ABSTRACT

Athlete burnout is a psychological syndrome with substantial negative consequences, including depression and sport dropout. It has been linked to a range of factors, some of which may vary across different sport-types. This review is the first to synthesise variables examined in relation to burnout in team-sports specifically. An online search of seven relevant databases yielded 59 papers examining 123 burnout correlates. Eligible papers were peer-reviewed, quantitative empirical studies, which assessed burnout using the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire. Results are reported in-line with PRISMA guidelines. Weighted meta-analysis (WMA) assessed the strength of the relationship between burnout dimensions and 18 variables examined across ≥3 samples. A narrative synthesis of the remaining cross-sectional, longitudinal and mediating/moderating relationships provides a comprehensive overview of the literature. Burnout displayed a negative relationship with autonomy, competence, relatedness, self-determined motivation, positive affect, autonomy supportive coach, harmonious passion, self-oriented perfectionism and social support, and a positive relationship with amotivation, negative affect, obsessive passion, socially-prescribed perfectionism, ego-involving climate, playing experience and controlling coach style in the WMA. Some variability in relationships was identified across the dimensions of burnout. The results highlight the key factors associated with the dimension of burnout in team sports, which may inform targeted intervention strategies.

Introduction

Athlete burnout is commonly defined as a multidimensional psychological syndrome, characterised by enduring feelings of physical and emotional exhaustion (PEE), reduced sense of accomplishment (RSA), and sport devaluation (SD; Raedeke, Citation1997). Feelings of PEE relate to the intense training and competition associated with sport, while RSA refers to an athlete’s perceived inability to achieve their sporting goals or perform to their potential, and SD is a loss of interest in, or resentment towards, one’s sport. Athletes who are burned out develop and experience a combination of these three symptoms over a period of time (Raedeke, Citation1997), and are also at increased risk of experiencing additional negative consequences associated with burnout, both within and outside of the sporting environment. Such consequences include reduced performance levels, sport dropout, physical illness, and depression (De Francisco et al., Citation2016; Raedeke et al., Citation2002). As such, for athletes who are experiencing burnout, as with other mental health challenges in sport (Newman et al., Citation2016), their sport participation can have a negative impact on their lives.

Although there is general consensus around the multi-dimensional definition of athlete burnout, debate remains as to the key factors associated with its onset (Gustafsson et al., Citation2011). This is evident in the existing competing models of athlete burnout, which identify factors ranging from appraisal of stressors (cognitive-affect stress model; Smith, Citation1986), a sport-centred identity (social organisation of sport model; Coakley, Citation1992), aspects of commitment (commitment-centred model; Raedeke, Citation1997) and an absence of internal motivation (self-determination theory; SDT; Horn & Smith, Citation2018) as key predictors of burnout symptoms. While these models have all received some level of support (e.g. Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Goodger et al., Citation2007; Woods et al., Citation2020), Madigan et al. (Citation2021) highlight the fact that critical analysis of their predictive utility is lacking, while the absence of a singular model of burnout also means researchers are without an essential guide in research direction and design (Osanloo & Grant, Citation2016). Consequently, researchers have continued to examine a variety of correlates of burnout, as well as potential mediators and moderators of these relationships (e.g. Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Chyi et al., Citation2018; Cremades & Wiggins, Citation2008; Cremades et al., Citation2011; Goodger et al., Citation2007). In addition, existing literature suggests that the impact of some variables may differ across the dimensions of burnout, for example Isoard-Gautheur et al. (Citation2013) found that although perceived competence negatively predicted feelings of PEE and RSA, it did not predict the SD dimension of burnout. Identifying the key factors associated with the dimensions of athlete burnout may help to inform the development of a more comprehensive theoretical model.

To our knowledge, five systematic reviewsFootnote1 of factors associated with athlete burnout have been undertaken to-date, four of which have incorporated a meta-analysis.Footnote2 In the first of these reviews, Goodger et al. (Citation2007) examined and grouped sets of correlates of burnout in athletes, coaches and officials; for athletes, psychological correlates identified included variables such as motivation, coping and identity, while situational correlates included training load or volume. Two subsequent meta-analyses focused specifically on psychological correlates of athlete burnout, with both Li et al. (Citation2013) and Bicalho and Costa (Citation2018) examining types of motivation and basic psychological needs, and the latter also including passion and perfectionism (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018). Pacewicz and colleagues’ (Citation2019) meta-analysis centred on social constructs associated with burnout, including social support, relatedness and negative social interactions. Finally, the most recent review and meta-analysis by Lin et al. (Citation2021) specifically examined the relationship between burnout and stress. The correlates of burnout identified across these reviews include training load, coping with adversity, responses to training and recovery, the role of significant others, identity (Goodger et al., Citation2007), the satisfaction/thwarting of psychological needs (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2013), motivation (Goodger et al., Citation2007; Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018), social support, relatedness, negative social interactions (Pacewicz et al., Citation2019) and athlete stress (Lin et al., Citation2021).

However, the relatively narrow focus of the four most recent reviews of the literature (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2013; Lin et al., Citation2021; Pacewicz et al., Citation2019) on specific psychological (e.g. stress, motivation) and social constructs, may inadvertently have led to the exclusion of, for example, research examining situational or demographic variables, or variables associated with other theoretical perspectives such as commitment. As such, comprehensive review of the literature on correlates of athlete burnout has not been conducted since Goodger et al. (Citation2007) review over a decade ago. In addition, Goodger et al.’s (Citation2007) assessment of burnout as a unidimensional construct provides no insight into the impact of variables across the burnout dimensions. Focusing on studies that utilised the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ; Raedeke & Smith, Citation2001), in line with Pacewicz and colleagues’ (Citation2019) review, can ensure that burnout is conceptualised in-line with its well-accepted, multi-dimensional definition (Madigan, Citation2021).

Finally, an additional limitation of existing reviews is that the potentially nuanced burnout experiences of different types of athletes may be lost as a result of the relatively broad population assessed; with the exception of Bicalho and Costa’s (Citation2018) review, which focused on elite athletes, the existing systematic reviews (e.g. Goodger et al., Citation2007; Li et al., Citation2013) did not distinguish between different samples of athletes in their inclusion criteria, instead including athletes across all sports and levels. Lin et al. (Citation2021) did however explore athlete age and role (i.e. high-school student-athletes, college student-athletes and club players) as moderators of the stress-burnout relationship; they found a stronger stress-burnout correlation in club players and in those aged 19–22 respectively. While athletes can be divided into subgroups using different criteria, another potentially useful division in the context of athlete burnout is sport type (Lin et al., Citation2021), whereby sports are classified as individual or team sports. Team sports can be operationalised as those in which one can compete as a team of two or more players, and individual competition is not possible (e.g. football, basketball or hockey; e.g. Gustafsson et al., Citation2016; Reche et al., Citation2018). Conceptually, it can be argued that both the sporting environments and the athletes have unique characteristics that may impact the experience of burnout; team environments are characterised by substantial levels of social-interaction and cooperation among a group, with cohesion and team-work necessary for success, and shared experiences of failure (McEwan & Beauchamp, Citation2020). In contrast, individual-sport athletes may feel sole responsibility for successes and failures, but also often have a closer coach-athlete relationship (Rhind et al., Citation2012).

In the context of burnout, existing research highlights potential differences in the experiences of team and individual-sport athletes. Specifically, researchers have identified higher levels of RSA (Reche et al., Citation2018) and PEE (Davis et al., Citation2019; Gustafsson et al., Citation2007) in male and female team-sport athletes when compared to their individual-sport counterparts. In addition, team-sport athletes have been shown to experience a more ego-orientated motivational climate (Van de Pol & Kavussanu, Citation2012), higher levels of maladaptive perfectionism (Nixdorf et al., Citation2016) and lower levels of autonomy (Nia & Besharat, Citation2010), positivity, resilience, self-esteem and self-efficacy (Laborde et al., Citation2016) compared to their individual sport counterparts, all of which have been associated with increased levels of burnout (Gustafsson et al., Citation2018; Koçak, Citation2019; Martínez-Alvarado et al., Citation2021; Vitali et al., Citation2015). These findings suggest that team-sport athletes are at a greater risk of experiencing burnout. However, in contrast, Cremades and Wiggins (Citation2008) identified lower levels of RSA in team-sport athletes compared to those competing individually, and Baella-Vigil et al. (Citation2020) report a protective factor of team-sport participation against TB. Team-sport athletes have also been shown to report less depressive symptoms (Nixdorf et al., Citation2016; Sabiston et al., Citation2016) and higher levels of enjoyment (Van de Pol & Kavussanu, Citation2012), characteristics that are associated with lower levels of burnout (De Francisco et al., Citation2016; Woods et al., Citation2020). In addition, a systematic review of the benefits of sport participation indicates that athletes involved in team sports experience more positive social and psychological outcomes than those involved in individual sports (Eime et al., Citation2013). Finally, the specific stressors reported by team and individual-sport athletes have been shown to differ (Nicholls et al., Citation2007).

Taken together, the differences identified across sport-types in both levels of burnout (e.g. RSA and PEE) reported and factors associated both positively (e.g. maladaptive perfectionism) and negatively (e.g. enjoyment) with burnout in the existing literature suggest that the experience of burnout differs for team- versus individual-sport athletes. As such, we argue that focusing on team-sport athletes specifically, while simultaneously employing the multi-dimensional conceptualisation of burnout and broadening the variety of variables examined in this review, will provide useful and nuanced insight into the key factors associated with burnout in team sports. Such is the breadth and variety of the research on athlete burnout, there is a need to collate and synthesise the findings to-date. Such insight also has the potential to inform the development of strategies and interventions to alleviate or guard against burnout among this group (MacIntyre et al., Citation2017), which should be of interest to all key-stakeholders in team sports, including organising bodies, coaches and athletes themselves. In a recent search of the literature, Madigan (Citation2021) identified just three existing intervention studies, two of which (Dubuc-Charbonneau & Durand-Bush, Citation2015; Gabana et al., Citation2019) were limited by their observational nature, thus highlighting the need for further work in this area.

As such, the aims of this systematic review were two-fold; firstly, in-line with the key purpose of a systematic review (Chandler et al., Citation2019), we aimed to collate and synthesise the quantitative research that examines the association between any variable and athlete burnout (or one or more of its subcomponents) in team-sport athletes. Secondly, where possible, we aimed to employ meta-analytic technique to analyse the strength of the evidence for the associations examined most frequently through meta-analytic techniques.

Method

Search strategy

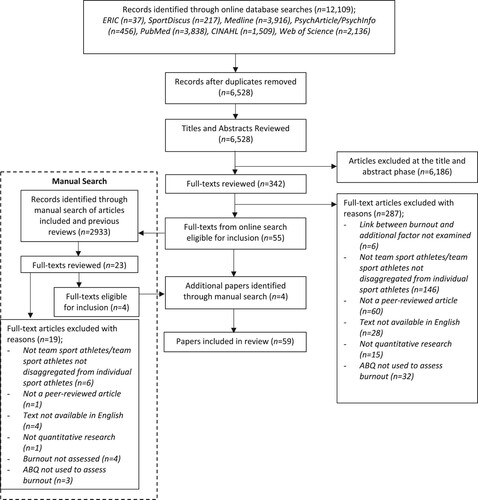

We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., Citation2009) guidelines in conducting this review and preparing the manuscript. The PRISMA checklist is available as a supplementary file (see Supplementary File 1). In line with previous systematic reviews conducted in the area (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Gustafsson et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2013), we systematically searched the following electronic databases: SportDiscus, PsychInfo/PsychArticles, ERIC, PubMed, Medline, Web of Science and CINAHL. Specific search strategies are outlined in . We supplemented this search strategy with manual searches of the reference lists of the full-text papers identified for inclusion in the review, and of the four systematic reviews that have previously been conducted in the area of athlete burnout. The last search of databases took place on 17/11/2021.

Table 1. Search strategy used for each database.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in this review, a study must have (1) quantitatively analysed the relationship between athlete burnout and another factor, (2) been available in English and (3) used the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ; Raedeke & Smith, Citation2001). The decision to exclude papers that did not use the ABQ (Raedeke & Smith, Citation2001) was taken to ensure consistency in the conceptualisation of burnout as multi-dimensional syndrome characterised by the dimensions of PEE, RSA and SD (Raedeke, Citation1997). Other proposed measures of burnout (e.g. EABI, Eades, Citation1990; MBI-GS, Schaufeli et al., Citation1996) do not measure these specific dimensions. The ABQ is regarded as having added significantly to research in the area (Gustafsson et al., Citation2017) and has emerged as the most widely-used and well-validated measure of athlete burnout (Gustafsson et al., Citation2014). Finally, studies (4) must have included participants from team sportsFootnote3, which could be disaggregated from other data if individual sports were also included. Systematic reviews, theoretical papers, dissertations and conference abstracts were also excluded.

Data extraction

Articles were screened by two independent reviewers (SW & AMcN), using Covidence software. Both reviewers had to reach agreement before an article was excluded or progressed to the next stage. A third reviewer (SD) was available if any conflicts could not be resolved. Reviewers screened titles and abstracts first. Papers that passed this stage moved forward to full-text review. The first author extracted and summarised the key characteristics of the papers that were eligible for inclusion, including (1) authors and year published, (2) population location, (3)sample size and gender breakdown, (4) age of participants, sport (5) level and (6) type, (7) study design, (8) the variable-burnout relationship(s) examined, including any (9) mediating, (10) moderating or (11) predictive relationships in longitudinal studies, and the (12) measures used. This information is outlined in .

Table 2. Descriptive data extracted from all studies included in this review.

Quality assessment

Each article was subject to quality appraisal, in-line with PRISMA (2009) guidelines. Two reviewers critically appraised the papers independently using the quantitative research quality appraisal guidelines set out by Jefferies et al. (Citation2012), which were informed by the checklist developed by Crombie (Citation1996). A third reviewer (SD) was available to consult where conflicts in quality appraisal could not be resolved. Articles received a score of 1 (met the criteria), 0.5 (partially fulfilled the criteria), or 0 (failed to meet the criteria) across 12 domains, including (1) clearly identified aims, (2) clear description of participant eligibility and recruitment strategy, (3) clear description of population features and design, (4) description of non-responders and non-participants, (5) inclusion of a control group, (6) justification of sample size, (7) relevant, (8) validated and adequately described measures, (9) adequate discussion of results, (10) limitations identified and acceptable, (11) statistical methods described and (12) statistical methods appropriate. Each paper was then rated as either poor quality (score of 0–4), adequate quality (score of 4.5–8), or good quality (score of 8.5–12), as per the cut-offs employed by Dunne and colleagues (Citation2017) when using the same items.

Data syntheses

The aim of this review was to synthesise the literature examining factors associated with athlete burnout in team sport. However, when considering the range of different factors examined, the limited number of studies examining each relationship, and the substantial variability in study design, it was evident that a traditional meta-analysis would not be appropriate. Specifically, the diversity in measures employed across studies and the limited number of papers for each variable-burnout dimension relationship did not allow for the accurate estimation and averaging of effect sizes associated with traditional methods of meta-analysis (Cerin et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, traditional methods, such as the random effects model, have been shown to be unreliable when used with a small number of studies (Borenstein et al., Citation2009), as was the case in this review. As three studies are the median number included in meta-analyses in Cochrane’s database (Davey et al., Citation2011), where no more than two studies examined a relationship this was classified as a ‘small number’ in the context of this review (Cerin et al., Citation2017). As such, a narrative synthesis was employed to summarise key findings, as outlined below. However, Borenstein et al. (Citation2009) note that the utility of a narrative synthesis is reduced where the number of studies involved increases. With the aim of addressing this issue where possible, providing greater clarity in data synthesis and ensuring appropriate conclusions could be drawn from this review, we also employed a conservative weighted meta-analytic technique devised by Cerin et al. (Citation2017), where variable-burnout dimension relationships had been examined across three or more independent samples of athletes. This method allowed us to quantitatively assess the strength of evidence for the burnout-correlate relationships that were most frequently examined in the literature, and has been employed in a range of existing studies (e.g. Barnett et al., Citation2018; Chandrabose et al., Citation2019).

Weighted meta-analysis (WMA)

We first categorised papers based on variable(s) examined in relation to burnout. Only variables that were examined in relation to the same dimension of burnout (i.e. total burnout, PEE, RSA, SD) in three or more independent samples of team-sport athletes were eligible for inclusion in the WMA (Cerin et al., Citation2017). Univariate correlations between each variable and the dimensions of burnout were extracted to allow for comparison across studies; each variable-burnout dimension relationship was coded as significantly positive (P), significantly negative (N), or not statistically significant (Ø; Cerin et al., Citation2017). Papers that reported on multiple different variable-burnout dimension relationships were counted as distinct findings (Cerin et al., Citation2017). Where papers reported multiple results for the same variable-burnout dimension relationship (e.g. at multiple time-points), each result was assigned a fractional weight, such that the summed weight of results for the same variable-burnout dimension relationship reported in each paper was 1.

Each paper was assigned a score for sample size (N; including team-sport athletes only), as follows; N ≤ 100 = 0.25, N 101–300 = 0.5, N 301–500 = 1.00, N 501–1000 = 1.25, N 1001–2500 = 1.5, and N > 2500 = 1.75 (Cerin et al., Citation2017). These sample size scores were combined with the quality appraisal score to create an ‘article weight’ (Cerin et al., Citation2017). Each P association was assigned a z-score of 1.96 and each N association was assigned a z-score of – 1.96 (Cerin et al., Citation2017). This z-score value is just significant at the p-level of 0.05 and, as such the results reported here-in are conservative. Statistically non-significant (Ø) associations were assigned a z-value of 0. In the final step, the ‘article weight’ was multiplied by the z-score to create a weighted z-value, which was then multiplied by the appropriate fractional weight. The p-values associated with the weighted z-value were then obtained, using a method developed by Rosenthal (Citation1980) and also employed by Cerin et al. (Citation2017). Two-tailed p-values <0.001 were recognised as providing evidence of very strong significant associations, while p-values <0.01 were seen to indicate evidence of strong significant associations (Bland, Citation2000; Cerin et al., Citation2017). P-values <0.05 were evidence of significant associations.

Narrative synthesis

Variables that did not meet the criteria for inclusion in the WMA were synthesised in a narrative results section. We also provided a narrative overview of the relationships identified in the WMA.

Results

General findings and sample characteristics of papers

We identified 12,109 records from our online search, with 55 papers meeting the criteria for inclusion in the review. The PRISMA diagram () outlines the steps at which the additional papers were excluded. Cohen’s Kappa (Cohen, Citation1960) indicated strong agreement in inter-rater reliability at both the title and abstract screening (κ = 0.86; McHugh, Citation2012) and full-text review phases (κ = 0.86). Conflicting decisions, for example where one reviewer failed to notice that team and individual sport data was not disaggregated, were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers, and the third reviewer was not required. We then manually searched the reference lists of these 55 papers and the five previously published reviews on athlete burnout (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Goodger et al., Citation2007; Li et al., Citation2013; Lin et al., Citation2021, Pacewicz et al., Citation2019); this consisted of 2,933 references, four of which were eligible for inclusion in the review ().

As such, 59 papers met the criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. There were 55 independent participant samples, as four pairs of papers used the same sample (viz. Gonzalez et al., Citation2017; Grobbelaar et al., Citation2010; Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2012; Lopes Verardi et al., Citation2015). As outlined in , 33 papers included a sample consisting of male participants only, 26 papers including a mixed-gender sample, and one included female athletes only (Amorose et al., Citation2009). Five papers did not specify the gender breakdown for team-sport athletes. As such, data was available from 8,723 male athletes, and 2,391 female athletes. Participants ranged in age from 10 to 60 years old. Athletes from a variety of different sports were examined; while the majority of papers included soccer (19 papers) and rugby players (ten papers), athletes from 16 other named team sports, namely volleyball (ten papers), basketball (eight papers), field hockey (five papers), handball (five papers), netball (four papers), cricket (2 papers), Gaelic games (two papers), baseball (two papers), ice hockey, roller hockey, water-polo, futsal, lacrosse, American football, softball and Ultimate Frisbee (one paper each), were also represented. European samples were by far the most common (32 papers; total N = 7706), followed by Oceania (seven papers; total N = 1555), Asia (six papers; total N = 980), North America (including Mexico; six papers, total N = 1247), and South America (five papers; 4 independent samples, total N = 465). There were two papers from South Africa (total N = 41), with the same sample used for both. Thirty-seven papers employed a cross-sectional design, with 22 using a longitudinal design. Sixteen papers also examined moderating/mediating relationships.

Of the 22 papers utilising a longitudinal design, ten papers gathered data at two time points; the gap between data collection points ranged from three to six months. Three papers reported on data from three time points, with the time between data collection varying from one month to ten weeks. Nine studies reported on data that had been gathered at ≥ 4 timepoints; data was collected over periods ranging from eight weeks (Turner & Moore, Citation2016), to 2½ years (Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2015). A male-only sample was used in 14 of the longitudinal papers, while a female-only sample was used in one (Amorose et al., Citation2009). Seven studies used a mixed-gender sample. In total, 2,677 male athletes were included in longitudinal studies, compared to 781 female athletes. Soccer (nine papers) and rugby (five papers) were the team sports examined most often in the longitudinal papers included.

Quality appraisal

Inter-rater reliability in independent quality appraisal indicated substantial agreement among the reviewers (κ = 0.8). Where there were conflicting scores, the reviewers discussed and agreed on a final value. As outlined in , 53 papers received a ‘good quality’ rating of 8.5 or above and six papers received an ‘adequate quality’ rating between 6.5 and 8. We found none of the papers to be of poor quality. Across the 12 criteria on which quality was appraised, all papers fully met the criterion of no evidence of selective reporting. Papers also consistently met, either in full or partly in a small a number of cases, the criteria for clearly stated aims, the description of features of population and design, appropriate use and adequate description of statistical methods, use of relevant, validated and adequately-described measures, and the adequate discussion of results. Only three papers met the criterion of sample size justification, with all other papers failing to do so. Finally, while some papers did provide some description of non-responders and non-participants, this criterion was not met in full by any paper (see Supplementary File 2).

Burnout correlates identified

Across the 59 papers included, 125 different variables have been examined in relation to total burnout (TB) or at least one dimension of burnout. The variables examined in each paper are outlined in . These variables can be grouped under 41 different overarching variables; for example, socially-prescribed perfectionism and self-oriented perfectionism are both forms of perfectionism.

Twenty variables were examined in ≥3 independent samples. However, the ‘playing position’ and ‘sport type’ variables could not be included in the WMA as we cannot assign a direction to the relationship (i.e. positive or negative) between these categorical variables and burnout, in-line with requirements for the analysis. As such, WMA was conducted to assess the relationships between 18 variables and athlete burnout. outlines the variable-burnout dimension relationships included in the WMA, paper reference numbers, the number of results reported (i.e. where papers report multiple findings for the same relationship), and whether the relationship(s) reported were P, N or Ø. The number of P, N and Ø relationships reported for each variable-burnout dimension relationship is outlined in .

Table 3. Breakdown of the papers examining each variable-burnout dimension relationship.

Table 4. Summary of associations between the dimensions of athlete burnout and the variables examined in relation to burnout, as per the weighted meta-analysis.

One-hundred-and-five variable-burnout relationships were not assessed in at least two other independent samples, and thus were not eligible for inclusion in the WMA. See the narrative synthesis section for results relating to these variables, as well as ‘sport type’ and ‘playing position’, and longitudinal and mediating/moderating relationships.

Weighted meta-analysis

The 39 papers examined using WMA included 36 independent participant samples, with three sets of papers using the same sample (viz. Gonzalez et al., Citation2017; Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2012). Nine over-arching variables, which are divided into 18 different correlates of athlete burnout, were examined (see ). For the purpose of analysis, papers examining self-oriented perfectionism (SOP) were included under personal standards perfectionism and those examining socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP) were included under evaluative concerns, as SOP and SPP are sub-dimensions of personal standards and evaluative concerns perfectionism respectively (Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991; Hill, Citation2013). The subscales of concern over mistakes, perceived parental pressure, and perceived coach pressure (Skwiot et al., Citation2020) were also included under the SPP dimension of perfectionism (Dunn et al., Citation2006). Perceived social support, actual social support received and satisfaction with social support (DeFreese & Smith, Citation2013b) were included under the social support variable. In-line with the method outlined above, where multiple subscales were used to assess the same overarching variable-burnout dimension relationship, a fractional weight was assigned such that the total weight of the paper was 1.

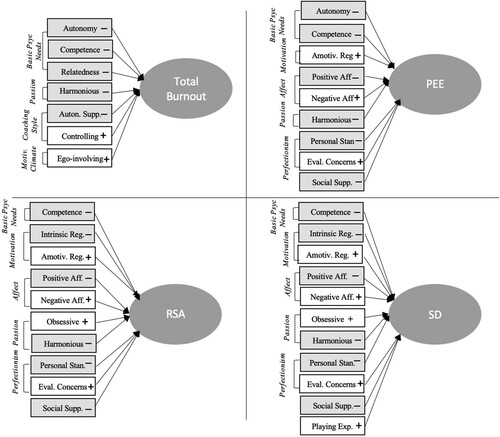

As outlined in , sufficient papers were available to conduct WMA across TB, PEE, RSA and SD for the competence, harmonious passion and obsessive passion variables only. WMA were conducted across PEE, RSA and SD for nine of the variables and across TB and PEE for three variables. Three variables were analysed in relation to TB alone. This resulted in a total of 48 independent WMA, the results of which are outlined in and below. Significant relationships identified for TB, PEE, RSA and SD are also outlined in .

Narrative synthesis of results

Variables examined in the WMA

Correlates of TB

There was evidence of a very strong significant negative association (p < 0.001) between TB and satisfaction of the basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence, autonomy-supportive coaching style, and harmonious passion. There was evidence of a very strong significant positive association between TB and a controlling coaching style, and a slightly weaker significant positive association between TB and an ego-involving motivational climate (p = 0.02). No significant relationship was evident between task-involving climate or obsessive passion and TB.

Correlates of PEE

There was evidence of very strong significant positive associations (p < 0.001) between PEE and amotivated regulation, negative affect and socially-prescribed perfectionism, and a very strong (p < 0.001) significant negative association between PEE and social support. There was evidence of a strong significant negative relationship (p < 0.01) between PEE and autonomy, positive affect and personal standards perfectionism, and weaker evidence of a negative association between both competence (p = 0.03) and harmonious passion (p = 0.03) and PEE. No statistically significant association was evident between PEE and the remaining variables assessed, including relatedness, intrinsic regulation, extrinsic/external motivation, autonomy-supportive coaching style, obsessive passion and playing experience.

Correlates of RSA

There was evidence of a very strong signficant negative association (p < 0.001) between both social support and harmonious passion and RSA, and a very strong (p < 0.001) positive association between RSA and amotivated regulation, negative affect, obsessive passion and evaluative concerns perfectionism. There was further evidence of strong negative associations (p < 0.01) between RSA and competence, intrinsic regulation and positive affect, and slightly weaker evidence of a negative association (p = 0.02) with personal standards perfectionism. No evidence of a statistically significant association was found between RSA and either playing experience or extrinsic/external motivation.

Correlates of SD

WMA revealed evidence of a very strong negative association (p < 0.001) between SD and intrinsic regulation, personal standards perfectionism and social support, and a strong positive association with amotivated regulation and negative affect. Further evidence of a strong negative relationship (p < 0.01) between SD and both competence and positive affect, and a positive association between SD and evaluative concerns perfectionism also emerged. There was a weaker positive correlation (p = 0.04) between both obsessive passion (p = 0.02) playing experience (p = 0.04) and SD, while harmonious passion showed a significantly, but slightly weaker, negative correlation with SD (p = 0.02).

Additional cross-sectional relationships

Narrative syntheses of the additional 107 variables assessed in relation to at least one dimension of burnout are provided in .

Table 5. Narrative synthesis of results relating to variables ineligible for inclusion in the weighted meta-analysis.

Longitudinal relationships

Twenty-two papers included in this review employed a longitudinal research design, where-in data was gathered at multiple timepoints and researchers assessed whether burnout at a later time-point was predicted by scores on a related variable at an earlier timepoint. Fourteen different overarching variables, with 33 specific subscales, were examined as predictors of burnout at later time-points. A narrative synthesis of the results are provided in . Time in the season, age and the overall and sport-specific stress and recovery subscales (Fagundes et al., Citation2021) are the only variables that were not also examined cross-sectionally.

Table 6. Narrative synthesis of longitudinal research examining factors that may predict or protect against the development of athlete burnout.

Mediating and moderating relationships

Fifteen variables were examined as possible mediators and four variables were examined as moderators of variable-burnout dimension relationships, across seventeen papers.

Basic psychological needs

The basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness, either grouped or as individual variables, were the most commonly assessed mediators, examined in six papers. The following relationships were identified: thwarting of psychological needs in combination (Balaguer et al., Citation2012; Gonzalez et al., Citation2016), and the relatedness and competence needs specifically (Gonzalez et al., Citation2017), mediated the positive relationship between controlling coach style and TB; the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, both in combination and individually, mediated the positive relationship between TB and harmonious passion (Curran et al., Citation2013), transformational parenting (Alvarez et al., Citation2019), and autonomy-supportive coaching style (Gonzalez et al., Citation2016; Gonzalez et al., Citation2017) respectively; satisfaction of competence and autonomy partially mediated the relationship between autonomy supportive coaching style and RSA, but not PEE or SD (Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2012); neither relatedness nor autonomy mediated the relationship between controlling coach style and any of the burnout dimensions (Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2012).

Affect

Positive affect mediated the negative relationships between prosocial behaviour and TB (Al-Yaaribi & Kavussanu, Citation2017) and hope and PEE (Gustafsson et al., Citation2013), and partially mediated the relationship between hope and RSA and SD. Negative affect mediated the positive relationship between antisocial behaviour and TB (Al-Yaaribi & Kavussanu, Citation2017) and had no mediating effect on the relationship between hope and any burnout dimension (Gustafsson et al., Citation2013).

Stress

Stress mediated the negative relationship between hope and PEE, and partially mediated the relationship between hope and RSA and SD (Gustafsson et al., Citation2013). Perceived distress mediated the effect of life stress on increased TB (Chyi et al., Citation2018).

Regulation

Self-determined regulation mediated the negative relationship between harmonious passion and TB (Curran et al., Citation2011), identified regulation partially mediated the negative relationship between perceived autonomy supportive coaching style and RSA, and external regulation partially mediated the negative relationship between perceived competence and RSA (Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2012).

Other

Cognitive appraisal mediated the positive relationship between trait anxiety and TB (Gomes et al., Citation2017), unconditional self-acceptance partially mediated the relationship between both dimensions of perfectionism and TB (Hill et al., Citation2008), and coping mediated the negative relationship between passion and change in burnout (Schellenberg et al., Citation2013). Social support mediating the relationship between both harmonious passion and TB and positivity and TB (Martínez-Alvarado et al., Citation2021). Playing level mediated the relationship between coping and RSA (da Silva et al., Citation2021).

Moderating variables

Total athletic mental energy and the subscales of confidence, concentration and calm moderated the positive impact of sport-specific stress on TB. Total athletic mental energy and the concentration subscale moderated the positive relationship between general life stress and TB (Chiou et al., Citation2020). Gender moderated the impact of increasing age on SD; female athletes showed a greater increase in SD with age than males. No significant moderating effects of gender were identified for PEE or RSA (Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2015). Sport type (team v. individual) did not moderate the impact of coach-athlete relationship quality on burnout (Davis et al., Citation2019).

Direct relationship between these variables and dimensions of burnout are outlined in the WMA or narrative synthesis, as appropriate.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to synthesise the research on burnout in team-sport athletes and, where possible, to identify the variables that show significant associations with the dimensions of burnout using a conservative weighted meta-analytic technique. We identified 59 papers that have examined a total of 125 variables in relation to athlete burnout in team sports. Relationships between 18 variables and at least one dimension of burnout were eligible for inclusion in a WMA. The remaining 107 variables were included in a narrative synthesis, in order to ensure all eligible papers were represented in this review.

Through the WMA, which allowed us to assess the strength of relationships across studies, we identified 37 significant variable-burnout relationships, linking 16 variables to TB or at least one dimension of burnout in team-sport athletes; results indicate that there is sufficient evidence in the research conducted to-date to support a significant negative association between autonomy, competence, relatedness, self-determined motivation, positive affect, autonomy supportive coach, self-oriented perfectionism, harmonious passion and social support and various dimensions of burnout, while amotivation, negative affect, socially-prescribed perfectionism, obsessive passion, ego-involving climate, playing experience and controlling coach style were significantly positively related to burnout. As a result of our decision to expand the inclusion criteria beyond the limited scope of previous reviews (e.g. Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2013; Lin et al., Citation2021; Pacewicz et al., Citation2019) five of these variables, namely ego-involving motivational climate, playing experience, positive affect, and both autonomy supportive and controlling coaching style have been included in a review of the burnout literature for the first time, highlighting their impact on burnout in team-sport athletes. Task-involving climate was also included in a review of the literature for the first time; the results of the WMA suggest this variable does not significantly impact burnout in team sports.

Relevance to existing theoretical perspectives of athlete burnout

In the context of existing theories of athlete burnout, and in-line with Li et al.’s (2013) review, results of the WMA appear to provide the most substantial support for the SDT motivation-based perspective of burnout; higher levels of self-determined motivation and feelings of autonomy, competence and relatedness, as well as an autonomy-supportive coaching style are associated with lower burnout, while an ego-orientated climate and controlling coaching style have an opposing impact. The emergence of these relationships in the WMA suggest burnout in team-sport is more commonly examined from the SDT motivation-based perspective. In addition, the broader focus of our review also reveals support for other theoretical frameworks, for example the negative relationship between social support and burnout is in-line with that suggested by the sport commitment perspective of burnout (Raedeke, Citation1997). However, while additional studies providing support for the stress-based (e.g. Gustafsson et al., Citation2011) and commitment-based (e.g. Woods et al., Citation2020) perspectives were also identified, the number of studies exploring these relationships in team-sport athletes appears to be more limited and therefore they were not eligible for inclusion in the WMA. The partial support evidence for multiple models supports calls for further critical review of existing theories (Madigan et al., Citation2021).

Consistency of relationships across burnout dimensions

Our focus on studies using the ABQ allowed us to examine the impact and consistency of correlates of burnout across TB and the dimensions of PEE, RSA and SD. Of the 15 variables that were examined across multiple dimensions of burnout using WMA, only amotivated regulation and negative affect showed evidence of a very strong significant association with all three dimensions, suggesting that team-sport athletes who report higher levels of amotivated regulation or negative affect are more likely to experience increased feelings of PEE, RSA and SD. These results are in-line with previous reviews examining a mix of individual and team-sport athletes (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2013).

However, variability in the evidence of relationships between the remaining variables and the different burnout dimensions, which was evident through the use of the WMA technique, serves to highlight the importance of the multi-dimensional conceptualisation of athlete burnout (Pacewicz et al., Citation2019; Raedeke & Smith, Citation2001). Specifically, in the case of intrinsic motivation, obsessive passion, playing experience, relatedness and autonomy-supportive coach style, different results emerged in relation to PEE, RSA, SD and TB; there was very strong evidence suggesting intrinsic motivation is significantly associated with lower levels of both RSA and SD, but there was no significant relationship with PEE. Similarly, there was a strong significant negative association between relatedness and TB, but a non-significant relationship between this variable and PEE. These results are in contrast to results from previous reviews (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2013), in which relatedness and both intrinsic and self-determined motivation showed consistent significant relationships across the burnout dimensions, suggesting that these variables may not only have a differential impact across burnout dimensions, but also on team-sport athletes compared to elite/mixed-sport athletes. Inconsistencies in the association between obsessive passion and the dimensions of burnout identified here also emerged in Bicalho and Costa’s (Citation2018) review, although the relationships themselves differ; they found positive associations with PEE and RSA and negative association with SD, while we identified positive associations with both RSA and SD, and no significant association with PEE. This variability is also evident in the correlates examined in a review for the first time; there was an absence of a significant association between playing experience and PEE or RSA, despite evidence of a strong association with SD, while the strong association between autonomy-supportive coach style and TB, was not evident with the PEE dimension, suggesting these variables may not impact all aspects of burnout equally.

In addition, while the WMA revealed that competence, positive affect, personal standards perfectionism and social support all showed significant negative associations with the dimensions of burnout, the use of the WMA also highlighted that the strength of the associations between these variables and the burnout dimensions did differ, ranging from very strong to weaker associations. In the context of the existing literature, while weaker associations between both competence and social support and PEE in comparison to RSA and SD were also reported by Li et al. (Citation2013) and Pacewicz and colleagues (Citation2019) respectively, the results of our WMA show RSA has the weakest association with personal standards/self-oriented perfectionism, which is in contrast to Bicalho and Costa (Citation2018) review, where-in a very strong association with RSA is reported. This suggests this variable may be less important in relation to RSA in team-sport athletes. Finally, extrinsic motivation and task involving climate were the only variables that showed no significant association with any of the dimensions of burnout with which they were examined. While task-involving climate has been assessed here for the first time, results relating to extrinsic motivation are in contrast to previous reviews, which reported relationships ranging from indeterminate (Goodger et al., Citation2007) to significant positive associations with PEE and SD, and a negative association with RSA (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018). The WMA provided key insight into the complexities of these relationships, and highlights the importance of assessing each variable-burnout dimension relationship individually; a clearer understanding of the key factors associated with each dimension of burnout can inform a more nuanced approach for interventions aimed at reducing or preventing the onset of PEE, RSA or SD specifically. Furthermore, additional variability in some of these relationships when compared to past reviews of mixed-sport samples suggests that some burnout correlates may have a differential impact on athletes operating within different sports, which both provides novel and nuanced insight into potential differences in these populations, and again may have implications for targeted intervention and prevention strategies. For example, while Li et al. (Citation2013) identified the feeling of relatedness as a factor strongly negatively related to PEE in a mixed sample of elite athletes, the results of this review suggest that this variable does not significantly impact this dimension of burnout in team sports athletes specifically.

Breadth of the existing research

A summary of an additional 107 variable-burnout relationship was provided in a narrative table. These variables are diverse, including injury rate (Cresswell & Eklund, Citation2006), intra-team conflict (Smith et al., Citation2010), resilience (Vitali et al., Citation2015) and hope (Gustafsson et al., Citation2013), among a host of others. While this narrative synthesis provides a useful overview of the results reported to-date, our understanding of the relationships between these variables and burnout in team-sport athletes would benefit from additional replication research and subsequent meta-analyses; with over 100 variables examined across just one or two independent samples of team-sport athletes, it appears there is a focus in the literature on continuing to explore new correlates of burnout, at the expense of replication studies. This is reflective of ‘psychology’s replication crisis’ (Hughes, Citation2018, p. 6), and suggests that the apparent ‘scattergun approach’ identified by Goodger and colleagues (Citation2007, p.144) in their review over a decade ago continues to be an issue in the athlete burnout literature. As such, we suggest the need for more focused replication studies on athlete burnout in team sports. Furthermore, and in-line with recommendations for the future of burnout research (Madigan et al., Citation2021), we suggest the most useful starting point for such work would be critical exploration of existing theories of athlete burnout; as outlined previously, this review found support for aspects of these theories (e.g. negative association between intrinsic regulation and burnout), but more research is needed to allow us to examine the strength of these relationships across studies, and, more importantly, their predictive ability (Madigan et al., Citation2021). This includes a need to explore variables associated with the commitment (Raedeke, Citation1997), stress (Smith, Citation1986) and the motivation (Horn & Smith, Citation2018) perspectives, and their links with each of the three dimensions of burnout over time.

With the aim of providing an accurate representation of the quantitative research on team-sport athletes to-date, we also included a narrative synthesis of longitudinal and mediating/moderating relationships examined in the literature. The sixteen different variable types (33 unique variables) that have been examined longitudinally in relation to athlete burnout in team-sports are a substantial increase on those that have emerged in previous reviews, where-in the number of variables examined longitudinally ranged from two (Li et al., Citation2013) to nine (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018). In addition, previous reviews have provided no analysis or synthesis of the longitudinal relationships in the literature. Our synthesis indicates that lower levels of burnout were predicted by approach-focused goal setting, the fulfilment of basic psychological needs, optimism, sport-specific recovery, social support and autonomy supportive coach style in the existing literature. In contrast, higher levels of burnout were predicted by avoidance-focused goals, disengagement-orientated coping, amotivated regulation, self-determined index of motivation, stress, teammate burnout, controlling coach style and increased training hours. Longitudinal research is essential in identifying the factors that might predict or protect against the development of athlete burnout and, as outlined previously, we suggest researchers continue to prioritise longitudinal work moving forward.

The range of mediators/moderators of burnout-correlate relationships also highlight the complex nature of athlete burnout and its associated variables; results suggest that variables such as the fulfilment of basic psychological needs, affect, stress and regulation can mediate the impact of a range of burnout correlates. The summary provided of these relationships can improve our understanding of the mechanisms through which burnout occurs in team-sport athletes, and may again have important implications for the development of a model of burnout. Furthermore, this synthesis is an important addition that has been absent from previous systematic reviews of the burnout literature (e.g. Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2013, Pacewicz et al., Citation2019).

Characteristics of team-sport studies

Finally, examination of the characteristics of the papers included in this review is also revealing; while North American samples dominate the literature included in previous reviews of mixed-sport athletes (e.g. Goodger et al., Citation2007), the vast majority of samples in this review were drawn from European countries, followed by countries from Oceania. In line with existing reviews (e.g. Li et al., Citation2013), Western nations are significantly over-represented in comparison to Asian, African or South American populations. Henrich et al. (Citation2010) have previously highlighted the tendency for the psychological literature to focus on samples from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic) societies. In relation to gender, just 23 papers included a mixed-gender sample, in comparison to the 34 mixed-gender sample papers included in the recent review of burnout in elite mixed-sport athletes (Bicalho & Costa, Citation2018). Taking participant numbers into consideration, males comprised over 70% of the sample of athletes included in this review. The lack of gender balance in the papers examined may be linked to the fact that, when accessing players in team sports, researchers appear to look to specific teams (e.g. Grobbelaar et al., Citation2011), academies (e.g. Curran et al., Citation2011), or leagues (e.g. Cresswell, Citation2009), which tend to be gender-specific in team sports. Regardless of the reasoning, female team-sport athletes appear to be seriously under-represented in the burnout literature. The importance of understanding the experiences of female athletes in the still-male-dominated world of sport continues to be stressed in the feminist literature (e.g. Roper & Polasek, Citation2019). The need for a gender-balanced approach is further evident when considering differences in levels of burnout that have been identified between male and female athletes in some of the existing literature (e.g. Isoard-Gautheur et al., Citation2015; Reche et al., Citation2018).

Strengths and limitations of this review

While we believe this review adds substantially to our understanding of burnout in team-sport athletes, we also acknowledge some limitations of our work. Firstly, this review is only representative of the existing English-language papers. Secondly, qualitative research or studies using measures of burnout other than the ABQ (Raedeke & Smith, Citation2001) are not represented. However, these criteria were employed with the aim of ensuring burnout was conceptualised and assessed in a consistent, multi-dimensional manner across studies, using the most well-accepted and commonly used definition and measure of the syndrome (Gustafsson et al., Citation2011). Such consistency in measurement, which was particularly important to allow for data synthesis across studies, cannot be guaranteed in the case of qualitative studies or those using alternative measures of athlete burnout. This review is also limited by the inclusion of published work only; this leads to a risk of results being impacted by publication-bias, whereby studies with significant results are more likely to be published than those reporting non-significant results (Joober et al., Citation2012), and the possibility that additional correlates of burnout in team-sport athletes exist in the grey literature. However, the decision to focus on published research was made with the aim of ensuring that the studies included had been rigorously scrutinised by experts in the area through the peer review process, which is not the case for grey literature (Gunnell et al., Citation2020). We recommend that future systematic reviews build on this work by expanding the search beyond English-language and quantitative-only papers. Furthermore, a move towards pre-registration of studies in this area could help to ensure future reviews of this kind are not impacted by potential publication bias or the ‘file drawer effect’.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this review has a number of strengths. This is the first systematic review and WMA to assess the variables related to burnout in team-sport athletes specifically, without limiting these variables to any one category. Furthermore, where the burnout dimensions were delineated, data was examined separately in this review for TB and the subscales of PEE, RSA and SD, in order to further our understanding of the potential differential impact of variables across these dimensions. While a traditional meta-analysis was not possible due to the limited number of studies for each variable-burnout dimension relationship and the considerable heterogeneity in variable measures (Borenstein et al., Citation2009; Cerin et al., Citation2017), the use of the WMA (Cerin et al., Citation2017) in addition to the narrative synthesis allowed us to assess the strength of the evidence in relation to variable-burnout dimension relationships examined most frequently, and thus to identify the variables that appear to be strongly related to burnout in team-sport athletes. We feel the combination of narrative synthesis and WMA ensures the breadth of the existing literature is represented and provides an accessible synthesis of the burnout literature to-date.

Implications and conclusions

The results of this review highlight the variables that are impacting burnout in team-sport athletes. Findings also point to variability in some relationships across the dimensions of burnout, and suggest that the team-sport population may differ from mixed-sample athletes, both in terms of some the relationships reported, and the characteristics of the sample. Identifying the key factors associated with PEE, RSA and SD in team-sport athletes can inform applied practitioner work and the development of intervention strategies targeted to address specific burnout symptoms. While research on interventions for athlete burnout is currently very limited (Madigan, Citation2021), Langan et al. (Citation2015) report positive results from their randomised-control trial, whereby a group of team-sport coaches received fortnightly, one-to-one training on the use of ten strategies designed to increase their provision of autonomy, competence and relatedness support, and reduce controlling style. Results indicated that team-sport athletes working under coaches enrolled in the intervention did not show increases in burnout over a season, while a control group did. Our findings provide further support for the importance of policies or interventions aimed at promoting feelings of autonomy, competence, relatedness and autonomy supportive coaching, and also suggest that similar one-to-one training for both coaches and players related to the promotion of self-determined motivation, positive affect, social support and self-oriented perfectionism among team-sport athletes may reduce the risk of burnout. Such interventions may also be useful for targeting reductions in feelings of amotivation, negative affect and socially-prescribed perfectionism among team-sport athletes. Those working with team-sport athletes who have greater playing experience should also be aware of a potentially increased risk of burnout.

Finally, the wide variety of burnout correlates included in this review has served to highlight the breadth of research in the area, while also pointing to a need for replication studies to improve our depth of understanding. As such, we recommend that future research focuses on increasing replication studies and longitudinal work with correlates of burnout identified to-date. Specifically, in line with Madigan and colleagues (Citation2021), we suggest that exploring the predictive utility of existing theories of athlete burnout may be a useful direction for future research. In addition, such work may benefit from distinguishing between team and individual-sport athlete populations and focusing on increasing female athlete representation, and should continue to examine burnout as a multi-dimensional syndrome in order to gather a more nuanced insight into the factors associated with athlete burnout. Such research has the potential to both inform targeted interventions for the prevention and treatment of athlete burnout, and contribute to the development of a comprehensive theoretical model of athlete burnout.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (S. W.), upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Systematic reviews involve the use of “systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included” (Moher et al., Citation2009, p. 1).

2 Meta-analyses involve summarizing effect sizes of studies examining the same hypothesis, using a weighted measure of central tendency and information on the uncertainty of the measure (Borenstein et al., Citation2009; Siddaway et al., Citation2019).

3 For this review, team sports are operationalised as those in which one can compete as part of a group of 2 or more players only, and no individual competition exists, such as soccer or basketball (e.g. Gustafsson et al., Citation2016; Reche et al., Citation2018).

References

- Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2008). Autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the optimal functioning of adult male and female sport participants: A test of basic needs theory. Motivation and Emotion, 32(3), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9095-z

- Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2012). Perceived coach-autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the well- and ill-being of elite youth soccer players: A longitudinal investigation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.07.008

- Ahmed, D., Yan Ho, W. K., & Lee, K.-C. (2015). Ballgames and burnout. Journal of Physical Education & Sport, 15(3), 378–383. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2015.03056

- Alvarez, O., Castillo, I., & Moreno-Pellicer, R. (2019). Transformational parenting style, autonomy support, and their implications for adolescent athletes’ burnout. Intervencion Psicosocial, 28(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a7

- Al-Yaaribi, A., & Kavussanu, M. (2017). Teammate prosocial and antisocial behaviors predict task cohesion and burnout: The mediating role of affect. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 39(3), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2016-0336

- Amorose, A. J., Anderson-Butcher, D., & Cooper, J. (2009). Predicting changes in athletes’ well being from changes in need satisfaction over the course of a competitive season. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 80(2), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2009.10599575

- Appleby, R., Davis, P., Davis, L., & Gustafsson, H. (2018). Examining perceptions of teammates’ burnout and training hours in athlete burnout. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 12(3), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2017-0037

- Baella-Vigil, G. V., Hurtado-Bocanegra, M., Marroquín-Quintana, J., Rojas-Fernández, M. V., Rosales-Medina, J. M., Urbina-Rodríguez, J. C., Tarabay-Barriga, A. P., & Carreazo, N. Y. (2020). Burnout syndrome in athletes and their association with body image dissatisfaction at a private university. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 60(4), 650–655. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0022-4707.19.07965-9

- Balaguer, I., Gonzalez, L., Fabra, P., Castillo, I., Merce, J., & Duda, J. L. (2012). Coaches’ interpersonal style, basic psychological needs and the well- and ill-being of young soccer players: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1619–1629. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.731517

- Barnett, A., Zhang, C. J., Johnston, J. M., & Cerin, E. (2018). Relationships between the neighbourhood environment and depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(8), 1153–1176. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021700271X

- Bicalho, C. C. F., & Costa, V. T. (2018). Burnout in elite athletes: A systematic review. / Burnout en atletas de elite: Una revisión sistemática. Cuadernos de Psicología Del Deporte, 18(1), 89–101.

- Bland, M. (2000). Introduction to medical statistics (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Cerin, E., Nathan, A., Van Cauwenberg, J., Barnett, D. W., & Barnett, A. (2017). The neighbourhood physical environment and active travel in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0471-5

- Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Thomas, J., Higgins, J. P. T., Decks, J. J., & Clarke, J. J. (2019). Chapter 1: Introduction. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. Page, & V. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions versions 6.0. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Chandrabose, M., Rachele, J. N., Gunn, L., Kavanagh, A., Owen, N., Turrell, G., Giles-Corti, B., & Sugiyama, T. (2019). Built environment and cardio-metabolic health: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obesity Reviews, 20(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12759

- Chen, L. H., Kee, Y. H., Chen, M.-Y., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2008). Relation of perfectionism with athletes’ burnout: Further examination. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 106(3), 811–820. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.106.3.811-820

- Cheval, B., Chalabaev, A., Quested, E., Courvoisier, D. S., & Sarrazin, P. (2017). How perceived autonomy support and controlling coach behaviors are related to well- and ill-being in elite soccer players: A within-person changes and between-person differences analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 28, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.10.006

- Chiou, S. S., Hsu, Y., Chiu, Y. H., Chou, C. C., Gill, D. L., & Lu, F. J. (2020). Seeking positive strengths in buffering athletes’ life stress–burnout relationship: The moderating roles of athletic mental energy. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3007. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03007

- Chyi, T., Lu, F. J.-H., Wang, E. T. W., Hsu, Y.-W., & Chang, K.-H. (2018). Prediction of life stress on athletes’ burnout: The dual role of perceived stress. Peerj, 6, e4213. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4213

- Coakley, J. (1992). Burnout among adolescent athletes: A personal failure or social problem? Sociology of Sport Journal, 9(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.9.3.271

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

- Cremades, J. G., Wated, G., & Wiggins, M. S. (2011). Multiplicative measurements of a trait anxiety scale as predictors of burnout. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 15(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2011.594356

- Cremades, J. G., & Wiggins, M. S. (2008). Direction and intensity of trait anxiety as predictors of burnout among collegiate athletes. Athletic Insight, 10(2), 5–5.

- Cresswell, S., & Eklund, R. (2004). Athlete burnout: A longitudinal qualitative study. The Sport Psychologist, 21(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.1.1.

- Cresswell, S. L. (2009). Possible early signs of athlete burnout: A prospective study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 12(3), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2008.01.009

- Cresswell, S. L., & Eklund, R. C. (2005a). Changes in athlete burnout and motivation over a 12-week league tournament. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 37(11), 1957–1966. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000176304.14675.32

- Cresswell, S. L., & Eklund, R. C. (2005b). Motivation and burnout among top amateur rugby players. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 37(3), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000155398.71387.C2

- Cresswell, S. L., & Eklund, R. C. (2005c). Motivation and burnout in professional rugby players. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 76(3), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2005.10599309

- Cresswell, S. L., & Eklund, R. C. (2006). Changes in athlete burnout over a thirty-week ‘rugby year’. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 9(1–2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2006.03.017

- Crombie, I. K. (1996). The standard appraisal questions. In B.J. Harvey (Ed.), The pocket guide to critical appraisal: A handbook for health care professionals (pp. 23–29). MBJ Publishing Group.

- Curran, T., Appleton, P. R., Hill, A. P., & Hall, H. K. (2011). Passion and burnout in elite junior soccer players: The mediating role of self-determined motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(6), 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.06.004

- Curran, T., Appleton, P. R., Hill, A. P., & Hall, H. K. (2013). The mediating role of psychological need satisfaction in relationships between types of passion for sport and athlete burnout. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(6), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.742956

- da Silva, A. A., Freire, G. L. M., de Moraes, J. F. V. N., de Souza Fortes, L., da Silva Carvalho, R. G., & do Nascimento Junior, J. R. A. (2021). Association of coping strategies with symptoms of burnout in young football players in a career transition phase: Are professionalization and occurrence of injuries mediating factors? The Sport Psychologist, 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2020-0031

- Davey, J., Turner, R. M., Clarke, M. J., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2011). Characteristics of meta-analyses and their component studies in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: a cross-sectional, descriptive analysis. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-160.

- Davis, L., Stenling, A., Gustafsson, H., Appleby, R., & Davis, P. (2019). Reducing the risk of athlete burnout: Psychosocial, sociocultural, and individual considerations for coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(4), 444–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954119861076

- De Francisco, C., Arce, C., del Pilar Vílchez, M., & Vales, Á. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of burnout in athletes: Perceived stress and depression. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 16(3), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.04.001

- DeFreese, J. D., & Smith, A. L. (2013b). Teammate social support, burnout, and self-determined motivation in collegiate athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(2), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.10.009

- DeFreese, J. D., & Smith, A. L. (2013a). Areas of worklife and the athlete burnout-engagement relationship. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 25(2), 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2012.705414

- Dubuc-Charbonneau, N., & Durand-Bush, N. (2015). Moving to action: The effects of a self-regulation intervention on the stress, burnout, well-being, and self-regulation capacity levels of university student-athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 9(2), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2014-0036

- Dubuc-Charbonneau, N., Durand-Bush, N., & Forneris, T. (2014). Exploring levels of student-athlete burnout at two Canadian universities. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v44i2.183864

- Dunn, J. G., Dunn, J. C., Gotwals, J. K., Vallance, J. K., Craft, J. M., & Syrotuik, D. G. (2006). Establishing construct validity evidence for the Sport Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7(1), 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2005.04.003

- Dunne, S., Mooney, O., Coffey, L., Sharp, L., Desmond, D., Timon, C., O'Sullivan, E., & Gallagher, P. (2017). Psychological variables associated with quality of life following primary treatment for head and neck cancer: a systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2015. Psycho-oncology, 26(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4109

- Eades, A. M. (1990). An investigation of burnout of intercollegiate athletes: The development of the Eades Athlete Burnout Inventory [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of California, Berkeley.

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3adaa

- Esmaeili, M. R., Nowzari, V., Ghafouri, F., & Nazarian Madavani, A. (2012). The relation between coaches’ decision-making styles to the rate of satisfaction & burnout of Iran men & women basketball of preferred league players. Journal of American Science, 8(12), 671–675. (ISSN: 1545-1003). http://www.jofamericanscience.org

- Fagundes, L. H. S., Noce, F., Albuquerque, M. R., de Andrade, A. G. P., & Teoldo da Costa, V. (2021). Can motivation and overtraining predict burnout in professional soccer athletes in different periods of the season? International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1655778

- Gabana, N. T., Steinfeldt, J., Wong, Y. J., Chung, Y. B., & Svetina, D. (2019). Attitude of gratitude: Exploring the implementation of a gratitude intervention with college athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1498956

- Gomes, A. R., Faria, S., & Vilela, C. (2017). Anxiety and burnout in young athletes: The mediating role of cognitive appraisal. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 27(12), 2116–2126. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12841

- Gonzalez, L., Garcia-Merita, M., Castillo, I., & Balaguer, I. (2016). Young athletes’ perceptions of coach behaviors and their implications on their well- and ill-being over time. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(4), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001170

- Gonzalez, L., Tomas, I., Castillo, I., Duda, J. L., & Balaguer, I. (2017). A test of basic psychological needs theory in young soccer players: Time-lagged design at the individual and team levels. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 27(11), 1511–1522. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12778

- Goodger, K., Gorely, T., Lavallee, D., & Harwood, C. (2007). Burnout in sport: A systematic review. The Sport Psychologist, 21(2), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.2.127

- Grobbelaar, H. W., Malan, D. D. J., Steym, B. J. M., & Ellis, S. M. (2011). The relationship between burnout and mood state among student rugby union players. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation & Dance, 17(4), 647–664.

- Grobbelaar, H. W., Malan, D. D. J., Steyn, B. J. M., & Ellis, S. M. (2010). Factors affecting the recovery-stress, burnout and mood state scores of elite student rugby players. South African Journal for Research in Sport Physical Education and Recreation, 32(2), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajrs.v32i2.59296

- Gunnell, K., Poitras, V. J., & Tod, D. (2020). Questions and answers about conducting systematic reviews in sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1695141

- Gustafsson, H., DeFreese, J. D., & Madigan, D. J. (2017). Athlete burnout: Review and recommendations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.05.002

- Gustafsson, H., Hancock, D. J., & Cote, J. (2014). Describing citation structures in sport burnout literature: A citation network analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(6), 620–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.001

- Gustafsson, H., Kenttä, G., & Hassmén, P. (2011). Athlete burnout: An integrated model and future research directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2010.541927

- Gustafsson, H., Kentta, G., Hassmen, P., & Lundqvist, C. (2007). Prevalence of burnout in competitive adolescent athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 21(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.1.21

- Gustafsson, H., Lundkvist, E., Podlog, L., & Lundqvist, C. (2016). Conceptual confusion and potential advances in athlete burnout research. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 123(3), 784–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031512516665900

- Gustafsson, H, Madigan, D J, & Lundkvist, E. (2018). Burnout in Athletes. In R. Fuchs & M. Gerber (Eds.), Handbuch Stressregulation und Sport (pp. 489–504). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Gustafsson, H., Skoog, T., Podlog, L., Lundqvist, C., & Wagnsson, S. (2013). Hope and athlete burnout: Stress and affect as mediators. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(5), 640–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.03.008

- Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

- Hill, A. P. (2013). Perfectionism and burnout in junior soccer players: A test of the 2 × 2 model of dispositional perfectionism. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 35(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.35.1.18