ABSTRACT

Despite clear evidence of the potential benefits gained by being physically active, children and adolescents (collectively youth) often fail to achieve the recommended daily 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). Focusing on youth physical activity in context provides the starting point for intervention design, but the design and implementation of effective interventions that leverage behavioral theory, evidence, and knowledge about settings remains a formidable challenge. This conceptual review aims to address critically relevant concepts, principles, and evidence from the literature to guide intervention design and implementation that target physical activity leader behavior toward reducing the problem of insufficient youth MVPA. The need to distinguish between the goals to increase MVPA within a setting and to increase youth overall/daily MVPA is emphasized. This review addresses the theoretical and practical considerations of interventions in settings where youth spend time each day. Included is an investigation of what gaps exist in current approaches to intervene through physical activity leaders in settings. Informed both by theory and extant evidence, potential solutions are discussed, including the synthesis of a novel theoretical framework to guide settings-based physical activity leader behavior interventions that address capabilities, opportunities, and motivations for physical activity behaviors across multiple setting levels.

© 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

Physical activity is beneficial for the health and development of children and adolescents (collectively called youth hereafter). To ensure health and developmental benefits, it is recommended that youth should participate in at least 60 min per day of a variety of enjoyable, developmentally appropriate moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (Piercy et al., Citation2018; Strong et al., Citation2005). Despite clear evidence of the potential benefits of being physically active, youth around the world often fail to achieve the recommended 60 min of MVPA (Aubert et al., Citation2018).

Reasons for the widespread insufficient levels of youth physical activity over the past few decades include decreases in active transport – including opportunities to walk or cycle to school – and decreases in availability of physical education (PE) classes (Gray et al., Citation2014; Knuth & Hallal, Citation2009). Concurrently, sedentary-promoting screen-based media have become central in everyday life (Houghton et al., Citation2015), while opportunities for active free play have declined for many youth (Singer et al., Citation2009). The settings where youth spend hours each day frequently offer little opportunity to engage in MVPA (Tassitano et al., Citation2020). In accordance with those trends, markers of cardiorespiratory fitness – which serves as a good indicator of health trajectory – also have been decreasing among youth (Knuth & Hallal, Citation2009; Tomkinson et al., Citation2019).

Given the ongoing problem of insufficient physical activity among youth, effective and wide-reaching interventions for physical activity behavior change are a critical need. Focusing on youth physical activity behavior in context provides the starting point for intervention design. As most settings where children spend significant amounts of time involve some level of adult supervision, this focus should be followed by a structured approach for determining specific intervention components. Such components may include evidence-based behavior change techniques that are delivered to physical activity leaders within youth settings. The term youth setting physical activity leader is used throughout this manuscript to refer to those adults who directly supervise youth; as a function of their supervisory role, these leaders may become de facto physical activity leaders. Youth setting physical activity leader may encompass terms that vary across settings, including staff, worker, facilitator, coach, supervisor, provider, troop leader, or teacher.

Insufficient youth physical activity poses a difficult challenge for the field, compounded by a lack of conceptual clarity within the literature, and many gaps in extant knowledge. To advance, efforts are needed to take inventory of relevant knowledge, to identify both gaps and insights, to highlight inconsistencies, and to propose potential pathways for future youth physical activity intervention studies. Therefore, this conceptual review aims to address critically relevant concepts, principles, and evidence from the literature to guide intervention design and implementation that target physical activity leader behavior toward reducing the problem of insufficient youth MVPA. Emphasis is placed on distinguishing between the goal to increase MVPA within a setting and the goal to increase youth overall/daily MVPA. This review also addresses the theoretical and practical considerations of interventions in settings where youth spend time together each day. The review investigates what gaps exist in current approaches to intervene through physical activity leaders in settings, and offers potential solutions that are informed by both theory and extant evidence in the form of a novel theoretical framework.

The theoretical basis of physical activity behavior change

In efforts to understand, predict, explain, and ultimately change physical activity behaviors among youth, numerous behavioral theories have been applied and evaluated; most of these theories have demonstrated utility within physical activity interventions (Messing et al., Citation2019). A sizable number of behavioral theories that are used in physical activity interventions have been imported from the fields of psychology, health education, or public health. Frequent theoretical imports include social cognitive theory, the transtheoretical model, theory of planned behavior, and self-determination theory (Glanz et al., Citation2015).

Behavioral theories are often applied within health-promotion interventions to address individuals’ intrapersonal and interpersonal determinants of behaviors such as physical activity. The general logic within theory-based physical activity interventions is that specific components of the intervention program, practices, or policy are designed to change one or more of the theoretical constructs (e.g. self-efficacy, attitudes) related to motivation or capability of the participants, which then should subsequently mediate a resulting change in physical activity behavior (Baranowski et al., Citation1998). Systematic reviews often show that statistically significant changes are more likely among physical activity interventions that are underpinned by theory, compared to atheoretical interventions, but that is not always the case (Messing et al., Citation2019). One gap in the literature on theory-based physical activity interventions concerns theoretical fidelity (Sebire et al., Citation2016). More research is needed on the degree to which interventionists apply behavioral theory in a manner that is consistent with the original theoretical tenets or principles, and whether effectiveness varies as a function of that consistency.

The theory of expanded, extended, and enhanced opportunities (TEO) has offered a novel conceptualization of youth physical activity behavior (Beets et al., Citation2016). TEO spans many diverse physical activity intervention ideas, aiming toward a common taxonomy by which intervention researchers can target various youth settings and contexts. TEO redirects some of the attention away from the intrapersonal and interpersonal determinants of physical activity that pertain to motivation and capability. Instead, TEO strongly focuses on what is available to youth within the environments where they live, learn, and play. Indeed, youth typically have limited choice – although such choices tend to increase during adolescence – regarding which settings they attend, and also what they are meant to do within those settings. Therefore, youth have limited autonomy over their physical activity behaviors within many settings (these concepts are discussed further in the setting theory section below). According to TEO, physical activity levels can be increased through: (1) The expansion of opportunities to be active by providing a new occasion to be active; (2) The extension of an existing physical activity opportunity by increasing the duration of that opportunity; or (3) The enhancement of the quality of currently available physical activity opportunities through finding ways to increase the percentage of time spent in MVPA. In contrast to numerous behavioral theories, models, and frameworks that focus mainly on the motivation and capability of youth (e.g. Welk, Citation1999), TEO is a welcome reminder to focus our attention on the availability of physical activity opportunities. Yet we must also ensure that youth are willing and able to take advantage of the opportunities that they do have to be active, and that they are well-supported by the adults who are supervising the activity settings.

Setting theory for physical activity interventions

Setting theorists have focused on the power of place and situational characteristics as key drivers of behavior among those present within the setting (Barker, Citation1968; Schoggen, Citation1989). Setting theories help to explain why certain behaviors are more likely to occur within a particular setting – independent of the individual characteristics of the people within the setting – while other behaviors are less likely to occur in that setting. For example, a typical school classroom combines the physical features of arranged chairs and desks with social norms, teaching practices, and policies that collectively produce seated academic activity among the students, rather than an active curriculum where students perform whole-body movements while learning. The application of setting theory is useful for reorienting health promotion efforts away from emphasizing individual-level influences on behavior toward greater emphasis on environmental and contextual influences (Whitelaw et al., Citation2001).

One important concept from behavior setting theory is synomorphy, or mutual support, between behavior and modifiable characteristics of the environmental context that are conducive to that behavior (Schoggen, Citation1989). Behavior settings should be structured to support the types of behaviors that are supposed to happen there. Interventionists should therefore not have high expectations for health behaviors to occur if the required social and physical environmental supports have not been structured. As applied to youth physical activity, setting theory predicts greater variability in an individual's behavior across various youth settings within the community than for various individuals within a single setting. Similarly, intervention on the physical and/or social structure of the setting is needed to provide an environmental context that is conducive to physical activity.

A crucially important consideration, in addition to the behavior setting, is the delivery setting for interventions or health promotion activities (Whitelaw et al., Citation2001). A delivery setting describes the location of an intended target audience for health behavior change who may be reached with intervention components. Delivery settings constitute the physical structure, social structure (which would include youth setting physical activity leaders), and context for planning, implementing, and evaluating interventions (Whitelaw et al., Citation2001). When the delivery setting and the intended behavior setting (where the behavior is supposed to occur) are distinctly separate, this can lead to gaps or problems that limit or thwart potential effectiveness of interventions (Rosenkranz, Citation2020). For example, a health education intervention may be delivered in the school setting, with an aim for youth to be more physically active at home. Unless specific and logical efforts are made to connect or align the delivery setting with the behavior setting, the effectiveness of the intervention will be low (Rosenkranz, Citation2020). Unless interventions aim to ensure that conducive social and physical environmental supports have been structured or arranged within the behavior setting, then the delivered intervention will be ineffective (this gap is further discussed under the Goal 2 section below).

Physical activity interventions within schools and other youth settings

For effective and efficient physical activity interventions, we need to consider what happens and who decides what happens within the settings where youth spend ample time each day (Poland et al., Citation2009). Physical activity promotion efforts may thereby benefit from avoiding the overreliance on individual-level influences by taking a settings-based approach (Whitelaw et al., Citation2001). On average, schools typically offer only about 4 min of MVPA per hour (Tassitano et al., Citation2020), but due to their near-universal reach of youth, schools are considered a setting of primary importance to promote physical activity (Lavizzo-Mourey et al., Citation2012). Besides the home, no other setting has more contact with children and adolescents; therefore, schools promote an efficiency in coordinated and simultaneous intervention delivery (Borde et al., Citation2017). Pragmatic physical activity interventions (those designed to be ecologically valid and readily capable of facilitating the translation of research findings) tend to be designed with teachers and other school personnel as settings-based intervention delivery agents. These personnel thereby become de facto youth setting physical activity leaders.

Teachers strongly influence what students do within the classroom, so teachers play a fundamental role in determining the effectiveness of school-based physical activity interventions. To expose youth to a school physical activity intervention condition, researchers rely on methods and strategies that include provision of teacher training, teacher continuing education, persuasion to disseminate and implement, or professional development experiences. Interventions may be designed to have classroom teachers add physical activity into their class time in several ways. These include the incorporation of bodily movement into lessons (physically active lessons), the addition of short bursts of physical activity via curriculum-focused active breaks, and the use of active breaks (e.g. recess) that are unrelated to the curriculum (Donnelly et al., Citation2009; Drummy et al., Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2017).

To facilitate implementation of a physical activity intervention, workshops or interactive seminars can be structured to bolster teacher capability and motivation (Borde et al., Citation2017). Intervention researchers have often addressed specific teaching practices or strategies, provided portable equipment, or worked with school personnel to lead environmental changes such as playground markings or permanent sport or playground equipment (Borde et al., Citation2017). Successful implementation of a school-based physical activity intervention is associated with factors such as a supportive school climate, staff characteristics (e.g. self-efficacy and skill proficiency), and the quality of training and support (Naylor et al., Citation2015). Teachers’ attitudes and motivations related to youth physical activity are recognized as the largest barriers to promoting physical activity within the classroom (Martin & Murtagh, Citation2017). Implementing a classroom change is typically made at the ultimate discretion of individual teachers, so it is crucially important that teachers are satisfied with any program, policy, or practices that constitute a school physical activity intervention. Targeting behavior change among classroom teachers (who are effectively the proximal gatekeepers of student MVPA opportunities at school) and developing interventions that complement the teachers’ educational curriculum, schedules, and teaching philosophy may facilitate their physical activity leader behavior (Martin & Murtagh, Citation2017). Evidence suggests that teacher training or professional development programs within school-based interventions are more effective on physical activity leader behavior when: (1) The training or professional development session lasts at least one full day; (2) It provides comprehensive content on the subject and how it can be taught; (3) It uses a theoretical framework; (4) It provides follow-up or ongoing support; (5) It measures teacher satisfaction with the professional development or training (Lander et al., Citation2017).

Besides classroom teachers, school-based interventions implemented by physical education (PE) teachers can effectively increase the proportion of time spent in MVPA during PE classes (Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Sanders, et al., Citation2013). Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Peralta, et al. (Citation2013) reviewed various interventions that were characterized as either enhancing the quality of PE through specific teaching strategies, or by the addition or substitution of certain active sports, fitness activities, or games to replace less active time. Interventions implemented by other youth setting leaders (besides classroom or PE teachers) can be effective for increasing physical activity during the time spent within their settings. After-school programs typically provide about 12 min of MVPA per hour, and some interventions have been successful at increasing youth physical activity within this setting (Dzewaltowski et al., Citation2010; Gortmaker et al., Citation2012; Mears & Jago, Citation2016).

In the youth sport setting, evidence indicates that youth typically obtain about 21 min of MVPA per hour (Tassitano et al., Citation2020). Some recent interventions have been successful at increasing the percentage of time spent in MVPA by promoting efficiency and reducing the time that coaches spend managing youth behavior (Guagliano, Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Kolt, et al., Citation2015; Guagliano, Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Parker, et al., Citation2015; Pfeiffer & Wierenga, Citation2019; Weintraub et al., Citation2008). Youth development settings such as summer camps (Guagliano et al., Citation2017) and scouting (Jago et al., Citation2006; Rosenkranz et al., Citation2010; Rydell et al., Citation2005) have featured successful physical activity level increases within those settings, and usually have more room for MVPA improvement compared to youth sport or PE. The youth setting leaders within after-school programs, other out-of-school-hours care, youth sport, scouts, and camps are subject to similar influences, barriers, and facilitators to physical activity promotion as those of the teachers, described above. Each setting will vary, however, and the leaders and setting characteristics can differ in meaningful ways (see and ). Logically, interventions need to be context-specific and ensure that physical activity leaders are provided with an intervention (including policies, practices, programs, or tools) that not only has evidence of effectiveness, but is also satisfactory and relevant to them. Such an intervention would entail appropriate professional development experiences, training, and support to build capability and motivation to implement the intervention effectively.

Table 1. Components of the COM-B framework of physical activity across levels of youth settings.

Table 2. Setting-specific intervention design considerations for capabilities, opportunities, and motivations to increase physical activity behaviors within the setting.

Moving toward a comprehensive and robust theoretical framework: The COM-B model

Recently, the COM-B model of behavior change has gained traction as a comprehensive and elegant integration of behavioral theory components and behavior change mechanisms (Michie et al., Citation2011). The origins of COM-B lie not only in psychological and behavioral theory, but also in the American criminal justice system (Michie et al., Citation2011). The COM-B model forms the hub of a behavior change wheel, a practical guide and toolkit that is now being widely used to design and select interventions and policies. The COM-B and broader behavior change wheel represent a synthesis of 19 behavior change frameworks that draw on a wide range of disciplines and approaches (Michie et al., Citation2011).

The COM-B model is particularly useful for settings-based physical activity interventionists because it simplifies the landscape of what is often esoteric and inaccessible theoretical terminology and ideology within psychological and behavioral theory. According to the COM-B model, for a given behavior (B) such as physical activity to occur, there must be sufficient capability (C), opportunity (O), and motivation (M) present. All three components are essential, and to the degree that any of these components is weak or lacking, the behavior has lower likelihood of occurrence. If the cumulative collection of capability, opportunity, and motivation were stronger for an interfering behavior (e.g. playing sedentary video games or transportation via automobile) of the intended physical activity, the interfering behavior would theoretically prevail. Thus, inactive behaviors would prevent or reduce the time spent in MVPA. In accordance with our aim to address critically relevant concepts, principles, and evidence from the literature to guide physical activity leader behavior interventions, the following section offers an exploration of the capability, opportunity, and motivation components of COM-B, as applied to youth physical activity. After exploration of COM-B components at the individual youth level, the model will be extended to setting-level characteristics and physical activity leader behavior within settings.

Capability: Capability is a key component of physical activity for youth, comprising both physical and psychological determinants of whether or not the behavior can be performed. Physical capability includes various dimensions of health-related and skill-related fitness (Corbin et al., Citation2000; Simons-Morton et al., Citation1988) that include fundamental movement skills, sport-specific skills, coordination, balance, power, speed, agility, reaction time, strength, flexibility, muscular endurance, body composition, and cardiovascular fitness (Stodden et al., Citation2008). Each specific type of physical activity requires a unique set of these requisite attributes to execute performance of that behavior. Youth who are lacking in a necessary component will not yet be capable of performing that physical activity. Psychological capability includes knowledge, mental skills, self-regulation, and sense of agency or self-efficacy to perform the behavior (Bandura, Citation2001). Certain aspects of capability are dependent on physical maturation and developmental processes, while other aspects are more dependent on instruction, learning, practice, and experiences (Corbin et al., Citation2000). All of the aspects of capability are pertinent to the question of whether the requisite skills and attributes necessary to perform the behavior are present.

Opportunity: The influence of health promotion and public health fields has led to an emphasis on availability and accessibility, or what environmental opportunities – both social and physical – youth can use within the settings where they live, learn, and play. Michie et al. (Citation2011) differentiated physical opportunity from social opportunity. Physical opportunity is described as what is physically present within the environment, and social opportunity is described as the cultural milieu or norms that frame thought and decisions.

These tenets of the COM-B model are consistent with TEO theory in predicting that capability or motivation will not result in sufficient levels of physical activity if youth do not have adequate opportunities to be active. When examining where youth spend time each day, we must consider the ways that opportunities for physical activity are introduced, scheduled, or integrated at home, in transit to and from school, during the school day, after school, in youth development clubs, and even within youth sport programs. Even for sessions devoted to physical activity – such as PE – a majority of class time is inactive, or in light-intensity physical activity (Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Sanders, et al., Citation2013). Only around one-third to one-half of time within youth sport is spent in MVPA (Guagliano et al., Citation2013; Leek et al., Citation2011; Ridley et al., Citation2018). Thus, even opportunities dedicated to sports and exercise may not be efficient or maximally beneficial for facilitating MVPA. All aspects of such opportunities pertain to the question of whether social and physical conditions are conducive to the behavior.

Motivation: Motivation comprises internal organismic processes that influence behavior, based on biological drives, physical or psychological needs, or a dissatisfaction with the current state. Within the COM-B model, motivation is defined as processes of the brain that energize and direct behavior. Motivation thereby includes both automatic and reflective aspects, as derived from dual-process theory (Strack & Deutsch, Citation2004). The automatic aspect of motivation typically involves a tendency to maintain homeostasis through unconscious implicit processes where people merely respond or react without much conscious thought. This form of motivation reflects impulses, emotions, heuristics, and lends itself toward habit formation and maintenance. It also pertains to behavioral scripts, social customs, and the routines followed within many settings, such as a particular warm-up routine in PE class. In contrast, the reflective aspect is conscious, willful, decision-oriented, and purposeful. Reflective motivation involves conscious consideration of why to engage in physical activity or not, with reasons ranging across a continuum from amotivation to types of controlled motivation and more self-determined motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Amotivation is the lack of motivation, while examples of controlled or extrinsic motivation include being physically active to avoid reprimand, or to receive attention or rewards. Self-determined motivation is fostered when basic psychological needs (autonomy, relatedness, competence) are met, and examples include being physically active for the enjoyment it brings, or because it has become an intrinsic part of identity or lifestyle (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). All these aspects of motivation pertain to the question of whether the behavior is worth doing.

The multi-level COM-B theoretical framework to guide physical activity leader interventions in youth settings

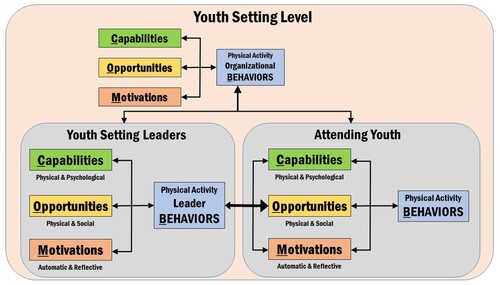

Physical activity interventions tend to focus primarily on behavior change techniques aimed at the individual level of the target population (e.g. youth), while setting-level organizational characteristics and the leaders who are essential in planning, delivering and supporting the intervention activities may not get adequate attention. In acknowledgement of the critical roles of youth setting leaders and setting-level organizational drivers, depicts multi-level COM-B framework for physical activity promotion in youth settings. Within this theoretical framework, capabilities, opportunities, and motivations for leader behaviors among setting-level gatekeepers serve as key determinants of the physical activity levels of attending youth. The COM-B components are multidimensional composites within levels of setting, leader, and youth, so the plural forms are used.

Figure 1. Multi-level COM-B theoretical framework for physical activity promotion in youth settings.

Note: Capability, opportunity, and motivation can be seen as setting-level features for the organization, which then influence the levels of leaders and attending youth. The COM-B components are hypothesized to be multidimensional composites within levels of setting, leader, and youth, so the plural form of each is used. Along with organizational influences, physical activity leader behaviors serve as key determinants of the physical activity levels of attending youth. The physical activity behaviors of attending youth will be the result of their own capabilities, opportunities, and motivations, where these components have been influenced by the behaviors of adult gatekeepers within the setting. Many relationships between COM-B components are reciprocal: Behaviors influence capabilities, opportunities, and motivations, and the COM-B components of youth have influence on the organization and youth setting physical activity leader behaviors.

Youth setting leader behaviors include making determinations such as: (1) How much programming time (if any) is devoted to providing opportunities for youth MVPA; (2) To what degree active participation is prioritized over competition; (3) To what degree the leaders model and encourage physical activity; (4) Whether specific skills are taught during a physically active session; (5) To what degree the session facilitates physical activity equitably for all youth; (6) To what degree attending youth have the opportunity to make choices; and (7) To what degree physically active sessions are designed to be enjoyable and equitable for all youth. The physical activity behaviors of attending youth are the result of their own capabilities, opportunities, and motivations. Youth COM components, however, are influenced by the setting-level drivers and leader behaviors within the setting. Furthermore, many of the relationships between COM-B components are reciprocal, so behaviors influence capabilities, opportunities, and motivations, and the COM-B components of attending youth have an influence on the physical activity leader behaviors of youth setting leaders. As suggested by Michie et al. (Citation2011) within either the youth or leader levels, capabilities and opportunities are influential on motivations for behavior.

further summarizes key components of the multi-level COM-B framework of physical activity across levels within youth settings, and provides example descriptions of capabilities, opportunities, motivations, and behaviors for the setting, for youth setting leaders, and for attending youth. Capability, opportunity, and motivation are often characterized at the individual level, but characterizes those components as relevant to the setting itself, to youth setting leaders, as well as to attending youth. The table includes how capabilities, opportunities, and motivations are extended conceptually to multiple levels of the setting.

Consistent with a settings-based approach, a strong focus on environmental context is required. This necessitates an understanding of the primary roles and aims of the setting, how decisions are made, what routines and regular practices have been established, and who the decision-makers or gatekeepers within the setting are. Youth have limited agency to select settings, and they also have limited ability to determine how physically active they can be within those settings. In looking across the entirety of daily life, youth typically enter and exit various settings, with heterogeneity in physical activity opportunities. Within settings such as schools (Chen et al., Citation2018), youth sport (Schlechter, Guagliano, et al., Citation2018), scouting (Cull et al., Citation2018; Schlechter, Rosenkranz, et al., Citation2018), and after-school programs (Coleman et al., Citation2008), youth setting leaders organize and allocate variously sized blocks of time that can be called sessions, thereby effectively helping or hindering youth in obtaining minutes of health-promoting MVPA.

The adult leaders of youth settings function as gatekeepers to opportunities either to be active or sedentary during the time youth spend at the setting. A working hypothesis stemming from our multi-level COM-B theoretical framework to guide physical activity leader interventions in youth settings is that for youth to be more physically active within the setting, interventions must influence the capabilities, opportunities, and motivations for physical activity leader behaviors among the setting's adult decision makers. Although interventions could focus on the COM-B setting-level organizational drivers, these may be less modifiable drivers than those of the leaders and youth. On the other hand, interventions could focus directly on COM-B of the youth, but that approach would not account for the adult leader gatekeeping issue within the setting. Intervention efforts should therefore benefit by focusing on setting leaders, and by addressing COM-B components to improve physical activity leader behaviors. These leader behaviors should result in the provision of high-quality opportunities for youth, augmented by efforts to enhance the capability and motivation for youth to be active within the setting. The enhanced capabilities and motivations of youth may reciprocally influence the leaders and other parts of the youth setting. The multi-level theoretical framework () portrays the systemic relationships and depicts how intervention efforts can focus on setting leaders, by addressing COM-B components to improve physical activity leader behaviors to achieve more active youth settings.

Specific considerations for designing or selecting interventions in youth settings

Behavior in context is the starting point of intervention design (Michie et al., Citation2011), so gaining an understanding of the physical activity behavioral system within youth settings remains crucial. Interventionists often begin with a broad approach, then work on the specifics of intervention design, followed by determining the intervention components, such as selecting evidence-based behavior change techniques (Michie et al., Citation2011). Michie et al's. (Citation2011) behavior change wheel offers one structured approach to intervention development, but intervention mapping, logic models, or other systems are also frequently used. Due diligence entails gathering data and taking steps to understand the setting, its leaders, participants, and other relevant stakeholders. The intervention development process often involves identification of resources, constraints, strengths, limitations, and values, along with identification of both modifiable and non-modifiable drivers of physical activity within the setting.

provides examples of setting-specific considerations when designing interventions for youth leaders’ capabilities, opportunities, and motivations to promote physical activity behavior (focusing mainly on MVPA within the setting). It is important to acknowledge the primary role and characteristics specific to each setting to address barriers effectively, and to take advantage of available facilitators to enhance physical activity levels in youth. PE and youth sport are key settings where a primary role is to improve youths’ capability to perform physical activity by improving fundamental and sport-specific movement skills. These settings have the advantage of consistent attendance and less competition or interference from other activity choices or competing demands. Interventions in these settings could enhance teachers’ and coaches’ capabilities and motivations by providing professional development experiences focused on contemporary, evidence-based pedagogical techniques for both skill learning and for optimizing physical activity time; using strategies such as avoiding the use of long lines and elimination games, maximizing the amount of equipment being used, and reducing stationary instructional time (Foster et al., Citation2010; Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Peralta, et al., Citation2013; Lubans et al., Citation2017).

In contrast, settings such as school break times (i.e. recess) and out-of-school-hours care may encompass larger groups of children, spread across a variety of play spaces, offering more discretion for children over their activities. Due to background differences in previous education and training (whether formal or informal), teachers and leaders within these settings are likely to have gaps in knowledge and lack confidence pertaining to promotion of physical activity. In these settings, physical activity interventions can likely make large gains by targeting expanded, extended, or enhanced opportunity for children to be active. Leaders could benefit from training and support to boost capability and motivation to promote active options, such as facilitating active games, while restricting the availability of sedentary options via no-screen-time policies at out-of-school-hours care, or adopting compulsory outdoor breaks. Community-based programs sometimes resemble the classroom setting at school, where the aim is to provide youth development activities or instruction other than PE or sport. Leaders within these types of settings may benefit from education and training on incorporation of physical movement within lessons.

Can we use the COM-B theoretical framework to yield more active youth, or merely more active youth settings?

As discussed above, examples of successful interventions to increase within-setting MVPA are plentiful among schools (Kriemler et al., Citation2011), after-school programs (Mears & Jago, Citation2016), physical education (Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Sanders, et al., Citation2013), sport (Pfeiffer & Wierenga, Citation2019) and elsewhere. In many cases, the key component addressed by those successful interventions consists of increased opportunity, with a lesser focus on youth capability and motivation. Conversely, examples of successful interventions to increase overall/daily physical activity among youth are much more rare in the literature, and systematic reviews indicate that most interventions fail to result in significantly greater daily minutes of MVPA (Dobbins et al., Citation2013; Love et al., Citation2019; Metcalf et al., Citation2012). An example of a high-quality study with equivocal findings is the Active by Choice Today school-based randomized controlled trial that sought to increase MVPA of adolescents from low-income and minority households (Wilson et al., Citation2011). In that trial, the intervention consisted of 17 weekly sessions that focused on youths’ motivational and behavioral skills over the course of an academic year. Results showed an intervention effect on MVPA during the time that the program was in session, and a difference of about 5 min of MVPA per day between youth in the intervention and control conditions at mid-point assessment. So, the intervention seemed to be yielding more active youth midway through the trial. Unfortunately, both the primary outcome of overall MVPA after the intervention and physical activity outside of school times failed to show intervention effectiveness.

The frequently observed interventions that show limited effectiveness for improving overall/daily MVPA (Dobbins et al., Citation2013; Love et al., Citation2019; Metcalf et al., Citation2012) raise the question of whether settings-based interventions can actually result in youth who are consistently more active overall, or result merely in more active settings. This section will explore that question from several perspectives, and highlight the need for greater clarity in the goals of the intervention. Goals may be to increase physical activity within, beyond, or both within and beyond the setting. There are several theories and evidence-based approaches that could be particularly useful, each discussed below.

Youth vary in their capabilities and motivations for physical activities. Adult leaders and settings themselves also vary in their unique characteristics relevant to physical activity promotion. To what degree we should focus on individual youth, their leaders, and their settings presents a multi-level problem in efforts to increase MVPA. An ability to yield more active youth could be questioned as to whether it is necessary or sufficient to change either the youth or their environment to increase physical activity levels. Is there a way to change youth so that they will be active irrespective of environment? Considering the principles of setting theory (Whitelaw et al., Citation2001), this is unlikely for most youth. Could we focus only on the environment then? Considering the principles of the COM-B framework (Michie et al., Citation2011), this too looks improbable. Our theoretical framework () adds the additional complexity of ecological levels to COM-B. The framework suggests a need to address both the youth and the environment for best physical activity results, but the degree to which intervention components are designed to influence the youth or environment must be strategically aligned with the goals and level of the intervention.

Regarding intervention goals, a major gap in the current literature is the lack of clarity regarding whether or not settings-based interventions are designed and evaluated in relation to increasing overall/daily physical activity (or toward achieving the guidelines of 60 min of MVPA per day). It is neither necessary nor realistic for every setting-based intervention to take on this rather challenging goal. It may be more appropriate, based on the available resources, to focus on increasing MVPA within the boundaries of the setting itself. We argue that researchers of physical activity interventions in youth settings need to be explicit and deliberate about framing intervention goals to increase MVPA within the setting, beyond the setting, or both within and beyond the setting.

Goal 1: Settings-based interventions could help leaders to increase youths’ MVPA within the setting

As per TEO theory (Beets et al., Citation2016), MVPA could be increased by expanding, extending, or enhancing opportunities of youth in attendance. Lonsdale, Rosenkranz, Peralta et al. (Citation2013) described how interventions were able to increase MVPA either by making changes to teaching strategies, or by having teachers swap certain activities to replace less active time. In addition, several evidence-based guidelines, practices, or systems have been developed to assist youth setting leaders in efficiently and effectively providing a variety of enjoyable, developmentally appropriate physical activities (Lubans et al., Citation2017). According to our theoretical framework, interventions would need to target capability or motivation for leaders to adopt and implement these evidence-based methods to increase youth MVPA.

In the Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) guidelines, emphasis is placed on selecting enjoyable activities and learning effective management practices to engage all youth in physical activity (Kelder et al., Citation2003, Citation2005). For example, CATCH emphasizes keeping recreational activity instructions simple, having youth learn the rules of games gradually while playing, minimizing wait time in lines or queues by providing enough equipment for all youth, and dividing large groups into small groups using grids. Alternatively, LET US Play practical guidelines involve the avoidance of both elimination games and standing in lines, the reduction of team sizes to give youth more chances to be involved, and the provision of additional equipment so that wait times are reduced (Brazendale et al., Citation2015).

Youth setting leaders could also enhance the quality of physical activity opportunities by following SAAFE principles (Lubans et al., Citation2017). These teaching principles involve efforts to be supportive, active, autonomous, fair, and enjoyable. Accordingly, physical activity opportunities need to support the psychological needs of youth, and strive to be efficient with time for activity. They should allow ample autonomy, and ensure fairness and enjoyment for all youth (Lubans et al., Citation2017). Despite the availability and evidence for effectiveness of CATCH, LET US Play, and SAAFE, youth setting leaders vary in their readiness and capacity to adopt and implement the principles and guidelines successfully. Interventions need to take leader, setting, and target population characteristics (see and ) into account, from the formative stages onward. Intervention researchers should pay heed to recommendations described above (Martin & Murtagh, Citation2017) on training and professional development to address capabilities and motivations of youth setting leaders.

Goal 2: Settings-based interventions could help leaders to increase youths’ overall/daily MVPA beyond the setting

To realize the goal of increasing youth MVPA beyond the setting, intervention efforts need to be more deliberate and careful in planning how to reach or coordinate across the various settings where youth spend time over the course of each full day. Such efforts could involve simultaneously targeting physical activity leaders at multiple settings. To help meet the public health guidelines of 60 min of MVPA daily, it is possible to create sufficiently conducive conditions within one key setting – such as summer camps, childcare, and school – where youth usually spend hours at a time mostly inactive (Tassitano et al., Citation2020) and where they have multiple opportunities to accumulate active minutes (e.g. recess, PE, physically active lessons). Given the other urgent issues on the agenda for these settings, however, it is arguably unfeasible or an unfair expectation that a single setting should provide opportunities for all 60 min. Therefore, multiple settings would need to make contributions to daily MVPA for the goal to be achieved. Researchers may need complex intervention strategies to coordinate across settings or to bridge the gap from delivery setting to additional behavior settings to achieve sustained effects across the whole day (Love et al., Citation2019).

Evidence-based approaches using coordinated delivery settings: Shape-up Somerville provides an example of a whole-of-community approach, with the intervention occurring across a combination of settings within the community (Folta et al., Citation2013). This community-based intervention entailed collaboration with community stakeholders through a participatory, multi-level, systems-based approach. Shape-up Somerville was designed to create environmental and policy change to address all aspects of daily life among youth. Results showed modestly increased participation in organized sports and physical activities, although a measure relevant to meeting physical activity guidelines was not included. True whole-of-community physical activity interventions are rare in the literature, and tend to lack rigor in the measurement of MVPA. It is presently unclear to what extent they may be more effective or sufficiently cost-effective to justify the complexity, as compared to more limited-scale intervention setting approaches.

Evidence-based approaches using a single delivery setting: A straightforward approach to bridge the gap from a delivery setting to a separate behavior setting is assigning physical activity homework, which may boost motivation (albeit initially as controlled or extrinsic motivation) for MVPA. In the PE setting, some researchers have suggested the assignment of homework as a way to meet important objectives and standards, especially those related to maintaining an active lifestyle (Lonsdale, Sanders, et al., Citation2016). Among PE teachers, assigning homework may hold value as a means to spend class time on skill development instead of skill practice or MVPA, which could be done outside of classes (Hill, Citation2018). In a review of studies on homework in PE, the majority of studies showed an increase in physical activity levels as a result of active homework (Hill, Citation2018), but many such studies have weak study designs or other methodological flaws. In the Boy Scouts (Jago et al., Citation2006) or Girl Scouts (Rosenkranz et al., Citation2010; Rydell et al., Citation2005) settings, the motivation of earning physical-activity-related scouting badges can be leveraged for physical activity done at home or in leisure time between troop meetings, but evidence for an increase to overall/daily MVPA has been equivocal and unconvincing.

Another promising example using a single delivery setting is the SCORES cluster-randomized controlled trial, where the intervention included multiple strategies that targeted an extension from primary schools to the students’ community and home environments (Cohen et al., Citation2015). This extension consisted of engagement with local community sport, plus newsletters, a parent evening session, and homework on fundamental movement skills, designed to engage parents and encourage them to support their children's physical activity. At posttest, intervention students showed greater levels of overall/daily MVPA, as well as higher movement skills and cardiorespiratory fitness, as compared to a standard-care control condition.

Success has been achieved in the after-school setting by Gortmaker et al’s. (Citation2012) intervention trial, which sought to increase MVPA both during program time and at home. Their intervention included changes to within-setting practices, plus parent engagement to reach the behavior setting of home through the communication channels of newsletters, handouts, emails, and the use of a family handbook. Despite such promising results at school and after-school, many other physical activity interventions constitute failed attempts to reach parents effectively, or to get parents to adopt and implement intervention components that could effect youth physical activity (O'Connor et al., Citation2009).

Although youth sport would seem to be an apposite setting for coaches to assign the practicing of sports skills or additional fitness and conditioning with MVPA performed at home, there is currently a gap in the peer-reviewed literature for this topic (Guagliano et al., Citation2014). Fenton et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated how coaches vary in autonomy support provided to youth, and that such autonomy support is predictive of autonomous motivation and MVPA. This suggests that coaches may be able to motivate their players to be more physically active overall. Farmer et al. (Citation2020) examined the effectiveness of a community-based Gaelic football intervention among preadolescent Irish girls, including several parental communication and engagement components. Results showed promise on both overall physical activity and psychological wellbeing, but the use of self-report measures was a key limitation.

Potential alternative approaches using a single delivery setting: Understanding whether the influences on motivation to be active within a PE setting could be transferred toward participation in MVPA during leisure time led to the development of the trans-contextual model (Hagger et al., Citation2005). The key premise of this model is that fostering youths’ self-determined motivation toward MVPA will result in the adoption of self-directed physically active pursuits when youth have the discretion to do what they choose and are free from extrinsic motivational contributors (Hagger et al., Citation2005). To be effective in extending a setting-based physical activity leader intervention utilizing the trans-contextual model, the focus within a COM-B framework would be on motivation and capability. Specifically, an intervention would address leaders’ autonomy support to increase youth self-determined motivation and perceived behavioral control for MVPA. According to the trans-contextual model, these increases would then influence intention and likelihood of being active in daily life.

Habit theory offers another alternative approach; it highlights how many behaviors are less determined by making conscious decisions, but rather tend to be the product of routines, feedback loops, and the drive for homeostasis (Gardner, Citation2015). Habits are defined as cognitive-motivational processes that are conceptually distinct from behavior, whereby a learned stimulus-response association leads to an impulse to act, even if behavior does not occur (Gardner, Citation2015). The creation of regular opportunities for MVPA during the school day, such as recess or PE classes, may help foster habitually active youth (within the school setting), where stimulus-response chains set the proper conditions for activity. To extend beyond a setting, interventions would need to consider the context-specific nature of MVPA, possibly with leader training geared toward the facilitation of context-dependent repetition among youth, with the explicit aim of developing situation-action associations, resulting in situationally cued automatic behavioral responses (Wood & Neal, Citation2007). For example, a youth basketball coach could teach players to practice dribbling skills for five minutes each weekday, as soon as they get home from school, and players could track their streaks of daily adherence and share them with coaches.

Besides novel applications or developments of theory, technological innovations may offer dynamic solutions to the gap between intervention delivery setting and behavior setting (Martin et al., Citation2015). Specifically, mobile technologies such as the smartphone, or other information and communications technologies and Internet could extend the reach from a remote intervention delivery setting to nearly any setting where youth spend time and have potential to engage in the target behavior. In the case of youth physical activity interventions, physical activity leaders could employ e-health or m-health technological applications to prompt MVPA at home or in other behavior settings, particularly for adolescents. To bolster COM-B components, leaders could: (1) Use technologies to help youth identify MVPA opportunities in or near their homes; (2) Share videos that demonstrate how to perform a certain activity or nurture self-determined motivation to be active through role modeling; (3) Employ self-monitoring and feedback systems, augmented reality games, geocaching, or active video gaming. Among all of the theory-based and evidence-based approaches discussed in this section, effective interventions would need to bolster capabilities and motivations of youth setting leaders to target youth capabilities, motivations, and possibly help to create or identify existing opportunities for MVPA.

Future physical activity intervention studies

When designing intervention studies, researchers and practitioners benefit from engaging stakeholders, identifying modifiable factors that are amenable to change, and laying out a logical plan or model for how an intervention may be potentially implemented, effective, and maintained over time. The behavior change wheel (Michie et al., Citation2011) provides a useful structure for intervention design and selection of behavior change techniques, but other useful tools and approaches include intervention mapping, logic modeling, or participatory action research. According to the PRACTical planning for Implementation and Scale-up (PRACTIS) guide, active engagement from delivery organizations and stakeholders with focus on characteristics of the system, personnel, and intervention, plus early planning in relation to implementation barriers and facilitators could improve the translation of research into practice (Koorts et al., Citation2018).

For youth settings, a review of the key components of the COM-B model () and setting-specific considerations () is recommended during the early stages of intervention design. Collectively, these components provide examples, and may stimulate thinking about finding extant gaps, identifying function and dysfunction, helping to make any assumptions explicit with regard to the intervention and design of accompanying evaluation plans. An additional consideration may be the age range of attending youth, as the needs and preferences will vary from children to adolescents. In particular, relatedness with peers versus adult leaders, autonomy, and competence for physical activity beyond the setting will likely differ with age and developmental stage.

Intervention efforts can determine to what degree youth leaders currently have the skills, knowledge, confidence, opportunity, and motivation to provide high-quality physical activity within the schedule. Next is to determine how to develop an intervention plan based on relevant theory and evidence that will have effects on the leaders, and subsequent effects on youth skills, knowledge, confidence, motivation, and particularly on opportunity to be active within the setting. Intervention evaluators may benefit from measuring aspects of each component of the COM-B model, and instruments are now emerging in the literature with evidence of good acceptability, test–retest reliability, and discriminant and predictive validity (Keyworth et al., Citation2020). It may also be useful to account for the barriers and enablers to implementation and effectiveness over the short and long term. Although our theoretical framework includes multiple levels, it does not address larger structural or cultural obstacles to increasing physical activity, nor does it help to stave off recent trends encouraging youth to sit more and move less (Singer et al., Citation2009). Instead, the theoretical framework focuses sharply on potentially modifiable determinants of physical activity within the settings where youth spend their time each day.

Conclusion

Smarter efforts are needed to increase physical activity levels within and beyond the settings where youth routinely convene to learn, play, and develop. In those physical activity promotion efforts, the characteristics of settings and leaders must be considered, along with insights from behavioral theory, setting theory, and evidence-based effective interventions. Focusing on physical activity in context provides the starting point for intervention design. Youth setting contexts feature drivers of physical activity that span across levels of youth, to adult leaders, to setting organization. These multi-level drivers include capabilities, opportunities, and motivations that are critically relevant to the design of interventions for increasing youth physical activity.

In the multi-level system of a youth setting, particular focus is warranted for physical activity leader behavior in context, constituting a powerful and modifiable driver of youth physical activity. As a collective synthesis of theory, evidence, and practical considerations, the multi-level COM-B theoretical framework to guide physical activity leader interventions emerges as a tool to target physical activity. Interventions can reach physical activity leaders with training, professional development experiences, implementation support, persuasion, or similar strategies for disseminating innovation programs, policies, and practices. By using the framework to address COM-B components, physical activity leader behaviors can change to foster the provision of high-quality MVPA opportunities for attending youth, including emphasis on capabilities and motivations of youth as needed. Complementary additional specific theories for strengthening the capability, opportunity, and motivation of youth, leaders, or setting may be useful for planning and evaluation of effectiveness. The evidence-based systems and guidelines of CATCH, LET US Play, and SAAFE also add value for promoting within-setting MVPA.

Intervening within a setting can increase minutes of within-setting MVPA, but it is unlikely to provide the complete solution to physical inactivity among youth. When the goal shifts from MVPA within a setting toward the goal of 60 min of daily MVPA, a strategically designed plan addressing capabilities, motivations, and the identification or creation of additional opportunities will be especially important. The application of behavioral theories offers promise, but the gap between delivery setting and behavior setting will need to be bridged. Technological innovations are emerging to help bridge this gap, but technology alone is unlikely to suffice. Another extant gap concerns theoretical fidelity of interventions, and whether better fidelity improves effectiveness. To move science and practice forward, future studies can address these gaps and test the multi-level COM-B theoretical framework, with an aim to benefit populations of youth by increasing levels of physical activity.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Flinders University Honorary Visiting Scholar host, Professor Anthony Maeder. RR conceptualized the review, with inputs by KR, JG, and SR. RR composed the figure, structure of the manuscript, and the first draft of most sections. JG, KR, and SR contributed to the writing of parts of the manuscript and tables, and revised the article for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aubert, S. , Barnes, J. D. , Abdeta, C. , Nader, P. A. , Adeniyi, A. F. , Aguilar-Farias, N. , Tenesaca, D. S. A. , Bhawra, J. , Brazo-Sayavera, J. , Cardon, G. , Chang, C. K. , Nyström, C. D. , Demetriou, Y. , Draper, C. E. , Edwards, L. , Emeljanovas, A. , Gába, A. , Galaviz, K. I. , González, S. A. , … Tremblay, M. S. (2018). Global matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: Results and analysis from 49 countries. Journal of Physical Activity and Health , 15 (S2), S251–S273. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2018-0472

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology , 52 (1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Baranowski, T. , Anderson, C. , & Carmack, C. (1998). Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions: How are we doing? How might we do better? American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 15 (4), 266–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00080-4

- Barker, R. G. (1968). Ecological psychology. Concepts and methods for studying the environment of human behavior . Stanford University Press.

- Beets, M. W. , Okely, A. , Weaver, R. G. , Webster, C. , Lubans, D. , Brusseau, T. , Carson, R. , & Cliff, D. P. (2016). The theory of expanded, extended, and enhanced opportunities for youth physical activity promotion. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity , 13 (1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0442-2

- Borde, R. , Smith, J. J. , Sutherland, R. , Nathan, N. , & Lubans, D. R. (2017). Methodological considerations and impact of school-based interventions on objectively measured physical activity in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews , 18 (4), 476–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12517

- Brazendale, K. , Chandler, J. L. , Beets, M. W. , Weaver, R. G. , Beighle, A. , Huberty, J. L. , & Moore, J. B. (2015). Maximizing children's physical activity using the LET US Play principles. Preventive Medicine , 76 , 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.012

- Chen, S. , Dzewaltowski, D. A. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , Lanningham-Foster, L. , Vazou, S. , Gentile, D. A. , Lee, J. A. , Braun, K. J. , Wolff, M. M. , & Welk, G. J. (2018). Feasibility study of the SWITCH implementation process for enhancing school wellness. BMC Public Health , 18 (1), 1119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6024-2

- Cohen, K. E. , Morgan, P. J. , Plotnikoff, R. C. , Callister, R. , & Lubans, D. R. (2015). Physical activity and skills intervention: SCORES cluster randomized controlled trial. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 47 (4), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000452

- Coleman, K. J. , Geller, K. S. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , & Dzewaltowski, D. A. (2008). Physical activity and healthy eating in the after-school environment. Journal of School Health , 78 (12), 633–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00359.x

- Corbin, C. B. , Pangrazi, R. P. , & Franks, B. D. (2000). Definitions: Health, fitness, and physical activity. President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports Research Digest , 3 (9), 1–9. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED470696.pdf

- Cull, B. J. , Dzewaltowski, D. A. , Guagliano, J. M. , Rosenkranz, S. K. , Knutson, C. K. , & Rosenkranz, R. R. (2018). Wellness-promoting practices through Girl Scouts: A pragmatic superiority randomized controlled trial with additional dissemination. American Journal of Health Promotion , 32 (7), 1544–1554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118754825

- Dobbins, M. , Husson, H. , DeCorby, K. , & LaRocca, R. L. (2013). School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 2 , https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub2

- Donnelly, J. E. , Greene, J. L. , Gibson, C. A. , Smith, B. K. , Washburn, R. A. , Sullivan, D. K. , DuBose, K. , Mayo, M. S. , Schmelzle, K. H. , & Ryan, J. J. (2009). Physical activity across the curriculum (PAAC): A randomized controlled trial to promote physical activity and diminish overweight and obesity in elementary school children. Preventive Medicine , 49 (4), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.022

- Drummy, C. , Murtagh, E. M. , McKee, D. P. , Breslin, G. , Davison, G. W. , & Murphy, M. H. (2016). The effect of a classroom activity break on physical activity levels and adiposity in primary school children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health , 52 (7), 745–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13182

- Dzewaltowski, D. A. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , Geller, K. S. , Coleman, K. J. , Welk, G. J. , Hastmann, T. J. , & Milliken, G. A. (2010). HOP'n after-school project: An obesity prevention randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity , 7 (1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-90

- Farmer, O. , Cahill, K. , & O’Brien, W. (2020). Gaelic4Girls—the effectiveness of a 10-week multicomponent community sports-based physical activity intervention for 8 to 12-year-old girls. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 17 (18), 6928. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186928

- Fenton, S. A. M. , Duda, J. L. , Quested, E. , & Barrett, T. (2014). Coach autonomy support predicts autonomous motivation and daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary time in youth sport participants. Psychology of Sport and Exercise , 15 (5), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.04.005

- Folta, S. C. , Kuder, J. F. , Goldberg, J. P. , Hyatt, R. R. , Must, A. , Naumova, E. N. , Nelson, M. E. , & Economos, C. D. (2013). Changes in diet and physical activity resulting from the Shape Up Somerville community intervention. BMC Pediatrics , 13 (1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-157

- Foster, K. E. , Behrens, T. K. , Jager, A. L. , & Dzewaltowski, D. A. (2010). Effect of elimination games on physical activity and psychosocial responses in children. Journal of Physical Activity and Health , 7 (4), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.7.4.475

- Gardner, B. (2015). A review and analysis of the use of ‘habit’ in understanding, predicting and influencing health-related behaviour. Health Psychology Review , 9 (3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.876238

- Glanz, K. , Rimer, B. K. , & Viswanath, K. (2015). Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice . John Wiley & Sons. http://transformationalchange.pbworks.com/f/HealtBehavior-Education.pdf

- Gortmaker, S. L. , Lee, R. M. , Mozaffarian, R. S. , Sobol, A. M. , Nelson, T. F. , Roth, B. A. , & Wiecha, J. L. (2012). Effect of an after-school intervention on increases in children’s physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 44 (3), 450–457. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182300128

- Gray, C. E. , Larouche, R. , Barnes, J. D. , Colley, R. C. , Bonne, J. C. , Arthur, M. , Cameron, C. , Chaput, J.-P. , Faulkner, G. , & Janssen, I. (2014). Are we driving our kids to unhealthy habits? Results of the active healthy kids Canada 2013 report card on physical activity for children and youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 11 (6), 6009–6020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606009

- Guagliano, J. M. , Lonsdale, C. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , Kolt, G. S. , & George, E. S. (2014). Do coaches perceive themselves as influential on physical activity for girls in organised youth sport? PLoS ONE , 9 (9), e105960. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105960

- Guagliano, J. M. , Lonsdale, C. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , Kolt, G. S. , & George, E. S. (2015). Increasing girls’ physical activity during a short-term organized youth sport basketball program: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport , 18 (4), 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2015.01.014

- Guagliano, J. M. , Lonsdale, C. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , Parker, P. D. , Agho, K. E. , & Kolt, G. S. (2015). Mediators effecting moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and inactivity for girls from an intervention program delivered in an organised youth sports setting. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport , 18 (6), 678–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2015.05.005

- Guagliano, J. M. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , & Kolt, G. S. (2013). Girls’ physical activity levels during organized sports in Australia. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 45 (1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31826a0a73

- Guagliano, J. M. , Updyke, N. J. , Rodicheva, N. V. , Rosenkranz, S. K. , Dzewaltowski, D. A. , Schlechter, C. R. , & Rosenkranz, R. R. (2017). Influence of session context on physical activity levels among Russian girls during a summer camp. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 88 (3), 352–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2017.1331291

- Hagger, M. S. , Chatzisarantis, N. L. , Barkoukis, V. , Wang, C. , & Baranowski, J. (2005). Perceived autonomy support in physical education and leisure-time physical activity: A cross-cultural evaluation of the trans-contextual model. Journal of Educational Psychology , 97 (3), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.376

- Hill, K. (2018). Homework in physical education? A review of physical education homework literature. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 89 (5), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2018.1440263

- Houghton, S. , Hunter, S. C. , Rosenberg, M. , Wood, L. , Zadow, C. , Martin, K. , & Shilton, T. (2015). Virtually impossible: Limiting Australian children and adolescents daily screen based media use. BMC Public Health , 15 (1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-15-5

- Jago, R. , Baranowski, T. , Baranowski, J. C. , Thompson, D. , Cullen, K. W. , Watson, K. , & Liu, Y. (2006). Fit for life Boy Scout badge: Outcome evaluation of a troop and Internet intervention. Preventive Medicine , 42 (3), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.010

- Kelder, S. , Hoelscher, D. M. , Barroso, C. S. , Walker, J. L. , Cribb, P. , & Hu, S. (2005). The CATCH kids club: A pilot after-school study for improving elementary students’ nutrition and physical activity. Public Health Nutrition , 8 (2), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2004678

- Kelder, S. H. , Mitchell, P. D. , McKenzie, T. L. , Derby, C. , Strikmiller, P. K. , Luepker, R. V. , & Stone, E. J. (2003). Long-term implementation of the CATCH physical education program. Health Education and Behavior , 30 (4), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198103253538

- Keyworth, C. , Epton, T. , Goldthorpe, J. , Calam, R. , & Armitage, C. J. (2020). Acceptability, reliability, and validity of a brief measure of capabilities, opportunities, and motivations (“COM-B”). British Journal of Health Psychology , 25 (3), 474–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12417

- Knuth, A. G. , & Hallal, P. C. (2009). Temporal trends in physical activity: A systematic review. Journal of Physical Activity and Health , 6 (5), 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.6.5.548

- Koorts, H. , Eakin, E. , Estabrooks, P. , Timperio, A. , Salmon, J. , & Bauman, A. (2018). Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: The PRACTIS guide. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity , 15 (1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0678-0

- Kriemler, S. , Meyer, U. , Martin, E. , Van Sluijs, E. , Andersen, L. , & Martin, B. (2011). Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: A review of reviews and systematic update. British Journal of Sports Medicine , 45 (11), 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090186

- Lander, N. , Eather, N. , Morgan, P. J. , Salmon, J. , & Barnett, L. M. (2017). Characteristics of teacher training in school-based physical education interventions to improve fundamental movement skills and/or physical activity: A systematic review. Sports Medicine , 47 (1), 135–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0561-6

- Lavizzo-Mourey, R. , Dorn, J. M. , Fulton, J. E. , Janz, K. F. , Lee, S. M. , McKinnon, R. , Pate, R. R. , Pfeiffer, K. A. , Young, D. R. , & Troiano, R. P. (2012). Physical activity guidelines for Americans mid-course report: Strategies to increase physical activity among youth . Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/pag-mid-course-report-final.pdf

- Leek, D. , Carlson, J. A. , Cain, K. L. , Henrichon, S. , Rosenberg, D. , Patrick, K. , & Sallis, J. F. (2011). Physical activity during youth sports practices. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine , 165 (4), 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.252

- Lonsdale, C. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , Peralta, L. R. , Bennie, A. , Fahey, P. , & Lubans, D. R. (2013). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to increase moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in school physical education lessons. Preventive Medicine , 56 (2), 152–161. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.004

- Lonsdale, C. , Rosenkranz, R. R. , Sanders, T. , Peralta, L. R. , Bennie, A. , Jackson, B. , Taylor, I. M. , & Lubans, D. R. (2013). A cluster randomized controlled trial of strategies to increase adolescents’ physical activity and motivation in physical education: Results of the motivating active learning in physical education (MALP) trial. Preventive Medicine , 57 (5), 696–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.09.003

- Lonsdale, C. , Sanders, T. , Cohen, K. E. , Parker, P. , Noetel, M. , Hartwig, T. , Vasconcellos, D. , Kirwan, M. , Morgan, P. , Salmon, J. , Moodie, M. , McKay, H. , Bennie, A. , Plotnikoff, R. , Cinelli, R. L. , Greene, D. , Peralta, L. R. , Cliff, D. P. , Kolt, G. S. , … Lubans, D. R. (2016). Scaling-up an efficacious school-based physical activity intervention: Study protocol for the ‘Internet-based Professional Learning to help teachers support Activity in Youth’ (iPLAY) cluster randomized controlled trial and scale-up implementation evaluation. BMC Public Health , 16 ( 1 ), 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3243-2

- Love, R. , Adams, J. , & van Sluijs, E. M. (2019). Are school-based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta-analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer-assessed activity. Obesity Reviews , 20 (6), 859–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12823

- Lubans, D. R. , Lonsdale, C. , Cohen, K. , Eather, N. , Beauchamp, M. R. , Morgan, P. J. , Sylvester, B. D. , & Smith, J. J. (2017). Framework for the design and delivery of organized physical activity sessions for children and adolescents: Rationale and description of the ‘SAAFE’ teaching principles. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity , 14 (1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0479-x

- Martin, N. J. , Ameluxen-Coleman, E. J. , & Heinrichs, D. M. (2015). Innovative ways to use modern technology to enhance, rather than hinder, physical activity among youth. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 86 (4), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2015.1009205

- Martin, R. , & Murtagh, E. M. (2017). Effect of active lessons on physical activity, academic, and health outcomes: A systematic review. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 88 (2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2017.1294244

- Mears, R. , & Jago, R. (2016). Effectiveness of after-school interventions at increasing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels in 5- to 18-year olds: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine , 50 (21), 1315–1324. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094976

- Messing, S. , Rütten, A. , Abu-Omar, K. , Ungerer-Röhrich, U. , Goodwin, L. , Burlacu, I. , & Gediga, G. (2019). How can physical activity be promoted among children and adolescents? A systematic review of reviews across settings. Frontiers in Public Health , 7 , 55. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00055

- Metcalf, B. , Henley, W. , & Wilkin, T. (2012). Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54). British Medical Journal , 345 (sep27 1), e5888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5888

- Michie, S. , van Stralen, M. M. , & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science , 6 (1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Naylor, P. J. , Nettlefold, L. , Race, D. , Hoy, C. , Ashe, M. C. , Higgins, J. W. , & McKay, H. A. (2015). Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine , 72 , 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.034

- O'Connor, T. M. , Jago, R. , & Baranowski, T. (2009). Engaging parents to increase youth physical activity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 37 (2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.04.020

- Pfeiffer, K. A. , & Wierenga, M. J. (2019). Promoting physical activity through youth sport. Kinesiology Review , 8 (3), 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2019-0033

- Piercy, K. L. , Troiano, R. P. , Ballard, R. M. , Carlson, S. A. , Fulton, J. E. , Galuska, D. A. , George, S. M. , & Olson, R. D. (2018). The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Journal of the American Medical Association , 320 (19), 2020–2028. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14854

- Poland, B. , Krupa, G. , & McCall, D. (2009). Settings for health promotion: An analytic framework to guide intervention design and implementation. Health Promotion Practice , 10 (4), 505–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909341025