ABSTRACT

Talent development is a key topic in sport psychology research and practice. To evaluate what we currently know about the development of talent, this systematic review used a two-dimensional taxonomy to classify contemporary talent research as (1) static or dynamic, and (2) inter- or intraindividual. We focused on empirical studies in the context of soccer, in which most of the talent research so far has been conducted. Following a literature search in July 2022 of Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, and PubMed, 85 empirical studies were included. Most (n = 60) of the studies examined talent development from a static-interindividual perspective. These studies typically explored which factors explained future ability levels in groups of talented players. Only three studies explicitly examined how future ability emerged from interacting talent factors that changed over time for individual players, and were classified accordingly as dynamic-intraindividual. Hence, we conclude that most empirical studies on talent development in soccer lack data on individual temporal processes, which limits our current understanding of how talent develops. To move forward, we recommend that future studies in sports examine how talent development unfolds over time, considering the underlying dynamic and individual nature of this process.

Introduction

Across the domains of sports, education, work, and the arts, talents and experts attract much societal interest. Especially in the sports domain, significant resources are spent on efforts to attain expertise (Houlihan & Green, Citation2007). These efforts involve the identification and development of talented athletes, whereby the most promising athletes are selected and given support, guidance, and coaching to realise their potential (e.g. Fransen & Güllich, Citation2019; Vaeyens et al., Citation2008; Williams & Reilly, Citation2000). This potential, traditionally referred to as talent, is the capacity to excel and the likelihood of attaining future expertise (Baker et al., Citation2019; Cobley et al., Citation2011). Accordingly, talent development entails the process through which this capacity turns into future expert abilities (Abbott & Collins, Citation2004; Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018; Simonton, Citation1999, Citation2001). A key concern for theorists and practitioners in sports is to understand the mechanism that drives talent development (e.g. Rees et al., Citation2016). Recent decades have, therefore, witnessed a rapidly growing research interest in talent development, with a large majority of studies carried out in the context of soccer (e.g. Baker et al., Citation2020; Williams et al., Citation2020).

These studies focused initially on the question of which factors define talent and what the origins are of the factors that contribute to talent development (e.g. nature – nurture, see Baker & Horton, Citation2004; Howe et al., Citation1998). By examining differences between experts and non-experts, researchers associated various factors – including physical characteristics, psychological characteristics, and practice – with expertise levels (e.g. Gould et al., Citation2002; Reilly et al., Citation2000; Ward et al., Citation2007). As such, talent is now generally considered a multidimensional concept. This is also reflected in several theoretical models of talent development: Gagné’s (Citation2004) Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent (DMGT), Simonton's (Citation1999) emergenic-epigenetic model of talent development, Den Hartigh et al.’s (Citation2016, Citation2018) dynamic network model, and other talent development models specific to the sports domain (e.g. Elferink-Gemser et al., Citation2004; Fransen & Güllich, Citation2019; Reilly et al., Citation2000; Vaeyens et al., Citation2008).

Besides considering that multiple factors contribute to talent development, researchers aimed to understand how talent develops (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Papierno et al., Citation2005). Several studies therefore modelled the talent development process as a linear, momentary association between talent factors and age or ability, using primarily cross-sectional designs (e.g. Ericsson et al., Citation1993). However, talent development researchers increasingly suggest that expert abilities emerge from talent factors that change and combine in unique ways for different individuals (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Elferink-Gemser et al., Citation2011; Gulbin et al., Citation2013; Sarmento et al., Citation2018). Therefore, there is a growing call for studies to approach talent development as a non-linear and dynamic process. Such a conceptual approach clearly requires longitudinal study designs to examine how talent factors interact over time (e.g. Abbott et al., Citation2005; Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, Citation1994; Davids & Baker, Citation2007; Phillips et al., Citation2010).

When reviewing talent development studies, therefore, it is important to consider each study’s methodological approach, which provides insights into the perspective taken on talent and its development (Baker et al., Citation2019; Coutinho et al., Citation2016). Studies might adopt a static or a dynamic methodological approach, subject to whether the research design enables examination of how talent factors change over time (Den Hartigh et al., Citation2017). A static methodological approach proceeds, at least implicitly, from the perspective that talent development is driven by components that do not change, and thus collapses the developmental process across time. This includes, for example, studies that examine cross-sectional differences between future successful and non-successful athletes for certain talent factors at one time point. In contrast, studies that adopt a dynamic approach would focus on changes in factors and their interplay (e.g. Van Geert, Citation2009), investigating talent development as a process that unfolds over time (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2017; Hill et al., Citation2018; Stenling et al., Citation2017).

In addition to adopting a static or a dynamic approach, talent development research might also be differentiated through its focus on the interindividual (i.e. between-person) or intraindividual (i.e. within-person) level in investigating developmental processes (Van Geert, Citation2014). An interindividual methodological approach proceeds from the perspective that there is a linear, uniform developmental process in a particular population. Such an approach relies primarily on group-level statistics to associate the differences in identified talent factors and the variance in ability between groups of athletes. An example is a study that examines the mean difference in psychological characteristics to explain the difference in ability between future successful and non-successful athletes. In contrast, an intraindividual methodological approach proceeds from the perspective that the talent development process is driven by interactions amongst various components that differ across individuals (cf., Hamaker, Citation2012; Nesselroade & Molenaar, Citation2010; Van Geert, Citation2014). Such studies would repeatedly examine the same individual to understand how changes in specific talent factors and their interactions are related to the growth of ability and expertise.

In summary, research on talent development can broadly take (1) a static or dynamic, and (2) an inter- or intraindividual methodological approach. Given that these different methodological approaches are closely related to how we conceptualise the talent development process, they have important implications for our understanding of how talent develops. Therefore, in this systematic review, we used a two-dimensional taxonomy to classify empirical studies and evaluate current understanding of talent development. We focused on previous research in the context of soccer, because the great majority of research on (sport) talent so far has been conducted in this field (Baker et al., Citation2020).

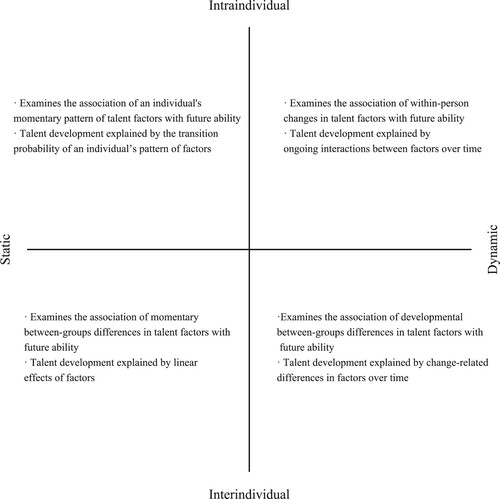

Taxonomy of talent development research in soccer

The two-dimensional taxonomy comprises a static-dynamic and an inter-intraindividual dimension, which combine into four quadrants: static-interindividual, static-intraindividual, dynamic-interindividual, and dynamic-intraindividual (see ; for similar taxonomies in other fields of psychology, see Kupers et al., Citation2019; Lichtwarck-Aschoff et al., Citation2008). As discussed in the previous section, each quadrant corresponds with a particular methodological approach and accompanying conceptualisation of how talent develops. By examining the specific method used in each eligible study, such as research design and analytical procedure, the taxonomy was used to place each study in one of the four quadrants (see Method section). Below, we provide some illustrative studies that would be assigned to each quadrant based on a common research question in talent development: To what extent does amount of soccer practice contribute to future soccer success (e.g. attaining professional or amateur level) (e.g. Haugaasen & Jordet, Citation2012)?

Empirical research in the static-interindividual quadrant typically examines to what extent a particular factor within a sample of individuals is momentarily related to becoming an expert. Hence, an exemplary study that examines the influence of soccer practice would relate the difference in accumulated hours of soccer practice at a certain age to future ability levels, such as playing (non-)professional soccer. This relationship would be examined at one point in time, or collapsed across time (static) and aggregated at the between-groups level (interindividual), from which it would be expected to hold for the individual players. A typical study from the static-intraindividual quadrant would proceed from the same static approach but would examine this relationship at the individual level. For instance, based on a particular profile of accumulated practice hours at a certain age, the likelihood of becoming a (non-)professional soccer player would be determined for each individual with similar amounts of soccer practice (e.g. Bergman & Magnusson, Citation1997).

Talent development research belonging to the dynamic-interindividual quadrant is typically focused on how the developmental process unfolds over time. These studies examine how temporal (dynamic) changes in talent factors are related to future soccer success at the between-groups level (interindividual). This could, for example, be a study that examines how changes in accumulated hours of soccer practice over time relate to future ability levels. As such, this quadrant includes studies in which variables were measured at multiple time points. Finally, studies in the dynamic-intraindividual quadrant also examine how the developmental process unfolds over time (dynamic), but at the individual level. For example, such studies might quantitatively collect or qualitatively recreate the individual time series of accumulated soccer practice hours and investigate how the trajectory of soccer practice over time relates to successful talent development.

The current study

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate current understanding of talent development. We therefore focused on the methodological approaches of empirical studies of talent development in sports. Specifically, we examined the domain of soccer, in which most studies on talent in sports have been carried out (Baker et al., Citation2020). Using the two-dimensional taxonomy, this systematic review provides an overview of the main research trends, while simultaneously identifying potential gaps in the current talent research literature. As such, our method and findings serve as an important impetus for future theoretical and practical research to advance knowledge of talent development in sports.

Method

Following recent best practices to enhance transparency, replicability, and robustness of systematic reviews in sport and exercise psychology (Gunnell et al., Citation2022), this study was registered via the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/2wvjd). In addition, a systematic review protocol was created before the start of the review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist, which also served as a template for the OSF pre-registration (Shamseer et al., Citation2015). Any amendments to the pre-registered protocol are clearly identified in the final protocol, which is included in the supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2023.2283874).

Literature search

A systematic literature search was conducted in July 2022, consisting of two stages. First, an electronic database search was carried out in the Web of Science (Core Collection), PsycINFO, Scopus, and PubMed databases. The search query for the titles, abstracts, and (author) keywords consisted of terms such as ‘talent’, ‘athlete’, ‘expert’, ‘elite’, and ‘skilled’, combined with ‘development’, ‘progression’, and ‘career’. All search results were filtered to return only English publications from 2000 onwards that had the terms ‘football’ or ‘soccer’ included in the title, abstract, or (author) keywords. A detailed overview of the search query with database-specific Boolean and proximity operators is provided in the supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2023.2283874). Second, the electronic database search was completed with a backward and forward citation search of all the studies included using the citationchaser package in R (Haddaway et al., Citation2022).

Following the primary electronic database search, the results were considered for inclusion based on three criteria. First, given our aim to evaluate current understanding of talent development in sports, we included only published empirical peer-reviewed journal articles written in English. These studies typically function as the knowledge base for researchers and practitioners in the field of talent development. As such, it was expected that excluding literature reviews, book chapters, dissertations, theses, and conference abstracts would not impact the results of our review (Hartling et al., Citation2017). Second, only studies that investigated soccer contexts were included. That is, studies that examined multiple sports were excluded if they did not present any soccer-specific findings. Third, because this review was focused on talent development, studies were included if they adopted a criterion that reflected the outcome of a developmental process, such as achievement of status (e.g. professional or non-professional level, playing for senior national teams), progression to other competitive levels (U12 to U19), or deselection. This criterion could be applied either in a prospective manner, if the performance criterion was measured at a later point in time, or retrospectively, if the study examined the historic development that led to the developmental outcome attained. The inclusion of such a ‘performance later’ (Collins et al., Citation2019, p. 3) criterion enables examination of how talent factors are associated with the growth of soccer ability (i.e. talent development, cf., Johnston et al., Citation2018). This means that cross-sectional studies that (only) compared groups at one time point and studies that tested a specific intervention (e.g. a training intervention) were excluded. In addition, this criterion provides a distinction from work focused on talent identification, which mainly examines the prognostic validity of talent predictors for selection decisions (see Bergkamp et al., Citation2019).

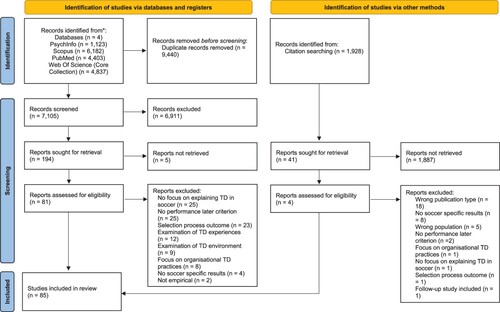

Screening process

Three assessors, including the first author, performed the title and abstract screening for inclusion. Screening decisions were recorded in Rayyan, which enabled a collaborative and independent screening process (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). When exclusion could not be determined based on information provided by the title and abstract, the article was considered for full-text screening. In the case of disagreements regarding retrieval, consensus was reached through discussion. The PRISMA flow diagram of the screening process and the numbers of retrieved and excluded articles are shown in (Page et al., Citation2021).

After retrieval, data extraction was divided among the assessors, with each assessor responsible for extracting data regarding sample size, study characteristics, and key findings from their assigned subset of articles. A cloud-based Microsoft Excel sheet was created to record the data in predefined categories to enable consistency and reliability across the data extraction process. In addition, all studies included were assessed using the updated version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., Citation2018). This tool enabled the critical appraisal of multiple study designs and methods, and was considered particularly suitable for this review given that qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies were included (cf., Quigley et al., Citation2019).

Analysis

Based on a careful reading of the full-text article and accompanying data extraction sheet, analysis was conducted by two reviewers, including the lead author. Each of the two reviewers independently classified the 85 studies into one of the four quadrants (see ). Using the two-way mixed, absolute agreement intraclass correlation coefficient, the initial inter-rater agreement for the classification was excellent (0.91; 95% CI = 0.86–0.94; Koo & Li, Citation2016). Any disagreements were discussed during meetings with all authors present, resulting in a final consensus on the classification of each study.

The classification process included an appraisal of the study’s methods, (statistical) procedure, design, and research question or aim. To determine whether a study belonged to the static or dynamic quadrant, we examined whether the methodological approach considered how temporal changes within talent factors influence the developmental process. For instance, dynamic qualitative research would examine how timing of developmental experiences led to the growth of expert abilities. Similarly, dynamic quantitative research would investigate the development of a particular ability as a function of the interaction between Adult Performance Level (e.g. professional or non-professional) and Time (or age). Note that when a study treated time (or age) solely as an independent variable, investigating a ‘main effects’ relationship between age and the outcome, it would be classified within the static quadrant (e.g. Stenling et al., Citation2017).

Classification along the inter-intraindividual dimension was based on the study’s generalisation of talent development processes to populations versus individuals. That is, interindividual studies typically proceed from the average of groups (i.e. representing particular populations) and, as part of a between-groups comparison, present results as aggregates for individual players. In contrast, intraindividual studies generalise from commonalities between within-person patterns. For instance, intraindividual qualitative research might collect diary data to find commonalities between the developmental processes of individuals. An interindividual study would, however, primarily examine how many times certain (e.g. psychosocial, practice) factors are reported across developmental biographies within groups of players. Note that we considered studies that applied multilevel models, which enable relationships between variables to randomly vary at the individual level, as interindividual. The rationale is that these studies still proceeded from the perspective of explaining the developmental process at a between-groups level.

Results

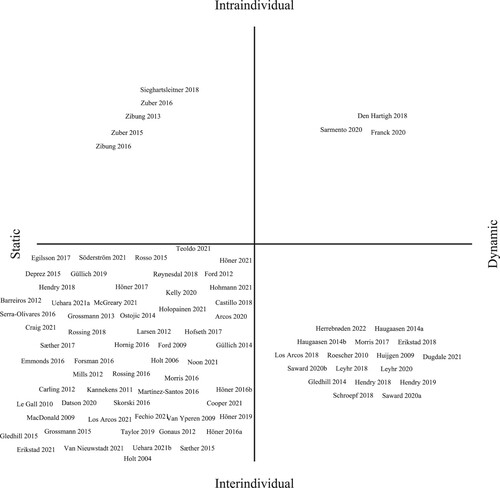

Following the electronic database search and screening, 85 studies were considered for this review. Most of these studies (n = 65; 76.5%) contained mainly quantitative data; the other 20 (23.5%) studies had mainly qualitative data. The great majority of the studies (n = 60; 70.6%) were assigned to the static-interindividual quadrant (see ). The remaining studies were classified as dynamic-interindividual (n = 17; 20.0%), static-intraindividual (n = 5; 5.9%), or dynamic-intraindividual (n = 3; 3.5%). A detailed overview of study characteristics and key findings is provided as a supplementary file (https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2023.2283874).

Figure 3. Overview of all studies classified within the two-dimensional taxonomy. Note. The references are clustered in each quadrant. Relative positions within the quadrant have no additional meaning; they were chosen for readability.

Static-interindividual quadrant

Most of the research on talent development in soccer can be classified as ‘static-interindividual’. The predominant representation of this quadrant reflects a research tradition of aggregate between-groups comparisons across future successful and non-successful players. For instance, Van Yperen (Citation2009) examined whether psychological factors could differentiate players who attained future international soccer success from players who did not. It was found that several psychological factors could successfully distinguish a group of academy players based on their performance 15 years later. Goal commitment, coping, and seeking social support were found to be predictive of future soccer success. These and the findings of other research in this quadrant highlighted that many different talent factors are related to future ability level. Several of these studies used regression models to seek predictors that explained a particular portion of the variance in an outcome, such as future ability. The talent factors that were found to be predictive of future ability level were thereby conceived as causal, underlying components of the talent development process (e.g. Forsman et al., Citation2016; Höner et al., Citation2017).

Equivalent studies in this quadrant focused mainly on anthropometrics and physical performance characteristics in young soccer players (Carling et al., Citation2012; Castillo et al., Citation2018; Craig & Swinton, Citation2021; Datson et al., Citation2020; Deprez et al., Citation2015; Emmonds et al., Citation2016; Gonaus & Müller, Citation2012; Le Gall et al., Citation2010; Los Arcos & Gonzalez-Artetxe, Citation2021; Martinez-Santos et al., Citation2016; Noon et al., Citation2021). Other typical factors related to future ability level and analysed in a similar manner are personality-related factors (Sæther, Citation2017), psychological characteristics (Höner & Feichtinger, Citation2016; Larsen et al., Citation2012), self-evaluation skills (Hofseth et al., Citation2017), competitive participation patterns (Arcos et al., Citation2020; Barreiros & Fonseca, Citation2012; Grossmann & Lames, Citation2015; Güllich, Citation2014; Sæther, Citation2015), developmental participation histories (Ford et al., Citation2009; Ford & Williams, Citation2012; Güllich, Citation2019; Hendry & Hodges, Citation2018; Holopainen et al., Citation2021; Hornig et al., Citation2016), tactical factors (Kannekens et al., Citation2011), technical skills (Höner & Votteler, Citation2016; Höner et al., Citation2019), date of birth (Grossmann & Lames, Citation2013; Kelly et al., Citation2020; Skorski et al., Citation2016), maturational status (Ostojic et al., Citation2014), the place of early development (MacDonald et al., Citation2009; Rossing et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Söderström et al., Citation2021; Teoldo & Cardoso, Citation2021; Van Nieuwstadt et al., Citation2020), socio-cultural factors (Røynesdal et al., Citation2018; Serra-Olivares et al., Citation2016; Uehara, Button, et al., Citation2021; Uehara, Falcous, et al., Citation2021), and any combination of these factors in a multidimensional design (Forsman et al., Citation2016; Hohmann & Siener, Citation2021; Höner et al., Citation2017, Citation2021).

Qualitative work in this quadrant used the perspectives of players, coaches, and other stakeholders to examine factors perceived to contribute to talent development (Cooper, Citation2021; Egilsson & Dolles, Citation2017; Fechio et al., Citation2021; Gledhill & Harwood, Citation2015; Holt & Dunn, Citation2004; Holt & Mitchell, Citation2006; McGreary et al., Citation2021; Mills et al., Citation2012; Morris et al., Citation2016; Rosso, Citation2015; Taylor & Collins, Citation2019). This has resulted in findings that primarily stress the importance of several psychological factors (e.g. motivation, commitment, self-regulation, overcoming adversity, and coping) and psychosocial factors (e.g. social support, awareness of others, family encouragement, and coach provisions) for the successful development of talent. A qualitative case study by Erikstad et al. (Citation2021), for instance, showed that talent factors often operate in interaction. The authors found that the presence of certain facilities, a great deal of informal peer-led soccer play, and good relationships among teammates and coaches all interacted to produce successful developmental outcomes within a Norwegian soccer team.

Static-intraindividual quadrant

This quadrant includes five studies, all of which proceeded from a person-oriented approach, as advocated by Bergman and Magnusson (Citation1997). Talent development was examined by looking at individual profiles and their relationship with a specific developmental outcome (e.g. Zibung & Conzelmann, Citation2013). That is, individual players were characterised in terms of patterns of variables, which were then related to an outcome such as having reached the professional or amateur soccer level. Based on the player’s likelihood of attaining a specific developmental outcome, these patterns were grouped into developmental ‘types’ and ‘anti-types’.

The studies in this quadrant that proceed from this approach examined developmental participation histories (Sieghartsleitner et al., Citation2018; Zibung & Conzelmann, Citation2013), physical fitness and technical skills (Zibung et al., Citation2016), and motivational characteristics (Zuber et al., Citation2015). One study used a multidimensional design, examining players’ motor skills, technical skills, achievement motivation, and biological maturity. In this study, Zuber et al. (Citation2016) found that individual players can be clustered in several groups, distinguished by unique patterns of variable scores, which each indicate a different likelihood of attaining success three years later. Highly skilled players, with the highest average score pattern on each factor, were shown to be most likely to attain future soccer success. In comparison, fear-of-failure and late-maturing players were found to be less likely to succeed (Zuber et al., Citation2016).

Dynamic-interindividual quadrant

This quadrant contains studies that examined how the developmental trajectories of talent factors, measured at multiple points in time, were related to future ability. This means that the interaction between time and a developmental outcome (e.g. elite or sub-elite soccer) for specific talent factors was included using aggregate group-level statistics.

Most of the studies in this quadrant examined only one specific domain of talent factors, including technical or motor skills (Huijgen et al., Citation2009; Leyhr et al., Citation2018, Citation2020), anthropometrics or physical characteristics (Dugdale et al., Citation2021; Los Arcos & Martins, Citation2018; Roescher et al., Citation2010; Saward, Hulse, et al., Citation2020), psychological skills (Saward, Morris, et al., Citation2020), coach-assessed skill ratings (Hendry et al., Citation2018), and developmental participation histories (Erikstad et al., Citation2018; Haugaasen et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Hendry et al., Citation2019). For example, Erikstad et al. (Citation2018) examined accumulated hours of soccer play and practice across childhood. They found that, over the years, hours of peer-led play increased more for future regional players than for future national team players. Other quantitative studies in this quadrant directly examined specific trajectories by looking at how they were related to successful talent development outcomes (Herrebrøden & Bjørndal, Citation2022; Schroepf & Lames, Citation2018). These studies investigated what types of career patterns over time (i.e. age) were related to appearances in the senior national team. Some career paths, such as those including appearances in different national youth teams, were more likely to result in senior selection than others.

Qualitative work in this quadrant investigated how talent factors discriminated between groups with different developmental outcomes, paying particular attention to the temporal properties of these components. For instance, Gledhill and Harwood (Citation2014) used a sequential ordering of important events and factors. This provides insight into how the developmental process unfolded over time: the results show that factors changed and (dis)appeared (e.g. the importance of siblings and fathers during early childhood). Similarly, Morris et al. (Citation2017) addressed the dynamic experiences of players during youth-to-senior transitions. They found that changes in players’ motivation, anxiety and confidence, stressors, and social support during these transitions were generally related to the successful attainment of a position in senior soccer.

Dynamic-intraindividual quadrant

Only a small minority of the talent development research in soccer can currently be classified as adopting a dynamic-intraindividual approach. This includes the work of Den Hartigh et al. (Citation2018), which showed that (quantitative) simulations of typical talent factors in dynamic network models provided developmental trajectories that aligned with individual developmental trajectories found in the real world (e.g. the number of goals scored by Lionel Messi over the course of his career at FC Barcelona). The other two studies in this quadrant used qualitative data. For instance, Franck and Stambulova (Citation2020) examined the developmental process of an individual player using a qualitative narrative approach. They examined which events (i.e. crossroads) changed the player’s facilitating and debilitating psychosocial factors during the transition from youth to senior soccer. For instance, signing a professional contract increased motivation, which subsequently led to overtraining and eventually losing the motivation to continue playing soccer (Franck & Stambulova, Citation2020). Similarly, Sarmento and Araújo (Citation2020) examined the aspect of timing and how (not) acting on career affordances at distinct moments in time had a significant effect on the attainment of future soccer success.

Critical appraisal

The outcomes of the critical appraisal ranged between 20% and 100% (M = 72%) in terms of the MMAT quality criteria that were met (Hong et al., Citation2018). For the qualitative studies, quality ranged from 40% to 100% (M = 86%). For the quantitative studies, between 20% and 100% (M = 69%) of the quality criteria were met. One study was appraised according to mixed-methods criteria, with an overall low-quality score. The methodological quality scores for the static-interindividual quadrant, dynamic-interindividual, static-intraindividual, and dynamic-intraindividual were on average 72%, 68%, 71%, and 80%, respectively. A detailed overview of the appraisal of each study using the MMAT criteria is provided in the supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2023.2283874).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate our current understanding of the development of talent. We used a two-dimensional taxonomy to classify a total of 85 empirical studies in the context of soccer as (1) static or dynamic, and (2) inter- or intraindividual. Our findings indicate that talent development research in soccer proceeds primarily from a static-interindividual approach. Given that we did not consider any cross-sectional studies, which by definition proceed from a static-interindividual approach (Stenling et al., Citation2017), the overrepresentation of this quadrant is likely even bigger. These results stress that our current understanding of how talent develops is limited, especially in the light of the literature indicating that the developmental process is dynamic and individual-specific (e.g. Abbott & Collins, Citation2004; Den Hartigh et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Phillips et al., Citation2010).

The dominant static-interindividual approach to talent development mainly provides information on the distribution of specific factors across samples of individuals (e.g. future professionals vs non-professionals). That is, such methodologies mainly investigate which factors discriminate between future ability levels in terms of the portion of variance explained (e.g. Williams et al., Citation2020). The discriminative factors are thereby assumed to behave in additive, linear, and causal ways for talent to develop (e.g. Dai, Citation2019; Overton, Citation2014). This, however, implies that the factors are, at least implicitly, assumed to remain stable and static, as dynamic changes in these factors over time are not considered (Barraclough et al., Citation2022; Den Hartigh et al., Citation2017). Consequently, these studies may provide clues about relevant factors for the development of soccer talent, but overlook the ongoing changes in, and interactions between, multiple personal and environmental talent factors.

It should be noted, too, that some studies in the static-interindividual quadrant presented contrasting findings on the importance of the talent factors identified (e.g. Johnston et al., Citation2018). For instance, two studies included in this review investigated the soccer participation history of female national team players. Güllich (Citation2019) found that participation in sports other than soccer during childhood could successfully discriminate future female national team players from lower-level players. In contrast, Hendry et al. (Citation2019) found no differences between future female national team players and varsity-only players regarding participation in other sports during childhood. One of the reasons for these contrasting findings could be that aggregated group-level findings can only ‘generalise’ to individuals if specific assumptions are met (Molenaar, Citation2004). This is referred to as the ergodicity problem, and has recently been emphasised in the area of sport sciences (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018; Neumann et al., Citation2022; cf. Glazier & Mehdizadeh, Citation2019). Accordingly, researchers increasingly stress the importance of considering how factors interact and shape an individual’s developmental process (e.g. Araújo et al., Citation2010; Den Hartigh et al., Citation2016).

Currently, only three studies are classified as having adopted such a dynamic-intraindividual approach, which indicates that the individual and dynamic nature of the talent development process is largely underexamined. While longitudinal designs are increasingly being used to investigate how temporal aspects of talent factors are related to the successful growth of soccer ability (e.g. Leyhr et al., Citation2020; Saward, Hulse, et al., Citation2020), researchers have not (yet) considered how the ongoing interactions amongst multiple factors might drive the development of talent (e.g. Barraclough et al., Citation2022; Den Hartigh et al., Citation2016). Hence, this seems a logical next step to advance our knowledge of talent development in soccer and other sport domains.

In recent years, progress has been made in the use of theoretical and methodological approaches to investigate talent development in a more holistic and dynamic manner (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018; Henriksen et al., Citation2010; Krebs, Citation2009). For instance, specific questionnaires such as the Talent Development Environment Questionnaire (TDEQ), which measures environmental factors, might be used alongside measures that focus on intrapersonal factors (Martindale et al., Citation2013). Such work might investigate the influence of the dynamic interaction of intrapersonal and environmental factors on successful talent development. Moreover, recent technological advancements have made it possible to collect multidimensional data over time, decreasing the logistic and administrative burden often associated with collecting longitudinal data. For instance, the use of smartphone apps and wearable technology such as sensors allows for high-frequency measurements that can be administered in a relatively non-invasive manner (e.g. Couceiro et al., Citation2016; Den Hartigh et al., Citation2022).

Limitations and future research

This systematic review has some limitations. First, we acknowledge that our decision to include only peer-reviewed articles written in English may have resulted in a biased sample of studies. However, it is important to note that the aim of this review was to evaluate what we currently know about the development of talent. This knowledge base is typically grounded in studies published in international, peer-reviewed journals, and unpublished studies like dissertations often use this as a reference to build on. As such, it is highly likely that the types of designs used in published studies are representative of those used in unpublished work, and that the decision to exclude these did not significantly impact the distribution of studies within the four quadrants.

Another limitation of this review is our definition of a ‘future performance’ criterion. As highlighted by Bergkamp et al. (Citation2019), most studies on talent use categorical variables that correspond to the performance level attained (e.g. professional or non-professional). However, this implicitly assumes that the attained performance level is an accurate representation of every player’s soccer ability, which is likely not the case across such broad categories. Furthermore, this makes it difficult to compare soccer ability across studies, as the contexts of competitive levels might differ in different studies (Swann et al., Citation2015). As such, the use of the future performance criterion as an inclusion criterion for our search results may have led to the exclusion of relevant literature.

While the overall quality of the qualitative studies included in this review was high (4 out of 5 quality criteria were met on average), a little over half of these studies provided enough information to assess the coherence between data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Although qualitative research can provide a rich understanding of the developmental process, authors are often unclear about (1) the specific developmental process (e.g. progression to the national team or the transition from youth to senior soccer), and (2) the duration of the developmental period under scrutiny (e.g. childhood to adulthood, or adolescence). This limits the possibility of generalising and comparing findings across qualitative studies in talent development research.

To address these limitations and enhance our knowledge on talent development, we outline below some important directions for future research. First, given the current underrepresentation of studies that adopted a dynamic-intraindividual approach, future studies should focus on both the temporal and interactive nature of the developmental process (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018). As such, future research might proceed from dynamic systems approaches (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018; Phillips et al., Citation2010) and holistic ecological approaches (e.g. DiSanti & Erickson, Citation2021; Larsen et al., Citation2013). Dynamic and/or bio-ecological frameworks enable the systematic analysis of talent development through interactions between individuals and their (proximal) environment over time. Second, as lack of information rendered it impossible to assess all MMAT criteria, especially in qualitative research, we suggest that future research provide more clarity on the analytical procedure. For instance, rather than using broad categories such as childhood or adolescence, it is important to be clear about the time period under investigation. Clear reporting on this and other methodological considerations will aid the assessment of coherence between data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and increase the overall quality of the work. Finally, for our review, we established a ‘future performance criterion’ to include work that specifically examined talent development. A particular outcome was not specified for this criterion, such as achieving super elite status (cf. Herrebrøden & Bjørndal, Citation2022), as clear and intuitive descriptions of these ability levels are missing. Therefore, we suggest that future talent development researchers thoroughly define their criterion of a(n) (un)successful developmental outcome. This will ensure that findings which relate factors to the growth of ability can be evaluated and compared across studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review reveals that current understanding of how talent develops in soccer mainly proceeds from static and interindividual approaches. While this review was focused on the domain of soccer, this is likely to be the case in other domains as well (cf. Kupers et al., Citation2019; Lichtwarck-Aschoff et al., Citation2008). This overrepresentation limits our knowledge on talent development, because the temporal and individual developmental process are largely overlooked (e.g. Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018; Stenling et al., Citation2017). As research increasingly emphasises the ongoing interactions that drive talent development processes, future studies should proceed from a dynamic and intraindividual approach. Such research will provide exciting new opportunities to improve our understanding of talent development. Rather than relying on momentary assessments of talent factors, process-oriented studies will enable the longitudinal tracking of individual athletes. As such, these studies will add to our understanding of how talent develops, and advance knowledge on talent development in sports.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (90.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (64.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lasse Buchwald and Finn Kappus for their help with screening the search results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Note: Studies analysed for the review are marked by an*

- Abbott, A., Button, C., Pepping, G., & Collins, D. (2005). Unnatural selection: Talent identification and development in sport. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 9(1), 61–88.

- Abbott, A., & Collins, D. (2004). Eliminating the dichotomy between theory and practice in talent identification and development: Considering the role of psychology. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(5), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410410001675324

- Araújo, D., Fonseca, C., Davids, K., Garganta, J., Volossovitch, A., Brandão, R., & Krebs, R. (2010). The role of ecological constraints on expertise development. Talent Development and Excellence, 2(2), 165–179.

- *Arcos, A. L., Martínez-Santos, R., & Castillo, D. (2020). Spanish elite soccer reserve team configuration and the impact of physical fitness performance. Journal of Human Kinetics, 71(1), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0085

- Baker, J., & Horton, S. (2004). A review of primary and secondary influences on sport expertise. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813042000314781

- Baker, J., Wattie, N., & Schorer, J. (2019). A proposed conceptualization of talent in sport: The first step in a long and winding road. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.016

- Baker, J., Wilson, S., Johnston, K., Dehghansai, N., Koenigsberg, A., de Vegt, S., & Wattie, N. (2020). Talent research in sport 1990–2018: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607710

- Barraclough, S., Till, K., Kerr, A., & Emmonds, S. (2022). Methodological approaches to talent identification in team sports: A narrative review. Sports, 10(6), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10060081

- *Barreiros, A. N., & Fonseca, A. M. (2012). A retrospective analysis of Portuguese elite athletes’ involvement in international competitions. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 7(3), 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.7.3.593

- Bergkamp, T. L. G., Niessen, A. S. M., den Hartigh, R. J. R., Frencken, W. G. P., & Meijer, R. R. (2019). Methodological issues in soccer talent identification research. Sports Medicine, 49(9), 1317–1335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01113-w

- Bergman, L. R., & Magnusson, D. (1997). A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 9(2), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457949700206X

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nuture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101(4), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568

- *Carling, C., Le Gall, F., & Malina, R. M. (2012). Body size, skeletal maturity, and functional characteristics of elite academy soccer players on entry between 1992 and 2003. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1683–1693. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.637950

- *Castillo, D., Los Arcos, A., & Martínez-Santos, R. (2018). Aerobic endurance performance does not determine the professional career of elite youth soccer players. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 58, 4. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0022-4707.16.06436-7

- Cobley, S., Schorer, J., & Baker, J. (2011). Identification and development of sport talent: A brief introduction to a growing field of research and practice. In J. Baker, J. Schorer, & S. Cobley (Eds.), Talent identification and development in sport: International perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203850312

- Collins, D., MacNamara, I., & Cruickshank, A. (2019). Research and practice in talent identification and development—some thoughts on the state of play. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(3), 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1475430

- *Cooper, A. (2021). An investigation into the factors affecting player development within each phase of the academy pathway in English football academies. Soccer & Society, 22(5), 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2020.1822342

- Couceiro, M. S., Dias, G., Araújo, D., & Davids, K. (2016). The ARCANE project: How an ecological dynamics framework can enhance performance assessment and prediction in football. Sports Medicine, 46(12), 1781–1786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0549-2

- Coutinho, P., Mesquita, I., & Fonseca, A. M. (2016). Talent development in sport: A critical review of pathways to expert performance. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(2), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954116637499

- *Craig, T. P., & Swinton, P. (2021). Anthropometric and physical performance profiling does not predict professional contracts awarded in an elite Scottish soccer academy over a 10-year period. European Journal of Sport Science, 21(8), 1101–1110. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1808079

- Dai, D. Y. (2019). New directions in talent development research: A developmental systems perspective. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2019(168), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20322

- *Datson, N., Weston, M., Drust, B., Gregson, W., & Lolli, L. (2020). High-intensity endurance capacity assessment as a tool for talent identification in elite youth female soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(11–12), 1313–1319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1656323

- Davids, K., & Baker, J. (2007). Genes, environment and sport performance. Sports Medicine, 37(11), 961–980. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737110-00004

- Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Cox, R. F., & Van Geert, P. L. (2017). Complex versus complicated models of cognition. In L. Magnani, & T. Bertolotti (Eds.), Springer handbook of model-based science (pp. 657–669). Springer Handbooks. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30526-4_30

- *Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Hill, Y., & Van Geert, P. L. C. (2018). The development of talent in sports: A dynamic network approach. Complexity, 2018, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9280154

- Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Meerhoff, L. R. A., Van Yperen, N. W., Neumann, N. D., Brauers, J. J., Frencken, W. G. P., Emerencia, A., Hill, Y., Platvoet, S., Atzmueller, M., Lemmink, K. A. P. M., & Brink, M. S. (2022). Resilience in sports: A multidisciplinary, dynamic, and personalized perspective. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2022.2039749

- Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Van Dijk, M. W. G., Steenbeek, H. W., & Van Geert, P. L. C. (2016). A dynamic network model to explain the development of excellent human performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00532

- *Deprez, D. N., Fransen, J., Lenoir, M., Philippaerts, R. M., & Vaeyens, R. (2015). A retrospective study on anthropometrical, physical fitness, and motor coordination characteristics that influence dropout, contract status, and first-team playing time in high-level soccer players aged eight to eighteen years. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(6), 1692–1704. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000806

- DiSanti, J. S., & Erickson, K. (2021). Challenging our understanding of youth sport specialization: An examination and critique of the literature through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s person-process-context-time model. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(1), 28–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2020.1728779

- *Dugdale, J. H., Sanders, D., Myers, T., Williams, A. M., & Hunter, A. M. (2021). Progression from youth to professional soccer: A longitudinal study of successful and unsuccessful academy graduates. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 31(S1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13701

- *Egilsson, B., & Dolles, H. (2017). “From Heroes to Zeroes” – self-initiated expatriation of talented young footballers. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 5(2), 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-10-2016-0058

- Elferink-Gemser, M. T., Jordet, G., Coelho-E-Silva, M. J., & Visscher, C. (2011). The marvels of elite sports: How to get there? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(9), 683–684. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090254

- Elferink-Gemser, M. T., Visscher, C., Lemmink, K., & Mulder, T. (2004). Relation between multidimensional performance characteristics and level of performance in talented youth field hockey players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(11-12), 1053–1063. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640410410001729991

- *Emmonds, S., Till, K., Jones, B., Mellis, M., & Pears, M. (2016). Anthropometric, speed and endurance characteristics of English academy soccer players: Do they influence obtaining a professional contract at 18 years of age? International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(2), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954116637154

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

- *Erikstad, M. K., Høigaard, R., Johansen, B. T., Kandala, N. B., & Haugen, T. (2018). Childhood football play and practice in relation to self-regulation and national team selection; a study of Norwegian elite youth players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(20), 2304–2310. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1449563

- *Erikstad, M. K., Tore Johansen, B., Johnsen, M., Haugen, T., & Côté, J. (2021). “As many as possible for as long as possible”—A case study of a soccer team that fosters multiple outcomes. The Sport Psychologist, 35(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2020-0107

- *Fechio, J. J., Peccin, M. S., & Padovani, R. D. C. (2021). Trajetória esportiva e habilidades psicológicas de jogadores de futebol da seleção brasileira [Sports trajectory and psychological skills of Brazilian national team soccer players]. Movimento, 27, e27071. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.113626

- *Ford, P. R., Ward, P., Hodges, N. J., & Williams, A. M. (2009). The role of deliberate practice and play in career progression in sport: The early engagement hypothesis. High Ability Studies, 20(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598130902860721

- *Ford, P. R., & Williams, A. M. (2012). The developmental activities engaged in by elite youth soccer players who progressed to professional status compared to those who did not. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(3), 349–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.09.004

- *Forsman, H., Blomqvist, M., Davids, K., Liukkonen, J., & Konttinen, N. (2016). Identifying technical, physiological, tactical and psychological characteristics that contribute to career progression in soccer. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954116655051

- *Franck, A., & Stambulova, N. B. (2020). Individual pathways through the junior-to-senior transition: Narratives of two Swedish team sport athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(2), 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1525625

- Fransen, J., & Güllich, A. (2019). Talent identification and development in game sports. In R. F. Subotnik, F. C. Worrell, & P. Olszewski-Kubilius (Eds.), Psychology of high performance: Developing human potential into domain-specific talent (pp. 59–92). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000120-004

- Gagné, F. (2004). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813042000314682

- Glazier, P. S., & Mehdizadeh, S. (2019). Challenging conventional paradigms in applied sports biomechanics research. Sports Medicine, 49(2), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-1030-1

- *Gledhill, A., & Harwood, C. (2014). Developmental experiences of elite female youth soccer players. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.880259

- *Gledhill, A., & Harwood, C. (2015). A holistic perspective on career development in UK female soccer players: A negative case analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.003

- *Gonaus, C., & Müller, E. (2012). Using physiological data to predict future career progression in 14- to 17-year-old Austrian soccer academy players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1673–1682. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.713980

- Gould, D., Dieffenbach, K., & Moffett, A. (2002). Psychological characteristics and their development in Olympic champions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(3), 172–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200290103482

- *Grossmann, B., & Lames, M. (2013). Relative Age Effect (RAE) in football talents – the role of youth academies in transition to professional status in Germany. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 13(1), 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2013.11868636

- *Grossmann, B., & Lames, M. (2015). From talent to professional football – youthism in German football. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10(6), 1103–1113. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.10.6.1103

- Gulbin, J., Weissensteiner, J., Oldenziel, K., & Gagné, F. (2013). Patterns of performance development in elite athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(6), 605–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.756542

- *Güllich, A. (2014). Selection, de-selection and progression in German football talent promotion. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(6), 530–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2013.858371

- *Güllich, A. (2019). “Macro-structure” of developmental participation histories and “micro-structure” of practice of German female world-class and national-class football players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(12), 1347–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1558744

- Gunnell, K. E., Belcourt, V. J., Tomasone, J. R., & Weeks, L. C. (2022). Systematic review methods. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1966823

- Haddaway, N. R., Grainger, M. J., & Gray, C. T. (2022). Citationchaser: A tool for transparent and efficient forward and backward citation chasing in systematic searching. Research Synthesis Methods, 13(4), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1563

- Hamaker, E. L. (2012). Why researchers should think “within-person”: A paradigmatic rationale. In M. R. Mehl & T. S. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 43–61). The Guilford Press.

- Hartling, L., Featherstone, R., Nuspl, M., Shave, K., Dryden, D. M., & Vandermeer, B. (2017). Grey literature in systematic reviews: A cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-English reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0347-z

- Haugaasen, M., & Jordet, G. (2012). Developing football expertise: A football-specific research review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(2), 177–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.677951

- *Haugaasen, M., Toering, T., & Jordet, G. (2014a). From childhood to senior professional football: A multi-level approach to elite youth football players’ engagement in football-specific activities. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(4), 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.02.007

- *Haugaasen, M., Toering, T., & Jordet, G. (2014b). From childhood to senior professional football: Elite youth players’ engagement in non-football activities. Journal of Sports Sciences, 32(20), 1940–1949. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.970218

- *Hendry, D. T., & Hodges, N. J. (2018). Early majority engagement pathway best defines transitions from youth to adult elite men’s soccer in the UK: A three time-point retrospective and prospective study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.009

- *Hendry, D. T., Williams, A. M., Ford, P. R., & Hodges, N. J. (2019). Developmental activities and perceptions of challenge for National and Varsity women soccer players in Canada. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.02.008

- *Hendry, D. T., Williams, A. M., & Hodges, N. J. (2018). Coach ratings of skills and their relations to practice, play and successful transitions from youth-elite to adult-professional status in soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(17), 2009–2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1432236

- Henriksen, K., Stambulova, N., & Roessler, K. K. (2010). Holistic approach to athletic talent development environments: A successful sailing milieu. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.10.005

- *Herrebrøden, H., & Bjørndal, C. T. (2022). Youth international experience is a limited predictor of senior success in football: The relationship between U17, U19, and U21 experience and senior elite participation across nations and playing positions. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.875530

- Hill, Y., Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Meijer, R. R., De Jonge, P., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2018). The temporal process of resilience. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 7(4), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000143

- *Hofseth, E., Toering, T., Jordet, G., & Ivarsson, A. (2017). Self-evaluation of skills and performance level in youth elite soccer: Are positive self-evaluations always positive? Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 6(4), 370–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000094

- *Hohmann, A., & Siener, M. (2021). Talent identification in youth soccer: Prognosis of U17 soccer performance on the basis of general athleticism and talent promotion interventions in second-grade children. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.625645

- *Holopainen, S., Lyyra, N., & Kokkonen, M. (2021). Training and motivation in childhood and adolescence in Finnish elite footballers at different phases of their athletic careers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 21(6), 3476–3482. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2021.06471

- *Holt, N. L., & Dunn, J. G. H. (2004). Toward a grounded theory of the psychosocial competencies and environmental conditions associated with soccer success. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16(3), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200490437949

- *Holt, N. L., & Mitchell, T. (2006). Talent development in English professional soccer. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 37, 77–98.

- *Höner, O., & Feichtinger, P. (2016). Psychological talent predictors in early adolescence and their empirical relationship with current and future performance in soccer. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 25, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.03.004

- *Höner, O., Leyhr, D., & Kelava, A. (2017). The influence of speed abilities and technical skills in early adolescence on adult success in soccer: A long-term prospective analysis using ANOVA and SEM approaches. PLoS One, 12(8), e0182211. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182211

- *Höner, O., Murr, D., Larkin, P., Schreiner, R., & Leyhr, D. (2021). Nationwide subjective and objective assessments of potential talent predictors in elite youth soccer: An investigation of prognostic validity in a prospective study. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.638227

- *Höner, O., Raabe, J., Murr, D., & Leyhr, D. (2019). Prognostic relevance of motor tests in elite girls’ soccer: A five-year prospective cohort study within the German talent promotion program. Science and Medicine in Football, 3(4), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/24733938.2019.1609069

- *Höner, O., & Votteler, A. (2016). Prognostic relevance of motor talent predictors in early adolescence: A group- and individual-based evaluation considering different levels of achievement in youth football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(24), 2269–2278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1177658

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M. C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- *Hornig, M., Aust, F., & Güllich, A. (2016). Practice and play in the development of German top-level professional football players. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(1), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.982204

- Houlihan, B., & Green, M. (Eds.). (2007). Comparative elite sport development (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080554426

- Howe, M. J. A., Davidson, J. W., & Sloboda, J. A. (1998). Innate talents: Reality or myth? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 21(3), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X9800123X

- *Huijgen, B. C. H., Elferink-Gemser, M., Post, W., & Visscher, C. (2009). Soccer skill development in professionals. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 30(08), 585–591. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1202354

- Johnston, K., Wattie, N., Schorer, J., & Baker, J. (2018). Talent identification in sport: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0803-2

- *Kannekens, R., Elferink-Gemser, M. T., & Visscher, C. (2011). Positioning and deciding: Key factors for talent development in soccer. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 21(6), 846–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01104.x

- *Kelly, A. L., Wilson, M. R., Gough, L. A., Knapman, H., Morgan, P., Cole, M., Jackson, D. T., & Williams, C. A. (2020). A longitudinal investigation into the relative age effect in an English professional football club: Exploring the ‘underdog hypothesis’. Science and Medicine in Football, 4(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/24733938.2019.1694169

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

- Krebs, R. J. (2009). Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development and the process of development of sports talent. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 40(1), 108–135.

- Kupers, E., Lehmann-Wermser, A., McPherson, G., & van Geert, P. (2019). Children’s creativity: A theoretical framework and systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 89(1), 93–124. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318815707

- *Larsen, C., Alfermann, D., & Christensen, M. (2012). Psychosocial skills in a youth soccer academy: A holistic ecological perspective. Sport Science Review, 21(3–4), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10237-012-0010-x

- Larsen, C. H., Alfermann, D., Henriksen, K., & Christensen, M. K. (2013). Successful talent development in soccer: The characteristics of the environment. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2(3), 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031958

- *Le Gall, F., Carling, C., Williams, M., & Reilly, T. (2010). Anthropometric and fitness characteristics of international, professional and amateur male graduate soccer players from an elite youth academy. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 13(1), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2008.07.004

- *Leyhr, D., Kelava, A., Raabe, J., & Höner, O. (2018). Longitudinal motor performance development in early adolescence and its relationship to adult success: An 8-year prospective study of highly talented soccer players. PLoS One, 13(5), e0196324. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196324

- *Leyhr, D., Raabe, J., Schultz, F., Kelava, A., & Höner, O. (2020). The adolescent motor performance development of elite female soccer players: A study of prognostic relevance for future success in adulthood using multilevel modelling. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(11–12), 1342–1351. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1686940

- Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., van Geert, P., Bosma, H., & Kunnen, S. (2008). Time and identity: A framework for research and theory formation. Developmental Review, 28(3), 370–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2008.04.001

- *Los Arcos, A., & Gonzalez-Artetxe, A. (2021). Physical fitness performance, playing position and competitive level attained by elite junior soccer players. Kinesiology, 53(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.26582/k.53.1.6

- *Los Arcos, A., & Martins, J. (2018). Physical fitness performance of young professional soccer players does not change during several training seasons in a Spanish Elite Reserve Team: Club study, 1996–2013. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(9), 2577–2583. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002426

- *MacDonald, D. J., King, J., Côté, J., & Abernethy, B. (2009). Birthplace effects on the development of female athletic talent. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 12(1), 234–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2007.05.015

- Martindale, R., Collins, D., Douglas, C. J., & Whike, A. (2013). Examining the ecological validity of the Talent Development Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.718443

- *Martinez-Santos, R., Castillo, D., & Los Arcos, A. (2016). Sprint and jump performances do not determine the promotion to professional elite soccer in Spain, 1994–2012. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(24), 2279–2285. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1190460

- *McGreary, M., Morris, R., & Eubank, M. (2021). Retrospective and concurrent perspectives of the transition into senior professional female football within the United Kingdom. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 53, 101855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101855

- *Mills, A., Butt, J., Maynard, I., & Harwood, C. (2012). Identifying factors perceived to influence the development of elite youth football academy players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1593–1604. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.710753

- Molenaar, P. C. M. (2004). A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research & Perspective, 2(4), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15366359mea0204_1

- *Morris, R., Tod, D., & Eubank, M. (2017). From youth team to first team: An investigation into the transition experiences of young professional athletes in soccer. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(5), 523–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1152992

- *Morris, R., Tod, D., & Oliver, E. (2016). An investigation into stakeholders’ perceptions of the youth-to-senior transition in professional soccer in the United Kingdom. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(4), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1162222

- Nesselroade, J. R., & Molenaar, P. C. M. (2010). Emphasizing intraindividual variability in the study of development over the life span: Concepts and issues. In R. M. Lerner, & W. F. Overton (Eds.), Handbook of life-span development: Vol. 1. Cognition, biology, and methods (pp. 30–54). Wiley.

- Neumann, N. D., Van Yperen, N. W., Brauers, J. J., Frencken, W., Brink, M. S., Lemmink, K. A., Meerhoff, L. A., & Den Hartigh, R. J. (2022). Nonergodicity in load and recovery: Group results do not generalize to individuals. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 17(3), 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2021-0126

- *Noon, M. R., Eyre, E. L., Ellis, M., Myers, T. D., Morris, R. O., Mundy, P. D., Penny, R., & Clarke, N. D. (2021). The influence of recruitment age and anthropometric and physical characteristics on the development pathway of English academy football players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 16(2), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2019-0534

- *Ostojic, S. M., Castagna, C., Calleja-González, J., Jukic, I., Idrizovic, K., & Stojanovic, M. (2014). The biological age of 14-year-old boys and success in adult soccer: Do early maturers predominate in the top-level game? Research in Sports Medicine, 22(4), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2014.944303

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Overton, W. F. (2014). Relational developmental systems and developmental science: A focus on methodology. In P. C. M. Molenaar, R. M. Lerner, & K. M. Newell (Eds.), Handbook of developmental systems theory and methodology (pp. 19–65). The Guilford Press.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Papierno, P. B., Ceci, S. J., Makel, M. C., & Williams, W. M. (2005). The nature and nurture of talent: A bioecological perspective on the ontogeny of exceptional abilities. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 28(3–4), 312–332. https://doi.org/10.4219/jeg-2005-343

- Phillips, E., Davids, K., Renshaw, I., & Portus, M. (2010). Expert performance in sport and the dynamics of talent development. Sports Medicine, 40(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.2165/11319430-000000000-00000

- Quigley, J. M., Thompson, J. C., Halfpenny, N. J., & Scott, D. A. (2019). Critical appraisal of nonrandomized studies—A review of recommended and commonly used tools. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 25(1), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12889

- Rees, T., Hardy, L., Güllich, A., Abernethy, B., Côté, J., Woodman, T., Montgomery, H., Laing, S., & Warr, C. (2016). The great British medalists project: A review of current knowledge on the development of the world’s best sporting talent. Sports Medicine, 46(8), 1041–1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0476-2

- Reilly, T., Williams, A. M., Nevill, A., & Franks, A. (2000). A multidisciplinary approach to talent identification in soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 18(9), 695–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410050120078

- *Roescher, C., Elferink-Gemser, M., Huijgen, B., & Visscher, C. (2010). Soccer endurance development in professionals. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 31(03), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1243254

- *Rossing, N. N., Nielsen, A. B., Elbe, A. M., & Karbing, D. S. (2016). The role of community in the development of elite handball and football players in Denmark. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(2), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2015.1009492

- *Rossing, N. N., Stentoft, D., Flattum, A., Côté, J., & Karbing, D. S. (2018). Influence of population size, density, and proximity to talent clubs on the likelihood of becoming elite youth athlete. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(3), 1304–1313. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13009

- *Rosso, E. G. (2015). The ‘inverse relationship’ between social capital and sport: A qualitative exploration of the influence of social networks on the development of athletes. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 6(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2014.997861

- *Røynesdal, Y., Toering, T., & Gustafsson, H. (2018). Understanding players’ transition from youth to senior professional football environments: A coach perspective. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117746497

- Sarmento, H., Anguera, M. T., Pereira, A., & Araújo, D. (2018). Talent identification and development in male football: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 907–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0851-7

- *Sarmento, H., & Araújo, D. (2020). Readiness for career affordances in high-level football: Two case studies in Portugal. High Ability Studies, 32(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2020.1728191

- *Saward, C., Hulse, M., Morris, J. G., Goto, H., Sunderland, C., & Nevill, M. E. (2020). Longitudinal physical development of future professional male soccer players: Implications for talent identification and development? Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.578203

- *Saward, C., Morris, J. G., Nevill, M. E., Minniti, A. M., & Sunderland, C. (2020). Psychological characteristics of developing excellence in elite youth football players in English professional academies. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(11–12), 1380–1386. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1676526

- *Schroepf, B., & Lames, M. (2018). Career patterns in German football youth national teams – A longitudinal study. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(3), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117729368

- *Serra-Olivares, J., Pastor-Vicedo, J. C., González-Víllora, S., & Teoldo da Costa, I. (2016). Developing talented soccer players: An analysis of socio-spatial factors as possible key constraints. Journal of Human Kinetics, 54(1), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2016-0050

- Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349, g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

- *Sieghartsleitner, R., Zuber, C., Zibung, M., & Conzelmann, A. (2018). “The early specialised bird catches the worm!” – A specialised sampling model in the development of football talents. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00188

- Simonton, D. K. (1999). Talent and its development: An emergenic and epigenetic model. Psychological Review, 106(3), 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.435

- Simonton, D. K. (2001). Talent development as a multidimensional, multiplicative, and dynamic process. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(2), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00110

- *Skorski, S., Skorski, S., Faude, O., Hammes, D., & Meyer, T. (2016). The relative age effect in elite German youth soccer: Implications for a successful career. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 11(3), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0071

- *Söderström, T., Brusvik, P., Ferry, M., & Lund, S. (2021). Selected 15-year-old boy and girl football players’ continuation with football and competitive level in young adulthood: The impact of individual and contextual factors. European Journal for Sport and Society, 19(4), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2021.2001172

- Stenling, A., Ivarsson, A., & Lindwall, M. (2017). The only constant is change: Analysing and understanding change in sport and exercise psychology research. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 230–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1216150

- *Sæther, S. A. (2015). Selecting players for youth national teams – a question of birth month and reselection? Science & Sports, 30(6), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2015.04.005

- *Sæther, S. A. (2017). Characteristics of professional and non-professional football players – an eight-year follow-up of three age cohorts. Montenegrin Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 6(2), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.26773/mjssm.2017.09.002