ABSTRACT

In sports literature, the study of the participation of people with disabilities has largely focused on physical activity and leisure. Both within, and across, these contexts, participation is an ambiguous term. To date, there has been no systematic review of how participation is understood in research within organized sport. The aim of this study was to fill this knowledge gap and add to the body of research on participation and disability sports. The project involved a systematic review of relevant literature. Within included studies (N = 58), researchers mostly understood participation as attendance. The involvement dimension was only considered in 31% of studies, however, results show that involvement is particularly challenging to measure. Participation was studied in relation to three overarching themes: ‘Sports for all’, as a means of achieving ‘The good life’ and ‘Normalcy’. Within organized sport, more research is needed that explores the participation of people with disabilities for its inherent value, rather than viewing it as a means or an end. Moreover, when studying subjective experiences of participation, it is recommended that researchers choose empirical, rather than ideological, approaches. Finally, researchers should be deliberate in their choice of quantitative designs due to the often-small sample sizes.

Introduction

Participation in varied aspects of life at home and in the community, for instance in recreation and sport, is important for the well-being and quality of life for all individuals, including those with disabilities (Moeijes et al., Citation2018). As such, participation is looked upon as a basic need and is therefore protected by human rights conventions such as the United Nations Conventions on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, Citation2006). Individuals with disabilities being less physically active compared to their able-bodied counterparts (Shields & Synnot, Citation2016) and less well represented in organized sports (OS) (Katsarova, Citation2021) is therefore both a political concern and a matter of individual and public health. The importance of participation in physical activity (PA) has led to an increase in studies focusing on barriers to PA and necessary sociostructural changes to substantiate the positive outcomes of sport such as building activity competence, peer-relationships and improved mental and physical health (e.g. Jaarsma et al., Citation2014; Shields et al., Citation2012).

Participation has been studied extensively over the past two decades, but with a conceptual ambiguity and with various measurement methods (e.g. Dijkers, Citation2010). How participation is understood, defined and measured may depend on how the targeted work is linked to professional fields or contexts (e.g. Dean et al., Citation2016). For instance, in rehabilitation, an individual’s ability to participate in ‘normal’ life situations is regarded as being the ultimate goal (Cardol et al., Citation2001). In parasports, political work and research on participation has been largely concentrated around accessibility and inclusion (e.g. Kiuppis, Citation2018; UN, Citation2006) perhaps since people with disabilities’ access to sport has been (and continues to be) a social struggle (Marcellini, Citation2018). Further, the study of human movement used to be a natural science concern (Loland & McNamee, Citation2017) held by realist philosophers of science (Maguire, Citation2011). Issues related to the field of parasports understanding of participation might impact and limit how participation is defined and measured within the context of organized sport and also how this relates to other areas of study.

Some researchers (e.g. Saebu & Sørensen, Citation2011; Wilhite & Shank, Citation2009) define participation as ‘involvement in a life situation’ in line with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), a framework developed by the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2001). In ICF, participation is operationalized as an individual’s degree of daily functioning and ability to perform ‘normal’ social roles with the able-bodied population as the basis of comparison. ICF’s definition of participation has received criticism for being centered around observable measures of ‘how much’ and ‘how well’ a person participates and that subjective experiences of participation are not considered (Dean et al., Citation2016; Ueda & Okawa, Citation2003).

Other studies adopt a definition of participation that considers both the observable and the subjective aspect of participation. Imms et al. (Citation2017) refer to these aspects as the quantitative and qualitative components of participation, defined in the Family of Participation Related Constructs (fPRC) as ‘attendance’ and ‘involvement’ respectively. In fPRC, the importance of measuring both dimensions are emphasized, as well as the interactional relationship between participation, the individual who participates and the surrounding environment in which participation takes place.

Studies considering subjective experiences (i.e. involvement) within the participation literature, have focused on how to create optimal participation experiences, often termed quality participation. Quality participation is substantiated by important experiential aspects (autonomy, belongingness, challenge, engagement, mastery and meaning) from participating in an activity (Martin Ginis et al., Citation2017). The Quality Parasport Participation Framework (Evans et al., Citation2018) has proven especially enlightening regarding facilitating optimal experiences for people with disabilities by delineating how to reinforce quality participation within the parasport context.

Existing systematic reviews on the participation of PWD in sports are mostly conducted under the umbrella of PA or leisure time PA (LTPA) (e.g. Bult et al., Citation2011). In recent reviews where researchers have been concerned with the OS context in particular, the focus is placed on barriers to participation (Jaarsma et al., Citation2014), the impact of OS as a means to achieve positive health outcomes (Sahlin & Lexell, Citation2015) and the contextual conditions for special populations in youth sports (Martin, Citation2019). A systematic review of how the participation of PWD is conceptualized and studied within OS can contribute to promoting knowledge within fields of participation and parasports research, and the intersection between PWD and participation in sports. The aim of this study is twofold. Within the context of organized sport, we will explore (a) how researchers’ study, define and measure participation, and (b) what researchers are concerned with when studying the participation of PWD within this context.

For the purposes of this study, we are interested in the context of organized sport, regardless of the design or level of the activity (i.e. integrated, segregated, Paralympics, Deaflympics). Throughout the study we use the term parasports and understand this as all types of organized sport activities for PWD. Regarding type of disability, we included four main categories; physical disability, vision impairment, hearing impairment and intellectual disability (including neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and activity-deficit/hyperactivity-disorder (ADHD)).

Approach

A systematic, configurative review was undertaken underpinned by epistemological constructionism. The social constructionist perspective assumes that knowledge is a human and social construction (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1967). Within constructionism it can be assumed that researchers’ analysis of the data material would yield diverse perspectives and themes as interpretation is permeated by subjectivity (Madill et al., Citation2000). Hence, this perspective does not seek consensus but instead views the diverse and perhaps complementary perspectives (of researchers) as an opportunity to provide a fuller understanding of a social phenomenon. Configurative reviews are conducted with the goal of arranging information and developing concepts and enlightenment through interpretation (Gough et al., Citation2012).

Research protocol and search strategy

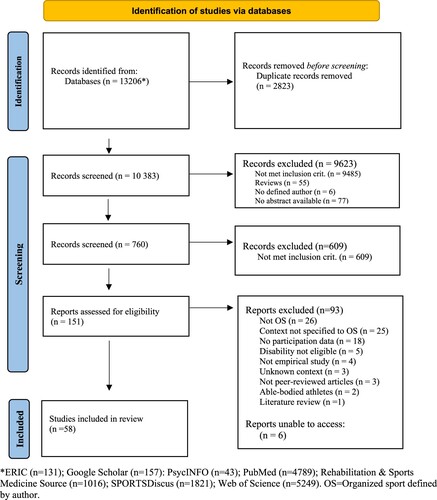

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with Preferred-Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines (PRISMA) (Page et al., Citation2021). Reporting and critical appraisal was upheld through following the PRISMA-P checklist (Shamseer et al., Citation2015) (Appendix, Table A). An online search was conducted in seven databases, including PsycINFO, Web of Science, PubMed, ERIC, SPORTSDiscus, Rehabilitation & Sports Medicine Source, and Google Scholar up until May 2022. These databases cover comprehensively all relevant literature within disability, participation studies and sport sciences and are well established in the academic community. Main keywords included ‘people with disabilities’ in combination with ‘participation’ and ‘sports’. A Microsoft Excel® Spreadsheet with synonyms of keywords limited to each database was generated as each database required unique procedures in the construction of a search strategy (combination of MeSH-terms and free text words). A shortened version of the spreadsheet is attached in Appendices (Table B). Library staff assisted test searches before the final search was run.

Criteria for inclusion and screening process

Another step that was taken to ensure search string quality was to design relevant exclusion and inclusion criteria (). Following these criteria, the first author led the process of identifying eligible articles by use of the screening tool Systematic Review Accelerator (SR-accelerator; www.sr-accelerator.com). Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded consecutively. First, articles were screened by title. Second, two independent reviewers later compared in SR-accelerator reviewed abstracts. Discussion was initiated between the authors until agreement was reached, yielding 151 articles relevant for full text screening. The first author completed full text screening with assistance of the second author in cases where the first author was unsure according to established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Inclusion- and exclusion criteria.

In the disability sports literature, the term ‘parasports’ is often used interchangeably with terms such as disability sport, adaptive sports, inclusive sports and even Paralympic sports (e.g. Patatas et al., Citation2020; Vanlandewijck & Thompson, Citation2011). For instance, according to Patatas et al. (Citation2020), Paralympic sports and parasports are part of disability sports, but not all disability sports are Paralympic sports. Further, Robinson et al. (Citation2023) distinguishes between adapted sport (i.e. sport modifications encouraging the participation of PWD in integrated environments) and parasports/disability sports (understood as segregated sport activities for PWD). In this study, studies that are conducted within the context of OS, regardless of the design or level of activity (i.e. integrated, segregated, mainstream, Paralympics), will be included. OS is defined according to Guttmann (Citation2004), comprising three components: competition, physical activity and structures underpinned by rules or laws.

Four main categories of disability included are: physical disability, vision impairment, hearing impairment, and intellectual disability. After a careful assessment, we understand the context (i.e. OS) as crucial in answering the research question, with the type of disability of less importance. At the same time, we are aware that the type of disability can be decisive for whether someone can participate in sports or not, both in terms of safety and fair competition (e.g. Blauwet & Gundersen, Citation2022; Tweedy et al., Citation2014).

Characteristics of final sample

The initial database search identified 13,206 records where 151 reports were assessed for eligibility. Six reports could not be obtained, and 93 reports were excluded, leaving 58 studies considered for data extraction (). A comprehensive table of study characteristics was made from data extraction of the final sample (see ). Characteristics of the final sample include; author(s) and title, study design/method, source of information, participation measure (i.e. attendance, involvement, both), main findings, and generated descriptive theme(s).

Table 2. Characteristics of the included studies.

Synthesis of information

In the synthesis of information, configurative reviews are typically interested in identifying patterns provided by heterogeneity (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009). A data-based convergent synthesis design was adopted making it possible to interpret qualitative and quantitative studies collectively and present findings together (Hong et al., Citation2017).

The findings from the included articles formed the basis for coding and generating descriptive and analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The synthesis was done in three stages, according to Thomas and Harden (Citation2008) by line-by-line coding of text (here; findings of included studies), developing descriptive themes, and generating analytical themes. Descriptive themes were generated in two stages; first, line-by-line coding of findings of the included studies and secondly, these codes were grouped into overall themes so that ‘translation’ between studies was possible. With regard to the stated aim of emphasizing what researchers are concerned with when studying participation within the OS context, there is a need to go ‘beyond’ mere thematizing of findings of the included studies. Thus, analytical themes will be generated from third-order-interpretation of descriptive themes. The process of coding and developing themes was ongoing throughout the review process in discussions between the authors. Data are presented narratively with schematic and tabular accompaniment.

Risk of bias

The quality of each article in the final sample was assessed according to (Kmet et al., Citation2004) standard quality assessment criteria (Appendix, Table C1 and C2). To reduce rating bias, the first and second author separately reviewed quantitative and qualitative study according to the checklist, following a 14-item checklist for the quantitative studies and a 10-item checklist for qualitative studies (2 = fully meets the criteria, 1 = partially meets the criteria, 0 = does not meet the criteria). Items not applicable to a particular study were marked with ‘n/a’. Each article received a total score calculated as a percentage against the full possible score. Furthermore, trends of the quality assessment are assessed across studies linked to the quality criteria. Finally, results are assessed in light of trends in the appraisal.

Results

Study characteristics

presents a comprehensive overview of the characteristics of included studies, while provides a summary of these characteristics. Of the quantitative studies (n = 43), 38 adopted a cross sectional design and five adopted a longitudinal design. All qualitative studies (n = 15) were cross sectional. Of the 43 quantitative papers, data were gathered by questionnaire (n = 34), publicly available data (n = 6), interview (n = 2) or anthropometric and coordinative measurements (n = 1). Of the 15 qualitative papers, data were gathered by interview (n = 7), focus groups (n = 1), autoethnography (n = 1), or by combining several data collection methods (n = 6). Observation was used in combination with other data collection methods in six of the qualitative studies.

Table 3. Summary of study characteristics of the included studies.

Definition of participation

Only three of the 58 studies presented an explicit definition of participation. In two articles, participation was defined as ‘full and effective participation that considers both the quantity and the quality of an individual’s participation’, also termed ‘quality participation’ (Allan et al., Citation2018, p. 3; Arbour-Nicitopoulos et al., Citation2022, p. 18). Sivaratnam et al. (Citation2021) defined participation according to fPRC (Imms et al., Citation2017). Last, Fiorilli et al. (Citation2013) did not define participation but defined ‘participation restrictions’ as ‘(…) problems an individual may experience in involvement in life situations … ’ (p. 3684) in line with ICF.

Since few researchers included an explicit definition of participation, there was a need to explore researchers understanding of participation in light of the researcher's rationale for studying the phenomenon, their applied framework, their philosophical standpoint, and/or how participation was measured. Some scholars made use of established frameworks, however, without thoroughly familiarizing themselves with underlying concepts. For instance, Sivaratnam et al. (Citation2021) understood and measured involvement as ‘how much’, consequently viewing it as a construct possible to measure by observation. In fPRC it is emphasized that in exploring involvement one must also consider ‘what’ the athlete is involved with, measured from the perspective of the individual (Imms et al., Citation2017). The fact that participation appears to be an ambiguous term that is understood and measured differently among disability scholars, calls for transparency in defining the term, and a more coherent and careful use of concepts within theoretical frameworks.

Despite only having included studies within the context of OS, approximately half of the studies within this review adopted a functional/rehabilitative rational for exploring participation (i.e. addressing sport as a means of increasing daily functioning). That participation is understood in a functional/rehabilitative perspective is also shown in the use of the ICF framework developed by WHO (Citation2001) and commonly used in studies concerning health and functioning (Leonardi et al., Citation2022).

In several of the qualitative studies, researchers neither make use of established frameworks such as the ICF or fPRC, nor explicitly present how they understand participation. Instead, researchers’ rationale for exploring participation is built on the basis of established concepts within the disability research field, such as ablemindedness or supercrip, in connection with the OS context. Instead of defining participation then, researchers chose to define or explain how they understand the term ‘disability’ (e.g. Jeffress & Brown, Citation2017) or how features of sport (e.g. its connection with ‘ability’ and performance) affects PWD. In similar cases where other concepts were at the foreground, researchers’ understanding of participation was based on how they measured it (i.e. as attendance, involvement or both) and/or which data collection methods researchers chose to generate knowledge on PWDs’ participation in OS.

Measures of participation

Forty (67%) of the included studies measured participation only through the attendance dimension, and these were all quantitative studies. Methods used to obtain data on attendance were frequency (n = 21), yes/no (n = 7), duration (n = 5), as completion of season (n = 1) or a combination of these (n = 6). Three studies used range of activities (RofA) an individual takes part in combined with frequency. One study (Ryan et al., Citation2018) used frequency, RofA, and the Participation and Environment Measure for Children and Youth (PEM-CY) (Coster et al., Citation2012) which is a parent-report measure of the participation and environment of children and youth.

Eighteen papers (31%) had a measure of involvement. Of these, three were quantitative studies and 15 were qualitative studies. Four of these measured both attendance and involvement. Methods used to obtain data on involvement were autoethnography, questionnaires, Likert scale answered by parents, or the Inventory of Dramatic Experiences in Sport (IDES). The most common method of generating data on involvement was through prepared interview questions targeting subjective experiences of participation directed toward feelings (‘how do you feel in training?’), concepts of participation (‘how would you describe participation?’) or embodied experiences. Studies differed in focusing on involvement limited to a specific sport (e.g. ‘how do you feel about the training in orienteering, golf or archery?’) or sport in general (e.g. ‘tell me about some of your sport experiences’). In five (35.7%) of the studies that generated data on involvement through interview or focus groups, no insight into the interview guide was given. With a few exceptions (e.g. Everett et al., Citation2020) included studies focusing on subjective experiences of participation measured this retrospectively.

Overall, these results highlight that the majority of researchers understand participation in terms of ‘being there’ and further considers participation as a concept that can be measured through observation. Further, recent studies seem to be more concerned with both participation dimensions, and in particular to include measures of involvement. Additionally, results show a diversity among the studies for how knowledge about involvement is generated.

Sources of data

Of the included studies, 84.5% measured participation with the athlete as the source of data. In ∼10% of the studies, however, the caregivers of athletes responded. In all studies where caregivers were the source of data, research participants had an intellectual disability.

Thematic synthesis and generated themes

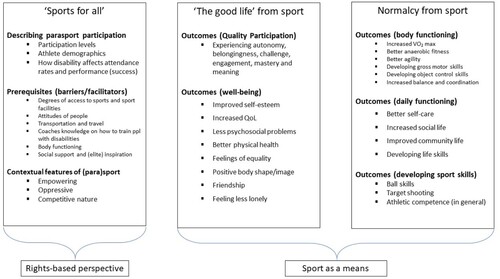

The thematic synthesis generated four overarching descriptive themes and three overarching analytical themes. The overarching analytical themes were: (1) ‘Sports for all’; (2) ‘The good life’ from sport’ and (3) ‘Normalcy from sport’ (see ). Each analytical theme and associated descriptive themes (‘Describing the participation of people with disabilities‘, ‘Prerequisites of sport participation’, ‘Contextual and environmental features of (para)sport’ and ‘Outcomes of sport participation’) contribute to providing an overview of what researchers focus on when studying the participation of PWD in OS. The descriptive themes are shown in with the degree of frequency for each theme, and the percentage of how much a theme is represented among the included studies taken together. How the analytical themes are generated and how these might reflect what researchers are concerned with in the study of PWD’s participation in OS, is described below.

Figure 2. Analytical themes related to the study of participation in sport for people with disabilities.

Table 4. Descriptive themes generated from findings of the included studies.

‘Sports for all’

The focus on the rights of PWD features in 51.8% of descriptive themes across included studies which emphasize the ‘Sport for all’-narrative and the overarching (societal) goal that sport should be accessible to all (UN, Citation1989; Citation2006). Descriptive themes indicate that researchers are concerned with highlighting how actual and circumscribed conditions of impairment/disability affect athletes’ sport participation (e.g. participation levels), as well as what conditions prevent or facilitate people with disabilities’ access to and involvement in sports (e.g. economic barriers). Hence the message of these studies, and sometimes the goal itself, is what actions are needed to set PWD free from legal, social or political restrictions within the context of OS.

In more than half of the qualitative studies, researchers link the rationale for studying PWDs’ participation to the concern for their place in organized sport. With this concern, researchers choose not to define participation, but define disability or associated terms such as ableism or supercrip (i.e. overcoming the effects of disability), and explore these concepts in relation to sports participation. Terms such as ‘ableism’, ‘supercrip’, ‘inspiration porn’, or the ability/disability dichotomy are commonly used in critical disability studies (CDS) (e.g. Smith & Sparkes, Citation2019) to which several of the qualitative studies belong (e.g. Svanelov et al., Citation2020; Swartz et al., Citation2016). Critical disability scholar’s work to challenge approaches that pathologize difference as needing correction (Reaume, Citation2014) and the importance of understanding disability as produced under historical, geographical and political conditions. As in the study by Allan et al. (Citation2018), the focus of being ‘normal’ is not about approaching a statistical norm, but about ‘feeling like a normal person’ as in having equal access and ‘being able’. Here, a concern with the ‘normal’ is linked to sport as a means for achieving social justice, advocating that athletes with disabilities have as much right to the athletic life and resources as the ‘normal’ (i.e. able-bodied) athlete (Bundon & Hurd Clarke, Citation2015 ).

Several researchers can be said to adopt a rights-based perspective, however, the researchers’ level of activism varies. In CDS, scholars often explicitly advocate for legal change. However, disability scholars might point to conditions that are unique to PWD in the context of sports without directly engaging in activism. For instance, Schipman et al. (Citation2021) point to the question of whether the classification system places restrictions on the number of competitions a given para athlete can participate in, and that the classification system leads to fewer athletes at the start in some competitions making it ‘easy’ to win. Such a perspective raises questions about fairness for athletes, but also whether sport without the competitive aspect can be considered sport? In facilitating ‘sport for all’, the competitive aspect, as part of the nature of sport, should be maintained. Studies that focus on fairness, inclusion, equality or equity, despite varying degrees of activism, are interpreted as having a rights-based focus.

‘The good life’ from sport

Researchers’ concern with sport participation as a means of increasing daily functioning, well-being or quality participation is seen as related to the search for what fundamentally constitutes ‘the good life’ and how sport participation might fulfill this. Sport participation is commonly seen as a means of achieving positive health outcomes and social integration for PWD (McVeigh et al., Citation2009; Wilhite & Shank, Citation2009), as well as OS being a context where PWD can experience belonging, mastery and independence (Martin, Citation2019). Sport participation as a means of approaching ‘the good life’ features in 23.7% of descriptive themes. Several of the studies are anchored in a Quality of Life (QoL) or psychological well-being perspective, while being more focused on how sport participation affects underlying constructs of well-being such as self-efficacy, self-esteem or physical self-concept. For instance, building upon Martin Ginis et al. (Citation2017) conceptualization of quality participation, Allan et al. (Citation2018) and Arbour-Nicitopoulos et al. (Citation2022) emphasize the role of autonomy, belongingness, challenge, engagement, mastery and meaning in fostering quality sport experiences for athletes with disabilities.

Huges (Citation2012) argues that people with disabilities are associated with a cultural history of disgust, fear and pity. As discourses around elite sports have always been positive and considered a place that creates sporting heroes (Cashmore, Citation2010), sport can act as a catalyst to overcome broader cultural logics of disability (Silva & Howe, Citation2012) and in that sense providing a gateway to ‘the good life’. The expression ‘the Olympics is where heroes are made, Paralympics is where heroes come’ (Steadward & Peterson, Citation1997, p. 8) emphasizes the effect sports (or participating in sports) has in empowering people with disabilities. Results show that sports, in addition to contributing to positive health benefits such as reduced stress and better self-care, and due to events, such as the Paralympics and Special Olympics, offers a place where PWDs’ are able to identify themselves more as athletes rather than individuals with a disability (e.g. Piatt et al., Citation2018) and are given the opportunity to experience ‘quality experiences’ such as mastery and meaning (e.g. Arbour-Nicitopoulos et al., Citation2022). ‘Becoming’ an athlete, as well as experiencing mastery and meaning, evokes feelings of competence and having social responsibility. For athletes’ self-perception and self-esteem, these experiences might challenge traditional constructions of disability as a tragedy or something to be fixed (Stiker, Citation2019).

Normalcy from sport

A concern with how sport participation is a means of approaching normalcy features in 24.5% of the descriptive themes and forms the basis for the analytical theme ‘Normalcy from sport’. Researchers seem to be concerned with how being physically active leads to changes in body structure(s) or body functioning, or how sports participation strengthens the capacity to carry out a specific task or action within a given domain (e.g. football skills at practice) or within the individuals’ current environment (e.g. contributing to the community). Such a focus indicates that there is a normal or specific way of functioning or carrying out activities, and that the possibilities of approaching ‘normality’ can be improved by means of sport. For instance, Hartman et al. (Citation2011) showed that participation in OS improved deaf children’s’ motor skill performance, and that improved balance and ball skills contributed positively to their sports participation. In this case, sport, in addition to being understood as a direct means of achieving decisive (normative) movements, is also understood as a means of promoting an active lifestyle that is considered culturally valued.

As the ICF framework additionally concerns ‘problems an individual may experience with involvement in life situations’ (p. 8), the framework also embraces the overall daily and social functioning of an individual according to a norm, not just basic skills and/or movement patterns. Using ICF to highlight problems with involvement in a ‘normal’ life, researchers are concerned with how sport is a means of participating in society as a ‘normal’ person (i.e. daily functioning) (see for instance, Morgulec-Adamowicz et al., Citation2011). Allowing PWD to have ‘typical’ community experiences seems to be a concern among disability scholars in general. For instance, in a study by May et al. (Citation2017), parents of children with ASD described how an Australian Football League Auskick program allowed their children to do something considered ‘normal’ by the wider community. With a similar perspective, Fiorilli and colleagues (Citation2013) explored whether participation in wheelchair basketball could improve players’ physical and psychological skills, thereby bridging the gap between subjects with and without disabilities.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to synthesize existing literature on the participation of people with disabilities within the context of OS. Following a configurative review process, information from included articles (N = 58) was interpreted and arranged to explore patterns of heterogeneity. Findings depict the overall ways in which participation is defined and measured, as well as what methods are used and what researchers are concerned with when studying the participation of PWD within the context of OS. In the following, findings will be discussed in depth. Moreover, in connection with both research questions, the quality of included studies will be assessed, and practical consequences of findings will be highlighted. Finally, the quality of this review will be assessed in light of trends in the quality appraisal.

Understanding and measuring participation

This review found few explicit definitions of participation, thus enforcing a focus to researchers’ rationale for studying participation, their applied framework, philosophical standpoint, or how participation was measured. Some researchers, however, made use of existing frameworks without discussing or reflecting on concepts incorporated into these frameworks, including the understanding of participation (e.g. Fiorilli et al., Citation2013; Sivaratnam et al., Citation2021). The practical significance of scholar’s lack of transparency contributes to perpetuating the ambiguity associated with participation and how to measure it. This review clarifies the need for reflexivity, both in terms of researchers’ preconceived understanding of participation and/or disability, as well as assumptions related to the participation of PWD in OS, which clearly manifests itself in the analytical themes presented.

A preponderance of studies included in this review understand, and therefore measure, participation as attendance (i.e. ‘being present’) resulting in the findings remaining in line with previous work within the participation literature (e.g. Adair et al., Citation2018). Understanding participation as an observable construct might be appropriate, and even sufficient, in research focusing on individuals with disabilities’ access or opportunities to attend sport (e.g. access to buildings or auxiliary equipment) (e.g. Bragg et al., Citation2020); or when the research is to establish participation rates with respect to, for instance, a defined period of time or context (e.g. Lauff, Citation2011). According to Imms et al. (Citation2017), however, in facilitating participation it would not be sufficient to understand, and hence measure, participation as attendance, as that would overlook the qualitative dimension. In an applied setting, for instance, a coach working with the facilitation of participation of PWD in OS, athletes’ individual preferences, and correspondingly intrapersonal factors will also be of importance (Imms et al., Citation2017). Intrapersonal factors may include self-esteem, confidence, and self-determination, being significant for an individuals’ growth.

Overall, few studies focus on involvement (i.e. subjective experiences of participating), consequently there is insufficient knowledge about athletes’ subjective experiences of participating. At the same time, results show that there is diversity among studies in how knowledge about involvement is generated, indicating involvement being a challenging dimension to understand and therefore measure. Reflecting on issues of measuring involvement among included studies, four aspects are highlighted. First, five of the studies measure involvement from the caregivers’ point of view. Measuring involvement from what is observed by others, may offer an insight into how athletes express their feelings. On the other hand, players may experience negative emotions while participating that may not be explicitly expressed or observed from the outside (Simpson et al., Citation2022). Across studies and research fields, involvement is regarded as a construct that cannot be measured other than from the viewpoint of the individual (Steinhardt et al., Citation2022). In studies where caregivers were interviewed, researchers do not sufficiently elucidate whether interviewing parents or social workers was an active choice or whether it, to a greater extent, was based on the challenging methodological steps required to interview people with intellectual impairment or autism (see for instance Mactavish et al., Citation2000; Nicholas et al., Citation2019). If researchers within parasport would value incorporating necessary method adaptations and respondent support, this might bring out interesting and important nuances or perspectives within parasport in general, and intellectual disability in particular. The willingness of researchers to do so, however, is contingent on the presumption that the perspectives of people with an intellectual disability are credible and valuable.

Secondly, the majority of studies measure involvement retrospectively. Measuring accounts of involvement retrospectively might lead athletes to describe broader generalizations about an event (semantic knowledge) as opposed to current or recent experiences (episodic knowledge) (Robinson & Clore, Citation2002). For instance, being given the opportunity to attend on an equal footing might evoke positive feelings, however, this does not necessarily mean that the athlete likes the activity. According to Gorton (Citation2007) distinctions are sometimes made between emotion (a sociological expression of feelings) and affect (a physical response rooted in biology). In principle, retrospective accounts of involvement are not problematic in research. However Scollon et al. (Citation2021) highlight that as a researcher one must be aware that semantic accounts would be more consistent with an individual’s culturally linked beliefs and values (p. 213). Even though semantic accounts should not be understood as ‘less authentic’ than episodic experiences, it is equally important to emphasize that episodic accounts might provide another insight. Simpson et al. (Citation2022) considered episodic accounts to add unique insight into children with autism's participation experiences. Results showed that children's levels and/or focus of involvement fluctuated during activity and that children displayed both negative and positive feelings while participating. In facilitating participation, this insight is valuable as it pertains to in-action changes of feelings and levels of involvement. Simpson et al. (Citation2022) used self-recorded video as a method to explore athletes’ in-the-moment experiences, which may be a method worth further consideration.

Third, all studies that measure involvement highlight that findings are linked to prerequisites of involvement (e.g. social support) or outcomes of involvement (e.g. improved self-confidence). Imms et al. (Citation2017) emphasize in fPRC the importance of separating factors that influence, or are influenced by, participation from participation itself (i.e. attendance and involvement). Regarding involvement, however, certain factors linked to involvement are considered both a prerequisite and an outcome (e.g. individual preferences). Complexity linked to the dimension of involvement specifically, makes it a challenging construct to understand and measure. Using fPRC as a framework might help clarify participation dimensions, and how to measure them.

Finally, to expand on the third point, when athletes describe their participation experiences they often highlight barriers to participation linked to the attendance dimension, instead of expressing what they feel or think while participating (i.e. the involvement dimension). As ‘ … involvement is embedded within the attendance dimension’ (Imms et al., Citation2017, p. 18) these dimensions can be challenging to separate. The British feminist scholar Reeve (Citation2008b) is especially interested in the ‘barriers in here’ arguing that the psyche is often ignored by radical structuralist sociologists more concerned with the ‘barriers out there’. Consequently, fewer interview questions might be directed at thoughts, feelings or physical sensations athletes experience while attending. In the study by Charalampos et al. (Citation2015), however, insight of subjective experiences is achieved by letting athletes narrate the interactions between themselves and the sport, making a clear distinction between their experiences with sport and the ‘value of sport’ in society. Similar, in reconceptualizing the environment as language, Hardin (Citation2001) made it epistemologically possible constructing a bridge between individual’s accounts and life stories, and the cultural, social, and historical worlds, from which those accounts emerged. As the concept of participation in general, and involvement in particular, are complex to understand and measure, scholars should carefully adapt the interview guide to elicit desired insight.

Norming of participation by social roles and cultural values

Despite the fact that PWD hold equal citizenship rights, they lack societal participation (e.g. Altermark, Citation2017). The growing body of research examining barriers to PA or leisure time clearly states scholars’ interests in the social challenges PWD face (e.g. Jaarsma et al., Citation2014; Shields et al., Citation2012). From the results of this review, it is clear that this interest also applies within the OS context. Barrier research is essential for accommodation and giving PWD access to OS. On the other hand, barrier research, emphasizing the injustice of PWD, might emphasize the differences between disability sport and mainstream sport, as well as between people with and without disabilities. Highlighting differences might widen the gap between ‘us’ and ‘them’ and challenge the understanding of sport as a place where ‘we’ (i.e. all kinds of people) participate (e.g. Irish et al., Citation2018). According to Goodley et al. (Citation2018), it is rather impossible to study disability without considering ability, and vice versa. Doing sport is strongly linked to ‘being able’, and the appearance and performance of the un-impaired body (Wickman, Citation2008), an association laying the foundation for discourses such as ‘supercrip’ and ‘inspirational porn’ (i.e. overcoming disability by showing ability). Ableist assumptions might mean that PWD’s participation in sport is at risk of always being compared to what is possible to achieve as an able-bodied.

According to Dijkers (Citation2010), there is a norming of participation by social roles and cultural values within research, presumably reflecting the broader views of society, where participation in sport is seen as an important cultural value. In a study by May et al. (Citation2017), one parent stated about their child’s participation in a sports program ‘I think the major, major one was it sort of brought some sort of normality. Like what all the other kids were doing’ (p. 136). The norming of participation does not lie in the wishes of parents, but in particular attitudes related to what is viewed as right and wrong ways to move, behave, feel, think and act (Campbell, Citation2008). Hardin (Citation2001) states that these attitudes also lead to normalizing discourses. When Gray (Citation1993) states that public encounters can be difficult for parents of children with autism because their children violate rules of social interactions and exhibit disruptive behavior, this gives an incentive to ask whether it is the children or the society with which there is something ‘wrong’. Nevertheless, knowledge on how PWD can approach ‘mainstream’ or ‘normate’ daily living is important in rehabilitation studies where participation in society, independence, and daily functioning is regarded as the ultimate goal (Standal & Jespersen, Citation2008; Thomson, Citation2017). Although, researchers should be aware that to understand participation as something you must ‘achieve’ or as if there are right or wrong ways to participate in society might direct the focus on an individual's shortcomings. In a sports context in particular, it may mean that we become particularly concerned with how athletes with disabilities’ performance differ from able-bodied athletes.

If normalizing discourses are part of everyday life (Hardin, Citation2001), discrimination in favor of able-bodied people may even take place in research, however, perhaps in subtle forms. A common criticism toward able-bodied scholars is that they, intentionally or unintentionally, eternalize the medical model of disability (i.e. emphasizing the influence of the basic impairment) in their writings (Stone & Priestley, Citation1996). By perpetuating the medical model of disability scholars might underestimate social and environmental forces affecting people to be and live in certain ways. Interestingly, Thomas and Smith (Citation2009), notes that ‘ … disability sport has been largely ignored in sport and exercise sciences (especially in the social sciences of the discipline) (…)’ (p. 1). Overall, this may mean that the part of disability research that comes from sports and exercise sciences is largely characterized by an approach to disability/impairment that focuses on how the individual can adapt to society. Disability sport being ignored in sport and exercise sciences may also be the reason why the majority of included studies originate from fields of rehabilitation and health.

One research field that emphasizes that the goal is not adapting to normality is the Adapted Physical Activity field. Within this field the focus is instead placed on providing room for exploring different movement patterns and different ways of being active (Sherrill, Citation2004). In many ways, such a perspective can be considered an alternative in approaching normalcy. Nevertheless, even if parasports have developed into an arena for sports performance, the understanding of PWD's participation in sports seems still to be influenced by origins of disability sport rooted in the rehabilitation of wounded veterans back into normal citizenship (DePauw & Gavron, Citation2005). Themes from this review can be said to be closely related; a concern for PWD's rights to participate on an equal footing with others is in many ways a concern with ‘the good life’ and ‘normalcy from sport’. There is no general coverage to ascertain that sports participation by disability scholars, knowingly or unknowingly, is primarily considered as a means. The value of disability sports, however, regardless of level, seems to be fundamentally different from the value of organized sport, which is to exercise to perform better. When Martin (Citation2019) states that the knowledge base within disability sport and exercise psychology is evolving to consider ‘ … even performance enhancement for elite wheelchair athletes’ (p. 24) this implies we still have a way to go in recognizing disability sport as a performance culture rather than a context for change.

Trends of the quality assessment

In all research, but in qualitative inquiry especially, reflexivity on the account of the researcher is linked to the quality of the study (Zitomer & Goodwin, Citation2014). It might be viewed as poor quality, therefore, that only one- third of researchers behind included qualitative studies consider how personal characteristics, assumptions, and methods used, might affect the research process and results. Looking specifically at the study of Ashton-Shaeffer et al. (Citation2001), no question was raised about the fact that respondents, as well as authors, were all from Western countries. Adopting a Foucauldian lens, one would view the body as constructed by discourse and actors (here; women in wheelchairs) having the agency to change or resist dominant discourses of patriarchal society (see for instance Yoshida & Shanouda, Citation2015). That not all women (generally speaking) are in a position to challenge their position within sport was not discussed. As this example states, researchers’ reflexive practices over how personal characteristics may affect the research process, can be considered decisive for the usability and transferability of knowledge. According to Evans and Davies (Citation2004a) researchers’ assumptions of PWD’s participation in sport might be that of society at large, which is dominated by normalized conceptions of sporting ability and performance. Given the overall themes generated in the current review, it seems researchers might be influenced by normalized conceptions of participation. Echoing taken-for-granted assumptions of parasports and disability might reinforce (outdated) attitudes in research and society (e.g. Palaganas et al., Citation2017), attitudes that may affect how PWD's talk about and view their participation in sport, as well as their motivation to participate.

Scrutinizing our assumptions about the participation of PWD in OS allowed for us not only to discover complexities that shaped our research, but we were additionally reminded that all researchers are historically, politically and contextually bound (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1967). Thus, in summarizing articles from 2001 to 2022, results will be characterized by the social understanding of disability sports during this period, as well as researcher’s current knowledge of methods and designs. Vanlandewijck and Thompson (Citation2011) notes that the historical accounts of disability sports posits a change from sport as rehabilitation, to sport as a right for people with disabilities, and finally, sport as elite (e.g. the Paralympic Movement). Results show that despite paradigm proliferation and different understandings of ‘participation’, the study of PWD's participation in sport can nevertheless be summarized in themes that are constructed across this diversity. Findings might not necessarily posit direct transferability to other contexts, however, themes and concepts might (i.e. conceptual generalization).

Almost one third of the qualitative studies do not describe their sampling strategy (e.g. type of disability, sources respondents are recruited through). In qualitative research, sampling is often called purposeful as one selects respondents who serve a specific purpose consistent with the study objective (e.g. Collingridge & Gantt, Citation2008). As such, researchers’ transparency with sampling strategy is important in deciding the quality of the study. Even though the mention trend applies to about 30% of the qualitative studies, it only amounts to four studies of which there is only one where researchers give no description or justification of their sampling strategy whatsoever.

The methodological quality of included quantitative studies is vulnerable to varying factors. For instance, 30% of studies show weakness in quality in terms of sample size, poorly described sampling strategies (including comparison group selection), in controlling for confounding variables, and in scoring partially on the point of results supporting the conclusion (Little, Citation2013). Poor quality among quantitative studies could be based on research designs with few respondents. With a small sample size, it is, for instance, challenging to control for confounding variables affecting results to such an extent that one cannot trust the conclusions. Establishing a sample size considered optimal in terms of quality as an inclusion criteria, however, we would be left with few studies to base our review on. Future research within parasports is recommended that adopts appropriate designs in relation to smaller populations, such as for instance single-case research design (Kazdin, Citation2011) or intensive longitudinal designs (Bolger & Laurenceau, Citation2013).

Overall, considering the quality of included studies, we care to emphasize the importance of the research environment continuing to focus on strategies to deal with threats to reliability and validity such as transparency, researchers’ prolonged involvement in the study, triangulation, peer debriefing and member checking (Robson, Citation2002). Further, as suggested by Zitomer and Goodwin (Citation2014), we need in qualitative research to pay more attention to the epistemological underpinnings characterizing our research and guiding our decisions (the what), than focusing on ‘how’ we conduct research as the findings of qualitative studies represent participants and researchers co-created meanings (p. 212). Finally, in future, perhaps it will be decisive for elucidating new perspectives and promoting new knowledge that researchers choose empirical, rather than ideological, approaches. Finseraas et al. (Citation2022) statement that ‘ideological homogeneity might result in unjustified confidence that some issues are settled in favor of the implicit ideological beliefs of the field so that further research on opposing theories is viewed as less important and relevant’ (p. 371) is a statement that supports such a proposal.

Limitations

In addition to the above-mentioned challenges in terms of quality, three additional limitations are highlighted. First, given the epistemological assumptions inherent in configurative reviews, other reviewers could interpret themes differently. In particular, as there were few clear definitions or descriptions of how the researchers viewed participation, it was challenging to interpret what researchers were concerned with when studying the participation of PWD in OS as well as to generate overall categories across these different understandings. Investigating researcher’s choice of method was, however, another way of exploring this that helped this process. Additionally, given that the descriptive themes are close to the original findings of the included studies (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008), and that the developed analytical themes are interpreted against existing literature on sports, participation, and disability, we believe that the conclusion is trustworthy.

Secondly, conclusions are based on existing literature in the period 2001–2022 available via research databases. Literature outside of these databases was not retrieved. This means that there may be other perspectives and ways of understanding and studying participation that are not highlighted here. Given that the keywords applied have undergone major changes over time (especially the understanding and use of the word disability) it was, however, deemed crucial for the aim of contributing to future research within sports sciences, to limit the time span to recent years. Moreover, considering this is the first overview depicting how researchers study the participation of people with disabilities in the OS context, a 20-year-time span seems feasible.

Third, most screening was executed by the first author which might have caused selection bias(es). In all steps of the process where the first author was unsure, however, a discussion with the second author was held before a decision was reached. We consider initial and mid-term calibration before full text screening could be a way to accommodate this limitation and reduce the possibility of bias.

Conclusion and future recommendations

The aim of this study was to provide an overview of how participation is understood and measured within organized sport. Furthermore, we were interested in highlighting what researchers focus on when studying the participation of people with disabilities. This review shows that researchers within the sports literature understand and measure participation as attendance, involvement, or both. In studies regarding access to sports facilities, it may well be sufficient to focus on attendance. In facilitating participation, however, it seems important to recognize involvement as well as attendance. Furthermore, this review points to the methodological challenges of measuring subjective experiences of participation. To overcome this challenge, it is important that researchers continue to explore the subjective experiences of PWD in the context of OS, by employing varied methodologies. For example, it may mean interviewing athletes while in training, athletes self-recording their experiences of participating while being involved in activities or adapting methods to ensure involvement can be measured from the perspective of the athlete, regardless of impairment.

When researchers study participation in sports for people with disabilities, they see participation in relation to rights, and as a means of achieving ‘the good life’ and ‘normalcy’. Overall, there seems to be an emphasis on optimizing (participation), and what is fundamentally having fair access (e.g. to sport facilities or a good life), against an expected standard. Researchers should be aware that this approach might not suit all research questions within the context of OS, although sport as a social institution continues to contribute to the exclusion of ‘difference’ and the favoring of ‘normal’. Our recommendation to researchers within the context of OS is to be aware of the inherent logic in understanding sport as a context for approaching normality or as a means of achieving ‘the good life’.

What has become particularly clear through the findings of this review is that more research is needed that does not see the participation of PWD as a means of improving functioning, nor as an end point of supposed ability, but rather that explores and examines the inherent nature and nuances of PWD’s participation in OS itself. Further, more research into involvement is needed, and especially in giving voice to athletes with intellectual disabilities. Our data do not exhibit types of disabilities represented across or within themes. A more in-depth study on what researchers focus on with regards to specific types of impairment can identify study topics for future research projects. Given that the majority of studies included are cross sectional, we moreover encourage consideration of longitudinal studies which can help to explore how participation in sports is experienced by PWD, also within a given period of life (e.g. the transition from child to youth sports).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (61.6 KB)Acknowledgements

This paper would not be possible without the support of Professor Åse Strandbu who contributed with repeated rounds of reading and critical appraisal of the article until the final draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first author, Linn Engdahl-Høgåsen, upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adair, B., Ullenhag, A., Rosenbaum, P., Granlund, M., Keen, D., & Imms, C. (2018). Measures used to quantify participation in childhood disability and their alignment with the family of participation-related constructs: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 60(11), 1101–1116. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13959

- *Allan, V., Smith, B., Côté, J., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2018). Narratives of participation among individuals with physical disabilities: A life-course analysis of athletes’ experiences and development in parasport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.10.004

- Altermark, N. (2017). Citizenship inclusion and intellectual disability. Routledge.

- Anan, Y. (2012). The inventory of dramatic experience for sport. In K. Hahimoto, A. Iiboshi, & M. Negami (Eds.), Physical education in university: The theory and strategy for physical education research. Fukumura Shuppan (in Japanese). (pp. 280–281).

- *Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P., Bruno, N., Orr, K., O’Rourke, R., Wright, V., Renwick, R., Bobbie, K., & Noronha, J. (2022). Quality of participation experiences in special olympics sports programs. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 39(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2021-0033

- *Ashton-Shaeffer, C., Gibson, H., Holt, M., & Willming, C. (2001). Women's resistance and empowerment through wheelchair sport. World Leisure Journal, 43(4), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2001.9674245

- *Bantjes, J., Swartz, L., & Botha, J. (2019). Troubling stereotypes: South African elite disability athletes and the paradox of (self-)representation. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(4), 819–832. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22155

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

- *Basakci Calik, B., Bas Aslan, U., Aslan, Ş, & Erel, S. (2019). Relationship between balance and co-ordination and football participation in adolescents with intellectual disability. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 41(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC-1756dba1bb

- *Bates, L., Kearns, R., Witten, K., & Carroll, P. (2019). ‘A level playing field’: Young people's experiences of wheelchair basketball as an enabling place. Health & Place, 60, 102192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102192

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

- Blauwet, C., & Gundersen, A. (2022). Medical and anti-doping considerations for athletes with disability. In D. Mottram, & N. Chester (Eds.), Drugs in sport (8th ed., pp. 428–441). Routledge.

- Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. The Guilford Press.

- *Bragg, E., Spencer, N. L. I., Phelan, S. K., & Pritchard-Wiart, L. (2020). Player and parent experiences with child and adolescent power soccer sport participation. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 40(6), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2020.1746946

- Bult, M. K., Verschuren, O., Jongmans, M. J., Lindeman, E., & Ketelaar, M. (2011). What influences participation in leisure activities of children and youth with physical disabilities? A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(5), 1521–1529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.045

- Bundon, A., & Hurd Clarke, L. (2015). Honey or vinegar? Athletes With disabilities discuss strategies for advocacy within the paralympic movement. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 39(5), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723514557823

- *Camacho, R., Castejón-Riber, C., Requena, F., Camacho, J., Escribano, B. M., Gallego, A., Espejo, R., De Miguel-Rubio, A., & Agüera, E. I. (2021). Quality of life: Changes in self-perception in people with down syndrome as a result of being part of a football/soccer team. Self-reports and external reports. Brain Sciences, 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11020226

- Campbell, F. A. K. (2008). Exploring internalized ableism using critical race theory. Disability &; Society, 23(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590701841190

- Cardol, M., de Haan, R. J., de Jong, B. A., van den Bos, G. A., & de Groot, I. J. (2001). Psychometric properties of the impact on participation and autonomy questionnaire. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82(2), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2001.18218

- *Carter, B., Grey, J., McWilliams, E., Clair, Z., Blake, K., & Byatt, R. (2014). ‘Just kids playing sport (in a chair)’: Experiences of children, families and stakeholders attending a wheelchair sports club. Disability & Society, 29(6), 938–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2014.880329

- Cashmore, E. (2010). Making sense of sports. Routledge.

- *Çelenk, Ç. (2021). Motivation affects sports and life skills in physical disabled people. Journal of Educational Psychology-Propositos y Representaciones, 9(SPE3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1161

- *Charalampos, S., Silva, C., & Kudlacek, M. (2015). When sitting becomes sport: Life stories in sitting volleyball. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity, 8(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.5507/euj.2015.003

- Collingridge, D. S., & Gantt, E. E. (2008). The quality of qualitative research. American Journal of Medical Quality, 23(5), 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860608320646

- Coster, W, Law, M, Bedell, G, Khetani, M, Cousins, M, & Teplicky, R. (2012). Development of the participation and environment measure for children and youth: conceptual basis. Disability and rehabilitation, 34(3), 238–246.

- *Crawford, C., Burns, J., & Fernie, B. A. (2015). Psychosocial impact of involvement in the Special Olympics. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 45, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.07.009

- Dean, E. E., Fisher, K. W., Shogren, K. A., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2016). Participation and intellectual disability: A review of the literature. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 54(6), 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-54.6.427

- DePauw, K. P., & Gavron, S. J. (2005). Disability sport (2nd ed. ed.). Human Kinetics.

- *Di Cagno, A., Iuliano, E., Aquino, G., Fiorilli, G., Battaglia, C., Giombini, A., & Calcagno, G. (2013). Psychological well-being and social participation assessment in visually impaired subjects playing Torball: A controlled study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(4), 1204–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2012.11.010

- Dijkers, M. P. (2010). Issues in the conceptualization and measurement of participation: An overview. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(9, Supplement), S5–S16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.10.036

- Evans, J., & Davies, B. (2004a). Pedagogy, control, identity and health. In B. Davies, J. Evans, & J. Wright (Eds.), Body knowledge and control: Studies in the sociology of physical education and health (pp. 3–18). Routledge.

- Evans, M. B., Shirazipour, C. H., Allan, V., Zanhour, M., Sweet, S. N., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2018). Integrating insights from the parasport community to understand optimal Experiences: The Quality Parasport Participation Framework. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.04.009

- *Everett, J., Lock, A., Boggis, A., & Georgiadis, E. (2020). Special olympics: Athletes’ perspectives, choices and motives. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(4), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12295

- Finseraas, H., Midtbøen, A. H., & Thorbjørnsrud, K. (2022). Ideological biases in research evaluations? The case of research on majority-minority relations. Scandinavian Political Studies, 45(3), 370–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12229

- *Fiorilli, G., di Cagno, A., Iuliano, E., Aquino, G., Calcagnile, G., & Calcagno, G. (2016). Special olympics swimming: Positive effects on young people with down syndrome. Sport Sciences for Health, 12(3), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-016-0293-x

- *Fiorilli, G., Iuliano, E., Aquino, G., Battaglia, C., Giombini, A., Calcagno, G., & di Cagno, A. (2013). Mental health and social participation skills of wheelchair basketball players: A controlled study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(11), 3679–3685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.08.023

- *Ghosh, D., & Datta, T. K. (2012). Functional improvement and social participation through sports activity for children with mental retardation. Prosthetics & Orthotics International, 36(3), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309364612451206

- *Gillespie, M. (2009). Participation patterns in an urban special olympics programme. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2008.00496.x

- Goodley, D., Liddiard, K., & Runswick-Cole, K. (2018). Feeling disability: Theories of affect and critical disability studies. Disability & Society, 33(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1402752

- Gorton, K. (2007). Theorizing emotion and affect. Feminist Theory, 8(3), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700107082369

- Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1(28), https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

- Gray, D. E. (1993). Perceptions of stigma: The parents of autistic children. Sociology of Health and Illness, 15(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11343802

- *Groff, D. G., Lundberg, N. R., & Zabriskie, R. B. (2009). Influence of adapted sport on quality of life: Perceptions of athletes with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(4), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280801976233

- Guttmann, A. (2004). Sports: The first five millennia. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Hardin, P. (2001). Theory and language: Locating agency between free will and discursive marionettes. Nursing Inquiry, 8(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1800.2001.00084.x

- *Hartman, E., Houwen, S., & Visscher, C. (2011). Motor skill performance and sports participation in deaf elementary school children. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 28(2), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.28.2.132

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Bujold, M., & Wassef, M. (2017). Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: Implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2

- *Howells, K., Sivaratnam, C., Lindor, E., Hyde, C. T., McGillivray, J., Whitehouse, A., & Rinehart, N. (2020). Can participation in a community organized football program improve social, behavioural functioning and communication in children with autism spectrum disorder? A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3714–3727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04423-5

- Huges, B. (2012). Fear, pity and disgust: Emotions and the Non-disabled imaginary. In N. Watson, A. Roulstone, & C. Thomas (Eds.), Routlegde handbook of disability studies (pp. 67–78). Routledge.

- *Ilhan, B., Idil, A., & Ilhan, I. (2021). Sports participation and quality of life in individuals with visual impairment. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -), 190(1), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-020-02285-5

- Imms, C., Granlund, M., Wilson, P. H., Steenbergen, B., Rosenbaum, P. L., & Gordon, A. M. (2017). Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 59(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13237

- *Irish, T., Cavallerio, F., & McDonald, K. (2018). “Sport saved my life” but “I am tired of being an alien!”: stories from the life of a deaf athlete. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.10.007

- Jaarsma, E. A., Dijkstra, P. U., Geertzen, J. H., & Dekker, R. (2014). Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 24(6), 871–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12218

- *Jeffress, M. S., & Brown, W. J. (2017). Opportunities and benefits for powerchair users through power soccer. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 34(3), 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2016-0022

- *Jong, R., Vanreusel, B., & Driel, R. (2010). Relationships between mainstream participation rates and elite sport success in disability sports. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity, 3(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.5507/euj.2010.002

- *Kanan, A., Jdaitawi, M., Kholif, M., Taha, N., Nasr, N., Awad, N., & Anabtawi, N. (2021). Enhancing individual with disability citizenship through participation in sport activities. International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, 9(6), 1427–1434. https://doi.org/10.13189/saj.2021.090639

- Katsarova, I. (2021, 15. February). Creating opportunities in sport for people with disabilities. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)679096

- Kazdin, A. E. (2011). Single-Case research designs. Oxford University Press.

- Kiuppis, F. (2018). Inclusion in sport: Disability and participation. Sport in Society, 21(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1225882

- Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004, 1. February). https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/48b9b989-c221-4df6-9e35-af782082280e

- *Kristen, L., Patriksson, G., & Fridlund, B. (2002). Conceptions of children and adolescents with physical disabilities about their participation in a sports programme. European Physical Education Review, 8(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X020082003

- *Lankhorst, K., Takken, T., Zwinkels, M., van Gaalen, L., te Velde, S., Backx, F., Verschuren, O., Wittink, H., & de Groot, J. (2021). Sports participation, physical activity, and health-related fitness in youth With chronic diseases or physical disabilities: The health in adapted youth sports study. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(8), 2327–2337. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003098

- *Lauff, J. (2011). Participation rates of developing countries in international disability sport: A summary and the importance of statistics for understanding and planning. Sport in Society, 14(9), 1280–1284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2011.614784

- Leonardi, M., Lee, H., Kostanjsek, N., Fornari, A., Raggi, A., Martinuzzi, A., … Kraus De Camargo, O. (2022). 20 years of ICF—international classification of functioning, disability and health: Uses and applications around the world. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811321

- *Lepers, R., Stapley, P. J., & Knechtle, B. (2014). Analysis of marathon performances of disabled athletes. Movement & Sport Sciences - Science & Motricité, 84(84), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1051/sm/2013078

- Little, T. D. (Ed.). (2013). The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods, volume 1: Foundations. Oxford University Press.

- Loland, S., & McNamee, M. (2017). Philosophical reflections on the mission of the European college of sport science: Challenges and opportunities. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2016.1210238

- *MacDonald, C., Bryan, R., Lieberman, L. J., & Foley, J. T. (2020). “You think differently after playing this sport”: experiences of collegiate goalball players. Recreational Sports Journal, 44(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558866120964812

- Mactavish, J. B., Mahon, M. J., & Lutfiyya, Z. M. (2000). “I Can speak for myself”: involving individuals With intellectual disabilities As research participants. Mental Retardation, 38(3), 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2000)038<0216:ICSFMI>2.0.CO;2

- Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712600161646

- Maguire, J. A. (2011). Human sciences, sports sciences and the need to study people ‘in the round’. Sport in Society, 14(7-8), 898–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2011.603547

- Marcellini, A. (2018). The extraordinary development of sport for people with dis/abilities. What does it all mean? Alter, 12(2), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2018.04.005

- Martin, J. J. (2019). Mastery and belonging or inspiration porn and bullying: Special populations in youth sport. Kinesiology Review, 8(3), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2019-0013

- Martin Ginis, K. A., Evans, M. B., Mortenson, W. B., & Noreau, L. (2017). Broadening the conceptualization of participation of persons With physical disabilities: A configurative review and recommendations. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(2), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.04.017

- May, C. D., St George, J. M., Fletcher, R. J., Dempsey, I., & Newman, L. K. (2017). Coparenting competence in parents of children with ASD: A marker of coparenting quality. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(10), 2969–2980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3208-z

- McVeigh, S. A., Hitzig, S. L., & Craven, B. C. (2009). Influence of sport participation on community integration and quality of life: A comparison between sport participants and non-sport participants with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 32(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2009.11760762

- Moeijes, J., van Busschbach, J. T., Bosscher, R. J., & Twisk, J. W. R. (2018). Sports participation and psychosocial health: A longitudinal observational study in children. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 702. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5624-1

- *Morgulec-Adamowicz, N., Kosmol, A., & Otrebski, W. (2011). The effect of sports participation on the intensity of psychosocial problems of males with quadriplegia in Poland. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 42, 307–320.

- *Nemček, D. (2017). Self-esteem analyses in people who are deaf or hard of hearing: A comparison between active and inactive individuals. Physical Activity Review, 5, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.16926/par.2017.05.14

- Nicholas, D. B., Orjasaeter, J. D., & Zwaigenbaum, L. (2019). Considering methodological accommodation to the diversity of ASD: A realist synthesis review of data collection methods for examining first-person experiences. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(2), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00164-z

- *Oggero, G., Puli, L., Smith, E. M., & Khasnabis, C. (2021). Participation and achievement in the summer paralympic games: The influence of income, Sex, and assistive technology. Sustainability, 13(21), 11758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111758

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(n71), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Palaganas, E. C., Sanchez, M. C., Molintas, M. P., & Caricativo, R. D. (2017). Reflexivity in qualitative research: A journey of learning. The Qualitative Report, 22(2), 426–438. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2552

- *Pan, C.-C., & Davis, R. (2019). Exploring physical self-concept perceptions in athletes with intellectual disabilities: The participation of unified sports experiences. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 65(4), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2018.1470787

- Patatas, J. M., De Bosscher, V., Derom, I., & De Rycke, J. (2020). Managing parasport: An investigation of sport policy factors and stakeholders influencing para-athletes’ career pathways. Sport Management Review, 23(5), 937–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.12.004

- *Perrier, M.-J., Sweet, S. N., Strachan, S. M., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2012). I act, therefore I am: Athletic identity and the health action process approach predict sport participation among individuals with acquired physical disabilities. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(6), 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.011

- *Piatt, J., Kang, S., Wells, M. S., Nagata, S., Hoffman, J., & Taylor, J. (2018). Changing identity through sport: The paralympic sport club experience among adolescents with mobility impairments. Disability and Health Journal, 11(2), 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.10.007