ABSTRACT

The purpose of the current article is to define critical appraisal, identify its benefits, discuss conceptual issues influencing the adequacy of a critical appraisal, and detail procedures to help reviewers undertake critical appraisals. A critical appraisal involves a careful and systematic assessment of a study’s trustworthiness or methodological rigour, and contributes to assessing how confident people can be in the findings of a set of studies. To help reviewers include high quality critical appraisals in their articles, they can consider differences between quality and bias, the value of total quality scores, the advantages and disadvantages of standardized checklists, the relevance of the experimental hierarchy of evidence, the differences between critical appraisal tools and reporting standards, and the challenges involved in appraising qualitative research. The steps involved in a sound critical appraisal include: (a) identifying the study type(s) of the individual paper(s), (b) identifying appropriate criteria and checklist(s), (c) selecting an appropriate set of criteria and checklist, (d) performing the appraisal, and (e) summarizing and using the results. Although these steps apply to critical appraisals of both quantitative and qualitative research, they require reviewers to make and defend a number of decisions resulting from the subjective features involved in assessing research.

Critical appraisal

‘The notion of systematic review – looking at the totality of evidence – is quietly one of the most important innovations in medicine over the past 30 years’ (Goldacre, Citation2011, p. xi). These sentiments apply equally to sport and exercise psychology; systematic review or evidence synthesis provides transparent and methodical procedures that assist reviewers in analysing and integrating research, offering professionals evidence-based insights into a body of knowledge (Tod, Citation2019). Systematic reviews help professionals stay abreast of scientific knowledge, a useful benefit given the exponential growth in research since World War II and especially since 1980 (Bornmann & Mutz, Citation2015). Sport psychology research has also experienced tremendous growth. In 1970, the first journal in the field, the International Journal of Sport Psychology, published 11 articles. In 2020, 12 journals with ‘sport psychology’ or ‘sport and exercise psychology’ in their titles collectively published 489 articles, a 44-fold increase.Footnote1 Beyond these journals, sport and exercise psychology research appears in student theses, books, other sport- and non-sport related journals, and the grey literature. The growth of research and the diverse locations in which it is hidden increases the challenge reviewers face to stay abreast of knowledge for practice.

Once reviewers have sourced the evidence, they need to synthesize and interpret the research they have located. When synthesizing evidence, reviewers have to assemble the research in transparent and methodical ways to provide readers with a novel, challenging, or up-to-date picture of the knowledgebase. Other authors within this special issue present various ways that reviewers can synthesize different types of evidence. When interpreting the findings from a synthesis of the evidence, reviewers need to consider the credibility of the underlying research, a process typically labelled as a critical appraisal. A critical appraisal is not only relevant for systematic reviewers. All people who use research findings (e.g. practitioners, educators, coaches, athletes) benefit from adopting a critical stance when appraising the evidence, although the level of scrutiny may vary according to the person’s purpose for accessing the work. During a systematic review, a critical appraisal of a study focuses on its methodological rigour: How well did the study’s method answer its research question (e.g. did an experiment using goal setting show how well the intervention enhanced performance?). A related topic is a suitability assessment, or the evaluation of how well the study contributes to answering a systematic review question (e.g. how much does the goal setting experiment add to a review on the topic?).

A systematic review involves an attempt to answer a specific question by assembling and assessing the evidence fitting pre-determined inclusion criteria (Booth et al., Citation2016; Lasserson et al., Citation2021; Tod, Citation2019). Key features include: (a) clearly stated objectives or review questions; (b) pre-defined inclusion criteria; (c) a transparent method; (d) a systematic search for studies meeting the inclusion criteria; (e) a critical appraisal of the studies located; (f) a synthesis of the findings from the studies; and (g) an interpretation or evaluation of the results emerging from the synthesis. People do not use the term systematic review consistently. For example, some people restrict the term to those reviews that include a meta-analysis, whereas other individuals believe systematic reviews do not need to include statistics and can use narrative methods (Tod, Citation2019). For this article, any review that meets the above criteria can be classed as a systematic review.

A critical appraisal is a key feature of a systematic review that allows reviewers to assess the credibility of the underlying research on which scientific knowledge is based. The absence of a critical appraisal hinders the reader’s ability to interpret research findings in light of the strengths and weaknesses of the methods investigators used to obtain their data. Reviewers in sport and exercise psychology who are aware of what critical appraisal is, its role in systematic reviewing, how to undertake one, and how to use the results from an appraisal to interpret the findings of their reviews assist readers in making sense of the knowledge. The purpose of this article is to (a) define critical appraisal, (b) identify its benefits, (c) discuss conceptual issues that influence the adequacy of a critical appraisal, and (d) detail procedures to help reviewers undertake critical appraisals within their projects.

What is critical appraisal?

Critical appraisal involves a careful and systematic assessment of a study’s trustworthiness or rigour (Booth et al., Citation2016). A well-conducted critical appraisal: (a) is an explicit systematic, rather than an implicit haphazard, process; (b) involves judging a study on its methodological, ethical, and theoretical quality, and (c) is enhanced by a reviewer’s practical wisdom, gained through having undertaken and read research (Flyvbjerg et al., Citation2012). It is important to remember also that no researcher can stand outside their history nor escape their human finitude. That means inevitably a researcher’s theoretical, personal, gendered and so on history will influence critical appraisal.

When undertaking a formal critical appraisal, reviewers typically discuss methodological rigour in the Results and Discussion sections of their publications. They often use checklists to assess individual studies in a consistent, explicit, and methodical way. Checklists tailored for quantitative surveys, for example, may assess the justification of sample size, data analysis techniques, and the questionnaires (Protogerou & Hagger, Citation2020). Numerous checklists exist for both qualitative and quantitative research (Crowe & Sheppard, Citation2011; Katrak et al., Citation2004; Quigley et al., Citation2019; Wendt & Miller, Citation2012). For example, the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 procedures are tailored towards assessing the methodological rigour of randomized controlled trials (Sterne et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). Most checklists, however, lack evidence to support their use (Crowe & Sheppard, Citation2011; Katrak et al., Citation2004; Quigley et al., Citation2019; Wendt & Miller, Citation2012).

A suitability assessment for a systematic review of quantitative research considers design suitability and study relevance (Liabo et al., Citation2017). Design suitability deals with how a study’s method matches the review question. Investigators often address design suitability implicitly when creating inclusion and exclusion criteria for their reviews. For example, reviewers assessing the efficacy of an intervention usually focus on experimental studies, whether randomized, nonrandomized, controlled, or uncontrolled. Study relevance considers how well the final set of studies (the study contexts) aligns with the target context to which their findings will be applied (Liabo et al., Citation2017). For example, if reviewers seek to underpin practice guidelines for using psychological interventions with athletes, then they will consider the participants (e.g. level of athlete) and study contexts of included investigations (e.g. were dependent variables measured during or away from competitive settings?). Knowing whether or not most studies focused on competitive athletes, and assessed dependent variables in competitive environments helps reviewers when framing the boundaries of their recommendations. Similar to design suitability, reviewers may address study relevance when planning their inclusion and exclusion criteria, such as stating that the investigations must have targeted competitive athletes. Where reviewers synthesize research with diverse participants and settings, then they need to address study relevance when interpreting their results.

Why undertake critical appraisal?

According to Carl Sagan (Citation1996, p. 22), ‘the method of science, as stodgy and grumpy as it may seem, is far more important than the findings of science.’ The extent to which readers can have confidence in research findings is influenced by the methods that generated, collected, and manipulated the data, along with how the investigators employed and reflected on them (especially in qualitative research). For example, have investigators reflected on how their beliefs and assumptions influenced the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data? Further, evaluating the methodological rigour of research (along with design suitability and study relevance) helps ensure practitioners engage in evidence-based practice (Amonette et al., Citation2016; Tod & Van Raalte, Citation2020). Research informs sport and exercise psychology practitioners when deciding how to assist clients in effective, safe, ethical, and humane ways. Nevertheless, research varies in quality, type, and applicability. Critical appraisal allows sport and exercise psychology practitioners to decide how confident they can be in research to guide decision making. Without a critical attitude and commitment to relying on the evidence available, practitioners may provide ineffective interventions that do not help clients, and may even harm recipients (Chalmers & Altman, Citation1995). For example, although practitioners use mindfulness interventions to enhance athletes’ competitive performances, limited evidence shows the technique is effective for that purpose and researchers have not explored possible iatrogenic effects (Noetel et al., Citation2019).

The influence limitations exert on a study’s findings range from trivial to substantive (Higgins et al., Citation2017). Critical appraisal is neither designed to identify the perfect study nor to offer an excuse for reviewers to be overly critical and believe that no study is good enough, so-called critical appraisal nihilism (Sackett et al., Citation1997). Instead, critical appraisal helps reviewers assess the strength and weaknesses of research, decide how much confidence readers can have in the findings, and suggest ways to improve future research (Booth et al., Citation2016). Results from a critical appraisal may inform a sensitivity analysis, whereby reviewers evaluate how a review’s findings change when they include or exclude studies of particular designs or methodological limitations (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2006). Being overly critical, or unduly accepting, may lead to inaccurate or inappropriate interpretations of primary research. Consequences may include poor practice recommendations and an increased risk of harm to people involved in sport, exercise, and physical activity.

Further, critical appraisal helps to ensure transparency in the assessment of primary research, although reviewers need to be aware of the strengths and limitations. For example, in quantitative research a critical appraisal checklist assists a reviewer in assessing each study according to the same (pre-determined) criteria; that is, checklists help standardize the process, if not the outcome (they are navigational tools, not anchors, Booth, Citation2007). Also, if the checklist has been through a rigorous development process, the reviewer is assessing each study against criteria that have emerged from a consensus among a community of researchers. In quantitative research, investigators hope that critical appraisal checklists reduce a reviewer’s personal bias; however, decision-makers, including researchers, may be neither reliable nor self-aware; and they may fall prey to numerous cognitive biases including (Kahneman, Citation2012; Nuzzo, Citation2015):

Collecting evidence to support a favoured conclusion and ignoring alternative explanations, rather than searching for information to counter their hypotheses

Treating random patterns in data as meaningful trends

Testing unexpected results but not anticipated findings

Suggesting hypotheses after analysing results to rationalize what has been found

These cognitive biases can be counteracted by (a) testing rival hypotheses, (b) registering data extraction and analysis plans publicly, within review protocols, before undertaking reviews, (c) collaborating with individuals with opposing beliefs (Booth et al., Citation2013), (d) having multiple people undertake various steps independently of each other and comparing results, and (e) asking stakeholders and disinterested individuals to offer feedback on the final report before making it publically available (Tod, Citation2019).

Conceptual issues underpinning critical appraisal

When conducting systematic reviews, researchers make numerous decisions, many of which lack right or wrong answers. Conflicting opinions exist across multiple issues, including several relevant to critical appraisal. To assist reviewers in enhancing the rigour of their work, anticipate potential opposition, and provide transparent justification of their choices, the following topics are discussed: quality versus bias, quantitative scoring during critical appraisal, the place of reporting standards, critical appraisal in qualitative research, the value of a hierarchy of evidence, and self-generated checklists.

Quality versus bias

It is useful to distinguish quality from bias, especially when thinking about quantitative research (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2006). Reflecting a positivist and quantitative orientation, bias often is implied to mean ‘systematic error, or deviation from the truth, in results or inferences’ (Higgins et al., Citation2017, p. 8.3), whereas quality is ‘the extent to which study authors conducted their research to the highest possible standards’ (Higgins et al., Citation2017, p. 8.4). Investigators assess bias by considering a study’s methodological rigour. Quality is a broader and subjective concept, and although it embraces bias, it also includes other criteria target audiences may value (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2006). Research conducted to the highest quality standards may still contain bias. For example, when experimenters examine self-talk on motor performance, it is difficult to blind participants. Most participants realize the purpose of the study once they are asked to utter different types of self-talk from pre- to post-test, and this insight may influence performance. Although bias is present, the experimenters may have employed the best method possible given the topic.

Regarding quality, Pawson et al. (Citation2003) propose criteria that may be helpful for sport and exercise psychology research. The TAPUPAS criteria include:

Transparency: Is the study clear on how the knowledge was produced?

Accuracy: Does the study rely on relevant evidence to generate the knowledge?

Purpose: Did the study employ suitable methods?

Utility: Does the study answer the research questions?

Propriety: Is the study legal and ethical?

Accessibility: Can intended audiences understand the study?

Specificity: Does the study conform to the standards for the type of knowledge generated?

A reviewer might apply these criteria to the self-talk study described above. For example, was ethical clearance obtained prior to data collection? Despite the limitations, does the study answer the research question? Will the intended audience understand the study? Pawson et al.’s (Citation2003) criteria show that quality is influenced by the study’s intrinsic features, context, and target audiences.

To score or not to score, that is the question

Frequently, reviewers undertaking a critical appraisal generate a total quality score they present as a percentage or proportion in their evidence tables, alongside descriptions of other research features (e.g. participants, measures, findings). Many critical appraisal tools direct investigators to calculate an overall score representing study quality. For example, the Downs and Black (Citation1998) checklist contains 27 items across 5 domains: reporting, external validity, internal validity (bias), internal validity (confounding), and statistical power. Total score ranges from 0 to 32. Reviewers score 25 of the items as either 1 (item addressed) or 0 (item not addressed or in an unclear fashion). Item 5 (are the distributions of principal confounders in each group of subjects to be compared clearly described?) is scored 2 for item addressed, 1 for item partially addressed, and 0 if item not addressed. Item 27 on statistical power is scored 0–5 based on sample size. Items 25 and 27 are weighted more heavily, indicating that Downs and Black consider that these factors influence a study’s results more than the other items.

Reliance on quality scores impedes science (Booth et al., Citation2016; Liabo et al., Citation2017). First, the research supporting most checklists is limited or non-existent. Few critical appraisal checklists have been calibrated against meaningful real world criteria (Crowe & Sheppard, Citation2011; Katrak et al., Citation2004; Quigley et al., Citation2019; Wendt & Miller, Citation2012). Second, when reviewers arrive at a total score, they often interpret the study as being weak, moderate, or strong (or low, medium, or high) quality. Decisions on whether a study is considered weak, moderate, or strong are based on arbitrary cut-off scores. For example, total scores for two studies might differ by a single point, yet one study is labelled weak and the other moderate. Both studies can become weak or moderate by moving the cut-off score threshold by a single point.

Third, two studies can achieve the same total score, but their profile of scores across the items may differ. A total score does not explain the pattern of strengths and weaknesses across a group of studies. Readers need to explore the ratings at the individual item level to gain useful insight. Knowing which items a study did, or did not satisfy helps readers decide how much credence to place in that study’s findings. Further, readers are not interested, primarily, in the critical appraisal of individual studies: they want to know about trends across a body of evidence. Which criteria have the majority of studies upheld and which others are mostly not satisfied? Trends across a body of evidence point to how studies can be improved and help reviewers set a research agenda.

Fourth, the relative importance of individual items is another issue with scoring. In the absence of research quantifying the influence of limitations on a study’s outcomes, decisions about how to weight items on checklists are arbitrary. For example, is a poorly constructed questionnaire’s influence on a study’s outcomes the same as, greater than, or less than that of an inadequate or unrepresentative sample? Generally, people creating checklists cannot draw on evidence to justify scoring systems. The lack of clarity regarding relative importance also limits the reader’s ability to interpret the results of a systematic review in light of the critical appraisal. Readers can make broad interpretations, such as concluding that the lack of blinding may have influenced participants’ performance on a trial. It would be helpful, however, to assess how much of a difference not blinding makes to performance so that readers can decide if the results still have value for their context.

Rather than providing an aggregate quality score for each study, reviewers can present separate detail within a table on how each study performed against each item on the checklist (see Noetel et al., Citation2019, for an example). Such tables allow readers to evaluate a study for themselves, transferring the burden from the reviewer. These tables eliminate the need for arbitrary cut-off scores, and deliver fine-grained information to help readers identify methodological attributes that may influence the depth and boundaries of topic knowledge. These tables also allow readers to determine the criteria most important to them (e.g. a practitioner might not care if the participants were blinded or not when testing self-talk interventions).

Reporting standards versus critical appraisal checklists

Whereas critical appraisal tools help reviewers explore a study’s methodological rigour, reporting guidelines allow them to examine the clarity, coherence, and comprehensiveness of the write-up (Buccheri & Sharifi, Citation2017). Poor reporting prevents reviewers from evaluating a study fairly and perhaps even including the study in a systematic review (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015; Chambers, Citation2019). For example, reviewers hoping to perform a meta-analysis have to discard studies or estimate effect sizes when original authors do not report basic descriptive statistical information, leading to imprecise or biased results (Borenstein et al., Citation2009). Reasons for incomplete reports include journal space restrictions, inconsistencies in the review process, the lack of accepted reporting guidelines, and authors’ attempts to mask methodological limitations (Chambers, Citation2019; Johansen & Thomsen, Citation2016; Pussegoda et al., Citation2017).

Some organizations have sought to improve the completeness and clarity of scientific publications by producing reporting standards, such as the EQUATOR Network (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research, https://www.equator-network.org/). Reporting standards come with advantages and disadvantages. These guidelines, for instance, help researchers produce reports that conform to the standards of a scientific community, although their influence has been minimal to date (Johansen & Thomsen, Citation2016). Reporting standards, however, reflect their creator’s beliefs, whose views may differ from those of other people, particularly among qualitative researchers operating from different traditions.

Poor reporting does not necessarily reveal why a study has omitted detail required for critical appraisal; absence of information could reflect limitations with the method, a strong study insufficiently presented, or that methods are novel and the selected community does not know how to judge it (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015). Reviewers can judge whether a well-documented study is of high or low quality; they cannot, however, evaluate an inadequately described investigation positively. Dissemination is a necessary step for research findings to enter the knowledgebase, so good reporting is an attribute of a high quality study (Gastel & Day, Citation2016).

Given the need for good reporting, reviewers justifiably exclude poorly-reported studies from their projects (Carroll et al., Citation2012). In practice, this is more common for quantitative studies, where a study’s results are completely uncertain, than for a qualitative study where uncertainty is likely to be a question of degree; the so-called ‘nugget’ argument that ‘bad’ research can yield ‘good’ evidence (Pawson, Citation2006). The onus for clarity is on authors; readers or reviewers should not bear the burden of interpreting incomplete reports. Reviewers who intend to give authors the benefit of the doubt will assess adherence to reporting standards prior to or alongside undertaking a critical appraisal (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015). Reviewers can use the additional data on reporting quality in a sensitivity analysis to explore the extent to which their confidence in review findings might be influenced by poor quality or poorly reported studies.

Critically appraising qualitative research

The increasing recognition that qualitative research contributes to knowledge, informs practice, and guides policy development has been acknowledged in the creation of procedures for synthesizing qualitative research (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). Use of qualitative research also requires skills and experience in how to appraise these inquiries. Qualitative research varies in its credibility and methodological rigour, as with quantitative investigations. Historically, reviewers have disagreed on whether or not they can critically appraise qualitative research meaningfully (Gunnell et al., Citation2020; Tod, Citation2019). Recent years have seen an emerging consensus that qualitative research can, and does need to be appraised, with a realigned focus on determining how to undertake critical evaluation (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015). That is, qualitative research needs to be held to high and difficult standards.

More than 100 critical appraisal tools currently exist for qualitative research. Tools fall into two categories: checklists and holistic frameworks encouraging reflection (Majid & Vanstone, Citation2018; Santiago-Delefosse et al., Citation2016; Williams et al., Citation2020). Both checklists and holistic frameworks are subject to criticisms. Checklists, for example, normally equate methodological rigour with data collection and analysis techniques. They privilege readily apparent technical procedures (e.g. member reflections), over less observable attributes that exert greater influence on a study’s contribution (e.g. researcher engagement and insight; Morse, Citation2021; Williams et al., Citation2020). Although frameworks include holistic criteria, such as reflexivity, transferability, and transparency, they rely on each reviewer’s understanding and ability to apply the concepts to specific qualitative studies (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2020). Further, both checklists and frameworks tend to apply a generic set of criteria that fail to distinguish between different types of qualitative research (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015; Majid & Vanstone, Citation2018). Criteria can also change over time when critiques of techniques and quality standards, like member checking, data saturation, and inter-rater reliability, take place. Checklists or guidelines become outdated over time. They are also limited to appraising certain types of qualitative research and fail to account for new or different ways of doing qualitative research, such as creative non-fictions and post-qualitative research (Monforte & Smith, Citation2021). Also troubling is when a criterion embedded in a checklist or guideline is used during the critical appraisal process, yet that quality standard is problematic, such as member checking whose underpinning assumptions may be contrary to the researcher’s epistemological and ontological position (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018), and for which there is no evidence that it enhances a study’s findings or credibility (Thomas, Citation2017). Papers could be deemed ‘high quality’ but rest on criteria that are problematic! Furthermore, when investigators use preordained and fixed quality appraisal checklists, research risks becoming stagnant, insipid, and reduced to a technical exercise. There is also the risk that researchers will use well-known checklists as part of a strategic ploy to enhance the chances their studies will be accepted for publication. Just as with quantitative research synthesis, investigators need to use suitable critical appraisal criteria and tools tailored and appropriately applied to the types of evidence being examined (Tod, Citation2019).

The limitations with the hierarchy of evidence

When planning a critical appraisal, reviewers may ask about suitable criteria or the design features to assess. Available critical appraisal tools frequently contain different items indicating that suitable criteria typically rest on authors’ opinions rather than evidence (Crowe & Sheppard, Citation2011). Variation among critical appraisal tools typically reflects the different research designs at which they are targeted (e.g. experiments versus descriptive surveys). The variance also reflects the lack of agreement among different research groups about the gold standard critical appraisal criteria. Each tool reflects the idiosyncratic values of its creators. Reviewers should decide upon an appropriate tool and then justify its selection (Buccheri & Sharifi, Citation2017).

When selecting critical appraisal criteria and tools, reviewers are influenced by their beliefs about the relative merits of different research designs (Walach & Loef, Citation2015). For example, researchers in health-related fields frequently rate research design according to the methodological hierarchy of evidence (Walach & Loef, Citation2015). This hierarchy ranks evidence according to how it is generated, with expert opinion being the least credible type and meta-analytic reviews of randomized controlled trials being the highest form of evidence. Reliance on the hierarchy privileges numerical experimental research over other world views (Andersen, Citation2005). The hierarchy is useful for evaluating intervention efficacy or testing hypothesized causal relationships. It is less useful in other contexts, such as when doing co-produced research or undertaking qualitative investigations to explore how people interpret and make sense of their lives. Slavish devotion to the hierarchy implies that certain types of research (e.g. qualitative) are inferior to other forms (e.g. randomized controlled trials). Meaningful critical appraisal requires that reviewers set aside a bias towards the experimental hierarchy of evidence and acknowledge different frameworks. It calls on researchers to become connoisseurs of research (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2009). Being a connoisseur does not mean one must like a certain method, methodology, approach, or paradigm; it means to judge studies appropriately and on the terms and logic that underpin them.

Self-generated checklists

There are many instances whereby researchers have developed their own checklists or have modified existing tools. Developing or adapting checklists, however, requires similar rigour to other research instruments; requirements typically include a literature review, a nominal group or ‘consensus’ process, and a mechanism for item selection (Whiting et al., Citation2017). Consensus, however, is subjective, relational, contextual, limited to those people invited to participate, and influenced by researchers’ history and power dynamics (Booth et al., Citation2013). Systematic reviewers should not consider agreement about critical appraisal criteria as ‘unbiased’ or as a route to a single objective truth (Booth et al., Citation2013).

The recent movement from a reliance on a universal ‘one-size-fits-all’ set of qualitative research criteria to a more flexible list-like approach in which reviewers use critical appraisal criteria suited to the type of qualitative research being judged is also evident in shifts within sport and exercise psychology in terms of how criteria for appraising work is conceptualised (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018; Sparkes, Citation1998; Sparkes & Smith, Citation2009; Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). Reviewers in sport and exercise psychology can draw on the increasing qualitative literature that provides criteria suitable to judge certain studies, but not others. Rather than using criteria in a pre-determined, rigid, and universal manner as many checklists propose or invite, researchers need to continually engage with an open-ended list of criteria to help them judge the studies they are reviewing in suitable ways. In other words, instead of checking criteria off a checklist and then aggregating the number of ticks/yes’s to determine quality, ongoing lists of criteria that can be added to, subtracted from and modified depending on the study can be used to critically appraise qualitative research.

Undertaking critical appraisal in sport and exercise psychology reviews

Critical appraisal is performed in a series of steps so that reviewers complete the task in a systematic and consistent fashion (Goldstein et al., Citation2017; Tod, Citation2019). Steps include:

Identifying the study type(s) of the individual paper(s)

Identifying appropriate criteria and checklist(s)

Selecting an appropriate checklist

Performing the appraisal

Summarizing, reporting, and using the results

To assist with step 1, the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM, Citation2021) and the UK National Institute for Clinical Evidence (NICE, Citation2021) provide guidance, decision trees, and algorithms to help reviewers determine the types of research being assessed (e.g. experiment, cross-sectional survey, case–control). Clarity on the types of research under scrutiny helps reviewers match suitable critical appraisal criteria and tools to the investigations they are assessing. Steps 2 and 3 warrant separation because different types of primary research are often included in a review, and investigators may need to use multiple critical appraisal criteria and tools. As part of step 5, reviewers enhance transparency by reporting how they undertook the critical appraisal, the methods, or checklists they used, and the citation details of the resources involved. Providing the citation details allows readers to assess the critical appraisal tools as part of their assessment of the systematic review. These suggestions to be transparent about the critical appraisal are included in systematic review reporting standards (e.g. PRISMA 2020, http://prisma-statement.org/). The following discussion considers how these 5 steps might apply for quantitative and qualitative research, prior to briefly mentioning two issues related to a critical appraisal: the value of exploring the aggregated review findings from a project and undertaking an appraisal of the complete review.

Critically appraising quantitative studies for inclusion in a quantitative review

This section illustrates how the five steps above can help reviewers critically appraise quantitative studies and present the results in a review, by overviewing the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias-2 (ROB2) method designed for assessing randomized controlled trials of interventions (Sterne et al., Citation2019, Citation2020).

1. Identifying the Study Type(s) of the Individual Paper(s)

Normally, researchers would need to identify the types of studies being reviewed before proceeding to step 2. It makes no sense for reviewers to select a critical appraisal tool before they know what types of evidence they are assessing. In the current example, however, we assume the studies being assessed are randomized controlled trials because we are using the Risk of Bias 2 tool to illustrate the critical appraisal process.

2. Identifying appropriate checklist(s)

ROB2 is not the only checklist available to appraise experiments, with other examples including the Jadad score (Jadad et al., Citation1996) and the PEDro scale (Maher et al., Citation2003). The tools vary in their content and psychometric evidence. Reviewers who are aware of the different tools available can make informed decisions about which ones to consider. Reviewers enhance the credibility of their critical appraisals by matching a suitable tool to the context, audience, and the research they are assessing. In the current example, ROB2 is a suitable tool because it has undergone rigorous development procedures (Sterne et al., Citation2019).

3. Selecting an Appropriate Checklist

ROB2 helps reviewers appraise randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of interventions on measured health-related or behavioural outcomes. For example, McGettigan et al. (Citation2020) used the risk of bias tool when reviewing the influence of physical activity interventions on mental health in people experiencing colorectal cancer. Reviewers appraising other types of experiments (e.g. non-randomized controlled trials, uncontrolled trials, single-subject designs, or within participant experimental designs) would use different methods and criteria, but the overall process is similar.

ROB2 determines the risk that systematic factors have biased the outcome of a trial, producing either an overestimate or underestimate of the effect. The ROB2 method is applied to each outcome; systematic reviews including more than one outcome should contain multiple ROB2 assessments (Higgins et al., Citation2020). For example, two ROB2 assessments are needed where reviewers explore the effect of instructional self-talk on both maximal muscular force production and local muscular endurance. Free resources and webinars on ROB2 exist at the Cochrane Collaboration website (https://methods.cochrane.org/risk-bias-2).

4. Performing the Appraisal

Initially, investigators assess the risk of bias for each study that satisfied the inclusion criteria for the review across five domains. The domains include (a) the randomization process, (b) deviations from intended interventions, (c) missing outcome data, (d) outcome measurement error, and (e) selective reporting of the results. The resources at the ROB2 website contain guiding questions and algorithms to help reviewers assess risk of bias and assign one of the following options to each domain: low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or some concerns. Reviewers also decide on an overall risk of bias for each study that typically reflects the highest level of risk emerging across the five domains. For example, if a study has at least one high risk domain, then the overall risk is high, even where there is low risk for the remaining domains. The overall risk is also set at high if at least two domains attract the judgment of ‘some concerns’. The Cochrane Collaboration recommends that risk of bias assessments are performed independently by at least two individuals who compare results and reconcile differences. Ideally, reviewers should determine the procedures they will use for reconciling differences prior to undertaking the risk of bias and document these in a registered protocol.

5. Summarising, Reporting, and Using the Results

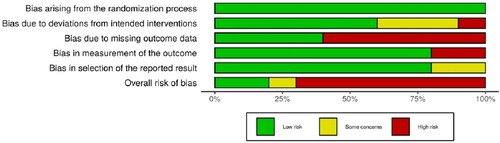

The results of a ROB2 appraisal are typically included in various tables and figures within a review manuscript. A full risk of bias table includes columns identifying (a) each study, (b) the answers to each guiding question for each domain, (c) each of the six risk of bias judgements (the five domains, plus the overall risk), and (d) free text to support the results. The full table ensures transparency of the process, but is typically too lengthy to include in publications. Reviewers could make the full risk of bias table available upon request or journals can store them as supplementary information. Another table is the traffic light plot as illustrated in . The traffic light plot presents the risk of bias judgments for each domain across each study. The plot helps readers decide which domains are rated low or high consistently across a set of studies. Readers can use the information to guide their interpretations of the main findings of the review and to identify ways to improve future research. Reviewers can also include a Summary Plot to show the relative contribution studies have made to the risk of bias judgments for each domain. presents an example based on the information from . The summary plot in is unweighted, meaning each study contributes equally. For example, from the outcome measurement bias results in , eight studies were rated as low risk and two were rated as high risk, hence the low risk category makes up 80% of the relevant bar in . Reviewers might produce a summary plot where each study’s contribution is weighted according to some measure of study precision (e.g. the weight assigned to that study in a meta-analysis).

Table 1. Traffic Light Plot.

The ROB2 method illustrates several features of high-quality critical appraisal. First, it is transparent and readers can access all the information reviewers created or assembled in their evaluations. Second, the method is methodical and the ROB2 resources ensure that each study of the same design is assessed according to the same criteria. Third, the results are presented in ways that allow readers to use the information to help them interpret the credibility of the evidence. Further, the results of the ROB2 encourage readers to explore trends across a set of investigations, rather than focusing on individual studies. Fourth, total scores are not calculated, and instead readers examine specific domains which provide more useful information. Finally, however, the Cochrane Collaboration acknowledges that ROB2 is tailored towards randomized controlled trials and is not designed for other types of evidence. For example, the Collaboration has developed the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I).

Critically appraising qualitative research

Illustrating the five steps for conducting a critical appraisal of quantitative research is more straightforward than for qualitative work. There is greater (but not complete) consensus among quantitative investigators about the process and possible criteria, but the same is not true for qualitative research. Rather than illustrate the steps with a specific example, the following discussion highlights issues reviewers benefit from considering when appraising qualitative research.

1. Identifying the Study Type(s) of the Individual Paper(s)

Tremendous variety exists in qualitative research with the existence of multiple traditions, theoretical orientations, and methodologies. Sometimes these various types need to be assessed according to different critical appraisal criteria (Patton, Citation2015; Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). The start of a strong critical appraisal of qualitative research begins with reviewers considering the ways the studies they are assessing are similar and different according to their ontological, epistemological, axiological, rhetorical, and methodological assumptions (Yilmaz, Citation2013).

2. Identifying Appropriate Checklist(s)

Widely conflicting opinions exist about the value of the checklists and tools available for a critical appraisal of qualitative research (Morse, Citation2021). Reviewers need to be aware of the benefits and limitations, and be prepared to justify their decisions regarding critical appraisal checklists. In making their decisions, reviewers benefit from remembering that standardized checklists and frameworks treat credibility as a static, inherent attribute of research. A qualitative study’s credibility, however, varies according to the reviewer’s purpose and the context for evaluating the investigation (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015). Critical appraisal is a dynamic process, not a static definitive judgement of research credibility. Although checklists and frameworks are designed to help appraise qualitative research in systematic and transparent ways, as highlighted checklists and frameworks are problematic and contested (Morse, Citation2021). Researchers thus need to select criteria suitable to the studies being assessed and for the review being undertaken. This means thinking of criteria not as predetermined or universal, but rather as a contingent and ongoing list that can be added to and subtracted from as the context changes.

3. Selecting an Appropriate Checklist or Criteria

To help select suitable criteria, reviewers can start by reflecting on their values and beliefs, so they are aware of how their own views and biases influence their interpretation of the primary studies. Critical friends can also be useful here. Self-reflection and critical friends will help reviewers identify (a) the critical appraisal criteria they think are relevant to their project, and (b) the tools that are coherent with those criteria and suited to the task. Further, reviewers aware of their values, their beliefs, and the credibility criteria suitable to their projects will be in strong positions to justify the tools they have used. A reviewer who selects a tool/checklist/guideline because it is convenient or popular, abdicates responsibility for ensuring the critical appraisal reflects the existing research fairly and makes a meaningful contribution to the review.

4. Performing the Appraisal

Regarding qualitative research, a checklist may capture some criteria that are appropriate for critically appraising a study or review. At other times the checklist may contain criteria that are not appropriate to judge a study or review. For example, most checklists do not contain criteria appropriate for judging post-qualitative inquiry (Monforte & Smith, Citation2021) or creative analytical practices like an ethnodrama, creative non-fiction, or autoethnography (Sparkes, Citation2002). What is needed when faced with such research are different criteria; a new list to work with and apply to critically evaluate the research. At other times guidelines may contain criteria that are now deemed problematic and perhaps outdated. Hence, it is vital to not only stay up-to-date with contemporary debates, but also to avoid thinking of checklists as universal, as complete, as containing all criteria suitable for all qualitative research. Checklists are not a final or exhaustive list of items a researcher can accumulate (e.g. 20 items, scaled 1–5) and then apply to everyone’s research, and conclude that those studies which scored above an arbitrary cut-off point are the best or should automatically be included in a synthesis. Checklists are starting points for judging research. The criteria named in any checklist are not items to be unreflexively ‘checked’ off, but are part of a list of criteria that is open-ended and ever subject to reinterpretation, so that criteria can be added to the list or taken away. Thus, some criteria from a checklist might be useful to draw on to critically appraise a certain type of qualitative study, but not other studies. What is perhaps wise moving forward then is to drop the term ‘checklist’ given the problems identified with the assumptions behind ‘checklists’ and adopt the more flexible term ‘lists’. The idea of lists also has the benefit of being applicable to different kinds of qualitative research underpinned by social constructionism, social constructivism, pragmatism, participatory approaches, and critical realism, for example.

5. Summarising, Reporting, and Using the Results

Authors reviewing qualitative research, similar to their quantitative counterparts, do not always use or optimize the use or value of their critical appraisals. Just as reviewers can undertake a sensitivity analysis on quantitative research, they can also apply the process to qualitative work (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015). The purpose of a sensitivity analysis is not to justify excluding studies because they are of poor quality or because they lack specific methodological techniques or procedures. Instead a sensitivity analysis allows reviewers to discover how knowledge is shaped by the research designs and methods investigators have used (Tod, Citation2019). The contribution of a qualitative study is influenced as much by researcher insight as technical expertise (Williams et al., Citation2020). Further, sometimes it is difficult to outline the steps that led to particular findings in naturalistic research (Hammersley, Citation2006). Reviewers who exclude qualitative studies that fail to meet specific criteria risk excluding useful insights in their systematic reviews.

Issues related to a critical appraisal of individual studies

The current manuscript focuses on the critical appraisal of individual studies. Two related issues include assessing the body of literature and evaluating the systematic review.

Appraising the body of research

The critical appraisal of individual studies occurs within the broader goal of exploring how a body of work contributes to knowledge, policy, and practice. Methods exist to help reviewers assess how the research they have examined can contribute to practice and real world impact. For example, GRADE (Grading Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation, Guyatt et al., Citation2011) is designed for reviews of quantitative research and is undertaken in two broad phases. First, reviewers conduct a systematic review (a) to generate a set of findings and (b) to assess the quality of the research. Second, review findings are combined with information on available resources and stakeholder values to establish evidence-based recommendations for policy and practice. For example, Noetel et al. (Citation2019) used GRADE procedures to establish low confidence in the quality of the evidence for mindfulness interventions on sport performance. Based on these results practitioners might justify using mindfulness because athletes have requested such interventions, but not on the basis of scientific evidence. Noetel et al. (Citation2019) illustrates how assessing the body of research can help reviewers contribute to the knowledge translation of their work.

Appraising the systematic review

The research community gains multiple benefits from critically appraising systematic reviews (Tod, Citation2019). First, prior to submitting their reviews to journals, investigators can find ways to improve their work. Also, by reflecting on their projects, they can enhance their knowledge, skills, and competencies so that subsequent reviews attain higher quality. Second, assessing a systematic review helps authors, readers, and peer reviewers decide how much the project contributes to knowledge or practice. Third, critically appraising a systematic review can help readers decide if the findings are strong enough to act upon. Stakeholders draw on systematic reviews when making policy and practice recommendations. Sport and exercise psychologists use systematic reviews to guide their work with clients. Poor quality reviews hinder practice, waste public and private resources, and may lead to practices that harm people’s wellbeing and health. Also, poor quality reviews can damage the credibility of sport and exercise psychology as a discipline if they support interventions that are ineffective or harmful. Systematic reviews are becoming more plentiful within sport, exercise, physical activity, health, and medical sciences. Along with increased frequency of publication, numerous reviews are (a) redundant and not adding to knowledge, (b) providing misleading or inaccurate results, and (c) adding to consumer confusion because of conflicting findings (Ioannidis, Citation2016; Page & Moher, Citation2016). Individuals able to critically appraise systematic reviews can avoid making practice and policy decisions based on poor quality reviews.

To assess a systematic review, individuals can use existing checklists, tools, and frameworks. These tools allow evaluators achieve increased consistency when assessing the same review in quantitative research. Examples include AMSTAR-2 (Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews-2; Shea et al., Citation2017) and ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews, Whiting et al., Citation2016). When using ROBIS, for example, evaluators assess four domains through which bias may appear in a systematic review: (a) study eligibility criteria, (b) identification and selection of studies, (c) data collection and study appraisal, and (d) data synthesis and findings.

Regarding a review of qualitative research, a checklist may capture some criteria that are appropriate. At other times the checklist may contain criteria that are not appropriate to judge a review. What is needed when faced with such reviews are different criteria; a new list to work with and apply to critically evaluate the work. At other times guidelines may contain criteria that are now deemed problematic and perhaps outdated. Hence, it is vital to stay up-to-date with contemporary debates, and avoid thinking of checklists as universal, as complete, as containing all criteria suitable for all reviews of qualitative research. Similar to judging qualitative research, if people insist on using checklists and that term, then these ‘checks off lists’ need to be considered as partial starting points for judging reviews of qualitative investigations. Unreflexive thought does a disservice to the authors of the primary evidence and may influence readers’ interpretations of a review’s findings in unsuitable ways.

Conclusion

Critical appraisals are relevant, not just to systematic reviews, but to whenever people assess evidence, such as expert statements and the introductions to original research reports. Systematic review procedures help sport and exercise psychology professionals to synthesize a body of work in a transparent and rigorous manner. Completing a high quality review involves considerable time, effort, and high levels of technical competency. Nevertheless, systematic reviews are not published to simply showcase the authors’ sophisticated expertise, or because they are the first review on a topic. The methodological tail should not wag the dog. Instead, systematic reviews are publishable when they advance theory, justify the use of interventions, drive policy creation, or stimulate a research agenda (Tod, Citation2019). Influential reviews are more than descriptive summaries of the research: they offer novel perspectives or new options for practice. Highly influential reviews scrutinize the quality of the research underpinning the evidence, to allow readers to gauge how much confidence they can attribute to study findings. Reviewers can enhance the impact of their work by including a critical appraisal that is as rigorous and transparent as their examination of the phenomenon being scrutinized. This article has discussed issues associated with critical appraisal and offered illustrations and suggestions to guide practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology

International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology

Journal of Applied Sport Psychology

Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology

Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology

International Journal of Sport Psychology

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology

Journal of Sport Psychology in Action

Psychology of Sport and Exercise

Sport and Exercise Psychology Review

Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology

The Sport Psychologist

References

- Amonette, W. E., English, K. L., & Kraemer, W. J. (2016). Evidence-based practice in exercise science: The six-step approach. Human Kinetics.

- Andersen, M. B. (2005). Coming full circle: From practice to research. In M. B. Andersen (Ed.), Sport psychology in practice (pp. 287–298). Human Kinetics.

- Booth, A. (2007). Who will appraise the appraisers?—The paper, the instrument and the user. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 24(1), 72–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00703.x

- Booth, A., Carroll, C., Ilott, I., Low, L. L., & Cooper, K. (2013). Desperately seeking dissonance: Identifying the disconfirming case in qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 23(1), 126–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312466295

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. Sage.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley.

- Bornmann, L., & Mutz, R. (2015). Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(11), 2215–2222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23329

- Buccheri, R. K., & Sharifi, C. (2017). Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines for evidence-based practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(6), 463–472. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12258

- Carroll, C., & Booth, A. (2015). Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: Is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Research Synthesis Methods, 6(2), 149–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1128

- Carroll, C., Booth, A., & Lloyd-Jones, M. (2012). Should we exclude inadequately reported studies from qualitative systematic reviews? An evaluation of sensitivity analyses in two case study reviews. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1425–1434. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452937

- CEBM. (2021). Study designs. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/study-designs

- Chalmers, I., & Altman, D. G. (1995). Systematic reviews. BMJ Publishing.

- Chambers, C. (2019). The seven deadly sins of psychology: A manifesto for reforming the culture of scientific practice. Princeton University Press.

- Crowe, M., & Sheppard, L. (2011). A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: Alternative tool structure is proposed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008

- Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 52(6), 377–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.52.6.377

- Flyvbjerg, B., Landman, T., & Schram, S. (Eds.). (2012). Real social science: Applied phronesis. Cambridge University Press.

- Gastel, B., & Day, R. A. (2016). How to write and publish a scientific paper (8th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Goldacre, B. (2011). Forward. In I. Evans, H. Thornton, I. Chalmers, & P. Glasziou (Eds.), Testing treatments: Better research for better healthcare (pp. xi). Pinter & Martin.

- Goldstein, A., Venker, E., & Weng, C. (2017). Evidence appraisal: A scoping review, conceptual framework, and research agenda. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 24(6), 1192–1203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocx050

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Gunnell, K., Poitras, V. J., & Tod, D. (2020). Questions and answers about conducting systematic reviews in sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 297–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1695141

- Guyatt, G., Oxman, A. D., Akl, E. A., Kunz, R., Vist, G., Brozek, J., Norris, S., Falck-Ytter, Y., Glasziou, P., & Debeer, H. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

- Hammersley, M. (2006). Systematic or unsystematic: Is that the question? Some reflections on the science, art, and politics of reviewing research evidence. In A. Killoran, C. Swann, & M. P. Kelly (Eds.), Public health evidence: Tracking health inequalities (pp. 239–250). Oxford University Press.

- Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2017). Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In J. P. T. Higgins, R. Churchill, J. Chandler, & M. S. Cumpston (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 5.2.0). https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Higgins, J. P. T., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2020). Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. Cochrane Collaboration. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Ioannidis, J. P. (2016). The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The Milbank Quarterly, 94(3), 485–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12210

- Jadad, A. R., Moore, R. A., Carroll, D., Jenkinson, C., Reynolds, D. J. M., Gavaghan, D. J., & McQuay, H. J. (1996). Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

- Johansen, M., & Thomsen, S. F. (2016). Guidelines for reporting medical research: A critical appraisal. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2016, Article 1346026. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1346026

- Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin.

- Katrak, P., Bialocerkowski, A. E., Massy-Westropp, N., Kumar, V. S., & Grimmer, K. A. (2004). A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 4(1), 22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-4-22

- Lasserson, T. J., Thomas, J., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2021). Starting a review. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 6.2). Cochrane. https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Liabo, K., Gough, D., & Harden, A. (2017). Developing justifiable evidence claims. In D. Gough, S. Oliver, & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd ed., pp. 251–277). Sage.

- Maher, C. G., Sherrington, C., Herbert, R. D., Moseley, A. M., & Elkins, M. (2003). Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Physical Therapy, 83(8), 713–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/83.8.713

- Majid, U., & Vanstone, M. (2018). Appraising qualitative research for evidence syntheses: A compendium of quality appraisal tools. Qualitative Health Research, 28(13), 2115–2131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104973231878535

- McGettigan, M., Cardwell, C. R., Cantwell, M. M., & Tully, M. A. (2020). Physical activity interventions for disease-related physical and mental health during and following treatment in people with non-advanced colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, Article CD012864. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012864.pub2

- Monforte, J., & Smith, B. (2021). Introducing postqualitative inquiry in sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1881805

- Morse, J. (2021). Why the Qualitative Health Research (QHR) review process does not use checklists. Qualitative Health Research, 31(5), 819–821. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732321994114

- NICE. (2021). Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance: Reviewing the scientific evidence. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/reviewing-the-scientific-evidence#Quality-assessment

- Noetel, M., Ciarrochi, J., Van Zanden, B., & Lonsdale, C. (2019). Mindfulness and acceptance approaches to sporting performance enhancement: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(1), 139–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1387803

- Nuzzo, R. (2015). How scientists fool themselves–and how they can stop. Nature News, 526(7572), 182–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/526182a

- Page, M. J., & Moher, D. (2016). Mass production of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: An exercise in mega-silliness? The Milbank Quarterly, 94(3), 515–519. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12211

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage.

- Pawson, R. (2006). Digging for nuggets: How ‘bad’research can yield ‘good’evidence. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 9(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570600595314

- Pawson, R., Boaz, A., Grayson, L., Long, A., & Barnes, C. (2003). Types and quality of social care knowledge. Stage two: Towards the quality assessment of social care knowledge. ESRC UK Center for Evidence Based Policy and Practice.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell.

- Protogerou, C., & Hagger, M. S. (2020). A checklist to assess the quality of survey studies in psychology. Methods in Psychology, 3, 100031. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2020.100031

- Pussegoda, K., Turner, L., Garritty, C., Mayhew, A., Skidmore, B., Stevens, A., Boutron, I., Sarkis-Onofre, R., Bjerre, L. M., & Hróbjartsson, A. (2017). Systematic review adherence to methodological or reporting quality. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), Article 131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0527-2

- Quigley, J. M., Thompson, J. C., Halfpenny, N. J., & Scott, D. A. (2019). Critical appraisal of nonrandomized studies—A review of recommended and commonly used tools. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 25(1), 44–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12889

- Sackett, D. L., Richardson, S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. B. (1997). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. WB Saunders Company.

- Sagan, C. (1996). The demon-haunted world: Science as a candle in the dark. Random House.

- Santiago-Delefosse, M., Gavin, A., Bruchez, C., Roux, P., & Stephen, S. (2016). Quality of qualitative research in the health sciences: Analysis of the common criteria present in 58 assessment guidelines by expert users. Social Science & Medicine, 148, 142–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.007

- Shea, B. J., Reeves, B. C., Wells, G., Thuku, M., Hamel, C., Moran, J., Moher, D., Tugwell, P., Welch, V., & Kristjansson, E. (2017). AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. British Medical Journal, 358, j4008. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Sparkes, A. C. (1998). Validity in qualitative inquiry and the problem of criteria: Implications for sport psychology. The Sport Psychologist, 12(4), 363–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.12.4.363

- Sparkes, A. C. (2002). Telling tales in sport and physical activity: A qualitative journey. Human Kinetics.

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2009). Judging the quality of qualitative inquiry: Criteriology and relativism in action. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(5), 491–497. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.02.006

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise, and health: From process to product. Routledge.

- Sterne, J. A. C., Hernán, M. A., McAleenan, A., Reeves, B. C., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2020). Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. Cochrane Collaboration. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Sterne, J. A., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H.-Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). Rob 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. British Medical Journal, 366, Article 14898. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Thomas, D. R. (2017). Feedback from research participants: Are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2016.1219435

- Tod, D. (2019). Conducting systematic reviews in sport, exercise, and physical activity. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tod, D., & Van Raalte, J. L. (2020). Evidence-based practice. In D. Tod & M. Eubank (Eds.), Applied sport, exercise, and performance psychology: Current approaches to helping client (pp. 197–214). Routledge.

- Walach, H., & Loef, M. (2015). Using a matrix-analytical approach to synthesizing evidence solved incompatibility problem in the hierarchy of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(11), 1251–1260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.03.027

- Wendt, O., & Miller, B. (2012). Quality appraisal of single-subject experimental designs: An overview and comparison of different appraisal tools. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(2), 235–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2012.0010

- Whiting, P., Savović, J., Higgins, J. P., Caldwell, D. M., Reeves, B. C., Shea, B., Davies, P., Kleijnen, J., & Churchill, R. (2016). ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 69, 225–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005

- Whiting, P., Wolff, R., Mallett, S., Simera, I., & Savović, J. (2017). A proposed framework for developing quality assessment tools. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0604-6

- Williams, V., Boylan, A.-M., & Nunan, D. (2020). Critical appraisal of qualitative research: Necessity, partialities and the issue of bias. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 25(1), 9–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111132

- Yilmaz, K. (2013). Comparison of quantitative and qualitative research traditions: Epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. European Journal of Education, 48(2), 311–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12014