ABSTRACT

This essay examines two shoe soles cut from a Torah scroll which British historian and collector of Judaica Cecil Roth collected in Greece in 1946. As Holocaust relics, the Torah scroll shoe soles are, in turn, sacred and sacrilegious, texts and objects, Greek Jewish and non-Jewish Greek artifacts. Roth’s recovery of the shoe soles is compromised by occurring under the auspices of the British Army during the Greek Civil War and in the controversial climate of collecting Judaica displaced by the Holocaust. I discuss the ongoing story of the shoe soles: their separation, their use, and their best location.

In July 1946, the British historian Cecil Roth made his only trip to Greece, part of a tour that he found included Salonica.Footnote1 From this tour Roth – who was co-founder, in 1932, of the London Jewish Museum and arguably one of the most important twentieth-century collectors of Judaica – brought back a single item, or rather a pair of items. He refers to these in an essay published some four years after his visit, his most substantial publication resulting from his Greek tour, ‘The Last Days of Jewish Salonica: What Happened to a 450-Year-Old Civilization.’Footnote2 The objects appear in a list that Roth recounts at the end of his essay in order to exemplify the devastation of Jewish life that confronted him in post-Holocaust Salonica, evidence of Jewish Salonica’s ‘last days’:

In the synagogue, on Sabbath morning, there was barely a minyan. There was as yet no religious education for the children. There was hardly any provision for other fundamental religious requirements. Everywhere one could see traces of loot. I found a child in the street sitting on a synagogue chair carved with a Hebrew inscription; I was given a fragment of a Sefer Torah [Torah scroll] which had been cut up as soles for a pair of shoes; I saw carts in the cemetery removing Hebrew tombstones, on the instructions of the Director of Antiquities for the province, for the repair of one of the local ancient churches. But a Greek hawker in the street was selling eggs cooked in the traditional Sephardic sabbatical fashion, huevos enjaminados [baked eggs] now become a local delicacy. Jewish life had been all but exterminated, but this relic of the Jewish cuisine curiously survived.Footnote3

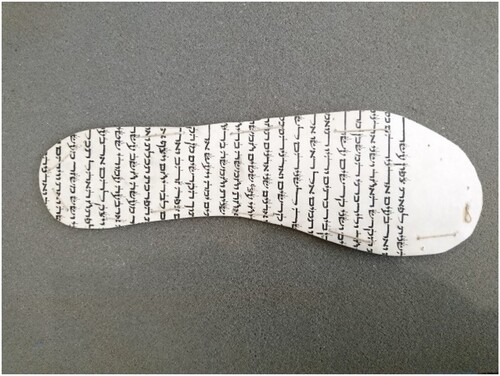

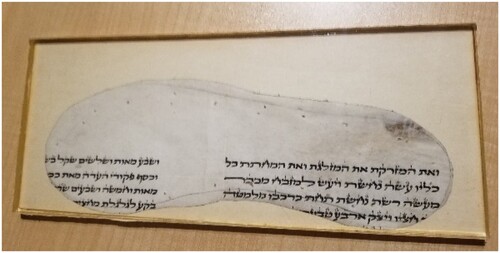

The only portables and nonperishables in this list, the Sefer Torah shoe soles are the items that Roth collects and brings back to the UK, first presumably to Oxford, where Roth lived and was Reader in Post-Biblical Jewish Studies at the University of Oxford from 1939 to 1964. Since Roth sold his collection in the mid-1960s, the soles have been kept in different Roth Collections, on either side of the Atlantic. The left sole has been held in Special Collections at the University of Leeds Library, UK ().Footnote4 The right sole has been held in the Reuben & Helene Dennis Museum at Beth Tzedec in Toronto, Canada ().Footnote5 Beth Tzedec’s collection has now been purchased by the Royal Ontario Museum but has not yet been moved.Footnote6 The right sole is, as of this writing, therefore unviewable. The goal of this essay is to tell the story of these previously unexamined remnants of the Holocaust.Footnote7 Attending to what has been called ‘the cultural biography of things,’ I want to reconstruct the narrative of their making, examine their changing use, and address their cultural meanings.Footnote8 My methodology entails description, textual and object analysis, interpretation, and comparison with other Sefer Torah fragments resulting from the Holocaust. I hope to make a case for Roth’s Sefer Torah shoe soles as extraordinary among what I am going to classify as Holocaust relics.

This essay therefore seeks to further exploration of Holocaust relics. Roth’s term relic at the end of his list, even while its referent is street food, is nevertheless helpful for categorizing the shoe soles and prompting theorizing of relics. Although research on Jewish and Holocaust relics is growing, relic studies have been mostly pre-nineteenth century and largely without Jewish content.Footnote9 Indeed Oren Baruch Stier argues that, due to its dominant associations with the bodily remains of saints, the concept of a Jewish relic is ‘something of an oxymoron.’Footnote10 In Holocaust studies, the term relic has been used variously, mostly denoting testimony, but also encompassing concentration camps, Holocaust pilgrimages, bodily and other remains, and even survivors.Footnote11 In these cases relics often exceed any material objects such as the Sefer Torah soles. As survivors die and we lose direct access to their testimony, Holocaust objects increase in value as testimony and demand specific attention. Although she does not explicitly theorize relics, Bożena Shallcross identifies objects as the Holocaust’s ‘metonymy, which allows these fragments to speak on behalf of a past wholeness.’Footnote12 Laura Levitt also explores the power of objects as evidence of past crimes in her work connecting ‘objects that remain’ from the Holocaust with those from other atrocities.Footnote13 Embracing the term relic unlike Shallcross, Levitt thinks innovatively about the sacredness of ordinary objects. However, as in other work on Holocaust relics, Levitt does not write about relics stricto sensu. Instead, she identifies relics as phenomenologically constructed objects: it is ‘[o]ur attention to these kinds of tainted objects [that] makes them holy.’Footnote14 In research on Holocaust relics to date, relics tend to be items that are made sacred in their promotion of Holocaust memories.

If existing research does not distinguish relics among Holocaust texts or objects and instead assumes many objects (and places and people) associated with the Holocaust as sacred, I pinpoint desacralization of the sacred as key to a specific object’s process of becoming a relic. It is this narrative of becoming relic, from sacred to profane to sacred again, that I seek to contribute to work on Jewish and Holocaust relics. As in Roth’s list, relics are produced in destruction, material violently severed from Jewish wholeness and, in the truest sense of the term relic, Jewish holiness. Relics are objects of memory that bear distinct ties to the sacred and to the dialectic of destruction-collection. With the Sefer Torah the only sacred object in Jewish worship, Roth’s shoe sole fragments constitute an arch-relic, a heightening or literalization of the category of relic, and thus provide optimum material for my argument. The shoe soles encapsulate paradoxical processes and states that make an object a relic. They are at once sacred sacrilege, the result of destruction and salvage, abandonment and collection, forgetting and memory, functioning both as a Jewish text and a non-Jewish object. Because of the destruction necessary in the production of the relic, a relic will never provide full testimony. But it is this elision at the heart of the material object that draws me to attempt to reconstruct the story of the Sefer Torah soles, which I do in the first part of this essay.

That story here is only made possible by Roth as a collector, since collections and the artifacts they hold are the creation of a personality, their views, historical and geographical context, and so on. Roth collected the Sefer Torah shoe soles at a time immediately after the Holocaust when there were fierce debates about the practicalities and significance of collecting items displaced by the Holocaust. Situating Roth in this context, in part two of this essay I discuss the political, ethical, and cultural significance of Roth’s collection of the shoe soles. His act is made more complex by the fact that Roth traveled to Greece with the British Army during the Greek Civil War, and that this was a war in which Britain was enmeshed and partial. In the third part of this essay, I address the afterlife of the Sefer Torah shoe soles. I discuss Roth’s use of them, how the shoe soles might have come to be separated, and what their future biography might entail.

Sacred sacrilege: the paradoxical making of Holocaust Relics

Roth’s shoe soles take their place in a larger story of Sifrei Torah (Torah scrolls) desecrated as part of the Holocaust. Damaged scrolls, or their remnants, are held by Holocaust museums such as at Yad Vashem, Jerusalem; the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Washington; and the Holocaust Galleries at the Imperial War Museum, London. When displayed, their function is to metonymize the desecration of Judaism involved in cultural genocide that, since Raphael Lemkin’s coining of the term genocide in 1944, was recognized as an intrinsic part of the Holocaust.Footnote15 Scrolls faced a number of possible different fates. Fire, bomb, or other damage destroyed some completely. Many were stolen from synagogues to be transported to the Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question in Frankfurt, the antisemitic center for holding and debasing Jewish culture.Footnote16 The fortunate ones were stored and restored after the war. Most famous among these are the Czech Scrolls, the 1600 scrolls uprooted from synagogues across Bohemia and Moravia, which were held in the Jewish Museum in Prague during the war, then in an abandoned synagogue outside of Prague. In 1964 they were rescued and brought to Westminster Synagogue in London.Footnote17 They are now lent to Jewish communities around the world. A short drive from the University of Leeds Roth Sefer Torah sole, the York Liberal Jewish Community (my own Jewish community) holds and uses one of these Czech scrolls in our services.Footnote18 Our knowledge of its history and the signs of its repair make us additionally careful with the scroll. For some of us, its story increases the scroll’s sacred quality and any reverence we bear toward it.

Other scrolls, such as the one we find left over in Roth’s shoe soles, were stolen by the Nazis or local populations to provide material for new goods. In accordance with halacha (Jewish religious law), the parchment of Sifrei Torah is kosher animal skin and most often calf. Yad Vashem holds a number of leather goods ‘recycled’ from desecrated scrolls, including a handbag, a toy drum, and a wallet.Footnote19 Yad Vashem also holds three shoe soles which are the Sefer Torah fragments most comparable to Roth’s: one pair of insoles found in the shoes of a German officer in Italy; plus a single sole without any known provenance or history.Footnote20 Only in the case of Roth’s Sefer Torah soles can we know the collector, the year, as well as the country of collection. Only with these soles can we reconstruct most of the story involving collection.

Roth’s Sefer Torah soles have a specific object biography, although Roth himself tells us no more about the soles in his writings than I have quoted. Notably the Torah scroll that forms their material was not taken by the Nazis for their institute in Frankfurt but left in Greece. The Nazis’ plundering agency, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, had been active in Greece since 1941.Footnote21 Yet the agency clearly did not consider the scroll of sufficient value for the Frankfurt institute. This oversight begins the poignant and troubling transformation of the scroll into a pair of soles. The looting of the scroll is likely to have occurred after the deportation of Greece’s Jews, the overwhelming majority of whom were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943–44. At 84%, the death toll of Greek Jews was one of the highest in the Holocaust, an event that entailed ‘not only mass murder and looting but also the obliteration of a unique centuries-old cultural and historical heritage.’Footnote22 The largest Greek Jewish community was in Salonica, known before the war as the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans,’ from which 50,000 were deported.Footnote23 The numbers involved, along with the cultural symbolism of Salonica for Sephardi Jews, has led to the repeated claim by Salonica’s historians that ‘the almost total annihilation of Salonica’s Jews during the Holocaust was an unprecedented catastrophe.’Footnote24 The shoe soles are remnants of this near annihilation of Sephardi Jewry in Southern Europe. They are relics that stand out as emerging beyond the concentration camps and killing fields of Greater Germany as more usual in the literature on Holocaust relics.

Wherever it took place, the confiscation of Jewish archives and plundering of relics needs to be understood as parallel to the appropriation and despoliation of Jewish domestic and commercial property. Both archival and property plunder were in turn parallel, and in some cases prefatory and preparatory, to the deportation and killing of Jews. In Greece, Jewish property was officially handed to the Greek state in 1943. On March 30, ‘just two weeks after the first train had left for Auschwitz,’ the Service for the Custody of Jewish Properties and Land Registry Office of the Greek Ministry of Finance began evaluating Jewish shops and merchandise for use, in part by ethnic Greek refugees fleeing East Macedonia and Thrace.Footnote25 Yet there was also general looting and despoliation by non-Jews.Footnote26 Plundering of property and deracination of people intertwined, sometimes in powerful symbolism with a Torah scroll trodden underfoot. For example, in his testimony for the USC Visual History Archive, Dan Saporta recounts how, when the heads of the families of Spanish citizenship were ordered to present at Beth Saul synagogue in Salonica, they stepped on rubble and pieces of Sefer Torah.Footnote27

In his account of the Nazi occupation of Salonica, which details confiscation of homes and contents such as radios and pianos, Auschwitz survivor Albert Menasche apportions blame squarely to the Germans.Footnote28 This is likely because, in this first memoir of the Holocaust by a Salonican Jew, the focus is on Auschwitz, and Menasche’s experiences in Salonica amount to only a few pages. However, the fact that destruction of Jewish property continued even after survivors started to return, well after the war, shows an ongoing Greek interest in erasing Jewish memory, most famously evidenced in relation to the cemetery in Salonica.Footnote29 The acquisition and destruction of property was therefore not an inadvertent effect but rather an ideological enactment of the absence of Greek Jews. The destruction of a Jewish religious object, such as a headstone or a Sefer Torah, can be seen as a dramatic materialization of the Christian antisemitism that Katherine Fleming identifies in non-Jewish Greek acquisition of Greek Jewish property during and after the war.Footnote30

With the proviso that the reprocessing of Jewish objects continued well after the liberation of Salonica from the Germans in 1944, the transformation of the scroll into soles indicates the material conditions of Greece under and following Nazi rule. The existence of the soles tells us about scarcity of leather and the difficulty of acquiring shoes. A report on conditions in Nazi-occupied Greece by British intelligence operating in Greece, produced in August 1943 just a month after the Salonica deportations had been completed, notes the exorbitant price of goods and specifies shoes.Footnote31 The cost of shoes is used as a measure of deprivation. The Bishop of Karystia told the intelligence officer that his salary was so poor that it ‘wouldn’t buy me a decent pair of shoes.’Footnote32 It cannot have helped that before deportation many of the cobblers seem likely to have been Jewish. We know that even before the deportations were completed, when in Salonica Jews were confined to ghettoes, beginning March 1943, shoes could no longer be repaired.Footnote33 We also know how – and perhaps a bit more why – even before Jewish citizens had been deported, their non-Jewish neighbors rushed to abandoned Jewish houses and shops and synagogues, looking for useful as well as valuable goods. Jewish objects were given, what has been called in an East European context, a ‘second life.’Footnote34 That term is ironic in the case of the Sefer Torah soles since the scroll had to be destroyed for the production of the second-life soles; they were not simply stolen objects. The scroll-turned-into-soles encapsulates the dialectic of destruction-production in the relic, a concrete symbol of how non-Jewish lives thrived in the destruction of Jewish life in Greece. Where a Jewish artifact was placed under erasure, a Greek object was born. The shoe soles thus speak profoundly of the disregard of some remaining non-Jewish Greeks for the deported Jews and for Jewish culture.

More than other items made from Sifrei Torah such as the drum or the handbag held by Yad Vashem, the soles encapsulate embodiment, heightening, as parts of shoes, the physical quality of memory inherent in all objects.Footnote35 They were meant to be worn by a body, to help support a body. They were not intended as insoles like those in Yad Vashem found in the boots of a German officer, but rather as the soles of shoes in touch with the ground, their function essential rather than for comfort. The soles are much paler than those held by Yad Vashem. This suggests they have not been worn. The Roth shoe soles are also different from each other: that in the Leeds Roth Collection consists of two pieces of Torah parchment, one layered on top of the other, clearly to create a thicker sole. That in the Toronto Roth Collection is single layered, more roughly cut, slightly wider, and with holes intended for, but without the actual, stitching. This indicates that even as soles they are unfinished. Finally, the Roth Sefer Torah soles measure 76 millimeters by 247 millimeters. These are soles for a very small man, a woman, or more likely, I think, a large child. They were not worn by a German soldier but intended for (and yet never worn by) a non-Jewish Greek.

Figure 2. Strips of Pentateuchal scroll cut into shape by a cobbler. Cecil Roth Collection. Beth Tzedec Museum. Toronto.

As tangible objects, especially when they can be held, relics have the power to touch us. As Levitt it puts it so well in her work on contemporary relics, as we hold them, tend to them, relics in turn offer us tenderness.Footnote36 In relation to the Holocaust and other traumatic memories, Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer have likewise identified how ‘testimonial objects’ can endow memory with embodied qualities and affective powers.Footnote37 As Hirsch writes, ‘Ordinary objects mediate the memory … through the particular embodied practices that they reelicit. And these embodied practices can also revive the affect of the past.’Footnote38 Both Hirsch and Levitt draw on the lexis of affect to describe our experience of such objects; Levitt writes about the ‘affective energy’ of contemporary relics.Footnote39 The vocabulary of affect underlines how the immediate effect of our coming into contact with a memory object is a feeling. This is corporeal: we can feel the Sefer Torah soles in three dimensions as we do not a written text or a photograph, and in this physical contact we can be burdened by the weight of the past they remember.

What is the affect of Roth’s shoe soles? The size and physical quality of relics, especially when one comes into tactile proximity with them, amplify their affective power. One of the several paradoxes of relics is that their capacity for inspiring awe typically exists in inverse relation to their size. Minuteness of kept objects increases their sublime effect.Footnote40 That the soles are small adds to their poignancy, the sad and searing feeling they induce of vulnerability, innocence, and inexplicable loss in the face of massive destruction. Moreover, knowing what happened to probably almost all of those who had been called to the bimah (raised platform in the synagogue) to read this passage and indeed from this very Sefer Torah, their annihilation feels individualized, physical, and embodied. Holding the soles raises questions that cannot be definitely answered. Why were the shoes not finished? Were the soles intended for a specific person? What happened to the intended wearer? And as not worn, to what end was the Sefer Torah destroyed? As still soles rather than shoes, the relics never became part of a shoe, although very likely other parts of Sifrei Torah (this one included?) did. We are unlikely ever to know of them, but holding the existing soles can lead our thoughts both inwards to the object’s intimacy and outwards to its symbolism.

Thus, particularly as we do not know which synagogue the Sefer Torah came from, while they are specific the soles also evoke the relic’s register of collective memory, another paradoxical quality of relics. Holding the soles, I cannot help but wonder how many other soles were created from, and how many non-Jewish Greeks walked around during and after the war on, fragments of the Torah of the Jews who had been deported and incinerated; the Jews who had walked to the bimah and stood and read from such scrolls and who previously had been these sole-wearers’ neighbors. After the execution of Jewish life, the redeployment of this sacred object of Jews for everyday-life use by those who had witnessed, had not protested, nor sought to stop their deportation, but who themselves needed to work and shoes to walk, speaks volumes. Our feelings and thoughts move quickly back and forth between the small and the specific and the very big and collective, and between Jews and the non-Jewish Greeks. These small fragments, initially from sacred Jewish memory (the Torah), in their new form come to tell us about transcultural relations between Greeks and Jews in the Holocaust. The meaning of the relic grows in its circulation. The object crosses a religious and cultural border, a Jewish text (and object) made into a Greek object with the Jewish text placed under erasure but still readable.

To return to them as memory objects according to Hirsch’s definition, the Torah scroll shoe soles reveal two embodied practices that might be considered ‘ordinary’: walking and reading.Footnote41 As soles, they were to be walked upon; as a scroll, to be read aloud from before a congregation, eyes and a yad (pointer – literally, a hand, an extension of the body) following the text on the scroll. The reading of the Torah in a synagogue reveals to what extent, as Laura Leibman has noted in her work on Jewish material culture, ‘Jewishness [is] an embodied experience: how Jewish ritual life constantly engages the body.’Footnote42 As the body must never actually touch the scroll, however, that embodiment when it comes to reading is symbolic; hence the yad, the symbolic hand.

Derived from a Sefer Torah, the soles are not simply ordinary objects. A quality that relics have additional to other memory objects discussed by Hirsch and Shallcross is that the former pertain as much to recurrent patterns of religious cultural memory as they belong to a single fixed point in secular history. While their embodiedness situates them at a specific historical and geographical juncture, the Sefer Torah soles travel in time and place and indeed away from the secular. Their larger symbolic story is about sacred memory. Ordinary objects as parts of a shoe, the soles are extraordinary in their composition. Objects that can be touched and texts that can be read, the soles accrete further paradoxical qualities: the ordinary and the extraordinary, historical specificity and transhistorical recurrence, the severing of Jewish memory and its persistence, the sacred and the secular.

As part of a Sefer Torah, even before it was cut to pieces, both soles were already part of a relic and would have been regarded as extraordinary by those who used it. According to rabbinic tradition, the Torah, whether in a scroll or a book, is a relic of God’s words to Moses; the relic of a relic, the Sefer Torah is therefore the most venerated object in Judaism, holy text embodied as holy object.Footnote43 As Roth wrote before his visit to Greece in a catalogue to mark the opening of the Jewish Museum in London, ‘The central object in synagogal worship is the Scroll of the Law.’Footnote44

In the case of Roth’s Greek Sefer Torah fragments, the Hebrew script is very much still readable. The left sole at Leeds, which is two-ply, has a palimpsestic quality, although without a second readable text it is not a genuine palimpsest. The excerpt captured on the left sole comes from parashah (Torah portion) Va-Yakhel (‘he collected’ or ‘he gathered’).Footnote45 The right sole in Toronto continues directly from the same parashah and includes some of the subsequent parashah, Pekudei (‘records’ or ‘accounts’).Footnote46 The passages describe the building of the mishkan (the ark or tabernacle) during the exile of the Israelites in the wilderness. These are the very parashot that should have been read on the successive two shabbats prior to the deportations from Salonica in March 1943. It is uncanny for this account of construction of a dwelling for the sacred in exile only itself to be desecrated and taken apart at a subsequent time when Jews had been deported from another home and for the text on the fragments to record an ancient template of such events. This recurrence makes the Sefer Torah soles relics simultaneously of Greek Jewry in the Holocaust and of collective Jewish memory. The scroll soles incorporate two catastrophes: that in exile in the Torah; that in Salonica and Greece in 1943–44. In their sacred quality, Jewish relics are thus evocative of Zakhor, as defined by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi.Footnote47 Memory and its destruction are redoubled, as layered as at least one sole. Their size also concentrates the reader on the Torah portions, laden with so much symbolism. The names of the parashot – and ‘he collected’ and ‘records’ – also uncannily chime with Roth’s collection of the soles.

The scroll soles occupy that network of paradoxes at which the relic centers. To be made into the shoe soles, the scroll could no longer be regarded as sacred. Equally and inextricably, it could no longer be understood as the continuing historic property of the Jewish people. These double connotative ties of the scroll to the sacred and to Jewish memory were cut along with the physical cutting-up of the scroll into soles. Yet if it was the destruction of the scroll that allowed the Sefer Torah to form soles, Roth’s collection of them as records recognizes the Sefer Torah soles as valuable and extraordinary in their new form. Knowledge of a relic’s biography – first from sacralization to desacralization; second from discovered relic to collection – can increase what we might call, after Walter Benjamin, another kind of collector and a contemporary of Roth, the ‘aura’ of the artifact: that is, its authenticity and exceptionality.Footnote48 The scroll soles certainly have auratic power, and Roth’s part in their ongoing biography indicates that he knew that.

He gathered … Records: Roth’s complex collecting

What was the significance of Roth’s collecting? How did Roth’s collecting of the Sefer Torah soles fit into the narrative of both his own collecting and collecting broadly during and immediately after the Second World War?

As a major collector of Judaica, Roth had a sustained relationship with relics. His obituary in Commentary noted that, while his contribution to Jewish history was considerable, ‘his warmest and most infectious enthusiasm arose out of his extraordinary talent as a collector – of books and manuscripts, drawings and paintings, regalia and bibelots.’Footnote49 Roth had a passion for such objects. In his introduction to the handlist for his collection of manuscripts in the University of Leeds Library, Roth speaks of the ‘romance’ and ‘imbecilic joy’ he experiences in collecting.Footnote50 Irene Roth’s memoir of her husband depicts Roth’s collecting as lifelong and driven, often occurring alongside her or in conversation with her.Footnote51 The Roths made many purchases, and they were given many items, which made their way into the collection. While there is a difference in degrees of activity and passivity between acquisition and receipt, according to Irene Roth’s memoir and Roth’s handlist to his collection, the Roths do not seem to have used this criterion to distinguish parts of their collection in their home or to attribute value.Footnote52 In any case, even while he writes in his Commentary essay that he was given them, Roth’s transporting the soles from Greece and preserving them within his collection amounts to collection. Yet the Sefer Torah soles stand out among the items Roth usually collected. Roth’s collections are overwhelmingly pre-twentieth century. Unlike many of his treasures such as a sixteenth-century kabbalistic scroll, an eighteenth-century illuminated ketubah (marriage contract), and a seventeenth-century prayer book in Judeo-Italian for a time of plague, it is not the age, the beauty, or evidence of Jewish vitality or creativity that makes the Sefer Torah soles collectible for Roth, but rather the evidence they provide of recent historical destruction.Footnote53

Roth played a significant role in the project to collect Jewish artifacts during World War II, as is starting to be established.Footnote54 Very early, he grasped how collecting was both an instrument of and could yet be a form of resistance to cultural genocide, and also how the rescue of Jewish objects, manuscripts, books, and archives from Nazi Europe was analogous to the rescue of refugees. Roth’s early commitment to archival rescue is most evident in April 1943, at the conference on Restoration of Continental Jewish Museums, Libraries and Archives, hosted by the Jewish Historical Society of England (JHSE). In his address as the JHSE’s president, Roth focused on the Nazi destruction of Jewish culture and the necessity for collection as a response:

Nazi assault during the past ten, and especially during the past three, years has been directed not only against the Jews but also against spiritual and intellectual values. Parallel, therefore, to the attempt at exterminating our coreligionists on the Continent of Europe there has been developed an attempt to destroy, or else pervert, every monument of Jewish culture, every evidence of Jewish antiquity, and every object of Jewish art.Footnote55

Roth points out the paradox that Nazis ‘are among the very few persons in the world who take Jewish scholarship seriously’ (along with ‘rabbis or eccentrics’), that Nazis are also engaged in ‘Jewish studies.’Footnote56 While there was then no single comprehensive Jewish library in Britain, the US, or Palestine, there existed, Roth thought at the time in Munich, the ‘Institute of the Study of the Jewish Question’: ‘without doubt the greatest Jewish collection the world to-day. Here, so far as can be ascertained, have been concentrated the choicest contents of all great Jewish libraries on the Continent of Europe.’Footnote57

Roth suggests the JHSE, ‘the only Jewish scientific body now left in Europe,’ as the intellectual counter to the Munich Institute.Footnote58 With a limited budget of £50 a year available to the Jewish Museum in London, Roth states he is unable to travel to Europe during the war. He argues that Jewish objects stolen from owners who cannot be traced or from communities unlikely to revive should be held by Hebrew University in Jerusalem, in ‘custody,’ since ‘there is the possibility that institutions which now seem to be dead may ultimately be revived’ in Europe.Footnote59 His address has a messianic tone, as he reminds his audience that, in the past, the rescue of Jewish books was considered ‘an integral part of the fundamental Mitzvah of Pidion Shevuim, the Redemption of Captives.’Footnote60 Immediately following the conference, Roth set up in 1943 the Committee for the Restoration of Continental Jewish Museums, Libraries and Archives. Roth’s was the first organization seeking to preserve Jewish collections from the Nazis, established before organizations which would become more well known, in New York and Jerusalem.Footnote61

Over ten years later, Roth extends his idea of the parallels and paradoxes in the Nazi interest in collecting Jewish archives.Footnote62 He remarks that the Nazis ‘showed a somewhat paradoxical interest in Jewish libraries, intellectual treasures, and ritual objects’ in their program to build ‘the world’s greatest Jewish research library,’ eventually located in Frankfurt.Footnote63 The Nazis were in effect ‘perverted collectors,’ since they wanted the artifacts ‘for anti-Semitic’ purposes, not as vehicles of remembrance of a people but of their destruction, since they wanted the things having destroyed people.Footnote64

It is not coincidental that Roth returns to the paradoxes of relics in this, his fullest writing on Salonica. For as Roth notes, ‘(t)he ancient fame of Salonica attracted special attention; and not long after the German occupation a section of the Kommando Rosenberg [ensured that a]ll the libraries and synagogues of Salonica were now raided and their treasures seized, packed, and dispatched northward.’Footnote65 The Nazis’ chief ideologue, Alfred Rosenberg was empowered by Hitler to seize ‘all scientific and archival materials of the ideological foe … for a new institution in Frankfurt to educate the German people about Jews.’Footnote66 A week after securing the Greek mainland, Rosenberg’s Sonderkommando set about removing Jewish archives, collections, and religious artifacts from the city that Rosenberg – in parallel to Roth – noted as ‘one of the main Jewish centers.’Footnote67 Roth was well informed. Subsequent research shows that the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg targeted Salonica.Footnote68 Until recently only a fraction of the materials had been found.Footnote69 Then in 2021, Russia admitted to having acquired the archives when the Red Army captured Berlin from Nazi Germany in 1945. Russia agreed to return to Salonica the books and religious artifacts which had been stolen from the city’s synagogues, libraries, and community organizations. The Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece (KIS) welcomed the news: ‘our history is coming home, finally! For Greek Jewry, these records illuminate its historical path, sacred relics that record the light of life and the darkness of looting and the Holocaust.’Footnote70 However, Russia’s war with Ukraine beginning in 2022 halted discussion, and the archives have not yet been returned.Footnote71 Yet such contemporary recognition of the stolen archives as ‘sacred relics’ underlines the potential importance of Roth’s presence in Greece in 1946 and of the objects he collected.

Roth did not go to Greece after the war in order to collect, however. Indeed, he felt that his Committee and British Jewry were increasingly sidelined by comparable organizations based elsewhere run by other key Jewish academics. These included Gershom Scholem’s Committee for the Recovery of Jewish Cultural Property of the World Jewish Congress at Hebrew University (where all organizations agreed recovered property should be held, even if only temporarily); and, in particular, Salo Baron’s Commission on Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, established in New York the year after Roth’s Committee. Both organizations seem likely to have been catalyzed into existence as a result of Roth’s communications with New York and Jerusalem to get Jewish scholars to collaborate with his British-based committee on collection.Footnote72 The struggles between these organizations have been described as internecine.Footnote73 Roth made the case for Britain to receive a substantial portion of the recovered property. The Mocatta Library of Judaica in London, which had been established under the JHSE and on whose committee Roth sat, had been bombed in 1940 and many of its holdings destroyed. However, after the war Roth felt ‘shortchanged’ and ‘disadvantaged’ in the distribution of Judaica recovered from Europe.Footnote74 He believed that Britain never received its fair share, including from British-occupied territories.

Greece was one of these territories, which is why British troops were stationed there when Roth was invited to lecture to them in 1946 as part of his larger tour to lecture to British troops in the Middle East. Roth stopped in Salonica on his return home from Cairo.Footnote75 His tour seems likely to have been part of the British Army Education program, run through the War Office, which maintained Education Centers in all major towns throughout the Middle East and the Mediterranean.Footnote76 During the war Roth had worked as an army lecturer, lecturing to British troops in Italy as they advanced.Footnote77 The British Army Education program was designed ostensibly to boost troops’ morale, but it had an underlying ideological role justifying British military action abroad. The program and this goal continued post-war through the Cold War, as Roth lectured in Greece.

Roth’s visit to Greece coincided with the beginning of the Greek Civil War, which, running from 1946 to 1949, was the first proxy war of the Cold War. During this time Britain ‘became entangled to an unprecedented degree in the internal affairs of Greece.’Footnote78 Britain saw Greece as vital for its own continuing political, economic, and military influence in the Middle East and the Mediterranean.Footnote79 The Greek Civil War was staged between the leftist Democratic Army of Greece and Rightist forces loyal to ruling government who sought the reestablishment of the monarchy. The British supported the latter, determined to maintain their own imperial interests and that Greece should not become communist.Footnote80 The British Army had accompanied the ruling Greek government on its return from wartime exile in Egypt to Greece in October 1944. By 1945 there were numerous British and Allied military formations in Greece engaged in anti-communist warfare.Footnote81

However, Britain’s interests in Greece during the Second World War had been quite different. British intelligence had been operating unofficially in Greece since 1942 (including in Salonica), working with the Greek resistance against the Nazis. Among the resistance were many of the same communists whom the British Army considered the enemy in the Greek Civil War. ‘British military and political interests tugged different ways,’ including differently at different times.Footnote82

A chain of events led to the production of Greece’s Jewish relics, in which military and civilians, Greeks, Nazis, and the British were all involved, with Roth at one troubling and not entirely clear intersection. Greeks collaborated with Nazis in the destruction of Jewish objects. However, one factor influencing collaborator behavior as early as 1942 was fear of British victory in the Middle East and the renewed intervention of Britain in Greece’s affairs.Footnote83 King George of Greece returned to Greece from exile in London in September 1946, following a referendum in support of his return. The British helped engineer the referendum result since the restoration of the Greek monarchy secured British influence in Greece.Footnote84 Roth’s visit occurs just three months before these events. Roth’s publications and unpublished documents locate his interests in Jewish history in Greece and documenting post-Holocaust Greece. They do not reveal his thinking on Greek-British political relations. However, in working for the British Army, Roth could be seen as an apologist for Britain’s restoration of the Greek monarchy and quashing of a democratic Greek republic.

How did Roth’s position working for the British Army compromise his collection of the Sefer Torah shoe soles? Was he so straightforwardly rescuing this artifact of Jewish life from post-Holocaust Greece? On the one hand, in collecting the soles, he ensured that the Sefer Torah would not be on the floor (a Sefer Torah should never touch the floor according to rabbinic tradition and is itself untouchable with the human body once it is completed). On the other hand, Roth’s export of the items to Britain further deracinated the scroll from its provenance and any of its surviving community. Roth’s collection is an act of appropriation and intervention enabled by, if not parallel to, Britain’s foreign policy intervention in Greece.

It is worth considering Roth’s alternatives to the act of collection. He could have left the soles in Greece. Roth had strong connections with the Greek Jewish community. Other documents related to Salonica in his collections show that he corresponded and exchanged research with Greek Jewish historians such as Michael Molho and Isaac Emmanuel.Footnote85 Molho, Salonica’s rabbi and principal historian immediately after the Holocaust who was also collecting material about Holocaust relics in the case of the destroyed Jewish cemetery, guided Roth during his visit to Jewish sites in Salonica and became a sustained correspondent. Why not give the soles to Molho? Even in the wake of the Holocaust and despite being informed about splits in the Greek Jewish community about where their future lay, Roth believed in the longevity of Jewish life in Greece as elsewhere in the diaspora. He was not a Zionist in the sense of supporting ‘an ingathering of exiles’ – either displaced peoples, or displaced artifacts – that was used to argue for the transfer of refugees and archives to Jerusalem/Palestine.Footnote86 Of Greece devastated by the Holocaust Roth wrote, ‘there is a Holy Land to be won back in the Diaspora.’Footnote87 Given the trauma among the Jewish community and devastation of sites that Roth witnessed and wrote about on his Greek tour, this optimism appears unfounded; and a desecrated Sefer Torah, especially left with a devastated community, might seem to contradict his optimism. Alternatively, Roth could have sent the Sefer Torah shoe soles to Hebrew University, but we already know of his reluctance to export diaspora Jewish archives to Palestine. Instead, then, Roth brought them to the UK.

Especially immediately following the Second World War, but even during it as Roth’s own address to the JHSE in 1943 indicates that he knows, collecting Holocaust relics was controversial and the subject of fierce debates. The line between salvage and sacrilege, rescuing and theft, was porous. The location of Jewish objects and texts uprooted from their communities by the Holocaust became quickly tied to the question of the plausible continuity or reconstruction of those communities, and to the belonging and survival of people themselves, Jews displaced by the Holocaust. There was a connection between what happened to the archives and where the future of Jewish life lay.Footnote88 Roth’s collections reveal that at various points in his career he exported many items from other diaspora Jewish communities to Britain, and some cases might not have been legal or ethical. For instance, in 1935, Roth acquired some ancient Karaite manuscripts in Egypt and sought to take them out of the country by way of Jerusalem. He was stopped at the border between Egypt and Palestine by a customs officer who told him that he could not remove the manuscripts from Egypt. Roth’s academic credentials, but also the promise to sell an old family Bible for this official, reversed the situation and Roth was allowed to take the documents.Footnote89 The Karaite manuscripts going back centuries are now held in the University of Leeds Library. Is this the best place for them? How much did the fact that de jure independent Egypt remained occupied and de facto ruled by the British, and that Palestine was then under the British Mandate, facilitate Roth’s removal of the manuscripts from the Middle East? What is the relation between the exporting of part of their archive from Egypt and the exodus of the country’s Jewish population that was around 63,000 at the time of Roth’s visit and that now numbers 100?Footnote90 The political and ethical significance of British collecting in Greece and restitution of objects has been debated for decades, most famously in relation to the Parthenon/Elgin marbles, which are still held by the British Museum.Footnote91 While on a much smaller scale, the questions raised by Roth’s Greek and Middle Eastern collections are not dissimilar.

Roth has much in common with Zosa Szajkowski, the Polish-Jewish collector whose story as an ‘archive thief’ Lisa Leff has written.Footnote92 Both Roth and Szajkowski were historians and collectors salvaging Judaica in the face, and then in the wake, of the Holocaust. Roth and Szajkowski at points even sold collected Judaica to the same dealer in Oxford, A. Rosenthal Ltd, one of the most significant brokers in Judaica at the time.Footnote93 However, Roth was emphatically not a thief. He paid for or was given items in his collection, even if he sometimes resorted to smuggling or giving backhanders to transport them to Britain. At his address to the Conference on Restoration of Continental Jewish Museums, Libraries and Archives in 1943, Roth recounts how before the war he was offered ‘through reputable agencies in this country [Britain]’ Judaica and art of German Jewish provenance sold by the Nazi government.Footnote94 The clear implication is that he refused to accept the deal. He was not going to acquire items under such circumstances.

Roth’s adding the shoe soles to his collection is a complex act. Given how much more discussion there has been since his time of the significance of the restitution of Holocaust archives, given his busy-ness as a collector and historian, it is likely that he gave its consequences less thought than I am giving it here. But for whom and for what purpose did Roth collect the Sefer Torah soles? What did Roth plan to do with them? It is to this concern, the afterlife of relics, that I now turn.

The afterlife of relics: uses and abuses

We have already encountered one use Roth had for the Sefer Torah shoe soles, that is, in his writing. Irene Roth depicts her husband as above all intellectual, definitely not lachrymose (in the words of her title, Roth was an ‘historian without tears’).Footnote95 But his one mention of them in his list of evidence of post-Holocaust devastation that he witnessed in Greece shows that he understood the power of the shoe soles, even in description, as affective symbols. Although nowhere does he tell us so, Roth’s own relation to the Sefer Torah soles is likely to have been affective.

Roth’s writings from his Greek tour create some confusion, in particular about where exactly he collected the Sefer Torah soles. Roth first mentions a Sefer Torah fragment – although not shoe soles – soon after his visit. In a series of reports on what he witnessed on his Greek tour that he published in the Jewish Chronicle in 1946, he writes that in Arta, the whole community had been destroyed or looted, ‘with the exception of a small strip of an ancient Sefer Torah.’Footnote96 Was this ‘small strip’ the same ‘fragment of a Sefer Torah which had been cut up as soles for a pair of shoes’ that Roth describes being given in his essay in Commentary four years later? We do not have reliable records of Roth’s collecting – how, when, and where he acquired items, and least of all why.Footnote97 Limited information can be gleaned from his notes and anecdotes appearing in his introduction to his handlist, from one or two of his essays, and from Irene Roth’s similarly anecdotal accounts in her memoir.Footnote98 Irene Roth claims that Roth acquired the Sefer Torah shoe soles in Salonica.Footnote99 It is worth mentioning that the Leeds sole is not filed along with Roth’s Salonica papers but separately, in his Judaica.

However, while we cannot be sure of the exact provenance of the objects, it seems almost certain that the Arta Sefer Torah fragment and the Salonica Sefer Torah shoe soles are the same, since Roth’s references to these in his writings are in relation to his Greece tour and the only Sefer Torah fragments in Roth’s collections on either side of the Atlantic are the shoe soles. Moreover, Roth’s single reference to the shoe soles in his Commentary essay does not locate them in Salonica specifically but in ‘Greece’ generally.Footnote100 It seems that Roth acquired the fragments in Arta. In Arta, the number of Jews killed may have been less than in Salonica, but the community was no less decimated. Of the 384 Jews deported from Arta in 1944, 84% were killed.Footnote101 I suggest that between his first more journalistic reports on Greece in 1946 and his more reflective and philosophical Commentary essay in 1950, Roth considered further and used the significance of the Sefer Torah being cut into shoe soles. Realizing the affective force of the objects as Holocaust relics, he deployed their symbolic power in his writings, first tied to the destruction of Greek Jewry in Arta specifically, then metonymically representing that in Salonica and Greece as a whole. In a sense, he circulated the Sefer Torah fragments as relics from one piece of writing to another, amplifying that power.

Did Roth ever use the Sefer Torah shoe soles in a more directive manner? Irene Roth remembers that Roth planned to use the soles in his lecture tour to South Africa in 1947 arranged by the South African Board of Jewish Education: ‘He was determined to show these remnants of a desecrated Torah scroll to his lecture audiences in South Africa’Footnote102 There is no evidence whether Roth carried out this plan, or its precise details. In what pedagogical context would Roth have used the objects? To illustrate the Holocaust’s destructive force broadly? Or to speak specifically about the near annihilation of Greece’s Jews? To show how the Holocaust also tried to destroy Jewish culture? To discuss the relationship between communities, Greek Jews and non-Jewish Greeks? To speak, as I have here, about desecration in the making of a relic? In any case, given his interest in material culture, Roth’s approach might have been quite similar to that of Holocaust museums now, that is, using objects as evidence of and for edification about the Holocaust’s atrocities.

Roth did not pass the soles onto the Jewish Museum in London, and I strongly doubt that he intended for them to be exhibited. According to halacha, Sifrei Torah damaged beyond repair should not be used in religious services or displayed but buried in a ‘funeral’ or stored provisionally in a genizah, a repository area. According to these laws, museums that exhibit such scrolls risk perceptions of further desecration of the Torah. The USHMM responds to the rabbinic rule by displaying its Holocaust-damaged Sifrei Torah in a ‘transparent Genizah,’ but even then this has caused considerable controversy.Footnote103 And as Vanessa Ochs asks of this exhibit, is the display of a rescued Sefer Torah ‘sufficiently eloquent enough to tell the story of the Holocaust for generations to come’?Footnote104 I suspect not without the biography, and that biography should include as much as it can of the story of collecting, making, and circulation. Roth was neither Orthodox enough to bury the soles, but nor did he seek to make a permanent exhibit of them. Beth Tzedec displayed its Roth sole in a raised glass case in a synagogue museum. We will have to see what choices are made by curators after the collection’s move to the Royal Ontario Museum, where the Roth Collection will no longer be held within a dedicated Jewish museum and so the public might generally be assumed to have less knowledge about the original status of, or the traditional approach to, the object.

For Roth, many items in his collection crossed boundaries between display and utility, personal and public, historical and contemporary. His and his wife’s collection filled their home, rendering it ‘a museum come to life.’Footnote105 During Roth’s time at the University of Oxford, students would spend Erev Shabbat (Friday night) and Jewish festivals at the Roths’ home and be amazed to find Roth not only using megillot (scrolls) from his collection but allowing handling of these rare and precious objects.Footnote106 For Roth, even rare and ancient Judaica was not dead but alive. These objects were not relics in common usage but showed how objects from the past can maintain and acquire meaning for the present day. From his home, Roth’s collections subsequently made their way into archives – the objects and art mainly to the Jewish Museum in London and Beth Tzedec in Toronto, and the manuscripts and books mainly to the University of Leeds.

Was Roth’s allowing handling of parts of his collection a sign of a kind of devaluing of the artifacts or at least carelessness towards them? Irene Roth writes about how during the Six-Day War in Israel in 1967, which the Roths experienced after leaving Oxford permanently for Jerusalem in 1964, some of Roth’s personal papers were stolen from a basement while he was editing the Encyclopaedia Judaica. Over a decade later Irene re-acquired the papers via a junk shop in Jerusalem.Footnote107 Granted, the stolen items were not Judaica but personal documents. But this gets me onto the question of what happens to an archive when the collector moves, when the collection is disturbed or sold – and how the Sefer Torah shoe soles came to be split up and whether they should be reunited.

Roth sold part of his collection in 1961 when the Roths began planning to sell their house in Oxford for their departure for Jerusalem. At this point, Roth’s books and manuscripts were acquired for the University of Leeds by Stanley Burton who, with his father Montague, was a friend of the Roths.Footnote108 Montague Burton, founder of Burton Menswear, was a tailor principally based in Leeds who was the main supplier of uniforms for the British Army during the Second World War. Interestingly, the British Army therefore have a role to play even in the final stage of how one sole came to Leeds. In 1965 Beth Tzedec Synagogue Museum in Toronto acquired the art and ritual objects left in Roth’s collection, making the museum one of the principal collections of Judaica in North America. The acquisition, made while Roth was teaching at Queens College at the City University of New York, came to Toronto as a gift of the Shopsowitz family, owners of a chain of delicatessens in Toronto and meat processors in Canada.Footnote109 The University of Southampton acquired Roth’s correspondence and research papers, supplementary to the University of Leeds Collection, as part of its archives of Anglo-Jewry, a world in which Roth was a key player.Footnote110 In this division of Roth’s archive, how did the Sefer Torah shoe soles become separated? Was the separation accidental on the Roths’ part or deliberate? The shoe soles could be classified either as ritual objects, or as manuscripts. As the allocation in practice of objects to Leeds and Toronto indicates, Roth vacillated about whether to classify scrolls as art objects or as manuscripts; for instance, there are ketubot (marriage contracts in both sites). If Roth’s splitting of the pair was deliberate, perhaps because he classified them as at once object and manuscript, in making the soles further diasporic he maximized the number of us who could come into contact with them and learn from them.

Should the shoe soles be reunited after sixty years of separation, paired as they were when Roth acquired them? And if so, where is the best place for them? Leeds, Toronto, or somewhere else? Perhaps the Jewish Museum in London (although temporarily closed and seeking a new home as of writing), given that it was founded by Roth and held a research center? Or the Wiener Holocaust Library in London as Britain’s largest archive of Holocaust material?Footnote111 More persuasively, the Sefer Torah shoe soles might be returned to Greece, especially in the light of recent discussion about the discovery and failure to return Thessaloniki’s stolen archives. The Jewish Museum in Thessaloniki, whose mission is ‘to gather the evidence and relics that were not destroyed in the Holocaust,’ opened in 2001.Footnote112 Moreover, a dedicated Holocaust Museum of Greece to be located in Thessaloniki is in planning, having received a pre-approval building permit.Footnote113 The Sefer Torah shoe soles certainly fit community president David Saltiel’s description of stolen archives as ‘sacred relics that record the light of life and the darkness of looting and the Holocaust’; their return might validate his sense that ‘history is coming home.’Footnote114 In Thessaloniki and elsewhere, the Jews of Greece have re-established communities. Synagogues have been rebuilt, schools re-opened, and the Holocaust is increasingly memorialized in material culture and other ways. Even as they seek to gather relics that tell the story of the Holocaust, Greek Jewry is by no means itself a relic.

Or should the shoe soles follow the direction of travel for most items recovered after the Holocaust, to Israel, perhaps to the collections of Yad Vashem, which considers itself ‘the ultimate source for Holocaust education, documentation and research’ and which has a comparable project ‘Gathering the Fragments’ on recovering personal items that tell the story of the Holocaust?Footnote115 Given that the Sefer Torah soles are made of stolen Judaica, they count as part of the stolen archives of Jewish manuscripts, books, and art which Israel has sought to ingather after the Holocaust. One advantage of Israel would be that it is more likely to contain the research expertise, especially among sofers (scribes), to work more on the soles’ history.

I do not have an answer to this question regarding the originals, but I do think that the soles should be digitized, cross-referenced, and their story known, including that of their collection. There is surely further research to be done on them, including dating of the Sefer Torah itself, where it might have been created, and what synagogue it was stolen from.

Conclusion

In an essay reflecting on his methodology of collecting published in 1957, Roth writes, ‘But in Salonica (though this was after the virtual annihilation of the community in 1941) I did not find even a scrap of paper or piece of metal of Jewish interest.’Footnote116 Albeit this was some twenty years after his visit to Greece, how can Roth fail to mention, in an essay on collecting, the Sefer Torah soles, which were precisely scraps? What disavowal, or failure of memory, of the material that my essay has focused on?

Roth’s essay ‘The Art and Craft of Jewish Collecting: Dealings in the Higher “Junk,”’ as extraordinarily light, is a serious underestimation of Roth’s collection and his methodology, even though the essay tells us much about how Roth viewed his own approach to collecting. To name as ‘junk’ his substantial Judaica at the same time as acknowledging its contents as higher is contradictory, to say the least. Despite his earlier criticism of Nazi collectors as ‘perverted collectors,’ Roth makes clear here that neither does he consider himself a ‘true collector.’ Discussing Jewish collections and collectors he has known, Roth is ambivalent, indeed critical, about the act of collection per se; ‘for your true collector must be willing to thieve, lie, steal.’Footnote117 Moreover, ‘true’ collection – by which Roth seems to mean professional collection – is morbid: ‘In due course your true collector becomes utterly ghoulish’; ‘sometimes he’s on the doorstep nearly as soon as the undertaker.’Footnote118 Moving in immediately after and inextricably associated with death, the collector goes against the sacred valuing of life by severing ties further between people and their possessions.

If Roth did not present himself as a professional collector and suggested all serious collection as to some degree ‘perverted,’ I want to suggest this as inextricable from the relic’s destructive dynamics. As we have seen in the case of the Sefer Torah shoe soles, collection’s necessary first stage is divorcing material from people who own, use, and perhaps revere it. This severing from meaning, context, and usage is ‘perverted’ in the truest sense of turning to ill effect. And the collection of Judaica must have seemed especially perverted for Roth as an observant Jew because of his intimacy with the sacred and communal purpose of objects which no longer had that usage. To collect a relic connects the collector to the process, if not the act, of ripping a portion from a Torah scroll, destroying a grave and stealing a tombstone, and consuming an ethnic food while forgetting the people who invented it once you have killed them, to go back to Roth’s list with which I started.

As Holocaust relics, Roth’s Sefer Torah shoe soles encapsulate a set of paradoxes: their Jewishness has been subject to near destruction but is still readable; they are materialities of Jewish life that have become severed from their Jewish contexts; and their religious or ritual function has been secularized and quotidienized. A further paradox is that, although the Jewishness of these relics has been forgotten and fragmented by those using them, it is remembered and collected by Roth as Jewish historian and collector. Something of the sacredness of the relic can be restored in our encounter with the objects, even as the circumstances of collection demand that we consider the ethical and political contexts that enable our encounter. Collections of Judaica, particularly post-Holocaust collections, would be nothing without this dialectic between destruction and collection, forgetting and remembering, salvage and sacrilege, that lies at the heart of relics. It is this story that the shoe soles tell.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dorion Liebgott, curator of Beth Tzedec Museum, Toronto and to Noa Or, in the Artifacts Collection of Yad Vashem, for help with the research; to Eva Frojmovic, Director of the Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Leeds, for being my fellow traveller in exploring the Roth Collections; and to the anonymous reviewers for this journal for their comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jay Prosser

Jay Prosser is Reader in Humanities at the University of Leeds, where he is a member of the School of English and the Centre for Jewish Studies.

Notes

1 Note on place name: Roth uses Salonica and Salonika interchangeably throughout his writings; he never uses Thessaloniki, even though his visit to and writings on the city occur at least twenty years after the city’s revival of its ancient Greek name of Thessaloniki. For standardization purposes I use the spelling Salonica, except when Salonika appears in the original. I use Thessaloniki when referring to the city in the present day.

2 Roth, “Last Days.”

3 Ibid.

4 MS Roth/517, Sefer Torah (ḳeṭaʿim), two strips of a Pentateuchal scroll cut into shape by a cobbler as soles for shoes (no date), Cecil Roth Collection, University of Leeds Library.

5 CR 140, strips of Pentateuchal scroll cut into shape by a cobbler (recovered in July 1946), Cecil Roth Collection, Reuben and Helen Dennis Museum, Beth Tzedec.

6 Dorion Liebgott, email message to author, February 15, 2023.

7 I can find only one, brief, mention of Roth’s Sefer Torah shoe soles and this to Roth’s quotation above rather than to the objects themselves. See Naar, Jewish Salonica, 277.

8 Kopytoff, “Cultural Biography of Things.”

9 A special issue of Past & Present on ‘relics and remains’ is mostly pre twentieth century, with one essay on the Holocaust. See Past & Present 206, no. 5 (2010), special issue “Relics and Remains.” The Routledge Companion to Jewish History includes no essay on relics. See Bell, Routledge Companion. Its single essay on material culture does not mention relics. See Leibman, “Material Culture.”

10 Stier, “Torah and Taboo,” 508.

11 Waxman, “Testimonies as Sacred Texts”; Eschebach and Harsch, “Soil, Ashes, Commemoration”; Polzer, “Durkheim’s Sign Made Flesh.”

12 Shallcross, Holocaust Objects, 2.

13 Levitt, Objects That Remain.

14 Levitt, “Contemporary Relics,” 69.

15 Bilsky, “Cultural Genocide and Restitution,” 351.

16 Glickman, Stolen Words.

17 “Memorial Scrolls Trust,” accessed March 3, 2023, https://memorialscrollstrust.org/index.php/our-history/bohemia-moravia. See also Bernard, Out of the Midst.

18 “Our Czech Scroll,” York Liberal Jewish Community, accessed March 3, 2023, https://jewsinyork.org.uk/our-czech-torah-scroll/.

19 “Humiliation and Abuse: Artifacts Made from Desecrated Torah Scrolls,” Yad Vashem, accessed March 3, 2023, https://www.yadvashem.org/artifacts/museum/desecrated-torah-scrolls.html.

20 Noa Or, email messages to author, February 6 and 16, 2023.

21 Grimsted, “Roads to Ratibor,” 402.

22 Chandrinos and Droumpouki, “German Occupation,” 31.

23 Naar, Jewish Salonica, 9.

24 Ibid., 277. See also Bowman, ed., Holocaust in Salonika; Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts; Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece; Plaut, Greek Jewry; Chandrinos and Droumouki, “German Occupation”; Lewkowicz, Jewish Community of Salonika.

25 Kavala, “Scale,” 196.

26 Kornetis, “Expropriating.”

27 Dan Saporta, interview 40729, interview by Nina Molho, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation, February 15, 1998, https://vha.usc.edu/testimony/40729?from=search&seg=68.

28 Menasche, Birkenau (Auschwitz II).

29 For discussion of the Jewish Cemetery in Salonica, see Molho, In Memoriam; Saltiel, “Dehumanizing the Dead”; Hesse and Laqueur, “Bodies Visible and Invisible”; Naar, Jewish Salonica, 239–76.

30 Katherine Fleming, Greece – A Jewish History, 168.

31 Special Operations Executive: Balkans, National Archives, Kew, HS5/242, cited in Clogg, ed., Greece, 1940–1949, 113.

32 Ibid.

33 Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts, 432.

34 Waligórska and Sorkina, “Second Life.”

35 For an account of the interest in objects in memory studies, see Freeman, Nienass, and Daniell, “Memory/Materiality/Sensuality.”

36 Levitt, “Contemporary Relics”; Levitt, Objects That Remain.

37 Hirsch and Spitzer, Ghosts of Home, xix. See also Hirsch and Spitzer, “Testimonial Objects.”

38 Hirsch, Generation of Postmemory, 208.

39 Levitt, “Contemporary Relics,” 64.

40 The inverse relation between the minuteness of an object and its affect is discussed by Hirsch and Spitzer in relation to a tiny book of drawings from a Romanian concentration camp. See Hirsch and Spitzer, Ghosts of Home, 220–29.

41 Hirsch, Generation of Postmemory, 208.

42 Leibman, “Material Culture,” 352. This realization accords with ‘the corporeal turn’ in Jewish studies. See Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, “Corporeal Turn.”

43 “Sefer Torah.”

44 Roth, Jewish Museum, 3.

45 Exod.35–38:20 (JPS).

46 Exod.38:21–40 (JPS).

47 Yerushalami, Zakhor.

48 Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 221. Levitt also writes about the aura of the relic. See Levitt, “Contemporary Relics,” 64.

49 Raphael, “In Search.”

50 Handlist 164.

51 Roth, Cecil Roth.

52 Roth, Cecil Roth; Handlist 164.

53 These items are held in the Cecil Roth Collection, University of Leeds Library.

54 The following acknowledge Roth’s principal role in World War II collection: Weiss, “Tricks of Memory”; Weiss, “Von Prag nach Jerusalem”; Gallas, Mortuary of Books; Herman, Hashavat Avedah.

55 Roth, Opening Address.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid.

60 Ibid.

61 Weiss, “Tricks of Memory.”

62 Noting parallels and paradoxes was characteristic of Roth’s approach to Jewish history, as suggested by the title of his talk to the Menorah Summer School in July 1930, “Parallel and Paradox in Jewish History.” See Roth, “Paradoxes of Jewish History.”

63 Roth, “Last Days.”

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Chandrinos and Droumpouki, “German Occupation,” 18.

67 Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts, 423.

68 Grimsted, “Roads to Ratibor,” 402.

69 Molho, Salonica and Istanbul, 50.

70 President David Saltiel and General Secretary Victor Eliezer, “Letter to the Prime Minister on the Return of the Files from Moscow,” Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece (KIS), January 3, 2022, https://en.kis.gr/index.php/home/istoriko.

71 Sofia Papadopoulou, “Interview of the President of KIS on the Preservation of the Memory of the Holocaust 80 Years After the Expulsion of the Jews of Thessaloniki,” Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece (KIS), March 28, 2023. https://www.kis.gr/index.php/arthra/ellinikos-evraismos/synenteuxe-tou-proedrou-tou-kise-gia-te-diaterese-tes-mnemes-tou-olokautomatos-80-chronia-meta-ten-ektopise-ton-ebraion-tes-thessalonikes.

72 Weiss, “Tricks of Memory.”

73 Herman, Hashavat Avedah, i.

74 Gallas, Mortuary of Books, 137, 154.

75 Roth, Cecil Roth, 157; Roth, “Greece 1946 – Impressions on a Tour (1).”

76 White, Story of Army Education.

77 Roth, Cecil Roth, 155. See also Roth, “Cecil Roth: A Vignette,” xvii.

78 Clogg, Greece, 1940–1949, 1.

79 Sfikas, British Labour Government, 56 and passim.

80 Richter, British Intervention in Greece, vii.

81 Jones, “British Army.”

82 Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece, 5.

83 Apostolou, “Greek Collaboration in the Holocaust and the Course of War,” 89–112.

84 Parvantes, “Tale of Two Referenda,” 245–46.

85 MS Roth (pers) 8, papers, letters and papers of Dr Cecil Roth relating to the Jewish community at Salonika at the end of the Second World War (1946–48), Cecil Roth Collection, University of Leeds Library.

86 The phrase ‘an ingathering of exiles’ was used in relation to post-Holocaust archives by Alex Bein in 1949. Lustig, Time to Gather, 52.

87 Roth, “Greece, 1946 – Impressions on a Tour (1),” 11.

88 Lustig, Time to Gather. Lustig’s title A Time to Gather comes from Ecclesiastes via Roth, who used it to criticize the transfer of Jewish collections from Italy to Jerusalem. Lustig, Time to Gather, 1.

89 Roth, Cecil Roth, 111–12.

90 “Egypt: World Jewish Congress,” accessed March 3, 2023, https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/about/communities/EG.

91 Mark Mazower, “Give Them Back! Did the Ottomans Preserve the Parthenon and Elgin Wreck It?” TLS, February 10, 2023, https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/who-saved-the-parthenon-william-st-clair-book-review-mark-mazower/.

92 Leff, Archive Thief.

93 Ibid., 18.

94 Roth, Opening Address.

95 Roth, Cecil Roth.

96 Roth, “Greece 1946,” 5.

97 Kathrin Pieren, “The Early History of the Jewish Museum London and Cecil Roth’s Involvement” (Sadler Seminar Series The Archive after Cecil Roth: Jewish Studies, Cultural History and the Cecil Roth Collection, University of Leeds, May 8, 2019).

98 Handlist 164; Roth, “Art and Craft”; Roth, Cecil Roth.

99 Roth, Cecil Roth, 158.

100 Roth, “Last Days.”

101 Plaut, Greek Jewry, 68.

102 Roth, Cecil Roth, 158.

103 Stier, “Totem and Taboo,” 521.

104 Ochs, Inventing Jewish Ritual, 188. Levitt states similarly of the shoes on display at the USHMM that they are ‘ultimately mute.’ Levitt, Objects that Remain, 153.

105 Raphael, “In Search.” See also Roth, Cecil Roth, passim.

106 Roth, Cecil Roth, 44. Roth’s use of scrolls at festivals has been corroborated by former students. Personal conversation with author, May 8, 2019.

107 Roth, Cecil Roth, 230–31.

108 Ibid., 149.

109 Dorion Liebgott, “Art and Jewishness: Cecil Roth’s Judaic Artifacts in Toronto” (Sadler Seminar Series The Archive after Cecil Roth: Jewish Studies, Cultural History and the Cecil Roth Collection, University of Leeds, June 5, 2019).

110 Karen Robson, “The Cecil Roth Papers at Southampton” (Sadler Seminar Series The Archive after Cecil Roth: Jewish Studies, Cultural History and the Cecil Roth Collection, University of Leeds, March 13, 2019).

111 “History,” The Wiener Holocaust Library, accessed March 3, 2023, https://wienerholocaustlibrary.org/who-we-are/history/.

112 “The Mission of the Museum,” Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki, accessed March 3, 2023, http://www.jmth.gr/article-06032014-i-apostoli-tou-mouseiou.

113 “David Saltiel: ‘I am Greek, Jewish in Religion and, to be More Precise, Sephardic from Thessaloniki,’” EJC: European Jewish Congress, September 12, 2023, https://eurojewcong.org/news/communities-news/greece/david-saltiel-i-am-greek-jewish-in-religion-and-tobe-more-precise-sephardic-from-thessaloniki/.

114 President David Saltiel and General Secretary Victor Eliezer, “Letter to the Prime Minister on the Return of the Files from Moscow,” Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece (KIS), January 3, 2022, https://en.kis.gr/index.php/home/istoriko.

115 “About Yad Vashem,” accessed March 3, 2023, https://www.yadvashem.org/about.html.

116 Roth, “Art and Craft.”

117 Ibid.

118 Ibid.

Bibliography

- Antoniou, Giorgos, and A. Dirk Moses, eds. The Holocaust in Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Apostolou, Andrew. “Greek Collaboration in the Holocaust and the Course of War.” In The Holocaust in Greece, edited by Giorgos Antoniou, and A. Dirk Moses, 89–112. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Bell, Dean Phillip, ed. The Routledge Companion to Jewish History and Historiography. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, 217–252. London: HarperCollins, 1992.

- Bernard, Philippa. Out of the Midst of the Fire. Marlborough: Westminster Synagogue, 2005.

- Bilsky, Leora L. “Cultural Genocide and Restitution: The Early Wave of Jewish Cultural Restitution in the Aftermath of World War II.” International Journal of Cultural Property 27, no. 3 (2020): 349–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739120000235.

- Bowman, Steven B., ed. The Holocaust in Salonika: Eyewitness Accounts. New York: Sephardic House, 2002.

- Cecil Roth Collection. University of Leeds Library.

- Cecil Roth Collection. Reuben and Helen Dennis Museum. Toronto: Beth Tzedec.

- Chandrinos, Iason, and Anna Maria Droumpouki. “The German Occupation and the Holocaust in Greece: A Survey.” In The Holocaust in Greece, edited by Giorgos Antoniou, and A. Dirk Moses, 15–35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Clogg, Richard, ed. Greece, 1940–1949: Occupation, Resistance, Civil War: A Documentary History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Eschebach, Insa, and Georg Felix Harsch. “Soil, Ashes, Commemoration: Processes of Sacralization at the Ravensbrück Former Concentration Camp.” History and Memory 23, no. 1 (2011): 131–156. https://doi.org/10.2979/histmemo.23.1.131.

- Fleming, Katherine. Greece–A Jewish History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Freeman, Lindsey A., Benjamin Nienass, and Rachel Daniell. “Memory/Materiality/Sensuality.” Memory Studies 9, no. 1 (2016): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698015613969.

- Gallas, Elisabeth et al., eds. Contested Heritage: Jewish Cultural Property After 1945. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2019. https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666310836.

- Gallas, Elisabeth. A Mortuary of Books: The Rescue of Jewish Culture After the Holocaust. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

- Glickman, Mark. Stolen Words: The Nazi Plunder of Jewish Books. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

- Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy. “Roads to Ratibor: Library and Archival Plunder by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg.” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 19, no. 3 (2005): 390–458. https://doi.org/10.1093/hgs/dci041.

- Handlist 164. Leeds University Library. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/114260.

- Herman, Dana. “Hashavat Avedah: A History of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc.” PhD diss., McGill University, 2008.

- Hesse, Carla, and Thomas W. Laqueur. “Bodies Visible and Invisible: The Erasure of the Jewish Cemetery in the Life of Modern Thessaloniki.” In The Holocaust in Greece, edited by Giorgos Antoniou, and A. Dirk Moses, 327–358. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

- Hirsch, Marianne, and Leo Spitzer. Ghosts of Home: The Afterlife of Czernowitz in Jewish Memory. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- Hirsch, Marianne, and Leo Spitzer. “Testimonial Objects: Memory, Gender, and Transmission.” Poetics Today 27, no. 2 (2006): 353–383. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-2005-008.

- Jones, Tim. “The British Army and Counter-Guerrilla Warfare in Greece, 1945–49.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 8, no. 1 (1997): 88–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592319708423164.

- Kavala, Maria. “The Scale of Jewish Property Theft in Nazi-Occupied Thessaloniki.” In The Holocaust in Greece, edited by Giorgos Antoniou, and A. Dirk Moses, 183–207. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. “The Corporeal Turn.” Jewish Quarterly Review 95, no. 3 (2005): 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1353/jqr.2005.0058.

- Kopytoff, Igor. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Kornetis, Kostis. “Expropriating the Space of the Other: Property Spoliations of Thessalonican Jews in the 1940s.” In The Holocaust in Greece, edited by Giorgos Antoniou, and A. Dirk Moses, 228–252. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Leff, Lisa Moses. The Archive Thief: The Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Leibman, Laura. “Material Culture.” In The Routledge Companion to Jewish History and Historiography, edited by D. P. Bell, 343–359. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Levitt, Laura. “Contemporary Relics.” CrossCurrents 71, no. 1 (2021): 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1353/cro.2021.0004.

- Levitt, Laura. The Objects That Remain. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2020.

- Lewkowicz, Bea. The Jewish Community of Salonika: History, Memory, Identity. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2006.

- Lustig, Jason. A Time to Gather: Archives and the Control of Jewish Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Mazower, Mark, ed. After the War Was Over: Reconstruction the Family, Nation, and State in Greece, 1943–1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Mazower, Mark. Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Mazower, Mark. Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430–1950. London: HarperCollins, 2005.