ABSTRACT

This research aims to assess the organisational readiness and maturity of continuous improvement (CI) deployment in a medical device manufacturer. A single case study approach was used, in an Irish medical device company with 500 indirect staff members. The data were collected through a quantitative survey, and results were used to provide practical measures and assessment of readiness and inform the future development of the CI initiative. This case study demonstrates that CI deployment practice is consistent with literature findings and that employee motivation, employee empowerment and employee knowledge, management commitment, CI linked to strategy and communication of CI strategy are all key enablers for sustained CI deployment and success. Despite being within a highly regulated industry, there was an overall positive culture of acceptance and embracing of CI methods and initiatives within this organisation. The study presents a practical approach to assessing organisational readiness and maturity for CI to identify areas of strength that can be used as cornerstones of an initiative and areas that would benefit from further development prior to implementation.

1. Introduction

Continuous Improvement (CI) is ‘a company‐wide process of focused and continuous incremental innovation’ (Bessant, Caffyn, Gilbert, Harding, & Webb, Citation1994). Over the past decades, CI has been studied from many perspectives. Many studies have been focused on growing interest around the broader application of continuous improvement methodologies concerning success and failure factors (Albliwi, Antony, Abdul Halim Lim, & van der Wiele, Citation2014; McLean & Antony, Citation2014; Sony, Naik, & Therisa, Citation2019). Several studies have also focused on the sustainability of CI programs and the readiness factors and maturity of CI programs, increasing benefits realised and increasing the likelihood of sustaining continuous improvement initiatives (Antony, Gupta, Sunder, & Gijo, Citation2018; Antony, Krishan, Cullen, & Kumar, Citation2012; Manville, Greatbanks, Krishnasamy, Parker, & Antony, Citation2012; Schönsleben, Friemann, & Rippel, Citation2016; Yaduvanshi & Sharma, Citation2017). Readiness has been conceptualised as either a state or a process (Dalton & Gottlieb, Citation2003).

Research interest in this area has crossed industry sectors and included manufacturing (Desai, Antony, & Patel, Citation2012), services sector (healthcare, financial) and public sectors (Antony, Downey‐Ennis, Antony, Seow, & Bowerman, Citation2007; Juliani & Oliveira, Citation2019). However, there have not been many studies on organisational readiness for CI within the medical device sector, which is a highly regulated one (Brown, Eatock, Dixon, Meenan, & Anderson, Citation2008). Recent research by McDermott et al., (Citation2022) and McDermott et. al., (Citation2022) on CSF’s for CI within the Irish pharmaceutical and medical device sectors have highlighted the highly regulated nature of the industry as an additional barrier to CI deployment and success.

A case study of an Irish medical device manufacturer with a currently active continuous improvement (CI) initiative for over 5 years is presented. The medical technology (MedTech) sector in Ireland is recognised as one of the five global emerging hubs. The sector employs more than 40,000 people in Ireland and is the second-largest per capita employer of medical and technology professionals in Europe. In addition, 9 of the world’s top 10 medical technology companies have a base in Ireland (Irish Medtech Association, Citation2020). Through this study, the case study in a medical device manufacturing organisation sought to understand its current implementation status, its readiness for embracing CI. The intention is to incorporate this knowledge and assessment into the case study organisations’ roadmap for success, improvement and sustainability.

Thus, the research hypothesis are:

What is the level of organisational readiness for CI within the case study organisation?

What are the strength and weaknesses of the current CI deployment within the case study organisation?

What are the opportunities for improvement of CI adoption and future opportunities?

This paper presents the findings from exploring the effectiveness of the readiness factors for CI with the employees. The paper concludes with practical recommendations to inform the development and further deployment of continuous improvement. An essential contribution of this research approach is the wide-scale assessment of the employee and organisational readiness before implementing a continuous improvement initiative.

2. Literature review

2.1. The medical device industry in context

There are few studies addressing the use of CI methods in Regulated industries, but the use of CI is increasing;. Brown et al. (Citation2008) found in a study that the use of strategies and tools associated with quality and continuous improvement in the medical devices sector is lower than those reported elsewhere. In the European Union and globally, medical technologies are tightly regulated by laws that govern the safety and

performance of devices across their lifetime, pre- and post-market lifecycle (Boylan, McDermott, & Kinahan, Citation2021). Medical devices range from simple Band-Aids and disposable gloves to sophisticated lifesaving products such as pacemakers and implantable facial prostheses (Centre for Drug & Radiological Health, Citation2020).

Due to the highly regulated nature of the medical device industry, changes that may affect product functionality and safety may involve regulatory submissions to regulatory bodies if these changes impact product safety or compliance to the quality management system. Regulatory hurdles are a well-recognised bottleneck in time and cost for medical device manufacturers (Bayon et al., Citation2016; McDermott et al., Citation2022).

2.2. Readiness factors for continuous improvement

One of the significant reasons for organisational failure to transform through continuous improvement is the failure to assess readiness before starting the journey (Dalton & Gottlieb, Citation2003; Rodgers, Anthony, & Cudney, Citation2021). Readiness is very closely dependent on and related to the people within the organisation (Douglas, Muturi, Douglas, & Ochieng, Citation2017).

Literature reviews of both success factors and failure factors have been analysed and summarised the key areas where satisfactory results will positively support organisational performance. A summary of these factors is provided in . Within the critical success factors identified, common themes like management commitment and support, clear communication, providing key resources and training, a positive organisational culture were identified (Antony et al., Citation2012; Antony & Snee, Citation2010). On the other hand, there were many CFF’s identified, which was identified as a lack of focus, support, resources, and basically poor organisational readiness (Albliwi et al., Citation2014).

Table 1.. Critical success factors and critical failure factors.

The research recognises that within success and failure factors, there is a potential impact of organisational culture, communication, and understanding of the methodology and the associated tools integrated into the methodology. Accordingly, the suggestion that organisations should seek to understand the internal climate and culture before introducing and deploying continuous improvement (Antony, Citation2014) is appropriate.

Readiness factors have been defined as ‘essential ingredients which will increase the probability of success of any CI initiative before an organisation invests its resources heavily on the initiative’ (Antony, Citation2014; Antony et al., Citation2019; Van den Bergh, Hohl, De Geyter, Stalberg, & Limoni, Citation2005; Lim & Antony, Citation2019). Jung, Kulvatunyou, Choi, and Brundage (Citation2016) highlighted how manufacturers have trouble making improvements and with readiness for improvement. The readiness factors identified within the literature are presented in .

Table 2. Organisational readiness factors for CI.

The importance of Leadership commitment across different CI models is noted by many authors (Antony, Citation2014; Douglas, Citation2017; Kumar et. al., 2020). Leaders that can practice continuous improvement themselves will demonstrate that from the top down the benefits of the process are supported and will help create a culture of continuous improvement among employees (Kumar & Sharma, 2015). Employee motivation is fostered by investing in time to train, encouraging participation and having reward improvements. All of these increase employee and team engagement in the CI process and will encourage a positive relationship between all streams in an organization (Antony, Citation2014). The business strategic needs with respect to CI activities need to be aligned with customer focus which will help to train employees in strategic learning, planning and goal setting and will help employees to understand the differences between operational and strategic goals (Alnadi & McLaughlin, 2021).

Appropriate training and coaching will empower individuals and, if provided with the supporting structures, will enable problem solving and improvement (McDermott et al., Citation2022; Kumar & Sharma, 2017). Effective and honest communication regarding the aims of a CI activity and the associated benefits to everyone in an organization helps to build trust, provides information and ultimately empowers employees to sustain the CI activity (Brown et al., Citation2008; Iyede et al., Citation2018). The method of communication can vary based on audience and information to be presented but needs to be informative to all regarding activity status and purpose (Alnadi & McLaughlin, 2021).

Common elements can be seen across the research in different sectors as shown in and compared to the success and failure factors presented in from the respective literature reviews. These common elements have been applied within the questionnaire design for this research as presented within the next section on methodology.

There are common factors around leadership, training and development, employee empowerment, and employee motivation as the ingredients of a CI initiative and leverages a model from a previous study by Rodgers et al. (Citation2021). There is a need to assess the readiness factors around leadership vision, links to strategy, management commitment, and appropriate resources as precursors to and measures of CI deployment. For successful implementation, an organisation must understand the success factors and failure factors as part of the design and implementation of a CI deployment to increase the likelihood of sustaining the initiative within the organisation.

3. Research methodology

The case study approach is most suitable for an empirical study when there is scarce body of knowledge on the subject (Yin, Citation2016) as there is in the case of literature related to CI within the Medical Device area (Brown et al., Citation2008; Iyede et al., Citation2018; McDermott et al., Citation2022). It is most suitable when information is about the phenomenon is not enough to draw hypothesis (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). It further helps to understand the dynamics present within the present contextual setting for better understanding of the phenomenon (Dubé & Paré, Citation2003) .

In this instance, the level of organizational readiness, strength and weakness of CI, opportunities in medical device manufacturer are an understudied phenomenon, as such case approach was used. In addition, a single case study approach is most suitable if the phenomenon under investigation is unique, critical, and revelatory (Dubé & Paré, Citation2003).

This research was undertaken in a medical device manufacturing organisation. The case was critically chosen because it was revelatory (Dubé & Paré, Citation2003) as the case study organisation is an Irish-based medical device manufacturer who started its CI journey 5 years ago. The organisation employs just under 500 support personnel and has requested to remain anonymous. The research objectives of this study were 1. What is the level of organisational readiness for CI within the case study organisation?; 2. What are the strength and weaknesses of the current CI deployment within the case study organisation? and 3. What are the opportunities for improvement of CI adoption and future opportunities?

A quantitative survey was utilised to help to answer these questions based on themes drawn from the literature. The survey was distributed to all functions within the organisation so that the researchers could get a valid representation of the organisational readiness for CI as a whole and not just one function in isolation.

Thus, many different functions within the medical device organisation participated in the study to aid gathering of data on readiness for CI. The survey questions were validated by first disseminating and piloting the survey to random group of professionals working in the medical device company under study, as well as with a sample of professions from over device organisations and also to a group of CI professionals (Marshall, Citation2005; Shafiq & Soratana, Citation2020). Any observations or comments in relation to the survey questions and themes were taken on board and the survey was rewritten to include this feedback (Ball, Citation2019). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha approach was used to compute the internal consistency of the measuring instrument. The Cronbach alpha of the questionnaire was found to be 0.789. If the alpha coefficient is larger than 0.7, the questionnaire has agreeable reliability (Nunnally, Citation1994).

A purposive approach and total population sampling method were applied (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, Citation2015). The authors utilised an online survey which was distributed for data collection targeted at professionals working within the medical device organisation under study. Online surveys aid the expedition of responses collection within a relatively short time frame.

The survey was made available to all employees via company-wide and departmental email communications for 2 weeks using a link to the survey via Microsoft Forms. In total, 19 questions were developed that focused on themes such as linking continuous improvement with organisational strategy, employee motivation, and employee empowerment (see Appendix 1). The questions were based on ascertaining organisational readiness for CI based on themes identified during the literature review ().

Table 3. The survey questions with the CSF’s being measured under each question.

As most of the issues related to employees’ attitudes and perceptions, the questionnaire was developed using Likert scales (Swarnakar et al., Citation2020). A final question specifically asked if operating in a highly regulated environment such as medical devices subject to stringent regulations by regulatory authorities can act as a barrier to Continuous Improvement. Other studies by McDermott et al., (Citation2022) and McDermott et al., (Citation2022) found that regulations and compliance to regulations was deemed to be a barrier and CFF’s for CI program deployment in the Irish Medical device and Pharmaceutical industries.

4. Results

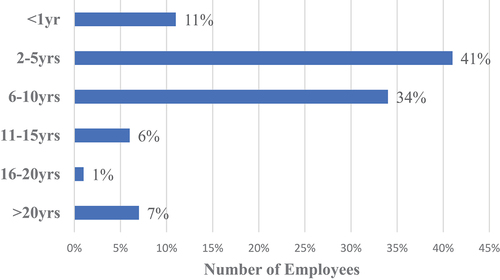

A total of 103 responses from 450 employees who work within the case study organisation were received (approx. 23% response rate). This response rate is satisfactory according to Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, and Jackson (Citation2012). The number of years of experience of the respondents is provided in .

Forty-one percent stated that their length of experience is between 2 and 5 years, while 34% stated their experience was between 6 and 10 years. This organisation would not be considered one with an exceptionally high length of service, as perhaps there would be in some public sector organisations where there is less movement across the sector (Rodgers et al., Citation2021).

Respondents were asked to list what function they were from, as outlined in . Thus, the top % of respondents were from the Manufacturing, Manufacturing Engineering, Regulatory departments, R&D and Operations Quality functions in that order.

The presentation of the data is structured under six broad themes drawn from the literature on readiness factors for implementing continuous improvement and which slightly overlapped. This is supplemented with a summary of the areas identified for improvement by the employees themselves and again linked to the broader literature around success, failure, and readiness factors. The detailed analysis plan is delineated in .

4.1. Employee perspectives on organisations current approach to CI

Respondents were asked whether CI was currently a priority within the organisation. In addition, respondents were asked whether CI as part of the corporate strategy and then, if so, whether the priority was clearly communicated throughout the organisation. CI is one of the goals of our overall organisation strategy had a very high ‘strongly agree’ response of 56% and an ‘agree’ response of 33%. The remaining three Likert categories were just 10% combined. The mean was found to be 4.38 and the coefficient of variation was found to be 20.24%. The coefficient of variation of less than 40% is indicating most respondents have consensus that CI is one of the goals of our overall organisation strategy (; Bytyqi & Hasani, Citation2010; Saad & Ali, Citation2014);. This suggests that management and Leadership are doing an excellent job in communicating the value of CI within the organisation’s strategy as that there is an awareness of the importance of CI being received by employees.

In response to the statement that ‘ The organisations approach to continuous improvement is clear and is communicated to all levels throughout the business’, 26% ‘strongly agreed’ with this statement and 46% ‘agreed’. The mean value of the responses is 3.78 and coefficient of variation is 29.65% which is less than 40%. This enforces the strong positive response to the question on CI being a goal of the company’s overall strategy, but the % of ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ responses in this question being slightly lower suggest communications could be more transparent and improved.

These results are indicative of the literature on the importance of aligning CI initiatives to strategy, providing clear communication of how CI is defined, and the importance of employee education, empowerment and motivation in CI deployment (Snee & Hoerl, Citation2002). These questions were also examined by comparing them with the length of service of the respondents. The employee’s length of service was divided into two groups 0–5 years (new employees) and above 5 years (long service employees). A t-test was conducted on the mean scores of the questions across both the groups and found that there was no statistical difference (p value >0.05, ). No significant variations of views across all questions were identified; therefore, the views expressed by newer employees were consistent with longer-serving employees.

Table 4. T-test between length of service and responses.

In response to the statement ‘Continuous Improvement needs to be more regularly communicated and should appear in our strategy, plans and performance’, – 57% strongly agreed, and 28% agreed with this statement. The mean score was 4.39 and coefficient of variation of 17.98% which was less than 40%. A t-test was conducted on the mean scores of the questions across both the groups and found that there was no statistical difference (p value >0.05).

This response was surprising and somewhat contradictory, given that respondents had indicated that CI was an explicit part of the organisation’s strategy and that it was communicated. However, this response demonstrates an opportunity and a need for more regular communication.

4.2. Current awareness of CI methodologies

Employees were asked about their experience with standard CI methodologies, tools, and techniques. Employees were asked if they had received CI training. Seventy-eight percent or nearly four out of every five respondents answered that they had received training, while 22% stated they had not. This is a very positive indicator, and the previous question responses concerning CI are identified as part of the organisation’s strategy and communication.

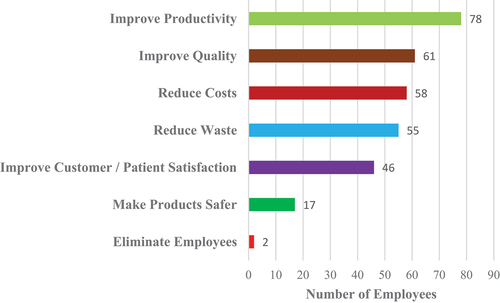

Regarding the purpose of the organisation’s CI program, () respondents were asked their opinions on the top three reasons for CI deployment and the benefits of CI within the organisation. Improving productivity was deemed the highest reason for CI deployment within the case study organisation while improving costs, quality, and reducing waste were all very closely aligned together as secondary benefits to improving productivity.

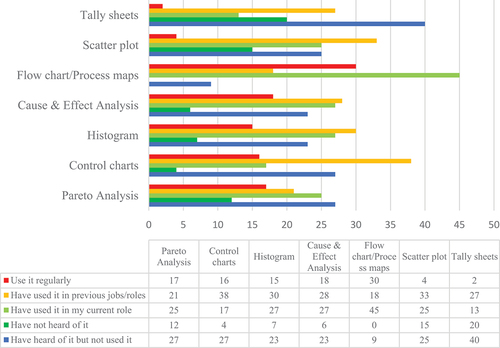

The most regularly utilised tool was 1st Flow charts (29%), 2nd Cause & Effect (18%), 3rd Pareto analysis (17%), 4th Control charts (16%) and 5th Histograms (15%). The ‘I have used it in a previous role/job’ yielded a somewhat different ranking of tools with 1st Control charts (37%), 2nd Scatter plots (32%) and 3rd Tally sheets (29%) featuring in the top 3 most utilised tools. Within the ‘I have used the tools in my current role’ category, the ranking of most utilised tools were 1st Process flow (44%), 2nd Cause & Effect and Histograms (both 26%), 3rd Pareto analysis & Scatter plots (both 25%). A negligible number of respondents (mean average of 9%) indicated they had never heard of the tools presented, with 0% stating they had not heard of process mapping ().

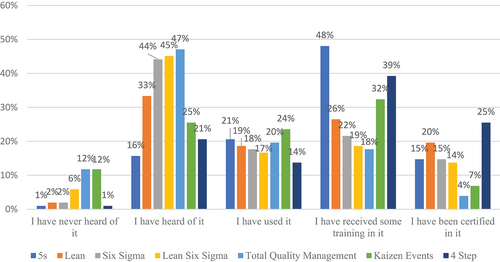

Respondents were asked, ‘Which of the following Continuous Improvement methodologies or approaches have you used or know are used in the organisation?’. Several CI methods were put forward; 5S, Lean, Six Sigma, Lean Six Sigma (LSS), Total Quality Management (TQM), Kaizen events and 4 Step. The top CI methods in terms of combined usage, recognition, and training were 1st 5S (83%), 4 step (78%), Lean (65%), Kaizen events (63%), Six Sigma (54%) and LSS (49%). The lowest-ranked CI method was TQM at just 41% combined usage, recognition and training. Only an overall average of 5% of the respondents stated they have never heard of the CI methods listed. There is an opportunity to move the 33% who had ‘heard of the methods’ into a ‘use’ and ‘certified’ category and perhaps increase the use and certified %.

Within the “I have been certified in it “ category () 4 Step, and Lean was ranked the highest, In the ‘I have received some training in it’ category, the ranking was as follows: 1st 5S (48%), 2nd 4 step (39%), 3rd Kaizen events (32%), 4th Lean (26%), 5th Six Sigma (22%), 6th LSS (19%) and 7th TQM (18%). These figures are positive in the sense that an average of 1 in 2 respondents had trained in 5S usage, and a high 64% of respondents had been certified and received training in the 4 Step process. Within a CI program converting training into actual usage and deployment opportunities can be a challenge. Awareness of CI was measured very highly, with TQM (47%), LSS (45%) and six sigma (44%) coming in as the top 3 ranked CI methods recognised in this question.

Only a very minor 5% of respondents stating that they had not heard of these methods. However, a sizeable 33% have not used CI methods. The success and failure factors for CI indicate that training is important (Albliwi et al., Citation2014; McLean & Antony, Citation2014), and this organisation is strong in this area. However, an identified gap in employee application and deployment after training should be investigated to further the CI initiative.

The question on ‘The organisation has a CI team or CI champions’ yielded a response of 34%, indicating that ‘I know them and have spoken to them about CI’. A vast majority (66%) of respondents had not engaged with their CI team based on their answers concerned as suggested these employees were potentially not engaged in CI.

4.3. Employee motivation

A majority (70%) of the respondents stated that they ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ with the statement that they regularly suggested improvements to their manager. The mean score was 4.02 and coefficient of variation was 23.43% indicating consensus on the statement. A further majority (70%) felt that it was part of their role to suggest improvements.

The responses suggest that the employees currently see CI as part of their role and a substantial number are already active in making suggestions for improvements. In addition, 77% of respondents either ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that, currently, their line manager supported them to implement improvements. The mean score was 3.92 and coefficient of variation was 25.91% indicating consensus on the statement. This result is in line with the need for management support for successful CI initiatives (Antony, Citation2014). The fundamental challenge can be summarised as staff lacking the knowledge and skills to participate in CI and suggest and improve effectiveness. This response somewhat contradicts the previous two questions on line management supporting CI improvement suggestions and that when improvements are suggested, management listens and help implement changes.

4.4. Employee empowerment

When asked if respondents felt empowered to make small changes and improvements within their roles – 47% ‘strongly agreed’ and 43% ‘agreed’ with this statement. As only 5% of respondents ‘strongly disagreed’ and ‘disagreed’ that they felt empowered, the length of employment within the organisation was not considered a factor in empowerment. The mean score was 4.27 and coefficient of variation was 21.29% indicating consensus on the statement.

This response is balanced and positively correlated with the previously stated level of knowledge and training that would support empowerment to deliver and optimise actual benefits. A positive critical aspect for introducing a CI initiative within the organisation is that employees with 1–5 years of experience and those with 6–10 years of experience feel equally empowered to make changes as shorter duration employees. This suggests that the culture around trust and empowerment is pervasive and a long-standing positive element of the relationships between leaders, managers, and employees.

Another question on ‘There needs to be more information on how I can get involved and receive training or information on making improvements’ -yielded a ‘strongly agree’ response of 23% and an ‘agree’ response of 41%. The mean score was 3.68 and coefficient of variation was 28.66% indicating consensus on the statement. As 77% of respondents received CI training, this question is somewhat contradictory. Interestingly, most respondents who strongly disagreed with this statement were from support functions outside of manufacturing such as Regulatory, HR, Supply chain, and R&D.

4.5. Organisational culture readiness

Some of the previous questions on the survey touched on aspects of organisational culture readiness for CI, such as employee motivation, knowledge, management support and training. However, a specific question on ‘Do you think that operating in a highly regulated environment can stifle Continuous Improvement or act as a barrier to Continuous Improvement?’ was asked to see if a highly regulated environment was a barrier to CI culture. Medical devices range from simple Band-Aids and disposable gloves to sophisticated lifesaving products such as pacemakers and implantable facial prostheses (CDRH, Citation2020).

The higher the classification of a device, the higher the risk and therefore the more significant the regulatory controls required. Any CI changes that would affect product safety may result in submissions to regulatory authorities for approval of that change and may require process validation (Byrne, McDermott, & Noonan, Citation2021; McDermott et al., Citation2022; McDermott et al., Citation2022). All of the changes mentioned above take time and can cause an extra regulatory burden.

However, only 27% of respondents ‘strongly agreed’ and ‘agreed’ with this statement, with a sizeable 49% of respondents ‘strongly disagreeing’ and ‘disagreeing’. The mean score was 2.66 and coefficient of variation was 46.13%, which is above 40% indicating respondents were not consenting to the statement (; Saad & Ali, Citation2014). Seventy-eight percent of the respondents had been trained in CI, the fact that 23% and 41% ‘strongly agreed’ and ‘agreed’ that they need more training in CI and making improvements. This suggests that these respondents may not be involved enough in CI programs to understand potential regulatory barriers to CI accurately.

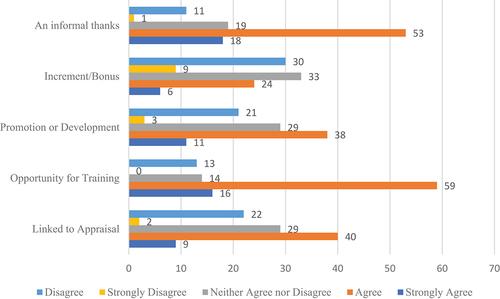

4.6. Employee reward

The following was ranked as the rewards for CI efforts: 1. An informal thanks, 2. Opportunity for training, 3. Linked to promotion/development, 4. Linked to appraisal and 5. Increment/bonus in order of the ‘strongly agree’ rankings.

The culture of ‘Informal thanks ’ within this organisation was very positive, with 18% and 52% ‘strongly agreeing’ and ‘agreeing’ that informal thanks recognised CI efforts. The mean score was 3.74 and coefficient of variation was 24.13% indicating consensus on the statement. The fact that only 1% of respondents ‘strongly disagreed’ that they received informal thanks for their CI efforts demonstrates a very positive culture and supportive management culture for CI within this organisation. The ‘opportunity for training’ as a reward for CI effort was also deemed very positively by respondents with 16% and 58% (74% combined) ‘strongly agreeing’ and ‘agreeing’ that there was an opportunity for training. The mean score was 3.75 and coefficient of variation was 23.11% indicating consensus on the statement.

‘CI efforts rewarded by links to promotion or development’ was the 2nd lowest ranked in terms of the CI rewards listed but still had an 11% and 37% ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ response. The mean score was 3.31 and coefficient of variation was 30.8% indicating consensus on the statement.

In terms of ‘CI efforts being linked to appraisal’, 9% and 39% ‘strongly agreed’ and ‘agreed’ that CI efforts were linked to appraisal, with 28% neither agreeing nor disagreeing and 22% disagreeing. The mean score was 3.31 and coefficient of variation was 30.8% indicating consensus on the statement.

A reward for CI linked to ‘increment/bonus’ had the lowest ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ ratings of 6% and 24%, respectively, with over 9% and 29% ‘disagreeing’ and ‘strongly disagreeing’ that increment/bonus increases were a reward for CI effort. The mean score was 2.70 and coefficient of variation was 43.44%, which is above 40% indicating respondents were not consenting to the statement (; Saad & Ali, Citation2014).

It is noted that there was a sizeable 32%, 28% and 28% neither ‘agree nor disagree’ votes for increment/bonus, promotion/development and linked to appraisal, respectively, for this question (see ). This suggests that many respondents either do not see CI efforts rewarded either way or are perhaps not close enough to the CI program and involved enough to feel they can answer.

5. Discussion

In line with the first research hypothesis to ascertain the level of organisational readiness for CI within the case study organisation, the research overall suggested a very strong readiness level for CI within the organisation. The analysis of the employee’s responses suggests that there are several readiness factors where there was consensus that they are prepared for further CI implementation initiative and have a solid adoption of CI methods. The employees rated the following readiness factors: Leadership & management commitment, employee motivation, employee knowledge, organisational strategy, and communication.

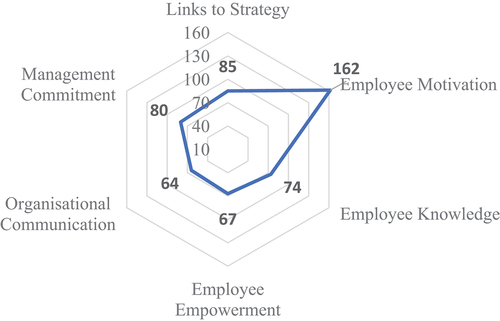

The second research hypothesis to ascertain the strength and weaknesses of the current CI deployment within the case study organisation demonstrated there were more strengths than weakness in the CI deployment. There are several factors where employees perceived a need for improvement before further CI deployment and as part of the current CI implementation. The positive responses covering the key readiness factors from the Likert scale questions (completely agree and slightly agree) were combined with the negative responses (completely disagree and slightly disagree). There was a high net positive response across all readiness categories in this organisation, with employee motivation ranking as the highest readiness factor. The net responses are summarised in the polar diagram shown in .

Polar diagrams are useful for capturing visually readiness factors in various studies (Jung et al., Citation2016). This overview was intended to provide a visible and accessible summary for both employees and leaders of the CI initiative as to the strengths built on and what areas needed to be addressed explicitly as part of the continued CI deployment.

The analysis suggests that employees see the organisations’ robust approach to CI and the strong links to corporate strategy. In addition, employees feel very empowered to make improvements within the organisation. Employees also indicated that they are strongly motivated to participate in the proposed CI initiative and feel supported by the commitment of managers. While the employees feel motivated, perhaps internal communication could be improved although it is strong, it is ranked the lowest of the mean values for readiness factors.

The fact that the readiness factors were perceived so well and highly is perhaps not surprising given the context that the CI initiative has been in operation for over 5 years. The analysis of the readiness factors indicates to the organisation’s leaders the practical actions they can take to enhance their likelihood of success and the sustainability of the CI deployment. In terms of improvement, employees indicated that CI could be more aligned to performance and appraisal even though they feel very appreciated in their efforts daily by ‘informal thanks’ given. Also, there could be more training on how to be more actively involved in CI programs and for training to be provided about specific improvements identified.

In line with the third research hypotheses to ascertain the opportunities for improvement of CI adoption and future opportunities some gaps in CI within the organisation were identified. This finding suggests strong support for technical CI training in tools and techniques but perhaps a gap in soft skills and change management training. The fact that a more significant number of staff do not know their CI champions or have never talked to them suggests that more could be done on increasing employee involvement in CI activity. A high number of employees, while trained in CI tools, have not utilised the tools to ‘certification level’ nor in ‘day to day’ activities. More work could be done to convert the employees from the ‘trained in CI’ category to being ‘certified’ in CI and ‘using’ CI categories.

This paper has analysed previous research on Readiness factors, Critical Success Factors and Failure Factors and explored the relationship between them and the commonalities and differences in factors. Having a readiness model will contribute to the development of CI awareness that motivates organisations to adopt a CI supportive culture (Shafiq & Soratana, Citation2020). These have been used to develop a tool to gather employee perspectives on organisational readiness and present these in a format that the organisation can apply. As such, the employee feedback is used to inform the development, communication, and design of the CI initiative, meaning that employee involvement and empowerment is not just utilised in the actual improvement activity but additionally in the planning and design and increasing employee ‘ownership’ of the planned CI initiative. The importance of sustainability of an initiative is also important (Abad-Segura, Morales, Cortés-García, & Belmonte-Ureña, Citation2020). A readiness tool for CI can show how the weaknesses of a CI initiative and the requirements for a CI initiative can be used by organisations and practitioners alike to improve CI readiness action points (AL-Najem, Citation2021)

6. Conclusion

The initial research hypothesis was met in this study. The level of organisational readiness for CI within the case study organisation was identified as being very high. There were several strengths of the CI deployment in the case study organisation and only some weaknesses identified. These weaknesses are opportunities for improvement and future expansion of the CI deployment initiative.

The results indicate that the employees are highly motivated, change is considered positive, management commitment is present and communicated, and employees have a strong desire to improve their workplace and the service they provide and culturally feel that it is a part of their role. There is additionally a strong sense of empowerment to make change with the support of managers. However, this could be further enhanced by soft skills and change management training coupled with more visibility from the CI team to aid and facilitate CI projects. Further, employees have an appetite for CI linked to performance appraisal and bonuses. The results have been summarised within a polar diagram () for accessibility by the case study organisation. In addition, the data allows for further exploration underneath the broad themes in order to further assist the organisation.

This is the first application of a structured model to combine readiness, success, and failure factors for the implementation of CI initiatives within a medical device manufacturer. However, there is a clear need further to test the model beyond the single current application, and this will be undertaken as part of further research. In addition, a longitudinal study would be beneficial in exploring whether any data derived from a readiness evaluation has contributed to the success and sustainability of the CI initiative.

As the present study is exploratory in nature, further case studies may also be planned considering cases which are polar opposites than the one under consideration. This will help to compare the dimensions of readiness assessment in organizations. Another area would be conducting case studies in similar organizations to generalise the readiness dimensions in medical device industry. This will help further to develop scales for readiness factors.

Further insights can be gained from a series of semi-structured interviews with relevant people at the senior management, middle management and front-line staff levels. The findings can help managers understand organisational readiness factors that encourage successful implementation and application of CI methodology. Managers can use the readiness factors as a basis for establishing effective monitoring and self-assessment procedures for CI. Successful development of organisational readiness can be used to ensure the successful deployment of CI needed for organisational improvement.

This research method can be applied to other organisations in order to ascertain the organisational readiness for CI prior to commencing a CI initiative as well as current level of embracing of a CI initiative.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abad-Segura, E., Morales, M. E., Cortés-García, F. J., & Belmonte-Ureña, L. J. (2020). Industrial processes management for a sustainable society: Global research analysis. Processes, 8(5), undefined–undefined.

- AL-Najem, M. (2021). Investigating the factors affecting readiness for lean system adoption within Kuwaiti small and medium- sized manufacturing industries [ PHD, University of Portsmouth.]. https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/5325173/Investigating_the_factors_affecting_readiness_for_lean_system_adoption_within_Kuwaiti_small_and_medium_sized_manufacturing_industries.pdf

- Albliwi, S., Antony, J., Abdul Halim Lim, S., & van der Wiele, T. (2014). Critical failure factors of Lean Six Sigma: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 31(9), 1012–1030.

- Antony, J., Downey‐Ennis, K., Antony, F., Seow, C., & Bowerman, J. (2007). Can six sigma be the “cure” for our “ailing” NHS? Leadership in Health Services, 20(4), 242–253.

- Antony, J., & Snee, R. (2010). Leading role – Identifying the skills master black belts and black belts need to be effective leaders. Six Sigma Forum Magazine.

- Antony, J., Krishan, N., Cullen, D., & Kumar, M. (2012). Lean Six Sigma for higher education institutions (HEIs): Challenges, barriers, success factors, tools/techniques. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 61(8), 940–948.

- Antony, J. (2014). Readiness factors for the Lean Six Sigma journey in the higher education sector. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(2), 257–264.

- Antony, J., Gupta, S., Sunder, M. V., & Gijo, E. V. (2018). Ten commandments of Lean Six Sigma: A practitioners’ perspective. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67(6), 1033–1044.

- Antony, J., Sony, M., Dempsey, M., Brennan, A., Farrington, T., & Cudney, E. A. (2019). An evaluation into the limitations and emerging trends of Six Sigma: An empirical study. The TQM Journal, 31(2), 205–221.

- Ball, H. L. (2019). Conducting online surveys. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 35(3), 413–417.

- Bayon, Y., Bohner, M., Eglin, D., Procter, P., Richards, R. G., Weber, J., & Zeugolis, D. I. (2016). Innovating in the medical device industry—Challenges & opportunities ESB 2015 translational research symposium. Journal of Materials Science. Materials in Medicine, 27(9), 144.

- Bessant, J., Caffyn, S., Gilbert, J., Harding, R., & Webb, S. (1994). Rediscovering continuous Improvement. Technovation, 14(1), 17–29. https://www-sciencedirect-com.libgate.library.nuigalway.ie/science/article/pii/0166497294900671

- Boylan, B., McDermott, O., & Kinahan, N. T. (2021). Manufacturing control system development for an in vitro diagnostic product platform. Processes, 9(6), 975.

- Brown, A., Eatock, J., Dixon, D., Meenan, B. J., & Anderson, J. (2008). Quality and continuous improvement in medical device manufacturing. The TQM Journal, 20(6), 541–555.

- Byrne, B., McDermott, O., & Noonan, J. (2021). Applying Lean Six Sigma methodology to a pharmaceutical manufacturing facility: A case study. Processes, 9(3), 550.

- Bytyqi, F., & Hasani, V. (2010). Work stress, job satisfaction and organizational commitment among public employees before privatization. Undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Work-Stress%2C-Job-Satisfaction-and-Organizational-Bytyqi-Hasani/246d7ecf120b7abf4cb26ce3b483cc7c348317e1

- CDRH. (2020, October 22). Classify Your Medical Device. FDA; FDA. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/overview-device-regulation/classify-your-medical-device.

- Dalton, C. C., & Gottlieb, L. N. (2003). The concept of readiness to change. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42(2), 108–117.

- Desai, D. A., Antony, J., & Patel, M. B. (2012). An assessment of the critical success factors for six sigma implementation in Indian industries. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 61(4), 426–444.

- Douglas, J., Muturi, D., Douglas, A., & Ochieng, J. (2017). The role of organisational climate in readiness for change to Lean Six Sigma. The TQM Journal, 29(5), 666–676.

- Dubé, L., & Paré, G. (2003). Rigor in information systems positivist case research: Current practices, trends, and recommendations. MIS Quarterly, 27(4), 597–636.

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. R. (2012). Management research. Singapore: SAGE.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, S. R. (2015). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling: Science publishing group. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1). http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com.libgate.library.nuigalway.ie/journal/paperinfo?journalid=146&doi=10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Irish Medtech Association. (2020). Irish Medtech Association—IBEC (Accessed 01 02 2022). https://www.ibec.ie:443/en/Connect.and.Learn/Industries/Life.Sciences.and.Healthcare/Irish.Medtech.Association

- Iyede, R., Fallon, E. F., & Donnellan, P. (2018). An exploration of the extent of Lean Six Sigma implementation in the West of Ireland. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 9(3), 444–462.

- Juliani, F., & De.oliveira, O. J. (2019). Synergies between critical success factors of Lean Six Sigma and public values. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(15–16), 1563–1577.

- Jung, K., Kulvatunyou, B., Choi, S., & Brundage, M. P. (2016). An overview of a smart manufacturing system readiness assessment. In I. Nääs, O. Vendrametto, J. Mendes Reis, R. F. Gonçalves, M. T. Silva, G. von Cieminski, & D. Kiritsis (Eds.), Advances in production management systems. Initiatives for a sustainable world (pp. 705–712). Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-51133-7_83

- Lim, S. A., & Antony, J. (2019). Statistical process control for the food industry: A guide for practitioners and managers. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Manville, G., Greatbanks, R., Krishnasamy, R., Parker, D. W., & Antony, J. (2012). Critical success factors for Lean Six Sigma programmes: A view from middle management. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 29(1), 7–20.

- Marshall, G. (2005). The purpose, design and administration of a questionnaire for data collection. Radiography (London 1995), 11(2), 131–136.

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., Sony, M., & Daly, S. (2022). Barriers and enablers for continuous improvement methodologies within the Irish pharmaceutical industry. Processes, 10(1). doi:10.3390/pr10010073

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., Sony, M., & Healy, T. (2022). Critical failure factors for continuous improvement methodologies in the Irish medtech industry. The TQM Journal, 34(7), 18–38.

- McLean, R., & Antony, J. (2014). Why continuous improvement initiatives fail in manufacturing environments? A systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(3), 370–376.

- Nunnally, J. C. (1994). Psychometric theory 3E. New York: Tata McGraw-hill education.

- Radnor, Z. (2011). Implementing lean in health care: Making the link between the approach, readiness and sustainability. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 2, 1–12.

- Rodgers, B., Anthony, J., & Cudney, E. A. (2021). A critical evaluation of organizational readiness for continuous improvement within a UK public utility company. Public Money & Management, 1–9.

- Saad, H. E., & Ali, B. N. (2014). SHARIA-COMPLIANT HOTELS IN EGYPT: CONCEPT AND CHALLENGES. 15.

- Schönsleben, P., Friemann, F., & Rippel, M. (2016). Managing the socially sustainable global manufacturing network. In I. Nääs, O. Vendrametto, J. Mendes Reis, R. F. Gonçalves, M. T. Silva, G. von Cieminski, & D. Kiritsis (Eds.), Advances in production management systems. Initiatives for a sustainable world (pp. 884–891). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Shafiq, M., & Soratana, K. (2020). Lean readiness assessment model – A tool for humanitarian organizations’ social and economic sustainability. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 10(2), 77–99.

- Snee, R., & Hoerl, R. (2002). Leading Six Sigma: A step-by-step guide based on experience with GE and other Six Sigma companies (1st ed.). New Jersey: FT Press.

- Sony, M., Naik, S., & Therisa, K. K. (2019). Why do organizations discontinue Lean Six Sigma initiatives? International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 36(3), 420–436.

- Swarnakar, V., Singh, A. R., Antony, J., Kr Tiwari, A., Cudney, E., & Furterer, S. (2020). A multiple integrated approach for modelling critical success factors in sustainable LSS implementation. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 150, 106865.

- Trubetskaya A, Manto D and McDermott O. (2022). A Review of Lean Adoption in the Irish MedTech Industry. Processes, 10(2), 391 10.3390/pr10020391

- Van den Bergh, M., Hohl, M. K., De Geyter, C., Stalberg, A. M., & Limoni, C. (2005). Ten years of Swiss National IVF register FIVNAT-CH. Are we making progress? Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 11(5), 632–640.

- Yaduvanshi, D., & Sharma, A. (2017). Lean Six Sigma in health operations: Challenges and opportunities—‘Nirvana for operational efficiency in hospitals in a resource limited settings’. Journal of Health Management, 19(2), 203–213.

- Yin, R. (2016). Case study research design and methods (5th). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://cjpe.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/cjpe/index.php/cjpe/article/view/257.