ABSTRACT

In the field of sport and exercise psychology, the systematic review is still considered by many, to be the gold standard literature review. However, reviews like these, which judge whether an intervention works or not, can leave many unanswered questions. When it comes to complex social interventions, failing to suggest reasons for an intervention’s efficacy, often means practitioners struggle to successfully implement research findings in the real world. This lack of detail has led many to question the utility of systematic reviews when examining behaviour change interventions in complex social environments. Realist reviews are increasing in popularity because they go beyond asking if an intervention works, to look for theories as to why a programme worked, who it worked for and in what context it worked. However, despite the growing popularity of realist reviews, there is still limited application of this approach across the sport and exercise sciences. This paper aims to increase awareness regarding the utility of realist research by offering an introduction to realist review and an explanation of the steps involved.

Background

In the field of sport and exercise psychology, meta-analyses and the Cochrane style systematic review are still considered to be the gold standard for literature reviews (Tod, Citation2019). Well-conducted systematic reviews and meta-analysis summarise and integrate results on the same topic from different studies generating an estimate of the ‘true’ effect size of ‘what works’. Over time, as more studies are conducted and synthesised, this effect size becomes increasingly refined, and confidence grows around the result. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses can be used to explore heterogeneity of effect and the possibility of publication bias. However, the focus on ‘what works’ ignores the complexity in behavioural interventions where both individual and contextual differences interact to influence intervention outcomes. In addition, it masks the fact that in any intervention some participants improve, some stay the same, and some unfortunately get worse. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses can tell you if an intervention works but they cannot tell us much about why, how or for whom it worked. For this reason, researchers in fields related to sport and exercise psychology are increasingly using realist reviews to complement the findings of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (see for example: Booth et al., Citation2019; Brown et al., Citation2017; Enright et al., Citation2020; Gagliardi et al., Citation2015). Instead of viewing variation in the data as problematic, realist research examines the anomalies in the data to see what they can tell us about how the intervention works in one context for some people and in a different way for others. In other words, a realist review attempts to unpack ‘what works’ and explores the literature with the specific intention of seeking out the data anomalies and examining the outcomes of an intervention across the entire spectrum of results. In this way a realist review leads to a fuller understanding of how intervention effects are produced.

For research to have more impact on the development and implementation of behaviour change programmes, there is a need to know more than the effect size of an intervention (Fox, Citation2017; Oliver et al., Citation2014). A realist review is a type of systematic literature review which is characterised by its explanatory focus (Wong et al., Citation2014). Instead of judging the effectiveness of an intervention, a realist review is concerned with answering how an intervention works, who it works for and in what circumstances it works. Reporting on answers to these questions is the reason why some have argued realist reviews are better able to make pragmatic recommendations for intervention implementation in sport and exercise medicine (Gledhill & Forsdyke, Citation2021).

The aim of this paper is twofold. Firstly, it illustrates what a realist review is and why it offers a valuable way for reviewing the literature on sport and exercise psychology interventions and programmes. Secondly, in an attempt to make the realist approach more accessible, the paper outlines the steps involved and provides a diagrammatic overview of how to apply Pawson’s (Citation2006a, p. 6) stages of a realist review. A table of common terms and definitions used in a realist research can be found in .

Table 1. Common terms and definitions in a realist review.

Realist review

The complexity and fluctuations inherent in social and behavioural interventions have prompted some to argue that traditional systematic reviews are ill-suited to examining social programmes (Astbury & Leeuw, Citation2010; Greenhalgh et al., Citation2014). Based on positivist and successionist logic, the typical focus of a traditional systematic review is to judge the effectiveness of an intervention (Pawson, Citation2002). The definition of a traditional systematic review used in this paper has been taken from the EPPI-Centre whose work in research synthesis is used across many areas of social policy, including but not limited to education, health, and sport (EPPI-Centre, Citation2019). Their definition of a systematic review is one that follows a standardised number of steps in an explicit and transparent way ensuring that it is accountable, replicable, and updateable. In addition, users are included in the research process to ensure the findings are relevant and useful. To ensure their methods are transparent and reproducible, systematic reviews attempt to control for, and remove, all extraneous causal factors from their analysis. However, critics argue that this type of design cannot be applied to the uncontrollable messiness of the real world (Chen, Citation2015).

To address some of the limitations inherent in the systematic review, other approaches to evidence synthesis, such as the scoping review, have been gaining in popularity (Thomas et al., Citation2017). A scoping review is interested in discovering how much is known about a particular research area; what the key concepts are; and what type of research activity has taken place in the field (Munn et al., Citation2018). Although it has value as a stand-alone piece of research, a scoping review can be a valuable precursor to a systematic review by identifying gaps in the existing knowledge base to determine if there is value in undertaking a full systematic literature review (Levac et al., Citation2010). Scoping reviews share many characteristics of a realist review; they include stakeholder consultations; have a flexible and iterative structure; and include literature from diverse sources with different methodological approaches (Thomas et al., Citation2017). However, the two reviews answer fundamentally different questions; the scoping review asks what is known about X and what strategies have been used to obtain this knowledge? Whereas a realist review asks what is it about this social programme that works, why, how, and for whom does it work and in what context? In addition, a realist review, unlike a scoping review, is a theory-led form of research which underpins its explanatory approach and makes it particularly suited to evaluating complex interventions.

As social interventions become more complex it is increasingly recognised that theory-informed research methods, such as a realist evaluation and synthesis, provide valuable additions to the knowledge base (Pawson et al., Citation2005). Whilst acknowledging that no intervention is likely to be ‘simple’ the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (Moore et al., Citation2015) described a complex intervention as one that is multi-faceted, with numerous interacting components that may often require tailoring or adaptation, and which is subject to the influences of those delivering and receiving the intervention with differing results as a consequence (Craig et al., Citation2008). Scientific realism was specifically developed to help researchers, policy makers, and practitioners make sense of complex interventions (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). For realists, the success and failure of a social programme lies in the complex relationship that exists between the resources the intervention has to offer, the context in which it was implemented, and the reactions of users (Pawson, Citation2006a). In scientific realism, to control for human influences, would remove the very means by which an intervention does or does not work (Pawson, 2016). In order to fully examine what makes a social programme complex, Pawson developed a ‘checklist’ under the acronym VICTORE (Volitions, Implementation, Contexts, Time, Outcomes, Rivalry, and Emergence) (Pawson, Citation2013, p. 33). Completing the VICTORE checklist was suggested to be a useful means by which to ‘map’ complexity and identify potential areas where further empirical research was needed (Pawson, Citation2013, p. 33). Illustrating this point, Cooper et al. (Citation2020) used the VICTORE checklist in their realist research of adolescent risk behaviour prevention, to help them create their initial rough programme theories.

It was the inherent complexity in exercise engagement programmes for people living with COPD and frailty that led Brighton et al. (Citation2020) to conduct a realist review of the literature. Brighton et al. (Citation2020) acknowledged that prior research had shown exercise interventions to be beneficial for this demographic but understanding how and why some exercise interventions were more effective than others remained unknown. The conclusions of Brighton et al. (Citation2020) review went beyond answering if engagement with exercise was beneficial for people living with frailty and COPD to identify several factors that influenced how and why and in what context some people were more engaged than others. A realist review is a literature synthesis that embraces and explicates complexity to go beyond answering to what extent a programme was effective to explaining why, for whom, in what circumstances it would be effective. The differences between traditional systematic review and a realist review are summarised in .

Table 2. Differences between a traditional systematic review and a realist review.

The realist philosophical foundations

Before the realist review process is explained, it is crucial to acknowledge the philosophical foundation within realism. Understanding the ontological and epistemological position of scientific realism is important as it guides the questions the researcher asks and the way they look for and analyse data. Moreover, this is also important because it provides a sound rationale for the application of realist reviews within psychological studies that are often embroiled in complexity. Pawson and Tilley’s scientific realism draws on Bhaskar’s stratified ontology (Bhaskar, Citation1975, Citation2014) which divided reality into three, overlapping layers: the empirical, the actual, and the real. The empirical domain is the level at which phenomena can be observed and measured; in the actual domain, phenomena exist and have real effects on outcomes but are not directly observable and in the domain of the real, phenomena are unobservable with latent potential that, when the context is right, can become activated. It is because of their position that reality is stratified that scientific realism places an emphasis in their research on obtaining ‘ontological depth’. Ontological depth describes the process of going ‘below’ the empirical level to build an explanation of a phenomenon by theorising about what is happening at different layers of reality. Jagosh (Citation2019) used the metaphor of an iceberg to depict the concept of ontological depth. The empirical layer was envisaged as the tip of the iceberg that could be seen sticking out of the water and, as one sinks below the water (a reference to ontological depth) we begin to take in the domain of the actual and then, deeper still, the domain of the real.

A central premise in realist ontology is the assumption that although things cannot be seen they are no less real and, furthermore, even if they cannot be seen they can still have an effect on reality. This assumption reflects the premise of a ‘mind independent reality’. For realists, reality has an independent and intrinsic nature that exists outside of our ability to see it or conceive of it (Lehe, Citation1998). This view of reality is reflected in the notion of generative causality. Put at its simplest, generative causation is the idea that what is happening under the surface – unseen – generates something to happen at the top which we can see. In scientific realism, these unobservable, causal phenomena, are referred to as mechanisms. When studying a social programme, mechanisms are a combination of the resources being offered by the programme and the reasoned response the programme users have to those resources (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). Exploring how mechanisms work within a particular context is central to realist research (Gough et al., Citation2017).

This generative model of causation proposes that in order to understand how X and Y brought about a respective outcome, one must appreciate what the underlying mechanism(s) might be and show an appreciation for how context influences the way the relationship plays out. This is what Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997) and Dalkin et al., (Citation2015) refer to as the commonly applied context, mechanism, and outcomes (CMOs) configurations that help to explain this retroductive causation of how and why things work.

The epistemological position of scientific realism aligns with a constructivist paradigm (RAMESES II Project, Citation2017a). Constructivism is an epistemology that asserts that all knowledge is constructed by an individual’s perceptions of the world. In realist research, this knowledge is not only subjectively constructed but is also built on abductive and retroductive logic. Abduction is the creative inference required to imagine underlying causal mechanisms and retroduction is the theorising needed to develop a way of ‘testing’ whether these mechanisms exist (Jagosh Citation2020). Abduction has been described as a form of reasoning which examines evidence and makes inferences based on ‘educated guess work’ and ‘informed hunches’ about the causal factors linked to that evidence (Jagosh et al., Citation2013, p. 135). It is for this reason that realist research has been described as being evidence informed rather than evidence based (Jagosh et al., Citation2013). Anti-realists may criticise the use of abductive logic as simply ‘guess work’ but advocates would counter by arguing that abduction is the only way to introduce new ideas into the scientific evidence base (Tavory & Timmermans, Citation2014).

CMO configurations are theories about the relationship between mechanisms and context that bring about a particular outcome. To unpack this further, in a particular situation which has its own unique, dynamic, and emergent features (Greenhalgh & Manzano, Citation2021) (context), a resource is introduced (mechanism resource), which then evokes reasoning (mechanism reasoning) in the mind and/or social system that leads to an outcome (O) (Harris, Citation2018). Context is a central force within realist review and realist approaches. As supported by Greenhalgh and Manzano (Citation2021) context is not a single, static, and abstract component; instead, it is a ‘force and relates to the psychological, organisational, economic and technical relationships that influence each other’ (p. 8) to continually drive our explanations. Context, in essence, shapes the way mechanisms and outcomes present themselves and it is omnipresent throughout the whole CMO process. Overall, this process helps to explain the deeper and hidden processes of causality to not just understand ‘is this effective’ but ‘why, how and for whom is it effective’ (Mason et al., Citation2021).

Within the field of sport and exercise psychology, this is crucial because sport and exercise psychologists of industry and academic orientation are interested in understanding how and why psychological factors influence performance and/or participation. What is more, in accordance with context, they seek to appreciate the way ‘systems of interactions, meaning, rules and sets of relationships shape stakeholders’ reasoning in response to programme resources and consequently, influence outcomes’ (Greenhalgh & Manzano, Citation2021, p. 4). For example: If coaches give tailored support and encouragement [resource] to young athletes with low self-efficacy [context] then this personalised attention may instil in the young athletes a sense of self-worth and validation [mechanism] as well as a desire to ‘prove themselves’[mechanism] to a coach who has taken the time to get to know them and their needs [context]. This ultimately boosts the young athletes’ confidence towards performing better within their sport [outcome]. In this example, a systematic review would have been an appropriate choice of evidence synthesis if the researcher wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of this coaching programme. However, if a researcher were interested in the complexities of the programme and how it brought about behaviour change i.e. finding out who it worked for (athletes with low self-efficacy), why it worked (boosting self-worth, validation and eliciting a desire to prove themselves) and in what context (coaches who dedicated time, tailored support, and encouragement) then a realist review would arguably have been a preferable choice. Since people have different beliefs, attitudes, perceptions, and understandings, reactions to intervention resources can be different which, in turn, may lead to different mechanisms being generated and result in different outcomes. Generative causation enables a realist researcher to identify patterns of behaviour and make sense of a programme’s inherent complexity. It is this mode of inquiry that enables researchers to move beyond answering if an intervention works to dig deeper and to explore what works, for whom and in what circumstance.

What is a realist review?

In its attempt to discover the underlying explanation as to how a programme works, a realist review will develop programme theories and test these theories against the literature. A programme theory is an idea about how the programme is thought to work: If we do X then Y will happen because of Z. In order for it to be a realist programme theory, it must refer to the context and mechanisms and how they relate to outcomes (RAMESES II Project, Citation2017b). A realist review synthesises the intervention literature, looking for underlying causal forces that might explain why behaviour change interventions work in one context and not in another. Since this detail is likely to have been removed from empirical literature that values randomised controlled data, a realist review must look at a diverse range of literature sources for ideas with which to build programme theories. Piecing this array of literature together helps the researcher build a tacit understanding of underlying mechanisms, whilst recognising how the various features of context influence them. As such, this can facilitate theories as to how context may shape why interventions work differently for some people and not for others.

The aim of a realist review is to develop plausible explanations from patterns of observations that have surfaced from the literature and create transferable theories that inform programme implementation in different settings (Marchal et al., Citation2012). Drawing on the work of Merton (Citation1967) and Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997) describe these transferable theories as ‘middle range theories’. Merton divided theory into three levels: low level, mid-range, and grand theory (Noyes et al., Citation2016). Although the lines between each level can blur Merton described mid-range theory as sitting

between the minor but necessary working hypothesis that evolve in abundance during day-to-day research and the all-inclusive systematic effort to develop a unified theory that will explain all observed uniformities of social behaviour, social organisation and social change. (Merton, Citation1967, p. 448)

MRTs have been described as ‘bridges’ in that they provide explanatory links between one programme and another. This, in turn, helps enhance our overall understanding of how programmes, interventions or practices that share similar characteristics (also referred to as family of programmes) operate (Marchal et al., Citation2018). Although the precise details and contexts of an intervention may change over different domains, applying MRTs to evaluating similar programmes negates the need to start a review from scratch and, by extension, stops the ‘constant reinvention of the wheel’ (Astbury & Leeuw, Citation2010, p. 374). Lessons learnt from one study can be used as a starting point for another. Pawson (Citation2018) describes this accumulated knowledge as ‘reusable conceptual platforms’ or ‘mechanism libraries’ (p. 214) which can be used as launch pads for further discovery.

Unlike a traditional systematic review, a realist review is not supported by a predefined and rigid methodology. Instead, it has a flexible and iterative nature, with steps that overlap or repeat as new insights emerge. Being able to mould the realist approach to the body of evidence under review is seen as a strength of realist research. Its malleable nature offers the potential for innovation (Booth et al., Citation2019) and can optimise the review outcomes; improve knowledge translation and facilitate decision making (Jagosh et al., Citation2013, p. 132). Indeed, the philosophy and logic that underpins realist reviews rejects the notion that this form of research can be undertaken in a standardised or prescriptive fashion (Jagosh et al., Citation2013). For this reason, early advice to realist researchers strongly advised against the pre-publication of protocols since the purpose and direction of the review may not be known from the outset and to constrict the research team to a set of predefined goals and objectives was not in keeping with the iterative nature of realist work (Pawson et al., Citation2004, p.15). However, later guidance from the RAMESES group (a project developed to provide guidance, training and reporting standards on realist evaluation and synthesis) suggest that there is value in publishing and registering protocols (RAMESES II Project, Citation2017c) and RAMESES have published practical guidance and reporting standards for realist reviews (Wong et al., Citation2013, Citation2014). After 2013, when the World Medical Association (WMA, Citation2013), called for all research studies involving a human subject to be registered, rosters like The Research Registry were created to register trials across the entire spectrum of research designs (Agha & Rosin, Citation2015). The implication for realist reviews is that whereas once they may not have been accepted on some registers because their studies do not adhere to a strict a priori criteria, now there are registers such as PROSPERO and The Research Registry that publish realist review protocols even though its methodology is emergent and iterative. As a result, the advice against pre-registration of realist research (Pawson et al., Citation2004, p.15) is arguably outdated.

The six stages of a realist review

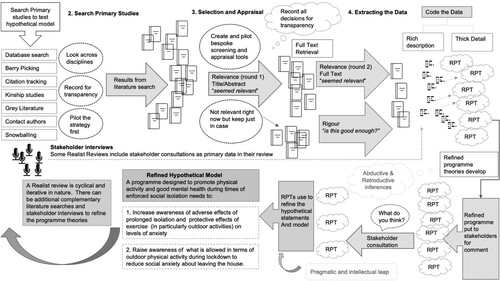

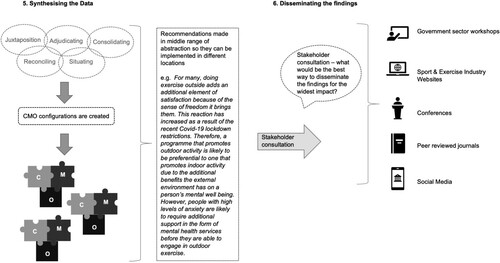

Whilst there are a number of ways to conduct a realist review with differing numbers of steps (Maidment et al., Citation2017; Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2012), these variations in structure support the argument that realist research does not have a prescriptive method but rather, guiding principles. However, Pawson (Citation2006a, p. 79) did identify six stages for a realist review which are outlined in and will be expanded upon further in the subsequent sections. Although there are six stages, it is important to stress that conducting a realist review is not a linear process. It is only for clarity in this paper that the stages are written as if they follow a neat sequential pattern. In practical application, these stages can overlap and be revisited. To illustrate this point, we have provided a diagrammatic representation of what a realist review in the field of sports and exercise psychology might look like (). This illustration has been influenced by Robert Horn’s (Citation2001) concept of knowledge mapping and visual language to facilitate an understanding of how to navigate complex processes. It is not meant as a recipe to be followed but rather as a cognitive map to guide readers and help them visualise the application of the realist methodology. This is important since it has been noted that a paucity of methodological guidance has led to a lack of clarity around the realist review process (Berg & Nanavati, Citation2016). In addition, it has been suggested that further methodological guidance would support consistent application of realist principles and contribute to transparency of process (Shearn et al., Citation2017. p. 2).

Figure 1. (a) Stage 1 in a Realist Review. Note: The first stage of a realist review is usually the most time-consuming. Legend. IRPT: initial rough programme theory. (Image is the property of author).

Table 3. Six stages of realist review.

1. Identify the review question

Focusing the review is arguably the most important (Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2012), challenging (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2014) and time-consuming step in the realist review process (Pawson, Citation2006a). A way to simplify the process is to divide this initial step into six intertwined processes outlined below.

Mapping the territory

To get an idea of how the programme is intended to work, what features seem important and what aspects are likely to encounter difficulties Pawson (Citation2006a) recommends exploring the literature around the programme to get the ‘lay of the land’. In a realist review, this is done by an exploratory and non-systematic scoping of the literature and by consulting with key stakeholders. For example, as a starting point for their realist review on the implementation of physical activity guidelines, Leone and Pesce (Citation2017) looked at the governmental plans and official statements around physical activity promotion issued by the main institutions and international networks involved in developing and implementing physical activity guidelines.

Concept mining

In this process of familiarisation, the research team identifies and defines key concepts with which to build a framework that can carry their research forward. Rycroft-Malone et al. (Citation2012) referred to this process as ‘concept mining’ and in their review, they consulted the literature and stakeholders to develop both their initial programme theories and to define key terms and wording. Clarifying the terminology in this way helps to ensure consistency in both language and concepts being used throughout the research.

Stakeholders

A key feature of the realist review is the involvement of stakeholders throughout the research process (Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2012). Stakeholders are people with ‘content expertise’ (Wong, Citation2018, p. 134) and can be, for example, any combination of programme users, policy makers, commissioners, or professional experts in the field. In their review on football interventions for men with mental health problems, Such et al. (Citation2019) consulted with mental health professionals, football coaches, and mental health service users. Stakeholder input can be used in a number of ways, from programme theory development and refinement, to providing credibility checks and giving advice on where to find additional sources of data (Wong, Citation2018). In addition, stakeholders can be consulted for advice as to the best means of disseminating the research findings. The extent of stakeholder involvement is not mandated and will vary across realist reviews however a key feature of a realist review is that it consults with stakeholders throughout the research to ensure the research focus is meaningful and the findings useful (Pawson et al., Citation2004).

Develop initial rough programme theories

From the consultations with stakeholders and the exploratory review of the literature, the researcher begins to construct initial rough programme theories (IRPTs). Theory building is an abductive and retroductive process (Jagosh et al., Citation2013) whereby inferences are made from the data based on the most likely and plausible explanation (Wong, Citation2018). How these IRPTs are created is often under-reported (Shearn et al., Citation2017; Wong et al., Citation2013). This does not help with the transparency of the research process, nor does it help novice researchers learn how to conduct realist research. There is no correct way to create an IRPT but, an example taken from the diagram () is shown in Box 1. using an ‘if/then/because’ framework.

Box 1. An initial rough programme theory created using an if/then/because framework.

If people with high levels of anxiety are given access to free mental health support

then they are more likely to engage in a programme designed to promote physical activity and good mental health during times of enforced social isolation

because they will have been given the reassurance they need to overcome their anxiety and the confidence and motivation to participate in physical activity

Articulate key theories to be explored

To help guide researchers to create theories about how a particular intervention brings about a change in the reasoning and response of its users, Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997) suggest using substantive theories. Substantive theories are pre-existing and usually well-established theories within a particular field that help to explain why things happen the way they do (Wong et al., Citation2013). This is why realist research is described as being ‘theory-led’. Realist research values the use of theory for the particular lens it gives researchers to produce novel insights on social behaviour (Marchel et al., Citation2018). Although there is a lack of realist research in the field of sport and exercise psychology, there are examples of theory informing research in this area. For example, Carr (Citation2009) explored how attachment theory could provide a useful ‘lens’ for sport and activity research particularly as it relates to goal achievement, motivational climate, and sport friendship. The theory of deliberate practise was used by Coughlan et al. (Citation2019) to examine performance improvement in Gaelic football players and Ntoumanis (Citation2001) examined motivation in a variety of sports using achievement goal theory and self-determination theory.

The advice on finding substantive theories is to ‘read widely’ in the literature as part of the initial mapping exercise (Pawson, 2006). However, a criticism levelled at theory-led research is the tendency for research teams to give preference to theories they are already familiar with (Booth & Carroll, Citation2015). To address this critique, Booth and Carroll (Citation2015) developed the BoHEMoTH framework (Behaviour of interest; Health context; Exclusions; Models; or Theories). Although the ‘HE’ relates to health this can be changed to any context, such as sport or education. The BoHEMoth framework helps to structure the search for behavioural change models/theories. Booth and Carroll (Citation2015) argue that using a framework such as theirs enables researchers to conduct a broad, systematic, and transparent literature search for theory to inform their research. When examining complex social programmes, researchers may decide to use more than one theory to help guide their research. Using a framework of three or four theories can help initial programme theory development at multiple levels of the social system e.g. interpersonal, institutional, infrastructural, and cultural (Shearn et al., Citation2017; Westhorp, Citation2013). Finally, Davidoff et al. (Citation2015) published a criteria to help researchers determine whether or not their chosen theories are ‘good’ ones.

It is likely that, in the process of focusing the review, by way of mapping, consultation, and theory building, many initial rough programme theories will be produced. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for programme theories, even in their initial ‘rough’ phase to go through many cycles of iteration (Wong et al., Citation2014). This is a valuable part of the research process whereby the researchers go back and forth in the literature to try and deepen their understanding of how the intervention is thought to work. However, whilst attempting to find clarity and focus, it is not unusual for researchers to become lost in a ‘swamp’ of programme theory (Pawson et al., Citation2004). Research time and budgets are limited so practical and pragmatic decisions need to be made with regards to the number of programme theories to be taken forward for evaluation (Pawson Citation2013).

To help exit the ‘swamp’ Pawson et al. (Citation2004) suggest taking one of four explanatory paths: to investigate programme integrity; to adjudicate between rival programme theories; to review the same theory in comparative settings; or, to review official expectations against actual practise (p. 15). Further explanation and hypothetical examples of these different paths are given in .

Table 4. Four explanatory paths to refine the purpose of a realist review.

Deciding on which ‘path’ to take helps the researcher to refine the purpose of the review and select the programme theories to take forward for further investigation (Pawson et al., Citation2004). Which direction to take will vary from one review to another but is likely to be influenced by any combination of the following: the funders or commissioners of the review, the key stakeholders, professional experience of the research team, an exploratory scope of the literature, and public policy (Pawson et al., Citation2004).

Formalise the model or subset of hypotheses to be tested

Once a set of programme theories have been decided upon, the final stage of focusing the review is to use these theories to create a hypothetical model of how the programme is thought to work. To help structure such a model it may be useful to think of an overarching question such as ‘what is it about this programme that is required in order for it to be a success’ and place the programme theories for testing underneath as illustrated in . Once the model has been built, the rough programme theories within it are ‘tested’ by a systematic search of the empirical evidence.

2. Search for primary studies

Although the literature search in a realist review is a systematic process, it is not conducted in the same way as traditional systematic reviews. Drawing on the work of Emmel (Citation2013), Booth et al. (Citation2018, p. 149) outline four important principles in a realist literature search. First, the search is likely to extend beyond the usual bibliographic databases. It is not uncommon for programme theories to be constructed from fragments of data collected from different sources. In their realist review of football interventions for men with mental health problems, Such et al. (Citation2019) acknowledged that there was a small amount of evidence to be found in the published literature and went to grey literature and contacted relevant authors to find data with which to build their programme theories. Booth et al. (Citation2013) suggest using a blended approach for this whereby keyword searches of bibliographic databases are supplemented with complementary search techniques such as citation tracking, purposive sampling, snowballing, berry-picking, and cluster searching. Second, the literature search needs to be both systematic and broad, including as many studies as the research timeframe and resources will allow. To accomplish this, the researcher is advised to look for data beyond the discipline in which their programme is situated (Wong, Citation2018). Using the research question in for example, this could mean looking for similar physical activity and mental health programmes outside the sports and exercise psychology literature for instance looking at education initiatives or economic programmes. Thirdly, theory testing is not straight-forward, and the literature search needs to be flexible to accommodate this. It is likely that the researcher will need to go back and forth to the literature as new insights emerge. This does not mean that the search is conducted in a haphazard manner, it still needs to be transparent and systematic, but the researcher may not know in advance where the search will take them. Finally, and related to this third point, Emmel (Citation2013) argues that a realist search is iterative. Additional literature searches will be needed, possibly across different disciplines, to explicate new findings or to refine elements of theory (Wong et al., Citation2014).

Due to the iterative style of a realist review, it is important that the researcher is transparent as to both, how and why each literature search was conducted and they must be meticulous in the recording and presentation of their methods. Standards have been published by the RAMESES group outlining the conduct and reporting principles expected in a quality realist review (Wong et al., Citation2014).

3. Selection and appraisal

A realist review does not adhere to the strict inclusion criteria of systematic reviews which traditionally place RCT data at the top of the evidence hierarchy. Instead, decisions on whether to include primary studies in the review are based on rigour and relevance (Box 2).

Box 2. Questions to help the researcher determine relevance and rigour in a realist review. Note: (1) Wong, (Citation2018); (2) Rycroft-Malone et al. (Citation2012); (3) Wong, (Citation2018).

Relevance: Does this piece of literature help to refine, refute, or substantiate programme theories?1

Rigour: Is this piece of literature good enough to be included?2 Were the methods used to generate the data credible, plausible, and trustworthy?3

Relevance

Relevant data in a realist review is determined by whether it can develop, refute, refine, or endorse the research programme theories (Wong, Citation2018). How relevant a piece of data is considered will depend how much detail it includes on processes, context, mediating factors, and empirical findings. In practical terms, there are usually two relevancy tests as illustrated in Maidment et al.’s (Citation2017) review. In their first screening, they reviewed the title and abstract and decided on a full-text retrieval if the literature ‘seemed relevant’. In their second screening, after they had reviewed the full text, they determined whether or not the evidence provided was good enough and relevant enough to be included in the review. Screening titles and abstracts might miss key causal insights or references to theories. As a result, it is likely that more papers will have to be read in their entirety, than in a traditional systematic review. Furthermore, a source which may have been screened as not relevant in one theory area could become relevant elsewhere (Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2012). For this reason, no paper is truly discarded. Instead, they are held in ‘reserve’ in case they can contribute at a later stage.

Rigour

When assessing rigour, researchers question whether or not the literature is good enough to be included. This judgement is made on whether the data is considered to be trustworthy, that is, have the data collection methods been made explicit and were they scientifically robust. Pawson et al., (Citation2004) suggest that sample size, data collection techniques, analysis methods, and research claims should be considered when making judgements on rigour. In addition, realist reviews may include useful pieces of data, which in and of themselves are of sufficient rigour to be included but may lie within a methodologically weak study (Pawson, Citation2006b). For this reason, a realist review does not adhere to the rigid inclusion and exclusion criteria typical of a traditional systematic review. A realist researcher is encouraged to be imaginative and inclusive with their data in order to build programme theories (Wong, Citation2018, p. 135). Pawson (Citation2006b) maintains that the ‘quality’ of evidence only really comes to light in the process of synthesis where – once triangulated – the inferences made by a particular piece of evidence is either substantiated or not.

After each literature search, the papers need to be selected and appraised. In both the selection, appraisal and analysis phases, bespoke screening tools are developed by the research team to filter the literature results (Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2012). The review questions and theoretical framework help the research team decide on what literature to include and exclude. These screening and appraisal tools are likely to go through a number of iterations and should be piloted first (Wong et al., Citation2014). Rigour is strengthened by having 10%–20% of the screened results checked for consistency by other members of the research team.

4. Extracting the data

Data extraction forms will be unique to each realist review depending on their theoretical framework. In addition, it is likely that a number of different extraction forms will be created due to the multiple sources of data being analysed (Pawson et al., Citation2004). For this reason, standard data extraction forms such as those found in The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Citation2019) are not appropriate because, in a realist review, each document may be reviewed for a different purpose or to find a different piece of information (Pawson, Citation2006a). Research is coded and a detailed record of how each piece of primary data contributed to the synthesis, including explanations of why some data was omitted, is made for transparency.

Data extraction should be theory driven (Pawson, Citation2006a) and the researcher is particularly looking for ‘conceptual richness’ and ‘contextual thickness’ (Booth et al., Citation2013). In other words, useful pieces of evidence are those that give detailed descriptions of programme conditions or make clear the thoughts and assumptions underlying the programme’s creation and outcomes. The aim of the extraction stage is to collect various bits of data and assimilate them into theories on how the programme is thought to work, why and in what context. To build theories on causal forces researchers must apply retroductive and abductive reasoning to make inferential leaps in their thinking about what might be going on unseen. For example, Enright et al. (Citation2020) found intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy were important mechanisms in successful ‘family-based’ interventions to improve dietary and/or physical activity behaviour outcomes. Neither self-efficacy nor intrinsic motivation can be directly observed, but the effects of them could be. Extracts from the original data are often included in the review itself so the reader can judge the plausibility of the inferences being made (Pawson, Citation2006a). In this way, the research process is transparent and can be held up to scientific scrutiny. Finally, data extraction is not a linear process and this stage may be repeated many times before it comes to be synthesised.

5. Synthesising the data

Each realist review begins with a hypothetical model made up of a collection of theories as to how, why, and in what circumstances a programme is thought to have worked and concludes with a revised model (Pawson, Citation2006a). In the synthesising stage, the data extracted from the literature is used to build Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) configurations to make inferences on the causal mechanism(s) at play and the context(s) that might trigger them. In creating these CMOs the initial programme theories are tested to see if they hold true and are refined accordingly. Depending on the nature of the project, data synthesis may be conducted individually (in consultation with project members) or in collaboration with the entire research team and stakeholders. The process of synthesising data taken from a diverse range of sources centres around a number of activities which are summarised and presented in . Once synthesised into CMO configurations the results are then re-written into research recommendations.

Table 5. Activities involved in the process of synthesising data from diverse sources.

6. Disseminating the findings

Research findings and recommendations should extend beyond academia to have a meaningful impact on policy makers and end users (Manville et al., Citation2015). To that end, stakeholders are consulted throughout a realist review. The initial consultation with stakeholders to refine the focus of the research makes it more likely that, when it comes to disseminating the findings, the results are relevant and meaningful to end users. For this reason, research findings should not be confined to academic journals and conference proceedings but should be delivered in forums that will attract the attention of key stakeholders and written in a language that is understood by them (Pawson, Citation2006a). For instance, social media platforms such as Twitter are increasingly being used to publish research findings in an attempt to increase academic impact and reach a wider and more diverse audience (Kunze et al., Citation2020)

Discussion

Realist research begins with the premise that a programme, however successful it may have been in one context, is unlikely to have the same result in another. For this reason, realist research makes programme theories the focus of their analysis rather than the programmes themselves. Programme theories refer to the ideas about how to bring about a particular change in behaviour: If we do X then Y will happen because of Z. A realist review starts with rough theories as to how an intervention is thought to work and tests those theories against the literature to see if they hold up. Instead of producing results that judge whether a particular programme has been successful or not, realist reviews provide information on why a programme works, who it works for, and in what particular context it worked. This line of enquiry is particularly useful for sport and exercise psychologists who are interested in understanding human behaviour and how it alters in certain situations to produce different outcomes. Instead of viewing human agency as a confounding variable, a realist review maintains that understanding complex social programmes is only possible by creating and testing theories to explain patterns of human behaviour. In other words, if the aim of the research is to understand why humans behave the way they do, then the method chosen to make this assessment needs to embrace complexity and not seek to control it. It is for this reason realist reviews should be encouraged in sports and exercise psychology research.

Realist research rejects the notion of universal laws or a ‘final truth’ because knowledge is transient and there is no such thing as a magic bullet. However, they do provide guidance to programme implementers in the form of middle-range theories. These theories are specific to the family of interventions under review but abstract enough that they can be transferred and applied in different settings. A realist review’s recommendations help to guide programme implementers on how the intervention is likely to fare in their particular location by signposting things to look out for, pitfalls to avoid and paths for success. Being able to apply this guidance to a programmer’s unique context helps to reduce the risk of programme failure as it moves from the trial phase into real-world implementation. For this reason, the recommendations made by a realist review have more impact and utility on programme developers.

The limited number of realist reviews in the sports and exercise psychology literature may partly be explained by early warnings that realist research is ‘not for the novice’ (Pawson et al., Citation2004, p. 38) and it is true to say that a realist review can be challenging. There is tension between the need for realist research to be systematic and transparent as well as creative (Booth et al., Citation2018). The researcher needs to rely on their intuition and sagacity (Pawson, 2006), the steps are iterative, and at times there can be a great deal of uncertainty as to which path to take (Punton et al., Citation2016). Having the courage to make creative inferences from the literature can be daunting (Tavroy & Timmermans, Citation2014). Furthermore, arbitrating between different programme theories, and looking for key pieces of information in literature that would traditionally be excluded from systematic reviews can be challenging (Pawson et al., Citation2004). A realist review does not offer the researcher the reassurance of checklists and steps to follow and whilst this flexibility might be liberating, a lack of specific procedure can also bring difficulties (Jagosh et al., Citation2013). In addition, like all literature reviews, a realist review can be limited by the quality of available data (Booth et al., Citation2018). In particular, there may be a lack of data with which to build programme theories (Pawson 2006). Finally, a realist review can be demanding both in terms of time and resources as it necessitates consultation with stakeholders as well as multiple iterations of theory building and testing (Blamey & Mackenzie, Citation2007).

Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997) did not set out to write a methodological guidebook for conducting realist research (Booth et al., Citation2020). Indeed, their approach has been described as a ‘way of thinking’ rather than a method (Westhorp Citation2014). However, since Pawson and Tilley’s publication, reporting guidelines have been introduced (Wong et al., Citation2013, Citation2014), books on ‘Doing Realist Research’ have been written (Emmel et al., Citation2018) and a methodological paper on how to conduct a realist literature search has been published (Booth et al., Citation2020). In addition, there is an increasing number of journal articles where authors critically reflect on their application of the realist approach to help guide others (Jagosh et al., Citation2013; Punton et al., Citation2016; Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2012; Shearn et al., Citation2017). Which is all to suggest that ‘novice’ researchers need not be so alarmed by warnings written decades ago. To our knowledge, however, there has not been a publication to date that has taken Pawson’s (Citation2006a) template for undertaking a realist review and displayed it as a conceptual graphic linking it to a hypothetical sports and exercise psychology study. By displaying the steps in this way, we have attempted to make realist research more accessible by helping readers visualise what a pragmatic approach to undertaking a realist review within the field of sport and exercise psychology might look like. However, it is important to note that the steps outlined are not new ways of doing things; they have been taken from Pawson (Citation2006a, p. 103) and applied in a hypothetical example. Furthermore, this graphic representation is not a recipe on how to do a realist review, and as others have shown, the steps may need adapting or condensing depending on the research needs.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to offer an introduction to realist review in the hope that researchers in sport and exercise psychology could see its utility and understand its application. As an adjunct to the text and to facilitate learning, we have included a diagrammatic representation of what a realist review in this field may look like. We have argued that the gaps left by systematic reviews and meta-analyses can be filled by the findings from a realist review. Furthermore, the ontological and theoretical underpinnings of realist research make it well suited to examining complex social programmes. This is important because, arguably, all behavioural change interventions in sport and exercise psychology are complex since they all involve human agency. While the realist review is not a panacea for all complexity there is no doubt that its application will provide valuable insights into the context, mechanisms, and outcomes inherent in any sport and exercise psychology programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agha, R., & Rosin, D. (2015). The Research Registry–answering the call to register every research study involving human participants. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 4(2), 95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.03.001

- Astbury, B., & Leeuw, F. L. (2010). Unpacking black boxes: Mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 31(3), 363–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214010371972

- Berg, R. C., & Nanavati, J. (2016). Realist review: Current practice and future prospects. Journal of Research Practice, 12(1), R1–R1.

- Bhaskar, R. (1975). A realist theory of science. Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. (2014). The possibility of naturalism: A philosophical critique of the contemporary human sciences (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Blamey, A., & Mackenzie, M. (2007). Theories of change and realistic evaluation. Evaluation, 13(4), 439–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389007082129

- Booth, A., Briscoe, S., & Wright, J. M. (2020). The “realist search”: A systematic scoping review of current practice and reporting. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(1), 14–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1386

- Booth, A., & Carroll, C. (2015). Systematic searching for theory to inform systematic reviews: Is it feasible? Is it desirable? Health Information & Libraries Journal, 32(3), 220–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12108

- Booth, A., Harris, J., Croot, E., Springett, J., Campbell, F., & Wilkins, E. (2013). Towards a methodology for cluster searching to provide conceptual and contextual “richness” for systematic reviews of complex interventions: Case study (CLUSTER). BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-118

- Booth, A., Wright, J., & Briscoe, S. (2018). Scoping and searching to support realist approaches. In N. Emmel, J. Greenhalgh, A. Manzano, M. Monaghan, & S. Dalkin (Eds.), Doing realist research (pp. 147–165). Sage.

- Booth, V., Harwood, R., Hancox, J. E., Hood-Moore, V., Masud, T., & Logan, P. (2019). Motivation as a mechanism underpinning exercise-based falls prevention programmes for older adults with cognitive impairment: A realist review. BMJ Open, 9(6), e024982. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024982

- Brennan, N., Bryce, M., Pearson, M., Wong, G., Cooper, C., & Archer, J. (2014). Understanding how appraisal of doctors produces its effects: A realist review protocol. BMJ Open, 4(6), e005466–e005466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005466

- Brighton, L. J., Evans, C. J., Man, W. D., & Maddocks, M. (2020). Improving exercise-based interventions for people living with both COPD and frailty: A realist review. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Volume 15, 841–855. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.s238680

- Brown, H. E., Atkin, A. J., Panter, J., Wong, G., Chinapaw, M. J. M., & van Sluijs, E. M. F. (2017). Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: A systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obesity Reviews, 18(4), 491–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12493

- Carr, S. (2009). Implications of attachment theory for sport and physical activity research: Conceptual links with achievement goal and peer-relationship models. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17509840902759173

- Chen, H. T. (2015). Practical program evaluation: Theory-driven evaluation and the integrated evaluation perspective. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Cooper, C., Lhussier, M., & Carr, S. (2020). Blurring the boundaries between synthesis and evaluation. A customized realist evaluative synthesis into adolescent risk behavior prevention. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(3), 457–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1407

- Coughlan, E. K., Williams, A. M., & Ford, P. R. (2019). Lessons from the experts: The effect of a cognitive processing intervention during deliberate practice of a complex task. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 41(5), 298–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2017-0363

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 337(7676), a1655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2019). CASP systematic review checklist. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Dalkin, S. M., Greenhalgh, J., Jones, D., Cunningham, B., & Lhussier, M. (2015). What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x

- Davidoff, F., Dixon-Woods, M., Leviton, L., & Michie, S. (2015). Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Quality & Safety, 24(3), 228–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627

- Emmel, N. (2013). Sampling and choosing cases in qualitative research: A realist approach. Sage.

- Emmel, N., Greenhalgh, J., Manzano, A., Monaghan, M., & Dalkin, S. (2018). Doing realist research. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Enright, G., Allman-Farinelli, M., & Redfern, J. (2020). Effectiveness of family-based behavior change interventions on obesity-related behavior change in children: A realist synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4099. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114099

- EPPI Centre. (2019). What is a systematic review? http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=67

- Fox, D. M. (2017). Evidence and health policy: Using and regulating systematic reviews. American Journal of Public Health, 107(1), 88–92. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303485

- Gagliardi, A. R., Faulkner, G., Ciliska, D., & Hicks, A. (2015). Corrigendum to “factors contributing to the effectiveness of physical activity counselling in primary care: A realist systematic review”. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(7), 923. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.04.001. [Patient Educ. Couns. 98 (4) (412–419].

- Gledhill, A., & Forsdyke, D. (2021). Realist synthesis in sport and exercise medicine: “time to get real.”. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 102073–102073. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102073

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Greenhalgh, J., & Manzano, A. (2021). Understanding “context” in realist evaluation and synthesis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1918484

- Greenhalgh, T., Howick, J., & Maskrey, N. (2014). Evidence based medicine: A movement in crisis? BMJ, 348(jun13 4), g3725–g3725. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3725

- Harris, K. (2018). Building sport for development practitioners’ capacity for undertaking monitoring and evaluation – reflections on a training programme building capacity in realist evaluation. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(4), 795–814. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2018.1442870

- Horn, R. E. (2001, July 16th). Knowledge mapping for complex social messes. [Paper presentation]. David and Lucile Packard Foundation, California, USA. https://faculty.washington.edu/farkas/TC510-Fall2011/HornKnowledgeMapping.pdf

- Jagosh, J. (2019). Realist synthesis for public health: Building an ontologically deep understanding of how programs work, for whom, and in which contexts. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 361–372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044451

- Jagosh, J. (2020). Retroductive theorizing in Pawson and Tilley’s applied scientific realism. Journal of Critical Realism, 19(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2020.1723301

- Jagosh, J., Pluye, P., Wong, G., Cargo, M., Salsberg, J., Bush, P. L., Herbert, C. P., Green, L. W., Greenhalgh, T., & Macaulay, A. C. (2013). Critical reflections on realist review: Insights from customizing the methodology to the needs of participatory research assessment. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1099

- Kunze, K. N., Polce, E. M., Vadhera, A., Williams, B. T., Nwachukwu, B. U., Nho, S. J., & Chahla, J. (2020). What Is the predictive ability and academic impact of the Altmetrics score and social media attention? The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(5), 1056–1062. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546520903703

- Lehe, R. T. (1998). Realism and reality. Journal of Philosophical Research, 23, 219–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5840/jpr_1998_19

- Leone, L., & Pesce, C. (2017). From delivery to adoption of physical activity guidelines: Realist synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(10), 1193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101193

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Maidment, I., Booth, A., Mullan, J., McKeown, J., Bailey, S., & Wong, G. (2017). Developing a framework for a novel multi-disciplinary, multi-agency intervention(s), to improve medication management in community-dwelling older people on complex medication regimens (MEMORABLE)––a realist synthesis. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0528-1

- Manville, C., Jones, M. M., Henham, M. L., Castle-Clarke, S., Frearson, M., Gunashekar, S., & Grant, J. (2015). Preparing impact submissions for REF 2014: An evaluation. RAND Europe.

- Marchal, B., Kegels, K., & Van Belle, S. (2018). Theory and realist methods. In N. Emmel, J. Greenhalgh, A. Manzano, M. Monaghan, & S. Dalkin (Eds.), Doing realist research (pp. 79–91). Sage.

- Marchal, B., van Belle, S., van Olmen, J., Hoerée, T., & Kegels, G. (2012). Is realist evaluation keeping its promise? A review of published empirical studies in the field of health systems research. Evaluation, 18(2), 192–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012442444

- Mason, J., Oatley, C., Harris, K., & Ryan, L. (2021). How and why does local area coordination work for people in different contexts? Methodological Innovations, 14(1), 205979912098538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799120985381

- Merton, R. K. (1967). On theoretical sociology: five essays, old and new (No. HM51 M392).

- Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 350(mar19 6), h1258–h1258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Noyes, J., Hendry, M., Booth, A., Chandler, J., Lewin, S., Glenton, C., & Garside, R. (2016). Current use was established and Cochrane guidance on selection of social theories for systematic reviews of complex interventions was developed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75, 78–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.009

- Ntoumanis, N. (2001). A self-determination approach to the understanding of motivation in physical education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158497

- Oliver, K., Innvar, S., Lorenc, T., Woodman, J., & Thomas, J. (2014). A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2

- Pawson, R. (2002). Evidence-based policy: The promise of `realist synthesis’. Evaluation, 8(3), 340–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/135638902401462448

- Pawson, R. (2006a). Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective. Sage.

- Pawson, R. (2006b). Digging for nuggets: How “Bad” research Can yield “good” evidence. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 9(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570600595314

- Pawson, R. (2013). The Science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. United Kingdom Sage Publications Ltd.

- Pawson, R. (2018). Realist memorabilia. In N. Emmel, J. Greenhalgh, A. Manzano, M. Monaghan, & S. Dalkin (Eds.), Doing realist research (pp. 203–220). Sage.

- Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2004). Realist synthesis: An introduction (pp. 1–55). Manchester: ESRC Research Methods Programme, University of Manchester.

- Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2005). Realist review–a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10(Suppl 1), 21–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1258/1355819054308530

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. Sage.

- Pearson, M., Chilton, R., Woods, H. B., Wyatt, K., Ford, T., Abraham, C., & Anderson, R. (2012). Implementing health promotion in schools: Protocol for a realist systematic review of research and experience in the United Kingdom (UK). Systematic Reviews, 1(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-48

- Punton, M., Vogel, I., & Lloyd, R. (2016). Reflections from a realist evaluation in progress: Scaling ladders and stitching theory. Opendocs.ids.ac.uk. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/11254

- RAMESES II Project. (2017a). Philosophies and evaluation design: The RAMESES II Project. https://www.ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Philosophies_and_evaluation_design.pdf

- RAMESES II Project. (2017b). Developing realist programme theories: The RAMESES II Project. https://ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Developing_realist_programme_theories.pdf

- RAMESES II Project. (2017c). Protocols and realist evaluation: The RAMESES II Project. https://ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Protocols_and_realist_evaluation.pdf

- Rycroft-Malone, J., McCormack, B., Hutchinson, A. M., DeCorby, K., Bucknall, T. K., Kent, B., Schultz, A., Snelgrove-Clarke, E., Stetler, C. B., Titler, M., Wallin, L., & Wilson, V. (2012). Realist synthesis: Illustrating the method for implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-33

- Shearn, K., Allmark, P., Piercy, H., & Hirst, J. (2017). Building realist program theory for large complex and messy interventions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691774179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917741796

- Such, E., Burton, H., Copeland, R. J., Davies, R., Goyder, E., Jeanes, R., Kesterton, S., Mackenzie, K., & Magee, J. (2019). Developing a theory-driven framework for a football intervention for men with severe, moderate or enduring mental health problems: A participatory realist synthesis. Journal of Mental Health, 29(3), 277–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1581339

- Tavory, I., & Timmermans, S. (2014). Abductive analysis: Theorizing qualitative research. The University of Chicago Press.

- Thomas, A., Lubarsky, S., Durning, S. J., & Young, M. E. (2017). Knowledge Syntheses in Medical education. Academic Medicine, 92(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001452

- Tod, D. (2019). Conducting systematic reviews in sport, exercise, and physical activity. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Westhorp, G. (2013). Developing complexity-consistent theory in a realist investigation. Evaluation, 19(4), 364–382. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013505042

- Westhorp, G. (2014). Realist impact evaluation: An introduction, 1–12. Overseas Development Institute. https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/9138.pdf

- Wong, G. (2018). Data gathering in realist reviews: Looking for needles in haystacks. In N. Emmel, J. Greenhalgh, A. Manzano, M. Monaghan, & S. Dalkin (Eds.), Doing realist research (pp. 131–145). Sage.

- Wong, G., Greenhalgh, T., Westhorp, G., Buckingham, J., & Pawson, R. (2013). RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. BMC Medicine, 11(1), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-21

- Wong, G., Greenhalgh, T., Westhorp, G., & Pawson, R. (2014). Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: The RAMESES (realist And meta-narrative evidence syntheses–evolving standards) project. Health Services and Delivery Research, 2(30). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr02300

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki. JAMA, 310(20), 2191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053