ABSTRACT

History teachers are unique in their practice of memory, for they have opted, whether consciously or unconsciously, for a profession which advances a collective understanding of the past. This article explores teachers’ intergenerational memories of the Holocaust and the Second World War in France, analysing how these influenced the way in which teachers approached these histories in their classrooms. Through ‘life history’ interviews conducted with teachers in France in 2018, it asks whether teachers found personal or family histories to be “useful” in the classroom, or whether they remained silent or hidden.

Introduction

How the Holocaust is approached by history teachers, is shaped by the cultural and historical context in which it is taught.Footnote1 Teaching twentieth-century history in an international school in the west of Germany forced me to reassess some of the assumptions I had made about history education, its purpose and their relationship between the nation and the past. Whilst I had assumed knowledge and memory to be altered by national and cultural interpretations of history, I was unprepared for national differences in Holocaust pedagogy. Teaching in Germany, I bore new responsibilities for guiding a group of young people through a past that these young people had inherited; a past that German society required them to confront, prompting students to ask questions about, and sometimes challenge, their intergenerational duty to confront the past.Footnote2 An activity on individuals’ choices and responsibilities during the Holocaust, adapted from the Holocaust Educational Trust’s online resources, opened a debate among students about the difference between responsibility and culpability with a tense disagreement about whether young Germans today should feel guilt.Footnote3 The lesson was full of emotion, and perhaps not all of it ‘useful’ or productive.

A British teacher teaching German school children about their national past would seem unthinkable if one were to read Benedict Anderson’s reflections on the construction of nationhood, but this reality left me with questions about the role of teachers’ identity and memory in the classroom. Anderson argues that the concept of ‘the nation’ as an ‘imagined community’ was manufactured by the state, partially through school subjects such as history, geography and language.Footnote4 Specifically, history, ‘employed in particular ways,’ creates a memory that binds a community by producing a shared past.Footnote5 The classroom is often described as a space of socialization; where political, religious, and social statuses are further entrenched.Footnote6 But, in practice, were teachers attempting to, or managing to, manufacture a shared nationhood and citizenship? I reflected on the intersubjectivity in the room: I could not escape my British identity, outwardly manifesting in my accent, mannerisms and socialization. Were my students and I making unconscious assumptions about the other? Was my historical understanding and epistemology shaped by my education and training in Britain; would a German teacher approach the Holocaust differently in the same classroom?Footnote7 Were the reasons I valued Holocaust education personal or professional, or both?

These questions about my own teaching practice were at the origin of my PhD research into teachers’ collective memory of the Holocaust in England and France, during which I analyse the relationship between teachers’ private and public, personal and professional, identities and memories in the classroom. As Elisabeth Worden’s study of schools in Moldova found, teachers talk and tell stories about the nation, subvert the school textbooks, and their own micro-economies, stresses in life and social memory affect how they teach difficult histories.Footnote8 Memory academics such as Jan Assmann and Marianne Hirsch suggest that memory can pass between generations, which allows individuals to imagine memories of an event that they did not experience themselves.Footnote9 Inherited memories feel personal and intimate as they are inherited from trusted and loved family members. This awards them an air of authenticity and can serve as identity markers for younger generations of the family. As this affects how individuals define ‘us’ and ‘them’ when constructing a historical perspective, it can influence how teachers understand the Holocaust and situate their own identity in their teaching.

This article explores French teachers’ family memory, particularly in cases when that memory interacted with their historical memory of the Holocaust. It argues that teachers navigate their own family memories and loyalties with national memories of the Holocaust and imagined conceptions of national identity. At times, teachers synthesized their family memory with dominant national Holocaust memory to facilitate their own sense of ‘belonging’ to the national community.

History teachers are, after all, unique in their practice and observance of memory, for they have opted for a profession, whether consciously or unconsciously, which advances a collective understanding of the past through historical narratives in national curricula, school textbooks and in preparation for national school examinations. At the same time, teachers have pasts and family histories themselves which may enrichen, complicate or challenge their understanding of the past. Whilst there is no reason for teachers’ family memory of the Second World War and the Holocaust to be more exceptional than that of any other professional or social group, teachers are a locus of ‘official,’ cultural, historical and personal crosscurrents of Holocaust memory.Footnote10 We may ask whether Holocaust is inevitably constructed upon subjective knowledge that teachers gather through their personal lenses, or how it may be influenced by other structural forces and factors, including the personal circumstances of the teacher?Footnote11

Teaching your family’s history

In 2018, I conducted 60 ‘life-history’ interviews with history teachers in England and France. This article focuses on the testimonies shared by teachers in France. The interviews enquired about the teachers’ childhood, education, family memories and where and how they had learnt about the Holocaust. A second part of the interview focused on their teaching practices, teaching philosophies, what had changed and remained constant when teaching the Holocaust. I have chosen to include excepts from the French-language transcripts as well as English-language translations, so that the linguistic nuances and ‘true-meanings’ of the texts may be discernible to readers.

Very of the few teachers I interviewed in France had a personal connection to the Holocaust. The majority were born after 1945 and the few teachers who had lived through the Second World War were young children during it. Certainly, none had directly witnessed the Holocaust, though some had family who suffered under Nazi persecution. This article focuses on a small number of French teachers who had a familial or communal connection to the Holocaust that shaped their identity and memory of the Second World War. The memory of the ‘good’ resistance and ‘bad’ collaborators created a binary national identity in France that families were keen to celebrate if they could claim to be from the right side. Teaching allowed them to reembody the values that framed their familial narrative and use their personal connection to the Second World War to make the history more ‘real’ and poignant for their pupils. This was the case with Édouard, a young, enthusiastic teacher who had grown up as the youngest of four brothers in ‘la bourgeoisie intellectuelle de Marseille.’Footnote12 His atheist Jewish father was a professor of mathematics at Aix-Marseille University and his Catholic-born mother worked as a researcher in drug addiction care and recovery. He grew up in what he described as an atheist family in the leafy south of the city, going to school in an affluent and quasi-international public school, studying at the l'Institut d'Études Politiques in Aix-en-Provence, and returning to complete a Masters in Comparative Political Science specializing in the Arab and Muslim world. At this point, struggling for an outlet, he decided to take the agrégation to qualify as a teacher. Édouard knew the history of the Shoah through his ancestral past. When asked whether he learnt about the Shoah at school, he commented,

Je pense que c'était d'abord à l'école. Je pense après, ça ne me concernait pas personnellement puisque les parents de mon père étaient juifs d'Europe de l'Est et mon grand-père a fait les camps de concentration. Il a fait Buchenwald mais en tant que résistant communiste, pas en tant que juif. Voilà donc oui nous en parlons pas mal. Il en parlait beaucoup. J'en avais entendu parler oui à l'école.Footnote13

[I think it was first at school. I think … it didn’t really apply to me since my father's parents were Jews from Eastern Europe and my grandfather lived through the concentration camps. He was at Buchenwald but as a communist resistance fighter, not as a Jew. So yes, we talk about it quite a lot. He talked about it a lot. And yes, I had heard about it at school.]

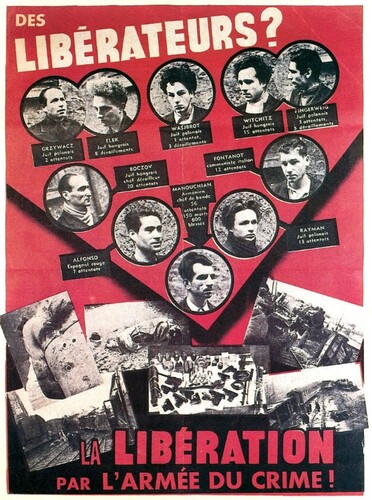

Édouard could not say more regarding his own education about the Shoah in secondary school. His knowledge was constructed around the conversations he had with his father and grandparents. His grandfather originated from the city of Kishinev in Bessarabia (now Moldova) and was of a member of the Manouchian communist resistance group in France, who were the subject of the famous Affiche Rouge (the Red Poster). According to their family legend, his grandfather formed a ‘triangle’ with Jozsef Boczov and Emeric Glasz who were shot at Mount Valérien, after which his grandfather was deported to Buchenwald. His grandmother was also a communist resister, member of the Main d'Oeuvre Immigrée, an immigrant faction of the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans, the communist armed resistance organization, and the sole survivor of a large Jewish family murdered in Bessarabia.

It is likely that Édouard’s school education reinforced the tales he heard at home, as all French school textbooks from the period included several pages of documents relating to the active resistance, often including an image of the famous L’Affiche Rouge, as labelled above (See ). Though school textbooks said nothing about foreigners’ contributions to the resistance, the centrality of this movement in the school program underscored the relevance and significance of his family’s contribution to France during the war, but without the intimacy and sentiment of the stories passed down by his grandfather.Footnote14

Figure 1. L’Affiche Rouge, Paris, 1944.

Despite knowing the fate of his Jewish family in Bessarabia, Édouard was able to celebrate his grandparents’ political connection to the Second World War and to Buchenwald, as these were the stories that survived. His grandparents’ communist history was a point of pride and it clearly shaped the family’s identity and values; he described his upbringing as, ‘c'était vraiment par une culture d'extrême gauche. D'extrême gauche.’Footnote15 [It was really a far-left culture. Of the far-left.] He remembered the Vichy regime not only through the frame of the Shoah, but also for the persecution of communists, and Édouard was keen to attest that his grandfather was sent to Buchenwald for being a communist, not as a Jew. His father had too been deeply engaged in far-left politics and was co-president of the Union Juive Française pour la Paix, a secular, universalist organization founded in 1994, with a mission to defend the Palestinians’ right to a state in the territories occupied by Israel in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. Immersed in the aggressive politics of antisemitism and antizionism, Édouard’s father defended his right to criticize Israel through his family heritage as Jewish resistance fighters in Nazi France.Footnote16 As a result, Édouard’s personal family history was rendered political and public. Consequently, Édouard had no hesitations in using the example of his family when teaching about the Shoah and Vichy France. He commented,

J’en ai parlé oui et je suis, l'an prochain, je jouerai au niveau les troisièmes qui font l'histoire contemporaine. On en reparlera à ce moment-là. Eh oui évidemment je leur en parle toujours de ce que je vis de ce que j'ai vécu des voyages [en Moldavie] que j'ai fait par exemple pour qu'ils comprennent que c'est quelque chose de concret. Je leur demande du sort de ma famille et toute la famille de ma grand-mère en Bessarabie, actuelle Moldavie, sont tous morts. C'est les aider à habituer leur histoire dans des villages et qu'ils ont tous disparu. Ça, j'en parlerai évidemment.Footnote17

[I’ve talked about it yes and next year, I get to teach the third years who do contemporary history. We will talk about it again at that time. Of course, I always tell them about what I saw from my travels [to Moldova], for example, so that they understand that it is something concrete. I ask them about the fate of my family and my grandmother’s entire family in Bessarabia, now Moldavia, who are all dead. It’s helping to familiarize them with their history in the villages and that they all disappeared. I'll talk about that obviously.]

In line with Marianne Hirsch’s concept of postmemory, his retelling of their story seeks to ‘reactivate and reembody’ more distant social/national and archival/cultural memorial structures by reinvesting them with resonant individual and familial forms of mediation and aesthetic expression.Footnote18 The stories preserved the memory of the period and Édouard feared that, ‘au bout d'un moment ça fait peur quand l'évènement commence à devenir très ancien, à un moment ça se perd.’Footnote19 [‘After a while it's scary when the event starts to become very old, at some point it's lost.’] Teaching provided Édouard the space to reactivate his family’s history and embody the history of the Shoah via his ancestors. The narrative of the Shoah he presented to his pupils was more transnational than in other schools, connecting what happened in Bessarabia to histories in France. Rather than narrating the Holocaust through an individual’s story and testimony, as was common in education and remembrance, Édouard looked at a Jewish village where Jewish society, culture and livelihood all perished.

Teaching in the 2010s, Édouard was sure that his pupils were ambivalent towards the ‘Frenchness’ of the French Resistance. He said,

C’est clair que le sentiment d'appartenance à la nation française dans mon collège, il est faible. Il y en a, mais il est faible … Donc c'est clair que la résistance française … Ils voient ça plutôt comme si tu étudiais, toi, la Résistance italienne … Tu peux étudier n'importe quelle personne, n'importe quel pays qui a fait n'importe quoi, à n'importe quel moment et je veux dire on fait de l'histoire … on fait de l’histoire mondiale. Voilà pour nous contre le fait que c'est évidemment dans une optique d'histoire française, bah c'est trop l'histoire mondiale.Footnote20

[It is clear that the feeling of belonging to the French nation at my school is weak. It exists, but it is weak … So, it is clear that the French Resistance … They see it as if you studied, you, the Italian Resistance … You can study anyone, any country that has done anything, at any time, and I mean we do history … we do world history. For us, counter to the fact that it is obviously a French perspective of history, its more world history.]

Édouard’s family memories of the French Resistance as a foreign and communist movement deviated from the nationalist Republican narrative of the period and he was one of only a few teachers who critically discussed its ‘Frenchness.’ The majority of his pupils’ families had migrated from former French colonies of North Africa and had an uneasy relationship with ‘Frenchness.’ Personalizing the Shoah and the French Resistance through his own history was one method of making ‘Frenchness’ less abstract and an efficient tool to erase the layers of identity which formed barriers between his pupils and their acquiescence of ‘French’ history. In a school which he estimated had an 80–90% Muslim population in a predominantly Salafi neighborhood, Édouard was also able to personalize the history of the Shoah. He perceived that his pupils felt a tension with Judaism, the Jewish community and by extension with the history of the Shoah. By connecting it to his life, Édouard could refute rumors that it was made up or exaggerated, bypassing the politics of Israel and Palestine, whilst still defending its legacy for contemporary French citizens.

Édouard’s own historical memory of France during the Second World War also conflicted with the patriotic visions of French Resistance against the Nazi occupation and under the Vichy regime. His grandparents were not French but came to France from Bessarabia. They were Jewish and identified as communists. His grandfather was sent as a political prisoner to Buchenwald under the Vichy regime. His grandmother joined a resistance group made up entirely of immigrants and foreigners, highlighting the absence of ‘Frenchness’ in significant elements of the ‘French Resistance.’ Édouard taught pupils who grew up removed from the mythologies of the French past, due to their religion, their status as ‘issus d’immigration’ and the predominance of their identity as Algerians, Moroccans, Cameroonians over their French citizenship. This enabled Édouard to develop a counter narrative, which whilst still embracing the values of the school curriculum and his own left-wing principles, also stayed true to his family’s experience of the war. His students’ ambivalence towards the French Resistance resonated with his own family story of resisters, immigrants and outsiders who assembled from across Europe to fight against fascism because of their shared values and politics rather than their shared nationality.

Édouard was not worried about relinquishing the ‘guardianship’ of his family history to his school pupils, considered by Hirsch to be ‘at stake’ as the living connection and the past become history.Footnote21 According to Aleida Assmann,

once verbalised, the individual’s memories are fused with the inter-subjective symbolic system of language, and are, strictly speaking, no longer a purely exclusive and unalienable property … they can be exchanged, shared, corroborated, confirmed, corrected, disputed.Footnote22

Though Assmann referred principally to the individual(s) who experienced the event and remembered it directly, in this case Édouard’s grandparents, the same analogy applies to Édouard, whose family history and identity he deposited not in an archive, but in a classroom, to a group of inquisitive, critical and candid fourteen-year-olds. The memory was not only a story, or even just a mnemonic connection to the past, but also a source, to be evaluated by his pupils as a piece of evidence to assess the significance of the Second World War period and the complexities of what it meant to call something French.

Public and private memory

The majority of teachers in this study maintained a separation between their public and private life. Whilst teachers made choices about whether they would share details about their personal circumstances, such as whether they had children, a partner, or siblings, many teachers in France were careful to also separate national narratives of history from personal ones. This conformed to the principles of laïcité [secularism or neutrality towards religion] which enforced a separation of state and religion in French schools, sometimes interpreted as separation of the ‘public’ and the ‘private.’ Édouard was one of the few French teachers willing to bring the personal into the classroom; he was able to do so as his resistance history was affirmed by the celebrated history of the French Resistance, even if his ancestral stories could add nuances to myths and generalizations about the identities of resistance fighters. Most other teachers were adamant that their private life remained private. The majority of French history teachers continued to teach the public narrative of the school program even when it challenged examples or events from their own family history which they believed to be true.

Hélène, a teacher in her fifties, had grown up in a Jewish household in Marseille; her parents and grandparents settled in the city after fleeing Algeria with other pieds-noirsFootnote23 following the Algerian War in 1962. Hélène was clear from the beginning of the interview that the Shoah was a subject of great importance to herself. The events implicated both her grandparents and parents, and she was grateful that they had lived in Algeria rather than France in the 1940s. She remarked,

Moi je suis concernée entre guillemets puisque, moi, mes parents ont été renvoyés de l'école parce qu'ils étaient juifs et … ils ont subi quand même, heureusement pas trop de persécutions parce qu'ils vivaient en Algérie et pas en France. Mais en commençait déjà quand ils étaient donc là-bas enfants, ils étaient obligés à porter l'étoile jaune etc. Donc dans la famille on a donc bien sûr beaucoup parlé et forcément l'histoire de la Shoah, c'est lié quand même à mes origines.Footnote24

[It affects me, in quotation marks, since my parents were expelled from school because they were Jewish and … they still suffered, fortunately not so much persecuted as they lived in Algeria and not in France. But it had already began when they were there as children, they forced to wear the Yellow Star etc. So, in the family we of course talked a lot and inevitably about the history of the Holocaust, since it is linked to my origins.]

Algerian Jews were granted French citizenship in 1870, and by 1940 most Jewish Algerians had adopted the French language and culture and invested in the French regime, despite periodic attacks on Jewish businesses and individuals, often by their Muslim neighbors but sanctioned by the French authorities. Their citizenship was revoked following the establishment of the Vichy regime in 1940, affecting some 110,000 Jewish Algerians, 2000 of whom were interned in forced labor concentration camps.Footnote25 After November 1942, when British and American soldiers landed and took control of Algiers and the rest of Algeria, Jews had their former civil rights and liberties restored, including, in 1943, their French citizenships. As a result, the Jewish population of Algeria had a tumultuous relationship with the French authorities, ‘Frenchness’ and French citizenship.Footnote26 At the dawn of Algerian independence in 1962, 95% of the country's Jewish population went into exile, mostly to France as pieds-noirs or to Israel. Hélène’s parents moved to Marseille, and shortly after Hélène was born.

As a teacher, Hélène adhered to the notion of a universal national curriculum implemented consistently across France. She believed that teachers should adopt a professional identity which maintained the values, history, memory and identity of the French nation, regardless of their own relationship with it. She commented, ‘j'essaie de toujours rester neutre.’Footnote27 [I try to always remain neutral.] A common history syllabus could unify France through shared historical cognisance and adherence to the same Republican values. This conviction was underpinned by the complex memory battles over the place of different categories of Algerian immigrants in France: Muslim Algerians, Maghrebi Jews, Jewish and non-Jewish pieds-noirs and Harkis (Algerians who fought for the French state during the Algerian War of Independence) held different social statuses in France and Algeria along with conflicting narratives of Algerian independence and its legacy.Footnote28 Benjamin Stora has argued that these divided memories of Algeria have been caused by ‘cloistered remembering’ in which each group affirms their own experiences and beliefs by seeking out supportive social and cultural interactions.Footnote29 This posed problems for history teachers, tasked with the formation of French citizens, and who felt threatened by fractured multicultural societies, known in France as communautarisme. In 2005, a much-criticized law stipulated that French school curricula should ‘recognise in particular the positive role of the French presence overseas, notably in North Africa,’ referring primarily to pieds-noirs and Harkis. It was shadowed by an array of heated criticisms that even argued the curricula change violated the fundamental principles of laïcité.Footnote30 Though Hélène was clear about her own political and personal perspectives on contentious histories, to share these and risk igniting a memory war in her own classroom went directly against the assimilationist model of citizenship that she was responsible for developing in her lessons.

Hélène refused to share her Jewish identity and family history as a pied-noir with her pupils. She recognized the effect personal memory could have on her historical perspective and maintained a professional identity whilst teaching as a historian. She remarked,

Mais j'ai toujours essayé de, bien sûr, de ne pas me laisser influencer par ça dans ma façon d'enseigner. Parce qu'un historien, il doit quand même prendre du recul sur ce qu'il enseigne et … Mais forcément on est quand même, on est quand même touché, évidemment après la guerre d'Algérie aussi qui a aussi été quelque chose dont on a parlé dans la famille puisque mes parents étaient obligés de quitter l'Algérie pour venir en France. Et aussi le discours qu'il y avait à la maison était différent par rapport à ce que moi j'apprenais à l'université. Donc il fallait aussi faire … trouver le bon la bonne distance par rapport à ça.Footnote31

[But of course, I've always tried to not let myself be influenced by that in my teaching method. Because a historian must take a step back from what they teach … But inevitably we are still, we are still affected, obviously after the war in Algeria, which was also something we talked about in the family because my parents were forced to leave Algeria to come to France. And also, the discussion at home was different from what I was learning at university. So, I had to … find the right distance regarding that.]

Her experience at university, to accept the alternative narrative put forward by her professor whilst maintaining her own perspective, meant that she was comfortable teaching histories of Judaism and Algeria which conflicted with her own intergenerational memories. She held a conflicted understanding of history as a discipline, the purpose of teaching history in school, and the purpose of history for an individual.

Her role as a teacher superseded her personal response to the Shoah and the Algerian War, which still aroused feelings of anger, fear and relief. Her professional relationship to her personal history was perhaps also maintained by her sense of precariousness as a French Jewish woman. Her parents and grandparents had been awarded and then dispossessed of their French and Algerian citizenship because of their Judaism, and antisemitic attacks and murders increased in France after the turn of the century, including violent attacks in Marseille in 2016. Teaching in a mixed demographic collège [middle school] in Marseille, she could sympathize with her pupils’ perspectives and fears relating to their own ‘outsider’ identity. Keeping her personal history private could also help protect against potential biases and presumptions regarding her own beliefs and politics.

To protect her neutrality, Hélène said that she avoided using ‘mémoire’ or testimony when she taught the Shoah, believing that, ‘on doit donner quand même un cadre précis des évènements qui expliquent l'histoire de la guerre’ [we must provide a precise framework of the events that explain the history of the war]. She tried to teach almost exclusively using historical documents and sources, ‘j'essaye de me centrer, peut-être plus qu'avant, sur les documents’ [I try to focus, maybe more than before, on the sources]. Besides the school textbook, she included graphic and local images of those affected by the Shoah (such as images of Auschwitz and the Camp des Milles) and excerpts from Primo Levi’s If This a Man, and Kressmann Taylor’s Inconnu à cette adresse but refused to show anything she regarded as too emotive or written contemporaneously. Hélène’s insistence on neutrality conformed with the principles of secular education; moreover, it spoke to the ‘Never Again’ objective of Holocaust education by avoiding what she saw as the dangerous identity politics of multiculturalism which she feared segregated and divided communities.Footnote32 The rise of antisemitism in France in the 1990s and 2000s persuaded some French Jewish figures to protect their communities through neo-republicanism. They heralded laïcité as the defence of French liberty of conscience and the protection against communitarianism.Footnote33 As a result, Hélène was certain about her role as a state school teacher, where she was bound by duty to be objective, and as a result felt secure about relying on historic documents to navigate the history of the Shoah.

Hélène’s guarded approach to that period in history perhaps responded to the identity clashes in Marseille and particularly in her classroom. Postcolonial studies have theorized about the adoption of hybrid identities, when individuals from different cultures ‘meet, clash and grapple with each other.’Footnote34 Beside the power dynamic between teacher and pupil, teachers are often faced with an asymmetry in their power with relation to their culture, socio-economical capital, residence or citizenship status, and their race and religion. Thus, pupils and teachers reveal only the part of themselves and their character that might be accepted in the public space of the school where the strict enforcement of laïcité imposes strict secular cultural codes, and teachers are perceived as representatives of the state. For some, the school is thus a place for the performance of one’s ‘public’ character while other identities remain hidden.Footnote35 It is possible that teachers such as Hélène chose to keep silent their private memories, history and identities in order to conform with their role as instructors and so as not to complicate the teacher-pupil relationship and to encourage her pupils to act like her.

Silences within families

Whilst most of the interviewed teachers adopted a professional identity from the moment that they entered the school or the classroom, which regulated their choice of language, dress code and models of behavior, in France public schools were also subject to strict regulations concerning laïcité. French teachers like Hélène prioritized their public role as representatives of the Republic. Hélène’s inherited memories were subsumed by her French identity when she was teaching; to engage with her communauté in the public space of a school could risk endangering freedom of mind and judgement. In Malik’s case, born to Algerian Muslim immigrants who had fought for France during the Algerian War of Independence, his family had been forced to flee Algeria upon its independence, yet he also felt rejected by the French Republican model of citizenship that Hélène valued so dearly.

Malik was born in Marseille in 1968 and taught there from 1999 onwards. His relationship with education and schooling was unique among teachers and influenced his beliefs about history and citizenship education. He started his interview by stating, ‘mon enfance, moi, je suis un produit de l'échec scolaire.’Footnote36 [As for my childhood, I am a product of educational failure.] According to Mailk, he was expelled from school because of his parents’ race, religion and status as Algerian immigrants. As a result, he did not possess the necessary skills to succeed in education, or to reintegrate into the state school system, and instead had to enroll in a Catholic private school. His love of knowledge and learning led him to study history at Aix-Marseille University. As an issu de limmigration [of immigrant background], growing up in the banlieues défavorisée [disadvantaged suburbs] of Marseille, Malik had gained an appreciation for the power of education. His Algerian parents were both illiterate. They had moved to Marseille after the Algerian War of Independence. His father chose to fight for the French army, so as a Harki, he had a complicated relationship with his Algerian and French identities, encountering feelings of rejection from both nations.

The Algerian War was difficult for his parents and was a taboo subject at home. Despite the silence, he recognized the legacy of the war on his own life. He said, ‘ils ont dû un petit peu prendre des décisions importantes qui ont eu un effet sur notre histoire – mon histoire à moi … c'est des actes politiques en fait.’Footnote37 [They had to make a few important decisions that had an impact on our history, my history … they were political acts actually.] The silence prompted Mailk’s interest in his family’s past. He commented, ‘ça a été mon besoin d'aller faire des études d'histoire. Même si je ne suis pas allé travailler sur l'Algérie, mais j'ai pris d'autres questions qui m'ont ramené vers l'Algérie par mes études.’Footnote38 [I needed to study history. Although I did not study Algeria, I studied other questions that brought me back to Algeria.] History was not merely the study of the past, but something alive, provoking and productive in Malik’s life.

Perhaps driven by his family’s rejection from society and their struggle to be recognized as citizens and as ‘nationals,’ the concept of citizenship was incredibly important to Malik’s teaching:

Vivre ensemble! Ces éléments-là, j'essaie dans le cadre de mon enseignement de pouvoir leur transmettre … ce n’est en tout cas pas toujours simple parce que le programme, c'est beaucoup sur « il faut voter ». « Il faut aller voter quand vous aurez dix-huit ans. » « Vous voterez! » Mais, c'est plus que ça, c'est vraiment pour la démocratie, l'acte de citoyenneté.Footnote39

[Live together! I try to transmit these notions within the framework of my teaching, to … in any case it’s not always simple because the curriculum is focused on ‘it is necessary to vote.’ ‘You have to vote when you turn eighteen.’ ‘You will vote!’ But, it's more than that, it's really for democracy, the act of citizenship.]

His conception of citizenship centered on an ideal of an inclusive, pluralist France, in which a ‘good’ citizen was one who lived peacefully and cooperatively with his or her neighbor, regardless of their identity. Unlike history teachers who focused their civic efforts on the act of voting (for non-extremist candidates), his broader definition of democracy involved the development of a tolerant citizenry.

His personal experience of the state school system rendered Malik suspicious of teachers who defined themselves as French Republicans and held rigid and exclusive interpretations of laïcité.Footnote40 Though he was Muslim, he therefore chose to teach in a Catholic school. He remarked,

Je constate qu'il y a beaucoup d'élèves des familles qui considèrent que leur religion est honteuse. Doit être cachée … J'habite dans une banlieue popularisée, d’une religion qui promeut les attentats … ça donne des phénomènes psychologiques, des comportements, des attitudes soit de repli, soit de rejet, soit de … Citoyenneté, c'est coopérer, c'est se comprendre, c'est donner une place à la diversité. Voilà, Je pense que dans l'enseignement catholique soit un peu plus en avance.Footnote41

[I notice that there are many students from families who consider their religion as shameful. It must be hidden … I live in a poor district, I’m of a religion that promotes [terrorist] attacks … this gives rise to psychological experiences, behaviours, attitudes of withdrawal or rejection, or of … Citizenship, however, means cooperating, understanding each other, giving space for diversity. So, I think Catholic education is a little more advanced.]

Despite his misgivings about laïcité, Malik kept his family history and his identity as an Algerian and as a Muslim hidden from his pupils, even when they directly asked him questions about it. He taught the Algerian War as part of the curriculum but found that the history of decolonization created ‘opposition’ in his classroom, sometimes between him and his pupils. He believed many students were apathetic or resistant to learning more, particularly if what they learnt in the classroom conflicted with what they heard from family members. Malik thought that inclusive citizenship was best taught through the study of history and, whilst this period of history was rich on lessons concerning citizenship, there was not yet space for dialogue beyond historical interpretation. In comparison, Malik believed the memory battles over the history of the Shoah had subsided. In Malik’s school, he found no issues of antisemitism. The Shoah could therefore serve as a conduit to wider lessons about the fragility and importance of citizenship:

Je montre au moment où la citoyenneté disparaît, avec Vichy, de notre régime … en quatre ans, notre système change, les libertés disparaissent et se mettent en place des modes de répression, les gens doivent se cacher etc. Et je trouve que c'est l'un des moments clés dans l'apprentissage pour comprendre un peu que la citoyenneté c'est fragile … Je pense que c'est la période [la Shoah] qui permet le mieux dans les programmes scolaires d'aborder cette question-là et la période coloniale, que c'est intéressant pour comprendre que la citoyenneté ne peut exister-là, juste à côté.Footnote42

[I demonstrate the moment when citizenship disappears, with Vichy, from our regime. … in four years, our system changed, freedoms disappeared and were replaced by modes of repression, people had to hide etc. And I find that this is one of the key moments in education to understand that citizenship is fragile … I think this [the Holocaust] is the best time in school curricula to address this issue, and the colonial period is interesting in order to understand that citizenship may not exist, right next door.]

He called Vichy ‘notre régime,’ expressing an ownership of France’s culpability that was absent in many of the most devoted teachers’ lessons. Whilst he believed it to be a dark period in France’s history, he did not frame it as a ‘blip’ in an otherwise progressive line of Republics. France’s rejection of its Algerian citizens provided Malik with evidence of citizenship’s fragility elsewhere. The history of the Shoah provided a powerful testament to the dangers of state power if people succumb to prejudice, and thus the Holocaust was the best place in the curriculum that Malik could transmit his values and concerns for France in his vocation as a history teacher. The inclusion of Holocaust education within the troisième [grade nine] school program reflected the growing necessity for social cohesion as France accepted its growing diversity and the need for different communities to live peacefully together. Malik’s approach to Holocaust education gently attempted to establish citizenship as contractual between the individual and the state as well as between citizens.

Harmonizing family and national Holocaust memories

On only rare occasions were teachers subject to memories which conflicted with the narrative they taught in the classroom. For example, Frederic knew he had Polish great uncles who were imprisoned in Auschwitz during the Holocaust as Catholic rather than Jewish Poles, a history that was submerged under narratives of Jewish victimhood in French Shoah education. He taught in Aix-en-Provence but was born in Besançon in the north east of France, where he went to school, university and acquired his first teaching post, moving to Aix during a period where there were numerous vacant teaching posts in the Bouche-de-Rhône département. His mother was born to two Catholic Poles who had fled from Poland to France during the Second World War. His grandparents, therefore, spoke little French and he grew up listening to both Polish and French in the household. When he was eight years old, his parents took him back to Poland to learn about his heritage, culture and history. There he first encountered the history of the Holocaust and that of his Polish family. His visit included a trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Mon grand-père donc maternel, il était d'origine polonaise. Il est né, il était né avant, pendant la guerre de quatorze – dix-huit. Il était né dans une zone en fait qui était déjà allemande mais qui était devenue ensuite polonaise. Donc mon grand-père après quand il est arrivé en France il avait une envie, c'est de retourner en Pologne pour retrouver un peu des traces de sa famille que, quand ils sont arrivés en France ils avaient perdu des traces de ses oncles et de sa famille. Donc, on est allé aussi visiter la région d'Auschwitz.Footnote43

[My maternal grandfather, he was of Polish origin. He was born, he was born before, during the First World War. He was born in an area that was actually already German but then became Polish. So, my grandfather after he arrived in France, had a desire to return to Poland to find some traces of his family as when they arrived in France, they had lost track of his uncles and of his family. So, we also went to visit the region of Auschwitz.]

Frederic’s grandfather’s family had to flee German aggression during the war. His family lived on the German-Polish border, and starting in 1939, many Poles living in land annexed by the Germans were expelled eastward, or, if they resisted, sent to concentration camps. Some of Frederic’s great uncles were interned and died in Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp for organizing resistance against the German occupation. Frederic’s earliest knowledge of Auschwitz was therefore of a camp which interned Polish political prisoners and other opponents of the Nazi occupation.

Through his visit to Poland and conversations with his family, Frederic learnt a family narrative of Polish history which interacted with the history of the Shoah.

Déjà enfants, on nous racontait ce qui s'était passé et on est allé voir aussi le ghetto de Varsovie, là les murs de la ville. Voilà donc moi, déjà enfant, mais c'est plus par l'intermédiaire de l'histoire un peu la famille. … Et donc après chaque fois qu'on évoquait à peu l'histoire de la Pologne, c'est un petit peu l'histoire aussi de la Shoah, ce qui s'est passé en Pologne etc. Mais après, pour vraiment connaître un peu plus tiré du point de vue historique, c'est plus en tant que élève que j'ai appris un peu les régions touchées par la Shoah, les camps, comment organiser des camps d'extermination etc. C'est plus après en tant qu’élève qu'on nous donne des détails, des documents, des films etc.Footnote44

[Already as children, we were told what had happened and we went to also see the ghetto of Warsaw, the ghetto walls. So, for me, already as a child, but it was more through the intermediary of family history … And so, each time the history of Poland was talked about, there was also a little bit of the history of the Holocaust. What happened in Poland etc. But afterwards, to really know a bit more from a historical point of view, it was as a pupil that I learnt a bit about the regions affected by the Holocaust, the camps, how to organise extermination camps and so on. It is more as students that we are given details, documents, films etc.]

Frederic knew details of his uncles’ or wider family’s experience, and a narrative of their family’s suffering mediated by his grandparents. However, Frederic was too young to hear the distressing events and details of his uncles’ history from which his parents and grandparents protected him. On his visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau at the age of eight, Frederic and his brother were made to wait outside at the gate.

Frederic uncovered the history of Nazi persecution, ghettoization and murder in concentration camps in school, through the school program on Shoah education. As a result, Frederic merged the two narratives together: that of the memory of his Catholic Polish family and the history of the genocide of European Jewry that occurred predominantly in the Nazi concentration camps in Poland. His school education was able to provide some of the details of lived experience in concentration camps, much of which he applied to his Polish family. Shoah is used exclusively to refer to the Nazi genocide of European Jewry, not to other victims of the Nazi regime. Yet Frederic used the term Shoah and the history of his non-Jewish family interchangeably. When asked, he recognized the intersection of the history of Polish and Eastern European Jewry with the fate of his uncles; whilst interned for different reasons, they ultimately died in the same place. The memory of Jewish victims was stronger in France than the memory of other victim groups who died in Auschwitz as Jews were the largest racial group deported in Vichy and Occupied France. He saw no conflict in using the history of the Shoah to understand his own family’s fate beneath Nazi occupation and ideology. By affixing his memory of his Polish family to the more dominant and politically powerful memory of the destruction of European Jewry, he could validate the suffering and death of his great uncles.

Frederic was one of the only participating teachers in France who enumerated the number of Jewish victims alongside other minorities persecuted and murdered by the Nazi regime. In his interview, he referenced ‘seven million’ victims of the Holocaust rather than the figure of ‘six million’ that habitually refers to Jewish victims of the genocide. His lessons focused on the processes of genocide: the mechanics of a death camp, which helped explain his own family’s fate in Auschwitz-Birkenau, as it was clear this represented the exceptionality of Nazi evil during the war to Frederic. He said that when he taught the Shoah, he wanted his pupils to understand the extent and violence of occupation in France and elsewhere in Europe.

Qu'est-ce qu'ils ont fait, comment ils ont occupé, comment ils ont terrorisé, comment ils ont mis leur programme en route sur l'extermination des juifs … Qu'est-ce que cela veut dire quand on parle d'un génocide? Qu'est-ce que ça veut dire sept millions de … ? Après, avoir posé la question est-ce que vous vous rendez compte à quel point ça arrivait, à des proportions, des dimensions aussi grandes, cinq, six, sept, huit millions de morts etc. etc.?Footnote45

[What did they do, how did they occupy territories, how did they tyrannise, how did they implement their plan to exterminate the Jews … What does it mean when we talk about genocide? What does it mean to say seven million … ? After, having asked the question, do you realise how far it went, the proportions, to the extent of five, six, seven, eight million dead etc. etc.?]

Frederic did not specifically teach the Polish experience of Nazi occupation, which drifted too far from the school program. As a French citizen himself, he appreciated the centrality of the French experience of the Shoah in the curriculum. However, he extended his history beyond the fate of the Jews to the atrocities committed to Poles and other Eastern Europeans, intending to shock his pupils who were used to hearing only the figure ‘6 million.’ Since the end of the Cold War an increasing amount of scholarship has considered Polish antisemitism and local collaboration during the genocide.Footnote46 In addition, scholarship on the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe since the 2000s increasingly described Nazi motivations and actions as colonial, in which genocidal actions have been considered as part of a wider policy of resettlement and imperialism.Footnote47 This complex history of victimhood was absent in teaching narratives, which concentrated almost exclusively on Jewish victims of genocide, with the exception for French political internees and limited discourses about French Roma and Sinti. By merging the Shoah with the treatment of Polish citizens under Nazi German occupation, he was able to non-explicitly reactivate the memory of his family in his teaching. It rendered their memory as significant by incorporating it into the wider history of the Shoah, and through teaching the suffering endured during the Shoah he could reembody the memory of his ancestors which he could not locate elsewhere in French archives, museums, memorials and school textbooks.

Conclusion

Intergenerational transmissions of memory have the power to shape a teacher’s perspective on history and their understanding about the purpose of history education. Some, like Édouard, used these memories in their lesson to add complexity to the school curriculum by redefining simplified mythologies of ‘Frenchness.’ Hélène, on the other hand, chose not to use her family history. Hélène’s primary motivation was to maintain a separation between the public and the private and her professional and personal identity in order to be a responsible French citizen.

Where teachers were unaware of their family history, they were able to imagine their ancestors’ experiences, an activity that was enabled by their own lesson preparation and teaching and through cultural representations of their family history in film and fiction which reinforced the collective memory of the period. Their envisioned family histories could then fulfill the French imagination of wartime sacrifice and/or resistance. In some cases, teachers performed the rituals of postmemory as described by Marianne Hirsch, when, as individuals, they strove ‘to reactivate and reembody more distant political and cultural memorial structures by reinvesting them with resonant individual and familial forms of mediation and aesthetic expression.’Footnote48 By teaching history, some teachers were able to preserve their family history, whilst others were able to understand theirs through the practice of history. Where teachers were unaware of their family’s past, the curriculum could ‘assist’ by building a collective identity when trauma prohibited this happening in the family unit. Frederic was able to use the French school program to merge his family history into national collective memory of the Nazi past. This careful negotiation highlighted the significance of history teaching in shaping teachers’ perception of identity. Their confidence in the status of their family identity within the nation determined whether they were willing to publicize their history and use that to complicate a national narrative, or whether national memory could be broadened to encompass their family’s past. For teachers such as Malik, teaching the Holocaust provided an easier space to negotiate ethics and citizenship than by broaching the much less resolved history of Algerian independence.

These four teachers’ experiences are by no means representative of French teachers. Indeed, this article argues that no individual teacher can be representative of a national system of memory. It does not attempt to make generalizations about French education, but instead offers a snapshot of perspectivity and the multiplicity of memory within one community of history educators.

Research as shown that history textbooks create and promote particular national and ethnic loyalties and play an important role in the development of the specific forms and meanings of those identities.Footnote49 At the same time, teachers are not neutral transmitters of the past, but individuals with agency, pasts, families, ethnic and religious identities, political views, interests, training and careers, that all define their identities in different ways. They often have the power to enhance, support or subvert the knowledge present in curricula, textbooks and national memory. As articulated by Young (Citation1971), every educational act is a social activity of selection and organization, deliberately or unconsciously constructed out of available knowledge in a specific time.Footnote50 Teachers have agency in deciding whose knowledge counts and what knowledge is valuable. Every educational decision is therefore inherently ideological.Footnote51

It is, therefore, important for teachers to reflect upon the purposes of teaching the history of a particular topic or event, and whether the purpose is universal or particular, and public or personal. Likewise, both educational research and teacher training may benefit from reflecting further on the relationship between teaching and remembering and memory.Footnote52 Whilst dynamic and valuable teacher exchanges are facilitated by networks such as EuroClio, international in-service and pre-service teacher training remains the exception rather than the rule. The demands on teachers’ attention are already immense, but as multi-perspectivity is already a central tenant and objective of history education, it may be wise for teachers to develop greater self-knowledge about their motivations as history educators, particularly when teaching topics imbued with civic and moral lessons. Only by reflecting on how these differ from our colleagues, both locally and nationally, can teachers assess how their selfhood shapes how they teach the Holocaust and other histories, both consciously and unconsciously.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Heather Mann

Heather Mann has a DPhil in History from the University of Oxford, specialising in the relationship between teachers' memory of the Holocaust and teaching practice in England and France. Heather worked as a lecturer and outreach consultant at the Parkes Institute for the study of Jewish/non-Jewish relations at the University of Southampton, where she organised training courses for teachers on subjects relating to the Holocaust. Alongside her PhD, Heather is interested the dynamics of conflict and identity in history education. Heather has a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (secondary education) and previously worked as a teacher in schools in England and Germany.

Notes

1 See Gross and Stevick, “Epistemological Aspects of Holocaust Education,” 489–504.

2 See Meseth and Proske, “Mind the Gap: Holocaust Education in Germany,” 159–83.

3 See Proske, “‘Why Do We Always have to Say We're Sorry?’,” 39–66; Lohl, “‘Totally Average Families’?,” 33–48.

4 Anderson, Imagined Communities, 71.

5 Ibid., 197.

6 Apple, Ideology and Curriculum.

7 Gross and Stevick, “Epistemological Aspects of Holocaust Education,” 489–504.

8 Worden, National Identity and Educational Reform, 3, 80–1.

9 Assmann, “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity,” 125–33; Hirsch, “The Generation of Postmemory,” 111.

10 See Gross, “No Longer Estranged,” 131–49; Morgan, “Is It Possible to Understand the Holocaust?,” 441–63.

11 Apple, “Theory, Research and the Critical Scholar Activist. Educational Researcher,” 152; Worden, National Identity and Educational Reform, 80–1.

12 Édouard, Interview.

13 Édouard, Interview.

14 See Blanchard and Bodineau, Histoire Géographie 3e, 39.

15 Édouard, Interview.

16 Union Juive française pour la paix, “Le sionisme m’a quitter.”

17 Édouard, Interview.

18 Hirsch, “The Generation of Postmemory,” 111.

19 Édouard, Interview.

20 Édouard, Interview.

21 Hirsch, “The Generation of Postmemory,” 104.

22 Assmann, “Re-Framing Memory,” 36.

23 Those of French and other European origin who were born in Algeria during the period of French rule from 1830 to 1962. The majority of pieds-noirs departed Algeria for France upon Algerian independence. By 1962, the Jews of Algeria were considered as part of the Pied-Noir community.

24 Hélène, Interview.

25 Abitbol, The Jews of North Africa, 86–8.

26 Choi, “Complex Compatriots,” 863–80.

27 Hélène, Interview.

28 Eldridge, From Empire to Exile, 239–41.

29 Stora, Imaginaires de guerre, 190.

30 Liauzu et al., “Colonisation: non à l’enseignement d’une histoire officielle,” 15.

31 Hélène, Interview.

32 Finkielkraut, “Répliques: Le destin de la République.”

33 Finkielkraut, Au nom de l’autre, 10.

34 Pratt, Imperial Eyes, 34.

35 Vandrick, “The Role of Hidden Identities in the Postsecondary ESL Classroom,” 153–57.

36 Malik, Interview.

37 Malik, Interview.

38 Malik, Interview.

39 Malik, Interview.

40 For discussions problematizing laïcité in France see Leschi, Misère(s) de l'islam de France; Portier, L'État et les religions en France.

41 Malik, Interview.

42 Malik, Interview.

43 Frederic, Interview.

44 Frederic, Interview.

45 Frederic, Interview.

46 Gutman and Krakowski, Unequal Victims; Gross, Neighbors; Polonsky, The Neighbors Respond.

47 Furber, “Near as Far in the Colonies,” 541–79; Zimmerer, “Holocauste et colonialisme,” 213–46.

48 Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory, 33.

49 Korostelina, “History Education and Social Identity,” 25–45.

50 Young, “An Approach to the Study of Curricula,” 19–46.

51 Apple, Ideology and Curriculum.

52 Paulson et al., “Education as a Site of Memory,” 429–51.

Bibliography

- Abitbol, Michel. The Jews of North Africa During the Second World War. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989.

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 2016.

- Apple, Michael. Ideology and Curriculum. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Apple, Michael. “Theory, Research and the Critical Scholar Activist.” Educational Researcher 39, no. 2 (2010): 152–155.

- Assmann, Aleida. “Re-Framing Memory. Between Individual and Collective Forms.” In Performing the Past: Memory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe of Constructing the Past, edited by Karin Tilmans, Frank van Vree, and Jay Winter, 35–50. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

- Assmann, Jay. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique 65 (1995): 125–133.

- Blanchard, Françoise, and Jacques Bodineau. Histoire géographie : 3e, découverte professionnelle. Vanves: Foucher, 2007.

- Choi, Sung. “Complex Compatriots: Jews in Post-Vichy French Algeria.” North African Studies 17, no. 5 (2012): 863–880.

- Eldridge, Claire. From Empire to Exile: History and Memory Within the Pied-Noir and Harki Communities, 1962–2012. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017.

- Finkielkraut, Alain. “Répliques: Le destin de la République.” France Culture, October 14, 2000.

- Finkielkraut, Alain. Au nom de l’autre: réflexions sur l’antisémitisme qui vient. Paris: Gallimard, 2003.

- Furber, David. “Near as Far in the Colonies: The Nazi Occupation of Poland.” The International History Review 26, no. 3 (2004): 541–579.

- Gross, Jan. Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Gross, Magdalena. “No Longer Estranged: Learning to Teach the Holocaust in Poland.” Holocaust Studies 24, no. 2 (2018): 131–149.

- Gross, Zehavit, and Doyle Stevick. “Epistemological Aspects of Holocaust Education: Between Ideologies and Interpretations.” In As the Witnesses Fall Silent: 21st Century Holocaust Education in Curriculum, Policy and Practice, edited by Zehavit Gross and Doyle Stevick, 489–504. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Gutman, Yisrael, and Shmuel Krakowski. Unequal Victims: Poles and Jews During World War Two. Washington, DC: Holocaust Pubns, 1988.

- Hirsch, Marianne. “The Generation of Postmemory.” Poetics Today 29, no. 1 (2008): 103–128.

- Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Colombia University Press, 2012.

- Korostelina, Karina. “History Education and Social Identity.” Identity 8, no. 1 (2008): 25–45.

- Leschi, Didier. Misère (s) de l'islam de France. Paris: Cerf, 2017.

- Liauzu, Claude, Gilbert Meynier, Gérard Noiriel, Frédéric Régent, Trinh Van Thao, and Lucette Valensi. “Colonisation: non à l’enseignement d’une histoire officielle.” Le Monde, March 25, 2005.

- Lohl, Jan. “Totally Average Families’? Thoughts on the Emotional Dimension in the Intergenerational Transmission of Perspectives on National Socialism.” In Peripheral Memories. Public and Private Forms of Experiencing and Narrating the Past, edited by Elisabeth Boesen, Fabienne Lentz, Michel Margue, Denis Scuto, and Renée Wagener, 33–48. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2012.

- Meseth, Wolfgang, and Matthias Proske. “Mind the Gap: Holocaust Education in Germany, Between Pedagogical Intentions and Classroom Interactions.” In As the Witnesses Fall Silent: 21st Century Holocaust Education in Curriculum, Policy and Practice, edited by Zehavit Gross, and Doyle Stevick, 159–183. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Morgan, Katalin. “Is it Possible to Understand the Holocaust? Insights from Some German School Contexts.” Holocaust Studies 23, no. 4 (2017): 441–463.

- Paulson, Julia, Nelson Abiti, Julian Bermeo Osorio, Carlos Arturo Charria Hernández, Duong Keo, Peter Manning, Lizzi O. Milligan, et al. “Education as Site of Memory: Developing a Research Agenda.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 29, no. 4 (2020): 429–451.

- Polonsky, Antony. The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy Over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Portier, Phillipe. L'État et les religions en France: une sociologie historique de la laïcité. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2016.

- Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Proske, Mattias. “‘Why Do We Always Have to Say We're Sorry?’: A Case Study on Navigating Moral Expectations in Classroom Communication on National Socialism and the Holocaust in Germany.” European Education 44, no. 2 (2012): 39–66.

- Stora, Benjamin. Imaginaires de guerre: les images dans les guerres d’Algérie et du Vîetnam. Paris: Marval, 2004.

- Union Juive française pour la paix. “Le sionisme m’a quitter.” October 25, 2018. http://www.ujfp.org/spip.php?article6235.

- Vandrick, Stephanie. “The Role of Hidden Identities in the Postsecondary ESL Classroom.” Tesol Quart 31 (1997): 153–157.

- Worden, Elizabeth. National Identity and Educational Reform: Contested Classrooms. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Young, Michael F. D. “An Approach to the Study of Curricula as Socially Organised Knowledge.” In Knowledge and Control: New Directions for the Sociology of Education, edited by Michael F. D. Young, 19–46. London: Collier-Macmillan, 1971.

- Zimmerer, Jürgen. “Holocauste et colonialisme. Contribution à une archéologie de la pensée génocidaire.” Revue d'histoire de la Shoah 189, no. 2 (2008): 213–246.

Interviews

- Interview with Édouard, Conducted by H. Mann, Marseille, 23 May 2018, in Author’s Possession.

- Interview with Frederic, Conducted by H. Mann, Aix-en-Provence, 31 May 2018, in Author’s Possession.

- Interview with Hélène, Conducted by H. Mann, Marseille, 27 June 2018, in Author’s Possession.

- Interview with Malik, Conducted by H. Mann, Marseille, 19 June 2018, in Author’s Possession.