ABSTRACT

This article responds to ‘The theory of practice architectures and its discontents: disturbing received wisdom to make it dangerous again’ by George Variyan and Christine Edwards-Groves, published in Critical Studies in Education in March 2024. The authors use Foucault’s genealogical approach to explore the theory but do not show that or how the theory leads to misunderstandings of social realities, in the way that Foucault’s critiques did. I address the authors’ doubts about whether the theory is characterised by a ‘flat ontology’; whether it has a dualistic or dialectical understanding of the relationship between individuals and societies; and whether the visual depictions of the theory ‘reify and mystify’ social realities. I also consider the authors’ speculation about whether the theory has lost the critical and self-critical capacities necessary for its continuing development. I argue that, in general, researchers using the theory have not lost those capacities, although Variyan and Edwards-Groves are right that, in some hands, it has been used descriptively rather than critically or transformatively (with an emancipatory intent). The article concludes that the critique by Variyan and Edwards-Groves is a sceptical rather than a critical exploration of the theory and the empirical findings it has generated.

Introduction

This article is a brief rejoinder to ‘The theory of practice architectures and its discontents: disturbing received wisdom to make it dangerous again’ by George Variyan and Christine Edwards-Groves, published in Critical Studies in Education in March, 2024. Edwards-Groves has been prominently involved in the development of the theory of practice architectures since 2007. She is also co-author of a new book (Grootenboer & Edwards-Groves, Citation2023) introducing students and researchers to the theory. Variyan and Edwards-Groves refer to the new book when they say,

TPA [the theory of practice architectures] itself aims to articulate a theory of practice that is practical and critical in orientation, so that transformation of unjust conditions that delimit human flourishing becomes possible and achievable (Grootenboer & Edwards-Groves, Citation2023). (p.1)

Their aim in the Critical Studies in Education article is to explore whether researchers using the theory have been losing their critical edge:

… we began to wonder if scholars involved in the development of TPA [the theory of practice architectures] had been sufficiently cognisant of the need to hold open a foyer to ‘question ruthlessly those instruments [being used]’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, p. 249). This ‘ruthless’ reflexivity is crucial to avoid the pitfalls of adopting ‘unthought categories of thought which delimit the thinkable and predetermine thought’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, p. 249). (p.2)

In light of these musings, therefore,

… in this paper, we examine the ‘received wisdom’ in TPA to consider if these inheritances are potentially constraining more radical reimaginings of the theory or if the theory remains sufficient, or sufficiently ‘alive’, as it continues to ‘travel’ beyond education. (p.2)

The authors aim to recover and correct confusions or contradictions about key concepts that may have taken root in the literature of the theory, hindering its further growth and development. Yet they also acknowledge that the issues they raise (e.g. about dualism in the theory, and its handling of agency) have been explicitly problematised and refined in various key texts in the 17-year evolution of the theory (under this name) and in its applications in empirical studies:

… we do not want to suggest that TPA and its practitioners and advocates fail to question and improve upon preceding iterations of TPA (see, for example, Kemmis Citation2019, Citation2022). (p.2)

In making these responses, I am aware that other readers of the theory of practice architectures have arrived at readings of the theory that are similar to those presented by Variyan and Edwards-Groves. A theory is not the exclusive property of those who inaugurate it; if its authors are fortunate, it enters the common stream of thought and practice in a field of enquiry and grows and develops in new and sometimes unexpected directions. It may be read in sometimes contrary and contradictory ways, provoking debate within and beyond the community in which it arose. So, discussions and debates about what the theory of practice architectures is and does are always welcome, especially where they help to clarify the theory and the research and scholarly practice it engenders, both for ‘old hands’ and ‘newcomers’. I offer this rejoinder in pursuit of that aspiration.

In what follows, the section headings are among those in the article by Variyan and Edwards-Groves.

A Foucauldian encounter

Variyan and Edwards-Groves declare (p.4) that they use Foucault’s (e.g. Foucault, Citation1969/Citation1972) genealogical method to explore how language has been used in the construction of an ‘authoritative version’ (p.4) of the theory of practice architectures. They approach the theory as a ‘regime of truth’ (e.g. Foucault, Citation1980, p. 131) which privileges some aspects of and ways of seeing the world over others – as, it should be emphasised, every theory does. When Variyan and Edwards-Groves privilege the language (theoretical categories) of the theory in this way, however, they eclipse other elements of the use of the theory in research and scholarly practice, especially its material effects in the real world, and its social and political character and consequences (which they mention in a section about ‘political theory and the politics of theorising’). Their focus on the language of the theory privileges theoría over praxis, as the ancient Greeks might have said – that is, it privileges contemplation over history-making action (Mahon et al., Citation2020). The developers of the theory of practice architectures necessarily engaged in theoría to create the theory, of course, but it is to be evaluated not only in terms of its success as contemplation (e.g. as a coherent set of ideas) but also in the light of its historical, material, social, and political consequences within and beyond research and scholarly practice. Variyan and Edwards-Groves did not attempt the wider critical task of evaluating the corpus of research using the theory. Such an evaluation might consider, for example, the contributions of research employing the theory to (a) social and educational theorising, (b) policy, and (c) practice across a wide range of different (education and non-education) settings. Variyan and Edwards-Groves focus on the first of these – the danger that the theory may be employed uncritically – but they do not offer or critically explore evidence to suggest that use of the theory may in fact be producing untoward consequences in policy or practice.

They quote Foucault (Citation1977) on genealogical analysis (p.4)

… to follow the complex course of descent [in genealogical analysis] is to maintain passing events in their proper dispersion; it is to identify the accidents, the minute deviations – or conversely, the complete reversals – the errors, the false appraisals, and the faulty calculations that gave birth to those things that continue to exist and have value for us. (Foucault, Citation1977, p. 146)

Despite this Foucauldian ambition, in their discussion of the theory Variyan and Edwards-Groves do not identify accidents, reversals, errors, false appraisals, or faulty calculations: that is, they do not identify where the theory has gone wrong in history and in practice. Rather, they worry that it might have.

Foucault’s genius lies not so much in his claim that science is a flexible system of discursive practices which inevitably use mutable, malleable theoretical categories to pin down realities that nevertheless escape their grasp. His genius lies in demonstrating how discursive practices do this – whether in Madness and Civilisation (Foucault, Citation1961/Citation1967), The Order of Things (Foucault, Citation1966/Citation1970), or Discipline and Punish: The birth of the prison (Foucault, Citation1975/Citation1979). He writes about his aspirations for this genealogical science in his (Foucault, Citation1969/Citation1972) The Archaeology of Knowledge, which describes – not without contradictions – how the genealogist goes about the work of history as archaeology when she ‘transforms documents into monuments’ (p. 7; emphases in original), as Foucault memorably put it. The critique offered by Variyan and Edwards-Groves does not attain this ambition, however; they assert that the theoretical categories of the theory of practice architectures limit current and future thought and practice, but fail to demonstrate – as Foucault does—how research employing the theory of practice architectures does so, nor, crucially, what the untoward historical consequences or practical effects have been, are, or could be.

In this reading, the attitude of Variyan and Edwards-Groves towards the theory is sceptical rather than critical—at least in the sense of a critical social theory that hopes to address and overcome problems rather than just to name them. And this is what a more thorough-going critique of the theory might aspire to do: make a critical appraisal of the theory in terms of its impacts in and on history and practice. It seems to me that many researchers working with the theory are making such critical appraisals, as Jane Wilkinson (Citation2021) and Katina Thelin (Citation2024) have done, in their exploration of the question of how the theory deals with affect and emotion, and as Nick Hopwood et al. (Citation2022; see also Kemmis & Hopwood, Citation2022) have done in extending the theory of practice architectures to show how healthcare practitioners achieved critical praxis in distributed practices in a healthcare simulation through ‘connective enactments’ (mutually orienting practitioners) and ‘collective accomplishments’ (through their coordinated actions).

Structuring an otherwise flat ontology

Variyan and Edwards-Groves argue that the theory of practice architectures fails to live up to its ambition to realise a ‘flat ontology’ (Nicolini, Citation2017, pp. 99–102), that is, a theoretical framework which avoids positing multiple levels of reality. In my view, the theory adopts a flat ontology because it insists that that social explanations can be given in terms of the conduct and consequences of practices, without recourse to ‘higher’ level entities like ‘social structures’. Variyan and Edwards-Groves reject this view. They say

For Schatzki (Citation2003) problems arise in social theorisation that proposes a variety of extra-individual features or influences in human co-existence (what Schatzki calls ‘societist’ theories), [and] tend to ‘suffer a penchant towards reification’ (p. 188), because ‘distinctiveness of the social can be upheld only so long as these [extra-individual] facts are treated as a distinct level of reality, that is to say, only so long as they are reified’ (p. 187). (p.5)

In passing, it should be noted that this is not a clear account of Schatzki’s ‘societist’ position. Variyan and Edwards-Groves suggest that Schatzki repudiates societism, when in fact he adopts a particular form of societism (as he makes clear in Schatzki, Citation2003, and especially, Citation2005, p. 467) – it is a core part of his site-ontological position on practices. Schatzki does, however, reject forms of social theorising that attribute causal power to alleged, reified entities like ‘social structures’ (e.g. Citation2002, p. xiv). Since its inception, the theory of practice architectures has firmly followed this approach (e.g. Kemmis, Citation2022, pp. 8–10; Kemmis et al., Citation2014, pp. 14, 97).

Variyan and Edwards-Groves suggest that the ‘extra-individual’ features shaping practices, noted in Kemmis and Grootenboer (Citation2008) and Kemmis et al. (Citation2014), are examples of reified social structures. This reading is plainly contrary to the argument in those texts. The theory of practice architectures was devised, like Schatzki’s social theory, to show that social explanations can be given in terms of practices without recourse to alleged social structures. Indeed, this is what marks the break between the second generation of practice theorists (e.g. Bourdieu, Citation1977, Citation1990; Giddens, Citation1979, Citation1984) and the third generation (e.g. Schatzki, Citation1996, Citation2002). It also follows earlier developments in social and cultural theory (e.g. Lefebvre, Citation1947/Citation1991, Citation2005; Ross, Citation2023, p. 100) from the 1950s, and builds upon critiques like Larrain’s (Citation1979) critique of the notion of ideology, arguing that ideology is not to be understood as ‘worldviews’, ‘systems of belief’, or ‘false consciousness’ (as Marx and various earlier Marxians had suggested) but rather as transmitted through practices. The realm of the ‘extra-individual’ – a term which began to fade from use after Kemmis and Grootenboer (Citation2008), and was generally replaced in later publications with the notion of intersubjective space—is a space beyond practitioners and their practices, in which different kinds of arrangements (cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political) exist together in sites, sometimes forming practice architectures that create (or not) the relevant conditions of possibility that permit the enactment of specific practices. This theoretical claim (the previous sentence) is just an abstraction, however; the actual (concrete, ontological) cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements that shape a practice are unspecified and unknown without empirical study of a practice in situ. It is a matter for empirical research to discover the conditions necessary and sufficient to allow a practice to happen as it does, and when and how it does, in a site. In short, concatenations of arrangements do not constitute social structures (i.e. analogous to social class, race, ethnicity, or gender as alleged social structures), although they can and do channel the unfolding of practices in life – both the practices of individual actors and the distributed practices realised by multiple participants (e.g. a football game). This is what Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) set out to show in Changing Practices, Changing Education—using the theory of practice architectures to give the first extended account of how various educational initiatives in two Australian education jurisdictions were constituted in practice, particularly in terms of sometimes-ecologically-interdependent teaching practices, classroom practices of students, teachers’ practices of professional learning, leading practices, and practices of research and reflection.

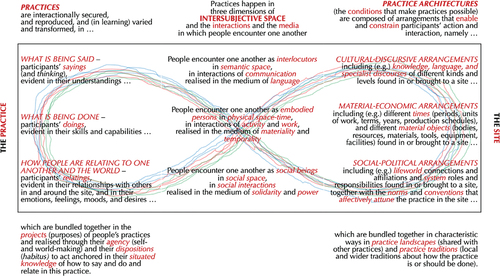

The opposition between flat ontology and social structures might be represented by referring to the summary table outlining some of the key concepts in the theory of practice architectures, seen here in .

While I read as evidence of the flat ontology of the theory of practice architectures (practices being enabled and constrained by arrangements in sites, all on a single ontological level), Variyan and Edwards-Groves see the practice architectures column in the table as tantamount to social structures. It is as if they rotated the figure 90° anticlockwise, removed the words ‘The site’, and replaced them with ‘Social structure’, to manufacture a ‘higher’ level of reality, which they then condemn as reification.

Persisting in this (mis)reading, Variyan and Edwards-Groves go on to suggest that practice architectures are ‘extra-individual properties’ that have causal power ‘over’ individuals. They write

We read this danger in Changing Practices in how extra-individual properties of social inter-actions have a power over individuals, i.e. that such social features ‘enable’ and/or ‘constrain’ individuals. (p.6)

As far as I know, the authors of the theory have never claimed that extra-individual properties ‘have power over individuals’ (italics added). Rather, the theory asserts that arrangements enable and constrain (channel) practices. Variyan and Edwards-Groves (p.6) seem to confuse ‘extra-individual properties’ (as kinds of abstract categories – semantic, material, social) with the ontological arrangements that are actually found in a site. In fact, Variyan and Edwards-Groves mention arrangements only three times in the article: twice in a quote from (Kemmis et al., Citation2014) Changing Practices, Changing Education, and once in a correct description (p.9) of the interconnections between practices and arrangements as construed in the theory.

The authors of the theory of practice architectures do not differ from Schatzki in saying that arrangements (which combine to form practice architectures) channel practices, as Variyan and Edwards-Groves allege, but in fact closely and precisely follow Schatzki – for example when he says that practice-arrangement bundles are ‘fundamental to analysing human life’ (Citation2012, p. 16). When Variyan and Edwards-Groves say that extra-individual properties ‘have power over individuals’, they appear to confuse individuals and practices: it is practices, not individuals, that are channelled (enabled/constrained) by the arrangements that together form practice architectures. While it might be conceded that individuals are channelled by arrangements and practice architectures because they are the ones doing the practising (i.e. when they enact practices), to say that ‘extra-individual properties … have a power over’ individuals is to resort to the mode of explanation favoured by social theorists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who relied on reified notions of social structure (e.g., social class, gender, and race) and gave them causal powers. This was the fallacy that third-generation practice theorists exploded by showing how the widely diffused reproduction of practices in social interactions produced the kinds of regular effects (like domination and oppression) that earlier generations of social theorists attributed to ‘social structures’.

One of the most important insights in Schatzki’s 1990s theorising of the social was his repudiation of the notion of social structures (see, especially, his Citation1994 critique of Bourdieu). Schatzki’s reorientation of social theory towards a site ontological view of practices struck me with great force when I first read it about 2003, since it showed a Wittgensteinian pathway towards theorising and researching practices without the recourse to reified entities like social structures that had bedevilled earlier social theory. The theory of practice architectures closely follows Schatzki in repudiating the existence of social structures as entities with the power to cause anything (like the oppression of subaltern groups). Foucault’s capillary notion of power (e.g. Foucault, Citation1980, p. 98) as circulating through people and their practices similarly casts suspicion on social structures as explanatory concepts. It is no surprise, then, that the theory of practice architectures also regards alleged ‘social structures’ (e.g. social classes, gendered social relations) as no more than after-images left by the operation of practices – after-images in the form of stereotypical understandings (e.g. the subaltern status of the working class or of women) that are conjured into being through an ontological process – namely, the relentless production and reproduction of practices which (e.g.) dominate and oppress workers or women.

Variyan and Edwards-Groves also charge that

Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) seem to misread the caution in … [The Site of the Social; Schatzki (Citation2002)] around reifying a priori structuring of the social, which then establishes ‘fields of possibility’. (p.6)

When Variyan and Edwards-Groves talk about the ‘a priori structuring of the social’, they appear to be referring not just to arrangements (which create what one might call, as they do, ‘fields of possibility’) but about the three-fold categorisation of kinds of arrangements in the theory, that is,

cultural-discursive arrangements (in the dimension of semantic space, manifested in the medium of language);

material-economic arrangements (in the dimension of physical space-time, manifested in the medium of activity and work); and

social-political arrangements (in the dimension of social space, manifested in the medium of solidarity and power).

It should be stressed that it is repeatedly stated in descriptions of the theory that these different kinds of arrangements are only analytically distinct: in reality, they are always interwoven, and, in empirical reality (ontologically), none of them exists or can exist in the absence of the others.

Variyan and Edwards-Groves regard this tripartite division as an a priori presumption; that is, it is a presupposition about how things are organised in the world, while they may be otherwise. Yet they neither show why this division is mistaken (and with what consequences) nor propose an alternative that might be superior.

As (e.g.) Kemmis et al. (Citation2014, p. 30) argue, this tripartite classification has an ancient lineage as a way of viewing the realm of the social, from the ancient Greeks who divided the study of philosophy into (a) dialectics, (b) physics, and (c) ethics (Hadot, Citation1995); to (e.g.) Bourdieu (e.g. Citation1977; Citation1990) on (a) cultural and symbolic, (b) economic, and (c) social and political fields and capitals; and to Habermas (e.g. Habermas, Citation1972, Citation1974) on (a) contemplative, (b) technical, and (c) practical knowledge-constitutive interests. That is, this is not an a priori classification, but one grounded in one reading of the history of philosophy and social theory.

It is not an ‘a priori structuring of the social’ (Variyan & Edwards-Groves, Citation2024, p. 6), then, that ‘establishes ‘fields of possibility’ (p.6), but empirical conditions revealed through research into practices and the arrangements that enable and constrain them.

Variyan and Edwards-Groves return to the problem about social structure in another form when they discuss the alleged dichotomy between the individual and the extra-individual. Referring to Schatzki, they argue that

Such an individual versus extra-individual dichotomy implies ‘two distinct levels of reality’ (Schatzki, Citation2003, p. 187) (p.6)

and that

In our understanding, happeningness is the aliveness of practices being practised, which the bifurcation of self and social annihilates as a first theoretical and methodological step. (p.7)

I concede that, at times, and especially in early writing about the theory of practice architectures, authors of the theory often spoke of the distinction between the realms of the individual and the social in rather dichotomised, dualistic terms. They have striven since then, however, to extirpate that tendency, and have frequently, in text and talk, counterposed that dualistic understanding with a dialectical one: what Mao called ‘the unity of opposites’ (like the chicken and the egg). That is, they see individuals and societies in a dialectical relationship with one another, as does Habermas in his (Citation1987) notion of individuation-socialisation, through which both individuals and societies are formed and transformed. But the relationship between an individual and a society is a different relationship from the one between a practice and the arrangements (practice architectures) in a site that enable and constrain it. It is the latter – the relationship between practices and arrangements – that is the focus of the theory of practice architectures, as it is for Schatzki (e.g. Schatzki, Citation2002, Citation2012.

According to Variyan and Edwards-Groves, however, the theory of practice architectures makes

recourse to a purported dialecticism, and the visual aids and meta rationality of infinity symbols or lemniscates to suture together a two-tier reality (see, for example, Kemmis, Citation2022; Kemmis & Edwards-Groves, Citation2018) (p.8),

and

Arguably, Kemmis et al. (Citation2014 …) are aware of [the] danger of analytically renting apart individuals from their contexts. To shore up the now dissected corpus of the social, they use an infinity symbol over the table form that summarises TPA. (p.8)

Here, once again, Variyan and Edwards-Groves focus on the dualism or dialectic of the individual versus the social, rather than the relationship between practices and the arrangements that enable and constrain them. They also seem to misunderstand the nature of dialectic, as it is used in the theory of practice architectures. They say:

… a dialectic should lead to a Hegellian-like [sic] synthesis … [that] turns the notion of reciprocal mediation of individual and extra-individual features into a conception that is more ontologically ‘flat’ but epistemologically ‘alive’ like the three-dimensional depth effect of stereoscopy. Yet, our more common encounters with the device, for example, the cinematic convention of depicting the view through binoculars is invariably rendered as a double circle, preserves duality, almost as if a resultant unitary synthetical rendering is beyond the intelligibility for the average audience. As such, one wonders if the infinity symbol or lemniscate is an unintelligible or ‘muddy’ resemiotising device. (p.9)

In the opinion of Variyan and Edwards-Groves, then, ‘ … a dialectic should lead to a synthesis’. One might arrive at that conclusion if one followed (e.g.) Bertrand Russell’s (Citation1961, pp. 702–704) account of the dialectic in argument, based on his reading of Hegel: that a thesis is opposed to an antithesis from which there arises a synthesis in the form of a third thought-position from which the relationship between the thesis and antithesis can be comprehended. This rather wooden account of the dialectic differs from another view of the dialectic found Marxian theory (e.g. in Marx and Lenin, and conspicuously in Mao Zedong, Citation1937/1971) and elsewhere: a perspective in which the dialectic is conceived in terms of the unity of opposites. On this view, a dialectical relationship is a relationship of mutual constitution in which one moment of a contradictory pair is necessary in constituting the other, like war as a contradictory moment in opposition to peace, and peace as in opposition to war, so the two form complementary parts of a (dialectical) relationship that plays out in history. A good example of a living dialectic at work in history is in the moiety system of the Yolngu people of North East Arnhem Land in northern Australia. In this cultural practice, people, clans, animals, and everything that exists belongs to either one or the other of two moieties: Yirritja or Dhuwa. Yet this either/or relationship turns into a both/and relationship in living history. Yolngu law requires that marriage must be between men and women from opposite moieties, and, in its patrilineal society, the children are raised alongside their mothers before their first initiation, participating with their mothers in ceremonies, until, after initiation, they participate in ceremonies with their father’s moiety, as now-formally-recognised members of that moiety. (My Yolngu friend thus said of a Yirritja child growing up in these changing relationships, ‘their foot is Dhuwa and their head is Yirritja’.) In this dialectical arrangement, the moieties are opposites through which men and women produce children while simultaneously reproducing both the two moieties and the adult women and men who may go on to become parents in their turn.

Contrary to the claim of Variyan and Edwards-Groves that the theory of practice architectures makes a dualism of individuals and society, authors using the theory repeatedly say that they are in a dialectical relationship, not one that resolves in a passive ‘synthesis’, but one which plays out in the (what Variyan and Edwards-Groves call the ‘epistemologically “alive”’, p.9) happening of lives and histories – which are realised in something like ‘the three-dimensional depth effect of stereoscopy’ (Variyan & Edwards-Groves, Citation2024, p. 9). That is, the authors of the theory do not ‘make recourse to a purported dialecticism’ (Variyan and Edwards-Groves, p.8; italics added) but work with an actual ‘dialecticism’. On a Marxian reading of the dialectic, the authors of the theory argue that, generally speaking, there can be no individuals without some kind of society, and no society without individuals. The two appear together as a mutually constitutive, relational whole, not as a dualism in which one can exist, or even be conceived, without the other. This seems to be widely understood in the community of researchers using the theory. For example, Burgess et al. (Citation2023, p. 121) recently wrote

The theory of practice architectures does away with the dualistic opposition of the individual and the social, or the individual and the collective, and instead sees those poles in dialectical terms, in which each is bound to the other in a relationship of mutual constitution: the individual is a product of the collective, and the collective is a product of the actions of individuals.

But perhaps Variyan and Edwards-Groves do indeed speak for other readers of the theory who have found it difficult to understand the dialectic of the individual and the social, or the dialectic of practices and practice architectures (composed of arrangements). For example, I have read some papers referring to the theory in which authors have confused the ‘sayings’, ‘doings’, and ‘relatings’ of practices with the cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements that shape practices. Mea culpa: I believe some imprecise sentences in the early formulation of the theory in Kemmis and Grootenboer (Citation2008) might have prompted this miscue.Footnote1

Visual meta-rationalities that mystify and reify

Regarding the tripartite (semantic, material, social) depiction of the theory in diagrams, Variyan and Edwards-Groves claim that the authors of the theory run the risk of

… replacing actuality with the virtuality of theoretical idealisations (Grootenboer & Edwards-Groves, 2024Footnote2). (p.8)

It is as if, looking at the photo someone has just taken on their smart phone, they could think that the representation on the screen might now somehow supersede or obliterate the object that the picture is a photograph of. (Although, yes, a person could now regard the representation as a record or as an object of art that has purposes other than representing the scene or a phenomenon.) Yet social and educational researchers studying social and educational practices are usually interested in what goes on in the conduct and consequences of the practices they study in the real, living, happening, historical world, not just in what their reports or books may say about them (how they represent things in the world).

Yet some researchers do take the view that the point of social theorising is contemplation, pure and simple. I have encountered some social researchers who took pride in adopting Foucault’s aloof, disinterested ‘gaze’ on social realities, thinking they could study them without a practical or transformative purpose, but rather as a kind of pure contemplation. Describing Foucault, Habermas writes of ‘the stoic gaze of the archaeologist’ and ‘the cynical gaze of the genealogist’ (Citation1992, p. 253; emphases in original). This disinterested gaze also has consequences in the real world: to study anything is to take a stance on what it is important to know about it – and to act on. So, it is disconcerting that Variyan and Edwards-Groves think the work of the theory is ‘replacing actuality with the virtuality of theoretical idealisations’. The charge reminds me of the pangs of regret chronicled by the poet William Butler Yeats (Citation1933, p. 392) towards the end of his life:

… it was the dream itself enchanted me

… to engross the present and dominate memory.

Players and painted stage took all my love,

and not those things that they were emblems of.

Could the authors of the theory of practice architectures have fallen prey to this trap themselves: become so infatuated with the players and painted stage of the theory that they forgot the world of history, practices, and sites in the unfolding of education and social life? I think not: the declared point of the theory of practice architectures is to help people understand and transform history, practices, and sites in the unfolding of education and social life.

Variyan and Edwards-Groves offer a commentary on the widely used (and evolving) figure that depicts the theory of practice architectures, along with the tables of invention frequently used to illustrate how key notions in the theoretical framework are manifested in empirical cases of practices and sites (arrangements, practice architectures). They argue that these figures are ‘visual meta-rationalities that mystify and reify’ (p.8) social realities and threaten to imprison researchers within the conceptual apparatus of the theory.

The tables of invention are no more than heuristics, as is made clear in various texts about the theory (e.g. Kemmis, Citation2022, Ch.8; Gibbs et al., Citation2022; Grootenboer & Edwards-Groves, Citation2023). The point of the tables is not to simply pin bits of social realities into the cells of the table as if this were to achieve something other than a particular kind of description—what Variyan and Edwards-Groves arrestingly describe as ‘dissection’ (p.8). Contrary to their view, the point of using the tables is to deliberately consider how language, time-space materialities, and social relationships are interwoven in historical social realities, in ways that produce consistent and sometimes contradictory effects, some of which include untoward consequences for different people and groups.

The point of the tables is not to ‘trap’ realities in cages formed by tables of invention – that is, simply to represent them – but rather to allow us to say something else about the world – something substantive about the nature of the social-historical empirical realities we are studying that will be critical and thus potentially transformative and, in this sense, consequential for people living in it. This is what was and is meant to make the theory of practice architectures ‘dangerous’ in the way Hopwood (Citation2021) described it – the phrase Variyan and Edwards-Groves echo in the title of their article. This transformative aim is also echoed in the deliberately immodest subtitle of Kemmis’s (Citation2022) Transforming Practices: Changing the world with the theory of practice architectures.

In short, the point of using tables of invention is not just to describe social realities, including practices and the conditions that make them possible, to leave them ‘formulated, sprawling on a pin, … pinned and wriggling on the wall’, to use Eliot’s (Citation1961, p. 13) phrase. The point is to explore their happeningness, their world-historical significances, and their consequences – for better and worse – to imagine how things might be otherwise, and to bring transformed histories into being.

A transformational resource or a resource that cannot be transformed?

Variyan and Edwards-Groves worry that somehow the theory of practice architectures has acquired a stolid solidity, a kind of ossification, that threatens to make those who use it no more than indentured servants to its taxonomic imperatives. They say:

Rather than remaining a ‘work in progress’ … , the danger is that more or less iterative work will lead to the TPA framework becoming a settled ‘science’ … that can no longer see its incoherencies, becoming [what Foucault called] a ‘theoretical totalisation under the guise of “truth”’ … . This is a ‘truth’ we ourselves want to avert. (p.13)

Variyan and Edwards-Groves seem to suggest that, now that the theory has been articulated, all that remains for others that follow is to show, over and over again, how the world conforms to its vision. This happened, to some extent, with Foucault’s mid-career theoretical work, which was used by dozens of scholars to produce papers showing (‘iteratively’) how regimes of truth and technologies of power were indeed to be found everywhere, condemning people and societies to the endless reproduction of established forms of life. If this is also to be a danger for the theory of practice architectures, it may be because some people employing it do little more than to use it descriptively to show that the world is indeed interpretable in accordance with its categories. It is a troubling thought, but Variyan and Edwards-Groves are right: the theory has, indeed, sometimes been used in a limited way, which is to say, descriptively rather than critically, and without the transformative (emancipatory) intent to address and overcome conditions that make social and educational practice unreasonable, unsustainable, wasteful, harmful, unjust, or undemocratic. This is what Hopwood (Citation2021) meant when speaking of ‘making the theory of practice architectures dangerous again’.

In my reading, Variyan and Edwards-Groves have not given substance to their allegation that the theory encompasses ‘incoherencies’ (p.13) – for example, dualism or reification. I hope my earlier arguments have rebutted these claims. Nevertheless, their anxiety that the theory is becoming a ‘theoretical totalisation under the guise of “truth”’ is, on its face, disturbing. Variyan and Edwards-Groves worry that, unlike them, the inaugurators and users of the theory will lose the critical capacity to review and renew the theory’s foundations. Yet they also acknowledge (p.7) that precisely this kind of work has been and is in fact going on. For example, after working with the theory for about 10 years, Kemmis et al. (Citation2017, p. 239), in their review of ‘how the theory of practice architectures is travelling’, outlined the topics addressed in their chapter:

The chapter (1) clarifies some key terms in the theory including (a) the relationship between practices and practice architectures, (b) the ideas of ‘enabling’ and ‘constraining’, and (c) the relationship between the theory of practice architectures and the theory of ecologies of practices. The chapter also addresses (2) the ubiquity of contestation and variation in the formation, conduct, reproduction, and transformation of practices and practice architectures to dispel the perception of ‘seamless’ harmony between practices and the practice architectures that sustain them. It examines (3) the question of agency and how it is evident in the formation and conduct of practices. Finally, the chapter addresses (4) the centrality to the theory of the notion of intersubjective spaces.

Contrary to the view of Variyan and Edwards-Groves, then, it can reasonably be asserted that core concepts in the theory have indeed been revisited, reviewed, and renewed over the years, especially in the light of emerging empirical work and contemporary theoretical debates and conversations. Later publications (e.g. Kemmis, Citation2022; Wilkinson, Citation2021, on affect and emotions; and Grootenboer & Edwards-Groves on researching with the theory) also show that the evolutionary process continues.

Conclusion

We are fully aware of the difficulty of attempting to re-invigorate theory, but also the risks involved in confronting the past. This paper’s paradoxical task, to pay homage to this past by destabilising it, runs the risk of offending those on whose shoulders we stand. However, our purpose here is not to criticise others who have historically contributed to the development of TPA, nor to simply attack the theory for its shortcomings. Instead, our hope is that we have destabilised it sufficiently to loosen its grip on our rationalities, so as to create a foyer to think otherwise; to indeed strengthen the theory by provoking scholarly critique about its merit and utility in contemporary research, and its transformative aspirations. (Variyan & Edwards-Groves, Citation2024, p. 14)

In their conclusion, Variyan and Edwards-Groves comment on ‘the difficulty of reinvigorating the theory’. For a brief moment, I saw it through their eyes as a beached whale panting its last breaths on the sand. And then they speak of ‘the risks of confronting the past’ – imagining it must be hard to confront years of constructing a theory that may be misguided, if not false. Yet I cannot see the theory as beached in that way, nor believe that the authors of the theory are paralysed by ‘the risks of confronting the past’. Indeed, they have worked over many years to extend and refine the theory as a way to explore, understand, and critically transform education and social life. Variyan and Edwards-Groves say their purpose is not ‘to attack the theory for its shortcomings … but to loosen its grip on our rationalities [so we can] … think otherwise’ (p.14). Surely, they exaggerate when they say that the theory has come to have such a vice-like ‘grip on our rationalities’. Surely, they cannot believe that the real danger of the theory is that it has become a kind of Orwellian ‘Newspeak’ (Orwell, Citation1949).

In their article, Variyan and Edwards-Groves have not demonstrated any substantive shortcomings in the theory; rather, the article suggests that they have alternative understandings of some of its key ideas, like its dialectical – not dualistic – understanding of the relationship between the individual and the social, and (separately) between practices and practice architectures. Likewise, they construe the theory as operating with a ‘two-tier’ (p.8) view of social reality, rather than succeeding in achieving a flat ontology that offers insights into human action, agency, and practices without recourse to reified notions of social structures. And they do not acknowledge that or how the theory offers resources that reach beyond description and analysis to provide resources for critique and for transformations of social and educational life.

The problems and issues Variyan and Edwards-Groves discuss have been discussed, reviewed, and renewed throughout the evolution of the theory, as the literature of the theory shows. Their article offers no insights about how to theorise social life otherwise. They make no specific critiques of any empirical work or findings that would demand reconceptualization of the theory’s key ideas or the research practices of those who use it. They do, however, use a particular kind of social theory – Foucault’s genealogy – to offer a view of the theory of practice architectures from without. Does this mean that Variyan and Edwards-Groves view Foucault’s theoretical categories as a more (epistemologically? ontologically?) secure platform from which to view the theory of practice architectures? They do not say. Or is the Foucauldian gaze just another possible view of social life and practice – like the theory of practice architectures?

In my view, Variyan and Edwards-Groves have not shown a better or alternative way ‘to think otherwise’ (p.14) or to recast key ideas of the theory of practice architectures. They offer little evidence of and no remedies for its alleged shortcomings. It seems to me, therefore, that their criticism is a sceptical rather than a critical response to the theory.

Perhaps their article is a Foucauldian reminder that all social theorists – like the researchers involved in developing the theory of practice architectures – need to beware of the dangers of becoming prisoners in the cages of their own theories, or unthinking purveyors of past ideas that may, over time, lose their capacity to grasp and transform semantic, material, and social realities and histories. Theorists in every field have this enduring task and responsibility – to explore where, and when, and how their theoretical categories might be losing their edge, not just that they might do – like all theories, which are inevitably fallible, frail, and sometimes frayed creatures of their times, their locations, and the authors that animate and sustain them. In the Archaeology of Knowledge, Foucault (Citation1969/1972 exemplified this reflexivity when he reflected on his own grasp – ‘so precarious and so unsure’ (p.17) – of ‘genesis, history, development’ (p.16) as he ‘tried to define the blank space from which I speak’ (p.17). Variyan and Edwards-Groves may have directed their warning to researchers in the research community of the theory of practice architectures, but it is a warning for theorists in any and every school of social theory.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen Kemmis

Stephen Kemmis is Professor Emeritus of Federation University, and of Charles Sturt University, Australia. He studies the nature and change of practices, principally in education, through the lens of the theory of practice architectures. He writes on education, critical participatory action research, higher education development, approaches to research, and Indigenous education.

Notes

1. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewer who pointed out that, in their experience, the figures representing the theory sometimes miscue readers, leading to dualistic misunderstandings – partly, as they said, ‘as a fault of English language and our enculturation in dualistic thinking’.

2. Note that Variyan and Edwards-Groves refer to ‘Grootenboer & Edwards-Groves Citation2023’ although the year of publication was 2023.

References

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press.

- Burgess, C., Grice, C., & Wood, J. (2023). Leading by listening: Why aboriginal voices matter in creating a world worth living in. Ch.7. In K. Reimer, M. Kaukko, S. Windsor, K. Mahon & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Living well in a world worth living in for all - volume 1: Current practices of social justice, sustainability and wellbeing (pp. 115–136). Springer. (Open access). https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-19-7985-9

- Eliot, T. S. (1961). The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Selected poems. Faber.

- Foucault, M. (1961/1967). Madness and civilisation: A history of insanity in the age of reason. Tavistock (Librairie Plon).

- Foucault, M. (1966/1970). The order of things: An archaeology of the human sciences. Tavistock (Gallimard).

- Foucault, M. (1969/1972). The archaeology of knowledge (A.M. Sheridan Smith, Trans.). Tavistock (Gallimard).

- Foucault, M. (1975/1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Vintage (/Gallimard).

- Foucault, M. (1977). Language, counter-memory, practice: Selected essays and interviews (D. F. Bouchard, Ed.). Cornell University Press.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977 (C. Gordon, Ed.). Harvester.

- Gibbs, L., Cooke, M., & Salamon, A. (2022). Unpacking the theory of practice architectures for research in early childhood education. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 47(4), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/18369391221119834

- Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems of social theory: Action, structure and contradiction in social analysis. Macmillan.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity.

- Grootenboer, P., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2023). The theory of practice architectures: Researching practices. Springer.

- Habermas, J. (1972). Knowledge and human interests (J.J. Schapiro, Trans.). Heinemann.

- Habermas, J. (1974). Theory and practice (J. Viertel, Trans.). Heinemann.

- Habermas, J. (1987). Theory of communicative action, volume II: Lifeworld and system: A critique of functionalist reason. In T. McCarthy. Beacon.

- Habermas, J. (1992). The philosophical discourse of modernity: Twelve lectures (F.G. Lawrence, Trans.). MIT Press.

- Hadot, P. (1995). Philosophy as a way of life (M. Chase, Trans.). Blackwell.

- Hopwood, N. (2021). From response and adaptation to learning, agency and contribution: Making the theory of practice architectures dangerous. Journal of Praxis in Higher Education, 3(1), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.47989/kpdc114

- Hopwood, N., Blomberg, M., Dahlberg, J., & Abrandt Dahlgren, M. (2022). How professional education can foster praxis and critical praxis: An example of changing practice in healthcare. Vocations and Learning, 15(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-021-09277-1

- Kemmis, S. (2019). A practice sensibility: An invitation to the theory of practice architectures. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9539-1.

- Kemmis, S. (2022). Transforming practices: Changing the world with the theory of practice architectures. Springer.

- Kemmis, S., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2018). Understanding education: History, politics, practice. Springer.

- Kemmis, S., & Grootenboer, P. (2008). Situating praxis in practice: Practice architectures and the cultural, social and material conditions for practice. Chapter 3. In S. Kemmis & T. J. Smith (Eds.), Enabling praxis: Challenges for education (pp. 37–64). Sense Publishers.

- Kemmis, S., & Hopwood, N. (2022). Connective enactment and collective accomplishment in professional practices. Professions & Professionalism, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.4780

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2017). Roads not travelled, roads ahead: How the theory of practice architectures Is travelling. Ch.14. In K. Mahon, S. Francisco, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Exploring education and professional practice: Through the lens of the theory of practice architectures (pp. 239–256). Springer.

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Springer.

- Larrain, J. (1979). The concept of ideology. Hutchinson.

- Lefebvre, H. (1947/1991). Critique de la vie quotidienne [Critique of Everyday Life] (J. Moore, Trans., Vol. 1). Grasset. English edition. Verso.

- Lefebvre, H. (2005). Critique of everyday life (G. Elliott, Trans., Vol. 3). Verso.

- Mahon, K., Heikkinen, H., Huttunen, R., Boyle, T., & Sjølie, E. (2020). What is educational praxis? Ch. 2. In K. Mahon, C. Edwards-Groves, S. Francisco, M. Kaukko, S. Kemmis, & K. Petrie (Eds.), Pedagogy, education, and praxis in critical times (pp. 15–38). Springer.

- Nicolini, D. (2017). Is small the only beautiful? Making sense of ‘large phenomena’ from a practice-based perspective. Ch.7. In A. Hui, T. Schatzki, & E. Shove (Eds.), The nexus of practices: Connections, constellations, practitioners (pp. 98–113). Routledge.

- Orwell, G. (1949). Nineteen Eighty-four. Secker & Warburg.

- Ross, K. (2023). The politics and poetics of everyday life. Verso.

- Russell, B. (1961). History of western philosophy (2nd Ed). George Allen & Unwin.

- Schatzki, T. R. (1994). Practices and actions: A Wittgensteinian critique of Bourdieu and Giddens. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 27(3), 283–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/004839319702700301

- Schatzki, T. R. (1996). Social practices: A Wittgensteinian approach to human activity and the social. Cambridge University Press.

- Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Schatzki, T. R. (2003). A new societist social ontology. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 33(2), 147–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393103033002002

- Schatzki, T. R. (2005). The sites of organizations. Organization Studies, 26(3), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050876

- Schatzki, T. R. (2012). A primer on practices: Theory and research. Ch.2. In J. Higgs, R. Barnett, S. Billett, M. Hutchings, & F. Trede (Eds.), Practice-based education: Perspectives and strategies (pp. 13–26). Sense.

- Thelin, K. (2024). What about feelings? Elaboration on and consideration of the theoretical construct of emotions in practice and practice architectures. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2024.2334879

- Variyan, G., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2024). The theory of practice architectures and its discontents: Disturbing received wisdom to make it dangerous again. Critical Studies in Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2024.2334779

- Wilkinson, J. (2021). Educational leadership through a practice lens: Practice matters. Springer.

- Yeats, W. B. (1933). The circus animals’ desertion. In R. J. Finneran (Ed.), The poems of W. B. Yeats: A new edition. Macmillan.

- Zedong, M. (1937/1971). On contradiction. In Selected readings from the works of Mao Tsetung (pp. 85–133). Foreign Languages Press.