Abstract

In this article, we unravel the production network of a large acoustic wall in a newly built theatre in Rotterdam. This project can be seen as a deviant case in the sense that it goes against the grain of the often observed long-term trend of erosion of the role of architects. This erosion signifies not just a loss for this specific group of professionals, but – given the omnipresence of the built environment in everyday life – also entails risks for society at large. We depart from the Global Network Approach, which can be considered as a heuristic tool to analyse complex production networks, spread out over several interdependent actors and locations. By focusing on the production process, we open up the black box of design in a creative industry based on in-depth interviews with the key players of the production network of the wall. We argue that the prominent role of the architectural practice involved is based on (1) their ‘digital workflow’ strategy; and (2) the specific network structure and relations which allowed them to be important in both design and realisation of the wall.

Introduction

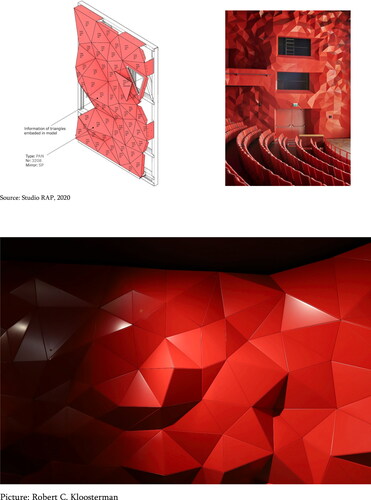

Although the newly built Theater Zuidplein in Rotterdam could only open its doors for less than a month due to the lockdown measure concerning Covid-19, it already attracted widespread attention from professionals and newspapers because of its daring design, both on the outside and on in the inside (De Architect Citation2020; NRC Citation2021). The acoustic wall of the main hall – consisting of some 6,000 unique aluminium composite 3D elements, aimed not only at achieving a very high level of sound quality but also at creating a striking visual effect – has received a lot of praise (De Volkskrant Citation2020; Architectenweb Citation2020; Junte Citation2020). This wall has been designed by Studio RAP, a young architectural practice located in a former shipyard hall in Rotterdam which prides itself on its innovative approach to design.

Moreover, Studio RAP is explicitly aiming at reclaiming a significant role of architects in the designing of the built environment. In recent years, architects have lost much ground in both European countries and the United States. With this retreat, a more holistic approach to the design of the built environment which encompasses social, cultural, contextual and aesthetic considerations has given way to one that focuses more on (quantifiable) indicators related to costs and benefits (Samuel Citation2018). The erosion of the role of architects is, hence, not just a loss for this specific group of professionals, but – given the omnipresence of the built environment in everyday life – also entails risks for society at large. The question, then, how this upcoming architectural practice has been able to reclaim a central role in the designing and realisation of this interior, thus transcends this particular case by far as it goes against the grain of a long-term trend. It, moreover, touches upon a more fundamental issue, namely how room for creativity and aesthetic concerns can be realised under capitalist conditions.

The shrinking of the creative role of architects is even more remarkable as it is one of the few, if not only, profession within the cultural and creative industries with protection of the title or certification in many countries (European Commission Citation2015; Meijer and Visscher Citation2014).Footnote1 The aim of certification is to protect society against incompetent practitioners and this should encourage demand for the services of certified professionals. These regulations concerning the legal position of architects would suggest a distinctive status and agency for architects within the production network of architectural design. However, certification has apparently offered scant protection against a serious erosion of their role in the shaping of the built environment.

More generally, architects have lost ground due to various developments in the broader field – e.g. increasing complexities in construction projects requiring a higher degree of specialisation driven by the twin processes of technological and regulatory change, ever-tighter timescales, and the practice of ‘de-risking’ projects in favour of cost efficiency and profitability as financialisation is turning real estate ever more into investment vehicles. This retreat has started much earlier (Blau Citation1984; Dent and Whitehead Citation2002; Jones Citation2006), but apparently has recently become more manifest (Imrie and Street Citation2011; Franck Citation2017; Samuel Citation2018). Tasks previously in the domain of architects are increasingly taken over by other actors – e.g. engineering firms, construction consultancies clients, and real-estate developers (Blau Citation1984). Contrary to the past, when architects might have supervised the entire production process from creation to completion, they are nowadays rarely responsible for more than a small part. Franck (Citation2017) argues that ‘increasingly, the role of the architect seems to be reduced to that of a “shaper”, a “form-giver”, a “designer” – with very limited responsibility regarding the outcome of the entire endeavour’.

Below, we present the case of a young and upcoming architectural practice Studio RAP, who explicitly attempts to reclaim a more prominent role on the basis of technological expertise, thereby going against the grain of recent developments. We have analysed the process of the design and production of the interior of the main hall of Theatre Zuidplein in Rotterdam. This project is highly relevant because it shows how architects can still claim a central and essential role in the design and realisation of the built environment, by innovating - in this case digitalising – the architectural method and techniques. It thus presents a deviant case which sheds light on how and under which conditions a larger creative role of architects can be reclaimed.

To address this question, we have applied the Global Production Network perspective (GPN) developed by Coe and Yeung (Citation2015), which offers a unique and innovative lens for disentangling the production process into different stages, highlighting for each stage the role of key actors, the distribution of power and how they are embedded in a broader societal context. This approach has been, so far, only rarely used in exploring concrete empirical cases in the cultural and creative industries (Coe Citation2015). We have unravelled the production network of the case of the interior design through detailed qualitative research – in-depth and semi-structured interviews with 9 key players in the production process.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The second section focuses on the process of marginalisation of architects in designing the built environment. In the third section we briefly describe the theoretical and analytical framework and cover the key concepts of this study. The fourth section provides a short description of the case. The fifth section unpacks the production network empirically. The final section presents an assessment of the conditions which have enabled this architectural practice to claim a larger role in the process of creation as well as a reflection on the usefulness of the GPN approach regarding creative industries more in general.

The erosion of the role of architects

In many European countries and the United States, the scope of architects’ activities is increasingly getting de-coupled from the actual construction of the building (Franck Citation2017). Their role seems to be reduced to that of a ‘form-giver’, often limited to coming up with the preliminary design (Samuel Citation2018). Architects are brought in at ‘strategic moments to deliver particular services such as “pretty drawings” to get through planning’ (Samuel Citation2018, 41). After completion of the preliminary design, other actors step in. According to Franck (Citation2017), ‘the master builder of past times, the generalist-architect who had the competence and capacity to integrally design, construct and build an edifice, is nowadays threatened by extinction’. A ‘risk of the architectural profession becoming a residual element of building and construction’ has, then, emerged (Imrie and Street Citation2014, 725). Instead, actors – such as real-estate developers, construction and management process consultants – are attaining much more prominent roles in the production process, as they increasingly take over tasks previously carried out by architects (e.g. making designs, supervising production and mediating between actors) (Davis Citation2008; Samuel Citation2018; Koetsenruijter and Kloosterman Citation2018). Hence, power dynamics regarding the distribution of tasks, responsibilities, and decision-making, are changing and this has typically resulted in the marginalisation of the architect (Samuel Citation2018).

A consequence of the de-coupling of architects from the realisation of the construction is that the close, direct relationships they had with clients has often made way for a more indirect form of relationship in which the communication operates via an intermediary. This intermediary role is increasingly taken over by project managers of construction companies who promote themselves as ‘enablers of communication’ (Dainty, Moore, and Murray Citation2006). As Kelly and Male (Citation1993, 5) argue, large construction companies have become more involved in both design and production, ‘offering services directly for the client [and] using their management skills to manage the process’. According to the Royal Institute of British Architects ([RIBA] Citation2000, Citation2005), the emergence of these project managers has resulted in a reduction of the professional autonomy of architects and their ability to influence different stages of the production process. As a result, architects have lost their more comprehensive role as clients’ personal advisers (Koetsenruijter and Kloosterman Citation2018). Accordingly, the position of architects is suggested to be compromised and ‘diminishing in its importance’ (RIBA Citation2005; Franck Citation2017; Samuel Citation2018).

Four analytically distinct, but often intertwined developments in field of architecture have fundamentally contributed to the erosion of the traditional role of architects: (i) changes in the design requirements; (ii) digitalisation of the design process; (iii) developments in market structures; and (iv) a blurring of the image of the architect (Hiley and Khadzir Citation1999; RIBA Citation2000, Citation2005; AIA Citation2007).

First, as a result of a heightened awareness for the complexity of construction projects, their socio-economic impact, and associated risks, the practices of architects are increasingly conditioned by a plethora of rules and regulations standards (Imrie and Street Citation2011, Franck Citation2017). Architects have witnessed an increase in functional demands from clients and more extensive and stringent building regulations stipulated by governments, which often go beyond their own knowledge and skills (Imrie and Street Citation2011). To comply with these changes, architects are increasingly dependent on specialist expertise of niche professions to assist them on issues such as health and safety, acoustics, material use and building regulations (Power Citation2004; Jones Citation2006; Imrie and Street Citation2011; Miller, Kurunmaki, and O’Leary Citation2008). Hence, production networks have expanded to include, among others, consultants, subcontractors, and suppliers, which are all responsible for small segments of production (Jones Citation2006). A specialised division of labour has allowed for a more complex system of risk sharing (Geertse Citation2014; Bos-de Vos et al. Citation2018). The fragmentation of work tasks, combined with the emergence of ‘new professional’ actors in design and production – such as the intermediary project managers – has decentred architects and possibly rendered them ‘less significant to the production of the built environment’ (Imrie and Street Citation2011, 19).

Secondly, digital technologies have fundamentally changed design processes (Microsoft & RIBA Citation2018). Designs no longer have to be made manually on a drawing board, but can be made digitally using techniques such as Building Information Modelling (BIM), Computed Aided Design (CAD) and 3D-printing (Bos-de Vos et al. Citation2018). This development is not necessarily detrimental to architects, as some argue it could potentially empower and enrich the discipline by providing new opportunities and methods for design creation. However, others hold that it ‘shifts responsibilities and time commitments of architects away from aesthetic considerations toward managerial ones’ (Imrie and Street Citation2011, xvi). In addition, many real-estate developers and construction consultancy firms have invested in these software, which enables them to take over design creation – a responsibility traditionally belonging almost exclusively to architects. Thus, due to technological improvements, product design is more directly accessible to different actors, potentially forgoing the necessity of architects’ expertise and skills in the design phase (Samuel Citation2018; Koetsenruijter and Kloosterman Citation2018).

Thirdly, concurring with more demanding building requirements, project dynamics increasingly revolve around establishing risk-reduction and cost-certainty for clients within ever-tighter timescales. The built environment has become ever more subject to capitalistic logic in many countries and real estate is seen as an investment vehicle aimed at lowering costs and boosting profits. This manifests itself, for instance, in the increasing importance in the design phase of project managers who have to deal with time and financial pressures. In addition, for architects, time pressures often already start when registering for competitions, when clients expect an unrealistic amount of unpaid work in a short time period (Loe Citation2000; Samuel Citation2018). These developments in real-estate markets, which prioritise risk-reduction, increased regulation, and cost-efficiency, have, hence, eroded the autonomy and creativity of architects.

Fourthly, due to changes in the distribution of labour, the role and responsibility of architects are no longer clearly delineated and self-evident. In the eye of the public, a loss of confidence in the architectural profession has taken place as they are often blamed for project delays and failures, and seen as subject to and dispensable by other actors in the field of architectural design (Imrie and Street Citation2011). A central issue is a lack of understanding and agreement about what it is exactly that architects do, know, and contribute – that is, their added value (ACE Citation2019; Van Kempen, Mathôt, and Kloosterman Citation2021). As a result, architects find it ever more challenging to defend their turf within the production process.

Both the British and American Institute for Architects as well as the Architects’ Council of Europe (Citation2019) have suggested that the status and autonomy of the architectural profession is under threat, due to its difficulty to adapt to changing values and demands, ‘having failed to capitalise on its core capability by not creating the range of skills needed to meet the demands of the modern construction industry’ (RIBA Citation2005, p. 38; see also AIA Citation2007; ACE Citation2019).

Production networks: phases, distribution of power, and embeddedness

To investigate how Studio RAP has been able to reclaim a prominent and creative role in the design of the built environment, we investigate the production network of the design and realisation of the acoustic wall. By focussing on the production process, we respond to Samuel’s criticism that many studies have limited their attention to the finished product, highlighting issues such as aesthetics and style (Samuel Citation2018). Consequently, how this result was achieved, remains very much a black box.

In order to analyse Studio RAP’s role within the production process of the interior of Theater Zuidplein, we have based our methodology on the GPN approach. The GPN approach can be considered as a heuristic tool to analyse complex production networks, spread out over several interdependent actors and locations (Coe Citation2015). The main goal is to disentangle and analyse the key flows between interconnected actors through which a specific good or service is created, produced, distributed, and consumed (Coe, Dicken, and Hess Citation2008).

The GPN approach emphasises a number of components that are of great relevance to our research. First, the GPN approach places the production network and process as the main objects of analysis. A central idea of this method is to slice up the production process into different phases, highlighting for each phase the different roles and tasks of actors in order to understand how a product is co-produced (Coe and Yeung Citation2015). Second, the approach emphasises the conceptual notion of embeddedness. Creative and cultural industries do not exist in a kind of vacuum, but are instead inserted in concrete socio-cultural and institutional contexts with formal rules, regulations and often deeply ingrained informal practices based on shared understandings, vocabularies, and a sense of a shared destiny determining the rules of the game (Becker Citation1982). To fully understand network dynamics, Coe and Yeung (Citation2015) argue for the importance of analysing how multi-scalar societal contexts undergird and thereby shape and constrain the actions of actors within production networks. Third, the GPN approach attempts to disclose dynamics of power. The approach tries to analyse which actors assume leading roles in production networks, as they often initiate, coordinate and control flows of financial, material and human resources between actors (Coe Citation2015). Leading actors are, in principle, easily identifiable, because the production network is structured around them. The role of the lead actor, then, is to decide on the inter-firm division of labour and value (Coe and Yeung Citation2015).

To conclude, by using relevant aspects of the GPN approach we are able to conduct in-depth research and analyse how the architect recaptures a more prominent role. The focus on the production network and process allows us gain detailed insights into the tasks and role of the architectural practice. In addition, by analysing the distribution of power and embeddedness, we sought to reveal the conditions under which architects are able to (re)gain more creative control of the design process and its realisation. By applying the GPN perspective, our focus is on relationships and linkages instead of place-based aspects which are central in the commonly used cluster and sector approaches.

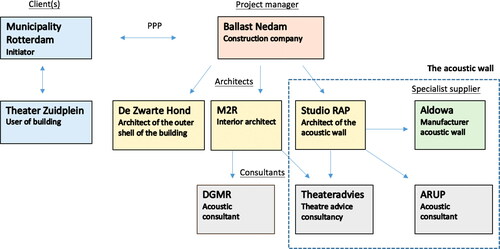

Theater Zuidplein

The project of Theater Zuidplein is part of a large urban renewal project (Hart van Zuid) initiated by the municipality of Rotterdam with the goal of strengthening Rotterdam Zuid economically, socially and culturally. A public-private partnership with, on the one hand, a partnership between the construction firms Ballast Nedam and Heijmans, and, on the other, the municipality, initiated a long-term collaboration to work on the overarching urban revitalisation project Hart van Zuid which included the construction of a new theatre. The project lasted more than 11 years, as the theatre was officially opened on September 16, 2020. Due to the complexity and size of this project, we have decided to narrow our focus of analysis to the process in which the interior of the main theatre hall, and especially the acoustic wall, was designed and realised. shows the production network consisting of a web of key actors with specific responsibilities and niche expertise.

Commissioning

In 2009, the municipality and direction of Theatre Zuidplein compiled a list of requirements for the new theatre. Ballast Nedam, in its role as project manager, assembled a team of actors to create a plan that met the clients’ demands. In the main theatre hall, M2R was appointed as the interior architect and DGMR and Theateradvies as acoustic and theatre consultants. Together they were responsible for designing the shape, dimensions, materials and acoustics. The latter, however, became problematic as the municipality and Ballast Nedam did not agree on M2R’s plan for the acoustic wall. The design exceeded the budget by half a million euros, causing Ballast Nedam to select another architect to carry out this specific task.

Because the initial tender for the acoustic wall had failed, the municipality was allowed to assign this commission without submitting a tender, and Studio RAP received the job right away. The municipality and Rotterdam-based Ballast Nedam spotted an excellent opportunity to support a local, young and innovative architectural practice and boost the urban economy.

The design of the acoustic wall

Studio RAP had never designed an acoustic wall before, so they depended on the knowledge of DGMR and Theateradvies to explain specific requirements and the influence of certain design choices. The engineering firm DGMR specialises in acoustic research and the calculation of sound values in order to offer precise architectural solutions. Theateradvies focuses solely on the functioning of theatres, by advising on logistics, the atmosphere, comfort, technology, accessibility and designing stage equipment.

Studio RAP’s architectural concept was to allow all theatre walls to merge into one another in one smooth movement. ‘The sides, balustrade and back wall had to radiate a unity and embrace the audience and artists, leading to an overwhelming feeling’. Studio RAP used a parametric model to test acoustics of innumerable designs. Because DGMR was not familiar with Studio RAP’s innovative digital approach, and lacked the skill and knowledge to use this software, Studio RAP was allowed to select two new partners: Arup as acoustic advisor, and Aldowa as the manufacturer.

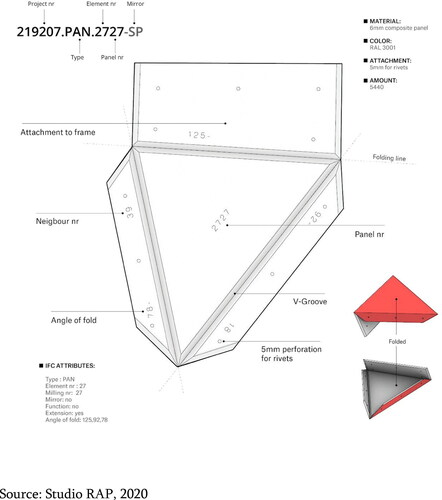

In a highly interactive process, Studio RAP consulted with Ballast Nedam, Arup, the municipality and Theater Zuidplein to move from sketch design, preliminary design, technical design, to the final executive design. Their end result: some 6,000 unique triangles of aluminium composite that fitted together perfectly. The optimal shape and position was determined for each panel on the basis of a parametric model, in which Studio RAP and Arup managed to keep a grip on the aesthetics and acoustics of the design. Using advanced software, the designers were able to determine exactly how the sound waves would spread throughout the hall. Flat triangles helped create a pure reflection, while folded triangles provided a diffuse reflection (De Architect Citation2020) ().

The production of the elements of the acoustic wall

The design, consisting of CAD-drawings, were forwarded to Aldowa, the manufacturer. Each triangle had a unique drawing, name, flaps, number, and angle rotation to put them together. The designs were sent directly to Aldowa’s machines, which then cut and folded 6,000 triangles. By means of algorithms, this was done as efficiently as possible. The plates had a nesting ratio of approximately 72% (leaving 28% waste). A unique number had been milled into each panel, facilitating the assembling of triangles on the construction site. Because Studio RAP generated and preserved the necessary information from their 3D model, they were able to supervise and control activities in design creation, preparation, engineering and construction ().

By means of their innovative and digital approach, Studio RAP refutes the idea that the fragile state of the architectural profession is ‘self-inflicted’ due to architects’ inability to adapt to changes in the broader field, or, as RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) (Citation2005, p. 38) suggested architects’ failure to create ‘the range of skills needed to meet the demands of the modern construction industry’. Instead, Studio RAP uses its digital design capabilities to expand the role of the architect. Studio RAP manages to take on more responsibilities and carry out a leading role in both design, engineering and construction. Below, we will take a closer look at Studio RAP’s strategy and the idea behind it.

Studio RAP’s strategy

Wessel van Beerendonk, co-founder of Studio RAP (founded in 2015) is very much aware of the marginalised role of the architect:

The tasks and responsibilities of architects have become much smaller. Master builders who took on the dual role of architect and constructor no longer exist. In the modern field of architecture, tasks are increasingly divided so that everyone is responsible for a small part. Nowadays, as an architect, you sit around the table with 20 other specialists and because of your specific responsibility, you get little say over the end product.

Van Beerendonk finds this worrying, because ‘the architect is often the only person who has to guard a kind of subjectivity, namely aesthetics’. Accordingly, Studio RAP attempts to enlarge its role and corresponding tasks by relying on a ‘complete digital workflow’, using ‘computational design with innovative digital fabrication methods’ (Studio RAP, n.d.). By specialising in innovative technology, they look beyond traditional building methods. This way, Studio RAP actively rethinks the architectural profession whilst improving the way to design, produce, manage and build architecture (Studio RAP, n.d.).

The benefits of digitalisation are already widely known, as digital designs are quite common among architects and contractors. However, with their ‘digital workflow’ strategy, Studio RAP takes it one step further by not only designing digitally but also building digitally, using specially designed algorithms and parametric models. According to Van Beerendonk, a digital workflow creates several advantages for the building process, as it leads to smaller error margins, as well as cheaper, more sustainable and more detailed production. Yet, just as important, it provides Studio RAP with a more prominent position within the production network. They acquire tasks in the design phase and subsequent construction, thereby reclaiming a more comprehensive role in the entire production process. Due to their exclusive knowledge on the use of digital design and building techniques, they are able to influence different stages of the production process, and take on a leading role to supervise and instruct other actors throughout the process.

Studio RAP’s strategy is strongly based on its digital and technological expertise:

As an architect you start designing with a certain vision, and it is so difficult not to make any concessions during the execution, or towards the execution. I’m not saying it’s wrong to make concessions, but it can take some pretty dire consequences. To counter this, we have built up expertise in designing and building. We are an architectural firm that knows how to make things. (…) With our expertise in software, we can extract detailed information to go directly from a digital design to digital production using robotics and 3D printing. Because we know how to build things, we are able to convince others of certain choices and this gives us strength to compromise less as well as take on more responsibilities. (van Beerendonk)

Thus, according to Van Beerendonk, Studio RAP’s knowledge on both creating designs and building them, allows them to make less concessions and increase their responsibilities. The project of Theater Zuidplein exemplifies this in three ways. First, in marked contrast to the current trend, Studio RAP was not only responsible for the design, but also prominent in the implementation phase. Secondly, because of the central role of its parametric design approach, Studio RAP was also able to take the lead in subcontracting Arup, and advising Ballast Nedam to subcontract Aldowa, who had to be familiar with this software. Thirdly, Studio RAP was also able to convince other actors of their design due to their specific knowledge on building. The municipality and Ballast Nedam were willing to take a risk by hiring Studio RAP and applying an innovative digital approach because of their persuasiveness. Studio RAP’s argument that their digital workflow would save costs and time, while at the same time increase the level of precision, was appealing. In addition, even their presentation was a software based performance: by showing their design virtually with 3D glasses, Studio RAP was able to convince the managing board of Theater Zuidplein as well. As Fred den Hartog, head of theatre facilities, mentioned:

In the beginning, our management was somewhat hesitant towards the design of RAP. But in the end, they presented their design with 3D glasses, and we were sold. With these glasses on, we virtually walked through the room. Studio RAP showed us in so much detail: this is what it will look like. That was very special.

So, Studio RAP’s ‘digital workflow’ approach ensured that the architect carried out tasks in de design and construction phase. Due to their innovative knowledge on software and building techniques, they were able to convince other actors of their design without having to make much concessions. Therefore, Studio RAP is an example of an architectural practice has been able to use digitalisation to strengthen its position. As Jones (Citation2006, p. 81) would say, they ‘break out of the mold of being “designers only” and look at ways to reclaim their lost responsibilities and also explore new alternative services’. However, Studio RAP’s strategy only partly explains why they, as the architect, succeed in obtaining a more prominent role in the production process. The embeddedness in a wider societal context determining the rules of the game has also been crucial in enabling Studio RAP to gain more control for the design process and its eventual realisation.

The embeddedness of the network

Institutional embeddedness

Studio RAP pursues a strategy aimed at taking on a more prominent and essential role based on their software expertise. However, it is not always possible for them to execute this strategy. When discussing Studio RAP’s architectural role, van Beerendonk complains about the constraints imposed on them by EU’s tendering rules, calling it a ‘tendering circus’. He refers to the EU legislation on public procurement, which governs the way public authorities purchase goods, works, and services from architectural practices. In case public sector commissions are above the financial threshold (as of January 1, 2020, 5.350.000 euros), public sector clients are obligated by the EU to follow a formalised procedure and outsource contracts objectively, transparently and in open competition. In these competitions, the different architectural designs are anonymously evaluated by an independent jury to stimulate innovation and architectural quality as well as improve transparency in allocation processes. The intention is to promote market forces and strengthen mutual competition, thereby getting the best possible value for public investments. For architectural practices, the rules should create an EU-wide level playing field, aiming to give practices a fair chance to compete for large construction projects (European Commission Citation2017; Koetsenruijter and Kloosterman Citation2018).

However, in practice, the public procurement rules have been consistently criticised for their paradoxical conditions: the rules aim to secure equal competition but in reality appear to increase inequality as it raises barriers to entry for smaller (starting) practices to participate in larger projects (Architectuur Lokaal Citation2020). Smaller practices lack the required track record showing experience with, for instance, designing schools, bridges, or hospitals to compete with larger practices. In addition, they face higher risks as larger practices are usually more capable to sustain lost investments in time, effort, and manpower if a project is not awarded (Koetsenruijter and Kloosterman Citation2018; Samuel Citation2018). Van Beerendonk, furthermore, points to another drawback of the EU tendering rules as these make it difficult for Studio RAP to pursue their ‘digital workflow’ strategy:

We mainly get a lot of assignments through one-on-one acquisition, where we go to a client and negotiate about the assignment and contract. With large public projects, you always end up in a tendering circus. The problem is that our working method doesn’t fit that kind of competitions. (…) If you win a tender, your responsibility is limited to the design and then they want to take over. So, our competitive position in a classic tender compared to other architects is not distinctive. That’s a problem because we start to distinguish ourselves in the phases after the design, when we go towards implementation and build everything digitally.

According to van Beerendonk, Studio RAP distinguishes itself primarily by digitalising both the design and construction phase. This strategy seeks to ensure that they take on more tasks, more responsibilities and obtain a greater say in the making of decisions of the entire production process, thereby counteracting the trend of marginalisation. However, tenders for architects are often focused solely on proposals for designs. The result is that the role of architects remains marginalised for these larger projects. Studio RAP, as a young practice, loses its competitive advantage when they have to work within those constraints. If the tendering procedure would allow architects to propose a plan for design and construction, Studio RAP would have a better chance in winning and in enlarging their role. This would innovate the role of the architect as well as the construction process – something the EU explicitly strives for through open market competition. However, at the moment, Studio RAP’s dual role hampers them from involvement in competitions as a result of EU’s limited focus on design, and consequently their innovation is demotivated. Studio RAP finds itself in a catch-22, on the one hand wanting and being urged by the EU to innovate, but, on the other, being restricted in doing so as a consequence of their own dual approach in relation to EU’s current tendering rules.

Fortunately for Studio RAP, the assignment to create the acoustic wall had a different procurement route. Since the first attempt had failed, Studio RAP was awarded the job without having to compete in a ‘tendering’ circus. This provided them with a unique opportunity to show off their skills and expertise in a larger and more prestigious project.

Socio-cultural embeddedness

The opportunity for Studio RAP thus directly arose because of the fact that the EU rules on commissioning had been circumvented. The rules of the game are, however, also shaped at lower spatial scales. In this case, we can argue that by proposing Studio RAP, the representative of the municipality of Rotterdam stayed true to a national and more in particular local Rotterdam tradition of opting for innovative architectural design (Kloosterman and Stegmeijer Citation2004; Kloosterman Citation2007; Kloosterman Citation2017).

I ran into Wessel from Studio RAP at a fair in Rotterdam and we got to talking. Studio RAP was a fairly new start-up company from the neighbourhood. (…) Studio RAP was not specialised in the design of theatres or acoustics…. but because of their innovative approach and the fact that they were from Rotterdam, I was interested in working with them. (Representative of the municipality)

In addition, Studio RAP’s increased role and responsibility was not only a direct result of their strategy, as other actors also pointed to a high degree of participation, which they attributed to different reasons. In the analysis of the socio-cultural embeddedness of the production network, three main aspects were brought to light: the proximity of local actors, shared priorities between actors and the willingness to take risks.

In more concrete sense and at an even lower level of scale of embeddedness, namely that of social networks, we can also identify crucial factors. First, what characterises this project is the geographic proximity of local actors. The municipality, Heijmans, Ballast Nedam, Theatre Zuidplein, M2R, De Zwarte Hond (the architectural practice which designed the outer shell of the building), Studio RAP, and Aldowa are all based in Rotterdam. Our interviews with the municipality and Ballast Nedam revealed that they were keen to collaborate with fellow ‘Rotterdammers’. By establishing a relatively strong local network, the municipality and Ballast Nedam created a common ground between actors. In the interviews, various actors mentioned having some kind of shared language, and, in some cases, having worked together before, making them aware of each other’s knowledge and capabilities. They indicated the importance of trust and a given scope to convey opinions. Hence, the geographic proximity of actors facilitated a certain atmosphere within the network that strengthened communication and cooperation (cf. Elfring, Klyver, and van Burg Citation2021).

Secondly, each actor was driven by intrinsic motivations. This is well known among actors working in cultural and creative industries, where strong intrinsic motivations often mean that actors prioritise aesthetics over costs or wages (Caves Citation2000; Throsby Citation2010). The interviews revealed that not only the architect advocated aesthetic ends, but also the contractor, municipality, manufacturer and consultants. They became, as it were, (temporary) members of, to use Howard Becker’s (Citation1982) term, the art world that enabled the creation of this wall. As was explained by Jan Boom of Aldowa: ‘With such a unique project it is not just about the costs. We were all willing to go the extra mile. Willing to work and to create something beautiful’. Expressing this shared dream resulted in a high degree of willingness to cooperate between actors.

It was not like the traditional construction world where everyone does their own trick and mainly focusses on costs. Everyone thought it was a unique project and wanted to contribute to make it a success. (…) And the great thing about it is that, when you agree in advance that you will work on a dream together, then you can address each other later on, motivate each other to do it differently and together. We could always talk to each other and hold each other accountable, that is why I think it worked out so well. We discussed choices and could always say: what about our dream. (Aldowa)

The emphasis on aesthetics partly depends on the type of project the actors are involved in, in this case the building of a theatre. As Arup’s employee explains: ‘with projects in performing arts we always have to deal with clients who want to prioritise aesthetics and acoustics, they want to pursue a certain sound’. Thus, their clients, the municipality and Ballast Nedam, envisaged the same dream to create something aesthetically pleasing, and had therefore largely similar priorities. The municipality and Ballast Nedam, being the actors on top of the hierarchy and the initiators of the project, recognised the importance of specific knowledge and input of actors with similar intrinsic motivations, such as acoustic and theatre consultants, and gave them plenty of room to enforce their expertise. Finally, due to a high degree of trust, the municipality and Ballast Nedam dared to take risks. Studio RAP was, at a late stage in production, given the opportunity to apply their innovative ‘digital workflow’ approach, despite the fact that this was unknown territory for many actors in the network.

Proximity and familiarity between actors as well as a shared dream (i.e. emphasising aesthetics) ensured effective communication, cooperation and trust. Although the project was generally characterised by top-down management – the municipality and Ballast Nedam having the final say in the making of decisions – simultaneously, most actors argued that there was a decentralised power environment. A lot of space was given to actors to voice and enforce their opinion and thereby wield a certain amount of power. In this way, collaboration could flourish for all actors involved. This becomes clear when considering Studio RAP’s influence in the process. The municipality and Ballast Nedam provided freedom throughout the process for Studio RAP to elaborate on their ideas. This paved the way for Studio RAP to, as we have seen, apply their own innovative approach, the digital workflow strategy, with which they earned even more tasks, responsibilities, and a greater say. As such, in collaboration with the clients and by means of their own expertise and innovation, architectural practice Studio RAP ensured a prominent role in the production process.

Conclusions

Above, we have sought to explore how a small and young architectural practice was able to claim much more control of the design and realisation process than one would expect given the long-term trend of marginalisation of architects. By providing detailed insights into a deviant case, we have aimed to reveal the conditions under which architects can reclaim lost territory. The relevance of this question is not just limited to the architectural profession, but may have significant consequences for wider society as architects often take into account various societal, environmental, and aesthetic concerns. In a sense, then, architects can be seen as (potential) guardians of a much broader set of societal values than just economic efficiency. To protect this role, certain conditions have to be fulfilled to keep the market imperative at bay (Brandellero and Kloosterman Citation2010). Analysing why and how Studio RAP succeeded in (re)capturing a more prominent and essential role in the design and subsequent production of the acoustic wall of Theater Zuidplein, accordingly, may convey more important general lessons.

We first investigated what caused the architects’ weakening position (e.g. the limiting of architects’ responsibilities, autonomy and space for creativity). We distinguished between four main intertwined developments that have fundamentally marginalised the role of architects: (1) stringent requirements leading to increased specialisation; (2) the dissemination of design software; (3) market structures prioritising risk and cost-reduction; and (4) a contestation of the architects’ image (Samuel Citation2018; Imrie and Street Citation2011; Jones Citation2006, RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) Citation2005). The lack of agreement on the profession’s expertise, resources, and skills, causes the architect to be perceived as dispensable, which reinforces the trend of marginalisation. Therefore, in order for architects to (re)capture lost responsibilities and revitalise their value, a central and pressing issue is to reframe architects’ image in a way that convinces others of their added value. Therefore, Samuel (Citation2018) stresses the need for additional research on architects’ role during the production process. This article responds to Samuel’s request by both demonstrating Studio RAP’s expertise and added value, as well as by showing the importance of a supporting and enabling context in which the architect can flourish.

The analytical building blocks of the GPN approach provided a useful tool to disentangle and open up the production process and network of Theater Zuidplein, in which Studio RAP took on a prominent role. First, their ability to do so is a result of their ‘digital workflow’ strategy, by which they were able to acquire tasks in both design and construction. Their knowledge on digital construction techniques allowed Studio RAP to counter the trend in which architects are increasingly reduced to ‘form-givers’ with limited responsibilities for the preliminary design. Since Studio RAP was able to control activities in creation, engineering and construction, they did not lose responsibility over the final design, were able to subcontract Arup, and made less concessions throughout the entire process. In addition, by strategically showing their 3D design with 3D glasses, Studio RAP convinced Ballast Nedam, the municipality and the direction of Theater Zuidplein of their added value. Hence, Studio RAP is an example of an architecture practice that uses the trend of digitalisation to its advantage.

Secondly, Studio RAP’s prominence can be attributed to the specific network structure and relations, which created favourable conditions for Studio RAP to demonstrate their abilities (cf. Elfring, Klyver, and van Burg Citation2021). Although the municipality and Ballast Nedam were responsible for the final decisions, they encouraged Studio RAP to voice and enforce their opinions and thereby wield a certain amount of power. In addition, the local embeddedness of the network, the high degree of trust, the willingness to take risks, and shared intrinsic motivations ensured effective and efficient collaboration between actors. These elements of the process seemed of higher significance than ends of cost-efficiency and risk-reduction (Imrie and Street Citation2011), and this environment paved the way for the architect to, as we have seen, pursue their own autonomy and take space for innovativeness and creativity. As such, architects’ actions are highly dependent on other specialists and inextricably connected and shaped by a project’s context. Our findings corroborate those of Imrie and Street (Citation2014, 735) who state that ‘[t]he autonomy of architects can be enhanced by recognising their dependence on the social conditions, and contexts, that frame their actions, and by developing a politics of practice that enables the relational resources necessary for autonomous actions to be secured’. Accordingly, creativity and innovation in design is ‘not the preserve of any one individual, or reducible to singular acts of genius, but is part of co-constituted relationships’ (Imrie and Street Citation2011, 101).

However, it is important to bear in mind that this project concerns a cultural amenity. The actors and the architect had similar intrinsic motivations and goals based mainly on aesthetics, which fosters innovation and creativity. When actors, on the other hand, have different priorities, notably cost-efficiency and risk-reduction, it remains to be seen whether Studio RAP’s innovative digital techniques would gain the same role for the architect. Therefore, further research should be conducted in different contexts (e.g. commercial real-estate) to analyse more broadly the specific interplay between the role of the architect, creativity, and the influence of digital techniques.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Wessel van Beerendonk, John Dols, Arie Verschoor, Fred den Hartog, Bareld Nicolai, Gerbrand Borgdorff, Jan Boom, Peter Bijvoet, and Paul Zwartjes for their time and their willingness to talk to us. We would also like thank Lía Barrese, Montserat Pareja-Eastaway, Jochem de Vries, and Joris de Vries for their comments and suggestions. We would especially express our thanks to Suzan van Kempen for her role in conducting the interviews and her helpful comments. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the interviewees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “… with certification, any person can perform the relevant tasks, but the government or generally another non-profit agency administers an examination and certifies those who have passed, as well as identifies the level of skill and knowledge for certification” (Kleiner Citation2006).

References

- ACE (Architects’ Council of Europe). 2019. “The Value of Design and the Role of Architects: A Study for ACE Architects’ Council of Europe.” EU. https://www.ace-cae.eu/uploads/tx_jidocumentsview/Value_of_Design.pdf.

- AIA (American Institute of Architects). 2007. “Emerging Risks in Practice.” Accessed 4 May 2021. www.aia.org/pm_a_20050722_risks

- Architectenweb. 2020, June 25. “Zaal Theater Zuidplein ontworpen door algoritmen. Accessed 8 June 2021. https://architectenweb.nl/projecten/project.aspx?ID=39883

- Architectuur Lokaal. 2020. “Competition Culture in Europe 2017 2020.” Final Report. Accessed 10 June 2021. https://arch-lokaal.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Competition_Culture_in_Europe_2017_2020.pdf.

- Becker, H. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Blau, J. R. 1984. Architects and Firms; a Sociological Perspective on Architectural Practice. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Bos-de Vos, M., B. Lieftink, J. Kraaijeveld, K. Lauche, A. Smits, L. Li Ling, L. Volker, and H. Wamelink. 2018. “Future Roles for Architects: An Academic Design Guide.” FuturA research. TU Delft. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325683178_Future_roles_for_architects_an_academic_design_guide

- Brandellero, A. M. C., and R. C. Kloosterman. 2010. “Keeping the Market at Bay: Exploring the Loci of Innovation in the Cultural Industries.” Creative Industries Journal 3 (1 + 2): 61–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/cij.3.1-2.61_1.

- Caves, R. E. 2000. Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce. London: Harvard University Press.

- Coe, N. M. 2015. Global Production Networks in the Creative Industries. The Oxford Handbook of Creative Industries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coe, N. M., and H. W. Yeung. 2015. Global Production Networks: Theorizing Economic Development in an Interconnected World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coe, N. M., P. Dicken, and M. Hess. 2008. “Global Production Networks: Realizing the Potential.” Journal of Economic Geography 8 (3): 271–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn002.

- Dainty, A., D. Moore, and M. Murray. 2006. Communication in Construction: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203358641.

- Davis, H. 2008. “Form and Process in the Transformation of the Architect’s Role in Society.” In Philosophy and Design: From Engineering to Architecture, edited by P. E. Vermaas, P. Kroes, A. Light, and S. A. Moore, 273–286. Berlin: Springer.

- De Architect. 2020, May 19. “Theater Zuidplein in Rotterdam door de Zwarte Hond, Studio RAP en BURO M2R.” Accessed 8 June 2021. https://www.dearchitect.nl/projecten/theater-zuidplein-in-rotterdam-door-de-zwarte-hond-studio-rap-en-buro-m2r

- De Volkskrant. 2020, June 25. “Het nieuwe Theater Zuidplein is een voorlopig hoogtepunt.” Accessed 8 June 2021. https://www.volkskrant.nl/cultuur-media/het-nieuwe-theater-zuidplein-is-een-voorlopig-hoogtepunt∼b44fc113/?utm_campaign=shared_earned&utm_medium=social&utm_source=copylink

- Dent, M., and S. Whitehead, eds. 2002. Managing Professional Identities. London: Routledge.

- Elfring, T., K. Klyver, and E. van Burg. 2021. Entrepreneurship as Networking: Mechanisms, Dynamics, Practices, and Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- European Commission. 2015. “Mutual evaluation of regulated professions. Overview of the regulatory framework in the business services sector by using the example of architects.” GROW/E-5 – 27 October 2015. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/13382/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

- European Commission. 2017. “Public Procurement.” Accessed 21 September 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/public-procurement_en

- Franck, O. A. 2017. “The changing roles of the architect.” Accessed 3 December 2020. http://www.eaae.be/eaae-academies/education-academy/themes/changing-roles-architect/

- Geertse, M. 2014. “Towards a Professional Commissioning Practice. An Assessment of Recent Public Design Competition Culture in The Netherlands.” Research Gate.

- Hiley, A., and K. Khadzir. 1999. The Future Role of Architects, COBRA. London: RICS.

- Imrie, R., and E. Street. 2011. Architectural Design and Regulation. 1st ed. Oxford: Wiley. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444393156.ch6.

- Imrie, R., and E. Street. 2014. “Autonomy and the Socialisation of Architects.” The Journal of Architecture 19 (5): 723–739. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2014.967271.

- Jones, C. B. 2006. “The Role of the Architect: Changes of the Past, Practices of the Present, and Indications of the Future.” https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1394&context=etd

- Junte, J. 2020, September 22. “Studio RAP ontwerpt theaterzaal Zuidplein Rotterdam.” Accessed 8 June 2021. https://www.architectuur.nl/inspiratie/studio-rap-ontwerpt-theaterzaal-zuidplein-rotterdam/

- Kelly, J., and S. Male. 1993. Value Management in Design and Construction: The Economic Management of Projects. London: E & FN Spon.

- Kleiner, M. M. 2006. Licensing Occupations; Ensuring Quality or Restricting Competition. Kalamazoo: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

- Kloosterman, R. C. 2007. “Walls and Bridges: Knowledge Spillover between ‘Superdutch’ Architectural Firms.” Journal of Economic Geography 8 (4): 545–563. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn010.

- Kloosterman, R. C. 2017. “The Urban Commons and Cultural Industries; an Exploration of the Institutional Embeddedness of Architectural Design in The Netherlands.” In The Routledge Handbook of Planning and Institutions in Action, edited by W. Salet. New York: Routledge:

- Kloosterman, R. C., and E. S. Stegmeijer. 2004. “Cultural Industries in The Netherlands-Path-Dependent Patterns and Institutional Contexts: The Case of Architecture in Rotterdam.” Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen 148 (4): 66–73.

- Koetsenruijter, R., and R. Kloosterman. 2018. “Ruimte voor de architect Een onderzoek naar de veranderingen in positie van architecten in Nederland, 2008–2018.” University of Amterdam: Centre for Urban studies/GPIO.

- Loe, E. 2000. Context and Current Thinking (the Value of Architecture). 1st ed. London: RIBA.

- Meijer, F., and H. Visscher. 2014. The legal position of architects in the European Union. OTB Research Institute for Housing. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27349809_The_legal_position_of_architects_in_the_European_Union

- Miller, P., L. Kurunmaki, and T. O’Leary. 2008. “Accounting, Hybrids and the Management of Risk, Accounting.” Organisations and Society 33 (7–8): 942–967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.02.005.

- NRC. 2021, January 12. “Kunstenpand in Rotterdam herbergt spectaculaire theatergrot.” Accessed 8 June 2021. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2021/01/12/kunstenpand-in-rotterdam-herbergt-spectaculaire-theatergrot-a4027175

- Power, M. 2004. The Risk Management of Everything. London: Demos.

- RIBA & Microsoft. 2018. “Digital transformation in architecture. Report by Royal Institute for British Architects (RIBA) and Microsoft.” https://www.architecture.com/-/media/gathercontent/digital-transformation-in-architecture/additionaldocuments/microsoftribadigitaltransformationreportfinal180629pdf.pdf

- RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects). 2000. Architects and the Changing Construction Industry. London: RIBA Journal, RIBA.

- RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects). 2005. RIBA Constructive Change: A Strategic Industry Study into the Future of the Architects’ Profession: Full Report. London: RIBA.

- Samuel, F. 2018. Why Architects Matter: Evidencing and Communicating the Value of Architects. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Studio RAP. (n.d.). Studio RAP. Accessed 9 June 2021. https://studiorap.nl/#/about

- Throsby, C. 2010. The Economics of Cultural Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Kempen, S., R. Mathôt, and R. C. Kloosterman. 2021. “De Ruimtelijke Ontwerpsector Ontleed. Trends en profielen van (bouwkundig) architecten, interieurarchitecten, tuin- en landschapsarchitecten en stedenbouwkundigen en andere ruimtelijk ontwerpers.” Centre for Urban Studies/GPIO, Universiteit van Amsterdam.