consistencies between different pedagogical publications raise a wider issue – that deserve more detailed interrogation elsewhere – of who might decree what ‘best practice’ represents.

Research aims

By gauging the experiences of selected teachers, this research seeks to explore, in part, a lacuna within existing genocide literature that has failed to audit contemporary educational practices. Auron noted in 2005 that there were limited ‘surveys or studies of the effectiveness of the existing curriculum materials for teaching about genocide … and information about this matter is therefore lacking,’ and few studies have taken place in the following 14 years.Footnote9 Crucially, existing school-based research in the United Kingdom has focussed on state-maintained settings. By centering itself around independent-school experiences, this report hoped to offer an original contribution to the field of Holocaust education studies by focusing on a lesser-explored type of school.

This report intends to explore several sub-questions directed towards teachers, including: how have teachers directed and applied the content of genocide education units?; which teaching methods and approaches have educators found most practicable in teaching genocide?; what are the practical realities encountered by teachers when teaching about genocide?; and how do teachers feel they could improve their practice when teaching about genocide?

Literature review

The historic IHRA guidelines selected for review continue to be readily available online and thus have the ability to be consulted by teachers worldwide. If anything, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the demand for materials that are accessible remotely. In the interest of research focus, English-language guidelines were prioritized. However, a range of forms (policy papers, practitioner literature and so forth) were sampled in the interest of providing a rounded context to the tenets set out by the IHRA. In the interests of research accessibility and relevance, sampled literature was mostly English-language, and published since 1990. The extensive collections of the University College London Institute of Education (UCL IoE) library provided the main source for the materials consulted.

It is no easy task to condense the vast body of existing work relating to Holocaust teaching practice into a single summary. Yet, during the consultation of the large corpus of relevant literature and research, four thematic ‘categories’ emerged, within which existing guidelines and teachers’ practice could be compared: ‘principles and practicalities,’ ‘curricular content,’ ‘approaches to teaching,’ and ‘teaching methods.’

A review of recommendations concerning how genocide might best be taught yields a wide range of opinions. Between research-based practitioner literature and more theoretical works, there is both contradictory and confirmatory material. Centrally, no particular set of guidelines emerges as infallible, and no overarching consensus can necessarily be drawn.

Section I: practicalities and principles of genocide education

‘Define the terms’Footnote10

Due the potential complexities of issues relating to definition, attempts to implement some form of semantic standardization within genocide education appear useful. These efforts seem to have found resonance in most literature encountered.

Official bodies have established, over time, a rostrum of certain key terms around which genocide education can revolve. Drawing upon the 1944 theorization, by the Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, of genocide as ‘a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves,’ the United Nations definition of genocide (1948) has become a common denominator with which educators have familiarized themselves. Despite its age, the wording of the definition has remained unchanged over time:

any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

• Killing members of the group;

• Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

• Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

• Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

• Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.Footnote11

Accordingly, Melissa Marks’s clear opinion of the pedagogical responsibilities of educators is relatively symptomatic of attitudes that have subsequently been adopted within the wider literature:

five main points need to be taught to students, all of which can be shown in the Holocaust and other genocides, specifically: (1) the meaning of genocide and problems surrounding its early identification; (2) the idea that governments are not always ethical or moral; (3) the effectiveness of propaganda; (4) dehumanization; and (5) using one’s voice to stand up against injustice.Footnote12

Section II: curricular content

More contentious appears to be the unresolved issue of which genocides to teach. Stark discrepancies exist. Provisions for genocide education in the eleven states of the United States of America where its teaching is statutory are more extensive in scope of content than comparative international counterparts.Footnote13 The curricular stipulations of Illinois are typical in the ambitious suggestion that teaching ‘shall include, but not be limited to, the Armenian Genocide, the Famine-Genocide in Ukraine, the Pontian Greek Genocide, and more recent atrocities in Cambodia, Bosnia, From Rwanda, and Sudan.’Footnote14

However, guidelines which suggest the use of just a handful of examples of genocide appear more realistic in their understanding of the availability of resources and time constraints of teachers. Nevertheless, there has also been compelling criticism against the ‘homogenisation’ of genocide education.Footnote15 Due to its wealth of historical resources and teaching materials, alongside its direct European context, the Holocaust has unsurprisingly emerged as the paradigmatic genocide to be taught in British schools.Footnote16 Yet, this approach may be considered parochial. That is, the Holocaust could become a metonym for genocide as a whole. Although the Holocaust is perhaps the stock example of genocide, teachers might be encouraged to acknowledge that several other genocidal lenses exist.

‘Do not be afraid to approach this subject’Footnote17

There is strong evidence to suggest that the successful enactment of teaching guidelines is hindered by gaps in the proficiencies of educators.Footnote18 Fear has the ability to be an inhibitory factor in the implementation of genocide education. A 2007 Historical Association report found that insecurities amongst teachers regarding the depth of their subject knowledge of ‘lesser-known genocides (namely in the Balkans and Rwanda) prevented them from attempting to teach the topics.’ This finding was substantiated by a subsequent larger-scale survey conducted by the Holocaust Education Development Program (HEDP) in 2009.Footnote19 It found that 80% of teachers questioned to rate their factual knowledge of the Genocide Against the Tutsis in Rwanda to be ‘average’ or ‘poor.’Footnote20

Such patterns might have led to an overreliance on questionable teaching resources, such as the 2004 film Hotel Rwanda. The inaccuracies of the film have been laid bare in several coruscating articles, the most detailed of which was published in the Armstrong State University History Journal.Footnote21 Significantly, empirical research further suggests the tangible relationship between this insecure teacher knowledge and subsequent student shortcomings. Andy Pearce notes how a substantial 2015 survey of over 1000 11–16-year olds found that 81% could not name a post-Holocaust genocide.Footnote22

Section III: approaches to teaching

The wariness towards comparative histories in guidelines offered by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – the largest Western Holocaust museum – is challenged by the support of the same practice by UNESCO.Footnote23 Drawing parallels between genocides, according to the UNESCO body for genocide education, allows the ‘analysis of common patterns and processes of genocidal situations that differ from non-genocidal situations,’ and allows the ‘insight into the warning signs and the underlying dynamics of genocide’ that forms the core of the organization’s mission statement.Footnote24

It is notable, however, that both UNESCO and USHMM guidelines primarily drew on panels of university academics for authorship, rather than practising school teachers. Both sets of recommendations might have been advised to use potentially insightful school-based evidence to validate either side of this particular argument. This thought, in turn, offers some context and justification for the study presented in this article. Nevertheless, the rationale offered by UNESCO seems more cogent. UNESCO maintains that historical juxtaposition can result in trivialization, stating that ‘comparison should not lead to minimizing the importance of one or the other event; each should be understood and recognized in its own right and complexity.’Footnote25There is a German aphorism that perhaps captures this sentiment better than its English translation: Vergleich ist nicht Gleichsetzung (‘Comparison does not mean equivalency’).Footnote26

‘Avoid comparing the pain of any one group with that of another’Footnote27

Guidelines issued by the University of Southern Florida call for an avoidance of unhelpful ‘comparisons of pain,’ whereby generalizations implying exclusivity, such as ‘the victims of the Holocaust suffered the most cruelty ever faced by a people in the history of humanity.’Footnote28 It was thought that these approaches might encourage the view amongst students that ‘the horror of an individual, family or community destroyed by the Nazis was any greater than that experienced by victims of other genocides.’Footnote29 However, USF guidelines are themselves simply a secondary re-interpretation of USHMM recommendations, the limitations of which are outlined above.

Equally, both IHRA and USF guidelines do not seem to make the important distinction between comparing genocides as sociological processes – to understand causation, development and so forth – and the comparison of victims’ sufferings. Teachers might be encouraged to avoid both types of comparison, even though the two approaches are not inconsistent per se: just different.

‘Provide your students with access to primary sources’Footnote30

USF recommendations provide a feasible theoretical explanation of how the teaching of genocide can be used as an opportunity to refine the practice of hermeneutics – or the science of interpretation – amongst students. The USF believes that in the teaching of any historical topic, ‘students need practice in distinguishing between fact, opinion, and fiction; between primary and secondary sources, and between types of evidence such as court testimonies, oral histories, and other written documents.’Footnote31 More empirical research amongst students could be used to substantiate these normative arguments.

‘A cross-curricular approach will enrich your students’ understanding’Footnote32

Pedagogical research increasingly points towards the potential benefits of ‘holistic education.’Footnote33 As the 2009 UCL report noted, the Holocaust, by its very nature, is permeated by myriad ‘moral, theological, historical, philosophical, psychological, geographical, and social questions.’Footnote34 Moreover, Farkas’s school-based experimentation in Holocaust education with multimedia and multisensory learning resources in American secondary schools yielded results that suggested that engagement with art, music and movement in classroom settings fashioned positive learning outcomes.Footnote35 Although Farkas’s studies in an American middle-school were both exploratory and small-scale, they offered compelling evidence that this ‘learning style methodology was more productive than traditional instructional’ models and improved students’ ‘empathy, attitudes and transfer of knowledge.’Footnote36

Farkas’s hypotheses were substantiated by a more ambitious subsequent study of school pupils by Thorsen et al. in 2010, which concluded that ‘use of aesthetic sources of genocide testimony which engaged participant-educators emotionally led to student-participants making empathetic and emotional connection to the material.’Footnote37 Indeed, in the Teaching History special edition of 2013, James Woodcock persuasively drew upon his own classroom experiences in order to advocate the use of music to support ‘commemorative cross-curricularity’ when teaching about genocide.Footnote38

Nonetheless, research also highlights lack of confidence manifest in the practices of some teachers. Although now somewhat out-of-date, a 2001 investigation by Cowan and Maitles found an unwillingness of some teachers to stray beyond historical paradigms of genocide, for fear of the multidisciplinary practices such an approach might entail.Footnote39 Again, however, these investigations were limited to a relatively small set of Scottish teachers, and therefore should not be mistaken for wider global trends.

Section IV: teaching methods

‘Create a positive learning environment, with an active pedagogy and a student-centred approach’Footnote40

The statements of normative principle offered by the IHRA find substantiation in empirical research. Student-driven learning experiences find strong support in conclusions drawn from the sustained fieldwork of Maitles and Cowan.Footnote41 Student-led debate has long been encouraged in British classroom settings. In 1988, a report by the National Association of Teaching English (NATE) recommended ‘as many voices in the classroom as possible.’Footnote42

‘Use witness testimony to make this history more “real” to your students’Footnote43

The principle of using testimony material in genocide education appears to have found establishment across both a range of educational institutions and contents of teaching topics. For example, University of Southern California guidelines recommend oral testimonies as the primary teaching resource in secondary classroom situations.Footnote44 In particular, they recommend that the student experiences of learning about the genocide in Rwanda should foremost center around the growing database of accessible audio-visual witness accounts of the mass killings.Footnote45

The general use of testimony has also been corroborated by the year-long observations of nationwide classroom praxis logged in the Jewish Education Service of North America (JESNA) report of 2006. This convincingly large-scale study affirmed that the chief educational benefits of survivor presentations include ‘the immediacy of first-hand experience to convey the reality of the Holocaust, the possibility of personal interaction with Holocaust survivors [and] the emotional power and connection with individuals who experienced the Holocaust.’Footnote46

‘Select appropriate learning activities and avoid using simulations that encourage students to identify with perpetrators or victims’Footnote47

One obvious outcome of an empathic educational approach to genocide is to accentuate the dimension of human suffering. The Israeli historian Avraham surmises that ‘empathy seems a prerequisite for an understanding of the process through which victims were discriminated, isolated, dismantled of every dimension of human dignity, strove to survive and/or finally brought to their death.’Footnote48 However, given the sensitivities of children, it seems counter-intuitive to use simulation activities to achieve these ends. Samuel Totten has produced a strong rebuke of simulation activities, using empirical evidence of some ethical problems they can create. In Totten’s view, ‘for students to walk away thinking they have either experienced what a victim went through … is shocking in its naivety’ and leads to ‘facile oversimplification.’Footnote49 Totten cites an Anti-Defamation League report of a Holocaust simulation in a Florida secondary school that left children ‘distressed and crying.’Footnote50

The historian Beorn has provided a defence of classroom simulation activities related to genocide education. By virtue of the fact that genocide is a topic that forces students to take a ‘leap in their imagination’ because ‘their vocabulary of morality fails them and their vision of a normal world is forced to expand to take in the most divergent visual and written images,’ Beorn reasons that simulation is the only practicable way of allowing pupils a workable insight into the issue.Footnote51 Regardless, Beorn fails to dwell on the clear ethical difficulties associated with activities such as, for instance, reconstruction of a concentration camp in a classroom.

Overall, therefore, this section has provided a brief summary of the key dimensions of the IHRA guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust, and the relevant contextual literature. Clearly, there is a lack of consensus amongst authors and institutions regarding how exactly the Holocaust should be taught. Therefore, there is scope for confusion and wide-ranging practices amongst educators. This study, therefore, had warrant to explore the potentially multifarious ways in which Holocaust education might have manifested itself in a specific educational setting (independent-schools).

Research design and methods

The findings of this small-scale research project make no claims to represent wider patterns within the teaching profession. Although independent (fee-paying) schools are atypical of national education systems, especially in the United Kingdom, the limited range of existing investigations into genocide education in independent-schools offered an intriguing opportunity for further exploration. The independent sector educates approximately 6.5% of the total number of school children in the UK (ISC).Footnote52 As noted above, this decision to focus on independent-schools was driven by the lack of existing research centered around this particular educational environment.

An exploratory, self-contained case study was selected as the most appropriate research model. Exploratory case study allows for the analysis in depth of relatively detailed collections of data and facilitates ‘an emphasis upon the use of narrative.’Footnote53 Likewise, this approach complements the localized nature of the specific research. Data was collected through questionnaires. As a research model, exploratory case study supported the awareness that this localized research project is not representative of large-scale teacher experiments. The two participant schools involved represent a small subset of both the independent-school – and national – educational sector. Despite a lack of generalisability, a small case study provided an opportunity for the collection of rich data from a targeted sample set of participants.

Online distribution of questionnaires was an efficient method, as it was both convenient for remote-access, and facilitated a mixed methodologies approach.Footnote54 Remote online participation by teachers allows more freedom in terms of timescales: participants were given several weeks to complete questionnaires, rather than being restricted by the time constraints of a single timetabled school visit. The features available in online survey software also allowed for simultaneous quantitative and qualitative feedback to the questionnaire administrator. Synchronization with computer software facilitated the easy transfer of data collected into graphical representation. By allowing remote online access, participants benefited in ethical terms. Anonymity was assured, and thus the presence of an interviewer cannot be considered an influencing factor in the responses collected. The potential for bias was removed as much as possible.

Blaxter’s advice to ‘avoid too many questions which are couched in negative terms’ proved particularly instructive in placing emphasis on discovering teaching practices that proved successful for educators.Footnote55 Approaches to questionnaire design were informed by two previous studies: investigations by Short and Reed and the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education (2016) into experiences of Holocaust education in state-maintained schools.Footnote56 Both reports successfully employed ‘mixed methodologies’ that combined questions eliciting short factual or quantitative responses with opportunities for participants to give more detailed qualitative answers to open-ended questions. Through this mixed methodology, key statistical overview data could be enriched through analysis of the formative responses collected from teachers. Question types also required due thought.Footnote57 Each question type selected naturally came with both advantages and limitations. Sample information questions provided a clear informatic and demographic base to research findings, and allowed any subsequent variations in response depending on personal circumstance to be easily identified, whilst maintaining participant anonymity. Nevertheless, reliability was largely dependent on the good faith of participants.

Multiple choice options were chosen to provide participants with ideas for answers that they might not necessarily think of organically if presented with open-ended questions. Equally, by providing the same list of possible answers to every participant, unilateral cross-comparison of given answers was enabled. This approach was balanced against the potential risk of reflecting respondents’ own thoughts inaccurately as highlighted by May.Footnote58

Finally, free text boxes supplied a helpful mechanism of gauging personalized responses to issues, and for allowing the elaboration of related quantitative questioning.Footnote59 This might enhance validity, since respondents can volunteer their own thoughts in an unprompted way. Qualitative responses collected necessarily required a longer period of time to process and analyse than quantitative counterparts, yet provided often more detailed insights.

The questionnaire reflected the four principal thematic categories identified (above) in existing guidelines and literature related to teaching about genocide (primarily the IHRA recommendations): ‘principles and practicalities,’ ‘curricular content,’ ‘approaches to teaching,’ and ‘teaching methods.’

Research administration

In early summer 2019, an online questionnaire survey was circulated amongst History teachers of two co-educational independent-schools. For variety, two different types of co-educational independent-school were selected: a city day school in Eastern England, and a boarding school in a rural part of South-West England. To ensure rigor of research, a pilot survey was arranged at a third independent-school in London. Teaching structures in all schools surveyed were similar, with each individual teacher given relative autonomy to dictate curriculum within broader departmental frameworks. Research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the British Education Research Association (BERA), and full clearance was received from the Ethics Committee of University College London.Footnote60

Results

Framework of results

The questionnaire was divided into four broad sections, based on key recurring themes in existing teaching guidelines, as outlined in Literature Review: ‘principles and practicalities,’ ‘curricular content,’ ‘approaches to teaching,’ and ‘teaching methods.’ Against these areas, the extent to which teachers’ experiences fulfill dominant patterns in current recommendations could be evaluated. Results from both independent-schools were considered together. Within each section, specific teaching guidelines offered by the IHRA, denoted below by bold font, provided a workable framework against which to place in more detail the responses of participants.Footnote61

Sample set and its limitations

In total, 13 independent-school teachers participated in the survey. Eight teachers came from the boarding school in Wiltshire (School M), whilst five teachers were employed at the day-school in Cambridgeshire (School P). As each question was optional, not every question received an answer. However, the overall rate of question response was 93%. Review of omitted questions showed there was no pattern to non-answers, and absent responses generally corresponded to uncontentious questions. As such, it is suggested that failure to answer certain questions is attributable primarily to human error, rather than conscious neglect. These 13 participants represented just a small subset of both the independent-school and national educational landscape, as previously acknowledged.

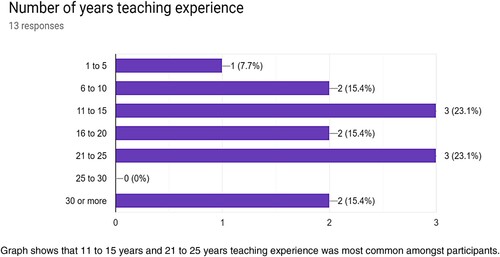

All teachers had experience of teaching History. 46.2% of participants also taught Combined Humanities, whilst in addition 23.1% had taught English, and 7.7% Politics. A wide range of years of teaching experience was represented, ranging from ‘1 to 5’ years to ‘30 or more’ years. Amongst participants, the overwhelming majority of teaching of the Holocaust outside of History public exam syllabi had come as part of ‘Form’ (a cross-curricular humanities course for Year 9 pupils that is unique to the sampled boarding school in South-West England) so might be unlikely to find replication amongst other independent-schools ().

Section I: practicalities and principles of genocide education

Support for genocide education itself found little challenge, although details of its practical application were more mixed. The importance attributed to genocide education by organizations such as the IHRA was reinforced by teachers’ responses. 100% of answers rated the need to teach about genocide as ‘extremely important.’

What were the logistical realities faced by teachers?

The IHRA’s advice to ‘not be afraid to approach this subject’ was heeded. In an independent-school setting, 100% of teachers had taught about the Holocaust, whilst 92.3% of respondents had also taught about other genocides.

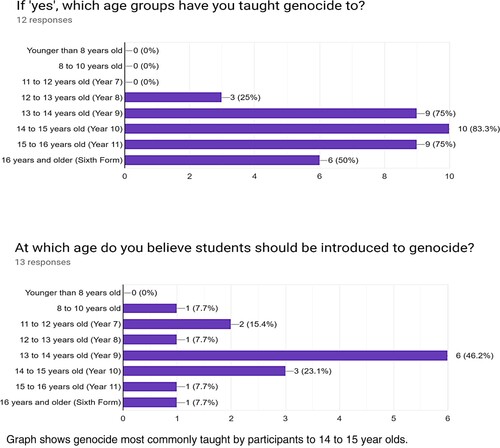

Within the materials selected in Literature Review, the mode average age which it is recommended that genocide is introduced to students is 12-years old. In this regard, the practice of participants showed slight deviation from these recommendations. For 83.3%, teaching of genocide had been undertaken to Year 10 students (14–15-year-olds), whilst 75% had also taught the topic both to Year 9 (13–14-year-olds) and Year 11 (15–16-year-olds). Only three participants had exposed the topic to students aged 12 or under.

However, responses to the question ‘At which age do you believe students should be introduced to genocide?’ hinted at a discrepancy between teacher beliefs and the realities of their experiences. 46.2% of teachers believed that genocide should be introduced ideally at Year 9 stage. The introduction of genocide to students younger than 13 years old was supported by 30.8%, with one participant suggesting that it should come as early as at ages 8–10 years old. Only four participants agreed that genocide was most appropriate for teaching to Year 10 and Year 11 students, despite these being the age ranges to which genocide was most commonly taught. 50% of teachers had also taught genocide to sixth-form students ().

Figure 2. Charts illustrating the discrepancies between the realities and beliefs of teachers in relation to the age at which students are introduced to genocide. Net percentage totals show that some teachers selected more than one answer option.

Teaching of genocide to students in either Year 10 or Year 11 hovered around 2 or 3 h in total, with two responses recording that they spent 5 h on the topic with Year 11 students. Teaching time afforded to Year 9 students, however, was much more generous. One teacher spent a whole term teaching genocide to Year 9, whilst another devoted ‘about 20 h’ of lesson time to the task. Given the range of teachers’ responses, there was little overall conformity or contradiction of existing guidelines to be observed. A middle ground was found in Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) guidelines in the United Kingdom, issued in 1999, which recommended devoting between 8 and 11 h of teaching time to any individual unit of genocide education.Footnote62

These results suggested a manifestation of the pressures of exam-based teaching in the hours of lesson time devoted to the topic of genocide. Indeed, 76.9% of teaching about the Holocaust had come as part of a scheme of work for a public exam board, and thus unsurprisingly had been incorporated into work for year-groups studying for GCSEs or A Levels.

Section II: curricular content

The general curricular direction of genocide education recommended in guidelines found support to a relatively significant degree in the practice of teachers. Specifically, guidelines which suggest using a broad range of historical examples tallied most strongly with teachers’ responses.

Which genocides were taught?

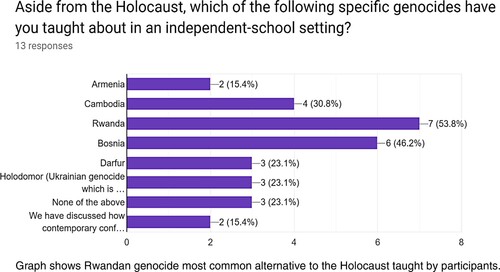

As the paradigmatic genocide, it is unsurprising that the Holocaust emerged as the dominant example, having been taught by all participants at some point. Of the 92.3% of teachers (12 out of 13 participants) who had taught other genocides, however, examples were reasonably diversified by both geography and time period. The fact that three participants had taught none of the genocides on the extensive list of options suggests that some teachers are also incorporating more obscure – if not any less important – historical examples into their teaching ().

Figure 3. Chart illustrating distribution of genocides other than the Holocaust, as taught by respondents.

Although 84.6% of teachers were confident in their own definition of ‘genocide,’ confidence in ‘subject knowledge of genocides other than the Holocaust’ was mixed. 69.2% were ‘somewhat confident,’ 15.4% were ‘very confident,’ whilst 15.4% were ‘not all confident.’ This might suggest that, although teaching of genocides other than the Holocaust might well be occurring, its quality could be variable. This trend could feasibly affect educational outcomes, regardless of how closely teachers align their teaching with existing guidelines.

Section III: teaching approaches

Significant variations emerged in the teaching approaches described by participants. Some of these practices challenged recommendations in existing literatures, whilst some also supported official guidelines.

Which abstract frameworks were adopted by teachers?

As explored in the contextual literature, the use of comparative history is widely debated in existing guidelines. Comparative teaching of genocides was unpopular amongst teachers, overall. Deeper investigation, however, would be required to discover the extent to which teachers conceive comparative history to entail specifically ‘comparing the pain of any one group with that of another’.Footnote63

69.2% of participants indicated a wariness towards comparative teaching, despite several of these respondents previously indicating that it was their aim to link past genocides to modern-day contexts in some way. Indeed, although seemingly unaccustomed to drawing comparisons between different specific genocides, 91.7% of teachers later confirmed that they ‘try to draw comparisons between genocides to other events in present-day contexts.’ At play, there could be a confusion regarding how and why genocides could be linked to other periods of time. Moreover, no teachers’ responses demonstrated convincing evidence of a concern to ‘distinguish between the history of the Holocaust and the lessons that might be learned from that history,’ as guided by the IHRA.

Limited open-text questions on examples of comparative teaching of genocides elicited only vague descriptions of how exactly comparative history methods have been administered by teachers. In general, the idea of relatability emerged as a recurring justification of the technique. One teacher commented that ‘students are very drawn to the idea of a genocide in recent memory,’ whilst another participant noted that leading students from ‘known to unknown as far as possible does appear effective.’

76.9% of teachers stated that they used teaching about genocide to try and develop wider ‘student skills of observation.’ One teacher incorporated ‘source analysis of propaganda.’ In broader terms, another teacher described ‘giving them [students] different materials and asking to do a variety of tasks with them.’ A teacher whose teaching of genocide was centered around exam preparation explained how public exam questions ‘will normally expect pupils to write about the reasons why it happened and how it was implemented,’ and so in other words cultivate the ability to explain causation and effect. Finally, one teacher commented that they offer students the perspicacious advice that ‘writing an exam answer about such horrific content is an unsatisfactory process.’ No other participants demonstrated such awareness of the historiographical difficulties of the task. Indeed, 76.9% of teaching about the Holocaust had come as part of a scheme of work for a public exam board.

Cross-curricular teaching is generally popular in existing guidelines: the IHRA advises that ‘cross-curricular approach will enrich your students’ understanding.’ However, 61.5% of participants had experience of teaching genocide as a cross-curricular topic, despite the cross-subject expertise of the majority of respondents. Given that all teachers surveyed had experience of teaching genocide through History, this result suggests that genocide is still primarily viewed as a historical topic, as opposed to artistic, literary or otherwise. Nonetheless, it could be argued that all participant teachers had engaged in some form of interdisciplinary cross-curricular teaching of genocide within History education, even if they had not themselves realized it. 100% of teachers replied ‘Yes’ to the question ‘Have you used art (e.g. literature, film, paintings) as lesson resources when teaching about genocide?.’ The difficulties inherent in ‘labelling’ teaching approaches thus became apparent. Even if some teachers might not view themselves as subscribing to certain educational frameworks, examination of actual experiences can reveal an unconscious engagement with such strategies.

Section IV: teaching methods

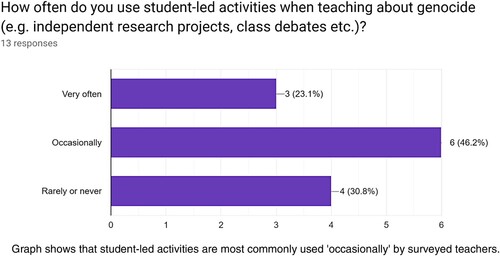

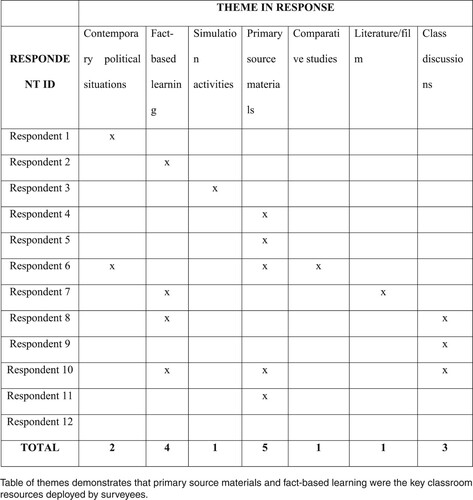

There were also numerous differences amongst teachers’ realisation of genocide education. Again, there was concurrent conformity and challenge to existing recommendations in relatively equal measure ().

Figure 4. Chart showing frequency of teachers’ use of student-led activities to teach about genocide.

Which activities and resources were employed?

The IHRA endorsement of an ‘active pedagogy and a student-centred approach’ when learning about genocide found enactment in a limited number of teachers’ experiences. The questionnaire suggested independent-research projects and class debates as amongst examples of such activities. 23.1% used these types of task ‘very often,’ 46.2% only ‘occasionally,’ whilst 30.8% ‘rarely or never’ arranged such activities.

Rather, 69.2% of teachers replied selected a description of their teaching that both ‘provides students with relevant historical context before embarking on lesson activities’ and ‘encourages students to acquire knowledge independently’ at the same time. In essence, a teaching and learning approach which incorporated both student-led and teacher-led activities appeared most common.

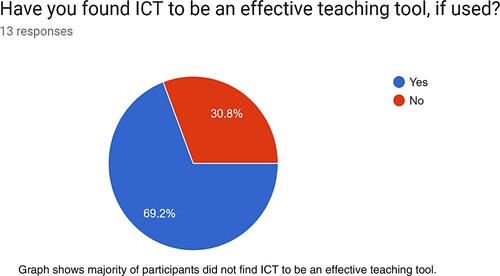

The IHRA advises teachers to ‘be aware of the potential and also the limitations of all instructional materials, including the Internet.’ The use of ICT resources by participants in teaching about genocide was similarly tentative. 38.5% used ICT materials ‘very often,’ 46.2% ‘occasionally,’ and 23.1% ‘rarely/never.’ More detailed investigation would be required in order to find out more about exactly why some teachers do not use ICT on a frequent basis. Interestingly, such divides appeared to fall along generational lines. The teachers who ‘rarely/never’ used ICT all had over 20 years of teaching experience, whilst those who used ICT ‘very often’ all had 15 or fewer years of experience. As new waves of teaching generations advance, therefore, it seems that technology is increasingly being embraced as an educational tool. Of those who did use ICT, 69.2% had found it to be an effective teaching tool. Although 30.8% had not found technology to be an effective teaching tool, this result still perhaps illustrates a commendable willingness of teachers to experiment with new methods, even if outcomes are not ultimately successful ().

Figure 5. Chart showing responses to the question ‘Have you found ICT to be an effective teaching tool, if used?'

Use of classroom ‘simulation’ activities is strongly discouraged in most existing guidelines reviewed. Correspondingly, 92.3% of teachers did not employ such approaches. Moreover, the one teacher who claimed to have had actually used a ‘simulation’ activity perhaps interpreted the term differently. The respondent explained:

I have a simulation activity on the Arab Israeli conflict which encourages pupils to put themselves in the position of the Arabs before introducing the Holocaust, with the intention that pupils carefully consider that conflict in a different light.

However, criticism of ‘simulation’ activities, led by the IHRA, has centered on activities of a different ilk, namely ‘activities that encourage students to identify with perpetrators or victims.’ Examples include recreations of death camps or mass shootings.

When tasked with answering the question ‘which teaching methods have you personally found to be most effective when teaching about genocide?,’ teachers tended to endorse alternative techniques. As above, ‘testimony and written sources’ and ‘historical documentaries’ featured in different answers. It is possible that discursive student-led activities are assumed as implicit features of the latter approaches, and thus did not need articulating ().

Figure 6. Tally chart showing distribution of themes within responses to the question ‘Which teaching methods have you personally found to be most effective when teaching about genocide?' An ‘x’ represents an occurrence of a given theme in each individual response.

Despite this, no respondents indicated experience of exploring the historiography of genocide, in contradiction of the IHRA advice to ‘encourage your students to critically analyse different interpretations.’ However, one teacher’s support of John Boyne’s 2006 novel The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas as a teaching aid was questionable.Footnote64 The literary critic Ruth Gilbert has critiqued the book as an unhelpfully ‘contrived and implausible’ account of life in a Nazi concentration camp, which has nonetheless found widespread manifestation in the curricular schemes of many educators.Footnote65 Of the 9,500 British secondary-school students surveyed as part of large-scale research in 2016, 84.4% of pupils had encountered Boyne’s work as part of their studies.Footnote66 The film critic Manonhla Dargis, in 2008, offered the coruscating opinion that the film adaption of Boyne’s book ‘trivialised, glossed over, kitsched up, commercially exploited and hijacked the Holocaust.’Footnote67

Teachers did appear to subscribe to the IHRA concern to ‘make this history more “real” to students.’ 84.6% of teachers had used ‘teaching methods that specifically seek to engage student empathy/emotion.’ Again, despite the unwillingness of some participants to label their teaching approach as ‘cross-curricular,’ their explanations of empathic classroom activities would suggest otherwise. Teachers who rejected descriptions of their methods as ‘cross-curricular’ employed, amongst other resources, ‘literature texts,’ ‘literary expressions of the Holocaust,’ and ‘well-made movies’ to encourage emotive responses from students. One such respondent even described collaborating with ‘the Design Technology department’ to get ‘pupils to create memorial candles.’

Whilst other teachers favored more historical source material, such as ‘individual testimony,’ ‘footage … showing the liberation of Auschwitz,’ and ‘diary entries,’ the use of stimulus primary or secondary source material was a theme present in all responses. Correspondingly, the IHRA also places importance on the capability to ‘provide your students with access to primary sources.’ Indeed, the IHRA-sponsored ‘technique of using witness testimony to make this history more “real” to students’ found strong alignment with teacher practice, having been used by 92.3% of participants. Testimonies used varied in form and origin. One teacher sourced testimonies from Laurence Rees’ ‘Nazis – a warning from history book and DVD,’ whilst materials from the Holocaust Educational Trust (HET) were cited by multiple teachers.Footnote68 Four other respondents described basing their teaching around visits from genocide survivors to their employer schools.

What challenges were faced by teachers?

When asked ‘What is the biggest difficulty you face when teaching about genocide?,’ two related themes were dominant in teacher responses: the appropriate deployment of graphic material, and the concern to be sensitive to students’ emotions. Both considerations are often cited in existing guidelines. The IHRA advises teachers to ‘be responsive to the appropriateness of written and visual content and do not use horrific imagery to engage your students.’ In this regard, the concerns of participants and the authors of existing recommendations were aligned. Crucially, however, guidelines offer little advice on how best to address these considerations. These misgivings perhaps contributed to a divide in the types of materials employed by teachers. 53.8% stated that they make use of disturbing images in teaching about genocide, whilst 46.2% did not use such an approach.

Overall implications

As explored in the following section Discussion, the extent to which existing recommendations were reflected in teachers’ experiences was variable. The degree to which guidelines such as those produced by the IHRA found enactment in practice was especially limited in relation to the area of ‘approaches to teaching.’ In the other three categories of analysis, substantiation of existing literature was only partial. Clearly, it is not for want of trying that teachers might deviate from official guidelines. When asked ‘Have you actively consulted external resources for guidance before attempting to teach about genocide?,’ 76.9% responded ‘Yes.’

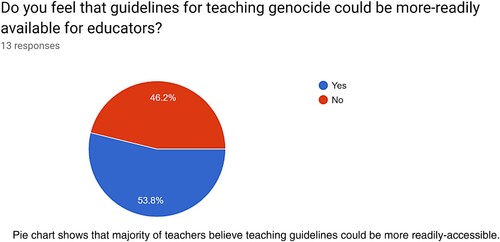

However, subsequent questioning demonstrated that each teacher had consulted different combinations of resources to inform their teaching, ranging from the HET, HMDT, Yad Vashem and Dan Stone’s book The Historiography of the Holocaust (2018), to name a few.Footnote69 Notably, the IHRA had not been consulted by any teachers. With variations existent between many different sets of guidelines, it is unsurprising that teachers’ practices at times contradicted both colleagues and larger bodies ().

Figure 7. Chart showing responses to the question ‘Do you feel that guidelines for teaching genocide could be more-readily available for educators?’

The findings of this research project hint that teachers would in future appreciate a more definitive and authoritative source of guidance to consult. One teacher expressed frustration at ‘The ease with which it's [genocide] wrongly sensationalised, and random stats are dug up and thrown around. You've got to be exact.’ This in turn could address the uncertainties in knowledge about genocides acknowledged by some participant teachers.

Similarly, in response to the question ‘How do you feel that teaching about genocide might be improved or made more effective?,’ two teachers answered ‘not sure’ and ‘no view.’ This suggests that teachers could benefit from clearer external guidance to help develop their own practice in conjunction with concurrent educational evolution. Centrally, it appears that educational organizations would benefit from both increasing the availability of their guidance, and developing the instructiveness of their advice. Strikingly, over half of teachers agreed that ‘guidelines for teaching genocide could be more-readily available for educators,’ despite the possibilities afforded by the advent of the ‘internet age.’ In the case of the IHRA EWG, the committal to ‘make available the practical expertise of its experts’ has not necessarily found realization (IHRA, 2018).

Discussion

Key findings: theory and practice

In conclusion, this exploratory research has suggested a lack of direct connection between the guidelines for teaching about genocide and the actual experiences of independent-school teachers. Responses revealed that each teacher, in some form, had on occasion conformed to – and departed from – existing recommendations. Given the range of opinions exhibited in existing literature, this is not necessarily surprising in itself. Of the four broad educational areas examined through separate questionnaire sections, there was general agreement between existing guidelines and teachers’ experiences in relation to ‘principles of genocide education’ and ‘lesson content.’ Recommended approaches found challenge from teachers to a greater extent with regards to ‘teaching methods’ and ‘approaches to teaching.’ Disagreement primarily came over how – not whether or why – genocide should be taught.

Participant teachers have, in different ways, found it worthwhile on occasion to employ practices that both contravene and conform to official guidelines. Yet, it is perhaps telling that this study was obliged to rely on IHRA Holocaust education guidelines as a launchpad for consideration of genocide education as a whole. The fact that there are not equivalent guidelines for teaching about genocide more broadly is perhaps problematic, and grist for the mill of pedagogues worldwide.

With limited evidence of the outcomes of teaching about genocide, the praxis of each respondent cannot be easily classified as either ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ depending on its correspondence to official advice. To its credit, the IHRA itself acknowledges this fact:

There can be no single ‘correct’ way of teaching any subject, no ideal methodology that is appropriate for all teachers and students … [IHRA guidelines] seek to reflect a continuing process of pedagogical development and improvement and, as such, is not intended as the final word on this subject.Footnote70

Possibilities for future research

Although the limited scale of this exploratory research project has been acknowledged, the replication of the study on a larger scale could present several avenues for future exploration. Naturally, the allowance of time for more detailed questioning of independent-school teachers would reap a deeper understanding of the specificities of existent practices. Future investigation could seek to draw more sustained comparisons, using the aforementioned scholarship, between practices in genocide education in independent-school and state-maintained schools. Specifically, there is scope for an independent-school focused counterpart to the 2009 survey of British state-school teaching experiences, conducted by the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education.

This research project hints at a possible alignment in the experiences of independent-school and state-school teachers. For instance, 30.8% of independent-school teachers surveyed also had experience of teaching about genocide in a state-maintained school setting. Subsequent qualitative responses revealed that these teachers had found there to be little difference in their experiences of teaching about genocide in independent and state-maintained classrooms. Further research could also attempt to ascertain whether deviations in teacher behavior from recommended guidelines took place with an awareness of conflicting existing advice, or whether such contradictions occurred in ignorance of official advice. However, teachers’ appetite for greater accessibility of guidance would suggest that the latter explanation is more plausible. Of course, it also remains to be seen how the ongoing COVID-19 crisis will affect the evolution of Holocaust education.

Recommendations

Nevertheless, this study highlighted the necessity for continual review and regeneration of teaching guidelines. This requirement has seemingly been noted: in 2019, the IHRA embarked upon its first systematic review of its teaching guidelines. New IHRA guidelines were disseminated in 2020, a year after the study in this article took place.Footnote71

Official guidelines should acknowledge both the desire of many teachers to use teaching about genocide as a stimulus to steer student responses to contemporary issues, and the faith of educators in the effectiveness of this approach. Guidelines might more usefully provide advice on how the past and present could be linked in meaningful – even if not identical – ways. In general, as explored in Introduction, there could be merit in closer collaboration between practising teachers and ‘policy experts’ (who form the core of bodies such as the IHRA Education Working Group) to create workable didactic frameworks.

Guidelines also require periodic regeneration in order to respond more substantially to pedagogical and technological developments. If trends such as the advocacy of ‘student-led’ activities are to be endorsed by educational organizations, clearer advice on how such methods could be enacted in the classroom by teachers would be a positive addition.Footnote72

Likewise, examination of teachers’ practices in this research has suggested that the United Kingdom perhaps lags behind its global partners in the embrace of educative technology. In Los Angeles schools, the USHMM has created iPod audio materials for classroom use. Schools in the Czech Republic have also made use of the government-funded Project AMALACH voice recognition Holocaust testimony database.Footnote73

Despite their endorsement by over 30 international governments, the IHRA guidelines had not been consulted by any survey participants. This is despite the IHRA mission for their guidelines to be used in ‘teacher training courses’ and the general expectation that dissemination of its education policy to member states might influence educational systems.Footnote74 This result would hint at a divergence to complement the similar separation of ‘theory and praxis’ in question: the difference between ‘official’ endorsements and the realities of teachers’ consultative actions. If certain guidelines are to be afforded executive sponsorship, it might be sensible for governments to arrange a more widespread distribution of such recommendations to schools themselves.

The wish of some participant teachers to diversify the range of examples of genocide they teach also deserves consideration. Given the dominance of the Holocaust in the field, it is unsurprising that the experiences of survivors who visited schools all related to this specific genocide. If diversification of knowledge is to occur, collaboration between teachers and larger organizations will be required. Teachers must actively seek opportunities to engage with nascent projects, such as the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust’s Rwandan and Bosnian ‘Life Stories’ project.Footnote75 Equally, such organizations must be more forthcoming with materials and activities related to periods other than the 1930s and 1940s. Outreach programs could strive to offer schools the chance to hear from visiting speakers who witnessed genocides more recent than the Holocaust.

How might guidelines be adapted in future?

As previously noted, revised IHRA teaching guidelines were published in early 2020. However, this new iteration addressed only to a limited extent the issues raised by this particular investigation of independent-schools in 2019. Two major themes dominated teachers’ concerns: more curriculum time and greater exploration of conflicts other than the Holocaust. Official bodies could continue to address these wishes in a number of ways. Resources that teachers find to be effective – namely testimony accounts – could be pooled from alternative genocides, such as Darfur or the Balkans. The Holocaust Memorial Day Trust has recently started the collection of an accessible database of Rwandan witness stories. The expression of concern from participants regarding constraints on teaching time could also necessitate a shift in approach on the part of guiding organizations. Guidelines could be firmer in the advice to introduce genocide to students at a stage before time-pressured study for public examinations – in other words, Year 9 or before. Alternatively, guidelines could provide more instructive guidance to teachers about exactly how best to maximize the efficacy of schemes of work that are restricted in lesson time.

Guidelines could also aim for greater differentiation between the capabilities and expectations of different types of educational institutions. Due to greater availability of financial resources and school holiday time, independent-schools might be able to arrange more ambitious extra-curricular activities for students than their state-maintained counterparts. Indeed, 75% of participants confirmed that their employer school had ‘arranged extra-curricular trips/activities related to genocide education.’ Activities ranged from ‘trips to Poland,’ visits to Theresienstadt, lectures and ‘museum trips.’ Official organizations, therefore, could feasibly provide information to teachers on how to oversee extra-curricular activities effectively that was personalized to the geographical and temporal scale of each trip.

How might teachers develop their practice?

The responsibility to guide and develop teaching about genocide also lies with teachers themselves. Although 84.6% of teachers claimed to feel ‘confident’ in their ‘own definition of “genocide”,’ it was notable that 76.9% of participants had never attended a continuing professional development (CPD) training course relating to genocide education. CPD courses are an invaluable opportunity for teachers to refine their practice and learn from experts in the field. In particular, a knowledge of the different interpretations of genocide appeared to be lacking in respondent teachers. Feedback is overwhelmingly positive from teachers who have attended sessions organized by bodies such as the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education.Footnote76 More widespread teacher engagement with such opportunities would facilitate the continuing evolution of genocide education, and also offer practical solutions to concerns held by educators. It is perhaps not coincidental that the responses received from teachers who had attended CPD courses were characterized as most insightful and rounded.

In summary, genocide education is a living organism. Although small in scale, this research study has demonstrated the wide variety of techniques in use in classrooms in England when teaching about genocide. As society continues to evolve, genocide education must adapt in tandem to best address the needs of teachers and students alike. Organizations, such as the IHRA, must provide a key role in ensuring that educators are kept informed and up-to-date with clear guidance of how best to achieve the desired outcomes of genocide education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Adamson

Daniel Adamson is a PhD student in the History Department of Durham University. He holds an MA in History Education from University College London and a BA in History from the University of Cambridge. Previously, Daniel Adamson practised as a teacher of History, and attained a PGCE from the University of Buckingham in 2018. He is a regular contributor to publications of, amongst others, The Wiener Holocaust Library and the British Association for Holocaust Studies (BAHS).

Notes

1 Hallinan, “Bridging the Gap,” 132.

2 Education Endowment Fund, “Teaching and Learning Toolkit.”

3 Cheng, Cheng, and Tang, “Closing the Gap,” 91.

4 Quoted in Auron and Ruzga, The Pain of Knowledge, 161.

5 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

6 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2020).

7 Von Borries, “Learning and Teaching,” 437.

8 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2020).

9 Auron and Ruzga, The Pain of Knowledge, 160.

10 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

11 Quoted in USHMM, “Teaching about Genocide.”

12 Marks, “Teaching the Holocaust,” 130.

13 CoE, “Teaching About the Holocaust.”

14 University of Minnesota, “Teaching Genocide.”

15 Chapman et al., “The Holocaust and Other Genocides,” 2.

16 Ibid., 2.

17 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

18 Cowan and Maitles, Teaching Controversial Issues, 124.

19 Pettigrew et al., Teaching About the Holocaust.

20 Cowan and Maitles, Teaching Controversial Issues, 153.

21 Burton, “Hotel Rwanda: A Twisted Perception.”

22 Pearce, Remembering the Holocaust, 55.

23 USHMM, “Teaching About Genocide”; UNESCO, “Education About the Holocaust.”

24 UNESCO, “Education About the Holocaust.”

25 Ibid.

26 Hirsch and Kacandes, Teaching the Representation of the Holocaust, 147.

27 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

28 USF, “Guidelines for Teaching About the Holocaust.”

29 Ibid.

30 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

31 USF, “Guidelines For Teaching About The Holocaust.”

32 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

33 Bowers, “Holistic Education,” 32.

34 Pettigrew et al., Teaching about the Holocaust, 105.

35 Farkas, How to Teach the Holocaust.

36 Ibid., 65.

37 Thorsen et al., Teaching About Genocide, 166.

38 Woodcock, “History, Music and Law.”

39 Cowan and Maitles, Teaching Controversial Issues, 124.

40 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

41 Cowan and Maitles, Teaching Controversial Issues.

42 Department of Education and Science, “Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Teaching of English Language.”

43 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

44 Culp, “Teaching about Genocide.”

45 USC Shoah Foundation, “Full-Length Testimonies.”

46 Gray, Contemporary Debates, 82.

47 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

48 Avraham, “The Problem,” 37.

49 Quoted in Cowan and Maitles, Teaching Controversial Issues, 126.

50 Quoted in Ibid., 126.

51 Beorn, “Perpetrators, Presidents, and Profiteers,” 73.

52 ISC, “Research.”

53 Scott and Morrison, Key Ideas, 17.

54 Hale and Napier, Research Methods, 36.

55 Blaxter, Hughes, and Tight, How to Research, 201.

56 Short and Reed, Issues in Holocaust education; Foster et al, What Do Students Know?.

57 Denscombe, The Good Research Guide, 41.

58 May, “Social Surveys.”

59 Blaxter, Hughes, and Tight, How to Research, 65.

60 BERA, Ethical Guidelines.

61 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

62 Russell, Teaching the Holocaust, 123.

63 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

64 Boyne, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.

65 Quoted in Cowan and Maitles, Teaching Controversial Issues, 127.

66 Foster et al., What Do Students Know?, 2.

67 Quoted in Pearce, Remembering the Holocaust, 246.

68 Rees, The Nazis; HET, “Teaching Pack.”

69 Stone, Historiography.

70 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2018).

71 IHRA, “How to Teach” (2020).

72 Christenson, Reschly, and Wylie, Handbook of Research.

73 Gray, Contemporary Debates, 102.

74 IHRA, “About the Educational Working Group.”

75 HMD, “Teaching Resources.”

76 Centre for Holocaust Education, “Impact.”

Bibliography

- Auron, Y., and R. Ruzga. The Pain of Knowledge: Holocaust and Genocide Issues in Education. London: Transaction, 2005.

- Avraham, Doron. “The Problem with Using Historical Parallels as a Method in Holocaust and Genocide Teaching.” Intercultural Education 21, no. S1 (2013): 33–40.

- Beorn, W. W. “Perpetrators, Presidents, and Profiteers: Teaching Genocide Prevention and Response Through Classroom Simulation.” Politics and Governance 3, no. 4 (2015): 72–83.

- Blaxter, L., C. Hughes, and M. Tight. How to Research. 4th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2010.

- Bowers, D. “Holistic Education.” The Times Higher Education Supplement: THE 2106 (2013): 32.

- Boyne, John. The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas: A Fable. London: Black Swan, 2007.

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. 4th ed. 2018. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018.

- Burton, A. “Hotel Rwanda: A Twisted Perception.” Armstrong State University History Journal (2017). https://armstronghistoryjournal.wordpress.com/2017/11/16/hotel-rwanda-a-twisted-perception/.

- Centre for Holocaust Education. “Impact.” (2021). https://www.holocausteducation.org.uk/impact/impact-teaching-practice/.

- Chapman, A., C. Counsell, K. Burn, M. Fordham, and P. Salmons. “The Holocaust and Other Genocides.” Teaching History 153 (2013): 2.

- Cheng, May M.H., Annie Y.N. Cheng, and Sylvia Y.F. Tang. “Closing the gap Between the Theory and Practice of Teaching: Implications for Teacher Education Programmes in Hong Kong.” Journal of Education for Teaching 36, no. 1 (2010): 91–104.

- Christenson, Sandra, Amy L. Reschly, and Cathy Wylie. Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012.

- Christodoulou, D. “The Educators.” (2014). Radio Transcript. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04fzd9h.

- Cohen, L., R. Bell, L. Manion, and K. Morrison (eds.). “Chapter 1: The Nature of Enquiry: Setting the Field.” In Research Methods in Education. 7th ed., 1–73. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Council of Europe (CoE). “Teaching About the Holocaust.” (2000). https://rm.coe.int/1680494240.

- Cowan, P., and H. Maitles. Teaching Controversial Issues in the Classroom: Key Issues and Debates. London: Continuum, 2012.

- Culp, L. “Teaching About Genocide.” (2016). https://sfi.usc.edu/blog/lesly-culp/10-resources-teaching-about-genocide.

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. 5th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2014.

- Department of Education and Science. “Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Teaching of English Language.” (1988). http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/kingman/kingman1988.html.

- Education Endowment Foundation. “Teaching and Learning Toolkit.” (2018). https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit/.

- European Teachers’ Seminar, Council of Europe, and Eurimages. Teaching About the Holocaust and the History of Genocide in the 21st Century: Report [of the] 90th European Teachers’ Seminar, Donaueschingen, Germany, 6–10 November 2000. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2003.

- Farkas, R. How to Teach the Holocaust to Middle School Students: Increasing Empathy Through Multi-Sensory Education. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2006.

- Feinberg, S., and S. Totten. Essentials of Holocaust Education: Fundamental Issues and Approaches. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Foster, S. J., A. Pettigrew, A. R. Pearce, R. Hale, A. Burgess, P. Salmons, and R. Lenga. What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools. London: Centre for Holocaust Education, Institute of Education, University College London, 2016.

- Gray, M. Contemporary Debates in Holocaust Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Greener, I. “Chapter 3: Surveys and Questionnaires, or How Can I Conduct Research with People at a Distance?” In Designing Social Research: A Guide for the Bewildered, 38–55. Los Angeles, CA, 2011.

- Hale, Sandra Beatriz, and Jemina Napier. Research Methods in Interpreting: A Practical Resource. New York: Continuum, 2013.

- Hallinan, Maureen T. “Bridging the Gap Between Research and Practice.” Sociology of Education 69 (1996): 131–134.

- Hirsch, M., and I. Kacandes. Teaching the Representation of the Holocaust. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2004.

- Holocaust Educational Trust (HET). “Teaching Pack.” (2018). https://www.het.org.uk/teaching-pack.

- Holocaust Memorial Day Trust (HMD). “Teaching Resources.” (2019). https://www.hmd.org.uk/resources/.

- IHRA. “About the Education Working Group.” (2015). https://2015.holocaustremembrance.com/educate.

- IHRA. “How to Teach About the Holocaust in Schools.” (2018). https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/educational-materials/how-teach-about-.

- IHRA. “How to Teach About the Holocaust in Schools.” (2020). https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/educational-materials/how-teach-about-holocaust-in-schools.

- IHRA. “Recommendations for Teaching and Learning about the Holocaust.” (2020). https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/resources/educational-materials/ihra-recommendations-teaching-and-learning-about-holocaust.

- Independent Schools Council (ISC). “Research.” (2020). https://www.isc.co.uk/research/.

- Marks, Melissa J. “Teaching the Holocaust as a Cautionary Tale.” Social Studies 108, no. 4 (2017): 129–135.

- May, T. “Chapter 5: Social Surveys, Design to Analysis.” In Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process. 4th ed., 93–131. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2011.

- Pearce, A. R. “The Holocaust in the National Curriculum After 25 Years.” Holocaust Studies 23, no. 3 (2017): 231–262.

- Pearce, A. Remembering the Holocaust in Educational Settings. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018.

- Pettigrew, A., S. Foster, J. Howson, P. Salmons, and University of London. Institute of Education. Holocaust Education Development Programme. Teaching About the Holocaust in English Secondary Schools: An Empirical Study of National Trends, Perspectives and Practice. London: Holocaust Education Development Programme, Institute of Education, University of London, 2009.

- Psychologists for Social Change (PSC). “Visioning a New Education System.” (April 2019). http://www.psychchange.org/blog/visioning-a-new-education-system-reduce-exam-tyranny-and-empower-teachers-and-pupils.

- Rees, Laurence. The Nazis: A Warning from History. London: BBC, 2005.

- Russell, Lucy. Teaching the Holocaust in School History Teachers or Preachers? London: Continuum, 2006.

- Scott, D., and M. Morrison. Key Ideas in Educational Research. London: Continuum, 2006.

- Short, G., and C. Reed. Issues in Holocaust Education. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

- Stone, Dan. The Historiography of the Holocaust. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Thorsen, M., Nick Cutforth, Paul Michalec, Sarah Pessin, and Bruce Uhrmacher. “Teaching about Genocide: A Cross-Curricular Approach in Art and History.” ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 2010.

- Tinberg, H., and R. Weisberger. Teaching, Learning, and the Holocaust: An Integrative Approach. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

- Totten, S. Teaching About Genocide: Issues, Approaches, and Resources. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Pub, 2004.

- Totten, Samuel, and Stephen Feinberg. “Teaching About the Holocaust: Issues of Rationale, Content, Methodology, and Resources.” Social Education 59, no. 6 (1995): 323–333.

- UNESCO. “Education about the Holocaust and Preventing Genocide: A Policy Guide.” UNESCO Report (2017). http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002480/248071e.pdf.

- United Nations. “Teaching About the Holocaust, Genocide, and Crimes Against Humanity.” U.N. Report (2010). http://www.un.org/en/holocaustremembrance/EM/partners%20materials/EWG_Holocaust_and_Other_Genocides.pdf.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). “Teaching about Genocide.” (2016). https://www.ushmm.org/educators/teaching-about-the-holocaust/teaching-about-genocide.

- University of Minnesota. “Teaching Genocide.” (2017). https://genocideeducation.org/resources/state-educational-requirements/.

- University of Southern California (USC) Shoah Foundation. “Full-Length Testimonies.” (2018). https://sfi.usc.edu/full-length-testimonies.

- University of Southern Florida (USF). “Guidelines for Teaching About the Holocaust.” (2014). https://fcit.usf.edu/holocaust/sites/USHMM/guideint.htm.

- Von Borries, B. “Learning and Teaching About the Shoah: Retrospect and Prospect.” Holocaust Studies 23, no. 3 (2017): 425–440.

- Woodcock, J. “History, Music and Law: Commemorative Cross-Curricularity.” Teaching History 153 (2013): 56–59.