ABSTRACT

Research indicates sport psychology practitioners vary in their abilities to help athletes. Understanding the characteristics of helpful practitioners can inform applied sport psychology training. We reviewed qualitative research on stakeholders’ perceptions of the characteristics of practitioners. The electronic and manual search yielded 33 studies, with extracted data being subject to an abductive analysis. We also critically appraised the studies according to criteria listed by the Cochrane Collaboration. Results indicated that stakeholders perceived that helpful practitioners were able to (a) build rapport or interpersonal bonds with athletes, (b) develop real relationships based on openness and realistic perceptions, (c) inspire hope and suitable expectations, (d) promote engagement in the change process, and (e) operate well in the contexts where clients are located. The critical appraisal indicated that the studies provide an informed representation of stakeholders’ perceptions, but also where research may improve, such as considering the researcher-participant relationship. The review points to avenues of future research, such as experiments testing if the characteristics stakeholders believe describe helpful practitioners lead to better client outcomes. The current findings can also inform the training, supervision, and continued professional development of trainees and practitioners.

Whereas some athletes and coaches have reported benefits from working with sport psychology practitioners, other performers have suggested that their consultants were unhelpful (Anderson et al., Citation2004). Researchers in other helping professions, such as counselling or clinical psychology, have also revealed that practitioners vary in their helpfulness and have searched for the characteristics of effective professionals (Castonguay & Hill, Citation2017). To date, sport psychology investigators have not conducted experiments to determine the practitioner characteristics associated with helpful service delivery. Instead, they have explored stakeholders’ perceptions of the characteristics of helpful and unhelpful practitioners (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation2004). Further, few researchers have attempted to synthesize the research to advance theory, assess the rigour of the studies underpinning the knowledge, identify a research agenda, or develop empirically-based applied implications.

In applied sport psychology, research has focused on assessing the efficacy of interventions designed to help athletes, rather than the individuals delivering those techniques. For example, whereas enough studies examining the influence imagery has on sport performance exist to allow multiple meta-analyses to be conducted (Simonsmeier et al., Citation2021), the same is not true for the influence of practitioners on athletes. Nevertheless, psychological strategies do not inevitably improve performance and practitioners need to use them carefully and judiciously (Weinberg & Williams, Citation2021). For example, helpful practitioners understand how to tailor interventions to benefit athletes (Simons & Andersen, Citation1995), illustrating one way that practitioners influence applied sport psychology processes and outcomes (Poczwardowski, Citation2019).

Although less research on practitioners exists, compared to the interventions they use, investigators have produced studies across a diverse range of topics, including practitioner self-care (Quartiroli, Etzel, et al., Citation2019), quality of life (Quartiroli, Knight, et al., Citation2019), professional identity (Quartiroli et al., Citation2021), self-awareness (Winstone & Gervis, Citation2006), sexual attraction between clients and practitioners (Stevens & Andersen, Citation2007), and professional development (McEwan et al., Citation2019). Within the research focused on practitioners, investigators have most commonly explored stakeholders’ perceptions of the characteristics of helpful or desirable practitioners, including physical, demographic, psychological, and interpersonal attributes (e.g. Woolway & Harwood, Citation2019). For example, when reviewing the attributes that influence athletes’ likelihood to seek sport psychology assistance, Woolway and Harwood (Citation2020) concluded that the preferred practitioner was the same gender, race, and age as the client. Further, the ideal practitioner: (a) had an athletic background; (b) had sport-specific knowledge; (c) had strong interpersonal skills; (d) had an athletic, lean physique; (e) was physically active; (f) had either a postgraduate degree or was certified; and (g) had experience working with different client-groups.

Woolway and Harwood (Citation2020) focused on the attributes that influence a person’s decision to seek assistance. Athletes, however, may not always believe they have a choice or that they have a range of candidates from which they can select an individual, such as when the practitioner is an employee of the team or national governing body. Also, the attributes that influence a client’s decision to seek services may differ from those characteristics that athletes perceive influence a practitioner’s helpfulness once the two parties have begun collaborating. Although Woolway and Harwood’s (Citation2020) review contributes to knowledge, one way to extend their work is to synthesize research examining athletes’, coaches’, and other stakeholders’ beliefs about the characteristics of helpful practitioners.

Among the earliest studies on stakeholders’ perceptions of practitioner characteristics were those Orlick and Partington published in the late 1980s (e.g. Orlick & Partington, Citation1987; Partington & Orlick, Citation1987). Since these seminal works, investigators have produced a growing body of research in which they have sampled a range of participants, including athletes, coaches, parents, sport science support staff, sports medicine experts, and sport psychology practitioners (e.g. Chandler et al., Citation2016; Sharp et al., Citation2015). Although research exists, there have been few attempts to synthesize the studies. In an early review, for example, Tod and Andersen (Citation2005) suggested that helpful sport psychology practitioners had good interpersonal skills and technical competence. In a more recent review, Fortin-Guichard et al. (Citation2018) stated that (a) athletes thought practitioners should be positive, friendly, informal, trustworthy, flexible, and good communicators; and (b) coaches believed practitioners should be knowledgeable about the sport, trustworthy, good listeners, and able to integrate into the team’s culture. Fortin-Guichard et al.’s (Citation2018) review included more than a focus on effective practitioner characteristics. They also surveyed studies on practitioners’ professional experiences and athletes’ attitudes towards applied sport psychology. Given the breadth of their review, they were unable to give the investigations on stakeholders’ perceptions the coverage or depth that would be possible in a review with a narrower focus. Further, they reviewed research prior to 2015 and investigators have since published numerous studies. One way to extend Fortin-Guichard et al.’s (Citation2018) work is to review research on the topic from its inception to the present day.

For this review, we made three additional decisions to help ensure the current work advanced knowledge. First, we adopted a systematic review methodology to ensure transparency and to assess the quality of the evidence underpinning the research. Previous reviews have seldom been systematic or transparent, meaning it is difficult for readers to evaluate the methods reviewers used to find, examine, and synthesize the relevant studies. Also, as part of the systematic approach, we included a critical appraisal of the studies to assess the level of confidence readers can have in the evidence, a feature missing in previous reviews.

Second, we focused on qualitative studies because they dominate the literature on stakeholders’ perceptions of helpful practitioner characteristics and researchers have not yet reviewed them systematically or in their entirety. Also, prior to conducting this review, we knew that these qualitative investigations appear across a range of academic journals and sources, both inside and outside the typical scientific publishing channels. Single qualitative studies published across a range of sources, in the absence of systematic review, can produce fragmented knowledge (Holt et al., Citation2017). Results of qualitative studies must be analysed, integrated, and synthesized in a systematic and transparent fashion to expand a knowledge base and provide a foundation for informing evidence-based practice (Erwin et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, because individual qualitative studies often have small and homogenous samples, synthesis can produce findings with greater transferability than those arising from individual studies themselves (Estabrooks et al., Citation1994).

Third, we drew on theories to help us consider how we could synthesize the results across the research to offer a novel and broad perspective through which to understand stakeholders’ perceptions. Currently, most work in sport psychology has been atheoretical (e.g. Tod, Citation2017), and we drew on theories from counselling psychology, including Rogers' (Citation1959) Person-Centred Therapy, the Stages of Change Model (Prochaska et al., Citation2015), Poczwardowski et al.’s (Citation2004) practice philosophy pyramid, and Wampold and Ulvenes' (Citation2019) contextual model.

Beyond theoretical advancement, a review of the qualitative research on stakeholders’ perceptions of helpful practitioner characteristics has applied implications. For example, synthesizing the research may provide information to help trainees and other practitioners reflect on their strengths and areas for improvement and stimulate professional development. Educators and supervisors might use the findings from the current research to enhance their interactions with students and supervisees. Professional organizations may reflect on the findings from this review when designing, delivering, and evaluating practitioner education pathways and vocational qualifications. The findings may also allow comparison with expertise literature from similar professions (e.g. counselling) and contribute to an interdisciplinary knowledge base about the helping professions.

In this study we reviewed and synthesized qualitative investigations exploring the characteristics of helpful sport and exercise psychology practitioners. The review purpose adhered to the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomena of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research Type; Cooke et al., Citation2012) acronym to ensure we created a specific, feasible, and suitable objective. Our specific purpose was to explore stakeholders’ (Sample; e.g. athletes, coaches, practitioners, administrators, sport science support staff) views (Evaluation) about helpful sport and exercise psychology practitioner characteristics (Phenomena of Interest), emerging from qualitative data collection techniques (Design), used in naturalistic descriptive research (Research Type).

Method

Situating the authors

The analysis of qualitative data and research includes subjective interpretations, and we acknowledge we were not objective or neutral (Denzin, Citation2017). We present our backgrounds and epistemological stances to help readers appreciate the influences on our interpretive insights (Middleton et al., Citation2020). Regarding epistemology, we subscribe to a social constructivist viewpoint (Sandu & Unguru, Citation2017). The understanding we present on stakeholders’ perceptions of helpful practitioner characteristics emerged from the interactions among the studies reviewed, our backgrounds, and the various theories that sensitized our thinking. Further, we believed that these interactions and our critical appraisal of the research findings and process, allowed new insights to surface that could advance theory and guide the training of practitioners.

Regarding our backgrounds, we are of western European descent with two of us working in The United Kingdom and one in India. All three of us have extensive experience working in elite sport; two as sport psychology practitioners and one as an exercise physiologist and a director of sport science support. These applied experiences have shaped our view of applied sport psychology and the benefits practitioners offer athletes. SP offered a unique perspective on the topic because of a background as a physiologist and sport science director who has worked with and observed sport psychology practitioners rather than having performed the role. SP and DT have also worked across multiple continents (e.g. India, Middle East, Europe, and Oceania) and have experienced ways that psychology varies when integrated into different support systems. These different perspectives among the team allowed us to explore and appraise our insights. In addition to their extensive consulting experience as sport psychology practitioners, ML and DT are also in academic roles in which they supervise trainee practitioners and conduct research on applied sport psychology topics. These roles gave ML and DT knowledge that informed their interpretations of the research. The three authors have expertise in conducting systematic reviews, as evidenced by having published more than twenty collectively.

As an example of how our backgrounds influenced our interpretations, during the review process, a reviewer observed that our examples were often behavioural characteristics. On reflection, this tendency emerged because of our desire to produce results that have applied value and could help trainees and practitioners do something to enhance the relationships they forge with athletes and increase their helpfulness. The reviewer’s observation let us to reflect on our tendencies to ensure we were still synthesizing the literature in a fair way, rather than forcing it to fit a preconceived idea; that is, were we making a genuine attempt to engage in abductive reasoning (see below)?

Electronic search

Inclusion criteria

Included studies had to have (a) contained original empirical research, (b) reported non-numerical data generated from a qualitative method, (b) examined participants’ perceptions about the attributes of helpful sport psychology practitioners, and (c) occurred within a sport context. Excluded studies displayed at least one of the following criteria: (a) they did not describe original empirical research, (b) they only contained numerical data, (c) they did not examine perceptions of helpful sport psychology practitioners’ attributes, or (d) they occurred in non-sport contexts. Mixed methods studies contributed to the review if we could extract qualitative data separately from quantitative data. Sources included both peer-reviewed journal publications and other documents, such as theses, conference presentations, and book chapters if they met the above criteria and we could obtain full-text copies.

Search terms and strategy

The electronic databases included: Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, PsychINFO, PsychARTICLES, and Scopus. We also used Open Grey to identify relevant research existing outside typical scientific dissemination channels. A scoping exercise helped us generate search terms which we then arranged into a search strategy based on the SPIDER acronym. For the scoping exercise, pearl growing helped us generate search terms (Booth et al., Citation2016). To start, we read a recent well-cited paper that met the inclusion criteria (Sharp et al., Citation2015) to identify search terms. Then, we reviewed that paper’s reference list to obtain other papers meeting the inclusion criteria. From reading these papers we added search terms to the list. Once we had read ten papers no more search terms emerged. Pearl growing let us identify empirically based search terms rather than rely on our own perceptions (Booth et al., Citation2016). We arranged these key terms according to the SPIDER acronym to determine the search strategy outlined as such (along with Boolean operators):

Sample: No key terms inserted because we did not restrict the search to specific types of stakeholders, AND

Phenomenon of Interest: consultant character* OR practitioner character* OR consultant effective* OR practitioner effective* OR consultant style OR practitioner style OR sport psychol* character* OR sport psychol* effective* OR sport and exercise psychol* character* OR sport and exercise psychol* effective* OR consulting relationship OR sport psychol* alliance OR practitioner-athlete relationship AND

Design: No key terms inserted because we did not restrict the search according to design, AND

Evaluation: No key terms inserted because we did not restrict the search according to Evaluation, AND

Research Type: We used database filters to limit records to qualitative research were possible

The scoping exercise finished with us pilot-testing the search strategy to ensure a feasible balance between breadth and sensitivity (Booth et al., Citation2016).

Manual search

We also conducted a backward search by reviewing the reference lists of included studies. Further, a journal table of contents search occurred, and we reviewed the following journals: The Sport Psychologist; The Journal of Applied Sport Psychology; Psychology of Sport and Exercise; Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology; Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology; International Journal of Sport Psychology; International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology; Journal of Sport Psychology in Action; Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology; Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology; Sport and Exercise Psychology Review.

Study screening and selection

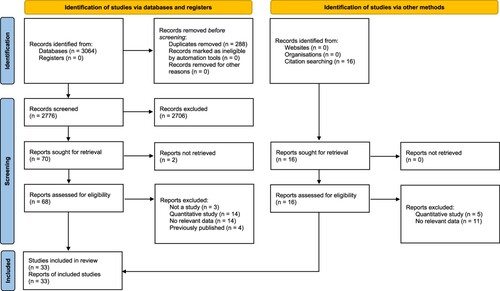

The results from each database search were stored in a single Endnote library prior to being screened. On completion of the database searches, we used Endnote to remove duplicate records. After deleting duplicates, we screened the remaining records by their titles and abstracts, removing records that clearly failed to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. During the search, we also separated out records that discussed the same data, such as when students published articles from their theses. The remaining articles were subject to a full text review and reasons for excluding studies noted. Two people undertook the full text review and differences were resolved through discussion. The articles left after the full text review were included in the current project. presents a flowchart of the search.

Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis

An abductive approach guided data extraction, analysis, and synthesis (Collins & Stockton, Citation2018). Abductive reasoning seeks a situational fit between data and theory (Timmermans & Tavory, Citation2012).

Step 1. We entered data into Microsoft Excel, with each row representing a study and each column a data item. When an article contained multiple studies, we entered each investigation into separate rows. Columns existed for:

Author, year, source, and country of origin

Participant sex, age, and type (athlete, coach, practitioner, etc.)

Data collection and data analysis method

Relevant findings

Step 2. We grouped study findings to generate clusters of information (e.g. relationship factors, interventions, etc.). As clusters emerged, we assessed the degree that findings within clusters were like each other (homogeneity), yet different to findings in other clusters (heterogeneity; Patton, Citation2015). We recorded each cluster into new Excel spreadsheet columns.

Step 3. We reflected on how clusters might be synthesized considering current knowledge. Specifically, we explored how well different theories helped us synthesize the clusters in a meaningful and coherent fashion. To avoid overfitting the data to a single framework, we examined the emerging findings against several theories. Examples included Rogers' (Citation1959) Person-Centred Therapy, the Stages of Change Model (Prochaska et al., Citation2015), Poczwardowski et al.’s (Citation2004) practice philosophy pyramid, and Wampold’s (e.g. Wampold & Ulvenes, Citation2019) contextual model.

Step 4. To assess the emergent clusters, we considered the following questions: do they make sense given current knowledge? Are there enough data to support their inclusion? Does the synthesis make a coherent framework? Do the review findings add something to the discipline? In what ways can the review synthesis help practitioners?

Step 5. Writing the results provided a further test. Two experienced peers read drafts of the results providing feedback that helped us decide how well we had answered the above questions. Although presented linearly, we moved among steps 3–5 as needed to adjust clusters to best capture a coherent fit between data and theory (Timmermans & Tavory, Citation2012).

A central feature of abductive reasoning is that researchers’ own knowledge and experience influence their interpretations of a review’s findings (Timmermans & Tavory, Citation2012). Integrating qualitative research involves subjective decision-making, not adherence to objective criteria (Paterson et al., Citation2001). The synthesis below reflects our interpretation of the major findings; one influenced by our understanding of the broader literature on the helping professions. To enhance transparency, we have presented details about ourselves above and we have cited literature that influenced our thinking to show the links we perceived between the findings from the reviewed studies and the broader knowledge on helping relationships. The synthesis is not the only possible interpretation, but one we offer to stimulate debate, inspire research, and generate improved understanding of the topic.

Critical appraisal of research

For the critical appraisal, we assessed the reviewed studies against the criteria contained in the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme’s (CASP) checklist for qualitative research (casp-uk.net). The checklist items map onto the criteria listed by the Cochrane Collaboration for appraising qualitative research (Noyes et al., Citation2022). Specifically the items included: (a) the clarity of the research question, (b) the suitability of a qualitative approach, (c) the adequacy of the research design to answer the question, (d) the recruitment of suitable participants, (e) the adequacy of the data collection methods, (f) the consideration of the relationship the researchers had with the participants, (g) consideration of the influence of ethical principles on the study, (h) the rigorousness of the data analysis, (i) the clarity of the findings, and (j) the contribution to local knowledge. Systematic reviewers do not agree on a gold standard set of criteria by which to assess qualitative evidence. They do agree, however, that reviewers need to critically appraise qualitative studies to help readers evaluate the rigorousness of the research underpinning the results (Noyes et al., Citation2022). More than 100 critical appraisal tools exist for qualitative research, yet there is little consistency among them, and few have been tested for their adequacy (Munthe-Kaas et al., Citation2019). In this review, two reasons underpinned the use of the CASP checklist. First, the CASP checklists have been subject to testing so evidence for their use exists. Second, the checklist items map onto the criteria listed by the Cochrane Collaboration as being suitable for assessing methodological rigour, rather than factors representing the more nebulous concept of quality (Noyes et al., Citation2022).

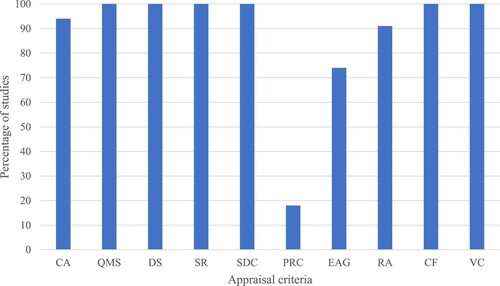

In conducting the critical appraisal, we constructed a table in which we assessed each study (listed by row) against each of the CASP criteria (listed by column). For each study, we summarized our assessment for each criterion as: satisfied, unable to tell, or not satisfied. We did not aggregate the assessment or generate a total score. Instead, we have included a bar chart () in which we have outlined the percentage of studies satisfying each criterion. The critical appraisal table is available to view on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/u4zhp) and not in the current article, because although interesting, the bar chart () has greater relevance for the review. The value of a critical appraisal is not in labelling individual studies (e.g. as good quality, bad quality, weak, strong, etc.), but in identifying the typical strength and weaknesses across a body of research. As such the bar chart is more informative than the table, although interested readers can access the table via the OSF (https://osf.io/u4zhp). The bar chart informed our reflection on the findings and helped us determine some avenues of future research.

Figure 2. Percentage of studies meeting each critical appraisal criterion.

Note: CA = clear aims, QMS = qualitative method suitability, DS = design suitability, SR = suitable recruitment, SDC = suitable data collection, PRC = participant relationship considered, EAG = ethical approval granted, RA = rigorous analysis, CF = clear findings, VC = valuable contribution.

Results

Summary of literature search

summarizes the electronic and manual search. The database search returned 3064 records, from which we removed 288 duplicates. Title and abstract screening reduced the remaining 2776 records to 70 that were subjected to a full text review. We could not retrieve 2 records but performed a full text review on 68 papers. The final sample consists of 33 studies, with the other 35 being excluded (with reasons given in ). Although 16 records emerged from the manual search, no additional studies were included in the final sample.

Study characteristics

We present the characteristics of the final sample of studies in , including country of origin (as determined by the lead author’s affiliation), participants, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and design (cross-sectional or longitudinal). A table containing the major findings from the included studies is available to view at the OSF (https://osf.io/u3vbh). We have made this table available on the OSF because its length will disrupt the reader’s flow through this review report.

Table 1. Design features of the included studies.

Country of origin

Regarding country of origin, 16 studies have come from the United Kingdom, 8 from the USA, 5 from New Zealand, 4 from Canada, and 1 from Australia. All studies have originated from affluent, individualistic societies in Western and industrialized countries.

Participants

Researchers have included 694 participants in their studies, of which 405 were males (58%), 163 were females (23%) and 126 were undisclosed (19%). Of the participants, 272 have been athletes (39%), 257 practitioners (37%), 107 coaches (15%), and 58 others (parents, physicians, support staff, administrators; 9%). Further examination of participants is hindered by a lack of sufficient reporting in the studies cited (e.g. there are insufficient details reported for ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender beyond a dichotomous female/male split).

Data collection, data analysis methods, and research design

Across the studies, investigators have collected data via interviews (n = 30, 91%), surveys (n = 4, 12%), focus groups (n = 2, 6%), field notes (n = 1, 3%) and diaries (n = 1, 3%). The sum of the percentages is greater than 100 because researchers have sometimes adopted multiple data collection methods within a study. Regarding data analysis methods, researchers describe their methods as content analysis/thematic content analysis (n = 17, 52%), inductive content analysis (n = 8, 24%) Interpersonal Phenomenological Analysis (n = 3, 9%), Narrative Analysis (n = 1, 3%), Consensual Qualitative Research analysis (n = 1, 3%), Grounded Theory (n = 1, 3%), Interpretational Qualitative Analysis (n = 1, 3%), and Reflexive Thematic Analysis (n = 1, 3%). Finally, 31 studies adopted a cross-sectional design, and two investigations were longitudinal.

Critical appraisal results

presents the results of the critical appraisal and reveals that readers can have confidence that the reviewed studies provide clear, useful, and informed insights into the phenomenon of interest: stakeholders’ perceptions of the characteristics of helpful practitioners. Most studies (and in several instances all) satisfied the bulk of criteria, such as having clear aims, relevant research methods, and suitable participants (see ). There was one criterion, however, against which over 80% failed: consideration of the influence that the researcher-participant relationship had on the findings. The relationship researchers have with participants can influence the data collected, both positively and negatively (Andersen & Ivarsson, Citation2016). For example, when researchers, who are also notable practitioners, interview colleagues, especially trainees, interpersonal dynamics may prevent participants from sharing pertinent information. As another example, trainees who interview highly respected, well-known practitioners may refrain from exploring some avenues due to power differentials between colleagues of different standings. Equally, high quality data may also emerge in these instances, and it would help readers evaluate the findings from a study if the researchers reflected on the relationships they shared with participants, along with their positionality.

The critical appraisal also helps define the boundaries of the research findings. The studies examined stakeholders’ perceptions and did not assess or measure the characteristics directly. For example, the studies showed that participants believe that empathy is a characteristic of helpful practitioners. Such a finding, however, does not demonstrate that empathy is associated with service delivery processes or outcomes. Experimental research will help answer such a question.

As we carried out the critical appraisal, it became clear that researchers had reflected on their work and identified strengths and limitations. Researchers had critically appraised their own studies. In some ways, however, researchers have undersold their findings because they have often applied quantitative criteria when evaluating their qualitative studies. For example, a frequent self-criticism was a small sample size and the lack of generalizability. The relationship between sample size and generalizability reflects quantitative thinking and is not always a relevant criterion by which to evaluate qualitative research. Instead, often the extent to which findings from a qualitative study are transferable is influenced by the (a) level of rich description and conceptual thought about the study’s findings, context, and participants and (b) the assessment of the similarities and differences between the study’s context and other situations (Smith, Citation2018). The findings across the reviewed studies may be more transferable than the researchers realized, but the decision is for readers to make.

Synthesis of the major findings

This section presents the synthesis of the major findings from the research. The synthesis describes five clusters of characteristics that allow practitioners to assist athletes, based on the recognition that applied sport psychology is a co-constructed social process. The categories include practitioners’ abilities to: (a) build rapport with clients, (b) form relationships with athletes based on openness and realistic perceptions; (c) inspire hope and positive expectations; (d) encourage clients to engage in helpful behaviours, and (e) fit within the contexts they are operating. These clusters of characteristics correspond to the mechanisms through which helping relationships lead to client change (Gelso, Citation2019; Rogers, Citation1957; Wampold & Ulvenes, Citation2019).

An ability to build rapport with clients

Across the studies, participants discussed practitioners’ abilities to develop positive interpersonal bonds with athletes (e.g. Dunn & Holt, Citation2003; Mapes, Citation2009; Orlick & Partington, Citation1987). The initial interpersonal bond refers to the degree that athletes and practitioners like, trust, and respect each other (Bordin, Citation1994). Initial conversations between clients and practitioners may involve strangers interacting with each other, with athletes deciding if consultants are trustworthy, have the necessary skills and expertise, care about them, and will make the effort to understand the issues and context (Wampold & Ulvenes, Citation2019). These sentiments were present throughout the reviewed studies, where participants identified a range of specific practitioner characteristics that allow interpersonal bonds to form, including being friendly, approachable, easy to talk to, trustworthy, likeable, concerned for the athlete’s welfare, and being interested in the person (e.g. Cook & Fletcher, Citation2017; Sharp & Hodge, Citation2013; Zakrajsek et al., Citation2013). Participants also discussed that the absence of a warm positive interpersonal bond prevents practitioners from developing a therapeutic relationship with athletes (e.g. Chandler et al., Citation2016; Orlick & Partington, Citation1987; Woolway & Harwood, Citation2019).

This theme reveals a gap in understanding. Although researchers report that an interpersonal bond is helpful, they seldom explore how practitioners build such connections. For example, how practitioners break the ice with strangers, how they encourage athletes to talk, and how they mirror and match client communication. Investigators who delve into the mechanics of interpersonal bonds will yield data to inform practitioner development and training.

An ability to form relationships based on openness and realistic perceptions

Participants in the studies discussed features of the real relationship, described by Gelso (Citation2019) as the extent that practitioners and clients are open, genuine, and have realistic perceptions of each other. Two key features of real relationships are openness and empathetic understanding among the individuals, both of which appeared in the reviewed research (e.g. Chandler et al., Citation2014; Sharp et al., Citation2015; Tod et al., Citation2019). Further, findings from the studies point to the value of practitioners displaying the three therapist conditions Rogers (Citation1957) discussed in person-centred therapy: congruence, unconditional positive regard, and empathy (e.g. Keegan et al., Citation2022; Mapes, Citation2009; Tod et al., Citation2019). Congruence allows practitioners to be open and genuine, and unconditional positive regard and empathy lets them build realistic and empathetic perceptions of athletes.

Participants in the reviewed studies also discussed counselling and communication skills that underpin applied sport psychology, such as active listening, practitioner presence, attending behaviours, and empathic reflections (e.g. Partington & Orlick, Citation1987, Citation1991; Pope-Rhodius, Citation2000). These counselling skills facilitate the practitioner-athlete relationship, which is an unusual social interaction, because of the need for clients to willingly disclose difficult sensitive personal details and the ethical principles practitioners need to uphold, such as confidentiality (Gelso, Citation2019; Wampold, Citation2015). Taken together, the participants’ views in the reviewed studies indicate that the helpful characteristics include a blend of skills (e.g. active listening) and attitudes (e.g. unconditional positive regard), suggesting practitioners are effective because of who they are and what they do.

The ability to inspire positive expectations and hope

Participants in the reviewed studies discussed the need for practitioners to gain athlete ‘buy-in’ or allegiance to applied sport psychology (e.g. Mapes, Citation2009; Partington & Orlick, Citation1991; Weigand et al., Citation1999). The participants’ views echo research from social and counselling psychology in that clients’ expectations influence their future behaviours, experiences, and psychotherapeutic outcomes (Bandura, Citation2018; Constantino et al., Citation2018). Helpful practitioners assist athletes to adopt expectations that fuel change; often a challenge because clients frequently seek help when they have lost hope or are facing difficulties. Paralleling Frank and Frank’s (Citation1993) work on why helping relationships lead to healing, helpful practitioners assist demoralized athletes to move from limiting mindsets to ones in which the focus is on agency and practical solutions (Anderson et al., Citation2004).

Further, the participants in the reviewed studies discussed ways that helpful practitioners influence athlete allegiance. Strategies included being able to communicate clearly and in ways that lay people understand (Statler, Citation2001), having a viable approach to service delivery and problem solving that makes sense to clients (Poczwardowski & Sherman, Citation2011), being a positive role model and making personal use of the techniques shared with athletes (Partington & Orlick, Citation1991). Another strategy was collaboration and working with, rather than on athletes (Chandler et al., Citation2016). Collaborative relationships allowed athletes to generate solutions for themselves or try out ones they had persuaded to themselves would bring benefits (Tod et al., Citation2019). Helping clients identify and try out viable solutions to their issues forms a core feature of the next cluster of attributes.

The ability to help clients engage in helpful actions

Participants frequently mentioned that helpful practitioners assist athletes to find practical strategies, interventions, or ways to address their issues and achieve their goals (e.g. Poczwardowski & Sherman, Citation2011; Thelwell et al., Citation2018; Zakrajsek et al., Citation2013). Practitioners were flexible and adapted their services and interventions to fit athletes’ needs and circumstances (Anderson et al., Citation2004; Keegan et al., Citation2022). Also, practitioners’ knowledge allowed them to adapt interventions and assist athletes in fitting those strategies to their (athlete’s) specific circumstances. Knowledge included understanding psychology, the specific sporting context, and the athlete (Chandler et al., Citation2014; Sharp & Hodge, Citation2011; Zakrajsek et al., Citation2013). When helpful practitioners lacked knowledge, they were willing to learn and treat athletes as experts (Poczwardowski & Sherman, Citation2011).

Also in this cluster of attributes is the practitioner’s ability to secure athletes’ engagement and assist clients in becoming active in the helping process (Low et al., Citation2022; Tod et al., Citation2019). The sentiment among participants parallels counselling research showing that client engagement and active participation is critical for attaining positive outcomes (Bohart & Tallman, Citation2010; Holdsworth et al., Citation2014). Through encouraging active participation, practitioners help athletes engage in adaptive and healthy activities that lead to change. From the reviewed studies, these adaptive activities might include behaviours, such as developing their mental skills (Low et al., Citation2022), or adopting new ways of thinking (Weigand et al., Citation1999).

This observation that helpful practitioners inspire athletes to take an active role in the collaborative relationship reveals that consultant characteristics and interventions interact to influence client change. To illustrate, goal setting (intervention) leads to change in behaviour and skill execution (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995). Many athletes are aware of goal setting but need help in attaining its benefits and only start using it with the assistance of a practitioner (Weinberg & Williams, Citation2021). Assisting athletes to make use of goal setting will enhance their hope, beliefs in, and allegiance to practitioners’ approach to helping. Positive outcomes will also enhance the interpersonal bond and therapeutic relationship by enhancing athletes’ trust, respect, and liking for their practitioners.

The ability to operate in the sporting domain

Participants throughout the reviewed studies discussed how helpful practitioners have the interpersonal skills and contextual knowledge to fit within the team, organization, or context in which they were operating (e.g. Arnold & Sarkar, Citation2015; McDougall et al., Citation2015; Tod et al., Citation2019). Example issues that participants discussed included (a) dealing with stigmas around applied psychology and mental health, (b) resolving ethical challenges, such as confidentiality and knowing who the client is, and (c) coping with gender stereotypes and sexual attraction (e.g. Mapes, Citation2009; Sharp & Hodge, Citation2011; Zakrajsek et al., Citation2013). Additional contextual factors participants mentioned that influence the help practitioners could offer included the amount of time they got to spend with athletes and the support they received from coaches (Orlick & Partington, Citation1987). According to participants, practitioners with refined interpersonal skills and knowledge about the sport, the organization, the culture, and the people involved, could embed themselves into the environment, build relationships with the various stakeholders, and act in helpful ways during difficult moments, such as knowing what type of support to offer during competition (e.g. Arnold & Sarkar, Citation2015; Castillo et al., Citation2022; McDougall et al., Citation2015).

Discussion

The results above revealed a coherent framework summarizing the major findings from qualitative research on stakeholders’ perceptions of the characteristics of helpful practitioners. The results included five clusters of characteristics, including the ability to (a) form positive interpersonal bonds with clients, (b) develop real relationships with athletes based on openness and realistic perceptions, (c) encourage hope and positive expectations, (d) inspire athletes to engage in the change process, and (e) operate within the sporting context. These results contribute to existing literature as discussed below.

The current review provides a novel synthesis of the qualitative research. First, previous reviews have focused on different, albeit related, topics, such as the attributes that influence the decision to seek services (Woolway & Harwood, Citation2020) or are dated and have not included contemporary research (Tod & Andersen, Citation2005). Half the studies in the current review have appeared since 2015. Second, previous reviews have been atheoretical, whereas in the current project we explored a range of theories related to the helping professions to allow us to synthesize the research into a coherent framework that could stimulate applied implications and future research avenues. To help move past the atheoretical feature, we drew on counselling psychology theories to help cluster and synthesize findings from the research (e.g. Bordin, Citation1994; Gelso, Citation2019; Rogers, Citation1957; Wampold & Ulvenes, Citation2019). Third, previous reviews have not included a formal critical appraisal of the studies to assess the level of confidence readers can have that the primary research findings provide a rigorous representation of the phenomenon of interest. As such, by reviewing both classic and contemporary investigations (from inside and outside the typical scientific publishing channels [i.e. grey literature]) through a theoretical lens, and subjecting them to a formal critical appraisal of the underlying studies, the current review complements and extends the primary research and existing reviews, thereby moving the field forward, both theoretically and practically, to further elucidate knowledge.

The parallels between the findings in this review and the broader literature and theory on helpful practitioners in the helping professions lends credibility to the results. As a first example, this review found that the included studies consistently revealed that helpful practitioners have characteristics that allow them to build positive rapport and real relationships with athletes, similar to findings that have emerged in counselling and psychotherapy research (Gelso, Citation2019; Wampold & Owen, Citation2021). Specifically, effective counsellors and therapists have refined socio-emotional characteristics, including empathy, warmth, positive regard, communication skills, and the capacity to manage criticism that together allow them to form and repair relationships with clients (Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2020). As a second example, the current review found that across the research helpful practitioners collaborate with athletes and individualize the help they offer to ensure that clients have hope, positive expectations, and can apply interventions to suit their specific needs and circumstances, another similarity with the broader literature on counselling and psychotherapy (Miller & Moyers, Citation2021). As a third example, a trend across the reviewed studies is that self-reflection, a realistic understanding of applied sport psychology (described as modesty or humility), and a willingness to learn about athletes, their circumstances, and their sporting contexts and cultures are characteristics that allow practitioners to fit into sporting organizations and assist athletes. These findings also appear in counselling and psychotherapy research (Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2020; Wampold & Owen, Citation2021). The review findings point to cultural humility being a characteristic of helpful practitioners. Practitioners who are culturally humble: (a) approach clients with respect and openness, (b) work collaboratively with clients, (c) seek to understand the intersection of clients’ various identities, and (d) how that affects the working alliance (Hook et al., Citation2013). Cultural humility incorporates self-evaluation, a willingness to share power with clients, and a desire to develop mutually beneficial partnerships with individuals and their communities (Tervalon & Murray-García, Citation1998). Cultural humility embraces more than learning about and appreciating a client’s national or ethnic background. Different sports, organizations, and competitive levels within a sport will have (sub)cultures that practitioners will benefit from understanding (Hanrahan & Lee, Citation2020). Such an observation emerged in the current research when participants indicated practitioners needed to understand and fit within the sports, teams, and organizations with whom they were working, and dovetails with the work of cultural sport psychology (Hanrahan & Lee, Citation2020).

The findings of the current review also fit well with related bodies of research in applied sport psychology. For example, similar related findings have emerged from longitudinal studies examining professional development in trainees (Fogaca et al., Citation2018; Haluch et al., Citation2022; McEwan et al., Citation2019; Tod et al., Citation2011). The two bodies of research (trainee professional development and characteristics of helpful practitioners) complement each other. The studies on characteristics describe the types of outcomes that professional development in general, and postgraduate education in the discipline specifically, aim to achieve. For example, some of the chief aims in professional development, training, and supervision is to help practitioners learn how to (a) build real relationships with clients, (b) inspire realistic expectations in athletes, (c) help clients engage in the helping alliance and use interventions that lead to change, and (d) fit within the contexts and organizations they work. The longitudinal studies of trainee maturation describe how neophyte practitioners achieve these chiefs aims, along with insights about the sources of influence and their experiences of becoming sport psychology practitioners. Together, the two bodies of knowledge outline a blueprint or treasure map that can assist practitioners and professional bodies when designing training and continued professional development. The research on stakeholders’ perceptions of helpful practitioners is the X that marks the spot, and the longitudinal studies outline the territory and journey.

As a second example illustrating how the current review complements other research in applied sport psychology, a number of the findings parallel those from reflective practice articles (e.g. Porter et al., Citation2021). A recent review found topics such as building relationships, cultural awareness, self-awareness, and considering ethical challenges emerged commonly across the reflective practice articles (Wadsworth et al., Citation2021), and these subjects also appeared in the studies on stakeholders’ perceptions of helpful practitioners. The appearance of comparable topics across two approaches to research enhances confidence that these findings are robust and provide an informed representation of the area. Such an interpretation, however, is tempered by the observation that some of the practitioners who have written the reflective practice articles have also occasionally been the individuals interviewed in the research reviewed here. Nevertheless, the research reviewed here drew on a range of stakeholders, including athletes, coaches, parents, support staff, and administrators, and not only sport psychology practitioners. The consistency across the various stakeholders indicates that the findings on which this review is based are not unduly influenced by the practitioners who have also written reflective practice articles. The current review contributes because it allows the participants’ voices to be heard and avoids the bias of practitioners talking about themselves.

Investigators have used few data collection techniques, analysis methods, and research designs. Most studies use one-shot interviews, some version of thematic analysis, and cross-sectional designs. Further, researchers typically write a post-positivistic realist tale, characterized by researcher experiential authority, the foregrounding of participants’ views, and interpretative omnipotence (Van Maanen, Citation2011), and they write in the classic style (Thomas & Turner, Citation2011), using a disembodied voice to present an alleged untainted version of participants’ beliefs. Although these studies contribute to knowledge, their uniformity of design and presentation stifles theory development.

First, the uniformity of research methods has weaknesses that limit understanding. For example, one-shot interviews may yield superficial data if the interviewer lacks suitable skills, the researcher-participant relationship has not had time to establish itself, or interviewees have not reflected sufficiently on the topics under scrutiny. As another example, although thematic analysis generates a structured presentation of participants’ data, it tends to be descriptive rather than interpretative (Patton, Citation2015). Researchers who employ diverse methods will allow alternative ways to evaluate current knowledge to emerge.

Second, presenting results in the realist tale tradition and relying on classic style ignores the logistical, cultural, and political complexities involved in research. These styles prevent investigator reflexivity from providing insights into how the findings were generated. The lack of reflection about the researcher-participant relationship is one example. As another example, classic style hides the fact that the supposedly untainted participants’ voices presented as the studies’ results, have actually been washed, rinsed, and spun through the researchers’ theoretical frameworks. Realist tales also deliver results at a cognitive level and underplay the behavioural and emotional dimensions of knowledge. For example, stating that helpful practitioners adhere to the ethical principle of beneficence to clients tells readers little about the guilt, shame, self-criticism, and political ramifications practitioners experience when they are in situations where there are no clear guidelines on how to act and there are justifications for actions that might threaten clients’ social or legal welfare. Just as researchers will help advance knowledge by employing a diverse range of methods, they will also progress understanding by moving away from a reliance on classic or realist styles of representation. Alternatives include confessional, reflexive, and fictional styles of writing (Sparkes, Citation2002).

In addition to extending existing knowledge, the current review identifies avenues of for future research. Above, for example, we suggested that experiments could examine the effect that the proposed characteristics have on the processes and outcomes of practitioner-athlete relationships. Experiments could also examine the optimal ways to teach and help trainees develop the characteristics associated with helpful practitioners (or even if they can be taught). Quantitative descriptive research could examine what proportion of practitioners display these characteristics and how they might change over time. Descriptive work could also measure the relationships between characteristics and other variables linked to service delivery, such as the number of sessions athletes have with practitioners, their completion of out-of-session exercises, and their willingness to pay for services.

Investigators could also continue using qualitative research methods to expand the area. For example, they could follow dyads longitudinally and explore athletes’ and practitioners’ accounts of how the characteristics are displayed, are received, and change. The existing qualitative studies focus on participants from western affluent individualistic societies, indicating that current knowledge privileges certain groups and regions in the world. Studies across a range of cultures and societies will lead to richer understanding of the area. Also, researchers could explore how the characteristics are displayed, are received, and change within dyads consisting of people from diverse cultural groups (e.g. a WERID practitioner working with an athlete from a BAME background). Likewise, organizations, sports, and even diverse levels of competition have their own cultures and subcultures. Researchers could both broaden knowledge (by examining different regions and groups) and deepen knowledge by examining different sports, organizations, and competitive levels within a region. Such research could shed light on how best to collaborate with clients in specific circumstances. For example, Si et al. (Citation2015) explored how practitioners recognized and adapted services to fit within the Chinese sport system.

Furthermore, males form the majority of people sampled and researchers have not reported participants’ sexual orientation. Readers cannot determine the studies’ participant diversity or if individuals from LGBTQ + communities have been ignored. It is unknown how such an imbalance has biased current knowledge. Berke et al. (Citation2016) showed that people from LGBTQ + communities have unique needs during psychotherapy, including practitioner acceptance and recognition of their multifaceted identities. Researchers who conduct similar studies in sport psychology will provide practitioners with guidelines to help them form strong collaborative relationships with the diverse range of clients they help.

Previously we acknowledged that the synthesis reflected our interpretation of the research, a feature in any review of qualitative research. As another consideration, this review was based on studies written in the English language. This decision reflected our background and available resources (e.g. to access faithful translation services). The restriction to studies written in the English language, however, does not automatically result in biased findings (Dobrescu et al., Citation2021; Morrison et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, the inclusion of studies written in English may exacerbate the observation that the research is based on samples from Western, affluent, and individualistic societies. Greater research on a diverse range of samples will yield a broader and deeper knowledge base.

The review findings support applied implications. First, information about stakeholders’ perceptions of helpful practitioners can help trainees and other consultants reflect on their personal strengths and weaknesses, and they can identify areas for improvement and direction for continued professional development. Second, educators and supervisors might use the review findings to enhance the teaching and guidance they offer students and supervisees. Third, the results can guide professional organizations’ attempts to design and evaluate practitioner education pathways and vocational qualifications. Implications along each of these avenues may help practitioners provide optimal services to clients.

Conclusion

Investigations in applied sport psychology indicate that practitioners vary in the level of assistance they provide clients (e.g. Orlick & Partington, Citation1987). Since the late 1980s, investigators have sought to understand stakeholders’ perceptions about helpful practitioners. According to this review, helpful practitioners have the skills, knowledge, and characteristics to (a) build rapport or interpersonal bonds with athletes, (b) develop real relationships based on openness and realistic perceptions, (c) inspire hope and suitable expectations, (d) promote engagement in the change process, and (e) operate in the contexts where clients are located. The findings point to future research that can expand current knowledge, such as sampling a greater diversity of participants and employing different research designs. As research on practitioner characteristics grows, the findings will help consultants, educators, supervisors, and professional organizations develop their own, and other people’s skills, abilities, and knowledge, leading to athletes, coaches, performers, and other clients accessing enhanced services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersen, M. B., & Ivarsson, A. (2016). A methodology of loving kindness: How interpersonal neurobiology, compassion and transference can inform researcher–participant encounters and storytelling. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 8(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1056827

- Anderson, A., Miles, A., Robinson, P., & Mahoney, C. (2004). Evaluating the athlete’s perception of the sport psychologist’s effectiveness: What should we be assessing? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(3), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(03)00005-0

- Arnold, R., & Sarkar, M. (2015). Preparing athletes and teams for the Olympic Games: Experiences and lessons learned from the world’s best sport psychologists. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.932827

- Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617699280

- Barker, S., & Winter, S. (2014). The practice of sport psychology: A youth coaches' perspective. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 9(2), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.9.2.379.

- Berke, D. S., Maples-Keller, J. L., & Richards, P. (2016). LGBTQ perceptions of psychotherapy: A consensual qualitative analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 47(6), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000099

- Bohart, A. C., & Tallman, K. (2010). Clients: The neglected common factor in psychotherapy. In B. L. Duncan, S. D. Miller, B. E. Wampold, & M. A. Hubble (Eds.), The heart and soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy (2nd ed., pp. 83–111). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12075-003

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. Sage.

- Bordin, E. S. (1994). Theory and research on the therapeutic working alliance: New directions. In A. O. Horvath & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), The working alliance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 13–37). Wiley.

- Castillo, E. A., Block, C. J., Bird, M. D., & Chow, G. M. (2022). A qualitative analysis of novice and expert mental performance consultants’ professional philosophies. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2035849

- Castillo, E. A., Block, C. J., Bird, M. D., & Chow, G. M. (2022). A qualitative analysis of novice and expert mental performance consultants’ professional philosophies. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2035849.

- Castonguay, L. G., & Hill, C. E. (2017). How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects. American Psychological Association.

- Chandler, C. (2015). Exploring the contribution of personal qualities to the effective delivery of sport psychology service provision. Doctoral thesis, Liverpool John Moores University.

- Chandler, C., Eubank, M., Nesti, M., & Cable, T. (2014). Personal qualities of effective sport psychologists: A sports physician perspective. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 61(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2014-0003

- Chandler, C., Eubank, M., Nesti, M., Tod, D., & Cable, T. (2016). Personal qualities of effective sport psychologists: Coping with organisational demands in high performance sport. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 47(4), 297–317. https://doi.org/10.7352/IJSP2016.47.297

- Collins, C. S., & Stockton, C. M. (2018). The central role of theory in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918797475

- Constantino, M. J., Vîslă, A., Coyne, A. E., & Boswell, J. F. (2018). A meta-analysis of the association between patients’ early treatment outcome expectation and their posttreatment outcomes. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000169

- Cook, G. M., & Fletcher, D. (2017). Sport psychology in an Olympic swimming team: Perceptions of the management and coaches. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(5), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000142

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). Critical qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416681864

- Dobrescu, A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Klerings, I., Wagner, G., Persad, E., Sommer, I., Herkner, H., & Gartlehner, G. (2021). Restricting evidence syntheses of interventions to English-language publications is a viable methodological shortcut for most medical topics: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 137, 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.04.012

- Dunn, J. G. H., & Holt, N. L. (2003). Collegiate ice hockey players’ perceptions of the delivery of an applied sport psychology program. The Sport Psychologist, 17(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.17.3.351

- Erwin, E. J., Brotherson, M. J., & Summers, J. A. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(3), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111425493

- Estabrooks, C. A., Field, P. A., & Morse, J. M. (1994). Aggregating qualitative findings: An approach to theory development. Qualitative Health Research, 4(4), 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239400400410

- Fogaca, J. L., Zizzi, S. J., & Andersen, M. B. (2018). Walking multiple paths of supervision in American sport psychology: A qualitative tale of novice supervisees’ development. The Sport Psychologist, 32(2), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2017-0048

- Fortin-Guichard, D., Boudreault, V., Gagnon, S., & Trottier, C. (2018). Experience, effectiveness, and perceptions toward sport psychology consultants: A critical review of peer-reviewed articles. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1318416

- Frank, J. D., & Frank, J. B. (1993). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy. JHU Press.

- Gelso, C. J. (2019). The therapeutic relationship in psychotherapy practice: An integrative perspective. Routledge.

- Gould, D., Murphy, S., Tammen, V., & May, J. (1991). An evaluation of U.S. Olympic sport psychology consultant effectiveness. The Sport Psychologist, 5, 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.5.2.111.

- Haluch, P., Radcliffe, J., & Rowley, C. (2022). The quest for professional self-understanding: Sense making and the interpersonal nature of applied sport psychology practice. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(6), 1312–1333. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1914772

- Hanrahan, S., & Lee, S.-M. (2020). Cultural considerations in practice. In D. Tod & M. Eubank (Eds.), Applied sport, exercise, and performance psychology: Current approaches to helping athletes (pp. 181–196). Routledge.

- Heinonen, E., & Nissen-Lie, H. A. (2020). The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: A systematic review. Psychotherapy Research, 30(4), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366

- Holdsworth, E., Bowen, E., Brown, S., & Howat, D. (2014). Client engagement in psychotherapeutic treatment and associations with client characteristics, therapist characteristics, and treatment factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(5), 428–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.004

- Holt, N. L., Neely, K. C., Slater, L. G., Camiré, M., Côté, J., Fraser-Thomas, J., MacDonald, D., Strachan, L., & Tamminen, K. A. (2017). A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704

- Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Utsey, S. O. (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032595

- Keegan, R., Stoljarova, S., Kessler, L., & Jack, S. (2022). Psychological support for the talent pathway: Qualitative process evaluation of a state sport academy’s psychology service. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(3), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1833378

- Keegan, R., Stoljarova, S., Kessler, L., & Jack, S. (2022). Psychological support for the talent pathway: Qualitative process evaluation of a state sport academy’s psychology service. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(3), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1833378.

- Kyllo, L. B., & Landers, D. M. (1995). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 17(2), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.2.117

- Low, W., Butt, J., Freeman, P., Stoker, M., & Maynard, I. (2022). Effective delivery of pressure training: Perspectives of athletes and sport psychologists. The Sport Psychologist, 36(3), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2021-0178

- Mapes, R. (2009). Athletes’ experiences of sport psychology consultation: Exploring a multi-season, cross gender intervention. University of Missouri–Columbia. https://doi.org/10.32469/10355/10766

- McDougall, M., Nesti, M., & Richardson, D. (2015). The challenges of sport psychology delivery in elite and professional sport: Reflections from experienced sport psychologists. The Sport Psychologist, 29(3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2014-0081

- McEwan, H. E., Tod, D., & Eubank, M. (2019). The rocky road to individuation: Sport psychologists’ perspectives on professional development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, Article e101542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101542

- Middleton, T. R., Petersen, B., Schinke, R. J., & Giffin, C. (2020). Community sport and physical activity programs as sites of integration: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research conducted with forced migrants. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 51, Article e101769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101769

- Miller, W. R., & Moyers, T. B. (2021). Effective psychotherapists. Guilford Publications.

- Morrison, A., Polisena, J., Husereau, D., Moulton, K., Clark, M., Fiander, M., Mierzwinski-Urban, M., Clifford, T., Hutton, B., & Rabb, D. (2012). The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: A systematic review of empirical studies. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 28(2), 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462312000086

- Munthe-Kaas, H. M., Glenton, C., Booth, A., Noyes, J., & Lewin, S. (2019). Systematic mapping of existing tools to appraise methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative research: First stage in the development of the CAMELOT tool. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), Article e113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0728-6

- Noyes, J., Booth, A., Cargo, M., Flemming, K., Harden, A., Harris, J., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Pantoja, T., & Thomas, J. (2022). Qualitative evidence. In J. P. T. Higgins, T. J. J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 6.3). Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Orlick, T., & Partington, J. (1987). The sport psychology consultant: Analysis of critical components as viewed by Canadian Olympic athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 1(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.1.1.4

- Partington, J., & Orlick, T. (1987). The sport psychology consultant: Olympic coaches’ views. The Sport Psychologist, 1(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.1.2.95

- Partington, J., & Orlick, T. (1991). An analysis of Olympic sport psychology consultants’ best-ever consulting experiences. The Sport Psychologist, 5(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.5.2.183

- Paterson, B. L., Thorne, S. E., Canam, C., & Jillings, C. (2001). Meta-study of qualitative health research: A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Sage.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage.

- Poczwardowski, A. (2019). Deconstructing sport and performance psychology consultant: Expert, person, performer, and self-regulator. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(5), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1390484

- Poczwardowski, A., & Sherman, C. P. (2011). Revisions to the sport psychology service delivery (SPSD) heuristic: Explorations with experienced consultants. The Sport Psychologist, 25(4), 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.25.4.511

- Poczwardowski, A., & Sherman, C. P. (2011). Revisions to the sport psychology service delivery (SPSD) heuristic: Explorations with experienced consultants. The Sport Psychologist, 25(4), 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.25.4.511.

- Poczwardowski, A., Sherman, C. P., & Ravizza, K. (2004). Professional philosophy in the sport psychology service delivery: Building on theory and practice. The Sport Psychologist, 18(4), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.18.4.445

- Pope-Rhodius, A. J. (2000). Exploring the role of the sport psychologist: Athletes’ and practitioners’ reflections on applied experiences and competencies. Liverpool John Moores University.

- Porter, S., Ronkainen, N., Sille, R., & Eubank, M. (2021). An existential counseling case study: Navigating several critical moments with a professional football player. Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(1), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1123/cssep.2021-0013

- Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C. A., & Evers, K. E. (2015). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (5th ed., pp. 125–148). Jossey-Bass.

- Quartiroli, A., Etzel, E. F., Knight, S. M., & Zakrajsek, R. A. (2019). Self-care as key to others’ care: The perspectives of globally situated experienced senior-level sport psychology practitioners. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1460420

- Quartiroli, A., Knight, S. M., Etzel, E. F., & Zakrajsek, R. A. (2019). Fostering and sustaining sport psychology professional quality of life: The perspectives of senior-level, experienced sport psychology practitioners. The Sport Psychologist, 33(2), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2017-0140

- Quartiroli, A., Wagstaff, C. R., Martin, D. R., & Tod, D. (2021). A systematic review of professional identity in sport psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–27. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1998577

- Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045357

- Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships: As developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science. Formulations of the person and the social context (Vol. 3, pp. 184–256). McGraw-Hill.

- Sandu, A., & Unguru, E. (2017). Several conceptual clarifications on the distinction between constructivism and social constructivism. Postmodern Openings/Deschideri Postmoderne, 8(2), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.18662/po/2017.0802.04

- Sharp, L.-A., & Hodge, K. (2011). Sport psychology consulting effectiveness: The sport psychology consultant’s perspective. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(3), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.583619

- Sharp, L.-A., & Hodge, K. (2013). Effective sport psychology consulting relationships: Two coach case studies. The Sport Psychologist, 27(4), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.27.4.313

- Sharp, L. A., & Hodge, K. (2014). Sport psychology consulting effectiveness: The athlete's perspective. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.804285.

- Sharp, L.-A., Hodge, K., & Danish, S. (2014). Sport psychology consulting at elite sport competitions. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 3(2), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000011.

- Sharp, L.-A., Hodge, K., & Danish, S. (2015). Ultimately it comes down to the relationship: Experienced consultants’ views of effective sport psychology consulting. The Sport Psychologist, 29(4), 358–370. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2014-0130

- Si, G., Duan, Y., Li, H. Y., Zhang, C. Q., & Su, N. (2015). The influence of the Chinese sport system and Chinese cultural characteristics on Olympic sport psychology services. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 17, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.008

- Simons, J. P., & Andersen, M. B. (1995). The development of consulting practice in applied sport psychology: Some personal perspectives. The Sport Psychologist, 9(4), 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.9.4.449

- Simonsmeier, B. A., Andronie, M., Buecker, S., & Frank, C. (2021). The effects of imagery interventions in sports: A meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(1), 186–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2020.1780627

- Smith, B. (2018). Generalizability in qualitative research: Misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(1), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221

- Sparkes, A. (2002). Telling tales in sport and physical activity: A qualitative journey. Human Kinetics Publishers.

- Statler, T. A. (2001). The art of applied sport psychology: Perceptions of outstanding consultants. The University of Utah.

- Stevens, L. M., & Andersen, M. B. (2007). Transference and countertransference in sport psychology service delivery: Part II. Two case studies on the erotic. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 19(3), 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200701314011

- Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

- Thelwell, R. C., Wood, J., Harwood, C., Woolway, T., & Van Raalte, J. L. (2018). The role, benefits and selection of sport psychology consultants: Perceptions of youth-sport coaches and parents. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 35, 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.12.001

- Thomas, N.-F., & Turner, M. (2011). Clear and simple as the truth: Writing classic prose (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914

- Tod, D. (2017). Performance consultants in sport and performance Psychology. In O. Braddick (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia, psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.142

- Tod, D., & Andersen, M. B. (2005). Success in sport psych: Effective sport psychologists. In S. Murphy (Ed.), The sport psych handbook (pp. 305–314). Human Kinetics.

- Tod, D., Andersen, M. B., & Marchant, D. B. (2011). Six years up: Applied sport psychologists surviving (and thriving) after graduation. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2010.534543

- Tod, D., Hardy, J., Lavallee, D., Eubank, M., & Ronkainen, N. (2019). Practitioners’ narratives regarding active ingredients in service delivery: Collaboration-based problem solving. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.04.009

- Van Maanen, J. (2011). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography. University of Chicago Press.

- Verner, D., Chandler, C., & Clarke, P. (2021). Exploring the contribution of personal qualities to the personal and professional development of trainee sport psychology practitioners’ within the individuation process. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 92(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2021-0024.