ABSTRACT

There has recently been a surge in sport psychology research examining various aspects of the interpersonal and social processes related to emotions and emotion regulation. The purpose of this study was to review the literature related to the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport, in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the studies that have been conducted to date. A scoping review of the literature (Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. [2009]. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108) using a systematic search process returned 7,769 entries that were screened for inclusion; the final sample of studies included in the review consisted of 79 relevant articles and 8 dissertations. The results describe the interconnected findings on athletes’ self-regulation of emotions in social contexts, interpersonal emotion regulation, collective emotions (group-based emotions, emotional contagion, and effervescence), emotional expressions, and individual and contextual moderators (e.g. personality, culture, norms, gender, roles, and situational/temporal aspects). We identify key issues to advance theory and research, including: the need for programmatic research to investigate these processes, their effects, and underlying mechanisms; greater theoretical and conceptual clarity; more research among diverse populations (e.g. female athletes, youth athletes); the need to consider interconnected emotional phenomena in future research; and the need for applied intervention research.

Indisputably, sport is an emotional context with athletes, coaches, and spectators being highly invested in their endeavours, and experiencing and exhibiting a range of emotions and affective experiences (Jones & Uphill, Citation2012). Emotions are relatively brief episodes of responses to events that are deemed to be of major significance to individuals (Wagstaff & Tamminen, Citation2021), with commonly studied emotions including anxiety, sadness, fear, anger, joy, or pride. Substantial research has examined the experiences and impacts of different types of emotions in sport (Jones et al., Citation2005), the fluctuations in emotions across sporting events and seasons (e.g. Hanton et al., Citation2002; Levillain et al., Citation2022), the consequences of emotions for performance (Doron & Martinent, Citation2021), and impacts of emotions and emotion expressions for team functioning (Tamminen, Palmateer, et al., Citation2016). Given the impact of emotions on athletes’ sport performance, there have also been substantial efforts devoted to understanding how athletes regulate their emotions. For example, athletes have been found to use a variety of emotion regulation strategies to deal with stressors and resultant emotions in sport (e.g. Stanley et al., Citation2012), and these strategies vary in their effectiveness for managing emotions (Balk et al., Citation2013). In addition, many sport psychology interventions focus on athletes’ emotions and emotion regulation (Uphill et al., Citation2009), further illustrating the importance of emotions and the need for effective emotion regulation to achieve performance success.

Recently, sport psychology researchers have started to examine how emotions and emotion regulation processes function within the social context of sport, and there has been a notable ‘interpersonal turn’ and an increase in research examining the social aspects of emotional phenomena in sport (Wagstaff & Tamminen, Citation2021). Notably, researchers have examined the emotional expressions of athletes and coaches in sport settings and the ways that these expressions may influence individuals and groups (e.g. Allan & Côté, Citation2016; Lee & Chelladurai, Citation2016; Wolf et al., Citation2018), the experience of collective emotions (e.g. Reyson & Branscombe, Citation2010; Stieler & Germelmann, Citation2016) and group-based emotions (e.g. Campo, Champely, Louvet, et al., Citation2019; Campo, Mackie, Champely, et al., Citation2019), as well as emotional self-regulation and the ways that athletes and coaches may attempt to regulate the emotions of others (e.g. Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019; Tamminen, Gaudreau, et al., Citation2016). These studies attest to a conceptualization of emotions as social phenomena as well as their social influences, causes, and opportunities for regulation.

At this point, researchers have reviewed some of the interpersonal emotion phenomena separately (e.g. interpersonal emotion regulation, Friesen, Lane, et al., Citation2013; identity-based emotions, Campo et al., Citation2019; nonverbal behaviour, Furley, Citation2021). Yet, we believe the expanding literature on the social and interpersonal aspects of athletes’ emotions and emotion regulation may benefit from being subjected to a review that examines the breadth of existing research across multiple areas, as these are conceptually adjacent but have been studied in isolation. For example, nonverbal emotion expressions may be used for interpersonal emotion regulation, which may in turn induce identity-based emotions. A review of these related concepts can provide clarity about similar phenomena and processes that have been studied to date, and it can identify areas where concepts or processes may have been investigated in ‘silos’ and hence would benefit from further integration. Thus, the purpose of this study was to conduct a comprehensive scoping review of the literature related to the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport.

Surveying the terrain: existing theories and concepts

In undertaking a review of the literature on the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport, it is apparent that there are multiple concepts, models, and theoretical frameworks that have informed investigations of these phenomena. For example, sport researchers (e.g. Friesen et al., Citation2015; van Kleef et al., Citation2019) have drawn on van Kleef’s (Citation2009) Emotions as Social Information (EASI) model which theorizes the ways in which emotional expressions influence others. Specifically, the EASI model proposes that emotional expressions trigger either more automatic affective reactions or more deliberate inferential processing in the observers and these, in turn, drive behavioural responses (van Kleef, Citation2009; van Kleef & Côté, Citation2022). For instance, an athlete may perceive the emotional expressions of a teammate or a coach and respond with reciprocal or complementary emotions (e.g. anger expressions triggering anger versus fear responses), while making inferences about the other person’s emotions, attitudes, values, and intended actions, and responding accordingly (e.g. interpreting anger expressions as the communication of performance dissatisfaction and increasing one’s effort on subsequent tasks).

In addition to the EASI model, researchers (e.g. Friesen et al., Citation2015; Furley et al., Citation2015) have used Keltner and Haidt’s (Citation1999) broader social-functional perspective of emotions to investigate the ways that emotions function within social contexts in sport. Keltner and Haidt (Citation1999) outlined that emotions serve social functions and coordinate behaviour in groups in several ways: by informing individuals about their social context or events that require action; by preparing individuals to respond to problems that arise in interactions with others; by communicating emotions, beliefs, and intentions to others; by evoking complementary or reciprocal emotions in others; by helping define group boundaries and identifing group membership and status; and by defining cultural identities and communicating cultural norms, values, and power structures.

Aside from these more comprehensive theoretical accounts of the social effects of emotions, researchers in sport have also investigated specific socio-emotional phenomena. One of these phenomena is collective emotions, an emergent state that is characterized by the ‘[agreement] in affective responding across individuals towards a specific event or object’ (von Scheve & Ismer, Citation2013, p. 406). Under this umbrella term, researchers have investigated group-based emotions (Campo, Mackie, Champely, et al., Citation2019), which are a type of collective emotions that result from individuals’ identification with a social group (e.g. a sports team) and events that impact this group (Smith, Citation1993), and emotional contagion, a process whereby individuals ‘catch’ others’ emotional responses (Hatfield et al., Citation1994), potentially resulting in emotional agreement. Some research in sport also documents the occurrence of collective effervescence, a particular collective emotional phenomenon that is characterized by shared attention and action, amplified emotional responsiveness, and intense positivity (Durkheim, Citation1965). Finally, regarding the regulation of emotions in interpersonal or social settings, researchers in sport have drawn on conceptualizations offered by Niven et al. (Citation2011) and Gross and Thompson (Citation2007) that detail the various regulatory strategies that individuals may use to maintain, increase, or decrease their own and others’ emotional states (e.g. Campo et al., Citation2017; Tamminen, Gaudreau, et al., Citation2016; Citation2019).

Overall, there is a growing collection of studies and reviews in the sport literature that focus on the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions, and they have variously drawn on different concepts and theoretical perspectives (e.g. Campo et al., Citation2019; Friesen, Lane, et al., Citation2013; Furley, Citation2021; Tamminen & Bennett, Citation2017). Undertaking a comprehensive review of the literature across these phenomena would be valuable in providing a bridge across ‘islands’ of research that have been conducted in adjacent topic areas, identifying advances and gaps in the literature, and informing future theorizing and inquiry in a more interconnected manner. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct a scoping review of the literature related to the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport.

Methods

Scoping review

We conducted a scoping review of the literature, which aims to ‘map the key concepts that underpin a field of research, as well as to clarify working definitions, and/or the conceptual boundaries of a topic’ (Peters et al., Citation2020, p. 408). A scoping review is well-suited to addressing broad research questions in order to review and synthesize the existing literature, to ‘summarize an abundance of information to broadly discern what is known on a given topic’ (Sabiston et al., Citation2021, p. 2), and to provide recommendations for future research and practice (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). Because scoping reviews are used to provide a broad overview of a topic and the results are mainly descriptive or thematic (Sabiston et al., Citation2021), a quality assessment is generally not performed on studies included in the review (Peters et al., Citation2020).

Search strategy

We systematically searched the literature across three databases (PsychINFO, SPORTDiscus, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global), and conducted a backward search of references in the articles retrieved from the database searches (Harari et al., Citation2020). The list of keywords for database searches is included in the Supplementary Materials. We also sought the assistance of a librarian with expertise in database searches to support our search strategy. Other potential articles to include in the review were determined based on the authors’ knowledge of the literature. Searching at least two databases, searching the ‘grey’ literature (e.g. dissertations and theses), and including additional complementary search strategies (e.g. backward search of references, librarian peer reviewer of search protocols, personal correspondence and knowledge of the literature) are strategies that have been recommended for meeting the expectations of a high-quality literature search (Harari et al., Citation2020).

Database search

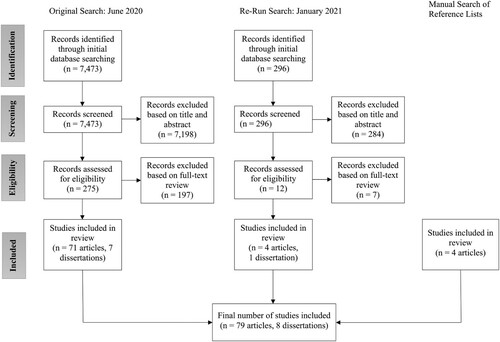

See for an overview of the search procedures. The initial database search returned 7,473 records (3,745 from PsycINFO, 3,564 from SPORTDiscus, 164 from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global). The third and fourth authors conducted an initial screening and independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of each record (inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in the Supplementary Materials). For the records that were identified for potential inclusion by the research team (176 from PsychINFO, 89 from SPORTDiscus, 10 dissertations from ProQuest), the first and second authors reviewed the full texts and determined which records to include in the review (47 articles and three dissertations from PsycINFO, 24 articles from SPORTDiscus, four dissertations from ProQuest). Of the 197 articles that were excluded after full-text review, 23 articles and one dissertation were excluded for being flagged as duplicates.

The database search was re-run in January 2021 using the same procedures (see ), returning an additional 296 records (181 records from PsycINFO, 109 records from SPORTDiscus, and 6 dissertations from ProQuest) which were screened by the third and fourth authors. Twelve records were identified for potential inclusion and full-text review following this initial screening (7 articles from PsycINFO, 4 articles from SPORTDiscus, and 1 dissertation from ProQuest). The first and second authors then reviewed the 12 records, retaining 4 articles and 1 dissertation for inclusion in the review.

As displayed in , a manual search of the reference lists of included articles was also conducted. In total, 79 articles and 8 dissertations were included in the present review; of these, 6 had a corresponding published article that was based on data from the dissertation. For the purposes of the present review, the authors’ primary focus was on peer-reviewed articles, which took precedence in the analysis over their corresponding dissertations.

Scoping review data extraction and synthesis of results

A spreadsheet was created to extract details regarding the purpose, participants, sample, methodology, data collection, data analysis, and key findings for each study included in the review (see Supplementary Materials Table S1). The analysis and synthesis of the study findings was led by the first and second authors; this process began by reading each article and summarizing the key findings from each study, as well as identifying the main topic(s) that the article contributed to within the scope of the review (e.g. collective emotions, interpersonal emotion regulation, etc.). Subsequently, we worked across articles to synthesize the findings, consider the scope and focus of concepts that were investigated, as well as to identify gaps in the literature.

Results and discussion

The interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport contexts covers a broad range of emotional phenomena, including athletes’ emotional self-regulation in social contexts, interpersonal emotion regulation (between teammates, opponents, and from coaches), collective emotions (including group-based emotions, emotional contagion, and effervescence), emotional expressions as well as the individual and contextual properties moderating the experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in social contexts (i.e. personality, culture, norms, gender, roles, and situational/temporal aspects). In many cases, studies produced findings related to multiple areas; in the following results and discussion section we summarize the key findings within each of these topic areas, while also acknowledging that these are loose boundaries and that these concepts are interrelated. A summary of the descriptive features of the included articles is provided in ; a summary of the included dissertations is included in .

Table 1. Summary of descriptive information from included articles.

Table 2. Summary of descriptive information from included dissertations.

Emotional self-regulation in social contexts

Athletes’ emotional self-regulation is implicated in the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions. For example, male rugby players (Campo et al., Citation2017) and female curlers (Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013) report engaging in self-regulation and interpersonal emotion regulation strategies during competitions, while sporting officials (Friesen et al., Citation2017) and coaches (Hodgson et al., Citation2017; Mueller et al., Citation2018) also report using self-regulation strategies to manage their emotions while attempting to regulate the emotions of others. Athletes’ capacity to engage in interpersonal emotion regulation, however, may be attenuated or constrained because they are focused on their own emotional self-regulation, and athletes’ attentional and emotional capacity to help teammates regulate their emotions may be limited in challenging situations (Campo et al., Citation2017; Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013). Further, athletes’ confidence in their ability to regulate their own emotions and their teammates’ emotions is significantly correlated with the frequency of athletes’ self – and interpersonal emotion regulation efforts (Friesen et al., Citation2019).

A particular type of emotional self-regulation in social contexts is emotional labour. Emotional labour refers to the ‘regulation of both feeling and expression of emotions to achieve organizational goals’ (Grandey, Citation2000, p. 97) and consists of three facets: surface acting (modifying outward expression of emotions), deep acting (attempting to modify and express feelings appropriate to the situation), and genuine expression (spontaneously experiencing and displaying appropriate emotions). In line with its relation to work roles and organizational norms, emotional labour has been studied among coaches (e.g. Lee & Chelladurai, Citation2016) and within sport organizations (Larner et al., Citation2017). Here, surface acting in particular appears to contribute to negative outcomes, including burnout and intentions to leave sport organizations (Larner et al., Citation2017). Additional qualitative investigations of emotional labour among athletes have been conducted by Collinson (Citation2005), Evers (Citation2019), Gallmeier (Citation1987), Sinden (Citation2010), Mankad and colleagues (Citation2009), Sacha (Citation2017), and Smith (Citation2008); we noted several of these studies have been published in the sport sociology literature. The results from these rich qualitative accounts demonstrate athletes’ engagement in emotional labour or forms of emotion management to try and appear positive and confident in the face of adversity, such as when dealing with injuries and during rehabilitation (e.g. Mankad et al., Citation2009; Sinden, Citation2010). For example, Mankad et al. (Citation2009) noted that injured athletes suppressed their actual emotions to make coaches feel better and to ensure younger athletes were not negatively affected by witnessing negative emotions surrounding injury. Evers (Citation2019) also described the use of surface acting among free surfers to appear authentic to their fans and to avoid losing sponsorship or being replaced, resulting in a loss of joy and interest in surfing and increased experiences of depression.

Interpersonal emotion regulation

Under the umbrella of interpersonal emotion regulation, researchers have predominantly examined direct actions between teammates to regulate one another’s emotions (Tamminen, Gaudreau, et al, Citation2016; Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013; Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018; Tamminen et al., Citation2019; Wolf et al., Citation2018), although playing music via speakers in the locker room might also be a strategy to regulate the team’s arousal level and emotions to enhance performance (Swary, Citation2020). In addition, researchers have explored sledging by opponents (Davis et al., Citation2018; Ring et al., Citation2019), interpersonal emotion regulation among referees (Friesen et al., Citation2017), and strength and conditioning coaches’ actions to regulate others’ emotions in order to promote effective organizational functioning, gain compliance, and work effectively with their clients (Hings, Wagstaff, Thelwell et al., Citation2018; Wagstaff et al., Citation2012b).

Athletes have been found to use a number of different strategies in combination to improve or worsen the emotions of others (Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018; Tamminen, Gaudreau, et al., Citation2016; Citation2019), including verbal and behavioural strategies (Friesen et al., Citation2015) and deliberate and non-deliberate strategies (Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013). In some cases these strategies have been categorized according to their purported function along Gross’ (Citation1998) process model of emotion regulation (e.g. situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, response modulation; Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019; Campo et al., Citation2017; Friesen et al., Citation2017). Athletes also report multiple reasons or motives for engaging in interpersonal emotion regulation, including instrumental (i.e. performance) and social-relational motives (Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013), or alternatively, for altruistic motives (purpose was for the best interest of the teammate), egoistic motives (purpose was for one’s own personal benefits), or a combination of these motives (Campo et al., Citation2017). In line with these motives, athletes perceive interpersonal emotion regulation actions to be associated with performance outcomes and teammate relationships (Campo et al., Citation2017; Friesen et al., Citation2015; Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013; Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018). Notably, varsity athletes’ receipt of affect-worsening interpersonal emotion regulation from teammates has been associated with poorer team performance (Tamminen et al., Citation2019), and adolescent athletes’ efforts to regulate their teammates’ emotions are associated with their own sport enjoyment and commitment (Tamminen, Gaudreau, et al., Citation2016).

Given there is relatively little quantitative research supporting the purported associations between interpersonal emotion regulation and important outcomes in sport, there is a need for further research to establish the extent to which interpersonal emotion regulation actually affects athletes’ emotions and performance, as well its impact on other important outcomes such as perceived quality of relationships, team cohesion, and collective efficacy. Furthermore, researchers should consider both self-regulation and interpersonal emotion regulation processes concurrently, as these have generally been examined as separate processes. Another area of future research that may advance this topic could be to examine athletes’ capacity to engage in self- and interpersonal emotion regulation, and the qualities, characteristics, and skills of particularly effective emotional regulators.

Interpersonal emotion regulation by coaches

Although interpersonal emotion regulation has been investigated mostly among athletes, coaches too engage in various strategies to try and regulate the emotions of their athletes, potentially compensating for athletes’ need for self-regulation (Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019). In these efforts, coaches use a variety of strategies such as adapting a workout, goal-setting, and dressing room slogans (Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019; Donoso-Morales et al., Citation2017; Gallmeier, Citation1987). Nonetheless, the most pronounced tool coaches use to regulate their teams’ emotions is their speeches before and during competitions (Allain et al., Citation2018; Gallmeier, Citation1987; Staw et al., Citation2019; Turman, Citation2005, Citation2007). Coaches’ speeches seem to be an effective tool for interpersonal emotion regulation because they impact teams’ emotions, energy levels, inspiration, confidence, motivation, and focus (Gonzalez et al., Citation2011; Vargas & Short, Citation2011). Interestingly, coaches take into account hedonic costs (e.g. inducing greater unpleasant affect) in order to further instrumental outcomes (e.g. greater effort by athletes; Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019; Donoso-Morales et al., Citation2017; Gallmeier, Citation1987). Finally, coaches tailor their speeches depending on the circumstances (see section below on situational and temporal dynamics), team emotions, and athlete leader activity (e.g. emotion regulation by coaches may be unnecessary when athlete leaders have done the job already; Allain et al., Citation2018).

Collective emotions

Athletes have reported the existence and experience of both pleasant and unpleasant collective emotions (Tamminen, Palmateer, et al., Citation2016) and teams also show affective agreement (Filho, Citation2020) or expressions of collective happiness and anger (Hopfensitz & Mantilla, Citation2019). As in other contexts (Knight & Eisenkraft, Citation2015), collective emotions in sport are perceived to amplify individual emotional experiences, impact teams’ task-related functioning, and support groups’ social integration (e.g. communicate team values; Tamminen, Palmateer, et al., Citation2016). For example, more intense positive team-referent emotions predicted better rugby performance at both player and team levels (Campo, Champely, Louvet, et al., Citation2019) ‘and greater collective happiness predicted better performance in baseball, softball, and soccer teams (van Kleef et al., Citation2019). Conversely, greater collective anger predicted worse team performance (van Kleef et al., Citation2019) and negative collective emotions have been identified as correlates and drivers of collective team collapse (Wergin et al., Citation2018). At the most basic level, collective emotions arise if individuals encounter the same environmental stimulus, such as shared (organizational) stressors, (strategic) leader input, or (publicly broadcasted) locker room music (Swary, Citation2020; Tamminen, Palmateer, et al., Citation2016), or if they pursue and achieve collective goals (Campo, Champely, Louvet, et al., Citation2019; Tamminen, Palmateer, et al., Citation2016).

Group-based emotions

In a sport context, experiencing emotions ‘on behalf of the team’ (Tamminen, Palmateer, et al., Citation2016, p. 32) have been reported by athletes but seem to be especially prevalent in spectators. Specifically, fans’ emotions appear to change in line with their favoured teams’ performance (Jones et al., Citation2012), with soccer fans feeling more intense negative emotions following a loss compared to a win of their national teams (Crisp et al., Citation2007), baseball fans feeling pride in response to their favoured teams’ good performance (Chang et al., Citation2017), and students experiencing intense happiness after challenging but victorious matches, yet decreased happiness in response to a loss of their universities’ basketball and American football teams (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Citation2020; Wann et al., Citation1994). Notably, in both spectators and athletes, emotional intensity increased with stronger social identification (Crisp et al., Citation2007; Faure et al., Citation2014; Lee, Citation2014; Reyson & Branscombe, Citation2010; Wann et al., Citation1994). Inversely, aligned with the notions of Basking In Reflected Glory (BIRGing; Cialdini et al., Citation1976) and Cutting Off Reflected Failure (CORFing; Snyder et al., Citation1986), the greater experience of positive group-based emotions linked with stronger social identification and self-esteem (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Citation2020; Sullivan, Citation2018; Vargas-Salfate et al., Citation2020).

Finally, whereas athletes’ collective self-construal did not predict emotions during competition (Campo et al., Citation2018), it seems to relate to the quality of emotional experiences prior to and after competition, with greater collective construals relating to athletes’ increased positive and reduced negative emotions in response to teammates and opponents (Campo, Mackie, Champely, et al., Citation2019). Additionally, sport fans’ collective construals are associated with increased anger and reduced sadness in response to a team loss (Crisp et al., Citation2007). Specifically, collective self-construal related to a reduced tendency to avoid fans of the opposing team after a loss; these findings align with intergroup emotions theory (i.e. group-based emotion driving behaviour towards the outgroup; Mackie & Smith, 1998) and the innate action tendencies associated with emotions (i.e. sadness possessing a greater avoidance orientation than anger).

Emotional contagion

Athletes from various sports have reported the contagion of both pleasant and unpleasant emotions within their teams (Petitta & Jiang, Citation2020; Swary, Citation2020; Wergin et al., Citation2018; Wolf et al., Citation2018) and these processes have been linked with teams’ collective emotions (Totterdell, Citation2000; Wolf et al., Citation2018). Spectators, too, have been observed to catch each other’s emotional valence, yet only if they were fans of the same team (i.e. members of the same social category; Weisbuch & Ambady, Citation2008). Importantly, emotional contagion (and the resultant collective emotions) seems to impact team performance in that a transfer of happiness predicted better performance (Totterdell, Citation2000; van Kleef et al., Citation2019), whereas a transfer of negative emotions (e.g. anger, fear) predicted dysfunctional goal pursuit (Petitta & Jiang, Citation2020), reduced team performance (Petitta & Jiang, Citation2020; van Kleef et al., Citation2019), and perpetuated collective team collapse (Wergin et al., Citation2018). Potentially due to these consequences, some athletes employ emotion regulation in order to prevent undesired emotional contagion. For example, injured athletes hide their negative emotions because they want to avoid them spreading to teammates and coaches (Mankad et al., Citation2009), and members distance themselves from their team prior to a match to avoid catching suboptimal emotions (Wolf et al., Citation2018). In addition, teammates may work to compensate each other’s affect to maintain an optimal average (Filho, Citation2020). These findings demonstrate the interconnectedness of athletes’ experience of emotions in team and group settings with their self- and interpersonal emotion regulation efforts.

Collective effervescence

Collective effervescence has been documented primarily in crowds of American football and soccer spectators (Cottingham, Citation2012; Stieler & Germelmann, Citation2016; Vargas-Salfate et al., Citation2020). However, athletes also experience collective effervescence, for example, as part of a national team (Faure et al., Citation2014) or group-based physical activity (Zumeta et al., Citation2016). Key correlates and potential consequences of collective effervescence are greater group identification, integration, and efficacy. As such, experiences of stronger effervescence are linked with spectators’ enhanced in-group bias, unity, perceived community, and confidence (Cottingham, Citation2012; Stieler & Germelmann, Citation2016). Similarly, stronger effervescence within athlete groups was perceived to increase groupness and cohesion (Faure et al., Citation2014), and predicted enhanced collective efficacy and shared flow (Zumeta et al., Citation2016). Potentially due to the intense positivity that accompanies effervescence, however, the greater group identification and efficacy do not seem to coincide with in-group (i.e. national) favouritism or out-group (i.e. immigrant) derogation (Vargas-Salfate et al., Citation2020).

With regard to shared attention, soccer fans reported experiencing effervescence if they had a shared goal, and American football fans exhibited stronger effervescence if they were closer to one another and had a shared focus of attention (Cottingham, Citation2012); this is also supported by experimental evidence that indicates watching an American football match in the company of others, as compared to alone, increases the processing of positive emotions (Lee, Citation2014). With regard to symbols and rituals, both spectators and athletes reported the importance of group-specific symbols such as flags, uniforms, logos, and team colours to reinforce group boundaries (Cottingham, Citation2012; Faure et al., Citation2014; Stieler & Germelmann, Citation2016), and soccer fans emphasized the role of ritualized, coordinated actions such as clapping and chanting in developing effervescence (Stieler & Germelmann, Citation2016).

Despite this evidence, collective emotions in sport remain an emergent research area. Future work could focus on providing conceptual evidence and processes at the group level, considering that group-based emotions essentially operate at the member level. Studies could further research the mechanisms of emotional contagion (e.g. social appraisal, Manstead & Fischer, Citation2017; emotional mimicry, Hess & Fischer, Citation2013) and, considering that these do not operate indiscriminately (e.g. only within the in-group; Weisbuch & Ambady, Citation2008), investigate the functionality of these processes for team coordination and social integration. This insight could then further inform the regulation of collective emotions via, for example, strategic self-construal expansion or contraction (Jones & Memmert, Citation2020), calculated emotional contagion (Evers, Citation2019; Wagstaff et al., Citation2012b), or tactical emphasis of collective symbols and rituals.

Emotional expressions and nonverbal behaviours

Across emotional self-regulation, interpersonal emotion regulation, and collective emotions, one crucial component seems to be the overt nonverbal expressions of emotions. In contrast to other types of nonverbal behaviours (for a comprehensive review in sport, see Furley, Citation2021), emotion expressions are signals and hence communicate information (Shariff & Tracy, Citation2011). This information can be used as the basis of one’s own emotional response, to infer performance expectations, or to motivate particular behaviours. Notably, participants’ perceptions of baseball pitchers’ anger versus happiness led to expectations of faster, more difficult, and more accurate pitches (Cheshin et al., Citation2016). However, participants’ expectations were not consistent with pitchers’ actual throwing speed, difficulty, or accuracy, suggesting that people may form impressions of athletes’ potential for performance based on emotional displays, but that these impressions do not necessarily correspond to the athletes’ actual performance.

Nonetheless, athletes are rated as more confident, more composed, more relaxed, happier, and less ashamed when displaying pride in soccer penalty shootout scenarios, whereas they were rated as less confident, less happy, more stressed, more excited, and more ashamed when displaying shame (Furley et al., Citation2015). Moreover, when participants assumed the role of a teammate observing expressions of pride, they themselves expected to be more confident and in control, feel more pride and happiness, and have better performance; whereas participants expected poorer cognitions, more shame, and lower performance when assuming the role of an opposing player (the reverse was true for expressions of shame). The implication is that expressions of pride may have positive effects on teammates and negative effects on opponents, while expressions of shame may have negative effects on teammates and positive effects on opponents. However, athletes’ emotional displays do not occur in a vacuum, and they are influenced by match outcome, social interactions, and audiences, as demonstrated by Crivelli et al. (Citation2015) who found that judo fighters exhibited more smiling when winning a medal compared to preliminary matches, and winning fighters smiled more when socially engaging with the audience.

In addition to research examining athletes’ emotional expressions, van Kleef et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that players also made inferences about their team’s performance based on coaches’ emotional expressions. Specifically, athletes who perceived coach anger inferred that their team had performed poorly and they experienced more anger themselves, whereas athletes who perceived coach happiness inferred the team performed well and experienced more happiness. In general, coaches’ expressions of happiness were associated with better team performance, whereas expressions of anger were associated with worse performance. Furthermore, calmer emotional expressions by coaches are associated with more prosocial and less antisocial behaviours among adolescent athletes (Allan & Côté, Citation2016). However, negative emotions of moderate intensity expressed during half-time speeches were subsequently associated with athletes’ greater effort and better team performance (Staw et al., Citation2019). Taken together, emotional expressions have the potential to impact athletes’ cognitions, emotions, behaviours, and performance, and hence may offer avenues to regulate these outcomes.

Individual and contextual influences on the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions

Personality and emotional intelligence

Personality and preferences for emotion regulation have been posited as factors that may influence interpersonal and social aspects of the expression, experience, and regulation of emotions (Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018). However, there has been relatively little research examining these individual factors to date. A notable exception is emotional intelligence, which is defined as ‘the ability to monitor one’s own and others feelings, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and action’ (Salovey & Mayer, Citation1990, p. 189). Emotional intelligence has been studied frequently among coaches (Donoso-Morales et al., Citation2017; Hodgson et al., Citation2017; Lee, Citation2012; Lee & Chelladurai, Citation2016, Citation2018; Mueller et al., Citation2018) and also among supporting staff and administrators within sport organizations (Hings, Wagstaff, Anderson, et al., Citation2018; Wagstaff et al., Citation2012a,b). These studies suggest that high levels of emotional intelligence are valuable for effective and successful coaching and interpersonal relationships in sport. The existing research on emotional intelligence has provided confirming evidence that coaches’ emotional intelligence is associated with greater positive affectivity, lower negative affectivity, and greater genuine expression of emotion (e.g. Lee & Chelladurai, Citation2016).

Norms

Mirroring general emotions research (e.g. Ekman, Citation1973; Hochschild, Citation1979), one major contextual influence on the interpersonal dimensions of emotions in sport is emotion norms, that is, group-specific guidelines which explicate common or expected experiences and expressions and the violation of which entail (social) repercussions.

Cultural Norms. At the most distal level, general cultural norms seem to influence emotional experiences and expressions in sport. For example, runners jointly recovering from injuries suppressed positive emotions if their partners did not share these (Collinson, Citation2005), whereas winning judokas smiled more the more they engaged with the audience (Crivelli et al., Citation2015). Further, Uchida et al. (Citation2009) found that athletes from individualistic cultures (i.e. the U.S.) were expected to, and did, express emotions primarily in relation to the self (e.g. self-focused emotions such as pride), whereas athletes from collectivistic cultures (i.e. Japan) expressed emotions mainly in connection to others (e.g. other-focused emotions such as gratitude), mirroring these cultures’ predominant independent versus interdependent self-construals (Triandis, Citation1995).

Sport-Specific Norms. Despite the applicability of general societal norms, the context of sport also has its own emotion rules. Specifically, it seems that athletes are permitted to express emotions more in a sport context, but only if these convey strength and positivity (Lilleaas, Citation2007). Notably, sport norms dictate that negative responses to injury or feelings of depression in male handball players are generally prohibited (Lilleaas, Citation2007; Mankad et al., Citation2009) and female gymnasts should process their disappointment quickly and in private (Snyder, Citation1990). Coaches too are required to adhere to a ‘culture of excellence’ (Donoso-Morales et al., Citation2017, p. 506) by expressing determination and toughness. Sport-specific norms also appear to guide interpersonal emotion regulation. For example, coaches work to create a culture of excellence in their teams (Donoso-Morales et al., Citation2017) and athletes regulate their teammates’ emotions according to prevalent emotion expression norms such as the avoidance of crying during a competition (Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018).

Regardless of their content, sport-specific norms seem to be set and enforced among athletes and coaches directly, and by sport organizations and outside agents (i.e. fans, the media, and sponsors). With regard to outside agents, social media appears to be a channel by which fans can direct and reinforce athletes’ emotion expressions (Evers, Citation2019; Sanderson, Citation2016). With regard to sport organizations, the particular organizational culture seems to determine its members’ emotional behaviours (Wagstaff et al., Citation2012a,b). For example, the organizational culture determined the salience of gender roles (Vaccaro et al., Citation2011) and a masculine, high-performance climate motivated support staff to exhibit high energy and passion, yet hide experiences of sadness (Hings, Wagstaff, Anderson et al., Citation2018; Hings, Wagstaff, Thelwell et al., Citation2018). Finally, with regard to direct socialization of sport-specific emotion norms, this appears to be a task of veteran athletes and coaches (Sinden, Citation2010; Vaccaro et al., Citation2011), occurs via implicit observation and examination (Sinden, Citation2019), and operates often via punishment of non-conformity, for example, through verbal labelling, loss of status, or exclusion from the team (Mankad et al., Citation2009; Sinden, Citation2010).

Team Norms. At the most proximal level, emotions and emotional behaviours are influenced by the norms within a particular team. For example, team emotion norms can proscribe certain interpersonal regulation behaviours (e.g. prohibition of affect worsening; Campo et al., Citation2017) or the experience and expression of specific (collective) emotions (e.g. fearlessness prior to a match; Gallmeier, Citation1987; Giazitzoglu, Citation2020). Consequently, team emotion norms also guide athletes’ self-regulation and interpersonal emotion regulation efforts towards these target states (Friesen, Devonport, et al., Citation2013; Gallmeier, Citation1987), potentially because non-conformity is also punished at the team level (Giazitzoglu, Citation2020). In addition to these sanctions, intimidation and peer leaders’ emotion expressions appear to set and reinforce descriptive and injunctive emotion norms within a team (e.g. not to express one’s emotions freely, Petitta et al., Citation2015; Tamminen, Palmateer, et al., Citation2016). Nonetheless, current knowledge about the development, content, and consequences of emotion norms at the team level is comparatively limited. This may provide an important avenue for future research, considering, for example, the motivation- and adherence-related costs of experience-expression discrepancies or the use of norms as an avenue to optimize (collective) emotions and intra-team regulatory behaviours. In advancing research and theory on these topics, it is important to consider the interconnectedness of the factors and processes identified herein.

Roles

Emotional expectations also exist at the individual level as part of actors’ role descriptions, that is, the behavioural patterns they are expected to enact in social situations (Eys et al., Citation2019). In sport, expectations regarding the experience and expression of emotion appear to be specified in particular as part of gender, professional, and team roles.

Gender Roles. Gender roles seem to prescribe particular emotional behaviours; specifically, men may be ‘allowed’ to express emotions more in sport than other life domains (Lilleaas, Citation2007). Nonetheless, across sports, these expressions appear limited to displays of hypermasculinity, encouraging aggression and jocularity, yet forbidding expressions of fear, suffering, or affection towards teammates (Giazitzoglu, Citation2020; Lilleaas, Citation2007; Steinfeldt et al., Citation2011; Vaccaro et al., Citation2011). However, the lack of expressed affection among teammates may incur costs for both members and teams (i.e. reduced satisfaction, relatedness, and cohesion; Steinfeldt et al., Citation2011). In addition, there is some initial evidence suggesting that gender might also qualify the extent to which athletes are influenced by the emotions of peer leaders within the team, with females reporting being influenced more by leaders’ emotions than their male counterparts (Cotterill et al., Citation2020).

Professional Roles. The second type of role that seems to stipulate particular emotion-related behaviours is actors’ professional role. For example, both referees and support staff perceived the interpersonal regulation of athletes’ emotions (e.g. down-regulating athletes’ anger, inducing enthusiasm) to be a part of their role responsibilities and necessary to work effectively (Friesen et al., Citation2017; Hings, Wagstaff, Anderson et al., Citation2018; Hings, Wagstaff, Thelwell et al., Citation2018). Athletes too felt that their type of sport dictated certain emotion expressions; for example, the ‘Life Saver image, the ironman image’ (p. 8) that went along with being a surfer demanded the suppression of any negative emotions and the constant display of positivity (Mankad et al., Citation2009).

Team Roles. Finally, the roles actors occupy within a team seem to specify expectations also regarding their experience, expression, and, in particular, the regulation of emotions. The most prominent roles in this context are peer leaders and coaches. For example, coaches feel as if they need to express positive emotions and calmness, and sometimes disappointment but not anger as part of their role (Lee et al., Citation2018). Conversely, a large component of peer leaders’ roles appears to be the effective regulation of their teammates’ emotions (Imholte et al., Citation2019). Accordingly, peer leaders pay particular attention to their teammates’ emotional states (Wolf et al., Citation2018) and engage in interpersonal emotion regulation often and pervasively (Imholte et al., Citation2019; Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018; Wolf et al., Citation2018), for example, to induce role-congruent emotions or ensure optimal member and team functioning (Friesen, Devonport, et al., Citation2013). In addition, leaders’ emotions seem to be especially likely to spread (Cotterill et al., Citation2020; van Kleef et al., Citation2019), potentially due to leaders’ strategic interpersonal emotion regulation or athletes’ social appraisal.

Role attributes besides leadership also seem to qualify athletes’ emotional behaviours. As such, the appropriateness of interpersonal emotion regulation appears to increase with athlete status (e.g. members would not regulate the emotions of a teammate with higher status; Campo et al., Citation2017; Swary, Citation2020). Further, athletes’ playing positions seem to prescribe certain regulatory behaviours such as goalkeepers being mostly removed from intra-team emotion regulation (Friesen et al., Citation2015), the skip on a curling team (i.e. the team’s strategic and tactical decision-maker) being tasked with the most interpersonal regulation (Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013), and substitute players serving calming and supporting roles (Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018). Finally, teammates’ relational closeness appears to qualify interpersonal emotional influence and regulation (Wolf et al., Citation2018) with close friends being the first to congratulate or console an athlete (Snyder, Citation1990) and friends or occupants of similar playing positions regulating each other more frequently (Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018). The idea of emotions constituting a part of team-members’ (formal or informal) role descriptions provides an intriguing avenue for future research when considering how emotions would tie into different aspects of role involvement (e.g. clarity, efficacy, acceptance; Eys et al., Citation2019). In addition, a pressing future research direction would be the inclusion of greater gender diversity in the investigation of (gender) role influences on emotions in sport.

Situational & temporal dynamics

The interpersonal dimensions of emotions in sport are subject to temporal and situational dynamics. First, interpersonal emotion phenomena are dynamic by definition. As such, phenomena such as emotional contagion (Petitta & Jiang, Citation2020; Swary, Citation2020; Weisbuch & Ambady, Citation2008; Wergin et al., Citation2018; Wolf et al., Citation2018) necessarily unfold over time, which can maintain collective team collapse through building anxiety and escalating anger (Wergin et al., Citation2018) or prompt subsequent compensatory regulation (Filho, Citation2020). Similarly, collective effervescence (Cottingham, Citation2012; Faure et al., Citation2014; Stieler & Germelmann, Citation2016; Vargas-Salfate et al., Citation2020; Zumeta et al., Citation2016) is an innately dynamic process characterized by interaction and growing emotionality. Furthermore, because emotions are responses to relevant events (Jones & Uphill, Citation2012), they change if the events change, as well as with changes in individual versus collective construals of actors’ selves and relevant events. Notably, spectators experienced more positive and less negative group-based emotions if their favoured teams performed better in a single match (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Citation2020), across a tournament (Jones et al., Citation2012), or throughout a season (Crisp et al., Citation2007; Wann et al., Citation1994).

Another way in which the interpersonal dimensions of emotions in sport are dynamic relates to the ways in which emotional self- and interpersonal regulation change, and the effectiveness of these strategies depends on context and timing (Friesen et al., Citation2015; Wolf et al., Citation2018). For one, the setting of competition versus non-competition/practice seems to impact both the magnitude and type of athletes’ and coaches’ interpersonal emotion regulation efforts. Specifically, because of the faster pace of competitions, athletes engaged in less interpersonal emotion regulation during as compared to after matches or in practices (Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018). Similarly, during competitions, coaches’ favoured interpersonal emotion regulation strategy was response modulation (i.e. positive reinforcement) whereas during practice it was situation modification (Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019). For another, athletes’ and coaches’ interpersonal emotion regulation seems to change over time: athletes’ efforts to worsen teammates’ affect decreased with an approaching competition whereas their efforts to improve teammates’ affect dropped shortly after a competition (Tamminen et al., Citation2019). In addition, athletes strategically increased the volume and tempo of their locker-room music (to regulate their collective emotions) the closer they came to match time (Swary, Citation2020). Coaches also modify their speeches to invoke different types of regret before, during, and after matches (i.e. regret reduction; Turman, Citation2005, Citation2007). In fact, coaches chose different regret messages during the regular season as compared to the post-season matches (Turman, Citation2005). The time in the season also changed athletes’ emotion regulation with more and better interpersonal emotion regulation and less self-censoring as the team had gotten to know each other better (Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013).

Finally, actors’ self-regulation and interpersonal emotion regulation change in line with emotion norms and emotion-related role descriptions that vary across time and context. Specifically, across a competition day, norms for ice hockey players’ emotions follow a highly scripted routine: calmness and low emotionality prior to warm-up, sustained high-arousal positive emotions during the match, and outcome-appropriate expressions thereafter (Gallmeier, Citation1987). Similarly, rugby players’ masculine gender roles prescribe different emotion expressions depending on time and space with fearlessness being demanded prior to the match, aggressiveness on the field, and jocularity at the pub afterwards (Giazitzoglu, Citation2020). Although the situational and temporal factors influencing the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport have not been the explicit focus within any one particular study, the current review has clearly identified that these emotional phenomena are contextually- and temporally-sensitive and warrant further investigation.

Current issues and future directions

Terminological and conceptual overlap

Overall, we view it as a positive signal that there is a plethora of emotional concepts and phenomena that have been investigated across multiple disciplines of inquiry; yet, one consequence of this approach is the potential for overlap that exists between concepts. We have provided an overview of various definitions and references to affective processes used within the literature to illustrate the similarities and differences in the way these terms and definitions have been used (see ). It remains an important conceptual and theoretical issue to untangle the boundaries, overlap, and hierarchical structure between these concepts, and for researchers to clearly define and operationalize the concepts they are studying. For example, it is not clear at what point emotional self-regulation or intrinsic emotion regulation (Gross & Thompson, Citation2007) is considered to be enacted as emotional labour (Hochschild, Citation1979), and it is also unclear how emotional labour is distinct from interpersonal emotion regulation (Grandey & Melloy, Citation2017). In addition, there is considerable conceptual overlap between collective emotions (Keltner & Haidt, Citation1999; von Scheve & Ismer, Citation1979), emotional contagion (Hatfield et al., Citation1994), and collective effervescence (Durkheim, Citation1965). Similarly, the term interpersonal emotion regulation has been used to refer to deliberate (Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019; Friesen, Devonport, et al., Citation2013; Palmateer & Tamminen, Citation2018; Tamminen, Gaudreau, et al., Citation2016; Citation2019) as well as non-deliberate verbal and nonverbal actions to influence others’ emotions (Tamminen & Crocker, Citation2013), whereas other sources (Campo et al., Citation2017; Gross & Thompson, Citation2007) refer to these actions as extrinsic interpersonal emotion regulation. Confusing matters further, the term interpersonal regulation has also been used to refer to strategies that individuals use to regulate their own emotions by social or interpersonal means (e.g. seeking out the company of others and disclosing emotional experiences to make oneself feel better; Williams et al., Citation2018; Britton & Polman, Citation2022). Finally, some studies have classified or measured emotion regulation strategies based on their general aim (e.g. affect-improving versus affect-worsening; e.g. Tamminen et al., Citation2019) and others as a function of the specific actions (e.g. verbal versus behavioural strategies; e.g. Friesen et al., Citation2015). Thus, one key issue arising from our review is that there is a need for a greater terminological integration and clarity in these areas to avoid perpetuating ‘jingle-jangle’ fallacies and imprecise measurement (see Weidman et al., Citation2017).

Table 3. Overview of interpersonal affective processes or phenomena with examples of various definitions and terms used in the literature.

Dimensions of affective phenomena and areas for future research

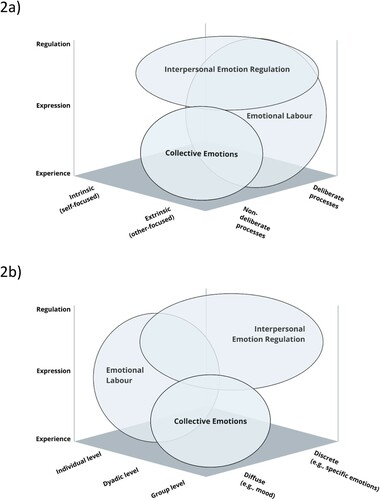

As indicated initially, our focus was on the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions. Across studies, the main social emotional phenomena that sport psychology researchers have addressed are emotional self-regulation in a social context, emotional labour, interpersonal emotion regulation, and collective emotions. Moreover, across studies, it emerged that these phenomena can be mapped and distinguished across four dimensions, namely their focus (internal versus external) and their deliberateness (deliberate versus non-deliberate; see a), as well as their specificity (discrete versus diffuse emotions), and level (individual, dyadic, or group level; see b). For example, interpersonal emotion regulation is generally conceived as a deliberate form of emotion regulation that typically focuses on the regulation of others’ emotions, although a commonly-used measure of interpersonal emotion regulation also assesses emotional self-regulation (Niven et al., Citation2011). Collective emotional processes occupy a different space in the diagrams, as they are non-deliberate and typically concern the experience and expression of emotions, rather than the deliberate regulation of emotions.

Figure 2. Mapping of concepts related to the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport. In a, concepts are presented along dimensions according to the intrinsic or extrinsic focus of the emotional concept/process, and according to whether the emotional process is conceptualized as deliberate or non-deliberate. In b, concepts are presented along dimensions according to the level of the emotional concept/process (individual, dyadic, or group), and according to whether the affective phenomena is considered discrete (e.g. emotions) or diffuse (e.g. moods).

By mapping dimensions of emotional phenomena along these dimensions, it is possible to identify overlap and synergies among phenomena as well as key gaps and areas for future research. From a, it is notable that there has been limited research on non-deliberate intrinsic or extrinsic emotional regulation, as well as research on the regulation of collective emotions. Hence, future research could examine how non-deliberate intrinsic and extrinsic regulatory processes function in sport and how they may impact athletes’ sport performance, and researchers could also examine whether and how collective emotions are regulated in sport contexts. By reviewing b, it is evident that the concepts that have been investigated to date have focused on more diffuse moods rather than on the interpersonal experience, expression, or regulation of specific, discrete emotions (for studies that have examined discrete emotions, see Crisp et al., Citation2007; Furley et al., Citation2015; Ring et al., Citation2019; Staw et al., Citation2019; van Kleef et al., Citation2019).

Need for theoretical development and further phenomenological evidence

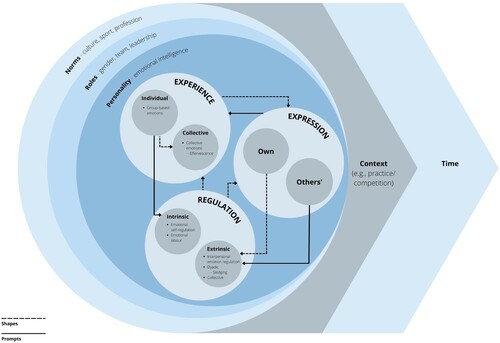

The lack of formal theories has been noted across the psychological sciences (Robinaugh et al., Citation2021), and there is a similar lack of formal, integrative theory for representing and predicting the phenomena related to the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport. This current ‘theory crisis’ (Eronen & Bringmann, Citation2021) results in ‘weak explanations and wide predictions’ (Grahek et al., Citation2021, p. 804) and the study of phenomena without theoretical integration (Borsboom et al., Citation2021). Hence, efforts should be made to rigorously construct, develop, and test theoretical models that explain observed phenomena or behaviours precisely and universally. Approaches for improving theory construction, development, and testing include theory mapping (Gray, Citation2017), theory construction methodology (Borsboom et al., Citation2021), construct validation and computational modelling (Grahek et al., Citation2021), and formal theory (Robinaugh et al., Citation2021). While the integration of interpersonal emotional phenomena into a singular theory is beyond the purpose of this paper, we have provided a diagram () to illustrate the interconnectedness of the concepts studied in this review.

Figure 3. Conceptual model displaying the interconnectedness of interpersonal emotional phenomena. The central three circles contain concepts related to the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions, which are influenced by factors such as personality, roles, norms, and culture. These processes are influenced by contextual factors related to practice or competition and are also dynamic and change over time.

The results herein provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on the research conducted to date and a map of the constructs and theories used (Gray, Citation2017), which may be a first step toward more concerted efforts to develop an integrated theory of interpersonal emotional processes in sport. For example, using theory construction methodology (Borsboom et al., Citation2021), researchers would first identify empirical phenomena that are the intended target of explanation; the present review may serve to fulfil this step. Subsequently, researchers would develop a prototheory and theoretical principles that aim to explain the phenomena of interest; these are then used to develop a formal model, and the explanatory adequacy of the model is investigated and the overall adequacy of the theory is evaluated. An alternative method, theory mapping, provides guidance on synthesizing studies and developing theories (Gray, Citation2017): first, associations between constructs are identified, followed by explanation of moderating factors and identification of fundamental elements of the theory. Next, theory mapping identifies varieties or examples of fundamental elements, and numbers and notes are used to provide supplemental details and explanations.

In addition to theory-building and theory-testing, there continues to be value in conducting programmatic research (cf. Zanna & Fazio, Citation1982) to develop further phenomenological evidence for the concepts identified in this review, and to accumulate evidence to account for how these effects work (e.g. mediating processes) and the conditions under which they operate (e.g. boundary conditions and moderating processes). In this review, we have noted several areas for future research pertaining to the phenomena that have been investigated to date.

Need for research among additional populations

Another key issue in advancing our understanding of the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport is the investigation of additional populations with greater diversity in participants’ gender, age or developmental stage, culture, and other socio-demographic backgrounds. There has been limited research examining the experiences of female athletes; consequently, there has been little opportunity to explore potential gender differences. One recent exception is a study by Cotterill et al. (Citation2020) thatprovided evidence that female athletes are more likely to report being influenced by the emotions of leaders on their teams. This finding provides a useful point of departure for examining possible reasons why female athletes may be influenced more strongly by the emotional expressions of leaders within their teams and the possible implications for these results. Additionally, researchers have not examined differences between female athletes with male coaches compared to female athletes with female coaches, although participants’ reports indicate that coaches’ emotional expressions may have different effects depending on their gender (Braun & Tamminen, Citation2019). Thus, some gaps remain in the literature concerning the potential consequences of male and female athletes’ reactions to the emotional expressions and regulatory efforts of male and female coaches and leaders, as well as the norms and role expectations that may influence these effects. A similar limitation of the research conducted to date is that it has focused primarily on adult populations. Adopting a developmental perspective would be useful to consider young athletes’ developing socio-emotional capacities, coaches and parents’ modelling of emotional expressions, the socialization of emotion regulation strategies, and the development of emotional norms in sport.

Need for applied research

There has been limited applied or intervention research conducted thus far, and while more basic research is needed to develop a strong foundation for making applied recommendations, we feel there are some particularly fruitful avenues for conducting applied sport psychology research. First, it may be valuable to determine whether athletes’ emotional self- and interpersonal regulatory capacities can be enhanced or developed through intervention research (e.g. what are the best ways of enhancing athletes’ capacity for interpersonal emotion regulation in sport?). A second focus could be on coach education and training regarding the impact of emotion expressions on athletes’ performance and their regulation of athletes’ emotions. Third, related to this, applied research is needed to determine best approaches for harnessing functional collective emotions (of athletes, but also among fans), and strategies to stop the spread of dysfunctional collective emotions (e.g. which collective states are helpful for which outcomes and in which situations, and who can best stop unhelpful emotions from transferring among teammates?).

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to provide a comprehensive scoping review of the literature related to the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport. Due to the interconnectedness of these emotion-related phenomena, we sought to include research on topics such as collective emotions, group-based emotions, the impact of emotion expressions on others, and interpersonal emotion regulation. The current paper provides a comprehensive overview of the studies that have been conducted to date, a map of these phenomena across pertinent dimensions (see ) and a conceptualization of the interconnectedness of these phenomena (), and directions for future research. Key issues identified in this review include the need for theoretical integration of concepts and programmatic research to systematically examine the processes and effects of the interpersonal experience, expression, and regulation of emotions in sport; better terminological clarity across studies; an acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of these emotional phenomena; a need for more research with additional populations (e.g. youth athletes, female athletes, etc.); and a need for applied research and intervention in sport settings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Funding

References

- *Allain, J., Bloom, G. A., & Gilbert, W. D. (2018). Successful high-performance ice hockey coaches’ intermission routines and situational factors that guide implementation. The Sport Psychologist, 32(2), 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2017-0088

- *Allan, V., & Côté, J. (2016). A cross-sectional analysis of coaches’ observed emotion-behavior profiles and adolescent athletes’ self-reported developmental outcomes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(3), 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1162220

- Ashforth, B., & Humphrey, B. (1993). Emotional labour in service roles: The Influence of Identity. Academy of Management Review,18(1): 88–115. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1993.3997508

- Balk, Y. A., Adriaanse, M. A., De Ridder, D. T., & Evers, C. (2013). Coping under pressure: Employing emotion regulation strategies to enhance performance under pressure. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35(4), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.35.4.408

- Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094912

- *Braun, C. (2017). Coaches’ interpersonal emotion regulation and the coach-athlete relationship (Publication No. 10622246). [Master's thesis, University of Toronto]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- *Braun, C., & Tamminen, K. A. (2019). Coaches’ interpersonal emotion regulation and the coach-athlete relationship. Movement & Sport Sciences - Science & Motricité, 105(105), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1051/sm/2019011

- Britton, D., & Polman, R. (2022). Validation of the interpersonal regulation questionnaire in sports: Measuring emotion regulation via social processes and interactions. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2022.2089197

- Borsboom, D., van der Maas, H. L., Dalege, J., Kievit, R. A., & Haig, B. D. (2021). Theory construction methodology: A practical framework for building theories in psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 756–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620969647

- Butler, E. A., & Gross, J. J. (2009). Emotion and emotion regulation: Integrating individual and social levels of analysis. Emotion Review, 1, 86–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073908099131

- *Campo, M., Champely, S., Louvet, B., Rosnet, E., Ferrand, C., Pauketat, J. V. T., & Mackie, D. M. (2019). Group-based emotions: Evidence for emotion-performance relationships in team sports. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 90(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2018.1563274

- *Campo, M., Mackie, D., Champely, S., Lacassagna, M., Pellet, J., & Louvet, B. (2019). Athletes’ social identities: Their influence on precompetitive group-based emotions. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 41(6), 380–385. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2018-0282

- Campo, M., Mackie, D., & Sanchez, X. (2019). Emotions in group sports: A narrative review from a social identity perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00666

- *Campo, M., Matinent, G., Pellet, J., Boulanger, J., Louvet, B., & Nicolas, M. (2018). Emotion-performance relationships in team sport: The role of personal and social identities. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 13(5), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954118785256

- *Campo, M., Sanchez, X., Ferrand, C., Rosnet, E., Friesen, A., & Lane, A. M. (2017). Interpersonal emotion regulation in team sport: Mechanisms and reasons to regulate teammates’ emotions examined. International Journal of Sport and Exercise, 15(4), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2015.1114501

- *Chang, M. J., Joon-Ho, K., Yong, J. K., & Connaughton, D. P. (2017). The effects of perceived team performance and social responsibility on pride and word-of-mouth recommendation. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 26(1), 31–41.

- *Cheshin, A., Heerdink, M. W., Kossakowski, J. J., & van Kleef, G. A. (2016). Pitching emotions: The interpersonal effects of emotions in professional baseball. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00178

- Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 34(3), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.3.366

- Collins, R. (2004). Interaction ritual chains. Princeton University Press.

- *Collinson, J. A. (2005). Emotions, interaction and the injured sporting body. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 40(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690205057203

- *Cotterill, S. T., Clarkson, B. G., & Fransen, K. (2020). Gender differences in the perceived impact that athlete leaders have on team member emotional states. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(10), 1181–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1745460

- *Cottingham, M. D. (2012). Interaction ritual theory and sports fans: Emotion, symbols, and solidarity. Sociology of Sport Journal, 29(2), 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.29.2.168

- *Crisp, R. J., Heuston, S., Farr, M. J., & Turner, R. N. (2007). Seeing red or feeling blue: Differentiated intergroup emotions and ingroup identification in soccer fans. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207071337

- *Crivelli, C., Carrera, P., & Ferandez-Dols, J. (2015). Are smiles a sign of happiness? Spontaneous expressions of judo winners. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.08.009

- *Davis, P. A., Davis, L., Wills, S., Appleby, R., & Nieuwenhuys, A. (2018). Exploring “sledging” and interpersonal emotion-regulation strategies in professional cricket. The Sport Psychologist, 32(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2017-0078

- *Donoso-Morales, D., Bloom, G. A., & Caron, J. G. (2017). Creating and sustaining a culture of excellence: Insights from accomplished university team-sport coaches. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 88(4), 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2017.1370531

- Doron, J., & Martinent, G. (2021). Dealing with elite sport competition demands: An exploration of the dynamic relationships between stress appraisal, coping, emotion, and performance during fencing matches. Cognition and Emotion, 35(7), 1365–1381. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.1960800

- Durkheim, E. (1965). The elementary forms of religious life. The Free Press.

- Durkheim, E. (1976). The elementary forms of the religious life. Routledge.

- Ekman, P. (1972). Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotions. In J. Cole (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1971, Vol. 19. (pp. 207–283). University of Nebraska Press.

- Ekman, P. (1973). Darwin and facial expression: A century of research in review. Academic Press.

- Elias, N. (1991). On human beings and their emotions: A process-sociological essay. In M. Featherstone, M. Hepworth & B. S. Turner (Eds.), The body: Social process and cultural theory (pp. 103–25). Sage.

- Eronen, M. I., & Bringmann, L. F. (2021). The theory crisis in psychology: How to move forward. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620970586

- *Evers, C. W. (2019). The gendered emotional labor of male professional ‘freesurfers’ digital media work. Sport in Society, 22(10), 1691–1706. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1441009

- Eys, M., Bruner, M. W., & Martin, L. J. (2019). The dynamic group environment in sport and exercise. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 42, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.001

- *Faure, C., Appleby, K. M., & Ray, B. (2014). Feeling elite: The collective effervescence of TEAM USA at the 2012 ITU World Triathlon Grand Final. The Qualitative Report, 19(9), 1–22. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss9/1.

- Filho, E. (2019). Team dynamics theory: Nomological network among cohesion, team mental models, coordination, and collective efficacy. Sport Sciences for Health, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-018-0519-1

- *Filho, E. (2020). Shared zones of optimal functioning (SZOF): A framework to capture peak performance, momentum, psycho-bio-social synchrony and leader-follower dynamics in teams. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 14(4), 330–358. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2019-0054

- Fischer, A. H., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2008). Social functions of emotion. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 456–468). The Guilford Press.

- *Friesen, A. P. (2013). “Catching” emotions: Emotion regulation in sport dyads (Publication No. 27812157). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wolverhampton]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Fridlund, A. J. (1994). Human facial expression: An evolutionary view. Academic Press.

- *Friesen, A. P., Devonport, T. J., & Lane, A. M. (2017). Beyond the technical: The role of emotion regulation in lacrosse officiating. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(6), 579–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1180419

- *Friesen, A. P., Devonport, T. J., Sellars, C. N., & Lane, A. M. (2013). A narrative account of decision-making and interpersonal emotion regulation using a social-functional approach to emotions. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.773664

- *Friesen, A. P., Devonport, T. J., Sellars, C. N., & Lane, A. M. (2015). Examining interpersonal emotion regulation strategies and moderating factors in ice hockey. Athletic Insight, 7(2), 143–160. http://www.novapublishers.org/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=57282.

- Friesen, A. P., Lane, A. M., Devonport, T. J., Sellars, C. N., Stanley, D. N., & Beedie, C. J. (2013). Emotion in sport: Considering interpersonal regulation strategies. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.742921

- *Friesen, A. P., Stanley, D., Devonport, T., & Lane, A. M. (2019). Regulating own and teammates’ emotions prior to competition. Movement & Sport Sciences - Science & Motricité, 3(105), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1051/sm/2019014

- Frijda, N. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge University Press.

- Furley, P. (2021). The nature and culture of nonverbal behavior in sports: theory, methodology, and a review of the literature. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1894594

- *Furley, P., Moll, T., & Memmert, D. (2015). Put your hands up in the air"? The interpersonal effects of pride and shame expressions on opponents and teammates. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1361. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01361

- Gabriel, A. S., Acosta, J. D., & Grandey, A. A. (2013). The value of a smile: Does emotional performance matter more in familiar or unfamiliar exchanges? Journal of Business & Psychology, 30(1), 37–50.

- *Gallmeier, C. P. (1987). Putting on the game face: The staging of emotions in professional hockey. Sociology of Sport Journal, 4(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.4.4.347