ABSTRACT

Pupils in alternative provisions face unique educational, health, economic, and behavioural challenges. Sport and exercise-based interventions represent an innovative means of addressing these challenges. However, given the sparsity of peer-reviewed research, little is known regarding the what, how, and for whom, that facilitates successful intervention implementation. The purpose of this realist review is to address this gap and provide recommendations as to how interventions can be implemented successfully. Due to the absence of peer-reviewed literature; evidence was drawn from wider fields including interventions conducted in mainstream schools including children with similar characteristics to the target population. Nine initial-rough-programme-theories were developed including two rival theories. These data are formed to highlight the interweaving interactions within context-mechanism-outcome configurations. Sport and exercise-based interventions can influence pupils’ academic attainment, attendance, and relationships by promoting citizenship, facilitating exposure to green environments, and fostering belongingness. However, circumstances exist where changes in context or mechanism can result in contrasting outcomes. The context-mechanism-outcome configurations formed the foundations of the recommendations made to intervention developers and implementers aiming at making sport and exercise-based interventions in alternative provisions accessible and successful. Finally, findings of this paper are underpinned by the fundamental need for adequate space and resources within alternative provisions.

Statistics from January 2022 shows over 35,600 pupils attend alternative provision schools in the UK, an increase of 3,100 since 2020/2021 (Department of Education, Citation2022). There were 2097 pupils permanently excluded from mainstream education in the 2021/2022 autumn term up from 1700 in the previous academic year. Seven per cent of children excluded from mainstream education go on to achieve a pass grade in English and Maths GCSEs (Department for Education, Citation2019). Exclusion has detrimental impacts on pupils’ physical, mental, social health and, academic attainment (Arnez & Condry, Citation2021; Department for Education, Citation2019, Citation2021a; Gerlinger et al., Citation2021). More specifically, excluded pupils are at an increased risk of mental health issues, participation in antisocial behaviours such as substance and alcohol abuse, sexual risk taking and involvement with the criminal justice system (Tejerina-Arreal et al., Citation2020). It is estimated that each cohort of pupils excluded creates an additional cost of £2.1 billion in education, health, social welfare, and criminal justice costs over their lifetime (Department for Education, Citation2019; Gill et al., Citation2017).

Young people can be excluded for a plethora of reasons with the most common relating to in class aggression, abusive and violent behaviour, bullying, and drug and alcohol use on school premises (Department for Education, Citation2019). Young people may also be excluded for other reasons such as behavioural complications and complex needs such as Special Educational Needs and Disabilities, mental ill health and previous childhood trauma where a mainstream school cannot provide suitable education (Department for Education, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; McShane, Citation2020). Indeed, boys who have a special educational needs and disability classification, from disadvantaged backgrounds, living in high areas of deprivation, and being supported by social care, or being from ethnic minority communities present the greatest risk of being excluded. Moreover, 78% of exclusions issued were to pupils who had one of the following: special educational needs and disability classification, eligible for free school meals or additional complex needs. Whilst 11% of exclusions were given to pupils who possessed all three characteristics (Department for Education, Citation2021a).

In the UK, when a pupil is permanently excluded from mainstream education, they are transferred into an alternative provision. Alternative provisions include pupil referral units, short stay schools, education centres, hospital schools, and special schools. Unlike mainstream education schools, alternative provisions have a flexible curriculum whereby they can develop a more tailored learning option for pupils (Quarmby et al., Citation2022). In practice, this means alternative provisions can promote a vocational curriculum (e.g. sports and exercise opportunities, programmes and interventions) which has been suggested to be more suited to educating those who are categorised as special educational needs and disabled and may be more effective at reducing the number of young people not in education, employment, or training (Coalter et al., Citation2020).

The physical, mental, and social health benefits of sport and exercise are well evidenced for most if not all young people (Warburton & Bredin, Citation2019). However, the health benefits accrued through sport and exercise could be more pertinent for excluded pupils, compared to their peers in mainstream education, given the potential for wider developmental benefits including imparting life skills, behavioural management, psychosocial development and creating previously unavailable life opportunities by helping to foster better academic attainment, attendance and in class behaviour (Armour & Sandford, Citation2013; Bailey et al., Citation2009). For many years, policy makers, non-governmental organisations, sports clubs, education groups such as academy trusts, and private stakeholders have attempted to implement sport and exercise-based interventions (McCluskey et al., Citation2019; Valdebenito et al., Citation2018). However, research focusing on underpinning programme theory (a description of an intervention’s inputs, activities, outputs and preferred outcomes) and intervention mechanisms is severely lacking in alternative provisions (Brinkley et al., Citation2022; Gill et al., Citation2017).

Sport and exercise-based interventions present as an innovative means of addressing the challenges faced by pupils in alternative provisions and can be a particularly powerful vehicle for change (Brinkley et al., Citation2022). For instance, sport can be used with supplementary pedagogical strategies such as mentorship, citizenship, and personal and social development known as sport-plus interventions (i.e. sport-based positive youth development programmes) (Quarmby et al., Citation2022). Studies in this area have shown varying levels of effectiveness. For instance, football sessions in alternative provisions saw pupils increase their levels of engagement and on task behaviour, while surfing improved levels of connectedness with peers, staff and the environment, and badminton and tchoukball saw a general improvement in health-related quality of life in pupils aged 14–16 years (Cullen & Monroe, Citation2010; Hignett et al., Citation2018; Horner, Citation2019). However, there are notable limitations in the evidence, more specifically the sparsity of peer-reviewed research and use of grey literature. Grey literature often provides little insight into the complex causal explanations that may underpin an intervention’s successors or mechanisms of change (Brown et al., Citation2016; Leone & Pesce, Citation2017).

Intervention studies are often not robustly evaluated in line with the Medical Research Council guidelines (Brinkley et al., Citation2022; Valdebenito et al., Citation2018). This lack of information regarding the what, how, and for whom of interventions serves to slow progress on the development and implementation of new and successful sport and exercise-based interventions aimed at young people in alternative provisions (Skivington et al., Citation2021). Moreover, the PARIHS (Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services) framework outlines the importance of understanding the context in which an intervention will take place (Bergström et al., Citation2020). By understanding where and for who the intervention will occur for, development teams should be able to create an implementation strategy that is more suited to the target population; therefore, creating an intervention that has higher chances of success.

A realist approach forms the foundations of the design, evaluation, and implementation of complex interventions aiming to seek what works, how, where and for whom (Pawson et al., Citation2005). Unlike meta-analytic techniques, a realist methodology’s approach to data identification allows for the exploration of relationships between the specific context (e.g. geographical location), mechanisms (e.g. surfing sessions), and outcomes (e.g. better academic attainment) of an intervention. Moreover, a realist approach can develop potential explanations for what has been found within the literature and create theories – known as transferable theories (see Merton, Citation1967)– which can be transferred to inform programme implementation in differing environments (Marchal et al., Citation2012).

Research objective

The purpose of this realist review is to identify in what context and how, sport and exercise-based interventions for excluded pupils in alternative provisions can be successful and to provide recommendations on considerations for how to best develop current or new interventions. The notion of successful will be kept as broad as possible due to the uniqueness that surrounds APs and their differing perceptions of success. Success will be informed through stakeholder’s opinions and experiences.

Methodology

Design

The realist review was underpinned by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018), and the Realist And MEta- narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (Wong et al., Citation2013). This review was also conducted under the recommendations of Hunter et al. (Hunter et al., Citation2021) and stakeholder conversations. This review was registered on the Open Science Framework (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/ZX2A8) for transparency.

Ethical clearance was obtained from Loughborough University’s Ethics Committee (reference number:2022-7793-8390). The findings of this review will be presented in verbal and written feedback for policymakers and stakeholders consistent with Hunter and colleagues’ guide to conducting realist reviews. In the findings section, recommendations have been outlined. The recommendations include advice for the development and implementation of sport and exercise-based interventions that utilise concepts outlined within the Context Mechanism Outcomes (CMOs).

Hunter and colleagues produced a guide to conducting a realist review, which includes six steps. The first step is to (i) identify the review question involving understanding the surrounding literature and the creation of initial rough programme theories. The following steps are, (ii) search for primary studies using database, grey literature and reference list searching, known as forward and backward chaining, (iii) appraisal and selection; the relevance and rigour of the literature is assessed, (iv) data extraction, (v) data synthesis, (vi) the dissemination of findings.

Study selection, eligibility, and information sources

To be included in this realist review, the data must have met the following inclusion criteria: data must have been sourced from peer reviewed or reputable grey sources of literature presented in a written or visual format. Due to the limited amount of research, data was also included from relevant research conducted outside of alternative provisions (e.g. mainstream education settings). However, the data must have included a sample of suspended or permanently excluded young people, or marginalised youths, or at-risk children, or disaffected young people. All young people included must have been of primary or secondary school age (age 4–18 years). Retrieved evidence needed to include an outcome relating to health, education, society, employability, or economics, or an explanation of an intervention’s design, implementation strategy, or evaluation. Finally, literature must have been in English to be considered and based in the UK due to the complexity and uniqueness of the alternative provision system.

Stakeholder engagement

A total of 14 stakeholders were consulted during the review. All stakeholders were consulted at least twice for a variety of reasons, including developing the CMOs by providing insight on whether they would realistically work. Stakeholders were consulted to refine the search terms and CMOs following reiterations. One stakeholder was spoken to in a more formal semi-structured interview with a transcription of the consultation being made. This created data used to inform a CMO produced, based on the first consultation. Consultations were often informal conversations with minimal, if any, notes being made. They ranged from ten to ninety minutes depending on the setting and schedule of the stakeholder. For example, at a conference, conversations were often informal, sporadic, and restarted at multiple points throughout the day. Whereas another consultation occurred via Teams whilst the stakeholder was travelling lasting one hour. Stakeholders were typically members of staff within an alternative provision setting, local policy makers and non-government organisation employees, special educational needs coordinators, speech and language therapists (including assistants), and social emotional mental health needs mentors.

Step 1: define the scope of the review

Step one mapped the surroundings of the use of sport and exercise-based interventions in alternative provisions. Key concepts were identified during the familiarisation process (e.g. belongingness and positive youth development) which underpinned some of the CMOs created. Stakeholder consultations supplemented the search by providing advice and credibility checks on what interventions are currently used in alternative provisions, how sport is perceived, and which key contextual factors may determine the success or failure of future interventions. The initial rough programme theories were derived of inferences based on theory-backed explanations (e.g. Self Determination theory (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005)). Moreover, the initial rough programme theories were used to build hypothetical models, which were then tested in step two (Hunter et al., Citation2021).

Step 2: search for relevant evidence

Key search terms and phrases were identified from pre-existing research. Stakeholder conversations helped to shape the direction of the literature search terms by providing insight into what has previously been conducted and areas of research that they had been involved in. Search terms were kept broad to allow for a complete saturation of the literature regarding sport and exercise-based interventions for pupils in alternative provisions. By using a broad search, and because of the paucity of existing evidence, literature was extracted from other areas such as mainstream schools and other forms of interventions such as mentoring. Peer reviewed and grey literature were identified using the following search engines and databases: EBSCO, PsychARTICLES, PubMed, SPORTDiscuss, EMBASE, Web of Science and Google Scholar. Google Scholar and Google search were used to identify grey literature through Publish or Perish software. The following search terms and phrases were used through a series of combinations. These include (alternative provision OR provision OR AP OR PRU OR pupil referral unit OR free school OR special school OR specialist school OR forest school) AND (sport OR exercise OR physical activity OR fitness OR novel OR novice) AND (mentorship OR mentor OR therapy OR behaviour OR development OR natural environment OR new skill) AND (intervention OR trial OR study OR evaluation OR programme OR randomised OR scheme OR opportunity) AND (health OR quality of life OR function OR education OR grade) AND (marginalised OR young people OR pupil OR exclusion OR at-risk OR excluded OR expulsion OR rural OR economic) AND (deprivation OR socio economic status). The (*) was used to generate additional wildcard searches. Reference lists of included forms of evidence were also hand-searched. Index searches (i.e. searches for paper citing an included paper) and sibling-searches (i.e. related paper to included evidence conducted by the same author/research team - protocols, pilots, feasibility studies) were conducted using backward chaining.

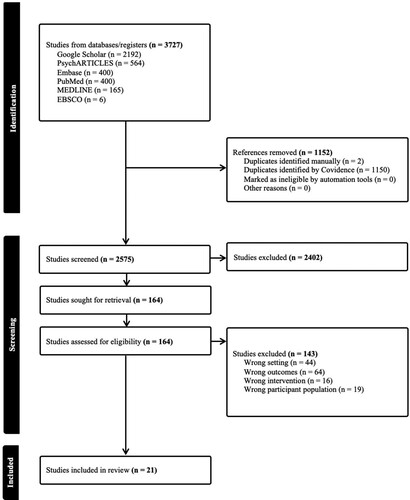

From the initial informal literature mapping, sources of data were identified and used for the construction of the CMOs. One expert statement from a member of an Active Partnership (a network that brings people and organisations together to increase physical activity levels) was collected and used to help develop the CMOs. The formal literature search was conducted to find supporting evidence for the CMOs. The search criteria resulted in 3727 pieces of literature, which were imported into Covidence (a screening and extraction tool designed for Cochrane authors) for data screening. 1152 sources of evidence were removed due to duplication. This resulted in 2575 potentially eligible pieces of literature. The main author conducted title screening. 2402 studies were removed during this process for irrelevance (e.g. outside of education and/or not involving young people). 173 full text pieces of literature were assessed for eligibility. Subsequently, 151 studies did not meet inclusion criteria for displayed reasons in . Thus, leaving 21 pieces of literature for inclusion in the final realist review. From this, forward and backward chaining and independent searching was completed, highlighting a further 65 pieces of relevant literature.

Step 3: study quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was conducted for the eligible pieces of literature. A standard quality appraisal checklist used in systematic literature reviews is not applicable for a realist review because it does not include a hierarchical approach to data sourcing (e.g. a randomised control trial hailed as the gold standard of study methodology) (Hunter et al., Citation2021). Drawing upon research conducted by Dada and colleagues, the quality appraisal process refers to prioritising relevance, richness, and rigour within each item of literature (Dada et al., Citation2023). A piece of literature can be deemed relevant if it helps to refine, refute, or substantiate programme theory. Rigour refers to whether the literature contains data that is credible and trustworthy. The richness of a piece of literature refers to its ability to explain how an intervention could work through providing conceptual richness or contextual thickness. Dada et al also outlined ways in which relevance, rigour and richness could be assessed. This was used by the authors to develop a process of systematic decision-making concerning what data to include. The process included the following: all sources of data were marked on a scale of one to four (one being least relevant and rigorous and four being highly relevant and rigorous). A source of data can be considered rigorous if it: (i) is derived from a reputable source (e.g. a government report, a piece of scientific literature or an NGO evaluation report); (ii) has a clearly stated research question; (iii) has transparent explanations of methodology including data collection methods; (iv) has robust and unbiased design; (v) considers researcher reflexivity; and (vi) has transparent reporting of findings. Data can be deemed to have good relevance if it: (i) comes from a peer reviewed source; (ii) includes the target population; (iii) includes a sport and exercise-based intervention; (iv) is situated in the target location and/or setting; (v) its theoretical underpinnings are provided; (vi) its contextual factors are outlined; (vii) its intervention mechanisms are provided; (viii) it has detailed findings; and (ix) its outcome analysis and explanations are provided. The rating scale point allocation is outlined in and below for relevance, richness, and rigour. Additionally, see and C1 for worked examples of how relevance, richness, and rigour was assessed for each source of data. Due to the sparsity of literature in the field of sport and exercise interventions in alternative provisions, all data that was scrutinised was deemed to be relevant, rich and rigorous. Hence, no evidence was excluded during the scrutiny process informed by Dada and colleagues. Conducting this process ensured the data included to form the CMOs was robust which in turn helped to promote the transparency and credibility of this review. Finally, typically those who scored higher during the scrutiny process informed the CMOs more so than the ones that did not. For example, the Hignett et al evaluation of a surfing intervention helped to inform multiple of the CMOs created.

Table 1. The Relevance, Richness, Grading System.

Table 2. The Rigour Grading System.

Step 4: data extraction

The data extraction process was completed for the 87 pieces of literature. A coding guide was created using unique highlighter colours. Relevant data was extracted and grouped into clusters of similar topics. These topics were: (i) contextual factors (including socioeconomic status and ethnicity etc.), (ii) mechanics of a programme theory yellow (including programme intervention strategy and resources), and (iii) outcomes (e.g. improved physical fitness and improved mental toughness). When identified, cited theories in the interventions were noted to provide added understanding for the mechanisms of the intervention.

Step 5: data synthesis

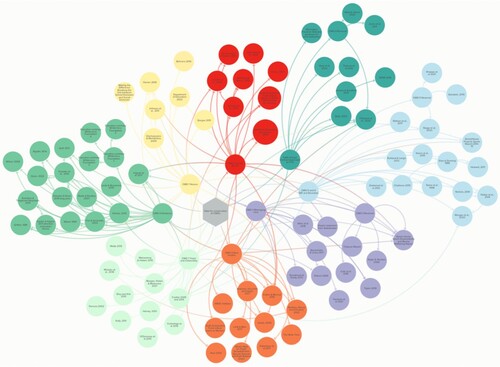

The extracted data were arranged into clusters to support the appropriate hypothetical CMOs. The data were used to refine the CMOs to reflect the evidence that had been identified. If then because statements were created for visual clarity to make dissemination as efficient as possible. In the case of the current study and to ensure clear translation to a melange of stakeholders, including children, these terms are consciously made bold and italicised. A map was created using KUMU.io allowing for the visual representation of which pieces of data were used to create which CMOs. Each node represents one piece of literature and when interacted with, provides the relevant information including reference, relevance and rigour score, and where it was sourced (e.g. backward chained) See link (https://embed.kumu.io/ebb6b1ceaebfd842d02622ed9c520707). is a screenshot of the KUMU CMO creation map.

Step 6: literature derived programme theories

A list of initial rough programme theories was created using the data. The CMOs were designed to explore how sport and exercise-based interventions can be used for pupils in alternative provisions. Data extracted in Steps four and Step five were used to provide a rich and thick evidential backing to the theoretical CMO configurations.

Results

Description of studies

Twenty-two sources of data were intervention evaluation papers, 47 were descriptive studies, and the remaining 18 data sources were grey literature. The grey literature included PhD and MSc dissertations (n = 2) (PhD theses often not having gone through peer-reviewed process but available through university repositories), online website articles (n = 4), government reports (n = 3), NGO programme evaluation papers (n = 8), and an interview conducted with a field expert (n = 1). Over three quarters of the included data sources were published from 2011 onwards (n = 57), whilst 24 papers were published between 2000 and 2010, and 6 sources were published prior to 2000. Twenty-one sources of data were directly identified through the systematic literature search. From this, a further 65 data sources were identified through forward and backward chaining. This totals 87 individual pieces of literature included in this review.

Literature derived programme theory

The data provided the appropriate content to produce nine initial rough programme theories including two rival theories. A rival programme theory is a statement that follows the same structure as the initial rough programme theory, however, it describes an opposite or different response, and consequently a different outcome due to a change in context or mechanism. The role of a rival theory is to reinforce the interactions between the context, mechanism and outcome of a CMO configuration (Pawson et al., Citation2005).

The CMOs from each source were synthesised to identify explorative insights into sport and exercise-based interventions for young people in alternative provisions. The initial rough programme theories focused on the impact the interventions could have on pupils’ mental and social health and academic attainment and attendance. The initial programme theories were also underpinned with middle-range theory focusing on psychological and sociological theories. outlines the nine initial rough programme theories and two rival theories. The CMOs have been given ‘lay titles’ as this paper seeks to make recommendations that are comprehensible and interesting to a range of stakeholders including young people and those not in science nor academia. In the following findings section, the CMOs are presented followed by the relevant discussion.

Findings

CMO 1 – treat pupils with kindness (Mentors taking a pupil centred approach to teaching)

If pupils in alternative provisions with complex needs, participate in sport-plus interventions that include mentors who take a pupil-centred approach. Then the pupil will feel their complex needs are being supported. Because the mentor creates a supportive environment by understanding and meeting the complex needs of the pupils, allowing them to feel heard, related to, autonomous and competent. And facilitates the successful engagement with the elements of positive youth development.

CMO 1 – treat pupils with kindness discussion

Mainstream schooling is often not well placed to meet the needs of pupils who are subsequently excluded and transferred to alternative provisions (Cole et al., Citation2019). These needs can be complex, and when they are not met, there can be a detrimental impact on pupils’ perceptions of education, including that in alternative provisions (Mills & Thomson, Citation2018; Trotman et al., Citation2019). Pupils in alternative provisions need to feel safe, secure, confident, valued, and supported to have positive experiences in educational contexts (Department for Education, Citation2018; Department of Education, Citation2022). Sport-plus interventions have been successful in improving pupils’ academic engagement and attendance (Sandford et al., Citation2013). However, an intervention can only be successful if the participants engage with its core concepts (Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). Tidmarsh and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the use of positive youth development with disadvantaged young people (Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). They found that a main barrier to positive youth development engagement was lack of appeal due to the sessions feeling like school. Sport-plus overcomes this barrier and aids the mobilisation of positive youth development principles as they provide a fun and stimulating environment. Additionally, mentors are frequently used to deliver sport in alternative provisions. When a mentor adopts a pupil-centred approach, engagement with sport-plus interventions is improved. Tidmarsh et al found that understanding and meeting the complex needs of pupils was an enabler to engagement with the interventions (Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). These align with the core concepts of a pupil-centred approach. A pupil-centred approach seeks to fulfil the needs of the pupil and there are four main characteristics: (i) voice, (ii) choice, (iii) competency-based progression, and (iv) continuous monitoring of the pupil’s needs (Gray et al., Citation2022). Therefore, sport and exercise-based interventions that use a positive youth development approach with mentors who adopt a pupil-centred approach pose a credible option for improving pupils’ engagement with sport. The importance of the mentors is often underrepresented within literature. Tidmarsh and colleagues found significant evidence showing when staff did not adopt a pupil-centred approach, the pupils did not engage with the positive youth development intervention (Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). This is because their complex needs were not being supported leading to exaggerated feelings of instability, distrust with staff, disconnection from the community and disengagement from education. A major positive youth development resource is the social context the pupil lives in, including family, school, and community (Jones et al., Citation2011; Waid & Uhrich, Citation2020). Pupils in alternative provisions are more likely to experience unstable family relations, have poorer relationships with school staff and could be more disconnected from society in general (Department for Education, Citation2019; Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). Therefore, it is important to highlight the role that the mentor plays regarding the successful implementation of the sport-plus intervention.

CMO 2 – real models not role models (Mentors having relatable shared lived experiences)

If pupils who lack authentic and present role models participate in sport and exercise-based interventions that utilise mentors with shared lived experiences. Then the pupils will develop improved aspiration and enhanced effort towards pro-social identity. Because the mentors act as passive role models setting a good example, aiding pupils’ development, and are present and tangible when compared to celebrity role models. And this means pupils feel connected to the mentors and have a sense of admiration for the mentor.

CMO 2 – real models not role models discussion

Evidence suggests that pupils in alternative provisions often lack academic role models due to previous negative experiences within mainstream school settings (Houtepen et al., Citation2020; Sanders et al., Citation2018). Moreover, pupils often feel isolated and disconnected because of the negative stereotyping within the community, which can limit hope and aspiration (Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). Mentors with shared lived experiences form a vital mechanical feature of this sport and exercise-based intervention configuration (Gaffney et al., Citation2022a; Reid, Citation2002). The mentors act as a passive role model, setting a good example for pupils, and helping pupils to develop a different outlook (Blum & Joan, Citation2021; Cullen & Monroe, Citation2010). This is likely more influential than a typical role model –such as a famous actor or football player– as they are tangible and present in the pupil’s life (Gaffney et al., Citation2022b). Therefore, acting as ‘real models’ and not role models. Research from breast cancer patients found that when provided with tangible supports in the form of role models, the patients’ experience of breast cancer was significantly improved (Hirschman & Bourjolly, Citation2005). By having a ‘real model’, pupils often develop a greater sense of admiration and effort towards their pro-social identity (Lindt & Blair, Citation2017; Shade, Citation2006). Pro-social identity refers to having the motivation and willingness to seek out and make good the opportunities provided (Na & Paternoster, Citation2018). A real model with shared lived experiences improves the acceptability of having a mentor with at-risk youths and therefore increases the chances of having a beneficial outcome (Gaffney et al., Citation2022a). From this, pupils may develop better relationships with school staff and therefore improve school attendance, academic engagement, and community participation (Reid, Citation2002).

CMO 3 – this is new! (Novice sports in a novice environment)

If pupils in alternative provisions participate in novice sports that are regarded as societally cool (e.g. surfing) in a novice group setting that is free from judgement. Then they may develop improved self-confidence and quality of motivation. Because the novice element creates a ‘level playing field’ between the pupils and staff creating an equal risk of failure. And their basic psychological needs are being supported.

CMO 3 – this is new! discussion

Research indicates pupils in alternative provisions may experience fear of failure linked to an absence of confidence when decision making (Hignett et al., Citation2018). Additionally, pupils in alternative provisions have cited feelings of isolation due to the disconnection from wider society (Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). Literature suggests the risk of failure may not negatively impact pupils’ willingness to participate in a novice sport when this is new, and they are participating together (Hignett et al., Citation2018). Through novice sports, pupils can achieve a greater sense of skill mastery by learning the new skills required to participate hence, developing a sense of competence (Hignett et al., Citation2018; Johnson et al., Citation2011). By participating with peers with similar complex needs and experiences, a sense of relatedness can be developed. Facilitating the basic psychological needs of pupils could produce significant improvements to aspects of their mental health (Sylvester et al., Citation2012). In addition, typically pupils in alternative provisions suffer from poorer mental health than their peers in mainstream education (Ford et al., Citation2018; Martin-Denham, Citation2020). Therefore, a sport and exercise-based intervention designed in this configuration could be of use to promote better self-perception, confidence, and motivation through supporting relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Hignett et al., Citation2018).

CMO 4 – friends are important (The importance of social bonds and vicarious learning)

If pupils in alternative provisions excluded from mainstream education participate in structured team sports that facilitate peer interactions and the formation of social bonds. Then the pupils will develop a sense of connectedness. Because team sports provide an opportunity for interactions with peers by playing with and against them allowing for close and strong bonds to be formed. And young people can then learn new behaviours and beliefs (including pro-social behaviours) through interactions and bonds made with peers.

CMO 4 – friends are important discussion

Pupils in alternative provisions are more likely to engage in health risk behaviours such as alcohol and drug abuse, and sexual risk taking (Farrall et al., Citation2020; Ireland, Citation2019). The Social Bonds theory assumes that humans, in particular adolescents, have tendency to engage in delinquent behaviours (Chriss, Citation2016). The theory suggests that social bonds between humans can prevent these behaviours through conformity to social appropriateness. The stronger the attachment of the bond between people, the more of an effect there will be on behaviour (Chriss, Citation2016). A reduction in health risk behaviours has been linked to the influence of peers created through closeness and camaraderie (Gremmen et al., Citation2019; McMillan et al., Citation2018). Team sport facilitates an environment of interaction between peers and can help to develop feelings of camaraderie (McEwan & Beauchamp, Citation2014). Thus, through structured team sport setting such as organised training sessions or games, new social bonds can be developed amongst pupils attending alternative provisions which will develop feelings of camaraderie and closeness and therefore may lead to an increase in pro-social behaviours, a reduction in health risk behaviours and improvements in social health.

CMO 5 – there’s no I in team (Opportunities to represent the school in a judgement free, skill-based environment)

If pupils, who are not typically chosen to represent their school, participate in sports that use skill-based matchmaking. Then the pupils will develop greater feelings of self-worth and quality of motivation towards the behaviour (i.e. sport participation). Because being given the opportunity to wear school team kit and represent the school will elicit feelings of pride and belongingness and have them feeling like a valued member of their school community. And this could lead to an improvement in pupils’ academic engagement.

CMO 5 – there’s no I in team discussion

Pupils – in all education settings (e.g. mainstream education, alternative provisions, etc.) – who possess a low level of sport competency are often not selected to represent their schools in competitions which can result in disaffection. This is perhaps further compounded for pupils within alternative provisions who can be marginalised and may feel that they do not belong, and are not accepted, by society at large (Tidmarsh et al., Citation2022). An active trust based in the East of England developed a sports festival to promote the involvement of all pupils in sport. The festival highlighted a non-competitive agenda and focused on skill-based matchmaking between teams. By using games with a matched skill level between teams, pupils often not selected for teams were given the chance to represent their school, promoting feelings of belongingness and pride whilst limiting the impact of negative achievement emotions such as embarrassment and fear of failure. Limiting negative achievement emotions can also promote greater feelings of pride (Elliot et al., Citation2011). The impact of negative achievement emotions was further limited by creating a non-competitive and inclusive environment by focusing on the wording surrounding sport. For example, terms often linked with competitiveness such as football ‘tournament’, and football match ‘against’ X team were replaced with football festival and football games with X team (Whitehead, Citation2002). Baumeister and Leary suggest that the need for belongingness is a fundamental element of human motivation (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). By facilitating the feelings of belongingness and pride, pupils’ feelings of self-worth will be supported. Supporting the feelings of self-worth will positively impact their mental health, academic engagement, and attendance (Pardede et al., Citation2021). Literature suggests pupils may feel more inclined to attend school when they feel like a valued member of the school community (Goodenow & Grady, Citation2010).

CMO 5 rival theory – there’s no I in team

However, if pupils who are not typically chosen to represent the school participate in sports that use skill-based matchmaking. Then this may exaggerate feelings of psychological distress, which could further decrease their engagement in education. Because pupils may experience an increased vulnerability to fear of failure and the negative outcome emotions linked to this, such as shame.

CMO 5 rival theory – there’s no I in team discussion

Research highlights, pupils in alternative provisions are more likely to be exposed to psychological distress such as anxiety and poor self-perception (Cole et al., Citation2019; Department of Education, Citation2022). If pupils who are susceptible to these feelings are asked to represent their school in a sport festival, this may elicit negative outcome emotions such as fear of failure and embarrassment (Sagar & Stoeber, Citation2009). This could have a consequential impact on their feelings of self-perception and quality of motivation, resulting in poorer attendance and engagement with learning (Baumann & Krskova, Citation2016).

CMO 6 – quest completed (Utilising physically active lessons)

If pupils in alternative provisions participate in more sport and exercise throughout the school day alongside their learning, such as Physically Active Lessons. Then their desire for excitement may be fulfilled and thus, preventing boredom. Because the physical activity provides a source of organised stimulation and excitement. And boredom results from a paucity of stimulating activities, which is a known cause of in-class disruptive behaviours, one of the main factors for school exclusion.

CMO 6 – quest completed discussion

Children actively seek excitement throughout the day. Boredom causes disruptive behaviour in class, which is a key factor in school exclusion (Gerlinger et al., Citation2021). Boredom typically results from a paucity of stimulating activities (Xie, Citation2021). This is particularly notable in the classroom. The quest for excitement hypothesis suggests that seeking excitement is a powerful motivation for human behaviour. It is particularly noted as a key motivator for antisocial behaviour such as disruptive in-class actions (Dunning & Elias, Citation1986). If pupils participate in more sport and exercise during the school day, they are less likely to engage in disruptive behaviours (Skage et al., Citation2020). This occurs because the pupil’s desire for excitement is fulfilled through appropriate stimulation (Dunning & Elias, Citation1986). A successful example of this is physically active lessons. Physically active lessons can improve pupils’ physical activity levels and academic-related outcomes, such as engagement with learning, attainment, and cognitive functioning (Norris et al., Citation2015; Watson et al., Citation2017). Physically active lessons combines typical academic content with short burst of physical activity which can provide sufficient stimulation to keep a pupil’s attention focused and behaviour positive (Ruhland & Lange, Citation2021). Therefore, if pupils were to participate in more physically active lessons during the school day, they may feel sufficiently stimulated, thus reducing in class disruptive outbursts which may improve academic attainment and engagement for pupils and their peers.

CMO 6 rival theory – quest completed

If pupils in alternative provisions participate in more exercise throughout the school day alongside their learning, such as physically active lessons. Then they may cause more disruption in class. Because the participation in activity in class during the day could cause the pupils to become overly aroused. And this can have detrimental consequences for both peers and teaching staff.

CMO 6 rival theory – quest completed discussion

The Yerkes-Dodson law of arousal suggests there is an optimal level for arousal (Khazaei et al., Citation2021). Becoming over aroused can have detrimental performance consequences. In education, this can lead to a loss of attention, distracting behaviour, acting upon sudden urges and general excitability (Khazaei et al., Citation2021). By introducing physically active lessons to pupils in alternative provisions, there is a chance this could cause over arousal, subsequently worsening in class disruptive behaviours, similar to what is displayed through classroom boredom. As stated, implementation of physically active lessons can be considered successful when the level of academic content delivered is the same amount as when physically active lessons is not used. Therefore, if physically active lessons reduces this due to the over arousal of the students, implementation can be considered unsuccessful (Skage et al., Citation2020). It is important to consider the context in which physically active lessons are delivered, as a significant majority of pupils in alternative provisions have additional learning needs and therefore may be more susceptible to over arousal (Department of Education, Citation2022).

CMO 7 – the great outdoors (Attention restoration theory in practice)

If pupils in alternative provisions excluded from mainstream education are exposed to the natural environment whilst participating in sport and exercise. Then the pupil will experience greater feelings of calmness and relaxation, enhancing focus and mental fatigue recovery. Because green spaces possess attention restorative features. And may help improve pupils’ focus and engagement in the classroom.

CMO 7 – the great outdoors discussion

A significant portion of teaching time is based indoors as curriculums often do not include outdoor environments, typically due to a lack of facilities. In alternative provisions, this is more prevalent due to poor access to facilitates, particularly in relation to sport provision (The Difference, Citation2016). The attention restoration theory suggests exposure to green and blue spaces is beneficial to one’s physical, mental, and social health (Basu et al., Citation2019). Attention restoration theory proposes exposure to these spaces encourages more effortless brain function, allowing for the recovery and replenishment of directed attention capacity. To qualify as a successful green space supported by attention restoration theory, Kaplan (Basu et al., Citation2019) suggests the environment must create a sense of immersion, provide an escape from the normal environment of the person, include aspects that captures one’s attention effortlessly, and be a space where one wants to be and appreciates being in. By participating in sport and exercise in an outdoor environment, pupils should feel a sense of calmness and relaxation which has been found to positively impact their academic attainment and attention (Fox & Avramidis, Citation2003; Knowler et al., Citation2019). Therefore, if pupils in alternative provisions participated in more sport and exercise outside, in natural environments, their engagement within the classroom may improve through having greater capacity to focus and pay attention to the lesson (Deepa et al., Citation2022).

Moreover, further research suggests that gardening, as a source of exercise, offers enhanced psychological benefits on top of the existing ones proposed by attention restoration theory (Davis, Citation2022). Sharpe conducted an evaluation of a gardening intervention based in mainstream schools for at-risk youths (Sharpe, Citation2014). The evaluation found that through the process of planting and growing fruit and vegetables, pupils developed a sense of responsibility and excitement. Upon harvest, pupils experienced a sense of relief that they had successfully nurtured the crops. Sharpe concluded that gardening for at-risk youths led to improvements in aspiration, self-confidence, and sense of responsibility. Research further supports the use of gardening to foster feelings of responsibility, pride and fulfilment in at risk youths (Leutz & Beaumont, Citation2019; Skelly & Campbell Bradley, Citation2007).

CMO 8 – yawn (The boredom theory and impulsive behaviour)

If pupils in alternative provisions participate in organised sport sessions during lunch breaks and after school. Then pupils will be less likely to engage in impulse-linked behaviours such as aggression and violence. Because sport acts as a prevention to boredom. And participating in extra curriculum sports can take away from leisure time that could be used to engage in violence.

CMO 8 – yawn discussion

Engagement in violent behaviour in school is a key contributing factor to school exclusion (The School run, Citation2022). Boredom can cause impulsivity, which may lead to detrimental behaviours such as violence and aggression, often seen in alternative provisions (House of Commons, Citation2018). When pupils in alternative provisions participate in organised sport and exercise sessions during and after school hours, the boredom theory suggests they will be less likely to engage in impulsive behaviours such as violent outbursts and abuse towards peers and staff (Eastwood et al., Citation2012). This is because boredom is prevented for the pupils due to the engagement within the sport sessions. Therefore, if pupils participate in more sport sessions during and after school, they will be less likely to engage in anti-social behaviours (Xie, Citation2021).

CMO 9 – thinking positive thoughts (The promotion of citizenship through sport)

If pupils in alternative provisions participate in programmes that utilise sport and exercise as a vehicle to develop qualities associated with citizenship. Then the pupils may develop a sense of hope and achievement. Because using outcome-related activities facilitates the belief of attaining sport-related goals. And this may translate into promoting pro-social behaviours linked with citizenship.

CMO 9 – thinking positive thoughts discussion

Pupils in alternative provisions may have more challenging and complex life circumstances, which can limit their sense of hope (Morgan et al., Citation2021). Literature suggests that sport can be used as a vehicle to develop qualities associated with citizenship (e.g. accountability, responsibility, respect) (Harvey, Citation2001). Moreover, sport can provide an alternative vision of social welfare with the potential for improving ambition (Eley & Kirk, Citation2010; Kelly, Citation2011). Thus, developing a sense of ambition and hope. Research shows that sport and exercise-based interventions can be used to aid young people in developing human, social and psychological capital (Morgan et al., Citation2019). Hope is considered as a vital element of psychological capital (Morgan et al., Citation2021). Coalter states sport can play a pivotal role in promoting hope within those who participate whilst providing a foundation for positive transition into adulthood (Coalter, Citation2013). By participating in outcome-related activities, such as creating attainable skill mastery goals, sport can foster a sense of hope (Kelly, Citation2011). Therefore, by promoting hope and citizenship through sport, pupils will be more likely to have a positive outlook on their futures. This can potentially increase their participation in pro-social behaviours such as improving their academic attainment and attendance through an enhanced sense of accountability, justice, and respect (Harvey, Citation2001; O’Donovan et al., Citation2010; Parker et al., Citation2017).

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

When using sport-plus programmes, intervention developers and implementors should aim to use mentors that take a pupil-centred approach during sport sessions. The sport sessions should be underpinned by positive youth development. Mentors should be trained to effectively support the complex needs of the pupils. The training should cover the four main concepts of a pupil-centred approach. Sport is an effective method to promote positive youth development and therefore sport and exercise should be fun, engaging and interactive. Moreover, the importance of being a ‘real model’ should be promoted. When using mentors, developers should actively seek individuals with shared lived experiences to those they will be mentoring.

Recommendation 2

When designing a sport and exercise-based intervention, developers should aim to create a novice environment to reduce the risk of failure and increase a sense of relatedness through a level playing field. The sport and exercise should be novel to all pupils and, if possible, the teachers. Intervention developers should aim to create an environment that supports the basic psychological needs of the pupils. This can be achieved by (i) focusing on facilitating learning new or developing current skills (e.g. learning novel sports), (ii) creating judgement free environments allowing for interactions between pupils of similar abilities (e.g. creating a novel environment), and (iii) allowing for decision making to be made by the pupils regarding participation (e.g. providing them with the choice to participate in a non-judgemental environment). Supporting the basic psychological needs of the pupils will aid their willingness to participate in the intervention and therefore should improve the chances of success.

Recommendation 3

When developing a sport and exercise-based intervention, implementors should consider the importance of interactions between the pupils attending. The intervention should facilitate the development of strong and close social bonds between the pupils, which can be created through team sport games and training sessions. Learning and developing sport skills is a significant method for facilitating bond formation. Additionally, communication focused tasks can positively influence the interactions between pupils.

Recommendation 4

Sport and exercise-based interventions should aim to foster pupils’ feelings of belongingness within their school. A successful method that achieves this is creating an environment where pupils of similar sport competency can play against each other and be provided the opportunity to represent their school. Feelings of belongingness can be further enhanced through the provision of school team kit (Baumann & Krskova, Citation2016). Additionally, it is important for developers to highlight the non-competitive element to limit the potential impact of negative outcome emotions pertaining to the sport performance of pupils. An effective method to allow pupils to enjoy sport in a non-competitive manner is to remove the language typically associated with competitive sport such as replacing sport tournament with sport festival and football matches with football games.

Recommendation 5

Alternative provisions could facilitate short bursts of sport and exercise throughout the school day – potentially through physically active lessons – to reduce disruptive behaviour and to keep pupils engaged. The short bursts of sport and exercise should consist of around 10-minute stints (see Vetter et al., Citation2020). Research highlights the activity should have an academic focus reinforcing what had previously been learnt in class. The short bursts could include dancing whilst reciting times tables or star jumps whilst spelling a word aloud (Skage et al., Citation2020). Conversation with teachers is highly recommended so the objectives of using physically active lessons are aligned and the teachers are confident to run the sessions.

Recommendation 6

If facilities and resources permit, alternative provisions should aim to organise sport sessions to be run outside in green or blue spaces, exposing pupils to the natural environment. Additionally, alternative provisions could create dedicated plots to allow pupils to exercise through engaging in gardening. Developers should aim to create spaces that support the requirements outlined by Kaplan and Kaplan (Basu et al., Citation2019).

Recommendation 7

Intervention developers should work with alternative provisions to create organised sport sessions during the school day. These will typically be at lunch, during physical education lessons, and afterschool, offering fun opportunities for skills to be learnt and developed. With reference to the boredom theory, to enhance engagement and enjoyment, a variety of sports should be offered. Pupils should be consulted to determine their wants and needs to maximise engagement and enjoyment.

Recommendation 8

The Citizenship Education Review group suggest to successfully promote citizenship, sessions should be challenging, and relevant to the narrative of the pupil (Deakin-Crick, Citation2008). To promote citizenship through sport, intervention developers should tackle issues relevant to sport (e.g. fairness, the value of tolerance, respect and concern, and accountability) (O’Donovan et al., Citation2010). An example for promoting these traits is having the pupils take turns officiating games, highlighting the importance of following the rules.

Conclusion

Sport and exercise-based interventions represent a viable means of enhancing the physical, mental, and social health of pupils in alternative provisions. The interventions can influence pupils’ academic attainment, attendance, and relationships by promoting citizenship, improving self-perception, fostering belongingness and supporting pupils’ basic psychological needs. Finally, sport and exercise can provide an environment that facilitates positive mentor relationships, allows access to green spaces, provides a source of excitement and stimulation and acts a vehicle to instil the concepts of positive youth development. However, as outlined in the rival theories, there are circumstances where a change in intervention context or mechanism can result in a contrasting outcome. For example, a pupil with increased susceptibility to psychological distress can elicit negative outcome related emotions when representing their school, despite it being a non-competitive and non-judgemental environment.

However, all findings are underpinned with the fundamental need for space and resources. Stakeholder conversations highlighted the issue that most (if not all) alternative provisions have, a lack of resources and facilities for sport and exercise. This means sport and exercise-based interventions will not work in an alternative provision if the situation of space and facilities is not improved. Many alternative provisions are based in inner city buildings, often offices which have very little access to, for example, green spaces. It is of the utmost importance for policy makers and local councils to review provision of funds for facilities and resources for alternative provisions.

The PARIHS framework of implementation supported the recommendations made within this paper. It is essential to incorporate and understand the complex contextual factors that surround the target population of this paper when establishing the what, how and for whom, of sport and exercise-based interventions. We argue that this paper has achieved this. However, the findings from this paper are theoretical. This review is part of a three-phase project aiming to develop sport and exercise in alternative provisions. The future research will include conducting a realist enquiry utilising pupils and staff collaboration in alternative provisions to refine the findings of this review to create a theory of change. This theory of change will then be used to develop an intervention implementation plan that will undergo rigorous evaluation. This research will serve to contribute to producing evidence informed policy surrounding the use of sport and exercise interventions in alternative provisions, to enhance the experiences and outcomes for pupils.

Limitations

This paper includes limitations. The CMO configurations were based on available research in the area. However, the dearth of peer-reviewed literature resulted in the use of grey literature and expert opinion. These sources of data often lack detail rich synthesis of the theoretical underpinnings and methods used to develop and implement sport and exercise-based interventions. Therefore, at times, evidence was drawn upon from outside the field of sport and exercise-based interventions in alternative provisions, for example, sport and exercise-based interventions in mainstream education settings. However, all sources of data were evaluated for relevance, richness and rigour, and therefore, significance should not be taken away from the findings of this review. Moreover, future research should include research produced in alternative languages to ensure the appropriate representation of those from marginalised groups.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the stakeholders involved with this study, your expertise and knowledge were vital.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

All data used in this paper is available online, through the OSF weblink.

References

- Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 1–34.

- Andrews, W., Houchins, D., & Varjas, K. (2017). Student-directed check-in/check-out for students in alternative education settings. Teaching Exceptional Children, 49(6), 380–390.

- Armour, K., & Sandford, R. (2013). Positive youth development through an outdoor physical activity programme: Evidence from a four-year evaluation. Educational Review, 65(1), 85–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2011.648169

- Arnez, J., & Condry, R. (2021). Criminological perspectives on school exclusion and youth offending. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 26(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2021.1905233

- Bailey, R., Armour, K., Kirk, D., Jess, M., Pickup, I., & Sandford, R. (2009). The educational benefits claimed for physical education and school sport: An academic review. Research Papers in Education, 24(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520701809817

- Basu, A., Duvall, J., & Kaplan, R. (2019). Attention restoration theory: Exploring the role of soft fascination and mental bandwidth. Environment and Behaviour, 51(9–10), 1051–1081.

- Baumann, C., & Krskova, H. (2016). School discipline, school uniforms and academic performance. International Journal of Education Management, 30(6), 1003–1029.

- Baumeister, R., & Leary, M. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (2017). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Interpersonal development, 30, 57–89.

- Behrens, T. K., Schuna, J. M., Liebert, M. L., Davis, S. K., & Rice, K. R. (2016). Evaluation of an unstructured afterschool physical activity programme for disadvantaged youth. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(22), 2140–2144.

- Bergström, A., Ehrenberg, A., Eldh, A., Graham, I., Gustafsson, K., Harvey, G., Hunter, S., Kitson, A., Rycroft-Malone, J., & Wallin, L. (2020). The use of the PARIHS framework in implementation research and practice—a citation analysis of the literature. Implementation Science, 68(15), 1–51.

- Blum, A., & Joan, B. (2021). Evidence Review: Mentoring and Lived Experience Mentoring, 1–19.

- Blyth, E., & Milner, J. (2002). Exclusion from school: Multi-professional approaches to policy and practice. Routledge.

- Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 166–179.

- Brinkley, A., Sherar, L., & Kinnafick, F. (2022). A sports-based intervention for pupils excluded from mainstream education: A systems approach to intervention acceptability and feasibility. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 61, 102217.

- Brown, H. E., Atkin, A. J., Panter, J., Wong, G., Chinapaw, M. J. M., & van Sluijs, E. M. F. (2016). Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: A systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obesity Reviews, 17(4), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12362

- Burgon, H. L. (2011). ‘Queen of the world’: Experiences of ‘at-risk’ young people participating in equine-assisted learning/therapy. Journal of Social Work Practice, 25(2), 165–183.

- Challenor, J. (2015). An investigation into the impact of sport on the behaviour of young people who reside in an area of socioeconomic deprivation and attend a pupil referral unit with North Wales [Doctoral dissertation]. Cardiff Metropolitan University.

- Chriss, J. (2016). The functions of the social bond. The Sociological Quarterly, 48(4), 689–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2007.00097.x

- Chriss, J. J. (2007). The functions of the social bond. The Sociological Quarterly, 48, 689–712.

- Coalter, F. (2005). The social benefits of sport. SportScotland.

- Coalter, F. (2013). Sport For development. What game Are We playing? (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Coalter, F., Theeboom, M., & Truyens, J. (2020). Developing a programme theory for sport and employability programmes for NEETs. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(4), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1832136

- Cole, T., McCluskey, G., Daniels, H., Thompson, I., & Tawell, A. (2019). Factors associated with high and low levels of school exclusions: Comparing the English and wider UK experience. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(4), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2019.1628340

- Cullen, K., & Monroe, J. (2010). Using positive relationships to engage the disengaged: An educational psychologist-initiated project involving professional sports input to a pupil referral unit. Educational and Child Psychology, 27(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2010.27.1.64

- Cummings, C., Laing, K., Law, J., McLaughlin, J., Papps, I., Todd, L., & Woolner, P. (2012). Can changing aspirations and attitudes impact on educational attainment. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Dada, S., Dalkin, S., Gilmore, B., Hunter, R., & Mukumbang, F. (2023). Applying and reporting relevance, richness and rigour in realist evidence appraisals: Advancing key concepts in realist reviews. Research Synthesis Methods, 14(3), 504–514.

- Davis, K. (2022). The freedom to have fun, play, make friends, and Be a child: Findings from an ethnographic research study of learning outside in alternative provision. Contemporary Approaches to Outdoor Learning, 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85095-1_10

- Deakin-Crick, R. (2008). Pedagogy for citizenship. In F. Oser & W. Veugelers (Eds.), Getting involved (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 31–55). Brill.

- Deepa, V., Sujatha, R., & Baber, h. (2022). Moderating role of attention control in the relationship between academic distraction and performance. Higher Learning Research Communications, 12(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.2022.v12i1.1285

- Department for Education. (2018). Characteristics of young people who are long-term NEET.

- Department for Education. (2019). Timpson review of school exclusions. In 14-19 Learning and Skills Bulletin (Issue 297, p. 2).

- Department for Education. (2021a). Permanent exclusions and suspensions in England, Academic Year 2019/20 – Explore education statistics – GOV.UK. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/permanent-and-fixed-period-exclusions-in-england/2019-20

- Department for Education. (2021b). Schools, pupils and their characteristics, Academic year 2020/21 – Explore Education Statistics – GOV.UK. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics

- Department of Education. (2022). Department of Education Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2022.

- Dunning, E., & Elias, N. (1986). Quest for excitement. Sport and leisure in the civilizing process. Basil Blackwell.

- Eastwood, J., Frischen, A., Fenske, M., & Smilek, D. (2012). The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612456044

- Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J., & Smilek, D. (2012). The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 482–495.

- Eley, D., & Kirk, D. (2010). Developing citizenship through sport: The impact of a sport-based volunteer programme on young sport leaders. Sport, Education and Society, 7(2), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357332022000018841

- Elias, N., & Dunning, E. (1986). Quest for excitement. Sport and leisure in the civilizing process. Basil Blackwell.

- Elliot, A. J., Murayama, K., & Pekrun, R. (2011). A 3 × 2 achievement goal model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 632–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023952

- Farrall, S., Gray, E., & Jones, P. M. (2020). The role of radical economic restructuring in truancy from school and engagement in crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 60(1), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz040

- Ford, T., Parker, C., Salim, J., Goodman, R., Logan, S., & Henley, W. (2018). The relationship between exclusion from school and mental health: A secondary analysis of the British child and adolescent mental health surveys 2004 and 2007. Psychological Medicine, 48(4), 629–641. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171700215X

- Fox, P., & Avramidis, E. (2003). An evaluation of an outdoor education programme for students with emotional and behavioural difficulties. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 8(4), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750300507025

- Gaffney, H., Jolliffe, D., & White, H. (2022a). Mentoring Technical Report.

- Gaffney, H., Jolliffe, D., & White, H. (2022b). Mentoring Toolkit technical report.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

- Gerlinger, J., Viano, S., Gardella, J. H., Fisher, B. W., Curran, F. C., & Higgins, E. M. (2021). Exclusionary school discipline and delinquent outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(8), 1493–1509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01459-3

- Gill, K., Quilter-Pinner, H., & Swift, D. (2017). Making the difference breaking the link between school exclusion and social exclusion. http://www.ippr.org

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. (2010). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

- Goodwin, E. (2015). Psychological and behavioural disorders among young people in pupil referral units [Doctoral dissertation]. Royal Holloway, University of London.

- Gray, A., Woods, K., & Nuttall, C. (2022). Person-centred planning in education: An exploration of staff perceptions of using a person-centred framework in an alternative provision. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 27(2), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2022.2092065

- Gremmen, M., Berger, C., Ryan, A., Steglich, C., Veenstra, R., & Dijkstra, J. (2019). Adolescents’ friendships, academic achievement, and risk behaviors: Same-behavior and cross-behavior selection and influence processes. Child Development, 90(2), 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13045

- Griffen, W. H. (1981). Evaluation of a residential therapeutic camping programme for disturbed children. West Florida University, Education Research and Development Center.

- Harvey, J. (2001). The role of sport and recreation policy in fostering citizenship: The Canadian experience. Building Citizenship: Government and Service Provision in Canada, 23–46.

- Hignett, A., White, M., Pahl, S., Jenkin, R., & Le Froy, M. (2018). Evaluation of a surfing programme designed to increase personal well-being and connectedness to the natural environment among ‘at risk’ young people. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(1), 53–69.

- Hirschman, K., & Bourjolly, J. (2005). How Do tangible supports impact the breast cancer experience? Social Work in Health Care, 41(1), 17–32.

- Horner, L. (2019). Exploring the impact of physical activity on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and well-being of young people attending a pupil referral unit. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(Sup1), 40–41.

- House of Commons. (2018). Alternative Provision Education in England.

- Houtepen, L. C., Heron, J., Suderman, M. J., Fraser, A., Chittleborough, C. R., & Howe, L. D. (2020). Associations of adverse childhood experiences with educational attainment and adolescent health and the role of family and socioeconomic factors: A prospective cohort study in the UK. PLOS Medicine, 17(3), e1003031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003031

- Howard, R. C. (2011). The quest for excitement: A missing link between personality disorder and violence? Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 22(5), 692–705.

- Hunter, R., Gorely, T., Beattie, M., & Harris, K. (2021). Realist review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.2004610

- Ireland, L. (2019). Alcohol consumption among young people in marginalised groups. Young Adult Drinking Styles, 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28607-1_10

- Jaccard, J., Blanton, H., & Dodge, T. (2005). Peer influences on risk behavior: An analysis of the effects of a close friend. Developmental psychology, 41(1), 135.

- Johnson, M., Hamilton, M., Delaney, B., & Pennington, N. (2011). Development of team skills in novice nurses through an athletic coaching model. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 6(4), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2011.05.005

- Jones, M. I., Dunn, J. G. H., Holt, N. L., Sullivan, P. J., & Bloom, G. A. (2011). Exploring the “5Cs” of positive youth development in sport. Journal of Sport Behavior, 34(3), 250–268. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p = AONE&sw = w&issn = 01627341&v = 2.1&it = r&id = GALE%7CA263992245&sid = googleScholar&linkaccess = fulltext

- Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (2011). Well-being, reasonableness, and the natural environment. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(3), 304–321.

- Kinnafick, F. E., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2014). The effect of the physical environment and levels of activity on affective states. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 241–251.

- Kelly, L. (2011). Social inclusion through sports based interventions? Critical Social Policy, 31(1), 126–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018310385442

- Khazaei, S., Amin, M., & Faghih, R. (2021). Decoding a neurofeedback-modulated cognitive arousal state to investigate performance regulation by the Yerkes-Dodson Law. In 2021. 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) (pp. 6551–6557).

- Knowler, E. J., & Done, E. J. (2019). Exploring senior leaders’ experiences of off-rolling in mainstream secondary schools in England. BERA. Retrieved May 19, 2019, from https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/exploring-senior-leaders-experiences-of-off-rolling-in-mainstream-secondary-schools-in-england.

- Knowler, H., Lazar, L., Cortese, D., & Dillion, S. (2019). To what extent can the experience of outdoor learning contexts prevent permanent school exclusion for older learners? A visual analysis.

- Leone, L., & Pesce, C. (2017). From delivery to adoption of physical activity guidelines: Realist synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(10), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101193

- Leutz, J., & Beaumont, S. (2019). Community gardening: Integrating social responsibility and sustainability in a higher education setting—A case study from Australia. Social Responsibility and Sustainability, 1, 493–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03562-4_26

- Lindt, S., & Blair, C. (2017). Making a difference with at-risk students: The benefits of a mentoring program in middle school. Middle School Journal, 48(1), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2017.1243919

- Mainwaring, D., & Hallam, S. (2010). ‘Possible selves’ of young people in a mainstream secondary school and a pupil referral unit: A comparison. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 15(2), 153–169.

- Marchal, B., Van Belle, S., Van Olmen, J., Hoeree, T., & Kegels, G. (2012). Is realist evaluation keeping its promise? A review of published empirical studies in the field of health systems research. Evaluation, 18(2), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012442444

- Martin-Denham, S. (2020). A review of school exclusion on the mental health, well-being of children and young people in the City of Sunderland.

- McCluskey, G., Cole, T., Daniels, H., Thompson, I., & Tawell, A. (2019). Exclusion from school in Scotland and across the UK: Contrasts and questions. British Educational Research Journal, 45(6), 1140–1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3555

- McEwan, D., & Beauchamp, M. R. (2014). Teamwork in sport: A theoretical and integrative review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 229–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2014.932423

- McMillan, C., Felmlee, D., & Osgood, W. (2018). Peer influence, friend selection, and gender: How network processes shape adolescent smoking, drinking, and delinquency. Social Networks, 55(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.05.008

- McShane, J. (2020). We know off-rolling happens. Why are we still doing nothing? Support for Learning, 35(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12309

- Merton, R. (1967). On theoretical sociology: Five essays, old and new (624th ed.). Free Press.

- Mills, M., & Thomson, P. (2018). Investigative research into alternative provision.

- Moeijes, J., van Busschbach, J. T., Bosscher, R. J., & Twisk, J. W. (2018). Sports participation and psychosocial health: A longitudinal observational study in children. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1.

- Morgan, H., Parker, A., & Marturano, N. (2021). Evoking hope in marginalised youth populations through non-formal education: Critical pedagogy in sports-based interventions. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1894547

- Morgan, H., Parker, A., Meek, R., & Cryer, J. (2019). Participation in sport as a mechanism to transform the lives of young people within the criminal justice system: An academic exploration of a theory of change. Sport, Education and Society, 25(8), 917–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1674274

- Morgan, H., Parker, A., Meek, R., & Cryer, J. (2020). Participation in sport as a mechanism to transform the lives of young people within the criminal justice system: An academic exploration of a theory of change. Sport, Education and Society, 25(8), 917–930.

- Na, C., & Paternoster, R. (2018). Prosocial identities and youth violence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 56(1), 84–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427818796552

- Neff, P. (1973). Better tomorrows. Girl’s Adventure Trails.

- Nichols, G. (2010). Sport and crime reduction: The role of sports in tackling youth crime. Routledge.

- Norris, E., Shelton, N., Dunsmuir, S., Duke-Williams, O., & Stamatakis, E. (2015). Physically active lessons as physical activity and educational interventions: A systematic review of methods and results. Preventive Medicine, 72(1), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.027

- O’Donovan, T., MacPhail, A., & Kirk, D. (2010). Active citizenship through sport education. International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 38(2), 203–215.

- Pardede, S., Gausel, N., & Mjåvatn Høie, M. (2021). Revisiting the “The breakfast club”: testing different theoretical models of belongingness and acceptance (and social self-representation). Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1), 604090.

- Parker, A., Meek, R., & Lewis, G. (2014). Sport in a youth prison: male young offenders' experiences of a sporting intervention. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(3), 381–396.