ABSTRACT

This systematic scoping review synthesises and appraises applied interventions, consensus/position statements, and grey literature regarding strategies to support athlete mental health and draws necessary connections across these documents. This review is informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). SPORTDiscus, PsycArticles, PsycINFO and SCOPUS were used to identify documents, alongside a search of all UK-based Olympic sport governing body websites. Thirty-seven documents met the review criteria. There were twenty-two intervention studies (including four case studies), nine position or consensus statements, and six grey literature documents (e.g. athlete mental health policies). Most interventions resulted in moderate or non-significant findings. Although position/consensus statements provide recommendations, they lack detail and primarily address research and organisational strategy rather than applied practice. Some grey literature recommendations are coherent with previous research, however, there are a lack of mental health policies produced by national governing bodies within elite sport. This review provides a comprehensive overview of athlete mental health literature and draws necessary connections across these different types of documents. Interventions with improved methodology (e.g. larger sample sizes), and more detailed recommendations within grey literature are required to inform applied efforts, recommendations, and future research.

Introduction

Although the psychological benefits of recreational sport are well-documented (Brawn et al., Citation2015), elite sport can have negative consequences for athlete mental health (Castaldelli-Maia et al., Citation2019). Keyes’ (Citation2005) two-continuum model of mental health posits two related, but distinct dimensions – the presence or absence of mental health, and the presence or absence of mental illness. This model acknowledges flourishing or languishing mental health alongside the presence of absence of mental illness (Keyes, Citation2005). For example, an athlete could experience both positive mental health (i.e. flourishing) and symptoms of mental illness. Alternatively, an athlete may be experiencing low levels of mental health (i.e. languishing), while not being considered to have mental illness. Prevalence studies suggest athletes are as likely – and sometimes more likely – than the general population to experience mental illness symptoms (e.g. Martinsen & Sundgot-Borgen, Citation2013; Yang et al., Citation2007) and in some cases (e.g. eating disorders) clinical diagnoses (e.g. Byrne & McLean, Citation2002; Sundgot-Borgen & Torstveit, Citation2004; Torstveit et al., Citation2008). High-performance sport poses various risk factors which may encourage the development and/or maintenance of mental illness in athletes (e.g. Küttel & Larsen, Citation2019), for example competitive stressors such as performance expectation, organisational stressors such as extensive travel, and financial issues (Fletcher & Arnold, Citation2011). It must also be considered that athletes may have chosen to engage with sport as a means of coping with a disorder, or that athletes may have psychiatric illness precipitated or worsened by sport itself (Reardon & Factor, Citation2010). Consequently, elite athletes may be at peak risk of mental illness onset throughout the height of their competitive years (Gulliver et al., Citation2012).

Perhaps in part due to several elite athletes publicly sharing their experiences of mental health challenges (Parrott et al., Citation2021), academic interest in athlete mental health has grown exponentially in recent years. In addition to prevalence (e.g. Åkesdotter et al., Citation2020) and risk factors (e.g. Küttel & Larsen, Citation2019), research has explored a range of mental health topics, including interventions and treatment (e.g. Becker et al., Citation2012), mental health awareness (e.g. Bapat et al., Citation2009), and help-seeking behaviours (e.g. Gulliver et al., Citation2012). Consequently, there is a substantial body of literature offering applied recommendations on managing athlete mental health. Examples include intervention studies, position and consensus statements, and grey literature (e.g. mental health policies set out by sporting organisations). Intervention studies focus on the prevention and treatment of mental illnesses and mental health challenges. Position and consensus statements offer recommendations for sporting organisations regarding preventing and managing mental illness and promoting and protecting athlete mental health. Finally, grey literature presents policies, frameworks, or recommendations for athlete mental health support (e.g. Grey-Thompson, Citation2017). These documents offer important conceptual and applied insights on prevention, treatment and management of mental illness, promotion of mental health, and providing athlete mental health support. Although these documents add to a growing understanding of applied mental health support, there has yet to be a critical synthesis evaluating their contribution.

The need to connect insights from applied research to best practice in the real world is a well-known academic challenge. One approach to bridging the research-practice gap has been to develop resources such as consensus and position statements that offer a range of recommendations and guidance. Such a range of sources provides a suite of options when managing athlete mental health, but this may be challenging to navigate for organisations and practitioners, causing more confusion than clarity (Vella et al., Citation2021). This confusion may have a detrimental impact on the ability of those in sport to effectively assess, select, and implement appropriate interventions, resulting in potentially less impactful support for athletes. Therefore, synthesising, and appraising knowledge surrounding athlete mental health support (i.e. intervention studies, position and consensus statements, and grey literature such as policies) may offer more comprehensive guidance to those working within sport.

Despite a small number of reviews of athlete mental health research (e.g. Breslin et al., Citation2017; Liddle et al., Citation2017; Rice et al., Citation2016; Vella et al., Citation2021), no study to date has included grey literature alongside peer-reviewed empirical research. As grey literature is often more accessible than academic literature to those in the applied sport environment, key stakeholders (e.g. performance directors and sport psychologists) may draw upon documents such as sporting organisations’ mental health policies to inform their approach to athlete mental health. Therefore, it is crucial that such grey literature is included in reviews of the area, and that all types of documents be appraised to establish their contribution to athlete mental health knowledge and strategies.

This review aims to build on previous reviews by synthesising and appraising athlete mental health literature including intervention studies, consensus statements, position statements, and grey literature, offering the most comprehensive applied review to date. Collective analysis and evaluation of these documents, specifically involving the novel inclusion of grey literature, may help to create overarching connections and insights across existing athlete mental health literature. This insight is not only necessary in presenting the current knowledge of athlete mental health support, but also in closing the gaps between peer-reviewed literature, policy, and applied practice. We ask the following questions: what are the existing applied interventions, recommendations, and policies related to athlete mental health support within competitive sport?; and what is the quality of these documents?

Method

Protocol and registration

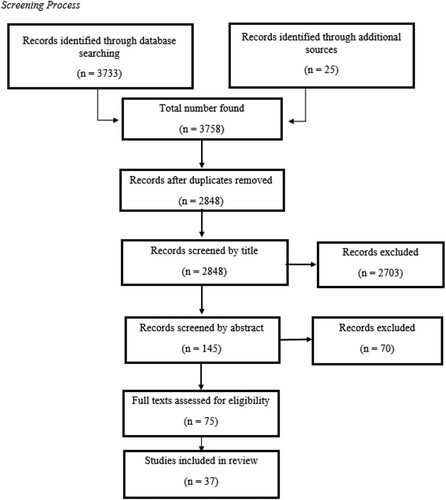

A literature search was conducted to identify relevant published intervention studies, position and consensus statements, and grey literature focusing on applied strategies to support the mental health of competitive athletes. Methodologically, this review is informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria involved studies published in peer-reviewed journals, peer-reviewed consensus and position statements, mental health interventions in sport (including case studies) and grey literature (e.g. sporting organisations’ mental health policies) relating to the mental health of competitive athletes. Interventions were selected based on a relevant mental health outcome (e.g. preventing and treating eating disorders [e.g. Buchholz et al., Citation2008; Stranberg et al., Citation2020]). Grey literature was selected based on the presence of applied recommendations to support athlete mental health. The study reviewed UK-based Olympic and Paralympic sport national governing body policies due to the scope of the review, however, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Safeguarding Toolkit (2017) was also included as the IOC presides over UK-based Olympic and Paralympic national governing bodies. All reviewed documents relate to structured competitive sport, therefore including athletes competing at national and international level, NCAA college athletes, and some high-school athletes. There was no cut off year for the search.

Information sources & search strategy

Four databases were searched – SPORTDiscus, PsycArticles, PsycINFO, and SCOPUS. The search protocol was initiated in May 2022. Three groups of associated search terms were used in combination to examine each electronic database within the title, abstract, and key words. The three broad groupings used for search terms were ‘mental health and illness’, ‘sport’, and ‘interventions’. Synonymous terms (e.g. ‘elite athlete’, ‘competitive’ ‘treatment’, and ‘eating disorder’) were nested within these categories, using a Boolean search protocol to combine terms. These search strings were drafted and discussed by the research team who also consulted an academic librarian. The full list of search terms used in the data collection is available from the first author on request. The results of each search were imported into Rayyan, an online programme designed for managing systematic reviews. This process was undertaken for each of the four databases, with duplicates being flagged by Rayyan and manually removed by the researcher. These search results were supplemented with a manual search of reference lists from included articles. Additionally, a manual search of all UK-based Olympic and Paralympic sport websites was undertaken to source athlete mental health policies.

Document screening and selection

Articles were evaluated for inclusion by the first author based on their titles, then abstracts. The remaining articles were reviewed in full by the first and second authors (see ). The selection of grey literature was based on strategies, recommendations, and policies regarding athlete mental health support.

Data extraction

Data extraction coding guides were created for intervention studies, position and consensus statements and grey literature. The guide for intervention studies detailed the following areas: title, authors, participants, intervention type, date of publication, data collection, findings, recommendations, and conclusions. The data extraction guide for position and consensus statements included title, authors, date of publication, aims of the document, method (of arriving at a consensus), strategies and recommendations presented, and conclusions. The guide for grey literature detailed the title, authors, date of publication, aims of the document, types of strategies or recommendations suggested, and conclusions. These areas were chosen based on their relevance to the systematic scoping review and the types of documents included. Data extraction was completed by the first and second authors. The extraction results were then synthesised and critically appraised by the first author, with the second and third authors acting as critical friends.

Results

A total of 37 documents were identified, including 22 intervention studies, 9 consensus, position, or expert statements, and 6 grey literature documents. Information including study design, sample size, and intervention details, along with key findings of the included documents was extracted and is presented in , , and .

Table 1. Reviewed intervention studies.

Table 2. Reviewed consensus, position & expert statements.

Table 3. Reviewed grey literature.

Aims of intervention studies

The intervention studies reviewed presented a range of aims including prevention of mental illness including preventing risk behaviours such as binge drinking and illicit drug use (Donohue et al., Citation2015) and prevention of eating disorders (Becker et al., Citation2012; Buchholz et al., Citation2008); treatment for mental illness including treatment for eating disorders (Smith & Petrie, Citation2008; Stranberg et al., Citation2020), and decreasing anxiety (Fogaca et al., Citation2020; Mohammed et al., Citation2018); and improving mental health literacy including increasing competence in mental health self-management (Shannon et al., Citation2019) and increasing help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and behaviours (Gulliver et al., Citation2012).

Participants

Participant numbers varied from 1 to 969 with a total of 3963 participants across all studies. Based on studies that reported sex, female participants outnumbered male participants 3–1. Of the 22 interventions, 11 recruited NCAA student athletes, 2 recruited non-NCAA student athletes, 4 sampled non-student athletes, 1 sampled athletes and non-athletes, and 1 study recruited athletes, parents, and coaches. 3 further interventions recruited coaches. Two studies required a clinical diagnosis as part of the inclusion criteria (i.e. Donohue et al., Citation2015; Stranberg et al., Citation2020).

Characteristics of interventions

Interventions deployed a range of strategies for prevention of mental illness including coping skills (Fogaca et al., Citation2020) and adapted family therapy (Donohue et al., Citation2015); treatment for mental illness including educational workshops focused on eating disorders (Stranberg et al., Citation2020), strengths-based cognitive behavioural sessions (e.g. Gabana, Citation2017), cognitive behavioural therapy (e.g. Gustafsson et al., Citation2017), and mindfulness-based stress reduction (e.g. Mohammed et al., Citation2018); and improving mental health literacy including educational workshops to increase mental health awareness (e.g. Breslin et al., Citation2019; Fogaca et al., Citation2020) and ability to identify signs of mental illness (i.e. anxiety and depression; Fogaca et al., Citation2020). Some studies provided explicit reference to an underpinning theory of behaviour change which guided their intervention: the Theory of Planned Behaviour Change (i.e. Breslin et al., Citation2017); the Integrated Behaviour Change Model (i.e. Breslin et al., Citation2019); and Self-Determination Theory (i.e. Shannon et al., Citation2019).

Research design

Of the 22 intervention studies identified, 11 conducted randomised controlled trials, 3 undertook non-randomised controlled trials, 2 were pre–post tests, and 2 used quasi-experimental designs. Quantitative methods were adopted by 16 of these interventions and 2 used mixed methods (see ). Finally, 4 of these interventions were case studies. Outcome measures included attitudes and intentions regarding mental health (Gulliver et al., Citation2012); mental health self-management and the motivation to self-manage (Becker et al., Citation2012; Breslin et al., Citation2019; Buchholz et al., Citation2008; Elliot et al., Citation2004, Citation2008; Martinsen & Sundgot-Borgen, Citation2013; Smith & Petrie, Citation2008; Stranberg et al., Citation2020), positive and negative affect (Becker et al., Citation2012), coping skills, appraisal of stress and emotion regulation (Fogaca et al., Citation2020), anxiety and depression (Donohue et al., Citation2018; Fogaca et al., Citation2020; Mohammed et al., Citation2018) and the frequency of mindful states in everyday life (Gross et al., Citation2018; Mohammed et al., Citation2018; Shannon et al., Citation2019). There were 53 measures used across the reviewed interventions, with 9 of these measures being used in multiple intervention studies (please see the supplementary file for a list of all measures used). Finally, two interventions followed up with qualitative data collection to further explore participants’ and/or intervention facilitators’ experiences.

Intervention facilitators

Although some studies used accredited practitioners such as sport psychologists or nutritionists (e.g. Stranberg et al., Citation2020), others used doctoral students (see Gross et al., Citation2018) or students supervised by qualified psychologists (e.g. Becker et al., Citation2012). Some interventions were delivered through automated websites and applications (e.g. Gulliver et al., Citation2012), and some interventions did not specify the background or experience of facilitators.

Intervention findings and recommendations

Substance abuse

The Optimum Performance Program in Sports (TOPPS; Donohue et al., Citation2015) aimed to reduce substance use. Post-intervention results suggest no change to frequency of binge drinking each month, with illicit drug use decreasing somewhat during the intervention. At follow-up, binge drinking remained at the same frequency of 1 day per month, whereas illicit drug use decreased substantially during the first 3 months of follow-up, with a 76% decrease in illicit drug use from baseline at 1-month follow up, and an 87% decrease from baseline observed at 3-month follow up.

Eating disorders

The ATHENA interventions were designed to deter unhealthy body shaping behaviours in female high school athletes – including use of steroids, diet pills and creatine. Elliot et al. (Citation2004; Citation2008) demonstrated that beneficial outcomes increased over time, and that the intervention had sustained positive effects on harm reduction and dietary behaviour. The Walden GOALS intervention (Stranberg et al., Citation2020) aimed to add to the literature on treatment outcomes for athlete eating disorders. Findings demonstrated that athlete-specific eating disorder treatment has positive, measurable effects on eating disorder behavioural risks, eating pathology, and eating competence.

BodySense (Buchholz et al., Citation2008) used psychoeducation as a prevention programme designed to reduce pressures to be thin in sport, and to promote positive body image and eating behaviours in young female athletes. Findings suggested a modest reduction in pressure to be thin, but no significant changes to body esteem when eating attitudes and athletes’ recognition and acceptance of socially sanctioned standards of appearance were measured. Becker et al. (Citation2012) conducted a randomised controlled trial of 2 peer-led psychoeducation interventions which were modified to address the unique needs of female athletes. Findings suggested that both interventions reduced thin ideal internalisation, dietary restraint, bulimic pathology, shape and weight concern, and negative affect at 1 year. There was also an unexpected increase in students seeking medical consultations regarding the female athlete triad. This suggests that the interventions reduced eating disorder symptomatology and encouraged help-seeking behaviours.

Finally, Smith and Petrie (Citation2008) compared the effectiveness of a cognitive-dissonance based intervention to two alternatives – a psychoeducation-based healthy weight and waiting-list control – to determine their relative effectiveness in reducing body dissatisfaction, negative affect, dietary restriction, and internalisation of the sociocultural ideal. A secondary aim of the intervention was to reduce negative affect. The cognitive-dissonance intervention provided some positive effects with respect to decreases in sadness/depression and in internalisation of a physically fit and in-shape body type and increases in body satisfaction. With the exception of Becker et al. (Citation2012), intervention findings demonstrate moderate impact of interventions on eating disorder treatment and prevention.

Self-management of mental health

The SOMI intervention (Breslin et al., Citation2019) used psychoeducational strategies such as mindfulness interventions, breathing exercises, group discussions related to managing pressure, support for autonomous problem-solving, and vignettes. Findings suggest that the intervention increased intentions to self-manage mental health, through improved autonomous and controlled motivation, and attitudes towards managing mental health. This was the first study to incorporate the Integrated Behaviour Change Model into an athlete mental health intervention. This study demonstrates that programmes such as SOMI can improve factors such as perceived control, attitudes, and self-management intentions in relation to mental health, and that these factors could offer a preventative measure against common stressors that athletes face.

Mental health literacy and help-seeking behaviours

Gulliver et al. (Citation2012) conducted a randomised control trial to test the feasibility and efficacy of three internet-based interventions designed to increase mental health help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and behaviour in young elite athletes compared with a control condition. Findings suggested increased depression and anxiety literacy compared to the control group, in addition to a reduction in depression and anxiety stigma. Despite this, no intervention groups resulted in a significant increase in help-seeking attitudes, intentions, or behaviour relative to the control group, with participants in the ‘help-seeking list’ intervention group demonstrating no significant improvement in depression or anxiety literacy or decreased stigmatising attitudes.

Coping with anxiety

Both Mohammed et al. (Citation2018) and Fogaca et al. (Citation2020) focused on increasing coping skills to manage anxiety. Fogaca et al. (Citation2020) approached this through mental skills training with the peripheral goal of improving performance. Athletic coping skills and anxiety significantly improved compared to that of the control group, however, there was no improvement related to symptoms of depression. The novelty of this intervention was teaching mental skills while emphasising how athletes could use these skills to manage both sports and life stressors. Mohammed et al. (Citation2018) aimed to investigate the role of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in reducing the perception of pain and decreasing anxiety and stress, as well as increasing pain tolerance and mindful awareness (i.e. understanding how to pay attention, live in the present moment, and increase body awareness) in injured athletes. The intervention group experienced an increase in pain tolerance and an increase in mindful awareness. Findings suggested a notable decrease in stress and anxiety across the sessions, however, no significant changes were observed. No benefit to mood was demonstrated.

Mohammed et al. (Citation2018) also investigated the role of mindfulness-based stress reduction on various aspects of athlete mental health. In relation to increased mindfulness as an outcome, participants demonstrated increased mindful awareness. Competence and mindfulness levels appeared to reduce stress, which then indirectly impacted well-being. Shannon et al. (Citation2019) also studied the effect of a mindfulness intervention in promoting well-being, reducing stress, and increasing competence in mental health self-management. Findings suggested mindfulness was not directly enhanced by the intervention, resulting in no indirect effects on competence, stress, and well-being. It was also suggested that competence and mindful awareness impacted stress levels, with competence, mindful awareness and stress ultimately impacting well-being. These studies demonstrate that competence and mindful awareness decrease stress levels, which in turn impacts athlete well-being. In summary, these findings suggest that while athlete mental health interventions are increasing in number, they demonstrate merely moderate impact or non-significant results. Therefore, current intervention literature cannot adequately inform intervention development. To address this issue, more methodologically rigorous intervention studies are required.

Aim of consensus and position statements

Although consensus and position statements discuss various aspects of athlete mental health, the broad aim of these documents was to provide organisations and practitioners with best practice guidelines and recommendations in relation to managing athlete mental health.

Position and consensus statement method

The method used to arrive at a consensus differed from statement to statement. Some statements did not detail their method for achieving consensus (e.g. Moesch et al., Citation2018; Schinke et al., Citation2018). Each statement was derived from a meeting of experts in sport psychology from a range of international sporting organisations. Some statements detailed how the experts formed their recommendations, which ranged from working in sub-groups based on expertise (e.g. Chang et al., Citation2020; Henriksen et al., Citation2020) to conducting a systematic review of related topic areas, identifying themes, and presenting recommendations (Reardon et al., Citation2019). Van Slingerland et al. (Citation2019) also engaged a multidisciplinary group of professionals across sport science, medicine, health, psychology, and counselling to undertake Participatory Action Research to assess availability and effectiveness of service for high performance athletes.

Position and consensus statement findings and recommendations

Contextualising mental health within the elite sport setting was deemed critical to ensuring that practitioners have a thorough understanding of the sporting world and its complexities when supporting athletes (e.g. Henriksen et al., Citation2020; Moesch et al., Citation2018; Van Slingerland et al., Citation2019). Individual context such as race, gender, religion, and ethnicity; environmental context such as national, organisational, political, and sport-specific; and developmental context such as age, career phase, and transition were also highlighted as key considerations when defining mental health in elite sport (e.g. Henriksen et al., Citation2020).

The education of key stakeholders within the sporting environment (e.g. coaches, parents, sport science staff) has been viewed as essential to effectively support athlete mental health (Purcell et al., Citation2019), including appropriate implementation of policies, and crucially, ensuring staff awareness of such policies (e.g. Van Slingerland et al., Citation2019). Challenging stigma was discussed as an important goal of educating stakeholders to create a culture that values enhancing the mental health of all stakeholders and encourages help-seeking behaviours (e.g. Moesch et al., Citation2018; Purcell et al., Citation2019). These measures should then encourage clear support pathways and signposting by institutions and stakeholders to inform athletes of the help available and how it can be accessed (e.g. Moesch et al., Citation2018).

Recommendations suggested that sporting organisations should consider factors such as culture; governance; programme entry and exit; selection, deselection, and appeals; and providing support during injury and the return to training when looking to support athlete mental health (e.g. Chang et al., Citation2020; Schinke et al., Citation2018). These factors were identified as challenging points within an athlete’s career, and therefore, purposeful consideration surrounding the support structure for athletes at these times has been cited as crucial to managing their mental health. By factoring in these aspects of the competitive sport experience, a psychologically informed (see Breedvelt, Citation2016; Phipps et al., Citation2017) and psychologically safe (see Vella et al., Citation2021) environment can be created which nourishes athlete mental health (e.g. Henriksen et al., Citation2020). Recommendations for staff and applied practitioners noted the importance of regular mental health screening for athletes (e.g. Purcell et al., Citation2019); regular multi-disciplinary athlete support (e.g. Van Slingerland et al., Citation2019); prevention, early intervention, and specialist mental health care (e.g. Purcell et al., Citation2019); and a sport-specific approach in detecting and treating mental illness in athletes (e.g. Moesch et al., Citation2018).

Finally, researchers in athlete mental health were encouraged to provide guidance on the selection of appropriate theories, models, and constructs to inform intervention design, implementation, and evaluation (Breslin et al., Citation2019), and develop sport-specific screening tools to screen both athletes and organisations for risk and protective factors (e.g. Henriksen et al., Citation2020). In addition, Gorczynski et al. (Citation2019) recommended researchers improve their methods of investigating mental health, evaluating mental health literacy interventions, and translating such interventions for widespread practice to enable improved mental health outcomes.

Aims of grey literature

The grey literature included in this review consists of the duty of care in sport review (Grey-Thompson, Citation2017), the Mental Health and Elite Sport Action Plan (UK Government, Citation2018), the UK Sport Culture Health Check (UK Sport, Citation2018), the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Safeguarding Toolkit (IOC, Citation2017), and two national governing body (NGB) policy documents by GB Judo and GB Canoeing. The aim of these documents included outlining key considerations and challenges for research and applied practice in mental health and highlighting the duty of care toward athletes in sport.

Method of grey literature

Grey literature documents were created in a variety of ways, with the duty of care review (Grey-Thompson, Citation2017) making a call for evidence from sporting organisations and the general public asking them what works well, and what could be improved in both grassroots and elite sport systems. The topics discussed included: entering and leaving talent pathways; prevention and management of injuries; mental health; representation of athletes’ interests; formal education; and safeguarding. The IOC Safeguarding Toolkit (IOC, Citation2017) was developed by representatives from international federations, national Olympic committees, the IOC prevention of harassment and abuse in sport working group, and with experts and organisations both inside and outside the Olympic Movement. The Mental Health and Elite Sport Action Plan (UK Government, Citation2018) was derived through two roundtable discussions chaired by the Minister for Sport. The UK Sport Culture Health Check (UK Sport, Citation2018) involved an independent survey of stakeholders in sport, followed by a report created by a consultancy company, which was then circulated across all world-class programmes within UK Sport. Contrastingly, there is no information regarding the creation and dissemination of national governing body policies (e.g. British Canoeing, Citation2018; GB Judo, Citation2018).

Grey literature findings and recommendations

The key findings and recommendations from the grey literature are largely aligned with position and consensus statements regarding athlete mental health support. Recommendations centred on challenging transitions across an athlete’s career such as programme entry, selection, deselection, injury, and retirement; educating key stakeholders to encourage appropriate athlete support and challenge stigma; and providing regular and multi-disciplinary athlete support throughout their careers. Noteworthy recommendations which differed from suggestions in previous grey literature and academic literature included the creation of a sport ombudsman and establishing board members responsible for duty of care in national governing bodies (see Grey-Thompson, Citation2017). In summary, while grey literature in the area is largely aligned with recommendations within peer-reviewed literature, more policies and grey literature focusing on athlete mental health are needed, with recommendations and guidelines presented in sufficient detail to inform practice.

Discussion

Having drawn connections across key athlete mental health documents, the following section will discuss and appraise the key findings of the current review, and present recommendations for progress in the area.

Participants

Across the intervention studies, female participants outnumbered male participants by 3 to 1, primarily a consequence of disordered eating interventions almost exclusively targeting women. Although there is heightened female prevalence regarding eating disorders, the suggestion that it is a disease which only affects women can create stigma and prevent disclosure by male athletes (Baum, Citation2006; Papathomas, Citation2014; Petrie et al., Citation2008). Therefore, it is important to recognise the impact of eating disorders within the male population and create effective interventions accordingly.

Intervention measures

Few of the measures used in the reviewed interventions were designed for the sporting context, with findings offering limited insight into the effectiveness of interventions designed to promote mental health, prevent, or treat mental illness, and improve mental health literacy within sport. Various inventories were also used to measure the same factor, presenting a challenge when comparing findings and establishing intervention effectiveness (Poucher et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, standardised reporting of mental health outcomes in sport should be encouraged alongside the use of sport-specific inventories which account for the sporting context. These steps would inform practitioners’ choice of intervention, enabling them to effectively measure their impact.

Intervention facilitators

The qualifications and experience of intervention facilitators varied substantially, with some studies neglecting to mention who delivered the intervention, suggesting a lack of consideration. Ensuring competence of intervention facilitators is crucial, therefore their suitability should be carefully considered. Type of intervention, intervention recipient(s), severity of situation, and skills of the intervention facilitator must be acknowledged. Intervention studies should clearly articulate who is delivering the intervention, and the key considerations when selecting these individuals. This will provide clarity for future studies and those working in applied settings.

When contemplating how best to support athlete mental health, the roles of various key stakeholders (e.g. coaching and support staff) should be examined. Moving away from reliance on a sport psychologist – who may not always be present – and upskilling other stakeholders (e.g. coaches) facilitates a more collaborative approach to athlete mental health support (see McCalla & Fitzpatrick, Citation2016). For example, coaches’ ability to observe athletes regularly positions them to recognise changes to an athlete’s mental health or early signs of mental illness and refer the athlete to appropriate support. The coach-athlete relationship can also position coaches to encourage help-seeking behaviours in athletes (Mazzer & Rickwood, Citation2015). However, some coaches do not feel adequately educated on signs and symptoms of mental illness and relevant referral strategies to support athlete mental health (Ferguson et al., Citation2019). Therefore, increased mental health literacy within the sporting environment is needed to enable coaches (and other stakeholders) to feel competent when working collaboratively to support the mental health of athletes, while remaining within their professional remit (Lebrun et al., Citation2020).

Intervention findings

Intervention findings were moderate at best, and often non-significant. Challenges recruiting or maintaining an adequate sample size resulted in underpowered studies with non-significant findings to be taken as pilot-data only. Therefore, it could be argued that current interventions are not able to adequately inform policy or practice. However, in the context of mental health, clinical significance may be more indicative of meaningful change than statistical significance. LeFort (Citation1993) suggests that clinical significance should reflect the extent of change, whether this change makes a real difference to people’s lives, how long the effects last, consumer acceptability, cost-effectiveness, and ease of implementation – all of which are relevant when appraising athlete mental health interventions. Suggesting that interventions are ineffective due to not reaching statistical significance neglects the nuanced approach that is required when evaluating intervention effectiveness within mental health. Therefore, while further interventions with larger sample sizes are required, intervention outcomes should also be considered within the context of clinical significance.

Grey literature recommendations

Although grey literature provided some insight into the application of recommendations, more work is needed to ensure cohesion between research and policy. The Duty of Care Review (Grey-Thompson, Citation2017) provides recommendations surrounding athlete welfare, raises the profile of duty of care in sport and provides a starting point for the development of mental health policies. However, the grey literature that followed does not provide sufficiently detailed and applicable recommendations. For example, the IOC Safeguarding Toolkit (2017) mentioned athlete mental health only once within the 106-page toolkit, despite the observed connection between athlete safeguarding, abuse, and mental health (Lang, Citation2021). Similarly, the UK Sport Culture Health Check report (UK Sport, Citation2018) included merely one bullet point regarding athlete mental health as a key area for development despite their findings raising concerns regarding athlete welfare. This included athletes fearful of negative consequences when providing feedback regarding the world class programmes and commenting that governing bodies do not take satisfactory measures to optimise the mental health of athletes. Given the aim of the report was to create a ‘sustainable winning culture’ (UK Sport, Citation2018, p. 14), this suggests that athlete mental health was considered a minor detail in this.

Echoing the need for more consideration of athlete mental health at a policy level, only two UK-based national governing body policies were sourced within the present study, with no academic citations included in either policy. It is important that such policies and frameworks provide insight into their conception to ensure it is supported by contemporary research. Both the lack of policies, and the lack of clarity surrounding the creation of existing policies indicates that more work is needed to bring research out of academia and into applied sport environments, with research informing policy and practice.

Final reflections

Evidence-based practice ‘involves the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of best available research evidence to inform each state of decision-making and service delivery’ (Dozois et al., Citation2014, p. 155). Evidence-based practice is key to allowing sport psychologists to make informed decisions regarding real-world interventions (Gardner & Moore, Citation2006). As such, research must be designed to be impactful in applied settings and address the needs of practitioners (Winter & Collins, Citation2016), to not only fulfil their purpose of guiding future research, but also guiding the creation and implementation of targeted interventions. Both the research-oriented and practice-oriented branches of applied psychology should influence and inform each other (Anderson et al., Citation2002). However, a lack of cohesion within the field is evident. Many of the documents reviewed – particularly intervention studies – either focused on research-based or organisational-based recommendations rather than those pertinent to consulting practice, provided fleeting applied recommendations which lacked detail, or presented no applied recommendations at all. Consequently, applied practitioners are left with little guidance to support intervention design and implementation, and policymakers insufficiently informed on how to create effective guidelines for those within competitive sport. This is perhaps evidenced by the inclusion of merely two (UK-based) national governing body polices within this study which focus on athlete mental health support.

These limitations may have substantial impact on how practitioners and organisations approach athlete mental health, thereby affecting the support available to athletes. For example, mental health-based interventions may simply not be provided due to perceived lack of knowledge regarding how to support athlete mental health. Alternatively, interventions may be created by practitioners based on practice-based evidence (knowledge developed over time by means of professional practice and experience [Holder & Winter, Citation2017]) out of necessity. Winter et al. (Citation2014) suggests that differing aims between researchers and practitioners can cause some practitioners to make limited use of sport psychology research to inform their practice. In this case, a lack of detailed guidance may leave practitioners to seek other sources of information regarding the support of athletes.

Most of the reviewed position and consensus statements presented a vast number of mental health recommendations, but breadth often comes at the expense of depth. For example, Van Slingerland et al. (Citation2019) provided 18 applied recommendations including: ‘coaches must safeguard the mental health of their athletes as well as their own to provide and sustain a healthy training and competitive environment’ (Van Slingerland et al., Citation2019, p. 178). Although sound general advice, guidance on how to safeguard athlete or coach mental health is absent. The processes required to achieve this important goal are not specified. This absence of actionable detail is a feature across all position and consensus statements and may limit their usefulness to applied practitioners.

Future position and consensus statements should consider offering best practice examples through case vignettes to illustrate how such recommendations may be brought to life within sport settings. A case vignette is a brief verbal outline of a scenario, or short story about hypothetical characters in a particular situation (Colman, Citation2015). The use of stories in various formats has long been a powerful and successful tool across health, social, and behavioural sciences (Jeffries & Maeder, Citation2005). Case vignettes are particularly effective in providing a focus and stimulus for discussion, addressing difficult-to-explore and sensitive topics, and reflecting real-life contexts and problems (Jeffries & Maeder, Citation2005), all of which would be valuable when providing stakeholders with detailed guidance surrounding athlete mental health support. By providing stakeholders with case vignettes as examples of best practice alongside recommendations, research would not only be focusing on what is needed to support athlete mental health but would also give insight into how this can be achieved. This level of consideration of the applied implications of research and recommendations can move us towards necessary cohesion within the field, supporting stakeholders to effectively engage in evidence-based practice when supporting athlete mental health.

Although research can go some way towards informing practice, contextual intelligence is also necessary to maximise impact (Terenzini, Citation1993; Tod et al., Citation2011). Therefore, perhaps a pragmatic approach would be to consider the use of practice-based evidence alongside evidence-based practice to inform athlete mental health interventions. This may involve encouraging those in sport to work collaboratively with other professionals. An example of this would be sport psychologists working more closely with clinical psychologists where appropriate – whether that be as part of a referral pathway or seeking peer-support from clinically trained professionals. Research has shown that athletes may benefit from working with mental health practitioners who understand the competitive sport context (Gavrilova & Donohue, Citation2018; Jewett et al., Citation2021; Moesch et al., Citation2018; and Van Slingerland et al., Citation2020). Therefore, collaboration between sport psychologists and clinical professionals (who may be less familiar with the sporting context) may facilitate the tailoring of therapeutic approaches to meet sport-specific demands (see Reardon et al., Citation2019; Van Slingerland et al., Citation2019). Practice-based evidence could also inform mental health interventions via the promotion of dedicated forums for key stakeholders to engage in peer-learning and discussions surrounding best practice when it comes to supporting athletes with their mental health. This collaborative approach provides organised opportunities for practitioners to learn from colleagues with diverse skillsets, leading to increased cooperation, communication, and comfort in implementing interventions as a team (Feather et al., Citation2016; Horsley et al., Citation2016). Engaging with both evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence would enable those working with athletes to draw upon multiple sources and networks to inform their work and provide more effective mental health support.

Limitations

The first limitation of this review is the inclusion of UK-based national governing body policy documents only due to the scope of the review. Future research should explore grey literature from a range of countries to establish a more global understanding of how research influences policy. Additionally, some policies may not be publicly available and were therefore not included. Future considerations for organisations may surround transparency and accessibility to such policies.

Conclusion

The findings of this review prompt reflection on the current state of athlete mental health literature by bringing together key publications and highlighting the gaps and connections between them. The evident lack of cohesion within the field results in a range of implications for both athletes, and all those working to support athlete mental health. A range of steps needs to be taken to ensure researchers, policymakers, and practitioners work cohesively. Improved research efforts are needed to establish effective athlete mental health interventions; researchers must consider their role in informing policy and practice and provide practical recommendations in adequate detail such that those working within the applied field are well-informed to make key considerations, implement strategies, and deliver targeted interventions effectively. Policymakers and those within sporting organisations should be familiar with contemporary research and incorporate this into their polices to create evidence-based guidelines for fellow organisations, staff, and practitioners. Finally, applied practitioners are encouraged to keep up to date with research and recommendations, while developing contextual intelligence within the competitive sport setting through continued applied practice, and thereby combining practice-based evidence with evidence-based practice. When researchers, policymakers, and practitioners better recognise the inevitable and crucial connection across their disciplines and begin to work cohesively, the field of sport psychology will be in a stronger position to provide athletes with effective, evidence-based mental health support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Åkesdotter, C., Kenttä, G., Eloranta, S., & Franck, J. (2020). The prevalence of mental health problems in elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(4), 329–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.022

- Anderson, A. G., Mahoney, C., Miles, A., & Robinson, P. (2002). Evaluating the effectiveness of applied sport psychology practice: Making the case for a case study approach. The Sport Psychologist, 16(4), 432–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.16.4.432

- Bapat, S., Jorm, A., & Lawrence, K. (2009). Evaluation of a mental health literacy training program for junior sporting clubs. Australasian Psychiatry, 17(6), 475–479. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10398560902964586

- Baum, A. (2006). Eating disorders in the male athlete. Sports Medicine, 36(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636010-00001

- Becker, C. B., McDaniel, L., Bull, S., Powell, M., & McIntyre, K. (2012). Can we reduce eating disorder risk factors in female college athletes? A randomized exploratory investigation of two peer-led interventions. Body Image, 9(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.09.005

- Brawn, P., Combes, H., & Ellis, N.. (2015). Football narratives: Recovery and mental health. Journal of New Writing in Health and Social Care, 2(1), 30–46.

- Breedvelt, J. F. (2016). Psychologically informed environments: A literature review. Mental Health Foundation.

- Breslin, G., Shannon, S., Haughey, T., Donnelly, P., & Leavey, G. (2017). A systematic review of interventions to increase awareness of mental health and well-being in athletes, coaches and officials. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0568-6

- Breslin, G., Smith, A., Donohue, B., Donnelly, P., Shannon, S., Haughey, T. J., Vella, S. A., Swann, C., Cotterill, S., Macintyre, T., Rogers, T., & Leavey, G. (2019). International consensus statement on the psychosocial and policy-related approaches to mental health awareness programmes in sport. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 5(1), e000585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000585

- British Canoeing. (2018). Performance wellbeing strategy. Retrieved August 24, from https://www.britishcanoeing.org.uk/

- Buchholz, A., Mack, H., McVey, G., Feder, S., & Barrowman, N. (2008). Bodysense: An evaluation of a positive body image intervention on sport climate for female athletes. Eating Disorders, 16(4), 308–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260802115910

- Byrne, S., & McLean, N. (2002). Elite athletes: Effects of the pressure to be thin. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 5(2), 80–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1440-2440(02)80029-9

- Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Gallinaro, J. G. D. M., Falcão, R. S., Gouttebarge, V., Hitchcock, M. E., Hainline, B., Reardon, C. L., & Stull, T. (2019). Mental health symptoms and disorders in elite athletes: A systematic review on cultural influencers and barriers to athletes seeking treatment. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 707–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100710

- Chang, C., Putukian, M., Aerni, G., Diamond, A., Hong, G., Ingram, Y., Reardon, C. L., & Wolanin, A. (2020). Mental health issues and psychological factors in athletes: Detection, management, effect on performance and prevention: American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement—Executive summary. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(4), 216–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101583

- Colman, A. M. (2015). A dictionary of psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Donohue, B., Chow, G. M., Pitts, M., Loughran, T., Schubert, K. N., Gavrilova, Y., & Allen, D. N. (2015). Piloting a family-supported approach to concurrently optimize mental health and sport performance in athletes. Clinical Case Studies, 14(3), 159–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650114548311

- Donohue, B., Gavrilova, Y., Galante, M., Gavrilova, E., Loughran, T., Scott, J., Chow, G., Plant, C. P. (2018). Controlled evaluation of an optimization approach to mental health and sport performance. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 12(2), 234–267.

- Dozois, D. J., Mikail, S. F., Alden, L. E., Bieling, P. J., Bourgon, G., Clark, D. A., Drapeau, M., Gallson, D., Greenberg, L., Hunsley, J., & Johnston, C. (2014). The CPA presidential task force on evidence-based practice of psychological treatments. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 55(3), 153–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035767

- Elliot, D. L., Goldberg, L., Moe, E. L., DeFrancesco, C. A., Durham, M. B., & Hix-Small, H. (2004). Preventing substance use and disordered eating: Initial outcomes of the ATHENA (Athletes Targeting Healthy Exercise and Nutrition Alternatives) program. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158(11), 1043–1049. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.11.1043

- Elliot, D. L., Goldberg, L., Moe, E. L., DeFrancesco, C. A., Durham, M. B., McGinnis, W., & Lockwood, C. (2008). Long-term outcomes of the ATHENA (Athletes Targeting Healthy Exercise & Nutrition Alternatives) program for female high school athletes. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 52(2), 73.

- Feather, R. A., Carr, D. E., Reising, D. L., & Garletts, D. M. (2016). Team-based learning for nursing and medical students: Focus group results from an interprofessional education project. Nurse Educator, 41(4), E1–E5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000240

- Ferguson, H. L., Swann, C., Liddle, S. K., & Vella, S. A. (2019). Investigating youth sports coaches’ perceptions of their role in adolescent mental health. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1466839

- Fletcher, D., & Arnold, R. (2011). A qualitative study of performance leadership and management in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(2), 223–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.559184

- Fogaca, J. L., Watson, J. C., & Zizzi, S. J. (2020). The journey of service delivery competence in applied sport psychology: The arc of development for new professionals. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 14(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2019-0010

- Gabana, N. (2017). A strengths-based cognitive behavioral approach to treating depression and building resilience in collegiate athletics: The individuation of an identical twin. Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/cssep.2016-0005

- Gardner, F., & Moore, Z. (2006). Clinical sport psychology. Human kinetics.

- Gavrilova, Y., & Donohue, B. (2018). Sport-specific mental health interventions in athletes: A call for optimization models sensitive to sport culture. Journal of Sport Behavior, 41(3), 283–304.

- Gavrilova, Y., Donohue, B., & Galante, M. (2017). Mental health and sport performance programming in athletes who present without pathology: A case examination supporting optimization. Clinical Case Studies, 16(3), 234–253.

- GB Judo. (2018). Athlete welfare framework. Retrieved July 23, from https://www.britishjudo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Athlete-Welfare-Framework-29th-November_for-board-1.pdf

- Gorczynski, P., Gibson, K., Thelwell, R., Papathomas, A., Harwood, C., & Kinnafick, F. (2019). The BASES expert statement on mental health literacy in elite sport. The Sport and Exercise Scientist, 59, 6–7.

- Grey-Thompson, T. (2017). Duty of care in sport: Independent report to government. Department for Culture, Media & Sport.

- Gross, M., Moore, Z. E., Gardner, F. L., Wolanin, A. T., Pess, R., & Marks, D. R. (2018). An empirical examination comparing the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment approach and psychological skills training for the mental health and sport performance of female student athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(4), 431–451. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1250802

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2012). Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-157

- Gustafsson, H., Lundqvist, C., & Tod, D. (2017). Cognitive behavioral intervention in sport psychology: A case illustration of the exposure method with an elite athlete. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8(3), 152–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2016.1235649

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R., Moesch, K., McCann, S., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., & Terry, P. (2020). Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(5), 553–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473

- Holder, T., & Winter, S. (2017). Experienced practitioners’ use of observation in applied sport psychology. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 6(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000072

- Horsley, T. L., Reed, T., Muccino, K., Quinones, D., Siddall, V. J., & McCarthy, J. (2016). Developing a foundation for interprofessional education within nursing and medical curricula. Nurse Educator, 41(5), 234–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000255

- International Olympic Committee (IOC). (2017). Safeguarding athletes from harassment and abuse in sport. IOC Toolkit for Ifs and NOCs. Retrieved October 20, 2018, from https://www.olympic.org/safeguarding/_ga¼2.84174425.1586521679.1542300732-1203065566.1537098370

- Jeffries, C., & Maeder, D. W. (2005). Using vignettes to build and assess teacher understanding of instructional strategies. Professional Educator, 27, 17–28.

- Jewett, R., Kerr, G., & Dionne, M. (2021). Canadian athletes’ perspectives of mental health care and the importance of clinicians’ sport knowledge: A multi-method investigation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 53, 101849. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101849

- Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539

- Kroshus, E., Wagner, J., Wyrick, D. L., & Hainline, B. (2019). Pre-post evaluation of the “Supporting Student-Athlete Mental Wellness” module for college coaches. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 13(4), 668–685.

- Küttel, A., & Larsen, C. H. (2019). Risk and protective factors for mental health in elite athletes: A scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 231–265.

- Lang, M. (2021). Routledge handbook of athlete welfare. Routledge.

- Lebrun, F., MacNamara, À., Collins, D., & Rodgers, S. (2020). Supporting young elite athletes with mental health issues: Coaches’ experience and their perceived role. The Sport Psychologist, 34(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2019-0081

- LeFort, S. M. (1993). The statistical versus clinical significance debate. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 25(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00754.x

- Liddle, S. K., Deane, F. P., & Vella, S. A. (2017). Addressing mental health through sport: A review of sporting organizations’ websites. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 11(2), 93–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12337

- Martinsen, M., Bahr, R., Børresen, R. U. N. I., Holme, I., Pensgaard, A. M., & Sundgot- Borgen, J. (2014). Preventing eating disorders among young elite athletes: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 46(3), 435–447.

- Martinsen, M., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2013). Higher prevalence of eating disorders among adolescent elite athletes than controls. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 45(6), 1188–1197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318281a939

- Mazzer, K. R., & Rickwood, D. J. (2015). Mental health in sport: Coaches’ views of their role and efficacy in supporting young people's mental health. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 53(2), 102–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2014.965841

- McCalla, T., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2016). Integrating sport psychology within a high-performance team: Potential stakeholders, micropolitics, and culture. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2015.1123208

- Moesch, K., Kenttä, G., Kleinert, J., Quignon-Fleuret, C., Cecil, S., & Bertollo, M. (2018). FEPSAC position statement: Mental health disorders in elite athletes and models of service provision. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 38, 61–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.05.013

- Mohammed, W. A., Pappous, A., & Sharma, D. (2018). Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) in increasing pain tolerance and improving the mental health of injured athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 722. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00722

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Papathomas, A. (2014). A few good men: Male athlete eating disorders, medical supremacy and the silencing of a sporting minority. In R. J. Schinke & K. R. McGannon (Eds.), The psychology of sub-culture in sport and physical activity (pp. 107–120). Routledge.

- Parrott, S., Billings, A. C., Buzzelli, N., & Towery, N. (2021). “We all go through it”: Media depictions of mental illness disclosures from star athletes DeMar DeRozan and Kevin Love. Communication & Sport, 9(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479519852605

- Petrie, T. A., Greenleaf, C., Reel, J., & Carter, J. (2008). Prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors among male collegiate athletes. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 9(4), 267–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013178

- Phipps, C., Seager, M., Murphy, L., & Barker, C. (2017). Psychologically informed environments for homeless people: Resident and staff experiences. Housing, Care and Support, 20(1), 20–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/HCS-10-2016-0012

- Poucher, Z. A., Tamminen, K. A., Kerr, G., & Cairney, J. (2021). A commentary on mental health research in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 33(1), 60–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2019.1668496

- Purcell, R., Gwyther, K., & Rice, S. M. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes: Increased awareness requires an early intervention framework to respond to athlete needs. Sports Medicine - Open, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-019-0220-1

- Reardon, C. L., & Factor, R. M. (2010). Sport psychiatry. Sports Medicine, 40(11), 961–980. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2165/11536580-000000000-00000

- Reardon, C. L., Hainline, B., Aron, C. M., Baron, D., Baum, A. L., Bindra, A., Budgett, R., Campriani, N., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Currie, A., Derevensky, J. L., Glick, I. D., Gorczynski, P., Gouttebarge, V., Grandner, M. A., Han, D. H., McDuff, D., Mountjoy, M., Polat, A., … Engebretsen, L. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 667–699. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715

- Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., De Silva, S., Mawren, D., McGorry, P. D., & Parker, A. G. (2016). The mental health of elite athletes: A narrative systematic review. Sports Medicine, 46(9), 1333–1353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2

- Roberts, C. M., Faull, A. L. (2016). Blurred lines: Performance enhancement, common mental disorders and referral in the UK athletic population. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1067.

- Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2018). International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(6), 622–639. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

- Sebbens, J., Hassmén, P., Crisp, D., & Wensley, K. (2016). Mental health in sport (MHS): improving the early intervention knowledge and confidence of elite sport staff. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 911. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00911

- Shannon, S., Hanna, D., Haughey, T., Leavey, G., McGeown, C., & Breslin, G. (2019). Effects of a mental health intervention in athletes: Applying self-determination theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1875. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01875

- Smith, A., & Petrie, T. (2008). Reducing the risk of disordered eating among female athletes: A test of alternative interventions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(4), 392–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200802241832

- Stranberg, M., Slager, E., Spital, D., Coia, C., & Quatromoni, P. A. (2020). Athlete-specific treatment for eating disorders: Initial findings from the Walden GOALS program. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.07.019

- Sundgot-Borgen, J., & Torstveit, M. K. (2004). Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 14(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00042752-200401000-00005

- Terenzini, P. T. (1993). On the nature of institutional research and the knowledge and skills it requires. Research in Higher Education, 34(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991859

- Tod, D., Andersen, M. B., & Marchant, D. B. (2011). Six years up: Applied sport psychologists surviving (and thriving) after graduation. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2010.534543

- Torstveit, M. K., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2008). Prevalence of eating disorders and the predictive power of risk models in female elite athletes: A controlled study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 18(1), 108–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00657.x

- UK Government. (2018). Mental health and elite sport action plan. Retrieved July 23, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/691770/180320_FINAL_Mental_Health_and_Elite_Sport_Action_Plan.pdf

- UK Sport. (2018). 2017 culture health check. Retrieved May 18, from http://www.uksport.gov.uk/~/media/files/chc-report-final.pdf?la=en

- Van Slingerland, K., Durand-Bush, N., DesClouds, P., & Kenttä, G. (2020). Providing mental health care to an elite athlete: The perspective of the Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport team. Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4(S1), S1–S17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/cssep.2019-0022

- Van Slingerland, K. J., Durand-Bush, N., Bradley, L., Goldfield, G., Archambault, R., Smith, D., Edwards, C., Delenardo, S., Taylor, S., Werthner, P., & Kenttä, G. (2019). Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport (CCMHS) position statement: Principles of mental health in competitive and high-performance sport. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 29(3), 173–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000665

- Vella, S. A., Schweickle, M. J., Sutcliffe, J. T., & Swann, C. (2021). A systematic review and meta-synthesis of mental health position statements in sport: Scope, quality and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, 101946. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101946

- Winter, S., & Collins, D. J. (2016). Applied sport psychology: A profession? The Sport Psychologist, 30(1), 89–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2014-0132

- Winter, S., MacPherson, A. C., & Collins, D. (2014). “To think, or not to think, that is the question”. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 3(2), 102–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000007

- Yang, J., Peek-Asa, C., Corlette, J. D., Cheng, G., Foster, D. T., & Albright, J. (2007). Prevalence of and risk factors associated with symptoms of depression in competitive collegiate student athletes. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 17(6), 481–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0b013e31815aed6b