?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Wegner's theory of ironic processes of mental control emphasizes how the implementation of cognitive load-induced avoidant instructions can cause inefficient motor cognition in sports, thereby inducing so-called ironic effects where an individual—ironically—does precisely what s(he) intended not to do. This systematic review synthesizes relevant existing research and evaluates the effectiveness of experimental manipulations and cognitive load measurements for investigating ironic effects on motor task performance under pressure conditions. This review identified twenty-four empirical studies published before January 2022, including studies with experimental (21%) and quasi-experimental (79%) within- and between-subject designs. The most common reported pressure (i.e., cognitive load) manipulations fell into two categories: anxiety (77%) and dual-task (33%) techniques. The review also identified positive action-oriented instructional interventions to reduce ironic errors. Although most reported findings supported Wegner's assumptions about ironic performance effects, the review also identified inconclusive evidence (8%), which indicates a need for more research with a greater focus on: robust experimental design; the inclusion of competitive stressors; expert athletes; elite athletes; and intervention-based studies. These additions will clarify the mechanisms of ironic effects and assist in the development of interventional programs to diminish the likelihood of ironic effects in sports performance.

Introduction

In 2021, Novak Djokovic, the winner of 20 Grand Slams, prepared to play the US Open Final against second-seed Daniil Medvedev. Djokovic was keen to become the first player since Rod Laver in 1969 to win all four majors in the same calendar year. Djokovic also knew that he would be ranked as one of the greatest tennis players of all time if he won this match (Walker-Roberts, Citation2021). Djokovic arrived at the court under overwhelming pressure. He played frailly and apprehensively—in the first two sets—struggling to fight back both physically and emotionally. Despite his efforts, he lost the Grand Slam (Berman, Citation2021). After the match, Djokovic admitted that he could not cope with the pressure and expectations and acknowledged that he made many unforced errors (a total of 38), the category of errors he had most wanted to avoid.

In his theory of ironic processes of mental control (hereafter, Wegner's theory), Wegner (Citation1994, Citation1997a, Citation2009) explains that Djokovic's wish to prevent such unwanted errors often, ironically, produces unintended effects—also known as ironic effects, later called ironic errors (Wegner, Citation1994; Wegner et al., Citation1998). According to Wegner, the more the attempt is to reduce pressure or avoid negative and intrusive thoughts while under high-pressure settings, the greater the likelihood of ironic effects. This incidence is viewed as the core assumption of Wegner's theory. Maintaining a desirable mental state (attentional control) involves the coexistence of two cognitive processes: the intentional operating process (hereafter, ‘the operator’) and an ironic monitoring process (hereafter, ‘the monitor’).

Dual-process system

The operator is characterized as conscious, effortful, slow, responsive to verbal instruction, and interruptible by competing resources such as perceived pressure, intrusive thoughts, anxiety, cognitive load, distractions, and others. It is responsible for maintaining the desired goal-related outcomes. As a result, it requires considerable cognitive resources. In contrast, the monitor is nonconscious, effortless, quick, unresponsive to verbal instruction, and uninterruptible by competing resources (Frankish, Citation2010; Wegner, Citation1994). Consequently, it does not depend on the availability of cognitive resources. It does, however, control the competing resources that lead to the operator's failure, such as goal-irrelevant outcomes (Wegner, Citation1994). Depending on the operator's and monitor's activities, mental control can either be strengthened, resulting in the desired goal-related outcomes, or undermined, thus increasing the likelihood of ironic effects (Wegner, Citation1994).

Mental control mechanism

Usually, mental control is successful when sufficient cognitive resources are available to achieve goal-related outcomes. However, the efficiency of cognitive resources is significantly depleted in some way, namely by competing resources. Consequently, the operator's capacity to simultaneously counter unwanted thoughts and search for desired thoughts is restricted. Meanwhile, the monitor becomes more salient, making the operator particularly susceptible to the contents of unwanted thoughts. Is it not paradoxical that the monitor, which essentially keeps the undesirable thoughts at bay, brings those very thoughts into consciousness? As a result, the operator's hypersensitivity to unwanted thoughts not only weakens the mental control, but also increases the likelihood that the to-be-avoided thoughts will emerge—a phenomenon known as ironic effect (Wegner, Citation1994; for details of an explanation on the mental control mechanism, we refer to Janelle, Citation1999; Wegner, Citation1994). Therefore, the effective interplay of the operator and monitor, as well as the availability of cognitive resources, are the two most important differentiating variables between the intentional mental control and the likelihood of ironic effects (Wegner, Citation1994).

Another crucial component of Wegner's theory is the use of avoidant instructions, which include directives like ‘try not to think of the white bear’ (Wegner et al., Citation1987). The likelihood of ironic effects when given avoidant instructions have been researched in various disciplines of psychology, most notably using Wegner et al. (Citation1987) ‘white bear’ thought suppression paradigm (for the meta-analysis, see Wang et al., Citation2020). Avoidant instructions have real-world applications in coaching and athletic performance, as related to Wegner's theory. Continuing with the preceding example of Djokovic, who intentionally focused specifically on his self-statement, ‘don't screw this up by hitting the second serve into the net,’ and then did just that—over and again, committing many unwanted errors.

Furthermore, when coaches express negative behaviors with negative remarks, frustration, or distress during high-performance events, athletes feel more tension and worry, draining their cognitive resources (Williams et al., Citation2003). This makes athletes more prone to engage in unwanted thoughts, including talking negatively to themselves (cf. Hardy et al., Citation2009; Zourbanos et al., Citation2006, Citation2007), resulting in a significant increase in errors (Moll & Davies, Citation2021). Attempts by sportsmen like Djokovic to avoid these unwanted thoughts and feelings during high-stakes competitions often backfire, making the operator less effective, the monitor more prominent while simultaneously reminding the athletes of the very thoughts and feelings they are trying to avoid. That is why Djokovic made multiple unforced errors, which he had intended to avoid and why Wegner calls them ironic errors (Citation1994). Wegner argues that athletes’ ironic errors in response to avoidant instructions may be the result of control attempts while cognitively taxed and subsequently under-resourced, rather than poor motor skills (Citation1994).

Wegner and colleagues (Citation1998) conducted the first investigation on the links between mental control and performance when given avoidant instructions under pressure conditions. Since then, Wegner's theory has become a subject of research in the field of sports psychology, albeit slowly. One potential reason for the slow adoption of Wegner's theory is the existence of some professional reservations about its significance to the field due to the difficulties inherent in testing the theory empirically, especially in elite athletes (Hall et al., Citation1999; Janelle, Citation1999). Another issue is whether the theory provides insightful information to coaches, researchers, and sport psychologists (Hall et al., Citation1999). Concurrently, concern has been expressed about the lack of a comprehensive investigation into the precise nature of performance breakdown, which highlights the pressure and performance relationship (Janelle, Citation2002). In the absence of scientific literature that systematically evaluates and summarizes the current knowledge of Wegner's theory in the sports domain, these questions still remain.

Empirical studies on the ironic effects of motor performance have not been evaluated systematically, apart from one Japanese paper (Tanaka & Karakida, Citation2019). Indeed, systematic reviews are widely recognized as the most effective tool in sports psychology for critically assessing the quality of evidence, gaining an understanding of current knowledge, and providing practical recommendations for real-world applications (Ely et al., Citation2021; Tod, Citation2019). Given the growing research interest in Wegner's theory and its applications in coaching and sport psychology, a systematic review of the existing evidence on the ironic effects of motor performance is both timely and important.

Therefore, this paper aimed to review the quality of published primary research studies that examine the ironic effects of motor task performance when given avoidant instructions under conditions of pressure, such as cognitive load. The review specifically sought to answer the following research questions: (1) What kinds of samples, motor tasks, manipulation techniques, and measurements are used to test ironic errorsFootnote1? (2) How effective are manipulation techniques and measurements? (3) What are the included studies’ methodological quality? While seeking to address the research questions, this systematic review helps athletes and coaches become aware of the incidence of ironic errors, and sport psychologists and researchers advance Wegner's theory in sports performance, and beyond. Furthermore, it also highlights research gaps and future directions and offers athletes and professionals evidence-based recommendations to reduce the incidence of ironic errors.

Method

The review adhered to, but was not limited to, the following guidelines: (1) the PRISMA 2020 statement, an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews (Page et al., Citation2021); and (2) guidance on conducting and reporting systemic reviews (Campbell et al., Citation2020; Popay et al., Citation2006; Siddaway et al., Citation2019). The review includes supplementary files (labeled as Table S1, Table S2, etc.) for methodological specifics (Gunnell et al., Citation2020) and a systematic mapping (Haddaway et al., Citation2016). The review was registered prospectively in PROSPERO with the registration number CRD42021266655.

Literature search strategy

An electronic literature search was undertaken across 10 databases: APA PsycInfo, CINAHL, Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycArticles, PubMed, SPORTDiscus with Full-Text, Web of Science (Core Collection), and Google Scholar. We ran the comprehensive search twice. The first search was conducted in July 2021. In each distinct database, the search was conducted by using the following Boolean search string: [(‘ironic process*’ OR ‘mental control’) AND (‘ironic effect*’ OR ‘ironic error*’ OR ‘avoidant* instructi*’ OR ‘motor* task*’ OR ‘pressure* perform*’)]. An updated search, using the same search string, was conducted in January 2022. The first author carried out all searches, and critical discussions were conducted between the first and second authors throughout the search process. The titles and abstracts retrieved from the databases were imported into Rayyan QCRI web-based program (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016; see Table S1 for a complete search strategy).

Selection criteria

Before screening the literature search, the first author formulated the preliminary eligibility criteria. After critical appraisal and feedback from the second author, the criteria were revised. This review looked at studies that (a) included novice, trained, highly trained, and elite participants; (b) attempted to induce cognitive load when giving avoidant instructions experimentally and quasi-experimentally in motor task performanceFootnote2; (c) compared how ironic performance changed between low-cognitive load and high-cognitive load conditions, or between baseline (neutral) and experimental conditions; and (d) reported primary outcomes; and (e) were peer-reviewed and published in English between 1998 (the first available empirical data in sports performance) and January 1, 2022 (see Table S2 for additional details of eligibility criteria).

Screening procedure

The retrieved articles were screened in three stages: In the first stage, the first and second authors thoroughly and independently compared all titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria. At this stage, we resolved minimal doubts in determining whether to retain or exclude one ‘borderline case’, which was included in the full-text review to ensure improved specificity (Siddaway et al., Citation2019). We then obtained the full-text manuscripts of all relevant articles addressing the experimental manipulations of cognitive load when given avoidant instructions in sports performance. In the second stage, the first author conducted a hand-search accompanied by website and online resources (Stansfield et al., Citation2016) to find relevant articles that might have been omitted from the database search. We used here two consecutive methods to refine the results of hand-searching: first, we searched reference lists of all relevant studies that had been identified; second, we performed the so-called citation tracking from the identified studies using Google Scholar, and we tracked all ‘related’ or ‘similar’ articles until no more relevant articles were identified. The results of each of the two methods were then assessed for eligibility against the inclusion criteria and full-text review. In the third stage, the same authors independently reviewed the remaining full-text studies for eligibility. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by reaching consensus (for further details on the screening procedure, see Table S2).

Data extraction

Data extraction was developed after retrieving all full-text studies. The extracted data from full-text studies was then systematized. The first author performed the initial data extraction, and the second author double-checked it for correctness, clarity, and completeness. The following data were extracted from the included studies: reference, study design, motor task, sample characteristics, setting, experimental manipulation procedures, outcome measures, cognitive load measurements, and main outcomes.

Synthesis approach

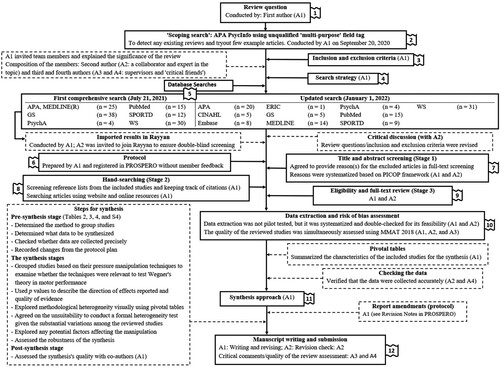

Following the completion of data extraction, pivotal tables were constructed to summarize the characteristics of the included studies and prepare the main findings for synthesis (see Tables 2, 3, 4 and S4). According to McKenzie et al. (Citation2019), we grouped studies into two categories based on the techniques that their authors employed to manipulate cognitive load: anxiety-based and dual-task-based. To describe the direction of the manipulation effects reported, we used the statistical approach—combining the reported levels of p values for the outcome measures from each trial of the reviewed studies. This choice was made because almost all experimental trials in the reviewed studies investigated a similar question: whether cognitive load when given avoidant instructions induced the likelihood of ironic errors. Although many studies attempted to address the same question, they were considerably diverse in the samples, motor tasks, study designs, manipulation techniques, outcome measures, and outcome reporting. Consequently, we decided to synthesize the reviewed studies using a narrative synthesis approach (Popay et al., Citation2006) without meta-analysis (Campbell et al., Citation2020) given its potential to address the review questions (Thomas et al., Citation2012) and ‘summarize and describe the findings from the included studies using verbatim’ (Popay et al., Citation2006, p. 5). Furthermore, the narrative approaches to synthesis have been used in quantitative systematic review studies, including experimental and quasi-experimental studies when a meta-analysis is unfeasible (Snilstveit et al., Citation2012). The efficacy of the categorized manipulation techniques was then assessed to examine whether the techniques applied were appropriate for the objective in question, as well as to inspect any potential factors that influenced the results across the reviewed studies (Popay et al., Citation2006). We then critically reflected on the evidence's methodological and conceptual flaws. Finally, all authors virtually met to discuss the synthesis's strengths and limitations. An overview of the review process is presented in .

Quality assessment

The quality of the reviewed studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, version 18 (MMAT 2018; Hong et al., Citation2018). The MMAT provides detailed information about the quality of the reviewed studies, and it has been used previously for systematic reviews in sports and exercise psychology (Gayman et al., Citation2017; Gledhill et al., Citation2018; Goddard et al., Citation2021; Gröpel & Mesagno, Citation2019). The MMAT 2018 includes 25 methodological criteria for the following study designs: (1) qualitative, (2) quantitative—randomized controlled studies (RCT), (3) quantitative—non-randomized controlled studies, (4) quantitative—descriptive studies, and (5) mixed-methods studies. Using the MMAT 2018 guidelines, the reviewed studies were categorized as experimental and quasi-experimental. The rating of each methodological criterion was based on a nominal scale (yes, no, can't tell). The first author appraised the reviewed studies, while the second and third authors assessed all the included studies independently. Disagreements were resolved through critical discussion between the three authors, or arbitration with the fourth author if needed. summarizes the MMAT quality assessment (for details, see Table S3).

Table 1. Summary of study quality assessment using mixed methods appraisal tool1.

Results

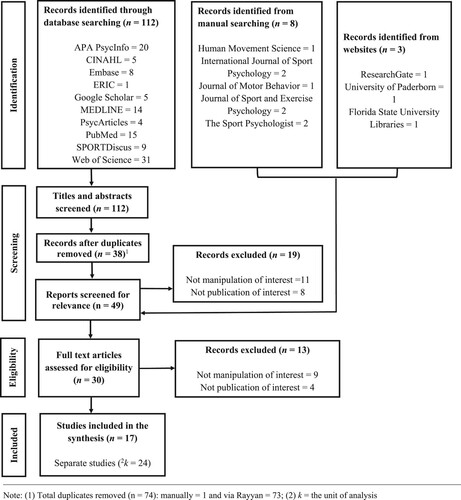

The results of the screening procedure are shown in . The comprehensive search yielded 17 articles covering 24 separate studies that met the inclusion criteria. During the screening stage, 19 articles were excluded for failing to meet manipulation and publication eligibility criteria. In the eligibility stage, an additional 13 studies were excluded (for additional details on why these articles were excluded, see Table S2). A summary of all sample and study characteristics, and manipulations procedures are presented in .

Table 2. Summary of sample characteristics, study characteristics, and experimental manipulations procedures of the included studies.

Sample characteristics

There were 1152 participants across the 17 studies. Of the overall participants, 701 (61%) were male, and 420 (36%) were female. K = 1 excluded 31 (3%) participants for not meeting their inclusion criteria (Liu et al., Citation2015). The mean age of the participants across all studies was 21.78 ± 3.07, although this descriptive analysis excluded two studies by Wegner et al. (Citation1998), which did not report participant ages. K = 1 reported participants younger than 18 (Gorgulu & Gokcek, Citation2021). In terms of gender, k = 7 (29%) included only male participants, k = 2 (8%) included only female participants (Dugdale & Eklund, Citation2003; Gorgulu & Gokcek, Citation2021), and the remaining k = 15 (63%) included participants of mixed genders. For participants’ skill levels, k = 12 (50%) included novices (n = 683), k = 3 (13%) included trained participants with limited skills to perform the motor tasks (n = 155; Barlow et al., Citation2016, Study 1; de la Peña et al., Citation2008, Study 1; Woodman et al., Citation2015, Study 1), k = 8 (33%) included highly trained participants with proficient skills competing at national level (n = 226), and k = 1 (4%) included elite athletes with highly proficient skills competing at international level (n = 57; Gorgulu, Citation2019a). In addition, k = 2 included neurotic participants (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2; Table S7 provides further details of sample characteristics).

Study characteristics

Types of motor tasks

Thirteen motor tasksFootnote3 were represented across the reviewed studies. K = 16 used perceptual-motor tasks (football penalty shooting [k = 4], golf-putting [k = 3], dart throwing [k = 3], hockey penalty shooting [k = 1], air-pistol shooting [k = 1], baseball pitching [k = 1], tennis serving [k = 1], volleyball serving [k = 1], and basketball free-throwing [k = 1]). K = 3 used stability motor tasks (upper limb motion steadiness [k = 1], balance [k = 1], and pendulum holding [k = 1]). K = 5 used reactive-motor tasks.

Research design

The reviewed studies employed quantitative approaches, including experimental within- and between-subject designs. K = 5 (21%) were experimental and included 350 participants, with an average sample size of 70.00 ± 34.08. K = 19 (79%) were quasi-experimental and included 903 participants, with an average sample size of 42.21 ± 18.78.

Risk of bias assessment

In accordance with Fleiss (Citation1971), Fleiss’ kappa (κ) was calculated to examine the interrater reliability (IRR) between the three authors for the MMAT 2018 using SPSS software, version 28.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The IRR result revealed nearly a perfect level of agreement (κ = .83).

Cognitive load manipulation techniques

The most widely used cognitive load manipulation technique was anxiety-based (k = 16, 67%), in which researchers artificially induced cognitive load, such as anxiety by using a combination of financial incentives (k = 14) and videotaping (k = 1) along with anxiety-inducing instructions, such as ego-threatening instructions (k = 14), and social evaluation instructions (k = 11). Also, two studies created single anxiety-inducing stressors, such as performing at height (Oudejans et al., Citation2013), and financial incentives (Woodman & Davis, Citation2008). The second manipulation technique identified was dual-task-based (k = 8; 33%), in which researchers taxed participants’ attentional resources through concurrent tasks. Cognitive load was induced by a combination of time constraints and visually distracting stimuli (k = 3), rehearsing a digit-number and visual distracting object (k = 1; Wegner et al., Citation1998, Study 1), rehearsing a digit-sequence aloud, visual, and auditory distracting object, and incentive for self-presentation (k = 1; de la Peña et al., Citation2008, Study 1), rehearsing cue aloud, time pressure, and incentive (k = 1; Liu et al., Citation2015), and counting a digit-number backward mentally and holding a load in an outstretched nondominant hand (k = 1; Wegner et al., Citation1998, Study 2). Only one study used a single form of cognitive load, such as counting a digit backward mentally (k = 1; Dugdale & Eklund, Citation2003). Depending on the specifics of their manipulation techniques, the reviewed studies presented their experimental conditions differently. In quasi-experimental studies, for example, cognitive load conditions were either presented in a counterbalanced (k = 7) or fixed order (k = 8; for additional information about the manipulations characteristics, see Table S4).

In terms of instructional manipulations, k = 24 used avoidant instructions with negative priming phrases (‘please be particularly careful not to putt the ball short’) consisting of both short (composed of 8 words) and long words (composed of 197 words). Five out of twenty-four studies used action-oriented (‘don't stop the ball’) and inaction-oriented avoidant goals (‘don't let the ball go’; Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Studies 1–5). In addition, k = 3 used directional avoidant instructions (de la Peña et al., Citation2008, Study 1; Wegner et al., Citation1998, Study 1; Woodman & Davis, Citation2008), k = 3 incorporated positively constructed instructions (Bakker et al., Citation2006, Study 2; Binsch et al., Citation2010a, Citation2010b), and k = 3 used positive self-focus cues (Dugdale & Eklund, Citation2003; Liu et al., Citation2015; Wegner et al., Citation1998, Study 2). Most of the reviewed studies formulated standardized instructional scripts. The instructional manipulations are presented in a mixed manner. Most studies presented their instructional manipulations to participants verbally (k = 23), while k = 1 presented graphic and verbal instructions (Gray et al., Citation2017). The frequency with which the instructions were presented varied significantly among the reviewed studies (for further information about characteristics of instructions, see Tables S5 and S6).

Most studies conducted their experiments in a laboratory setting (k = 17, 71%). The remainder conducted their experiments in the field (k = 7, 29%), which included standard indoor sporting facilities. However, none of the studies were conducted during actual games or in competitive settings.

Most of the studies (k = 22; 92%) investigated how ironic errors occur when given avoidant instructions under conditions of cognitive load. Although several studies aimed to examine the ironic errors mechanism, the purposes of their investigations were varied. Three studies, for example, investigated whether personality traits moderate the likelihood of ironic errors (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2; Woodman & Davis, Citation2008); three studies looked into the precise ironic performance breakdown within the ironic zone, focusing on hits that land within the ironic error zones but are just slightly off the target zone (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Study 2; Gorgulu, Citation2019a; Woodman et al., Citation2015, Study 2); one study investigated kinematics (Gray et al., Citation2017); one study investigated performance decrement and choking (Oudejans et al., Citation2013); three studies examined the likelihood of ironic errors in externally timed reactive-motor tasks (Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Studies 1, 2, and 4); three studies assessed how gaze behavior influences the incidence of ironic errors (Bakker et al., Citation2006, Study 2; Binsch et al., Citation2010a, Citation2010b); and one study examined the impact of gender differences on the likelihood of ironic errors (Liu et al., Citation2015). Few studies (k = 2; 8%) have investigated whether task instructions moderate the likelihood of ironic errors (Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Studies 3 and 5).

Cognitive load measurement

Within the anxiety-based, the most common subjective anxiety measure was the Mental Readiness Form-3 (MRF-3; Krane, Citation1994), which was used in 14 studies. Additionally, Gorgulu (Citation2019a) incorporated the Rating Scale of Mental Effort (Zijlstra, Citation1993), and Barlow et al. (Citation2016, Studies 1–2) used the International Personality Item Pool (Goldberg, Citation1999). The most reported objective measures of anxiety were heart rate and heart rate variability, in which researchers used heart rate monitors (k = 7) and electrocardiography (k = 5). Moreover, Gorgulu et al. (Citation2019) used electromyography to measure muscle activity linked to anxiety (Studies 1–5).

Of the dual-task-based, k = 3 included direct measures of visual attention using eye-tracking devices (Bakker et al., Citation2006, Study 2; Binsch et al., Citation2010a, Citation2010b). Furthermore, Liu et al. (Citation2015) reported cognitive load measurement using skin conductance level and Likert-scale surveys. provides summaries of cognitive load measurements.

Performance measures

Within anxiety-based (k = 16), k = 10 measured performances in clearly defined zones labeled as target, ironic, and non-ironic in different perceptual-motor tasks. These studies recorded ironic errors by counting the number of motor actions that landed in the ironic zones (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2; Gorgulu, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c; Gorgulu & Gokcek, Citation2021; Gray et al., Citation2017; Oudejans et al., Citation2013; Woodman et al., Citation2015, Studies 1–2). K = 5 recorded participants’ responses to ironic stimuli in reactive-motor tasks (Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Studies 1–5). K = 1 measured ironic error (overshooting) by recording the ball's distance in centimeters traveled past the target (Woodman & Davis, Citation2008). The fifteen studies also included the following performance measures: (1) thirteen studies recorded the non-ironic errors (except Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Study 1; Oudejans et al., Citation2013); (2) three studies calculated the arc length from the closest non-ironic error zone and the radial distance from the target zone to determine the precision of ironic errors (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Study 2; Gorgulu, Citation2019a; Woodman et al., Citation2015, Study 2); and (3) one study measured ironic movement errors by calculating the mean standard deviations of distinctly defined pitching kinematics (Gray et al., Citation2017).

Within the dual-task-based (k = 8), k = 3 measured ironic errors based on where participants kicked the ball and fixed their gaze in relation to the experimental instruction conditions in a simulated penalty settings (Bakker et al., Citation2006, Study 2; Binsch et al., Citation2010a, Citation2010b). K = 3 recorded ironic errors based on participants’ body instability when given avoidant instructions under cognitive load (Dugdale & Eklund, Citation2003; Liu et al., Citation2015), as well as under physical load conditions (Wegner et al., Citation1998, Study 2). K = 2 measured ironic errors (i.e., overshooting or undershooting) by recording the difference between the experimental and baseline or control putts in centimeters traveled behind or in front of the target spot (de la Peña et al., Citation2008, Study 1; Wegner et al., Citation1998, Study 1).

Manipulation outcomes

This section discusses the reported primary outcomes of the manipulations in the following order: anxiety-based, followed by dual-task-based. This grouping is based on the most frequently used manipulation techniques in the reviewed studies. Under each manipulation technique, subheadings are used to divide the summary of the findings into manageable sections. summarizes the key findings of the manipulations.

Table 3. Summary of outcome measures and primary outcomes reporting under cognitive load manipulation when given avoidant instructions.

Anxiety-based manipulation techniques

Of the reported anxiety-based manipulation techniques (k = 16), ten studies involved target, ironic, non-ironic-oriented motor tasks; five studies included action- and inaction-oriented goals in reactive-motor tasks; and one study included a direction outcome-based motor task.

Zone (target, ironic and non-ironic)-oriented motor tasks

Nine out of ten studies reported that participants performed fewer motor actions in the target zones and more motor actions in the to-be-avoided (ironic) zones when given avoidant instructions under high-anxiety compared to low-anxiety conditions (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2; Gorgulu, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c; Gray et al., Citation2017; Oudejans et al., Citation2013; Woodman et al., Citation2015, Studies 1–2). Notably, Oudejans et al. (Citation2013) found that giving avoidant instruction in high-anxiety conditions not only caused participants to perform ironically in the to-be-avoided areas but also had detrimental effects on performance. However, Gorgulu and Gokcek (Citation2021) reported that highly trained volleyball players performed similarly in the target and ironic error zones when given avoidant instructions across anxiety conditions. Furthermore, twelve of the fifteen studies reported that performances in relation to the non-ironic zones were unaffected when given avoidant instructions under high- and low-anxiety conditions; however, two studies did not measure the non-ironic performances (Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Study 1; Oudejans et al., Citation2013). Gorgulu and Gokcek (Citation2021), on the other hand, found significant performance differences in the non-ironic error zone when given avoidant instructions under high-anxiety compared to low-anxiety conditions.

Regarding the precision of ironic errors, two studies reported that when given avoidant instructions under high-anxiety compared to low-anxiety conditions, novice participants’ performances in the ironic error zones were significantly farther away from the target zones and significantly closer to the specifically to-be-avoided zones (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Study 2; Woodman et al., Citation2015, Study 2). Specifically, Barlow and colleagues (Citation2016) found that when anxious, neurotic participants, who feel often stress and anxiety, performed more precisely in the ironic error zone than their non-neurotic counterparts (Study 2), despite showing a greater likelihood of ironic errors (Studies 1–2). Conversely, Gorgulu (Citation2019a) found that elite participants’ precision of ironic performances was unaffected by anxiety conditions, regardless of when they made ironic errors.

It was found in one of the fifteen studies by Gray et al. (Citation2017) that ironic groups’ performances were unaccompanied by changes in movement kinematics when given avoidant instructions under high-anxiety compared to two low-anxiety conditions. This finding indicated that despite being analyzed at the group level, ironic groups broke their performances precisely when anxious.

Action- and inaction-oriented goals

Three studies found that when participants were given action-oriented avoidant goals (i.e., ‘not to stop the ironic color balls’), they responded with fewer target color balls and more ironic color balls under high-anxiety compared to low-anxiety conditions (Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Studies 1, 2, and 4). Two of the five studies focused on inaction-oriented instructional interventions to reduce ironic errors (Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Studies 3 and 5). They found that participants showed stable and satisfactory performance when the avoidant goals were tailored to ‘not let the ironic color balls go’ across anxiety conditions. Except for Study 1, which did not incorporate the non-ironic error measures, all four studies found that action- and inaction-oriented goals had no effect on participants’ reactions to non-ironic error stimuli across anxiety conditions.

Direction outcome-based motor task

Woodman and Davis (Citation2008) investigated how anxiety and specific anxiety coping styles influence the likelihood of ironic errors, particularly in repressors, who reported low cognitive anxiety but had high heart rates under high-anxiety conditions. They found that when instructed ‘don't overshoot’, novice repressor golfers significantly put the ball further under high-anxiety compared to low-anxiety conditions.

Dual-task-based techniques

Of the reported dual-task-based manipulation techniques (k = 8), four included memory and arithmetic tasks, three studies used visual attention tasks, and one implemented a cue rehearsal task.

Memory and arithmetic tasks

Wegner et al. (Citation1998) reported that novice golfers significantly put the ball longer when given ‘don't overshoot’ instructions under ‘load’ compared to without ‘load’ conditions (Study 1). However, de la Peña et al. (Citation2008) reported that trained golfers significantly put the ball in the direction opposite to the ‘don't put the ball short’ instructions under ‘load’ compared to ‘no-load’ conditions (Study 1). This is because, as predicted by de la Peñ a and colleagues’ implicit overcompensation hypothesisFootnote4, instructions like ‘don't putt it short’ may unintentionally lead golfers to putt the ball longer—a phenomenon known as overcompensating errors. Additionally, Dugdale and Eklund (Citation2003) found that highly trained dancers committed more movement errors and showed less stability when given ‘don't wobble’ instructions under a high-cognitive load (i.e., counting a digit-number backward mentally) compared to when given ‘hold steady’ instructions under the same high-cognitive load condition. Wegner and colleagues’ (Citation1998) study constituted the only concurrent task manipulation involving physical load—holding a load in one's nondominant hand (Study 2). They found that participants demonstrated an enhanced movement towards the to-be-avoided direction when given ‘don't shake’ instructions under both cognitive (i.e., counting a digit-number backward mentally) and physical ‘load’ compared to the ‘no-load’ conditions.

Visual attention tasks

Under time pressure and visual distractions, Bakker et al. (Citation2006) found that highly trained football players’ performance and their initial gaze-fixations were significantly more directed toward the to-be-avoided (‘not-keeper’, ‘not-next to the goal’) and positive (‘hit the open space’) instructions than the neutral instruction condition (Study 2). Furthermore, Binsch et al. (Citation2010a) found that ironic players kicked their penalties closer to the to-be-avoided target (i.e., keeper) under both ‘not-keeper’ and ‘pass-keeper’ instructions to a similar degree than under the neutral instruction condition. Notably, ironic players fixated significantly longer on the keeper when given ‘not-keeper’ instructions than both ‘pass-keeper’ and neutral instruction conditions, increasing the likelihood of ironic errors. Binsch et al. (Citation2010b) found that players (44%) who demonstrated ironic errors had shorter final fixations on the open goal space under ‘not-keeper’ instructions than under ‘open-space’ and neutral instruction conditions.

Cue rehearsal task

A study conducted by Liu et al. (Citation2015) reported that the low-cognitive load (no-time constraint) and ‘don't shake’ rehearsal groups performed worse in the test block than the baseline block, committing more unsteady movement errors. Particularly, male participants’ performance deteriorated in the test block compared to the baseline block, but female participants’ performance remained similar across both blocks.

Theoretical perspectives of the reviewed studies

While this review uncovered the underlying nature of the ironic processes-performance relationship when given avoidant instructions under conditions of cognitive load, the majority of the reviewed studies’ findings (k = 22; 92%) align with Wegner's theory. Two studies (k = 2; 8%) provided inconclusive findings: de la Peña et al. (Citation2008, Study 1) supported the implicit overcompensation hypothesis, whereas Gorgulu and Gokcek (Citation2021) did not support Wegner's theory but did provide significant insight into Woodman et al.'s (Citation2015) assumption. That is, distinguishing between ironic and non-ironic performances is critical when testing ironic errors in motor performance.

Furthermore, the review highlights that few studies tailored their examinations on the likelihood of ironic errors toward their predictions, and hence their measurements. For instance, ironic errors were partially mediated by gaze fixation (Binsch et al., Citation2010a), and moderated by specific dispositions, such as neuroticismFootnote5 and anxiety coping styles (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2; Woodman & Davis, Citation2008). Exceptionally, Gray and colleagues’ (Citation2017) kinematics findings substantiated Wegner's assumption of how precisely participants’ specific movement patterns broke down when anxious. Two studies, in particular (Liu et al., Citation2015; Oudejans et al., Citation2013), suggested that ironic errors can be a contributing factor to choking under pressure. However, Liu et al. partially supported Wegner's theory under low-cognitive load but not under high-cognitive load conditions.

In the studies that incorporated both avoidant and positive instructions, Bakker et al. (Citation2006, Study 2) and Binsch et al. (Citation2010a) suggested that ironic errors can also occur when given positive instructions—including words related to the forbidden target. Furthermore, Gorgulu et al.'s (Citation2019) interventional studies support theoretically driven assumptions. Their studies (Studies 3 and 5), for example, reveal that ironic errors were less likely when the operator had an advantage over the monitor when given inaction-oriented goals, which are easy and energy-saving to process.

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated current evidence on the incidence of ironic errors of motor performance. A considerable amount of literature has investigated the likelihood of ironic errors in motor actions, despite some scholars have expressed doubts about Wegner's theory (Hall et al., Citation1999; Janelle, Citation1999). We reviewed twenty-four separate studies that investigated the likelihood of ironic errors using thirteen motor tasks. Of the twenty-four studies, more than half (k = 15) were published between 2015 and 2021. The most common cognitive load manipulation techniques were anxiety-based (k = 16; 67%) and dual-task-based (k = 8; 33%). Furthermore, cognitive load manipulation techniques were integrated with avoidant instructions and implemented experimentally (k = 5) and quasi-experimentally (k = 19) using within- and between-subject designs. Despite two studies’ inconclusive findings, most of the reviewed studies support Wegner's theory. However, given the significant heterogeneity in the samples, motor tasks, designs, methods, manipulation, and measurement techniques used, comparing findings between and within the included studies is problematic. As a result, caution is necessary when interpreting the evidence. In the following sections, we will address these concerns as well as the efficacy of the manipulation and measurement techniques.

Sample and study characteristics

While analyzing study characteristics, we identified that novice volunteer participants made up exactly half of the participants in the reviewed studies, whereas some were highly trained participants with small sample sizes. Although empirical evidence on elite performers is limited in relation to Wegner's theory (see Gorgulu, Citation2019a), there is also a general lack of investigations on the likelihood of ironic errors among national, international, and professional athletes. As predicted, it is not surprising that the effect of cognitive load on ironic errors is more prominent for novice participants when given avoidant instructions (Wegner et al., Citation1998). However, Gorgulu (Citation2019a) showed that elite participants are not immune to ironic errors when given avoidant instructions under high-anxiety conditions.

Furthermore, seventeen studies conducted their experimental manipulations in lab settings. While lab-based experimentation is critical, the generalizability of research findings in highly structured and controlled scenarios compared to ‘real-worldFootnote6’ and ‘ecologically valid (see endnote 6)’ professional sports competitions is somewhat problematic. To address the main question of this review, namely, how cognitive loads induce ironic errors when given avoidant instructions, the reviewed studies used experimental and quasi-experimental designs, albeit disproportionately. While assessing the quality of the reviewed studies using MMAT (Hong et al., Citation2018), we identified two major issues for quasi-experimental studies: failure to address potential confounding factors and selection bias. Therefore, caution should be used when interpreting the findings associated with small sample sizes, limited data on the likelihood of ironic errors among highly trained and elite participants, and questionable experimental methodologies.

The effectiveness of cognitive load manipulation and measurement approaches

When analyzing cognitive load manipulation techniques, we noted three key issues: first, twenty studies in the review induced cognitive loads with ecologically valid competitive stressorsFootnote7 that mimicked pressure in real-world scenarios. Conversely, four dual-task-based studies induced cognitive loads to tax participants’ working memory (rehearsing and counting a digit-number). However, researchers have expressed concerns about using memory and arithmetic manipulation techniques; specifically, their viability in sports performance contexts is limited in terms of inducing competitive anxiety (Woodman et al., Citation2015; Woodman & Davis, Citation2008). An exception to this concern is the study by Wegner et al. (Citation1998), which incorporated the physical load (Study 2).

Second, it is worth noting how the reviewed studies measured cognitive load. Anxiety-based studies were successful in monitoring participants’ level of anxiety by integrating direct (e.g., heart rate, heart rate variability, and muscle activity) and indirect (e.g., MRF-3) measurements of anxiety. Furthermore, Gorgulu (Citation2019a) used a rating scale of mental effort to track how much resources elite athletes used to deal with the anxiety manipulations, despite the nonsignificant main or interaction effects across anxiety conditions (see ). Evidence from mainstream psychology research suggests that measuring mental effort coupled with task performance represents the most reliable estimator of cognitive load (Paas et al., Citation1994). Of the dual-task-based studies, four studies monitored the effectiveness of the outcomes of cognitive load manipulations, such as visual attention using eye-tracking devices (Bakker et al., Citation2006, Study 2; Binsch et al., Citation2010a, Citation2010b) and using post-test pressure rating (Liu et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, three studies that manipulated cognitive load through memory and arithmetic tasks were unsuccessful in reporting participants’ rehearsal accuracy of a digit-number. Furthermore, they failed to explain whether the rehearsal methods are linked to measuring participants’ mental effort or testing the strengths of cognitive load manipulations. The study by Dugdale and Eklund (Citation2003) is an exception in that they noted each participant's rehearsal report and provided verbal feedback on its accuracy. Although de la Peña et al. (Citation2008) monitored the memory manipulations by having participants rehearse the digit-sequence aloud, they failed to monitor the effectiveness of their other ‘load’ manipulations (Study 1). On the other hand, Wegner et al. (Citation1998) did not disclose how they controlled participants’ physical exhaustion when holding a common brick with their nondominant hand, as well as their mental effort when counting a digit-number backward mentally (Study 2). Consequently, inducing either a cognitive or physical load without any ‘load’ manipulation check may raise questions about its effectiveness.

Table 4. Summary of cognitive load measurements and outcome reporting (Mean, SD, 1p values, effect size2).

Last, while analyzing the instructional manipulations, we noted that all studies in the review used avoidant instructions as pressure-inducing elements in combination with cognitive load-inducing stressors, such as financial incentives, rewards, time pressure, videotaping, and performing at height. The most frequently used avoidant instructions that aim to manipulate anxiety using multiple ecologically valid stressors are ego-threatening and social evaluative instructions. Instructing participants that they will be penalized for every action they perform in the forbidden zones or in response to the to-be-avoided stimuli as well as informing them that their videotaped performance or score will be evaluated by a coach are examples of ego-threatening and social evaluative instructions. Two studies, for instance, found that the effects of ego-threatening and social evaluative instructions, and financial incentives on ironic errors were moderated by personality traits such as neuroticism and repression (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2; Woodman & Davis, Citation2008). In contrast, Gorgulu and Gokcek (Citation2021) found that participants did not show ironic errors using award, ego-threatening, and social evaluative instructions. This implies that using multiple ecologically valid stressors to induce cognitive load such as anxiety may have different effects on anxiety responses depending on the individual and the context.

On the other hand, thirteen studies failed to report whether participants followed the given instructions. Twenty-three studies, for example, did not monitor participants’ responses to instructional manipulations (see Table S5). One study that did offer such an example is that of Liu et al. (Citation2015), in which they assessed participants’ attentional focus on the given instructions using a post-experimental survey that was reported to be effective.

Effectiveness of performance measures

This review highlights that measuring motor performances in a controlled environment raises concerns over ecological validity while testing Wegner's theory. For example, measuring a single trial's performance, like the single putts used by Wegner et al. (Citation1998, Study 1) and Woodman and Davis (Citation2008), appears ‘ecologically valid’. However, most studies show that ironic errors are also likely to occur after repeated participant performances across trial blocks. Another concern related to ecological validity when measuring performance is giving opportunities to re-attempt the task (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2) and the specificity of the tasks, such as the use of virtual goalkeepers and goals (Bakker et al., Citation2006, Study 2; Binsch et al., Citation2010a, Citation2010b), a virtual batter (Gray et al., Citation2017), wobble board tasks for dancers (Dugdale & Eklund, Citation2003), dart throwing at height (Oudejans et al., Citation2013), the absence of real goalkeepers (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Study 1; Woodman et al., Citation2015, Study 1), and absence of opponents in ball servings tasks (Gorgulu, Citation2019c; Gorgulu & Gokcek, Citation2021).

Furthermore, nine studies in the review measured participants’ performance using the ‘one-dimensional’ approach, such as asking participants to perform a desired action or not to perform an undesired action. For example, asking participants to stay stable is a desirable behavior in a balance performance, whereas asking them not to shake and if they shake, it is an undesirable behavior. Consequently, participants’ undesirable actions were conceptualized as ironic errors. However, it is unclear whether participants’ undesired behaviors are the result of ironic errors or simply poor performances under conditions of cognitive load when given avoidant instructions. In contrast, thirteen anxiety-based studies offered promising examples of measuring participants’ motor task performances using the ‘two-dimensional’ approach: the specific ironic errors and the generic non-ironic errors. Given everything discussed so far, the generalizability of the findings and the efficacy of the experimental manipulations in the reviewed studies are contentious.

Theoretical stance inconsistencies

This section discusses contradictory results and theoretical support positions. Gorgulu and Gokcek (Citation2021), for instance, did not support Wegner's theory since they found a generic serve error rather than a specific ironic serve error. The most striking finding from the data is that players performed effectively while being exposed to competitive stressors (see Tables 4 and S4). Two possible explanations exist for these findings: first, for the sake of winning the present, players might be conscious of the need to avoid serving into the ironic zone, which was allocated adjacent to the target zone. Furthermore, they recognized that the task is being performed in the absence of an opponent. Second, the players might not pay attention to the ego-threatening and social evaluative instructions during the trials. Consequently, they might not find the anxiety manipulations or task meaningful. Concerns like these could be addressed by looking at different behavioral measures, such as gaze-behavior, using manipulation checks to see how participants respond to instructions, and modifying instructional manipulations by adding more ecologically valid stressors that can increase their level of anxiety.

The paradox of testing Wegner's theory is shown by the results of the likelihood of ironic errors (Wegner et al., Citation1998, Study 1) and the likelihood of overcompensating errors (de la Peña et al., Citation2008, Study 1). This inconsistency might be the result of differences in approach at the conceptual level; for example, the implicit overcompensation hypothesis is not rooted in a theory; at the very least, its assumption is not based on a dual-process system, as Wegner's theory is. As such, its potential to explain ironic processes is questionable. Furthermore, Wegner's theory emphasizes the importance of cognitive load when given avoidant instructions, whereas the implicit overcompensation hypothesis emphasizes the impact of negative self-instruction on the efficiency of attentional resources, although de la Peña et al. did offer support for the implicit overcompensation hypothesis under four different ‘load’ conditions when given negative instructions. However, some of the ‘loads’ used by de la Peña and colleagues lack ecological validity in taxing participants’ attentional resources.

Methodological concerns in relation to the direction of the avoidant instructions might be another potential cause. Neither study, for example, attempted to simultaneously manipulate ‘don't overshoot’ and ‘don't undershoot’ instructions. As well, the study by Wegner et al. included novice golfers, whereas de la Peña et al. included trained golfers. Furthermore, de la Peña et al. found that a small percentage of golfers (37.5%) showed ironic errors, implying that both the likelihood of overcompensating and ironic errors might coexist when given avoidant instructions under ‘load’ conditions in the golf-putting tasks. Recently, a study that was not included in this review attempted to explain their co-occurrence using an attentional imbalance paradigm in golf-putting task performances (Liu et al., Citation2019). It is interesting to note whether the predisposition to overcompensating errors is exclusive to the golf sport or ubiquitous in the performance of other professional sports. However, questions remain unanswered at present, including the mechanism of the co-occurrence of ironic and overcompensating errors when given avoidant instructions under cognitive load, and whether the implicit overcompensation hypothesis and Wegner's theory may interact in the dual-process system.

Methodological critique

This review highlights some methodological concerns that stemmed from the experimental manipulations, measurements, and analyses. As an ecologically valid stressor, time constraints made it hard for participants to control their attention during visual attention tasks, which ironically diverted their gazes to the to-be-avoided locations (Bakker et al., Citation2006, Study 2; Binsch et al., Citation2010a; Binsch et al., Citation2010b). In these studies, however, time as a cognitive load was not retained as a factor and the findings were also analyzed at the group level. More importantly, time pressure is a significant feature of competitive sports (Janelle, Citation1999), which applies to penalty kickers who tend to kick the ball quickly under pressure conditions (Jordet, Citation2009). Similarly, Gorgulu et al. (Citation2019, Studies 1–5) did not include time in their analysis, even though time pressure is an integral part of reactive motor tasks, which may enhance ironic errors (Wegner, Citation1994).

Counterbalancing experimental conditions is fundamental to experimental research (Shaughnessy et al., Citation2000). As noted, quasi-experimental studies (k = 8) used fixed presentations of anxiety conditions to lessen the anxiety burden on novices. Despite the studies monitored the anxiety carryover effect in participants, this strategy has at least two major drawbacks, First, it may suggest that there is only a single linear link between cognitive load and ironic performance errors. It may also infer that investigating the phenomenon of ironic error in the realm of sports performance is straightforward.

Another point worth mentioning is the instructional manipulations. We noted that most studies used negative priming phrases while giving both short and long avoidant instructions. It is questionable, however, which of the two factors—the participants’ attempts to suppress the avoidant instructions or the negative priming phrases—contributed more to an increased likelihood of ironic errors (Woodman et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, from a practical standpoint, it is uncommon for professional athletes and coaches to make use of extensive instructions combined with negative priming statements. As a result of this, the findings of the reviewed studies showed a discernible bias on the part of the researchers when they manipulated just a limited set of ecologically valid instructions about how the participants should act.

Conceptual issues

Understanding theoretical work and providing conceptual definitions of constructs rigorously are prerequisites for good measurement and manipulation strategies, which increase the development of effective experimental manipulation (Breakwell et al., Citation2006; Chester & Lasko, Citation2021). The concept of cognitive loadFootnote8, as discussed in the introduction section, is central to Wegner's theory. Researchers often mix cognitive load with the construct of mental load, but none of the reviewed studies provided operational definitions of the constructs. While manipulating the same arithmetic task, for example, Dugdale and Eklund (Citation2003) used the term cognitive load, whereas Wegner et al. (Citation1998) used the term mental load (Study 2). Further, we identified that the reviewed studies used different variants of avoidant instructions, including avoiding instructions (Gorgulu & Gokcek, Citation2021), negative self-instructions (de la Peña et al., Citation2008, Study 1), negative instructions (Oudejans et al., Citation2013), and suppressive self-talk cues (Liu et al., Citation2015). It is surprising that the reviewed studies used the various terminologies without explicating the constructs in sport-specific contexts using Wegner's theory.

Furthermore, within the context of Wegner's theory, ironic processes are the operators’ and monitors’ pathways through which mental control are traced. Ironic effects and ironic errors, on the other hand, are both examples of behavior (performance) outcomes. When describing performance outcomes, the reviewed studies often used terminologies like ‘ironic processing incidences’, ‘ironic movement errors’, ‘ironic effects’, and ironic errors’, which may confuse researchers and sport psychologists. In particular, two studies revealed that benefiting the operator with inaction-oriented goals, such as simple positive instructions can reduce the incidence of ironic errors (Gorgulu et al., Citation2019, Studies 3 and 5). However, sport- and cognitive-psychology literature have criticized the use of dual-process approaches for oversimplifying the types of instructions employed (Fritsch et al., Citation2022; Melnikoff & Bargh, Citation2018). This raises questions concerning the reliability with which researchers may interpret thefindings from the dual (cognitive) pathways approach, as was done in the studies conducted by Gorgulu et al. (Citation2019, Studies 3 and 5). Methodological and conceptual flaws in the existing evidence on the ironic effects of motor performance casts doubt. Therefore, the findings of the reviewed studies and any general inferences regarding the efficacy of the experimental manipulations should be approached with caution.

Strengths and limitations

The review's strengths include its critical evaluation of empirical studies, which aimed to spark future interest in Wegner's theory in motor performances, and its call for more transparency and less author bias. However, it does have certain drawbacks. Because the review's scope is confined to Wegner's theory, further insights might have been missed due to the exclusion of research that tested Wegner's theory alongside alternative paradigms in motor task performances. Also, the review only includes studies that examined motor tasks in sports settings: the incidence of ironic effects influences individuals in sporting contexts similarly across different psychological performance contexts because it is a disposition (Wegner, Citation1997b).

Due to sizable heterogeneity in the reviewed studies, our attempt to categorize studies and synthesize the results using both statistical and narrative approaches could be seen as a limitation. This is because combining both approaches may imply that true-experimental studies are equally important as quasi-experimental studies in explaining the direction of the manipulation effects reported. Furthermore, our approach to grouping studies merges those that use ecologically valid cognitive load stressors with those that do not. This is particularly true in dual-task-based studies. However, we do not think these limitations affect the conclusions of the current review because its primary goal was to explain what ironic effects are, how the cognitive load manipulation techniques work, how effective the manipulations are, and whether they can be used in sporting contexts.

Future directions

Based on this review, future studies should consider the following to further advance Wegner's theory. Sample classification frameworks (McKay et al., Citation2022; Swann et al., Citation2015) may be used to address the gaps in the explanatory power of the reviewed studies on categorizing participants’ skill levels, especially highly trained and elite participants. Due to the paucity of data, expert and professional elite athletes should be tested using ecologically valid performance stressors in various contexts.

The present review recommends using rigorous methodologies, such as randomized controlled trials, to understand the causal effects of distinct stressors on ironic errors. In addition, intervention trials are important to reduce the likelihood of ironic errors. Gorgulu et al. (Citation2019) recommended providing simple positive instructions (i.e., process goals) to mitigate the likelihood of ironic errors (Studies 3 and 5). To determine the viability of their suggestions, future research should experimentally test holistic process goals in ecologically valid professional sports. This is because training toward process goals may help performers overcome high-anxiety circumstances and focus on the most crucial aspects of their performances (Kingston & Hardy, Citation1997). Furthermore, inner and outer distractions and emotional loading such as anger and anxiety, might increase the likelihood of ironic effects (Wegner, Citation1994). Consequently, future research should develop cognitive strategies to help athletes reduce internal and external distractions while suppressing unwanted thoughts in competitive scenarios or when applying negative self-instructions. Another practical strategy to reduce the likelihood of ironic errors is to teach athletes and coaches about the phenomenon and why it is important to stay present-centered and nonjudgmental about their internal and external thoughts and feelings, which are transient incidences that come and go in the conscious mind (Gardner & Moore, Citation2004; Josefsson et al., Citation2019).

The presentation of cognitive load manipulations varies significantly in terms of intensity and frequency in the reviewed studies. Adopting the idea from Mellalieu et al. (Citation2021), future research should be explicit about the dimensions of the cognitive load construct when testing ironic errors in motor performance. These dimensions include the type of stressors (ecologically valid or limited ecologically valid stressors), the intensity of stressors (single or multiple stressors), the duration of the stressors (longer or shorter), and the frequency of the stressors (more or less frequent).

Although, as previously discussed, the present review provides promising examples in terms of cognitive load and performance measurements, future research should incorporate other cognitive load measurements, like mental effort, with more objective neuroimaging tools (EEG and fMRI) as used in sports (Tan et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, EEG and fMRI may foster future research to determine whether brain processes and determinants of thoughts influence the likelihood of ironic errors under conditions of cognitive load. In the absence of such objective measures, however, researchers can use post-experimental manipulation checks and Likert scale surveys to identify the mediating variables (Hauser et al., Citation2018).

The overriding strengths of the reviewed studies were that few studies examined potential individual variables that might moderate the cognitive load and ironic processes relationships (Barlow et al., Citation2016, Studies 1–2; Woodman & Davis, Citation2008). Working memory capacity is crucial in determining the link between the attained mental control and the ironic effects on the dual-process system (Wegner, Citation1994). As such, future research should look at how one's attention span (working memory capacity) influences their propensity to ironic errors, particularly when performing cognitively demanding motor tasks.

The reviewed studies lack a compelling theoretical rationale for using a dual-process approach for instructional manipulation. The provision of rationales safeguards the need for the research method employed, which is important for theory development and practice (Javernick-Will, Citation2018). As such, future research should focus on developing a sport-specific model to explain how the neural bases of avoidant instructions affect motor control. One approach again is to use neuroimaging technologies to investigate whether avoidant instructions on their own can tax participants’ cognitive resources, increasing the likelihood of ironic errors.

If Wegner's theory gains prominence, further consideration will need to give more thought to the operational definitions of terms like cognitive load, avoidant instructions, and the term ‘load,’ as used by de la Peña et al. (Citation2008) and Wegner et al. (Citation1998). While investigating Wegner's theory in sports context, we suggest that future studies may consider the definition of cognitive load proposed by Russell et al. (Citation2020). Furthermore, researchers should minimize their preference for manipulating lengthy instructions that may hardly have real-world applications, as this may improve the efficacy of the experimental manipulations.

Conclusion

Based on a review of twenty-four studies presented in seventeen published articles about ironic effects on motor task performance, it is apparent that further research is necessary. Future investigations of ironic processes should not be limited solely to athletes and motor performance in sports, but should also consider surgeons, healthcare professionals, and members of the armed forces. These professions may benefit from knowledge about the consequences of ironic effects on motor performance during tasks that require snap decisions and responses to ever-changing environmental stimuli. By pursuing these directions, experts working in this area can better understand how best to develop interventions aimed at reducing susceptibility to ironic effects and helping individuals and athletes thrive under high-pressure conditions in sports and other areas of life.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (69.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The term is used in this review to refer to the phenomenon of ironic effect in sports performance contexts as conceptualized in Wegner (Citation1994) and Woodman et al. (Citation2015).

2 Any action that requires motor skills, such as kicking, throwing, catching, hitting, serving, balancing, running, jumping, and so on in the context of sports performance.

3 Further subcategorized into closed (k = 16) and open (k = 8) motor tasks.

4 The assumption is explained in the context of a golf-putting task as ‘negatively worded instructions trigger an implicit (unconscious) command that exaggerates the negative meaning (e.g., "don't putt it short"), causing a compensatory interpretation of target location and/or distance’ (de la Peña et al., Citation2008, p. 1324).

5 The tendency to feel unpleasant, painful feelings, anxiety, and lack of emotional stability (Widiger & Oltmanns, Citation2017). A neurotic is someone who often experiences worry and anxiety (Bolger & Schilling, Citation1991).

6 These terms have specific uses in mainstream psychology (Holleman et al., Citation2020; Kihlstrom, Citation2021), but this paper uses the terms to denote scenarios that closely resemble competitive stressors and environments.

7 These may include ‘scant physical, mental, technical, or tactical preparations, external expectations, self-presentation, and opponents’ (Mellalieu et al., Citation2009, p. 731).

8 For a detailed explanation of the cognitive load construct, we refer to Paas et al. (Citation1994) work.

References

- Bakker, F. C., Oudejans, R. R. D., Binsch, O., & Van Der Kamp, J. (2006). Penalty shooting and gaze behavior: Unwanted effects of the wish not to miss. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 37(2-3), 265–280.

- Barlow, M., Woodman, T., Gorgulu, R., & Voyzey, R. (2016). Ironic effects of performance are worse for neurotics. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 24, 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.12.005

- Berman, M. (2021, November 11). Novak Djokovic's Grand Slam bid ends in stunning US Open final loss to Daniil Medvedev. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2021/09/12/novak-djokovics-grand-slam-bid-ends-in-stunning-us-open-final-loss-to-daniil-medvedev/

- Binsch, O., Oudejans, R. R. D., Bakker, F. C., Hoozemans, M. J. M., & Savelsbergh, G. J. P. (2010a). Ironic effects in a simulated penalty shooting task: Is the negative wording in the instruction essential? International Journal of Sport Psychology, 41(2), 118–133.

- Binsch, O., Oudejans, R. R. D., Bakker, F. C., & Savelsbergh, G. J. P. (2010b). Ironic effects and final target fixation in a penalty shooting task. Human Movement Science, 29(2), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2009.12.002.

- Bolger, N., & Schilling, E. A. (1991). Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality, 59(3), 355–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00253.x

- Breakwell, G., Hammond, S., Fife-Schaw, C., & Smith, J. A. (Eds.). (2006). Research methods in psychology (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Campbell, M., McKenzie, J. E., Sowden, A., Katikireddi, S. V., Brennan, S. E., Ellis, S., Hartmann-Boyce, J., Ryan, R., Shepperd, S., Thomas, J., Welch, V., & Thomson, H. (2020). Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. The British Medical Journal, 368, l6890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890

- Chester, D. S., & Lasko, E. N. (2021). Construct validation of experimental manipulations in social psychology: Current practices and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620950684

- de la Peña, D., Murray, N. P., & Janelle, C. M. (2008). Implicit overcompensation: The influence of negative self-instructions on performance of a self-paced motor task. Journal of Sports Sciences, 26(12), 1323–1331. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802155138

- Dugdale, J. R., & Eklund, R. C. (2003). Ironic processing and static balance performance in high-expertise performers. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74(3), 348–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2003.10609102

- Ely, F. O., Jenny, O., & Munroe-Chandler, K. J. (2021). How intervention research designs may broaden the research-to-practice gap in sport psychology. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 12(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2020.1798573

- Fleiss, J. L. (1971). Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin, 76(5), 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031619

- Frankish, K. (2010). Dual-process and dual-system theories of reasoning. Philosophy Compass, 5(10), 914–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2010.00330.x

- Fritsch, J., Feil, K., Jekauc, D., Latinjak, A. T., & Hatzigeorgiadis, A. (2022). The relationship between self-talk and affective processes in sports: A scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.2021543

- Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2004). A mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach to athletic performance enhancement: Theoretical considerations. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 707–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80016-9

- Gayman, A. M., Fraser-Thomas, J., Dionigi, R. A., Horton, S., & Baker, J. (2017). Is sport good for older adults? A systematic review of psychosocial outcomes of older adults’ sport participation. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 164–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1199046

- Gledhill, A., Forsdyke, D., & Murray, E. (2018). Psychological interventions used to reduce sports injuries: A systematic review of real-world effectiveness. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(15), 967–971. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097694

- Goddard, S. G., Stevens, C. J., Jackman, P. C., & Swann, C. (2021). A systematic review of flow interventions in sport and exercise. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1923055

- Goldberg, L. R. (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In I. Mervielde, I. Deary, F. De Fruyt, & F. Ostendorf (Eds.), Personality psychology in Europe (7th vol) (pp. 7–28). Tilburg University Press.

- Gorgulu, R. (2019a). An examination of ironic effects in air-pistol shooting under pressure. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 4(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4020020

- Gorgulu, R. (2019b). Counter-intentional errors of basketball free throw shooting under elevated pressure: An educational approach of task instruction. Journal of Education and Learning, 8(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v8n2p89

- Gorgulu, R. (2019c). Ironic or overcompensation effects of motor behaviour: An examination of a tennis serving task under pressure. Behavioural Sciences, 9(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9020021

- Gorgulu, R., Cooke, A., & Woodman, T. (2019). Anxiety and ironic errors of performance: Task instruction matters. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 41(2), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2018-0268

- Gorgulu, R., & Gokcek, E. (2021). The effects of avoiding instructions under pressure: An examination of the volleyball serving task. Journal of Human Kinetics, 78(1), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2021-0039.

- Gray, R., Orn, A., & Woodman, T. (2017). Ironic and reinvestment effects in baseball pitching: How information about an opponent can influence performance under pressure. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 39(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2016-0035

- Gröpel, P., & Mesagno, C. (2019). Choking interventions in sports: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(1), 176–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1408134

- Gunnell, K., Poitras, V. J., & Tod, D. (2020). Questions and answers about conducting systematic reviews in sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1695141

- Haddaway, N. R., Bernes, C., Jonsson, B.-G., & Hedlund, K. (2016). The benefits of systematic mapping to evidence-based environmental management. Ambio, 45(5), 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0773-x

- Hall, C. R., Hardy, J., & Gammage, K. L. (1999). About hitting golf balls in the water: Comments on Janelle’s (1999) article on ironic processes. The Sport Psychologist, 13(2), 221–224. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.2.221

- Hardy, J., Oliver, E., & Tod, D. (2009). A framework for the study and application of self-talk within sport. In S. D. Mellalieu, & S. Hanton (Eds.), Advances in applied sport psychology: A review (pp. 37–74). Routledge.

- Hauser, D. J., Ellsworth, P. C., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Are manipulation checks necessary? Frontiers in Psychology, 9), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00998

- Holleman, G. A., Hooge, I. T. C., Kemner, C., & Hessels, R. S. (2020). The ‘real-world approach’ and its problems: A critique of the term ecological validity. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00721

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., & O’Cathain, A. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Janelle, C. M. (1999). Ironic mental processes in sport: Implications for sport psychologists. The Sport Psychologist, 13(2), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.2.201