ABSTRACT

The Home Advantage (HA) phenomenon, where teams perform better in front of their fans, has garnered increased interest during the COVID-19 pandemic, which provided a unique opportunity to study HA without crowd presence. Despite the presence of useful conceptual frameworks, most previous research has focused on investigating isolated individual factors. Here we review our newly developed Home Advantage Mediated (HAM) model, which considers all major factors and their interrelations simultaneously. HAM assumes that the crowd effects are mediated through other relevant factors, such as referee bias and team performance. Most importantly, HAM can be formally expressed as a mediation model, a technique widely employed in social sciences for investigating causal pathways. We demonstrate how researchers can use HAM to model the HA in European football and how moderating variables, such as COVID-19 and the absence of fans, can be incorporated into the model to disentangle the processes behind the HA phenomenon. This model not only sheds new light on this well-established sports phenomenon but also guides the practical application of mediation and moderated mediation models in a Bayesian framework. This approach can be extended to other sports science areas, demonstrating the versatility and utility of our model.

Introduction

Home advantage (HA) is a well-documented phenomenon where sports teams perform better at home, observed across various eras and in both team and individual sports (Gómez-Ruano et al., Citation2021; Jamieson, Citation2010; Pollard & Gómez, Citation2014; Pollard & Pollard, Citation2005). Since the seminal work by Schwartz and Barsky (Citation1977), HA has been extensively investigated, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic which forced many sport events to take place behind closed doors. Key factors contributing to HA include supportive crowds and enhanced physiological and psychological conditions leading to improved home team performance. These aspects have been explored in existing HA frameworks (Carron et al., Citation2005; Courneya & Carron, Citation1992). However, a comprehensive model analyzing these factors and their interrelationships is lacking. Our Home Advantage Mediated (HAM) model addresses this gap by examining indirect effects and interactions among key HA factors. We detail the theoretical basis of HAM and its practical application, including how fan presence or absence moderates HA.

The paper is structured to first (narratively) review major HA theories and empirical evidence, focusing on different components like venue, psychological and physiological factors, performance, and referee bias. This review updates the last comprehensive analysis from Carron et al. (Citation2005), with a focus on proposing a new interconnected theoretical approach. The HAM model is then elaborated, including its statistical application in mediation and moderation. Empirical examples of the model are presented, highlighting the moderating effects of fan presence. For practical application, we provide an online Supplemental Material (oSM) with guidelines for implementing the HAM model in R, targeting interested practitioners.

HA theoretical frameworks

Home advantage (HA) is complex, with most researchers agreeing that the primary factor is the presence of home fans. Social facilitation theory (Zajonc, Citation1965) suggests that fan support, through expressive gestures and chants, positively affects the home team’s behavior (see Strauss, Citation2002; van Meurs et al., Citation2022). Additionally, an evolutionary perspective posits that the presence of an away team, viewed as intruders, can trigger protective responses in the home team (Furley, Citation2019).

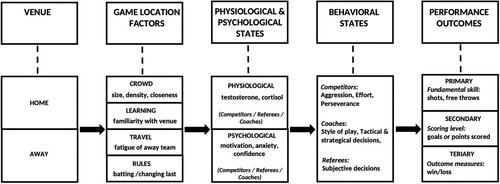

Arguably the most comprehensive conceptual framework of HA, given by Courneya and Carron (Citation1992) and later revised by Carron and colleagues (Carron et al., Citation2005), manages to integrate both social and evolutionary perspectives on HA. It identifies five HA components: game location, game location factors (like crowd and travel fatigue), psychological and physiological states, behavioral states, and performance outcome. This framework suggests a causal flow from venue factors to outcome, with the crowd atmosphere and territoriality inducing physiological changes that enhance home team performance. Additionally, this support might influence referee neutrality, further boosting HA ().

Figure 1. The ‘Classic’ Model of HA by Carron and colleagues (Citation1992; Citation2005). Adapted from Carron et al., Citation2005.

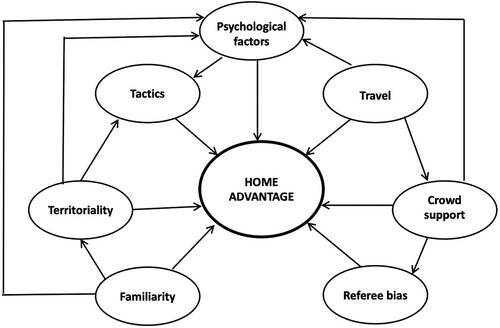

Similarly, Pollard and Pollard (Citation2005) postulated seven factors which interact with each other: crowd (support), travel (fatigue), familiarity (with local conditions), territoriality, tactics, psychological factors, and referee bias. Here the main idea is that these factors interact with each other, producing moderating effects and synergies (). For example, the crowd support influences HA directly, but also through its influence on the referees.

Figure 2. The ‘Interaction’ Model of HA by Pollard and Pollard (Citation2005). Adapted from Pollard & Pollard, Citation2005.

Game location factors

There is plenty of evidence for each of the components in these two conceptual frameworks. For example, idiosyncrasies of playing fields may have provided the home team with the advantage in familiarity in the past (Schwartz & Barsky, Citation1977). Nowadays, where the facilities are standardized, the advantage is rather small (Schwartz & Barsky, Citation1977), but home teams perform worse the first season after moving into new stadiums (Loughead et al., Citation2003; Pollard, Citation2002). Similarly, modern-day means of travel render the home advantage from the fatigue and sleep disruption of the traveling team (Waterhouse et al., Citation2004) almost nonexistent (Bilalić et al., Citation2021; Pollard et al., Citation2008). The exceptions are competitions where away teams not only often travel long distances, but also pass through different time zones (Goumas, Citation2013a; McHill & Chinoy, Citation2020). Similarly, processes which favor the home teams directly through the game rules (e.g. batting last in baseball, substitution in ice hockey) are rarely present and normally not an advantage (Carron et al., Citation2005). The other remaining factor, the presence of the crowd, is arguably the ultimate cause of the HA. The greater the number of home fans, either in absolute numbers (Armatas & Pollard, Citation2014; Clarke & Norman, Citation1995; Nevill et al., Citation1996) or relative to the capacity of the stadium (Agnew & Carron, Citation1994; Schwartz & Barsky, Citation1977), the better the performance of the home. Similarly, the closer they are to the playing field (Unkelbach & Memmert, Citation2010) or the more emotionally engaged the fans are (e.g. cheering and booing), the better the home teams perform (Armatas & Pollard, Citation2014; Unkelbach & Memmert, Citation2010).

Until recently, the evidence of the fans’ influence on the HA has remained correlational in nature. The recent pandemic which forced competitions behind closed doors, provided an ideal control condition for a causal estimation of fans’ impact on the outcome (for a review, see Leitner et al., Citation2022). The absence of fans dampens the advantage of home teams considerably, reducing it by almost a third for European soccer leagues (Bilalić et al., Citation2021). Even the presence of fans in restricted numbers, leaving most of the arenas empty as in the recently finished European Football Championship, dampens the advantage of home teams to a similar extent (Benz & Lopez, Citation2023; Bilalić, Graf, et al., Citation2023; Bilalić et al., Citation2021; Sors et al., Citation2022a). Similar findings were observed in North American sports, with reduced HA in basketball (NBA) and hockey (NHL) despite partial attendance (Higgs & Stavness, Citation2021; Leota et al., Citation2022). Sports in which the COVID-related restrictions have been less severe, such as baseball (MLB) and American football (NFL), did not show much HA reduction (Higgs & Stavness, Citation2021; Zimmer et al., Citation2021).

Physiological and psychological factors

While the evidence for the overall HA is overwhelming (Jamieson, Citation2010; Pollard & Gómez, Citation2014), the connection between the crowd support and the territoriality on the one hand, and the changes in physiological and psychological factors, on the other, is less robust. One of the main reasons is that there have been only a handful of investigations into the topic. The few investigations conducted, however, point toward the assumed causal process. It is assumed that the home crowd’s behavior alters physiological processes in both home and away team members (Greer, Citation1983). Similarly, evolutionary territorial responses to a perceived ‘home’ invasion should also modify physiological responses in players (Furley, Citation2019; Neave & Wolfson, Citation2003).

Most of the related research on physiological factors has focused on two hormones, testosterone and cortisol (for reviews, see Gray et al., Citation2017; Leicht et al., Citation2021). The hormone testosterone can be taken as an index of aggression based on animal studies (Carré et al., Citation2013; Fuxjager et al., Citation2009, Citation2010) and is associated with a higher metabolic rate of muscles (Griggs et al., Citation1989). In a sporting context, this may contribute to the willingness to exert more physical effort and in general for the motivation to compete (Jones et al., Citation2005; Neave & Wolfson, Citation2003). Research demonstrates that testosterone tends to be in general higher before home games (Arruda et al., Citation2014; Cunniffe et al., Citation2015; Neave & Wolfson, Citation2003; Tabassum et al., Citation2021) and lower before away games (Arruda et al., Citation2014; Carré et al., Citation2006; see Fothergill et al., Citation2017). Testosterone is also higher after a win at the home venue than after a win at an away venue (Carré, Citation2009). Testosterone levels drop after the match more in away players than in home players, despite the fact that home players had considerably higher levels before the game and therefore are statistically more likely to display a bigger drop (Tabassum et al., Citation2021).

Conversely, the hormone cortisol, which can be taken as an indicator of acute physical activity and stress (Contrada & Baum, Citation2010), has provided ambiguous results. On the one hand, there are studies in different sports and competition levels that indicate that home games elicit higher levels of cortisol than away games (Cunniffe et al., Citation2015; Fothergill et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, there are studies which indicate the reverse pattern where away games elicit more cortisol (Carolina-Paludo et al., Citation2020), no difference between venues (Arruda et al., Citation2014; Carré et al., Citation2006), or no differences between winners and losers (Gonzalez-Bono et al., Citation1999). The mixed results probably reflect the fact that cortisol can indicate fatigue and stress, which would be detrimental for athletic performance, but also general arousal of the organism and therefore better preparedness for conflict (Contrada & Baum, Citation2010; Gerber et al., Citation2012).

Psychological factors have mostly been assessed by self-reports and the results are somewhat mixed. There is plenty of evidence that the location of the competition affects the psychological states of competitors. For example, athletes display lower anxiety before home than away competitions (Bray et al., Citation2002; Thout et al., Citation1998). Given that anxiety is negatively related to confidence (Koivula et al., Citation2002), home players also project more confidence before games than away players (Bray et al., Citation2002; Kang & Jang, Citation2018; Thout et al., Citation1998). Athletes also believe they are more efficient playing in front of home fans (Bray & Widmeyer, Citation2000), as well as believing that they would master challenging situations more easily (Bar-Eli et al., Citation1995). On the other hand, there are a few studies that could not find differences in anxiety levels between playing at home and away (Arruda et al., Citation2014; Bray & Martin, Citation2003; Cunniffe et al., Citation2015; Duffy & Hinwood, Citation1997).

Other studies, however, also used estimates of observers. Neutral observers rate players’ behavior before games as more aggressive, assertive, and dominant when playing at home than when they compete away (Furley et al., Citation2018). As pointed out by Furley (Citation2019) in a review of what sports can tell us about human nature, these results and theoretical assumptions are consistent with an evolutionary-based territoriality model where these responses are seen as natural responses to protecting one’s territory (Furley, Citation2019; Neave & Wolfson, Citation2003). A recent study used a territoriality questionnaire to demonstrate that territoriality tendencies are indeed significantly higher in volleyball players playing at home than in away players (Tabassum et al., Citation2021; for a review on nonverbal behavior in sports, see Furley, Citation2023).

One of the main assumptions of Caron’s classical framework is that physiological and psychological aspects, caused by the crowd or territory responses, relate to each other. The model is silent when it comes to the causal flow, but one can imagine models where physiological factors influence the psychological responses. This flow reflects a foundational understanding that physiological changes provide a tangible, measurable baseline from which psychological states can be influenced and assessed. However, even psychobiological (Panksepp, Citation1982) and biofeedback theories (Schwartz & Andrasik, Citation2017), which are the theoretical basis for this approach, would suggest a complex interplay where psychological states can precipitate physiological changes and vice versa, highlighting the circular nature of their interaction. Certainly, other theories such as cognitive appraisal of emotion (Moors et al., Citation2013), would suggest even reverse casual flow which would go against the unidirectional impact and support a dynamic, reciprocal interaction between the physiological and psychological states of athletes. Therefore, it is possible to assume that both factors interact with each other. Both territoriality and social pressure, as possible HA explanations, would assume that physiological and psychological factors are related.

The studies of psycho-physiological interconnections are, however, rare. Even papers that assessed both factors, such as Tabassum et al. (Citation2021) who demonstrated that home players had both higher testosterone and territoriality levels, did not calculate correlations between them. The studies that looked into the association between the two factors, however, indicate a close link. First, studies with judo practitioners demonstrate that levels of testosterone and cortisol rapidly increase before competition compared to the period when there is no competition, just like psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, or even fatigue (Salvador et al., Citation1999, Citation2003). Unsurprisingly, pre-competition levels of testosterone are positively correlated to feelings of threat (Salvador et al., Citation1999), indicating the organism’s preparation for conflict. They are also highly negatively related to the feeling of fatigue (Salvador et al., Citation2003).

Second, there are a number of studies which indicate that the venue has a moderating effect on the psycho-physiological connection. Robazza and his colleagues (Citation2012) measured both biological indicators (including testosterone and cortisol) and psychological states (e.g. emotion, motivation, communication, effort) in professional basketball players before a dozen home games. The canonical correlation between the biological and psychological latent factors was rather high (>.54), indicating that physiological indicators were positively associated with the number and intensity of pleasant psychological states. Other studies also found that athletes with higher levels of testosterone have lower anxiety, whereas the reverse pattern is obtained between cortisol and anxiety (Filaire et al., Citation2001, Citation2009). In contrast, a couple of other studies found exactly the opposite pattern, where pre-match levels of testosterone are positively related to pre-match levels of anxiety, while cortisol was negatively related to anxiety (Arruda et al., Citation2014; Doan et al., Citation2007). These differences may relate to individual and team sports, but in general they point out that many specific contextual factors may play a role when assessing the link between physiological and psychological factors.

Behavioral states

Physiological and closely related psychological states are supposed to be reflected in behavior on the pitch. For example, home team members may exert more effort, that is, may run more, be more aggressive and possibly deal better with adversity. These team performance indicators then directly influence the outcome and therefore the HA.

We know that testosterone levels are dependent on the competitive situation, but they are also thought to module subsequent social behavior (Mazur, Citation1985). There is indeed plenty of evidence that testosterone during competition positively predicts subsequent motivation and aggressiveness (for reviews, see Carré et al., Citation2011; Carré & Olmstead, Citation2015). The relation to HA is, however, unclear, mostly because it is difficult to find an unbiased measure of aggression. For example, a measure of fouls committed by a team, which is often used as a proxy of aggression, is heavily influenced by contextual factors such as team performance and referee bias. In their initial overview, Courneya and Carron (Citation1992) expressed the view that such measures (e.g. block shots, steals, and rebounds in basketball) are hardly indicators of aggressive behavior. Subsequently, in his review, Carron (Carron et al., Citation2005) used the example of aggressive penalties (e.g. fighting) in hockey to illustrate the effect of the venue on behavioral states (McGuire et al., Citation1992). However, even here the effects are ambiguous because the home team accrued more aggressive penalties only in games they won, whereas for the away team, the pattern was reversed – there were more aggressive penalties when they lost.

Performance outcomes

This is seemingly the most straightforward factor in the framework, but even here there is a fine-grained differentiation and causal progression in complexity between different performance indicators. The primary indicators relate to basic skill performance (e.g. penalties, free throws, batting average), while the secondary indicators are already major building blocks (e.g. goals, points scored) on the way to the final outcomes. The tertiary outcomes are final outcomes (won/lost) with all their variations (e.g. point differential, ratio of final score). While not necessarily drawing on the sport analytics movement, the division of the performance outcomes is in line with some of the most influential predictive models in sport (Oliver, Citation2004). For example, factors used to predict the game outcome in basketball (e.g. free throws, rebounds, shooting, and turnovers) are primary performance indicators in Carron’s classical framework.

Referees and coaches

Similar to the players, the referee and the coaches are also assumed to be influenced by the crowd through the changes to their physiological and psychological factors. We do not have direct evidence for the crowd effects on the physiological and psychological states, but we do know that referees are biased by social pressure (Anders & Rotthoff, Citation2014; Greer, Citation1983; Raab et al., Citation2020). Referees generally issue fewer disciplinary warnings to the home team (Goumas, Citation2014a; Reade et al., Citation2022; Sutter & Kocher, Citation2004), but also award more penalties and injury time when the home teams are behind (Garicano et al., Citation2005; Schwarz, Citation2011; Scoppa, Citation2008), although this is not reflected in their self-reports on the causes of HA (Gershgoren et al., Citation2022). This bias is almost exclusively related to the presence of the fans, as the referee bias largely disappears when the matches are played behind closed doors (Bilalić et al., Citation2021; McCarrick et al., Citation2021; Pettersson-Lidbom & Priks, Citation2010; Scoppa, Citation2020; Wunderlich, Weigelt, et al., Citation2021).

Experimental studies also demonstrate that the presence of noise biases referees’ decisions as fewer warnings are administered to the home team than when the crowd noise was present than when it was absent or subdued (Balmer et al., Citation2007; Nevill et al., Citation1999, Citation2002; Sors et al., Citation2019). The reasons for referee bias are most likely multifaceted (Allen & Jones, Citation2014), but these experimental studies indicate that referees often use the crowd reactions (e.g. noise) as cues for their decisions. Some of these studies also measured anxiety levels in referees. It turns out that anxiety interacts with social pressure because more anxious referees demonstrated a greater bias toward home teams than their less anxious colleagues (Balmer et al., Citation2007).

Most evidence of the home venue’s influence on coaches comes from in-play statistics. The offensive focus of home teams leads to their greater possession when playing at home, as well as positioning players closer to the opponents’ goal as compared to away matches, in general (Clemente et al., Citation2013) and even without ball possession (Santos et al., Citation2017). The same teams used high-pressure lines, built up possession more often, kept the ball more in the final third, and crossed more frequently and passed with more pace (Fernandez-Navarro et al., Citation2018).

One of the rare experimental studies on the influence of playing at home on coaches (Staufenbiel et al., Citation2015) demonstrated that when playing at home, coaches set more challenging targets and choose more offensive/aggressive playing tactics. They field more offensive players, when substitute players they tend to field more offensive and are less satisfied with a draw result at half-time (Staufenbiel et al., Citation2015). These results reflect the fact that coaches have higher expectations of winning when playing at home.

The mechanisms of home advantage

Carron’s (Carron et al., Citation2005; Courneya & Carron, Citation1992) and Pollard’s (Pollard & Pollard, Citation2005) frameworks have provided a useful way of categorizing individual factors of HA. They have also provided mechanisms behind the HA, at least in an implicit manner. Carron and his colleagues (Citation2005), for example, talk about causal flow when they refer to individual factors and relations between them:

The four game location factors, in turn, are considered to influence first critical psychological states and then critical behavioural states of three groups of actors involved in the outcome – coaches, competitors and officials. (Carron et al., Citation2005, p. 396)

… game location (i.e. home versus away) is assumed to be directly related to a series of game location factors (crowd, etc.), which, in turn, are assumed to differentially affect the psychological states, behaviours and, ultimately, performance of coaches, athletes and officials. (Carron et al., Citation2005, p. 405)

The Pollard model (Citation2005) is even more explicit about direct and indirect relations between the HA factors as depicted in :

Our main conclusion is that home advantage in soccer is due to many factors and that most of these factors interact with each other. (Pollard & Pollard, Citation2005, p. 34)

Despite these implicitly and/or explicitly postulated mechanisms behind the HA, the subsequent research on HA has remained remarkably agnostic when it comes to the underlying causes of HA. For example, most of the research investigates the main HA factors such as referee bias and team performance separately. One can investigate referee bias first, then use a similar regression approach to investigate the indicators of team performance (Castellano et al., Citation2012; Downward & Jones, Citation2007; Goumas, Citation2013b, Citation2014b, Citation2017; Nevill et al., Citation2002; Park et al., Citation2016; Sors et al., Citation2021, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). In rare instances where all factors, including referee bias and team performance, are taken simultaneously as predictors of the HA, their interrelations have not been specified (Armatas & Pollard, Citation2014; Boyko et al., Citation2007; Bryson et al., Citation2021; Goumas, Citation2014b; Johnston, Citation2008; Wunderlich, Seck, et al., Citation2021).

This mostly theory-devoid approach ignores the theoretically assumed subsequent process between factors and their interconnection. It is not only suboptimal from the epistemological perspective, but it could also lead to incorrect conclusions. The referee may indeed demonstrate home team bias, but that could be simply a consequence of the team performance. A dominant attacking home side may force the passive defending away side to resort to fouling to prevent the better-performing home side from advancing (Carmichael & Thomas, Citation2005; Goumas, Citation2014a). Similarly, other contextual factors, such as switching between rule-based decision-making and mere game management depending on the context such as score and/or crowd behavior (Raab et al., Citation2020; Riedl et al., Citation2015), could influence referees’ performance as the game unfolds. Consequently, one needs to control for team performance to disentangle the referee bias from the performance. Even when all factors are in the regression as the predictors of the HA, we still do not know whether the HA is a consequence of referees’ behavior independent of the team performance, nor do we know to what extent referees’ behavior and/or team performance cause HA.

Home advantage mediated (HAM) model

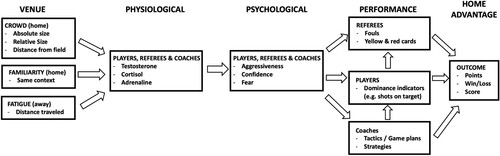

Here we describe our recently developed theoretical model (Bilalić, Graf, et al., Citation2023; Bilalić et al., Citation2021) which allows us to answer these questions. The model builds on the classical Carron model (Carron et al., Citation2005; Courneya & Carron, Citation1992), as the causal flow starts with the venue factors and moves toward the outcome (HA) subsequently through physiological, psychological, and performance-related indicators (see ). There are, however, three essential revisions and extensions: (1) interactive effects of physiological and psychological factors, (2) specification of in-game performance indicators as the behavioral states, and (3) explicit inclusion of a potential referee bias.

Figure 3. Home Advantage Mediated (HAM) model. The crowd presence influences how players, referees, and coaches feel (physiological and psychological factors), which in turn influences their performances, which are then acting as the determinants of the outcome. In the traditional framework (Carron et al., Citation2005), the performances of players, referees, and coaches are incorporated in the outcome/HA. Here they are an independent factor, which mediates the influence of physiological and psychological factors (and consequently the influence of the crowd).

The new model assumes that physiological states precede psychological factors, primarily to maintain consistency with Caron’s classical framework (Carron et al., Citation2005). It should be noted that there are theoretical arguments supporting both causal directions (Martin et al., Citation2020; Schachter & Singer, Citation1962), as well as the interaction between these two factors. Consequently, the new model could easily be reframed to allow both factors to interact with and influence each other concurrently, depending on the theoretical preferences of the researchers.

Second, the behavioral states in the classical model are replaced by team (or individual, depending on the sport) performance indicators. The behavioral states were defined somewhat ambiguously and subjectively in the classical framework (Carron et al., Citation2005). How much athletes exert effort, how aggressive they are, and how they behave in general, is not easy to define and measure, which probably resulted in the mixed findings reviewed above. In contrast, the primary indicators of the outcome in the classical framework, such as amount of possession, and the number of attacks and shots, are much better indicators of the actual (team) behavior and performance than those commonly measured, such as aggression. Categorizing team performance indicators as a part of the outcome may make sense on a theoretical level. Practically, it has led researchers to use team performance indicators as proxies for the outcome itself. They are, however, a crucial independent factor that objectively reflects (team) performance, and consequently need to be separated from the actual outcome.

Finally, the model postulates the presence of referee bias explicitly, unlike the classical model where the referees’ decisions were marginalized (for another way of including referees as a factor, see Dosseville et al., Citation2016). The referee bias can be measured objectively by behavioral indicators such as official warnings. Both referee bias and team performance are indicators of performance, the former of referees, the latter of teams/players. They have a direct influence on the outcome and are influenced by psycho-physiological factors related to the home venue. The model assumes, however, that they are closely and causally related to each other. For example, less dominant defending teams, which are generally away teams, tend to receive more warnings as they try to fend off the more dominant attacking home teams (Carmichael & Thomas, Citation2005; Goumas, Citation2014a). In other words, team performance not only influences the outcome directly, but it also affects other factors, such as referees’ decisions. A complete model needs to account for this and other interdependencies between factors. That is why our revised model has both referee bias and team performance as independent factors (see ).

The new model is based on a combination of direct effects and mediations: the venue factors influence the outcome, but that influence is only indirect as the venue factors such as the crowd first affect the physiological factors of the main players, which in turn affect their psychological factors. The psychological factors are then reflected in the performance of players, referees, and coaches. The model assumes that only the performance (of teams and referees) influences the outcome directly. We call this new framework the Home Advantage Mediations (HAM) model because it is based on the theoretically assumed mediations between the concepts. The home advantage is mediated by a number of factors, most notably the performance of the main protagonists.

We describe the HAM model using the example of European football. The HAM model can, however, be easily generalized to other sports, since the main factors, such as the team performance and referees bias, are universal for any sport.

Statistical specification of the HAM model

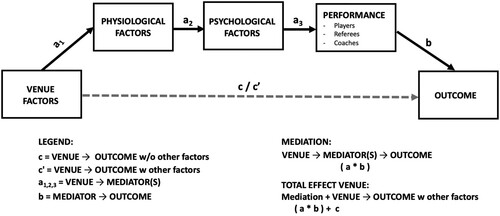

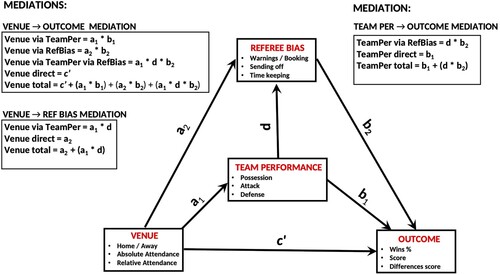

The advantage of the HAM model is that it can be easily re-specified into a classical mediation model (see ). In this mediation model, we have the influence of the initial variable (here Venue) on the end variable (Outcome) being mediated by another variable (here Physiological, Psychological, and Performance factors). The venue factors predict the outcome directly (the relation c) but its direct influence is weakened when other mediating factors (e.g. Performance) are included in the model (the Venue → Outcome relation when other factors have been included in the model is denoted by c′). The relation between the Venue and the mediating factors is expressed in a serial mediation (a series of mediations labeled by a1, a2, and a3), while the final mediating factors, the Performance, directly influences Outcome (relation labeled by b). The effect of the Venue on the Outcome through the Performance is represented by the mediation effect (a * b), while the overall effect of the Venue on the Outcome encompasses the indirect mediated effect (a * b) as well as the remaining direct effect (c′) when all mediating factors are included in the model (see ).

Figure 4. HAM model expressed as a mediation model. Venue factors predict the Outcome on their own (c’) but once the other factors are in the regression (e.g. physiological, psychological, and performance factors), the direct relation (c) is mediated through these factors.

Given that information on physiological and psychological factors is difficult to obtain, researchers will encounter the performance indicators without the physiological and psychological predecessors. When we re-specify the theoretical model into a classical mediation model (see ), we have the influence of the initial variable (here Venue) on the end variable (Outcome) being mediated by other variables (here Performance and Referee Bias). The venue factors predict the outcome directly (the relation c), but its direct influence is weakened when other mediating factors (e.g. Performance and Referee Bias) are included in the model (the Venue → Outcome relation when other factors have been included in the model is labeled by c′).

Figure 5. HAM in practice. With the records of physiological and psychological factors usually not available, Venue is mediated directly through Team Performance and Referee Bias (mediations specified in the left boxes). The Team Performance is mediated through the Referee Bias (mediation specified in the right box). The relations between concepts are labeled using small letters, and are then used to express the manipulations for calculating the mediation and total effects.

The effect of the Venue on the Outcome is mediated through the Performance (a1 * b1), as well as through the Referee Bias (a2 * b2). There is a path for the Venue to influence the Outcome indirectly through Team Performance and then Referee Bias (a1 * d * b2). In other words, the Venue exercises influence on the Outcome because it causes the team to perform better, which in turn leads to fewer official warnings, which in the end influences the outcome.

The overall effect of the Venue on the Outcome encompasses the three mediations (a1 * b1 + a2 * b2 + a1 * d * b2), as well as the remaining direct effect (c′) when all mediating factors have been included in the model (see ). This also enables partitioning the HA into composites, that is how much the Venue influences the HA through Team Performance, how much through Referee Bias, and how much by itself, directly.

Besides the Venue → Outcome mediations, there are two other mediations of interest. The first one is Venue → Referee Bias, which is mediated through the Team Performance. As mentioned above, better-performing teams generally force the other side to resort to stopping them through illegal means (e.g. fouling), which is reflected in the official warnings for the away team. The total effect of the Venue on the Referee Bias should then account for this tendency. The HAM model uses the Team Performance as the mediating factor of the Venue → Referee Bias relations. The total effect of the Venue on the Referee Bias is not only its direct effect, but also the mediating effect of the Venue through the Team Performance.

The second mediation is the relation where Referee Bias mediates the influence of the Team Performance on the Outcome. The performance of the team may not only directly influence the outcome, but also force the hand of referees, which is also an important predictor of the outcome. Consequently, the total effect of the Team Performance on the Outcome includes both the direct and mediating (through Referee Bias) effects.

The HAM model is flexible enough to accommodate differences between sports and competition types. If there is no need for Referee Bias, the model is easily specified without this factor. Similarly, if it is not the crowd that influences the results, but rather familiarity with the court and/or fatigue through distance, the Venue factor can be easily respecified to include these factors instead of or even in addition to the crowd (see Bilalić et al., Citation2021).

Illustration of the HAM model

The COVID-19-aftected season 2019–2020 in European football

In our recent study, we utilized the Home Advantage Mediated (HAM) model to analyze the unique 2019/2020 European football season impacted by COVID-19 (Bilalić et al., Citation2021). This season was distinctive as the majority was played with fans, while the final quarter occurred behind closed doors, offering a natural experiment to assess the impact of fan presence on home advantage (Dunning, Citation2012). We initially apply the HAM model to the part of the season with fans, then illustrate how it can incorporate additional factors like the Video Assistant Referee (VAR) and detailed team performance indicators. Furthermore, we demonstrate the model’s adaptability to include variables like the absence of fans due to COVID-19 for the season’s final quarter, as well as its application to the European Championship (EURO 20) and Nations League international friendly games.

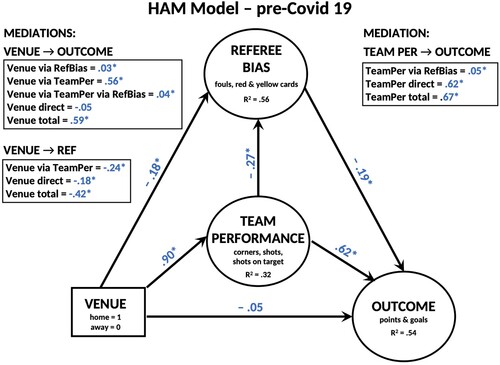

We used standardized composite scores for the main variables of interest, such as Outcome (goals scores and points won), Referee Bias (official warnings), and Team Performance (shots and corners). illustrates the results of the HAM model on the first ¾ of the 2019/2020 season when the fans were present. Before detailing the results of the HAM model, it is worth stating the simple correlations between the individual predictors and the outcome in isolation. The Venue itself was highly correlated with Outcome in isolation (Venue – Outcome rpb = .34). Similarly, the better team performance had a strong association with the Outcome on its own (Team Performance – Outcome r = .71), just like the official decisions (Referee Bias – Outcome r = −.37). However, when all factors are simultaneously in the HAM model, we see that both better team performance (.62) and less referee bias (i.e. fewer warnings; −.19) led to the better outcome, but their magnitude is much smaller than when they are correlated individually. Moreover, the direct influence of the home venue was completely mediated and was not relevant (−.05). Note that we do not include team strength, arguably the main confounder, in the HAM model here for the sake of simplicity (see Bilalić et al., Citation2021, Bilalić, Graf, et al., Citation2023 for how this can be implemented).

Figure 6. HAM (pre-Covid-19) Model – Mediation. The interplay between Venue, Team Performance, Referee Bias, and Outcome (the circular shape denotes latent variables, with the individual variables listed within the boxes). Lines with single-end arrows indicate the direction of influence. The numbers on the line are path model coefficients. The statistically consistent coefficients (95% credible intervals do not encompass 0) are indicated with *. The mediation of Venue on Outcome through Team Performance and Referee Bias individually and simultaneously is formally tested in a mediation model (upper left box). The mediation of Venue on Referee Bias through Team Performance is also formally tested by mediation (lower left box). The indirect influence of Team Performance on Outcome through Referee Bias is formally tested by mediation (lower left box). R2 is Bayesian full model coefficient of determination.

The home venue was mediated by (1) team performance (the relation: Venue → Team Performance → Outcome), (2) referee bias (the relation: Venue → Referee Bias → Outcome), as well as by (3) both team performance and referee bias within a single path (Venue → Team Performance → Referee Bias → Outcome). Home teams were performing considerably better than away teams (.90), and they were on the receiving end of fewer official warnings (−.18). As mentioned above, team performance and referee bias then determined the outcome (.62 and −.19, respectively). The overall value of the mediation via team performance was larger (.56) than that of referee bias (.03) and team performance and referee bias (.04), but all three were significant sources of HA. Playing at home had a huge overall effect on the outcome – almost two-thirds (.59) of a standard deviation of the outcome.

The HAM model can also make statements about the referee bias itself. While both playing at home venue (−.18) and performing better (−.27) resulted in less official bias, a large part of the venue’s influence is mediated via team performance (the relation: Venue → Team Performance → Referee Bias; see second box on the left side in ). The actual mediation effect (−.24) is even larger than the remaining effect of the home field (−.18). Overall, playing home biases the referees for almost half a standard deviation (.42) when it comes to official warnings.

Finally, one can also see that the team performance’s influence on the outcome is mediated through referee bias (the relation: Team Performance → Referee Bias → Outcome; see the right-hand box in ). While this mediation effect was not particularly large (.05), the overall effect of performance on the outcome was huge – one standard deviation change in performance led to two-thirds of a standard deviation change in the outcome.

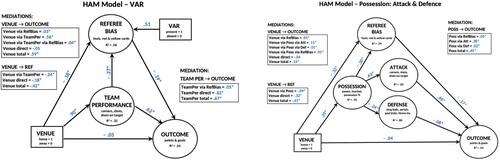

HAM model – external factors and more sophisticated models

The HAM model is capable of integrating additional factors, such as the impact of the Video Assistant Referee (VAR) on referee bias and game outcomes. Incorporating VAR into the HAM model involves simply adding it as a binary predictor of referee bias in the regression analysis. Our findings, illustrated in , show that including VAR does not significantly alter the overall results compared to the main model (). However, VAR had a notable positive impact on reducing home team bias, as indicated by an increase in official warnings for the home team in games with VAR (+.50). Despite this substantial effect, the estimates were highly variable, likely due to the widespread use of VAR in European leagues, leading to statistically less reliable effects.

Figure 7. HAM Model – VAR and Possession (attack/defense) variations. The VAR is added directly as an additional predictor of Referee Bias (left panel). The team performance indicators are modeled as Possession, which then lead to Attack and Defense indicators (right panel). See for further explanations.

The HAM model maintains simplicity in measuring team performance, but it allows for more complex iterations. For instance, team performance can be divided into attack (like shots and corners) and defense (including long balls, aerials, and goal kicks) metrics. These aspects are theorized to be influenced by ball possession metrics (touches, passes, possession time). In the HAM model, as shown in , possession is placed as a precursor to both attack and defense indicators, with the assumption that it alone affects referees’ decisions. However, our results show similar patterns whether we use just attack/dominance metrics or include possession, as in the more complex model. This indicates that the more sophisticated version does not necessarily provide a better fit than the simpler model in . Researchers need to weigh the benefits of simplicity against the realism of complexity in their models.

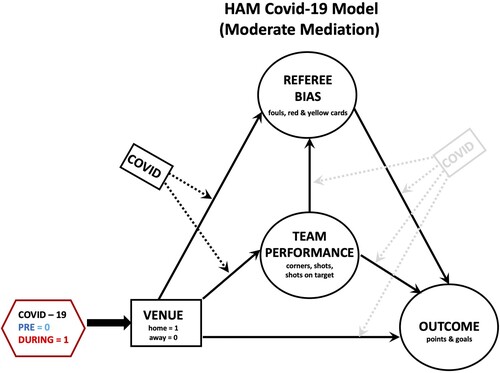

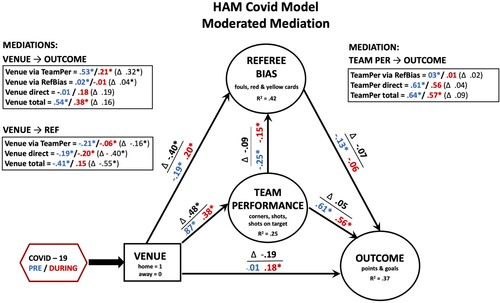

HAM COVID-19 model – moderated mediation

The 2019/2020 European soccer season presents a unique case study due to its interruption in March 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic. After playing ¾ of the season, the games were halted but later resumed in the summer, predominantly without fans. This situation creates a natural experiment (Dunning, Citation2012), allowing for the comparison of games with and without spectators, providing insight into the crowd effect on HA (for the use of COVID-19 as an intervening variable in psycho-sociological research, see Vaci et al., Citationunder review). The pandemic also poses a distinct challenge for HA modeling, but the Home Advantage Mediated (HAM) model adapts to this scenario. In this model, the presence or absence of fans is introduced as an interactive factor, moderating existing relationships within the model (). This scenario is often referred to as moderated mediation, where an external factor (in this case, COVID-19) influences the already established mediating relationships (Bilalić, Đokić, et al., Citation2023; Hayes, Citation2017). Theoretically, fan absence should primarily affect venue-related paths to team performance and referee bias, rather than directly impacting the outcome. Nevertheless, for thoroughness, our model also explores COVID-19’s potential moderating effects on other pathways.

Figure 8. HAM and moderated mediation. The Covid variable (pre- and post-Covid) acts as an external influence on the already established relations in the mediation model. In other words, the Covid variable interacts with the paths in the model. It therefore produces two values for the particular relation: one for the pre-Covid and another for the post-Covid period. Gray lines indicate that the moderation is not expected at the theoretical level.

Just as we conducted simple bivariate associations between predictors on the one hand, and the outcome on the other, in the pre-COVID period, here we first show that all predictors were weaker during the COVID-19 period: Venue – Outcome rpb = .16; Team Performance – Outcome r = .51; Referee Bias – Outcome r = −.11.

summarizes the results of the HAM model when the absence/presence, that is the COVID-19 moderator, is included in the HAM model (Bilalić et al., Citation2021). The pre-COVID estimates are given in blue color and are, unsurprisingly, very similar to those found in the model where only the pre-COVID games were considered (see ). In other words, the venue effect on the outcome is completely mediated by team and referee performance, while the referees are influenced both by venue and team performance.

Figure 9. HAM Covid-19 Model – Moderated Mediation Model. The Covid-19 factor, that is the presence and absence of fans, is added as the mediator in all relations in the HAM model. The numbers on the line are path model coefficients. The pre-Covid path coefficients are in blue, the during-Covid coefficients are in red, while their differences, indicated also by Δ, are in black. The coefficients that do not encompass 0 within their 95% credible intervals are indicated with *. See for further explanations.

The effect of COVID-19, which had only influence on a single factor in the HAM model, the venue, reverberated throughout the whole HAM model all the way to the outcome with the help of postulated mediations (see left boxes in ). The mediation through team performance was more than twice as small when there were no fans (.53 vs. .21), while the mediation through referee bias had a reversed effect (.02 vs. -.01). Overall, the presence of fans reduced the HA for about one third (from .54 to .38). The biggest shift was seen in the referee bias, which did not vanish, but was actually reversed. It was now away teams that were receiving fewer warnings (−.41 vs. +.15).

Other applications of the HAM model during COVID-19 period

We recently applied the HAM model to the latest European Championship in football (EURO 20), which also took place under some stadium restrictions and where several nations hosted games (Bilalić, Graf, et al., Citation2023). As a control condition we took the previous qualifying cycle, which was conducted with the presence of the fans, as well as the previous European championships starting from 1960. (left panel) demonstrates that the HA during EURO 20 was remarkably similar to that in the European football leagues – around half a standard deviation.

Figure 10. HAM Model – Partial attendance international competitions and international friendlies models. The EURO 20 international competition with partial attendance is compared to the performance of the same teams in the qualifications (left panel). International friendlies (Nations League) when they were played with fans present (2018) and fans absent (2020) – right panel.

The second finding was that, despite the partial presence of the fans during EURO 20, usually around one-third of the stadium capacity, the HA reduction was again rather similar to football – around one-third of the HA. However, unlike in the European leagues, where the referee bias played a role in the overall HA and its reduction, the referees’ decisions were irrelevant for the HA during EURO 20.

We also checked the international friendlies played in the Nations League (Sors et al., Citation2022a) played with or without the presence of fans (Bilalić, Graf, et al., Citation2023). (right panel) indicates that the overall HA is considerably lower in the international friendlies with the presence of fans than in the official competitive matches with fans mostly absent (e.g. EURO 20). The HA in semi-ghost competitive matches is almost three times bigger than the HA in friendly matches. The HA reduction due to the absence of fans is consequently larger in competitive matches than in friendly ones, but the difference is not as large as the initial difference in HA.

Discussion

The HA phenomenon has fascinated researchers for decades as evidenced by the amount of research conducted, specifically in the time of COVID-19. Unfortunately, the HA research has been somewhat atheoretical and focused on individual isolated factors. We presented here a newly developed model, firmly entrenched in the classical theoretical explanations (Carron et al., Citation2005; Courneya & Carron, Citation1992), which uses a series of mediations to disentangle the mechanisms behind the phenomenon and their individual contributions. The HAM model simultaneously estimates the influence of all important factors while they are concurrently interacting with each other, something that has been suggested (Carron et al., Citation2005; Pollard & Pollard, Citation2005), but rarely followed in research practice. Most importantly, we provide a statistical framework for interested HA researchers.

The advantages of the HAM model

The HAM model offers a number of advantages over other traditional ways of modeling and estimating HA. The simultaneous estimation of all relevant factors enables insight into the unbiased role of a single factor. For example, the referee bias may have a huge effect on the outcome on its own, which is indeed the case in the pre-COVID period as the correlation between referee bias and the outcome is sizable (r = −.37). However, when other factors such as team performance and venue factors are added into the equation, the effect is much smaller (−.17 – see ) because its influence has been partly explained by other factors. The HAM model, therefore, provides the answer to the question of whether and to what extent the main factors exert influence on the HA, even when the individual contribution of one factor accounts for the contribution of the other factor.

The HAM model also allows the uncovering of the mechanisms behind the HA. Before the play stopped because of the pandemic, the HA was considerable as the home teams had over a half of a SD better outcomes than the away teams (.55 – see , Total Venue estimates). The home advantage was completely mediated, however, through Team Performance (.56) and somewhat through the Referee Bias (.03). Referee Bias, and especially Team Performance, are therefore the mechanisms through which the home team achieves an advantage over the away team.

Finally, the interconnectedness of the individual factors in a single model allows for accommodating external factors. The COVID-19 factor, that is the absence of fans, has only a direct effect on the factor Venue (see ), yet its effect reverberates throughout the whole model because the model represents a single system of interconnected factors. The reduction in HA going from the pre-COVID period with fans to the during-COVID period without fans is about one-third of the initial pre-COVID HA (from .54 to .38 – see , Total Venue estimate). The reduction is, however, entirely achieved through the assumed indirect mechanisms of Team Performance and Referee Bias as the home team perform almost 2/3 worse without the fans (from .53 in pre-COVID to .21 in post-COVID period), and the Referee Bias is completely reversed, now harsher toward the home team, without the fans (from .02 in pre-COVID to −.01 in post-COVID period). The HAM model with moderated mediation ( and ) not only confirms the theoretical assumptions that the absence of the fans reduces the HA; it also provides the mechanisms for the reduction.

Generalization of HAM model

One should keep in mind inherent limitations related to the model itself. Specifically, the HAM model operates as a mediation model and, as such, necessitates the consideration of all possible confounding variables. It is imperative to account for external factors that could exert a direct effect on both the mediator and the outcome, as highlighted in the literature (Fiedler et al., Citation2011; Judd & Kenny, Citation1981; Rohrer et al., Citation2022). For example, within the realm of football, the overall strength of a team can influence Team Performance and Outcome, regardless of the game’s location. In a similar vein, the decisions made by referees can be affected by a team's dominance rather than the game’s setting alone. The HAM model can be expanded to consider these potential confounders. For example, in our previous research (Bilalić et al., Citation2021, Bilalić, Graf, et al., Citation2023), the team strength has been controlled for by adding team ratings, either FiveThirtyEight or Elo, as a covariate to the HAM model. Similarly, we demonstrated how additional indicators of team performance (e.g. defense/offense depended on possession) can be incorporated into the HAM model (see and Bilalić et al., Citation2021).

Our HAM model can easily accommodate other factors and control variables too. We have already demonstrated (Bilalić et al., Citation2021) how including technical solutions such as the Video Assistant Referee (VAR) as another predictor of Referee Bias (in addition to Venue and Team Performance – see ), dampens the referee bias (see Bilalić et al., Citation2021). Other factors, such as distance traveled (Travel factor in ), as well as Venue factors, such as absolute and relative (to the stadium capacity) attendance and the distance of the stands to the field, can all be accommodated in the HAM model (see Bilalić et al., Citation2021). We also demonstrated in the online supplement of Bilalić et al. (Citation2021) how the Home Advantage Model (HAM) accommodates various contextual factors, such as the match's importance, by including additional covariates in the model, and personal factors, like individual referee characteristics, by modeling referees as random effects. Similarly, team formations like 4-4-2 or 3-4-3 could indicate coaches’ strategies within the HAM framework. Although this is not an exhaustive list of home advantage (HA) factors (refer to the monograph edited by Gómez-Ruano et al., Citation2021, for a comprehensive overview of HA predictors), all these elements are theoretically modellable. Researchers must decide whether to pursue comprehensive models, which offer a more realistic depiction of the sport but might be overly complex and theoretically questionable, or parsimonious models.

We have demonstrated above how the HAM model can be used to estimate the strength of the HA in different competitions – the HA was nowhere near as pronounced in the international friendlies as in high-stake competitive team or international games, nor did the absence of fans reduce the HA in non-competitive games compared to the competitive ones (see ). Given that the HAM model uses standardized variables, it can not only provide insight about the size of the HA during different competitions but also between different eras. As long as the same indicators for the main concepts, such as team performance and referee bias, are available, comparisons with the help of HAM can also be done over time. This may help find the causes behind the currently observed trend of HA decline.

All these extensions related to static processes over a longer period, that is seasons. The HAM model can, however, be adapted for investigations of in-game dynamics. It is well known that all main protagonists are affected by the developments within a game, from coaches implementing different strategies to referees managing the game, to players expending effort depending on the game situation (Raab et al., Citation2020; Staufenbiel et al., Citation2015). It would be possible to divide the game into periods, based either on temporal (e.g. quarters) or situational (e.g. after a home side has fallen behind) factors, and assess the main factors and their relations to the HA magnitude. The insight into in-game dynamics may tell us, for example, whether the referee bias is particularly pronounced after the home side has fallen behind, or whether the sides instinctively retreated and start defending after establishing a lead, as well as how these trends relate to the overall HA.

Most importantly, the model is generalizable to other sports, since the main factors, namely the team performance and referee bias, are universal for any sport. For example, team performance in football is related to indicators of dominance such as shots, or actions close to the opponents’ goal, such as corners and free kicks. Hockey uses similar indicators that include shots on goal (e.g. CORSI and FENWICK), while in basketball, two (i.e. free throws and shooting) out of the four big factors (i.e. free throws, rebounds, shooting, and turnovers) are shooting-related indicators (Oliver, Citation2004).

Conclusion

We demonstrated how a single interconnected model can explain mechanisms and processes behind complex phenomena like HA. The HAM model clearly identifies the referees’ behavior and especially team performance as the paths to the HA, unlike numerous previous studies on the HA, which are silent about the processes behind it. We also demonstrate that the natural control condition, the absence of the fans, underlines the causal flow of the impact that team performance and referee bias have on the HA. We also provided an oSM which goes into detail on how to implement the HAM model. Our hope is that the demonstration will be of use to other researchers on the HA phenomenon, but also that the HAM model and its statistical equivalent will be of interest to researchers in sport and social science fields who are investigating systems of causes and consequences which are affected by external changes, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (see also Vaci et al., Citationunder review).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental material

The online supplemental material as a HTML file with detailed comments on the code and analysis can be retrieved from https://osf.io/wjqma/.

Data availability statement

The data and the code used for the analyses can be retrieved from https://osf.io/96tua/?view_only=5e1b7991696e47ec820087e2b3273a52.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agnew, G. A., & Carron, A. V. (1994). Crowd effects and the home advantage. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 25(1), 53–62.

- Allen, M. S., & Jones, M. V. (2014). The “home advantage” in athletic competitions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413513267

- Anders, A., & Rotthoff, K. W. (2014). Is home-field advantage driven by the fans? Evidence from across the ocean. Applied Economics Letters, 21(16), 1165–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2014.914139

- Armatas, V., & Pollard, R. (2014). Home advantage in Greek football. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(2), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.736537

- Arruda, A. F., Aoki, M. S., Freitas, C. G., Drago, G., Oliveira, R., Crewther, B. T., & Moreira, A. (2014). Influence of competition playing venue on the hormonal responses, state anxiety and perception of effort in elite basketball athletes. Physiology & Behavior, 130, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.03.007

- Balmer, N. J., Nevill, A. M., Lane, A. M., & Ward, P. (2007). Influence of crowd noise on soccer refereeing consistency in soccer. Journal of Sport Behavior, 30(2), 130.

- Bar-Eli, M., Levy-Kolker, N., Pie, J. S., & Tenenbaum, G. (1995). A crisis-related analysis of perceived referees’ behavior in competition. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 7(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209508406301

- Benz, L. S., & Lopez, M. J. (2023). Estimating the change in soccer’s home advantage during the Covid-19 pandemic using bivariate Poisson regression. AStA Advances in Statistical Analysis, 107(1), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10182-021-00413-9

- Bilalić, M., Đokić, R., Koso-Drljević, M., Đapo, N., & Pollet, T. (2023). When (deliberate) practice is not enough – The role of intelligence, practice, and knowledge in academic performance. Current Psychology, 42(27), 23147–23165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03336-z

- Bilalić, M., Graf, M., & Vaci, N. (2023). The effect of COVID-19 on home advantage in high- and low-stake situations: Evidence from the European National Football competitions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 69, 102492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102492

- Bilalić, M., Gula, B., & Vaci, N. (2021). Home advantage mediated (HAM) by referee bias and team performance during Covid. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00784-8

- Boyko, R. H., Boyko, A. R., & Boyko, M. G. (2007). Referee bias contributes to home advantage in English premiership football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(11), 1185–1194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410601038576

- Bray, S. R., Jones, M. V., & Owen, S. (2002). The influence of competition location on athletes’ psychological states. Journal of Sport Behavior, 25(3), 231–242.

- Bray, S. R., & Martin, K. A. (2003). The effect of competition location on individual athlete performance and psychological states. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4(2), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(01)00032-2

- Bray, S. R., & Widmeyer, W. N. (2000). Athletes’ perceptions of the home advantage: An investigation of perceived causal factors. Journal of Sport Behavior, 23(1), 1–1.

- Bryson, A., Dolton, P., Reade, J. J., Schreyer, D., & Singleton, C. (2021). Causal effects of an absent crowd on performances and refereeing decisions during Covid-19. Economics Letters, 198, 109664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109664

- Carmichael, F., & Thomas, D. (2005). Home-field effect and team performance: Evidence from English premiership football. Journal of Sports Economics, 6(3), 264–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002504266154

- Carolina-Paludo, A., Nunes-Rabelo, F., Maciel-Batista, M., Rúbila-Maciel, I., Peikriszwili-Tartaruga, M., & Simões, A. C. (2020). Game location effect on pre-competition cortisol concentration and anxiety state: A case study in a futsal team. Revista de Psicología Del Deporte, 29(1), 105–112.

- Carré, J., Muir, C., Belanger, J., & Putnam, S. K. (2006). Pre-competition hormonal and psychological levels of elite hockey players: Relationship to the ‘home advantage’. Physiology & Behavior, 89(3), 392–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.07.011

- Carré, J. M. (2009). No place like home: Testosterone responses to victory depend on game location. American Journal of Human Biology, 21(3), 392–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20867

- Carré, J. M., Campbell, J. A., Lozoya, E., Goetz, S. M., & Welker, K. M. (2013). Changes in testosterone mediate the effect of winning on subsequent aggressive behaviour. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(10), 2034–2041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.03.008

- Carré, J. M., McCormick, C. M., & Hariri, A. R. (2011). The social neuroendocrinology of human aggression. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(7), 935–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.02.001

- Carré, J. M., & Olmstead, N. A. (2015). Social neuroendocrinology of human aggression: Examining the role of competition-induced testosterone dynamics. Neuroscience, 286, 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.029

- Carron, A. V., Loughhead, T. M., & Bray, S. R. (2005). The home advantage in sport competitions: Courneya and Carron’s (1992) conceptual framework a decade later. Journal of Sports Sciences, 23(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410400021542

- Castellano, J., Casamichana, D., & Lago, C. (2012). The use of match statistics that discriminate between successful and unsuccessful soccer teams. Journal of Human Kinetics, 31(2012), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10078-012-0015-7

- Clarke, S. R., & Norman, J. M. (1995). Home ground advantage of individual clubs in English soccer. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series D (The Statistician), 44(4), 509–521.

- Clemente, M. F., Couceiro, S. M., Martins, F. M., Mendes, R., & Figueiredo, A. J. (2013). Measuring collective behaviour in football teams: Inspecting the impact of each half of the match on ball possession. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 13(3), 678–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2013.11868680

- Contrada, R., & Baum, A. (2010). The handbook of stress science: Biology, psychology, and health. Springer.

- Courneya, K. S., & Carron, A. V. (1992). The home advantage in sport competitions: A literature review. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.14.1.13.

- Cunniffe, B., Morgan, K. A., Baker, J. S., Cardinale, M., & Davies, B. (2015). Home versus away competition: Effect on psychophysiological variables in elite rugby union. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 10(6), 687–694. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2014-0370

- Doan, B. K., Newton, R. U., Kraemer, W. J., Kwon, Y.-H., & Scheet, T. P. (2007). Salivary cortisol, testosterone, and T/C ratio responses during a 36-hole golf competition. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 28(06), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-924557

- Dosseville, F., Edoh, K. P., & Molinaro, C. (2016). Sports officials in home advantage phenomenon: A new framework. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(3), 250–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2015.1023422

- Downward, P., & Jones, M. (2007). Effects of crowd size on referee decisions: Analysis of the FA cup. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(14), 1541–1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410701275193

- Duffy, L. J., & Hinwood, D. P. (1997). Home field advantage: Does anxiety contribute? Perceptual and Motor Skills, 84(1), 283–286. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1997.84.1.283

- Dunning, T. (2012). Natural experiments in the social sciences: A design-based approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Fernandez-Navarro, J., Fradua, L., Zubillaga, A., & McRobert, A. P. (2018). Influence of contextual variables on styles of play in soccer. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 18(3), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2018.1479925

- Fiedler, K., Schott, M., & Meiser, T. (2011). What mediation analysis can (not) do. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(6), 1231–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.007

- Filaire, E., Alix, D., Ferrand, C., & Verger, M. (2009). Psychophysiological stress in tennis players during the first single match of a tournament. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(1), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.022

- Filaire, E., Sagnol, M., Ferrand, C., Maso, F., & Lac, G. (2001). Psychophysiological stress in judo athletes during competitions. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 41(2), 263–268.

- Fothergill, M., Wolfson, S., & Neave, N. (2017). Testosterone and cortisol responses in male soccer players: The effect of home and away venues. Physiology & Behavior, 177, 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.04.021

- Furley, P. (2019). What modern sports competitions can tell us about human nature. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(2), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618794912

- Furley, P. (2023). The nature and culture of nonverbal behavior in sports: Theory, methodology, and a review of the literature. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 448–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1894594

- Furley, P., Schweizer, G., & Memmert, D. (2018). Thin slices of athletes’ nonverbal behavior give away game location: Testing the territoriality hypothesis of the home game advantage. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(2), 1–12.

- Fuxjager, M. J., Forbes-Lorman, R. M., Coss, D. J., Auger, C. J., Auger, A. P., & Marler, C. A. (2010). Winning territorial disputes selectively enhances androgen sensitivity in neural pathways related to motivation and social aggression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(27), 12393–12398. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1001394107

- Fuxjager, M. J., Mast, G., Becker, E. A., & Marler, C. A. (2009). The ‘home advantage’ is necessary for a full winner effect and changes in post-encounter testosterone. Hormones and Behavior, 56(2), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.04.009

- Garicano, L., Palacios-Huerta, I., & Prendergast, C. (2005). Favoritism under social pressure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(2), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1162/0034653053970267

- Gerber, M., Brand, S., Lindwall, M., Elliot, C., Kalak, N., Herrmann, C., Pühse, U., & Jonsdottir, I. H. (2012). Concerns regarding hair cortisol as a biomarker of chronic stress in exercise and sport science. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 11(4), 571.

- Gershgoren, L., Levental, O., & Basevitch, I. (2022). Home advantage perceptions in elite handball: A comparison among fans, athletes, coaches, and officials. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 782129. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.782129

- Gómez-Ruano, M. A., Pollard, R., & Lago-Peñas, C. (2021). Home advantage in sport: Causes and the effect on performance. Routledge.

- Gonzalez-Bono, E., Salvador, A., Serrano, M. A., & Ricarte, J. (1999). Testosterone, cortisol, and mood in a sports team competition. Hormones and Behavior, 35(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1006/hbeh.1998.1496

- Goumas, C. (2013a). Home advantage and crowd size in soccer: A worldwide study. Journal of Sport Behavior, 36(4), 387–399.

- Goumas, C. (2013b). Modelling home advantage in sport: A new approach. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 13(2), 428–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2013.11868659

- Goumas, C. (2014a). Home advantage and referee bias in European football. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(sup1), S243–S249.

- Goumas, C. (2014b). Home advantage in Australian soccer. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(1), 119–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.02.014

- Goumas, C. (2017). Modelling home advantage for individual teams in UEFA Champions League football. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 6(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2015.12.008

- Gray, P. B., McHale, T. S., & Carré, J. M. (2017). A review of human male field studies of hormones and behavioral reproductive effort. Hormones and Behavior, 91, 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.07.004

- Greer, D. L. (1983). Spectator booing and the home advantage: A study of social influence in the basketball arena. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46, 252–261. https://doi.org/10.2307/3033796.

- Griggs, R. C., Kingston, W., Jozefowicz, R. F., Herr, B. E., Forbes, G., & Halliday, D. (1989). Effect of testosterone on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis. Journal of Applied Physiology, 66(1), 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1989.66.1.498

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford.

- Higgs, N., & Stavness, I. (2021). Bayesian analysis of home advantage in North American professional sports before and during COVID-19. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93533-w

- Jamieson, J. P. (2010). The home field advantage in athletics: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(7), 1819–1848. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00641.x

- Johnston, R. (2008). On referee bias, crowd size, and home advantage in the English soccer premiership. Journal of Sports Sciences, 26(6), 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410701736780

- Jones, M. V., Bray, S. R., & Olivier, S. (2005). Game location and aggression in rugby league. Journal of Sports Sciences, 23(4), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410400021617

- Judd, C. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1981). Process analysis: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review, 5(5), 602–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X8100500502

- Kang, H., & Jang, S. (2018). Effects of competition anxiety on self-confidence in soccer players: Modulation effects of home and away games. Journal of Men’s Health, 14(3), 62–68.

- Koivula, N., Hassmén, P., & Fallby, J. (2002). Self-esteem and perfectionism in elite athletes: Effects on competitive anxiety and self-confidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(5), 865–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00092-7

- Leicht, A. S., Connor, J. D., & Deakin, G. B. (2021). Physiological basis for home advantage. In M. A. Gomez-Ruano, R. Pollard, & C. Lago-Penas (Eds.), Home advantage in sport (pp. 75–81). New York: Routledge.

- Leitner, M. C., Daumann, F., Follert, F., & Richlan, F. (2022). The cauldron has cooled down: A systematic literature review on home advantage in football during the COVID-19 pandemic from a socio-economic and psychological perspective. Management Review Quarterly, 73(2), 605–633.

- Leota, J., Hoffman, D., Mascaro, L., Czeisler, M. E., Nash, K., Drummond, S. P., Anderson, C., Rajaratnam, S. M. W., & Facer-Childs, E. R. (2022). Home is where the hustle is: The influence of crowds on effort and home advantage in the National Basketball Association. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(20), 2343–2352. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2022.2154933

- Loughead, T. M., Carron, A. V., Bray, S. R., & Kim, A. J. (2003). Facility familiarity and the home advantage in professional sports. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(3), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2003.9671718

- Martin, K., Périard, J., Rattray, B., & Pyne, D. B. (2020). Physiological factors which influence cognitive performance in military personnel. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 62(1), 93–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720819841757

- Mazur, A. (1985). A biosocial model of status in face-to-face primate groups. Social Forces, 64(2), 377–402. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578647

- McCarrick, D., Bilalic, M., Neave, N., & Wolfson, S. (2021). Home advantage during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analyses of European football leagues. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 56, 102013.

- McGuire, E. J., Widmeyer, W. N., Courneya, K. S., & Carron, A. V. (1992). Aggression as a potential mediator of the home advantage in professional ice hockey. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(2), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.14.2.148.

- McHill, A. W., & Chinoy, E. D. (2020). Utilizing the National Basketball Association’s COVID-19 restart “bubble” to uncover the impact of travel and circadian disruption on athletic performance. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56847-4

- Moors, A., Ellsworth, P. C., Scherer, K. R., & Frijda, N. H. (2013). Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emotion Review, 5(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912468165

- Neave, N., & Wolfson, S. (2003). Testosterone, territoriality, and the ‘home advantage’. Physiology & Behavior, 78(2), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00969-1

- Nevill, A., Balmer, N., & Williams, M. (1999). Crowd influence on decisions in association football. The Lancet, 353(9162), 1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01299-4

- Nevill, A. M., Balmer, N. J., & Williams, A. M. (2002). The influence of crowd noise and experience upon refereeing decisions in football. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 3(4), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(01)00033-4

- Nevill, A. M., Newell, S. M., & Gale, S. (1996). Factors associated with home advantage in English and Scottish soccer matches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 14(2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419608727700

- Oliver, D. (2004). Basketball on paper: Rules and tools for performance analysis. Potomac Books.

- Panksepp, J. (1982). Toward a general psychobiological theory of emotions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(3), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00012759

- Park, Y.-S., Choi, M.-S., Bang, S.-Y., & Park, J.-K. (2016). Analysis of shots on target and goals scored in soccer matches: Implications for coaching and training goalkeepers. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 38(1), 123–137.

- Pettersson-Lidbom, P., & Priks, M. (2010). Behavior under social pressure: Empty Italian stadiums and referee bias. Economics Letters, 108(2), 212–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2010.04.023

- Pollard, R. (2002). Evidence of a reduced home advantage when a team moves to a new stadium. Journal of Sports Sciences, 20(12), 969–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/026404102321011724

- Pollard, R., & Gómez, M. A. (2014). Components of home advantage in 157 national soccer leagues worldwide. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.888245

- Pollard, R., & Pollard, G. (2005). Long-term trends in home advantage in professional team sports in North America and England (1876–2003). Journal of Sports Sciences, 23(4), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410400021559

- Pollard, R., Silva, C. D., & Medeiros, N. C. (2008). Home advantage in football in Brazil: Differences between teams and the effects of distance traveled. Revista Brasileira de Futebol (The Brazilian Journal of Soccer Science), 1(1), 3–10.