ABSTRACT

Goal setting is one of the most frequently used mental skills in sports, and Goal Setting Theory has been the most prominent theoretical framework upon which goal setting interventions are based. The present study provides a systematic review examining how the tenets of GST have been applied to goal setting interventions in sport. A total of 27 peer-reviewed studies written in English, which implemented goal setting interventions with athletes in a sport-specific, applied (i.e. non-laboratory) context, were examined. The studies included athletes from a range of individual and team sports. The majority of these studies were characterized by their small sample size and strong focus on performance as an outcome measure. Overall, there was inconsistent application of, and mixed evidence supporting theorizing around, the goal characteristics (goal difficulty, specificity, proximity, source, and type) and moderators (ability, commitment, feedback, complexity, and resources) suggested in GST. As the first systematic review of goal setting interventions focused exclusively on athletes in applied sport contexts, the present review provides insight for athletes, coaches, sport psychology practitioners, and researchers. Applied implications and future research directions (e.g. testing individualized goal setting interventions) are provided.

Goals are ubiquitous in sports. Athletes, teams, and coaches frequently set goals to motivate themselves and improve their performance (Kingston & Wilson, Citation2009; Weinberg, Citation1994). There are various kinds of goals in sport, which can be pursued over the short- (e.g. single match) and long-term (e.g. throughout a season; Burton & Weiss, Citation2008). In high-level sport, goal attainment (or lack thereof) can be directly related to an athlete’s career success or failure (Williams, Citation2013). In sports, goal setting has been the most frequently used mental technique (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008; Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995). However, despite the prevalence of goal setting as a performance enhancement tool, there remains equivocal evidence about how coaches, athletes, and practitioners view and employ this technique (Gillham & Weiler, Citation2013; Maitland & Gervis, Citation2010). Goal setting in sport and performance is more complicated than is sometimes advised within applied recommendations (Healy et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the extent to which theories are appropriately employed by those using goal setting remains unclear. As such, the aim of the current paper is to systematically review the application of Goal Setting Theory by Locke and Latham (Citation1990, Citation2002) in the applied sport settings, and examine the extent to which the intervention studies apply relevant theoretical components.

Goal setting theory

Proposed by Locke and Latham (Citation1990, Citation2002, Citation2019), Goal Setting Theory (GST) has been the most prominent theoretical framework for goal setting interventions. GST is a theory of motivation that explains the relationship between conscious goals and task performance (Locke & Latham, Citation2002). GST was formulated based on an inductive approach examining numerous empirical studies across various domains including business, medicine, sport, and exercise (Locke & Latham, Citation2013). In GST, goals are conceptualized as an end-state which ‘an individual is trying to accomplish; it is the object or aim of an action’ (Locke et al., Citation1981). Goal setting interventions that employed GST have been shown to enhance task-related performance, and it is proposed that this effect occurs through four mechanisms (Locke & Latham, Citation2002). First, goal setting directs individuals to focus their efforts towards goal-related actions and ignore irrelevant activities. Second, goal setting energizes individuals, allowing them to invest effort in goal pursuit. Third, goals impact persistence, whereby more difficult goals result in a higher effort being invested. Finally, pursuing goals facilitates the discovery and development of task-relevant strategies.

The second fundamental posit of GST is that five goal characteristics directly impact the effect of goal setting, including goal difficulty, goal specificity, goal proximity, goal source, and goal types (Latham & Locke, Citation2007; Locke & Latham, Citation1990, Citation2002, Citation2013, Citation2019). First, more difficult (but achievable) goals lead to higher performance. Second, specific goals (e.g. ‘complete x number of pushups’) predict higher performance than vague goals (e.g. ‘do your best’). Recent reviews (e.g. Locke & Latham, Citation2019) suggest that goal difficulty and specificity likely work collaboratively and employing one alone would not necessarily result in an effective outcome. Third, setting both proximal (i.e. short-term) and distal (i.e. long-term) goals helps facilitate goal attainment, as short-term goals can be a useful indicator of progress towards an ultimate long-term goal. Fourth, goal source refers to whether a goal is self-set, participatively set, or assigned. Self-set goals are set by the goal pursuer himself or herself (e.g. an athlete who sets her own goals for a season); participatively-set goals are set together by the goal pursuer and other people related to the goal process (e.g. an athlete creates a goal collaboratively with his coach); assigned goals are goals made by the others and assigned to the goal pursuer (e.g. an athlete’s coach sets a goal for the athlete). Fifth, regarding two types of goals, performance goals are focused on the attainment of desired performance outcomes, whereas learning goals are focused on developing task-relevant strategies – the latter type of goal is suggested to be particularly relevant when learning a new task, particularly a complex one.

Another important consideration of GST pertains to the moderators that influence the relationship between goal setting and performance, which include ability, goal commitment, feedback, task complexity, and task knowledge and resources (Locke & Latham, Citation1990, Citation2002; Latham & Locke, Citation2007, Citation2013). First, individuals higher in ability (e.g. technical abilities in one’s sport to execute a task) will be more likely to achieve their goals compared to those lower in ability. Second, the effectiveness of goal setting is said to increase as people are more committed to their goals, with two key factors – self-efficacy and goal importance – influencing one’s goal commitment. Third, receiving feedback on one’s progression to goal attainment impacts the goal setting–performance effect, as it guides future direction and allocation of available resources towards a goal. Fourth, task complexity was initially proposed as a moderator for goal effect because when a task is above one’s capability, goal setting would be less effective. Fifth, goals are more likely to translate into performance when individuals have the necessary resources that are needed to complete the task.

Goal setting research in sport and exercise

Goal setting research in sport and exercise began to flourish following Locke and Latham's (Citation1985) suggestion that sport is one of the domains that could benefit most from applying GST, since the foundation of the theory is on improving task performance. However, initial reviews found that the effectiveness of goal setting in sport and exercise is not as robust as in the organizational and business settings (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995). Initially, the failure of replication in the earlier studies was attributed to methodological flaws of the intervention, which included using different instructors for different conditions (Hall & Byrne, Citation1988), failure to manipulate control groups (Locke, Citation1991), and little consideration for other important influences such as social comparison and competition (Hall & Byrne, Citation1988; Locke, Citation1991). However, Weinberg and Weigand (Citation1996) claimed the replication failure could be due to contextual differences and motivational properties of the participants in sports. For example, unlike other domains, feedback can be difficult to control as it is already inherent in sports (e.g. score, fatigue). Moreover, goal setting could have less impact in sports as the athletic populations have higher baseline levels of motivation compared to those pursuing goals in other contexts (e.g. workplaces). These sport-specific differences were suggested to be critical in achieving internal and external validity, as well as guiding practitioners with practical recommendations (Weinberg & Weigand, Citation1993, Citation1996). Another explanation concerned the low statistical power arising from small sample sizes in sports settings (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995). Indeed, Burton (Citation1994) indicated that sample sizes in sports research were generally smaller than research from business domains. Later empirical studies reflected on these shortcomings, and more recent narrative reviews with larger sample studies reported stronger support for the effectiveness of GST (Burton & Naylor, Citation2002; Burton & Weiss, Citation2008).

Despite the contributions of previous reviews, the relationship of goal characteristics and moderators suggested in GST (Locke & Latham, Citation1990, Citation2002, Citation2013) remains unclear within the context of sport. A meta-analysis by Kyllo and Landers (Citation1995) examining goal setting research from laboratory settings found that, overall, goal setting enhanced physical task performance (e.g. number of pushups a participant completes) compared to control conditions. Concerning goal difficulty, they found that among easy, moderately difficult, and very difficult goals, only moderately difficult goals had a significant effect on performance. In contrast, easy and very difficult goals demonstrated non-significant effects on performance, which somewhat contradicts the tenets of GST. Previous narrative reviews of goal setting in sport specifically (e.g. Burton & Naylor, Citation2002; Burton & Weiss, Citation2008) have also noted that only half of the empirical studies support a linear relationship between goal difficulty and performance. If a goal is unrealistically difficult, an athlete is more likely to withdraw from the goal and self-set a more realistic goal (Burton & Naylor, Citation2002).

In addition to goal difficulty, more than one-third of the empirical studies in sport contexts found that specific goals were not superior to vague or do-your-best goals in enhancing performance (Burton et al., Citation1998; Burton & Weiss, Citation2008), which contrasts the initial theorizing that specific goals should result in greater performance (Locke & Latham, Citation1985). Moreover, with regard to goal proximity, the meta-analysis by Kyllo and Landers (Citation1995) found that performance outcomes did not vary based on differences in goal proximity (defined in the review as short-term goals, long-term goals, and combined short- and long-term goals). In corroboration to those findings, Burton and Naylor (Citation2002) indicated that less than half of the empirical studies support the goal proximity hypothesis in GST. These results also challenge the initial theorizing by Locke and Latham (Citation2002) that combining proximal and distal goals would result in greater performance in comparison to implementing either goal alone. How the short-term and long-term timeframe should be defined is also still relatively controversial and can vary across different contexts (Locke & Latham, Citation2013).

Kyllo and Landers (Citation1995) also examined the potential influence of goal source on task performance. Interestingly, they found that self-set and participatively-set goals resulted in significantly higher performance compared to assigned goals. This too runs counter to Locke and Latham’s (Citation1990, Citation2002) theorizing – primarily based on research from organizational psychology – that there should be no significant differences in performance between self-set, participatively set, and assigned goals (Locke & Latham, Citation2002). It was suggested that an individual’s ‘ownership’ of a goal (which were thought to be less likely to occur with assigned goals) could be a critical motivation to commit to the goal (Hall & Kerr, Citation2001). However, a comprehensive review of the research on the various goal sources and their influence on the success of goal setting interventions in sport has not yet been conducted.

Finally, with regard to goal types, research in sport differ from the labeling goal types noted in GST. Specifically, whereas learning goals and performance goals have been used to characterize goal types in other domains, the sport domain has used three different goal types: process, performance, and outcome goals (Locke & Latham, Citation2013). Process goals refer to focusing on learning specific skills or techniques (e.g. a swimmer setting a goal to swim a length in a given number of strokes); performance goals refer to improving one’s performance standards (e.g. a swimmer aiming for a personal best in their race); and outcome goals refer to strictly focusing on the outcome of a match or a competition (e.g. a swimmer setting a goal to win their event; Burton & Weiss, Citation2008; Filby et al., Citation1999). These three goal types are mainly distinguished by their controllability (Burton, Citation1989; Burton & Naylor, Citation2002). This conceptualization has been particularly relevant to sport domain, as the learning ‘process’ and individual ‘performance’ standards are dependent on one’s goal commitment, but certain ‘outcome’ (e.g. winning a tournament) could be dependent on the opponents and external factors regardless of one’s goal commitment. Indeed, empirical findings substantiated that each goal type has distinct effects on goal setting outcomes in sports (Burton, Citation1989; Filby et al., Citation1999; Kingston & Hardy, Citation1997). However, there have been relatively few empirical studies in sports which directly compared the differences between process, performance, and outcome goals (Kingston & Wilson, Citation2009).

In summary, although previous reviews (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008; Healy et al., Citation2018; Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995) shed some light on the effects of goal setting on performance within sports, several limitations should be pointed out. First, most of the earlier reviews of goal setting in sport and exercise combined laboratory-based research from sport (e.g. basketball shooting), exercise (e.g. sit-ups), and motor performance (e.g. juggling) together (e.g. Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995). This could be problematic as there are situational and motivational differences between the sporting environments in which athletes engage compared to other contexts (Weinberg & Weigand, Citation1993). For example, the utility and effectiveness of goal setting with an elite athlete seeking to maximize performance in sport may differ from an inactive individual who is in the early stages of new exercise behavior. Another problem with combining sport, exercise, and motor performance in a single review is that it could provide a biased view of the effectiveness and dynamics of goal setting. Indeed, there have been relatively fewer goal setting studies in sport compared to exercise and motor tasks (Williams, Citation2013). Hence, it was inevitable for previous meta-analyses and reviews (Burton & Naylor, Citation2002; Burton & Weiss, Citation2008; Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995) to be more heavily weighted towards exercise and motor tasks. Moreover, the extent to which the effectiveness of goal setting interventions in sport are influenced of theorized goal characteristics (difficulty, specificity, proximity, source, and type) and moderators (goal commitment, feedback, task complexity, and task knowledge and resources) is still not yet clear. Thus, it is both timely and pertinent to conduct a systematic review of the applied goal setting literature that is delimited to sport contexts only. As part of this, it would seem particularly important to review the inclusion of/consideration for GST’s goal characteristics and moderators in these interventions. Such a review would enhance our understanding of the dynamics of goal setting in applied sport settings specifically, and could also enable the provision of clearer practical recommendations for coaches, athletes, and applied practitioners on setting effective goals.

The present review

The overall purpose of the present study is to systematically review the goal setting research within applied sport contexts (i.e. non-laboratory). The aspects of goal setting interventions in the current review were based on the components of GST (Locke & Latham, Citation1990, Citation2002, Citation2013). Specifically, we considered the five goal characteristics (goal difficulty, goal specificity, goal proximity, goal types, and goal sources) as well as the five moderators (ability, goal commitment, feedback, task complexity, and task knowledge and resources) embedded in this theory. In summary, the aims of the present review were to (a) provide an overview of studies that implemented goal setting interventions to athletes in sport-specific context, and (b) investigate how the tenets of GST were applied and examined.

Materials and methods

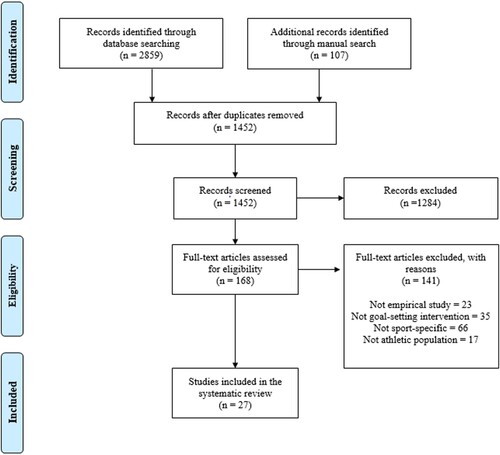

The present review was organized based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (see Moher et al., Citation2009). The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in to show the flow of our systematic literature searching process from search strategy to study selection. The PRISMA checklist is also provided in Appendix A.

Figure 1. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) flow diagram for literature search process.

Search strategy

An online literature search was conducted in five psychology and sport science databases (including all dates until May 2019 when the searches were conducted): PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus. The aim of the search was to find goal setting interventions with athletes in an applied/real-world (i.e. non-laboratory) sport-specific context, and the search terms were made based on this objective. The resulting search terms and filters were as follows: (1) ‘goal’ AND (2) ‘intervention’ OR ‘set’ OR ‘effect’ OR ‘practic’ OR ‘appl’ OR ‘mak’ OR ‘strategy’ OR ‘impact’ OR ‘using’ AND (3) ‘sport’ OR ‘athlete’ OR ‘performance’ OR ‘player’ OR ‘skill’ OR ‘training’ OR ‘compet’ OR ‘elite’ (AND) NOT (4) ‘business’ OR ‘hospital’ OR ‘academic’ OR ‘government’ OR ‘consumer’ OR ‘management’ OR ‘worker’ OR ‘nurse’ OR ‘obesity’ OR ‘occupational’ OR ‘military’. Further details on the search terms used are provided in Appendix B. Limiters used in the online database search were peer-reviewed academic journals written in English. We also conducted manual searches of the reference lists of relevant narrative reviews of goal setting in sport and exercise (Burton & Naylor, Citation2002; Burton & Weiss, Citation2008; Hall & Kerr, Citation2001; Healy et al., Citation2018; Kingston & Wilson, Citation2009; Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995; Williams, Citation2013).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion based on the following criteria: (a) peer-reviewed academic study; (b) available in English language; (c) empirical study; (d) goal setting intervention; (e) sport-specific context; and (f) samples were from an athletic population. The eligibility criteria (a) and (b) were applied as limiters during the online database searching stage. In relation to the eligibility criteria (e), goal setting intervention studies using exercise or motor task were excluded. Regarding the eligibility criteria (f), the present review was delimited to applied sport contexts. As such, only studies with amateur or elite athletes were included; studies with beginners or inexperienced participants in the specific sport (e.g. those involving participants for a laboratory-based experiment) were excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

The studies were selected using the following process. Initially, the first author screened the titles and abstracts of the identified studies after removing the duplicates. The first author then examined the full-text of the remaining studies for eligibility. Any borderline cases were discussed between the authors to determine their final inclusion. Finally, the characteristics (author names, publication date, sample characteristics, intervention design, intervention length, details of the intervention, main findings) of the included studies were extracted.

Results

The search strategy identified 2859 studies (223 from SPORTDiscus, 576 from Web of Science, 391 from PubMed, 978 from Scopus, and 691 from PsycINFO) from the database search and 107 studies through manual citation searches. After the duplicates were removed, and the studies were screened by title and abstract, 168 full-texts were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 141 studies were excluded, which resulted in 27 studies being included in the present systematic review.

Study characteristics

presents a detailed summary of each study. The 27 included studies were from various sports, such as basketball (n = 9), volleyball (n = 3), athletics (n = 2), gymnastics (n = 2), swimming (n = 2), and a collection of single studies from a range of other sports, including American football, boxing, golf, speed skating, field hockey, lacrosse, multi-event, rugby, soccer, and tennis. A range of intervention designs were used, including single-subject (n = 10; 37%), within-subject (n = 2; 7%), and between-subject (n = 15; 56%) designs. The mean sample size was n = 5.7 for single-subject, n = 44.6 for between-subject, and n = 10.5 for within-subject studies. The intervention length ranged from a single session to two consecutive seasons. A season-long intervention was the most frequently used time frame (9 out of 27 studies; 33%). Most goal setting interventions (24 out of 27 studies; 89%) had the aim of improving sport-specific performance. Within five studies, some psychosocial variables were examined along with the sport-specific performance goals – these included anxiety (Burton, Citation1989; Kingston & Hardy, Citation1997; O’Brien et al., Citation2009), confidence (Burton, Citation1989; Kingston & Hardy, Citation1997; O’Brien et al., Citation2009; Vidic & Burton, Citation2010), motivation (Vidic & Burton, Citation2010), and team cohesion (Palao et al., Citation2016). Three studies did not focus on performance at all, but on enhancing team cohesion (Senécal et al., Citation2008), increasing positive affect (McCarthy et al., Citation2010), and reducing fear of failure (Wikman et al., Citation2014).

Table 1. Summary of the included studies.

Goal characteristics and moderators

Difficulty

Goal difficulty was considered in eight out of 27 studies (30%). Four single-subject studies (Lerner et al., Citation1996; McCarthy et al., Citation2010; Vidic & Burton, Citation2010; Ward & Carnes, Citation2002) incorporated goal difficulty in their interventions, and they were effective in improving the desired outcome. Three between-subject studies (Lane & Streeter, Citation2003; Tenenbaum et al., Citation1999; Weinberg et al., Citation1994) examined the goal setting effectiveness between groups by manipulating goal difficulty. No significant differences were found between different goal difficulties, although the goal setting intervention improved each group’s targeted performance. The other within-subject study (Anderson et al., Citation1988) indicated that difficult but achievable goals resulted in a higher win rate for collegiate hockey players, but there was no significant impact on the target outcome.

Specificity

Goal specificity was considered in 10 out of 27 studies (37%). Among four single-subject studies that included specific goals in their procedure, three interventions were effective in improving the targeted outcome (Mellalieu et al., Citation2006; Vidic & Burton, Citation2010; Ward & Carnes, Citation2002), while the other intervention (Zetou et al., Citation2008) was not. Among six between-subject studies, three studies (Kingston & Hardy, Citation1997; Lerner et al., Citation1996; Neumann & Hohnke, Citation2018) showed that setting specific goals was superior to control groups. Two other studies (Corrêa et al., Citation2006; Weinberg et al., Citation1994) showed that setting specific goals did not result in significant improvement than do-your-best goals. The other study (Pierce & Burton, Citation1998) indicated that goal characteristics (e.g. specificity) could be moderated by individual goal orientation. There were four studies (Lerner et al., Citation1996; Vidic & Burton, Citation2010; Ward & Carnes, Citation2002; Weinberg et al., Citation1994) that concurrently employed goal difficulty and goal specificity in their interventions. Goal setting appeared to result in performance improvements in three of these studies (Lerner et al., Citation1996; Vidic & Burton, Citation2010; Ward & Carnes, Citation2002); significant differences between a goal setting and control condition were not found in the study by Weinberg et al. (Citation1994).

Proximity

Eight out of 27 studies (30%) incorporated the aspect of goal proximity in their goal setting interventions. The definitions of short- and long-term goals varied across studies. Short-term goals ranged from daily to weekly goals. Long-term goals ranged from the last trial of a single session to a season-long goal. A single-subject study (Vidic & Burton, Citation2010) which set a combination of short- and long-term goals resulted in effective goal improvement. The other seven within-subject studies showed mixed results regarding goal proximity. Four studies (Kingston & Hardy, Citation1997; Senécal et al., Citation2008; Tenenbaum et al., Citation1999; Wanlin et al., Citation1997) showed that the combination of short- and long-term goals resulted in more significant improvements of the targeted outcome than the control group. In contrast, Weinberg et al. (Citation1994) reported that there were no significant differences between goal setting group that used a combination of short- and long-term goals, and the do-your-best control group without temporal consideration. The other two studies indicated that neither short- nor long-term goals were superior to one another (Getz & Rainey, Citation2001), or do-your-best goal group (Corrêa et al., Citation2006).

Sources

Only one study examined differences in goal effectiveness based on goal source (i.e. whether the goals were self-set, participatively set, or assigned). Lambert et al. (Citation1999) examined the difference between self-set and assigned goal conditions on performance and found that participants with an external locus of control spent more time on-task and performed better in the assigned goal condition, whereas participants with an internal locus of control spent more time on-task and performed better in the self-set goal condition. Beyond this studying comparing goal sources, 20 out of 27 studies (74%) in their goal setting interventions stated how goals were set. Seven of them used assigned goals, 10 of them used self-set goals, and three of them used participatively-set goals. Regardless of goal sources, improvements in the targeted outcome were shown in all 20 interventions.

Type of goal

Regarding goal types, there were two studies (Burton, Citation1989; Kingston & Hardy, Citation1997) that examined the effects of different goal types on goal setting success. Burton (Citation1989) found that setting a performance goal in combination with an outcome goal resulted in superior performance than setting an outcome goal alone. Kingston and Hardy (Citation1997) found that participants in the performance goal condition, or the process goal condition demonstrated significantly higher performance than those within the control group. However, there was no significant difference between the process and performance goal groups.

Moderators

Regarding the moderators suggested in GST (Locke & Latham, Citation1990, Citation2002) – ability, goal commitment, feedback, task complexity, and task knowledge and resources – it was surprising that these variables were rarely considered in the interventions. Indeed, there were no comparisons of, or explicit considerations for, these moderators other than ability and feedback. Regarding ability, only one study (O’Brien et al., Citation2009) compared the effects of goal setting between elite and non-elite athletes – they found improvements in targeted behaviors, anxiety, and self-confidence elite boxers but not non-elite boxers. Four studies described participants as elite, including basketball players (Neumann & Hohnke, Citation2018; Swain & Jones, Citation1995), volleyball players (Palao et al., Citation2016), and runners and swimmers (Wikman et al., Citation2014). Positive outcomes were demonstrated in all four studies, which included: increases in basketball shooting performance (Neumann & Hohnke, Citation2018) and basketball skills (Swain & Jones, Citation1995); improved volleyball skills and engagement with one’s team (Palao et al., Citation2016); and decreased fear of failure (Wikman et al., Citation2014). The ability levels of the participants in the remaining studies were not explicitly stated.

Feedback on goal progress was incorporated into six interventions. Five of them (Brobst & Ward, Citation2002; O’Brien et al., Citation2009; Senécal et al., Citation2008; Shoenfelt, Citation1996; Vidic & Burton, Citation2010) reported that incorporating feedback into goal setting was effective in achieving desired outcome. The other study (Giannini et al., Citation1988) did not find significant differences in outcome between the do-your-best goal with feedback condition and do-your-best goal without feedback condition.

Discussion

The present review aimed to review the extant research on goal setting interventions in sports and to examine how GST has been applied to athletes in applied sport settings. Salient features of the goal setting interventions in sports were small sample size, single-subject designs, and a strong focus on performance outcomes. Regarding the tenets of GST, there was limited evidence that these were considered in the interventions conducted within these studies.

Features of goal setting interventions in sports

Previous reviews (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995) had already identified small sample size as a limitation of the goal setting literature in sport and exercise research. The present review found that the problem with sample size is still largely unresolved in the sport context. Indeed, 63% of the included studies had fewer than 30 participants, which is suggested as the minimum number sample size in empirical studies (Israel, Citation2009). Moreover, the average number of participants for the 10 single-subject studies was 6, while the average sample size was 45 for the 15 between-subject studies. Relatedly, more than one-third of the studies in our review adopted a single-subject research design. Although this design certainly has its strengths, it may be problematic in goal setting research since any form of goal setting could be effective in improving performance (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995; Locke & Latham, Citation2002). Indeed, the percentage of single-subject studies that reported goal setting effectiveness (70%) was higher than the between-subject designs (46%). Without comparison groups, it is difficult to determine the true effect of a goal setting intervention (i.e. versus those who received a separate type of goal setting intervention, an intervention focused on a different mental skill, or a no-intervention control group). Additionally, without comparison groups, single-subject design may have low internal and external validity (Locke et al., Citation1981).

Due to small sample sizes and reliance on single-subject designs, goal setting studies could have a greater risk of Type II error due to inadequate statistical power (Cohen, Citation1992). It would be easy for us to simply reiterate that future research should aim to obtain larger sample sizes and a greater use of controlled intervention designs. However, that somewhat simplistic recommendation does not acknowledge the considerable challenges of recruiting a large number of participants for intervention research within athletic populations due to difficulties such as sustained access to participants, agreement from coaches, time dedicated to the goal setting practice, and possible dropout due to injury or deselection. Moreover, the use of a control group within applied interventions presents researchers and practitioners with an ethical dilemma – withholding an intervention from one group of athletes may put them at a competitive disadvantage to their competitors or teammates who receive the intervention. As such, creative solutions on a case-by-case basis are likely needed to balance the need for high-quality scientific research in this area with the potentially substantive implications of assigning a large number of participants to a control condition. For example, if a researcher is only able to implement a single-subject or case study approach, they should at the very least be sure to follow recent recommendations for best practice in these types of research designs within sport (e.g. triangulating data; see Cotterill & Schinke, Citation2017).

The last feature of the included interventions was a strong – and sometimes exclusive – focus on athletic performance as the targeted outcome. Notwithstanding the contributions that these studies have made in determining whether goal setting impacts performance, researchers could also consider incorporating additional psychological and physiological variables, and investigating the interrelationships between goal setting, performance, and those other variables. In particular, this could improve our understanding of the mechanisms that explain how goals impact sport performance and other salient processes and outcomes (e.g. group behaviors, athlete motivation). Moreover, incorporating invariance testing that examine/compare the effects of goal setting interventions across different populations (e.g. gender, age, skill level) would improve the generalizability of those interventions.

Tenets of goal setting theory in sport research

Overall, the goal characteristics (e.g. goal difficulty, goal specificity) proposed by Locke and Latham (Citation1990, Citation2002) were considered to some extent within the included studies, albeit rather inconsistently across studies. In contrast, the proposed moderators (e.g. commitment, task complexity) from GST were rarely taken into account when implementing a goal setting intervention. In addition, it was difficult to determine a true effect of a particular goal characteristic in many studies for two particular reasons. First, these characteristics were either rarely incorporated/considered in the goal setting intervention itself or were not reported explicitly by the paper’s author(s). Second, the single-subject study design without a comparison group (37% of the included studies) presents challenges in ascertaining the differential impact of those characteristics. Specifically, since nearly any form of goal setting can show some degree of performance improvement (Locke & Latham, Citation2002, Citation2013), single-subject designs do not allow one to determine whether the goal setting intervention that incorporated one of these characteristics (e.g. creating difficult goals) would be superior or inferior (or no different) to another intervention with different levels/qualities of those characteristics (e.g. easy goals) that could have been delivered to those participants. Nonetheless, we were able to derive some notable findings in our review pertaining to these characteristics and moderators, and we now turn our attention to unpacking those findings.

Goal difficulty did not appear to make a substantive difference in the effects of a goal setting intervention. This is inconsistent with the linear relationship suggested in GST as well as the previous meta-analysis of laboratory-based sport, exercise, and motor control performance (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995), which found moderately difficult goals to be more effective than easy or very difficult goals. It should be reiterated that our review was strictly focused on studies within applied sport contexts, whereas the studies included in Kyllo and Landers (Citation1995) meta-analysis were predominantly based on exercise and motor performance. Hence, a potential explanation for these differences in findings could be that the operationalization of goal difficulty is often inconsistent in sports research compared to other contexts (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008). The other possibility could be that athletes redefine their goals if they perceive them to be too easy or difficult (Hall & Kerr, Citation2001), or even create their own goals (which could be of any level of difficulty) when they have no goals. Differences in motivation levels (cf. Weinberg & Weigand, Citation1993, Citation1996) between athletes in applied settings compared to participants in laboratory-based experiments (e.g. volunteering university students) may also help explain these apparent differences.

The findings around goal specificity showed limited support for the notion from GST that specific goals are better than vague or do-your-best goals. One possible problem of goal specificity in sport contexts could be that the contextual specificity in each sport can make the vague or do-your best goals to be relatively specific (Hall & Kerr, Citation2001). For example, in tennis, improving kick serve accuracy might seem like a vague goal. Still, the task (i.e. kick serve) itself already embeds some specificity as kick serves are one specific type of serve and they usually have a specified area to target. It should also be noted that Locke and Latham (Citation2019) recently suggested that goal specificity alone is insufficient and that it should be combined collaboratively with goal difficulty for effective goal setting. For example, unrealistically easy – but specific – goals would not extract enough goal commitment. The effect (and potential mechanisms) of this combination within sport is not yet clear but does appear to have some initial promise, since three of the four studies that combined specificity and difficulty demonstrated improvements in the targeted outcomes. As such, it would seem useful for researchers in future to continue examining the impact of this combination.

Regarding goal proximity, there was mixed support overall for GST's theorizing that using the combination of short-term and long-term goals is more effective than control groups, or using either goal alone (Locke & Latham, Citation2002). Indeed, a range of goal timelines were shown to be effective in the reviewed studies. Part of the difficulty in examining timeframes is that the exact definition of a ‘short-term’ versus ‘long-term’ goal is still controversial, and it could be heavily influenced by specific contexts (Locke & Latham, Citation2013). A possible workaround to this controversy and next step in better understanding the nuances associated with proximity may be to specify beyond these binary categorizations. Instead, researchers could perhaps classify goals (a) as daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly goals, or (b) by the season of one’s sport (e.g. first game, quarterly, midpoint, end-of-season goals). This could allow us to better understand whether goals of certain timelines indeed have a differential impact on the effectiveness of an intervention or whether previous suggestions that any timeframe would be useful in sport since sports populations show higher motivation compared to other domains (Burton & Naylor, Citation2002).

It was also difficult to definitively conclude the effect of goal sources as there were few studies that employed different goal source conditions. Although it was previously shown that self-set and participatively set goals are better than assigned goals (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995), it should be reiterated that most studies in that meta-analysis were from non-athlete participants. Due to the high demand of sports, it is possible that athletes demonstrate a higher goal achievement whether the goal is assigned, self-set, or participatively-set as athletes are generally more committed towards their sporting goals compared to volunteers in laboratory-based experiments (Burton & Naylor, Citation2002). Taking these concerns into account, future research could investigate the moderators of goal sources in the athletic population, such as individuals’ personal preferences of goal source (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008) – perhaps some athletes only respond well to self-set goals whereas others prefer to be assigned their goals.

The relative lack of studies comparing different goal types in sport (i.e. process, performance, and outcome goals) was surprising since these seem to be commonly discussed in this context (e.g. coaches encouraging athletes to ‘focus on the process’). A potential reason for this paucity was argued by Filby et al. (Citation1999) that examining the differences between goal types might be trivial in applied sport settings, since successful athletes often incorporate a combination of process, performance, and outcome goals. Although the importance and utility of different types of goals was emphasized in GST (Locke & Latham, Citation2002, Citation2013), we are precluded from offering any concrete conclusions of the type of goals – or combination of goal types – that would be most beneficial within sport settings based on the existing body of research. That said, as with goal source, the impact of this characteristic might also be based on the individual preferences of athletes. Research in future could also give greater consideration for other individual variables (e.g. age, developmental/skill level, personality) that might moderate the effects of each goal type on salient outcomes.

It was also difficult to examine the relevance and importance of the moderators in goal setting due to the limited consideration for these moderators. It is possible that this paucity of available research is due to the challenges of operationalizing and/or measuring these moderators in the applied sport settings (e.g. how exactly to categorize ability levels or task complexity). At present, there also appear to be few psychometrically-sound instruments that could accurately measure GST’s moderators in sport contexts. For instance, it can be difficult to artificially manipulate feedback in sports since performance statistics (e.g. score) or physiological feedback (e.g. fatigue) are already present and somewhat ingrained in sport – hence, athletes can consistently refer to these sources of feedback to assess their progress towards goals (Kingston & Wilson, Citation2009). Thus, the development of psychometric instruments related to these moderators would provide new insights into the process of goal setting interventions. For example, psychometric instruments that capture the degree to which athletes buy-in to goal setting intervention can help measure goal commitment during a goal setting intervention.

Applied implications

Given the focus on applied interventions, our review has implications for coaches, practitioners, and athletes. It was shown that goal setting was indeed a useful mental skill in many cases and even simple forms of goal setting appeared to be effective in achieving desired outcomes (which primarily focused on sport performance). Nevertheless, prescribing goal setting should be a careful process, as arbitrary goal setting could potentially cause harmful side effects such as decreased self-efficacy and lower intrinsic motivation (Ordóñez et al., Citation2009). Unlike lab-based experiments, prescribing goal setting in applied sport settings is a complex and potentially unpredictable process since many variables are difficult to control in this context. In other words, applying theoretical tenets that were based on other contexts (e.g. industrial/organizational psychology) might not be as straightforward and generalizable to sport (Healy et al., Citation2018; Weinberg, Citation2010).

In light of the inconsistencies in the reviewed studies with regard to the importance of the five goal characteristics and five moderators within GST, perhaps the most suitable recommendation from our review is to develop goal setting programs that place a strong emphasis on the characteristics, needs, preferences, and goal setting styles of individual athletes (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008). Although it might be appealing to directly apply the GST framework or certain acronyms (e.g. setting so-called ‘SMART’ goals), the existing evidence appears to suggest that these ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches are likely not appropriate/effective for every athlete. This is certainly not to say that the goal characteristics and moderators should no longer be considered in goal setting interventions. In fact, reflecting on those tenets of GST could actually help practitioners and coaches develop effective, personalized goals with their athletes. For example, specific, challenging performance goals might be appropriate for advanced athletes who have a high level of ability (cf. Locke & Latham, Citation2019) whereas less specific, learning goals would likely be more appropriate for athletes who are in the early stages of development in their sport (Locke & Latham, Citation2002, Citation2013). As another example, some athletes might prefer to specify goals for each of their training sessions to help them stay motivated and focused on a consistent basis; others might find this to be daunting or overwhelming and prefer goals of a longer term (e.g. weekly, monthly, season-long).

In any case, one recommendation that does seem to apply to most (if not all) goal setting interventions is the provision of appropriate feedback regarding goal progress. Purposefully monitoring the impact of goals on performance and other variables (e.g. motivation, commitment) can provide athletes with effective feedback on their progress and can help guide effort and mobilize resources to the desired goal. That said, this feedback should also be tailored to the individual athletes. For example, whereas some athletes might respond well to receiving feedback on a consistent and frequent basis, such frequency might be distracting and cause anxiety (cf. Latham & Locke, Citation2007). In summary, a greater consideration within both research and applied sport contexts for individualized goal setting approaches and context-specific considerations is clearly warranted. As evidence for the most useful process for developing these individualized interventions – as well as the evidence supporting (or disproving) the efficacy and effectiveness of those interventions – accumulates, both researchers and applied practitioners will be better equipped to help athletes set effectual goals.

Limitations

Although this study provides the first systematic review of goal setting specifically within applied sport contexts, some limitations should be acknowledged. The first limitation is that the review only included published studies in peer-reviewed academic journals. Although peer-review is a crucial process in ensuring high-quality scientific research, systematic reviews can be prone to publication bias if unpublished studies are not included (Bakker et al., Citation2012). In our review specifically, it is possible that goal setting interventions which had non-significant results might not have been published. Nevertheless, including unpublished studies might be equally problematic in terms of methodical flaws or research quality, compared to peer-reviewed publications in scientific journals (Barker et al., Citation2020). As this review did not include meta-analysis (due to limitations in the available statistics within the included studies), we were unable to measure publication bias statistically. As further research on goal setting (with sufficient statistics included to calculate effect sizes) is obtained, future reviews may be able to conduct meta-analysis and better assess publication bias.

Another (de)limitation of the present review was that it examined the goal setting interventions only through the perspective of GST. Therefore, some important aspects of psychological interventions could have been overlooked. For example, some systematic reviews on psychological interventions have found that an intervention’s length can play an important role in predicting statistical significance (Anderson & Ozakinci, Citation2018). Future studies can reflect on this perspective when designing a goal setting intervention and carefully determine the adequate intervention length depending on their specific context. Moreover, it has been suggested that goals in sport contexts should be investigated within a more comprehensive framework, including goal orientation, goal progress, and goal attainment (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008). In addition, although GST seems to be a viable theoretical framework to refer to when implementing a goal setting, it involves little consideration for the motives underpinning goal pursuit (Locke & Latham, Citation2013). As such, future studies that involve a wider range of theories of goal setting will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the goal setting research. For instance, the Competitive Goal Setting Model (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008) suggested that individual differences in goal orientation and goal setting styles could lead to differences in motivations and goal commitment, which may assist practitioners in determining the preferred goal difficulty for their individual players. Other frameworks such as the Self-Concordance Model (Sheldon & Elliot, Citation1999) could also be used to examine the motivations underpinning goal pursuit, their impact on goal striving and attainment, as well as psychological well-being after goal attainment (or failure or disengagement). Indeed, this model has shown to be relevant to a sporting context in predicting performance (Ntoumanis et al., Citation2014), well-being (Smith, Citation2016), and understanding how coaches can support adaptive goal striving (Healy et al., Citation2014). Moreover, goal setting has been incorporated in various intervention package studies (e.g. Thelwell & Greenlees, Citation2001). Researchers in future studies could examine the effect of, and interaction between, goal setting and other components of an intervention package – this would provide practical insight for applied researchers on the optimal ways of combining goal setting with other strategies.

Concerning the inconclusive evidence and limited support for many aspects of GST in applied sport contexts, our review raises an important question for future research: are those employing goal setting in applied sport contexts not applying the tenets of GST due to a lack of awareness of these principles (i.e. education is needed to enhance understanding), or because some tenets of GST (e.g. characteristics, moderators) might be irrelevant within these settings? Research investigating this question within applied contexts and including key stakeholders is both timely and important within applied sports science as a whole. As such, future research could consider empirical approaches that are based on coaches’ experiential knowledge (Greenwood et al., Citation2012) or that are co-produced by practitioners, coaches, and athletes (Fullagar et al., Citation2019), as opposed to the traditional one-way approach from researchers to applied practice. This could include, for example, qualitative approaches that seek to identify practitioners’, coaches’, and athletes’ perspectives on the goal setting practices that work most effectively in various contexts or levels of athlete development.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first systematic review of goal setting interventions strictly focused on athletes and sport in applied settings. Most previous reviews combined the findings of sport and exercise in a single review, limiting their practical relevance for applied practitioners and researchers. As such, we hope that our review offers relevant insight for those investigating and applying goal setting interventions within applied sport contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Note: *Studies included in the systematic review are noted with an asterisk

- Anderson, N., & Ozakinci, G. (2018). Effectiveness of psychological interventions to improve quality of life in people with long-term conditions: Rapid systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0225-4

- *Anderson, D. C., Crowell, C. R., Doman, M., & Howard, G. S. (1988). Performance posting, goal setting, and activity-contingent praise as applied to a university hockey team. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.73.1.87

- Bakker, M., van Dijk, A., & Wicherts, J. M. (2012). The rules of the game called psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459060

- Barker, J. B., Slater, M. J., Pugh, G., Mellalieu, S. D., McCarthy, P. J., Jones, M. V., & Moran, A. (2020). The effectiveness of psychological skills training and behavioral interventions in sport using single-case designs: A meta regression analysis of the peer-reviewed studies. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 51, 101746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101746

- *Brobst, B., & Ward, P. (2002). Effects of public posting, goal setting, and oral feedback on the skills of female soccer players. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2002.35-247

- Burton, D. (1994). Goal setting in sport. In R. N. Singer, M. Murphey, & L. K. Tennant (Eds.), Handbook of research on sport psychology (pp. 467–491). Macmillan.

- *Burton, D. (1989). Winning isn’t everything: Examining the impact of performance goals on collegiate swimmers’ cognitions and performance. The Sport Psychologist, 3(2), 105–132. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.3.2.105

- Burton, D., & Naylor, S. (2002). The Jekyll/Hyde nature of goals: Revisiting and updating goal-setting in sport. In T. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 459–499). Human Kinetics.

- Burton, D., & Weiss, C. (2008). The fundamental goal concept: The path to process and performance success. In T. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 339–375, 470–474). Human Kinetics.

- Burton, D., Yukelson, D., Weinberg, R., & Weigand, D. (1998). The goal effectiveness paradox in sport: Examining the goal practices of collegiate athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 12(4), 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.12.4.404

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Corrêa, U. C., de Souza Júnior, O. P., & Santos, S. (2006). Goal setting in acquisition of a volleyball skill late in motor learning. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 103(1), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.103.1.273-278

- Cotterill, S. T., & Schinke, R. J. (2017). Conducting and publishing case study research in sport and exercise psychology. Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1123/cssep.2017-0012

- Filby, W. C. D., Maynard, I. W., & Graydon, J. K. (1999). The effect of multiple-goal strategies on performance outcomes in training and competition. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 11(2), 230–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209908404202

- Fullagar, H. H. K., McCall, A., Impellizzeri, F. M., Favero, T., & Coutts, A. J. (2019). The translation of sport science research to the field: A current opinion and overview on the perceptions of practitioners, researchers and coaches. Sports Medicine, 49(12), 1817–1824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01139-0

- *Getz, G. E., & Rainey, D. W. (2001). Flexible short-term goals and basketball shooting performance. Journal of Sport Behavior, 24(1), 31–41.

- *Giannini, J. M., Weinberg, R. S., & Jackson, A. J. (1988). The effects of mastery, competitive, and cooperative goals on the performance of simple and complex basketball skills. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(4), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.10.4.408

- Gillham, A., & Weiler, D. (2013). Goal setting with a college soccer team: What went right, and less-than-right. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2013.764560

- Greenwood, D., Davids, K., & Renshaw, I. (2012). How elite coaches’ experiential knowledge might enhance empirical research on sport performance. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 7(2), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.7.2.411

- Hall, H. K., & Byrne, A. T. (1988). Goal setting in sport: Clarifying recent anomalies. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(2), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.10.2.184

- Hall, H. K., & Kerr, A. W. (2001). Goal setting in sport and physical activity: Tracing empirical developments and establishing conceptual direction. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Advances in motivation in sport and exercise (pp. 183–233). Human Kinetics.

- Healy, L. C., Ntoumanis, N., van Zanten, J. J. C. S. V., & Paine, N. (2014). Goal striving and well-being in sport: The role of contextual and personal motivation. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 36(5), 446–459. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2013-0261

- Healy, L., Tincknell-Smith, A., & Ntoumanis, N. (2018). Goal setting in sport and performance. In L. Healy, A. Tincknell-Smith, & N. Ntoumanis (Eds.), Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.152

- Israel, G. D. (2009). Determining sample size. http://www.edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/pd/pd00600.pdf

- Kingston, K. M., & Wilson, K. M. (2009). The application of goal setting in sport. In S. Mellalieu & S. Hanton (Eds.)Advances in Applied Sport Psychology: A Review (pp. 75–123). Routledge.

- *Kingston, K. M., & Hardy, L. (1997). Effects of different types of goals on processes that support performance. The Sport Psychologist, 11(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.11.3.277

- Kyllo, L. B., & Landers, D. M. (1995). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(2), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.2.117

- *Lambert, S. M., Moore, D. W., & Dixon, R. S. (1999). Gymnasts in training: The differential effects of self-and coach-set goals as a function of locus of control. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 11(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209908402951

- *Lane, A., & Streeter, B. (2003). The effectiveness of goal setting as a strategy to improve basketball shooting performance. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 34, 138–150.

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2007). New developments in and directions for goal-setting research. European Psychologist, 12(4), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.12.4.290

- *Lerner, B. S., Ostrow, A. C., Yura, M. T., & Etzel, E. F. (1996). The effects of goal-setting and imagery training programs on the free-throw performance of female collegiate basketball players. The Sport Psychologist, 10(4), 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.10.4.382

- Locke, E. A. (1991). Problems with goal-setting research in sports—and their solution. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(3), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.13.3.311

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1985). The application of goal setting to sports. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.205

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Prentice Hall.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (Eds.). (2013). New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2019). The development of goal setting theory: A half century retrospective. Motivation Science, 5(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000127

- Locke, E., Shaw, K., Saari, L., & Latham, G. (1981). Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychological Bulletin, 90(1), 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.90.1.125

- Maitland, A., & Gervis, M. (2010). Goal-setting in youth football. Are coaches missing an opportunity? Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 15(4), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980903413461

- *McCarthy, P. J., Jones, M. V., Harwood, C. G., & Davenport, L. (2010). Using goal setting to enhance positive affect among junior multievent athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 4(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.4.1.53

- *Mellalieu, S. D., Hanton, S., & O’Brien, M. (2006). The effects of goal setting on rugby performance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39(2), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2006.36-05

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- *Neumann, D. L., & Hohnke, E. (2018). Practice using performance goals enhances basketball free throw accuracy when tested under competition in elite players. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 13(2), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2018.132.05

- Ntoumanis, N., Healy, L. C., Sedikides, C., Smith, A. L., & Duda, J. L. (2014). Self-regulatory responses to unattainable goals: The role of goal motives. Self and Identity, 13(5), 594–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.889033

- *O’Brien, M., Mellalieu, S., & Hanton, S. (2009). Goal-setting effects in elite and nonelite boxers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21(3), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200903030894

- Ordóñez, L. D., Schweitzer, M. E., Galinsky, A. D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2009). Goals gone wild: The systematic side effects of overprescribing goal setting. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2009.37007999

- *Ortega, E., Olmedilla, A., Palao, J. M., Sanz, M., & Bazaco, M. J. (2013). Goal-setting and players’ perception of their effectiveness in mini-basketball. Revista de Psicología Del Deporte, 22(1), 253–256.

- *Palao, J., Garcia de Alcaraz, A., Hernández Hernández, E., & Ortega, E. (2016). A case study of applying collective technical-tactical performance goals in elite men’s volleyball team. International Journal of Applied Sports Science, 28, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.24985/ijass.2016.28.2.68

- *Pierce, B. E., & Burton, D. (1998). Scoring the perfect 10: Investigating the impact of goal-setting styles on a goal-setting program for female gymnasts. The Sport Psychologist, 12(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.12.2.156

- *Senécal, J., Loughead, T. M., & Bloom, G. A. (2008). A season-long team-building intervention: Examining the effect of team goal setting on cohesion. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 30(2), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.2.186

- Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482

- *Shoenfelt, E. L. (1996). Goal setting and feedback as a posttraining strategy to increase the transfer of training. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 83(1), 176–178. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1996.83.1.176

- Smith, A. L. (2016). Coach behaviors and goal motives as predictors of attainment and well-being in sport. In M. Raab, P. Wylleman, R. Seiler, A. M. Elbe, & A. Hatzigeorgiadis (Eds.), Sport and exercise psychology research (pp. 415–432). Academic Press.

- *Swain, A., & Jones, G. (1995). Effects of goal-setting interventions on selected basketball skills: A single-subject design. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 66(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1995.10607655

- *Tenenbaum, G., Spence, R., & Christensen, S. (1999). The effect of goal difficulty and goal orientation on running performance in young female athletes. Australian Journal of Psychology, 51(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539908255328

- Thelwell, R. C., & Greenlees, I. A. (2001). The effects of a mental skills training package on gymnasium triathlon performance. The Sport Psychologist, 15(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.15.2.127

- *Vidic, Z., & Burton, D. (2010). The roadmap: Examining the impact of a systematic goal-setting program for collegiate women’s tennis players. The Sport Psychologist, 24(4), 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.24.4.427

- *Wanlin, C. M., Hrycaiko, D. W., Martin, G. L., & Mahon, M. (1997). The effects of a goal-setting package on the performance of speed skaters. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9(2), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708406483

- *Ward, P., & Carnes, M. (2002). Effects of posting self-set goals on collegiate football players’ skill execution during practice and games. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2002.35-1

- Weinberg, R. (1994). Goal setting and performance in sport and exercise settings: A synthesis and critique. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 26(4), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199404000-00012

- Weinberg, R. (2010). Making goals effective: A primer for coaches. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 1(2), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2010.513411

- Weinberg, R., & Weigand, D. (1993). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A reaction to Locke. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.15.1.88

- Weinberg, R., & Weigand, D. (1996). Let the discussions continue: A reaction to Locke’s comments on Weinberg and Weigand. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(1), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.18.1.89

- *Weinberg, R., Stitcher, T., & Richardson, P. (1994). Effects of a seasonal goal-setting program on lacrosse performance. The Sport Psychologist, 8(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.8.2.166

- *Wikman, J. M., Stelter, R., Melzer, M., Hauge, M.-L. T., & Elbe, A.-M. (2014). Effects of goal setting on fear of failure in young elite athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(3), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.881070

- Williams, K. J. (2013). Goal setting in sports. In E. A. Locke & G. P. Latham (Eds.)New developments in goal setting and task performance (pp. 375–396). Routledge.

- *Zetou, E., Papacharisis, V., & Mountaki, F. (2008). The effects of goal-setting interventions on three volleyball skills: A single-subject design. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 8(3), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2008.11868450