ABSTRACT

Approximately 200,000 coaches cease coaching each year in the United Kingdom alone. The reasons for this dropout are not fully understood, but they could be linked to the stressful nature of coaching and the potential for this to impede health and psychological well-being (PWB). The aim of this meta-synthesis is to systematically search for and draw together the qualitative research evidence on coaches’ experiences of stressors, primary appraisals, emotions, coping, and PWB. Using a rigorous and systematic search protocol, 11 studies were identified, assessed for research quality, and synthesized thematically to generate new insight. The findings highlight the plethora of stressors that coaches can experience, the impact of coaches’ appraisals on PWB, and the coping families that coaches can use to foster adaptation. In doing so, the meta-synthesis deepens our understanding of coaches’ stress transactions and their experiences of PWB. There is a significant lack of qualitative research evidence on coaches’ appraisals and PWB. Qualitative and or longitudinal research is warranted to develop knowledge in these areas. Such research should be used to develop interventions that are applicable to different coaching populations (e.g. working parents and part-time coaches) to help minimize stressors, facilitate positive appraisals and emotions, and foster PWB.

Introduction

Sports coaching is a potentially stressful occupation (*Frey, Citation2007; *Levy et al., Citation2009) not least because coaches are required to maintain their own psychological and physical health and performance whilst supporting the athletes with whom they work (Kelley et al., Citation1999). Psychological stress is defined as ‘a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being’ (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984, p. 19). According to transactional and interactional perspectives of stress (e.g. transactional stress theory: Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; the cognitive-motivational-relational theory of stress and emotion: Lazarus, Citation1991), stressors occur during individuals’ transactions with their environments and can be defined as ‘environmental demands (i.e. stimuli) encountered by an individual’ (Lazarus, Citation1999, p. 329). Individuals appraise stressors based on the pertinence of them to their beliefs, values, goal congruence, and situational intentions (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1987). Appraising can be deliberate and conscious or automatic and largely subconscious (Lazarus, Citation1999), which makes the study of this concept complex (*Didymus, Citation2017). It is typically accepted that appraising consists of two discrete but related processes: (1) primary appraising (i.e. evaluations of whether an encounter is relevant or significant to one’s beliefs, values, goal commitments, and situational intentions) and (2) secondary appraising (i.e. evaluations of the degree of control over a stressor, the available coping resources, and the likelihood of a coping strategy effectively dealing with the situation; see Didymus & Jones, Citationin press).

An individual usually experiences emotions when encountering a stressor, and stressors often trigger increased motivation to cope (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Coping refers to cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage or reduce demands that exceed the resources of that person (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). As is the case with many aspects of stress transactions, coping is a complex phenomenon because it is idiosyncratic, moderated and mediated by various constructs, and dependent not only on the person but also on his or her environment during any given transaction. Effective coping can mitigate negative outcomes of stress and, thus, this process has the potential to influence physical and psychological health (Malik & Noreen, Citation2015). For example, a coach who experiences a stressor relating to team dynamics, appraises this stressor as a threat, is likely to feel anxious, and copes by avoiding the situation, may experience diminished health and avoidance. Alternatively, if the coach experiences the same stressor and appraises it as a benefit, he or she is likely to feel happy, and copes by celebrating with the team, is more likely to experience enhancements in physical and psychological health.

Research that has examined stressors and health (e.g. Britt et al., Citation2005; Didymus et al., Citationin press) highlights that stressors can trigger negatively valenced emotions (e.g. anxiety; Fredrickson, Citation2000). This in turn increases the risk of physical illness (Churchill et al., Citation2017) and stress-related disorders. These factors are estimated to cause half of all work absences and are known to contribute to increased accident rates, employee turnover, and absenteeism (Harnois & Gabriel, Citation2000; Marcatto et al., Citation2016). In a sport context, it is estimated that 20% of coaches cease coaching annually (North, Citation2009), which equates to approximately 200,000 coaches. The reason for this dropout is not fully known but it may be partly due to the aforementioned impact of psychological stress on coaches’ physical and psychological health (O’Connor & Bennie, Citation2006).

One element of psychological health is psychological well-being (PWB), which is a concept that is distinct from but related to psychological stress. Defining PWB is a challenge and there is little consensus among the academic community about how to best do so (see Norris et al., Citation2017). Many researchers have defined PWB according to its dimensions (e.g. hedonia and eudemonia; Robertson & Cooper, Citation2011), rather than capturing the essence of what PWB is (Dodge et al., Citation2012). The lack of agreement in defining PWB has resulted in multiple broad definitions being reported (Gasper, Citation2010), which, although differ in various ways, share some common ground. For example, many definitions focus on the notion of positive functioning (Duckworth et al., Citation2005; Linley et al., Citation2006), whereas others commonly describe PWB as flourishing and indicate that positive relationships and both purpose and meaning in life are essential (Diener, Citation2009; Seligman, Citation2011). To complement our beliefs about the transactional nature of stress, we adopted a well-established theory-based, multidimensional operationalization of PWB (Ryff, Citation1989; Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). This operationalization encompasses six distinct dimensions of wellness that are thought to be consistent among and relevant to men and women of different ages: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, relationships with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995).

To date, PWB has been explored in a variety of occupational settings, including academic and administrative personnel (Jorgensen et al., Citation2013) and health service workers (Karpaviciute & Parkinson, Citation2015). Collectively, this research has identified that a lack of PWB contributes to absenteeism; poorer health; and reduced job satisfaction, morale, and productivity (Harnois & Gabriel, Citation2000; Sparks et al., Citation2001), which can lead an individual to withdraw from their working environment. The systematic quantitative evidence exploring PWB among sports coaches (see, for a review, Norris et al., Citation2017) highlights that three conditions may be needed to facilitate coach PWB: basic psychological needs satisfaction, lack of basic psychological needs thwarting, and self-determined motivation (Alcaraz et al., Citation2015; Bentzen et al., Citation2016a; Stebbings et al., Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2015). Accordingly, coaches who have more self-determined motivation tend to perform better (Gillet et al., Citation2009) and often foster stronger autonomy supportive environments for athletes (Norris et al., Citation2017).

Two published reviews of literature have explored various components of sports coaches’ psychological stress transactions and or PWB. The first was a narrative review (Fletcher & Scott, Citation2010), which assessed some of the literature on stress among coaches and focused specifically on conceptual and definitional issues, theoretical and empirical issues, and implications for applied practice. Although this was a narrative rather than a systematic review and was, therefore, not fully rigorous or replicable, the paper did highlight the significant health and performance costs of psychological stress for coaches. While the current meta-synthesis shares some similarities with the foci of this previous review, Fletcher and Scott (Citation2010) focused on burnout, rather than PWB, as a potentially negative consequence of ineffectively managed stress. However, in recent years positive psychology has changed the foci of investigations exploring the positive aspects of the stress process, including positive outcomes such as personal transformation or growth that enhances the study of optimal functioning, instead of the study of dysfunctions and problems (e.g. Rothmann et al., Citation2011). Although research exploring the negative consequences of stress is useful to understand the impact of stress in individuals, it does restrict conclusions on how to support individuals in achieving optimal functioning and, ultimately, wellbeing. Therefore, following trends in positive psychology, it is important that this meta-synthesis allows for the investigation of positive aspects of the stress process. The lack of a systematic approach in Fletcher and Scott (Citation2010) unfortunately limits the confidence that can be had in the conclusions. Furthermore, the review is now over a decade old and, given the increasing interest in psychological stress and PWB among coaches in recent years, the findings of this work are outdated. This is problematic because practitioners and policy makers require the most up-to-date evidence to inform their practice.

The second more recent review systematically drew together research on stressors, coping, and PWB among sports coaches (Norris et al., Citation2017). This work highlighted that coaches experienced stressors relating to their own and their athletes’ performance, contextual factors (e.g. job security, coach age and experience), and intrapersonal experiences (e.g. athletes, expectations of others). The search strategy adopted by Norris et al. (Citation2017) yielded no qualitative articles and five quantitative articles that examined PWB among coaches. The lack of retrieved qualitative research evidence was perhaps due to the systematic review method that was adopted, and the lack of flexibility that this method affords in translating or interpreting the findings of previous work. While limited previous qualitative work has explicitly explored PWB among coaches, our preliminary scoping searches highlighted that findings do exist that could be interpreted as relevant to PWB.

While these two aforementioned reviews made progress in bringing together the available literature of some aspects of psychological stress and PWB among coaches, they did not consider the pivotal component of appraising (Didymus & Fletcher, Citation2012), coaches’ emotions and/or full understanding of PWB. This is a significant shortcoming of both reviews (Fletcher & Scott, Citation2010; Norris et al., Citation2017) because influential theoretical perspectives (e.g. the cognitive-motivational-relational theory; Lazarus, Citation1999) clearly signify stress as a transactional process that includes appraising and emotions as central tenets and consider appraising to be the pivotal element of stress transactions that has implications for health, performance, and PWB (e.g. Didymus & Fletcher, Citation2012, Citation2017a). Appraising is also accepted as the conceptual link between stressors, coping, and PWB so it is imperative that reviews of literature in this area are inclusive of all available literature on key components of stress transactions. Furthermore, neither reviews considered the cultural (e.g. women coaches and culturally diverse coaching populations) and organizational (e.g. levels of coaching and occupational bases) dynamics of the coaching workforce when considering their directions for future research. Only once work of this nature is complete can we move toward a more comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge, and offer specific, useful, and informed recommendations for future research and practice in this area.

It is imperative that we further the understanding of sports coaches’ experiences of psychological stress, particularly relating to appraising and PWB. Doing so will help to inform evidence based applied stress management interventions and highlight research gaps that need further attention. Building a stronger body of applied, empirical, and theoretical evidence will help academic and front-line communities to create facilitative environments for coaches that foster health and PWB supporting therefore coaches’ retention in the profession. One way to deepen understanding of psychological stress and PWB using the available evidence is via a meta-synthesis of qualitative research (Walsh & Downe, Citation2005). This type of research involves the systematic search, review, and synthesis of qualitative work to draw together published findings and develop new knowledge (Williams & Shaw, Citation2016). Meta-syntheses go beyond the findings and conclusions of primary studies to provide more powerful explanations of the target phenomena (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Furthermore, a meta-synthesis can provide more substantive interpretations than single studies alone (Arman & Rehnsfeldt, Citation2003), increase understanding of a research topic, enhance the transferability of findings from similar qualitative studies (Paterson et al., Citation2001), and offer a point of reference for interested researchers and practitioners. Considering these benefits as well as limitations discussed found in previous reviews in the area of psychological stress and PWB among coaches, the aim of the current meta-synthesis was to systematically search for and draw together the qualitative research evidence on sports coaches’ experiences of stressors, primary appraisals, emotions, coping, and PWB.

Methods

Philosophical position

To augment the rigor of this meta-synthesis (Bishop & Holmes, Citation2013; McGannon et al., Citation2019), we include here details of our ontological and epistemological assumptions. We align best to a constructivist paradigm, which is underpinned by our relativist ontology and subjectivist epistemology. The knowledge we developed when conducting this meta-synthesis was constructed collaboratively between each of the authors when interpreting the coaches’ experiences that are presented in the included studies (Carson et al., Citation2001). Our interpretations of the original findings using theoretical frameworks to guide us led to the development of different and new knowledge to that which was presented in the original studies (Jensen & Allen, Citation1996). For example, this meta-synthesis is the first study to apply Ryff (Citation1989) and Ryff and Keyes (Citation1995) conceptualization of PWB during the interpretation and presentation of sports coaches’ experiences. In being subjective, we understand that the coaches’ experiences are context bound (Smith & Heshusius, Citation1986) and that the data in the included studies will have been influenced by the original researchers’ own philosophical positions. We also believe there are multiple realities about a phenomenon that are constructed in the minds of each coach (Al-Saggaf & Williamson, Citation2006), which reflects our relativist ontological stance.

Study design

A meta-synthesis involves five consecutive stages (O’Connell & Downe, Citation2009): (1) identifying the focus of the meta-synthesis, (2) identifying published literature relevant to the research aim, (3) appraising each relevant study for research quality, (4) identifying and extracting appropriate data and summarizing key themes from each paper, and (5) comparing and synthesizing key themes. This process has been widely used by researchers (e.g. Williams et al., Citation2017) to draw together data from different contexts and to provide evidence for future studies and interventions (Tong et al., Citation2012). The PRISMA-P (Moher et al., Citation2015) guidelines were used throughout the current meta-synthesis to facilitate a systematic and rigorous approach to the search, sift, and review processes. The first named author contributed to each of the five stages of the meta-synthesis while the second and third authors contributed to stages one and three and acted as critical friends during stages two, four, and five.

Identifying published literature relevant to the research aim

Comprehensive and systematic searches for published literature (up to January 31, 2020) were conducted using the following electronic databases: SportDiscus, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. These databases were chosen because, collectively, they provide access to studies relating to sports, sports medicine, health, behavioral psychology, and social sciences in many relevant academic disciplines (e.g. sports psychology, coaching psychology, health psychology). The following search strings were used with each word being searched for at either full text (TX) or abstract (AB) level: ‘coach’ (TX) and ‘stress*’ (AB) and ‘apprais*’ (AB), ‘coach’ (TX) and ‘stress*’ (AB) and ‘emotion’ (AB), ‘coach’ (TX) and ‘stress*’ (AB) and ‘cop*’ (AB), and ‘coach’ (TX) and ‘stress*’ (AB) and ‘well-being*’ (AB).

Additional manual searches were conducted using the websites of journals that housed published articles under embargo or those that were not yet listed on electronic databases. This manual search strategy has been used in other published meta-syntheses (e.g. Tamminen & Holt, Citation2010) and can retrieve literature that does not appear during database searches. We also engaged with citation pearl growing (Schlosser et al., Citation2006) by searching the reference lists of papers included in the meta-synthesis to identify any other publications that may have met our aim. The final strategy used for sourcing literature involved the inclusion of published literature that the research team was aware of and deemed relevant to the meta-synthesis but had not been returned during the searches (Keegan et al., Citation2014).

Five inclusion criteria were applied during each stage of the search strategy. Specifically, articles must have (1) been accessible in full-text format; (2) been published in a peer-reviewed journal; (3) been available in full in the English language; (4) been an empirical study that included qualitative data; and (5) presented data on stressors, primary appraisals, emotions, coping, and or PWB among sports coaches. Mixed-methods studies were included if they contained a qualitative element that could be used for the synthesis (Williams et al., Citation2017).

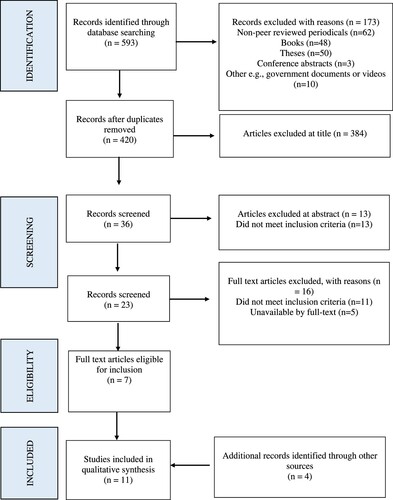

The PRISMA-P diagram (see ) provides an overview of these processes that were used to obtain the final sample of papers. In line with PRISMA-P guidance, articles were initially excluded if they were duplicates or non-peer reviewed sources (e.g. books, theses, conference abstracts). Articles were then sifted at three levels using the inclusion criteria and the aim of this meta-synthesis: (1) title, (2) abstract, and (3) full text. Following the sifting procedures, seven articles met the inclusion criteria and made up the provisional final sample from the electronic database searches. Manual searches of journal websites were then conducted, which returned an additional four papers that were screened using the procedures outlined above. Each of these four papers met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final sample. Citation pearl growing and discussions between the authors about literature we were aware of returned no additional relevant articles.

Appraising each study for research quality

Each study in the provisional final sample was reviewed for research quality, which is an essential methodological element that prevents drawing of conclusions from studies with methodological flaws (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008; Williams & Shaw, Citation2016). In the current study, we followed Garside’s (Citation2014) recommendations for quality assessment in qualitative research to systematically review the quality of each included study. Thus, the first named author reviewed each study in the final sample based on the following three criteria: (1) trustworthiness (e.g. is the design and execution appropriate to the research question?), (2) theoretical considerations (e.g. does the research connect to an existing framework?), and (3) practical considerations (e.g. does the study provide evidence relevant to practice and policy?). The studies were given a score of either zero, one, or two for each of the criteria (0 = does not meet the criteria, 1 = partially meets the criteria, and 2 = meets the criteria). To maximize rigor, a random sample of five papers was then reviewed against the same criteria by the second and third named authors. There were discrepancies relating to four of these five papers whereby one or both of the second and third named authors questioned whether they adequately met the three quality criteria. Following critical discussions between the research team, we deemed that these papers did meet the quality criteria, were relevant to the aim of the meta-synthesis, and could make a useful contribution. Thus, the four papers in question were included in the final sample.

Identifying and extracting data, and summarizing, comparing, and Synthesizing themes

Relevant data from each paper in the final sample were identified and extracted to a Microsoft® Excel® document (cf. Meyer & Avery, Citation2009; see ). Any text in the final sample papers that was labeled ‘results’ or ‘findings’ was extracted and recorded in a column titled ‘key findings’ (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The first named author then coded the extracted data based on its meaning and content. This was an important part of the meta-synthesis because it allowed us to recognize similar concepts in different studies, even if they were not expressed using identical words (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). We followed thematic analysis methods (see Braun et al., Citation2016) to execute coding. This involved six phases that we used recursively: (1) familiarizing with the data by extracting information and reading the results of each published paper; (2) generating initial codes across the data set relating to stressors, primary appraisals, emotions, coping, and PWB; (3) searching for themes within the data and beginning to collate these into sub-themes; (4) reviewing the themes with the research team to ensure each one worked in relation to the coded extracts; (5) defining, naming, and refining themes; and (6) producing this manuscript. The construction of sub-themes was both inductive and deductive (i.e. abductive). To expand, we used pre-defined themes (deductive) that we had generated from previous literature (i.e. Lazarus’ cognitive-motivational-relational theory of stress and emotions, Citation1991; Skinner et al.’s families of coping, Citation2003; and Ryff’s conceptualization of PWB, Citation1989) yet remained open to the generation of new themes and sub-themes throughout our analyses (inductive).

Table 1. Summary of papers in the final sample.

Results

We identified five themes during the thematic synthesis. These were: (1) stressors, (2) primary appraisals, (3) emotions, (4) coping, and (5) impact on PWB. provides a definition for each theme and corresponding studies, the sub-themes within them, and their respective definition. We ask the reader to refer to when reading the results section to review in full which paper(s) related to each theme and sub-theme. Furthermore, because we adopted a subjectivist epistemology, we ask readers to acknowledge that the data presented here is just one interpretation of the coaches’ experiences that were shared in the included studies. Of the 11 studies in the final sample, five used a theoretical underpinning, such as Lazarus (Citation1991) cognitive-motivational-relational theory of stress and emotions, two outlined the authors’ philosophical stance, and one explored the experiences of coaches on voluntary and part-time bases alongside full-time paid coaches.

Table 2. Key definitions and studies in the meta-synthesis.

Stressors

All of the studies included in the final sample offered insight that we interpreted as relevant to coaches’ experiences of stressors. As part of our abductive approach, we remained largely open to themes that could be developed from the data, thus inductive sub-themes were developed within the stressor theme and reflect the coaches’ experiences. These sub-themes (see ) go beyond that which any individual study has presented by translating study findings and by categorizing stressors in a different way to that which published works have tended to do to offer a more nuanced and conceptually distinct approach.

Coaches experienced a multitude of stressors during their roles. Some coaches often experienced stressors related to working with their athletes, such as athletes underperforming, failing to perform to their full potential during training and competition, unhelpful attitudes towards training, and athlete injury. Furthermore, parents of athletes caused the coach to experience stress and often had a detrimental impact on athlete engagement. While coaches had a lot of contact with their athletes, many coaches experienced isolation in their role: ‘I mean it is a solitary role, there is nobody to go to, nobody to talk to’ (an elite coach based in the United Kingdom from *Olusoga et al., Citation2009). Career transitioning, for example from assistant to head coach, required more responsibility and stronger decision-making skills, which was often reported by coaches as being stressful.

Communication was reported as a stressor by coaches. Experiences such as delivering seminars and providing feedback to players were stressful for coaches from a variety of backgrounds. While communicating with athletes was often seen as a stressor, coaches found it a challenge to know what was appropriate to say at certain times, particularly during difficult and challenging phases of the season and ‘communicate on the athlete’s level’ (*Olusoga et al., Citation2012) when working with elite athletes.

Coaches experienced stressors related to competition, such as winning games, playing finals, and rebuilding clubs as a strong competitive side. Furthermore, coaches experienced expectations as a stressor, which often arose from a variety of external sources, including athletes, parents, the media, and national governing bodies (NBGs), as well as expectations coaches had for themselves: ‘You really have to produce, especially in this environment where the expectations are so high. There’s always that pressure of feeling like you have to succeed and supersede what you did the year before’ (a high-performance woman coach, *Durand-Bush et al., Citation2012).

The coaching profession came with challenges relating to financial support and work-life balance for coaches depending on their type of contract or level of coaching. For example, financial support and contract were pertinent stressors for part-time paid coaches and those operating on a self-employed basis. Furthermore, job security was often experienced as a stressor by those at the higher level of coaching and those in full-time paid positions: ‘the reality is what gets you hired or fired is your ability to win or lose’ (a NCAA Division I head coach, *Frey, Citation2007). Work-life balance stressors were experienced by coaches when they felt pressure to meet deadlines to cement their job role, often causing them to take work home and allow coaching to influence their personal life and consequently work-life balance. Furthermore, women had specific experiences related to work-life balance stressors as they also had parental responsibilities to balance alongside coaching and found it challenging to balance home life alongside coaching, which was evident when returning from maternity leave:

When you are a sports coach, there’s no perfect time to have a baby, I didn’t have nine months off from my coaching job. I think the stress of deciding what’s acceptable in your eyes and what’s acceptable in other people’s eyes and dealing with the guilt of the two is always tricky (*Potts et al., Citation2019).

Primary appraisals

The results of the synthesized studies revealed four different types of primary appraisals (challenge, threat, benefit, and harm/loss) used by coaches to appraise the stressors experienced. The types of primary appraisals that are outlined in Lazarus (Citation1999) cognitive-motivational-relational theory proved useful for categorizing the data in this theme. While we were abductive in our analyses, drawing on the well-established existing theoretical works by Lazarus (Citation1999) and the associated definitions of the four types of appraisals (see ) was helpful in guiding our analyses understanding the coaches’ experiences. Our meta-synthesis approach has informed our interpretation of published findings in ways that generated new knowledge of the target phenomenon. For example, while only *Didymus (Citation2017) specifically set out to explore coaches’ primary appraisals in the aim of the study, our meta-synthesis approach allowed for findings to be translated into new knowledge and revealed a further four studies (*Chroni et al., Citation2013; *Durand-Bush et al., Citation2012; *Olusoga et al., Citation2012; *Thelwell et al., Citation2010) that provided experiences related to coaches’ primary appraisals without this being a specific aim of the study or analyzed as such in the results section.

While the coaches provided experiences related to the four types of primary appraisals, the challenge and benefit sub-themes had the fewest experiences reported in the final sample of papers, with only International or Olympic level coaches from *Didymus (Citation2017) study appraising enthusiasm as a challenge or benefit as they had some relevance to goal attainment. Whereas there were more experiences reported relating to threat and harm/loss appraisals across the four additional studies we translated the findings of (*Chroni et al., Citation2013; *Durand-Bush et al., Citation2012; *Olusoga et al., Citation2012; *Thelwell et al., Citation2010). For example, players ‘coasting’ during training were appraised as a threat due to the potential negative impact it could have on shared goals. Furthermore, performance expectations were appraised as a threat: ‘every time you feel you’re being tested, placed under the microscope, evaluating your performance’ (*Chroni et al., Citation2013). Losing players due to incidents in previous matches and being made redundant and having programs canceled were appraised as a harm/loss as they inhibited the coaches’ goals:

I have experienced really quite dramatic things like being made redundant and the program being cancelled. That was a big setback in terms of me, my well-being, and the program … At the time, I certainly remember thinking that the decisions had a detrimental effect on my well-being. I’d go as far as saying that they destroyed it (male Olympic or international level coach, *Didymus, Citation2017).

Emotions

The findings from four studies were interpreted as relating to either positively or negative valenced emotions (see ). First, positively valenced emotions were experienced during game situations, which were often expressed by venting positively valenced emotions:

I love it! I love it! Oh my gosh, I love it. I love being able to go and say, this is what we’re about. I have so much to brag about and get excited about. The home visit is my most enjoyable time because I can share with them my passion (*Frey, Citation2007).

Controlling your emotions is difficult because of your frustrations that come to the surface. You know, I’ve been guilty of getting frustrated and that then has a negative effect on the performance of the team, so you’ve got to learn to control those frustrations and behaviors (a full-time Olympic coach, *Potts et al., Citation2019).

Coping strategies

Ten studies offered insight that we interpreted as relevant to coaches’ coping strategies. The families of coping outlined by Skinner et al. (Citation2003) were used to categorize the data in this theme and the adaptational nature of the families was useful during the construction of our sub-themes (see ). Following our abductive analytical approach, the results of the synthesized studies revealed that coaches used eight of the 12 coping families (see ) outlined by Skinner et al. (Citation2003), each of which plays a different role in adaptive processes (see Didymus & Fletcher, Citation2012; Skinner et al., Citation2003).

Coping strategies such as alcohol use and abuse, taking a holiday, and ceasing engagement were often used to escape stressors: ‘once it gets past a certain point where I think that’s it, we’re not gonna make any headway now, I’m quite happy to just stop and come back later’ (world class coach, *Olusoga et al., Citation2010). Coaches, particularly those from elite, Olympic, and international level, often isolated themselves from stressors they were experiencing in an effort to cope:

I went away to France for two weeks where there was absolutely nothing, turned my phone off … I just needed to get away from the environment and have some time off because I just found that coaching and the demands were getting too much (a woman voluntary coach from *Potts et al., Citation2019).

I would read a lot of books from sports people, a lot of religious books, a lot of business books, management books … you get the chance to be in contact with other sports and they have a lot of courses that you can go on … so I probably have been to every course that there has been. And, you know, you always learn something (an international or Olympic level coach, *Didymus, Citation2017).

You can learn from the stress, yeah … if you can cope with it, learn from it and move on … I think it’s just the environment and it’s an essential part of the environment because I think it’s where most of our learning curves actually take place (world class coach, *Olusoga et al., Citation2010).

Impact on psychological well-being

Within this theme, six studies offered insight that we interpreted as relating to the impact of stress transactions on PWB. Our interpretation of the coaches’ experiences was informed by the works of Ryff (Citation1989) and Ryff and Keyes (Citation1995) combined with an abductive approach, developing the proposed sub-themes (see ). Specifically, five out of their six PWB categories were used when constructing our sub-themes. Only one paper (*Durand-Bush et al., Citation2012) in our final sample explicitly aimed to explore coaches’ PWB, however during the meta-synthesis it was clear that some studies have also explored PWB without purposefully including this aim in their study. This data was analyzed and, as can be seen in the findings (see ), our interpretations of the data brought to the fore a wealth of relevant data from a further five studies that we could use to generate new insights.

A lack of autonomy, by having a lack of control or independence, as per the work of Ryff (Citation1989) and Ryff and Keyes (Citation1995), often resulted in negative ramifications for the coaches. For example, being judged and the impact of expectations or evaluations from others was harmful as the coaches felt they had no control over the ramifications of these. As well as having a lack of autonomy over their work, coaches expressed challenges surrounding their work-life balance and mastering their environment, particularly by balancing both the coaching occupation and the environment in which they operated. This was particularly pertinent among coaches from elite and international coaching backgrounds and impacted their sleep, mood, and personal relationships at home. In line with this finding, women coaches reported an inability to self-regulate during stressful periods which caused a reduction in PWB and was often displayed as physical and/or emotional exhaustion:

I just wanted to curl up in a ball and go to sleep for a few days. And I guess that was probably the climax of my feeling burnout. It was just too much, I felt like I didn’t have a life anymore, I was just doing everything for these kids and there was nothing for me. There was no time to do anytime; there was no time to even recover from illness (a woman coach, *Durand-Bush et al., Citation2012).

To continually get the best out of ourselves, whether it’s coaches, staff, or players, it’s continually trying to improve so that you maintain a competitive spot in the competition and that’s the thing that drives me every day when the alarm goes off in the morning (AFL coach, *Knights & Ruddock-Hudson, Citation2016).

Discussion

The aim of this meta-synthesis was to systematically search for and draw together the qualitative research evidence on sports coaches’ experiences of stressors, primary appraisals, emotions, coping, and PWB. By deepening our understanding of sports coaches’ experiences, this meta-synthesis provides an insightful and powerful explanation of the target phenomena (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Our abductive (i.e. deductive and inductive) analytic approach allowed sub-themes to be constructed, going beyond knowledge presented by individual study. By translating study findings and categorizing them in a synthesized way offers a more nuanced and conceptually distinct approach further understanding in the area of study.

Some of the most notable findings of the meta-synthesis relate to the plethora of stressors that coaches can experience, the impact of coaches’ primary appraisals on PWB, and the coping families that coaches can use to serve different adaptational functions. Another noteworthy finding is that there is a lack of qualitative research evidence that specifically explores coaches’ appraisals and PWB despite our findings indicating that primary appraisals were considered in some studies without being an explicit aim of the paper or a main point of discussion in the results section. Considering the important role of appraisals and the implicit conceptual link with stressors and outcomes of stress transactions (e.g. psychological and physical health, performance), and PWB, further research attention should be dedicated to coaches’ primary appraisals. Accordingly, this knowledge should be used to inform applied interventions, aiming to maximize coaches’ retention within the profession, maintaining health, and enhancing job satisfaction and productivity (cf. Sparks et al., Citation2001).

The impact of stressors on PWB

The results of the thematic synthesis indicate that coaches experience a variety of stressors which often seem to have a detrimental impact on their PWB. For example, our findings align with existing occupational and health literature which highlights the detrimental impact poor working relationships can have on health and PWB (Schaufeli et al., Citation2007; Street et al., Citation2009). This could be mitigated by improving both relationships and communication (Sias, Citation2009), particularly between coaches and their athletes, and building effective social support networks (e.g. via mentoring systems, see Norris et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, developing resilience appears to be an important skill for coaches to acquire to help mitigate some of the negative impacts of stressors experienced and can help coaches on their developmental journey (Sakar & Hilton, Citation2020). Resilience building can protect coaches from the impact of work-related stress (Howard, Citation2008) and burnout, and make them more likely to thrive in stressful situations as observed in other professions (Grant & Kinman, Citation2012). In addition, acknowledging that job insecurity can have a negative impact on an individual’s work attitudes and behavior (Hellgren et al., Citation1999) as well as their psychological health (see, for a review, Sverke et al., Citation2006), it seems imperative that National Governing Bodies dedicate further attention in addressing job insecurity in the coaching profession. This aim should not only improve the PWB of coaching professionals, but also minimize experiences of anxiety, depressive states, and negatively valenced emotions (see also van Vuuren et al., Citation1991). At an organizational level, it seems essential that coaching work environments are as contractually secure as possible and zero hours and temporary coaching contracts are kept to a minimum.

Findings from this meta-synthesis suggest that coaches may be experiencing an ineffective work-life balance, which has been associated in the wider occupational health literature with reduced job and life satisfaction (Allen et al., Citation2000), decreased PWB (Stebbings et al., Citation2012), and burnout (Bentzen et al., Citation2016b; Umene-Nakano et al., Citation2013). Although these findings have still to be confirmed among the coaching profession, our synthesized results indicate that applied interventions for coaches’ PWB should consider effective ways of promoting work-life balance. Following previous organizational findings (Zheng et al., Citation2015), future interventions in this area should consider both individual and organizational level programs when aiming to improve health and PWB. Although women are notably underrepresented across the sport psychology and sport coaching research area (Carson et al., Citation2018; Kenttä et al., Citation2020; Norman & Rankin-Wright, Citation2016), which is problematic in itself, our findings indicate that this population seems to be experiencing increased work-life balance demands reported as stressors, particularly related with maternal duties. These findings support those of other women in different professions (Lyonette et al., Citation2007) and could be due to women striving to accommodate both work and family life (Guillaume & Pochic, Citation2009). Although this can be an enriching balancing act, it can also be a paradoxical equilibrium (Greenhaus & Powell, Citation2006) that exasperates stress (Nomaguchi et al., Citation2005). It is, therefore, essential that National Governing Bodies are mindful when providing support to coaches who are also parents and balancing multiple roles and responsibilities, particularly women coaches to fully understand their demands and inform support interventions. A significant shift in thinking among National Governing Bodies is required to support coaches, for example by providing childcare at competition locations or support for coaches who need to travel to competitions and stay away from the family home.

Appraising and PWB

A lack of literature explicitly exploring primary appraisals among coaches was evident, despite the importance of appraising for PWB (Berjot & Gillet, Citation2011) and other outcomes of stress transactions (e.g. physical health; Lazarus, Citation1999), which could be due to a number of factors. First, just one study (*Didymus, Citation2017) explicitly examined appraisals, yet our meta-synthesis approach and abductive analyses was useful in allowing us to interpret published findings in ways that generated new knowledge of the target phenomenon. Indeed, this approach uncovered further knowledge from four papers (*Chroni et al., Citation2013; *Durand-Bush et al., Citation2012; *Olusoga et al., Citation2012; *Thelwell et al., Citation2010) without appraisals being a specific aim of the study or a main feature of the results sections. Second, the nature of appraising being either deliberate and conscious or automatic and largely unconscious (Lazarus, Citation1999), which means individuals are often unaware of their appraisals (*Didymus, Citation2017), thus making them a challenge to explore. Appraisal is an arbitrary distinction made by theorists to ease the analysis of the conditions that may give rise to emotions (Lazarus, Citation1999). Therefore, future research should adopt in-depth qualitative methods (e.g. longitudinal daily diaries) which are framed to explore individuals’ detailed evaluations of stressors, how they have interpreted the stressors, and the core relational themes underlying emotions to explore appraisals.

Appraising stressors as a threat or harm/loss can mentally and physically exhaust coaches and in the long term can cause damage to well-being (Lazarus, Citation1991), which may be a contributing factor for coaches opting to withdraw from the occupation. Yet, appraising stressors as a challenge are more likely to have positive implications for well-being (Berjot & Gillet, Citation2011). Situational properties of stressors may help to explain why stressors are appraised in different ways and, in turn, the impact on physical and psychological health outcomes (*Didymus, Citation2017; Didymus & Fletcher, Citation2012). Practitioners working with coaches to maximize their PWB should dedicate special attention to how coaches are appraising stressors and, in particular, understand which appraisals have been beneficial for them in the past and find effective ways to reproduce them. This could be done via cognitive restructuring, which can optimize appraisals (see e.g. Didymus & Fletcher, Citation2017b), and via mindfulness practice (Kaiseler et al., Citation2017a). It will also be useful to educate coaches on appraisals and allow them time to examine their own experiences, which will help develop a more solid evidence base on which interventions can be developed.

Emotions and PWB

While negatively valenced emotions (e.g. frustration and upset) can have a detrimental impact on both performance and PWB (Gross & John, Citation2003), positively valenced emotions (e.g. excitement) are thought to trigger an upwards spiral in the enhancement of PWB (Fredrickson & Joiner, Citation2002). Positively valenced emotions can also have a positive impact on an individual’s interpersonal relationships and stress tolerance (Bar-On, Citation2000). Our findings suggest that coaches across some studies found difficulty in regulating their emotions. Further research is warranted to fully understand the context of negative and positive valenced emotions among coaches, which will help inform interventions on ways in which coaches’ experiences of positively valenced emotions could be maximized. One way this could be achieved is via mental health awareness training, which can contribute to positive changes in the emotional climate of performance environments (Sebbens et al., Citation2016). Additionally, the usefulness of applied interventions such as mindfulness and reappraisal proved to be useful to regulate emotions across other populations (e.g. Doll et al., Citation2016) should be investigated among coaches. Finally, developing emotional intelligence among coaches, which is often seen among world-class coaches (Hodgson et al., Citation2017) can help coaches to understand and respond to what is going on in their environment and consistently act in an effective way (Cook et al., Citation2021).

Coping and PWB

The findings are consistent with previous literature, in that families of coping, such as negotiation, information seeking, and problem solving, have been shown to contribute to positive health and PWB (Almassy et al., Citation2014; Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, Citation2009). Furthermore, using negotiation, information seeking, and or problem solving coping strategies can reduce the deterioration of physical health towards the end of a stressful period of time (Park & Alder, Citation2003) and can minimize the potentially harmful effects of stress transactions (Aspinwall & Taylor, Citation1997). Other strategies, such as self-reliance strategies (e.g. visualization) and relaxation techniques (e.g. progressive muscular relaxation), which were drawn on by coaches, can enhance PWB (Edwards & Styen, Citation2008) and can also optimize stress transactions. Furthermore, the development of strong working relationships (van der Kaap-Deeder et al., Citation2017), as the coaches did with their athletes, other experienced coaches, and mentors, are essential for contributing to positive health outcomes (Barbarin et al., Citation1985). In developing such relationships, this will also allow coaches to work with their athletes to cope with shared stressors (Bodenmann, Citation1995, Citation2005) which can maximize PWB for all parties. Future research should explore how developing these helpful types of coping strategies among coaches could be helpful in informing the development of stress management tactics and help to augment PWB.

Drawing on escape and avoidance coping strategies, such as using alcohol, switching off, or sleeping, which were reported by coaches, can contribute to lower PWB (Glidden et al., Citation2006) and can lead to burnout if experienced over a sustained period of time (Lundkvist et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, isolating oneself in an effort to cope with stressors, which was a strategy used by those at the upper echelons of the coaching workforce, can have a detrimental impact on an individual’s PWB (e.g. Brasher et al., Citation2010) and can have wider negative consequences for the coaching workforce in terms of absenteeism and coach turnover. In light of these findings, it seems crucial to further understand what effective coping strategies for coaches are, as these are often the catalyst in determining the outcome of the stressor on the individual, particularly on PWB and other physical and psychological health related outcomes. Future research should explore and understand coaches’ coping effectiveness and whether this could be influenced by other factors, such as personality as observed across the athlete literature (Kaiseler et al., Citation2017b), and the impact of coping effectiveness on wellbeing outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

This meta-synthesis contributes original knowledge by applying rigorous methods to systematically search for and draw together the qualitative research evidence relating to stressors, primary appraisals, emotions, coping, and PWB among sports coaches. The meta-synthesis allowed us to analyze, interpret, and critique (Lachal et al., Citation2017) the relevant sport psychology and coaching psychology literature and to examine coaches’ stress transactions, coping, and their potential impact on PWB. This is also beneficial if we are to offer evidence-based support to practitioners who are designing and using interventions and National Governing Bodies who can make changes at a policy and organizational level. Furthermore, by doing a meta-synthesis of qualitative research, we addressed the aforementioned limitations of previous reviews (c.f. Fletcher & Scott, Citation2010; Norris et al., Citation2017) enabling a rigorous and deepened understanding of sports coaches’ experiences (Williams et al., Citation2017) of psychological stress and PWB. In doing so, we were able to go beyond the findings and conclusions of primary studies to provide more powerful explanations of the experiences being explored (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The knowledge gained during this process has helped to understand and direct future research avenues that must be explored among the coaching profession (e.g. work-life balance, job security, social support networks, and links to PWB). Furthermore, this body of work provides useful knowledge to inform both individual and organizational level interventions.

There are, however, some limitations that should be noted, particularly those relating to the studies reviewed. For example, it is important that qualitative researchers outline their methodological stance (see e.g. Smith & McGannon, Citation2018) to facilitate rigor and allow readers to understand and follow the researcher’s traditions (Bishop & Holmes, Citation2013; McGannon et al., Citation2019). Despite this knowledge, only two studies (*Didymus, Citation2017; *Potts et al., Citation2019) included in this meta-synthesis provided an overview of the researchers’ guiding philosophy (see ). Furthermore, while stressors and coping have received some research attention among coaches, this meta-synthesis calls attention to a dearth of literature on coaches’ primary appraisals, emotions, and PWB. Researchers should make appraisals, emotions, and PWB among coaches the direct foci of future work, not least because of the explanatory potential of appraising but also for the important implications of PWB for coach health and performance.

Conclusions and recommendations for future research

The findings of this meta-synthesis go beyond those of any single study and deepen our understanding of the target phenomena among both men and women coaches from a variety of coaching levels. The findings and discussions of this meta-synthesis allow clarification on the impact that stress transactions can have on coaches’ PWB. For example, stressors relating to working in isolation had a detrimental impact on PWB whilst strong working relationships with athletes often had positive implications for coaches. Our findings relating to coping focus on the families of coping efforts that coaches can use during stressful transactions. In particular, strategies such as negotiation and problem solving were important for increasing and maintaining PWB, whereas strategies such as escape and avoidance can be not only harmful for coaches’ PWB but can have wider negative implications for the coach turnover and absenteeism. Our findings highlight that, whilst coaches clearly experience both positively (e.g. excitement) and negatively (e.g. frustration and upset) valenced emotions during their roles, the final sample of published literature contained limited data on emotions, particularly those that are positively valenced. This warrants further exploration, especially when considering the role that positively valenced emotions can play in nourishing and fostering PWB (Folkman, Citation2008) and the detrimental impact negatively valenced emotions can have on both performance and PWB (Gross & John, Citation2003). It is imperative to continue working with men and women coaches from a variety of coaching backgrounds to understand their experiences, particularly of appraising, emotional responses, and the consequential impact on their PWB. This could be done by adopting longitudinal and prospective research approaches to fully understand stress individual and organizational experiences, and how they relate to coaches’ behavioral and performance-related outcomes. Research of this nature would address significant voids in extant qualitative research evidence and will help to inform the development of a wide range of useful applied interventions addressing coaches individual (e.g. managing negatively valenced emotions) and organizational (e.g. those on operating on part-time or voluntary bases) needs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alcaraz, S., Torregrosa, M., & Viladrich, C. (2015). How coaches’ motivations mediate between basic psychological needs and well-being/ill-being. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 86(3), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2015.1049691

- Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278

- Almassy, Z., Pek, G., Papp, G., & Greenglass, E. R. (2014). The psychometric properties of the Hungarian version of the proactive coping inventory: Reliability, construct validity and factor structure. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 14, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/t65351-000

- Al-Saggaf, Y., & Williamson, K. (2006). Doing ethnography from within a constructivist paradigm to explore virtual communities in Saudi Arabia. Qualitative Sociology Review, 2(11), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/14779960810888329

- Arman, M., & Rehnsfeldt, A. (2003). The hidden suffering among breast cancer patients: A qualitative metasynthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 13(4), 510–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302250721

- Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1997). A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.417

- Barbarin, O. A., Hughes, D., & Chesler, M. A. (1985). Stress, coping, and marital functioning among partners of children with cancer. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47(2), 473–480. https://doi.org/10.2307/352146

- Bar-On, R. (2000). Emotional and social intelligence: Insights from the emotional quotient inventory. In R. Bar-On, & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), The handbook of emotional intelligence (pp. 363–388). Jossey-Bass.

- Bentzen, M., Lemyre, P., & Kenttä, G. (2016a). Changes in motivation and burnout indices in high-performance coaches over the course of a competitive season. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1053160

- Bentzen, M., Lemyre, P., & Kenttä, G. (2016b). Development of exhaustion for high-performance coaches in association with workload and motivation: A person-centered approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.06.004

- Berjot, S., & Gillet, N. (2011). Stress and coping with discrimination and stigmatization. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(33), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00033

- Bishop, F. L., & Holmes, M. M. (2013). Mixed methods in CAM research: A systematic review of studies published in 2012. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/187365

- Bodenmann, G. (1995). A systematic-transactional conceptualization of stress and coping in couples. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 54, 34–49.

- Bodenmann, G. (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping, decade of behavior (pp. 33–49). American Psychological Association.

- Brasher, K. S., Dew, A. B. C., Kilminster, S. G., & Bridger, R. S. (2010). Occupational stress in submariners: The impact of isolated and confined work on psychological well-being. Ergonomics, 53(3), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130903067763

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith, & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 191–205). Routledge.

- Britt, T. W., Castro, C. A., & Adler, A. B. (2005). Self-engagement, stressors, and health: A longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(11), 1475–1486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205276525

- Carson, D., Gilmore, A., Perry, C., & Gronhaug, K. (2001). Qualitative marketing research. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209625

- Carson, F., McCormack, C., & Walsh, J. (2018). Women in sport coaching: Challenges, stress and wellbeing. Journal of Physical Education, Sport, Health and Recreation, 7(2), 63–67. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781849209625

- *Chroni, S. A., Diakaki, E., Oerkos, S., Hassandra, M., & Schoen, C. (2013). What stresses coaches in competition and training? An exploratory inquiry. International Journal of Coaching Science, 7, 25–39.

- Churchill, S. A., Ocloo, J. E., & Siawor-Robertson, D. (2017). Ethnic diversity and health outcomes. Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement, 134(3), 1077–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1454-7

- Cook, G. M., Fletcher, D., & Peyrebryne, M. (2021). Olympic coaching excellence: A quantitative study of psychological aspects of Olympic swimming coaches. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 53, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101876

- *Didymus, F. F. (2017). Olympic and international level sports coaches’ experiences of stressors, appraisals, and coping. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 9(2), 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1261364

- Didymus, F. F., & Fletcher, D. (2012). Getting to the heart of the matter: A diary study of swimmers’ appraisals of organisational stressors. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(13), 1375–1395. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.709263

- Didymus, F. F., & Fletcher, D. (2017a). Organizational stress in high-level field hockey: Examining transactional pathways between stressors, appraisals, coping, and performance satisfaction. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 12(2), 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117694737

- Didymus, F. F., & Fletcher, D. (2017b). Effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention on field hockey players’ appraisals of organizational stressors. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 30, 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.03.005

- Didymus, F. F., & Jones, M. (in press). Cognitive appraisals. In R. S. Arnold, & D. Fletcher (Eds.), Stress, well-being, and performance in sport. Routledge.

- Didymus, F. F., Norman, L., Hurst, M., & Clarke, N. (in press). Work-related stressors, health, and psychological wellbeing among women sports coaches. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching.

- Diener, E. (2009). Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed diener. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4

- Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

- Doll, A., Hölzel, B. K., Bratec, S. M., Boucard, C. C., Xie, X., Whlschläger, A. M., & Sorg, C. (2016). Mindful attention to breath regulates emotions via increased amygdala-prefrontal cortex connectivity. NeuroImage, 134, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.03.041

- Duckworth, A. L., Steen, T. A., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 629–651. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154

- *Durand-Bush, N., Collins, J., & McNeill, K. (2012). Women coaches’ experiences of stress and self-regulation: A multiple case study. International Journal of Coaching Science, 6(2), 21–43.

- Edwards, D. J., & Styen, B. J. M. (2008). Sport psychological skills training and psychological well-being. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 30(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajrs.v30i1.25978

- Fletcher, D., & Scott, M. (2010). Psychological stress in sports coaches: A review of concepts, research, and practice. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410903406208

- Fletcher, D., Hanton, S., & Mellalieu, S. (2006). An organisational stress review: Conceptual and theoretical issues in competitive sport. In S. Hanton and S. D. Mellalieu (Ed.) Literature Reviews in Sport Psychology (pp 1–53) Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Folkman, S. (2008). The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 21(3), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701740457

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevention and Treatment, 3(1), article 0001a. https://doi.org/10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.31a

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00431

- *Frey, M. (2007). College coaches’ experiences with stress – “problem solvers” have problems, too. The Sport Psychologist, 21(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.1.38

- Garside, R. (2014). Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 27(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2013.777270

- Gasper, D. (2010). Understanding the diversity of conceptions of well-being and quality of life. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2009.11.006

- Gillet, N., Berjot, S., & Gobance, L. (2009). A motivational model of performance in the sport domain. European Journal of Sport Science, 9(3), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461390902736793

- Glidden, L. M., Billings, F. J., & Jobe, B. M. (2006). Personality coping style and well-being of parents rearing children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 949–962. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00929.x

- Grant, L., & Kinman, G. (2012). Enhancing wellbeing in social work students: Building resilience in the next generation. Social Work Education, 31(5), 605–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2011.590931

- Greenglass, E. R., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being. European Psychologist, 14(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.29

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379625

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Guillaume, C., & Pochic, S. (2009). What would you sacrifice? Access to top management and work-life balance. Gender, Work and Organization, 16(1), 14–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00354.x

- Harnois, G., & Gabriel, P. (2000). Mental health and work: Impact, issues and good practices. World Health Organisation. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42346

- Hellgren, J., Sverke, M., & Iskasson, K. (1999). A two-dimensional approach to job insecurity: Consequences for employee attitudes and well-being. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398311

- Hodgson, L., Butt, J., & Maynard, I. (2017). Exploring the psychological attributes underpinning elite sports coaching. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(4), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117718017

- Howard, F. (2008). Managing stress or enhancing wellbeing? Positive psychology’s contributions to clinical supervision. Australian Psychologist, 43(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060801978647

- Jensen, L. A., & Allen, M. N. (1996). Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qualitative Health Research, 6(4), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239600600407

- Jorgensen, L. I., Nel, J. A., & Rouz, D. J. (2013). Qualitative of work-related well-being in selected South African occupations. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 23(3), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2013.10820650

- Kaiseler, M., Levy, A., Nicholls, A., & Madigan, D. (2017a). The independent and interactive effects of the big five personality dimensions upon dispositional coping and coping effectivenhess in sport. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4, 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1362459

- Kaiseler, M., Poolton, J. M., Backhouse, S. H., & Stanger, N. (2017b). The relationship between mindfulness and life stress in student-athletes: The mediating role of coping effectiveness and decision rumination. Sport Psychologist, 31(3), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2016-0083

- Karpaviciute, S., & Parkinson, C. (2015). Arts activity and well-being in the workplace: A pilot study of health service workers in Lithuania. Neurologijos Seminarai, 19(3), 210–216. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12512/93512

- Keegan, R. J., Spray, C. M., Harwood, C. G., & Lavallee, D. E. (2014). A qualitative synthesis of research into social motivational influences across the athletic career span. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health, 6(4), 539–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.857710

- Kelley, B. C., Eklund, R. C., & Ritter-Taylor, M. (1999). Stress and burnout among collegiate tennis coaches. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 21(2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.21.2.113

- Kenttä, G., Bentzen, M., Dieffenback, K., & Olusoga, P. (2020). Challenges experienced by women high-performance coaches: Sustainability in the profession. International Sport Coaching Journal, 7(2), 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2019-0029

- *Knights, S., & Ruddock-Hudson, M. (2016). Experiences of occupational stress and social support in Australian Football League senior coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(2), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954116636711

- Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8(269), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt2017.00269

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Springer.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1(3), 141–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410010304

- *Levy, A., Nicholls, A., Marchant, D., & Polman, R. (2009). Organisational stressors, coping, and coping effectiveness: A longitudinal study with an elite coach. International Journal of Sorts Science & Coaching, 4(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.4.1.31

- Linley, P. A., Joseph, S., Harrington, S., & Wood, A. M. (2006). Positive psychology: Past, present, and (possible) future. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500372796

- Lundkvist, E., Gustafsson, H., Hjälm, S., & Hassmén, P. (2012). An interpretative phenomological analysis of burnout and recovery in elite soccer coaches. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 4(3), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2012.693526

- Lyonette, C., Crompton, R., & Wall, K. (2007). Gender, occupational class and work-life conflict. Community, Work and Family, 10(3), 283–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701456245

- Malik, S., & Noreen, S. (2015). Perceived organizational support as a moderator of affective well-being and occupational stress among teachers. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 9(3), 865–874.

- Marcatto, F., Colautti, L., Filon, F. L., Luis, O., Blas, L. D., Cavallero, C., & Ferrante, D. (2016). Work-related stress risk factors and health outcomes in public sector employees. Safety Science, 89, 274–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.07.003

- McCarthy, P. J., Allen, M. S., & Jones, M. V. (2013). Emotions, cognitive interference, and concentration disruption in youth sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(5), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.738303

- McGannon, K. R., Smith, B., Kendellen, K., & Gonsalves, C. A. (2019). Qualitative research in six sport and exercise psychology journals between 2010 and 2017: An updated and expanded review of trends and interpretations. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1655779

- Meyer, D. Z., & Avery, L. M. (2009). Excel as a qualitative data analysis tool. Field Methods, 21(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X08323985

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. W., & PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4086

- Nomaguchi, K. M., Milkie, M., & Bianchi, S. (2005). Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 756–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05277524

- Norman, L., & Rankin-Wright, A. (2016). Surviving rather than thriving: Understanding the experiences of women coaches using a theory of gendered social well-being. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216660283

- Norris, L. A., Didymus, F. F., & Kaiseler, M. (2017). Stressors, coping, and well-being among sports coaches: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 33, 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.08.005

- Norris, L. A., Didymus, F. F., & Kaiseler, M. (2020). Understanding social networks and social support resources with sports coaches. Psychology of Sport & Exercise. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101665.

- North, J. (2009). The UK coaching workforce. Sports Coach UK.

- O’Connell, R., & Downe, S. (2009). A metasynthesis of midwives’ experience of hospital practice in publicly funded settings: Compliance, resistance and authenticity. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 13(6), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459308341439

- O’Connor, D., & Bennie, A. (2006). The retention of youth sport coaches. Change: Transformations in Education, 9(1), 27–38.

- *Olusoga, P., Butt, J., Hays, K., & Maynard, I. (2009). Stress in elite sports coaching: Identifying stressors. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21(4), 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200903222921

- *Olusoga, P., Butt, J., Maynard, I., & Hays, K. (2010). Stress and coping: A study of world class coaches. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(3), 274–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413201003760968

- *Olusoga, P., Maynard, I., Hays, K., & Butt, J. (2012). Coaching under pressure: A study of Olympic coaches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(3), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.639384

- Park, C. L., & Alder, N. E. (2003). Coping style as a predictor of health and well-being across the first year of medical school. Health Psychology, 22(6), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.627

- Paterson, B., Thorne, S., Canam, C., & Jillings, C. (2001). Meta-study of qualitative health research: A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Sage.

- *Potts, A. J., Didymus, F. F., & Kaiseler, M. (2019). Exploring stressors and coping among volunteer, part-time and full-time sports coaches. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1457562

- Robertson, I., & Cooper, G. (2011). Well-being: Productivity and Happiness at work. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rothmann, S., Jorgensen, L. I., & Hill, C. (2011). Coping and work engagement in selected South African organizations. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i1.962

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

- Sakar, M., & Hilton, N. K. (2020). Psychological resilience in Olympic medal-winning coaches: A longitudinal qualitative study. International Sport Coaching Journal, 7(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2019-0075

- Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & van Rhenen, W. (2007). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind of three different kinds of employee well-being? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(2), 173–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00285.x

- Schlosser, R. W., Wendt, O., Bhavani, S., & Nail-Chiwetalu, B. (2006). Use of information-seeking strategies for developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence-based practice: The application of traditional and comprehensive pearl growing. A review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 41(5), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820600742190

- Sebbens, J., Hassmén, P., Crisp, D., & Wensley, K. (2016). Mental health in sport (MHS): improving the early intervention knowledge and confidence of elite sport staff. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(911), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00911

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Sias, P. M. (2009). Organizing relationships: Traditional and emerging perspectives on workplace relationships. Sage.

- Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Smith, J. K., & Heshusius, L. (1986). Closing down the conversation: The end of the quantitative – qualitative debate among educational inquiries. Educational Researcher, 15(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015001004

- Sparks, K., Faragher, B., & Cooper, G. L. (2001). Well-being and occupational health in the 21st century workplace. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 74(4), 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317901167497

- Stebbings, J., Taylor, I. M., & Spray, C. M. (2015). The relationship between psychological well- and ill-being, and perceived autonomy supportive and controlling interpersonal styles: A longitudinal study of sport coaches. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 19, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.02.002

- Stebbings, J., Taylor, I. M., & Spray, C. M. (2011). Antecedents of perceived coach autonomy supportive and controlling behaviours: Coach psychological need satisfaction and well-being. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(2011), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.2.255